Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Progesterone (medication)

View on Wikipedia

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Prometrium, Utrogestan, Endometrin, others |

| Other names | P4; Pregnenedione; Pregn-4-ene-3,20-dione[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a604017 |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, sublingual, topical, vaginal, rectal, intramuscular, subcutaneous, intrauterine |

| Drug class | Progestogen; Antimineralocorticoid; Neurosteroid |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Oral: <2.4%[5] Vaginal (micronized insert): 4–8%[6][7][8] |

| Protein binding | 98–99%:[9][10] • Albumin: 80% • CBG: 18% • SHBG: <1% • Free: 1–2% |

| Metabolism | Mainly liver: • 5α- and 5β-reductase • 3α- and 3β-HSD • 20α- and 20β-HSD • Conjugation • 17α-Hydroxylase • 21-Hydroxylase • CYPs (e.g., CYP3A4) |

| Metabolites | • Dihydroprogesterones • Pregnanolones • Pregnanediols • 20α-Hydroxyprogesterone • 17α-Hydroxyprogesterone • Pregnanetriols • 11-Deoxycorticosterone (and glucuronide/sulfate conjugates) |

| Elimination half-life | • Oral: 5 hours (with food)[11] * Sublingual: 6–7 hours[12] • Vaginal: 14–50 hours[13][12] • Topical: 30–40 hours[14] • IM: 20–28 hours[15][13][16] • SC: 13–18 hours[16] • IV: 3–90 minutes[17] |

| Excretion | Bile and urine[18][19] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H30O2 |

| Molar mass | 314.469 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Specific rotation | [α]D25 = +172 to +182° (2% in dioxane, β-form) |

| Melting point | 126 °C (259 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Progesterone (P4), sold under the brand name Prometrium among others, is a medication and naturally occurring steroid hormone.[20] It is a progestogen and is used in combination with estrogens mainly in hormone therapy for menopausal symptoms and low sex hormone levels in women.[20][21] It is also used in women to support pregnancy and fertility and to treat gynecological disorders.[22][23][24][25] Progesterone can be taken by mouth, vaginally, and by injection into muscle or fat, among other routes.[20] A progesterone vaginal ring and progesterone intrauterine device used for birth control also exist in some areas of the world.[26][27]

Progesterone is well tolerated and often produces few or no side effects.[28] However, a number of side effects are possible, for instance mood changes.[28] If progesterone is taken by mouth or at high doses, certain central side effects including sedation, sleepiness, and cognitive impairment can also occur.[28][20] The medication is a naturally occurring progestogen and hence is an agonist of the progesterone receptor (PR), the biological target of progestogens like endogenous progesterone.[20] It opposes the effects of estrogens in various parts of the body like the uterus and also blocks the effects of the hormone aldosterone.[20][29] In addition, progesterone has neurosteroid effects in the brain.[20]

Progesterone was first isolated in pure form in 1934.[30][31] It first became available as a medication later that year.[32][33] Oral micronized progesterone (OMP), which allowed progesterone to be taken by mouth, was introduced in 1980.[33][22][34] A large number of synthetic progestogens, or progestins, have been derived from progesterone and are used as medications as well.[20] Examples include medroxyprogesterone acetate and norethisterone.[20] In 2023, it was the 117th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 5 million prescriptions.[35][36]

Medical uses

[edit]Menopause

[edit]Progesterone is used in combination with an estrogen as a component of menopausal hormone therapy for the treatment of menopausal symptoms in peri- and postmenopausal women.[20][37] It is used specifically to provide endometrial protection against unopposed estrogen-induced endometrial hyperplasia and cancer in women with intact uteruses.[20][37] A 2016 systematic review of endometrial protection with progesterone recommended 100 mg/day continuous oral progesterone, 200 mg/day cyclic oral progesterone, 45 to 100 mg/day cyclic vaginal progesterone, and 100 mg alternate-day vaginal progesterone.[29][38] Twice-weekly 100 mg vaginal progesterone was also recommended, but more research is needed on this dose and endometrial monitoring may be advised.[29][38] Transdermal progesterone was not recommended for endometrial protection.[29][38]

The REPLENISH trial was the first adequately powered study to show that continuous 100 mg/day oral progesterone with food provides adequate endometrial protection.[39][40][37][41] Cyclic 200 mg/day oral progesterone has also been found to be effective in the prevention of endometrial hyperplasia, for instance in the Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) trial.[39][42][38] However, the PEPI trial was not adequately powered to fully quantify endometrial hyperplasia or cancer risk.[39] No adequately powered studies have assessed endometrial protection with vaginal progesterone.[39] In any case, the Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol (ELITE) found that cyclic 45 mg/day vaginal progesterone gel showed no significant difference from placebo in endometrial cancer rates.[39][29] Due to the vaginal first-pass effect, low doses of vaginal progesterone may allow for adequate endometrial protection.[22][43][20] Although not sufficiently powered, various other smaller studies have also found endometrial protection with oral or vaginal progesterone.[39][42][38][44] There is inadequate evidence for endometrial protection with transdermal progesterone cream.[29][22][45][46]

Oral progesterone has been found to significantly reduce hot flashes relative to placebo.[39][47] The combination of an estrogen and oral progesterone likewise reduces hot flashes.[39][37] Estrogen plus oral progesterone has been found to significantly improve quality of life.[39][37] The combination of an estrogen and 100 to 300 mg/day oral progesterone has been found to improve sleep outcomes.[39][37][47] Moreover, sleep was improved to a significantly better extent than estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone acetate.[39] This may be attributable to the sedative neurosteroid effects of progesterone.[39] Reduction of hot flashes may also help to improve sleep outcomes.[39] Based on animal research, progesterone may be involved in sexual function in women.[48][49] However, very limited clinical research suggests that progesterone does not improve sexual desire or function in women.[50]

The combination of an estrogen and oral progesterone has been found to improve bone mineral density (BMD) to a similar extent as an estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone acetate.[39] Progestogens, including progesterone, may have beneficial effects on bone independent of those of estrogens, although more research is required to confirm this notion.[51] The combination of an estrogen and oral or vaginal progesterone has been found to improve cardiovascular health in women in early menopause but not in women in late menopause.[39] Estrogen therapy has a favorable influence on the blood lipid profile, which may translate to improved cardiovascular health.[39][20] The addition of oral or vaginal progesterone has neutral or beneficial effects on these changes.[39][37][47] This is in contrast to various progestins, which are known to antagonize the beneficial effects of estrogens on blood lipids.[20][39] Progesterone, both alone and in combination with an estrogen, has been found to have beneficial effects on skin and to slow the rate of skin aging in postmenopausal women.[52][53]

In the French E3N-EPIC observational study, the risk of diabetes was significantly lower in women on menopausal hormone therapy, including with the combination of an oral or transdermal estrogen and oral progesterone or a progestin.[54]

Transgender women

[edit]Progesterone is used as a component of feminizing hormone therapy for transgender women in combination with estrogens and often antiandrogens.[55][21][56] However, the addition of progestogens to HRT for transgender women is controversial and their role is unclear.[55][21] Some patients and clinicians believe anecdotally that progesterone may enhance breast development, improve mood, regulate sleep, and increase sex drive.[21] However, there is a lack of evidence from well-designed studies to support these notions at present.[21] In addition, progestogens can produce undesirable side effects, although bioidentical progesterone may be safer and better tolerated than synthetic progestogens like medroxyprogesterone acetate.[55][57]

Because some believe that progestogens are necessary for full breast development, progesterone is sometimes used in transgender women with the intention of enhancing breast development.[55][58][57] However, a 2014 review concluded the following on the topic of progesterone for enhancing breast development in transgender women:[58]

Our knowledge concerning the natural history and effects of different cross-sex hormone therapies on breast development in [transgender] women is extremely sparse and based on low quality of evidence. Current evidence does not provide evidence that progestogens enhance breast development in [transgender] women. Neither do they prove the absence of such an effect. This prevents us from drawing any firm conclusion at this moment and demonstrates the need for further research to clarify these important clinical questions.[58]

Data on menstruating women shows there is no correlation between water retention, and levels of progesterone or estrogen.[59] Despite this, some theorise progesterone might cause temporary breast enlargement due to local fluid retention, and may thus give a misleading appearance of breast growth.[60][61] Aside from a hypothetical involvement in breast development, progestogens are not otherwise known to be involved in physical feminization.[57][55]

Pregnancy support

[edit]Vaginally dosed progesterone is being investigated as potentially beneficial in preventing preterm birth in women at risk for preterm birth. The initial study by Fonseca suggested that vaginal progesterone could prevent preterm birth in women with a history of preterm birth.[62] According to a recent study, women with a short cervix that received hormonal treatment with a progesterone gel had their risk of prematurely giving birth reduced. The hormone treatment was administered vaginally every day during the second half of a pregnancy.[63] A subsequent and larger study showed that vaginal progesterone was no better than placebo in preventing recurrent preterm birth in women with a history of a previous preterm birth,[64] but a planned secondary analysis of the data in this trial showed that women with a short cervix at baseline in the trial had benefit in two ways: a reduction in births less than 32 weeks and a reduction in both the frequency and the time their babies were in intensive care.[65]

In another trial, vaginal progesterone was shown to be better than placebo in reducing preterm birth prior to 34 weeks in women with an extremely short cervix at baseline.[66] An editorial by Roberto Romero discusses the role of sonographic cervical length in identifying patients who may benefit from progesterone treatment.[67] A meta-analysis published in 2011 found that vaginal progesterone cut the risk of premature births by 42 percent in women with short cervixes.[68][69] The meta-analysis, which pooled published results of five large clinical trials, also found that the treatment cut the rate of breathing problems and reduced the need for placing a baby on a ventilator.[70]

Fertility support

[edit]Progesterone is used for luteal support in assisted reproductive technology (ART) cycles such as in vitro fertilization (IVF).[24][71] It is also used to correct luteal phase deficiency to prepare the endometrium for implantation in infertility therapy and is used to support early pregnancy.[72][73]

Birth control

[edit]A progesterone vaginal ring is available for birth control when breastfeeding in a number of areas of the world.[26] An intrauterine device containing progesterone has also been marketed under the brand name Progestasert for birth control, including previously in the United States.[74]

Gynecological disorders

[edit]Progesterone is used to control persistent anovulatory bleeding.[75][76][77]

Other uses

[edit]Progesterone is of unclear benefit for the reversal of mifepristone-induced abortion.[78] Evidence is insufficient to support use in traumatic brain injury.[79]

Progesterone has been used as a topical medication applied to the scalp to treat female and male pattern hair loss.[80][81][82][83][84] Variable effectiveness has been reported, but overall its effectiveness for this indication in both sexes has been poor.[81][82][85][84]

Breast pain

[edit]Progesterone is approved under the brand name Progestogel as a 1% topical gel for local application to the breasts to treat breast pain in certain countries.[86][87][22] It is not approved for systemic therapy.[88][86] It has been found in clinical studies to inhibit estrogen-induced proliferation of breast epithelial cells and to abolish breast pain and tenderness in women with the condition.[22] However, in one small study in women with cyclic breast pain it was ineffective.[89] Vaginal progesterone has also been found to be effective in the treatment of breast pain and tenderness.[89]

Premenstrual syndrome

[edit]Historically, progesterone has been widely used in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome.[90] A 2012 Cochrane review found insufficient evidence for or against the effectiveness of progesterone for this indication.[91] Another review of 10 studies found that progesterone was not effective for this condition, although it stated that insufficient evidence is available currently to make a definitive statement on progesterone in premenstrual syndrome.[90][92]

Catamenial epilepsy

[edit]Progesterone can be used to treat catamenial epilepsy by supplementation during certain periods of the menstrual cycle.[93]

Available forms

[edit]Progesterone is available in a variety of different forms, including oral capsules; sublingual tablets; vaginal capsules, tablets, gels, suppositories, and rings; rectal suppositories; oil solutions for intramuscular injection; and aqueous solutions for subcutaneous injection.[94][20] A 1% topical progesterone gel is approved for local application to the breasts to treat breast pain, but is not indicated for systemic therapy.[88][86] Progesterone was previously available as an intrauterine device for use in hormonal contraception, but this formulation was discontinued.[94] Progesterone is also limitedly available in combination with estrogens such as estradiol and estradiol benzoate for use by intramuscular injection.[95][96]

In addition to approved pharmaceutical products, progesterone is available in unregulated custom compounded and over-the-counter formulations like systemic transdermal creams and other preparations.[97][98][45][46][99] The systemic efficacy of transdermal progesterone is controversial and has not been demonstrated.[45][46][99]

| Route | Form | Dose | Brand name | Availability[b] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | Capsule | 100, 200, 300 mg | Prometrium[c] | Widespread |

| Tablet (SR) | 200, 300, 400 mg | Dubagest SR[c] | India | |

| Sublingual | Tablet | 10, 25, 50, 100 mg | Luteina[c] | Europe[d] |

| Transdermal | Gel[e] | 1% (25 mg) | Progestogel | Europe |

| Vaginal | Capsule | 100, 200 mg | Utrogestan | Widespread |

| Tablet | 100 mg | Endometrin[c] | Widespread | |

| Gel | 4, 8% (45, 90 mg) | Crinone[c] | Widespread | |

| Suppository | 200, 400 mg | Cyclogest | Europe | |

| Ring | 10 mg/day[f] | Fertiring[c] | South America[g] | |

| Rectal | Suppository | 200, 400 mg | Cyclogest | Europe |

| Uterine | IUD | 38 mg | Progestasert | Discontinued |

| Intramuscular injection |

Oil solution | 2, 5, 10, 20, 25, 50, 100 mg/mL |

Proluton[c] | Widespread |

| Aq. susp. | 12.5, 30, 100 mg/mL | Agolutin[c] | Europe[h] | |

| Emulsion | 5, 10, 25 mg/mL | Di-Pro-Emulsion | Discontinued | |

| Microsph. | 20, 100 mg/mL | ProSphere[c] | Mexico | |

| Subcutaneous | Aq. soln. (inj.) | 25 mg/vial | Prolutex | Europe |

| Implant | 50, 100 mg | Proluton[c] | Discontinued | |

| Intravenous | Aq. soln. (inj.) | 20 mg/mL | Primolut | Discontinued |

Sources and footnotes:

| ||||

Contraindications

[edit]Contraindications of progesterone include hypersensitivity to progesterone or progestogens, prevention of cardiovascular disease (a Black Box warning), thrombophlebitis, thromboembolic disorder, cerebral hemorrhage, impaired liver function or disease, breast cancer, reproductive organ cancers, undiagnosed vaginal bleeding, missed menstruations, miscarriage, or a history of these conditions.[111][112] Progesterone should be used with caution in people with conditions that may be adversely affected by fluid retention such as epilepsy, migraine headaches, asthma, cardiac dysfunction, and renal dysfunction.[111][112] It should also be used with caution in patients with anemia, diabetes mellitus, a history of depression, previous ectopic pregnancy, and unresolved abnormal Pap smear.[111][112] Use of progesterone is not recommended during pregnancy and breastfeeding.[112] However, the medication has been deemed usually safe in breastfeeding by the American Academy of Pediatrics, but should not be used during the first four months of pregnancy.[111] Some progesterone formulations contain benzyl alcohol, and this may cause a potentially fatal "gasping syndrome" if given to premature infants.[111]

Side effects

[edit]Progesterone is well tolerated, and many clinical studies have reported no side effects.[28] Side effects of progesterone may include abdominal cramps, back pain, breast tenderness, constipation, nausea, dizziness, edema, vaginal bleeding, hypotension, fatigue, dysphoria, depression, and irritability, among others.[28] Central nervous system depression, such as sedation and cognitive/memory impairment, can also occur.[28][20]

Vaginal progesterone may be associated with vaginal irritation, itchiness, and discharge, decreased libido, painful sexual intercourse, vaginal bleeding or spotting in association with cramps, and local warmth or a "feeling of coolness" without discharge.[28] Intramuscular injection may cause mild-to-moderate pain at the site of injection.[28] High intramuscular doses of progesterone have been associated with increased body temperature, which may be alleviated with paracetamol treatment.[28]

Progesterone lacks undesirable off-target hormonal activity, in contrast to various progestins.[20] As a result, it is not associated with androgenic, antiandrogenic, estrogenic, or glucocorticoid effects.[20] Conversely, progesterone can still produce side effects related to its antimineralocorticoid and neurosteroid activity.[20] Compared to the progestin medroxyprogesterone acetate, there are fewer reports of breast tenderness with progesterone.[28] In addition, the magnitude and duration of vaginal bleeding with progesterone are reported to be lower than with medroxyprogesterone acetate.[28]

Central depression

[edit]Progesterone can produce central nervous system depression as an adverse effect, particularly with oral administration or with high doses of progesterone.[20][28] These side effects may include drowsiness, sedation, sleepiness, fatigue, sluggishness, reduced vigor, dizziness, lightheadedness, confusion, and cognitive, memory, and/or motor impairment.[28][113][114] Limited available evidence has shown minimal or no adverse influence on cognition with oral progesterone (100–600 mg), vaginal progesterone (45 mg gel), or progesterone by intramuscular injection (25–200 mg).[115][39][28][116][117] However, high doses of oral progesterone (300–1200 mg), vaginal progesterone (100–200 mg), and intramuscular progesterone (100–200 mg) have been found to result in dose-dependent fatigue, drowsiness, and decreased vigor.[28][116][115][20][118][117][119] Moreover, high single doses of oral progesterone (1200 mg) produced significant cognitive and memory impairment.[28][118][117][20] Intravenous infusion of high doses of progesterone (e.g., 500 mg) has been found to induce deep sleep in humans.[120][17][121][122] Some individuals are more sensitive and can experience considerable sedative and hypnotic effects at lower doses of oral progesterone (e.g., 400 mg).[20][123]

Sedation and cognitive and memory impairment with progesterone are attributable to its inhibitory neurosteroid metabolites.[20] These metabolites occur to a greater extent with oral progesterone, and may be minimized by switching to a parenteral route.[20][16][124] Progesterone can also be taken before bed to avoid these side effects and to help with sleep.[113] The neurosteroid effects of progesterone are unique to progesterone and are not shared with progestins.[20]

Breast cancer

[edit]Breast cell proliferation has been found to be significantly increased by the combination of an oral estrogen plus cyclic medroxyprogesterone acetate in postmenopausal women but not by the combination of transdermal estradiol plus oral progesterone.[39] Studies of topical estradiol and progesterone applied to the breasts for 2 weeks have been found to result in highly pharmacological local levels of estradiol and progesterone.[39][125] These studies have assessed breast proliferation markers and have found increased proliferation with estradiol alone, decreased proliferation with progesterone, and no change in proliferation with estradiol and progesterone combined.[39] In the Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) trial, the combination of estrogen and cyclic oral progesterone resulted in a higher mammographic breast density than estrogen alone (3.1% vs. 0.9%) but a non-significantly lower breast density than the combination of estrogen and cyclic or continuous medroxyprogesterone acetate (3.1% vs. 4.4–4.6%).[39] Higher breast density is a strong known risk factor for breast cancer.[126] Other studies have had mixed findings however.[127] A 2018 systematic review reported that breast density with an estrogen plus oral progesterone was significantly increased in three studies and unchanged in two studies.[127] Changes in breast density with progesterone appear to be less than with the compared progestins.[127]

In large short-term observational studies, estrogen alone and the combination of estrogen and oral progesterone have generally not been associated with an increased risk of breast cancer.[39][128][129][38] Conversely, the combination of estrogen and almost any progestin, such as medroxyprogesterone acetate or norethisterone acetate, has been associated with an increased risk of breast cancer.[39][128][38][129][130] The only exception among progestins is dydrogesterone, which has shown similar risk to that of oral progesterone.[39] Breast cancer risk with estrogen and progestin therapy is duration-dependent, with the risk being significantly greater with more than 5 years of exposure relative to less than 5 years.[128] In contrast to shorter-term studies, the longer-term observations (>5 years) of the French E3N study showed significant associations of both estrogen plus oral progesterone and estrogen plus dydrogesterone with higher breast cancer risk, similarly to estrogen plus other progestogens.[39] Oral progesterone has very low bioavailability and has relatively weak progestogenic effects.[130][131] The delayed onset of breast cancer risk with estrogen plus oral progesterone is potentially consistent with a weak proliferative effect of oral progesterone on the breasts.[130][131] As such, a longer duration of exposure may be necessary for a detectable increase in breast cancer risk to occur.[130][131] In any case, the risk remains lower than that with most progestins.[39][129] A 2018 systematic review of progesterone and breast cancer concluded that short-term use (<5 years) of an estrogen plus progesterone is not associated with a significant increase in risk of breast cancer but that long-term use (>5 years) is associated with greater risk.[127] The conclusions for progesterone were the same in a 2019 meta-analysis of the worldwide epidemiological evidence by the Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer (CGHFBC).[132]

Most data on breast density changes and breast cancer risk are with oral progesterone.[127] Data on breast safety with vaginal progesterone are scarce.[127] The Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol (ELITE) was a randomized controlled trial of about 650 postmenopausal women who used estradiol and 45 mg/day cyclic vaginal progesterone.[127][133] Incidence of breast cancer was reported as an adverse effect.[127][133] The absolute incidences were 10 cases in the estradiol plus vaginal progesterone group and 8 cases in the control group.[127][133] However, the study was not adequately powered for quantifying breast cancer risk.[127][133]

| Therapy | <5 years | 5–14 years | 15+ years | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | RR (95% CI) | Cases | RR (95% CI) | Cases | RR (95% CI) | |

| Estrogen alone | 1259 | 1.18 (1.10–1.26) | 4869 | 1.33 (1.28–1.37) | 2183 | 1.58 (1.51–1.67) |

| By estrogen | ||||||

| Conjugated estrogens | 481 | 1.22 (1.09–1.35) | 1910 | 1.32 (1.25–1.39) | 1179 | 1.68 (1.57–1.80) |

| Estradiol | 346 | 1.20 (1.05–1.36) | 1580 | 1.38 (1.30–1.46) | 435 | 1.78 (1.58–1.99) |

| Estropipate (estrone sulfate) | 9 | 1.45 (0.67–3.15) | 50 | 1.09 (0.79–1.51) | 28 | 1.53 (1.01–2.33) |

| Estriol | 15 | 1.21 (0.68–2.14) | 44 | 1.24 (0.89–1.73) | 9 | 1.41 (0.67–2.93) |

| Other estrogens | 15 | 0.98 (0.46–2.09) | 21 | 0.98 (0.58–1.66) | 5 | 0.77 (0.27–2.21) |

| By route | ||||||

| Oral estrogens | – | – | 3633 | 1.33 (1.27–1.38) | – | – |

| Transdermal estrogens | – | – | 919 | 1.35 (1.25–1.46) | – | – |

| Vaginal estrogens | – | – | 437 | 1.09 (0.97–1.23) | – | – |

| Estrogen and progestogen | 2419 | 1.58 (1.51–1.67) | 8319 | 2.08 (2.02–2.15) | 1424 | 2.51 (2.34–2.68) |

| By progestogen | ||||||

| (Levo)norgestrel | 343 | 1.70 (1.49–1.94) | 1735 | 2.12 (1.99–2.25) | 219 | 2.69 (2.27–3.18) |

| Norethisterone acetate | 650 | 1.61 (1.46–1.77) | 2642 | 2.20 (2.09–2.32) | 420 | 2.97 (2.60–3.39) |

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate | 714 | 1.64 (1.50–1.79) | 2012 | 2.07 (1.96–2.19) | 411 | 2.71 (2.39–3.07) |

| Dydrogesterone | 65 | 1.21 (0.90–1.61) | 162 | 1.41 (1.17–1.71) | 26 | 2.23 (1.32–3.76) |

| Progesterone | 11 | 0.91 (0.47–1.78) | 38 | 2.05 (1.38–3.06) | 1 | – |

| Promegestone | 12 | 1.68 (0.85–3.31) | 19 | 2.06 (1.19–3.56) | 0 | – |

| Nomegestrol acetate | 8 | 1.60 (0.70–3.64) | 14 | 1.38 (0.75–2.53) | 0 | – |

| Other progestogens | 12 | 1.70 (0.86–3.38) | 19 | 1.79 (1.05–3.05) | 0 | – |

| By progestogen frequency | ||||||

| Continuous | – | – | 3948 | 2.30 (2.21–2.40) | – | – |

| Intermittent | – | – | 3467 | 1.93 (1.84–2.01) | – | – |

| Progestogen alone | 98 | 1.37 (1.08–1.74) | 107 | 1.39 (1.11–1.75) | 30 | 2.10 (1.35–3.27) |

| By progestogen | ||||||

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate | 28 | 1.68 (1.06–2.66) | 18 | 1.16 (0.68–1.98) | 7 | 3.42 (1.26–9.30) |

| Norethisterone acetate | 13 | 1.58 (0.77–3.24) | 24 | 1.55 (0.88–2.74) | 6 | 3.33 (0.81–13.8) |

| Dydrogesterone | 3 | 2.30 (0.49–10.9) | 11 | 3.31 (1.39–7.84) | 0 | – |

| Other progestogens | 8 | 2.83 (1.04–7.68) | 5 | 1.47 (0.47–4.56) | 1 | – |

| Miscellaneous | ||||||

| Tibolone | – | – | 680 | 1.57 (1.43–1.72) | – | – |

| Notes: Meta-analysis of worldwide epidemiological evidence on menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk by the Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer (CGHFBC). Fully adjusted relative risks for current versus never-users of menopausal hormone therapy. Source: See template. | ||||||

| Study | Therapy | Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| E3N-EPIC: Fournier et al. (2005) | Estrogen alone | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) |

| Estrogen plus progesterone Transdermal estrogen Oral estrogen |

0.9 (0.7–1.2) 0.9 (0.7–1.2) No events | |

| Estrogen plus progestin Transdermal estrogen Oral estrogen |

1.4 (1.2–1.7) 1.4 (1.2–1.7) 1.5 (1.1–1.9) | |

| E3N-EPIC: Fournier et al. (2008) | Oral estrogen alone | 1.32 (0.76–2.29) |

| Oral estrogen plus progestogen Progesterone Dydrogesterone Medrogestone Chlormadinone acetate Cyproterone acetate Promegestone Nomegestrol acetate Norethisterone acetate Medroxyprogesterone acetate |

Not analyzeda 0.77 (0.36–1.62) 2.74 (1.42–5.29) 2.02 (1.00–4.06) 2.57 (1.81–3.65) 1.62 (0.94–2.82) 1.10 (0.55–2.21) 2.11 (1.56–2.86) 1.48 (1.02–2.16) | |

| Transdermal estrogen alone | 1.28 (0.98–1.69) | |

| Transdermal estrogen plus progestogen Progesterone Dydrogesterone Medrogestone Chlormadinone acetate Cyproterone acetate Promegestone Nomegestrol acetate Norethisterone acetate Medroxyprogesterone acetate |

1.08 (0.89–1.31) 1.18 (0.95–1.48) 2.03 (1.39–2.97) 1.48 (1.05–2.09) Not analyzeda 1.52 (1.19–1.96) 1.60 (1.28–2.01) Not analyzeda Not analyzeda | |

| E3N-EPIC: Fournier et al. (2014) | Estrogen alone | 1.17 (0.99–1.38) |

| Estrogen plus progesterone or dydrogesterone | 1.22 (1.11–1.35) | |

| Estrogen plus progestin | 1.87 (1.71–2.04) | |

| CECILE: Cordina-Duverger et al. (2013) | Estrogen alone | 1.19 (0.69–2.04) |

| Estrogen plus progestogen Progesterone Progestins Progesterone derivatives Testosterone derivatives |

1.33 (0.92–1.92) 0.80 (0.44–1.43) 1.72 (1.11–2.65) 1.57 (0.99–2.49) 3.35 (1.07–10.4) | |

| Footnotes: a = Not analyzed, fewer than 5 cases. Sources: See template. | ||

| Study | Therapy | Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| E3N-EPIC: Fournier et al. (2005)a | Transdermal estrogen plus progesterone <2 years 2–4 years ≥4 years |

0.9 (0.6–1.4) 0.7 (0.4–1.2) 1.2 (0.7–2.0) |

| Transdermal estrogen plus progestin <2 years 2–4 years ≥4 years |

1.6 (1.3–2.0) 1.4 (1.0–1.8) 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | |

| Oral estrogen plus progestin <2 years 2–4 years ≥4 years |

1.2 (0.9–1.8) 1.6 (1.1–2.3) 1.9 (1.2–3.2) | |

| E3N-EPIC: Fournier et al. (2008) | Estrogen plus progesterone <2 years 2–4 years 4–6 years ≥6 years |

0.71 (0.44–1.14) 0.95 (0.67–1.36) 1.26 (0.87–1.82) 1.22 (0.89–1.67) |

| Estrogen plus dydrogesterone <2 years 2–4 years 4–6 years ≥6 years |

0.84 (0.51–1.38) 1.16 (0.79–1.71) 1.28 (0.83–1.99) 1.32 (0.93–1.86) | |

| Estrogen plus other progestogens <2 years 2–4 years 4–6 years ≥6 years |

1.36 (1.07–1.72) 1.59 (1.30–1.94) 1.79 (1.44–2.23) 1.95 (1.62–2.35) | |

| E3N-EPIC: Fournier et al. (2014) | Estrogens plus progesterone or dydrogesterone <5 years ≥5 years |

1.13 (0.99–1.29) 1.31 (1.15–1.48) |

| Estrogen plus other progestogens <5 years ≥5 years |

1.70 (1.50–1.91) 2.02 (1.81–2.26) | |

| Footnotes: a = Oral estrogen plus progesterone was not analyzed because there was a low number of women who used this therapy. Sources: See template. | ||

Blood clots

[edit]Whereas the combination of estrogen and a progestin is associated with increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) relative to estrogen alone, there is no difference in risk of VTE with the combination of estrogen and oral progesterone relative to estrogen alone.[131][134] Hence, in contrast to progestins, oral progesterone added to estrogen does not appear to increase coagulation or VTE risk.[131][134] The reason for the differences between progesterone and progestins in terms of VTE risk are unclear.[135][131][130] However, they may be due to very low progesterone levels and relatively weak progestogenic effects produced by oral progesterone.[131][130] In contrast to oral progesterone, non-oral progesterone—which can achieve much higher progesterone levels—has not been assessed in terms of VTE risk.[131][130]

Overdose

[edit]Progesterone is likely to be relatively safe in overdose. Levels of progesterone during pregnancy are up to 100-fold higher than during normal menstrual cycling, although levels increase gradually over the course of pregnancy.[136] Oral dosages of progesterone of as high as 3,600 mg/day have been assessed in clinical trials, with the main side effect being sedation.[137] There is a case report of progesterone misuse with an oral dosage of 6,400 mg per day.[138] Administration of as much as 500 mg progesterone by intravenous infusion in humans was uneventful in terms of toxicity, but did induce deep sleep, though the individuals were still able to be awakened with sufficient stimulation.[120][17][121][122]

Interactions

[edit]There are several notable drug interactions with progesterone. Certain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline may increase the GABAA receptor-related central depressant effects of progesterone by enhancing its conversion into 5α-dihydroprogesterone and allopregnanolone via activation of 3α-HSD.[139] Progesterone potentiates the sedative effects of benzodiazepines and alcohol.[140] Notably, there is a case report of progesterone abuse alone with very high doses.[141] 5α-Reductase inhibitors such as finasteride and dutasteride inhibit the conversion of progesterone into the inhibitory neurosteroid allopregnanolone, and for this reason, may have the potential to reduce the sedative and related effects of progesterone.[142][143][144]

Progesterone is a weak but significant agonist of the pregnane X receptor (PXR), and has been found to induce several hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes, such as CYP3A4, especially when concentrations are high, such as with pregnancy range levels.[145][146][147][148] As such, progesterone may have the potential to accelerate the metabolism of various medications.[145][146][147][148]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]Progesterone is a progestogen, or an agonist of the nuclear progesterone receptors (PRs), the PR-A, PR-B, and PR-C.[20] In addition, progesterone is an agonist of the membrane progesterone receptors (mPRs), including the mPRα, mPRβ, mPRγ, mPRδ, and mPRϵ.[149][150] Aside from the PRs and mPRs, progesterone is a potent antimineralocorticoid, or antagonist of the mineralocorticoid receptor, the biological target of the mineralocorticoid aldosterone.[151][152] In addition to its activity as a steroid hormone, progesterone is a neurosteroid.[153] Among other neurosteroid activities, and via its active metabolites allopregnanolone and pregnanolone, progesterone is a potent positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor, the major signaling receptor of the inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA).[154]

The PRs are expressed widely throughout the body, including in the uterus, cervix, vagina, fallopian tubes, breasts, fat, skin, pituitary gland, hypothalamus, and in other areas of the brain.[20][155] In accordance, progesterone has numerous effects throughout the body.[20] Among other effects, progesterone produces changes in the female reproductive system, the breasts, and the brain.[20][155] Progesterone has functional antiestrogenic effects due to its progestogenic activity, including in the uterus, cervix, and vagina.[20] The effects of progesterone may influence health in both positive and negative ways.[20] In addition to the aforementioned effects, progesterone has antigonadotropic effects due to its progestogenic activity, and can inhibit ovulation and suppress gonadal sex hormone production.[20]

The activities of progesterone besides those mediated by the PRs and mPRs are also of significance.[20] Progesterone lowers blood pressure and reduces water and salt retention among other effects via its antimineralocorticoid activity.[20][156] In addition, progesterone can produce sedative, hypnotic, anxiolytic, euphoric, amnestic, cognitive-impairing, motor-impairing, anticonvulsant, and even anesthetic effects via formation of sufficiently high concentrations of its neurosteroid metabolites and consequent GABAA receptor potentiation in the brain.[28][113][114][157]

There are differences between progesterones and progestins, such as medroxyprogesterone acetate and norethisterone, with implications for pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics, as well as for efficacy, tolerability, and safety.[20]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]The pharmacokinetics of progesterone are dependent on its route of administration. The medications is approved in the form of oil-filled capsules containing micronized progesterone for oral administration, termed oral micronized progesterone or OMP.[158] It is also available in the form of vaginal or rectal suppositories or pessaries, topical creams and gels,[159] oil solutions for intramuscular injection, and aqueous solutions for subcutaneous injection.[158][16][160]

Routes of administration that progesterone has been used by include oral, intranasal, transdermal/topical, vaginal, rectal, intramuscular, subcutaneous, and intravenous injection.[16] Vaginal progesterone is available in the form of progesterone capsules, tablets or inserts, gels, suppositories or pessaries, and rings.[16]

The bioavailability of progesterone was commonly overestimated due to the immunoassay method of analysis failing to distinguish between progesterone itself and its metabolites.[161][130][131] Newer methods have adjusted the oral bioavailbility estimate from 6.2 to 8.6%[162] down to less than 2.4%.[5]

Chemistry

[edit]

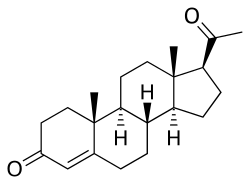

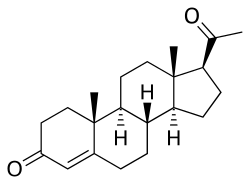

Progesterone is a naturally occurring pregnane steroid and is also known as pregn-4-ene-3,20-dione.[163][164] It has a double bond (4-ene) between the C4 and C5 positions and two ketone groups (3,20-dione), one at the C3 position and the other at the C20 position.[163][164] Due to its pregnane core and C4(5) double bond, progesterone is often abbreviated as P4. It is contrasted with pregnenolone, which has a C5(6) double bond and is often abbreviated as P5.

Derivatives

[edit]A large number of progestins, or synthetic progestogens, have been derived from progesterone.[163][20] They can be categorized into several structural groups, including derivatives of retroprogesterone, 17α-hydroxyprogesterone, 17α-methylprogesterone, and 19-norprogesterone, with a respective example from each group including dydrogesterone, medroxyprogesterone acetate, medrogestone, and promegestone.[20] The progesterone ethers quingestrone (progesterone 3-cyclopentyl enol ether) and progesterone 3-acetyl enol ether are among the only examples that do not belong to any of these groups.[155][165] Another major group of progestins, the 19-nortestosterone derivatives, exemplified by norethisterone (norethindrone) and levonorgestrel, are not derived from progesterone but rather from testosterone.[20]

A variety of synthetic inhibitory neurosteroids have been derived from progesterone and its neurosteroid metabolites, allopregnanolone and pregnanolone.[163] Examples include alfadolone, alfaxolone, ganaxolone, hydroxydione, minaxolone, and renanolone.[163] In addition, C3 and C20 conjugates of progesterone, such as progesterone carboxymethyloxime (progesterone 3-(O-carboxymethyl)oxime; P4-3-CMO), P1-185 (progesterone 3-O-(L-valine)-E-oxime), EIDD-1723 (progesterone 20E-[O-[(phosphonooxy)methyl]oxime] sodium salt), EIDD-036 (progesterone 20-oxime; P4-20-O), and VOLT-02 (chemical structure unreleased), have been developed as water-soluble prodrugs of progesterone and its neurosteroid metabolites.[166][167][168][169][170][171]

Synthesis

[edit]Chemical syntheses of progesterone have been published.[172]

History

[edit]Discovery and synthesis

[edit]The hormonal action of progesterone was discovered in 1929.[30][31][173] Pure crystalline progesterone was isolated in 1934 and its chemical structure was determined.[30][31] Later that year, chemical synthesis of progesterone was accomplished.[31][174] Shortly following its chemical synthesis, progesterone began being tested clinically in women.[31][103]

Injections and implants

[edit]In 1933 or 1934, Schering introduced progesterone in oil solution as a medication by intramuscular injection under the brand name Proluton.[175][32][33][22][176] This was the first pharmaceutical formulation of progesterone to be marketed for medical use.[177] It was initially a corpus luteum extract, becoming pure synthesized progesterone only subsequently.[178][179][175][180] A clinical study of the formulation was published in 1933.[175][181][179] Multiple formulations of progesterone in oil solution for intramuscular injection, under the brand names Proluton, Progestin, and Gestone, were available by 1936.[178][182] A parenteral route was used because oral progesterone had very low activity and was thought to be inactive.[22][176][180] Progesterone was initially very expensive due to the large doses required.[183] However, with the start of steroid manufacturing from diosgenin in the 1940s, costs greatly decreased.[184]

Subcutaneous pellet implants of progesterone were first studied in women in the late 1930s.[185][186][187][188][189] They were the first long-acting progestogen formulation.[190] Pellets were reported to be extruded out of the skin within a few weeks at high rates, even when implanted beneath the deep fascia, and also produced frequent inflammatory reactions at the site of implantation.[108][187][191] In addition, they were absorbed too slowly and achieved unsatisfactorily low progesterone levels.[108] Consequently, they were soon abandoned, in favor of other preparations such as aqueous suspensions.[108][191][192][190] However, subcutaneous pellet implants of progesterone were later studied as a form of birth control in women in the 1980s and early 1990s, though no preparations were ultimately marketed.[193][194][195][196]

Aqueous suspensions of progesterone crystals for intramuscular injection were first described in 1944.[190][197][198][199] These preparations were on the market in the 1950s under a variety of brand names including Flavolutan, Luteosan, Lutocyclin M, and Lutren, among others.[200] Aqueous suspensions of steroids were developed because they showed much longer durations than intramuscular injection of steroids in oil solution.[201] However, local injection site reactions, which do not occur with oil solutions, have limited the clinical use of aqueous suspensions of progesterone and other steroids.[202][203][204] Today, a preparation with the brand name Agolutin Depot remains on the market in the Czech Republic and Slovakia.[205][206] A combined preparation of progesterone, estradiol benzoate, and lidocaine remains available with the brand name Clinomin Forte in Paraguay as well.[207] In addition to aqueous suspensions, water-in-oil emulsions of steroids were studied by 1949,[208][209][210] and long-acting emulsions of progesterone were introduced for use by intramuscular injection under the brand names Progestin and Di-Pro-Emulsion (with estradiol benzoate) by the 1950s.[200][211][212][213][214] Due to lack of standardization of crystal sizes, crystalline suspensions of steroids had marked variations in effect.[108] Emulsions were said to be even more unreliable.[108]

Macrocrystalline aqueous suspensions of progesterone as well as microspheres of progesterone were investigated as potential progestogen-only injectable contraceptives and combined injectable contraceptives (with estradiol) by the late 1980s and early 1990s but were never marketed.[215][216][217][218][219]

Aqueous solutions of water-insoluble steroids were first developed via association with colloid solubility enhancers in the 1940s.[220] An aqueous solution of progesterone for use by intravenous injection was marketed by Schering AG under the brand name Primolut Intravenous by 1962.[221][109] One of its intended uses was the treatment of threatened abortion, in which rapid-acting effect was desirable.[108] An aqueous solution of progesterone complexed with cyclodextrin to increase its water solubility was introduced for use by once-daily subcutaneous injection in Europe under the brand name Prolutex in the mid-2010s.[222][16]

In the 1950s, long-acting parenteral progestins such as hydroxyprogesterone caproate, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and norethisterone enanthate were developed and introduced for use by intramuscular injection.[190][223][224] They lacked the need for frequent injections and the injection site reactions associated with progesterone by intramuscular injection and soon supplanted progesterone for parenteral therapy in most cases.[224][223][225]

Oral and sublingual

[edit]The first study of oral progesterone in humans was published in 1949.[226][227] It found that oral progesterone produced significant progestational effects in the endometrium in women.[226] Prior to this study, animal research had suggested that oral progesterone was inactive, and for this reason, oral progesterone had never been evaluated in humans.[226][227] A variety of other early studies of oral progesterone in humans were also published in the 1950s and 1960s.[227][228][229][230][231][232][233][234][235][236] These studies generally reported oral progesterone to be only very weakly active.[227][232][231] Oral non-micronized progesterone was introduced as a pharmaceutical medication around 1953, for instance as Cyclogesterin (1 mg estrogenic substances and 30 mg progesterone tablets) for menstrual disturbances by Upjohn, though it saw limited use.[237][238] Another preparation, which contained progesterone alone, was Synderone (trademark registered by Chemical Specialties in 1952).[239][240][241]

Sublingual progesterone in women was first studied in 1944 by Robert Greenblatt.[242][243][191][226][244][230] Buccal progesterone tablets were marketed by Schering under the brand name Proluton Buccal Tablets by 1949.[245] Sublingual progesterone tablets were marketed under the brand names Progesterone Lingusorbs and Progesterone Membrettes by 1951.[246][247][248] A sublingual tablet formulation of progesterone has been approved under the brand name Luteina in Poland and Ukraine and remains marketed today.[95][96]

Progesterone was the first progestogen that was found to inhibit ovulation, both in animals and in women.[249] Injections of progesterone were first shown to inhibit ovulation in animals between 1937 and 1939.[250][249][251][252] Inhibition of fertilization by administration of progesterone during the luteal phase was also demonstrated in animals between 1947 and 1949.[250] Ovulation inhibition by progesterone in animals was subsequently re-confirmed and expanded on by Gregory Pincus and colleagues in 1953 and 1954.[249][253][254] Findings on inhibition of ovulation by progesterone in women were first presented at the Fifth International Conference on Planned Parenthood in Tokyo, Japan in October 1955.[236][255] Three different research groups presented their findings on this topic at the conference.[236][255] They included Pincus (in conjunction with John Rock, who did not attend the conference); a nine-member Japanese group led by Masaomi Ishikawa; and the two-member team of Abraham Stone and Herbert Kupperman.[236][255][256][257][258] The conference marked the beginning of a new era in the history of birth control.[255] The results were subsequently published in scientific journals in 1956 in the case of Pincus and in 1957 in the case of Ishikawa and colleagues.[259][260][261] Rock and Pincus also subsequently described findings from 1952 that "pseudopregnancy" therapy with a combination of high doses of diethylstilbestrol and oral progesterone prevented ovulation and pregnancy in women.[233][262][263][264][265][266]

Unfortunately, the use of oral progesterone as a hormonal contraceptive was plagued by problems.[249][264] These included the large and by extension expensive doses required, incomplete inhibition of ovulation even at high doses, and a frequent incidence of breakthrough bleeding.[249][264] At the 1955 Tokyo conference, Pincus had also presented the first findings of ovulation inhibition by oral progestins in animals, specifically 19-nortestosterone derivatives like noretynodrel and norethisterone.[264][236] These progestins were far more potent than progesterone, requiring much smaller doses orally.[264][236] By December 1955, inhibition of ovulation by oral noretynodrel and norethisterone had been demonstrated in women.[264] These findings as well as results in animals were published in 1956.[267][268] Noretynodrel and norethisterone did not show the problems associated with oral progesterone—in the studies, they fully inhibited ovulation and did not produce menstruation-related side effects.[264] Consequently, oral progesterone was abandoned as a hormonal contraceptive in women.[249][264] The first birth control pills to be introduced were a noretynodrel-containing product in 1957 and a norethisterone-containing product in 1963, followed by numerous others containing a diversity of progestins.[269] Progesterone itself has never been introduced for use in birth control pills.[270]

More modern clinical studies of oral progesterone demonstrating elevated levels of progesterone and end-organ responses in women, specifically progestational endometrial changes, were published between 1980 and 1983.[271][272][273][274] Up to this point, many clinicians and researchers apparently still thought that oral progesterone was inactive.[274][275][276] It was not until almost half a century after the introduction of progesterone in medicine that a reasonably effective oral formulation of progesterone was marketed.[104] Micronization of progesterone and suspension in oil-filled capsules, which allowed progesterone to be absorbed several-fold more efficiently by the oral route, was first studied in the late 1970s and described in the literature in 1982.[277][273][278] This formulation, known as oral micronized progesterone (OMP), was then introduced for medical use under the brand name Utrogestan in France in 1982.[273][34][33][22] Subsequently, oral micronized progesterone was introduced under the brand name Prometrium in the United States in 1998.[162][279] By 1999, oral micronized progesterone had been marketed in more than 35 countries.[162] In 2019, the first combination of oral estradiol and progesterone was introduced under the brand name Bijuva in the United States.[11][280]

A sustained-release (SR) formulation of oral micronized progesterone, also known as "oral natural micronized progesterone sustained release" or "oral NMP SR", was marketed in India in 2012 under the brand name Gestofit SR.[281][110][282][95] Many additional brand names followed.[110][95] The preparation was originally developed in 1986 by a compounding pharmacy called Madison Pharmacy Associates in Madison, Wisconsin in the United States.[281][282]

Vaginal, rectal, and uterine

[edit]Vaginal progesterone suppositories were first studied in women by Robert Greenblatt in 1954.[283][191][284] Shortly thereafter, vaginal progesterone suppositories were introduced for medical use under the brand name Colprosterone in 1955.[285][191] Rectal progesterone suppositories were first studied in men and women by Christian Hamburger in 1965.[286][284] Vaginal and rectal progesterone suppositories were introduced for use under the brand name Cyclogest by 1976.[287][288][289] Vaginal micronized progesterone gels and capsules were introduced for medical use under brand names such as Utrogestan and Crinone in the early 1990s.[104][290] Progesterone was approved in the United States as a vaginal gel in 1997 and as a vaginal insert in 2007.[291][292] A progesterone contraceptive vaginal ring known as Progering was first studied in women in 1985 and continued to be researched through the 1990s.[293][294] It was approved for use as a contraceptive in lactating mothers in Latin America by 2004.[293] A second progesterone vaginal ring known as Fertiring was developed as a progesterone supplement for use during assisted reproduction and was approved in Latin America by 2007.[295][296]

Development of a progesterone-containing intrauterine device (IUD) for contraception began in the 1960s.[297] Incorporation of progesterone into IUDs was initially studied to help reduce the risk of IUD expulsion.[297] However, while addition of progesterone to IUDs showed no benefit on expulsion rates, it was unexpectedly found to induce endometrial atrophy.[297] This led in 1976 to the development and introduction of Progestasert, a progesterone-containing product and the first progestogen-containing IUD.[74][297][27] Unfortunately, the product had various problems that limited its use.[297][27][74] These included a short duration of efficacy of only one year, a high cost, a relatively high 2.9% failure rate, a lack of protection against ectopic pregnancy, and difficult and sometimes painful insertions that could necessitate use of a local anesthetic or analgesic.[297][27][74] As a result of these issues, Progestasert never became widely used, and was discontinued in 2001.[297][27][74] It was used mostly in the United States and France while it was marketed.[27]

Transdermal and topical

[edit]A topical gel formulation of progesterone, for direct application to the breasts as a local therapy for breast disorders such as breast pain, was introduced under the brand name Progestogel in Europe by 1972.[298] No transdermal formulations of progesterone for systemic use have been successfully marketed, in spite of efforts of pharmaceutical companies towards this goal.[45][22][299] The low potency of transdermal progesterone has thus far precluded it as a possibility.[300][301][302][124] Although no formulations of transdermal progesterone are approved for systemic use, transdermal progesterone is available in the form of creams and gels from custom compounding pharmacies in some countries, and is also available over-the-counter without a prescription in the United States.[45][46][99] However, these preparations are unregulated and have not been adequately characterized, with low and unsubstantiated effectiveness.[45][22]

Society and culture

[edit]Generic names

[edit]Progesterone is the generic name of the drug in English and its INN, USAN, USP, BAN, DCIT, and JAN, while progestérone is its name in French and its DCF.[95][163][164][303] It is also referred to as progesteronum in Latin, progesterona in Spanish and Portuguese, and progesteron in German.[95][164]

Brand names

[edit]

Progesterone is marketed under a large number of brand names throughout the world.[95][164] Examples of major brand names under which progesterone has been marketed include Crinone, Crinone 8%, Cyclogest, Endogest, Endometrin, Estima, Geslutin, Gesterol, Gestone, Luteina, Luteinol, Lutigest, Lutinus, Microgest, Progeffik, Progelan, Progendo, Progering, Progest, Progestaject, Progestan, Progesterone, Progestin, Progestogel, Prolutex, Proluton, Prometrium, Prontogest, Strone, Susten, Utrogest, and Utrogestan.[95][164]

Availability

[edit]Progesterone is widely available in countries throughout the world in a variety of formulations.[95][96] Progesterone in the form of oral capsules; vaginal capsules, tablets/inserts, and gels; and intramuscular oil have widespread availability.[95][96] The following formulations/routes of progesterone have selective or more limited availability:[95][96]

- A tablet of micronized progesterone which is marketed under the brand name Luteina is indicated for sublingual administration in addition to vaginal administration and is available in Poland and Ukraine.[95][96]

- A progesterone suppository which is marketed under the brand name Cyclogest is indicated for rectal administration in addition to vaginal administration and is available in Cyprus, Hong Kong, India, Malaysia, Malta, Oman, Singapore, South Africa, Thailand, Tunisia, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and Vietnam.[95][96]

- An aqueous solution of progesterone complexed with β-cyclodextrin for subcutaneous injection is marketed under the brand name Prolutex in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, and Switzerland.[95][96]

- A non-systemic topical gel formulation of progesterone for local application to the breasts to treat breast pain is marketed under the brand name Progestogel and is available in Belgium, Bulgaria, Colombia, Ecuador, France, Georgia, Germany, Hong Kong, Lebanon, Peru, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Switzerland, Tunisia, Venezuela, and Vietnam.[95][96] It was also formerly available in Italy, Portugal, and Spain, but was discontinued in these countries.[96]

- A progesterone intrauterine device was previously marketed under the brand name Progestasert and was available in Canada, France, the United States, and possibly other countries, but was discontinued.[96][304]

- Progesterone vaginal rings are marketed under the brand names Fertiring and Progering and are available in Chile, Ecuador, and Peru.[95][96]

- A sustained-release tablet formulation of oral micronized progesterone (also known as "oral natural micronized progesterone sustained release" or "oral NMP SR") is marketed in India under the brand names Lutefix Pro (CROSMAT Technology), Dubagest SR, Gestofit SR, and Susten SR, among many others.[281][305][306][307][308][309][310][282][95]

In addition to single-drug formulations, the following progesterone combination formulations are or have been marketed, albeit with limited availability:[95][96]

- A combination pack of progesterone capsules for oral use and estradiol gel for transdermal use is marketed under the brand name Estrogel Propak in Canada.[95][96]

- A combination pack of progesterone capsules and estradiol tablets for oral use is marketed in an under the brand name Duogestan in Belgium.[95][96]

- Progesterone and estradiol in an aqueous suspension for use by intramuscular injection is marketed under the brand name Cristerona FP in Argentina.[95][96]

- Progesterone and estradiol in microspheres in an oil solution for use by intramuscular injection is marketed under the brand name Juvenum in Mexico.[95][96][311]

- Progesterone and estradiol benzoate in an oil solution for use by intramuscular injection is marketed under the brand names Duogynon, Duoton Fort T P, Emmenovis, Gestrygen, Lutofolone, Menovis, Mestrolar, Metrigen Fuerte, Nomestrol, Phenokinon-F, Prodiol, Pro-Estramon-S, Proger F, Progestediol, and Vermagest and is available in Belize, Egypt, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Honduras, Italy, Lebanon, Malaysia, Mexico, Nicaragua, Taiwan, Thailand, and Turkey.[95][96]

- Progesterone and estradiol hemisuccinate in an oil solution for use by intramuscular injection is marketed under the brand name Hosterona in Argentina.[95][96]

- Progesterone and estrone for use by intramuscular injection is marketed under the brand name Synergon in Monaco.[95]

United States

[edit]As of November 2016[update], progesterone is available in the United States in the following formulations:[94]

- Oral: Capsules: Prometrium (100 mg, 200 mg, 300 mg)

- Vaginal: Tablets: Endometrin (100 mg); Gels: Crinone (4%, 8%)

- Intramuscular injection: Oil: Progesterone (50 mg/mL)

A 25 mg/mL concentration of progesterone oil for intramuscular injection and a 38 mg/device progesterone intrauterine device (Progestasert) have been discontinued.[94]

An oral combination formulation of micronized progesterone and estradiol in oil-filled capsules (brand name Bijuva) is marketed in the United States for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and endometrial hyperplasia.[312][11]

Progesterone is also available in unregulated custom preparations from compounding pharmacies in the United States.[97][98] In addition, transdermal progesterone is available over-the-counter in the United States, although the clinical efficacy of transdermal progesterone is controversial.[45][46][99]

Research

[edit]Progesterone was studied as a progestogen-only injectable contraceptive, but was never marketed.[215][216][217] Combinations of estradiol and progesterone as a macrocrystalline aqueous suspension and as an aqueous suspension of microspheres have been studied as once-a-month combined injectable contraceptives, but were likewise never marketed.[216][218]

Progesterone has been assessed for the suppression of sex drive and spermatogenesis in men.[313][314] In one study, 100 mg rectal suppositories of progesterone given five times per day for 9 days resulted in progesterone levels of 5.5 to 29 ng/mL and suppressed circulating testosterone and growth hormone levels by about 50% in men, but did not affect libido or erectile potency in this short treatment period.[313][315] In other studies, 50 mg/day progesterone by intramuscular injection for 10 weeks in men produced azoospermia, decreased testicular size, markedly suppressed libido and erectile potency, and resulted in minimal semen volume upon ejaculation.[313][314][316][317]

An oil and water nanoemulsion of progesterone (particles of <1 mm in diameter) using micellar nanoparticle technology for transdermal administration known as Progestsorb NE was under development by Novavax for use in menopausal hormone therapy in the 2000s.[318][319][320] However, development was discontinued in 2007 and the formulation was never marketed.[318]

References

[edit]- ^ Adler N, Pfaff D, Goy RW (6 December 2012). Handbook of Behavioral Neurobiology Volume 7 Reproduction (1st ed.). New York: Plenum Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-1-4684-4834-4. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ "Regulatory Decision Summary for pms-Progesterone". Drug and Health Product Register. 23 October 2014.

- ^ "Reproductive health". Health Canada. 9 May 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ "Health product highlights 2021: Annexes of products approved in 2021". Health Canada. 3 August 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ a b Levine H, Watson N (March 2000). "Comparison of the pharmacokinetics of crinone 8% administered vaginally versus Prometrium administered orally in postmenopausal women(3)". Fertility and Sterility. 73 (3): 516–521. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(99)00553-1. PMID 10689005.

- ^ Griesinger G, Tournaye H, Macklon N, Petraglia F, Arck P, Blockeel C, et al. (February 2019). "Dydrogesterone: pharmacological profile and mechanism of action as luteal phase support in assisted reproduction". Reproductive Biomedicine Online. 38 (2): 249–259. doi:10.1016/j.rbmo.2018.11.017. PMID 30595525.

- ^ Pandya MR, Gopeenathan P, Gopinath PM, Das SK, Sauhta M, Shinde V (2016). "Evaluating the clinical efficacy and safety of progestogens in the management of threatened and recurrent miscarriage in early pregnancy-A review of the literature". Indian Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology Research. 3 (2): 157. doi:10.5958/2394-2754.2016.00043.6. ISSN 2394-2746. S2CID 36586762.

- ^ Paulson RJ, Collins MG, Yankov VI (November 2014). "Progesterone pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics with 3 dosages and 2 regimens of an effervescent micronized progesterone vaginal insert". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 99 (11): 4241–4249. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-3937. PMID 24606090.

- ^ Fritz MA, Speroff L (28 March 2012). Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 44–. ISBN 978-1-4511-4847-3.

- ^ Marshall WJ, Bangert SK (2008). Clinical Chemistry. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 192–. ISBN 978-0-7234-3455-9.

- ^ a b c Pickar JH, Bon C, Amadio JM, Mirkin S, Bernick B (December 2015). "Pharmacokinetics of the first combination 17β-estradiol/progesterone capsule in clinical development for menopausal hormone therapy". Menopause. 22 (12): 1308–1316. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000467. PMC 4666011. PMID 25944519.

- ^ a b Khomyak NV, Mamchur VI, Khomyak EV (2014). "Клинико-фармакологические особенности современных лекарственных форм микронизированного прогестерона, применяющихся во время беременности" [Clinical and pharmacological features of modern dosage forms of micronized progesterone used during pregnancy.] (PDF). Доровье [Health]. 4: 90.

- ^ a b "Crinone® 4% and Crinone® 8% (progesterone gel)" (PDF). Watson Pharma, Inc. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. August 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 December 2016.

- ^ Mircioiu C, Perju A, Griu E, Calin G, Neagu A, Enachescu D, et al. (1998). "Pharmacokinetics of progesterone in postmenopausal women: 2. Pharmacokinetics following percutaneous administration". European Journal of Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics. 23 (3): 397–402. doi:10.1007/BF03192300. PMID 9842983. S2CID 32772029.

- ^ Simon JA, Robinson DE, Andrews MC, Hildebrand JR, Rocci ML, Blake RE, et al. (July 1993). "The absorption of oral micronized progesterone: the effect of food, dose proportionality, and comparison with intramuscular progesterone". Fertility and Sterility. 60 (1): 26–33. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(16)56031-2. PMID 8513955.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cometti B (November 2015). "Pharmaceutical and clinical development of a novel progesterone formulation". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 94 (Suppl 161): 28–37. doi:10.1111/aogs.12765. PMID 26342177. S2CID 31974637.

The administration of progesterone in injectable or vaginal form is more efficient than by the oral route, since it avoids the metabolic losses of progesterone encountered with oral administration resulting from the hepatic first-pass effect (32). In addition, the injectable forms avoid the need for higher doses that cause a fairly large number of side-effects, such as somnolence, sedation, anxiety, irritability and depression (33).

- ^ a b c Aufrère MB, Benson H (June 1976). "Progesterone: an overview and recent advances". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 65 (6): 783–800. doi:10.1002/jps.2600650602. PMID 945344.

- ^ "Prometrium (progesterone, USP) Capsules 100 mg" (PDF). Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 1998.

- ^ "Progesterone Injection USP in Sesame Oil for Intramuscular Use Only Rx Only" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. January 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am Kuhl H (August 2005). "Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration". Climacteric. 8 (Suppl 1): 3–63. doi:10.1080/13697130500148875. PMID 16112947. S2CID 24616324.

- ^ a b c d e Wesp LM, Deutsch MB (March 2017). "Hormonal and Surgical Treatment Options for Transgender Women and Transfeminine Spectrum Persons". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 40 (1): 99–111. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2016.10.006. PMID 28159148.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ruan X, Mueck AO (November 2014). "Systemic progesterone therapy--oral, vaginal, injections and even transdermal?". Maturitas. 79 (3): 248–255. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.07.009. PMID 25113944.

- ^ Filicori M (November 2015). "Clinical roles and applications of progesterone in reproductive medicine: an overview". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 94 (Suppl 161): 3–7. doi:10.1111/aogs.12791. PMID 26443945.

- ^ a b Ciampaglia W, Cognigni GE (November 2015). "Clinical use of progesterone in infertility and assisted reproduction". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 94 (Suppl 161): 17–27. doi:10.1111/aogs.12770. PMID 26345161. S2CID 40753277.

- ^ Choi SJ (September 2017). "Use of progesterone supplement therapy for prevention of preterm birth: review of literatures". Obstetrics & Gynecology Science. 60 (5): 405–420. doi:10.5468/ogs.2017.60.5.405. PMC 5621069. PMID 28989916.

- ^ a b Whitaker A, Gilliam M (2014). Contraception for Adolescent and Young Adult Women. Springer. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-4614-6579-9.

- ^ a b c d e f Chaudhuri (2007). Practice of Fertility Control: A Comprehensive Manual (7Th ed.). Elsevier India. pp. 153–. ISBN 978-81-312-1150-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Goletiani NV, Keith DR, Gorsky SJ (October 2007). "Progesterone: review of safety for clinical studies". Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 15 (5): 427–444. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.15.5.427. PMID 17924777.

- ^ a b c d e f Stute P, Neulen J, Wildt L (August 2016). "The impact of micronized progesterone on the endometrium: a systematic review" (PDF). Climacteric. 19 (4): 316–328. doi:10.1080/13697137.2016.1187123. PMID 27277331.

- ^ a b c Josimovich JB (11 November 2013). Gynecologic Endocrinology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 9, 25–29, 139. ISBN 978-1-4613-2157-6.

- ^ a b c d e Coutinho EM, Segal SJ (1999). Is Menstruation Obsolete?. Oxford University Press. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-0-19-513021-8.

- ^ a b Seaman B (4 January 2011). The Greatest Experiment Ever Performed on Women: Exploding the Estrogen Myth. Seven Stories Press. pp. 27–. ISBN 978-1-60980-062-8.

- ^ a b c d Simon JA (December 1995). "Micronized progesterone: vaginal and oral uses". Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 38 (4): 902–914. doi:10.1097/00003081-199538040-00024. PMID 8616985.

- ^ a b Csech J, Gervais C (September 1982). "[Utrogestan]" [Utrogestan]. Soins. Gynécologie, Obstétrique, Puériculture, Pédiatrie (in French) (16): 45–46. PMID 6925387.

- ^ "Top 300 of 2023". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 August 2025. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ "Progesterone Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2023". ClinCalc. Retrieved 18 August 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g Archer DF, Bernick BA, Mirkin S (August 2019). "A combined, bioidentical, oral, 17β-estradiol and progesterone capsule for the treatment of moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms due to menopause". Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology. 12 (8): 729–739. doi:10.1080/17512433.2019.1637731. PMID 31282768.

- ^ a b c d e f g Eden J (February 2017). "The endometrial and breast safety of menopausal hormone therapy containing micronised progesterone: A short review". The Australian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 57 (1): 12–15. doi:10.1111/ajo.12583. PMID 28251642. S2CID 206990125.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Mirkin S (August 2018). "Evidence on the use of progesterone in menopausal hormone therapy". Climacteric. 21 (4): 346–354. doi:10.1080/13697137.2018.1455657. PMID 29630427.

- ^ Mueck AO, Ruan X (December 2019). "Will estradiol/progesterone capsules for oral use become the best choice for menopausal hormone therapy?". Climacteric. 22 (6): 535–537. doi:10.1080/13697137.2019.1663625. PMID 31612748.

- ^ Lobo RA, Liu J, Stanczyk FZ, Constantine GD, Pickar JH, Shadiack AM, et al. (July 2019). "Estradiol and progesterone bioavailability for moderate to severe vasomotor symptom treatment and endometrial protection with the continuous-combined regimen of TX-001HR (oral estradiol and progesterone capsules)". Menopause. 26 (7): 720–727. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001306. PMC 6636803. PMID 30694918.

- ^ a b Gompel A (August 2018). "Progesterone, progestins and the endometrium in perimenopause and in menopausal hormone therapy". Climacteric. 21 (4): 321–325. doi:10.1080/13697137.2018.1446932. PMID 29583028. S2CID 4422872.

- ^ Warren MP (August 2018). "Vaginal progesterone and the vaginal first-pass effect". Climacteric. 21 (4): 355–357. doi:10.1080/13697137.2018.1450856. PMID 29583019. S2CID 4419927.

- ^ Gompel A (April 2012). "Micronized progesterone and its impact on the endometrium and breast vs. progestogens". Climacteric. 15 (Suppl 1): 18–25. doi:10.3109/13697137.2012.669584. PMID 22432812. S2CID 17700754.

- ^ a b c d e f g Stanczyk FZ (December 2014). "Treatment of postmenopausal women with topical progesterone creams and gels: are they effective?". Climacteric. 17 (Suppl 2): 8–11. doi:10.3109/13697137.2014.944496. PMID 25196424. S2CID 20019151.

- ^ a b c d e Stanczyk FZ, Paulson RJ, Roy S (March 2005). "Percutaneous administration of progesterone: blood levels and endometrial protection". Menopause. 12 (2): 232–237. doi:10.1097/00042192-200512020-00019. PMID 15772572. S2CID 10982395.

- ^ a b c Prior JC (August 2018). "Progesterone for treatment of symptomatic menopausal women". Climacteric. 21 (4): 358–365. doi:10.1080/13697137.2018.1472567. PMID 29962247.

- ^ Schumacher M, Guennoun R, Ghoumari A, Massaad C, Robert F, El-Etr M, et al. (June 2007). "Novel perspectives for progesterone in hormone replacement therapy, with special reference to the nervous system". Endocrine Reviews. 28 (4): 387–439. doi:10.1210/er.2006-0050. PMID 17431228.

- ^ Brinton RD, Thompson RF, Foy MR, Baudry M, Wang J, Finch CE, et al. (May 2008). "Progesterone receptors: form and function in brain". Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 29 (2): 313–339. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.02.001. PMC 2398769. PMID 18374402.

- ^ Worsley R, Santoro N, Miller KK, Parish SJ, Davis SR (March 2016). "Hormones and Female Sexual Dysfunction: Beyond Estrogens and Androgens--Findings from the Fourth International Consultation on Sexual Medicine". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 13 (3): 283–290. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2015.12.014. PMID 26944460.

- ^ Prior JC (August 2018). "Progesterone for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in women". Climacteric. 21 (4): 366–374. doi:10.1080/13697137.2018.1467400. PMID 29962257.

- ^ Raine-Fenning NJ, Brincat MP, Muscat-Baron Y (2003). "Skin aging and menopause: implications for treatment". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 4 (6): 371–378. doi:10.2165/00128071-200304060-00001. PMID 12762829. S2CID 20392538.

- ^ Holzer G, Riegler E, Hönigsmann H, Farokhnia S, Schmidt JB (September 2005). "Effects and side-effects of 2% progesterone cream on the skin of peri- and postmenopausal women: results from a double-blind, vehicle-controlled, randomized study". The British Journal of Dermatology. 153 (3): 626–634. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06685.x. PMID 16120154. S2CID 6077829.

- ^ Mirkin S, Amadio JM, Bernick BA, Pickar JH, Archer DF (May 2015). "17β-Estradiol and natural progesterone for menopausal hormone therapy: REPLENISH phase 3 study design of a combination capsule and evidence review". Maturitas. 81 (1): 28–35. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.02.266. PMID 25835751.

- ^ a b c d e World Professional Association for Transgender Health (September 2011), Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People, Seventh Version (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2016

- ^ Cundill, P (July 2020). "Hormone therapy for trans and gender diverse patients in the general practice setting". Australian Journal of General Practice. 49 (7): 385–390. doi:10.31128/AJGP-01-20-5197. PMID 32599993.

- ^ a b c Ettner R, Monstrey S, Coleman E (20 May 2016). Principles of Transgender Medicine and Surgery. Routledge. pp. 170–. ISBN 978-1-317-51460-2.

- ^ a b c Wierckx K, Gooren L, T'Sjoen G (May 2014). "Clinical review: Breast development in trans women receiving cross-sex hormones". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 11 (5): 1240–1247. doi:10.1111/jsm.12487. PMID 24618412.

- ^ White CP, Hitchcock CL, Vigna YM, Prior JC (2011). "Fluid Retention over the Menstrual Cycle: 1-Year Data from the Prospective Ovulation Cohort". Obstetrics and Gynecology International. 2011 138451. doi:10.1155/2011/138451. PMC 3154522. PMID 21845193.

- ^ Copstead-Kirkhorn EC, Banasik JL (25 June 2014). Pathophysiology - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 660–. ISBN 978-0-323-29317-4.

Throughout the reproductive years, some women note swelling of the breast around the latter part of each menstrual cycle before the onset of menstruation. The water retention and subsequent swelling of breast tissue during this phase of the menstrual cycle are thought to be due to high levels of circulating progesterone stimulating the secretory cells of the breast.

- ^ Farage MA, Neill S, MacLean AB (January 2009). "Physiological changes associated with the menstrual cycle: a review". Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 64 (1): 58–72. doi:10.1097/OGX.0b013e3181932a37. PMID 19099613. S2CID 22293838.

- ^ da Fonseca EB, Bittar RE, Carvalho MH, Zugaib M (February 2003). "Prophylactic administration of progesterone by vaginal suppository to reduce the incidence of spontaneous preterm birth in women at increased risk: a randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 188 (2): 419–424. doi:10.1067/mob.2003.41. PMID 12592250. S2CID 14904733.

- ^ Harris G (2 May 2011). "Hormone Is Said to Cut Risk of Premature Birth". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ O'Brien JM, Adair CD, Lewis DF, Hall DR, Defranco EA, Fusey S, et al. (October 2007). "Progesterone vaginal gel for the reduction of recurrent preterm birth: primary results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 30 (5): 687–696. doi:10.1002/uog.5158. PMID 17899572. S2CID 31181784.

- ^ DeFranco EA, O'Brien JM, Adair CD, Lewis DF, Hall DR, Fusey S, et al. (October 2007). "Vaginal progesterone is associated with a decrease in risk for early preterm birth and improved neonatal outcome in women with a short cervix: a secondary analysis from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 30 (5): 697–705. doi:10.1002/uog.5159. PMID 17899571. S2CID 15577369.

- ^ Fonseca EB, Celik E, Parra M, Singh M, Nicolaides KH (August 2007). "Progesterone and the risk of preterm birth among women with a short cervix". The New England Journal of Medicine. 357 (5): 462–469. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa067815. PMID 17671254. S2CID 14884358.

- ^ Romero R (October 2007). "Prevention of spontaneous preterm birth: the role of sonographic cervical length in identifying patients who may benefit from progesterone treatment". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 30 (5): 675–686. doi:10.1002/uog.5174. PMID 17899585. S2CID 46366053.