Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

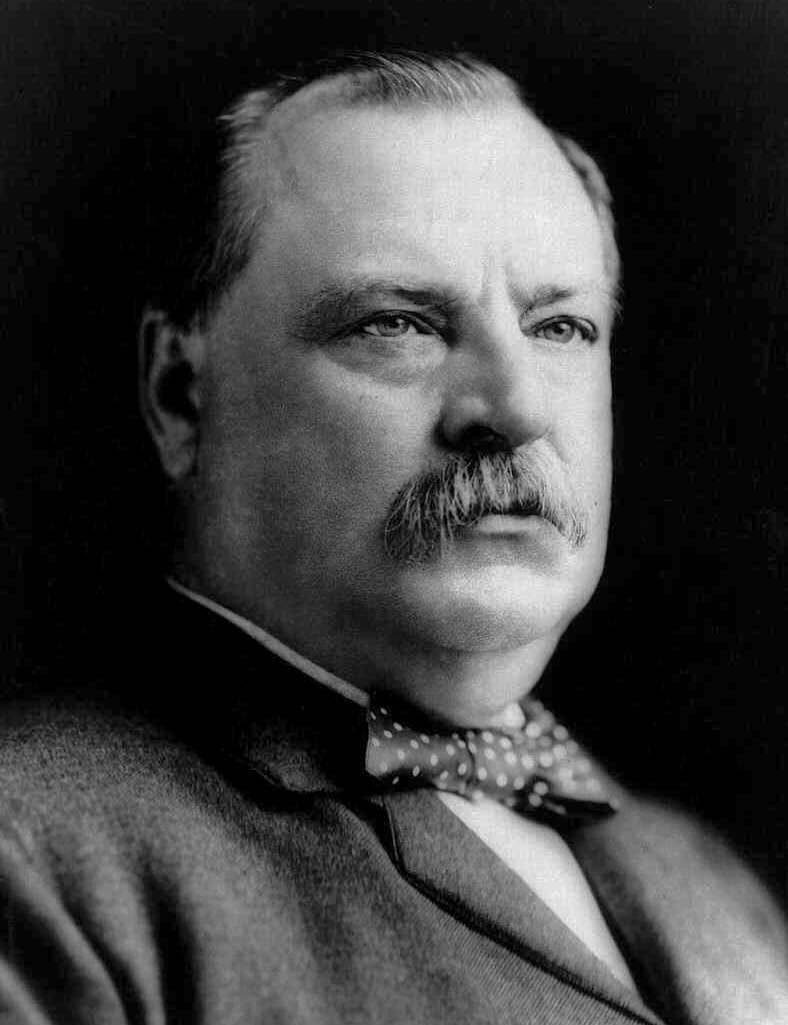

Grover Cleveland

View on Wikipedia

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837 – June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Democrat elected president after the American Civil War.

Key Information

Born in Caldwell, New Jersey, Cleveland was elected mayor of Buffalo in 1881 and governor of New York in 1882. While governor, he closely cooperated with state assembly minority leader Theodore Roosevelt to pass reform measures, winning national attention.[1] He led the Bourbon Democrats, a pro-business movement opposed to high tariffs, free silver, inflation, imperialism, and subsidies to businesses, farmers, or veterans. His crusade for political reform and fiscal conservatism made him an icon for American conservatives of the time.[2] Cleveland also won praise for honesty, self-reliance, integrity, and commitment to classical liberalism.[3] His fight against political corruption, patronage, and bossism convinced many like-minded Republicans, called "Mugwumps", to cross party lines and support him in the 1884 presidential election, which he narrowly won against Republican James G. Blaine.

During his first presidency, Cleveland signed the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, which made the railroad industry the first industry subject to federal regulation by a regulatory body,[4] and the Dawes Act, which subdivided Native American tribal communal landholdings into individual allotments. This policy led to Native Americans ceding control of about two-thirds of their land between 1887 and 1934.[5][6] In the 1888 election, Cleveland won the popular vote but lost the electoral college and therefore the election to Benjamin Harrison. He returned to New York City and joined a law firm.

In a rematch against Harrison for the 1892 election, Cleveland won both the popular vote and electoral college, returning him to the White House. One month before his second presidency began, the Panic of 1893 sparked a severe national depression. An anti-imperialist, Cleveland opposed the push to annex Hawaii, launched an investigation into the 1893 coup against Queen Liliʻuokalani, and called for her restoration.[7][8] Cleveland intervened in the 1894 Pullman Strike to keep the railroads moving, angering Illinois Democrats and labor unions nationwide; his support of the gold standard and opposition to free silver alienated the agrarian wing of the Democrats.[9] Critics complained that Cleveland had little imagination and seemed overwhelmed by the nation's economic disasters—depressions and strikes—in his second term.[9] Many voters blamed the Democrats, opening the way for a Republican landslide in 1894 and for the agrarian and free silver (silverite) seizure of the Democratic Party at the 1896 Democratic convention. By the end of his second term, he was highly unpopular, even among Democrats.[10]

After leaving the White House, Cleveland served as a trustee of Princeton University. He joined the American Anti-Imperialist League in protest of the 1898 Spanish-American War.[11] He died in 1908.

Early life

[edit]Childhood and family history

[edit]

Stephen Grover Cleveland was born on March 18, 1837, in Caldwell, New Jersey, to Ann (née Neal) and Richard Falley Cleveland.[12] Cleveland's father was a Congregational and Presbyterian minister who was originally from Connecticut.[13] His mother was from Baltimore and was the daughter of a bookseller.[14] On his father's side, Cleveland was descended from English ancestors, the first of the family having emigrated to Massachusetts from Ipswich, England, in 1635.[15] On his mother's side, Cleveland was descended from Anglo-Irish Protestants and German Quakers from Philadelphia.[16] Cleveland was distantly related to General Moses Cleaveland, after whom the city of Cleveland, Ohio, was named.[17]

Cleveland, the fifth of nine children, was named Stephen Grover in honor of the first pastor of the First Presbyterian Church of Caldwell, where his father was pastor at the time. He became known as Grover in his adult life.[18] In 1841, the Cleveland family moved to Fayetteville, New York, where Grover spent much of his childhood.[19] Neighbors later described him as "full of fun and inclined to play pranks",[20] and fond of outdoor sports.[21]

In 1850, Cleveland's father Richard moved his family to Clinton, New York, accepting a job there as district secretary for the American Home Missionary Society.[22] Despite his father's dedication to his missionary work, his income was insufficient for the large family. Financial conditions forced him to remove Grover from school and place him in a two-year mercantile apprenticeship in Fayetteville. The experience was valuable, though brief. Grover returned to Clinton and his schooling at the completion of the apprentice contract.[23] In 1853, missionary work began to take a toll on Richard's health. He took a new work assignment in Holland Patent, New York, and moved his family once again.[24] Shortly after, Richard Cleveland died from a gastric ulcer. Grover was said to have learned about his father's death from a boy selling newspapers.[24]

Education and moving west

[edit]

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal 28th Governor of New York 22nd & 24th President of the United States

Tenure Presidential campaigns Legacy

|

||

Cleveland received his elementary education at the Fayetteville Academy and the Clinton Grammar School (not to be confused with the Clinton Liberal Institute).[25] After his father died in 1853, he again left school to help support his family. Later that year, Cleveland's brother William was hired as a teacher at the New York Institute for the Blind in New York City, and William obtained a place for Cleveland as an assistant teacher. Cleveland returned home to Holland Patent at the end of 1854, where an elder in his church offered to pay for his college education if he promised to become a minister. Cleveland declined, and in 1855 he decided to move west.[26]

He stopped first in Buffalo, New York, where his cousin Lewis F. Allen, gave him a clerical job.[27] Allen was an important man in Buffalo, and he introduced Cleveland to influential men there, including the partners in the law firm of Rogers, Bowen, and Rogers.[28] Millard Fillmore, the 13th president of the United States, had previously worked for the partnership.[29] Cleveland later took a clerkship with the firm, began to read the law with them, and was admitted to the New York bar in 1859.[30]

Early career and the American Civil War

[edit]Cleveland worked for the Rogers firm for three years before leaving in 1862 to start his own practice.[31] In January 1863, he was appointed assistant district attorney of Erie County, New York.[32] With the American Civil War raging, Congress passed the Conscription Act of 1863, requiring able-bodied men to serve in the army if called upon, or else to hire a substitute.[30] Cleveland chose the latter course, paying $150, equivalent to $3,831 in 2024, to George Benninsky, a thirty-two-year-old Polish immigrant, to serve in his place.[33] Benninsky survived the war.[30]

As a lawyer, Cleveland became known for his single-minded concentration and dedication to hard work.[34] In 1866, he successfully defended some participants in the Fenian raid, working on a pro bono basis (free of charge).[35] In 1868, Cleveland attracted professional attention for his winning defense of a libel suit against the editor of Buffalo's Commercial Advertiser.[36] During this time, Cleveland assumed a lifestyle of simplicity, taking residence in a plain boarding house. He devoted his growing income to the support of his mother and younger sisters.[37] While his personal quarters were austere, Cleveland enjoyed an active social life and "the easy-going sociability of hotel-lobbies and saloons".[38] He shunned the circles of higher society of Buffalo in which his uncle-in-law's family traveled.[39]

Political career in New York

[edit]Sheriff of Erie County

[edit]

From his earliest involvement in politics, Cleveland aligned with the Democratic Party.[40] He had a decided aversion to Republicans John C. Frémont and Abraham Lincoln, and the heads of the Rogers law firm were solid Democrats.[41] In 1865, he ran for District Attorney, losing narrowly to his friend and roommate, Lyman K. Bass, the Republican nominee.[34]

In 1870, with the help of friend Oscar Folsom, Cleveland secured the Democratic nomination for sheriff of Erie County, New York.[42] He won the election by a 303-vote margin and took office on January 1, 1871, at age 33.[43][44] While this new career took him away from the practice of law, it was rewarding in other ways: the fees were said to yield up to $40,000, equivalent to $1,049,889 in 2024, over the two-year term.[42]

Cleveland's service as sheriff was unremarkable. Biographer Rexford Tugwell described the time in office as a waste for Cleveland politically. Cleveland was aware of graft in the sheriff's office during his tenure and chose not to confront it.[45] A notable incident of his term took place on September 6, 1872, when Patrick Morrissey was executed. He had been convicted of murdering his mother.[46] As sheriff, Cleveland was responsible for either personally carrying out the execution or paying a deputy $10 to perform the task.[46] In spite of reservations about the hanging, Cleveland executed Morrissey himself.[46] He hanged another murderer, John Gaffney, on February 14, 1873.[47]

After his term as sheriff ended, Cleveland returned to his law practice, opening a firm with his friends Lyman K. Bass and Wilson S. Bissell.[48] Bass was later replaced by George J. Sicard.[49] Elected to Congress in 1872, Bass did not spend much time at the firm, but Cleveland and Bissell soon rose to the top of Buffalo's legal community.[50] Up to that point, Cleveland's political career had been honorable and unexceptional. As biographer Allan Nevins wrote, "Probably no man in the country, on March 4, 1881, had less thought than this limited, simple, sturdy attorney of Buffalo that four years later he would be standing in Washington and taking the oath as President of the United States."[51]

It was during this period that Cleveland began courting a widow, Maria Halpin. She later accused him of raping her.[52][53][54] It is unclear if Halpin was actually raped by Cleveland as some early reports stated or if their relationship was consensual.[55] In March 1876, Cleveland accused Halpin of being an alcoholic and had her child removed from her custody. The child was taken to the Protestant Orphan Asylum, and Cleveland paid for his stay there.[55] Cleveland had Halpin admitted to the Providence Asylum. Halpin was only kept at the asylum for five days because she was deemed not to be insane.[55][56] Cleveland later provided financial support for her to begin her own business outside of Buffalo.[55] Although lacking irrefutable evidence that Cleveland was the father,[57] the child became a campaign issue for the Republican Party in Cleveland's first presidential campaign, where they smeared him by claiming that he was "immoral" and for allegedly acting cruelly by not raising the child himself.[57][58]

Mayor of Buffalo

[edit]In the 1870s, the municipal government in Buffalo had grown increasingly corrupt, with Democratic and Republican political machines cooperating to share the spoils of political office.[59] When the Republicans nominated a slate of particularly disreputable machine politicians for the 1881 election, Democrats saw an opportunity to gain the votes of disaffected Republicans by nominating a more honest candidate.[60] Party leaders approached Cleveland, who agreed to run for Mayor of Buffalo provided the party's slate of candidates for other offices was to his liking.[61] More notorious politicians were left off the Democratic ticket and he accepted the nomination.[61] Cleveland was elected mayor that November with 15,120 votes, while his Republican opponent Milton Earl Beebe received 11,528 votes.[62] He took office on January 2, 1882.[63]

Cleveland's term as mayor was spent fighting the entrenched interests of the party machines.[64] Among the acts that established his reputation was a veto of the street-cleaning bill passed by the Buffalo Common Council.[65] The street-cleaning contract had been the subject of competitive bidding, and the Council selected the highest bidder at $422,000, rather than the lowest at $100,000 less, because of the political connections of the bidder.[65] Previous mayors had allowed similar bills in the past, but Cleveland's veto message said, "I regard it as the culmination of a most bare-faced, impudent, and shameless scheme to betray the interests of the people, and to worse than squander the public money."[66] The Council reversed itself and awarded the contract to the lowest bidder.[67] Cleveland also asked the state legislature to form a Commission to develop a plan to improve the sewer system in Buffalo at a much lower cost than previously proposed locally; this plan was successfully adopted.[68] For this, and other actions safeguarding public funds, Cleveland began to gain a reputation beyond Erie County as a leader willing to purge government corruption.[69]

Governor of New York

[edit]

Democratic party officials started to consider Cleveland a possible nominee for Governor of New York.[70] Daniel Manning, a party insider who admired Cleveland's record, was instrumental in his candidacy.[71] With a split in the state Republican Party in 1882, the Democratic party was considered to be at an advantage; several men contended for that party's nomination.[70] The two leading Democratic candidates were Roswell P. Flower and Henry Warner Slocum. Their factions deadlocked and the convention could not agree on a nominee.[72] Cleveland, who came in third place on the first ballot, picked up support in subsequent votes and emerged as the compromise choice.[73] With Republicans still divided heading into the general election, Cleveland emerged the victor, receiving 535,318 votes to Republican nominee Charles J. Folger's 342,464.[74] Cleveland's margin of victory was, at the time, the largest in a contested New York election. The Democrats also picked up seats in both houses of the New York State Legislature.[75]

Cleveland brought his opposition to needless spending to the governor's office. He promptly sent the legislature eight vetoes in his first two months in office.[76] The first to attract attention was his veto of a bill to reduce the fares on New York City elevated trains to five cents.[77] The bill had broad support because the trains' owner, Jay Gould, was unpopular, and his fare increases were widely denounced.[78] Cleveland saw the bill as unjust—Gould had taken over the railroads when they were failing and had made the system solvent again.[79] Cleveland believed that altering Gould's franchise would violate the Contract Clause of the federal Constitution.[79] Despite the initial popularity of the fare-reduction bill, the newspapers praised Cleveland's veto.[79] Theodore Roosevelt, then a member of the Assembly, had reluctantly voted for the bill with the intention of holding railroad barons accountable.[80] After the veto, Roosevelt and other legislators reversed their position, and Cleveland's veto was sustained.[80]

Cleveland's defiance of political corruption won him popular acclaim; it also brought the enmity of New York City's influential Tammany Hall organization and its boss, John Kelly.[81] Tammany Hall and Kelly had disapproved of Cleveland's nomination for governor, and their resistance intensified after Cleveland openly opposed and prevented the reelection of Thomas F. Grady, their point man in the State Senate.[82] Cleveland also steadfastly opposed other Tammany nominees, as well as bills passed as a result of their deal-making.[83] The loss of Tammany's support was offset by the support of Theodore Roosevelt and other reform-minded Republicans, who helped Cleveland pass several laws to reform municipal governments.[84] Cleveland closely worked with Roosevelt, who served as assembly minority leader in 1883; the municipal legislation they cooperated on gained Cleveland national recognition.[1]

Election of 1884

[edit]Nomination for president

[edit]

In June 1884, the Republican Party convened their national convention in Chicago, selecting former U.S. House Speaker James G. Blaine of Maine as their nominee for president. Blaine's nomination alienated many Republicans, including the Mugwumps, who viewed Blaine as ambitious and immoral.[85] The Republican standard-bearer was further weakened when the Conkling faction and President Chester Arthur refused to give Blaine their strong support.[86] Democratic party leaders believed the Republicans' choice gave them an opportunity to win the White House for the first time since 1856 if the right candidate could be found.[85]

Among the Democrats, Samuel J. Tilden was the initial front-runner, having been the party's nominee in the contested election of 1876.[87] After Tilden declined a nomination due to his poor health, his supporters shifted to several other contenders.[87] Cleveland was among the leaders in early support, and Thomas F. Bayard of Delaware, Allen G. Thurman of Ohio, Samuel Freeman Miller of Iowa, and Benjamin Butler of Massachusetts also had considerable followings, along with various favorite sons.[87] Each of the other candidates had hindrances to his nomination: Bayard had spoken in favor of secession in 1861, making him unacceptable to Northerners; Butler, conversely, was reviled throughout the Southern United States for his actions during the American Civil War; Thurman was generally well-liked, but was growing old and infirm, and his views on the silver question were uncertain.[88]

Cleveland, too, had detractors—Tammany remained opposed to him—but the nature of his enemies made him still more friends.[89] Cleveland led on the first ballot, with 392 votes out of 820.[90] On the second ballot, Tammany threw its support behind Butler, but the rest of the delegates shifted to Cleveland, who won. Thomas A. Hendricks of Indiana was selected as his running mate.[91]

Campaign against Blaine

[edit]Corruption in politics was the central issue in 1884; Blaine had over the span of his career been involved in several questionable deals.[92] Cleveland's reputation as an opponent of corruption proved the Democrats' strongest asset.[93] William C. Hudson created Cleveland's contextual campaign slogan "A public office is a public trust."[94] Reform-minded Republicans called "Mugwumps" denounced Blaine as corrupt and flocked to Cleveland.[95] The Mugwumps, including such men as Carl Schurz and Henry Ward Beecher, were more concerned with morality than with party, and felt Cleveland was a kindred soul who would promote civil service reform and fight for efficiency in government.[95] At the same time that the Democrats gained support from the Mugwumps, they lost some blue-collar workers to the Greenback-Labor party, led by ex-Democrat Benjamin Butler.[96] In general, Cleveland abided by the precedent of minimizing presidential campaign travel and speechmaking; Blaine became one of the first to break with that tradition.[97]

The campaign focused on the candidates' moral standards, as each side cast aspersions on their opponents. Cleveland's supporters rehashed the old allegations that Blaine had corruptly influenced legislation in favor of the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad and the Union Pacific Railway, later profiting on the sale of bonds he owned in both companies.[98] Although the stories of Blaine's favors to the railroads had made the rounds eight years earlier, this time Blaine's correspondence was discovered, making his earlier denials less plausible.[98] On some of the most damaging correspondence, Blaine had written "Burn this letter", giving Democrats the last line to their rallying cry: "Blaine, Blaine, James G. Blaine, the continental liar from the state of Maine, 'Burn this letter!'"[99]

Regarding Cleveland, commentator Jeff Jacoby notes that, "Not since George Washington had a candidate for President been so renowned for his rectitude."[100] But the Republicans found a refutation buried in Cleveland's past. Aided by the sermons of Reverend George H. Ball, a minister from Buffalo, they made public the allegation that Cleveland had fathered a child while he was a lawyer there,[101] and their rallies soon included the chant "Ma, Ma, where's my Pa?".[102] When confronted with the scandal, Cleveland immediately instructed his supporters to "Above all, tell the truth."[58] He admitted to paying child support in 1874 to Maria Crofts Halpin, the woman who asserted he had fathered her son Oscar Folsom Cleveland and he assumed responsibility.[58] Shortly before the 1884 election, the Republican media published an affidavit from Halpin in which she stated that until she met Cleveland, her "life was pure and spotless", and "there is not, and never was, a doubt as to the paternity of our child, and the attempt of Grover Cleveland, or his friends, to couple the name of Oscar Folsom, or any one else, with that boy, for that purpose is simply infamous and false."[103]

The electoral votes of closely contested New York, New Jersey, Indiana, and Connecticut would determine the election.[104] In New York, the Tammany Democrats decided that they would gain more from supporting a Democrat they disliked than a Republican who would do nothing for them.[105] Blaine hoped that he would have more support from Irish Americans than Republicans typically did; while the Irish were mainly a Democratic constituency in the 19th century, Blaine's mother was Irish Catholic, and he had been supportive of the Irish National Land League while he was Secretary of State.[106] The Irish, a significant group in three of the swing states, did appear inclined to support Blaine until a Republican, Samuel D. Burchard, gave a speech pivotal for the Democrats, denouncing them as the party of "Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion".[107] The Democrats spread the word of this implied anti-Catholic insult on the eve of the election. They also blistered Blaine for attending a banquet with some of New York City's wealthiest men.[108]

After the votes were counted, Cleveland narrowly won all four of the swing states, including New York by 1,200 votes.[109] While the popular vote total was close, with Cleveland winning by just one-quarter of a percent, the electoral votes gave Cleveland a majority of 219–182.[109] Following the electoral victory, the "Ma, Ma ..." attack phrase gained a classic riposte: "Gone to the White House. Ha! Ha! Ha!"[110]

First presidency (1885–1889)

[edit]Reform

[edit]

Soon after taking office, Cleveland was faced with the task of filling all the government jobs for which the president had the power of appointment. These jobs were typically filled under the spoils system, but Cleveland announced that he would not fire any Republican who was doing his job well, and would not appoint anyone solely on the basis of party service.[111] He also used his appointment powers to reduce the number of federal employees, as many departments had become bloated with political time-servers.[112] Later in his term, as his fellow Democrats chafed at being excluded from the spoils, Cleveland began to replace more of the partisan Republican officeholders with Democrats;[113] this was especially the case with policymaking positions.[114] While some of his decisions were influenced by party concerns, more of Cleveland's appointments were decided by merit alone than was the case in his predecessors' administrations.[115]

Cleveland also reformed other parts of the government. In 1887, he signed an act creating the Interstate Commerce Commission.[116] He and Secretary of the Navy William C. Whitney undertook to modernize the Navy and canceled construction contracts that had resulted in inferior ships.[117] Cleveland angered railroad investors by ordering an investigation of Western lands they held by government grant. Secretary of the Interior Lucius Q. C. Lamar charged that the rights of way for this land must be returned to the public because the railroads failed to extend their lines according to agreements. The lands were forfeited, resulting in the return of approximately 81,000,000 acres (330,000 km2).[118]

Cleveland was the first Democratic president subject to the Tenure of Office Act which originated in 1867; the act purported to require the Senate to approve the dismissal of any presidential appointee who was originally subject to its advice and consent. Cleveland objected to the act in principle and his steadfast refusal to abide by it prompted its fall into disfavor and led to its ultimate repeal in 1887.[119]

Vetoes

[edit]As Congress and its Republican-led Senate sent Cleveland legislation he opposed, he often resorted to using his veto power.[120] He vetoed hundreds of private pension bills for American Civil War veterans, believing that if their pensions requests had already been rejected by the Pension Bureau, Congress should not attempt to override that decision.[121] When Congress, pressured by the Grand Army of the Republic, passed a bill granting pensions for disabilities not caused by military service, Cleveland also vetoed that.[122] In his first term alone, Cleveland used the veto 414 times, which was more than four times more often than any previous president had used it.[123] In 1887, Cleveland issued his most well-known veto, that of the Texas Seed Bill.[124] After a drought had ruined crops in several Texas counties, Congress appropriated $100,000 (equivalent to $3,499,630 in 2024) to purchase seed grain for farmers there.[124] Cleveland vetoed the expenditure. In his veto message, he espoused a theory of limited government:

I can find no warrant for such an appropriation in the Constitution, and I do not believe that the power and duty of the general government ought to be extended to the relief of individual suffering which is in no manner properly related to the public service or benefit. A prevalent tendency to disregard the limited mission of this power and duty should, I think, be steadfastly resisted, to the end that the lesson should be constantly enforced that, though the people support the government, the government should not support the people. The friendliness and charity of our countrymen can always be relied upon to relieve their fellow-citizens in misfortune. This has been repeatedly and quite lately demonstrated. Federal aid in such cases encourages the expectation of paternal care on the part of the government and weakens the sturdiness of our national character, while it prevents the indulgence among our people of that kindly sentiment and conduct which strengthens the bonds of a common brotherhood.[125]

Silver

[edit]One of the most volatile issues of the 1880s was whether the currency should be backed by gold and silver, or by gold alone.[126] The issue cut across party lines, with Western Republicans and Southern Democrats joining in the call for the free coinage of silver, and both parties' representatives in the northeast holding firm for the gold standard.[127] Because silver was worth less than its legal equivalent in gold, taxpayers paid their government bills in silver, while international creditors demanded payment in gold, resulting in a depletion of the nation's gold supply.[127]

Cleveland and Treasury Secretary Daniel Manning stood firmly on the side of the gold standard, and tried to reduce the amount of silver that the government was required to coin under the Bland–Allison Act of 1878.[128] Cleveland unsuccessfully appealed to Congress to repeal this law before he was inaugurated.[129] Angered Westerners and Southerners advocated for cheap money to help their poorer constituents.[130] In reply, one of the foremost silverites, Richard P. Bland, introduced a bill in 1886 that would require the government to coin unlimited amounts of silver, inflating the then-deflating currency.[131] While Bland's bill was defeated, so was a bill the administration favored that would repeal any silver coinage requirement.[131] The result was a retention of the status quo, and a postponement of the resolution of the free-silver issue.[132]

Tariffs

[edit]| "When we consider that the theory of our institutions guarantees to every citizen the full enjoyment of all the fruits of his industry and enterprise, with only such deduction as may be his share toward the careful and economical maintenance of the Government which protects him, it is plain that the exaction of more than this is indefensible extortion and a culpable betrayal of American fairness and justice ... The public Treasury, which should only exist as a conduit conveying the people's tribute to its legitimate objects of expenditure, becomes a hoarding place for money needlessly withdrawn from trade and the people's use, thus crippling our national energies, suspending our country's development, preventing investment in productive enterprise, threatening financial disturbance, and inviting schemes of public plunder." |

| Cleveland's third annual message to Congress, December 6, 1887.[133] |

Another contentious financial issue at the time was the protective tariff. These tariffs had been implemented as a temporary measure during the civil war to protect American industrial interests but remained in place after the war.[134] While it had not been a central point in his campaign, Cleveland's opinion on the tariff was that of most Democrats: that the tariff ought to be reduced.[135] Republicans generally favored a high tariff to protect American industries.[135] American tariffs had been high since the Civil War, and by the 1880s the tariff brought in so much revenue that the government was running a surplus.[136]

In 1886, a bill to reduce the tariff was narrowly defeated in the House.[137][138] The tariff issue was emphasized in the Congressional elections that year, and the forces of protectionism increased their numbers in the Congress, but Cleveland continued to advocate tariff reform.[139] As the surplus grew, Cleveland and the reformers called for a tariff for revenue only.[140] His message to Congress in 1887 (quoted at right) highlighted the injustice of taking more money from the people than the government needed to pay its operating expenses.[141] Republicans, as well as protectionist northern Democrats like Samuel J. Randall, believed that American industries would fail without high tariffs, and they continued to fight reform efforts.[142] Roger Q. Mills, chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, proposed a bill to reduce the tariff from about 47% to about 40%.[143] After significant exertions by Cleveland and his allies, the bill passed the House.[143] The Republican Senate failed to come to an agreement with the Democratic House, and the bill died in the conference committee. Dispute over the tariff persisted into the 1888 presidential election.[citation needed]

Foreign policy, 1885–1889

[edit]Cleveland was a committed noninterventionist who had campaigned in opposition to expansion and imperialism. He refused to promote the previous administration's Nicaragua canal treaty, and generally was less of an expansionist in foreign relations.[144] Cleveland's Secretary of State, Thomas F. Bayard, negotiated with Joseph Chamberlain of the United Kingdom over fishing rights in the waters off Canada, and struck a conciliatory note, despite the opposition of New England's Republican Senators.[145] Cleveland also withdrew from Senate consideration of the Berlin Conference treaty which guaranteed an open door for U.S. interests in the Congo.[146]

Military policy, 1885–1889

[edit]

Cleveland's military policy emphasized self-defense and modernization. In 1885 Cleveland appointed the Board of Fortifications under Secretary of War William C. Endicott to recommend a new coastal fortification system for the United States.[147][148] No improvements to U.S. coastal defenses had been made since the late 1870s.[149][150] The Board's 1886 report recommended a massive $127 million construction program (equivalent to $4.4 billion in 2024) at 29 harbors and river estuaries, to include new breech-loading rifled guns, mortars, and naval minefields. The Board and the program are usually called the Endicott Board and the Endicott Program. Most of the Board's recommendations were implemented, and by 1910, 27 locations were defended by over 70 forts.[151][152] Many of the weapons remained in place until scrapped in World War II as they were replaced with new defenses. Endicott also proposed to Congress a system of examinations for Army officer promotions.[153] For the Navy, the Cleveland administration, spearheaded by Secretary of the Navy William Collins Whitney, moved towards modernization, although no ships were constructed that could match the best European warships. Although completion of the four steel-hulled warships begun under the previous administration was delayed due to a corruption investigation and subsequent bankruptcy of their building yard, these ships were completed in a timely manner in naval shipyards once the investigation was over.[154] Sixteen additional steel-hulled warships were ordered by the end of 1888. These ships played a vital role during the Spanish–American War of 1898, and many later served in World War I. Among them were the "second-class battleships" Maine and Texas, designed to match modern armored ships recently acquired by South American countries from Europe, such as the Brazilian battleship Riachuelo.[155] Eleven protected cruisers (including the famous Olympia), one armored cruiser, and one monitor were also ordered, along with the experimental cruiser Vesuvius.[156]

Civil rights and immigration

[edit]Under Cleveland, gains in civil rights for African Americans were limited.[157] Cleveland, like a growing number of Northerners and nearly all white Southerners, saw Reconstruction as a failed experiment,[158] and was reluctant to use federal power to enforce the 15th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which guaranteed voting rights to African Americans.[159] Though Cleveland appointed no black Americans to patronage jobs, he allowed Frederick Douglass to continue in his post as recorder of deeds in Washington, D.C., and appointed another black man (James Campbell Matthews, a former New York judge) to replace Douglass upon his resignation.[159] His decision to replace Douglass with a black man was met with outrage, but Cleveland claimed to have known Matthews personally.[160]

Although Cleveland had condemned the "outrages" against Chinese immigrants, he believed that Chinese immigrants were unwilling to assimilate into white society.[161] Secretary of State Thomas F. Bayard negotiated an extension to the Chinese Exclusion Act, and Cleveland lobbied the Congress to pass the Scott Act, written by Congressman William Lawrence Scott, which prevented the return of Chinese immigrants who left the United States.[162] The Scott Act easily passed both houses of Congress, and Cleveland signed it into law on October 1, 1888.[162]

Native American policy

[edit]

Cleveland viewed Native Americans as wards of the state, saying in his first inaugural address that "[t]his guardianship involves, on our part, efforts for the improvement of their condition and enforcement of their rights."[163] He encouraged the idea of cultural assimilation, pushing for the passage of the Dawes Act, which would allow lands held in trust by the federal government for the tribes to instead be distributed to individual tribe members.[163] While a conference of Native leaders endorsed the act, in practice the majority of Native Americans disapproved of it.[164] Cleveland believed the Dawes Act would lift Native Americans out of poverty and encourage their assimilation into white society. It ultimately weakened the tribal governments and allowed individual Indians to sell land and keep the money.[163] The act led to Native Americans ceding control of about 100 million acres of land between 1887 and 1934, which was around "two-thirds of the land base they held in 1887."[5][6]

In the month before Cleveland's 1885 inauguration, President Arthur opened four million acres of Winnebago and Crow Creek Indian lands in the Dakota Territory to white settlement by executive order.[165] Tens of thousands of settlers gathered at the border of these lands and prepared to take possession of them.[165] Cleveland believed Arthur's order to be in violation of treaties with the tribes, and rescinded it on April 17 of that year, ordering the settlers out of the territory.[165] Cleveland sent in eighteen companies of Army troops to enforce the treaties and ordered General Philip Sheridan, at the time Commanding General of the U.S. Army, to investigate the matter.[165]

Marriage and children

[edit]

Cleveland was 47 years old when he entered the White House as a bachelor. His sister Rose Cleveland joined him, acting as hostess for the first 15 months of his administration.[166] Unlike the previous bachelor president James Buchanan, Cleveland did not remain a bachelor for long. In 1885, the daughter of Cleveland's friend Oscar Folsom visited him in Washington.[167] Frances Folsom was a student at Wells College. When she returned to school, President Cleveland received her mother's permission to correspond with her, and they were soon engaged to be married.[167] The wedding occurred on June 2, 1886, in the Blue Room at the White House. Cleveland was 49 years old at the time; Frances was 21.[168] He was the second president to wed while in office[b] and remains the only president to marry in the White House. This marriage was unusual because Cleveland was the executor of Oscar Folsom's estate and had supervised Frances's upbringing after her father's death; nevertheless, the public took no exception to the match.[169] At 21 years, Frances Folsom Cleveland was and remains the youngest First Lady in history, and soon became popular for her warm personality.[170]

The Clevelands had five children: Ruth (1891–1904), Esther (1893–1980), Marion (1895–1977), Richard (1897–1974), and Francis (1903–1995). British philosopher Philippa Foot (1920–2010) was their granddaughter.[171] Ruth contracted diphtheria on January 2, 1904, and died five days after her diagnosis.[172] The Curtiss Candy Company would later assert that the "Baby Ruth" candy bar was named after her.[173] Cleveland also claimed paternity of a child with Maria Crofts Halpin, Oscar Folsom Cleveland, who was born in 1874.[174]

Administration and Cabinet

[edit]

Front row, left to right: Thomas F. Bayard, Cleveland, Daniel Manning, Lucius Q. C. Lamar

Back row, left to right: William F. Vilas, William C. Whitney, William C. Endicott, Augustus H. Garland

| First Cleveland cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Grover Cleveland | 1885–1889 |

| Vice President | Thomas A. Hendricks | 1885 |

| None | 1885–1889 | |

| Secretary of State | Thomas F. Bayard | 1885–1889 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Daniel Manning | 1885–1887 |

| Charles S. Fairchild | 1887–1889 | |

| Secretary of War | William Crowninshield Endicott | 1885–1889 |

| Attorney General | Augustus Hill Garland | 1885–1889 |

| Postmaster General | William Freeman Vilas | 1885–1888 |

| Donald M. Dickinson | 1888–1889 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | William Collins Whitney | 1885–1889 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar | 1885–1888 |

| William Freeman Vilas | 1888–1889 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture | Norman Jay Coleman | 1889 |

Judicial appointments

[edit]

During his first term, Cleveland successfully nominated two justices to the Supreme Court of the United States. The first, Lucius Q. C. Lamar, was a former Mississippi senator who served in Cleveland's Cabinet as Interior Secretary. When William Burnham Woods died, Cleveland nominated Lamar to his seat in late 1887. Lamar's nomination was confirmed by the narrow margin of 32 to 28.[175]

Chief Justice Morrison Waite died a few months later, and Cleveland nominated Melville Fuller to fill his seat on April 30, 1888. Fuller accepted. The Senate Judiciary Committee spent several months examining the little-known nominee, before the Senate confirmed the nomination 41 to 20. Cleveland was the second Democratic president to appoint a Chief Justice, after Andrew Jackson.[176][177]

Cleveland nominated 41 lower federal court judges in addition to his four Supreme Court justices. These included two judges to the United States circuit courts, nine judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, and 30 judges to the United States district courts.[citation needed]

Loss of the 1888 election to Benjamin Harrison

[edit]

The Republicans nominated Benjamin Harrison, the former U.S. Senator from Indiana for president and Levi P. Morton of New York for vice president. Cleveland was renominated at the Democratic convention in St. Louis.[178] Following Vice President Thomas A. Hendricks' death in 1885, the Democrats chose Allen G. Thurman of Ohio to be Cleveland's new running mate.[178]

The Republicans gained the upper hand in the campaign, as Cleveland's campaign was poorly managed by Calvin S. Brice and William H. Barnum, whereas Harrison had engaged more aggressive fundraisers and tacticians in Matt Quay and John Wanamaker.[179]

The Republicans campaigned heavily on the tariff issue, turning out protectionist voters in the important industrial states of the North.[180] Further, the Democrats in New York were divided over the gubernatorial candidacy of David B. Hill, weakening Cleveland's support in that swing state.[181] A letter from the British ambassador supporting Cleveland caused a scandal that cost Cleveland votes in New York.

As in 1884, the election focused on the swing states of New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Indiana. But unlike that year, when Cleveland had triumphed in all four, in 1888 he won only two, losing his home state of New York by 14,373 votes. Cleveland won a plurality of the popular vote – 48.6 percent vs. 47.8 percent for Harrison – but Harrison won the Electoral College vote easily, 233–168.[182] The Republicans won Indiana, largely as the result of a fraudulent voting practice known as Blocks of Five.[183] Cleveland continued his duties diligently until the end of the term and began to look forward to returning to private life.[184]

Between presidencies (1889–1893)

[edit]As Frances Cleveland left the White House, she told a staff member, "Now, Jerry, I want you to take good care of all the furniture and ornaments in the house, for I want to find everything just as it is now, when we come back again." When asked when she would return, she responded, "We are coming back four years from today."[185]

In the meantime, the Clevelands moved to New York City, where the former president took a position with the law firm of Bangs, Stetson, Tracy, and MacVeigh. This affiliation was more of an office-sharing arrangement, though quite compatible.[clarification needed] Cleveland's law practice brought only a moderate income, perhaps because he spent considerable time at Gray Gables, the couple's vacation home at Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts, where fishing became his obsession.[186]

In February 1890, Cleveland sold "Oak View", the 26.5-acre country estate that he had purchased for $21,500 four years earlier in a rural part of northwest Washington, D.C. He sold it for $140,000 ($4.45 million today) to Francis Newlands, who was assembling the land that would become upper Connecticut Avenue NW and the Chevy Chase suburbs.[187] Another developer soon named the area Cleveland Park.[188]

While the Clevelands lived in New York, their first child, Ruth, was born in 1891.[189]

The Harrison administration worked with Congress to pass the McKinley Tariff, an aggressively protectionist measure, and the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, which increased money backed by silver;[190] these were among policies Cleveland deplored as dangerous to the nation's financial health.[191] At first he refrained from criticizing his successor, but by 1891 Cleveland felt compelled to speak out, addressing his concerns in an open letter to a meeting of reformers in New York.[192] The "silver letter" thrust Cleveland's name back into the spotlight just as the 1892 election was approaching.[193]

Election of 1892

[edit]Nomination for president

[edit]Cleveland's enduring reputation as chief executive and his recent pronouncements on the monetary issues made him a leading contender for the Democratic nomination.[194] His leading opponent was David B. Hill, a Senator for New York.[195] Hill united the anti-Cleveland elements of the Democratic party—silverites, protectionists, and Tammany Hall—but was unable to create a coalition large enough to deny Cleveland the nomination.[195] Despite some desperate maneuvering by Hill, Cleveland was nominated on the first ballot at the party convention in Chicago.[196]

For vice president, the Democrats chose to balance the ticket with Adlai E. Stevenson of Illinois, a silverite.[197] Although the Cleveland forces preferred Isaac P. Gray of Indiana for vice president, they accepted the convention favorite.[198] As a supporter of greenbacks and free silver to inflate the currency and alleviate economic distress in the rural districts, Stevenson balanced the otherwise hard-money, gold-standard ticket headed by Cleveland.[199]

Campaign against Harrison

[edit]

The Republicans renominated President Harrison, making the 1892 election a rematch of the one four years earlier. Unlike the turbulent and controversial elections of 1876, 1884, and 1888, the 1892 election was, according to Cleveland biographer Allan Nevins, "the cleanest, quietest, and most creditable in the memory of the post-war generation",[200] in part because Harrison's wife, Caroline, was dying of tuberculosis.[201] Harrison did not personally campaign at all. Following Caroline Harrison's death on October 25, two weeks before the national election, Cleveland and all of the other candidates stopped campaigning, thus making Election Day a somber and quiet event for the whole country as well as the candidates.[citation needed]

The issue of the tariff had worked to the Republicans' advantage in 1888. Now, however, the legislative revisions of the past four years had made imported goods so expensive that by 1892, many voters favored tariff reform and were skeptical of big business.[202] Many Westerners (traditionally Republican voters), defected to James B. Weaver, the candidate of the new Populist Party. Weaver promised free silver, generous veterans' pensions, and an eight-hour work day.[203] The Tammany Hall Democrats adhered to the national ticket, allowing a united Democratic party to carry New York.[204] At the campaign's end, many Populists and labor supporters endorsed Cleveland following an attempt by the Carnegie Corporation to break the union during the Homestead strike in Pittsburgh and after a similar conflict between big business and labor at the Tennessee Coal and Iron Co.[205]

The final result was a victory for Cleveland by wide margins in both the popular and electoral votes, and it was Cleveland's third consecutive popular vote plurality. Cleveland's victory made him the first U.S. president and thus far only Democrat to serve two nonconsecutive terms.[206][c]

Second presidency (1893–1897)

[edit]Economic panic and the silver issue

[edit]

Shortly after Cleveland's second term began, the Panic of 1893 struck the stock market, leaving Cleveland and the nation to face an economic depression.[207] The panic was worsened by the acute shortage of gold that resulted from the increased coinage of silver, and Cleveland called Congress into special session to deal with the problem.[208] The debate over the coinage was as heated as ever, and the effects of the panic had driven more moderates to support repealing the coinage provisions of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act.[208] Even so, the silverites rallied their following at a convention in Chicago, and the House of Representatives debated for fifteen weeks before passing the repeal by a considerable margin.[209] In the Senate, the repeal of silver coinage was equally contentious. Cleveland, forced against his better judgment to lobby the Congress for repeal, convinced enough Democrats—and along with eastern Republicans, they formed a 48–37 majority for repeal.[210] Depletion of the Treasury's gold reserves continued, at a lesser rate, and subsequent bond issues replenished supplies of gold.[211] At the time the repeal seemed a minor setback to silverites, but it marked the beginning of the end of silver as a basis for American currency.[212]

Tariff reform

[edit]

Having succeeded in reversing the Harrison administration's silver policy, Cleveland sought next to reverse the effects of the McKinley Tariff. The Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act was introduced by West Virginian Representative William L. Wilson in December 1893.[213] After lengthy debate, the bill passed the House by a considerable margin.[214] The bill proposed moderate downward revisions in the tariff, especially on raw materials.[215] The shortfall in revenue was to be made up by an income tax of two percent on income above $4,000 (equivalent to $139,985 in 2024).[215]

The bill was next considered in the Senate, where it faced stronger opposition from key Democrats, led by Arthur Pue Gorman of Maryland, who insisted that more protection for their states' industries be added.[216] The bill passed the Senate with more than 600 amendments attached that nullified most of the reforms.[217] The Sugar Trust in particular lobbied for changes that favored it at the expense of the consumer.[218] Cleveland was outraged with the final bill, and denounced it as a disgraceful product of the control of the Senate by trusts and business interests.[219] Even so, he believed it was an improvement over the McKinley tariff and allowed it to become law without his signature.[220]

Voting rights

[edit]In 1892, Cleveland had campaigned against the Lodge Bill,[221] which would have strengthened voting rights protections through the appointing of federal supervisors of congressional elections upon a petition from the citizens of any district. The Enforcement Act of 1871 had provided for a detailed federal overseeing of the electoral process, from registration to the certification of returns. Cleveland succeeded in ushering in the 1894 repeal of this law (ch. 25, 28 Stat. 36).[222] The pendulum thus swung from stronger attempts to protect voting rights to the repealing of voting rights protections; this in turn led to unsuccessful attempts to have the federal courts protect voting rights in Giles v. Harris, 189 U.S. 475 (1903), and Giles v. Teasley, 193 U.S. 146 (1904).[citation needed]

Labor unrest

[edit]

The Panic of 1893 had damaged labor conditions across the United States, and the victory of anti-silver legislation worsened the mood of western laborers.[224] A group of workingmen led by Jacob S. Coxey began to march east toward Washington, D.C., to protest Cleveland's policies.[224] This group, known as Coxey's Army, agitated in favor of a national roads program to give jobs to workingmen, and a weakened currency to help farmers pay their debts.[224] By the time they reached Washington, only a few hundred remained, and when Coxey and other protest leaders were arrested the next day for walking on the lawn of the United States Capitol, the group scattered.[224] Even though Coxey's Army may not have been a threat to the government, it signaled a growing dissatisfaction in the West with Eastern monetary policies.[225]

Pullman Strike

[edit]The Pullman Strike had a significantly greater impact than Coxey's Army. A strike began against the Pullman Company over low wages and twelve-hour workdays, and sympathy strikes, led by American Railway Union leader Eugene V. Debs, soon followed.[226] By June 1894, 125,000 railroad workers were on strike, paralyzing the nation's commerce.[227] Because the railroads carried the mail, and because several of the affected lines were in federal receivership, Cleveland believed a federal solution was appropriate.[228] Cleveland obtained an injunction in federal court, and when the strikers refused to obey it, he sent federal troops into Chicago and 20 other rail centers.[229] "If it takes the entire army and navy of the United States to deliver a postcard in Chicago", he proclaimed, "that card will be delivered."[230] Most governors supported Cleveland except Democrat John P. Altgeld of Illinois, who became his bitter foe in 1896. Leading newspapers of both parties applauded Cleveland's actions, but the use of troops hardened the attitude of organized labor toward his administration.[231]

Just before the 1894 election, Cleveland was warned by Francis Lynde Stetson, an advisor: "We are on the eve of [a] very dark night, unless a return of commercial prosperity relieves popular discontent with what they believe [is] Democratic incompetence to make laws, and consequently [discontent] with Democratic Administrations anywhere and everywhere."[232] The warning was appropriate, for in the Congressional elections, Republicans won their biggest landslide in decades, taking full control of the House, while the Populists lost most of their support. Cleveland's factional enemies gained control of the Democratic Party in state after state, including full control in Illinois and Michigan, and made major gains in Ohio, Indiana, Iowa and other states. Wisconsin and Massachusetts were two of the few states that remained under the control of Cleveland's allies. The Democratic opposition were close to controlling two-thirds of the vote at the 1896 national convention, which they needed to nominate their own candidate. They failed for lack of unity and a national leader, as Illinois governor John Peter Altgeld had been born in Germany and was ineligible to be nominated for president.[233]

Foreign policy, 1893–1897

[edit]| "I suppose that right and justice should determine the path to be followed in treating this subject. If national honesty is to be disregarded and a desire for territorial expansion or dissatisfaction with a form of government not our own ought to regulate our conduct, I have entirely misapprehended the mission and character of our government and the behavior which the conscience of the people demands of their public servants." |

| Cleveland's message to Congress on the Hawaiian question, December 18, 1893.[234] |

When Cleveland took office, he faced the question of Hawaiian annexation. In his first term, he had supported free trade with the Hawaiian Kingdom and accepted an amendment that gave the United States a coaling and naval station in Pearl Harbor.[146] A treaty of peace and friendship existed between the United States and Hawai'i.[7] In the intervening four years, however, Honolulu businessmen of European and American ancestry had denounced Queen Liliuokalani as a tyrant who rejected constitutional government. In January 1893 they overthrew her, set up a provisional government under Sanford B. Dole, and sought to join the United States.[235]

The Harrison administration had quickly agreed with representatives of the new government on a treaty of annexation and submitted it to the Senate for approval.[235] However, the presence in Honolulu of U.S. Marines from the USS Boston while the coup unfolded, deployed at the request of U.S. Minister to Hawaii John L. Stevens, caused serious controversy.[8][236] Five days after taking office on March 9, 1893, Cleveland withdrew the treaty from the Senate and sent former Congressman James Henderson Blount to Hawai'i to investigate the situation.[237]

Cleveland agreed with Blount's report, which found the native Hawaiians to be opposed to annexation;[237] the report also found U.S. diplomatic and military involvement in the coup.[7] It included over a thousand pages of documents.[238] A firm anti-imperialist,[11] Cleveland opposed American actions in Hawaii and called for the queen to be restored; he disapproved of the new provisional government under Dole.[7][8] But matters stalled when Liliuokalani initially refused to grant amnesty as a condition for regaining her throne, saying she would either execute or banish the new leadership in Honolulu. Dole's government was in full control and rejected her demands.[239] By December 1893, the matter was still unresolved, and Cleveland referred the issue to Congress.[239] Cleveland delivered a message to Congress dated December 18, 1893, rejecting annexation and encouraging Congress to continue the American tradition of nonintervention (see excerpt at right).[234][240][241] He expressed himself in forceful terms, saying the presence of U.S. forces near the Hawaiian government building and royal palace during the coup was a "substantial wrong" and an "act of war," and lambasted the actions of minister Stevens.[7][8] Cleveland described the incident as the "subversion of the constitutional Government of Hawaii," and argued "it has been the settled policy of the United States to concede to people of foreign countries the same freedom and independence in the management of their domestic affairs that we have always claimed for ourselves."[8]

The House of Representatives adopted a resolution against annexation and voted to censure the U.S. minister.[8] However the Senate, under Democratic control but opposed to Cleveland, commissioned and produced the Morgan Report, which contradicted Blount's findings and found the overthrow was a completely internal affair.[242] Senator John Tyler Morgan of Alabama, chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, oversaw the report. It declared that the "action of the Queen in an effort to overturn the constitution of 1887...amounted to an act of abdication on her part."[243] The "constitution of 1887" mentioned in the report was the so-called Bayonet Constitution, which King Kalakaua had signed under pressure that year.[244] The Morgan Report said that the troops landed on Oahu from the USS Boston gave "no demonstration of actual hostilities," and described their conduct as "quiet" and "respectful."[243] The United States already had a presence in the region, and acquired exclusive rights to enter and establish a naval base at Pearl Harbor in 1887, when the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875 was renewed during Cleveland's first term.[245] Cleveland dropped his push to restore the queen, and went on to recognize and maintain diplomatic relations with the new Republic of Hawaii under President Dole, who took office in July 1894.[246]

Closer to home, Cleveland adopted a broad interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine that not only prohibited new European colonies, but also declared an American national interest in any matter of substance within the hemisphere.[247] When Britain and Venezuela disagreed over the boundary between Venezuela and the colony of British Guiana, Cleveland and Secretary of State Richard Olney protested.[248] British Prime Minister Robert Cecil and the British ambassador to Washington, Julian Pauncefote, misjudged how important the dispute was to Washington, and to the anti-British Irish Catholic element in Cleveland's Democratic Party. They prolonged the crisis before accepting the American demand for arbitration.[249][250] An international tribunal in 1899 awarded the bulk of the disputed territory to British Guiana.[251] But by standing with a Latin American nation against the encroachment of a colonial power, Cleveland improved relations with Latin America. The cordial manner in which the arbitration was conducted also strengthened relations with Britain and encouraged the major powers to consider arbitration as a way to settle their disputes.[252]

Military policy, 1893–1897

[edit]The second Cleveland administration was as committed to military modernization as the first, and ordered the first ships of a navy capable of offensive action. Construction continued on the Endicott program of coastal fortifications begun under Cleveland's first administration.[147][148] The adoption of the Krag–Jørgensen rifle, the U.S. Army's first bolt-action repeating rifle, was finalized.[253][254] In 1895–1896 Secretary of the Navy Hilary A. Herbert, having recently adopted the aggressive naval strategy advocated by Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, successfully proposed ordering five battleships (the Kearsarge and Illinois classes) and sixteen torpedo boats.[255][256] Completion of these ships nearly doubled the Navy's battleships and created a new torpedo boat force, which previously had only two boats. The battleships and seven of the torpedo boats were not completed until 1899–1901, after the Spanish–American War.[257]

Cancer

[edit]

In the midst of the fight for repeal of free-silver coinage in 1893, Cleveland sought the advice of the White House doctor, Robert O'Reilly,[258] about soreness on the roof of his mouth and a crater-like edge ulcer with a granulated surface on the left side of Cleveland's hard palate. Clinical samples were sent anonymously to the Army Medical Museum. The diagnosis was an epithelioma, rather than a malignant cancer.[259]

Cleveland decided to have surgery secretly, to avoid further panic that might worsen the financial depression.[260] The surgery occurred on July 1, to give Cleveland time to make a full recovery in time for the upcoming Congressional session.[261] Under the guise of a vacation cruise, Cleveland and his surgeon, Joseph D. Bryant, left for New York. The surgeons operated aboard the Oneida, a yacht owned by Cleveland's friend Elias Cornelius Benedict, as it sailed off Long Island.[262] The surgery was conducted through the President's mouth, to avoid any scars or other signs of surgery.[263] The team, sedating Cleveland with nitrous oxide and ether, successfully removed parts of his upper left jaw and hard palate.[263] The size of the tumor and the extent of the operation left Cleveland's mouth disfigured.[264] During another surgery, Cleveland was fitted with a hard rubber dental prosthesis that corrected his speech and restored his appearance.[264] A cover story about the removal of two bad teeth kept the suspicious press placated.[265] Even when a newspaper story appeared giving details of the actual operation, the participating surgeons discounted the severity of what transpired during Cleveland's vacation.[264] In 1917, one of the surgeons present on the Oneida, Dr. William Williams Keen, wrote an article detailing the operation.[266]

Cleveland enjoyed many years of life after the tumor was removed, and there was some debate as to whether it was actually malignant. Several doctors, including Dr. Keen, stated after Cleveland's death that the tumor was a carcinoma.[266] Other suggestions included ameloblastoma[267] or a benign salivary mixed tumor (also known as a pleomorphic adenoma).[268] In the 1980s, analysis of the specimen finally confirmed the tumor to be verrucous carcinoma,[269] a low-grade epithelial cancer with a low potential for metastasis.[259]

Administration and cabinet

[edit]

Front row, left to right: Daniel S. Lamont, Richard Olney, Cleveland, John G. Carlisle, Judson Harmon

Back row, left to right: David R. Francis, William Lyne Wilson, Hilary A. Herbert, Julius S. Morton

| Second Cleveland cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Grover Cleveland | 1893–1897 |

| Vice President | Adlai E. Stevenson I | 1893–1897 |

| Secretary of State | Walter Q. Gresham | 1893–1895 |

| Richard Olney | 1895–1897 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | John G. Carlisle | 1893–1897 |

| Secretary of War | Daniel S. Lamont | 1893–1897 |

| Attorney General | Richard Olney | 1893–1895 |

| Judson Harmon | 1895–1897 | |

| Postmaster General | Wilson S. Bissell | 1893–1895 |

| William Lyne Wilson | 1895–1897 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Hilary A. Herbert | 1893–1897 |

| Secretary of the Interior | M. Hoke Smith | 1893–1896 |

| David R. Francis | 1896–1897 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture | Julius Sterling Morton | 1893–1897 |

Judicial appointments

[edit]Cleveland's trouble with the Senate hindered the success of his nominations to the Supreme Court in his second term. In 1893, after the death of Samuel Blatchford, Cleveland nominated William B. Hornblower to the Court.[270] Hornblower, the head of a New York City law firm, was thought to be a qualified appointee, but his campaign against a New York machine politician had made Senator David B. Hill his enemy.[270] Further, Cleveland had not consulted the Senators before naming his appointee, leaving many who were already opposed to Cleveland on other grounds even more aggrieved.[270] The Senate rejected Hornblower's nomination on January 15, 1894, by a vote of 24 to 30.[270]

Cleveland continued to defy the Senate by next appointing Wheeler Hazard Peckham another New York attorney who had opposed Hill's machine in that state.[271] Hill used all of his influence to block Peckham's confirmation, and on February 16, 1894, the Senate rejected the nomination by a vote of 32 to 41.[271] Reformers urged Cleveland to continue the fight against Hill and to nominate Frederic R. Coudert, but Cleveland acquiesced in an inoffensive choice, that of Senator Edward Douglass White of Louisiana, whose nomination was accepted unanimously.[271] Later, in 1895, another vacancy on the Court led Cleveland to consider Hornblower again, but he declined to be nominated.[272] Instead, Cleveland nominated Rufus Wheeler Peckham, the brother of Wheeler Hazard Peckham, and the Senate confirmed the second Peckham easily.[272]

States admitted to the Union

[edit]No new states were admitted to the Union during Cleveland's first term. On February 22, 1889, 10 days before leaving office, the 50th Congress passed the Enabling Act of 1889, authorizing North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, and Washington to form state governments and to gain admission to the Union. All four officially became states in November 1889, during the first year of the Benjamin Harrison administration.[273][274] During Cleveland's second term, the 53rd United States Congress passed an Enabling Act that permitted Utah to apply for statehood. Cleveland signed it on July 16, 1894.[275][276] Utah joined the Union as the 45th state on January 4, 1896.[277]

Election of 1896 and retirement (1897–1908)

[edit]

Cleveland's agrarian and silverite enemies took control of state Democratic parties over the course of his second term, such that Cleveland's pro-gold ideology was marginalized outside of urban areas in solidly Democratic states such as Arkansas.[278] They gained control of the national Democratic Party in 1896, repudiated his administration and the gold standard, and nominated William Jennings Bryan on a free-silver platform.[279][280] Cleveland silently supported the Gold Democrats' third-party ticket that promised to defend the gold standard, limit government, and oppose high tariffs, but he declined their nomination for a third term.[281] The party won only 100,000 votes in the general election, and William McKinley, the Republican nominee, triumphed over Bryan.[282] Agrarians nominated Bryan again in 1900. In 1904, the conservatives, with Cleveland's support, regained control of the Democratic Party and nominated Alton B. Parker.[283]

After leaving the White House on March 4, 1897, Cleveland lived in retirement at his estate, Westland Mansion, in Princeton, New Jersey.[284] He was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1897.[285] For a time, he was a trustee of Princeton University, and was one of the majority of trustees who preferred the dean Andrew Fleming West's plans for the Graduate School and undergraduate living over those of Woodrow Wilson, then president of the university.[286] Cleveland consulted occasionally with President Theodore Roosevelt (1901–1909) but was financially unable to accept the chairmanship of the commission handling the Coal Strike of 1902.[287] Cleveland still made his views known in political matters. In a 1905 article in The Ladies Home Journal, Cleveland weighed in on the women's suffrage movement, writing that "sensible and responsible women do not want to vote. The relative positions to be assumed by men and women in the working out of our civilization were assigned long ago by a higher intelligence."[288]

In 1906, a group of New Jersey Democrats promoted Cleveland as a possible candidate for the United States Senate. The incumbent, John F. Dryden, was not seeking reelection, and some Democrats felt that the former president could attract the votes of some disaffected Republican legislators who might be drawn to Cleveland's statesmanship and conservatism.[289]

Death

[edit]

Cleveland's health had been declining for several years, and in the autumn of 1907, he fell seriously ill.[290] In 1908, he suffered a heart attack and died on June 24 at age 71 in his Princeton residence.[290][291] His last words were, "I have tried so hard to do right."[292] He is buried at Princeton Cemetery of the Nassau Presbyterian Church.[293]

Honors and memorials

[edit]In his first term in office, Cleveland sought a summer house to escape the heat and smells of Washington, D.C. He secretly bought a farmhouse, Oak View (or Oak Hill), in a then rural upland part of the District of Columbia, in 1886, and remodeled it into a Queen Anne style summer estate. He sold Oak View upon losing his bid for reelection in 1888. Not long thereafter, suburban residential development reached the area, which came to be known as Oak View, and then Cleveland Heights, and eventually Cleveland Park.[294] The Clevelands are depicted in local murals.[295]

Grover Cleveland Hall at Buffalo State University in New York is named after Cleveland. Cleveland was a member of the first board of directors of the then Buffalo Normal School.[296] Grover Cleveland Middle School in his birthplace, Caldwell, New Jersey, was named for him, as is Grover Cleveland High School (Buffalo, New York), the town of Cleveland, Mississippi, and Mount Cleveland in Alaska.[297]

In 1895, he became the first U.S. president who was filmed.[298] The first U.S. postage stamp to honor Cleveland appeared in 1923. His only two subsequent stamp appearances have been in issues devoted to the full roster of U.S. Presidents, released, respectively, in 1938[299] and 1986.[300]

Cleveland's portrait was on the U.S. $1000 bill of series 1928 and series 1934. He also appeared on the $20 Federal Reserve Note of series 1914 and the $20 Federal Reserve Bank Note of series 1915 and series 1918. Since he was both the 22nd and 24th president, he was featured on two separate dollar coins released in 2012 as part of the Presidential $1 Coin Act of 2005.[301] In 2013, Cleveland was inducted into the New Jersey Hall of Fame.[302]

|

|

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Vice President Hendricks died in office. As this was prior to the adoption of the Twenty-fifth Amendment in 1967, a vacancy in the office of vice president was not filled until the next ensuing election and inauguration.

- ^ John Tyler, who married his second wife Julia Gardiner in 1844, was the first.

- ^ Republican Donald Trump was later elected to a second nonconsecutive term in 2024 (after losing in 2020).

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b "Grover Cleveland Birthplace". National Park Service. Archived from the original on April 4, 2024. Retrieved May 18, 2023.

- ^ Blum, 527

- ^ Jeffers, 8–12; Nevins, 4–5; Beito and Beito

- ^ "Interstate Commerce Act (1887)". National Archives and Records Administration. September 8, 2021. Retrieved December 31, 2024.

- ^ a b Schultz, Jeffrey D.; Aoki, Andrew L.; Haynie, Kerry L.; McCulloch, Anne M., eds. (2000). Encyclopedia of Minorities in American Politics. Vol. 2: Hispanic Americans and Native Americans. Greenwood. p. 608. ISBN 9781573561495.

- ^ a b Smith, Stacey Vanek (July 26, 2019). "The U.S. Has Nearly 1.9 Billion Acres of Land. Here's How It is Used". NPR.

- ^ a b c d e Williams, Ronald Jr. (2021). "Special Rights of Citizenship and the Perpetuation of Oligarchic Rule in the Republic of Hawai'i, 1894–1898". Hawaiian Journal of History. 55 (1): 71–110. doi:10.1353/hjh.2021.0002. ISSN 2169-7639. S2CID 244917322.

- ^ a b c d e f "Grover Cleveland on the Overthrow of Hawaii's Royal Government". University of Houston. 1893. Archived from the original on December 15, 2023. Retrieved May 16, 2023.

- ^ a b Tugwell, 220–249

- ^ Haynes, Stan M. (2015). President-Making in the Gilded Age: The Nominating Conventions of 1876–1900. McFarland. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-4766-2305-4.

- ^ a b "The Spanish-American War: The United States Becomes a World Power". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on December 11, 2023. Retrieved May 16, 2023.

In June 1898, the American Anti-Imperialist League was formed ... Its members included former President Grover Cleveland.

- ^ Nevins, 8–10

- ^ Graff, 3–4; Nevins, 8–10

- ^ Graff, 3–4

- ^ Nevins, Allan (1933). Grover Cleveland; a study in courage. Dodd, Mead & Co. p. 6. Retrieved August 20, 2025.

The Clevelands had originated in northeastern England. The first of the name to arrive in America was a Moses Cleveland who in 1635 reached Massachusetts from Ipswich.

- ^ Nevins, 9

- ^ Graff, 7

- ^ Nevins, 10; Graff, 3

- ^ Nevins, 11; Graff, 8–9

- ^ Nevins, 11

- ^ Jeffers, 17

- ^ Nevins, 17–19

- ^ Tugwell, 14

- ^ a b Nevins, 21

- ^ Nevins, 18–19; Jeffers, 19

- ^ Nevins, 23–27

- ^ Nevins, 27–33

- ^ Nevins, 31–36

- ^ Graff, 11

- ^ a b c Graff, 14

- ^ Graff, 14–15

- ^ Graff, 15; Nevins, 46

- ^ Graff, 14; Nevins, 51–52

- ^ a b Nevins, 52–53

- ^ Nevins, 54

- ^ Nevins, 54–55

- ^ Nevins, 55–56

- ^ Nevins, 56

- ^ Tugwell, 26

- ^ Nevins, 44–45

- ^ Tugwell, 32

- ^ a b Nevins, 58

- ^ Jeffers, 33

- ^ Nelson, Julie (2003). American Presidents Year by Year. Routledge. p. 334. ISBN 978-0-7656-8046-4.

- ^ Tugwell, 36

- ^ a b c Jeffers, 34; Nevins, 61–62

- ^ "The Execution of John Gaffney". The Buffalonian. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. Retrieved March 27, 2008.

- ^ Jeffers, 36; Nevins, 64

- ^ "Timeline | Articles and Essays | Grover Cleveland Papers | Digital Collections". www.loc.gov. Library of Congress. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Nevins, 66–71

- ^ Nevins, 78

- ^ "Sexual misconduct allegations against presidents have a long history; George H.W. Bush is latest". Newsweek. October 25, 2017.

- ^ Keiles, Jamie Lauren (August 26, 2015). "Grover Cleveland, a Rapist President". Vice.

- ^ Serratore, Angela (September 26, 2013). "President Cleveland's Problem Child". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ a b c d Huck, C., 2017. "The Halpin Affair: How Cleveland went from Scandal to Success". Wittenberg History Journal, vol. 46, p. 5, 8.

- ^ Lachman, Charles (May 23, 2011). "Grover Cleveland's Sex Scandal: The Most Despicable in American Political History". The Daily Beast. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- ^ a b Hamilton, Neil A. (2005). Presidents: A Biographical Dictionary. Infobase Publishing. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-4381-0816-2.

- ^ a b c Henry F. Graff (2002). Grover Cleveland: The American Presidents Series: The 22nd and 24th President, 1885–1889 and 1893–1897. Henry Holt and Company. pp. 60–63. ISBN 978-0-8050-6923-5.

- ^ Nevins, 79; Graff, 18–19; Jeffers, 42–45; Welch, 24

- ^ Nevins, 79–80; Graff, 18–19; Welch, 24

- ^ a b Nevins, 80–81

- ^ Nevins, 83

- ^ "Timeline – Articles and Essays – Grover Cleveland Papers – Digital Collections". The Library of Congress. October 29, 1947. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ^ Graff, 19; Jeffers, 46–50

- ^ a b Nevins, 84–86

- ^ Nevins, 85

- ^ Nevins, 86

- ^ Tugwell, 58

- ^ Nevins, 94–95; Jeffers, 50–51

- ^ a b Nevins, 94–99; Graff, 26–27

- ^ Tugwell, 68–70

- ^ Graff, 26; Nevins, 101–103

- ^ Nevins, 103–104

- ^ Nevins, 105

- ^ Graff, 28

- ^ Graff, 35

- ^ Graff, 35–36

- ^ Nevins, 114–116

- ^ a b c Nevins, 116–117

- ^ a b Nevins, 117–118

- ^ Nevins, 125–126

- ^ Tugwell, 77

- ^ Tugwell, 73

- ^ Nevins, 138–140

- ^ a b Nevins, 185–186; Jeffers, 96–97

- ^ Tugwell, 88–89

- ^ a b c Nevins, 146–147

- ^ Nevins, 147

- ^ Nevins, 152–153; Graff, 51–53

- ^ Nevins, 153

- ^ Nevins, 154; Graff, 53–54

- ^ Tugwell, 80

- ^ Summers, passim; Grossman, 31

- ^ Tugwell, 84

- ^ a b Nevins, 156–159; Graff, 55

- ^ Nevins, 187–188

- ^ Tugwell, 93

- ^ a b Nevins, 159–162; Graff, 59–60

- ^ Graff, 59; Jeffers, 111; Nevins, 177, Welch, 34

- ^ Jacoby, Jeff (February 15, 2015). "'Grover the good'—the most honest president of them all". The Boston Globe. pp. 2–15. Retrieved November 8, 2024.

- ^ Lachman, Charles (2011). "Chapter 9 – "A Terrible Tale"". A Secret Life: The Sex, Lies, and Scandals of President Grover Cleveland. Skyhorse Publishing. pp. 195–216. ISBN 978-1-61608-275-8. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ^ Tugwell, 90

- ^ Lachman, Charles (2011). A Secret Life: The Sex, Lies, and Scandals of President Grover Cleveland. Skyhorse Publishing. pp. 285–288. ISBN 978-1-61608-275-8.

- ^ Welch, 33

- ^ Nevins, 170–171

- ^ Nevins, 170

- ^ Nevins, 181–184

- ^ Tugwell, 94–95

- ^ a b Leip, David. "1884 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved January 27, 2008., "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved January 27, 2008.

- ^ Graff, 64

- ^ Nevins, 208–211

- ^ Nevins, 214–217

- ^ Graff, 83

- ^ Tugwell, 100

- ^ Nevins, 238–241; Welch, 59–60

- ^ Nevins, 354–357; Graff, 85

- ^ Nevins, 217–223; Graff, 77

- ^ Nevins, 223–228

- ^ Tugwell, 130–134

- ^ Graff, 85

- ^ Nevins, 326–328; Graff, 83–84

- ^ Nevins, 300–331; Graff, 83

- ^ See List of United States presidential vetoes

- ^ a b Nevins, 331–332; Graff, 85