Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Carpet

View on Wikipedia

A carpet or rug is a textile floor covering typically consisting of an upper layer of pile attached to a backing. The pile was traditionally made from wool, but since the 20th century synthetic fibres such as polypropylene, nylon, and polyester have often been used, as these fibres are less expensive than wool. The pile usually consists of twisted tufts that are typically heat-treated to maintain their structure. The terms carpet and rug are sometimes interchangeable, though carpet generally refers to wall-to-wall carpet, which is fastened to the floor and cut to fit a specific room, while rugs or mats are usually loose-laid and free-floating floor coverings smaller than an entire room.[1]

Carpet flooring provides cushioning for sitting and kneeling, and it is significantly less cold to the touch than tile or other stone. Walking on carpet does not produce much sound, and carpet dampens ambient noise. Carpet is versatile and is often decorated with patterns and motifs, which can add color and texture to a room. Carpeting has been produced throughout history; today, a wide range of carpets and rugs are available at various prices and quality levels, from inexpensive, mass-produced synthetic carpets to costly hand-knotted wool rugs.

Carpets can be produced through various methods, including weaving, needle felting, hand-knotting (as seen in oriental rugs), tufting (where pile is injected into a backing material), flat weaving, hooking (by pulling wool or cotton through the meshes of a sturdy fabric), or embroidering. Carpet is commonly made in widths of 12 or 15 feet (3.7 or 4.6 m) in the US and 4 or 5 m (13 or 16 ft) in Europe. To create wall-to-wall carpet, since the 19th and 20th century, different widths of carpet are seamed (using seam tape) or sewn together and fastened to the floor over a cushioned underlay (pad) using nails, tack strips (known in the UK as gripper rods), adhesives, or occasionally decorative metal stair rods.

Etymology and usage

[edit]

The term carpet comes from Latin carpita and Old French carpite.[2] One derivation of the term states that the French term came from the Old Italian carpita, from the verb carpire meaning 'to pluck'.[1][3] The Online Etymology Dictionary states that the term carpet was first used in English in the late 13th century, with the meaning 'coarse cloth', and by the mid-14th century, "tablecloth, [or] bedspread".[4] The word comes from Old French carpite 'heavy decorated cloth, carpet', from Medieval Latin or Old Italian carpita 'thick woolen cloth', which may derive from Latin carpere 'to card, pluck'.[4] The Latin word "carpet" was introduced in the 13th century by the Florentines from the Middle Armenian word կարպետ (carpet). The meaning of the term carpet shifted in the 15th century to refer to floor coverings.[4]

The terms carpet and rug are often used interchangeably. A carpet is sometimes defined as stretching from wall to wall.[5] Another definition treats rugs as of lower quality or of smaller size, with carpets quite often having finished ends. A third common definition is that a carpet is permanently fixed in place while a rug is simply laid out on the floor. Historically, the term carpet was also applied to table and wall coverings, as carpets were not commonly used on the floor in European interiors until the 15th century.[citation needed][6]

The term rug was first used in English in the 1550s, with the meaning 'coarse fabric'. The term is of Scandinavian origin, comparable to Norwegian rugga 'coarse coverlet', from Old Norse rogg 'shaggy tuft', from Proto-Germanic *rawwa-.[7] The meaning of rug "evolved to 'coverlet, wrap' (1590s), then 'mat for the floor' (1808)".[7]

Techniques

[edit]

Woven

[edit]A woven carpet is produced on a loom quite similar to woven fabric. The pile can be plush or Berber. Plush carpet is a cut pile and Berber carpet is a loop pile. There are new styles of carpet combining the two styles called cut and loop carpeting. Normally many coloured yarns are used and this process is capable of producing intricate patterns from predetermined designs (although some limitations apply to certain weaving methods with regard to accuracy of pattern within the carpet). These carpets are usually the most expensive due to the relatively slow speed of the manufacturing process. Countries such as Turkey, Iran, India, and Pakistan as well as the Middle East in general are well known for their woven carpets.[8][9][10]

Flatweave

[edit]A flatweave carpet is created by interlocking warp (vertical) and weft (horizontal) threads. Types of oriental flat woven carpet include kilim, soumak, plain weave, and tapestry weave. Types of European flat woven carpets include Venetian, Dutch, Damask carpet[11] , list, haircloth, and ingrain (aka double cloth, two-ply, triple cloth, or three-ply).[citation needed]

Knotted

[edit]

On a knotted pile carpet (formally, a "supplementary weft cut-loop pile" carpet), the structural weft threads alternate with a supplementary weft that rises at right angles to the surface of the weave. This supplementary weft is attached to the warp by one of three knot types (see below), such as the shag carpet, which was popular in the 1970s, to form the pile or nap of the carpet. Knotting by hand is most prevalent in oriental rugs and carpets. Kashmir carpets are also hand-knotted. Pile carpets, like flat carpets, can be woven on a loom. Both vertical and horizontal looms have been used in the production of European and oriental carpets. The warp threads are set up on the frame of the loom before weaving begins. A number of weavers may work together on the same carpet. A row of knots is completed and cut. The knots are secured with (usually one to four) rows of weft. The warp in woven carpet is usually cotton and the weft is jute.[citation needed]

There are several styles of knotting, but the two main types of knot are the symmetrical (also called Turkish or Ghiordes) and asymmetrical (also called Persian or Senna). Contemporary centres of knotted carpet production are: Lahore and Peshawar (Pakistan), Kashmir (India), Mirzapur and Bhadohi (India),[12] Tabriz (Iran), Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Turkey, Northern Africa, Nepal, Spain, Turkmenistan, and Tibet. The importance of carpets in the culture of Turkmenistan is such that the national flag features a vertical red stripe near the hoist side, containing five carpet guls (designs used in producing rugs). Kashmir and bhadohi is known for hand knotted carpets of silk or wool.[citation needed]

Tufted

[edit]

These are carpets that have their pile injected with the help of tufting gun into a backing material, which is itself then bonded to a secondary backing made of a woven hessian weave or a man made alternative to provide stability. The pile is often sheared in order to achieve different textures. This is the most common method of manufacturing of domestic carpets for floor covering purposes in the world.[citation needed]

Hooked

[edit]A hooked rug is a simple type of rug handmade by pulling strips of cloth such as wool or cotton through the meshes of a sturdy fabric such as burlap. This type of rug is now generally made as a handicraft. The process of creating a hooked rug is called rug hooking.[13]

Embroidery

[edit]Unlike woven carpets, embroidery carpets are not formed on a loom. Their pattern is established by the application of stitches to a cloth (often linen) base. The tent stitch and the cross stitch are two of the most common. Embroidered carpets were traditionally made by royal and aristocratic women in the home, but there has been some commercial manufacture since steel needles were introduced (earlier needles were made of bone) and linen weaving improved in the 16th century. Mary, Queen of Scots, is known to have been an avid embroiderer. 16th century designs usually involve scrolling vines and regional flowers (for example, the Bradford carpet). They often incorporate animal heraldry and the coat of arms of the maker. Production continued through the 19th century. Victorian embroidered carpet compositions include highly illusionistic, 3-dimensional flowers. Patterns for tiled carpets made of a number of squares, called Berlin wool work, were introduced in Germany in 1804, and became extremely popular in England in the 1830s. Embroidered carpets can also include other features such as a pattern of shapes, or they can even tell a story.[citation needed]

Needle felt

[edit]Needle felt carpets are more technologically advanced. These carpets are produced by intermingling and felting individual synthetic fibres using barbed and forked needles forming an extremely durable carpet. These carpets are normally found in commercial settings where there is frequent traffic, such as hotels and restaurants.[citation needed]

Fibres and yarns

[edit]

Carpet can be formulated from many single or blended natural and synthetic fibres. Fibres are chosen for durability, appearance, ease of manufacture, and cost. In terms of scale of production, the dominant yarn constructions are polyamides (nylons) and polypropylene with an estimated 90% of the commercial market.[14]

Nylon

[edit]Since the 20th century, nylon has been one of the most common materials for the construction of carpets. Both nylon 6 and nylon 6-6 are used. Nylon can be dyed topically or dyed in a molten state (solution dying). Nylon can be printed easily and has excellent wear characteristics. Due to nylon's excellent wear-resistance, it is widely used in industrial and commercial carpeting. In carpets, nylon tends to stain easily due to the presence of dye sites. These dye sites need to be filled in order to give nylon carpet any type of stain resistance. As nylon is petroleum-based it varies in price with the price of oil.[citation needed]

Polypropylene

[edit]Polypropylene, a polyolefin stiffer than the cheaper polyethylene, is used to produce carpet yarns because it is still less expensive than the other materials used for carpets. It is difficult to dye and does not wear as well as wool or nylon. Polypropylene, sometimes referred to simply as "olefin", is commonly used to construct berber carpets. Large looped olefin berber carpets are usually only suited for light domestic use and tend to mat down quickly. Berber carpets with smaller loops tend to be more resilient and retain their new appearance longer than large looped berber styles. Commercial grade level-loop carpets have very small loops, and commercial grade cut-pile styles can be well constructed. When made with polypropylene, commercial grade styles wear very well, making them very suitable for areas with heavy foot traffic such as offices. Polypropylene carpets are known to have good stain resistance, but not against oil-based agents. If a stain does set, it can be difficult to clean. Commercial grade carpets can be glued directly to the floor or installed over a 1⁄4 inch (6.4 mm) thick, 8-pound (3.6 kg) density padding. Outdoor grass carpets are usually made from polypropylene.[citation needed]

Wool and wool-blends

[edit]

Wool has excellent durability, can be dyed easily and is fairly abundant. When blended with synthetic fibres such as nylon the durability of wool is increased. Blended wool yarns are extensively used in production of modern carpet, with the most common blend being 80% wool to 20% synthetic fibre, giving rise to the term "80/20". Wool is relatively expensive and consequently, it only comprises a small portion of the market.[citation needed]

Polyester

[edit]The polyester known as "PET" (polyethylene terephthalate) is used in carpet manufacturing in both spun and filament constructions. After the price of raw materials for many types of carpet rose in the early 2000s, polyester became more competitive. Polyester has good physical properties and is inherently stain-resistant because it is hydrophobic, however oil-based stains can pose a problem for this type of material and it can be prone to soiling. Similar to nylon, colour can be added after production or it can be infused in a molten state (solution dyeing). Polyester has the disadvantage that it tends to crush or mat down easily. It is typically used in mid- to low-priced carpeting.[citation needed]

Another polyester, "PTT" (Polytrimethylene terephthalate), also called Sorona or 3GT (Dupont) or Corterra (Shell), is a variant of PET. Lurgi Zimmer PTT was first patented in 1941, but it was not produced until the 1990s, when Shell Chemicals developed the low-cost method of producing high-quality 1,3 propanediol (PDO), the starting raw material for PTT Corterra Polymers. DuPont subsequently commercialized a biological process for making 1,3-propanediol from corn syrup, imparting significant renewable content on the corresponding Sorona polyester carpet fibres.[15] These carpet fibres have resiliency comparable to nylon.[16]

Acrylic

[edit]Acrylic is a synthetic material first created by the Dupont Corporation in 1941 but has gone through various changes since it was first introduced. In the past, acrylic carpet used to fuzz or "pill" easily. This happened when the fibres degraded over time and short strands broke away with contact or friction. Over the years, new types of acrylics have been developed to alleviate some of these problems, although the issues have not been completely removed. Acrylic is fairly difficult to dye but is colourfast, washable, and has the feel and appearance of wool, making it a good rug fabric.[citation needed]

History

[edit]

The knotted pile carpet probably originated in the Caspian Sea area (Northern Iran),[18] or the Armenian Highland.[19] although there is evidence of goats and sheep being sheared for wool and hair which was spun and woven as far back at the 7th millennium.[citation needed]

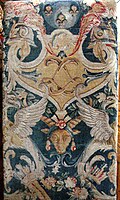

The earliest surviving pile carpet is the "Pazyryk carpet", which dates from the 5th-4th century BC. It was excavated by Sergei Ivanovich Rudenko in 1949 from a Pazyryk burial mound in the Altai Mountains in Siberia. This richly coloured carpet is 200 cm × 183 cm (6 ft 7 in × 6 ft 0 in) and framed by a border of griffins.[21]

Although claimed by many cultures, this square tufted carpet, almost perfectly intact, is considered by many experts to be of Caucasian, specifically Armenian, origin. The rug is woven using the Armenian double knot, and the red filaments' colour was made from Armenian cochineal.[22][23] The eminent authority of ancient carpets, Ulrich Schurmann, says of it, "From all the evidence available I am convinced that the Pazyryk rug was a funeral accessory and most likely a masterpiece of Armenian workmanship".[24] Gantzhorn concurs with this thesis. At the ruins of Persepolis in Iran where various nations are depicted as bearing tribute, the horse design from the Pazyryk carpet is the same as the relief depicting part of the Armenian delegation.[19] The historian Herodotus writing in the 5th century BC also informs us that the inhabitants of the Caucasus wove beautiful rugs with brilliant colours which would never fade.[25]

Afghanistan

[edit]There has recently been a surge in demand for Afghan carpets, although many Afghan carpet manufacturers market their products under the name of a different country.[26] The carpets are made in Afghanistan, as well as by Afghan refugees who reside in Pakistan and Iran. Famous Afghan rugs include the Shindand or Adraskan (named after local Afghan villages), woven in the Herat area in western Afghanistan.[citation needed]

Afghan carpets are commonly known as Afghan rugs. Afghan carpets are a unique and widely recognised handmade material design that originates from Afghanistan. They often exhibit intricate detailing, mainly using traditional tribal designs originating from the Turkmens, Kazakhs, Balochs, and Uzbeks. The handmade rugs come in many patterns and colours, yet the traditional and most common example of Afghan carpet is the octagon-shaped elephant-foot (Bukhara). The rugs with this print are most commonly red in colour. Many dyes, such as vegetable dyes, are used to impart rich colour.[citation needed]

Armenia

[edit]Various rug fragments have been excavated in Armenia dating back to the 7th century BC or earlier. The oldest single surviving knotted carpet in existence is the Pazyryk carpet, excavated from a frozen tomb in Siberia, dated from the 5th to the 3rd century BC, now in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. This square tufted carpet, almost perfectly intact, is considered by many experts to be of Caucasian, specifically Armenian, origin. The eminent authority of ancient carpets, Ulrich Schurmann, says of it, "From all the evidence available I am convinced that the Pazyryk rug was a funeral accessory and most likely a masterpiece of Armenian workmanship".[27] Gantzhorn concurs with this thesis. At the ruins of Persepolis in Iran where various nations are depicted as bearing tribute, the horse design from the Pazyryk carpet is the same as the relief depicting part of the Armenian delegation. Armenian carpets were renowned by foreigners who travelled to Artsakh; the Arab geographer and historian Al-Masudi noted that, among other works of art, he had never seen such carpets elsewhere in his life.[28]

Art historian Hravard Hakobyan notes that "Artsakh carpets occupy a special place in the history of Armenian carpet-making."[29] Common themes and patterns found on Armenian carpets were the depiction of dragons and eagles. They were diverse in style, rich in colour and ornamental motifs, and were even separated in categories depending on what sort of animals were depicted on them, such as artsvagorgs (eagle-carpets), vishapagorgs (dragon-carpets) and otsagorgs (serpent-carpets).[29] The rug mentioned in the Kaptavan inscriptions is composed of three arches, "covered with vegatative ornaments", and bears an artistic resemblance to the illuminated manuscripts produced in Artsakh.[29]

The art of carpet weaving was in addition intimately connected to the making of curtains as evidenced in a passage by Kirakos Gandzaketsi, a 13th-century Armenian historian from Artsakh, who praised Arzu-Khatun, the wife of regional prince Vakhtang Khachenatsi, and her daughters for their expertise and skill in weaving.[30]

According to ancient perceptions, the carpet is the universe where, according to mythological conceptions, there is

- The sacred center

- The cosmic space

- The zone demarcating and protecting the universe.[31]

Azerbaijan

[edit]The Gultapin excavations discovered several carpet weaving tools which date back to the 4th-3rd millennium BC. According to Iranica Online, "The main weaving zone was in the eastern TransCaucasus south of the mountains that bisect the region diagonally, the area now comprised in the Azerbaijan SSR; it is the homeland of a Turkic population known today as Azeri. Other ethnic groups also practiced weaving, some of them in other parts of the Caucasus, but they were of lesser importance."[32] Azerbaijan was one of the most important centers of carpet weaving; as a result, several different schools have evolved. While traditionally schools are divided into four main branches, each region has its own version of the carpets. The schools are divided into four main branches: Kuba-Shirvan, Ganja-Kazakh carpet-weaving school, Baku carpet school, and Karabakh school of carpet weaving.[33] Carpet weaving is a family tradition in Azerbaijan that is transferred verbally and with practice, and is associated with the daily life and customs of its people. A variety of carpet and rug types are made in Azerbaijan such as silk, wool, gold and silver threads, pile and pileless carpets, as well as kilim, sumakh, zili, verni, mafrashi and khurjun. In 2010, the traditional art of Azerbaijani carpet weaving was added to the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity of UNESCO.[34][33]

Balochi

[edit]Balochi Rugs (Balochi:قالی بلوچ، فرش بلوچ) are a group of carpets that are woven by the Baloch tribes.[35] The size of Baloch rugs are eight feet in length, which made them lighter and easier to transport.[36] Their material typically include of wool or a mixture of wool and goat hair, newer carpets have a warp made of cotton and sturdy wool pile rugs.[citation needed]

Baloch rugs tend to be a dark combination of reds, browns, and blues, with touches of white and their material often includes wool or a mixture of wool and goat hair; newer carpets have a warp made of cotton and sturdy wool pile rugs.[citation needed]

Nature, animal figurines, religious beliefs in Baluch prayer rugs, and objects of interest and use by the people of the tribe and the villagers are visualized in these designs. They are mostly designed geometrically with lines and surfaces, creating abstract and non-abstract patterns.[citation needed]

Mehrabi is a prayer rug designed in the Balochi style, and it typically features a mihrab or arch at one end of the rug.[citation needed]

China

[edit]As opposed to most antique rug manufacturing practices, early Chinese carpets were woven almost exclusively for internal consumption.[37] China has a long history of exporting traditional goods; however, it was not until the first half of the 19th century that the Chinese began to export their rugs. Once in contact with western influences, there was a large change in production: Chinese manufacturers began to produce art deco rugs with commercial look and price point. The centuries-old Chinese textile industry is rich in history. While most antique carpets are classified according to a specific region or manufactory, scholars attribute the age of any specific Chinese rug to the ruling emperor of the time. The earliest surviving examples of the craft were produced during the time of Chen Shubao, the last emperor of the Chen dynasty.[citation needed]

India

[edit]Carpet weaving may have been introduced into the area as far back as the 11th century with the coming of the first Muslim conquerors, the Ghaznavids and the Ghurids, from the West. It can with more certainty be traced to the beginning of the Mughal Empire in the early 16th century, when the last successor of Timur, Babur, extended his rule from Kabul to India to found the Mughal Empire. Under the patronage of the Mughals, Indian crafters adopted Persian techniques and designs. Carpets woven in the Punjab made use of motifs and decorative styles found in Mughal architecture.[citation needed]

Akbar, a Muhal emperor, is credited with introducing the art of carpet weaving to India during his reign. The Mughal emperors patronized Persian carpets for their royal courts and palaces. During this period, he brought Persian crafters from their homeland and established them in India. Initially, these Mughal carpets showed the classic Persian style of fine knotting, then gradually the style blended with Indian art. Thus the carpets produced became typical of Indian origin and the industry began to diversify and spread all over the subcontinent. During the Mughal period, carpets made on the Indian subcontinent became so famous that demand for them spread abroad. These carpets had distinctive designs and boasted a high density of knots. Carpets made for the Mughal emperors, including Jahangir and Shah Jahan, were of the finest quality. Under Shah Jahan's reign, Mughal carpet weaving took on a new aesthetic and entered its classical phase.[citation needed] Indian carpets are well known for their designs with attention to detail and presentation of realistic attributes. The carpet industry in India flourished more in its northern part, with major centres found in Kashmir, Jaipur, Agra and Bhadohi.[citation needed]

Indian carpets are known for their high density of knotting. Hand-knotted carpets are a speciality and widely in demand in the West. The carpet industry in India has been successful in establishing social business models that help underprivileged sections of the society. Notable examples of social entrepreneurship ventures are Jaipur rugs[38] and the Fabindia retail chain.[39]

Another category of Indian rugs which, though quite popular in most western countries, have not received much press, is hand-woven rugs of Khairabad (Citapore rugs). [citation needed] Khairabad, a small town in the Citapore (now spelled as "Sitapur") district of India had been ruled by Raja Mehmoodabad. Khairabad (Mehmoodabad Estate) was part of Oudh province which had been ruled by shi'i Muslims having Persian linkages. Citapore rugs made in Khairabad and neighbouring areas are hand-woven and distinct from tufted and knotted rugs. Flat weave is the basic weaving technique of Citapore rugs and generally cotton is the main weaving material here but jute, rayon, and chenille are also popular. IKEA and Agocha have been major buyers of rugs from this area.[citation needed]

Iran

[edit]Iranian carpet is derived from Persian art and culture. Carpet-weaving in Persia dates back to the Bronze Age. The earliest surviving corpus of Persian carpets comes from the Safavid dynasty (1501–1736) in the 16th century.[40] However, painted depictions prove a longer history of production. There is much variety among classical Persian carpets of the 16th and 17th centuries. Common motifs include scrolling vine networks, arabesques, palmettes, cloud bands, medallions, and overlapping geometric compartments rather than animals and humans.[citation needed] This is because Islam, the dominant religion in that part of the world, forbids their depiction.[citation needed] Still, some show figures engaged either in the hunt or feasting scenes. The majority of these carpets are wool, but several silk examples produced in Kashan survive.[41]

Iran is also the world's largest producer and exporter of handmade carpets, producing three-quarters of the world's total output and having a share of 30% of world's export markets.[42][43] The world's largest hand-woven carpet was produced by Iran Carpet Company (ICC) at the order of the Diwan of the Royal Court of Sultanate of Oman to cover the entire floor of the main praying hall of the Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosque (SQGM) in Muscat.[44]

Pakistan

[edit]The art of weaving developed in South Asia at a time when few other civilizations employed it. Excavations at Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro, ancient cities of the Indus Valley civilization, have established that the inhabitants used spindles and spun a wide variety of weaving materials. Some historians consider that the Indus Valley civilization first developed the use of woven textiles. As of the late 1990s, hand-knotted carpets were among Pakistan's leading export products and their manufacture is the second largest cottage and small industry. Pakistani craftsmen have the capacity to produce any type of carpet using all the popular motifs of gulls, medallions, paisleys, traceries, and geometric designs in various combinations.[45] At the time of independence, manufacturing of carpets was set up in Sangla Hill, a small town of Sheikhupura District. Chaudary Mukhtar Ahmad Member, son of Maher Ganda, introduced and taught this art to locals and immigrants. He is considered founder of this industry in Pakistan. Sangla Hill is now a focal point of the carpet industry in Pakistan. Almost all the exporters and manufacturers who are running their business at Lahore, Faisalabad, and Karachi have their area offices in Sangla Hill.[citation needed]

In Pakistan, multiple material types are used including: wool, silk and cotton or jute etc. Carpet textures are typically soft and light in Pakistan.[citation needed]

Scandinavia

[edit]Scandinavian rugs are among the most popular of all weaves in modern design. Preferred by influential modernist thinkers, designers, and advocates for a new aesthetic in the mid-twentieth century, Scandinavian rugs have become widespread in many different avenues of contemporary interior design. With a long history of adaptation and evolution, the tradition of Scandinavian rug-making is among the most storied of all European rug-making traditions.[citation needed]

Turkey

[edit]

Turkish carpets (also known as Anatolian), whether hand knotted or flat woven, are among the most well-known and established handcrafted artworks in the world.[46] Historically: religious, cultural, environmental, sociopolitical and socioeconomic conditions created widespread utilitarian need and have provided artistic inspiration among the many tribal peoples and ethnic groups in Central Asia and Turkey.[47] Turks, nomadic or pastoral, agrarian or town dwellers, living in tents or in sumptuous houses in large cities, have protected themselves from the extremes of the cold weather by covering the floors, and sometimes walls and doorways, with carpets and rugs. The carpets are always hand made of wool or sometimes cotton, with occasional additions of silk. These carpets are natural barriers against the cold. Turkish pile rugs and kilims are also frequently used as tent decorations, grain bags, camel and donkey bags, ground cushions, oven covers, sofa covers, bed and cushion covers, blankets, curtains, eating blankets, table top spreads, prayer rugs and for ceremonial occasions.[citation needed]

The oldest records of flat woven kilims come from Çatalhöyük Neolithic pottery, circa 7000 B.C. One of the oldest settlements ever to have been discovered, Çatalhöyük is located south east of Konya in the middle of the Anatolian region.[48] The excavations to date (only three percent of the town) not only found carbonized fabric but also fragments of kilims painted on the walls of some of the dwellings. The majority of them represent geometric and stylized forms that are similar or identical to other historical and contemporary designs.[49]

The knotted rug is believed to have reached Asia Minor and the Middle East with the expansion of various nomadic tribes peoples during the latter period of the great Turkic migration of the 8th and 9th centuries. Famously depicted in European paintings of The Renaissance, beautiful Anatolian rugs were often used from then until modern times, to indicate the high economic and social status of the owner.[citation needed]

Women learn their weaving skills at an early age, taking months or even years to complete the beautiful pile rugs and flat woven kilims that were created for their use in every aspect of daily life. As is true in most weaving cultures, traditionally and nearly exclusively, it is women and girls who are both artisan and weaver.[50][51][52]

Turkmen

[edit]

Türkmen carpet (also called "Bukhara Uzbekistan") is a type of handmade floor-covering textile traditionally originating in Central Asia. It is useful to distinguish between the original Turkmen tribal rugs and the rugs produced in large numbers for export in the 2000s, mainly in Pakistan and Iran. The original Turkmen rugs were produced by the Turkmen tribes who are the main ethnic group in Turkmenistan and are also found in Afghanistan and Iran. They are used for various purposes, including tent rugs, door hangings and bags of various sizes.[53]

Uyghur

[edit]Weaving was traditionally done by men in Uyghur society. Scholars speculate that when the Mongols invaded northwest China in the 13th century, under the leadership of General Subutai, they may have taken as captives some of these skilled carpet weavers.[54]

Europe

[edit]

Oriental imports

[edit]Oriental carpets began to appear in Europe after the Crusades in the 11th century, due to contact by Crusaders with Eastern traders. Until the mid-18th century they were mostly used on walls and tables. Except in royal or ecclesiastical settings, they were considered too precious to cover the floor. Starting in the 13th century, oriental carpets begin to appear in paintings (notably from Italy, Flanders, England, France, and the Netherlands). Carpets of Indo-Persian design were introduced to Europe via the Dutch, British, and French East India Companies of the 17th and 18th century[55] and in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth by Armenian merchants (Polish carpets or Polonaise carpets).[17]

Spain

[edit]Although isolated instances of carpet production pre-date the Muslim invasion of Spain, the Hispano-Moresque examples are the earliest significant body of European-made carpets. Documentary evidence shows production beginning in Spain as early as the 10th century AD. The earliest extant Spanish carpet, the so-called Synagogue carpet in the Museum of Islamic Art, Berlin, is a unique survival dated to the 14th century. The earliest group of Hispano-Moresque carpets, Admiral carpets (also known as armorial carpets), has an all-over geometric, repeat pattern punctuated by blazons of noble Christian Spanish families. The variety of this design was analyzed most thoroughly by May Beattie. Many of the 15th century Spanish carpets rely heavily on designs originally developed on the Anatolian Peninsula.[citation needed] Carpet production continued after the Reconquest of Spain and eventual expulsion of the Muslim population in the 15th century. Sixteenth century Renaissance Spanish carpet design is a derivative of silk textile design. Some of the most popular motifs are wreaths, acanthus leaves and pomegranates.[citation needed]

During the Moorish (Muslim) period, production took place in Alcaraz in the province of Albacete, as well as being recorded in other towns. Carpet production after the Christian reconquest continued in Alcaraz while Cuenca, first recorded as a weaving centre in the 12th century, became increasingly important, and was dominant in the 17th and early 18th century. Carpets of completely different French-based designs began to be woven in a royal workshop, the Royal Tapestry Factory (Real Fábrica de Tapices de Santa Bárbara) in Madrid in the 18th century. Cuenca was closed down by the royal degree of Carlos IV in the late 18th century to stop it competing with the new workshop. Madrid continued as a weaving centre through to the 20th century, producing brightly coloured carpets, most of whose designs are strongly influenced by French carpet design, and which are frequently signed (on occasions with the monogram MD; also sometimes with the name Stuyck) and dated in the outer stripe. After the Spanish Civil War General Franco revived the carpet weaving industry in workshops named after him, weaving designs that are influenced by earlier Spanish carpets, usually in a very limited range of colours.[56]

Serbia

[edit]Pirot carpet[a] (Serbian: Пиротски ћилим, Pirotski ćilim) refers to a variety of flat tapestry-woven carpets or rugs traditionally produced in Pirot, a town in southeastern Serbia. Pirot kilims with some 122 ornaments and 96 different types have been protected by geographical indication in 2002. They are one of the most important traditional handicrafts in Serbia. In the late 19th century and up to the Second World War, Pirot kilims have been frequently used as insignia of Serbian and Yugoslav royalty. This tradition was revived in 2011 when Pirot kilims were reintroduced for state ceremonies in Serbia. Carpet weaving in Pirot dates back to the Middle Ages.[57][full citation needed] One of the first mentions of the Pirot kilim in written sources date to 1565, when it was said that the šajkaši boats on the Danube and Drava were covered with Pirot kilims. Pirot was once the most important rug-making centre in the Balkans. Pirot is located on the historical main highway which linked central Europe with Constantinople. Pirot was also known as Şarköy in Turkish. The Pirot carpet varieties are also found in Bulgaria and Turkey, and in many other international collections. One of the chief qualities are the colour effects achieved through the choice and arrangement of colours.[citation needed]

In the beginning of the 19th century, plant dyes were replaced by aniline colourings. "The best product of the country is the Pirot carpet, worth about ten shillings a square metre. The designs are extremely pretty, and the rugs, without being so heavy as the Persian, or so ragged and scant in the web and weft as Caramanian, wear for ever. The manufacture of these is almost entirely confined to Pirot. From Pirots old Turkish signification as Şarköy stems the traditional trade name of the rugs as Şarköy-kilims. Stemming from the homonym to the today's Turkish settlement of Şarköy in Thracia, which had no established rug making tradition, Şarköys are often falsely ascribed to originate from Turkey. Also in the rug-selling industry, Şarköy are mostly labeled as being of oriental or Turkish origin as to easier sell them to non-familiar customers as they prefer rugs with putative oriental origin. In fact, Şarköys have been established from the 17th century in the region of the Western Balkan or Stara Planina mountains in the towns of Pirot, Berkowiza, Lom, Chiprovtsi and Samokov. Later they have been also produced in Knjaževac and Caribrod.[citation needed]

Bulgaria

[edit]The Chiprovtsi carpet (Чипровци килим) is a type of handmade carpet with two absolutely identical sides, part of Bulgarian national heritage, traditions, arts and crafts. Its name is derived from the town of Chiprovtsi where their production started in the 17th century. The carpet weaving industry played a key role in the revival of Chiprovtsi in the 1720s after the devastation of the failed 1688 Chiprovtsi Uprising against Ottoman rule. The western traveller Ami Boué, who visited Chiprovtsi in 1836–1838, reported that "mainly young girls, under shelters or in corridors, engage in carpet weaving. They earn only five francs a month and the payment was even lower before". By 1868, the annual production of carpets in Chiprovtsi had surpassed 14,000 square metres. In 1896, almost 1,400 women from Chiprovtsi and the region were engaged in carpet weaving. In 1920, the locals founded the Manual Labour carpet-weaving cooperative society, the first of its kind in the country.[58] At present, the carpet (kilim) industry remains dominant in the town.[59] Carpets have been crafted according to traditional designs, but in recent years it is up to the customers to decide the pattern of the carpet they have ordered. The production of a single 3 by 4 m (9.8 by 13.1 ft) carpet takes about 50 days; primarily women engage in carpet weaving. Work is entirely manual and all used materials are natural; the primary material is wool, coloured using plant or mineral dyes. The local carpets have been prized at exhibitions in London, Paris, Liège and Brussels. In recent decades, however, the Chiprovtsi carpet industry has been in decline as it had lost its firm foreign markets. As a result, the town and the municipality have been experiencing a demographic crisis.[citation needed]

France

[edit]In 1608 Henry IV initiated the French production of "Turkish style" carpets under the direction of Pierre DuPont. This production was soon moved to the Savonnerie factory in Chaillot just west of Paris. The earliest, well-known group produced by the Savonnerie, then under the direction of Simon Lourdet, are the carpets that were produced in the early years of Louis XIV's reign. They are densely ornamented with flowers, sometimes in vases or baskets, against dark blue or brown grounds in deep borders. The designs are based on Netherlandish and Flemish textiles and paintings. The most famous Savonnerie carpets are the series made for the Grande Galerie and the Galerie d'Apollon in the Palais du Louvre between c. 1665 and c. 1685. These 105 masterpieces, made under the artistic direction of Charles Le Brun, were never installed, as Louis XIV moved the court to Versailles in 1688. Their design combines rich acanthus leaves, architectural framing, and mythological scenes (inspired by Cesare Ripa's Iconologie) with emblems of Louis XIV's royal power.[citation needed]

Pierre-Josse Joseph Perrot is the best-known of the mid-eighteenth-century carpet designers. His many surviving works and drawings display graceful rococo s-scrolls, central rosettes, shells, acanthus leaves, and floral swags. The Savonnerie manufactory was moved to the Gobelins in Paris in 1826.[60] The Beauvais manufactory, better known for their tapestry, also made knotted pile carpets from 1780 to 1792. Carpet production in small, privately owned workshops in the town of Aubusson began in 1743. Carpets produced in France employ the symmetrical knot.[56]

-

An 18th-century Savonnerie tapisserie at the Palace of Versailles

-

A Savonnerie loom

England

[edit]This section contains wording that promotes the subject in a subjective manner without imparting real information. (April 2025) |

Knotted pile carpet weaving technology was introduced to England in the early 16th century, likely by Flemish Calvinists who were fleeing religious persecution. Because many of these weavers settled in south-eastern England, particularly in Norwich, the fourteen extant 16th and 17th century carpets are sometimes referred to as "Norwich carpets". These works are either adaptations of Anatolian or Indo-Persian designs, or employ Elizabethan-Jacobean scrolling vines and blossoms; all but one are dated or bear a coat of arms. Like the French, English weavers used the symmetrical knot. There are documented and surviving examples of carpets from three 18th-century manufactories: Exeter (1756–1761, owned by Claude Passavant, 3 extant carpets), Moorfields (1752–1806, owned by Thomas Moore, 5 extant), and Axminster (1755–1835, owned by Thomas Whitty, numerous extant).[citation needed]

Exeter and Moorfields were both staffed with renegade weavers from the French Savonnerie and, therefore, employ the weaving structure of that factory and Perrot-inspired designs. Neoclassical designer Robert Adam supplied designs for both Moorfields and Axminster carpets based on Roman floor mosaics and coffered ceilings. Some of the most well-known rugs of his design were made for Syon House, Osterley House, Harewood House, Saltram House, and Newby Hall.[citation needed]

Axminster carpet

[edit]Axminster carpet was a unique floor covering first made in a factory founded at Axminster, Devon, in 1755 by the cloth weaver Thomas Whitty. Resembling somewhat the Savonnerie carpets produced in France, Axminster carpets were symmetrically knotted by hand in wool on woollen warps, and had a weft of flax or hemp. Like the French carpets, they often featured Renaissance architectural or floral patterns; others mimicked oriental patterns. Similar carpets were produced at the same time in Exeter and in the Moorfields area of London and, shortly before, at Fulham in Middlesex. The Whitty factory closed in 1835 with the advent of machine-made carpeting. The name Axminster, however, survived as a generic term for machine-made carpets whose pile is produced by techniques similar to those used in making velvet or chenille,[61] and Axminster Carpets resumed production at a new site in the town in 1937.[62]

Axminster carpets can use the three main types of broadloom carpet construction: machine-woven, tufted and hand-knotted. Machine-woven carpet is an investment that will last 20 or 30 years, and woven Axminster and Wilton carpets are still popular in areas where longevity and design flexibility are a big part of the purchasing decision. Hotels and leisure venues almost always choose these types, and many homes use woven Axminsters as design statements.[citation needed]

Machine-woven carpets like Axminster and Wilton are made by massive looms that weave together 'bobbins' of carpet yarn and backing. The finished result, which can be intricately patterned, creates a floor that provides supreme underfoot luxury with high performance. Tufted carpets are also popular in the home. They are relatively speedy to make: a pre-woven backing has yarns tufted into it. Needles push the yarn through the backing, which is then held in place with underlying "loopers". Tufted carpets can be twist pile, velvet, or loop pile. Twist pile carpets are produced when one or more fibres are twisted in the tufting process, so that in the finished carpet they appear to be bound together. Velvet pile carpets tend to have a shorter pile and a tighter construction, giving the finished article a smooth, velvety appearance. Loop pile carpets are renowned for being hard wearing and lend carpets great texture. The traditional domain of rugs from faraway continents, hand knotted squares and rugs use the expertise of weavers to produce work of the finest quality. Traditional rugs often feature a deliberate mistake on behalf of the weaver to guarantee their authenticity.[citation needed]

Six patterns of Axminster carpet are known as the Lansdowne group. These have a tripartite design with reeded circles and baskets of flowers in the central panel, flanked by diamond lozenges in the side panels. Axminster Rococo designs often have a brown ground and include birds copied from popular, contemporary engravings. Even today, a large percentage of the 55,000 population of the town still seek employment in the industry.[citation needed]

Brussels and Wilton carpets

[edit]The town of Wilton, Wiltshire is also known for its carpet weaving, which dates back to the 18th century.[63]

The Brussels loom was introduced into England towards the middle of the 18th century and marked the beginning of a new era in carpet-weaving. It was the first loom on which a pile carpet could be woven mechanically, the pile consisting of rows of loops, formed over wires inserted weftwise during weaving and subsequently withdrawn. Brussels was the first type of carpet to be woven in a loom incorporating the Jacquard pattern-selecting mechanism, and in 1849 power was applied to the loom by Biglow in the United States.[citation needed]

Later, when bladed wires were developed, the pile loops were severed on withdrawal of the wires to produce a carpet known as Wilton, and after this development the loom became known as the Wilton loom. In modern usage the designation Wilton applies to both cut-pile and loop-pile carpets made in this loom. The latter are now variously described as Brussels-Wilton, round wire Wilton, loop-pile Wilton, and round wired Jacquard. The methods of manufacture, including the principles of design, preparatory processes, and weaving, are the same in most respects for both Brussels and Wilton qualities. The chief difference between them is that whereas Brussels loop-pile is secured satisfactorily by the insertion of two picks of weft to each wire (2-shot), the Wilton cut-pile is woven more often with three picks of weft to each wire (3-shot) to ensure that the tufts are firmly secured in the carpet backing.[citation needed]

Brussels carpets have a smooth slightly ribbed surface and their patterning is well defined, a characteristic feature of the carpet. Closeness of pile rather than height contributes to their neat appearance and hard-wearing properties, although they do not simulate the luxury of cut-pile carpets. Brussels Wilton carpets were initially produced on 27-inch (3/4) looms and were sewn together by hand. The looms could incorporate up to five frames, each with a different colour, thus enabling figured or pattern carpets to be manufactured. With judicial and skilful planting of colours in the frames the number of colours could be increased to about twenty, enabling complex designs to be produced. Due to the additional costs in labour these carpets were normally only produced for the bespoke market.[citation needed]

After the First World War, the carpets started to be produced for the general market using popular designs and colourways but they always remained at the luxury end of the general market. The growing middle class of the twentieth century aspired to acquire a Wilton carpet for their 'best' room. Despite the impact of industrialization, the areas where Brussels Wilton carpets were produced remained centred around the towns of Wilton, Kidderminster in the West Midlands, and in West Yorkshire where the firm of John Crossley and Sons in Halifax became synonymous with carpet manufacture. There were smaller areas of manufacture in Scotland and Durham. With the development of different manufacturing methods and looms capable of the mass production of carpets, the public began change their décor, including carpets, on a regular basis, which increased the demand for carpets. The last quarter of the 20th century saw the rapid decline of the labour-intensive Brussels Wilton carpets. Very few of the original ¾ Wilton looms still exist, and the few that do are either in museums or used by small manufacturers that continue to produce custom made luxury carpets for the elite and to replace carpets in historic buildings in the UK and abroad.[64]

United States

[edit]The U.S. carpet industry began as early as the end of the 18th century but struggled to compete with imported carpets. Protective tariffs enacted by the United States Congress in 1816 and expanded in the 1820s helped protect the industry along with other textile industries. Surveys showed that the industry included 20 carpet mills that produced as much as 1 million square yards of carpet as of 1834 and 116 mills that produced 8 million square yards of carpets and rugs as of 1850, which increased to 215 mills that produced more than 20 million square yards, and employed 12,000 persons as of 1870. Handloom carpets used to dominate the industry, and it was only later that improvements in power loom technology allowed the industry to match the quality of handloom produced carpets.[65]

The city of Dalton, Georgia, where the majority of the carpet currently produced in the United States is manufactured, has come to be known as the "Carpet Capital of the World".[66] The U.S. carpet industry accounts for approximately 45% of the production of carpet in the world,[65] and, as of the turn of the 21st century, 85% to 90% of the carpet that makes up the U.S. carpet market was produced in and around Dalton.[65][67] The Dalton carpet industry traces its history to the work of Catherine Evans Whitener who revived the tufting technique for the production of textiles which she employed for the creation of tufted bedspreads.[66][68] Whitener inspired a cottage industry for tufting bedspreads centered on Dalton.[69]

In the 1930s, tufting became industrialized as bedspread manufacturing was moved to factories and the production process centralized and standardized. The industry moved from handmade production to adapting sewing machines. Eventually, the industry in Dalton began producing carpets.[68] During the New Deal era, the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act spawned a surge in the carpet industry in Dalton and adaptation of machine tufting to lower labor costs.[66]

Popularity of tufted carpets continued to increase in the 1950s with sales of cotton-made, tufted carpet surpassing the traditional wool-woven industry. By 1951, sales of the tufted carpet had reached 6 million yards per year and increased to 400 million yards per year by 1968. Carpet became the standard floor covering in most homes. Along with the rest of the US economy, the carpet industry began to slow in the 1970s. To adapt to the slowing economy, some firms in the industry began vertical integration by acquiring the production of raw materials all the way to finishing of carpets including the dyeing facilities.[65]

In the early 1980s, many companies in the industry shutdown with the number of carpet mills in operation reduced from 285 mills in 1980 to 100 mills in 1990.[65] In the late 1980s, the carpet industry in Dalton again experienced an economic boom with the industry's demand for labour reaching an all-time high.[70] By 1990, a few firms had consolidated the industry by acquiring their smaller competitors so that the top four firms accounted for 80% of the total production.[65] The Carpet and Rug Institute, the trade association which represents the carpet industry in the US is based in Dalton.[71] While Dalton remains a major carpet manufacturing centre in the U.S., the city has begun to expand its dominant industry to other products including becoming a significant producer of solar panels since passage of the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act.[72]

Modern carpeting and installation

[edit]

Carpet is commonly made in widths of 12 and 15 feet (3.7 and 4.6 m) in the US, 4 m and 5 m in Europe. Where necessary different widths can be seamed together with a seaming iron and seam tape (formerly it was sewn together) and it is fixed to a floor over a cushioned underlay (pad) using nails, tack strips (known in the UK as gripper rods), adhesives, or occasionally decorative metal stair rods, thus distinguishing it from rugs or mats, which are loose-laid floor coverings. For environmental reasons, the use of wool, natural bindings, natural padding, and formaldehyde-free glues is becoming more common. These options are almost always at a premium cost.[citation needed]

In the UK, some carpets are still manufactured for yachts, hotels, pubs and clubs in a narrow width of 27 inches (0.69 m) and then sewn to size. Carpeting which covers an entire room area is loosely referred to as 'wall-to-wall', but carpet can be installed over any portion thereof with use of appropriate transition moldings where the carpet meets other types of floor coverings. Carpeting is more than just a single item; it is, in fact, a system comprising the carpet itself, the carpet backing (often made of latex), the cushioning underlay, and a method of installation. Carpet tiles are also available, typically 50 centimetres (20 in) square. These are usually only used in commercial settings and are affixed using a special pressure-sensitive glue, which holds them into place while allowing easy removal (in an office environment, for example) or allowing rearrangement in order to spread wear.[73]

"Carpet binding" is a term used for any material being applied to the edge of a carpet to make a rug. Carpet binding is usually cotton or nylon, but also comes in many other materials such as leather. Non-synthetic binding is frequently used with bamboo, grass and wool rugs, but is often used with carpet made from other materials.[citation needed]

The GoodWeave labelling scheme used throughout Europe and North America assures that child labour has not been used: importers pay for the labels, and the revenue collected is used to monitor centres of production and educate previously exploited children.[74]

Disposal

[edit]For the year 2018 in the U.S., the recycling of carpet fibre, backing, and padding was 310,000 tons, which was 9.2 percent of carpet generation. A slightly larger proportion (17.8 percent) was combusted for energy recovery, while the majority of rugs and carpets were landfilled (73 percent).[75]

As of 2023 according to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) over four billion pounds (1,814,369 metric tonnes) of carpet enter the solid waste stream in the United States every year, accounting for more than one percent by weight and about two percent by volume of all municipal solid waste (MSW). Furthermore, according to EPA, "the bulky nature of carpet creates collection and handling problems for solid waste operations and the variety of materials present in carpet makes it difficult to recycle."[76]

In culture and figurative expressions

[edit]

There are many stories about magic carpets, legendary flying carpets that can be used to transport people who are on it instantaneously or quickly to their destination. Disney's Aladdin depicts a magic carpet found by Aladdin and Abu in the Cave of Wonders while trying to find Genie's lamp. Aladdin and Jasmine ride on the carpet to travel around the world. The term "magic carpet" is first attested in 1816.[4] From the 16th to the 19th century, the term "carpet" was used "...as an adjective often with a tinge of contempt, when used of men (as in carpet-knight, 1570s)", which meant a man who was associated with "...luxury, ladies' boudoirs, and drawing rooms".[4] Rolling out the red carpet is an expression that means to welcome a guest lavishly and handsomely. In some cases, an actual red carpet is used for VIPs and celebrities to walk on, such as at the Cannes Film Festival and when foreign dignitaries are welcomed to a country.

In 1820s British servant slang, to "carpet" someone means to call them for a reprimand.[4] To be called on the carpet means to be summoned for a serious reason, typically a scolding reprimand; this usage dates from 1900,[77] referring to the carpeted office of a person in authority, such as a schoolmaster or employer. A stronger variant of this expression, to be "hauled on the carpet", implies an even sterner reprimand. Carpet bombing is a type of bombing from airplanes which developed in the 20th century in which an entire city is bombed (rather than precise strikes on military targets). The slang expression "laugh at the carpet" means to vomit on the floor (especially a carpeted floor).[78] The expression "on the carpet" refers to a matter which is under discussion or consideration.[78] The term "carpet muncher" is a slang term for a lesbian and a reference to cunnilingus; this expression is first attested in 1992.[79]

The term carpet bag, which literally refers to a suitcase made from a piece of carpet, is used in several figurative contexts. The term gained a popular usage after the American Civil War to refer to carpetbaggers, Northerners who moved to the South after the war, especially during the Reconstruction era (1865–1877). Carpetbaggers allegedly politically manipulated and controlled former Confederate states for financial and power gains. In modern usage in the U.S., the term is sometimes used derisively to refer to a politician who runs for public office in an area where they do not have deep community ties, or have lived only for a short time. In the United Kingdom, the term was adopted to refer informally to those who join a mutual organization, such as a building society, in order to force it to demutualize, that is, to convert into a joint stock company, solely for personal financial gain.[citation needed]

Cutting the rug is a slang term for dancing which originated in 1942.[7] The use of the term "rug" as an informal term for a "toupee" (man's wig) is theater slang from 1940.[7] The term "sweep [something] under the rug" or "sweep [something] under the carpet" figuratively refers to situations where a person or organization is hiding something embarrassing or negative; this use was first recorded in 1953.[4] The figurative expression "pull the rug out from under (someone)", meaning to suddenly deprive of important support, or to upset their plans or make their plans fall through, is first attested to in 1936, in American English.[80]

A related figurative expression used centuries earlier was "cut the grass under (one's) feet", which is attested to in the 1580s.[7] A "rugrat" or "rug-rat" is a slang term for a baby or child, first attested in 1968.[7] The expression "snug as a bug in a rug" means wrapped up tight, warm, and comfortable.[81] To "lie like a rug" means to tell lies shamelessly.[82]

-

A mythical magic carpet

-

The Carpet Seller, a Royal Doulton figurine

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Look up carpet#Usage_notes in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- ^ Cole, Alan Summerly (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 392.

- ^ "Definition of carpet". American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2013 – via Thefreedictionary.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Carpet". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ^ "Carpets, Drinking Water, Laser Eye Surgery, Acoustic Guitars". How It's Made. Season 2. Episode 7. 26 October 2002. Science Channel.

- ^ "Carpet". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 26 September 2025.[dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f "Rug". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ^ "The Illustrated Rug". Nejad. Retrieved 7 May 2025.

- ^ "Middle East Rugs and History". Nazmiyal Collection. Retrieved 7 May 2025.

- ^ "Searching for Oriental carpets along the Silk Routes of Iran". Ramdas Iyer's- Travels around the Globe. Retrieved 7 May 2025.

- ^ Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue of the Great Exhibition. Spicer Brothers. 1851. p. 512.

- ^ "Famed Bhadohi carpet gets GI tag". The Times of India. 9 September 2010. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012.

- ^ "The Science Of Color Enhances Carpet Style". carpet-rug.org. Archived from the original on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ^ Heisterberg-Moutsis, Gudrun; Heinz, Rainer; Wolf, Thomas F.; Harper, Dominic J.; James, David; Mazzur, Richard P.; Kettler, Volker; Soiné, Hansgert (15 September 2001). "Floor Coverings". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. doi:10.1002/14356007.a11_263. ISBN 3-527-30673-0.

- ^ Sengupta, Debolina; Pike, Ralph W. (5 July 2012). Chemicals from Biomass: Ingegrating Bioprocess into Chemical Production. CRC Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-4398-7814-9. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ Chuah, Hoe H. (22 October 2001). "Poly(trimethylene terephthalate)". Encyclopedia of Polymer Science and Technology. doi:10.1002/0471440264.pst292. ISBN 978-0-471-44026-0.

- ^ a b Marcin Latka. "Polish carpets". Archived from the original on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ^ E.J.W. Barber, Prehistoric Textiles: The Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages with Special Reference to the Aegean, 1992, ISBN 0-691-00224-X, p. 171.

- ^ a b Volkmar Gantzhorn, "Oriental Carpets", 1998. ISBN 3-8228-0545-9.

- ^ Ulrich Schurmann (1982). The Pazyryk Its Use and Origin. p. 43.

From all the evidence available I am convinced that the Pazyryk rug was a funeral accessory and most likely a masterpiece of Armenian workmanship

- ^ "The State Hermitage Museum: Collection Highlights". Hermitagemuseum.org. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ Ashkhunj Poghosyan, On origin of Pazyryk rug, Yerevan, 2013 (PDF) pp. 1–21 (in Armenian), pp. 22–37 (in English).

- ^ USSR conference to exchange experiences leading restorers and researchers. The study, preservation and restoration of ethnographic objects. Theses of reports, Riga, 16–21 November 1987. pp. 17–18 (in Russian)

Л.С. Гавриленко, Р.Б. Румянцева, Д.Н. Глебовская, Применение тонкослойной хромотографии и электронной спектроскопии для анализа красителей древних тканей. Исследование, консервация и реставрация этнографических предметов. Тезисы докладов, СССР, Рига, 1987, стр. 17–18.В ковре нити темно-синего и голубого цвета окрашены индиго по карминоносным червецам, нити красного цвета – аналогичными червецами типа араратской кошенили.

- ^ "Ulrich Schurmann, The Pazyryk. Its Use and Origin, Munich, 1982, p.46". Archived from the original on 16 April 2013.

- ^ The Nine Books of the Histories of Herodotus. Thomas Gaisford, Peter Laurent, London, 1846, CLIO I, p. 99.

- ^ "Afghan rugs sell like hot cakes". Afghanembassyjp.com. 2 February 2008. Archived from the original on 21 May 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ^ "Internet Archive Search: creator:"Ulrich Schurmann"". archive.org.

- ^ Ulubabyan, Bagrat A (1975). Խաչենի իշխանությունը, X-XVI դարերում (The Principality of Khachen, From the 10th to 16th Centuries) (in Armenian). Yerevan, Armenian SSR: Armenian Academy of Sciences. p. 267.

- ^ a b c Hakobyan. Medieval Art of Artsakh, p. 84.

- ^ (in Armenian) Kirakos Gandzaketsi. Պատմություն Հայոց (History of Armenia). Yerevan, Armenian SSR: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1961, p. 216, as cited in Hakobyan. Medieval Art of Artsakh, p. 84, note 18.

- ^ Ավանեսյան, Լիլիա (2020). Հայկական գորգերի զարդաձևերի ծագումնաբանությունն ու իմաստաբանությունը. Երևան: Հայաստանի պատմության թանգարան. ISBN 978-9939-9227-3-7.

- ^ Foundation, Encyclopedia Iranica. "Welcome to Encyclopedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org.

- ^ a b "Traditional art of Azerbaijani carpet weaving in the Republic of Azerbaijan". unesco.preslib.az. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- ^ "UNESCO – Traditional art of Azerbaijani carpet weaving in the Republic of Azerbaijan". ich.unesco.org. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- ^ "Baluchi rug". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "Balochi" (PDF). Indiana University Bloomington. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ^ Eiland, Murray L. (2003). "Carpets of the Ming Dynasty?". East and West. 53 (1/4): 179–208. ISSN 0012-8376. JSTOR 29757577.

- ^ "A Case of Social Entrepreneurship". Chillibreeze.com. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ "Handloom weavers shareholders fabric suppliers". The Times of India. 6 May 2008. Archived from the original on 6 June 2012.

- ^ Eiland, Murray (2000). Scholarship and a Controversial Group of Safavid Carpets. Iran 38. The British Institute of Persian Studies.

- ^ Pope, Arthur Upham. A Survey of Persian Art from Prehistoric Times to the Present. Vol. XI, Carpets, Chapter 55. New York: Oxford University Press, 1938-9.

- ^ "Kohan Textile Journal – Asian Carpet Analysis". Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ Khalaj, Mehrnosh (10 February 2010). "Iran's oldest craft left behind". FT.com. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ "The largest hand made carpet in history". JOZAN. 10 May 2004. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ Stone, Peter F. The Oriental Rug Lexicon. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997.

- ^ "The Brukenthal Museum: The extraordinary value of the Anatolian Carpet". Brukenthalmuseum.ro. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ^ "The historical importance of rug and carpet weaving in Anatolia". Turkishculture.org. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ^ "Çatalhöyük.com: Ancient Civilization and Excavation". Catalhoyuk.com. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ^ "Ancient Kilim Evidence Findings in Çatalhöyük". Turkishculture.org. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ^ "The Dominant role of Turkish Women and Girls in Turkish carpet weaving". Turkishculture.org. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ^ Geissler, C. A.; Brun, T. A.; Mirbagheri, I.; Soheli, A.; Naghibi, A.; Hedayat, H. (1981). "The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition: The Role of Women and Girls in traditional rug and carpet weaving" (PDF). The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 34 (12): 2776–2783. doi:10.1093/ajcn/34.12.2776. PMID 7315779. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ^ Aslanapa, Oktay. One Thousand Years of Turkish Carpets. Translated and edited by William A. Edmonds. Istanbul: Eren 1988.

- ^ Living legend Archived 12 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, The president of Turkmenistan Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov book about Turkmen rug

- ^ Gonick, Gloria. Early Carpets and Tapestries on the Eastern Silk Road. ACC Art Books. p. 51.

- ^ Dimand, Maurice Sven and Jean Mailey. Oriental Rugs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1973.

- ^ a b Sherrill, Sarah B. Carpets and Rugs of Europe and America. New York: Abbeville Press, 1996.

- ^ LEPOTA TRAJANJA

- ^ Костова, Антоанета; Димитрова, Милена (2002). "Килимарството в Чипровци — традиции и съвременност". Северозападна България: общности, традиции, идентичност. Регионални проучвания на българския фолклор (in Bulgarian). София: 20–22. ISSN 0861-6558.

- ^ Classical, carpet (25 May 2005). "Classical Carpet" (in Bulgarian). БНР Радио България. Archived from the original on 12 September 2023. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- ^ (french) Jean Coural, Les Gobelins, Nouvelles Editions Latines, 1989, p. 47

- ^ "Axminster carpet – Encyclopædia Britannica". Britannica.com. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ "Axminster Carpets collapses into administration". BBC News. 19 February 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ Morris, Shirley (28 June 2007). Interior Decoration: A Complete Source. Global Media. ISBN 9788189940652. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ Carpets by George Robinson F.T.I., F.S.D.C. published 1966 Chap 7 Wilton Carpets page 72.

- ^ a b c d e f Patton, Randall L. (22 September 2006). Whaples, Robert (ed.). "A History of the U.S. Carpet Industry". EH.Net Encyclopedia. Economic History Association. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ^ a b c Bravender, Robin (12 July 2023). "How Marjorie Taylor Greene's district became Biden's climate poster child". Politico. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ^ Bluestein, Greg (26 January 2013). "Rebound". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ^ a b Patton, Randall L. (6 October 2019) [6 April 2005]. "Chenille Bedspreads". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ^ Pendle, George (7 July 2015). "Dalton, GA: How a Bedspread Fiefdom Became A Carpet Kingdom". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ^ "After Latino boom, Georgia town's population shifts again". CNN. 13 December 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2025.

- ^ Ajoy, Sarkar; Johnson, Ingrid; Cohen, Allen C. (23 February 2023). J.J. Pizzuto's Fabric Science. Bloomsbury. p. 287. ISBN 978-1-5013-6787-8.

- ^ Fleury, Michelle (30 June 2024). "Will Biden's green jobs policy help him win votes?". BBC. Retrieved 3 March 2025.

- ^ Fletcher, Alan J. The Complete Carpet Buying Guide. Portland Oregon: AJ Books 2006.

- ^ "About the GoodWeave label". Goodweave.org. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ^ EPA (7 September 2017). "Durable Goods: Product-Specific Data (Carpets and Rugs)". Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ EPA (14 June 2023). "Identifying Greener Carpet".

- ^ "carpet. - Search Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com.

- ^ a b "carpet" – via The Free Dictionary.

- ^ "Carpet muncher". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- ^ "pull the rug out". TheFreeDictionary.com.

- ^ "snug as a bug in a rug". TheFreeDictionary.com.

- ^ "lie like a rug". TheFreeDictionary.com.

Further reading

[edit]- Walker, Daniel (1997). Flowers Underfoot: Indian Carpets of the Mughal Era. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-8109-6510-0. OCLC 893698548.

Carpet

View on GrokipediaEtymology and Usage

Origins of the Term

The English word "carpet" derives from the late 13th century term for a coarse cloth, evolving by the early 14th century to denote a heavy decorated fabric such as a tablecloth or bedspread, ultimately tracing back to Old French carpite ("heavy decorated cloth") and Medieval Latin carpita ("carpet, rug"). This lineage stems from the Latin verb carpere ("to card, pluck, or tear"), referring to the plucking or carding process used in wool preparation for coarse fabrics, rooted in the Proto-Indo-European krep- ("to pluck, gather, harvest").[2][12] By the 15th century, "carpet" in English had shifted to primarily signify a floor covering, distinguishing it from "rug," which entered the language around the same period from Old Norse rogg or Scandinavian rugga ("coarse fabric or animal skin"), typically implying a smaller, portable piece rather than a fixed or wall-to-wall covering. This etymological and usage divergence reflects evolving domestic practices, where carpets became associated with larger, stationary installations, while rugs retained connotations of mobility and versatility.[2][13] In cross-cultural contexts, terms for carpets reveal diverse linguistic roots tied to function and craftsmanship. The Persian qālī (قالی), denoting a knotted pile carpet, has a debated etymology, with theories including derivation from the ancient city of Qala or as a shortened form of Arabic qaliʿun, possibly meaning "place of folding" in reference to prayer rugs.[14][15] Turkish kilim, referring to a flat-woven, pileless rug, derives from Persian gelim and traces further to Ancient Greek kálumma ("covering" or "veil"), via Aramaic galīmā ("blanket or cloth"), highlighting shared nomadic weaving traditions across Anatolia and Central Asia. Arabic sajjāda (سجادة), often used for prayer rugs, stems from the root s-j-d ("to prostrate" or "bow down"), emphasizing its ritual purpose in Islamic practice.[16] Trade routes, particularly the Silk Road, profoundly influenced carpet terminology by facilitating the exchange of woven goods from Persia, Anatolia, and Central Asia to Europe, introducing phrases like "Oriental carpet" in Western languages by the medieval period to describe imported knotted floor coverings distinct from local cloths. This diffusion not only spread artisanal techniques but also embedded foreign words into European vocabularies, as merchants adopted terms like qālī and kilim to denote exotic, high-value imports.[17][18]Definitions and Distinctions

A carpet is defined as a textile floor covering consisting of an upper layer of pile or flat-woven textile fibers attached to a backing, typically designed for covering substantial floor areas in residential or commercial settings. According to ISO 2424:2007, textile floor coverings like carpets are categorized based on their construction, including pile height, yarn type, and intended use, distinguishing them from non-textile alternatives. The primary distinction between carpets and rugs lies in size and installation: carpets are generally larger, often exceeding 40 square feet (approximately 3.7 square meters), and intended for fixed, wall-to-wall application, while rugs are portable, smaller coverings—typically under 6.5 feet (2 meters) in length—that do not span an entire room.[13] Carpets can be either pile (with cut or looped yarns forming a surface) or flat-woven, and they are secured in place, whereas rugs are often hand-knotted or machine-made for easy relocation.[19] In contrast to mats, which are smaller, utilitarian items made for specific functional purposes like entryway protection or exercise areas and lacking the decorative textile emphasis of carpets, linoleum represents a non-textile floor covering composed of oxidized linseed oil, cork dust, resins, and fillers on a backing, offering a hard, durable surface rather than a soft textile one.[20] Common subtypes of carpets include area carpets, which are room-sized but removable pieces larger than typical rugs (often starting at 4x6 feet or 1.2x1.8 meters); broadloom carpets, supplied in wide rolls (usually 12 feet or 3.7 meters) for seamless wall-to-wall installation; and modular tiles, which are individual squares (typically 18x18 or 24x24 inches, or 46x46 to 61x61 cm) that interlock for customizable, easy-replacement flooring in high-traffic areas.[22][23] These subtypes may incorporate natural or synthetic fibers, but their classification prioritizes construction and application over material specifics.[24] In legal and trade contexts, carpets are classified under standards like EN ISO 10874:2012, which establishes a system for resilient and textile floor coverings based on practical requirements such as wear resistance, impact sound insulation, and slip resistance, assigning use classes from 21 (low domestic) to 33 (heavy commercial).[25] Complementing this, EN 1307:2014 specifically classifies textile floor coverings like pile and woven carpets into domestic (classes 21-23 for moderate to heavy use), commercial (31-33 for moderate to heavy intensity), and luxury classes (LC1-LC5, based on premium durability and appearance retention), determined through tests like the Vetterman drum for appearance change and abrasion resistance.[24] These classifications guide manufacturers, importers, and specifiers in ensuring suitability for intended environments, such as homes versus offices.[26]Materials

Natural Fibers

Wool serves as the primary natural fiber in carpet production, derived from the fleece of sheep through annual shearing.[27] This renewable material is prized for its inherent properties, including exceptional durability that allows it to withstand heavy foot traffic, resilience that enables it to recover from compression, and natural flame resistance stemming from its high nitrogen content and moisture absorption capabilities.[28][29] Sourcing wool involves sustainable grazing practices in pastoral regions, where sheep are raised on regenerative lands to minimize soil erosion and biodiversity loss, though intensive farming can lead to environmental challenges like increased salinity if not managed properly.[30] Following shearing, the raw greasy wool undergoes scouring to remove contaminants such as lanolin, dirt, and sweat, followed by carding to align fibers and spinning into yarns suitable for weaving or tufting. These processes emphasize low-chemical interventions to preserve wool's biodegradability and reduce water usage, making it an eco-friendly choice compared to synthetic alternatives that often involve petroleum-based production and higher energy demands.[31] To enhance performance, wool is frequently blended with other natural fibers like silk for added luster or cotton for improved strength and structure in the foundation.[32] Silk, sourced from silkworm cocoons, imparts a luxurious sheen to high-end pile carpets but remains delicate and prone to wear under direct sunlight or abrasion.[33] Cotton, harvested from the Gossypium plant, is commonly used in flatweave carpets for its breathability and affordability, offering a soft, machine-washable surface that resists allergens.[34] For backing materials, coarser plant-based fibers such as jute from the Corchorus plant or sisal from the Agave sisalana are employed, providing eco-friendly support due to their rapid renewability and low pesticide needs, though they are susceptible to moisture damage and staining in humid environments.[35][36] Historically, wool dominated pre-industrial carpet making in pastoral regions of Central Asia and the Middle East, where nomadic herders had abundant access to sheep fleece, enabling the creation of intricate hand-knotted textiles essential for daily life and trade.[37]Synthetic Fibers