Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Soft drink

View on Wikipedia

A soft drink (see § Terminology for other names) is a class of drink containing no alcohol, usually (but not necessarily) carbonated, and typically including added sweetener. Flavors can be natural, artificial or a mixture of the two. The sweetener may be a sugar, high-fructose corn syrup, fruit juice, a sugar substitute (in the case of diet sodas), or some combination of these. Soft drinks may also contain caffeine, colorings, preservatives and other ingredients. Coffee, tea, milk, cocoa, and unaltered fruit and vegetable juices are not considered soft drinks.[1]

Soft drinks are called "soft" in contrast with "hard" alcoholic drinks and their counterparts: non-alcoholic drinks. Small amounts of alcohol may be present in a soft drink, but the alcohol content must be less than 0.5% of the total volume of the drink (ABV) in many countries and localities[2][3] if the drink is to not be considered alcoholic.[4] Examples of soft drinks include lemon-lime drinks, orange soda, cola, grape soda, cream soda, ginger ale and root beer.

Soft drinks may be served cold, over ice cubes, or at room temperature. They are available in many container formats, including cans, glass bottles, and plastic bottles. Containers come in a variety of sizes, ranging from small bottles to large multi-liter containers. Soft drinks are widely available at fast food restaurants, movie theaters, convenience stores, casual-dining restaurants, dedicated soda stores, vending machines and bars from soda fountain machines.

Within a decade of the invention of carbonated water by Joseph Priestley in 1767, inventors in Europe had used his concept to produce the drink in greater quantities. One such inventor, J. J. Schweppe, formed Schweppes in 1783 and began selling the world's first bottled soft drink.[5][6] Soft drink brands founded in the 19th century include R. White's Lemonade in 1845, Moxie in 1876, Dr Pepper in 1885 and Coca-Cola in 1886. Subsequent brands include Pepsi, Irn-Bru, Sprite, Fanta, 7 Up and RC Cola.

Terminology

[edit]The term "soft drink" is a category in the beverage industry, and is broadly used in product labeling and on restaurant menus, generally a euphemistic term meaning non-alcoholic. However, in many countries such drinks are more commonly referred to by regional names, including pop, cool drink, fizzy drink, cola, soda, or soda pop.[7][8] Other less-used terms include carbonated drink, fizzy juice, lolly water, seltzer, coke, tonic, and mineral.[9] Due to the high sugar content in typical soft drinks, they may also be called sugary drinks.[10]

In the United States, the 2003 Harvard Dialect Survey[7] tracked the usage of the nine most common names. Over half of the survey respondents preferred the term "soda", which was dominant in the Northeastern United States, California, and the areas surrounding Milwaukee and St. Louis. The term "pop", which was preferred by 25% of the respondents, was most popular in the Midwest and Pacific Northwest, while the genericized trademark "coke", used by 12% of the respondents, was most popular in the Southern United States.[7] The term "tonic" is distinctive to eastern Massachusetts, although its use is declining.[11]

In the English-speaking parts of Canada, the term "pop" is prevalent, but "soft drink" is the most common English term used in Montreal.[12]

In the United Kingdom and Ireland, the term "fizzy drink" is common. "Pop" and "fizzy pop" are used in Northern England, South Wales, and the Midlands[13] while "mineral"[8] is used in Ireland. In Scotland, "fizzy juice" or even simply "juice" is colloquially encountered, as is "ginger".[14] In Australia and New Zealand, "soft drink"[15] or "fizzy drink" is typically used.[16] In South African English, "cool drink" is any soft drink.[17]

In other languages, various names are used: descriptive names as "non-alcoholic beverages", equivalents of "soda water", or generalized names. For example, the Bohemian variant of the Czech language (but not Moravian dialects) uses "limonáda" for all such beverages, not only those made from lemons.[18] Similarly, the Slovak language uses "malinovka" ("raspberry water") for all such beverages, not only for raspberry ones.[19]

History

[edit]The origins of soft drinks lie in the development of fruit-flavored drinks. In the medieval Middle East, a variety of fruit-flavored soft drinks were widely drunk, such as sharbat, and were often sweetened with ingredients such as sugar, syrup and honey. Other common ingredients included lemon, apple, pomegranate, tamarind, jujube, sumac, musk, mint and ice. Middle Eastern drinks later became popular in medieval Europe, where the word "syrup" was derived from Arabic.[20] In Tudor England, 'water imperial' was widely drunk; it was a sweetened drink with lemon flavor and containing cream of tartar. 'Manays Cryste' was a sweetened cordial flavored with rosewater, violets or cinnamon.[21]

Another early type of soft drink was lemonade, made of water and lemon juice sweetened with honey, but without carbonated water. The Compagnie des Limonadiers of Paris was granted a monopoly for the sale of lemonade soft drinks in 1676. Vendors carried tanks of lemonade on their backs and dispensed cups of the soft drink to Parisians.[19]

Carbonated drinks

[edit]

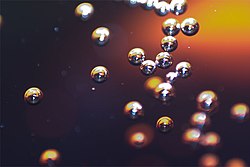

Carbonated drinks or fizzy drinks are beverages that consist mainly of carbonated water. The dissolution of carbon dioxide (CO2) in a liquid, gives rise to effervescence or fizz. Carbon dioxide is only weakly soluble in water; therefore, it separates into a gas when the pressure is released. The process usually involves injecting carbon dioxide under high pressure. When the pressure is removed, the carbon dioxide is released from the solution as small bubbles, which causes the solution to become effervescent, or fizzy.

Carbonated beverages are prepared by mixing flavored syrup with carbonated water. Carbonation levels range up to 5 volumes of CO2 per liquid volume. Ginger ale, colas, and related drinks are carbonated with 3.5 volumes. Other drinks, often fruity ones, are carbonated less.[22]

In the late 18th century, scientists made important progress in replicating naturally carbonated mineral waters. In 1767, Englishman Joseph Priestley first discovered a method of infusing water with carbon dioxide to make carbonated water[23] when he suspended a bowl of distilled water above a beer vat at a local brewery in Leeds, England. His invention of carbonated water (later known as soda water, for the use of soda powders in its commercial manufacture) is the major and defining component of most soft drinks.[24]

Priestley found that water treated in this manner had a pleasant taste, and he offered it to his friends as a refreshing drink. In 1772, Priestley published a paper entitled Impregnating Water with Fixed Air in which he describes dripping oil of vitriol (or sulfuric acid as it is now called) onto chalk to produce carbon dioxide gas and encouraging the gas to dissolve into an agitated bowl of water.[24]

"Within a decade, inventors in Britain and in Europe had taken Priestley's basic idea—get some "fixed air," mix it with water, shake—and created contraptions that could make carbonated water more quickly, in greater quantities. One of those inventors was named Johann Jacob Schweppe, who sold bottled soda water and whose business is still around today."

Another Englishman, John Mervin Nooth, improved Priestley's design and sold his apparatus for commercial use in pharmacies. Swedish chemist Torbern Bergman invented a generating apparatus that made carbonated water from chalk by the use of sulfuric acid. Bergman's apparatus allowed imitation mineral water to be produced in large amounts. Thomas Henry, an apothecary from Manchester, was the first to sell artificial mineral water to the general public for medicinal purposes, beginning in the 1770s. His recipe for 'Bewley's Mephitic Julep' consisted of 3 drachms of fossil alkali to a quart of water, and the manufacture had to 'throw in streams of fixed air until all the alkaline taste is destroyed'.[21]

Johann Jacob Schweppe developed a process to manufacture bottled carbonated mineral water.[6] He founded the Schweppes Company in Geneva in 1783 to sell carbonated water,[25] and relocated his business to London in 1792. His drink soon gained in popularity; among his newfound patrons was Erasmus Darwin. In 1843, the Schweppes company commercialized Malvern Water at the Holywell Spring in the Malvern Hills, and received a royal warrant from King William IV.[26]

It was not long before flavoring was combined with carbonated water. The earliest reference to carbonated ginger beer is in a Practical Treatise on Brewing. published in 1809. The drinking of either natural or artificial mineral water was considered at the time to be a healthy practice, and was promoted by advocates of temperance. Pharmacists selling mineral waters began to add herbs and chemicals to unflavored mineral water. They used birch bark (see birch beer), dandelion, sarsaparilla root, fruit extracts, and other substances.

Phosphate soda

[edit]A variant of soda in the United States called "phosphate soda" appeared in the late 1870s. It became one of the most popular soda fountain drinks from 1900 until the 1930s, with the lemon or orange phosphate being the most basic. The drink consists of 1 US fl oz (30 ml) fruit syrup, 1/2 teaspoon of phosphoric acid, and enough carbonated water and ice to fill a glass. This drink was commonly served in pharmacies.[27]

Mass market and industrialization

[edit]

Soft drinks soon outgrew their origins in the medical world and became a widely consumed product, available cheaply for the masses. By the 1840s, there were more than fifty soft drink manufacturers in London, an increase from just ten in the 1820s.[28] Carbonated lemonade was widely available in British refreshment stalls in 1833,[28] and in 1845, R. White's Lemonade went on sale in the UK.[29] For the Great Exhibition of 1851 held at Hyde Park in London, Schweppes was designated the official drink supplier and sold over a million bottles of lemonade, ginger beer, Seltzer water and soda-water.[28] There was a Schweppes soda water fountain, situated directly at the entrance to the exhibition.[21]

Mixer drinks became popular in the second half of the century. Tonic water was originally quinine added to water as a prophylactic against malaria and was consumed by British officials stationed in the tropical areas of South Asia and Africa. As the quinine powder was so bitter people began mixing the powder with soda and sugar, and a basic tonic water was created. The first commercial tonic water was produced in 1858.[30] The mixed drink gin and tonic also originated in British colonial India, when the British population would mix their medicinal quinine tonic with gin.[21]

A persistent problem in the soft drinks industry was the lack of an effective sealing of the bottles. Carbonated drink bottles are under great pressure from the gas, so inventors tried to find the best way to prevent the carbon dioxide or bubbles from escaping. The bottles could also explode if the pressure was too great. Hiram Codd devised a patented bottling machine while working at a small mineral water works in the Caledonian Road, Islington, in London in 1870. His Codd-neck bottle was designed to enclose a marble and a rubber washer in the neck. The bottles were filled upside down, and pressure of the gas in the bottle forced the marble against the washer, sealing in the carbonation. The bottle was pinched into a special shape to provide a chamber into which the marble was pushed to open the bottle. This prevented the marble from blocking the neck as the drink was poured.[21] R. White's, by now the biggest soft drinks company in London and south-east England, featured a wide range of drinks on their price list in 1887, all of which were sold in Codd's glass bottles, with choices including strawberry soda, raspberry soda, cherryade and cream soda.[31]

In 1892, the "Crown Cork Bottle Seal" was patented by William Painter, a Baltimore, Maryland machine shop operator. It was the first bottle top to successfully keep the bubbles in the bottle. In 1899, the first patent was issued for a glass-blowing machine for the automatic production of glass bottles. Earlier glass bottles had all been hand-blown. Four years later, the new bottle-blowing machine was in operation. It was first operated by Michael Owens, an employee of Libby Glass Company. Within a few years, glass bottle production increased from 1,400 bottles a day to about 58,000 bottles a day.

In America, soda fountains were initially more popular, and many Americans would frequent the soda fountain daily. Beginning in 1806, Yale University chemistry professor Benjamin Silliman sold soda waters in New Haven, Connecticut. He used a Nooth apparatus to produce his waters. Businessmen in Philadelphia and New York City also began selling soda water in the early 19th century. In the 1830s, John Matthews of New York City and John Lippincott of Philadelphia began manufacturing soda fountains. Both men were successful and built large factories for fabricating fountains. Due to problems in the U.S. glass industry, bottled drinks remained a small portion of the market throughout much of the 19th century. (However, they were known in England. In The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, published in 1848, the caddish Huntingdon, recovering from months of debauchery, wakes at noon and gulps a bottle of soda-water.[32])

In the early 20th century, sales of bottled soda increased greatly around the world, and in the second half of the 20th century, canned soft drinks became an important share of the market. During the 1920s, "Home-Paks" were invented. "Home-Paks" are the familiar six-pack cartons made from cardboard. Vending machines also began to appear in the 1920s. Since then, soft drink vending machines have become increasingly popular. Both hot and cold drinks are sold in these self-service machines throughout the world.

Consumption

[edit]Per capita consumption of soda varies considerably around the world. As of 2014, the top consuming countries per capita were Argentina, the United States, Chile, and Mexico. Developed countries in Europe and elsewhere in the Americas had considerably lower consumption. Annual average consumption in the United States, at 153.5 liters, was about twice that in the United Kingdom (77.7) or Canada (85.3).[33]

In recent years, soda consumption has generally declined in the West. According to one estimate, per capita consumption in the United States reached its peak in 1998 and has continually fallen since.[34] A study in the journal Obesity found that from 2003 to 2014 the proportion of Americans who drank a sugary beverage on a given day fell from approximately 62% to 50% for adults, and from 80% to 61% for children.[35] The decrease has been attributed to, among other factors, an increased awareness of the dangers of obesity, and government efforts to improve diets.

At the same time, soda consumption has increased in some low- or middle-income countries such as Cameroon, Georgia, India and Vietnam as soda manufacturers increasingly target these markets and consumers have increasing discretionary income.[33]

Production

[edit]

Soft drinks are made by mixing dry or fresh ingredients with water. Production of soft drinks can be done at factories or at home. Soft drinks can be made at home by mixing a syrup or dry ingredients with carbonated water, or by Lacto-fermentation. Syrups are commercially sold by companies such as Soda-Club; dry ingredients are often sold in pouches, in a style of the popular U.S. drink mix Kool-Aid. Carbonated water is made using a soda siphon or a home carbonation system or by dropping dry ice into water. Food-grade carbon dioxide, used for carbonating drinks, often comes from ammonia plants.[36]

Drinks like ginger ale and root beer are often brewed using yeast to cause carbonation.

Of most importance is that the ingredient meets the agreed specification on all major parameters. This is not only the functional parameter (in other words, the level of the major constituent), but the level of impurities, the microbiological status, and physical parameters such as color, particle size, etc.[37]

Some soft drinks contain measurable amounts of alcohol. In some older preparations, this resulted from natural fermentation used to build the carbonation. In the United States, soft drinks (as well as other products such as non-alcoholic beer) are allowed by law to contain up to 0.5% alcohol by volume. Modern drinks introduce carbon dioxide for carbonation, but there is some speculation that alcohol might result from fermentation of sugars in a non-sterile environment. A small amount of alcohol is introduced in some soft drinks where alcohol is used in the preparation of the flavoring extracts such as vanilla extract.[38]

Producers

[edit]

Market control of the soft drink industry varies on a country-by-country basis. However, PepsiCo and the Coca-Cola Company remain the two largest producers of soft drinks in most regions of the world. In North America, Keurig Dr Pepper and Jones Soda also hold a significant amount of market share.

Health concerns

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (November 2020) |

This section needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (November 2020) |

The over-consumption of sugar-sweetened soft drinks is associated with obesity,[39][40][41][42] hypertension,[43] type 2 diabetes,[44] dental caries, and low nutrient levels.[41] A few experimental studies reported the role sugar-sweetened soft drinks potentially contribute to these ailments,[40][41] though other studies show conflicting information.[45][46][47] According to a 2013 systematic review of systematic reviews, 83.3% of the systematic reviews without reported conflict of interest concluded that sugar-sweetened soft drinks consumption could be a potential risk factor for weight gain.[48]

Obesity and weight-related diseases

[edit]From 1977 to 2002, Americans doubled their consumption of sweetened beverages[49]—a trend that was paralleled by doubling the prevalence of obesity.[50] The consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages is associated with weight and obesity, and changes in consumption can help predict changes in weight.[51]

The consumption of sugar-sweetened soft drinks can also be associated with many weight-related diseases, including diabetes,[44] metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular risk factors.[52]

Dental decay

[edit]

Most soft drinks contain high concentrations of simple carbohydrates: glucose, fructose, sucrose and other simple sugars. If oral bacteria ferment carbohydrates and produce acids that may dissolve tooth enamel and induce dental decay, then sweetened drinks may increase the risk of dental caries. The risk would be greater if the frequency of consumption is high.[53]

A large number of soda pops are acidic as are many fruits, sauces, and other foods. Drinking acidic drinks over a long period and continuous sipping may erode the tooth enamel. A 2007 study determined that some flavored sparkling waters are as erosive or more so than orange juice.[54]

Using a drinking straw is often advised by dentists as the drink does not come into as much contact with the teeth. It has also been suggested that brushing teeth right after drinking soft drinks should be avoided as this can result in additional erosion to the teeth due to mechanical action of the toothbrush on weakened enamel.[55]

Bone density and bone loss

[edit]A 2006 study of several thousand men and women, found that women who regularly drank cola-based sodas (three or more a day) had significantly lower bone mineral density (BMD) of about 4% in the hip compared to women who did not consume colas.[56] The study found that the effect of regular consumption of cola sodas was not significant on men's BMD.[56]

Benzene

[edit]In 2006, the United Kingdom Food Standards Agency published the results of its survey of benzene levels in soft drinks,[57] which tested 150 products and found that four contained benzene levels above the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for drinking water.

The United States Food and Drug Administration released its own test results of several soft drinks containing benzoates and ascorbic or erythorbic acid. Five tested drinks contained benzene levels above the Environmental Protection Agency's recommended standard of 5 ppb. As of 2006, the FDA stated its belief that "the levels of benzene found in soft drinks and other beverages to date do not pose a safety concern for consumers".[58]

Kidney stones

[edit]A study published in the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology in 2013 concluded that consumption of soft drinks was associated with a 23% higher risk of developing kidney stones.[59]

Mortality, circulatory and digestive diseases

[edit]In a 2019 study of 451,743 Europeans, those who had a consumption of soft drinks of two or more a day,[60] had a greater chance of all-cause mortality than those who drank less than one per month. People who drank artificially sweetened drinks had a higher risk of cardiovascular diseases, and people who drank sugar-sweetened drinks with digestive diseases.[61][62]

Government regulation

[edit]Schools

[edit]Since at least 2006, debate on whether high-calorie soft drink vending machines should be allowed in schools has been on the rise. Opponents of the soft drink vending machines believe that soft drinks are a significant contributor to childhood obesity and tooth decay, and that allowing soft drink sales in schools encourages children to believe they are safe to consume in moderate to large quantities.[63] Opponents also argue that schools have a responsibility to look after the health of the children in their care, and that allowing children easy access to soft drinks violates that responsibility.[64] Vending machine proponents believe that obesity is a complex issue and soft drinks are not the only cause.[65] A 2011 bill to tax soft drinks in California failed, with some opposing lawmakers arguing that parents—not the government—should be responsible for children's drink choices.[66]

On May 3, 2006, the Alliance for a Healthier Generation,[67] Cadbury Schweppes, the Coca-Cola Company, PepsiCo, and the American Beverage Association announced new guidelines[68] that will voluntarily remove high-calorie soft drinks from all U.S. schools.

On May 19, 2006, the British education secretary, Alan Johnson, announced new minimum nutrition standards for school food. Among a wide range of measures, from September 2006, school lunches will be free from carbonated drinks. Schools will also end the sale of junk food (including carbonated drinks) in vending machines and tuck shops.

In 2008, Samantha K Graff published an article in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science regarding the "First Amendment Implications of Restricting Food and Beverages Marketing in Schools". The article examines a school district's policy regarding limiting the sale and marketing of soda in public schools, and how certain policies can invoke a violation of the First Amendment. Due to district budget cuts and loss in state funding, many school districts allow commercial businesses to market and advertise their product (including junk food and soda) to public school students for additional revenue. Junk food and soda companies have acquired exclusive rights to vending machines throughout many public school campuses. Opponents of corporate marketing and advertising on school grounds urge school officials to restrict or limit a corporation's power to promote, market, and sell their product to school students. In the 1970s, the Supreme Court ruled that advertising was not a form of free expression, but a form of business practices which should be regulated by the government. In the 1976 case of Virginia State Board of Pharmacy v. Virginia Citizens Consumer Council,[69] the Supreme Court ruled that advertising, or "commercial speech", to some degree is protected under the First Amendment. To avoid a First Amendment challenge by corporations, public schools could create contracts that restrict the sale of certain product and advertising. Public schools can also ban the selling of all food and drink products on campus, while not infringing on a corporation's right to free speech.[70]

On December 13, 2010, President Obama signed the Healthy Hunger Free Kids Act of 2010[71] (effective in 2014) that mandates schools that receive federal funding must offer healthy snacks and drinks to students. The act bans the selling of soft drinks to students and requires schools to provide healthier options such as water, unflavored low-fat milk, 100% fruit and vegetable drinks or sugar-free carbonated drinks. The portion sizes available to students will be based on age: eight ounces for elementary schools, twelve ounces for middle and high schools. Proponents of the act predict the new mandate it will make it easier for students to make healthy drink choices while at school.[71]

In 2015, Terry-McElarth and colleagues published a study in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine on regular soda policies and their effect on school drink availability and student consumption. The purpose of the study was to determine the effectiveness of a program beginning in the 2014–2015 school year that requires schools participating in federally reimbursable meal programs to remove all competitive venues (a la carte cafeteria sales, vending machines, and stores/snack bars/carts), on the availability of unhealthy drinks at schools and student consumption. The study analyzed state- and school district-level policies mandating soda bans and found that state bans were associated with significantly lower school soda availability but district bans showed no significant associations. In addition, no significant correlation was observed between state policies and student consumption. Among student populations, state policy was directly associated with significantly lower school soda availability and indirectly associated with lower student consumption. The same was not observed for other student populations.[72]

Taxation

[edit]In the United States, legislators, health experts and consumer advocates are considering levying higher taxes on the sale of soft drinks and other sweetened products to help curb the epidemic of obesity among Americans, and its harmful impact on overall health. Some speculate that higher taxes could help reduce soda consumption.[73] Others say that taxes should help fund education to increase consumer awareness of the unhealthy effects of excessive soft drink consumption, and also help cover costs of caring for conditions resulting from overconsumption.[74] The food and drink industry holds considerable clout in Washington, DC, as it has contributed more than $50 million to legislators since 2000.[75]

In January 2013, a British lobby group called for the price of sugary fizzy drinks to be increased, with the money raised (an estimated £1 billion at 20p per litre) to be put towards a "Children's Future Fund", overseen by an independent body, which would encourage children to eat healthily in school.[76]

In 2017, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain imposed a 50% tax on soft drinks and a 100% tax on energy drinks to curb excess consumption of the commodity and for additional revenue.[77]

Attempted ban

[edit]In March 2013, New York City's mayor Michael Bloomberg proposed to ban the sale of non-diet soft drinks larger than 16 ounces, except in convenience stores and supermarkets. A lawsuit against the ban was upheld by a state judge, who voiced concerns that the ban was "fraught with arbitrary and capricious consequences". Bloomberg announced that he would be appealing the verdict.[78] The state appellate courts upheld the trial court decision, and the ban remains unenforceable as of 2021.[79][80]

In 2022, amidst soaring rates of obesity and diabetes, the Mexican state of Oaxaca enacted a ban on sugary drinks, including notably Coca-Cola, but it was poorly enforced.[81]

See also

[edit]- Ade

- Craft soda

- Diet soda

- Energy drink

- Phosphate soda

- Fizz-Keeper

- Hard soda

- Industrial gas

- Kombucha

- List of brand name soft drink products

- List of soft drink flavors

- List of soft drinks by country

- List of drinks

- Low-alcohol beer

- Nitrogenation

- Nucleation

- Premix and postmix

- Soda fountain

- Squash (drink)

References

[edit]- ^ "Soft drink | Definition, History, Production, & Health Issues | Britannica". www.britannica.com. May 8, 2025. Retrieved May 22, 2025.

- ^ "Electronic Code of Federal Regulations". United States Government. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2011. See §7.71, paragraphs (e) and (f).

- ^ "What Is Meant By Alcohol-Free? | The Alcohol-Free Community". Alcoholfree.co.uk. January 8, 2012. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ Bangor Daily News, April 8, 2010

- ^ "Schweppes Holdings Limited". Royalwarrant.org. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

Schweppes was founded in 1783 [..] the world's first ever soft drink, Schweppes soda water, was born.

- ^ a b c "The great soda-water shake up". The Atlantic. October 2014. Archived from the original on June 24, 2022. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c Vaux, Bert (2003). "105. What is your generic term for a sweetened carbonated beverage?". Harvard Dialect Survey. Archived from the original on May 24, 2011. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ^ a b "Funny Irish Words and Phrases". Grammar YourDictionary. Archived from the original on April 3, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ Kregiel, Dorota (January 28, 2015). "Health Safety of Soft Drinks: Contents, Containers, and Microorganisms". BioMed Research International. 2015 e128697. doi:10.1155/2015/128697. ISSN 2314-6133. PMC 4324883. PMID 25695045.

- ^ "Sugary Drinks". Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. September 4, 2013. Archived from the original on July 10, 2022. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ "In Boston, the word 'tonic' gives way to 'soda'". BostonGlobe.com. March 25, 2012. Archived from the original on August 1, 2015. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- ^ Hannay, Chris (May 18, 2012). "Why do some places say 'pop' and others say 'soda'? Your questions answered". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- ^ "The Best of British". effingpot.com. Archived from the original on August 29, 2015. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- ^ "Dictionaries of the Scots Language:: SND :: sndns1727". Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- ^ For example, in "Coca-Cola Amatil admits cutting back on sugar as attitudes change on health and investment" Archived October 16, 2015, at the Wayback Machine – The Sydney Morning Herald, September 11, 2015. Retrieved September 12, 2015.

- ^ "Fizzy Drinks: Everything you need to know". www.lifeeducation.org.au. Archived from the original on September 11, 2021. Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- ^ "Definition of "cool drink"". Collins English Dictionary. Archived from the original on October 1, 2015. Retrieved September 11, 2015.

- ^ "The Interesting History of Soft Drinks". ThoughtCo. Archived from the original on April 20, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ a b "soft drink | Definition, History, Production, & Health Issues". Britannica. Archived from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ Meri, Josef W. (2005). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 106. ISBN 1-135-45596-1. Archived from the original on November 13, 2021. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Colin Emmins. "SOFT DRINKS Their origins and history" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 6, 2015.

- ^ Crandall, Philip; Chen, Chin Shu; Nagy, Steven; Perras, Georges; Buchel, Johannes A.; Riha, William (2000). "Beverages, nonalcoholic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a04_035. ISBN 3-527-30673-0.

- ^ Bellis, Mary (March 6, 2009). "The discovery of oxygen and Joseph Priestley". Thoughtco.com. Archived from the original on March 28, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ^ a b "Priestley 1772: Impregnating water with fixed air" (PDF). truetex.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 21, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ^ Morgenthaler, Jeffrey (2014). Bar Book: Elements of cocktail technique. Chronicle Books. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-4521-3027-9. Archived from the original on May 13, 2022. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ "Heritage: Meet Jacob Schweppe". Archived from the original on October 12, 2018. Retrieved July 6, 2015.

- ^ Phosphates, in Smith, Andrew. The Oxford companion to American food and drink. Oxford University Press US, 2007, ISBN 0-19-530796-8, p.451

- ^ a b c Emmins, Colin (1991). SOFT DRINKS – Their origins and history (PDF). Great Britain: Shire Publications Ltd. p. 8 and 11. ISBN 0-7478-0125-8. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 6, 2015.

- ^ "Chester homeless charity teams up with lemonade brand". Cheshire Live. October 8, 2017. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- ^ Raustiala, Kal (August 28, 2013). "The Imperial Cocktail". Slate. The Slate Group. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- ^ ""Secret lemonade drinker": the story of R White's and successors in Barking and Essex". Barking and District Historical Society. Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ Brontë, Anne (1922). Wildfell Hall, ch. 30. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ a b Silver, Marc (June 19, 2015). "Guess Which Country Has The Biggest Increase In Soda Drinking". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on April 27, 2019. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- ^ Holodny, Elena. "The epic collapse of American soda consumption in one chart". Business Insider. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ Bakalar, Nicholas (November 14, 2017). "Americans Are Putting Down the Soda Pop". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ "CO2 shortage: Food industry calls for government action". BBC. June 21, 2018. Archived from the original on May 23, 2021. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- ^ Ashurst, P. (2009). Soft drink and fruit juice problems solved. Woodhead Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-84569-326-8.

- ^ "[myMasjid.com.my] Alcohol: In soft drinks". Mail-archive.com. November 8, 2004. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ^ Bes-Rastrollo, M; Sayon-Orea, C; Ruiz-Canela, M; Martinez-Gonzalez, MA (July 2016). "Impact of sugars and sugar taxation on body weight control: A comprehensive literature review". Obesity. 24 (7): 1410–26. doi:10.1002/oby.21535. ISSN 1930-7381. PMID 27273733.

- ^ a b Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB (2006). "Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 84 (2): 274–88. doi:10.1093/ajcn/84.2.274. PMC 3210834. PMID 16895873.

- ^ a b c Vartanian LR, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD (2007). "Effects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis". American Journal of Public Health. 97 (4): 667–75. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.083782. PMC 1829363. PMID 17329656.

- ^ Woodward-Lopez G, Kao J, Ritchie L (2011). "To what extent have sweetened beverages contributed to the obesity epidemic?". Public Health Nutrition. 14 (3): 499–509. doi:10.1017/S1368980010002375. PMID 20860886.

- ^ Kim, Y; Je, Y (April 2016). "Prospective association of sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverage intake with risk of hypertension". Archives of Cardiovascular Diseases. 109 (4): 242–53. doi:10.1016/j.acvd.2015.10.005. PMID 26869455.

- ^ a b Imamura F, O'Connor L, Ye Z, Mursu J, Hayashino Y, Bhupathiraju SN, Forouhi NG (2015). "Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction". BMJ. 351 h3576. doi:10.1136/bmj.h3576. PMC 4510779. PMID 26199070.

- ^ Gibson S (2008). "Sugar-sweetened soft drinks and obesity: a systematic review of the evidence from observational studies and interventions". Nutrition Research Reviews. 21 (2): 134–47. doi:10.1017/S0954422408110976. PMID 19087367.

- ^ Wolff E, Dansinger ML (2008). "Soft drinks and weight gain: how strong is the link?". Medscape Journal of Medicine. 10 (8): 189. PMC 2562148. PMID 18924641.

- ^ Trumbo PR, Rivers CR (2014). "Systematic review of the evidence for an association between sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and risk of obesity". Nutrition Reviews. 72 (9): 566–74. doi:10.1111/nure.12128. PMID 25091794. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2020.

- ^ Bes-Rastrollo, Maira; Schulze, Matthias B.; Ruiz-Canela, Miguel; Martinez-Gonzalez, Miguel A. (December 31, 2013). "Financial Conflicts of Interest and Reporting Bias Regarding the Association between Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Weight Gain: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews". PLOS Medicine. 10 (12) e1001578. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001578. ISSN 1549-1676. PMC 3876974. PMID 24391479.

- ^ Nielsen, S.; Popkin, B. (2004). "Changes in beverage intake between 1977 and 2001". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 27 (3): 205–210. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2004.05.005. PMID 15450632. Archived from the original on September 26, 2022. Retrieved September 29, 2020.

- ^ Flegal, K.M.; Carroll, M.D.; Ogden, C.L.; Johnson, C.L. (2002). "Prevalence and trends in overweight among US adults, 1999–2000". Journal of the American Medical Association. 288 (14): 1723–1727. doi:10.1001/jama.288.14.1723. PMID 12365955.

- ^ "Get the Facts: Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Consumption". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. February 27, 2017. Archived from the original on June 23, 2021. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ Yoo S, Nicklas T, Baranowski T, Zakeri IF, Yang SJ, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS (2004). "Comparison of dietary intakes associated with metabolic syndrome risk factors in young adults: the Bogalusa Heart Study". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 80 (4): 841–8. doi:10.1093/ajcn/80.4.841. PMID 15447888.

- ^ Marshall TA, Levy SM, Broffitt B, Warren JJ, Eichenberger-Gilmore JM, Burns TL, Stumbo PJ (2003). "Dental caries and beverage consumption in young children". Pediatrics. 112 (3 Pt 1): e184–91. doi:10.1542/peds.112.3.e184. PMID 12949310. S2CID 2444019.

- ^ Brown, Catronia J.; Smith, Gay; Shaw, Linda; Parry, Jason; Smith, Anthony J. (March 2007). "The erosive potential of flavoured sparkling water drinks". International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry. 17 (2). British Paedodontic Society and the International Association of Dentistry for Children: 86–91. doi:10.1111/j.1365-263X.2006.00784.x. PMID 17263857.

- ^ Bassiouny MA, Yang J (2005). "Influence of drinking patterns of carbonated beverages on dental erosion". General Dentistry. 53 (3): 205–10. PMID 15960479.

- "Saved By A Straw? Sipping Soft Drinks And Other Beverages Reduces Risk Of Decay". ScienceDaily (Press release). June 17, 2005. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- ^ a b Tucker KL, Morita K, Qiao N, Hannan MT, Cupples LA, Kiel DP (2006). "Colas, but not other carbonated beverages, are associated with low bone mineral density in older women: The Framingham Osteoporosis Study". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 84 (4): 936–42. doi:10.1093/ajcn/84.4.936. PMID 17023723.

- ^ "of benzene levels in soft drinks". Food.gov.uk. March 31, 2006. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ^ "US FDA/CFSAN – Questions and Answers on the Occurrence of Benzene in Soft Drinks and Other Beverages". Archived from the original on March 26, 2008. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ^ Ferraro PM, Taylor EN, Gambaro G, Curhan GC (2013). "Soda and other beverages and the risk of kidney stones". Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 8 (8): 1389–95. doi:10.2215/CJN.11661112. PMC 3731916. PMID 23676355.

- ^ Laura, Reiley (September 4, 2019). "It doesn't matter if it's sugary or diet: New study links all soda to an early death". The Washington Post.

- ^ Mullee, Amy; Romaguera, Dora; Pearson-Stuttard, Jonathan; et al. (September 3, 2019). "Association Between Soft Drink Consumption and Mortality in 10 European Countries". JAMA Internal Medicine. 179 (11): 1479–1490. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2478. hdl:2445/168063. PMC 6724165. PMID 31479109.

- ^ Inserro, Allison (September 3, 2019). "Large European Study Links Soda Consumption to Greater Risk of Mortality, Including From Parkinson". The American Journal of Managed Care. Retrieved April 29, 2024.

- ^ "Non-diet sodas to be pulled from schools". Associated Press. May 5, 2006. Archived from the original on September 15, 2020. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- ^ "Issue 17: Debates from four states over selling soda in schools". Berkeley Media Studies Group. November 1, 2008. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- ^ "State's soda tax plan falls flat". Daily Democrat. May 29, 2013. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ^ "Soda tax nixed in state assembly committee". ABC News Los Angeles. April 25, 2011. Archived from the original on October 10, 2012.

- ^ "Alliance for a Healthier Generation". HealthierGeneration.org. Archived from the original on September 1, 2010. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- ^ Clockwork.net. "Schools". HealthierGeneration.org. Archived from the original on September 1, 2010. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- ^ "Va. Pharmacy Bd. v. Va. Consumer Council 425 U.S. 748 (1976)". Justia.com. Archived from the original on January 31, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- ^ Graff, S. K. (2008). "First Amendment Implications of Restricting Food and Beverage Marketing in Schools". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 615 (1): 157–77. doi:10.1177/0002716207308398. JSTOR 25097981. S2CID 154286599.

- ^ a b "Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act – Food and Nutrition Service". USDA.gov. Archived from the original on February 15, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- ^ Terry-McElrath YM, Chriqui JF, O'Malley PM, Chaloupka FJ, Johnston LD (2015). "Regular soda policies, school availability, and high school student consumption". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 48 (4): 436–44. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.022. PMC 4380673. PMID 25576493.

- ^ Duffey KJ, Gordon-Larsen P, Shikany JM, Guilkey D, Jacobs DR, Popkin BM (2010). "Food price and diet and health outcomes: 20 years of the CARDIA Study". Archives of Internal Medicine. 170 (5): 420–6. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.545. PMC 3154748. PMID 20212177.

- ^ "USA Today, Experts: penny per ounce to fight obesity, health costs. Sept 18 2009". September 18, 2009. Archived from the original on October 17, 2009. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- ^ "Food and Beverage industry profile". OpenSecrets. February 18, 2013. Archived from the original on August 8, 2009. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ^ "61 organisations call for a sugary drinks duty". Govtoday.co.uk. January 29, 2013. Archived from the original on February 16, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ Backholer K, Blake M, Vandevijvere S (2017). "Sugar-sweetened beverage taxation: An update on the year that was 2017". Public Health Nutrition. 20 (18): 3219–3224. doi:10.1017/s1368980017003329. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30105615. PMC 10261626. PMID 29160766.

- ^ "New York Soda Ban Struck Down, Bloomberg Promises Appeal – U.S. News & World Report". USNews.com. March 11, 2013. Archived from the original on March 27, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ "NYC's Super-size Soda Ban declared Unconstitutional | O'Neill Institute". July 31, 2013. Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "A Look Back at Mike Bloomberg's Failed New York City Soda Ban". February 19, 2020. Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ Busby, Mattha (November 4, 2022). "Sugar rush: how Mexico's addiction to fizzy drinks fuelled its health crisis". The Guardian.

Further reading

[edit]- "Beverage group: Pull soda from primary schools", USA Today, August 17, 2005

- "After soda ban nutritionists say more can be done", The Boston Globe, May 4, 2006

- "Critics Say Soda Policy for Schools Lacks Teeth", The New York Times, August 22, 2006

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of soft drink at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of soft drink at Wiktionary Quotations related to Soft drink at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Soft drink at Wikiquote Soft drink travel guide from Wikivoyage

Soft drink travel guide from Wikivoyage Media related to Soft drinks at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Soft drinks at Wikimedia Commons

Soft drink

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Terminology

Scope and Characteristics

Soft drinks constitute a category of non-alcoholic beverages formulated primarily for refreshment, distinguished by the inclusion of sweeteners and flavorings to enhance palatability, with carbonation present in many but not all varieties.[1] This scope encompasses carbonated options such as colas and lemon-lime sodas, alongside non-carbonated counterparts like sweetened fruit-flavored drinks, but excludes unsweetened beverages like plain water or pure fruit juices.[1] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration regulates carbonated soft drinks under standards ensuring safety, sanitation, and accurate labeling, while broader formulations fall under general food beverage guidelines.[11] Key characteristics include a high water content, typically comprising 90% of regular formulations and up to 99% in low-calorie versions, serving as the base for dissolving other components.[12] Sweeteners, such as sucrose, high-fructose corn syrup, or non-nutritive alternatives like aspartame, provide the primary taste profile, often balanced by acidulants including phosphoric, citric, or malic acid to impart tartness and stability.[13] Flavorings—derived from natural essences, extracts, or synthetic compounds—replicate tastes of fruits, spices, or botanicals, while colorants enhance visual appeal.[2] Carbon dioxide gas, dissolved under pressure in carbonated types, generates effervescence and a sensory "bite" upon release, contributing to mouthfeel and refreshment perception.[14] Preservatives like sodium benzoate or potassium sorbate may be added to inhibit microbial growth, particularly in formulations susceptible to spoilage, and some variants incorporate caffeine for stimulatory effects, as in cola beverages.[15] These beverages are generally served chilled to optimize carbonation retention and sensory enjoyment, packaged in bottles, cans, or fountain dispensers for convenience and portability.[16] Overall, soft drinks prioritize sensory attributes over nutritional value, with compositions engineered for consistent flavor delivery across production scales.[12]Etymology and Regional Terms

The term "soft drink" originated in the 19th century to distinguish non-alcoholic beverages from "hard" liquor, which contained distilled alcohol, during a period when temperance advocates promoted such drinks as safer alternatives amid rising concerns over alcohol consumption.[17] This nomenclature reflected the beverages' milder effects, lacking the intoxicating potency of spirits, and initially encompassed a broad range of non-alcoholic options beyond just carbonated varieties. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, however, the term narrowed in common usage to primarily denote sweetened, carbonated drinks due to their commercial proliferation following innovations in bottling and flavoring.[18] In the United States, regional dialects for soft drinks exhibit distinct patterns tied to historical production and marketing. "Soda" prevails in the Northeast, parts of the Midwest, California, and Florida, deriving from "soda water"—early carbonated beverages effervesced with sodium bicarbonate or similar salts for stability and fizz.[19] "Pop," dominant in the Midwest (including Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, Minnesota, and Pennsylvania) and Pacific Northwest, traces to the audible pop of uncorking pressurized bottles in the mid-19th century, with records indicating the term's first use around 1861 alongside the rise of mass-produced seltzer-based drinks.[20] In Southern states like Georgia, Alabama, and Texas, "Coke" functions as a generic synonym for any soft drink, stemming from Coca-Cola's early 20th-century market saturation after its 1886 debut in Atlanta, which conditioned consumers to associate carbonated beverages with the brand irrespective of flavor.[21] Internationally, equivalents vary by linguistic and cultural influences. In the United Kingdom and Ireland, "fizzy drink" or "fizzy pop" emphasizes carbonation, while "pop" alone persists in northern England; Australia and New Zealand standardize "soft drink" akin to American formal usage. In Scotland, "juice" colloquially denotes carbonated soft drinks despite minimal fruit content, a holdover from post-World War II marketing of artificially flavored varieties as economical alternatives to fresh juices. These variations underscore how local bottling industries and colonial trade routes shaped terminology, often prioritizing descriptive sounds or dominant brands over uniform global standards.Historical Development

Pre-Industrial Origins

The precursors to modern soft drinks consisted primarily of non-alcoholic infusions, fruit-based mixtures, and naturally effervescent waters consumed for refreshment or medicinal purposes across ancient and medieval societies. In ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, boiled barley water or herbal decoctions served as basic non-alcoholic beverages, often flavored with dates or spices to mask impurities in plain water, though these lacked the sweetness and standardization of later formulations.[22] Similarly, Roman and Greek cultures utilized naturally carbonated mineral springs, such as those at Baiae or Selters, where the inherent effervescence from dissolved carbon dioxide was prized for purported digestive benefits, with waters bottled and transported as early as the 1st century CE for elite consumption.[23] By the medieval period, Islamic scholars and physicians in Persia and the Middle East developed sharbat, concentrated syrups of fruits like quince, pomegranate, or rose petals boiled with sugar and diluted with water or snow for cooling drinks, as documented in texts from around 1000 CE; these non-alcoholic elixirs influenced trade routes and spread to Europe via the Crusades and Moorish Spain.[24] In 10th-century Cairo, qatarmizat—a blend of lemon juice, sugar, and water—emerged as an early citrus-based refreshment, valued for its tartness and preservative qualities in hot climates, predating widespread European adoption.[25] European medieval recipes included possets (spiced milk curds) and flower waters like rose or lavender infusions soaked in sweetened liquid, consumed by nobility to avoid the alcohol-heavy diets of small beers and ales.[26] In the early modern era leading to industrialization, lemonade solidified as a proto-soft drink in Europe. Parisian vendors formed the Compagnie de Limonadiers in 1676 to sell diluted lemon juice sweetened with honey from portable tanks, targeting urban markets for a non-intoxicating alternative to wine or beer.[27] The earliest English reference to lemonade appears in a 1663 publication, describing it as a flavored water drink amid growing imports of citrus from colonial trade.[23] These beverages remained artisanal, reliant on seasonal fruits, manual squeezing, and natural preservatives like sugar, without mechanical carbonation or mass production, distinguishing them from post-1760s innovations.[28]Carbonation and Early Commercialization

The process of artificially carbonating water originated with English chemist Joseph Priestley, who in 1767 devised a method to dissolve carbon dioxide—then termed "fixed air"—into water by suspending a vessel of water over a fermenting beer vat in Leeds, allowing the gas to infuse the liquid under pressure.[29][30] Priestley detailed this technique in his 1772 publication Impregnating Water with Fixed Air in Order to Explore the Supposed Virtues of Pyrmont Water, promoting carbonated water as a healthful alternative mimicking natural mineral springs believed to aid digestion and treat ailments like scurvy.[29] Swedish chemist Torbern Bergman independently advanced similar experiments in the 1770s, using sulfuric acid and chalk to generate CO2 for infusion, further establishing the scientific basis for artificial aeration.[3] Commercial production of carbonated water began in the late 18th century, driven by demand for therapeutic beverages. In 1783, German-born watchmaker and amateur chemist Johann Jacob Schweppe in Geneva developed an improved apparatus—a compression pump—for manufacturing aerated water on a viable scale, founding the precursor to the Schweppes company to bottle and sell it as "Soda Water."[3][31] Schweppe's product gained traction among Europe's elite for its purported medicinal properties, often flavored with fruit essences or herbs to mask the initial metallic taste from imperfect CO2 sources, marking the shift from laboratory curiosity to marketable good.[3] By 1790, Schweppe relocated operations to London, where he established a factory producing up to 60 bottles daily, expanding distribution through pharmacies and apothecaries who mixed the effervescent base with syrups for flavored tonics.[32] Early commercialization faced technical hurdles, including inconsistent carbonation retention and contamination risks during bottling, yet it spurred innovation in containment. Corked glass bottles, sealed with wire, were standard but prone to explosion from pressure buildup, limiting scalability until later patents like Hiram Codd's 1872 glass marble-stopper design—though postdating initial efforts, it addressed persistent leakage issues rooted in these nascent ventures.[3] In the United States, carbonated beverages emerged around 1807 with Philadelphia pharmacist Philip Syng Physick adding flavors to Priestley-inspired soda water, while the first commercial soda fountain appeared in 1819, invented by Samuel Fahnestock to dispense flavored versions at drugstores.[33] These developments positioned carbonated soft drinks as accessible refreshments, transitioning from elite health elixirs to broader consumer staples by the early 19th century.[34]Industrial Expansion and Branding

The industrial expansion of soft drinks accelerated in the mid-to-late 19th century, driven by advancements in bottling and distribution that enabled mass production beyond soda fountains. In the United States, the number of bottling plants increased from 123 in 1860 to 387 by 1870, reflecting growing consumer demand and improved manufacturing capabilities.[35] [36] This proliferation coincided with the commercialization of flavored carbonated beverages, shifting from artisanal pharmacy concoctions to scalable factory outputs. Key innovations facilitated this growth, including the crown cork bottle cap patented by William Painter in 1892, which provided a reliable seal for retaining carbonation during transport and storage.[37] Simultaneously, franchising models emerged to decentralize production; for instance, The Coca-Cola Company, founded in 1886 by John Pemberton as a syrup sold at Atlanta soda fountains, adopted a bottling franchise system in 1899 under Asa Candler's ownership, allowing independent operators to produce and distribute the product nationwide.[38] This approach reduced capital intensity for the parent company while expanding market reach, with Coca-Cola's output scaling from initial handwritten tickets to millions of servings by the early 1900s through such licensing. Branding became integral to differentiation amid rising competition, with early leaders leveraging distinctive logos and marketing. Coca-Cola's Spencerian script logo, introduced in 1886, and Candler's campaigns—distributing free coupons, branded merchandise, and signage—established it as a cultural icon by the 1890s, emphasizing refreshment over medicinal origins.[38] Pepsi-Cola, formulated in 1893 by Caleb Bradham as a digestive aid and renamed in 1898, adopted iterative logos and slogans like "The Original Pure Food Drink" by 1906 to compete, though it faced early bankruptcies before stabilizing.[39] To combat imitation, Coca-Cola commissioned the patented contour bottle in 1915, designed for tactile recognition even in the dark, further solidifying brand loyalty.[40] Mass marketing innovations, including newspaper ads and painted advertisements on buildings, propelled industry leaders; by the 1920s, automated bottling lines enhanced efficiency, supporting exponential volume growth as soft drinks transitioned from local novelties to everyday consumer staples.[34][40]Post-1945 Globalization

Following the conclusion of World War II in 1945, American soft drink manufacturers, particularly The Coca-Cola Company, capitalized on wartime infrastructure to accelerate international expansion. During the conflict, Coca-Cola had deployed 64 portable bottling plants to supply U.S. troops in Europe, North Africa, and Asia, fulfilling a pledge by company president Robert Woodruff to provide every service member with a five-cent bottle.[38] These facilities transitioned to permanent civilian operations postwar, enabling the company to establish bottling networks in newly accessible markets and convert military demand into local consumer bases.[41] Exposure through Allied forces introduced the beverage to civilian populations, fostering initial demand amid reconstruction and American cultural influence.[42] Pepsi-Cola, reorganized as PepsiCo post-1945, pursued similar globalization by relocating its headquarters to Manhattan and targeting emerging markets in Latin America, the Middle East, and the Philippines.[43] This era marked the onset of franchised bottling models worldwide, allowing localized production while maintaining brand consistency through syrup exports from the U.S. By the 1950s, both Coca-Cola and Pepsi had entrenched positions in Europe and Asia, often navigating trade barriers; for instance, France imposed an import ban on Coca-Cola from 1945 to 1953 to shield domestic producers, delaying but not preventing entry.[44] Such expansions symbolized broader postwar economic liberalization, with U.S. firms leveraging Marshall Plan aid corridors and military bases to distribute products.[45] Global soft drink consumption proliferated through the late 20th century, driven by urbanization, refrigeration advancements, and marketing adaptations to local tastes, such as region-specific flavors. In developing economies, per capita intake rose sharply; for example, U.S. consumption climbed from approximately 10 gallons per person in 1950 to over 50 gallons by 2000, with analogous patterns in international markets as multinational brands dominated shelf space.[46] By the 2000s, the industry had evolved into a $300 billion-plus annual market, with Coca-Cola and PepsiCo controlling over 50% of global volume through acquisitions and joint ventures in China, India, and Eastern Europe post-Cold War.[47] This dominance reflected efficient supply chains and aggressive advertising, though local competitors persisted in regions like Africa and the Middle East.[48]Adaptations to Health and Regulatory Pressures

In response to growing evidence linking excessive consumption of sugar-sweetened soft drinks to obesity, type 2 diabetes, and related conditions, major producers introduced low- and no-calorie variants using artificial sweeteners as early as the 1950s. The first commercial diet soft drink, No-Cal Ginger Ale, was developed in 1952 by Kirsch Beverages specifically for diabetic patients in a Brooklyn hospital.[49] This was followed by Royal Crown Cola's Diet Rite in 1958, Coca-Cola's Tab in 1963, and the landmark launch of Diet Coke in 1982, which quickly became one of the best-selling diet beverages globally due to its use of aspartame and broad marketing appeal.[50] [51] These formulations addressed consumer demand for calorie reduction amid rising awareness of caloric intake's role in weight gain, with diet sodas comprising a significant market share by the 1980s—Tab alone peaked at over 20% of Coca-Cola's U.S. sales in the 1970s.[52] Regulatory pressures intensified from the 2000s onward, particularly through excise taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) aimed at curbing consumption. Berkeley, California, implemented the first U.S. city-level soda tax of 1 cent per ounce in 2014, resulting in a 33.1% average retail price increase for SSBs over two years and a corresponding decline in purchases.[53] Similar taxes in Philadelphia (1.5 cents per ounce, 2017) and other U.S. cities like Oakland and Seattle led to a 33% drop in sugary drink purchases post-implementation, though substitution toward untaxed alternatives like water or diet options occurred.[54] Internationally, the UK's 2018 Soft Drinks Industry Levy (8 pence per liter for drinks with over 5 grams sugar per 100ml) prompted widespread reformulations, with producers reducing sugar content in over 50% of affected products to avoid the tax tier.[55] Industry lobbying often opposed such measures, arguing they are regressive—disproportionately burdening lower-income households without proven long-term health benefits, as evidenced by limited impacts on overall obesity rates despite consumption drops.[56] [57] To counter these pressures and align with public health guidelines like the World Health Organization's recommendation to limit free sugars to under 10% of daily energy intake, companies pursued voluntary sugar reduction and portfolio diversification. Coca-Cola committed to reducing average sugar across its portfolio by 10% globally between 2015 and 2020 through smaller packaging, low-sugar variants, and sweetener blends, achieving partial success via initiatives like Coca-Cola Life (stevia-sweetened, launched 2014).[58] PepsiCo similarly reformulated brands like Pepsi Max and expanded zero-sugar lines, while the BalanceUS coalition—formed by Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and Keurig Dr Pepper in 2021—publicly tracks progress toward low- or no-sugar beverages, reporting that nearly 60% of U.S. beverage sales in 2023 were sugar-free.[59] [60] These efforts also included self-regulation, such as removing full-sugar sodas from U.S. school vending machines following 2000s advocacy, though critics note industry-funded research has sometimes emphasized exercise over dietary limits to mitigate blame for health epidemics.[61] [62] Despite adaptations, challenges persist, including consumer resistance to altered tastes and emerging scrutiny over artificial sweeteners' long-term safety.[63]Varieties and Formulations

Carbonated Soft Drinks

Carbonated soft drinks consist of water saturated with carbon dioxide gas under pressure, producing effervescence, combined with sweeteners and flavorings to create non-alcoholic beverages. The carbonation level typically ranges from 2 to 3 volumes of dissolved CO2, measured as the volume of gas released at standard temperature and pressure per volume of liquid, which generates the sensory fizz upon opening.[64] [65] Core formulations include purified water as the base (often 90-95% of the product), nutritive sweeteners like sucrose or high-fructose corn syrup at concentrations of 10-12% by weight for regular variants, or non-nutritive alternatives such as aspartame and acesulfame potassium in low-calorie versions. Flavor systems derive from natural essences or synthetic compounds, acids like phosphoric (in colas for pH around 2.5-3.5) or citric acid provide tartness and preservation, while optional additives encompass caffeine (30-50 mg per 12 oz serving in colas), caramel coloring, and preservatives like sodium benzoate.[14] [66] [67] Common varieties include colas, which dominate global sales with formulations emphasizing kola nut-derived caffeine, vanilla, and spice notes alongside phosphoric acid for a distinctive bite; lemon-lime sodas, featuring clear citrus oils and citric acid for a lighter profile; and fruit-flavored options like orange or grape, incorporating corresponding essences and often higher citric acid levels. Ginger ales and root beers employ herbal extracts such as gingerol or sassafras substitutes (due to safrole bans since 1960), typically with milder carbonation. In 2023, cola types held the largest market share among carbonated soft drinks, reflecting consumer preference for their robust flavor and caffeine content, with global industry value exceeding $130 billion.[68] [69] [70]| Variety | Key Formulation Elements | Typical Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Cola | Phosphoric acid, caffeine, caramel color, vanilla-citrus spices | Coca-Cola, Pepsi |

| Lemon-Lime | Citric acid, lemon/lime oils, clear appearance | Sprite, 7 Up |

| Ginger Ale | Ginger extract, cane sugar, moderate carbonation | Canada Dry, Vernors |

| Root Beer | Sassafras/vanilla flavors, often vanilla creaminess | A&W, Barq's |

| Orange Soda | Orange essence, citric acid, yellow/orange dyes | Fanta, Sunkist |

Non-Carbonated Options

Non-carbonated soft drinks consist of non-alcoholic beverages sweetened with sugars or alternatives, excluding artificial carbonation, and typically include categories such as fruit juices, ready-to-drink (RTD) teas and coffees, sports drinks, and functional beverages like enhanced waters or herbal infusions. These options often emphasize natural fruit bases or botanical extracts, positioning them as digestive alternatives to fizzy drinks and aligning with consumer preferences for perceived milder impacts on gastrointestinal health.[74][75] Preceding carbonated varieties, non-carbonated soft drinks trace origins to early fruit-flavored concoctions, such as lemonade variants sold by Parisian street vendors as early as 1630, which relied on citrus juices diluted with water and sweetened for refreshment. By the 18th century, advancements in fruit preservation and bottling expanded access, though commercialization lagged behind carbonated waters until the 19th century when brands began packaging juices and syrup dilutions for mass distribution. This foundation evolved into modern formulations, driven by refrigeration and pasteurization technologies post-1900, enabling shelf-stable products without effervescence.[36][1] Key varieties include:- Fruit juices and nectars: Predominantly orange, apple, grape, and tropical blends, often pasteurized for longevity; these dominate subsegments with mixtures or smoothies adding pulp for texture.[76]

- RTD teas and coffees: Iced variants like black, green, or herbal teas, frequently citrus- or fruit-infused, with brands such as Lipton Green Tea Citrus or Nestea Lemon providing low-calorie options.[77]

- Sports and hydration drinks: Electrolyte-fortified formulas like Gatorade or Powerade, designed for rehydration during physical activity, containing salts, vitamins, and carbohydrates without fizz.[78]

- Other functional types: Lemonades (e.g., Minute Maid), vitamin-enhanced waters (e.g., Vitamin Water), and emerging low-sugar herbals or kombuchas, catering to wellness trends.[77][79]

Sweeteners, Flavors, and Additives

Soft drinks typically employ caloric sweeteners such as sucrose from cane or beet sugar and high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), with HFCS-55—containing approximately 55% fructose and 45% glucose—predominating in carbonated beverages due to its liquid form and cost advantages in processing.[82] In the United States, major producers like Coca-Cola and PepsiCo transitioned from sucrose to HFCS in the early 1980s, specifically by 1984 for Coca-Cola, driven by subsidized corn prices that made HFCS cheaper than imported sugar amid trade quotas.[83] [84] HFCS usage remains prevalent in U.S. soft drinks, contributing to average sugar contents of 10-12% by weight in full-sugar formulations, though global variations exist with sucrose more common outside North America.[85] Non-caloric sweeteners, used in "diet" or low-calorie variants, include artificial options like aspartame (200 times sweeter than sugar), sucralose (600 times sweeter), acesulfame potassium (acesulfame-K, 200 times sweeter), and saccharin (300-400 times sweeter), often blended for taste masking and stability under carbonation.[86] Acesulfame-K appears most frequently in analyzed beverages, detected in over 60% of samples in recent European studies, followed by aspartame and cyclamate.[87] Natural low-calorie alternatives like stevia-derived rebaudiosides provide zero calories but can impart bitterness at high concentrations, gaining traction amid consumer demand for "natural" labels.[86] Regulatory approvals differ, with the U.S. FDA permitting these via Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) status or food additive petitions, while the EU requires stricter pre-market authorization under more precautionary principles, banning certain blends like cyclamate in some contexts.[88] [89] Flavorings constitute 0.1-0.5% of soft drink formulations, derived from essential oils, fruit extracts, or synthetic compounds to replicate tastes like cola (a blend of citrus oils, cinnamon, vanilla, and nutmeg), lemon-lime, or berry profiles.[90] Natural flavors, comprising less than 1% of the source material by weight, are extracted from plant, animal, or microbial origins and processed via distillation or enzymatic methods, whereas artificial flavors are chemically synthesized from non-food precursors like petroleum derivatives but often identical in molecular structure to natural counterparts, offering cost and consistency benefits without nutritional differences.[91] [92] In practice, many "natural flavor" labels in soft drinks involve heavily processed isolates, with no empirical evidence of superior safety or health effects over artificial equivalents when used within approved limits.[93] Additives enhance stability, acidity, and appearance, including acids like phosphoric acid in colas for tartness and to inhibit mold (up to 0.05% by volume), citric acid in fruit flavors for brightness, and carbonic acid from CO2 dissolution for effervescence.[94] Preservatives such as sodium benzoate (0.03-0.05%) prevent microbial growth in acidic environments, while antioxidants like ascorbic acid (vitamin C) protect against oxidation in packaging.[12] [95] Colors include caramel for colas or synthetic dyes like tartrazine (E102) in some regions, with emulsifiers like gums ensuring uniformity; EU regulations prohibit certain U.S.-permitted additives like brominated vegetable oil, reflecting divergent risk assessments where the EU prioritizes precaution over U.S. post-market evidence.[96] [11] [89] Caffeine, at 10-15 mg per 100 ml in colas, functions as a flavor enhancer and stimulant but is classified as an additive under FDA oversight.[11]Production Methods

Sourcing and Ingredients

Water constitutes approximately 90-95% of most soft drink formulations, primarily sourced from municipal supplies, groundwater, or surface water, and undergoes rigorous purification processes including filtration, reverse osmosis, and disinfection to meet food-grade standards and ensure consistent taste and safety.[97][98] In production, purified water serves both as the base for beverage mixing and for operational needs like equipment cleaning, with industry benchmarks indicating an average water usage ratio of 1.5-2.5 liters per liter of product after recycling efforts.[99] Sweeteners form the second major component, with high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), particularly HFCS-55 containing 55% fructose and 45% glucose derived from corn starch via enzymatic hydrolysis, predominating in many carbonated soft drinks due to its cost-effectiveness from U.S. corn subsidies and liquid form suitability for industrial mixing.[100] Sucrose, extracted from sugarcane or sugar beets through milling and crystallization, remains common in some markets or premium variants, providing a 50/50 fructose-glucose ratio chemically akin to HFCS but often more expensive.[100] Intense sweeteners like aspartame or sucralose, sourced synthetically or from fermented sources, are increasingly used in low-calorie options to replace caloric sugars amid health concerns over obesity.[15] Acidulants such as phosphoric acid, mined from phosphate rock and processed into food-grade form, impart tartness and act as preservatives in cola beverages, while citric acid, produced via fermentation of molasses or corn by Aspergillus niger mold, is prevalent in fruit-flavored drinks for similar pH-lowering effects.[94][101] Flavors, comprising natural extracts from fruits, spices, or herbs via distillation or solvent extraction, or artificial compounds synthesized chemically, contribute the characteristic profiles, with caffeine—sourced from coffee beans, tea leaves, or synthetic production—added at levels around 34-46 mg per 12-oz serving in colas for bitterness and stimulation.[102] Carbon dioxide, captured from industrial fermentation or natural gas processing, provides effervescence, while colors (e.g., caramel from heated sugars) and preservatives (e.g., sodium benzoate from toluene derivatives) are sourced industrially to enhance appearance and shelf life.[15][2]Manufacturing Processes

The manufacturing of soft drinks primarily involves purifying water, preparing and mixing flavor concentrates or syrups, carbonating applicable formulations under controlled conditions, and aseptic filling into containers to ensure product stability and safety.[103] Water, constituting approximately 90-95% of the final product, undergoes rigorous treatment including filtration to remove particulates, activated carbon adsorption for organic compounds, reverse osmosis or ion exchange for minerals, and final sterilization via ultraviolet light or ozonation to meet beverage-grade purity standards exceeding those for potable water.[103] [104] Syrup preparation follows, where sweeteners such as sucrose, high-fructose corn syrup, or artificial alternatives are dissolved in water, then blended with flavorings, acids (e.g., citric or phosphoric for tartness and preservation), colorants, and preservatives like sodium benzoate at precise ratios—typically 1:5 syrup-to-water for dilution into the base beverage.[103] This mixture is often pasteurized at 65-75°C for 20-30 seconds in a tunnel or flash system to eliminate microbial risks before cooling, though some formulations rely on inherent acidity (pH 2.5-4.0) and later carbonation for preservation rather than heat treatment.[104] [14] For carbonated soft drinks, the cooled beverage base enters a carbonator where food-grade carbon dioxide (CO2) is injected under pressure—typically 3-5 volumes (about 5-10 g/L) at 0-4°C—using methods like injecting through porous stones or diffusers to achieve fine bubble nucleation and uniform saturation without excessive foaming.[105] Two primary systems predominate: premix, where all ingredients including CO2 are combined centrally before distribution; or postmix, where syrup and carbonated water mix at dispensing points, though the former is standard for bottled products.[14] Filling occurs in high-speed lines using isobaric (counter-pressure) techniques for carbonated variants, where bottles or cans are pressurized to match the beverage tank (around 2-4 bar) to minimize CO2 escape and foaming during transfer via volumetric piston, gravity, or tunnel fillers capable of 1,000-60,000 units per hour depending on scale.[106] Containers are pre-rinsed with sanitized water or air, filled at chilled temperatures (4-10°C), sealed with crowns, screw caps, or lids under vacuum or steam to prevent oxidation, then labeled via shrink sleeves or adhesives and secondarily packaged into cases for distribution.[103] Quality controls, including inline pH, Brix (sugar content), and CO2 level sensors, ensure consistency throughout, with reject rates under 1% in modern facilities adhering to HACCP and ISO standards.[107]Packaging, Distribution, and Innovations