Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pressure measurement

View on Wikipedia

Pressure measurement is the measurement of an applied force by a fluid (liquid or gas) on a surface. Pressure is typically measured in units of force per unit of surface area. Many techniques have been developed for the measurement of pressure and vacuum. Instruments used to measure and display pressure mechanically are called pressure gauges, vacuum gauges or compound gauges (vacuum & pressure). The widely used Bourdon gauge is a mechanical device, which both measures and indicates and is probably the best known type of gauge.

A vacuum gauge is used to measure pressures lower than the ambient atmospheric pressure, which is set as the zero point, in negative values (for instance, −1 bar or −760 mmHg equals total vacuum). Most gauges measure pressure relative to atmospheric pressure as the zero point, so this form of reading is simply referred to as "gauge pressure". However, anything greater than total vacuum is technically a form of pressure. For very low pressures, a gauge that uses total vacuum as the zero point reference must be used, giving pressure reading as an absolute pressure.

Other methods of pressure measurement involve sensors that can transmit the pressure reading to a remote indicator or control system (telemetry).

Absolute, gauge and differential pressures — zero reference

[edit]

Everyday pressure measurements, such as for vehicle tire pressure, are usually made relative to ambient air pressure. In other cases measurements are made relative to a vacuum or to some other specific reference. When distinguishing between these zero references, the following terms are used:

- Absolute pressure is zero-referenced against a perfect vacuum, using an absolute scale, so it is equal to gauge pressure plus atmospheric pressure. Absolute pressure sensors are used in applications where a constant reference is required, like for example, high-performance industrial applications such as monitoring vacuum pumps, liquid pressure measurement, industrial packaging, industrial process control and aviation inspection.[1]

- Gauge pressure is zero-referenced against ambient air pressure, so it is equal to absolute pressure minus atmospheric pressure. A tire pressure gauge is an example of gauge pressure measurement; when it indicates zero, then the pressure it is measuring is the same as the ambient pressure. Most sensors for measuring up to 50 bar are manufactured in this way, since otherwise the atmospheric pressure fluctuation (weather) is reflected as an error in the measurement result.

- Differential pressure is the difference in pressure between two points. Differential pressure sensors are used to measure many properties, such as pressure drops across oil filters or air filters, fluid levels (by comparing the pressure above and below the liquid) or flow rates (by measuring the change in pressure across a restriction). Technically speaking, most pressure sensors are really differential pressure sensors; for example a gauge pressure sensor is merely a differential pressure sensor in which one side is open to the ambient atmosphere. A DP cell is a device that measures the differential pressure between two inputs.[2]

The zero reference in use is usually implied by context, and these words are added only when clarification is needed. Tire pressure and blood pressure are gauge pressures by convention, while atmospheric pressures, deep vacuum pressures, and altimeter pressures must be absolute.

For most working fluids where a fluid exists in a closed system, gauge pressure measurement prevails. Pressure instruments connected to the system will indicate pressures relative to the current atmospheric pressure. The situation changes when extreme vacuum pressures are measured, then absolute pressures are typically used instead and measuring instruments used will be different.

Differential pressures are commonly used in industrial process systems. Differential pressure gauges have two inlet ports, each connected to one of the volumes whose pressure is to be monitored. In effect, such a gauge performs the mathematical operation of subtraction through mechanical means, obviating the need for an operator or control system to watch two separate gauges and determine the difference in readings.

Moderate vacuum pressure readings can be ambiguous without the proper context, as they may represent absolute pressure or gauge pressure without a negative sign. Thus a vacuum of 26 inHg gauge is equivalent to an absolute pressure of 4 inHg, calculated as 30 inHg (typical atmospheric pressure) − 26 inHg (gauge pressure).

Atmospheric pressure is typically about 100 kPa at sea level, but is variable with altitude and weather. If the absolute pressure of a fluid stays constant, the gauge pressure of the same fluid will vary as atmospheric pressure changes. For example, when a car drives up a mountain, the (gauge) tire pressure goes up because atmospheric pressure goes down. The absolute pressure in the tire is essentially unchanged.

Using atmospheric pressure as reference is usually signified by a "g" for gauge after the pressure unit, e.g. 70 psig, which means that the pressure measured is the total pressure minus atmospheric pressure. There are two types of gauge reference pressure: vented gauge (vg) and sealed gauge (sg).

A vented-gauge pressure transmitter, for example, allows the outside air pressure to be exposed to the negative side of the pressure-sensing diaphragm, through a vented cable or a hole on the side of the device, so that it always measures the pressure referred to ambient barometric pressure. Thus a vented-gauge reference pressure sensor should always read zero pressure when the process pressure connection is held open to the air.

A sealed gauge reference is very similar, except that atmospheric pressure is sealed on the negative side of the diaphragm. This is usually adopted on high pressure ranges, such as hydraulics, where atmospheric pressure changes will have a negligible effect on the accuracy of the reading, so venting is not necessary. This also allows some manufacturers to provide secondary pressure containment as an extra precaution for pressure equipment safety if the burst pressure of the primary pressure sensing diaphragm is exceeded.

There is another way of creating a sealed gauge reference, and this is to seal a high vacuum on the reverse side of the sensing diaphragm. Then the output signal is offset, so the pressure sensor reads close to zero when measuring atmospheric pressure.

A sealed gauge reference pressure transducer will never read exactly zero because atmospheric pressure is always changing and the reference in this case is fixed at 1 bar.

To produce an absolute pressure sensor, the manufacturer seals a high vacuum behind the sensing diaphragm. If the process-pressure connection of an absolute-pressure transmitter is open to the air, it will read the actual barometric pressure.

A sealed pressure sensor is similar to a gauge pressure sensor except that it measures pressure relative to some fixed pressure rather than the ambient atmospheric pressure (which varies according to the location and the weather).

History

[edit]For much of human history, the pressure of gases like air was ignored, denied, or taken for granted, but as early as the 6th century BC, Greek philosopher Anaximenes of Miletus claimed that all things are made of air that is simply changed by varying levels of pressure. He could observe water evaporating, changing to a gas, and felt that this applied even to solid matter. More condensed air made colder, heavier objects, and expanded air made lighter, hotter objects. This was akin to how gases really do become less dense when warmer, more dense when cooler.

In the 17th century, Evangelista Torricelli conducted experiments with mercury that allowed him to measure the presence of air. He would dip a glass tube, closed at one end, into a bowl of mercury and raise the closed end up out of it, keeping the open end submerged. The weight of the mercury would pull it down, leaving a partial vacuum at the far end. This validated his belief that air/gas has mass, creating pressure on things around it. Previously, the more popular conclusion, even for Galileo, was that air was weightless and it is vacuum that provided force, as in a siphon. The discovery helped bring Torricelli to the conclusion:

We live submerged at the bottom of an ocean of the element air, which by unquestioned experiments is known to have weight.

This test, known as Torricelli's experiment, was essentially the first documented pressure gauge.

Blaise Pascal went further, having his brother-in-law try the experiment at different altitudes on a mountain, and finding indeed that the farther down in the ocean of atmosphere, the higher the pressure.

Units

[edit]| Pascal | Bar | Technical atmosphere | Standard atmosphere | Torr | Pound per square inch | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Pa) | (bar) | (at) | (atm) | (Torr) | (psi) | |

| 1 Pa | — | 10−5 bar | 1.0197×10−5 at | 9.8692×10−6 atm | 7.5006×10−3 Torr | 0.000145037737730 lbf/in2 |

| 1 bar | 105 | — | = 1.0197 | = 0.98692 | = 750.06 | = 14.503773773022 |

| 1 at | 98066.5 | 0.980665 | — | 0.9678411053541 | 735.5592401 | 14.2233433071203 |

| 1 atm | ≡ 101325 | ≡ 1.01325 | 1.0332 | — | ≡ 760 | 14.6959487755142 |

| 1 Torr | 133.322368421 | 0.001333224 | 0.00135951 | 1/760 ≈ 0.001315789 | — | 0.019336775 |

| 1 psi | 6894.757293168 | 0.068947573 | 0.070306958 | 0.068045964 | 51.714932572 | — |

The SI unit for pressure is the pascal (Pa), equal to one newton per square metre (N·m−2 or kg·m−1·s−2). This special name for the unit was added in 1971; before that, pressure in SI was expressed in units such as N·m−2. When indicated, the zero reference is stated in parentheses following the unit, for example 101 kPa (abs). The pound per square inch (psi) is still in widespread use in the US and Canada, for measuring, for instance, tire pressure. A letter is often appended to the psi unit to indicate the measurement's zero reference; psia for absolute, psig for gauge, psid for differential, although this practice is discouraged by the NIST.[3]

Because pressure was once commonly measured by its ability to displace a column of liquid in a manometer, pressures are often expressed as a depth of a particular fluid (e.g., inches of water). Manometric measurement is the subject of pressure head calculations. The most common choices for a manometer's fluid are mercury (Hg) and water; water is nontoxic and readily available, while mercury's density allows for a shorter column (and so a smaller manometer) to measure a given pressure. The abbreviation "W.C." or the words "water column" are often printed on gauges and measurements that use water for the manometer.

Fluid density and local gravity can vary from one reading to another depending on local factors, so the height of a fluid column does not define pressure precisely. So measurements in "millimetres of mercury" or "inches of mercury" can be converted to SI units as long as attention is paid to the local factors of fluid density and gravity. Temperature fluctuations change the value of fluid density, while location can affect gravity.

Although no longer preferred, these manometric units are still encountered in many fields. Blood pressure is measured in millimetres of mercury (see torr) in most of the world, central venous pressure and lung pressures in centimeters of water are still common, as in settings for CPAP machines. Natural gas pipeline pressures are measured in inches of water, expressed as "inches W.C."

Underwater divers use manometric units: the ambient pressure is measured in units of metres sea water (msw) which is defined as equal to one tenth of a bar.[4][5] The unit used in the US is the foot sea water (fsw), based on standard gravity and a sea-water density of 64 lb/ft3. According to the US Navy Diving Manual, one fsw equals 0.30643 msw, 0.030643 bar, or 0.44444 psi,[4][5] though elsewhere it states that 33 fsw is 14.7 psi (one atmosphere), which gives one fsw equal to about 0.445 psi.[6] The msw and fsw are the conventional units for measurement of diver pressure exposure used in decompression tables and the unit of calibration for pneumofathometers and hyperbaric chamber pressure gauges.[7] Both msw and fsw are measured relative to normal atmospheric pressure.

In vacuum systems, the units torr (millimeter of mercury), micron (micrometer of mercury),[8] and inch of mercury (inHg) are most commonly used. Torr and micron usually indicates an absolute pressure, while inHg usually indicates a gauge pressure.

Atmospheric pressures are usually stated using hectopascal (hPa), kilopascal (kPa), millibar (mbar) or atmospheres (atm). In American and Canadian engineering, stress is often measured in kip. Stress is not a true pressure since it is not scalar. In the cgs system the unit of pressure was the barye (ba), equal to 1 dyn·cm−2. In the mts system, the unit of pressure was the pieze, equal to 1 sthene per square metre.

Many other hybrid units are used such as mmHg/cm2 or grams-force/cm2 (sometimes as kg/cm2 without properly identifying the force units). Using the names kilogram, gram, kilogram-force, or gram-force (or their symbols) as a unit of force is prohibited in SI; the unit of force in SI is the newton (N).

Static and dynamic pressure

[edit]Static pressure is uniform in all directions, so pressure measurements are independent of direction in an immovable (static) fluid. Flow, however, applies additional pressure on surfaces perpendicular to the flow direction, while having little impact on surfaces parallel to the flow direction. This directional component of pressure in a moving (dynamic) fluid is called dynamic pressure. An instrument facing the flow direction measures the sum of the static and dynamic pressures; this measurement is called the total pressure or stagnation pressure. Since dynamic pressure is referenced to static pressure, it is neither gauge nor absolute; it is a differential pressure.

While static gauge pressure is of primary importance to determining net loads on pipe walls, dynamic pressure is used to measure flow rates and airspeed. Dynamic pressure can be measured by taking the differential pressure between instruments parallel and perpendicular to the flow. Pitot-static tubes, for example perform this measurement on airplanes to determine airspeed. The presence of the measuring instrument inevitably acts to divert flow and create turbulence, so its shape is critical to accuracy and the calibration curves are often non-linear.

Example: A water tank has a pressure of 10 atm. The atmospheric pressure is 1 atm. What is the gauge pressure?

P_g = P_a - P_v

= 10 atm - 1 atm

= 9 atm

Therefore, the gauge pressure is 9 atm.

Instruments

[edit]

A pressure sensor is a device for pressure measurement of gases or liquids. Pressure sensors can alternatively be called pressure transducers, pressure transmitters, pressure senders, pressure indicators, piezometers and manometers, among other names.

Pressure is an expression of the force required to stop a fluid from expanding, and is usually stated in terms of force per unit area. A pressure sensor usually acts as a transducer; it generates a signal as a function of the pressure imposed.

Pressure sensors can vary drastically in technology, design, performance, application suitability and cost. A conservative estimate would be that there may be over 50 technologies and at least 300 companies making pressure sensors worldwide. There is also a category of pressure sensors that are designed to measure in a dynamic mode for capturing very high speed changes in pressure. Example applications for this type of sensor would be in the measuring of combustion pressure in an engine cylinder or in a gas turbine. These sensors are commonly manufactured out of piezoelectric materials such as quartz.

Some pressure sensors are pressure switches, which turn on or off at a particular pressure. For example, a water pump can be controlled by a pressure switch so that it starts when water is released from the system, reducing the pressure in a reservoir.

Pressure range, sensitivity, dynamic response and cost all vary by several orders of magnitude from one instrument design to the next. The oldest type is the liquid column (a vertical tube filled with mercury) manometer invented by Evangelista Torricelli in 1643. The U-Tube was invented by Christiaan Huygens in 1661.

There are two basic categories of analog pressure sensors: force collector and other types.

- Force collector types

- These types of electronic pressure sensors generally use a force collector (such a diaphragm, piston, Bourdon tube, or bellows) to measure strain (or deflection) due to applied force over an area (pressure).

- Piezoresistive strain gauge: Uses the piezoresistive effect of bonded or formed strain gauges to detect strain due to an applied pressure, electrical resistance increasing as pressure deforms the material. Common technology types are silicon (monocrystalline), polysilicon thin film, bonded metal foil, thick film, silicon-on-sapphire and sputtered thin film. Generally, the strain gauges are connected to form a Wheatstone bridge circuit to maximize the output of the sensor and to reduce sensitivity to errors. This is the most commonly employed sensing technology for general purpose pressure measurement.

- Capacitive: Uses a diaphragm and pressure cavity to create a variable capacitor to detect strain due to applied pressure, capacitance decreasing as pressure deforms the diaphragm. Common technologies use metal, ceramic, and silicon diaphragms. Capacitive pressure sensors are being integrated into CMOS technology[9] and it is being explored if thin 2D materials can be used as diaphragm material.[10]

- Electromagnetic: Measures the displacement of a diaphragm by means of changes in inductance (reluctance), linear variable differential transformer (LVDT), Hall effect, or by eddy current principle.

- Piezoelectric: Uses the piezoelectric effect in certain materials such as quartz to measure the strain upon the sensing mechanism due to pressure. This technology is commonly employed for the measurement of highly dynamic pressures. As the basic principle is dynamic, no static pressures can be measured with piezoelectric sensors.

- Strain-Gauge: Strain gauge based pressure sensors also use a pressure sensitive element where metal strain gauges are glued on or thin-film gauges are applied on by sputtering. This measuring element can either be a diaphragm or for metal foil gauges measuring bodies in can-type can also be used. The big advantages of this monolithic can-type design are an improved rigidity and the capability to measure highest pressures of up to 15,000 bar. The electrical connection is normally done via a Wheatstone bridge, which allows for a good amplification of the signal and precise and constant measuring results.[11]

- Optical: Techniques include the use of the physical change of an optical fiber to detect strain due to applied pressure. A common example of this type utilizes Fiber Bragg Gratings. This technology is employed in challenging applications where the measurement may be highly remote, under high temperature, or may benefit from technologies inherently immune to electromagnetic interference. Another analogous technique utilizes an elastic film constructed in layers that can change reflected wavelengths according to the applied pressure (strain).[12]

- Potentiometric: Uses the motion of a wiper along a resistive mechanism to detect the strain caused by applied pressure.

- Force balancing: Force-balanced fused quartz Bourdon tubes use a spiral Bourdon tube to exert force on a pivoting armature containing a mirror, the reflection of a beam of light from the mirror senses the angular displacement and current is applied to electromagnets on the armature to balance the force from the tube and bring the angular displacement to zero, the current that is applied to the coils is used as the measurement. Due to the extremely stable and repeatable mechanical and thermal properties of fused quartz and the force balancing which eliminates most non-linear effects these sensors can be accurate to around 1PPM of full scale.[13] Due to the extremely fine fused quartz structures which are made by hand and require expert skill to construct these sensors are generally limited to scientific and calibration purposes. Non force-balancing sensors have lower accuracy and reading the angular displacement cannot be done with the same precision as a force-balancing measurement, although easier to construct due to the larger size these are no longer used.

- Other types

- These types of electronic pressure sensors use other properties (such as density) to infer pressure of a gas, or liquid.

- Resonant: Uses the changes in resonant frequency in a sensing mechanism to measure stress, or changes in gas density, caused by applied pressure. This technology may be used in conjunction with a force collector, such as those in the category above. Alternatively, resonant technology may be employed by exposing the resonating element itself to the media, whereby the resonant frequency is dependent upon the density of the media. Sensors have been made out of vibrating wire, vibrating cylinders, quartz, and silicon MEMS. Generally, this technology is considered to provide very stable readings over time. The squeeze-film pressure sensor is a type of MEMS resonant pressure sensor that operates by a thin membrane that compresses a thin film of gas at high frequency. Since the compressibility and stiffness of the gas film are pressure dependent, the resonance frequency of the squeeze-film pressure sensor is used as a measure of the gas pressure.[14][15]

- Thermal: Uses the changes in thermal conductivity of a gas due to density changes to measure pressure. A common example of this type is the Pirani gauge.

- Ionization: Measures the flow of charged gas particles (ions) which varies due to density changes to measure pressure. Common examples are the Hot and Cold Cathode gauges.

A pressure sensor, a resonant quartz crystal strain gauge with a Bourdon tube force collector, is the critical sensor of DART.[16] DART detects tsunami waves from the bottom of the open ocean. It has a pressure resolution of approximately 1mm of water when measuring pressure at a depth of several kilometers.[17]

Hydrostatic

[edit]Hydrostatic gauges (such as the mercury column manometer) compare pressure to the hydrostatic force per unit area at the base of a column of fluid. Hydrostatic gauge measurements are independent of the type of gas being measured, and can be designed to have a very linear calibration. They have poor dynamic response.

Piston

[edit]Piston-type gauges counterbalance the pressure of a fluid with a spring (for example tire-pressure gauges of comparatively low accuracy) or a solid weight, in which case it is known as a deadweight tester and may be used for calibration of other gauges.

Liquid column (manometer)

[edit]

Liquid-column gauges consist of a column of liquid in a tube whose ends are exposed to different pressures. The column will rise or fall until its weight (a force applied due to gravity) is in equilibrium with the pressure differential between the two ends of the tube (a force applied due to fluid pressure). A very simple version is a U-shaped tube half-full of liquid, one side of which is connected to the region of interest while the reference pressure (which might be the atmospheric pressure or a vacuum) is applied to the other. The difference in liquid levels represents the applied pressure. The pressure exerted by a column of fluid of height h and density ρ is given by the hydrostatic pressure equation, P = hgρ. Therefore, the pressure difference between the applied pressure Pa and the reference pressure P0 in a U-tube manometer can be found by solving Pa − P0 = hgρ. In other words, the pressure on either end of the liquid (shown in blue in the figure) must be balanced (since the liquid is static), and so Pa = P0 + hgρ.

In most liquid-column measurements, the result of the measurement is the height h, expressed typically in mm, cm, or inches. The h is also known as the pressure head. When expressed as a pressure head, pressure is specified in units of length and the measurement fluid must be specified. When accuracy is critical, the temperature of the measurement fluid must likewise be specified, because liquid density is a function of temperature. So, for example, pressure head might be written "742.2 mmHg" or "4.2 inH2O at 59 °F" for measurements taken with mercury or water as the manometric fluid respectively. The word "gauge" or "vacuum" may be added to such a measurement to distinguish between a pressure above or below the atmospheric pressure. Both mm of mercury and inches of water are common pressure heads, which can be converted to S.I. units of pressure using unit conversion and the above formulas.

If the fluid being measured is significantly dense, hydrostatic corrections may have to be made for the height between the moving surface of the manometer working fluid and the location where the pressure measurement is desired, except when measuring differential pressure of a fluid (for example, across an orifice plate or venturi), in which case the density ρ should be corrected by subtracting the density of the fluid being measured.[18]

Although any fluid can be used, mercury is preferred for its high density (13.534 g/cm3) and low vapour pressure. Its convex meniscus is advantageous since this means there will be no pressure errors from wetting the glass, though under exceptionally clean circumstances, the mercury will stick to glass and the barometer may become stuck (the mercury can sustain a negative absolute pressure) even under a strong vacuum.[19] For low pressure differences, light oil or water are commonly used (the latter giving rise to units of measurement such as inches water gauge and millimetres H2O). Liquid-column pressure gauges have a highly linear calibration. They have poor dynamic response because the fluid in the column may react slowly to a pressure change.

When measuring vacuum, the working liquid may evaporate and contaminate the vacuum if its vapor pressure is too high. When measuring liquid pressure, a loop filled with gas or a light fluid can isolate the liquids to prevent them from mixing, but this can be unnecessary, for example, when mercury is used as the manometer fluid to measure differential pressure of a fluid such as water. Simple hydrostatic gauges can measure pressures ranging from a few torrs (a few 100 Pa) to a few atmospheres (approximately 1000000 Pa).

A single-limb liquid-column manometer has a larger reservoir instead of one side of the U-tube and has a scale beside the narrower column. The column may be inclined to further amplify the liquid movement. Based on the use and structure, following types of manometers are used[20]

- Simple manometer

- Micromanometer

- Differential manometer

- Inverted differential manometer

McLeod gauge

[edit]

A McLeod gauge isolates a sample of gas and compresses it in a modified mercury manometer until the pressure is a few millimetres of mercury. The technique is very slow and unsuited to continual monitoring, but is capable of good accuracy. Unlike other manometer gauges, the McLeod gauge reading is dependent on the composition of the gas, since the interpretation relies on the sample compressing as an ideal gas. Due to the compression process, the McLeod gauge completely ignores partial pressures from non-ideal vapors that condense, such as pump oils, mercury, and even water if compressed enough.

0.1 mPa is the lowest direct measurement of pressure that is possible with current technology. Other vacuum gauges can measure lower pressures, but only indirectly by measurement of other pressure-dependent properties. These indirect measurements must be calibrated to SI units by a direct measurement, most commonly a McLeod gauge.[22]

Aneroid

[edit]Aneroid gauges are based on a metallic pressure-sensing element that flexes elastically under the effect of a pressure difference across the element. "Aneroid" means "without fluid", and the term originally distinguished these gauges from the hydrostatic gauges described above. However, aneroid gauges can be used to measure the pressure of a liquid as well as a gas, and they are not the only type of gauge that can operate without fluid. For this reason, they are often called mechanical gauges in modern language. Aneroid gauges are not dependent on the type of gas being measured, unlike thermal and ionization gauges, and are less likely to contaminate the system than hydrostatic gauges. The pressure sensing element may be a Bourdon tube, a diaphragm, a capsule, or a set of bellows, which will change shape in response to the pressure of the region in question. The deflection of the pressure sensing element may be read by a linkage connected to a needle, or it may be read by a secondary transducer. The most common secondary transducers in modern vacuum gauges measure a change in capacitance due to the mechanical deflection. Gauges that rely on a change in capacitance are often referred to as capacitance manometers.

Bourdon tube

[edit]

The Bourdon pressure gauge uses the principle that a flattened tube[23] tends to straighten or regain its circular form in cross-section when pressurized. (A party horn illustrates this principle.) This change in cross-section may be hardly noticeable, involving moderate stresses within the elastic range of easily workable materials. The strain of the material of the tube is magnified by forming the tube into a C shape or even a helix, such that the entire tube tends to straighten out or uncoil elastically as it is pressurized. Eugène Bourdon patented his gauge in France in 1849, and it was widely adopted because of its superior simplicity, linearity, and accuracy; Bourdon is now part of the Baumer group and still manufacture Bourdon tube gauges in France. Edward Ashcroft purchased Bourdon's American patent rights in 1852 and became a major manufacturer of gauges. Also in 1849, Bernard Schaeffer in Magdeburg, Germany patented a successful diaphragm (see below) pressure gauge, which, together with the Bourdon gauge, revolutionized pressure measurement in industry.[24] But in 1875 after Bourdon's patents expired, his company Schaeffer and Budenberg also manufactured Bourdon tube gauges.

In practice, a flattened thin-wall, closed-end tube is connected at the hollow end to a fixed pipe containing the fluid pressure to be measured. As the pressure increases, the closed end moves in an arc, and this motion is converted into the rotation of a (segment of a) gear by a connecting link that is usually adjustable. A small-diameter pinion gear is on the pointer shaft, so the motion is magnified further by the gear ratio. The positioning of the indicator card behind the pointer, the initial pointer shaft position, the linkage length and initial position, all provide means to calibrate the pointer to indicate the desired range of pressure for variations in the behavior of the Bourdon tube itself. Differential pressure can be measured by gauges containing two different Bourdon tubes, with connecting linkages (but is more usually measured via diaphragms or bellows and a balance system).

Bourdon tubes measures gauge pressure, relative to ambient atmospheric pressure, as opposed to absolute pressure; vacuum is sensed as a reverse motion. Some aneroid barometers use Bourdon tubes closed at both ends (but most use diaphragms or capsules, see below). When the measured pressure is rapidly pulsing, such as when the gauge is near a reciprocating pump, an orifice restriction in the connecting pipe is frequently used to avoid unnecessary wear on the gears and provide an average reading; when the whole gauge is subject to mechanical vibration, the case (including the pointer and dial) can be filled with an oil or glycerin. Typical high-quality modern gauges provide an accuracy of ±1% of span (Nominal diameter 100mm, Class 1 EN837-1), and a special high-accuracy gauge can be as accurate as 0.1% of full scale.[25]

Force-balanced fused quartz Bourdon tube sensors work on the same principle but uses the reflection of a beam of light from a mirror to sense the angular displacement and current is applied to electromagnets to balance the force of the tube and bring the angular displacement back to zero, the current that is applied to the coils is used as the measurement. Due to the extremely stable and repeatable mechanical and thermal properties of quartz and the force balancing which eliminates nearly all physical movement these sensors can be accurate to around 1 PPM of full scale.[26] Due to the extremely fine fused quartz structures which must be made by hand these sensors are generally limited to scientific and calibration purposes.

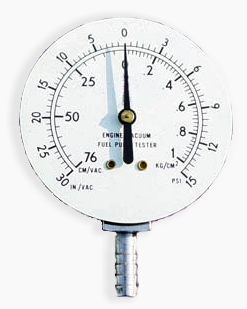

In the following illustrations of a compound gauge (vacuum and gauge pressure), the case and window has been removed to show only the dial, pointer and process connection. This particular gauge is a combination vacuum and pressure gauge used for automotive diagnosis:

- The left side of the face, used for measuring vacuum, is calibrated in inches of mercury on its outer scale and centimetres of mercury on its inner scale

- The right portion of the face is used to measure fuel pump pressure or turbo boost and is scaled in pounds per square inch on its outer scale and kg/cm2 on its inner scale.

Mechanical details include stationary and moving parts.

Stationary parts:

- Receiver block. This joins the inlet pipe to the fixed end of the Bourdon tube (1) and secures the chassis plate (B). The two holes receive screws that secure the case.

- Chassis plate. The dial is attached to this. It contains bearing holes for the axles.

- Secondary chassis plate. It supports the outer ends of the axles.

- Posts to join and space the two chassis plates.

Moving parts:

- Stationary end of Bourdon tube. This communicates with the inlet pipe through the receiver block.

- Moving end of Bourdon tube. This end is sealed.

- Pivot and pivot pin

- Link joining pivot pin to lever (5) with pins to allow joint rotation

- Lever, an extension of the sector gear (7)

- Sector gear axle pin

- Sector gear

- Indicator needle axle. This has a spur gear that engages the sector gear (7) and extends through the face to drive the indicator needle. Due to the short distance between the lever arm link boss and the pivot pin and the difference between the effective radius of the sector gear and that of the spur gear, any motion of the Bourdon tube is greatly amplified. A small motion of the tube results in a large motion of the indicator needle.

- Hair spring to preload the gear train to eliminate gear lash and hysteresis

Diaphragm (membrane)

[edit]A second type of aneroid gauge uses deflection of a flexible membrane that separates regions of different pressure. The amount of deflection is repeatable for known pressures so the pressure can be determined by using calibration. The deformation of a thin diaphragm is dependent on the difference in pressure between its two faces. The reference face can be open to atmosphere to measure gauge pressure, open to a second port to measure differential pressure, or can be sealed against a vacuum or other fixed reference pressure to measure absolute pressure. The deformation can be measured using mechanical, optical or capacitive techniques. Ceramic and metallic diaphragms are used. The useful range is above 10−2 Torr (roughly 1 Pa).[27] For absolute measurements, welded pressure capsules with diaphragms on either side are often used. Membrane shapes include:

- Flat

- Corrugated

- Flattened tube

- Capsule

Bellows

[edit]

In gauges intended to sense small pressures or pressure differences, or require that an absolute pressure be measured, the gear train and needle may be driven by an enclosed and sealed bellows chamber, called an aneroid. (Early barometers used a column of liquid such as water or the liquid metal mercury suspended by a vacuum.) This bellows configuration is used in aneroid barometers (barometers with an indicating needle and dial card), altimeters, altitude recording barographs, and the altitude telemetry instruments used in weather balloon radiosondes. These devices use the sealed chamber as a reference pressure and are driven by the external pressure. Other sensitive aircraft instruments such as air speed indicators and rate of climb indicators (variometers) have connections both to the internal part of the aneroid chamber and to an external enclosing chamber.

Magnetic coupling

[edit]These gauges use the attraction of two magnets to translate differential pressure into motion of a dial pointer. As differential pressure increases, a magnet attached to either a piston or rubber diaphragm moves. A rotary magnet that is attached to a pointer then moves in unison. To create different pressure ranges, the spring rate can be increased or decreased.

Spinning-rotor gauge

[edit]The spinning-rotor gauge works by measuring how a rotating ball is slowed by the viscosity of the gas being measured. The ball is made of steel and is magnetically levitated inside a steel tube closed at one end and exposed to the gas to be measured at the other. The ball is brought up to speed (about 2500 or 3800 rad/s), and the deceleration rate is measured after switching off the drive, by electromagnetic transducers.[28] The range of the instrument is 5−5 to 102 Pa (103 Pa with less accuracy). It is accurate and stable enough to be used as a secondary standard. During the last years this type of gauge became much more user friendly and easier to operate. In the past the instrument was famous for requiring some skill and knowledge to use correctly. For high accuracy measurements various corrections must be applied and the ball must be spun at a pressure well below the intended measurement pressure for five hours before using. It is most useful in calibration and research laboratories where high accuracy is required and qualified technicians are available.[29] Insulation vacuum monitoring of cryogenic liquids is a well suited application for this system too. With the inexpensive and long term stable, weldable sensor, that can be separated from the more costly electronics, it is a perfect fit to all static vacuums.

Electronic pressure instruments

[edit]- Metal strain gauge

- The strain gauge is generally glued (foil strain gauge) or deposited (thin-film strain gauge) onto a membrane. Membrane deflection due to pressure causes a resistance change in the strain gauge which can be electronically measured.

- Piezoresistive strain gauge

- Uses the piezoresistive effect of bonded or formed strain gauges to detect strain due to applied pressure.

- Piezoresistive silicon pressure sensor

- The sensor is generally a temperature compensated, piezoresistive silicon pressure sensor chosen for its excellent performance and long-term stability. Integral temperature compensation is provided over a range of 0–50 °C using laser-trimmed resistors. An additional laser-trimmed resistor is included to normalize pressure sensitivity variations by programming the gain of an external differential amplifier. This provides good sensitivity and long-term stability. The two ports of the sensor, apply pressure to the same single transducer, please see pressure flow diagram below.

This is an over-simplified diagram, but you can see the fundamental design of the internal ports in the sensor. The important item here to note is the "diaphragm" as this is the sensor itself. Is it slightly convex in shape (highly exaggerated in the drawing); this is important as it affects the accuracy of the sensor in use.

The shape of the sensor is important because it is calibrated to work in the direction of air flow as shown by the RED arrows. This is normal operation for the pressure sensor, providing a positive reading on the display of the digital pressure meter. Applying pressure in the reverse direction can induce errors in the results as the movement of the air pressure is trying to force the diaphragm to move in the opposite direction. The errors induced by this are small, but can be significant, and therefore it is always preferable to ensure that the more positive pressure is always applied to the positive (+ve) port and the lower pressure is applied to the negative (-ve) port, for normal 'gauge pressure' application. The same applies to measuring the difference between two vacuums, the larger vacuum should always be applied to the negative (-ve) port. The measurement of pressure via the Wheatstone Bridge looks something like this....

The effective electrical model of the transducer, together with a basic signal conditioning circuit, is shown in the application schematic. The pressure sensor is a fully active Wheatstone bridge which has been temperature compensated and offset adjusted by means of thick film, laser trimmed resistors. The excitation to the bridge is applied via a constant current. The low-level bridge output is at +O and -O, and the amplified span is set by the gain programming resistor (r). The electrical design is microprocessor controlled, which allows for calibration, the additional functions for the user, such as Scale Selection, Data Hold, Zero and Filter functions, the Record function that stores/displays MAX/MIN.

- Capacitive

- Uses a diaphragm and pressure cavity to create a variable capacitor to detect strain due to applied pressure.

- Magnetic

- Measures the displacement of a diaphragm by means of changes in inductance (reluctance), LVDT, Hall effect, or by eddy current principle.

- Piezoelectric

- Uses the piezoelectric effect in certain materials such as quartz to measure the strain upon the sensing mechanism due to pressure.

- Optical

- Uses the physical change of an optical fiber to detect strain due to applied pressure.

- Potentiometric

- Uses the motion of a wiper along a resistive mechanism to detect the strain caused by applied pressure.

- Resonant

- Uses the changes in resonant frequency in a sensing mechanism to measure stress, or changes in gas density, caused by applied pressure.

Thermal conductivity

[edit]Generally, as a real gas increases in density -which may indicate an increase in pressure- its ability to conduct heat increases. In this type of gauge, a wire filament is heated by running current through it. A thermocouple or resistance thermometer (RTD) can then be used to measure the temperature of the filament. This temperature is dependent on the rate at which the filament loses heat to the surrounding gas, and therefore on the thermal conductivity. A common variant is the Pirani gauge, which uses a single platinum filament as both the heated element and RTD. These gauges are accurate from 10−3 Torr to 10 Torr, but their calibration is sensitive to the chemical composition of the gases being measured.

Pirani (one wire)

[edit]

A Pirani gauge consists of a metal wire open to the pressure being measured. The wire is heated by a current flowing through it and cooled by the gas surrounding it. If the gas pressure is reduced, the cooling effect will decrease, hence the equilibrium temperature of the wire will increase. The resistance of the wire is a function of its temperature: by measuring the voltage across the wire and the current flowing through it, the resistance (and so the gas pressure) can be determined. This type of gauge was invented by Marcello Pirani.

Two-wire

[edit]In two-wire gauges, one wire coil is used as a heater, and the other is used to measure temperature due to convection. Thermocouple gauges and thermistor gauges work in this manner using a thermocouple or thermistor, respectively, to measure the temperature of the heated wire.

Ionization gauge

[edit]Ionization gauges are the most sensitive gauges for very low pressures (also referred to as hard or high vacuum). They sense pressure indirectly by measuring the electrical ions produced when the gas is bombarded with electrons. Fewer ions will be produced by lower density gases. The calibration of an ion gauge is unstable and dependent on the nature of the gases being measured, which is not always known. They can be calibrated against a McLeod gauge which is much more stable and independent of gas chemistry.

Thermionic emission generates electrons, which collide with gas atoms and generate positive ions. The ions are attracted to a suitably biased electrode known as the collector. The current in the collector is proportional to the rate of ionization, which is a function of the pressure in the system. Hence, measuring the collector current gives the gas pressure. There are several sub-types of ionization gauge.

Most ion gauges come in two types: hot cathode and cold cathode. In the hot cathode version, an electrically heated filament produces an electron beam. The electrons travel through the gauge and ionize gas molecules around them. The resulting ions are collected at a negative electrode. The current depends on the number of ions, which depends on the pressure in the gauge. Hot cathode gauges are accurate from 10−3 Torr to 10−10 Torr. The principle behind cold cathode version is the same, except that electrons are produced in the discharge of a high voltage. Cold cathode gauges are accurate from 10−2 Torr to 10−9 Torr. Ionization gauge calibration is very sensitive to construction geometry, chemical composition of gases being measured, corrosion and surface deposits. Their calibration can be invalidated by activation at atmospheric pressure or low vacuum. The composition of gases at high vacuums will usually be unpredictable, so a mass spectrometer must be used in conjunction with the ionization gauge for accurate measurement.[30]

Hot cathode

[edit]

A hot-cathode ionization gauge is composed mainly of three electrodes acting together as a triode, wherein the cathode is the filament. The three electrodes are a collector or plate, a filament, and a grid. The collector current is measured in picoamperes by an electrometer. The filament voltage to ground is usually at a potential of 30 volts, while the grid voltage at 180–210 volts DC, unless there is an optional electron bombardment feature, by heating the grid, which may have a high potential of approximately 565 volts.

The most common ion gauge is the hot-cathode Bayard–Alpert gauge, with a small ion collector inside the grid. A glass envelope with an opening to the vacuum can surround the electrodes, but usually the nude gauge is inserted in the vacuum chamber directly, the pins being fed through a ceramic plate in the wall of the chamber. Hot-cathode gauges can be damaged or lose their calibration if they are exposed to atmospheric pressure or even low vacuum while hot. The measurements of a hot-cathode ionization gauge are always logarithmic.

Electrons emitted from the filament move several times in back-and-forth movements around the grid before finally entering the grid. During these movements, some electrons collide with a gaseous molecule to form a pair of an ion and an electron (electron ionization). The number of these ions is proportional to the gaseous molecule density multiplied by the electron current emitted from the filament, and these ions pour into the collector to form an ion current. Since the gaseous molecule density is proportional to the pressure, the pressure is estimated by measuring the ion current.

The low-pressure sensitivity of hot-cathode gauges is limited by the photoelectric effect. Electrons hitting the grid produce x-rays that produce photoelectric noise in the ion collector. This limits the range of older hot-cathode gauges to 10−8 Torr and the Bayard–Alpert to about 10−10 Torr. Additional wires at cathode potential in the line of sight between the ion collector and the grid prevent this effect. In the extraction type the ions are not attracted by a wire, but by an open cone. As the ions cannot decide which part of the cone to hit, they pass through the hole and form an ion beam. This ion beam can be passed on to a:

- Faraday cup

- Microchannel plate detector with Faraday cup

- Quadrupole mass analyzer with Faraday cup

- Quadrupole mass analyzer with microchannel plate detector and Faraday cup

- Ion lens and acceleration voltage and directed at a target to form a sputter gun. In this case a valve lets gas into the grid-cage.

Cold cathode

[edit]

There are two subtypes of cold-cathode ionization gauges: the Penning gauge (invented by Frans Michel Penning), and the inverted magnetron, also called a Redhead gauge. The major difference between the two is the position of the anode with respect to the cathode. Neither has a filament, and each may require a DC potential of about 4 kV for operation. Inverted magnetrons can measure down to 1×10−12 Torr.

Likewise, cold-cathode gauges may be reluctant to start at very low pressures, in that the near-absence of a gas makes it difficult to establish an electrode current - in particular in Penning gauges, which use an axially symmetric magnetic field to create path lengths for electrons that are of the order of metres. In ambient air, suitable ion-pairs are ubiquitously formed by cosmic radiation; in a Penning gauge, design features are used to ease the set-up of a discharge path. For example, the electrode of a Penning gauge is usually finely tapered to facilitate the field emission of electrons.

Maintenance cycles of cold cathode gauges are, in general, measured in years, depending on the gas type and pressure that they are operated in. Using a cold cathode gauge in gases with substantial organic components, such as pump oil fractions, can result in the growth of delicate carbon films and shards within the gauge that eventually either short-circuit the electrodes of the gauge or impede the generation of a discharge path.

| Physical phenomena | Instrument | Governing equation | Limiting factors | Practical pressure range | Ideal accuracy | Response time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical | Liquid column manometer | atm. to 1 mbar | ||||

| Mechanical | Capsule dial gauge | Friction | 1000 to 1 mbar | ±5% of full scale | Slow | |

| Mechanical | Strain gauge | 1000 to 1 mbar | Fast | |||

| Mechanical | Capacitance manometer | Temperature fluctuations | atm to 10−6 mbar | ±1% of reading | Slower when filter mounted | |

| Mechanical | McLeod | Boyle's law | 10 to 10−6 mbar [32] | ±10% of reading between 10−4 and 5⋅10−2 mbar | ||

| Transport | Spinning rotor (drag) | 10−1 to 10−7 mbar | ±2.5% of reading between 10−7 and 10−2 mbar

2.5 to 13.5% between 10−2 and 1 mbar |

|||

| Transport | Pirani (Wheatstone bridge) | Thermal conductivity | 1000 to 10−3 mbar (const. temperature)

10 to 10−3 mbar (const. voltage) |

±6% of reading between 10−2 and 10 mbar | Fast | |

| Transport | Thermocouple (Seebeck effect) | Thermal conductivity | 5 to 10−3 mbar | ±10% of reading between 10−2 and 1 mbar | ||

| Ionization | Cold cathode (Penning) | Ionization yield | 10−2 to 10−7 mbar | +100 to -50% of reading | ||

| Ionization | Hot cathode (ionization induced by thermionic emission) | Low current measurement; parasitic x-ray emission | 10−3 to 10−10 mbar | ±10% between 10−7 and 10−4 mbar

±20% at 10−3 and 10−9 mbar ±100% at 10−10 mbar |

Dynamic transients

[edit]When fluid flows are not in equilibrium, local pressures may be higher or lower than the average pressure in a medium. These disturbances propagate from their source as longitudinal pressure variations along the path of propagation. This is also called sound. Sound pressure is the instantaneous local pressure deviation from the average pressure caused by a sound wave. Sound pressure can be measured using a microphone in air and a hydrophone in water. The effective sound pressure is the root mean square of the instantaneous sound pressure over a given interval of time. Sound pressures are normally small and are often expressed in units of microbar.

- frequency response of pressure sensors

- resonance

Calibration and standards

[edit]

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) has developed two separate and distinct standards on pressure measurement, B40.100 and PTC 19.2. B40.100 provides guidelines on Pressure Indicated Dial Type and Pressure Digital Indicating Gauges, Diaphragm Seals, Snubbers, and Pressure Limiter Valves. PTC 19.2 provides instructions and guidance for the accurate determination of pressure values in support of the ASME Performance Test Codes. The choice of method, instruments, required calculations, and corrections to be applied depends on the purpose of the measurement, the allowable uncertainty, and the characteristics of the equipment being tested.

The methods for pressure measurement and the protocols used for data transmission are also provided. Guidance is given for setting up the instrumentation and determining the uncertainty of the measurement. Information regarding the instrument type, design, applicable pressure range, accuracy, output, and relative cost is provided. Information is also provided on pressure-measuring devices that are used in field environments i.e., piston gauges, manometers, and low-absolute-pressure (vacuum) instruments.

These methods are designed to assist in the evaluation of measurement uncertainty based on current technology and engineering knowledge, taking into account published instrumentation specifications and measurement and application techniques. This Supplement provides guidance in the use of methods to establish the pressure-measurement uncertainty.

European (CEN) Standard

[edit]- EN 472 : Pressure gauge - Vocabulary.

- EN 837-1 : Pressure gauges. Bourdon tube pressure gauges. Dimensions, metrology, requirements and testing.

- EN 837-2 : Pressure gauges. Selection and installation recommendations for pressure gauges.

- EN 837-3 : Pressure gauges. Diaphragm and capsule pressure gauges. Dimensions, metrology, requirements, and testing.

- B40.100-2013: Pressure gauges and Gauge attachments.

- PTC 19.2-2010 : The Performance test code for pressure measurement.

Applications

[edit]

There are many applications for pressure sensors:

- Pressure sensing

This is where the measurement of interest is pressure, expressed as a force per unit area. This is useful in weather instrumentation, aircraft, automobiles, and any other machinery that has pressure functionality implemented.

- Altitude sensing

This is useful in aircraft, rockets, satellites, weather balloons, and many other applications. All these applications make use of the relationship between changes in pressure relative to the altitude. This relationship is governed by the following equation:[33] This equation is calibrated for an altimeter, up to 36,090 feet (11,000 m). Outside that range, an error will be introduced which can be calculated differently for each different pressure sensor. These error calculations will factor in the error introduced by the change in temperature as we go up.

Barometric pressure sensors can have an altitude resolution of less than 1 meter, which is significantly better than GPS systems (about 20 meters altitude resolution). In navigation applications altimeters are used to distinguish between stacked road levels for car navigation and floor levels in buildings for pedestrian navigation.

- Flow sensing

This is the use of pressure sensors in conjunction with the venturi effect to measure flow. Differential pressure is measured between two segments of a venturi tube that have a different aperture. The pressure difference between the two segments is directly proportional to the flow rate through the venturi tube. A low pressure sensor is almost always required as the pressure difference is relatively small.

- Level / depth sensing

A pressure sensor may also be used to calculate the level of a fluid. This technique is commonly employed to measure the depth of a submerged body (such as a diver or submarine), or level of contents in a tank (such as in a water tower). For most practical purposes, fluid level is directly proportional to pressure. In the case of fresh water where the contents are under atmospheric pressure, 1psi = 27.7 inH2O / 1Pa = 9.81 mmH2O. The basic equation for such a measurement is where P = pressure, ρ = density of the fluid, g = standard gravity, h = height of fluid column above pressure sensor

- Leak testing

A pressure sensor may be used to sense the decay of pressure due to a system leak. This is commonly done by either comparison to a known leak using differential pressure, or by means of utilizing the pressure sensor to measure pressure change over time.

- Groundwater measurement

A piezometer is either a device used to measure liquid pressure in a system by measuring the height to which a column of the liquid rises against gravity, or a device which measures the pressure (more precisely, the piezometric head) of groundwater[34] at a specific point. A piezometer is designed to measure static pressures, and thus differs from a pitot tube by not being pointed into the fluid flow. Observation wells give some information on the water level in a formation, but must be read manually. Electrical pressure transducers of several types can be read automatically, making data acquisition more convenient.

The first piezometers in geotechnical engineering were open wells or standpipes (sometimes called Casagrande piezometers)[35] installed into an aquifer. A Casagrande piezometer will typically have a solid casing down to the depth of interest, and a slotted or screened casing within the zone where water pressure is being measured. The casing is sealed into the drillhole with clay, bentonite or concrete to prevent surface water from contaminating the groundwater supply. In an unconfined aquifer, the water level in the piezometer would not be exactly coincident with the water table, especially when the vertical component of flow velocity is significant. In a confined aquifer under artesian conditions, the water level in the piezometer indicates the pressure in the aquifer, but not necessarily the water table.[36] Piezometer wells can be much smaller in diameter than production wells, and a 5 cm diameter standpipe is common.

Piezometers in durable casings can be buried or pushed into the ground to measure the groundwater pressure at the point of installation. The pressure gauges (transducer) can be vibrating-wire, pneumatic, or strain-gauge in operation, converting pressure into an electrical signal. These piezometers are cabled to the surface where they can be read by data loggers or portable readout units, allowing faster or more frequent reading than is possible with open standpipe piezometers.

See also

[edit]- Air core gauge

- Barometer – Scientific instrument used to measure atmospheric pressure

- Deadweight tester – Device for checking the accuracy of a pressure gauge

- Dynamic pressure – Kinetic energy per unit volume of a fluid

- Force gauge – Instrument for measuring force

- Gauge – Device used to make and display dimensional measurements

- List of sensors

- Isoteniscope – Device for measuring vapor pressure

- Pressure – Force distributed over an area

- Piezometer

- Sphygmomanometer – Instrument for measuring blood pressure

- Vacuum engineering

Applications

[edit]- Altimeter – Instrument used to determine the height of an object above a certain point

- Atmospheric pressure – Static pressure exerted by the weight of the Earth's atmosphere

- Barometer – Scientific instrument used to measure atmospheric pressure

- Brake fluid pressure sensor – Part on cars and trucks

- Caisson gauge – High precision pressure gauge for pressure vessels for human occupancy

- Depth gauge – Instrument that indicates depth below a reference surface

- List of MOSFET applications

- MAP sensor – Sensor in an internal combustion engine's electronic control system

- MOSFET – Type of field-effect transistor

- Pitot tube – Device which measures fluid flow velocity, typically around an aircraft or boat

- Sphygmomanometer – Instrument for measuring blood pressure

- Tensiometer (soil science) – Device used to measure matric water potential

- Time pressure gauge

- Tire-pressure gauge – Type of pressure gauge

References

[edit]- ^ Taskos, Nikolaos (2020-09-16). "Pressure Sensing 101 – Absolute, Gauge, Differential & Sealed pressure". ES Systems. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ Bequette, B. Wayne (2003). Process control: modeling, design, and simulation. Prentice Hall. p. 735. ISBN 978-0-13-353640-9.

- ^ NIST

- ^ a b Staff (2016). "2 - Diving physics". Guidance for Diving Supervisors (IMCA D 022 August 2016, Rev. 1 ed.). London, UK: International Marine Contractors' Association. p. 3.

- ^ Page 2-12.

- ^ "Understanding Vacuum Measurement Units". 9 February 2013.

- ^ Nagata, Tomio; Terabe, Hiroaki; Kuwahara, Sirou; Sakurai, Shizuki; Tabata, Osamu; Sugiyama, Susumu; Esashi, Masayoshi (1992-08-01). "Digital compensated capacitive pressure sensor using CMOS technology for low-pressure measurements". Sensors and Actuators A: Physical. 34 (2): 173–177. doi:10.1016/0924-4247(92)80189-A. ISSN 0924-4247.

- ^ Lemme, Max C.; Wagner, Stefan; Lee, Kangho; Fan, Xuge; Verbiest, Gerard J.; Wittmann, Sebastian; Lukas, Sebastian; Dolleman, Robin J.; Niklaus, Frank; van der Zant, Herre S. J.; Duesberg, Georg S.; Steeneken, Peter G. (2020-07-20). "Nanoelectromechanical Sensors Based on Suspended 2D Materials". Research. 2020: 1–25. Bibcode:2020Resea202048602L. doi:10.34133/2020/8748602. PMC 7388062. PMID 32766550.

- ^ "What is a Pressure Sensor?". HBM. Retrieved 2018-05-09.

- ^ Elastic hologram' pages 113-117, Proc. of the IGC 2010, ISBN 978-0-9566139-1-2 here: http://www.dspace.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/225960

- ^ "Characterization of quartz Bourdon-type high-pressure transducers". Metrologia. November 2005. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/42/6/S20.

- ^ Andrews, M. K.; Turner, G. C.; Harris, P. D.; Harris, I. M. (1993-05-01). "A resonant pressure sensor based on a squeezed film of gas". Sensors and Actuators A: Physical. 36 (3): 219–226. doi:10.1016/0924-4247(93)80196-N. ISSN 0924-4247.

- ^ Dolleman, Robin J.; Davidovikj, Dejan; Cartamil-Bueno, Santiago J.; van der Zant, Herre S. J.; Steeneken, Peter G. (2016-01-13). "Graphene Squeeze-Film Pressure Sensors". Nano Letters. 16 (1): 568–571. arXiv:1510.06919. Bibcode:2016NanoL..16..568D. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b04251. ISSN 1530-6984. PMID 26695136. S2CID 23331693.

- ^ Milburn, Hugh. "The NOAA DART II Description and Disclosure" (PDF). noaa.gov. NOAA, U.S. Government. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Eble, M. C.; Gonzalez, F. I. "Deep-Ocean Bottom Pressure Measurements in the Northeast Pacific" (PDF). noaa.gov. NOAA, U.S. Government. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Methods for the Measurement of Fluid Flow in Pipes, Part 1. Orifice Plates, Nozzles and Venturi Tubes. British Standards Institute. 1964. p. 36.

- ^ Manual of Barometry (WBAN) (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. 1963. pp. A295 – A299.

- ^ [Was: "fluidengineering.co.nr/Manometer.htm". At 1/2010 that took me to bad link. Types of fluid Manometers]

- ^ "Techniques of High Vacuum". Tel Aviv University. 2006-05-04. Archived from the original on 2006-05-04.

- ^ Beckwith, Thomas G.; Marangoni, Roy D. & Lienhard V, John H. (1993). "Measurement of Low Pressures". Mechanical Measurements (Fifth ed.). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. pp. 591–595. ISBN 0-201-56947-7.

- ^ Hiscox, Gardner, D. (1914). Mechanical movements, powers and devices; a treatise describing mechanical movements and devices used in constructive and operative machinery and the mechanical arts, being practically a mechanical dictionary, commencing with a rudimentary description of the early known mechanical powers and detailing the various motions, appliances and inventions used in the mechanical arts to the present time, including a chapter on straight line movements, by Gardner D. Hiscox, (14 ed.). New York: The Norman W. Henley publishing co. p. 50. LCCN 14011376. OCLC 5069239.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The Engine Indicator Canadian Museum of Making

- ^ Boyes, Walt (2008). Instrumentation Reference Book (Fourth ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 1312.

- ^ "Characterization of quartz Bourdon-type high-pressure transducers". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2019-05-05.

- ^ Product brochure from Schoonover, Inc

- ^ A. Chambers, Basic Vacuum Technology, pp. 100–102, CRC Press, 1998. ISBN 0585254915.

- ^ John F. O'Hanlon, A User's Guide to Vacuum Technology, pp. 92–94, John Wiley & Sons, 2005. ISBN 0471467154.

- ^ Robert M. Besançon, ed. (1990). "Vacuum Techniques". The Encyclopedia of Physics (3rd ed.). Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York. pp. 1278–1284. ISBN 0-442-00522-9.

- ^ Nigel S. Harris (1989). Modern Vacuum Practice. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-707099-1.

- ^ https://zenodo.org/records/1751441

- ^ http://www.wrh.noaa.gov/slc/projects/wxcalc/formulas/pressureAltitude.pdf Archived 2017-07-03 at the Wayback Machine National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- ^ Dunnicliff, John (1993) [1988]. Geotechnical Instrumentation for Monitoring Field Performance. Wiley-Interscience. p. 117. ISBN 0-471-00546-0.

- ^ Casagrande, A (1949). Soil Mechanics in the design and Construction of the Logan Airport. J. Boston Soc. Civil Eng., Vol 36, No. 2. pp. 192–221.

- ^ Manual on Suburface Investigations, 1988, American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials page 182

Sources

[edit]- US Navy (1 December 2016). U.S. Navy Diving Manual Revision 7 SS521-AG-PRO-010 0910-LP-115-1921 (PDF). Washington, DC.: US Naval Sea Systems Command. Archived (PDF) from the original on Dec 28, 2016.

External links

[edit]Pressure measurement

View on GrokipediaBasic Concepts

Pressure Types and References

Pressure measurement relies on establishing a zero reference point to ensure unambiguous quantification, as the choice of reference affects the interpretation of readings in various applications. Absolute pressure is defined as the force per unit area measured relative to a perfect vacuum, providing a universal baseline independent of ambient conditions. This reference is thermodynamically fundamental and essential for scenarios involving vacuums or altitudes where atmospheric pressure varies significantly.[4] Gauge pressure, in contrast, measures the difference between the system's pressure and the local atmospheric pressure, with zero corresponding to ambient conditions. It is commonly used in everyday engineering contexts where relative over- or under-pressure matters more than absolute values. The relationship between these is given by the equation , or equivalently , where is atmospheric pressure. This derivation stems from the ideal gas law context, particularly Boyle's law ( at fixed temperature), which demonstrates that pressure must be absolute for consistent volume predictions in sealed systems, as gauge references would introduce errors under varying ambient pressures.[5][6] Differential pressure quantifies the difference between two distinct pressure points in a system, without specifying a fixed reference like vacuum or atmosphere; it is particularly useful for flow or level monitoring. Sealed gauge pressure is a variant of gauge pressure where the reference side is hermetically sealed at a fixed atmospheric level (typically 1 atm), avoiding vent paths and stabilizing readings in high-pressure or contaminated environments.[7][8] The zero reference point is critical: absolute pressure's vacuum baseline eliminates ambiguity in low-pressure regimes, such as aerospace or vacuum processing, where gauge pressure could yield negative values. For instance, automobile tire pressure is typically reported as gauge pressure, indicating inflation above ambient air (e.g., 32 psi gauge), while barometric altimetry in aviation relies on absolute pressure to determine elevation, as it directly correlates with atmospheric density variations.[5][9]Units of Pressure

The pascal (Pa) is the coherent derived unit of pressure in the International System of Units (SI), defined as exactly one newton per square metre (1 Pa = 1 N/m²). This unit provides a fundamental, force-based measure suitable for scientific and engineering applications across scales. Other widely used units, such as the bar, standard atmosphere (atm), torr, and pound-force per square inch (psi), are non-SI but accepted for specific contexts, often requiring conversion to pascals for standardization.[10] Historical units like the millimetre of mercury (mmHg) and inch of mercury (inHg) originated from early barometric measurements based on hydrostatic pressure. In 1643, Evangelista Torricelli invented the mercury barometer, demonstrating that atmospheric pressure could support a column of mercury approximately 760 mm high at sea level, leading to the mmHg as a unit representing the pressure exerted by a 1 mm column of mercury at 0°C under standard gravity.[11] The inHg similarly denotes the hydrostatic pressure of a 1-inch mercury column, primarily used in imperial systems for altimetry and weather reporting.[4] Standardization efforts culminated in the 20th century with the SI system's adoption in 1960 and the pascal's formal naming in 1971, promoting global consistency while retaining legacy units for specialized fields. Conversion factors between units are precisely defined to ensure interoperability. For instance, 1 atm = 101 325 Pa (exact), 1 bar = 100 000 Pa (exact), 1 psi = 6 894.757 Pa, 1 torr = 133.322 Pa, 1 mmHg = 133.322 Pa, and 1 inHg = 3 386.389 Pa.[10] These relations stem from historical definitions tied to atmospheric pressure and hydrostatic principles, with the torr and mmHg being nearly identical in value but distinguished by exactness in vacuum applications.[4] The choice of unit depends on the pressure scale and application domain. The pascal excels in high-precision scientific computations due to its alignment with base SI units, while the bar suits industrial processes involving moderate pressures around atmospheric levels. In vacuum technology, the torr provides fine resolution for low pressures (e.g., from 760 torr at atmosphere down to 10^{-9} torr in ultra-high vacuums), facilitating specifications for equipment like pumps and chambers. Medical contexts favor mmHg for blood pressure readings, reflecting its historical roots in manometry, whereas psi dominates in American engineering for hydraulic and pneumatic systems.[12] Atmospheric and aviation uses often employ inHg for its compatibility with altimeter standards.[4]| Unit | Symbol | Value in Pa | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pascal | Pa | 1 | Scientific research, general SI measurements |

| Bar | bar | 100 000 | Industrial engineering, meteorology (hectopascal variant) |

| Standard atmosphere | atm | 101 325 | Atmospheric science, calibration standards |

| Torr | Torr | 133.322 | Vacuum technology, high-vacuum equipment |

| Millimetre of mercury | mmHg | 133.322 | Medicine (blood pressure), manometry |

| Pound-force per square inch | psi | 6 894.757 | US engineering, hydraulics, tires |

| Inch of mercury | inHg | 3 386.389 | Aviation altimetry, weather barometers |