Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

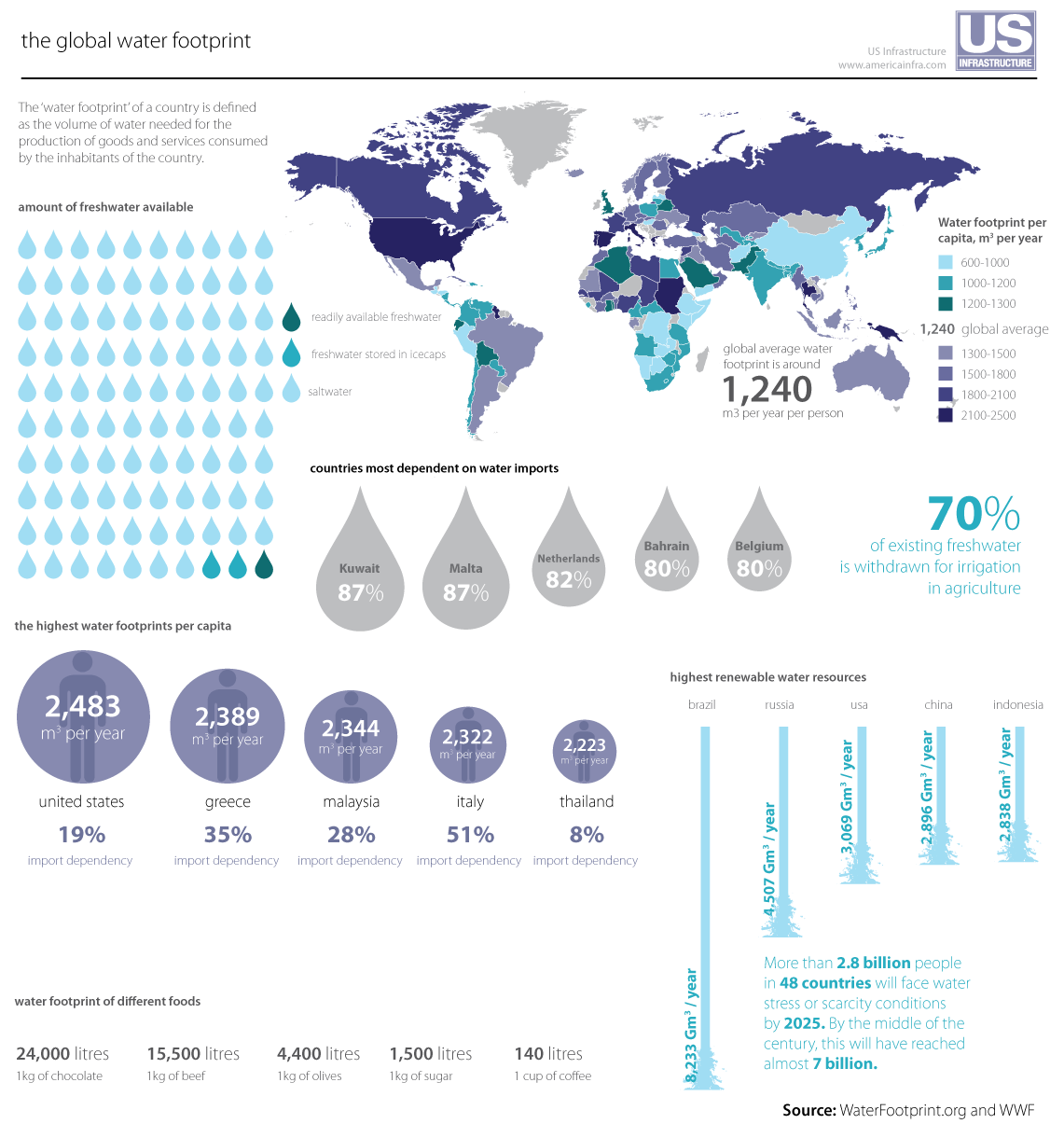

Water footprint

View on WikipediaThis article may incorporate text from a large language model. (August 2025) |

A water footprint shows the extent of water use in relation to consumption by people.[1] The water footprint of an individual, community, or business is defined as the total volume of fresh water used to produce the goods and services consumed by the individual or community or produced by the business. Water use is measured in water volume consumed (evaporated) and/or polluted per unit of time. A water footprint can be calculated for any well-defined group of consumers (e.g., an individual, family, village, city, province, state, or nation) or producers (e.g., a public organization, private enterprise, or economic sector), for a single process (such as growing rice) or for any product or service.[2]

Traditionally, water use has been approached from the production side, by quantifying the following three columns of water use: water withdrawals in the agricultural, industrial, and domestic sector. While this does provide valuable data, it is a limited way of looking at water use in a globalised world, in which products are not always consumed in their country of origin. International trade of agricultural and industrial products in effect creates a global flow of virtual water, or embodied water (akin to the concept of embodied energy).[1]

In 2002, the water footprint concept was introduced in order to have a consumption-based indicator of water use, that could provide useful information in addition to the traditional production-sector-based indicators of water use. It is analogous to the ecological footprint concept introduced in the 1990s. The water footprint is a geographically explicit indicator, not only showing volumes of water use and pollution, but also the locations.[3] The global issue of water footprinting underscores the importance of fair and sustainable resource management. Due to increasing water shortages, climate change, and environmental concerns, transitioning towards a fair impact of water use is critical. The water footprint concept offers detailed insights for adequate and equitable water resource management. It advocates for a balanced and sustainable water-use approach, aiming to tackle global challenges. This approach is essential for responsible and equitable water resource utilization globally. Thus, it gives a grasp on how economic choices and processes influence the availability of adequate water resources and other ecological realities across the globe (and vice versa).

Definition and measures

[edit]There are many different aspects to water footprint and therefore different definitions and measures to describe them. Blue water footprint refers to groundwater or surface water usage, green water footprint refers to rainwater, and grey water footprint refers to the amount of water needed to dilute pollutants.[4]

Blue water footprint

[edit]A blue water footprint refers to the volume of water that has been sourced from surface or groundwater resources (lakes, rivers, wetlands and aquifers) and has either evaporated (for example while irrigating crops), or been incorporated into a product or taken from one body of water and returned to another, or returned at a different time. Irrigated agriculture, industry and domestic water use can each have a blue water footprint.[5]

Green water footprint

[edit]A green water footprint refers to the amount of water from precipitation that, after having been stored in the root zone of the soil (green water), is either lost by evapotranspiration or incorporated by plants. It is particularly relevant for agricultural, horticultural and forestry products.[5]

Grey water footprint

[edit]A grey water footprint refers to the volume of water that is required to dilute pollutants (industrial discharges, seepage from tailing ponds at mining operations, untreated municipal wastewater, or nonpoint source pollution such as agricultural runoff or urban runoff) to such an extent that the quality of the water meets agreed water quality standards.[5] It is calculated as:

where L is the pollutant load (as mass flux), cmax the maximum allowable concentration and cnat the natural concentration of the pollutant in the receiving water body (both expressed in mass/volume).[6]

Calculation for different factors

[edit]The water footprint of a process is expressed as volumetric flow rate of water. That of a product is the whole footprint (sum) of processes in its complete supply chain divided by the number of product units. For consumers, businesses and geographic area, water footprint is indicated as volume of water per time, in particular:[6]

- That of a consumer is the sum of footprint of all consumed products.

- That of a community or a nation is the sum for all of its members resp. inhabitants.

- That of a business is the footprint of all produced goods.

- That of a geographically delineated area is the footprint of all processes undertaken in this area. The virtual change in water of an area is the net import of virtual water Vi, net, defined as the difference of the gross import Vi of virtual water from its gross export Ve. The water footprint of national consumption WFarea,nat results from this as the sum of the water footprint of national area and its virtual change in water.

History

[edit]The concept of a water footprint was coined in 2002, by Arjen Hoekstra, Professor in water management at the University of Twente, Netherlands, and co-founder and scientific director of the Water Footprint Network, whilst working at the UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education, as a metric to measure the amount of water consumed and polluted to produce goods and services along their full supply chain.[7][8][9] Water footprint is one of a family of ecological footprint indicators, which also includes carbon footprint and land footprint. The water footprint concept is further related to the idea of virtual water trade introduced in the early 1990s by Professor John Allan (2008 Stockholm Water Prize Laureate). The most elaborate publications on how to estimate water footprints are a 2004 report on the Water footprint of nations from UNESCO-IHE,[10] the 2008 book Globalization of Water,[11] and the 2011 manual The water footprint assessment manual: Setting the global standard.[12] Cooperation between global leading institutions in the field has led to the establishment of the Water Footprint Network in 2008.

Water Footprint Network (WFN)

[edit]The Water Footprint Network is an international learning community (a non-profit foundation under Dutch law) which serves as a platform for sharing knowledge, tools and innovations among governments, businesses and communities concerned about growing water scarcity and increasing water pollution levels, and their impacts on people and nature. The network consists of around 100 partners from all sectors – producers, investors, suppliers and regulators – as well as non-governmental organisations and academics. It describes its mission as follows:

To provide science-based, practical solutions and strategic insights that empower companies, governments, individuals and small-scale producers to transform the way we use and share fresh water within earth's limits.[7]

International standard

[edit]In February 2011, the Water Footprint Network, in a global collaborative effort of environmental organizations, companies, research institutions and the UN, launched the Global Water Footprint Standard. In July 2014, the International Organization for Standardization issued ISO 14046:2014, Environmental management—Water footprint—Principles, requirements and guidelines, to provide practical guidance to practitioners from various backgrounds, such as large companies, public authorities, non-governmental organizations, academic and research groups as well as small and medium enterprises, for carrying out a water footprint assessment. The ISO standard is based on life-cycle assessment (LCA) principles and can be applied for different sorts of assessment of products and companies.[13]

Life-cycle assessment of water use

[edit]Life-cycle assessment (LCA) is a systematic, phased approach to assessing the environmental aspects and potential impacts that are associated with a product, process or service. "Life cycle" refers to the major activities connected with the product's life-span, from its manufacture, use, and maintenance, to its final disposal, and also including the acquisition of raw material required to manufacture the product.[14] Thus a method for assessing the environmental impacts of freshwater consumption was developed. It specifically looks at the damage to three areas of protection: human health, ecosystem quality, and resources. The consideration of water consumption is crucial where water-intensive products (for example agricultural goods) are concerned that need to therefore undergo a life-cycle assessment.[15] In addition, regional assessments are equally as necessary as the impact of water use depends on its location. In short, LCA is important as it identifies the impact of water use in certain products, consumers, companies, nations, etc. which can help reduce the amount of water used.[16]

Water positive

[edit]The Water Positive initiative can be defined as the concept where an entity, such as a company, community, or individual, goes beyond simply conserving water and actively contributes to the sustainable management and restoration of water resources. A commercial or residential development is considered water positive when it generates more water than it consumes. This involves implementing practices and technologies that reduce water consumption, improve water quality, and enhance water availability. The goal of being water positive is to leave a positive impact on water ecosystem and ensure that more water is conserved and restored than is used or depleted.[17][18][19][20]

Water availability

[edit]

Globally, about 4 percent of precipitation falling on land each year (about 117,000 km3 (28,000 cu mi)),[21] is used by rain-fed agriculture and about half is subject to evaporation and transpiration in forests and other natural or quasi-natural landscapes.[22] The remainder, which goes to groundwater replenishment and surface runoff, is sometimes called "total actual renewable freshwater resources". Its magnitude was in 2012 estimated at 52,579 km3 (12,614 cu mi)/year.[23] It represents water that can be used either in-stream or after withdrawal from surface and groundwater sources. Of this remainder, about 3,918 km3 (940 cu mi) were withdrawn in 2007, of which 2,722 km3 (653 cu mi), or 69 percent, were used by agriculture, and 734 km3 (176 cu mi), or 19 percent, by other industry.[24] Most agricultural use of withdrawn water is for irrigation, which uses about 5.1 percent of total actual renewable freshwater resources.[23] World water use has been growing rapidly in the last hundred years.[25][26]

Water footprint of products (agricultural sector)

[edit]

The water footprint of a product is the total volume of freshwater used to produce the product, summed over the various steps of the production chain. The water footprint of a product refers not only to the total volume of water used; it also refers to where and when the water is used.[27] The Water Footprint Network maintains a global database on the water footprint of products: WaterStat.[28] Nearly over 70% of the water supply worldwide is used in the agricultural sector.[29][clarification needed]

The water footprints involved in various diets vary greatly, and much of the variation tends to be associated with levels of meat consumption.[30] The following table gives examples of estimated global average water footprints of popular agricultural products.[31][32][33]

| Product | Global average water footprint, L/kg |

|---|---|

| almonds, shelled | 16,194 |

| apple | 822 |

| avocado | 283 |

| banana | 790 |

| beef | 15,415 |

| bread, wheat | 1,608 |

| butter | 5,553 |

| cabbage | 237 |

| cheese | 3,178 |

| chicken | 4,325 |

| chocolate | 17,196 |

| cotton lint | 9,114 |

| cucumber | 353 |

| dates | 2,277 |

| eggs | 3,300 |

| groundnuts, shell | 2,782 |

| leather (bovine) | 17,093 |

| e | 238 |

| maize | 1,222 |

| mango/guava | 1,800 |

| milk | 1,021 |

| olive oil | 14,430 |

| orange | 560 |

| pasta (dry) | 1,849 |

| peach/nectarine | 910 |

| pork | 5,988 |

| potato | 287 |

| pumpkin | 353 |

| rice | 2,497 |

| tomatoes, fresh | 214 |

| tomatoes, dried | 4,275 |

| vanilla beans | 126,505 |

Water footprint of companies (industrial sector)

[edit]The water footprint of a business, the 'corporate water footprint', is defined as the total volume of freshwater that is used directly or indirectly to run and support a business. It is the total volume of water use to be associated with the use of the business outputs. The water footprint of a business consists of water used for producing/manufacturing or for supporting activities and the indirect water use in the producer's supply chain.

The Carbon Trust argue that a more robust approach is for businesses to go beyond simple volumetric measurement to assess the full range of water impact from all sites. Its work with leading global pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) analysed four key categories: water availability, water quality, health impacts, and licence to operate (including reputational and regulatory risks) in order to enable GSK to quantitatively measure, and credibly reduce, its year-on-year water impact.[34]

The Coca-Cola Company operates over a thousand manufacturing plants in about 200 countries. Making its drink uses a lot of water. Critics say its water footprint has been large. Coca-Cola has started to look at its water sustainability.[35] It has now set out goals to reduce its water footprint such as treating the water it uses so it goes back into the environment in a clean state. Another goal is to find sustainable sources for the raw materials it uses in its drinks, such as sugarcane, oranges, and maize. By making its water footprint better, the company can reduce costs, improve the environment, and benefit the communities in which it operates.[36]

Water footprint of individual consumers (domestic sector)

[edit]The water footprint of an individual refers to the sum of their direct and indirect freshwater use. The direct water use is the water used at home, while the indirect water use relates to the total volume of freshwater that is used to produce the goods and services consumed.

The average global water footprint of an individual is 1,385 m3 per year. Residents of some example nations have water footprints as shown in the table:

| Nation | annual water footprint |

|---|---|

| China | 1,071 m3[37] |

| Finland | 1,733 m3[38][unreliable source?] |

| India | 1,089 m3[37] |

| United Kingdom | 1,695 m3[39] |

| United States | 2,842 m3[40] |

Water footprint of nations

[edit]

The water footprint of a nation is the amount of water used to produce the goods and services consumed by the inhabitants of that nation. Analysis of the water footprint of nations illustrates the global dimension of water consumption and pollution, by showing that several countries rely heavily on foreign water resources and that (consumption patterns in) many countries significantly and in various ways impact how, and how much, water is being consumed and polluted elsewhere on Earth. International water dependencies are substantial and are likely to increase with continued global trade liberalisation. The largest share (76%) of the virtual water flows between countries is related to international trade in crops and derived crop products. Trade in animal products and industrial products contributed 12% each to the global virtual water flows. The four major direct factors determining the water footprint of a country are: volume of consumption (related to the gross national income); consumption pattern (e.g. high versus low meat consumption); climate (growth conditions); and agricultural practice (water use efficiency).[1]

Production or consumption

[edit]The assessment of total water use in connection to consumption can be approached from both ends of the supply chain.[41] The water footprint of production estimates how much water from local sources is used or polluted in order to provide the goods and services produced in that country. The water footprint of consumption of a country looks at the amount of water used or polluted (locally, or in the case of imported goods, in other countries) in connection with all the goods and services that are consumed by the inhabitants of that country. The water footprint of production and that of consumption, can also be estimated for any administrative unit such as a city, province, river basin or the entire world.[1]

Absolute or per capita

[edit]The absolute water footprint is the total sum of water footprints of all people. A country's per capita water footprint (that nation's water footprint divided by its number of inhabitants) can be used to compare its water footprint with those of other nations.

The global water footprint in the period 1996–2005 was 9.087 Gm3/yr (Billion Cubic Metres per year, or 9.087.000.000.000.000 liters/year), of which 74% was and green, 11% blue, 15% grey. This is an average amount per capita of 1.385 Gm3/yr., or 3.800 liters per person per day.[42] On average 92% of this is embedded in agricultural products consumed, 4.4% in industrial products consumed, and 3.6% is domestic water use. The global water footprint related to producing goods for export is 1.762 Gm3/y.[43]

In absolute terms, India is the country with the largest water footprint in the world, a total of 987 Gm3/yr. In relative terms (i.e. taking population size into account), the people of the USA have the largest water footprint, with 2480 m3/yr per capita, followed by the people in south European countries such as Greece, Italy and Spain (2300–2400 m3/yr per capita). High water footprints can also be found in Malaysia and Thailand. In contrast, the Chinese people have a relatively low per capita water footprint with an average of 700 m3/yr.[1] (These numbers are also from the period 1996–2005.)

Internal or external

[edit]

The internal water footprint is the amount of water used from domestic water resources; the external water footprint is the amount of water used in other countries to produce goods and services imported and consumed by the inhabitants of the country. When assessing the water footprint of a nation, it is crucial to take into account the international flows of virtual water (also called embodied water, i.e. the water used or polluted in connection to all agricultural and industrial commodities) leaving and entering the country. When taking the use of domestic water resources as a starting point for calculating a nation's water footprint, one should subtract the virtual water flows that leave the country and add the virtual water flows that enter the country.[1]

The external part of a nation's water footprint varies strongly from country to country. Some African nations, such as Sudan, Mali, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Malawi and Chad have hardly any external water footprint, simply because they have little import. Some European countries on the other hand—e.g. Italy, Germany, the UK and the Netherlands—have external water footprints that constitute 50–80% of their total water footprint. The agricultural products that on average contribute most to the external water footprints of nations are: bovine meat, soybean, wheat, cocoa, rice, cotton and maize.[1]

The top 10 gross virtual water exporting nations, which together account for more than half of the global virtual water export, are the United States (314 Gm3/year), China (143 Gm3/year), India (125 Gm3/year), Brazil (112 Gm3/year), Argentina (98 Gm3/year), Canada (91 Gm3/year), Australia (89 Gm3/year), Indonesia (72 Gm3/year), France (65 Gm3/year), and Germany (64 Gm3/year).[43]

The top 10 gross virtual water importing nations are the United States (234 Gm3/year), Japan (127 Gm3/year), Germany (125 Gm3/year), China (121 Gm3/year), Italy (101 Gm3/year), Mexico (92 Gm3/year), France (78 Gm3/year), the United Kingdom (77 Gm3/year), and The Netherlands (71 Gm3/year).[43]

Water use in continents

[edit]Europe

[edit]Each EU citizen consumes 4,815 litres of water per day on average; 44% is used in power production primarily to cool thermal plants or nuclear power plants. Energy production annual water consumption in the EU 27 in 2011 was, in billion m3: for gas 0.53, coal 1.54 and nuclear 2.44. Wind energy avoided the use of 387 million cubic metres (mn m3) of water in 2012, avoiding a cost of €743 million.[44][45]

Asia

[edit]In south India the state Tamil Nadu is one of the main agricultural producers in India and it relies largely in groundwater for irrigation. In ten years, from 2002 to 2012, the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment calculated that the groundwater reduced in 1.4 m yr−1, which "is nearly 8% more than the annual recharge rate."[29]

Environmental water use

[edit]Although agriculture's water use includes provision of important terrestrial environmental values (as discussed in the "Water footprint of products" section above), and much "green water" is used in maintaining forests and wild lands, there is also direct environmental use (e.g. of surface water) that may be allocated by governments. For example, in California, where water use issues are sometimes severe because of drought, about 48 percent of "dedicated water use" in an average water year is for the environment (somewhat more than for agriculture).[46] Such environmental water use is for keeping streams flowing, maintaining aquatic and riparian habitats, keeping wetlands wet, etc.

Water Footprint of Artificial Intelligence

[edit]The rapid growth of artificial intelligence poses some serious environmental concerns one of which is its exceptionally high water footprint. To function, AI technology requires vast amounts of data therefore data centers are growing across the world. These data centers use water in two ways: direct and indirect. They directly use vast amounts of electricity which need to be generated and this requires significant amounts of water and they indirectly use large quantities of water for cooling.[47] This cooling occurs by circulating water through the data center which absorbs heat. As a result of this data centers have an exceptionally high water footprint, and in particular AI data centers. This is a result of the higher level processing that AI requires so there is a higher energy usage therefore more water is needed to generate the electricity and more cooling is necessary.[47]

The rate of AI development has been rapid in recent years, with data centers expected to account for 3.5 percent of the world's electricity use by 2030.[48] This rapid development, in particular with regard to water usage, have sparked concern amongst the global community, particularly in areas already facing water scarcity.[47] Whilst it is difficult to know exactly the statistics behind the water usage of AI, due to a lack of available statistics directly from the companies themselves, we can see the impact through examples such as the Great Salt Lake Basin, which is host to a number of data centers as a result of its cheap water, but which is experiencing new lows in water level year on year.[49]

This is a problem which is being addressed, with major tech companies such as Microsoft, Meta, Amazon and Google aiming to become water positive by 2030,[47] with Meta also promising to restore 200% of the water they consume in high water stress regions and 100% of the water they consume in medium water stress regions.[49] Furthermore, there are innovative solutions being developed, such as Google's using non-potable water at over 25% of its data centers, and developing new techniques using either low-water alternatives or recycled wastewater to try and reduce their water footprint. Furthermore, their Hamina data center in Finland uses sea water for cooling which is heated and then cooled again before being returned to the sea. Microsoft are attempting to utilize adiabatic cooling which substitutes the water for outside air, as well as developing Project Natick to try and build a submerged data center which makes use of the sea temperature for cooling.[47]

Criticism

[edit]Insufficient consideration of consequences of proposed water saving policies to farm households

[edit]According to Dennis Wichelns of the International Water Management Institute: "Although one goal of virtual water analysis is to describe opportunities for improving water security, there is almost no mention of the potential impacts of the prescriptions arising from that analysis on farm households in industrialized or developing countries. It is essential to consider more carefully the inherent flaws in the virtual water and water footprint perspectives, particularly when seeking guidance regarding policy decisions."[50]

Regional water scarcity should be taken into account when interpreting water footprint

[edit]The application and interpretation of water footprints may sometimes be used to promote industrial activities that lead to facile criticism of certain products. For example, the 140 litres required for coffee production for one cup[2] might be of no harm to water resources if its cultivation occurs mainly in humid areas, but could be damaging in more arid regions. Other factors such as hydrology, climate, geology, topography, population and demographics should also be taken into account. Nevertheless, high water footprint calculations do suggest that environmental concern may be appropriate.

Many of the criticisms, including the above ones, compare the description of the water footprint of a water system to generated impacts, which is about its performance. Such a comparison between descriptive and performance factors and indicators is basically flawed.[51]

Disproportionality in Measuring the Effects of Grey Water

[edit]In regards to grey water footprints, the current system has difficulties when it comes to accurately depicting the effect of pollution and dilution based contributions towards water footprints as opposed to usage.[52] The effects of contamination are not considered to be different from that of scarcity, though the two have different effects on both human life and the environment.

It is possible for many different waste byproducts to have effects on an ecosystem, and common water footprints approaches that only test for a few of these byproducts do not capture the complete harm done to the environment.[53] One form of unaccounted for environmental degradation can be found in marine ecosystem degradation. One of the most widely considered concerns in marine ecosystem degradation pertains to eutrophication, which is measured by the amount of nitrogen emitted by a body of water.[54][55] However, it is also possible for industrial waste to have other contaminants in the water, such as other oils or compounds, that can not be measured in the same way that eutrophication can, and therefore will not be accounted for in degradation reports without proper testing methods of their own.[55]

Waste byproducts also affect the quality of drinking water in a similar manner. In China, the byproducts of industrial waste result in heavy metals and salts being polluted into the public water supply.[54] Though water footprints methods do account for the actual water polluted by the contaminants, it does not factor in the amount of water needed to dilute the contaminated water in order to get it to reasonable levels. A similar phenomenon can be seen in an analysis on California's water usage.[56] Whereas the blue and green water components were able to be traced by researchers, the gray water component proved to be difficult to obtain data for by comparison. Therefore, due to a lack of consideration of all factors, water footprints fails to capture the entirety of the impact of industrial waste. If the effects of a process on the environment are unclear during the process of water footprints, it decreases the accuracy of the resulting report.

Effects of Location and Globalization on Water Footprints

[edit]Water footprints also have difficulties when attempting to trace the total environmental impact on a global scale, as opposed to the effect in a singular area. With the globalization of the economy and how multiple processes are involved in the creation of a product, different procedures may have different impacts on the environment.[57] However, these processes can not be measured using general metrics, as the procedures that one facility may use to complete that process, be through necessity or efficiency, may not necessarily be the same as another facility tasked with the same procedure.[58] This introduces spatiality - that is, the location from which waste originates - as another axis of consideration in the problem of evaluating water footprints.[55] These implications apply to water footprints, as the environmental effects and contribution to scarcity similarly can not be assessed through generalization.[59]

The spatial effects can also be observed when looking at the concepts of direct and indirect water footprints.[58] Direct water footprint can be defined as water that is used at a specific site to generate or maintain conditions necessary to create a given product. Indirect water footprint can be defined as water that is used to complete the intermediate steps required for many products, such as harvesting foods or fuel sources.[60] While direct water footprint can be measured by taking reports from a specific facility to the amount of water that they use or dilute, indirect water footprints brings their own complications. Indirect water footprints tend to have high variability due to geographical factors.[60] For instance, One proponent of indirect water foot printing is tracing the amount of water used to extract the raw petroleum needed to transport a commodity. Since the amount of fuel used depends on the distance a shipment needs to travel, it can vary greatly between countries, depending on how far resources need to be transported.[60] The multifaceted nature of indirect water footprint sources makes it difficult to accurately assess all of the separate aspects contributing to a product, and even more so the total impact.[59]

Though these criticisms bring merit, these problems are somewhat reduced when water footprint is not used as a lone indicator, but is instead interpreted in context.[61] On the topic of grey water, adequate consideration of all possible consequences of industrial processes can do well to alleviate these issues.[62][63] When a well-rounded measurement is taken of all of the pollutants that a form of waste can introduce to the environment, it greatly enhances the accuracy of the calculation. On the issue of spatial differences, the use of water availability as a factor assists in determining the proportion of water in a given area a certain water footprint applies to. When data relevant to the specific situation is gathered, both about water and process used and different spatial factors, it becomes more feasible to extrapolate calculations using the water footprint system.[64]

The use of the term footprint can also confuse people familiar with the notion of a carbon footprint, because the water footprint concept includes sums of water quantities without necessarily evaluating related impacts. This is in contrast to the carbon footprint, where carbon emissions are not simply summarized but normalized by CO2 emissions, which are globally identical, to account for the environmental harm. The difference is due to the somewhat more complex nature of water; while involved in the global hydrological cycle, it is expressed in conditions both local and regional through various forms like river basins, watersheds, on down to groundwater (as part of larger aquifer systems). Furthermore, looking at the definition of the footprint itself, and comparing ecological footprint, carbon footprint and water footprint, we realize that the three terms are indeed legitimate.[51]

Sustainable water use

[edit]Sustainable water use involves the rigorous assessment of all source of clean water to establish the current and future rates of use, the impacts of that use both downstream and in the wider area where the water may be used and the impact of contaminated water streams on the environment and economic well-being of the area. It also involves the implementation of social policies such as water pricing in order to manage water demand.[65] In some localities, water may also have spiritual relevance and the use of such water may need to take account of such interests. For example, the Maori believe that water is the source and foundation of all life and have many spiritual associations with water and places associated with water.[66] On a national and global scale, water sustainability requires strategic and long term planning to ensure appropriate sources of clean water are identified and the environmental and economic impact of such choices are understood and accepted.[67] The re-use and reclamation of water is also part of sustainability including downstream impacts on both surface waters and ground waters.[36]

Sustainability assessment

[edit]Water footprint accounting has advanced substantially in recent years, however, water footprint analysis also needs sustainability assessment as its last phase.[12] One of the developments is to employ sustainable efficiency and equity ("Sefficiency in Sequity"), which present a comprehensive approach to assessing the sustainable use of water.[51][68]

Sectoral distributions of withdrawn water use

[edit]Several nations estimate sectoral distribution of use of water withdrawn from surface and groundwater sources. For example, in Canada, in 2005, 42 billion m3 of withdrawn water were used, of which about 38 billion m3 were freshwater. Distribution of this use among sectors was: thermoelectric power generation 66.2%, manufacturing 13.6%, residential 9.0%, agriculture 4.7%, commercial and institutional 2.7%, water treatment and distribution systems 2.3%, mining 1.1%, and oil and gas extraction 0.5%. The 38 billion m3 of freshwater withdrawn in that year can be compared with the nation's annual freshwater yield (estimated as streamflow) of 3,472 billion m3.[69] Sectoral distribution is different in many respects in the US, where agriculture accounts for about 39% of fresh water withdrawals, thermoelectric power generation 38%, industrial 4%, residential 1%, and mining (including oil and gas) 1%.[70]

Within the agricultural sector, withdrawn water use is for irrigation and for livestock. Whereas all irrigation in the US (including loss in conveyance of irrigation water) is estimated to account for about 38 percent of US withdrawn freshwater use,[70] the irrigation water used for production of livestock feed and forage has been estimated to account for about 9 percent,[71] and other withdrawn freshwater use for the livestock sector (for drinking, washdown of facilities, etc.) is estimated at 0.7 percent.[70] Because agriculture is a major user of withdrawn water, changes in the magnitude and efficiency of its water use are important. In the US, from 1980 (when agriculture's withdrawn water use peaked) to 2010, there was a 23 percent reduction in agriculture's use of withdrawn water,[70] while US agricultural output increased by 49 percent over that period.[72]

In the US, irrigation water application data are collected in the quinquennial Farm and Ranch Irrigation Survey, conducted as part of the Census of Agriculture. Such data indicate great differences in irrigation water use within various agricultural sectors. For example, about 14 percent of corn-for-grain land and 11 percent of soybean land in the US are irrigated, compared with 66 percent of vegetable land, 79 percent of orchard land and 97 percent of rice land.[73][74]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g "Water footprints of nations: Water use by people as a function of their consumption pattern" (PDF). Water Footprint Network. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Waterfootprint.org: Water footprint and virtual water". The Water Footprint Network. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ Definition taken from the Hoekstra, A.Y. and Chapagain, A.K. (2008) Globalization of water: Sharing the planet's freshwater resources, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, UK.

- ^ "16030, 1841-01-13, PERROT (fabrique)". Art Sales Catalogues Online. doi:10.1163/2210-7886_asc-16030. Retrieved 2021-10-25.

- ^ a b c "What is a water footprint?". The Water Footprint Network. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- ^ a b "The Water Footprint Assessment Manual". Water Footprint Network. Archived from the original on 2015-02-10. Retrieved 2015-01-20.

- ^ a b "Water Footprint Network - Aims & history". Water Footprint Network. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ Jayne M. Godfrey, Keryn Chalmers. 2012 Water Accounting: International Approaches to Policy and Decision-making. Edward Elgar Publishing. page222

- ^ Hoekstra, A.Y. (2003) (ed) Virtual water trade: Proceedings of the International Expert Meeting on Virtual Water Trade, IHE Delft, the Netherlands [1]

- ^ "Water footprints of nations" (PDF). UNESCO-IHE. Retrieved 2023-11-07.

- ^ Globalization of Water, A.Y. Hoekstra and A.K. Chapagain, Blackwell, 2008

- ^ a b Hoekstra, Arjen (2011). The water footprint assessment manual: Setting the global standard (PDF). London: Earthscan. ISBN 978-1-84971-279-8.

- ^ "ISO 14046:2014 Environmental management -- Water footprint -- Principles, requirements and guidelines". International Organization for Standardization. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Scientific Applications International Corporations (SAIC) (2006). Life Cycle Assessment: Principles and Practice. Reston, VA: SAIC.

- ^ Pfister, Stephan; Koehler, Annette; Hellweg, Stefanie (20 March 2009). "Assessing the Environmental Impacts of Freshwater Consumption in LCA". Environmental Science. 43 (11): 4008–104. Bibcode:2009EnST...43.4098P. doi:10.1021/es802423e. PMID 19569336.

- ^ Pfister, Stephan; Boulay, Anne-Marie; Berger, Markus; Hadjikakou, Michalis; Motoshita, Masaharu; Hess, Tim; Ridoutt, Brad; Weinzettel, Jan; Scherer, Laura; Döll, Petra; Manzardo, Alessandro; Núñez, Montserrat; Verones, Francesca; Humbert, Sebastien; Buxmann, Kurt; Harding, Kevin; Benini, Lorenzo; Oki, Taikan; Finkbeiner, Matthias; Henderson, Andrew (January 2017). "Understanding the LCA and ISO water footprint: A response to Hoekstra (2016) "A critique on the water-scarcity weighted water footprint in LCA"". Ecological Indicators. 72: 352–359. Bibcode:2017EcInd..72..352P. doi:10.1016/J.ECOLIND.2016.07.051. PMC 6192425. PMID 30344449.

- ^ Loher, Nicole (2023-03-15). "What Does it Mean to Be 'Water Positive'?". Meta Sustainability. Retrieved 2023-12-22.

- ^ "¿Qué es ser "water positive"? El nuevo objetivo de las grandes compañías". Hidrología Sostenible (in Spanish). 2022-05-10. Retrieved 2023-12-22.

- ^ Schupak, Amanda (2021-10-14). "Corporations are pledging to be 'water positive'. What does that mean?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2023-12-22.

- ^ Pandey, Rajdeep (2018-10-23). "Water Positive Campus". Enviraj. Retrieved 2024-04-24.

- ^ Schneider, U.; et al. (2014). "GPCC's new land surface precipitation climatology based on quality-controlled in-situ data and its role in quantifying the global water cycle". Theoretical and Applied Climatology. 115 (1–2): 15–40. Bibcode:2014ThApC.115...15S. doi:10.1007/s00704-013-0860-x.

- ^ "Water Use". FAO. Retrieved 2023-11-07.

- ^ a b Frenken, K. and V. Gillet. 2012. Irrigation water requirement and water withdrawal by country. AQUASTAT, FAO.

- ^ "Water withdrawal by sector, around 2007" (PDF). FAO. 2014. Retrieved 2023-11-07.

- ^ "Looming water crisis simply a management problem" by Jonathan Chenoweth, New Scientist 28 Aug., 2008, pp. 28-32.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (2017-11-20). "Water Use and Stress". Our World in Data.

- ^ "WFN Glossary". Archived from the original on 2015-04-01. Retrieved 2012-10-02.

- ^ "WaterStat". Archived from the original on 2015-04-01. Retrieved 2012-10-02.

- ^ a b Chinnasamy, Pennan; Agoramoorthy, Govindasamy (2015-05-01). "Groundwater Storage and Depletion Trends in Tamil Nadu State, India". Water Resources Management. 29 (7): 2139–2152. Bibcode:2015WatRM..29.2139C. doi:10.1007/s11269-015-0932-z. ISSN 1573-1650. S2CID 54761901.

- ^ Vanham, D., M. M.Mekonnen and A. Y. Hoekstra. 2013. The water footprint of the EU for different diets. Ecological Indicators 32: 1-8.

- ^ Mekonnen, M. M. and A. Y. Hoekstra. 2010. The green, blue and grey water footprint of farm animals and animal products. Volume 1: Main report. UNESCO-IHE., Institute for Water Education. 50 pp.

- ^ Mekonnen, M. M. and A. Y. Hoekstra. 2010. The green, blue and grey water footprint of crops and derived crop products. Volume 2. Appendices main report. Value of Water Research Report Series No. 47. UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education. 1196 pp.

- ^ "How much water does it take to grow an avocado?". Danwatch.dk. 2019. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "Water, water everywhere... or is it?", The Carbon Trust, 26 November 2014. Retrieved on 20 January 2015.

- ^ "2013 Water Report: The Coca-Cola Company". The Coca-Cola Company. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ^ a b Naumann, Ruth (2011). Sustainability (1st ed.). North Shore, N.Z.: Cengage Learning. pp. 56–58. ISBN 978-017021-034-8.

- ^ a b Hoekstra, AY (2012). "The Water Footprint of Humanity" (PDF). PNAS. 109 (9): 3232–3237. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.3232H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1109936109. PMC 3295316. PMID 22331890.

- ^ Data obtained from the Finnish Wikipedia article page Vesijalanjälki

- ^ Chapagain, A.K. & Orr, S. "U.K. Water Footprint: The Impact of the U.K.'s Food and Fibre Consumption on Global Water Resources, Volume 1" (PDF). WWF-UK. and volume 2 Chapagain, A.K. & Orr, S. "Volume 2" (PDF). WWF-UK.

- ^ "The Water Footprint of Humanity". JournalistsResource.org, retrieved 20 March 2012

- ^ "National water footprint". waterfootprint.org. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ "Angela Morelli - The Global Water Footprint of Humanity". youtube.com. TEDxOslo. 21 June 2011.

- ^ a b c Hoekstra, Arjen Y.; Mekonnen, Mesfin M. (28 February 2012). "The water footprint of humanity". PNAS. 109 (9): 3232–3237. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.3232H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1109936109. PMC 3295316. PMID 22331890.

- ^ Saving water with wind energy, EWEA June 2014

- ^ "Saving water with wind energy Summary EWEA". EWEA.org. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ "California State Water Project-Water Supply". www.Water.ca.gov. Archived from the original on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "Data centres 'straining water resources' as AI swells". SciDev.Net. Retrieved 2025-10-07.

- ^ Singh, Shweta; Dahlmann, Frederik (2025-09-12). "Regulating AI use could stop its runaway energy expansion". doi.org. Retrieved 2025-10-07.

- ^ a b "Researchers warn water usage is unnoticed environmental threat of AI data centers | InsideAIPolicy.com". insideaipolicy.com. Retrieved 2025-10-07.

- ^ Wichelns, Dennis (2010). "Virtual water and water footprints offer limited insight regarding important policy questions". International Journal of Water Resources Development. 26 (4): 639–651. Bibcode:2010IJWRD..26..639W. doi:10.1080/07900627.2010.519494. S2CID 154664691. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ a b c Haie, N.; Freitas, M.R.; Pereira, J.C. (2018). "Integrating Water Footprint and Sefficiency: Overcoming Water Footprint Criticisms and Improving Decision Making". Water Alternatives. 11: 933–956.

- ^ Wang, Dan; Hubacek, Klaus; Shan, Yuli; Gerbens-Leenes, Winnie; Liu, Junguo (2021-01-15). "A Review of Water Stress and Water Footprint Accounting". Water. 13 (2): 201. Bibcode:2021Water..13..201W. doi:10.3390/w13020201. ISSN 2073-4441.

- ^ Chenoweth, J.; Hadjikakou, M.; Zoumides, C. (2014-06-24). "Quantifying the human impact on water resources: a critical review of the water footprint concept". Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. 18 (6): 2325–2342. Bibcode:2014HESS...18.2325C. doi:10.5194/hess-18-2325-2014. hdl:1959.4/unsworks_12791. ISSN 1027-5606.

- ^ a b Li, Hui; Liang, Sai; Liang, Yuhan; Li, Ke; Qi, Jianchuan; Yang, Xuechun; Feng, Cuiyang; Cai, Yanpeng; Yang, Zhifeng (2021-01-01). "Multi-pollutant based grey water footprint of Chinese regions". Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 164 105202. Bibcode:2021RCR...16405202L. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105202. ISSN 0921-3449.

- ^ a b c Mikosch, Natalia; Berger, Markus; Finkbeiner, Matthias (2021-01-01). "Addressing water quality in water footprinting: current status, methods and limitations". The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment. 26 (1): 157–174. Bibcode:2021IJLCA..26..157M. doi:10.1007/s11367-020-01838-1. ISSN 1614-7502.

- ^ Fulton, Julian; Cooley, Heather (2015-03-17). "The Water Footprint of California's Energy System, 1990–2012". Environmental Science & Technology. 49 (6): 3314–3321. Bibcode:2015EnST...49.3314F. doi:10.1021/es505034x. ISSN 0013-936X. PMID 25719565.

- ^ Ridoutt, B. G.; Eady, S. J.; Sellahewa, J.; Simons, L.; Bektash, R. (2009-09-01). "Water footprinting at the product brand level: case study and future challenges". Journal of Cleaner Production. 17 (13): 1228–1235. Bibcode:2009JCPro..17.1228R. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2009.03.002. ISSN 0959-6526.

- ^ a b Chini, Christopher M.; Konar, Megan; Stillwell, Ashlynn S. (2017). "Direct and indirect urban water footprints of the United States". Water Resources Research. 53 (1): 316–327. Bibcode:2017WRR....53..316C. doi:10.1002/2016WR019473. ISSN 1944-7973.

- ^ a b Berger, Markus; Pfister, Stephan; Motoshita, Masaharu (2016), Finkbeiner, Matthias (ed.), "Water Footprinting in Life Cycle Assessment: How to Count the Drops and Assess the Impacts?", Special Types of Life Cycle Assessment, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 73–114, doi:10.1007/978-94-017-7610-3_3, ISBN 978-94-017-7608-0, retrieved 2025-10-11

- ^ a b c Renouf, Marguerite A.; Kenway, Steven J. (2017). "Evaluation Approaches for Advancing Urban Water Goals". Journal of Industrial Ecology. 21 (4): 995–1009. Bibcode:2017JInEc..21..995R. doi:10.1111/jiec.12456. ISSN 1530-9290.

- ^ Vanham, Davy; Bidoglio, Giovanni (2013-03-01). "A review on the indicator water footprint for the EU28". Ecological Indicators. 26: 61–75. Bibcode:2013EcInd..26...61V. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2012.10.021. ISSN 1470-160X.

- ^ Ahmad, Shamshad; Majhi, Pradeep K.; Kothari, Richa; Singh, Rajeev Pratap (2020), Shukla, Vertika; Kumar, Narendra (eds.), "Industrial Wastewater Footprinting: A Need for Water Security in Indian Context", Environmental Concerns and Sustainable Development, Singapore: Springer Singapore, pp. 197–212, doi:10.1007/978-981-13-5889-0_10, ISBN 978-981-13-5888-3, retrieved 2025-10-11

- ^ Zib, Louis; Byrne, Diana M.; Marston, Landon T.; Chini, Christopher M. (2021-10-25). "Operational carbon footprint of the U.S. water and wastewater sector's energy consumption". Journal of Cleaner Production. 321 128815. Bibcode:2021JCPro.32128815Z. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128815. ISSN 0959-6526.

- ^ Tillotson, Martin R.; Liu, Junguo; Guan, Dabo; Wu, Pute; Zhao, Xu; Zhang, Guoping; Pfister, Stephan; Pahlow, Markus (2014-08-01). "Water Footprint Symposium: where next for water footprint and water assessment methodology?". The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment. 19 (8): 1561–1565. Bibcode:2014IJLCA..19.1561T. doi:10.1007/s11367-014-0770-x. ISSN 1614-7502.

- ^ "Policies and measure to promote sustainable water use". Europeanm Environment Agency. 18 February 2008. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ^ e Ahukaramū Charles Royal (22 September 2012). "Tangaroa – the sea - Water as the source of life". Encyclopaedia of New Zealand.

- ^ Water Consumption and Sustainable Water Resources Management. OECD Library. 25 March 1998. ISBN 9789264162648. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ^ Haie, Naim (2020). Transparent Water Management Theory: Sefficiency in Sequity (PDF). Springer.

- ^ Statistics Canada. 2010. Human activity and the environment. Freshwater supply and demand in Canada. Catalogue no. 16-201-X.

- ^ a b c d Maupin, M. A. et al. 2014. Estimated use of water in the United States 2010. U. S. Geological Survey Circular 1405. 55 pp.

- ^ Zering, K. D., T. J. Centner, D. Meyer, G. L. Newton, J. M. Sweeten and S. Woodruff. 2012. Water and land issues associated with animal agriculture: a U.S. perspective. CAST Issue Paper No. 50. Council for Agricultural Science and Technology, Ames, Iowa. 24 pp.

- ^ "USDA ERS - Agricultural Productivity in the U.S." www.ERS.USDA.gov. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ US Department of Agriculture. 2009. 2007 Census of agriculture. Farm and ranch irrigation survey (2008). Volume 3. Special Studies. Part 1. AC-07-SS-1. 177 pp. + appendices.

- ^ USDA. 2009. 2007 Census of agriculture. United States summary and State Data. Vol. 1. Geographic Area Series. Part 51. AC-07-A-51. 639 pp. + appendices.

External links

[edit]Water footprint

View on GrokipediaConceptual Foundations

Definition and Core Principles

The water footprint quantifies the total volume of freshwater appropriated for the production of goods and services, encompassing both direct and indirect uses across the supply chain, measured in cubic meters per unit of product, person, or economic activity. Introduced by hydrologist Arjen Y. Hoekstra in 2002 at the University of Twente, it extends beyond traditional water withdrawal metrics by emphasizing consumption—water evaporated, transpired, or incorporated into products—and pollution assimilation, thereby accounting for the full hydrological impact of human activities.[1][9] This consumption-based framework contrasts with production-based accounting, which often obscures trade-related water transfers, as evidenced by global virtual water flows exceeding 2,300 billion cubic meters annually in the early 2000s, primarily embedded in agricultural exports from water-scarce regions.[10] At its core, the water footprint decomposes into three distinct components to capture the sources and types of freshwater use: green, blue, and grey. The green water footprint measures the volume of rainwater and soil moisture consumed by crops or vegetation through evapotranspiration, representing the largest share globally at approximately 74% of total footprints in assessments from 1996–2005.[1][4] The blue water footprint tracks the consumption of surface and groundwater, such as irrigation diversions that are not returned to the source, comprising about 11% of global totals and critical in arid areas where overuse depletes aquifers.[1][4] The grey water footprint estimates the dilution volume needed to restore polluted water to natural background levels, calculated as the load of pollutants (e.g., nitrogen or phosphorus) divided by the maximum acceptable concentration minus ambient levels, accounting for roughly 15% of footprints and highlighting contamination from fertilizers, industrial effluents, and wastewater.[3][11] These components together provide a comprehensive volumetric indicator, enabling causal tracing of water scarcity from consumption patterns back to upstream extraction and degradation. Fundamental principles underlying the water footprint include volumetric aggregation for comparability, supply-chain inclusivity to reveal hidden dependencies (e.g., a single cotton t-shirt requiring over 2,500 liters, mostly green water in rainfed cultivation), and integration with local availability thresholds for sustainability evaluation.[12] Unlike efficiency-focused metrics that ignore pollution or trade, it prioritizes empirical hydrological balances, such as equating footprints to evaporative losses plus assimilated contaminants, grounded in mass balance equations from agro-hydrological models.[13] This approach underscores causal realism in resource use, where global trade amplifies local scarcities—e.g., water-abundant nations importing high-footprint goods from stressed basins—without assuming equivalence across water types, as green water supports ecosystems differently from blue.[14] Assessments adhering to these principles, as standardized by the Water Footprint Network, facilitate targeted reductions, such as shifting to low-grey alternatives in manufacturing, but require validation against field data to avoid overgeneralization from modeled estimates.[13]Components of Water Footprint

The water footprint consists of three primary components: green, blue, and grey, each quantifying distinct forms of water consumption and pollution across production processes, supply chains, or consumption activities. These components, expressed in cubic meters of water per unit of product or per capita, enable a volumetric assessment that differentiates water sources, uses, and impacts, facilitating comparisons of sustainability and efficiency.[1][15] The green water footprint measures the volume of rainwater evaporated or transpired by plants, or retained in the soil as moisture for crop growth, primarily in rain-fed systems. It captures the productive use of precipitation that would otherwise evaporate or percolate unused, with global estimates indicating that green water constitutes about 74% of agricultural water footprints due to its dominance in crop evapotranspiration. This component highlights the reliance on natural rainfall, which varies regionally and is vulnerable to climate variability.[15][1] The blue water footprint quantifies the volume of surface water and groundwater consumed through evaporation, incorporation into products, or release in a changed form, such as return flows with reduced quality. Blue water, drawn from rivers, lakes, reservoirs, and aquifers, accounts for roughly 20-22% of total human water use globally and is critical in irrigated agriculture, where it supports higher yields but risks depletion of finite resources; for instance, cotton production in arid regions often exhibits high blue footprints exceeding 10,000 cubic meters per ton. Its scarcity in water-stressed basins underscores trade-offs with domestic, industrial, and ecological demands.[15][1] The grey water footprint represents the volume of freshwater needed to dilute pollutants—such as nutrients, chemicals, or sediments—to levels meeting ambient water quality standards, based on the difference between load concentrations and natural background levels. It addresses water pollution's assimilative capacity, with calculations often using the least stringent of national or international standards; in livestock production, grey footprints from manure runoff can reach 3,000-5,000 cubic meters per ton of meat, reflecting eutrophication risks in freshwater systems. This component integrates quality degradation into footprint metrics, emphasizing remediation needs over mere extraction.[15][1]Measurement Methodologies

The water footprint is quantified through volumetric accounting of green, blue, and grey components, as standardized by the Water Footprint Network (WFN) in its 2011 Global Water Footprint Standard and subsequent Assessment Manual. Green water footprint measures the volume of rainwater stored in the soil and subsequently evaporated or incorporated into plant biomass, calculated via dynamic water balance models that integrate crop-specific evapotranspiration data from sources like the FAO AquaCrop model or Penman-Monteith equation, often spatially resolved at grid scales of 5-10 arc minutes. Blue water footprint quantifies the volume of surface or groundwater consumed (evaporated or incorporated), derived from irrigation requirements subtracted by non-consumptive returns, using hydrological models such as MODFLOW for groundwater or SWAT for basin-scale flows. Grey water footprint estimates the volume of freshwater needed to dilute pollutant loads to ambient water quality standards, computed as the difference between maximum allowable concentration and natural background levels divided by the pollutant load per unit product, with standards drawn from national regulations like EU Water Framework Directive thresholds or WHO guidelines for parameters such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and pesticides.[15][16] These calculations employ bottom-up process-based approaches for specific products or processes, tracing water inputs across supply chains using life cycle inventory data, or top-down input-output models for economy-wide estimates, where water use coefficients are multiplied by monetary intersectoral flows from matrices like EXIOBASE or national accounts. For agricultural products, which dominate global footprints (e.g., 92% of humanity's total), crop water footprints integrate daily soil moisture simulations over growing seasons, accounting for variables like planting dates, varieties, and climate data from reanalysis datasets such as ERA5. Industrial processes rely on metering data for direct withdrawals and stoichiometric models for indirect virtual water in inputs, with grey components often dominated by chemical oxygen demand or nutrient excretion loads. Uncertainties arise from data variability, with studies reporting 10-30% ranges for crop models due to parameter sensitivity, necessitating sensitivity analyses and Monte Carlo simulations in robust assessments.[11][15] Complementing the volumetric WFN method, ISO 14046:2014 establishes a life cycle assessment (LCA)-based framework for water footprinting, emphasizing impact assessment over pure volumes by incorporating local water scarcity and ecosystem degradation potentials. It requires defining system boundaries, inventorying water inputs/outputs (e.g., consumption, discharge), and characterizing impacts via methods like ReCiPe or WULCA's Available Water Remaining (AWR) indicator, which weights volumes by withdrawal-to-availability ratios at watershed scales from databases like WaterGAP. This standard mandates goal-and-scope definition, inventory analysis, impact assessment, and interpretation phases, ensuring comparability with broader LCA under ISO 14040/44, but critiques note its complexity limits adoption compared to simpler volumetric metrics. Hybrid approaches combine both, as in corporate reporting where volumetric benchmarks inform scarcity-adjusted sustainability thresholds. Empirical validations, such as global crop studies, confirm methodological consistency across regions, with total footprints for products like cotton at 10,000 m³/ton (70% green, 20% blue, 10% grey) derived from harmonized datasets.[17][18][16]Historical Development

Origins and Early Conceptualization

The origins of the water footprint concept lie in the precursor notion of virtual water, coined by British geographer John Anthony Allan in 1993 to quantify the freshwater embedded in the production of commodities, especially agricultural exports from water-abundant regions to arid importers. Allan's framework explained how international trade effectively transfers water resources, allowing water-scarce nations in the Middle East and North Africa to sustain food security without apparent hydrological limits, though this obscured underlying dependencies on distant supplies.[19] Arjen Y. Hoekstra introduced the water footprint in 2002, extending virtual water analysis to encompass total freshwater consumption linked to end-use rather than mere production or trade flows.[20] Working at the UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education in Delft, Netherlands, Hoekstra co-authored the foundational paper with P.Q. Hung, titled "Virtual water trade: A quantification of virtual water flows between nations in relation to international crop trade," which first applied the term to define a region's or individual's water footprint as the sum of domestic water use in production plus net virtual water imports minus exports.[21] This approach, published as a Value of Water Research Report, estimated that global virtual water flows from crop trade alone exceeded 1,000 billion cubic meters per year during 1995–1999, predominantly from water-rich exporters like the United States and Argentina to importers in Europe and Asia.[22] The early conceptualization positioned the water footprint as a consumption-based metric, analogous to the ecological footprint but tailored to freshwater volumes, to expose hidden hydrological pressures from globalized supply chains and encourage policy shifts toward sustainable allocation.[23] Hoekstra's innovation emphasized volumetric accounting of green (rainwater), blue (surface and groundwater), and later grey (pollution dilution) water components, though initial focus remained on aggregate trade impacts to highlight inefficiencies in water-intensive sectors like agriculture, which accounted for over 90% of embedded flows in early estimates.[24] This laid groundwork for broader applications by revealing that affluent consumers in water-stressed importing nations indirectly drive scarcity elsewhere through demand for low-cost imports.[25]Key Organizations and Standardization

The Water Footprint Network (WFN), established in 2008 by a consortium including the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education, and other partners, has served as the primary organization advancing the water footprint concept globally.[20][26] Building on Arjen Hoekstra's initial formulation of the metric in 2002, the WFN developed and published the Water Footprint Assessment Manual in 2011, which established standardized definitions, calculation methods, and guidelines for assessing blue, green, and grey water footprints across processes, products, and catchments.[27][28] This manual emphasized volumetric accounting of freshwater use and pollution, prioritizing sustainability benchmarks tied to local water scarcity, and has been adopted as a foundational reference for corporate, governmental, and research applications.[15] In parallel, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) formalized water footprint assessment through ISO 14046:2014, Environmental management — Water footprint — Principles, requirements and guidelines.[17] Released in August 2014, this standard integrates water footprinting within life cycle assessment (LCA) frameworks, requiring evaluation of water use impacts on availability, quality, and ecosystem health, while allowing standalone or comparative applications for products, processes, or organizations.[29][30] Unlike the WFN's primary focus on consumption volumes, ISO 14046 incorporates impact pathways, such as deprivation potential, to address criticisms of volumetric metrics' limitations in capturing scarcity effects; however, proponents of the WFN approach argue it better supports resource efficiency decisions without diluting focus through aggregated impact weighting.[31] These efforts reflect ongoing tensions in standardization, with the WFN promoting supply-chain-wide volumetric tracking for policy and trade analysis, while ISO aligns with broader environmental management systems like ISO 14001.[32] Additional collaborations, such as those under the CEO Water Mandate, have tested WFN methodologies in corporate contexts, reinforcing the 2011 Global Water Footprint Standard's role in practical implementation.[33] Despite these advancements, no universal consensus exists, as evidenced by debates over integrating water quality thresholds and ambient standards into grey water calculations.[15]Evolution and Integration with Other Frameworks

The water footprint concept originated in 2002, developed by Arjen Y. Hoekstra at the UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education as a volumetric indicator of freshwater use analogous to the ecological footprint, emphasizing consumption-based rather than production-based accounting to capture indirect water demands in global supply chains.[20] Hoekstra's early publications, such as those quantifying national water footprints for food products, laid the groundwork by distinguishing green (rainwater), blue (surface and groundwater), and later grey (pollution dilution) components, enabling assessments of humanity's total appropriation of freshwater resources.[23] By 2008, the establishment of the Water Footprint Network (WFN) marked a pivotal shift toward institutionalization, fostering collaboration among researchers, businesses, and policymakers to refine methodologies and promote global application.[20] Standardization accelerated with the release of the WFN's Water Footprint Assessment Manual in 2011, which provided a comprehensive framework for calculating, mapping, and evaluating water footprints at process, product, and national scales, including sustainability criteria based on local water availability and environmental flow requirements.[28] This manual established the Global Water Footprint Standard, influencing subsequent empirical studies, such as the 2012 PNAS mapping of humanity's water footprint at high spatial resolution, which revealed that agricultural production accounts for 92% of global blue and green water consumption.[34] Post-2011 developments included refinements to address criticisms of oversimplification in volumetric measures, incorporating stress-weighted indicators to better reflect regional scarcity, as seen in updated WFN guidelines by 2019.[35] Integration with other frameworks has positioned the water footprint as a complementary tool in broader sustainability analyses, particularly life cycle assessment (LCA), where it supplies inventory data on water consumption volumes that LCA's impact assessment phase then characterizes using methods like scarcity-adjusted factors under ISO 14046 standards.[36] Unlike pure LCA, which prioritizes endpoint impacts on human health and ecosystems, the water footprint's strength lies in its spatially explicit, consumption-oriented volumetric tracking, enabling hybrid approaches—for instance, combining WF accounting with LCA's characterization models to evaluate bioenergy or agricultural products' full water-related burdens.[37] This synergy has been applied in integrated assessments, such as those aligning WF with planetary boundaries for freshwater use or Sustainable Development Goal 6 on clean water, where WF data informs probabilistic models of resource pressures under uncertainty.[38] In corporate ESG reporting, WF metrics are embedded alongside carbon and ecological footprints to quantify supply chain risks, as evidenced by tools from organizations like the CEO Water Mandate adopting WFN standards for holistic resource efficiency evaluations.[32]Applications and Empirical Assessments

Agricultural and Product-Level Footprints

Agriculture constitutes the dominant component of the global water footprint, accounting for approximately 92% of total anthropogenic water use embedded in products consumed worldwide.[39] This share reflects the extensive evaporative losses and pollution assimilation associated with crop cultivation and livestock rearing, with consumptive water use in agriculture reaching 99% of global totals when excluding non-consumptive industrial withdrawals.[40] Crop production alone drives the majority, with derived animal products amplifying footprints through feed requirements that constitute up to one-third of agricultural water use.[41] At the crop level, water footprints are calculated by integrating green water (rainfall evaporated or incorporated into biomass), blue water (surface and groundwater evaporation from irrigation), and grey water (dilution volume for pollution). Global assessments reveal significant variation across commodities; for instance, cereal crops average 1,644 cubic meters per ton, with wheat at 1,827 m³/ton and maize lower due to higher yields in rainfed systems.[11] Rice exhibits a higher footprint of about 3,400 m³/ton, predominantly green water in paddy fields, though blue water dominates in irrigated regions like Asia.[42] Cotton lint production averages 10,000 liters per kilogram globally, with 73% green water but substantial blue contributions in arid production areas such as India and Uzbekistan.[43] Livestock products demonstrate amplified footprints owing to inefficient feed conversion. Beef requires an average of 15,400 m³/ton, approximately 20 times the caloric footprint of cereals, as 98% of its water use embeds in feed crops like soy and maize.[44] Pork and poultry footprints are lower at around 6,000 and 4,300 m³/ton, respectively, reflecting better feed efficiency.[41] These values derive from process-based models accounting for regional yield, evapotranspiration, and pollution loads, highlighting how production intensification in water-scarce areas can elevate blue and grey components.[11] Illustrative examples underscore the variability in product-level water footprints. One kilogram of beef requires approximately 15,000 liters, 1 kg of chocolate about 17,000 liters due to water-intensive cocoa cultivation in certain regions, and 1 kg of almonds around 16,000 liters owing to extensive irrigation needs, particularly in California. A 125 ml cup of coffee consumes roughly 140 liters, while 1 kg of cheese ranges from 3,200 to 5,000 liters. In comparison, 1 kg of tomatoes requires about 215 liters and 1 kg of bread 1,600 liters. These figures demonstrate the disproportionately high water use of animal products and certain luxury foods such as nuts and cocoa.[41][11]| Product | Average Water Footprint (m³/ton) | Dominant Component |

|---|---|---|

| Beef | 15,400 | Green (feed) |

| Rice | 3,400 | Green |

| Cotton (lint) | 10,000 | Green |

| Cereals (avg.) | 1,644 | Green |