Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mustard gas

View on Wikipedia

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

1-Chloro-2-[(2-chloroethyl)sulfanyl]ethane | |

| Other names

Bis(2-chloroethyl) sulfide

HD Iprit Schwefel-LOST Lost Sulfur mustard Senfgas Yellow cross liquid Yperite Distilled mustard Mustard T- mixture 1,1'-thiobis[2-chloroethane] Dichlorodiethyl sulfide | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| 1733595 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.209.973 |

| EC Number |

|

| 324535 | |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C4H8Cl2S | |

| Molar mass | 159.07 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colorless if pure. Normally ranges from pale yellow to dark brown. Slight garlic or horseradish type odor.[1] |

| Density | 1.27 g/mL, liquid |

| Melting point | 14.45 °C (58.01 °F; 287.60 K) |

| Boiling point | 217 °C (423 °F; 490 K) begins to decompose at 217 °C (423 °F) and boils at 218 °C (424 °F) |

| 7.6 mg/L at 20°C[2] | |

| Solubility | Alcohols, ethers, hydrocarbons, lipids, THF |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards

|

Flammable, toxic, vesicant, carcinogenic, mutagenic |

| GHS labelling:[3] | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H300, H310, H315, H319, H330, H335 | |

| P260, P261, P262, P264, P270, P271, P280, P284, P301+P310, P302+P350, P302+P352, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P310, P312, P320, P321, P322, P330, P332+P313, P337+P313, P361, P362, P363, P403+P233, P405, P501 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | 105 °C (221 °F; 378 K) |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | External MSDS |

| Related compounds | |

Related compounds

|

Nitrogen mustard, Bis(chloroethyl) ether, Chloromethyl methyl sulfide |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Mustard gas or sulfur mustard are names commonly used for the organosulfur chemical compound bis(2-chloroethyl) sulfide, which has the chemical structure S(CH2CH2Cl)2, as well as other species. In the wider sense, compounds with the substituents −SCH2CH2X or −N(CH2CH2X)2 are known as sulfur mustards or nitrogen mustards, respectively, where X = Cl or Br. Such compounds are potent alkylating agents, making mustard gas acutely and severely toxic.[3] Mustard gas is a carcinogen.[3] There is no preventative agent against mustard gas, with protection depending entirely on skin and airways protection, and no antidote exists for mustard poisoning.[4]

Also known as mustard agents, this family of compounds comprises infamous cytotoxins and blister agents with a long history of use as chemical weapons.[4] The name mustard gas is technically incorrect; the substances, when dispersed, are often not gases but a fine mist of liquid droplets that can be readily absorbed through the skin and by inhalation.[3] The skin can be affected by contact with either the liquid or vapor. The rate of penetration into skin is proportional to dose, temperature and humidity.[3]

Sulfur mustards are viscous liquids at room temperature and have an odor resembling mustard plants, garlic, or horseradish, hence the name.[3][4] When pure, they are colorless, but when used in impure forms, such as in warfare, they are usually yellow-brown. Mustard gases form blisters on exposed skin and in the lungs, often resulting in prolonged illness ending in death.[4]

Etymology

[edit]The name of mustard gas derived from its yellow color, smell of mustard, and burning sensation on eyes.[5] The term was first used in 1917 during World War I when Germans used the poison in combat.[5]

History as chemical weapons

[edit]Sulfur mustard is a type of chemical warfare agent.[6] As a chemical weapon, mustard gas has been used in several armed conflicts since World War I, including the Iran–Iraq War, resulting in more than 100,000 casualties.[7][8] Sulfur-based and nitrogen-based mustard agents are regulated under Schedule 1 of the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention, as substances with few uses other than in chemical warfare.[4][9] Mustard agents can be deployed by means of artillery shells, aerial bombs, rockets, or by spraying from aircraft.

Adverse health effects

[edit]

Mustard gases have powerful blistering effects on victims. They are also carcinogenic and mutagenic alkylating agents.[3] Their high lipophilicity accelerates their absorption into the body.[2] Because mustard agents often do not elicit immediate symptoms, contaminated areas may appear normal.[4] Within 24 hours of exposure, victims experience intense itching and skin irritation. If this irritation goes untreated, blisters filled with pus can form wherever the agent contacted the skin.[4] As chemical burns, these are severely debilitating.[3] Mustard gas can have the effect of turning a patient's skin different colors due to melanogenesis.[10][4]

If the victim's eyes were exposed, then they become sore, starting with conjunctivitis (also known as pink eye), after which the eyelids swell, resulting in temporary blindness. Extreme ocular exposure to mustard gas vapors may result in corneal ulceration, anterior chamber scarring, and neovascularization.[11][12][13][14] In these severe and infrequent cases, corneal transplantation has been used as a treatment.[15] Miosis, when the pupil constricts more than usual, may also occur, which may be the result of the cholinomimetic activity of mustard.[16] If inhaled in high concentrations, mustard agents cause bleeding and blistering within the respiratory system, damaging mucous membranes and causing pulmonary edema.[4] Depending on the level of contamination, mustard agent burns can vary between first and second degree burns. They can also be as severe, disfiguring, and dangerous as third degree burns. Some 80% of sulfur mustard in contact with the skin evaporates, while 10% stays in the skin and 10% is absorbed and circulated in the blood.[3]

The carcinogenic and mutagenic effects of exposure to mustard gas increase the risk of developing cancer later in life.[3] In a study of patients 25 years after wartime exposure to chemical weaponry, c-DNA microarray profiling indicated that 122 genes were significantly mutated in the lungs and airways of mustard gas victims. Those genes all correspond to functions commonly affected by mustard gas exposure, including apoptosis, inflammation, and stress responses.[17] The long-term ocular complications include burning, tearing, itching, photophobia, presbyopia, pain, and foreign-body sensations.[4][18][19]

Medical management

[edit]In a rinse-wipe-rinse sequence, skin is decontaminated of mustard gas by washing with liquid soap and water, or an absorbent powder.[4] The eyes should be thoroughly rinsed using saline or clean water. A topical analgesic is used to relieve skin pain during decontamination.[4] For skin lesions, topical treatments, such as calamine lotion, steroids, and oral antihistamines are used to relieve itching.[4] Larger blisters are irrigated repeatedly with saline or soapy water, then treated with an antibiotic and petroleum gauze.[4]

Mustard agent burns do not heal quickly and (as with other types of burns) present a risk of sepsis caused by pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The mechanisms behind mustard gas's effect on endothelial cells are still being studied, but recent studies have shown that high levels of exposure can induce high rates of both necrosis and apoptosis. In vitro tests have shown that at low concentrations of mustard gas, where apoptosis is the predominant result of exposure, pretreatment with 50 mM N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) was able to decrease the rate of apoptosis. NAC protects actin filaments from reorganization by mustard gas, demonstrating that actin filaments play a large role in the severe burns observed in victims.[20]

A British nurse treating soldiers with mustard agent burns during World War I commented:[21]

They cannot be bandaged or touched. We cover them with a tent of propped-up sheets. Gas burns must be agonizing because usually the other cases do not complain, even with the worst wounds, but gas cases are invariably beyond endurance and they cannot help crying out.

Mechanism of cellular toxicity

[edit]

Sulfur mustards readily eliminate chloride ions by intramolecular nucleophilic substitution to form cyclic sulfonium ions. These very reactive intermediates tend to permanently alkylate nucleotides in DNA strands, which can prevent cellular division, leading to programmed cell death.[2] Alternatively, if cell death is not immediate, the damaged DNA can lead to the development of cancer.[2] Oxidative stress is another pathology involved in mustard gas toxicity.[22]

Various compounds with the structural subgroup BC2H4X, where X is any leaving group and B is a Lewis base, have a common name of mustard. Such compounds can form cyclic "onium" ions (sulfonium, ammonium, etc.) that are good alkylating agents. These compounds include bis(2-haloethyl)ethers (oxygen mustards), the (2-haloethyl)amines (nitrogen mustards), and sesquimustard, which has two α-chloroethyl thioether groups (ClC2H4S−) connected by an ethylene bridge (−C2H4−). These compounds have a similar ability to alkylate DNA, but their physical properties vary.

Formulations

[edit]

In its history, various types and mixtures of mustard gas have been employed. These include:

- H – Also known as HS ("Hun Stuff") or Levinstein mustard. This is named after the inventor of the "quick but dirty" Levinstein Process for manufacture,[23][24] reacting dry ethylene with disulfur dichloride under controlled conditions. Undistilled mustard gas contains 20–30% impurities, which means it does not store as well as HD. Also, as it decomposes, it increases in vapor pressure, making the munition it is contained in likely to split, especially along a seam, releasing the agent to the atmosphere.[1]

- HD – Codenamed Pyro by the British, and Distilled Mustard by the US.[1] Distilled mustard of 95% or higher purity. The term "mustard gas" usually refers to this variety of mustard.

- HT – Codenamed Runcol by the British, and Mustard T- mixture by the US.[1] A mixture of 60% HD mustard and 40% O-mustard, a related vesicant with lower freezing point, lower volatility and similar vesicant characteristics.

- HL – A blend of distilled mustard (HD) and lewisite (L), originally intended for use in winter conditions due to its lower freezing point compared to the pure substances. The lewisite component of HL was used as a form of antifreeze.[25]

- HQ – A blend of distilled mustard (HD) and sesquimustard (Q).[26]

- Yellow Cross – any of several blends containing sulfur mustard.[27] Named for the yellow cross painted on artillery shells.[10]

Commonly-stockpiled mustard agents (class)

[edit]| Chemical | Code | Trivial name | CAS number | PubChem | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bis(2-chloroethyl)sulfide | H, HD | Mustard | 505-60-2 | CID 10461 from PubChem | |

| 1,2-Bis(2-chloroethylsulfanyl) ethane | Q | Sesquimustard | 3563-36-8 | CID 19092 from PubChem | |

| 2-Chloroethyl ethyl sulfide | Half mustard | 693-07-2 | CID 12733 from PubChem | ||

| Bis(2-(2-chloroethylsulfanyl)ethyl) ether | T | O-mustard | 63918-89-8 | CID 45452 from PubChem | |

| 2-Chloroethyl chloromethyl sulfide | 2625-76-5 | ||||

| Bis(2-chloroethylsulfanyl) methane | HK | 63869-13-6 | |||

| 1,3-Bis(2-chloroethylsulfanyl) propane | 63905-10-2 | ||||

| 1,4-Bis(2-chloroethylsulfanyl) butane | 142868-93-7 | ||||

| 1,5-Bis(2-chloroethylsulfanyl) pentane | 142868-94-8 | ||||

| Bis((2-chloroethylsulfanyl)methyl) ether | 63918-90-1 |

History

[edit]Development

[edit]Mustard gases were possibly developed as early as 1822 by César-Mansuète Despretz (1798–1863).[28] Despretz described the reaction of sulfur dichloride and ethylene but never made mention of any irritating properties of the reaction product. In 1854, another French chemist, Alfred Riche (1829–1908), repeated this procedure, also without describing any adverse physiological properties. In 1860, the British scientist Frederick Guthrie synthesized and characterized the mustard agent compound and noted its irritating properties, especially in tasting.[29] Also in 1860, chemist Albert Niemann, known as a pioneer in cocaine chemistry, repeated the reaction, and recorded blister-forming properties. In 1886, Viktor Meyer published a paper describing a synthesis that produced good yields. He combined 2-chloroethanol with aqueous potassium sulfide, and then treated the resulting thiodiglycol with phosphorus trichloride. The purity of this compound was much higher and consequently the adverse health effects upon exposure were much more severe. These symptoms presented themselves in his assistant, and in order to rule out the possibility that his assistant was suffering from a mental illness (psychosomatic symptoms), Meyer had this compound tested on laboratory rabbits, most of which died. In 1913, the English chemist Hans Thacher Clarke (known for the Eschweiler-Clarke reaction) replaced the phosphorus trichloride with hydrochloric acid in Meyer's formulation while working with Emil Fischer in Berlin. Clarke was hospitalized for two months for burns after one of his flasks broke. According to Meyer, Fischer's report on this accident to the German Chemical Society sent the German Empire on the road to chemical weapons.[30]

The German Empire during World War I relied on the Meyer-Clarke method because 2-chloroethanol was readily available from the German dye industry of that time.[31]

Use

[edit]

Mustard gas was first used in World War I by the German army against British and Canadian soldiers near Ypres, Belgium, on July 12, 1917,[32] and later also against the French Second Army. Yperite is "a name used by the French, because the compound was first used at Ypres."[33] The Allies used mustard gas for the first time on November 1917 at Cambrai, France, after the armies had captured a stockpile of German mustard shells. It took the British more than a year to develop their own mustard agent weapon, with production of the chemicals centred on Avonmouth Docks (the only option available to the British was the Despretz–Niemann–Guthrie process).[34][35]

Mustard gas was originally assigned the name LOST, after the scientists Wilhelm Lommel and Wilhelm Steinkopf, who developed a method of large-scale production for the Imperial German Army in 1916.[36]

Mustard gas was dispersed as an aerosol in a mixture with other chemicals, giving it a yellow-brown color. Mustard agent has also been dispersed in such munitions as aerial bombs, land mines, mortar rounds, artillery shells, and rockets.[1] Exposure to mustard agent was lethal in about 1% of cases. Its effectiveness was as an incapacitating agent. The early countermeasures against mustard agent were relatively ineffective, since a soldier wearing a gas mask was not protected against absorbing it through his skin and being blistered. A common countermeasure was using a urine-soaked mask or facecloth to prevent or reduce injury, a readily available remedy attested by soldiers in documentaries (e.g., They Shall Not Grow Old in 2018) and others (such as forward aid nurses) interviewed between 1947 and 1981 by the British Broadcasting Corporation for various World War One history programs; however, the effectiveness of this measure is unclear.

Mustard gas can remain in the ground for weeks, and it continues to cause ill effects. If mustard agent contaminates one's clothing and equipment while cold, then other people with whom they share an enclosed space could become poisoned as contaminated items warm up enough material to become an airborne toxic agent. An example of this was depicted in a British and Canadian documentary about life in the trenches, particularly once the "sousterrain" (subways and berthing areas underground) were completed in Belgium and France. Towards the end of World War I, mustard agent was used in high concentrations as an area-denial weapon that forced troops to abandon heavily contaminated areas.

Since World War I, mustard gas has been used in several wars and other conflicts, usually against people who cannot retaliate in kind:[37]

- United Kingdom against the Red Army in 1919[38]

- Alleged British use in Mesopotamia in 1920[39]

- Spain against the Rifian resistance in Morocco during the Rif War of 1921–27 (see also: Spanish use of chemical weapons in the Rif War)[37][40]

- Italy in Libya in 1930[37]

- The Soviet Union in Xinjiang, Republic of China, during the Soviet Invasion of Xinjiang against the 36th Division (National Revolutionary Army) in 1934, and also in the Xinjiang War (1937) in 1936–37[38][40]

- Italy against Abyssinia (now Ethiopia) in the 1935–1936[37]

- The Empire of Japan against China in the 1937–1945[38]

- The US military conducted experiments with chemical weapons like lewisite and mustard gas on Japanese American, Puerto Rican and African Americans in the US military in World War II to see how non-white races would react to being mustard gassed, with Rollin Edwards describing it as "It felt like you were on fire, guys started screaming and hollering and trying to break out. And then some of the guys fainted. And finally they opened the door and let us out, and the guys were just, they were in bad shape." and "It took all the skin off your hands. Your hands just rotted".[41]

- After World War II, stockpiled mustard gas was dumped by South African military personnel under the command of William Bleloch off Port Elizabeth, resulting in several cases of burns among local trawler crews.[42]

- The United States Government tested effectiveness on US Naval recruits in a laboratory setting at The Great Lakes Naval Base, June 3, 1945[43]

- The 2 December 1943 air raid on Bari destroyed an Allied stockpile of mustard gas on the SS John Harvey,[44] killing 83 and hospitalizing 628.[45]

- Egypt against North Yemen in 1963–1967[37]

- Iraq against Kurds in the town of Halabja during the Halabja chemical attack in 1988[38][46]

- Iraq against Iranians in 1983–1988[47]

- Possibly in Sudan against insurgents in the civil war, in 1995 and 1997.[37]

- In the Iraq War, abandoned stockpiles of mustard gas shells were destroyed in the open air,[48] and were used against Coalition forces in roadside bombs.[49]

- By ISIS forces against Kurdish forces in Iraq in August 2015.[50]

- By ISIS against another rebel group in the town of Mare' in 2015.[51]

- According to Syrian state media, by ISIS against the Syrian Army during the battle in Deir ez-Zor in 2016.[52]

The use of toxic gases or other chemicals, including mustard gas, during warfare is known as chemical warfare, and this kind of warfare was prohibited by the Geneva Protocol of 1925, and also by the later Chemical Weapons Convention of 1993. The latter agreement also prohibits the development, production, stockpiling, and sale of such weapons.

In September 2012, a US official stated that the rebel militant group ISIS was manufacturing and using mustard gas in Syria and Iraq, which was allegedly confirmed by the group's head of chemical weapons development, Sleiman Daoud al-Afari, who has since been captured.[53][54]

Development of the first chemotherapy drug

[edit]As early as 1919 it was known that mustard agent was a suppressor of hematopoiesis.[55] In addition, autopsies performed on 75 soldiers who had died of mustard agent during World War I were done by researchers from the University of Pennsylvania who reported decreased counts of white blood cells.[45] This led the American Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) to finance the biology and chemistry departments at Yale University to conduct research on the use of chemical warfare during World War II.[45][56]

As a part of this effort, the group investigated nitrogen mustard as a therapy for Hodgkin's lymphoma and other types of lymphoma and leukemia, and this compound was tried out on its first human patient in December 1942. The results of this study were not published until 1946, when they were declassified.[56] In a parallel track, after the air raid on Bari in December 1943, the doctors of the U.S. Army noted that white blood cell counts were reduced in their patients. Some years after World War II was over, the incident in Bari and the work of the Yale University group with nitrogen mustard converged, and this prompted a search for other similar chemical compounds. Due to its use in previous studies, the nitrogen mustard called "HN2" became the first cancer chemotherapy drug, chlormethine (also known as mechlorethamine, mustine) to be used. Chlormethine and other mustard gas molecules are still used to this day as an chemotherapy agent albeit they have largely been replaced with more safe chemotherapy drugs like cisplatin and carboplatin.[57]

Disposal

[edit]In the United States, storage and incineration of mustard gas and other chemical weapons were carried out by the U.S. Army Chemical Materials Agency.[58] Disposal projects at the two remaining American chemical weapons sites were carried out near Richmond, Kentucky, and Pueblo, Colorado. The last of the declared mustard weapons stockpile of the United States was destroyed on June 22, 2023 in Pueblo with other remaining chemical weapons being destroyed later in 2023.[59]

New detection techniques are being developed in order to detect the presence of mustard gas and its metabolites. The technology is portable and detects small quantities of the hazardous waste and its oxidized products, which are notorious for harming unsuspecting civilians. The immunochromatographic assay would eliminate the need for expensive, time-consuming lab tests and enable easy-to-read tests to protect civilians from sulfur-mustard dumping sites.[60]

In 1946, 10,000 drums of mustard gas (2,800 tonnes) stored at the production facility of Stormont Chemicals in Cornwall, Ontario, Canada, were loaded onto 187 boxcars for the 900 miles (1,400 km) journey to be buried at sea on board a 400 foot (120 m) long barge 40 miles (64 km) south of Sable Island, southeast of Halifax, at a depth of 600 fathoms (1,100 m). The dump location is 42 degrees, 50 minutes north by 60 degrees, 12 minutes west.[61]

A large British stockpile of old mustard agent that had been made and stored since World War I at M. S. Factory, Valley near Rhydymwyn in Flintshire, Wales, was destroyed in 1958.[62]

Most of the mustard gas found in Germany after World War II was dumped into the Baltic Sea. Between 1966 and 2002, fishermen have found about 700 chemical weapons in the region of Bornholm, most of which contain mustard gas. One of the more frequently dumped weapons was "Sprühbüchse 37" (SprüBü37, Spray Can 37, 1937 being the year of its fielding with the German Army). These weapons contain mustard gas mixed with a thickener, which gives it a tar-like viscosity. When the content of the SprüBü37 comes in contact with water, only the mustard gas in the outer layers of the lumps of viscous mustard hydrolyzes, leaving behind amber-colored residues that still contain most of the active mustard gas. On mechanically breaking these lumps (e.g., with the drag board of a fishing net or by the human hand) the enclosed mustard gas is still as active as it had been at the time the weapon was dumped. These lumps, when washed ashore, can be mistaken for amber, which can lead to severe health problems. Artillery shells containing mustard gas and other toxic ammunition from World War I (as well as conventional explosives) can still be found in France and Belgium. These were formerly disposed of by explosion undersea, but since the current environmental regulations prohibit this, the French government is building an automated factory to dispose of the accumulation of chemical shells.

In 1972, the U.S. Congress banned the practice of disposing of chemical weapons into the ocean by the United States. 29,000 tons of nerve and mustard agents had already been dumped into the ocean off the United States by the U.S. Army. According to a report created in 1998 by William Brankowitz, a deputy project manager in the U.S. Army Chemical Materials Agency, the army created at least 26 chemical weapons dumping sites in the ocean offshore from at least 11 states on both the East Coast and the West Coast (in Operation CHASE, Operation Geranium, etc.). In addition, due to poor recordkeeping, about one-half of the sites have only their rough locations known.[63]

In June 1997, India declared its stock of chemical weapons of 1,044 tonnes (1,151 short tons) of mustard gas.[64][65] By the end of 2006, India had destroyed more than 75 percent of its chemical weapons/material stockpile and was granted extension for destroying the remaining stocks by April 2009 and was expected to achieve 100 percent destruction within that time frame.[64] India informed the United Nations in May 2009 that it had destroyed its stockpile of chemical weapons in compliance with the international Chemical Weapons Convention. With this India has become the third country after South Korea and Albania to do so.[66][67] This was cross-checked by inspectors of the United Nations.

Producing or stockpiling mustard gas is prohibited by the Chemical Weapons Convention. When the convention entered force in 1997, the parties declared worldwide stockpiles of 17,440 tonnes of mustard gas. As of December 2015, 86% of these stockpiles had been destroyed.[68]

A significant portion of the United States' mustard agent stockpile was stored at the Edgewood Area of Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland. Approximately 1,621 tons of mustard agents were stored in one-ton containers on the base under heavy guard. A chemical neutralization plant was built on the proving ground and neutralized the last of this stockpile in February 2005. This stockpile had priority because of the potential for quick reduction of risk to the community. The nearest schools were fitted with overpressurization machinery to protect the students and faculty in the event of a catastrophic explosion and fire at the site. These projects, as well as planning, equipment, and training assistance, were provided to the surrounding community as a part of the Chemical Stockpile Emergency Preparedness Program (CSEPP), a joint program of the Army and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).[69] Unexploded shells containing mustard gases and other chemical agents are still present in several test ranges in proximity to schools in the Edgewood area, but the smaller amounts of poison gas (4 to 14 pounds (1.8 to 6.4 kg)) present considerably lower risks. These remnants are being detected and excavated systematically for disposal. The U.S. Army Chemical Materials Agency oversaw disposal of several other chemical weapons stockpiles located across the United States in compliance with international chemical weapons treaties. These include the complete incineration of the chemical weapons stockpiled in Alabama, Arkansas, Indiana, and Oregon. Earlier, this agency had also completed destruction of the chemical weapons stockpile located on Johnston Atoll located south of Hawaii in the Pacific Ocean.[70] The largest mustard agent stockpile, at approximately 6,200 short tons, was stored at the Deseret Chemical Depot in northern Utah. The incineration of this stockpile began in 2006. In May 2011, the last of the mustard agents in the stockpile were incinerated at the Deseret Chemical Depot, and the last artillery shells containing mustard gas were incinerated in January 2012.

In 2008, many empty aerial bombs that contained mustard gas were found in an excavation at the Marrangaroo Army Base just west of Sydney, Australia.[71][72] In 2009, a mining survey near Chinchilla, Queensland, uncovered 144 105-millimeter howitzer shells, some containing "Mustard H", that had been buried by the U.S. Army during World War II.[72][73]

In 2014, a collection of 200 bombs was found near the Flemish villages of Passendale and Moorslede. The majority of the bombs were filled with mustard agents. The bombs were left over from the German army and were meant to be used in the Battle of Passchendaele in World War I. It was the largest collection of chemical weapons ever found in Belgium.[74]

A large amount of chemical weapons, including mustard gas, was found in a neighborhood of Washington, D.C. The cleanup was completed in 2021.[75]

Post-war accidental exposure

[edit]In 2002, an archaeologist at the Presidio Trust archaeology lab in San Francisco was exposed to mustard gas, which had been dug up at the Presidio of San Francisco, a former military base.[76]

In 2010, a clamming boat pulled up some old artillery shells of World War I from the Atlantic Ocean south of Long Island, New York. Multiple fishermen suffered from blistering and respiratory irritation severe enough to require hospitalization.[77]

WWII-era tests on men

[edit]

From 1943 to 1944, mustard agent experiments were performed on Australian service volunteers in tropical Queensland, Australia, by Royal Australian Engineers, British Army and American experimenters, resulting in some severe injuries. One test site, the Brook Islands National Park, was chosen to simulate Pacific islands held by the Imperial Japanese Army.[78][79] These experiments were the subject of the documentary film Keen as Mustard.[80]

The United States tested sulfur mustards and other chemical agents including nitrogen mustards and lewisite on up to 60,000 servicemen during and after WWII. The experiments were classified secret and as with Agent Orange[broken anchor], claims for medical care and compensation were routinely denied, even after the WWII-era tests were declassified in 1993. The Department of Veterans Affairs stated that it would contact 4,000 surviving test subjects but failed to do so, eventually only contacting 600. Skin cancer, severe eczema, leukemia, and chronic breathing problems plagued the test subjects, some of whom were as young as 19 at the time of the tests, until their deaths, but even those who had previously filed claims with the VA went without compensation.[81]

African American servicemen were tested alongside white men in separate trials to determine whether their skin color would afford them a degree of immunity to the agents, and Nisei servicemen, some of whom had joined after their release from Japanese American Internment Camps were tested to determine susceptibility of Japanese military personnel to these agents. These tests also included Puerto Rican subjects.[82]

Detection in biological fluids

[edit]Concentrations of thiodiglycol in urine have been used to confirm a diagnosis of chemical poisoning in hospitalized victims. The presence in urine of 1,1'-sulfonylbismethylthioethane (SBMTE), a conjugation product with glutathione, is considered a more specific marker, since this metabolite is not found in specimens from unexposed persons. In one case, intact mustard gas was detected in postmortem fluids and tissues of a man who died one week post-exposure.[83]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

- ^ a b c d e FM 3–8 Chemical Reference handbook, US Army, 1967

- ^ a b c d Mustard agents: description, physical and chemical properties, mechanism of action, symptoms, antidotes and methods of treatment. Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. Accessed June 8, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Mustard gas". PubChem, US National Library of Medicine. September 28, 2024. Retrieved October 4, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Mustard gas fact sheet". World Health Organization, Eastern Mediterranean Region, Regional Centre for Environmental Health Action. 2024. Retrieved October 4, 2024.

- ^ a b "Mustard gas". Online Etymology Dictionary. 2025. Retrieved July 3, 2025.

- ^ "What is a Chemical Weapon?". OPCW. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ Salouti R, Ghazavi R, Rajabi S, et al. (2020). "Sulfur Mustard and Immunology; Trends of 20 Years Research in the Web of Science Core Collection: A Scientometric Review". Iranian Journal of Public Health. 49 (7): 1202–1210. doi:10.18502/ijph.v49i7.3573. ISSN 2251-6085. PMC 7548481. PMID 33083286.

- ^ Watson AP, Griffin GD (1992). "Toxicity of vesicant agents scheduled for destruction by the Chemical Stockpile Disposal Program". Environmental Health Perspectives. 98: 259–280. Bibcode:1992EnvHP..98..259W. doi:10.1289/ehp.9298259. ISSN 0091-6765. PMC 1519623. PMID 1486858.

- ^ Smith SL (February 27, 2017). "War! What is it good for? Mustard gas medicine". CMAJ. 189 (8): E321 – E322. doi:10.1503/cmaj.161032. PMC 5325736. PMID 28246228.

- ^ a b Institute of Medicine (U.S.), Pechura CM, Rall DP, eds. (1993). Veterans at Risk: the health effects of mustard gas and Lewisite. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press. ISBN 978-0-309-04832-3.

- ^ Ghasemi H, Javadi MA, Ardestani SK, et al. (2020). "Alteration in inflammatory mediators in seriously eye-injured war veterans, long-term after sulfur mustard exposure". International Immunopharmacology. 80 105897. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2019.105897. ISSN 1878-1705. PMID 31685435. S2CID 207899509.

- ^ Ghazanfari T, Ghasemi H, Yaraee R, et al. (2019). "Tear and serum interleukin-8 and serum CX3CL1, CCL2 and CCL5 in sulfur mustard eye-exposed patients". International Immunopharmacology. 77 105844. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2019.105844. ISSN 1878-1705. PMID 31669888. S2CID 204967476.

- ^ Heidary F, Gharebaghi R, Ghasemi H, et al. (2019). "Angiogenesis modulatory factors in subjects with chronic ocular complications of Sulfur Mustard exposure: A case-control study". International Immunopharmacology. 76 105843. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2019.105843. ISSN 1878-1705. PMID 31629219. S2CID 204799405.

- ^ Heidary F, Ardestani SK, Ghasemi H, et al. (2019). "Alteration in serum levels of ICAM-1 and P-, E- and L-selectins in seriously eye-injured long-term following sulfur-mustard exposure". International Immunopharmacology. 76 105820. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2019.105820. ISSN 1878-1705. PMID 31480003. S2CID 201831881.

- ^ Safarinejad MR, Moosavi SA, Montazeri B (2001). "Ocular injuries caused by mustard gas: diagnosis, treatment, and medical defense". Military Medicine. 166 (1): 67–70. doi:10.1093/milmed/166.1.67. PMID 11197102.

- ^ Vesicants. brooksidepress.org

- ^ Najafi A, Masoudi-Nejad A, Imani Fooladi AA, et al. (2014). "Microarray gene expression analysis of the human airway in patients exposed to sulfur mustard". Journal of Receptors and Signal Transduction. 34 (4): 283–9. doi:10.3109/10799893.2014.896379. PMID 24823320. S2CID 41665583.

- ^ Ghasemi H, Javadi MA, Ardestani SK, et al. (2020). "Alteration in inflammatory mediators in seriously eye-injured war veterans, long-term after sulfur mustard exposure". International Immunopharmacology. 80 105897. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2019.105897. PMID 31685435. S2CID 207899509.

- ^ Geraci MJ (2008). "Mustard gas: imminent danger or eminent threat?". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 42 (2): 237–246. doi:10.1345/aph.1K445. ISSN 1542-6270. PMID 18212254. S2CID 207263000.

- ^ Dabrowska MI, Becks LL, Lelli JL Jr, et al. (1996). "Sulfur Mustard Induces Apoptosis and Necrosis in Endothelial Cells". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 141 (2): 568–83. Bibcode:1996ToxAP.141..568D. doi:10.1006/taap.1996.0324. PMID 8975783.

- ^ Van Bergen, Leo (2009). Before My Helpless Sight: Suffering, Dying and Military Medicine on the Western Front, 1914–1918. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-7546-5853-5.

- ^ Ghabili K, Agutter PS, Ghanei M, et al. (October 2010). "Mustard gas toxicity: the acute and chronic pathological effects". Journal of Applied Toxicology. 30 (7): 627–643. doi:10.1002/jat.1581. ISSN 0260-437X. PMID 20836142.

- ^ Stewart, Charles D. (2006). Weapons of mass casualties and terrorism response handbook. Boston: Jones and Bartlett. p. 47. ISBN 0-7637-2425-4.

- ^ "Chemical Weapons Production and Storage". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on August 11, 2014.

- ^ The Emergency Response Safety and Health Database: Mustard-Lewisite Mixture (HL). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Accessed March 19, 2009.

- ^ Gates M, Moore S (1946). "Mustard Gas and Other Sulfur Mustards". Chemical warfare agents, and related chemical problems. Washington, D.C. : Office of Scientific Research and Development, National Defense Research Committee, Division 9.

- ^ Frescoln LD (December 7, 1918). "Mustard (Yellow Cross) Burns". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 71 (23): 1911. doi:10.1001/jama.1918.26020490013010b. ISSN 0098-7484.

- ^ By Any Other Name: Origins of Mustard Gas Archived 2014-02-01 at the Wayback Machine. Itech.dickinson.edu (2008-04-25). Retrieved on 2011-05-29.

- ^ F. Guthrie (1860). "XIII.—On some derivatives from the olefines". Q. J. Chem. Soc. 12 (1): 109–126. doi:10.1039/QJ8601200109.

- ^ Duchovic, Ronald J., Vilensky, Joel A. (2007). "Mustard Gas: Its Pre-World War I History". J. Chem. Educ. 84 (6): 944. Bibcode:2007JChEd..84..944D. doi:10.1021/ed084p944.

- ^ Duchovic RJ, Vilensky JA (2007). "Mustard Gas: Its Pre-World War I History". Journal of Chemical Education. 84 (6): 944. Bibcode:2007JChEd..84..944D. doi:10.1021/ed084p944. ISSN 0021-9584.

- ^ Fries AA, West CJ (1921). Chemical warfare. University of California Libraries. New York [etc.] McGraw-Hill Book Company, inc. p. 176.

(...) on the night of July 12, 1917 (...)

- ^ Fries AA, West CJ (1921). Chemical warfare. University of California Libraries. New York [etc.] McGraw-Hill Book Company, inc. p. 150.

(...) 'Ypres,' a name used by the French, because the compound was first used at Ypres (...)

- ^ David Large (ed.). The Port of Bristol, 1848-1884.

- ^ "Photographic Archive of Avonmouth Bristol BS11". BristolPast.co.uk. Archived from the original on July 3, 2011. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ Fischer K (June 2004). Schattkowsky, Martina (ed.). Steinkopf, Georg Wilhelm, in: Sächsische Biografie (in German) (Online ed.). Institut für Sächsische Geschichte und Volkskunde. Retrieved December 28, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Blister Agent: Mustard gas (H, HD, HS) Archived July 24, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, CBWinfo.com

- ^ a b c d Pearson GS. "Uses of CW since the First World War". Federation of American Scientist. Archived from the original on August 22, 2010. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ Townshend C (1986). "Civilisation and "Frightfulness": Air Control in the Middle East Between the Wars". In Chris Wrigley (ed.). Warfare, diplomacy and politics: essays in honour of A.J.P. Taylor. Hamilton. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-241-11789-7.

- ^ a b Feakes D (2003). "Global society and biological and chemical weapons" (PDF). In Kaldor M, Anheier H, Glasius M (eds.). Global Civil Society Yearbook 2003. Oxford University Press. pp. 87–117. ISBN 0-19-926655-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 11, 2007.

- ^ Dickerson C (June 22, 2015). "Secret World War II Chemical Experiments Tested Troops By Race". NPR.

- ^ "NEWSLETTER - JUNE 1992 NEWSLETTER - Johannesburg - South African Military History Society - Title page". Samilitaryhistory.org. Retrieved August 23, 2013.

- ^ "The Tox Lab: When U Chicago Was in the Chemical Weapons "Business" | Newcity". September 23, 2013. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ K. Coleman (May 23, 2005). A History of Chemical Warfare. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 74–. ISBN 978-0-230-50183-6.

- ^ a b c Faguet GB (2005). The War on Cancer. Springer. p. 71. ISBN 1-4020-3618-3.

- ^ Lyon A (July 9, 2008). "Iran's Chemical Ali survivors still bear scars". Reuters. Retrieved November 17, 2008.

- ^ Benschop HP, van der Schans GP, Noort D, et al. (July 1, 1997). "Verification of Exposure to Sulfur Mustard in Two Casualties of the Iran-Iraq Conflict". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 21 (4): 249–251. doi:10.1093/jat/21.4.249. PMID 9248939.

- ^ "More Than 600 Reported Chemical Exposure in Iraq, Pentagon Acknowledges". The New York Times. November 6, 2014.

- ^ "Veterans Hurt by Chemical Weapons in Iraq Get Apology". The New York Times. March 25, 2015.

- ^ Deutsch A (February 15, 2016). "Samples confirm Islamic State used mustard gas in Iraq - diplomat". Reuters. Archived from the original on February 22, 2016. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

- ^ Deutsch A (November 6, 2015). "Chemical weapons used by fighters in Syria—sources". Reuters. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ^ "Syria war: IS 'used mustard gas' on Assad troops". BBC News. April 5, 2016. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ^ Paul Blake (September 11, 2015). "US official: 'IS making and using chemical weapons in Iraq and Syria'". BBC. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ^ Lizzie Dearden (September 11, 2015). "Isis 'manufacturing and using chemical weapons' in Iraq and Syria, US official claims". The Independent. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ^ Krumbhaar EB (1919). "Rôle of the blood and the bone marrow in certain forms of gas poisoning: I. peripheral blood changes and their significance". JAMA. 72: 39–41. doi:10.1001/jama.1919.26110010018009f.

- ^ a b Gilman A (May 1963). "The initial clinical trial of nitrogen mustard". Am. J. Surg. 105 (5): 574–8. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(63)90232-0. PMID 13947966.

- ^ Scott LJ (June 1, 2017). "Chlormethine 160 mcg/g gel in mycosis fungoides-type cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a profile of its use in the EU". Drugs & Therapy Perspectives. 33 (6): 249–253. doi:10.1007/s40267-017-0409-7. ISSN 1179-1977. S2CID 256367068.

- ^ The U.S. Army's Chemical Materials Agency (CMA) Archived October 15, 2004, at the Wayback Machine. cma.army.mil. Retrieved on November 11, 2011.

- ^ "U.S. destroys last of its declared chemical weapons, closing a deadly chapter dating to World War I". AP News. July 7, 2023. Retrieved April 11, 2025.

- ^ Sathe M, Srivastava S, Merwyn S, et al. (July 24, 2014). "Competitive immunochromatographic assay for the detection of thiodiglycol sulfoxide, a degradation product of sulfur mustard". The Analyst. 139 (20): 5118–26. Bibcode:2014Ana...139.5118S. doi:10.1039/C4AN00720D. PMID 25121638.

- ^ "Hill 70 & Cornwall's Deadly Mustard Gas Plant". Cornwall Community Museum. Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Historical Society. September 18, 2016. Retrieved December 23, 2016.

- ^ "Valley Factory, Rhydymwyn". July 24, 2010.

- ^ Bull J (October 30, 2005). "The Deadliness Below". Daily Press Virginia. Archived from the original on July 23, 2012. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ^ a b "India to destroy chemical weapons stockpile by 2009". Dominican Today. Archived from the original on September 7, 2013. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ^ Amy Smithson, Frank Gaffney Jr. "India declares its stock of chemical weapons". Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ^ "Zee News – India destroys its chemical weapons stockpile". Zeenews.india.com. May 14, 2009. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ^ "India destroys its chemical weapons stockpile - Yahoo! India News". Archived from the original on May 21, 2009. Retrieved May 20, 2009.

- ^ Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (November 30, 2016). "Annex 3". Report of the OPCW on the Implementation of the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on Their Destruction in 2015 (Report). p. 42. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ "CSEPP Background Information". US Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). May 2, 2006. Archived from the original on May 27, 2006.

- ^ "Milestones in U.S. Chemical Weapons Storage and Destruction, fact sheet, US Chemical Materials Agency". Archived from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved January 15, 2012.

- ^ Ashworth L (August 7, 2008). "Base's phantom war reveals its secrets". Fairfax Digital. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008.

- ^ a b Chemical Warfare in Australia. Mustardgas.org. Retrieved on 29 May 2011.

- ^ Cumming, Stuart (November 11, 2009). "Weapons await UN inspection". Toowoomba Chronicle.

- ^ "Farmer discovers 200 bombs (Dutch)". March 5, 2014.

- ^ "Cleanup Complete At WWI Chemical Weapons Dump In D.C.'s Spring Valley". DCist. Archived from the original on February 7, 2022. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ Sullivan, Kathleen (October 22, 2002). "Vial found in Presidio may be mustard gas / Army experts expected to identify substance". sfgate.com.

- ^ Wickett, Shana, Beth Daley (June 8, 2010). "Fishing crewman exposed to mustard gas from shell". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on June 9, 2010.

- ^ Goodwin B (1998). Keen as mustard: Britain's horrific chemical warfare experiments in Australia. St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press. ISBN 978-0-7022-2941-1.

- ^ Brook Island Trials of Mustard Gas during WW2. Home.st.net.au. Retrieved on 2011-05-29.

- ^ "Keen as mustard | Bridget Goodwin | 1989 | ACMI collection". www.acmi.net.au. Retrieved July 23, 2024.

- ^ Dickerson C (June 23, 2015). "The VA's Broken Promise To Thousands Of Vets Exposed To Mustard Gas". NPR. Retrieved May 3, 2019.

... the Department of Veterans Affairs made two promises: to locate about 4,000 men who were used in the most extreme tests, and to compensate those who had permanent injuries.

- ^ Dickerson C (June 22, 2015). "Secret World War II Chemical Experiments Tested Troops By Race". NPR. Retrieved May 3, 2019.

And it wasn't just African-Americans. Japanese-Americans were used [...] so scientists could explore how mustard gas and other chemicals might affect Japanese troops. Puerto Rican soldiers were also singled out.

- ^ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 10th edition, Biomedical Publications, Seal Beach, CA, 2014, pp. 1892–1894.

Further reading

[edit]- Cook T (2000). "'Against God-Inspired Conscience': The Perception of Gas Warfare as a Weapon of Mass Destruction, 1915–1939". War & Society. 18 (1): 47–69. doi:10.1179/072924700791201379.

- Dorsey MG (2023). Holding Their Breath: How the Allies Confronted the Threat of Chemical Warfare in World War II. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-6838-5. Retrieved September 1, 2025.

- Duchovic RJ, Vilensky JA (2007). "Mustard gas: its pre-World War I history" (PDF). Journal of Chemical Education. 84 (6): 944. Bibcode:2007JChEd..84..944D. doi:10.1021/ed084p944. Retrieved September 1, 2025.

- Feister AJ (1991). Medical Defense Against Mustard Gas: Toxic Mechanisms and Pharmacological Implications. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-4257-8. Retrieved September 1, 2025.

- Fitzgerald GJ (2008). "Chemical warfare and medical response during World War I". American Journal of Public Health. 98 (4): 611–625. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.111930. PMID 18356568. Retrieved September 1, 2025.

- Freemantle M (2012). Gas! GAS! Quick, boys! How Chemistry Changed the First World War. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-6601-9.

- Geraci MJ (2008). "Mustard gas: imminent danger or eminent threat?". Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 42 (2): 237–246. doi:10.1345/aph.1K445. PMID 18212254. Retrieved September 1, 2025.

- Ghabili K, Ghanei M, Zarei A, et al. (2010). "Mustard gas toxicity: the acute and chronic pathological effects". Journal of Applied Toxicology. 30 (7): 627–643. doi:10.1002/jat.1581. PMID 20836142. Retrieved September 1, 2025.

- Jones E (2014). "Terror weapons: The British experience of gas and its treatment in the First World War". War in History. 21 (3): 355–375. doi:10.1177/0968344513510248. PMC 5131841. PMID 27917027.

- MacPherson WG, Herringham WP, Elliott TR, et al. (1923). Medical Services: Diseases of the War: Including the Medical Aspects of Aviation and Gas Warfare and Gas Poisoning in Tanks and Mines. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents. Vol. II. London: HMSO. OCLC 769752656. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- Padley AP (2016). "Gas: the greatest terror of the Great War". Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. 44 (1_suppl): 24–30. doi:10.1177/0310057X1604401S05. PMID 27456288. Retrieved September 1, 2025.

- Rall DP, Pechura CM, eds. (1993). Veterans at Risk: The Health Effects of Mustard Gas and Lewisite (PDF). National Academies Press. Bibcode:1993nap..book.2058I. Retrieved September 1, 2025.

- Richter D (1994). Chemical Soldiers. Leo Cooper. ISBN 0850523885.

- Schummer J (2021). "Ethics of chemical weapons research: Poison gas in World War One" (PDF). Ethics of Chemistry: From Poison Gas to Climate Engineering: 55–83. doi:10.1142/9789811233548_0003. ISBN 978-981-12-3353-1. Retrieved September 1, 2025.

- Smith SI (2017). Toxic Exposures: Mustard Gas and the Health Consequences of World War II in the United States. Rutgers University Press. Retrieved September 1, 2025.

- Wattana M, Bey T (2009). "Mustard gas or sulfur mustard: an old chemical agent as a new terrorist threat". Prehospital and Disaster Medicine. 24 (1): 19–29. doi:10.1017/S1049023X0000649X. PMID 19557954. Retrieved September 1, 2025.

- Jackson KE (December 1934). "β,β' Dichloroethyl Sulfide (Mustard Gas)". Chemical Reviews. 15 (3): 425–462. doi:10.1021/cr60052a004. ISSN 0009-2665.

External links

[edit]- Mustard gas (Sulphur Mustard) (IARC Summary & Evaluation, Supplement7, 1987). Inchem.org (1998-02-09). Retrieved on 2011-05-29.

- Institute of Medicine (1993). "History and Analysis of Mustard Agent and Lewisite Research Programs in the United States". Veterans at Risk: The Health Effects of Mustard Gas and Lewisite. National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-04832-3.

- Textbook of Military Medicine – Intensive overview of mustard gas Includes many references to scientific literature

- Detailed information on physical effects and suggested treatments

- Iyriboz Y (2004). "A Recent Exposure to Mustard Gas in the United States: Clinical Findings of a Cohort (n = 247) 6 Years After Exposure". MedGenMed. 6 (4): 4. PMC 1480580. PMID 15775831. Shows photographs taken in 1996 showing people with mustard gas burns.

- UMDNJ-Rutgers University CounterACT Research Center of Excellence A research center studying mustard gas, includes searchable reference library with many early references on mustard gas.

- Clayton W, Howard AJ, Thomson D (May 25, 1946). "Treatment of Mustard Gas Burns". British Medical Journal. 1 (4455): 797–799. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.4455.797. PMC 2058956. PMID 20786722.

- surgical treatment of mustard gas burns

- UK Ministry of Defence Report on disposal of weapons at sea and incidents arising

Mustard gas

View on GrokipediaChemical Properties and Synthesis

Molecular Structure and Formula

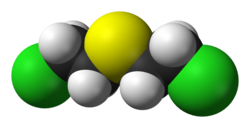

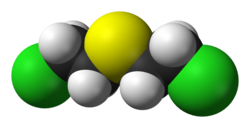

Sulfur mustard, commonly known as mustard gas, has the molecular formula C₄H₈Cl₂S.[1] This corresponds to a molecular weight of 159.08 g/mol.[9] The compound is an organosulfur molecule classified as a thioether, featuring a central sulfur atom covalently bonded to two 2-chloroethyl groups.[1] The IUPAC name for sulfur mustard is 1-chloro-2-(2-chloroethylsulfanyl)ethane, though it is more commonly referred to by its systematic synonym bis(2-chloroethyl) sulfide.[9] In structural terms, the molecule can be represented as Cl-CH₂-CH₂-S-CH₂-CH₂-Cl, where the sulfur atom serves as the linking bridge between the two chlorinated alkyl chains.[1] This configuration imparts lipophilic properties, contributing to its persistence and ability to penetrate biological barriers.[10] The Lewis structure highlights the tetrahedral geometry around the sulfur atom, with bond angles approximating 109 degrees due to the presence of lone pairs on sulfur.[1] In skeletal formula depictions, the chlorine atoms terminate the ethyl chains, emphasizing the symmetric nature of the molecule.[1] Sulfur mustard exists primarily in its undissociated form under standard conditions, with no significant ionization due to the absence of acidic protons.[9]Physical and Chemical Characteristics

Sulfur mustard, with the chemical formula C₄H₈Cl₂S and systematic name bis(2-chloroethyl) sulfide, is a viscous oily liquid at ambient temperatures, exhibiting low volatility due to its vapor pressure of approximately 0.1 mmHg at 25 °C.[11][10] It appears as a clear to pale yellow or amber-colored substance, though impure forms may darken to black, and possesses a molecular weight of 159.08 g/mol.[11][12] The compound emits a faint odor reminiscent of garlic, mustard, or horseradish, with an air odor threshold of 0.6 mg/m³.[11][12]| Property | Value | Conditions/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Melting point | 13–14 °C | [11][10] |

| Boiling point | 217.5 °C | [11][10] |

| Density | 1.2685–1.338 g/cm³ | 13–25 °C [11][10] |

| Water solubility | 0.684–0.92 g/L | 22–25 °C [11][10] |

| Vapor pressure | 0.082–0.106 mmHg | 22–25 °C [11][10] |

Methods of Synthesis

The Levinstein process, developed during World War I, represents the primary method for large-scale production of bis(2-chloroethyl) sulfide (mustard gas). In this approach, ethylene gas is passed through liquid sulfur monochloride (S₂Cl₂) at temperatures of 30–60 °C, resulting in the exothermic reaction: 2 C₂H₄ + S₂Cl₂ → (ClCH₂CH₂)₂S + SCl₂, though side reactions produce impurities such as polysulfides and thiodiglycol.[15] The crude product requires distillation under reduced pressure to achieve purity levels of 80–96%, with yields typically around 70–80% based on sulfur monochloride consumption. This method was favored by Allied forces for its simplicity and use of readily available precursors, despite generating toxic byproducts like hydrogen chloride gas. In contrast, the Meyer process, utilized by German forces in World War I, involves a two-stage synthesis via thiodiglycol as an intermediate. Ethylene is first treated with hypochlorous acid to form 2-chloroethanol (ClCH₂CH₂OH), which reacts with aqueous sodium sulfide (Na₂S) to yield thiodiglycol ((HOCH₂CH₂)₂S); the diol is then chlorinated using hydrochloric acid or phosphorus oxychloride (POCl₃) at elevated temperatures to produce bis(2-chloroethyl) sulfide.[16] This route allows for higher purity after fractional distillation but requires more steps and handling of aqueous intermediates, limiting throughput compared to the Levinstein method.[16] Post-World War I refinements, including direct chlorination of thiodiglycol with anhydrous HCl or thionyl chloride in the presence of catalysts, enable production of distillation-grade mustard gas (>96% purity) suitable for munitions filling.[17] These methods exploit thiodiglycol's stability and are monitored under chemical weapons conventions due to its role as a key precursor.[17] Laboratory-scale syntheses, such as those originally described by Victor Meyer in 1886 involving ethanol and sulfur dichloride, are less relevant to industrial contexts but confirm the compound's reactivity with nucleophilic sulfur centers.[18] All routes necessitate stringent safety measures owing to the agent's volatility, lachrymatory effects, and alkylating toxicity even at trace levels.[19]Etymology and Nomenclature

Origins of the Name

The designation "mustard gas" for sulfur mustard (bis(2-chloroethyl) sulfide) arose during World War I from its pungent odor, which Allied soldiers likened to mustard, garlic, or horseradish, particularly noticeable at concentrations above 0.0007 mg/m³.[20][2] This sensory association prompted the informal naming by troops encountering the agent, first deployed by German forces on July 12, 1917, near Ypres, Belgium.[20] Despite the moniker, sulfur mustard is not a gas but a volatile, amber-colored liquid at room temperature (boiling point 217°C), which vaporizes slowly to form an aerosol or vapor cloud under battlefield dispersal conditions, such as artillery shells or projectors.[2] The "gas" suffix reflected early 20th-century chemical warfare terminology for inhaled irritants, akin to chlorine or phosgene, rather than precise physical state.[20] German forces referred to it as Lost (from the English "lost" or possibly a code), while the French called it yiprite after Ypres, but the English "mustard gas" term persisted in Allied documentation and entered widespread use post-war.[20]Synonyms and Classifications

Mustard gas, chemically bis(2-chloroethyl) sulfide with the molecular formula C₄H₈Cl₂S, is systematically named 1-chloro-2-(2-chloroethylsulfanyl)ethane according to IUPAC nomenclature.[1] Common synonyms include sulfur mustard, the preferred term in scientific and toxicological contexts to distinguish it from nitrogen mustards; mustard agent; and dichloroethyl sulfide.[10] Military designations are H for the crude, unrefined form and HD for the distilled, purified variant, reflecting differences in purity and stability.[10] [14] The name yperite derives from its first large-scale deployment near Ypres, Belgium, in 1917.[21] As a chemical warfare agent, it is classified as a vesicant or blister agent due to its mechanism of inducing delayed, severe burns and blistering on skin, eyes, and mucous membranes via alkylation of cellular components, including DNA cross-linking.[14] [1] Chemically, it falls under organosulfur compounds, specifically thioethers, and functions as an alkylating agent capable of reacting with nucleophilic sites in biological molecules.[1] Under the United Nations' Globally Harmonized System (GHS), it is designated for acute toxicity (categories 2-3 via inhalation, dermal, and ocular routes), skin corrosion (category 1A), serious eye damage (category 1), germ cell mutagenicity (category 1B), and carcinogenicity (category 1A), with additional hazards for specific target organ toxicity and aquatic acute toxicity.[22] It is a Schedule 1 substance under the Chemical Weapons Convention, banning its development, production, and stockpiling except for limited research or protective purposes.[23] The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classifies it as a Group 1 carcinogen based on sufficient evidence of lung cancer in humans from occupational exposures.[24]Historical Development

Pre-World War I Research

In 1822, French chemist César-Mansuète Despretz first prepared an impure form of sulfur mustard (bis(2-chloroethyl) sulfide) by reacting ethylene with sulfur dichloride, though he reported no notable irritating properties and did not isolate the pure compound.[25] Subsequent 19th-century chemists refined synthesis techniques amid advancing understanding of organic sulfur compounds, but early efforts yielded low-purity products unsuitable for detailed study.[26] By 1860, British chemist Frederick Guthrie achieved a more defined preparation by chlorinating ethyl disulfide, generating vapors that caused acute blistering, intense pain, and inflammation on exposed skin and eyes; he likened the effects to an exaggerated mustard poultice, marking the first documented recognition of its vesicant potency.[27] Guthrie's observations, published in chemical journals, highlighted the substance's ability to penetrate clothing and persist as an oily liquid, but lacked quantitative toxicity data or medical analysis. In 1886, German chemist Viktor Meyer developed an efficient synthesis route using ethylene and sulfur monochloride, producing higher yields of the compound.[18] To verify purity, Meyer inhaled its vapors, experiencing immediate eye irritation, temporary blindness, severe bronchitis, and pulmonary edema; these personal experiments revealed its delayed-onset respiratory toxicity but exacerbated his chronic health decline, contributing to his suicide in 1897 at age 48.[18] Pre-1914 research remained confined to academic laboratories, focusing on structural elucidation and incidental physiological effects rather than therapeutic or military applications, with no evidence of scaled production or weaponization attempts.[26]World War I Innovation and Deployment

![German demonstration of Yperite mustard gas][float-right] The German chemical warfare program during World War I, directed by chemist Fritz Haber, sought agents that could overcome the stalemate of trench warfare following the initial use of chlorine and phosgene gases. Sulfur mustard, a vesicant agent known for its blistering effects and persistence in the environment, was developed as part of this effort to deny terrain to Allied forces and cause prolonged casualties without immediate lethality. Although Haber expressed reservations about its deployment due to the lack of effective German defenses, the agent was weaponized through industrial-scale production involving reactions of ethylene with sulfur monochloride.[28][29] Sulfur mustard was first deployed by the German Fourth Army on the night of July 12-13, 1917, near Ypres, Belgium, during preparations for the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele). Delivered via artillery shells marked with yellow crosses for identification, approximately 50,000 rounds containing the agent were fired at British positions held by the 40th Division. The attack exploited the agent's oily liquid form, which vaporized slowly and contaminated soil and equipment for days, creating hazardous zones that hindered troop movements and required extensive decontamination.[30][31] The initial deployment inflicted over 2,100 casualties, primarily through delayed onset of symptoms including severe skin blisters, eye inflammation, and respiratory tract damage, which incapacitated soldiers for weeks. In the subsequent three weeks, British casualty clearing stations recorded around 14,000 gas-related admissions, the majority attributable to mustard exposure, marking a shift toward persistent agents that prioritized morbidity over mortality. By late 1917, German production reached 1,000 tons monthly, enabling widespread use that accounted for roughly 80% of remaining chemical casualties in the war, though overall gas fatalities remained under 5% of total deaths due to protective measures like masks. Allied forces began retaliatory use by August 1918, but German innovation maintained a tactical edge throughout.[31][30][4]Military Applications

World War I Usage

The German army first deployed sulfur mustard on the night of July 12–13, 1917, during the Third Battle of Ypres, targeting Allied positions near Ypres, Belgium, in an operation known as "Totentanz" or "Dance of Death."[30] Delivered via artillery shells marked with yellow crosses, the agent contaminated ground areas with persistent liquid droplets, causing severe blistering, temporary blindness, and respiratory damage that manifested hours after exposure.[31] This initial barrage inflicted approximately 6,400 casualties in the Armentières sector alone, exploiting the limitations of existing gas masks which primarily protected against inhalation but not skin contact.[30] Mustard gas proved particularly effective due to its vesicant properties and low volatility, allowing it to persist in craters and trenches, denying areas to troops for days and complicating offensive operations.[32] By late 1917, German production scaled to thousands of tons, with artillery shells comprising the primary delivery method, supplemented later by aerial bombs.[33] The agent accounted for the majority of chemical casualties after its introduction, contributing to nearly 400,000 total mustard-related injuries across the war, far exceeding those from chlorine or phosgene due to its incapacitating rather than immediately lethal effects.[24] British forces reported over 160,000 gas casualties, with mustard responsible for a significant portion after 1917.[34] In retaliation, Allied forces, initially caught unprepared, accelerated production and first employed mustard gas in August 1918 during the Hundred Days Offensive, using similar shell-based tactics and Livens projectors for concentrated releases.[32] Countermeasures evolved with the introduction of protective ointments and improved small-box respirators, though decontamination remained challenging, as mustard hydrolyzed slowly in soil and water.[35] Overall, chemical weapons, dominated by mustard after mid-1917, caused about 1.3 million casualties and 90,000 deaths, with mustard's role underscoring its tactical value in attrition warfare despite international prohibitions like the 1899 Hague Declaration.[31]Interwar Period and World War II Employment

In the interwar period, the 1925 Geneva Protocol, which prohibited the use of chemical weapons in warfare, failed to prevent deployments by signatory states. Italy extensively employed mustard gas during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War from October 1935 to May 1936, primarily via aerial delivery against Ethiopian troops and civilian populations lacking protective equipment; estimates indicate around 15,000 chemical casualties from mustard and other agents.[36][37] This marked the first large-scale use of mustard gas since World War I, with Italian forces dropping over 300 tons of chemical munitions, including sulfur mustard, to overcome Ethiopian resistance in rugged terrain.[38] During World War II, all major belligerents—Germany, the Allies, and Japan—maintained substantial stockpiles of mustard gas, with production ramping up despite the Geneva Protocol's constraints on use (which did not extend to possession or development); for instance, the United States alone produced over 144,000 tons of chemical agents by 1945, including mustard variants.[39] However, mutual deterrence prevented widespread battlefield employment in Europe and against Western forces in the Pacific, as leaders on both sides anticipated devastating retaliation; Adolf Hitler, personally scarred by mustard exposure in World War I, explicitly refrained from initiating chemical attacks despite Allied bombing campaigns.[40] Japan, however, violated the Protocol by deploying mustard gas against Chinese Nationalists and Communists in multiple campaigns, such as the 1941 Zhejiang-Jiangxi offensive and the 1943 Battle of Changde, where artillery shells containing mustard inflicted severe blistering injuries on exposed troops.[41] In the 1944 Hengyang encirclement, Japanese forces fired numerous gas shells incorporating mustard and lewisite, contributing to high non-combat incapacitation rates among Chinese defenders amid broader atrocities.[42] These uses, totaling thousands of tons of chemical agents expended by Japan's Unit 731 and field armies, targeted poorly equipped adversaries but ceased against American-led forces due to anticipated reprisals.[43]Post-1945 Conflicts and Allegations

Egyptian forces deployed sulfur mustard during the North Yemen Civil War from 1963 to 1967, marking the first confirmed postwar use of the agent in combat.[24] [44] Egyptian aircraft bombed royalist positions and villages with mustard gas canisters, resulting in blisters, respiratory distress, and an estimated 1,500 casualties among Yemeni fighters and civilians.[45] Investigations by Swedish and British medical teams in 1967 confirmed mustard gas residues in soil samples and matched victim symptoms to the agent's vesicant effects, though Egypt denied the allegations at the time.[45] [46] Iraq employed sulfur mustard extensively during the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988), initiating chemical attacks as early as 1983 against Iranian troops.[47] By 1984, Iraq had used mustard gas in over 30 documented assaults, often delivered via artillery shells and aerial bombs, causing tens of thousands of Iranian casualties including severe skin blistering, eye damage, and pulmonary edema. United Nations fact-finding missions in 1984 and 1986 verified mustard agent presence through clinical examinations and environmental sampling, estimating that chemical weapons, predominantly mustard, accounted for up to 20% of Iranian battlefield deaths.[48] Iraq's program produced over 3,500 tons of mustard agent during the conflict, with use escalating in 1988 against Kurdish civilians in Halabja alongside nerve agents, though mustard predominated in earlier phases.[47][49] In the Syrian Civil War, the Islamic State (ISIS) used sulfur mustard in an August 2015 attack on the rebel-held town of Marea, contaminating up to 25 individuals with symptoms including skin burns and ocular irritation.[50] The Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) Fact-Finding Mission analyzed samples and victim accounts, confirming with high confidence that ISIS deployed an improvised mustard device, likely artillery rounds filled with the agent synthesized from commercially available precursors.[50] [51] Separate allegations of Syrian government mustard use surfaced in 2015-2016, but OPCW investigations attributed confirmed blister agent incidents primarily to non-state actors like ISIS rather than regime forces, which favored chlorine and sarin.[52] No large-scale state uses of mustard have been verified since the 1980s, though remnant Iraqi stockpiles exposed U.S. troops to low-level mustard degradation products during the 2003 invasion, without active deployment.[53]Formulations and Variants

Sulfur Mustard Types

Sulfur mustards encompass several formulations of bis(2-chloroethyl) sulfide, the prototypical vesicant agent, distinguished primarily by purity, production method, and additives for operational enhancements. The crude Levinstein mustard, designated H or HS, results from the reaction of ethylene with sulfur monochloride at 30–50°C, yielding a dark-brown liquid containing 20–30% impurities such as sesquimustard and other polysulfides that contribute to its instability and higher toxicity per unit weight compared to purified forms.[1][16] This variant, developed during World War I, freezes at approximately -2°C and was widely deployed due to its rapid production despite the impurities exacerbating long-term storage degradation.[54] Distilled mustard, coded HD, is a purified derivative obtained by vacuum distillation and washing of Levinstein mustard, achieving 95–99% purity as a colorless to amber oily liquid with a freezing point of 14–16°C and vapor pressure of 0.11 mmHg at 20°C.[1][54] This form exhibits greater persistence on surfaces (lasting days under ambient conditions) and reduced impurity-related side reactions, rendering it preferable for post-World War I stockpiles and deployments.[55] HD's alkylating reactivity remains identical to H, targeting DNA via guanine N7 sites, but its stability minimizes unintended polymerization during handling.[1] HT represents a binary mixture of 60% HD and 40% agent T (O-mustard, chemically bis(2-chloroethylthioethyl) ether, ClCH₂CH₂SCH₂CH₂OCH₂CH₂SCH₂CH₂Cl), engineered to depress the freezing point to 0–1°C for arctic operations while reducing volatility (vapor pressure ~0.05 mmHg at 20°C) and enhancing persistence beyond HD alone.[1][54] Agent T itself is a difunctional vesicant with comparable blistering potency to HD but lower vapor hazard, and its inclusion in HT mitigates phase separation risks in munitions.[56] Sesquimustard (Q, 1,1'-thiobis(2-chloroethane)), a common impurity in H (up to 10–20%), features the formula (ClCH₂CH₂S)₂CH₂ and exhibits approximately fivefold greater vesicant activity due to its solid state at room temperature (melting point 35–36°C) and enhanced lipophilicity, though it was not independently weaponized.[57]| Type | Composition/Purity | Key Properties | Historical Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| H (Levinstein) | ~70–80% bis(2-chloroethyl) sulfide + impurities (e.g., sesquimustard) | Freezing point -2°C; dark liquid; less stable | World War I production priority for volume[54] |

| HD (Distilled) | 95–99% pure bis(2-chloroethyl) sulfide | Freezing point 14–16°C; amber liquid; higher purity reduces degradation | Post-1918 stockpiles; standard for later conflicts[58] |

| HT | 60% HD + 40% O-mustard (agent T) | Freezing point 0–1°C; lower volatility; increased persistence | Cold-weather munitions adaptation[54] |