Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Buckminsterfullerene

View on Wikipedia

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌbʌkmɪnstərˈfʊləriːn/ | ||

| Preferred IUPAC name

(C60-Ih)[5,6]fullerene[1] | |||

| Other names

Buckyballs; Fullerene-C60; [60]fullerene

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| 5901022 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.156.884 | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C60 | |||

| Molar mass | 720.660 g·mol−1 | ||

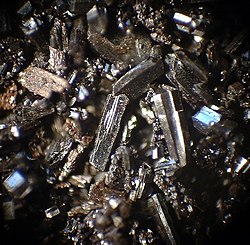

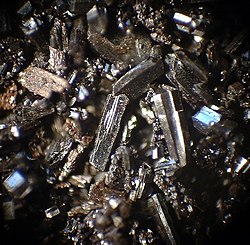

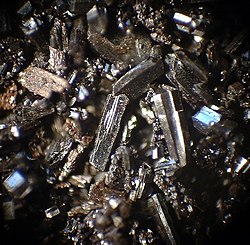

| Appearance | Dark needle-like crystals | ||

| Density | 1.65 g/cm3 | ||

| insoluble in water | |||

| Vapor pressure | 0.4–0.5 Pa (T ≈ 800 K); 14 Pa (T ≈ 900 K) [2] | ||

| Structure | |||

| Face-centered cubic, cF1924 | |||

| Fm3m, No. 225 | |||

a = 1.4154 nm

| |||

| Hazards | |||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| Warning | |||

| H315, H319, H335 | |||

| P261, P264, P271, P280, P302+P352, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P312, P321, P332+P313, P337+P313, P362, P403+P233, P405, P501 | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Nanomaterials |

|---|

|

| Carbon nanotubes |

| Fullerenes |

| Other nanoparticles |

| Nanostructured materials |

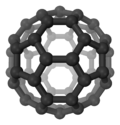

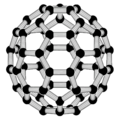

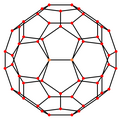

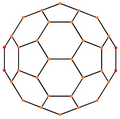

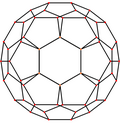

Buckminsterfullerene is a type of fullerene with the formula C

60. It has a cage-like fused-ring structure (truncated icosahedron) made of twenty hexagons and twelve pentagons, and resembles a football. Each of its 60 carbon atoms is bonded to its three neighbors.

Buckminsterfullerene is a black solid that dissolves in hydrocarbon solvents to produce a purple solution. The substance was discovered in 1985 and has received intense study, although few real world applications have been found.

Molecules of buckminsterfullerene (or of fullerenes in general) are commonly nicknamed buckyballs.[3][4]

Occurrence

[edit]Buckminsterfullerene is the most common naturally occurring fullerene. Small quantities of it can be found in soot.[5][6]

It also exists in space. Neutral C

60 has been observed in planetary nebulae[7] and several types of star.[8] The ionised form, C+

60, has been identified in the interstellar medium,[9] where it is the cause of several absorption features known as diffuse interstellar bands in the near-infrared.[10]

History

[edit]

60.

Theoretical predictions of buckminsterfullerene molecules appeared in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[11][12][13][14] It was first generated in 1984 by Eric Rohlfing, Donald Cox, and Andrew Kaldor,[14][15] using a laser to vaporize carbon in a supersonic helium beam, although the group did not realize that buckminsterfullerene had been produced. In 1985 their work was repeated by Harold Kroto, James R. Heath, Sean C. O'Brien, Robert Curl, and Richard Smalley at Rice University, who recognized the structure of C

60 as buckminsterfullerene.[16]

Concurrent but unconnected to the Kroto-Smalley work, astrophysicists were working with spectroscopists to study infrared emissions from giant red carbon stars.[17][18][19] Smalley and team were able to use a laser vaporization technique to create carbon clusters which could potentially emit infrared at the same wavelength as had been emitted by the red carbon star.[17][20] Hence, the inspiration came to Smalley and team to use the laser technique on graphite to generate fullerenes.

Using laser evaporation of graphite the Smalley team found Cn clusters (where n > 20 and even) of which the most common were C

60 and C

70. A solid rotating graphite disk was used as the surface from which carbon was vaporized using a laser beam creating hot plasma that was then passed through a stream of high-density helium gas.[16] The carbon species were subsequently cooled and ionized resulting in the formation of clusters. Clusters ranged in molecular masses, but Kroto and Smalley found predominance in a C

60 cluster that could be enhanced further by allowing the plasma to react longer. They also discovered that C

60 is a cage-like molecule, a regular truncated icosahedron.[17][16]

The experimental evidence, a strong peak at 720 daltons, indicated that a carbon molecule with 60 carbon atoms was forming, but provided no structural information. The research group concluded after reactivity experiments, that the most likely structure was a spheroidal molecule. The idea was quickly rationalized as the basis of an icosahedral symmetry closed cage structure.[11]

Kroto, Curl, and Smalley were awarded the 1996 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their roles in the discovery of buckminsterfullerene and the related class of molecules, the fullerenes.[11]

In 1989 physicists Wolfgang Krätschmer, Konstantinos Fostiropoulos, and Donald R. Huffman observed unusual optical absorptions in thin films of carbon dust (soot). The soot had been generated by an arc-process between two graphite electrodes in a helium atmosphere where the electrode material evaporates and condenses forming soot in the quenching atmosphere. Among other features, the IR spectra of the soot showed four discrete bands in close agreement to those proposed for C

60.[21][22]

Another paper on the characterization and verification of the molecular structure followed on in the same year (1990) from their thin film experiments, and detailed also the extraction of an evaporable as well as benzene-soluble material from the arc-generated soot. This extract had TEM and X-ray crystal analysis consistent with arrays of spherical C

60 molecules, approximately 1.0 nm in van der Waals diameter[23] as well as the expected molecular mass of 720 Da for C

60 (and 840 Da for C

70) in their mass spectra.[24] The method was simple and efficient to prepare the material in gram amounts per day (1990) which has boosted the fullerene research and is even today applied for the commercial production of fullerenes.

The discovery of practical routes to C

60 led to the exploration of a new field of chemistry involving the study of fullerenes.

Etymology

[edit]The discoverers of the allotrope named the newfound molecule after American architect R. Buckminster Fuller, who designed many geodesic dome structures that look similar to C

60 and who had died in 1983, the year before discovery.[11] Another common name for buckminsterfullerene is "buckyballs".[25][4]

Synthesis

[edit]Soot is produced by laser ablation of graphite or pyrolysis of aromatic hydrocarbons. Fullerenes are extracted from the soot with organic solvents using a Soxhlet extractor.[26] This step yields a solution containing up to 75% of C

60, as well as other fullerenes. These fractions are separated using chromatography.[27] Generally, the fullerenes are dissolved in a hydrocarbon or halogenated hydrocarbon and separated using alumina columns.[28]

Synthesis using the techniques of "classical organic chemistry" is possible, but not economic.[29]

Structure

[edit]Buckminsterfullerene is a truncated icosahedron with 60 vertices, 32 faces (20 hexagons and 12 pentagons where no pentagons share a vertex), and 90 edges (60 edges between 5-membered & 6-membered rings and 30 edges are shared between 6-membered & 6-membered rings), with a carbon atom at the vertices of each polygon and a bond along each polygon edge. The van der Waals diameter of a C

60 molecule is about 1.01 nanometers (nm). The nucleus to nucleus diameter of a C

60 molecule is about 0.71 nm. The C

60 molecule has two bond lengths. The 6:6 ring bonds (between two hexagons) can be considered "double bonds" and are shorter than the 6:5 bonds (between a hexagon and a pentagon). Its average bond length is 0.14 nm. Each carbon atom in the structure is bonded covalently with 3 others.[30] A carbon atom in the C

60 can be substituted by a nitrogen or boron atom yielding a C

59N or C

59B respectively.[31]

60 under "ideal" spherical (left) and "real" icosahedral symmetry (right).

Properties

[edit]| Centered by | Vertex | Edge 5–6 |

Edge 6–6 |

Face Hexagon |

Face Pentagon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image |

|

|

|

|

|

| Projective symmetry |

[2] | [2] | [2] | [6] | [10] |

For a time buckminsterfullerene was the largest[quantify] known molecule observed to exhibit wave–particle duality.[32] In 2020 the dye molecule phthalocyanine exhibited the duality that is more famously attributed to light, electrons and other small particles and molecules.[33]

Solution

[edit]

60 in an aromatic solvent

| Solvent | Solubility (g/L) |

|---|---|

| 1-chloronaphthalene | 51 |

| 1-methylnaphthalene | 33 |

| 1,2-dichlorobenzene | 24 |

| 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene | 18 |

| tetrahydronaphthalene | 16 |

| carbon disulfide | 8 |

| 1,2,3-tribromopropane | 8 |

| xylene | 5 |

| bromoform | 5 |

| cumene | 4 |

| toluene | 3 |

| benzene | 1.5 |

| carbon tetrachloride | 0.447 |

| chloroform | 0.25 |

| hexane | 0.046 |

| cyclohexane | 0.035 |

| tetrahydrofuran | 0.006 |

| acetonitrile | 0.004 |

| methanol | 0.00004 |

| water | 1.3 × 10−11 |

| pentane | 0.004 |

| octane | 0.025 |

| isooctane | 0.026 |

| decane | 0.070 |

| dodecane | 0.091 |

| tetradecane | 0.126 |

| dioxane | 0.0041 |

| mesitylene | 0.997 |

| dichloromethane | 0.254 |

60 solution, showing diminished absorption for the blue (~450 nm) and red (~700 nm) light that results in the purple color.

Fullerenes are sparingly soluble in aromatic solvents and carbon disulfide, but insoluble in water. Solutions of pure C

60 have a deep purple color which leaves a brown residue upon evaporation. The reason for this color change is the relatively narrow energy width of the band of molecular levels responsible for green light absorption by individual C

60 molecules. Thus individual molecules transmit some blue and red light resulting in a purple color. Upon drying, intermolecular interaction results in the overlap and broadening of the energy bands, thereby eliminating the blue light transmittance and causing the purple to brown color change.[17]

C

60 crystallises with some solvents in the lattice ("solvates"). For example, crystallization of C

60 from benzene solution yields triclinic crystals with the formula C60·4C6H6. Like other solvates, this one readily releases benzene to give the usual face-centred cubic C

60. Millimeter-sized crystals of C

60 and C

70 can be grown from solution both for solvates and for pure fullerenes.[37][38]

Solid

[edit]

60.

60 in crystal.

In solid buckminsterfullerene, the C

60 molecules adopt the fcc (face-centered cubic) motif. They start rotating at about −20 °C. This change is associated with a first-order phase transition to an fcc structure and a small, yet abrupt increase in the lattice constant from 1.411 to 1.4154 nm.[39]

C

60 solid is as soft as graphite, but when compressed to less than 70% of its volume it transforms into a superhard form of diamond (see aggregated diamond nanorod). C

60 films and solution have strong non-linear optical properties; in particular, their optical absorption increases with light intensity (saturable absorption).

C

60 forms a brownish solid with an optical absorption threshold at ≈1.6 eV.[40] It is an n-type semiconductor with a low activation energy of 0.1–0.3 eV; this conductivity is attributed to intrinsic or oxygen-related defects.[41] Fcc C

60 contains voids at its octahedral and tetrahedral sites which are sufficiently large (0.6 and 0.2 nm respectively) to accommodate impurity atoms. When alkali metals are doped into these voids, C

60 converts from a semiconductor into a conductor or even superconductor.[39][42]

Chemical reactions and properties

[edit]C

60 undergoes six reversible, one-electron reductions, ultimately generating C6−

60. Its oxidation is irreversible. The first reduction occurs at ≈−1.0 V (Fc/Fc+

), showing that C

60 is a reluctant electron acceptor. C

60 tends to avoid having double bonds in the pentagonal rings, which makes electron delocalization poor, and results in C

60 not being "superaromatic". C

60 behaves like an electron deficient alkene. For example, it reacts with some nucleophiles.[23][43]

Hydrogenation

[edit]C

60 exhibits a small degree of aromatic character, but it still reflects localized double and single C–C bond characters. Therefore, C

60 can undergo addition with hydrogen to give polyhydrofullerenes. C

60 also undergoes Birch reduction. For example, C

60 reacts with lithium in liquid ammonia, followed by tert-butanol to give a mixture of polyhydrofullerenes such as C60H18, C60H32, C60H36, with C60H32 being the dominating product. This mixture of polyhydrofullerenes can be re-oxidized by 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone to give C

60 again.

A selective hydrogenation method exists. Reaction of C

60 with 9,9′,10,10′-dihydroanthracene under the same conditions, depending on the time of reaction, gives C60H32 and C60H18 respectively and selectively.[44]

Halogenation

[edit]Addition of fluorine, chlorine, and bromine occurs for C

60. Fluorine atoms are small enough for a 1,2-addition, while Cl

2 and Br

2 add to remote C atoms due to steric factors. For example, in C60Br8 and C60Br24, the Br atoms are in 1,3- or 1,4-positions with respect to each other. Under various conditions a vast number of halogenated derivatives of C

60 can be produced, some with an extraordinary selectivity on one or two isomers over the other possible ones. Addition of fluorine and chlorine usually results in a flattening of the C

60 framework into a drum-shaped molecule.[44]

Addition of oxygen atoms

[edit]Solutions of C

60 can be oxygenated to the epoxide C60O. Ozonation of C

60 in 1,2-xylene at 257K gives an intermediate ozonide C60O3, which can be decomposed into 2 forms of C60O. Decomposition of C60O3 at 296 K gives the epoxide, but photolysis gives a product in which the O atom bridges a 5,6-edge.[44]

Cycloadditions

[edit]The Diels–Alder reaction is commonly employed to functionalize C

60. Reaction of C

60 with appropriate substituted diene gives the corresponding adduct.

The Diels–Alder reaction between C

60 and 3,6-diaryl-1,2,4,5-tetrazines affordsC

62. The C

62 has the structure in which a four-membered ring is surrounded by four six-membered rings.

62 derivative [C62(C6H5-4-Me)2] synthesized from C

60 and 3,6-bis(4-methylphenyl)-3,6-dihydro-1,2,4,5-tetrazine

The C

60 molecules can also be coupled through a [2+2] cycloaddition, giving the dumbbell-shaped compound C

120. The coupling is achieved by high-speed vibrating milling of C

60 with a catalytic amount of KCN. The reaction is reversible as C

120 dissociates back to two C

60 molecules when heated at 450 K (177 °C; 350 °F). Under high pressure and temperature, repeated [2+2] cycloaddition between C

60 results in polymerized fullerene chains and networks. These polymers remain stable at ambient pressure and temperature once formed, and have remarkably interesting electronic and magnetic properties, such as being ferromagnetic above room temperature.[44]

Free radical reactions

[edit]Reactions of C

60 with free radicals readily occur. When C

60 is mixed with a disulfide RSSR, the radical C60SR• forms spontaneously upon irradiation of the mixture.

Stability of the radical species C60Y• depends largely on steric factors of Y. When tert-butyl halide is photolyzed and allowed to react with C

60, a reversible inter-cage C–C bond is formed:[44]

Cyclopropanation (Bingel reaction)

[edit]Cyclopropanation (the Bingel reaction) is another common method for functionalizing C

60. Cyclopropanation of C

60 mostly occurs at the junction of 2 hexagons due to steric factors.

The first cyclopropanation was carried out by treating the β-bromomalonate with C

60 in the presence of a base. Cyclopropanation also occur readily with diazomethanes. For example, diphenyldiazomethane reacts readily with C

60 to give the compound C61Ph2.[44] Phenyl-C

61-butyric acid methyl ester derivative prepared through cyclopropanation has been studied for use in organic solar cells.

Redox reactions

[edit]C

60 anions

[edit]The LUMO in C

60 is triply degenerate, with the HOMO–LUMO separation relatively small. This small gap suggests that reduction of C

60 should occur at mild potentials leading to fulleride anions, [C60]n− (n = 1–6). The midpoint potentials of 1-electron reduction of buckminsterfullerene and its anions is given in the table below:

| Reduction potential of C 60 at 213 K | |

|---|---|

| Half-reaction | E° (V) |

| C60 + e− ⇌ C−60 | −0.169 |

| C−60 + e− ⇌ C2−60 | −0.599 |

| C2−60 + e− ⇌ C3−60 | −1.129 |

| C3−60 + e− ⇌ C4−60 | −1.579 |

| C4−60 + e− ⇌ C5−60 | −2.069 |

| C5−60 + e− ⇌ C6−60 | −2.479 |

C

60 forms a variety of charge-transfer complexes, for example with tetrakis(dimethylamino)ethylene:

- C60 + C2(NMe2)4 → [C2(NMe2)4]+[C60]−

This salt exhibits ferromagnetism at 16 K.

C

60 cations

[edit]C

60 oxidizes with difficulty. Three reversible oxidation processes have been observed by using cyclic voltammetry with ultra-dry methylene chloride and a supporting electrolyte with extremely high oxidation resistance and low nucleophilicity, such as [nBu4N] [AsF6].[43]

| Reduction potentials of C 60 oxidation at low temperatures | |

|---|---|

| Half-reaction | E° (V) |

| C60 ⇌ C+60 | +1.27 |

| C+60 ⇌ C2+60 | +1.71 |

| C2+60 ⇌ C3+60 | +2.14 |

Metal complexes

[edit]C

60 forms complexes akin to the more common alkenes. Complexes have been reported molybdenum, tungsten, platinum, palladium, iridium, and titanium. The pentacarbonyl species are produced by photochemical reactions.

- M(CO)6 + C60 → M(η2-C60)(CO)5 + CO (M = Mo, W)

In the case of platinum complex, the labile ethylene ligand is the leaving group in a thermal reaction:

- Pt(η2-C2H4)(PPh3)2 + C60 → Pt(η2-C60)(PPh3)2 + C2H4

Titanocene complexes have also been reported:

- (η5-Cp)2Ti(η2-(CH3)3SiC≡CSi(CH3)3) + C60 → (η5-Cp)2Ti(η2-C60) + (CH3)3SiC≡CSi(CH3)3

Coordinatively unsaturated precursors, such as Vaska's complex, for adducts with C

60:

- trans-Ir(CO)Cl(PPh3)2 + C60 → Ir(CO)Cl(η2-C60)(PPh3)2

One such iridium complex, [Ir(η2-C60)(CO)Cl(Ph2CH2C6H4OCH2Ph)2] has been prepared where the metal center projects two electron-rich 'arms' that embrace the C

60 guest.[45]

Endohedral fullerenes

[edit]Metal atoms or certain small molecules such as H

2 and noble gas can be encapsulated inside the C

60 cage. These endohedral fullerenes are usually synthesized by doping in the metal atoms in an arc reactor or by laser evaporation. These methods gives low yields of endohedral fullerenes, and a better method involves the opening of the cage, packing in the atoms or molecules, and closing the opening using certain organic reactions. This method, however, is still immature and only a few species have been synthesized this way.[46]

Endohedral fullerenes show distinct and intriguing chemical properties that can be completely different from the encapsulated atom or molecule, as well as the fullerene itself. The encapsulated atoms have been shown to perform circular motions inside the C

60 cage, and their motion has been followed using NMR spectroscopy.[45]

Potential applications in technology

[edit]The optical absorption properties of C

60 match the solar spectrum in a way that suggests that C

60-based films could be useful for photovoltaic applications. Because of its high electronic affinity[47] it is one of the most common electron acceptors used in donor/acceptor based solar cells. Conversion efficiencies up to 5.7% have been reported in C

60–polymer cells.[48]

Potential applications in health

[edit]Ingestion and risks

[edit]C

60 is sensitive to light,[49] so leaving C

60 under light exposure causes it to degrade, becoming dangerous. The ingestion of C

60 solutions that have been exposed to light could lead to developing cancer (tumors).[50][51] So the management of C

60 products for human ingestion requires cautionary measures[51] such as: elaboration in very dark environments, encasing into bottles of great opacity, and storing in dark places, and others like consumption under low light conditions and using labels to warn about the problems with light.

Solutions of C

60 dissolved in olive oil or water, as long as they are preserved from light, have been found nontoxic to rodents.[52]

Otherwise, a study found that C

60 remains in the body for a longer time than usual, especially in the liver, where it tends to be accumulated, and therefore has the potential to induce detrimental health effects.[53]

Oils with C60 and risks

[edit]An experiment in 2011–2012 administered a solution of C

60 in olive oil to rats, achieving a 90% prolongation of their lifespan.[52] C

60 in olive oil administered to mice resulted in no extension in lifespan.[54] C

60 in olive oil administered to beagle dogs resulted in a large reduction of C-reactive protein, which is commonly elevated in cardiovascular disease and cerebrovascular disease.[55]

Many oils with C

60 have been sold as antioxidant products, but it does not avoid the problem of their sensitivity to light, that can turn them toxic. A later research confirmed that exposure to light degrades solutions of C

60 in oil, making it toxic and leading to a "massive" increase of the risk of developing cancer (tumors) after its consumption.[50][51]

To avoid the degradation by effect of light, C

60 oils must be made in very dark environments, encased into bottles of great opacity, and kept in darkness, consumed under low light conditions and accompanied by labels to warn about the dangers of light for C

60.[51][49]

Some producers have been able to dissolve C

60 in water to avoid possible problems with oils, but that would not protect C

60 from light, so the same cautions are needed.[49]

References

[edit]- ^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (2014). Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry: IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013. The Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 325. doi:10.1039/9781849733069. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- ^ Piacente, V.; Gigli, G.; Scardala, P.; Giustini, A.; Ferro, D. (September 1995). "Vapor Pressure of C

60 Buckminsterfullerene". J. Phys. Chem. 99 (38): 14052–14057. doi:10.1021/j100038a041. ISSN 0022-3654. - ^ "Buckyball". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Buckminsterfullerene and Buckyballs – Definition, Discovery, Structure, Production, Properties and Applications". AZoM. 2006-07-15.

- ^ Howard, Jack B.; McKinnon, J. Thomas; Makarovsky, Yakov; Lafleur, Arthur L.; Johnson, M. Elaine (1991). "Fullerenes C

60 and C

70 in flames". Nature. 352 (6331): 139–141. Bibcode:1991Natur.352..139H. doi:10.1038/352139a0. PMID 2067575. S2CID 37159968. - ^ Howard, J; Lafleur, A; Makarovsky, Y; Mitra, S; Pope, C; Yadav, T (1992). "Fullerenes synthesis in combustion". Carbon. 30 (8): 1183–1201. Bibcode:1992Carbo..30.1183H. doi:10.1016/0008-6223(92)90061-Z.

- ^ Cami, J.; Bernard-Salas, J.; Peeters, E.; Malek, S. E. (2010). "Detection of C60 and C70 in a Young Planetary Nebula". Science. 329 (5996): 1180–1182. Bibcode:2010Sci...329.1180C. doi:10.1126/science.1192035. PMID 20651118. S2CID 33588270.

- ^ Roberts, Kyle R. G.; Smith, Keith T.; Sarre, Peter J. (2012). "Detection of C60 in embedded young stellar objects, a Herbig Ae/Be star and an unusual post-asymptotic giant branch star". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 421 (4): 3277–3285. arXiv:1201.3542. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.421.3277R. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.20552.x. S2CID 118739732.

- ^ Berné, O.; Mulas, G.; Joblin, C. (2013). "Interstellar C60+". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 550: L4. arXiv:1211.7252. Bibcode:2013A&A...550L...4B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201220730. S2CID 118684608.

- ^ Maier, J. P.; Gerlich, D.; Holz, M.; Campbell, E. K. (July 2015). "Laboratory confirmation of C+

60 as the carrier of two diffuse interstellar bands". Nature. 523 (7560): 322–323. Bibcode:2015Natur.523..322C. doi:10.1038/nature14566. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 26178962. S2CID 205244293. - ^ a b c d Katz 2006, p. 363

- ^ Osawa, E. (1970). "Superaromaticity". Kagaku (in Japanese). 25. Kyoto: 854–863.

- ^ Jones, David E. H. (1966). "Hollow molecules". New Scientist (32): 245.

- ^ a b Smalley, Richard E. (1997-07-01). "Discovering the fullerenes". Reviews of Modern Physics. 69 (3): 723–730. Bibcode:1997RvMP...69..723S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.31.7103. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.69.723.

- ^ Rohlfing, Eric A; Cox, D. M; Kaldor, A (1984). "Production and characterization of supersonic carbon cluster beams". Journal of Chemical Physics. 81 (7): 3322. Bibcode:1984JChPh..81.3322R. doi:10.1063/1.447994.

- ^ a b c Kroto, H. W.; Health, J. R.; O'Brien, S. C.; Curl, R. F.; Smalley, R. E. (1985). "C

60: Buckminsterfullerene". Nature. 318 (6042): 162–163. Bibcode:1985Natur.318..162K. doi:10.1038/318162a0. S2CID 4314237. - ^ a b c d Dresselhaus, M. S.; Dresselhaus, G.; Eklund, P. C. (1996). Science of Fullerenes and Carbon Nanotubes. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. ISBN 978-012-221820-0.

- ^ Herbig, E. (1975). "The diffuse interstellar bands. IV – the region 4400-6850 A". Astrophys. J. 196: 129. Bibcode:1975ApJ...196..129H. doi:10.1086/153400.

- ^ Leger, A.; d'Hendecourt, L.; Verstraete, L.; Schmidt, W. (1988). "Remarkable candidates for the carrier of the diffuse interstellar bands: C+

60 and other polyhedral carbon ions". Astron. Astrophys. 203 (1): 145. Bibcode:1988A&A...203..145L. - ^ Dietz, T. G.; Duncan, M. A.; Powers, D. E.; Smalley, R. E. (1981). "Laser production of supersonic metal cluster beams". J. Chem. Phys. 74 (11): 6511. Bibcode:1981JChPh..74.6511D. doi:10.1063/1.440991.

- ^ Krätschmer, W.; Fostiropoulos, K.; Huffman, D. R. (1990). "Search for the UV and IR Spectra of C

60 in Laboratory-Produced Carbon Dust". Dusty Objects in the Universe. Vol. 165. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. pp. 89–93. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-0661-7_11. ISBN 978-94-010-6782-9. - ^ Krätschmer, W. (1990). "The infrared and ultraviolet absorption spectra of laboratory-produced carbon dust: evidence for the presence of the C

60 molecule". Chemical Physics Letters. 170 (2–3): 167–170. Bibcode:1990CPL...170..167K. doi:10.1016/0009-2614(90)87109-5. - ^ a b "Buckminsterfullerene: Molecule of the Month". chm.bris.ac.uk. Jan 1997. Archived from the original on 2021-02-27.

- ^ Krätschmer, W.; Lamb, Lowell D.; Fostiropoulos, K.; Huffman, Donald R. (1990). "Solid C

60: A new form of carbon". Nature. 347 (6291): 354–358. Bibcode:1990Natur.347..354K. doi:10.1038/347354a0. S2CID 4359360. - ^ "What is a geodesic dome?". R. Buckminster Fuller Collection: Architect, Systems Theorist, Designer, and Inventor. Stanford University. 6 April 2017. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ Girolami, G. S.; Rauchfuss, T. B.; Angelici, R. J. (1999). Synthesis and Teknique in Inorganic Chemistry. Mill Valley, CA: University Science Books. ISBN 978-0935702484.

- ^ Katz 2006, pp. 369–370

- ^ Shriver; Atkins (2010). Inorganic Chemistry (Fifth ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman. p. 356. ISBN 978-0-19-923617-6.

- ^

- M.M. Boorum, Y.V. Vasil'ev, T. Drewello, and L.T. Scott (2001), in Science 294, pp. 828–.

- L.T. Scott, M.M. Boorum, B.J. McMahon, S. Hagen, J. Mack, J. Blank, H. Wegner, and A. de Meijere (2002), in Science 295, pp. 1500–.

- L.T. Scott (2004), in Angew. Chem. 116, pp. 5102–; translated in Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, pp. 4994–.

- ^ Katz 2006, p. 364

- ^ Katz 2006, p. 374

- ^

Arndt, Markus; Nairz, Olaf; Vos-Andreae, Julian; Keller, Claudia; Van Der Zouw, Gerbrand; Zeilinger, Anton (1999). "Wave–particle duality of C

60". Nature. 401 (6754): 680–682. Bibcode:1999Natur.401..680A. doi:10.1038/44348. PMID 18494170. S2CID 4424892. - ^ Lee, Chris (2020-07-21). "Wave-particle duality in action—big molecules surf on their own waves". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 2021-09-26. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^

Beck, Mihály T.; Mándi, Géza (1997). "Solubility of C

60". Fullerenes, Nanotubes and Carbon Nanostructures. 5 (2): 291–310. doi:10.1080/15363839708011993. - ^ Bezmel'nitsyn, V. N.; Eletskii, A. V.; Okun', M. V. (1998). "Fullerenes in solutions". Physics-Uspekhi. 41 (11): 1091–1114. Bibcode:1998PhyU...41.1091B. doi:10.1070/PU1998v041n11ABEH000502. S2CID 250785669.

- ^

Ruoff, R. S.; Tse, Doris S.; Malhotra, Ripudaman; Lorents, Donald C. (1993). "Solubility of fullerene (C

60) in a variety of solvents". Journal of Physical Chemistry. 97 (13): 3379–3383. doi:10.1021/j100115a049. - ^ Talyzin, A. V. (1997). "Phase Transition C60−C60*4C6H6 in Liquid Benzene". Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 101 (47): 9679–9681. doi:10.1021/jp9720303.

- ^ Talyzin, A. V.; Engström, I. (1998). "C70 in Benzene, Hexane, and Toluene Solutions". Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 102 (34): 6477–6481. doi:10.1021/jp9815255.

- ^ a b Katz 2006, p. 372

- ^ Katz 2006, p. 361

- ^ Katz 2006, p. 379

- ^ Katz 2006, p. 381

- ^ a b Reed, Christopher A.; Bolskar, Robert D. (2000). "Discrete Fulleride Anions and Fullerenium Cations". Chemical Reviews. 100 (3): 1075–1120. doi:10.1021/cr980017o. PMID 11749258. S2CID 40552372.

- ^ a b c d e f Catherine E. Housecroft; Alan G. Sharpe (2008). "Chapter 14: The group 14 elements". Inorganic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Pearson. ISBN 978-0-13-175553-6.

- ^ a b Jonathan W. Steed & Jerry L. Atwood (2009). Supramolecular Chemistry (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-51233-3.

- ^ Rodríguez-Fortea, Antonio; Balch, Alan L.; Poblet, Josep M. (2011). "Endohedral metallofullerenes: a unique host–guest association". Chem. Soc. Rev. 40 (7): 3551–3563. doi:10.1039/C0CS00225A. PMID 21505658.

- ^ Ryuichi, Mitsumoto (1998). "Electronic Structures and Chemical Bonding of Fluorinated Fullerenes Studied". J. Phys. Chem. A. 102 (3): 552–560. Bibcode:1998JPCA..102..552M. doi:10.1021/jp972863t.

- ^ Shang, Yuchen; Liu, Zhaodong; Dong, Jiajun; Yao, Mingguang; Yang, Zhenxing; Li, Quanjun; Zhai, Chunguang; Shen, Fangren; Hou, Xuyuan; Wang, Lin; Zhang, Nianqiang (November 2021). "Ultrahard bulk amorphous carbon from collapsed fullerene". Nature. 599 (7886): 599–604. Bibcode:2021Natur.599..599S. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03882-9. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 34819685. S2CID 244643471. Archived from the original on 2021-11-26. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- ^ a b c Taylor, Roger; Parsons, Jonathan P.; Avent, Anthony G.; Rannard, Steven P.; Dennis, T. John; Hare, Jonathan P.; Kroto, Harold W.; Walton, David R. M. (23 May 1991). "Degradation of C60 by light" (PDF). Nature. Vol. 351.

- ^ a b Grohn, Kristopher J. "Comp grad leads research". WeyburnReview. Archived from the original on 2021-04-17. Retrieved 2021-04-17.

- ^ a b c d Grohn, Kristopher J.; et al. "C60 in olive oil causes light-dependent toxicity" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-04-15. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ^ a b Baati, Tarek; Moussa, Fathi (June 2012). "The prolongation of the lifespan of rats by repeated oral administration of [60]fullerene". Biomaterials. 33 (19): 4936–4946. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.03.036. PMID 22498298.

- ^ Shipkowski, K. A.; Sanders, J. M.; McDonald, J. D.; Walker, N. J.; Waidyanatha, S. (2019). "Disposition of fullerene C60 in rats following intratracheal or intravenous administration". Xenobiotica; the Fate of Foreign Compounds in Biological Systems. 49 (9): 1078–1085. doi:10.1080/00498254.2018.1528646. PMC 7005847. PMID 30257131.

- ^ Grohn KJ, Moyer BS, Moody KJ (2021). "C60 in olive oil causes light-dependent toxicity and does not extend lifespan in mice". GeroScience. 49 (2): 579–591. doi:10.1007/s11357-020-00292-z. PMC 8110650. PMID 33123847.

- ^ Hui M, Jia X, Shi M (2023). "Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Effects of Liposoluble C60 at the Cellular, Molecular, and Whole-Animal Levels". Journal of Inflammation Research. 16: 83–89. doi:10.2147/JIR.S386381. PMC 8110650. PMID 36643955.

Bibliography

[edit]- Katz, E.A. (2006). "Fullerene Thin Films as Photovoltaic Material". In Sōga, Tetsuo (ed.). Nanostructured materials for solar energy conversion. Elsevier. pp. 361–443. ISBN 978-0-444-52844-5.

Further reading

[edit]- Kroto, H. W.; Heath, J. R.; O'Brien, S. C.; Curl, R. F.; Smalley, R. E. (November 1985). "C60: Buckminsterfullerene". Nature. 318 (14): 162–163. Bibcode:1985Natur.318..162K. doi:10.1038/318162a0. S2CID 4314237. – describing the original discovery of C60

- Hebgen, Peter; Goel, Anish; Howard, Jack B.; Rainey, Lenore C.; Vander Sande, John B. (2000). "Fullerenes and Nanostructures in Diffusion Flames" (PDF). Proceedings of the Combustion Institute. 28: 1397–1404. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.574.8368. doi:10.1016/S0082-0784(00)80355-0. – report describing the synthesis of C

60 with combustion research published in 2000 at the 28th International Symposium on Combustion

External links

[edit]- History of C60's discovery carried out by the Chemistry Department at Bristol University

- A brief overview of buckminsterfullerene described by the University of Wisconsin-Madison

- A report by Ming Kai College detailing the properties of buckminsterfullerene

- Donald R. Huffman and Wolfgang Krätschmer's paper pertaining to the synthesis of C

60 in Nature published in 1990 - A thorough description of C

60 by the Oak Ridge National Laboratory - An article about buckminsterfullerene on Connexions Science Encyclopaedia

- Extensive statistical data compiled by the University of Sussex on the numerical quantitative properties of buckminsterfullerene

- A web portal dedicated to buckminsterfullerene, authored and supported by the University of Bristol

- Another web portal dedicated to buckminsterfullerene, authored and supported by the Chemistry Department at the University of Bristol

- A brief article entirely devoted to C

60 and its discovery, structure, production, properties, and applications - American Chemical Society's complete article on buckminsterfullerene

- Buckminsterfullerene at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)