Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

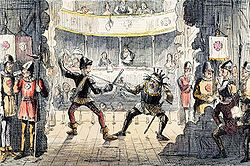

Theatre

View on Wikipedia

- Sarah Bernhardt in 1899 as Hamlet in Shakespeare's eponymous tragedy

- The character Sun Wukong at the Peking opera from Journey to the West

- Eduardo De Filippo as Pulcinella, a character from the Commedia dell'arte

- Koothu, an ancient Indian form of performing art that originated in early Tamilakam

| Part of a series on |

| Performing arts |

|---|

|

Theatre or theater[a] is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors, to present experiences of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The performers may communicate this experience to the audience through combinations of gesture, speech, song, music, and dance. It is the oldest form of drama, though live theatre has now been joined by modern recorded forms. Elements of art, such as painted scenery and stagecraft such as lighting are used to enhance the physicality, presence and immediacy of the experience.[1] Places, normally buildings, where performances regularly take place are also called "theatres" (or "theaters"), as derived from the Ancient Greek θέατρον (théatron, "a place for viewing"), itself from θεάομαι (theáomai, "to see", "to watch", "to observe").

Modern Western theatre comes, in large measure, from the theatre of ancient Greece, from which it borrows technical terminology, classification into genres, and many of its themes, stock characters, and plot elements. Theatre artist Patrice Pavis defines theatricality, theatrical language, stage writing and the specificity of theatre as synonymous expressions that differentiate theatre from the other performing arts, literature and the arts in general.[2][b]

A theatre company is an organisation that produces theatrical performances,[3] as distinct from a theatre troupe (or acting company), which is a group of theatrical performers working together.[4][5]

Modern theatre includes performances of plays and musical theatre. The art forms of ballet and opera are also theatre and use many conventions such as acting, costumes and staging. They were influential in the development of musical theatre.

History of theatre

[edit]Classical, Hellenistic Greece and Magna Graecia

[edit]

The city-state of Athens is where Western theatre originated.[7][8][9][c] It was part of a broader culture of theatricality and performance in classical Greece that included festivals, religious rituals, politics, law, athletics and gymnastics, music, poetry, weddings, funerals, and symposia.[10][9][11][12][d]

Participation in the city-state's many festivals—and mandatory attendance at the City Dionysia as an audience member (or even as a participant in the theatrical productions) in particular—was an important part of citizenship.[14] Civic participation also involved the evaluation of the rhetoric of orators evidenced in performances in the law-court or political assembly, both of which were understood as analogous to the theatre and increasingly came to absorb its dramatic vocabulary.[15][16] The Greeks also developed the concepts of dramatic criticism and theatre architecture.[17][18][19][failed verification] Actors were either amateur or at best semi-professional.[20] The theatre of ancient Greece consisted of three types of drama: tragedy, comedy, and the satyr play.[21]

The origins of theatre in ancient Greece, according to Aristotle (384–322 BCE), the first theoretician of theatre, are to be found in the festivals that honoured Dionysus. The performances were given in semi-circular auditoria cut into hillsides, capable of seating 10,000–20,000 people. The stage consisted of a dancing floor (orchestra), dressing room and scene-building area (skene). Since the words were the most important part, good acoustics and clear delivery were paramount. The actors (always men) wore masks appropriate to the characters they represented, and each might play several parts.[22]

Athenian tragedy—the oldest surviving form of tragedy—is a type of dance-drama that formed an important part of the theatrical culture of the city-state.[7][8][9][23][24][e] Having emerged sometime during the 6th century BCE, it flowered during the 5th century BCE (from the end of which it began to spread throughout the Greek world), and continued to be popular until the beginning of the Hellenistic period.[26][27][8][f]

No tragedies from the 6th century BCE and only 32 of the more than a thousand that were performed in during the 5th century BCE have survived.[29][30][g] We have complete texts extant by Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides.[31][h] The origins of tragedy remain obscure, though by the 5th century BCE it was institutionalized in competitions (agon) held as part of festivities celebrating Dionysus (the god of wine and fertility).[32][33] As contestants in the City Dionysia's competition (the most prestigious of the festivals to stage drama) playwrights were required to present a tetralogy of plays (though the individual works were not necessarily connected by story or theme), which usually consisted of three tragedies and one satyr play.[34][35][i] The performance of tragedies at the City Dionysia may have begun as early as 534 BCE; official records (didaskaliai) begin from 501 BCE, when the satyr play was introduced.[36][34][j]

Most Athenian tragedies dramatize events from Greek mythology, though The Persians—which stages the Persian response to news of their military defeat at the Battle of Salamis in 480 BCE—is the notable exception in the surviving drama.[34][k] When Aeschylus won first prize for it at the City Dionysia in 472 BCE, he had been writing tragedies for more than 25 years, yet its tragic treatment of recent history is the earliest example of drama to survive.[34][38] More than 130 years later, the philosopher Aristotle analysed 5th-century Athenian tragedy in the oldest surviving work of dramatic theory—his Poetics (c. 335 BCE).

Athenian comedy is conventionally divided into three periods, "Old Comedy", "Middle Comedy", and "New Comedy". Old Comedy survives today largely in the form of the eleven surviving plays of Aristophanes, while Middle Comedy is largely lost (preserved only in relatively short fragments in authors such as Athenaeus of Naucratis). New Comedy is known primarily from the substantial papyrus fragments of Menander. Aristotle defined comedy as a representation of laughable people that involves some kind of blunder or ugliness that does not cause pain or disaster.[l]

In addition to the categories of comedy and tragedy at the City Dionysia, the festival also included the Satyr Play. Finding its origins in rural, agricultural rituals dedicated to Dionysus, the satyr play eventually found its way to Athens in its most well-known form. Satyr's themselves were tied to the god Dionysus as his loyal woodland companions, often engaging in drunken revelry and mischief at his side. The satyr play itself was classified as tragicomedy, erring on the side of the more modern burlesque traditions of the early twentieth century. The plotlines of the plays were typically concerned with the dealings of the pantheon of Gods and their involvement in human affairs, backed by the chorus of Satyrs. However, according to Webster, satyr actors did not always perform typical satyr actions and would break from the acting traditions assigned to the character type of a mythical forest creature.[39]

The Greek colonists in Southern Italy, the so-called Magna Graecia, brought theatrical art from their motherland.[40] The Greek Theatre of Syracuse, the Greek Theatre of Segesta, the Greek Theatre of Tindari, the Greek Theatre of Hippana, the Greek Theatre of Akrai, the Greek Theatre of Monte Jato, the Greek Theatre of Morgantina and the most famous Greek Theater of Taormina, amply demonstrate this. Only fragments of original dramaturgical works are left, but the tragedies of the three great giants Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides and the comedies of Aristophanes are known.[41] Some famous playwrights in the Greek language came directly from Magna Graecia. Others, such as Aeschylus and Epicharmus, worked for a long time in Sicily. Epicharmus can be considered Syracusan in all respects, having worked all his life with the tyrants of Syracuse. His comedy preceded that of the more famous Aristophanes by staging the gods for the first time in comedy. While Aeschylus, after a long stay in the Sicilian colonies, died in Sicily in the colony of Gela in 456 BC. Epicarmus and Phormis, both of 6th century BC, are the basis, for Aristotle, of the invention of the Greek comedy, as he says in his book on Poetics:[42]

As for the composition of the stories (Epicharmus and Phormis) it came in the beginning from Sicily

— Aristotle, Poetics

Other native dramatic authors of Magna Graecia, in addition to the Syracusan Formides mentioned, are Achaeus of Syracuse, Apollodorus of Gela, Philemon of Syracuse and his son Philemon the younger. From Calabria, precisely from the colony of Thurii, came the playwright Alexis. While Rhinthon, although Sicilian from Syracuse, worked almost exclusively for the colony of Taranto in Apulia.[43]

Roman theatre

[edit]

Western theatre developed and expanded considerably under the Romans. The Roman historian Livy wrote that the Romans first experienced theatre in the 4th century BC, with a performance by Etruscan actors.[44] Beacham argues that Romans had been familiar with "pre-theatrical practices" for some time before that recorded contact.[45] The theatre of ancient Rome was a thriving and diverse art form, ranging from festival performances of street theatre, nude dancing, and acrobatics, to the staging of Plautus's broadly appealing situation comedies, to the high-style, verbally elaborate tragedies of Seneca. Although Rome had a native tradition of performance, the Hellenization of Roman culture in the 3rd century BC had a profound and energizing effect on Roman theatre and encouraged the development of Latin literature of the highest quality for the stage.

Following the expansion of the Roman Republic (509–27 BC) into several Greek territories between 270 and 240 BC, Rome encountered Greek drama.[46] From the later years of the republic and by means of the Roman Empire (27 BC-476 AD), theatre spread west across Europe, around the Mediterranean and reached England; Roman theatre was more varied, extensive and sophisticated than that of any culture before it.[47] While Greek drama continued to be performed throughout the Roman period, the year 240 BC marks the beginning of regular Roman drama.[46][m] From the beginning of the empire, however, interest in full-length drama declined in favour of a broader variety of theatrical entertainments.[48]

The first important works of Roman literature were the tragedies and comedies that Livius Andronicus wrote from 240 BC.[49] Five years later, Gnaeus Naevius also began to write drama.[49] No plays from either writer have survived. While both dramatists composed in both genres, Andronicus was most appreciated for his tragedies and Naevius for his comedies; their successors tended to specialise in one or the other, which led to a separation of the subsequent development of each type of drama.[49] By the beginning of the 2nd century BC, drama was firmly established in Rome and a guild of writers (collegium poetarum) had been formed.[50]

The Roman comedies that have survived are all fabula palliata (comedies based on Greek subjects) and come from two dramatists: Titus Maccius Plautus (Plautus) and Publius Terentius Afer (Terence).[51] In re-working the Greek originals, the Roman comic dramatists abolished the role of the chorus in dividing the drama into episodes and introduced musical accompaniment to its dialogue (between one-third of the dialogue in the comedies of Plautus and two-thirds in those of Terence).[52] The action of all scenes is set in the exterior location of a street and its complications often follow from eavesdropping.[52] Plautus, the more popular of the two, wrote between 205 and 184 BC and twenty of his comedies survive, of which his farces are best known; he was admired for the wit of his dialogue and his use of a variety of poetic meters.[53] All of the six comedies that Terence wrote between 166 and 160 BC have survived; the complexity of his plots, in which he often combined several Greek originals, was sometimes denounced, but his double-plots enabled a sophisticated presentation of contrasting human behaviour.[53]

No early Roman tragedy survives, though it was highly regarded in its day; historians know of three early tragedians—Quintus Ennius, Marcus Pacuvius and Lucius Accius.[52] From the time of the empire, the work of two tragedians survives—one is an unknown author, while the other is the Stoic philosopher Seneca.[54] Nine of Seneca's tragedies survive, all of which are fabula crepidata (tragedies adapted from Greek originals); his Phaedra, for example, was based on Euripides' Hippolytus.[55] Historians do not know who wrote the only extant example of the fabula praetexta (tragedies based on Roman subjects), Octavia, but in former times it was mistakenly attributed to Seneca due to his appearance as a character in the tragedy.[54]

In contrast to Ancient Greek theatre, the theatre in Ancient Rome did allow female performers. While the majority were employed for dancing and singing, a minority of actresses are known to have performed speaking roles, and there were actresses who achieved wealth, fame and recognition for their art, such as Eucharis, Dionysia, Galeria Copiola and Fabia Arete: they also formed their own acting guild, the Sociae Mimae, which was evidently quite wealthy.[56]

Indian theatre

[edit]

The first form of Indian theatre was the Sanskrit theatre,[57] earliest-surviving fragments of which date from the 1st century CE.[58][59] It began after the development of Greek and Roman theatre and before the development of theatre in other parts of Asia.[57] It emerged sometime between the 2nd century BCE and the 1st century CE and flourished between the 1st century CE and the 10th, which was a period of relative peace in the history of India during which hundreds of plays were written.[60][61] The wealth of archeological evidence from earlier periods offers no indication of the existence of a tradition of theatre.[61] The ancient Vedas (hymns from between 1500 and 1000 BCE that are among the earliest examples of literature in the world) contain no hint of it (although a small number are composed in a form of dialogue) and the rituals of the Vedic period do not appear to have developed into theatre.[61] The Mahābhāṣya by Patañjali contains the earliest reference to what may have been the seeds of Sanskrit drama.[62] This treatise on grammar from 140 BCE provides a feasible date for the beginnings of theatre in India.[62]

The major source of evidence for Sanskrit theatre is A Treatise on Theatre (Nātyaśāstra), a compendium whose date of composition is uncertain (estimates range from 200 BCE to 200 CE) and whose authorship is attributed to Bharata Muni. The Treatise is the most complete work of dramaturgy in the ancient world. It addresses acting, dance, music, dramatic construction, architecture, costuming, make-up, props, the organisation of companies, the audience, competitions, and offers a mythological account of the origin of theatre.[62] In doing so, it provides indications about the nature of actual theatrical practices. Sanskrit theatre was performed on sacred ground by priests who had been trained in the necessary skills (dance, music, and recitation) in a [hereditary process]. Its aim was both to educate and to entertain.

Under the patronage of royal courts, performers belonged to professional companies that were directed by a stage manager (sutradhara), who may also have acted.[58][62] This task was thought of as being analogous to that of a puppeteer—the literal meaning of "sutradhara" is "holder of the strings or threads".[62] The performers were trained rigorously in vocal and physical technique.[63] There were no prohibitions against female performers; companies were all-male, all-female, and of mixed gender. Certain sentiments were considered inappropriate for men to enact, however, and were thought better suited to women. Some performers played characters their own age, while others played ages different from their own (whether younger or older). Of all the elements of theatre, the Treatise gives most attention to acting (abhinaya), which consists of two styles: realistic (lokadharmi) and conventional (natyadharmi), though the major focus is on the latter.[63][n]

Its drama is regarded as the highest achievement of Sanskrit literature.[58] It utilised stock characters, such as the hero (nayaka), heroine (nayika), or clown (vidusaka). Actors may have specialized in a particular type. Kālidāsa in the 1st century BCE, is arguably considered to be ancient India's greatest Sanskrit dramatist. Three famous romantic plays written by Kālidāsa are the Mālavikāgnimitram (Mālavikā and Agnimitra), Vikramuurvashiiya (Pertaining to Vikrama and Urvashi), and Abhijñānaśākuntala (The Recognition of Shakuntala). The last was inspired by a story in the Mahabharata and is the most famous. It was the first to be translated into English and German. Śakuntalā (in English translation) influenced Goethe's Faust (1808–1832).[58]

The next great Indian dramatist was Bhavabhuti (c. 7th century CE). He is said to have written the following three plays: Malati-Madhava, Mahaviracharita and Uttar Ramacharita. Among these three, the last two cover between them the entire epic of Ramayana. The powerful Indian emperor Harsha (606–648) is credited with having written three plays: the comedy Ratnavali, Priyadarsika, and the Buddhist drama Nagananda.

East Asian theatre

[edit]

The Tang dynasty is sometimes known as "The Age of 1000 Entertainments". During this era, Ming Huang formed an acting school known as The Pear Garden to produce a form of drama that was primarily musical. That is why actors are commonly called "Children of the Pear Garden". During the dynasty of Empress Ling, shadow puppetry first emerged as a recognized form of theatre in China. There were two distinct forms of shadow puppetry, Pekingese (northern) and Cantonese (southern). The two styles were differentiated by the method of making the puppets and the positioning of the rods on the puppets, as opposed to the type of play performed by the puppets. Both styles generally performed plays depicting great adventure and fantasy, rarely was this very stylized form of theatre used for political propaganda.

Japanese forms of Kabuki, Nō, and Kyōgen developed in the 17th century CE.[64]

Cantonese shadow puppets were the larger of the two. They were built using thick leather which created more substantial shadows. Symbolic colour was also very prevalent; a black face represented honesty, a red one bravery. The rods used to control Cantonese puppets were attached perpendicular to the puppets' heads. Thus, they were not seen by the audience when the shadow was created. Pekingese puppets were more delicate and smaller. They were created out of thin, translucent leather (usually taken from the belly of a donkey). They were painted with vibrant paints, thus they cast a very colourful shadow. The thin rods which controlled their movements were attached to a leather collar at the neck of the puppet. The rods ran parallel to the bodies of the puppet and then turned at a ninety degree angle to connect to the neck. While these rods were visible when the shadow was cast, they laid outside the shadow of the puppet; thus they did not interfere with the appearance of the figure. The rods are attached at the necks to facilitate the use of multiple heads with one body. When the heads were not being used, they were stored in a muslin book or fabric-lined box. The heads were always removed at night. This was in keeping with the old superstition that if left intact, the puppets would come to life at night. Some puppeteers went so far as to store the heads in one book and the bodies in another, to further reduce the possibility of reanimating puppets. Shadow puppetry is said to have reached its highest point of artistic development in the eleventh century before becoming a tool of the government.

In the Song dynasty, there were many popular plays involving acrobatics and music. These developed in the Yuan dynasty into a more sophisticated form known as zaju, with a four- or five-act structure. Yuan drama spread across China and diversified into numerous regional forms, one of the best known of which is Peking Opera which is still popular today.

Xiangsheng is a certain traditional Chinese comedic performance in the forms of monologue or dialogue.

Indonesian theatre

[edit]

In Indonesia, theatre performances have become an important part of local culture, theatre performances in Indonesia have been developed for thousands of years. Most of Indonesia's oldest theatre forms are linked directly to local literary traditions (oral and written). The prominent puppet theatres—wayang golek (wooden rod-puppet play) of the Sundanese and wayang kulit (leather shadow-puppet play) of the Javanese and Balinese—draw much of their repertoire from indigenized versions of the Ramayana and Mahabharata. These tales also provide source material for the wayang wong (human theatre) of Java and Bali, which uses actors. Some wayang golek performances, however, also present Muslim stories, called menak.[65][66] Wayang is an ancient form of storytelling that renowned for its elaborate puppet/human and complex musical styles.[67] The earliest evidence is from the late 1st millennium CE, in medieval-era texts and archeological sites.[68] The oldest known record that concerns wayang is from the 9th century. Around 840 AD an Old Javanese (Kawi) inscriptions called Jaha Inscriptions issued by Maharaja Sri Lokapala from Mataram Kingdom in Central Java mentions three sorts of performers: atapukan, aringgit, and abanol. Aringgit means Wayang puppet show, Atapukan means Mask dance show, and abanwal means joke art. Ringgit is described in an 11th-century Javanese poem as a leather shadow figure.

Medieval Islamic traditions

[edit]Theatre in the medieval Islamic world included puppet theatre (which included hand puppets, shadow plays and marionette productions) and live passion plays known as ta'ziyeh, where actors re-enact episodes from Muslim history. In particular, Shia Islamic plays revolved around the istishhād (martyrdom) of Ali's sons Hasan ibn Ali and Husayn ibn Ali. Secular plays were known as akhraja, recorded in medieval adab literature, though they were less common than puppetry and ta'ziya theatre.[69]

Early modern and modern theatre in the West

[edit]

Theatre took on many alternative forms in the West between the 15th and 19th centuries, including commedia dell'arte from Italian theatre, and melodrama. The general trend was away from the poetic drama of the Greeks and the Renaissance and toward a more naturalistic prose style of dialogue, especially following the Industrial Revolution.[70]

Theatre took a big pause during 1642 and 1660 in England because of the Puritan Interregnum.[71] The rising anti-theatrical sentiment among Puritans saw William Prynne write Histriomastix (1633), the most notorious attack on theatre prior to the ban.[71] Viewing theatre as sinful, the Puritans ordered the closure of London theatres in 1642.[72] On 24 January 1643, the actors protested against the ban by writing a pamphlet titled The Actors remonstrance or complaint for the silencing of their profession, and banishment from their severall play-houses.[73] This stagnant period ended once Charles II came back to the throne in 1660 in the Restoration. Theatre (among other arts) exploded, with influence from French culture, since Charles had been exiled in France in the years previous to his reign.

In 1660, two companies were licensed to perform, the Duke's Company and the King's Company. Performances were held in converted buildings, such as Lisle's Tennis Court. The first West End theatre, known as Theatre Royal in Covent Garden, London, was designed by Thomas Killigrew and built on the site of the present Theatre Royal, Drury Lane.[74]

One of the big changes was the new theatre house. Instead of the type of the Elizabethan era, such as the Globe Theatre, round with no place for the actors to prepare for the next act and with no "theatre manners", the theatre house became transformed into a place of refinement, with a stage in front and stadium seating facing it. Since seating was no longer all the way around the stage, it became prioritized—some seats were obviously better than others. The king would have the best seat in the house: the very middle of the theatre, which got the widest view of the stage as well as the best way to see the point of view and vanishing point that the stage was constructed around. Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg was one of the most influential set designers of the time because of his use of floor space and scenery.

Because of the turmoil before this time, there was still some controversy about what should and should not be put on the stage. Jeremy Collier, a preacher, was one of the heads in this movement through his piece A Short View of the Immorality and Profaneness of the English Stage. The beliefs in this paper were mainly held by non-theatre goers and the remainder of the Puritans and very religious of the time. The main question was if seeing something immoral on stage affects behaviour in the lives of those who watch it, a controversy that is still playing out today.[75]

The seventeenth century had also introduced women to the stage, which was considered inappropriate earlier. These women were regarded as celebrities (also a newer concept, thanks to ideas on individualism that arose in the wake of Renaissance Humanism), but on the other hand, it was still very new and revolutionary that they were on the stage, and some said they were unladylike, and looked down on them. Charles II did not like young men playing the parts of young women, so he asked that women play their own parts.[76] Because women were allowed on the stage, playwrights had more leeway with plot twists, like women dressing as men, and having narrow escapes from morally sticky situations as forms of comedy.

Comedies were full of the young and very much in vogue, with the storyline following their love lives: commonly a young roguish hero professing his love to the chaste and free minded heroine near the end of the play, much like Sheridan's The School for Scandal. Many of the comedies were fashioned after the French tradition, mainly Molière, again hailing back to the French influence brought back by the King and the Royals after their exile. Molière was one of the top comedic playwrights of the time, revolutionizing the way comedy was written and performed by combining Italian commedia dell'arte and neoclassical French comedy to create some of the longest lasting and most influential satiric comedies.[77] Tragedies were similarly victorious in their sense of righting political power, especially poignant because of the recent Restoration of the Crown.[78] They were also imitations of French tragedy, although the French had a larger distinction between comedy and tragedy, whereas the English fudged the lines occasionally and put some comedic parts in their tragedies. Common forms of non-comedic plays were sentimental comedies as well as something that would later be called tragédie bourgeoise, or domestic tragedy—that is, the tragedy of common life—were more popular in England because they appealed more to English sensibilities.[79]

While theatre troupes were formerly often travelling, the idea of the national theatre gained support in the 18th century, inspired by Ludvig Holberg. The major promoter of the idea of the national theatre in Germany, and also of the Sturm und Drang poets, was Abel Seyler, the owner of the Hamburgische Entreprise and the Seyler Theatre Company.[80]

Through the 19th century, the popular theatrical forms of Romanticism, melodrama, Victorian burlesque and the well-made plays of Scribe and Sardou gave way to the problem plays of Naturalism and Realism; the farces of Feydeau; Wagner's operatic Gesamtkunstwerk; musical theatre (including Gilbert and Sullivan's operas); F. C. Burnand's, W. S. Gilbert's and Oscar Wilde's drawing-room comedies; Symbolism; proto-Expressionism in the late works of August Strindberg and Henrik Ibsen;[82] and Edwardian musical comedy.

These trends continued through the 20th century in the realism of Stanislavski and Lee Strasberg, the political theatre of Erwin Piscator and Bertolt Brecht, the so-called Theatre of the Absurd of Samuel Beckett and Eugène Ionesco, American and British musicals, the collective creations of companies of actors and directors such as Joan Littlewood's Theatre Workshop, experimental and postmodern theatre of Robert Wilson and Robert Lepage, the postcolonial theatre of August Wilson or Tomson Highway, and Augusto Boal's Theatre of the Oppressed.

Types

[edit]Drama

[edit]

Drama is the specific mode of fiction represented in performance.[83] The term comes from a Greek word meaning "action", which is derived from the verb δράω, dráō, "to do" or "to act". The enactment of drama in theatre, performed by actors on a stage before an audience, presupposes collaborative modes of production and a collective form of reception. The structure of dramatic texts, unlike other forms of literature, is directly influenced by this collaborative production and collective reception.[84] The early modern tragedy Hamlet (1601) by Shakespeare and the classical Athenian tragedy Oedipus Rex (c. 429 BCE) by Sophocles are among the masterpieces of the art of drama.[85] A modern example is Long Day's Journey into Night by Eugene O'Neill (1956).[86]

Considered as a genre of poetry in general, the dramatic mode has been contrasted with the epic and the lyrical modes ever since Aristotle's Poetics (c. 335 BCE); the earliest work of dramatic theory.[o] The use of "drama" in the narrow sense to designate a specific type of play dates from the 19th century. Drama in this sense refers to a play that is neither a comedy nor a tragedy—for example, Zola's Thérèse Raquin (1873) or Chekhov's Ivanov (1887). In Ancient Greece however, the word drama encompassed all theatrical plays, tragic, comic, or anything in between.

Drama is often combined with music and dance: the drama in opera is generally sung throughout; musicals generally include both spoken dialogue and songs; and some forms of drama have incidental music or musical accompaniment underscoring the dialogue (melodrama and Japanese Nō, for example).[p] In certain periods of history (the ancient Roman and modern Romantic) some dramas have been written to be read rather than performed.[q] In improvisation, the drama does not pre-exist the moment of performance; performers devise a dramatic script spontaneously before an audience.[r]

Musical theatre

[edit]

Music and theatre have had a close relationship since ancient times—Athenian tragedy, for example, was a form of dance-drama that employed a chorus whose parts were sung (to the accompaniment of an aulos—an instrument comparable to the modern oboe), as were some of the actors' responses and their 'solo songs' (monodies).[87] Modern musical theatre is a form of theatre that also combines music, spoken dialogue, and dance. It emerged from comic opera (especially Gilbert and Sullivan), variety, vaudeville, and music hall genres of the late 19th and early 20th century.[88] After the Edwardian musical comedy that began in the 1890s, the Princess Theatre musicals of the early 20th century, and comedies in the 1920s and 1930s (such as the works of Rodgers and Hammerstein), with Oklahoma! (1943), musicals moved in a more dramatic direction.[s] Famous musicals over the subsequent decades included My Fair Lady (1956), West Side Story (1957), The Fantasticks (1960), Hair (1967), A Chorus Line (1975), Les Misérables (1980), Cats (1981), Into the Woods (1986), and The Phantom of the Opera (1986),[89] as well as more contemporary hits including Rent (1994), The Lion King (1997), Wicked (2003), Hamilton (2015) and Frozen (2018).

Musical theatre may be produced on an intimate scale Off-Broadway, in regional theatres, and elsewhere, but it often includes spectacle. For instance, Broadway and West End musicals often include lavish costumes and sets supported by multimillion-dollar budgets.

Comedy

[edit]

Theatre productions that use humour as a vehicle to tell a story qualify as comedies. This may include a modern farce such as Boeing Boeing or a classical play such as As You Like It. Theatre expressing bleak, controversial or taboo subject matter in a deliberately humorous way is referred to as black comedy. Black Comedy can have several genres like slapstick humour, dark and sarcastic comedy.

Tragedy

[edit]Tragedy, then, is an imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude: in language embellished with each kind of artistic ornament, the several kinds being found in separate parts of the play; in the form of action, not of narrative; through pity and fear effecting the proper purgation of these emotions.

Aristotle's phrase "several kinds being found in separate parts of the play" is a reference to the structural origins of drama. In it the spoken parts were written in the Attic dialect whereas the choral (recited or sung) ones in the Doric dialect, these discrepancies reflecting the differing religious origins and poetic metres of the parts that were fused into a new entity, the theatrical drama.

Tragedy refers to a specific tradition of drama that has played a unique and important role historically in the self-definition of Western civilisation.[91][92] That tradition has been multiple and discontinuous, yet the term has often been used to invoke a powerful effect of cultural identity and historical continuity—"the Greeks and the Elizabethans, in one cultural form; Hellenes and Christians, in a common activity", as Raymond Williams puts it.[93] From its obscure origins in the theatres of Athens 2,500 years ago, from which there survives only a fraction of the work of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, through its singular articulations in the works of Shakespeare, Lope de Vega, Racine, and Schiller, to the more recent naturalistic tragedy of Strindberg, Beckett's modernist meditations on death, loss and suffering, and Müller's postmodernist reworkings of the tragic canon, tragedy has remained an important site of cultural experimentation, negotiation, struggle, and change.[94][95] In the wake of Aristotle's Poetics (335 BCE), tragedy has been used to make genre distinctions, whether at the scale of poetry in general (where the tragic divides against epic and lyric) or at the scale of the drama (where tragedy is opposed to comedy). In the modern era, tragedy has also been defined against drama, melodrama, the tragicomic, and epic theatre.[t]

Improvisation

[edit]

Improvisation has been a consistent feature of theatre, with the Commedia dell'arte in the sixteenth century being recognized as the first improvisation form. Popularized by 1997 Nobel Prize in Literature winner Dario Fo and troupes such as the Upright Citizens Brigade improvisational theatre continues to evolve with many different streams and philosophies.

Keith Johnstone and Viola Spolin are recognized as the first teachers of improvisation in modern times, with Johnstone exploring improvisation as an alternative to scripted theatre and Spolin and her successors exploring improvisation principally as a tool for developing dramatic work or skills or as a form for situational comedy. Spolin also became interested in how the process of learning improvisation was applicable to the development of human potential.[99]

Spolin's son, Paul Sills popularized improvisational theatre as a theatrical art form when he founded, as its first director, The Second City in Chicago.

Theories

[edit]

Having been an important part of human culture for more than 2,500 years, theatre has evolved a wide range of different theories and practices. Some are related to political or spiritual ideologies, while others are based purely on "artistic" concerns. Some processes focus on a story, some on theatre as event, and some on theatre as catalyst for social change. The classical Greek philosopher Aristotle, in his seminal treatise, Poetics (c. 335 BCE) is the earliest-surviving example and its arguments have influenced theories of theatre ever since.[17][18] In it, he offers an account of what he calls "poetry" (a term which in Greek literally means "making" and in this context includes drama—comedy, tragedy, and the satyr play—as well as lyric poetry, epic poetry, and the dithyramb). He examines its "first principles" and identifies its genres and basic elements; his analysis of tragedy constitutes the core of the discussion.[100]

Aristotle argues that tragedy consists of six qualitative parts, which are (in order of importance) mythos or "plot", ethos or "character", dianoia or "thought", lexis or "diction", melos or "song", and opsis or "spectacle".[101][102] "Although Aristotle's Poetics is universally acknowledged in the Western critical tradition", Marvin Carlson explains, "almost every detail about his seminal work has aroused divergent opinions."[103] Important theatre practitioners of the 20th century include Konstantin Stanislavski, Vsevolod Meyerhold, Jacques Copeau, Edward Gordon Craig, Bertolt Brecht, Antonin Artaud, Joan Littlewood, Peter Brook, Jerzy Grotowski, Augusto Boal, Eugenio Barba, Dario Fo, Viola Spolin, Keith Johnstone and Robert Wilson (director).

Stanislavski treated the theatre as an art-form that is autonomous from literature and one in which the playwright's contribution should be respected as that of only one of an ensemble of creative artists.[104][105][106][107][u] His innovative contribution to modern acting theory has remained at the core of mainstream western performance training for much of the last century.[108][109][110][111][112] That many of the precepts of his system of actor training seem to be common sense and self-evident testifies to its hegemonic success.[113] Actors frequently employ his basic concepts without knowing they do so.[113] Thanks to its promotion and elaboration by acting teachers who were former students and the many translations of his theoretical writings, Stanislavski's 'system' acquired an unprecedented ability to cross cultural boundaries and developed an international reach, dominating debates about acting in Europe and the United States.[108][114][115][116] Many actors routinely equate his 'system' with the North American Method, although the latter's exclusively psychological techniques contrast sharply with Stanislavski's multivariant, holistic and psychophysical approach, which explores character and action both from the 'inside out' and the 'outside in' and treats the actor's mind and body as parts of a continuum.[117][118]

Technical aspects

[edit]

Theatre presupposes collaborative modes of production and a collective form of reception. The structure of dramatic texts, unlike other forms of literature, is directly influenced by this collaborative production and collective reception.[84] The production of plays usually involves contributions from a playwright, director, a cast of actors, and a technical production team that includes a scenic or set designer, lighting designer, costume designer, sound designer, stage manager, production manager and technical director. Depending on the production, this team may also include a composer, dramaturg, video designer or fight director.

Stagecraft is a generic term referring to the technical aspects of theatrical, film, and video production. It includes, but is not limited to, constructing and rigging scenery, hanging and focusing of lighting, design and procurement of costumes, makeup, procurement of props, stage management, and recording and mixing of sound. Stagecraft is distinct from the wider umbrella term of scenography. Considered a technical rather than an artistic field, it relates primarily to the practical implementation of a designer's artistic vision.

In its most basic form, stagecraft is managed by a single person (often the stage manager of a smaller production) who arranges all scenery, costumes, lighting, and sound, and organizes the cast. At a more professional level, for example in modern Broadway houses, stagecraft is managed by hundreds of skilled carpenters, painters, electricians, stagehands, stitchers, wigmakers, and the like. This modern form of stagecraft is highly technical and specialized: it comprises many subdisciplines and a vast trove of history and tradition. The majority of stagecraft lies between these two extremes. Regional theatres and larger community theatres will generally have a technical director and a complement of designers, each of whom has a direct hand in their respective designs.

Subcategories and organisation

[edit]There are many modern theatre movements which produce theatre in a variety of ways. Theatrical enterprises vary enormously in sophistication and purpose. People who are involved vary from novices and hobbyists (in community theatre) to professionals (in Broadway and similar productions). Theatre can be performed with a shoestring budget or on a grand scale with multimillion-dollar budgets. This diversity manifests in the abundance of theatre subcategories, which include:

- Broadway theatre and West End theatre

- Community theatre

- Dinner theater

- Fringe theatre

- Immersive theater

- Interactive theatre

- Off-Broadway and Off West End

- Off-off-Broadway

- Playback theatre

- Regional theatre in the United States

- Site-specific theatre

- Street theatre

- Summer stock theatre

- Theatre and disability

- Touring theatre

Repertory companies

[edit]

While most modern theatre companies rehearse one piece of theatre at a time, perform that piece for a set "run", retire the piece, and begin rehearsing a new show, repertory companies rehearse multiple shows at one time. These companies are able to perform these various pieces upon request and often perform works for years before retiring them. Most dance companies operate on this repertory system. The Royal National Theatre in London performs on a repertory system.

Repertory theatre generally involves a group of similarly accomplished actors, and relies more on the reputation of the group than on an individual star actor. It also typically relies less on strict control by a director and less on adherence to theatrical conventions, since actors who have worked together in multiple productions can respond to each other without relying as much on convention or external direction.[119]

Other terminology

[edit]

A theatre company is an organisation that produces theatrical performances,[3] as distinct from a theatre troupe (or acting company), which is a group of theatrical performers working together.[4]

A touring company is an independent theatre or dance company that travels, often internationally, being presented at a different theatre venue in each city.[citation needed]

In order to put on a piece of theatre, both a theatre company and a theatre venue are needed. When a theatre company is the sole company in residence at a theatre venue, this theatre (and its corresponding theatre company) are called a resident theatre or a producing theatre, because the venue produces its own work. Other theatre companies, as well as dance companies, who do not have their own theatre venue, perform at rental theatres or at presenting theatres. Both rental and presenting theatres have no full-time resident companies. They do, however, sometimes have one or more part-time resident companies, in addition to other independent partner companies who arrange to use the space when available. A rental theatre allows the independent companies to seek out the space, while a presenting theatre seeks out the independent companies to support their work by presenting them on their stage.[citation needed]

Some performance groups perform in non-theatrical spaces. Such performances can take place outside or inside, in a non-traditional performance space, and include street theatre, and site-specific theatre. Non-traditional venues can be used to create more immersive or meaningful environments for audiences. They can sometimes be modified more heavily than traditional theatre venues, or can accommodate different kinds of equipment, lighting and sets.[121]

Unions

[edit]There are many theatre unions, including:

- Actors' Equity Association (AEA), for actors and stage managers in the U.S.)[122]

- Canadian Actors' Equity Association, for actors in Canada

- Equity, for many kind of performing artists as well as designers, directors, and stage managers in the UK[123]

- International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE), for designers and technicians).[122]

- Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance, an Australian union created in 1992 as a merger of the unions covering actors, journalists and entertainment industry employees[124]

- Stage Directors and Choreographers Society (SDC)[122]

See also

[edit]- Acting

- Antitheatricality

- Black light theatre

- Culinary theatre

- Illusionistic tradition

- List of awards in theatre

- List of playwrights

- List of theatre personnel

- List of theatre festivals

- List of theatre directors

- Lists of theatres

- Performance art

- Puppetry

- Reader's theatre

- Site-specific theatre

- Theatre consultant

- Theatre for development

- Theater (structure)

- Theatre technique

- Theatrical style

- Theatrical troupe

- World Theatre Day

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Originally spelled theatre and teatre. (c. 1380), from around 1550 to 1700 or later, the most common spelling was theater. Between 1720 and 1750, theater was dropped in British English, but was either retained or revived in American English (Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition, 2009, CD-ROM: ISBN 9780199563838). Recent dictionaries of American English list theatre as a less common variant, e.g., Random House Webster's College Dictionary (1991); The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th edition (2006); New Oxford American Dictionary, third edition (2010); Merriam-Webster Dictionary (2011) Archived 18 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Drawing on the "semiotics" of Charles Sanders Peirce, Pavis goes on to suggest that "the specificity of theatrical signs may lie in their ability to use the three possible functions of signs: as icon (mimetically), as index (in the situation of enunciation), or as symbol (as a semiological system in the fictional mode). In effect, theatre makes the sources of the words visual and concrete: it indicates and incarnates a fictional world by means of signs, such that by the end of the process of signification and symbolization the spectator has reconstructed a theoretical and aesthetic model that accounts for the dramatic universe."[2]

- ^ Brown writes that ancient Greek drama "was essentially the creation of classical Athens: all the dramatists who were later regarded as classics were active at Athens in the 5th and 4th centuries BCE (the time of the Athenian democracy), and all the surviving plays date from this period".[7] "The dominant culture of Athens in the fifth century", Goldhill writes, "can be said to have invented theatre".[9]

- ^ Goldhill argues that although activities that form "an integral part of the exercise of citizenship" (such as when "the Athenian citizen speaks in the Assembly, exercises in the gymnasium, sings at the symposium, or courts a boy") each have their "own regime of display and regulation", nevertheless the term "performance" provides "a useful heuristic category to explore the connections and overlaps between these different areas of activity".[13]

- ^ Taxidou notes that "most scholars now call 'Greek' tragedy 'Athenian' tragedy, which is historically correct".[25]

- ^ Cartledge writes that although Athenians of the 4th century judged Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides "as the nonpareils of the genre, and regularly honoured their plays with revivals, tragedy itself was not merely a 5th-century phenomenon, the product of a short-lived golden age. If not attaining the quality and stature of the fifth-century 'classics', original tragedies nonetheless continued to be written and produced and competed with in large numbers throughout the remaining life of the democracy—and beyond it".[28]

- ^ We have seven by Aeschylus, seven by Sophocles, and eighteen by Euripides. In addition, we also have the Cyclops, a satyr play by Euripides. Some critics since the 17th century have argued that one of the tragedies that the classical tradition gives as Euripides'—Rhesus—is a 4th-century play by an unknown author; modern scholarship agrees with the classical authorities and ascribes the play to Euripides; see Walton (1997, viii, xix). (This uncertainty accounts for Brockett and Hildy's figure of 31 tragedies.)

- ^ The theory that Prometheus Bound was not written by Aeschylus adds a fourth, anonymous playwright to those whose work survives.

- ^ Exceptions to this pattern were made, as with Euripides' Alcestis in 438 BCE. There were also separate competitions at the City Dionysia for the performance of dithyrambs and, after 488–87 BCE, comedies.

- ^ Rush Rehm offers the following argument as evidence that tragedy was not institutionalised until 501 BCE: "The specific cult honoured at the City Dionysia was that of Dionysus Eleuthereus, the god 'having to do with Eleutherae', a town on the border between Boeotia and Attica that had a sanctuary to Dionysus. At some point Athens annexed Eleutherae—most likely after the overthrow of the Peisistratid tyranny in 510 and the democratic reforms of Cleisthenes in 508–07 BCE—and the cult-image of Dionysus Eleuthereus was moved to its new home. Athenians re-enacted the incorporation of the god's cult every year in a preliminary rite to the City Dionysia. On the day before the festival proper, the cult-statue was removed from the temple near the theatre of Dionysus and taken to a temple on the road to Eleutherae. That evening, after sacrifice and hymns, a torchlight procession carried the statue back to the temple, a symbolic re-creation of the god's arrival into Athens, as well as a reminder of the inclusion of the Boeotian town into Attica. As the name Eleutherae is extremely close to eleutheria, 'freedom', Athenians probably felt that the new cult was particularly appropriate for celebrating their own political liberation and democratic reforms."[37]

- ^ Jean-Pierre Vernant argues that in The Persians Aeschylus substitutes for the usual temporal distance between the audience and the age of heroes a spatial distance between the Western audience and the Eastern Persian culture. This substitution, he suggests, produces a similar effect: "The 'historic' events evoked by the chorus, recounted by the messenger and interpreted by Darius' ghost are presented on stage in a legendary atmosphere. The light that the tragedy sheds upon them is not that in which the political happenings of the day are normally seen; it reaches the Athenian theatre refracted from a distant world of elsewhere, making what is absent seem present and visible on the stage"; Vernant and Vidal-Naquet (1988, 245).

- ^ Aristotle, Poetics, line 1449a: "Comedy, as we have said, is a representation of inferior people, not indeed in the full sense of the word bad, but the laughable is a species of the base or ugly. It consists in some blunder or ugliness that does not cause pain or disaster, an obvious example being the comic mask which is ugly and distorted but not painful'."

- ^ For more information on the ancient Roman dramatists, see the articles categorised under "Ancient Roman dramatists and playwrights" in Wikipedia.

- ^ The literal meaning of abhinaya is "to carry forwards".

- ^ Francis Fergusson writes that "a drama, as distinguished from a lyric, is not primarily a composition in the verbal medium; the words result, as one might put it, from the underlying structure of incident and character. As Aristotle remarks, 'the poet, or "maker" should be the maker of plots rather than of verses; since he is a poet because he imiates, and what he imitates are actions'" (1949, 8).

- ^ See the entries for "opera", "musical theatre, American", "melodrama" and "Nō" in Banham 1998

- ^ While there is some dispute among theatre historians, it is probable that the plays by the Roman Seneca were not intended to be performed. Manfred by Byron is a good example of a "dramatic poem". See the entries on "Seneca" and "Byron (George George)" in Banham 1998.

- ^ Some forms of improvisation, notably the Commedia dell'arte, improvise on the basis of 'lazzi' or rough outlines of scenic action (see Gordon 1983 and Duchartre 1966). All forms of improvisation take their cue from their immediate response to one another, their characters' situations (which are sometimes established in advance), and, often, their interaction with the audience. The classic formulations of improvisation in the theatre originated with Joan Littlewood and Keith Johnstone in the UK and Viola Spolin in the US; see Johnstone 2007 and Spolin 1999.

- ^ The first "Edwardian musical comedy" is usually considered to be In Town (1892), even though it was produced eight years before the beginning of the Edwardian era; see, for example, Fraser Charlton, "What are EdMusComs?" (FrasrWeb 2007, accessed May 12, 2011).

- ^ See Carlson 1993, Pfister 2000, Elam 1980, and Taxidou 2004. Drama, in the narrow sense, cuts across the traditional division between comedy and tragedy in an anti- or a-generic deterritorialization from the mid-19th century onwards. Both Bertolt Brecht and Augusto Boal define their epic theatre projects (Non-Aristotelian drama and Theatre of the Oppressed respectively) against models of tragedy. Taxidou, however, reads epic theatre as an incorporation of tragic functions and its treatments of mourning and speculation.[95]

- ^ In 1902, Stanislavski wrote that "the author writes on paper. The actor writes with his body on the stage" and that the "score of an opera is not the opera itself and the script of a play is not drama until both are made flesh and blood on stage"; quoted by Benedetti (1999a, 124).

Citations

[edit]- ^ Carlson 1986, p. 36.

- ^ a b Pavis 1998, pp. 345–346.

- ^ a b "Theatre company definition and meaning". Collins English Dictionary. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ a b "Definition of Troupe". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ "Troupe definition and meaning". Collins English Dictionary. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ Davidson (2005, 197) and Taplin (2003, 10).

- ^ a b c Brown 1998, p. 441.

- ^ a b c Cartledge 1997, pp. 3–5.

- ^ a b c d Goldhill 1997, p. 54.

- ^ Cartledge 1997, pp. 3, 6.

- ^ Goldhill 2004, pp. 20–xx.

- ^ Rehm 1992, p. 3.

- ^ Goldhill 2004, p. 1.

- ^ Pelling 2005, p. 83.

- ^ Goldhill 2004, p. 25.

- ^ Pelling 2005, pp. 83–84.

- ^ a b Dukore 1974, p. 31.

- ^ a b Janko 1987, p. ix.

- ^ Ward 2007, p. 1.

- ^ "Introduction to Theatre – Ancient Greek Theatre". novaonline.nvcc.edu.

- ^ Brockett & Hildy 2003, pp. 15–19.

- ^ "Theatre | Chambers Dictionary of World History – Credo Reference". search.credoreference.com.

- ^ Ley 2007, p. 206.

- ^ Styan 2000, p. 140.

- ^ Taxidou 2004, p. 104.

- ^ Brockett & Hildy 2003, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Brown 1998, p. 444.

- ^ Cartledge 1997, p. 33.

- ^ Brockett & Hildy 2003, p. 5.

- ^ Kovacs 2005, p. 379.

- ^ Brockett & Hildy 2003, p. 15.

- ^ Brockett & Hildy 2003, pp. 13–15.

- ^ Brown 1998, pp. 441–447.

- ^ a b c d Brown 1998, p. 442.

- ^ Brockett & Hildy 2003, pp. 15–17.

- ^ Brockett & Hildy 2003, pp. 13, 15.

- ^ Rehm 1992, p. 15.

- ^ Brockett & Hildy 2003, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Webster 1967.

- ^ "Storia del Teatro nelle città d'Italia" (in Italian). Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ "Il teatro" (in Italian). Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ "Aristotele - Origini della commedia" (in Italian). Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ "Rintóne" (in Italian). Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ Beacham, Richard C. 1996. The Roman Theatre and Its Audience. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP. ISBN 978-0-674-77914-3, p. 2).

- ^ Beacham (1996, 3).

- ^ a b Brockett and Hildy (1968; 10th ed. 2010), History of the Theater, p. 43).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 36, 47).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 46–47).

- ^ a b c Brockett and Hildy (2003, 47).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 47–48).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 48–49).

- ^ a b c Brockett and Hildy (2003, 49).

- ^ a b Brockett and Hildy (2003, 48).

- ^ a b Brockett and Hildy (2003, 50).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 49–50).

- ^ Ruth Webb, 'Female entertainers in late antiquity', in Pat Easterling and Edith Hall, eds., Greek and Roman Actors: Aspects of an Ancient Profession Archived 2020-05-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Richmond, Swann & Zarrilli 1993, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d Brandon 1993, p. xvii.

- ^ Brandon 1997, pp. 516–517.

- ^ Brandon 1997, p. 70.

- ^ a b c Richmond 1998, p. 516.

- ^ a b c d e Richmond 1998, p. 517.

- ^ a b Richmond 1998, p. 518.

- ^ Deal 2007, p. 276.

- ^ Don Rubin; Chua Soo Pong; Ravi Chaturvedi; et al. (2001). The World Encyclopedia of Contemporary Theatre: Asia/Pacific. Taylor & Francis. pp. 184–186. ISBN 978-0-415-26087-9.

- ^ "Pengetahuan Teater" (PDF). Kemdikbud. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 3, 2021.

- ^ ""Wayang puppet theatre", Inscribed in 2008 (3.COM) on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity (originally proclaimed in 2003)". UNESCO. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- ^ James R. Brandon (2009). Theatre in Southeast Asia. Harvard University Press. pp. 143–145, 352–353. ISBN 978-0-674-02874-6.

- ^ Moreh 1986, pp. 565–601.

- ^ Kuritz 1988, p. 305.

- ^ a b Beushausen, Katrin (2018). "From Audience to Public: Theatre, Theatricality and the People before the Civil Wars". Theatre, Theatricality and the People before the Civil Wars. Cambridge University Press. pp. 80–112. doi:10.1017/9781316850411.004. ISBN 9781107181458.

- ^ "From pandemics to puritans: when theatre shut down through history and how it recovered". The Stage. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ The Actors remonstrance or complaint for the silencing for their profession, and banishment from their severall play-houses. January 24, 1643 – via Early English Books Online – University of Michigan Library.

- ^ a b "London's 10 oldest theatres". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- ^ Robinson, Scott R. "The English Theatre, 1642–1800". Scott R. Robinson Home. CWU Department of Theatre Arts. Archived from the original on May 2, 2012. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- ^ "Women's Lives Surrounding Late 18th Century Theatre". English 3621 Writing by Women. Archived from the original on April 22, 2013. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ Bermel, Albert. "Moliere – French Dramatist". Discover France. Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ Black 2010, pp. 533–535.

- ^ Matthew, Brander. "The Drama in the 18th Century". Moonstruch Drama Bookstore. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ Wilhelm Kosch, "Seyler, Abel", in Dictionary of German Biography, eds. Walther Killy and Rudolf Vierhaus, Vol. 9, Walter de Gruyter editor, 2005, ISBN 3-11-096629-8, p. 308.

- ^ "7028 end. Tartu Saksa Teatrihoone Vanemuise 45a, 1914–1918.a." Kultuurimälestiste register (in Estonian). Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- ^ Brockett & Hildy 2003, pp. 293–426.

- ^ Elam 1980, p. 98.

- ^ a b Pfister 2000, p. 11.

- ^ Fergusson 1968, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Burt 2008, pp. 30–35.

- ^ Rehm 1992, 150n7.

- ^ Jones 2003, pp. 4–11.

- ^ Kenrick, John (2003). "History of Stage Musicals". Retrieved May 26, 2009.

- ^ S. H. Butcher, [1], 2011[dead link]

- ^ Banham 1998, p. 1118.

- ^ Williams 1966, pp. 14–16.

- ^ Williams 1966, p. 16.

- ^ Williams 1966, pp. 13–84.

- ^ a b Taxidou 2004, pp. 193–209.

- ^ Mitchell, Tony (1999). Dario Fo: People's Court Jester (Updated and Expanded). London: Methuen. ISBN 0-413-73320-3.

- ^ Scuderi, Antonio (2011). Dario Fo: Framing, Festival, and the Folkloric Imagination. Lanham (Md.): Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739151112.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1997". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ Gordon 2006, p. 194.

- ^ Aristotle Poetics 1447a13 (1987, 1).[full citation needed]

- ^ Carlson 1993, p. 19.

- ^ Janko 1987, pp. xx, 7–10.

- ^ Carlson 1993, p. 16.

- ^ Benedetti 1999, pp. 124, 202.

- ^ Benedetti 2008, p. 6.

- ^ Carnicke 1998, p. 162.

- ^ Gauss 1999, p. 2.

- ^ a b Banham 1998, p. 1032.

- ^ Carnicke 1998, p. 1.

- ^ Counsell 1996, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Gordon 2006, pp. 37–40.

- ^ Leach 2004, p. 29.

- ^ a b Counsell 1996, p. 25.

- ^ Carnicke 1998, pp. 1, 167.

- ^ Counsell 1996, p. 24.

- ^ Milling & Ley 2001, p. 1.

- ^ Benedetti 2005, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Carnicke 1998, pp. 1, 8.

- ^ Peterson 1982.

- ^ Griffin, Clive (2007). Opera (1st U.S. ed.). New York: Collins. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-06-124182-6.

- ^ Alice T. Carter, "Non-traditional venues can inspire art, or just great performances Archived 2010-09-03 at the Wayback Machine", Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, July 7, 2008. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Actors' Equity Association joins other arts, entertainment and media industry unions To Announce Legislative Push To Advance Diversity, Equity and Inclusion". Actors' Equity Association. February 11, 2021. Archived from the original on October 1, 2023. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- ^ "About". Equity. Archived from the original on January 8, 2023. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ "About Us". MEAA. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

General sources

[edit]- Banham, Martin, ed. (1998) [1995]. The Cambridge Guide to Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43437-8.

- Beacham, Richard C. (1996). The Roman Theatre and Its Audience. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-77914-3.

- Benedetti, Jean (1999) [1988]. Stanislavski: His Life and Art (Rev. ed.). London: Methuen. ISBN 0-413-52520-1.

- Benedetti, Jean (2005). The Art of the Actor: The Essential History of Acting, From Classical Times to the Present Day. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-413-77336-1.

- Benedetti, Jean (2008). Dacre, Kathy; Fryer, Paul (eds.). Stanislavski on Stage. Sidcup, Kent: Stanislavski Centre Rose Bruford College. pp. 6–9. ISBN 978-1-903454-01-5.

- Black, Joseph, ed. (2010) [2006]. The Broadview Anthology of British Literature: Volume 3: The Restoration and the Eighteenth Century. Canada: Broadview Press. ISBN 978-1-55111-611-2.

- Brandon, James R. (1993) [1981]. "Introduction". In Baumer, Rachel Van M.; Brandon, James R. (eds.). Sanskrit Theatre in Performance. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. pp. xvii–xx. ISBN 978-81-208-0772-3.

- Brandon, James R., ed. (1997). The Cambridge Guide to Asian Theatre (2nd, rev. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58822-5.

- Brockett, Oscar G. & Hildy, Franklin J. (2003). History of the Theatre (Ninth, International ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 0-205-41050-2.

- Brown, Andrew (1998). "Greece, Ancient". In Banham, Martin (ed.). The Cambridge Guide to Theatre (Rev. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 441–447. ISBN 0-521-43437-8.

- Burt, Daniel S. (2008). The Drama 100: A Ranking of the Greatest Plays of All Time. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-6073-3.

- Carlson, Marvin (Fall 1986). "Psychic Polyphony". Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism: 35–47.

- Carlson, Marvin (1993). Theories of the Theatre: A Historical and Critical Survey from the Greeks to the Present (Expanded ed.). Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8154-6.

- Carnicke, Sharon Marie (1998). Stanislavsky in Focus. Russian Theatre Archive series. London: Harwood Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-5755-070-9.

- Cartledge, Paul (1997). "'Deep Plays': Theatre as Process in Greek Civic Life". In Easterling, P. E. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Greek Tragedy. Cambridge Companions to Literature series. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–35. ISBN 0-521-42351-1.

- Counsell, Colin (1996). Signs of Performance: An Introduction to Twentieth-Century Theatre. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-10643-6.

- Deal, William E. (2007). Handbook to Life in Medieval and Early Modern Japan. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533126-4.

- Duchartre, Pierre Louis (1966) [1929]. The Italian Comedy: The Improvisation Scenarios Lives Attributes Portraits and Masks of the Illustrious Characters of the Commedia dell'Arte. Translated by Randolph T. Weaver. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-21679-9.

- Dukore, Bernard F., ed. (1974). Dramatic Theory and Criticism: Greeks to Grotowski. Florence, Kentucky: Heinle & Heinle. ISBN 978-0-03-091152-1.

- Elam, Keir (1980). The Semiotics of Theatre and Drama. New Accents series. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-03984-0.

- Fergusson, Francis (1968) [1949]. The Idea of a Theater: A Study of Ten Plays, The Art of Drama in a Changing Perspective. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01288-1.

- Gassner, John & Allen, Ralph G. (1992) [1964]. Theatre and Drama in the Making. New York: Applause Books. ISBN 1-55783-073-8.

- Gauss, Rebecca B. (1999). Lear's Daughters: The Studios of the Moscow Art Theatre 1905–1927. American University Studies, Ser. 26 Theatre Arts. Vol. 29. New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-4155-9.

- Goldhill, Simon (1997). "The Audience of Athenian Tragedy". In Easterling, P. E. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Greek Tragedy. Cambridge Companions to Literature series. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 54–68. ISBN 0-521-42351-1.

- Goldhill, Simon (2004). "Programme Notes". In Goldhill, Simon; Osborne, Robin (eds.). Performance Culture and Athenian Democracy (New ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–29. ISBN 978-0-521-60431-4.

- Gordon, Mel (1983). Lazzi: The Comic Routines of the Commedia dell'Arte. New York: Performing Arts Journal. ISBN 0-933826-69-9.

- Gordon, Robert (2006). The Purpose of Playing: Modern Acting Theories in Perspective. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-06887-6.

- Aristotle (1987). Poetics with Tractatus Coislinianus, Reconstruction of Poetics II and the Fragments of the On Poets. Translated by Janko, Richard. Cambridge: Hackett. ISBN 978-0-87220-033-3.

- Johnstone, Keith (2007) [1981]. Impro: Improvisation and the Theatre (Rev. ed.). London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-7136-8701-9.

- Jones, John Bush (2003). Our Musicals, Ourselves: A Social History of the American Musical Theatre. Hanover: Brandeis University Press. ISBN 1-58465-311-6.

- Kovacs, David (2005). "Text and Transmission". In Gregory, Justina (ed.). A Companion to Greek Tragedy. Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World series. Malden, MA and Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 379–393. ISBN 1-4051-7549-4.

- Kuritz, Paul (1988). The Making of Theatre History. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-547861-5.

- Leach, Robert (2004). Makers of Modern Theatre: An Introduction. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-31241-7.

- Ley, Graham (2007). The Theatricality of Greek Tragedy: Playing Space and Chorus. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-47757-2.

- Milling, Jane; Ley, Graham (2001). Modern Theories of Performance: From Stanislavski to Boal. Basingstoke, Hampshire, and New York: Palgrave. ISBN 978-0-333-77542-4.

- Moreh, Shmuel (1986). "Live Theater in Medieval Islam". In Sharon, Moshe (ed.). Studies in Islamic History and Civilization in Honour of Professor David Ayalon. Cana, Leiden: Brill. pp. 565–601. ISBN 965-264-014-X.

- Pavis, Patrice (1998). Dictionary of the Theatre: Terms, Concepts, and Analysis. Translated by Christine Shantz. Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-8163-6.

- Pelling, Christopher (2005). "Tragedy, Rhetoric, and Performance Culture". In Gregory, Justina (ed.). A Companion to Greek Tragedy. Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World series. Malden, MA and Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 83–102. ISBN 1-4051-7549-4.

- Peterson, Richard A. (1982). "Five Constraints on the Production of Culture: Law, Technology, Market, Organizational Structure and Occupational Careers". The Journal of Popular Culture. 16 (2): 143–153. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1982.1451443.x.

- Pfister, Manfred (2000) [1977]. The Theory and Analysis of Drama. European Studies in English Literature series. Translated by John Halliday. Cambridige: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-42383-0.

- Rehm, Rusj (1992). Greek Tragic Theatre. Theatre Production Studies. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-11894-8.

- Richmond, Farley (1998) [1995]. "India". In Banham, Martin (ed.). The Cambridge Guide to Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 516–525. ISBN 0-521-43437-8.

- Richmond, Farley P.; Swann, Darius L. & Zarrilli, Phillip B., eds. (1993). Indian Theatre: Traditions of Performance. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1322-2.

- Spolin, Viola (1999) [1963]. Improvisation for the Theater (3rd ed.). Evanston, Il: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 0-8101-4008-X.

- Styan, J. L. (2000). Drama: A Guide to the Study of Plays. New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-4489-5.

- Taxidou, Olga (2004). Tragedy, Modernity and Mourning. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-1987-9.

- Ward, A.C (2007) [1945]. Specimens of English Dramatic Criticism XVII–XX Centuries. The World's Classics series. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-4086-3115-7.

- Webster, T. B. L. (1967). "Monuments Illustrating Tragedy and Satyr Play". Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies (Supplement, with appendix) (20) (2nd ed.). University of London: iii–190.

- Williams, Raymond (1966). Modern Tragedy. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0-7011-1260-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Aston, Elaine, and George Savona. 1991. Theatre as Sign-System: A Semiotics of Text and Performance. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-04932-0.

- Benjamin, Walter. 1928. The Origin of German Tragic Drama. Trans. John Osborne. London and New York: Verso, 1998. ISBN 1-85984-899-0.

- Brown, John Russell. 1997. What is Theatre?: An Introduction and Exploration. Boston and Oxford: Focal P. ISBN 978-0-240-80232-9.

- Bryant, Jye (2018). Writing & Staging A New Musical: A Handbook. Kindle Direct Publishing. ISBN 9781730897412.

- Carnicke, Sharon Marie (2000). "Stanislavsky's System: Pathways for the Actor". In Hodge, Alison (ed.). Twentieth-Century Actor Training. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 11–36. ISBN 978-0-415-19452-5.

- Dacre, Kathy, and Paul Fryer, eds. 2008. Stanislavski on Stage. Sidcup, Kent: Stanislavski Centre Rose Bruford College. ISBN 1-903454-01-8.

- Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari. 1972. Anti-Œdipus. Trans. Robert Hurley, Mark Seem and Helen R. Lane. London and New York: Continuum, 2004. Vol. 1. New Accents Ser. London and New York: Methuen. ISBN 0-416-72060-9.

- Felski, Rita, ed. 2008. Rethinking Tragedy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-8740-2.

- Harrison, Martin. 1998. The Language of Theatre. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0878300877.

- Hartnoll, Phyllis, ed. 1983. The Oxford Companion to the Theatre. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-211546-1.

- Leach, Robert (1989). Vsevolod Meyerhold. Directors in Perspective series. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31843-3.

- Leach, Robert, and Victor Borovsky, eds. 1999. A History of Russian Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-03435-7.

- Meyer-Dinkgräfe, Daniel. 2001. Approaches to Acting: Past and Present. London and New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-7879-5.

- Meyerhold, Vsevolod. 1991. Meyerhold on Theatre. Ed. and trans. Edward Braun. Rev. ed., London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-413-38790-5.

- Mitter, Shomit. 1992. Systems of Rehearsal: Stanislavsky, Brecht, Grotowski and Brook. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-06784-3.

- O'Brien, Nick. 2010. Stanislavski In Practise. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-56843-2.

- Rayner, Alice. 1994. To Act, To Do, To Perform: Drama and the Phenomenology of Action. Theater: Theory/Text/Performance Ser. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-10537-3.

- Roach, Joseph R. 1985. The Player's Passion: Studies in the Science of Acting. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08244-5.

- Piccitto, Diane & Robinson, Terry F., eds. (2023). The Visual Life of Romantic Theater, 1780-1830. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472132881.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - Speirs, Ronald, trans. 1999. The Birth of Tragedy and Other Writings. By Friedrich Nietzsche. Ed. Raymond Geuss and Ronald Speirs. Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy ser. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-63987-5.

- Teachout, Terry (December 13, 2021). "The Best Theater of 2021: The Curtain Goes Up Again". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

External links

[edit]- Theatre Archive Project (UK) British Library & University of Sheffield.

- University of Bristol Theatre Collection

- Music Hall and Theatre History of Britain and Ireland

- Department of Theatre Arts Design Portfolios