Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

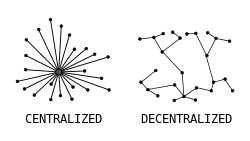

Decentralization

View on Wikipedia

Decentralization or decentralisation is the process by which the activities of an organization, particularly those related to planning and decision-making, are distributed or delegated away from a central, authoritative location or group and given to smaller factions within it.[1]

Concepts of decentralization have been applied to group dynamics and management science in private businesses and organizations, political science, law and public administration, technology, economics and money.

History

[edit]

The word "centralisation" came into use in France in 1794 as the post-Revolution French Directory leadership created a new government structure. The word "décentralisation" came into usage in the 1820s.[2] "Centralization" entered written English in the first third of the 1800s;[3] mentions of decentralization also first appear during those years. In the mid-1800s Tocqueville would write that the French Revolution began with "a push towards decentralization" but became, "in the end, an extension of centralization."[4] In 1863, retired French bureaucrat Maurice Block wrote an article called "Decentralization" for a French journal that reviewed the dynamics of government and bureaucratic centralization and recent French efforts at decentralization of government functions.[5]

Ideas of liberty and decentralization were carried to their logical conclusions during the 19th and 20th centuries by anti-state political activists calling themselves "anarchists", "libertarians", and even decentralists. Tocqueville was an advocate, writing: "Decentralization has, not only an administrative value but also a civic dimension since it increases the opportunities for citizens to take interest in public affairs; it makes them get accustomed to using freedom. And from the accumulation of these local, active, persnickety freedoms, is born the most efficient counterweight against the claims of the central government, even if it were supported by an impersonal, collective will."[6] Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809–1865), influential anarchist theorist[7][8] wrote: "All my economic ideas as developed over twenty-five years can be summed up in the words: agricultural-industrial federation. All my political ideas boil down to a similar formula: political federation or decentralization."[9]

In the early 20th century, America responded to the centralization of economic wealth and political power with a decentralist movement. This movement blamed large-scale industrial production for the decline of middle-class shopkeepers and small manufacturers, and it promoted increased property ownership and a return to small-scale living. The decentralist movement attracted Southern Agrarians like Robert Penn Warren, as well as journalist Herbert Agar.[10] New Left and libertarian individuals who identified with social, economic, and often political decentralism through the ensuing years included Ralph Borsodi, Wendell Berry, Paul Goodman, Carl Oglesby, Karl Hess, Donald Livingston, Kirkpatrick Sale (author of Human Scale),[11] Murray Bookchin,[12] Dorothy Day,[13] Senator Mark O. Hatfield,[14] Mildred J. Loomis[15] and Bill Kauffman.[16]

Leopold Kohr, author of the 1957 book The Breakdown of Nations – known for its statement "Whenever something is wrong, something is too big" – was a major influence on E. F. Schumacher, author of the 1973 bestseller Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered.[17][18] In the next few years a number of best-selling books promoted decentralization.

Daniel Bell's The Coming of Post-Industrial Society[4] discussed the need for decentralization and a "comprehensive overhaul of government structure to find the appropriate size and scope of units", as well as the need to detach functions from current state boundaries, creating regions based on functions like water, transport, education and economics which might have "different 'overlays' on the map."[19][20] Alvin Toffler published Future Shock (1970) and The Third Wave (1980). Discussing the books in a later interview, Toffler said that industrial-style, centralized, top-down bureaucratic planning would be replaced by a more open, democratic, decentralized style which he called "anticipatory democracy".[21] Futurist John Naisbitt's 1982 book "Megatrends" was on The New York Times Best Seller list for more than two years and sold 14 million copies.[22] Naisbitt's book outlines 10 "megatrends", the fifth of which is from centralization to decentralization.[23] In 1996 David Osborne and Ted Gaebler had a best selling book Reinventing Government proposing decentralist public administration theories which became labeled the "New Public Management".[24]

Stephen Cummings wrote that decentralization became a "revolutionary megatrend" in the 1980s.[25] In 1983 Diana Conyers asked if decentralization was the "latest fashion" in development administration.[26] Cornell University's project on Restructuring Local Government states that decentralization refers to the "global trend" of devolving responsibilities to regional or local governments.[27] Robert J. Bennett's Decentralization, Intergovernmental Relations and Markets: Towards a Post-Welfare Agenda describes how after World War II governments pursued a centralized "welfarist" policy of entitlements which now has become a "post-welfare" policy of intergovernmental and market-based decentralization.[27]

In 1983, "Decentralization" was identified as one of the "Ten Key Values" of the Green Movement in the United States.

A 1999 United Nations Development Programme report stated:

"A large number of developing and transitional countries have embarked on some form of decentralization programmes. This trend is coupled with a growing interest in the role of civil society and the private sector as partners to governments in seeking new ways of service delivery ... Decentralization of governance and the strengthening of local governing capacity is in part also a function of broader societal trends. These include, for example, the growing distrust of government generally, the spectacular demise of some of the most centralized regimes in the world (especially the Soviet Union) and the emerging separatist demands that seem to routinely pop up in one or another part of the world. The movement toward local accountability and greater control over one's destiny is, however, not solely the result of the negative attitude towards central government. Rather, these developments, as we have already noted, are principally being driven by a strong desire for greater participation of citizens and private sector organizations in governance."[28]

Overview

[edit]Systems approach

[edit]

Those studying the goals and processes of implementing decentralization often use a systems theory approach, which according to the United Nations Development Programme report applies to the topic of decentralization "a whole systems perspective, including levels, spheres, sectors and functions and seeing the community level as the entry point at which holistic definitions of development goals are from the people themselves and where it is most practical to support them. It involves seeing multi-level frameworks and continuous, synergistic processes of interaction and iteration of cycles as critical for achieving wholeness in a decentralized system and for sustaining its development."[29]

However, it has been seen as part of a systems approach. Norman Johnson of Los Alamos National Laboratory wrote in a 1999 paper: "A decentralized system is where some decisions by the agents are made without centralized control or processing. An important property of agent systems is the degree of connectivity or connectedness between the agents, a measure global flow of information or influence. If each agent is connected (exchange states or influence) to all other agents, then the system is highly connected."[30]

University of California, Irvine's Institute for Software Research's "PACE" project is creating an "architectural style for trust management in decentralized applications." It adopted Rohit Khare's definition of decentralization: "A decentralized system is one which requires multiple parties to make their own independent decisions" and applies it to Peer-to-peer software creation, writing:

In such a decentralized system, there is no single centralized authority that makes decisions on behalf of all the parties. Instead each party, also called a peer, makes local autonomous decisions towards its individual goals which may possibly conflict with those of other peers. Peers directly interact with each other and share information or provide service to other peers. An open decentralized system is one in which the entry of peers is not regulated. Any peer can enter or leave the system at any time ...[31]

Goals

[edit]Decentralization in any area is a response to the problems of centralized systems. Decentralization in government, the topic most studied, has been seen as a solution to problems like economic decline, government inability to fund services and their general decline in performance of overloaded services, the demands of minorities for a greater say in local governance, the general weakening legitimacy of the public sector and global and international pressure on countries with inefficient, undemocratic, overly centralized systems.[32] The following four goals or objectives are frequently stated in various analyses of decentralization.

- Participation

In decentralization, the principle of subsidiarity is often invoked. It holds that the lowest or least centralized authority that is capable of addressing an issue effectively should do so. According to one definition: "Decentralization, or decentralizing governance, refers to the restructuring or reorganization of authority so that there is a system of co-responsibility between institutions of governance at the central, regional and local levels according to the principle of subsidiarity, thus increasing the overall quality and effectiveness of the system of governance while increasing the authority and capacities of sub-national levels."[33]

Decentralization is often linked to concepts of participation in decision-making, democracy, equality and liberty from a higher authority.[34][35] Decentralization enhances the democratic voice.[27] Theorists believe that local representative authorities with actual discretionary powers are the basis of decentralization that can lead to local efficiency, equity and development."[36] Columbia University's Earth Institute identified one of three major trends relating to decentralization: "increased involvement of local jurisdictions and civil society in the management of their affairs, with new forms of participation, consultation, and partnerships."[6]

Decentralization has been described as a "counterpoint to globalization [which] removes decisions from the local and national stage to the global sphere of multi-national or non-national interests. Decentralization brings decision-making back to the sub-national levels". Decentralization strategies must account for the interrelations of global, regional, national, sub-national, and local levels.[37]

- Diversity

Norman L. Johnson writes that diversity plays an important role in decentralized systems like ecosystems, social groups, large organizations, political systems. "Diversity is defined to be unique properties of entities, agents, or individuals that are not shared by the larger group, population, structure. Decentralized is defined as a property of a system where the agents have some ability to operate "locally." Both decentralization and diversity are necessary attributes to achieve the self-organizing properties of interest."[30]

Advocates of political decentralization hold that greater participation by better informed diverse interests in society will lead to more relevant decisions than those made only by authorities on the national level.[38] Decentralization has been described as a response to demands for diversity.[6][39]

- Efficiency

In business, decentralization leads to a management by results philosophy which focuses on definite objectives to be achieved by unit results.[40] Decentralization of government programs is said to increase efficiency – and effectiveness – due to reduction of congestion in communications, quicker reaction to unanticipated problems, improved ability to deliver services, improved information about local conditions, and more support from beneficiaries of programs.[41]

Firms may prefer decentralization because it ensures efficiency by making sure that managers closest to the local information make decisions and in a more timely fashion; that their taking responsibility frees upper management for long term strategics rather than day-to-day decision-making; that managers have hands on training to prepare them to move up the management hierarchy; that managers are motivated by having the freedom to exercise their own initiative and creativity; that managers and divisions are encouraged to prove that they are profitable, instead of allowing their failures to be masked by the overall profitability of the company.[42]

The same principles can be applied to the government. Decentralization promises to enhance efficiency through both inter-governmental competitions with market features and fiscal discipline which assigns tax and expenditure authority to the lowest level of government possible. It works best where members of the subnational government have strong traditions of democracy, accountability, and professionalism.[27]

- Conflict resolution

Economic and/or political decentralization can help prevent or reduce conflict because they reduce actual or perceived inequities between various regions or between a region and the central government.[43] Dawn Brancati finds that political decentralization reduces intrastate conflict unless politicians create political parties that mobilize minority and even extremist groups to demand more resources and power within national governments. However, the likelihood this will be done depends on factors like how democratic transitions happen and features like a regional party's proportion of legislative seats, a country's number of regional legislatures, elector procedures, and the order in which national and regional elections occur. Brancati holds that decentralization can promote peace if it encourages statewide parties to incorporate regional demands and limit the power of regional parties.[44]

Processes

[edit]- Initiation

The processes by which entities move from a more to a less centralized state vary. They can be initiated from the centers of authority ("top-down") or from individuals, localities or regions ("bottom-up"),[45] or from a "mutually desired" combination of authorities and localities working together.[46] Bottom-up decentralization usually stresses political values like local responsiveness and increased participation and tends to increase political stability. Top-down decentralization may be motivated by the desire to "shift deficits downwards" and find more resources to pay for services or pay off government debt.[45] Some hold that decentralization should not be imposed, but done in a respectful manner.[47]

- Appropriate size

Gauging the appropriate size or scale of decentralized units has been studied in relation to the size of sub-units of hospitals[48] and schools,[32] road networks,[49] administrative units in business[50] and public administration, and especially town and city governmental areas and decision-making bodies.[51][52]

In creating planned communities ("new towns"), it is important to determine the appropriate population and geographical size. While in earlier years small towns were considered appropriate, by the 1960s, 60,000 inhabitants was considered the size necessary to support a diversified job market and an adequate shopping center and array of services and entertainment. Appropriate size of governmental units for revenue raising also is a consideration.[53]

Even in bioregionalism, which seeks to reorder many functions and even the boundaries of governments according to physical and environmental features, including watershed boundaries and soil and terrain characteristics, appropriate size must be considered. The unit may be larger than many decentralist-bioregionalists prefer.[54]

- Inadvertent or silent

Decentralization ideally happens as a careful, rational, and orderly process, but it often takes place during times of economic and political crisis, the fall of a regime and the resultant power struggles. Even when it happens slowly, there is a need for experimentation, testing, adjusting, and replicating successful experiments in other contexts. There is no one blueprint for decentralization since it depends on the initial state of a country and the power and views of political interests and whether they support or oppose decentralization.[55]

Decentralization usually is a conscious process based on explicit policies. However, it may occur as "silent decentralization" in the absence of reforms as changes in networks, policy emphasize and resource availability lead inevitably to a more decentralized system.[56]

- Asymmetry

Decentralization may be uneven and "asymmetric" given any one country's population, political, ethnic and other forms of diversity. In many countries, political, economic and administrative responsibilities may be decentralized to the larger urban areas, while rural areas are administered by the central government. Decentralization of responsibilities to provinces may be limited only to those provinces or states which want or are capable of handling responsibility. Some privatization may be more appropriate to an urban than a rural area; some types of privatization may be more appropriate for some states and provinces but not others.[57]

Determinants

[edit]The academic literature frequently mentions the following factors as determinants of decentralization:[58]

- "The number of major ethnic groups"

- "The degree of territorial concentration of those groups"

- "The existence of ethnic networks and communities across the border of the state"

- "The country's dependence on natural resources and the degree to which those resources are concentrated in the region's territory"

- "The country's per capita income relative to that in other regions"

- The presence of self-determination movements

In government policy

[edit]Historians have described the history of governments and empires in terms of centralization and decentralization. In his 1910 The History of Nations Henry Cabot Lodge wrote that Persian king Darius I (550–486 BC) was a master of organization and "for the first time in history centralization becomes a political fact." He also noted that this contrasted with the decentralization of Ancient Greece.[59] Since the 1980s a number of scholars have written about cycles of centralization and decentralization. Stephen K. Sanderson wrote that over the last 4000 years chiefdoms and actual states have gone through sequences of centralization and decentralization of economic, political and social power.[60] Yildiz Atasoy writes this process has been going on "since the Stone Age" through not just chiefdoms and states, but empires and today's "hegemonic core states".[61] Christopher K. Chase-Dunn and Thomas D. Hall review other works that detail these cycles, including works which analyze the concept of core elites which compete with state accumulation of wealth and how their "intra-ruling-class competition accounts for the rise and fall of states" and their phases of centralization and decentralization.[62]

Rising government expenditures, poor economic performance and the rise of free market-influenced ideas have convinced governments to decentralize their operations, to induce competition within their services, to contract out to private firms operating in the market, and to privatize some functions and services entirely.[63]

Government decentralization has both political and administrative aspects. Its decentralization may be territorial, moving power from a central city to other localities, and it may be functional, moving decision-making from the top administrator of any branch of government to lower level officials, or divesting of the function entirely through privatization.[64] It has been called the "new public management" which has been described as decentralization, management by objectives, contracting out, competition within government and consumer orientation.[65]

Political

[edit]Political decentralization signifies a reduction in the authority of national governments over policy-making. This process is accomplished by the institution of reforms that either delegate a certain degree of meaningful decision-making autonomy to sub-national tiers of government,[66] or grant citizens the right to elect lower-level officials, like local or regional representatives.[67] Depending on the country, this may require constitutional or statutory reforms, the development of new political parties, increased power for legislatures, the creation of local political units, and encouragement of advocacy groups.[38]

A national government may decide to decentralize its authority and responsibilities for a variety of reasons. Decentralization reforms may occur for administrative reasons, when government officials decide that certain responsibilities and decisions would be handled best at the regional or local level. In democracies, traditionally conservative parties include political decentralization as a directive in their platforms because rightist parties tend to advocate for a decrease in the role of central government. There is also strong evidence to support the idea that government stability increases the probability of political decentralization, since instability brought on by gridlock between opposing parties in legislatures often impedes a government's overall ability to enact sweeping reforms.[66]

The rise of regional ethnic parties in the national politics of parliamentary democracies is also heavily associated with the implementation of decentralization reforms.[66] Ethnic parties may endeavor to transfer more autonomy to their respective regions, and as a partisan strategy, ruling parties within the central government may cooperate by establishing regional assemblies in order to curb the rise of ethnic parties in national elections.[66] This phenomenon famously occurred in 1999, when the United Kingdom's Labour Party appealed to Scottish constituents by creating a semi-autonomous Scottish Parliament in order to neutralize the threat from the increasingly popular Scottish National Party at the national level.[66]

In addition to increasing the administrative efficacy of government and endowing citizens with more power, there are many projected advantages to political decentralization. Individuals who take advantage of their right to elect local and regional authorities have been shown to have more positive attitudes toward politics,[68] and increased opportunities for civic decision-making through participatory democracy mechanisms like public consultations and participatory budgeting are believed to help legitimize government institutions in the eyes of marginalized groups.[69] Moreover, political decentralization is perceived as a valid means of protecting marginalized communities at a local level from the detrimental aspects of development and globalization driven by the state, like the degradation of local customs, codes, and beliefs.[70] In his 2013 book, Democracy and Political Ignorance, George Mason University law professor Ilya Somin argued that political decentralization in a federal democracy confronts the widespread issue of political ignorance by allowing citizens to engage in foot voting, or moving to other jurisdictions with more favorable laws.[71] He cites the mass migration of over one million southern-born African Americans to the North or the West to evade discriminatory Jim Crow laws in the late 19th century and early 20th century.[71]

The European Union follows the principle of subsidiarity, which holds that decision-making should be made by the most local competent authority. The EU should decide only on enumerated issues that a local or member state authority cannot address themselves. Furthermore, enforcement is exclusively the domain of member states. In Finland, the Centre Party explicitly supports decentralization. For example, government departments have been moved from the capital Helsinki to the provinces. The centre supports substantial subsidies that limit potential economic and political centralization to Helsinki.[72]

Political decentralization does not come without its drawbacks. A study by Fan concludes that there is an increase in corruption and rent-seeking when there are more vertical tiers in the government, as well as when there are higher levels of subnational government employment.[73] Other studies warn of high-level politicians that may intentionally deprive regional and local authorities of power and resources when conflicts arise.[70] In order to combat these negative forces, experts believe that political decentralization should be supplemented with other conflict management mechanisms like power-sharing, particularly in regions with ethnic tensions.[69]

Administrative

[edit]Four major forms of administrative decentralization have been described.[74][75]

- Deconcentration, the weakest form of decentralization, shifts responsibility for decision-making, finance and implementation of certain public functions[76] from officials of central governments to those in existing districts or, if necessary, new ones under direct control of the central government.

- Delegation passes down responsibility for decision-making, finance and implementation. It involves the creation of public-private enterprises or corporations, or of "authorities", special projects or service districts. All of them will have a great deal of decision-making discretion and they may be exempt from civil service requirements and may be permitted to charge users for services.

- Devolution transfers responsibility for decision-making, finance and implementation of certain public functions to the sub-national level, such as a regional, local, or state government.

- Divestment, also called privatization, may mean merely contracting out services to private companies. Or it may mean relinquishing totally all responsibility for decision-making, finance and implementation of certain public functions. Facilities will be sold off, workers transferred or fired and private companies or non-for-profit organizations allowed to provide the services.[77] Many of these functions originally were done by private individuals, companies, or associations and later taken over by the government, either directly, or by regulating out of business entities which competed with newly created government programs.[78]

Fiscal

[edit]Fiscal decentralization means decentralizing revenue raising and/or expenditure of moneys to a lower level of government while maintaining financial responsibility.[74] While this process usually is called fiscal federalism, it may be relevant to unitary, federal, or confederal governments. Fiscal federalism also concerns the "vertical imbalances" where the central government gives too much or too little money to the lower levels. It actually can be a way of increasing central government control of lower levels of government, if it is not linked to other kinds of responsibilities and authority.[79][80][81]

Fiscal decentralization can be achieved through user fees, user participation through monetary or labor contributions, expansion of local property or sales taxes, intergovernmental transfers of central government tax monies to local governments through transfer payments or grants, and authorization of municipal borrowing with national government loan guarantees. Transfers of money may be given conditionally with instructions or unconditionally without them.[74][82]

Market

[edit]Market decentralization can be done through privatization of public owned functions and businesses, as described briefly above. But it also is done through deregulation, the abolition of restrictions on businesses competing with government services, for example, postal services, schools, garbage collection. Even as private companies and corporations have worked to have such services contracted out to or privatized by them, others have worked to have these turned over to non-profit organizations or associations.[74]

From the 1970s to the 1990s, there was deregulation of some industries, like banking, trucking, airlines and telecommunications, which resulted generally in more competition and lower prices.[83] According to the Cato Institute, an American libertarian think-tank, in some cases deregulation in some aspects of an industry were offset by increased regulation in other aspects, the electricity industry being a prime example.[84] For example, in banking, Cato Institute believes some deregulation allowed banks to compete across state lines, increasing consumer choice, while an actual increase in regulators and regulations forced banks to make loans to individuals incapable of repaying them, leading eventually to the 2008 financial crisis.[85]

One example of economic decentralization, which is based on a libertarian socialist model, is decentralized economic planning. Decentralized planning is a type of economic system in which decision-making is distributed amongst various economic agents or localized within production agents. An example of this method in practice is in Kerala, India which experimented in 1996 with the People's Plan campaign.[86]

Emmanuelle Auriol and Michel Benaim write about the "comparative benefits" of decentralization versus government regulation in the setting of standards. They find that while there may be a need for public regulation if public safety is at stake, private creation of standards usually is better because "regulators or 'experts' might misrepresent consumers' tastes and needs." As long as companies are averse to incompatible standards, standards will be created that satisfy needs of a modern economy.[87]

Environmental

[edit]Central governments themselves may own large tracts of land and control the forest, water, mineral, wildlife and other resources they contain. They may manage them through government operations or leasing them to private businesses; or they may neglect them to be exploited by individuals or groups who defy non-enforced laws against exploitation. It also may control most private land through land-use, zoning, environmental and other regulations.[88] Selling off or leasing lands can be profitable for governments willing to relinquish control, but such programs can face public scrutiny because of fear of a loss of heritage or of environmental damage. Devolution of control to regional or local governments has been found to be an effective way of dealing with these concerns.[89] Such decentralization has happened in India[90] and other developing nations.[91]

In economic ideology

[edit]Libertarian socialism

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Libertarianism |

|---|

|

Libertarian socialism is a political philosophy that promotes a non-hierarchical, non-bureaucratic society without private ownership in the means of production. Libertarian socialists believe in converting present-day private productive property into common or public goods.[93] It promotes free association in place of government and non-coercive forms for social organization, and it opposes the various social relations of capitalism, such as wage slavery.[94] The term libertarian socialism is used by some socialists to differentiate their philosophy from state socialism,[95][96] and by some as a synonym for left anarchism.[97][98][99]

Accordingly, libertarian socialists believe that "the exercise of power in any institutionalized form – whether economic, political, religious, or sexual – brutalizes both the wielder of power and the one over whom it is exercised".[100] Libertarian socialists generally place their hopes in decentralized means of direct democracy such as libertarian municipalism, citizens' assemblies, or workers' councils.[101] Libertarian socialists are strongly critical of coercive institutions, which often leads them to reject the legitimacy of the state in favor of anarchism.[102] Adherents propose achieving this through decentralization of political and economic power, usually involving the socialization of most large-scale private property and enterprise (while retaining respect for personal property). Libertarian socialism tends to deny the legitimacy of most forms of economically significant private property, viewing capitalist property relations as forms of domination that are antagonistic to individual freedom.[103]

Free market

[edit]Free market ideas popular in the 19th century such as those of Adam Smith returned to prominence in the 1970s and 1980s. Austrian School economist Friedrich von Hayek argued that free markets themselves are decentralized systems where outcomes are produced without explicit agreement or coordination by individuals who use prices as their guide.[104] Eleanor Doyle writes that "[e]conomic decision-making in free markets is decentralized across all the individuals dispersed in each market and is synchronized or coordinated by the price system," and holds that an individual right to property is part of this decentralized system.[105] Criticizing central government control, Hayek wrote in The Road to Serfdom:

There would be no difficulty about efficient control or planning were conditions so simple that a single person or board could effectively survey all the relevant facts. It is only as the factors which have to be taken into account become so numerous that it is impossible to gain a synoptic view of them that decentralization becomes imperative.[106]

According to Bruce M. Owen, this does not mean that all firms themselves have to be equally decentralized. He writes: "markets allocate resources through arms-length transactions among decentralized actors. Much of the time, markets work very efficiently, but there is a variety of conditions under which firms do better. Hence, goods and services are produced and sold by firms with various degrees of horizontal and vertical integration." Additionally, he writes that the "economic incentive to expand horizontally or vertically is usually, but not always, compatible with the social interest in maximizing long-run consumer welfare."[107]

It is often claimed that free markets and private property generate centralized monopolies and other ills; free market advocates counter with the argument that government is the source of monopoly.[108] Historian Gabriel Kolko in his book The Triumph of Conservatism argued that in the first decade of the 20th century businesses were highly decentralized and competitive, with new businesses constantly entering existing industries. In his view, there was no trend towards concentration and monopolization. While there were a wave of mergers of companies trying to corner markets, they found there was too much competition to do so. According to Kolko, this was also true in banking and finance, which saw decentralization as leading to instability as state and local banks competed with the big New York City firms. He argues that, as a result, the largest firms turned to the power of the state and worked with leaders like United States Presidents Theodore Roosevelt, William H. Taft and Woodrow Wilson to pass as "progressive reforms" centralizing laws like The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 that gave control of the monetary system to the wealthiest bankers; the formation of monopoly "public utilities" that made competition with those monopolies illegal; federal inspection of meat packers biased against small companies; extending Interstate Commerce Commission to regulating telephone companies and keeping rates high to benefit AT&T; and using the Sherman Antitrust Act against companies which might combine to threaten larger or monopoly companies.[109][110]

Author and activist Jane Jacobs's influential 1961 book The Death and Life of American Cities criticized large-scale redevelopment projects which were part of government-planned decentralization of population and businesses to suburbs. She believed it destroyed cities' economies and impoverished remaining residents.[111] Her 1980 book The Question of Separatism: Quebec and the Struggle over Sovereignty supported secession of Quebec from Canada.[112] Her 1984 book Cities and the Wealth of Nations proposed a solution to the problems faced by cities whose economies were being ruined by centralized national governments: decentralization through the "multiplication of sovereignties", meaning an acceptance of the right of cities to secede from the larger nation states that were greatly limiting their ability to produce wealth.[113][114]

In the organizational structure of a firm

[edit]In response to incentive and information conflicts, a firm can either centralize their organizational structure by concentrating decision-making to upper management, or decentralize their organizational structure by delegating authority throughout the organization.[115] The delegation of authority comes with a basic trade-off: while it can increase efficiency and information flow, the central authority consequentially suffers a loss of control.[116] However, through creating an environment of trust and allocating authority formally in the firm, coupled with a stronger rule of law in the geographical location of the firm, the negative consequences of the trade-off can be minimized.[117]

In having a decentralized organizational structure, a firm can remain agile to external shocks and competing trends. Decision-making in a centralized organization can face information flow inefficiencies and barriers to effective communication which decreases the speed and accuracy in which decisions are made. A decentralized firm is said to hold greater flexibility given the efficiency in which it can analyze information and implement relevant outcomes.[118] Additionally, having decision-making power spread across different areas allows for local knowledge to inform decisions, increasing their relevancy and implementational effectiveness.[119] In the process of developing new products or services, the decentralization enable the firm gain advantages of closely meet particular division's needs.[120]

Decentralization also impacts human resource management. The high level of individual agency that workers experience within a decentralized firm can create job enrichment. Studies have shown this enhances the development of new ideas and innovations given the sense of involvement that comes from responsibility.[121] The impacts of decentralization on innovation are furthered by the ease of information flow that comes from this organizational structure. With increased knowledge sharing, workers are more able to use relevant information to inform decision-making.[122] These benefits are enhanced in firms with skill-intensive environments. Skilled workers are more able to analyze information, they pose less risk of information duplication given increased communication abilities, and the productivity cost of multi-tasking is lower. These outcomes of decentralizion make it a particularly effective organizational structure for entrepreneurial and competitive firm environments, such as start-up companies. The flexibility, efficiency of information flow and higher worker autonomy complement the rapid growth and innovation seen in successful start up companies.[123]

In technology and the Internet

[edit]

Technological decentralization can be defined as a shift from concentrated to distributed modes of production and consumption of goods and services.[124] Generally, such shifts are accompanied by transformations in technology and different technologies are applied for either system. Technology includes tools, materials, skills, techniques and processes by which goals are accomplished in the public and private spheres. Concepts of decentralization of technology are used throughout all types of technology, including especially information technology and appropriate technology.

Technologies often mentioned as best implemented in a decentralized manner, include: water purification, delivery and waste water disposal,[125][126] agricultural technology[127] and energy technology.[128][129] Advances in technology may create opportunities for decentralized and privatized replacements for what had traditionally been public services or utilities, such as power, water, mail, telecommunications, consumer product safety, banking, medical licensure, parking meters, and auto emissions.[130] However, in terms of technology, a clear distinction between fully centralized or decentralized technical solutions is often not possible and therefore finding an optimal degree of centralization difficult from an infrastructure planning perspective.[131]

Information technology

[edit]Information technology encompasses computers and computer networks, as well as information distribution technologies such as television and telephones. The whole computer industry of computer hardware, software, electronics, Internet, telecommunications equipment, e-commerce and computer services are included.[132]

Executives and managers face a constant tension between centralizing and decentralizing information technology for their organizations. They must find the right balance of centralizing which lowers costs and allows more control by upper management, and decentralizing which allows sub-units and users more control. This will depend on analysis of the specific situation. Decentralization is particularly applicable to business or management units which have a high level of independence, complicated products and customers, and technology less relevant to other units.[133]

Information technology applied to government communications with citizens, often called e-Government, is supposed to support decentralization and democratization. Various forms have been instituted in most nations worldwide.[134]

The Internet is an example of an extremely decentralized network, having no owners at all (although some have argued that this is less the case in recent years[135]). "No one is in charge of internet, and everyone is." As long as they follow a certain minimal number of rules, anyone can be a service provider or a user. Voluntary boards establish protocols, but cannot stop anyone from developing new ones.[136] Other examples of open source or decentralized movements are Wikis which allow users to add, modify, or delete content via the internet.[137] Wikipedia has been described as decentralized (although it is a centralized web site, with a single entity operating the servers).[138] Smartphones have been described as being an important part of the decentralizing effects of smaller and cheaper computers worldwide.[139]

Decentralization continues throughout the industry, for example as the decentralized architecture of wireless routers installed in homes and offices supplement and even replace phone companies' relatively centralized long-range cell towers.[140]

Inspired by system and cybernetics theorists like Norbert Wiener, Marshall McLuhan and Buckminster Fuller, in the 1960s Stewart Brand started the Whole Earth Catalog and later computer networking efforts to bring Silicon Valley computer technologists and entrepreneurs together with countercultural ideas. This resulted in ideas like personal computing, virtual communities and the vision of an "electronic frontier" which would be a more decentralized, egalitarian and free-market libertarian society. Related ideas coming out of Silicon Valley included the free software and creative commons movements which produced visions of a "networked information economy".[141]

Because human interactions in cyberspace transcend physical geography, there is a necessity for new theories in legal and other rule-making systems to deal with decentralized decision-making processes in such systems. For example, what rules should apply to conduct on the global digital network and who should set them? The laws of which nations govern issues of Internet transactions (like seller disclosure requirements or definitions of "fraud"), copyright and trademark?[142]

Decentralized computing

[edit]This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Decentralized computing is the allocation of resources, both hardware and software, to each individual workstation, or office location. In contrast, centralized computing exists when the majority of functions are carried out or obtained from a remote centralized location. Decentralized computing is a trend in modern-day business environments. This is the opposite of centralized computing, which was prevalent during the early days of computers. A decentralized computer system has many benefits over a conventional centralized network.[143] Desktop computers have advanced so rapidly, that their potential performance far exceeds the requirements of most business applications. This results in most desktop computers remaining idle (in relation to their full potential). A decentralized system can use the potential of these systems to maximize efficiency. However, it is debatable whether these networks increase overall effectiveness.

All computers have to be updated individually with new software, unlike a centralized computer system. Decentralized systems still enable file sharing and all computers can share peripherals such as printers and scanners as well as modems, allowing all the computers in the network to connect to the internet.

A collection of decentralized computers systems are components of a larger computer network, held together by local stations of equal importance and capability. These systems are capable of running independently of each other.Centralization and re-decentralization of the Internet

[edit]The New Yorker reports that although the Internet was originally decentralized, by 2013 it had become less so: "a staggering percentage of communications flow through a small set of corporations – and thus, under the profound influence of those companies and other institutions [...] One solution, espoused by some programmers, is to make the Internet more like it used to be – less centralized and more distributed."[135]

Blockchain technology

[edit]In blockchain, decentralization refers to the transfer of control and decision-making from a centralized entity (individual, organization, or group thereof) to a distributed network. Decentralized networks strive to reduce the level of trust that participants must place in one another, and deter their ability to exert authority or control over one another in ways that degrade the functionality of the network.[144]

Decentralized protocols, applications, and ledgers (used in Web3[145][146]) could be more difficult for governments to regulate, similar to difficulties regulating BitTorrent (which is not a blockchain technology).[147]

Criticism

[edit]Factors hindering decentralization include weak local administrative or technical capacity, which may result in inefficient or ineffective services; inadequate financial resources available to perform new local responsibilities, especially in the start-up phase when they are most needed; or inequitable distribution of resources.[148] Decentralization can make national policy coordination too complex; it may allow local elites to capture functions; local cooperation may be undermined by any distrust between private and public sectors; decentralization may result in higher enforcement costs and conflict for resources if there is no higher level of authority.[149] Additionally, decentralization may not be as efficient for standardized, routine, network-based services, as opposed to those that need more complicated inputs. If there is a loss of economies of scale in procurement of labor or resources, the expense of decentralization can rise, even as central governments lose control over financial resources.[74]

It has been noted that while decentralization may increase "productive efficiency" it may undermine "allocative efficiency" by making redistribution of wealth more difficult. Decentralization will cause greater disparities between rich and poor regions, especially during times of crisis when the national government may not be able to help regions needing it.[150]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Definition of decentralisation. Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ Vivien A. Schmidt, Democratizing France: The Political and Administrative History of Decentralization, Cambridge University Press, 2007, p. 22 Archived 2016-05-05 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0521036054

- ^ Barbara Levick, Claudius, Psychology Press, 2012, p. 81 Archived 2016-06-02 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0415166195

- ^ a b Vivien A. Schmidt, Democratizing France: The Political and Administrative History of Decentralization, p. 10 Archived 2016-05-20 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Robert Leroux, French Liberalism in the 19th Century: An Anthology, Chapter 6: Maurice Block on "Decentralization", Routledge, 2012, p. 255 Archived 2016-05-29 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-1136313011

- ^ a b c A History of Decentralization Archived 2013-05-11 at the Wayback Machine, Earth Institute of Columbia University website, accessed February 4, 2013.

- ^ George Edward Rines, ed. (1918). Encyclopedia Americana. New York: Encyclopedia Americana Corp. p. 624. OCLC 7308909.

- ^ Hamilton, Peter (1995). Émile Durkheim. New York: Routledge. p. 79. ISBN 978-0415110471.

- ^ "Du principe Fédératif" ("Principle of Federation"), 1863.

- ^ Craig R. Prentiss, Debating God's Economy: Social Justice in America on the Eve of Vatican II, Penn State Press, 2008, p. 43 Archived 2016-05-03 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0271033419

- ^ Kauffman, Bill (2008). "Decentralism". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, Cato Institute. pp. 111–113. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n71. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024. Archived from the original on 1 May 2016.

- ^ David De Leon, Leaders from the 1960s: A Biographical Sourcebook of American Activism, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1994, p. 297 Archived 2015-11-05 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0313274145

- ^ Nancy L. Roberts, Dorothy Day and the Catholic worker, Volume 84, Issue 1 of National security essay series, State University of New York Press, 1984, p. 11 Archived 2016-05-17 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0873959391

- ^ Jesse Walker, Mark O. Hatfield, RIP Archived 2013-06-03 at the Wayback Machine, Reason, August 8, 2011.

- ^ Mildred J. Loomis, Decentralism: Where It Came From – Where Is It Going?, Black Rose Books, 2005, ISBN 978-1551642499

- ^ Bill Kauffman, Bye Bye, Miss American Empire: Neighborhood Patriots, Backcountry rebels, Chelsea Green Publishing, 2010, p. xxxi Archived 2016-05-05 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-1933392806

- ^ Dr. Leopold Kohr, 84; Backed Smaller States Archived 2017-01-18 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times obituary, February 28, 1994.

- ^ John Fullerton, The Relevance of E. F. Schumacher in the 21st Century Archived 2013-04-05 at the Wayback Machine, New Economics Institute, accessed February 7, 2013.

- ^ W. Patrick McCray, The Visioneers: How a Group of Elite Scientists Pursued Space Colonies, Nanotechnologies, and a Limitless Future, Princeton University Press, 2012, p. 70 Archived 2016-05-14 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0691139838

- ^ Daniel Bell, The Coming Of Post-industrial Society, Basic Books version, 2008, p. 320–21, ISBN 978-0786724734

- ^ Alvin Toffler, Previews & Premises: An Interview with the Author of Future Shock and The Third Wave, Black Rose books, 1987, p. 50 Archived 2016-05-08 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0920057377

- ^ John Naisbitt biography Archived 2013-09-16 at the Wayback Machine at personal website, accessed February 10, 2013.

- ^ Sam Inkinen, Mediapolis: Aspects of Texts, Hypertexts and Multimedial Communication, Volume 25 of Research in Text Theory, Walter de Gruyter, 1999, p. 272 Archived 2016-04-28 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-3110807059

- ^ Kamensky, John M. (May–June 1996). "Role of the "Reinventing Government" Movement in Federal Management Reform". Public Administration Review. 56 (3): 247–55. doi:10.2307/976448. JSTOR 976448.

- ^ Stephen Cummings, ReCreating Strategy, SAGE, 2002, p. 157 Archived 2016-05-22 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0857026514

- ^ Diana Conyers, "Decentralization: The latest fashion in development administration?" Archived 2014-05-22 at the Wayback Machine, Public Administration and Development, Volume 3, Issue 2, pp. 97–109, April/June 1983, via Wiley Online Library, accessed February 4, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Decentralization Archived 2012-10-26 at the Wayback Machine, article at the "Restructuring local government project Archived 2013-01-17 at the Wayback Machine" of Dr. Mildred Warner, Cornell University, accessed February 4, 2013.

- ^ "Decentralization: A Sampling of Definitions" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. October 1999. pp. 11–12.

- ^ "Decentralization: A Sampling of Definitions", 1999, p. 13.

- ^ a b Johnson, Norman L. (1999). Diversity in Decentralized Systems: Enabling Self-Organizing Solutions. Theoretical Division, Los Alamos National Laboratory, for University of California Los Angeles 1999 conference "Decentralization Two". CiteSeerX 10.1.1.80.1110.

- ^ PACE Project "What is Decentralization?" page Archived 2013-03-29 at the Wayback Machine, University of California, Irvine's Institute for Software Research, Last Updated – May 10, 2006.

- ^ a b Holger Daun, School Decentralization in the Context of Globalizing Governance: International Comparison of Grassroots Responses, Springer, 2007, pp. 28–29 Archived 2016-06-17 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-1402047008

- ^ "Decentralization: A Sampling of Definitions", 1999, pp. 2, 16, 26.

- ^ Subhabrata Dutta, Democratic decentralization and grassroot leadership in India Archived 2015-03-19 at the Wayback Machine, Mittal Publications, 2009, pp. 5–8, ISBN 978-8183242738

- ^ Robert Charles Vipond, Liberty & Community: Canadian Federalism and the Failure of the Constitution Archived 2016-06-24 at the Wayback Machine, SUNY Press, 1991, p. 145, ISBN 978-0791404669

- ^ Ribot, J (2003). "Democratic Decentralisation of Natural Resources: Institutional Choice and Discretionary Power Transfers in Sub-Saharan Africa". Public Administration and Development. 23: 53–65. doi:10.1002/pad.259. S2CID 55187335.

- ^ "Decentralization: A Sampling of Definitions", 1999, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Political Decentralization Archived 2013-04-09 at the Wayback Machine, Decentralization and Subnational Economies project, World Bank website, accessed February 9, 2013.

- ^ Therese A McCarty, Demographic diversity and the size of the public sector Archived 2014-05-22 at the Wayback Machine, Kyklos, 1993, via Wiley Online Library. Quote: "if demographic diversity promotes greater decentralization, the size of the public sector is not affected 10 consequently."

- ^ "Decentralization: A Sampling of Definitions", 1999, p. 11.

- ^ Jerry M. Silverman, Public Sector Decentralization: Economic Policy and Sector Investment Programs, Volume 188, World Bank Publications, 1992, p. 4 Archived 2016-05-28 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0821322796

- ^ Don R. Hansen, Maryanne M. Mowen, Liming Guan, Cost Management: Accounting & Control, Cengage Learning, 2009, p. 338 Archived 2016-05-13 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0324559675

- ^ David R. Cameron, Gustav Ranis, Annalisa Zinn, Globalization and Self-Determination: Is the Nation-State Under Siege?, Taylor & Francis, 2006, p. 203 Archived 2016-05-03 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0203086636

- ^ Dawn Brancati, Peace by Design:Managing Intrastate Conflict through Decentralization, Oxford University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0191615221

- ^ a b Ariunaa Lkhagvadorj, Fiscal federalism and decentralization in Mongolia, University of Potsdam, Germany, 2010, p. 23 Archived 2016-06-10 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-3869560533

- ^ Karin E. Kemper, Ariel Dinar, Integrated River Basin Management Through Decentralization, Springer, 2007, p. 36 Archived 2016-04-25 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-3540283553.

- ^ "Decentralization: A Sampling of Definitions", 1999, p. 12.

- ^ Robert J. Taylor, Susan B. Taylor, The Aupha Manual of Health Services Management, Jones & Bartlett Learning, 1994, p. 33, ISBN 978-0834203631

- ^ Frannie Frank Humplick, Azadeh Moini Araghi, "Is There an Optimal Structure for Decentralized Provision of Roads?", World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 1996, p. 35.

- ^ Abbass F. Alkhafaji, Strategic Management: Formulation, Implementation, and Control in a Dynamic Environment, Psychology Press, 2003, p. 184, ISBN 978-0789018106

- ^ Ehtisham Ahmad, Vito Tanzi, Managing Fiscal Decentralization, Routledge, 2003, p. 182 Archived 2016-05-27 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0203219997

- ^ Aaron Tesfaye, Political Power and Ethnic Federalism: The Struggle for Democracy in Ethiopia, University Press of America, 2002, p. 44 Archived 2016-05-02 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0761822394

- ^ Harry Ward Richardson, Urban economics, Dryden Press, 1978, pp. 107, 133, 159 Archived 2016-05-13 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Allen G Noble, Frank J. Costa, Preserving the Legacy: Concepts in Support of Sustainability, Lexington Books, 1999, p. 214 Archived 2016-05-13 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0739100158

- ^ "Decentralization: A Sampling of Definitions", 1999, p. 21.

- ^ H.F.W. Dubois and G. Fattore, Definitions and typologies in public administration research: the case of decentralization, International Journal of Public Administration, Volume 32, Issue 8, 2009, pp. 704–27.

- ^ "Decentralization: A Sampling of Definitions", 1999, p. 19.

- ^ Cameron, David R.; Ranis, Gustav; Zinn, Annalisa (12 April 2006). Globalization and Self-Determination. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203086636. ISBN 978-0415770224.

- ^ Henry Cabot Lodge, Volume 1 of The History of Nations, H. W. Snow, 1910, p. 164 Archived 2016-05-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Stephen K. Sanderson, Civilizations and World Systems: Studying World-Historical Change, Rowman & Littlefield, 1995, pp. 118–19 Archived 2016-04-25 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0761991052

- ^ Yildiz Atasoy, Hegemonic Transitions, the State and Crisis in Neoliberal Capitalism, Volume 7 of Routledge Studies in Governance and Change in the Global Era, Taylor & Francis US, 2009, pp. 65–67 Archived 2016-06-17 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0415473842

- ^ Christopher K. Chase-Dunn, Thomas D. Hall, Rise and Demise: Comparing World Systems, Westview Press, 1997, pp. 20, 33 Archived 2016-05-17 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0813310060

- ^ Editors: S. N. Mishra, Anil Dutta Mishra, Sweta Mishra, Public Governance and Decentralisation: Essays in Honour of T.N. Chaturvedi, Mittal Publications, 2003, p. 229 Archived 2016-05-01 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-8170999188

- ^ "Decentralization: A Sampling of Definitions", 1999, pp. 5–8.

- ^ Managing Decentralisation: A New Role for Labour Market Policy, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Local Economic and Employment Development (Program), OECD Publishing, 2003, p 135 Archived 2016-04-30 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-9264104709

- ^ a b c d e Spina, Nicholas (July 2013). "Explaining political decentralization in parliamentary democracies". Comparative European Politics. 11 (4): 428–457. doi:10.1057/cep.2012.23. S2CID 144308683. ProQuest 1365933707.

- ^ Treisman, Daniel (2007). The architecture of government: rethinking political decentralization. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521872294.

- ^ Rosenblatt, Fernando; Bidegain, Germán; Monestier, Felipe; Rodríguez, Rafael Piñeiro (2015). "A Natural Experiment in Political Decentralization: Local Institutions and Citizens' Political Engagement in Uruguay". Latin American Politics and Society. 57 (2): 91–110. doi:10.1111/j.1548-2456.2015.00268.x. S2CID 154689249.

- ^ a b Lyon, Aisling (2015). "Political decentralization and the strengthening of consensual, participatory local democracy in the Republic of Macedonia". Democratization. 22: 157–178. doi:10.1080/13510347.2013.834331. S2CID 145166616.

- ^ a b James, Manor (31 March 1999). "The political economy of democratic decentralization".

- ^ a b Somin, Ilya (2013). Democracy and Political Ignorance: Why Smaller Government is Smarter. ProQuest: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804789318.

- ^ Renko, Vappu; Johannisson, Jenny; Kangas, Anita; Blomgren, Roger (16 April 2022). "Pursuing decentralisation: regional cultural policies in Finland and Sweden". International Journal of Cultural Policy. 28 (3): 342–358. doi:10.1080/10286632.2021.1941915. ISSN 1028-6632.

- ^ Fan, C. Simon; Lin, Chen; Treisman, Daniel (February 2009). "Political decentralization and corruption: Evidence from around the world". Journal of Public Economics. 93 (1–2): 14–34. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2008.09.001. hdl:10722/192328.

- ^ a b c d e Different forms of decentralization Archived 2013-05-26 at the Wayback Machine, Earth Institute of Columbia University, accessed February 5, 2013.

- ^ "Decentralization: A Sampling of Definitions", 1999, p. 8.

- ^ By the way chosen by the Italian Supreme Court, the regional legislature is allowed to add its administrative penalties to national criminal punishment: Buonomo, Giampiero (2004). "Patrimonio dello Stato: le norme speciali e il taglio abusivo di bosco". Diritto&Giustizia Edizione Online. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016.

- ^ Summary of Janet Kodras Archived 2012-06-16 at the Wayback Machine, "Restructuring the State: Devolution, Privatization, and the Geographic Redistribution of Power and Capacity in Governance", from State Devolution in America: Implications for a Diverse Society, Edited by Lynn Staeheli, Janet Kodras, and Colin Flint, Urban Affairs Annual Reviews 48, SAGE, 1997, pp. 79–68 at Restructuring local government project Archived 2013-01-17 at the Wayback Machine website.

- ^ John Stossel, "Private charity would do much more – if government hadn't crowded it out Archived 2013-02-09 at the Wayback Machine", Jewish World Review, August 24, 2005.

- ^ David King, Fiscal Tiers: The Economics of Multilevel Government, George Allen and Unwin, 1984.

- ^ Nico Groenendijk, "Fiscal federalism Revisited" paper presented at Institutions in Transition Conference organized by IMAD, Slovenia Ljublijana.

- ^ "Decentralization: A Sampling of Definitions", 1999, p. 18.

- ^ Intergovernmental Fiscal Relations Archived 2013-06-16 at the Wayback Machine, Decentralization and Subnational Economies project, World Bank website, accessed February 9, 2013.

- ^ Winston, Clifford (1998). "US industry adjustment to economic deregulation". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 12 (3): 89–110. doi:10.1257/jep.12.3.89.

- ^ Jerry Taylor and Peter Van Doren, Short-Circuited Archived 2013-06-17 at the Wayback Machine, The Wall Street Journal, August 30, 2007, reprinted at Cato Institute website.

- ^ Calabria, Mark A. (2009). "Did Deregulation Cause the Financial Crisis?". CATO Institute.

- ^ "485 K.P.Kannan, People's planning, Kerala's dilemma". Archived from the original on 29 April 2015.

- ^ Auriol, Emmanuelle; Benaim, Michel (1 June 2000). "Standardization in Decentralized Economies" (PDF). American Economic Review. 90 (3): 550–570. doi:10.1257/aer.90.3.550. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 July 2018.

- ^ Smith, Vernon L.; Simmons, Emily (9 December 1999). "How and Why to Privatize Federal Lands". CATO Institute.

- ^ Larson, Anne M. (August 2003). "Decentralisation and forest management in Latin America: towards a working model". Public Administration and Development. 23 (3): 211–226. doi:10.1002/pad.271. S2CID 39722511.

- ^ I. Scoones, Beyond Farmer First, London: Intermediate technology publications.

- ^ Larson, Anne M (January 2002). "Natural Resources and Decentralization in Nicaragua: Are Local Governments Up to the Job?". World Development. 30 (1): 17–31. doi:10.1016/s0305-750x(01)00098-5.

- ^ Binkley, Robert C. Realism and Nationalism 1852–1871. Read Books. p. 118

- ^ "The revolution abolishes private ownership of the means of production and distribution, and with it goes capitalistic business. Personal possession remains only in the things you use. Thus, your watch is your own, but the watch factory belongs to the people."[1] Archived 23 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine Alexander Berkman. "What Is Communist Anarchism?" What is Communist Anarchism?. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ As Noam Chomsky put it, a consistent libertarian "must oppose private ownership of the means of production and the wage slavery, which is a component of this system, as incompatible with the principle that labor must be freely undertaken and under the control of the producer". Chomsky (2003) p. 26 Archived 2016-05-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Paul Zarembka. Transitions in Latin America and in Poland and Syria. Emerald Group Publishing, 2007. p. 25

- ^ Guerin, Daniel. Anarchism: A Matter of Words: "Some contemporary anarchists have tried to clear up the misunderstanding by adopting a more explicit term: they align themselves with libertarian socialism or communism." Faatz, Chris, Towards a Libertarian Socialism.

- ^ Ostergaard, Geoffrey. "Anarchism". A Dictionary of Marxist Thought. Blackwell Publishing, 1991. p. 21.

- ^ Chomsky (2004) p. 739

- ^ Ross, Jeffery Ian. Controlling State Crime Archived 2015-03-18 at the Wayback Machine, Transaction Publishers (2000) p. 400 ISBN 0-7658-0695-9

- ^ Ackelsberg, Martha A. (2005). Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women. AK Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-1902593968.

- ^ Rocker, Rudolf (2004). Anarcho-Syndicalism: Theory and Practice. AK Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-1902593920.

- ^ Spiegel, Henry. The Growth of Economic Thought Duke University Press (1991) p. 446

- ^ Paul, Ellen Frankel et al. Problems of Market Liberalism Cambridge University Press (1998) p. 305

- ^ Marvin Victor Zelkowitz, Editor, Advances in Computers, Volume 82, Academic Press, 2011, p. 3 Archived 2016-05-28 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0123855138

- ^ Eleanor Doyle, The Economic System, John Wiley & Sons, 2005, p. 61 Archived 2016-06-23 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0470015179

- ^ Friedrich von Hayek, The Road to Serfdom: Text and documents – the definitive edition; Volume 2 of Collected Works of F. A. Hayek, edited by Bruce Caldwell, University of Chicago Press, 2009, p. 94 Archived 2016-05-15 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0226320533

- ^ Bruce M. Owen, Antecedents to Net Neutrality Archived 2013-06-17 at the Wayback Machine, Cato Institute publication "Regulation", Fall, 2007, p. 16.

- ^ * Tibor R. Machan, Private Rights & Public Illusions, Transaction Publishers, 1995, p. 99 Machan, Tibor R. Private Rights and Public Illusions. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 9781412831925. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), ISBN 978-1412831925- Tibor R. Machan, editor, The Libertarian Alternative, Nelson-Hall, 1974 included Yale Brozen's, "Is Government the source of monopoly? and other essays", Cato Institute, 1980; and Roy Childs' "Big Business and the Rise of American Statism", 1971, Reason.

- ^ Gabriel Kolko, The Triumph of Conservatism: A Reinterpretation of American History, 1900–1916, Chapter Two: "Competition and Decentralization: The Failure to Rationalize Industry", Simon and Schuster, 2008, pp. 26–56, 141, 220, 243, 351 Archived 2016-05-11 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-1439118726

- ^ Roy Childs, "Big Business and the Rise of American Statism Archived 2013-01-30 at the Wayback Machine", Reason, 1971.

- ^ John Montgomery, The New Wealth of Cities: City Dynamics and the Fifth Wave, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2008, p. 2 Archived 2016-05-22 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0754674153

- ^ Jane Jacobs, The Question of Separatism: Quebec and the Struggle over Sovereignty, (1980 Random House and 2011 Baraka Books), ISBN 978-1926824062

- ^ Gopal Balakrishnan, Mapping the Nation, Verso, 1996, p. 277 Archived 2016-06-10 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-1859840603

- ^ Jacobs, Jane (1984). Cities and the Wealth of Nations: Principles of Economic Life. Vintage Books. ISBN 0-394-72911-0.

- ^ Ouchi, William G. (April 2006). "Power to the Principals: Decentralization in Three Large School Districts". Organization Science. 17 (2): 298–307. doi:10.1287/orsc.1050.0172.

- ^ Zábojník, Ján (January 2002). "Centralized and Decentralized Decision Making in Organizations". Journal of Labor Economics. 20 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1086/323929. S2CID 222328856.

- ^ Aghion, P.; Bloom, N.; Van Reenen, J. (1 May 2014). "Incomplete Contracts and the Internal Organization of Firms". Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization. 30 (suppl 1): i37 – i63. doi:10.1093/jleo/ewt003.

- ^ Aghion, Philippe; Bloom, Nicholas; Lucking, Brian; Sadun, Raffaella; Van Reenen, John (1 January 2021). "Turbulence, Firm Decentralization, and Growth in Bad Times". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 13 (1): 133–169. doi:10.1257/app.20180752. hdl:10419/161329. S2CID 234358121.

- ^ Leiponen, Aija; Helfat, Constance E. (June 2011). "Location, Decentralization, and Knowledge Sources for Innovation". Organization Science. 22 (3): 641–658. doi:10.1287/orsc.1100.0526.

- ^ Schilling, Melissa A. (2017). Strategic management of technological innovation (5th ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 978-1-259-53906-0. OCLC 929155407.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Bucic, Tania; Gudergan, Siegfried P. (2004). "The Impact of Organizational Settings on Creativity and Learning in Alliances". M@n@gement. 7 (3): 257–273. doi:10.3917/mana.073.0257. hdl:10453/5995.

- ^ Foss, Nicolai J.; Laursen, Keld; Pedersen, Torben (August 2011). "Linking Customer Interaction and Innovation: The Mediating Role of New Organizational Practices". Organization Science. 22 (4): 980–999. doi:10.1287/orsc.1100.0584.

- ^ Burton, M. Diane; Colombo, Massimo G.; Rossi-Lamastra, Cristina; Wasserman, Noam (September 2019). "The organizational design of entrepreneurial ventures". Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal. 13 (3): 243–255. doi:10.1002/sej.1332. S2CID 201351323.

- ^ Eggimann, S. The optimal degree of centralisation for wastewater infrastructures. A model-based geospatial economic analysis Doctoral Thesis ETH Zurich., 30. November 2016.

- ^ Jeremy Magliaro, Amory Lovins, Valuing Decentralized Wastewater Technologies: A Catalog of Benefits, Costs, and Economic Analysis Techniques Archived 2013-03-05 at the Wayback Machine, Rocky Mountain Institute, 2004.

- ^ Lawrence D. Smith, Reform and Decentralization of Agricultural Services: A Policy Framework, United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, 2001, p. 2010–211 Archived 2016-06-10 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-9251046449

- ^ Lawrence D. Smith, Reform and Decentralization of Agricultural Services: A Policy Framework, 2001.

- ^ Maggie Koerth-Baker, What We Talk About When We Talk About the Decentralization of Energy Archived 2016-12-31 at the Wayback Machine, The Atlantic, April 16, 2012.

- ^ "How blockchain technology could electrify the energy industry". www.theneweconomy.com. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ Fred E. Foldvary, Daniel Bruce Klein, Editors, The Half-Life of Policy Rationales: How New Technology Affects Old Policy Issues NYU Press, 2003, pp. 1, 184 Archived 2016-05-01 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0814747773

- ^ Eggimann, Sven; Truffer, Bernhard; Maurer, Max (November 2015). "To connect or not to connect? Modelling the optimal degree of centralisation for wastewater infrastructures". Water Research. 84: 218–231. Bibcode:2015WatRe..84..218E. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2015.07.004. hdl:1874/322959. PMID 26247101.

- ^ Chandler, Daniel; Munday, Rod (January 2011), "Information technology", A Dictionary of Media and Communication (first ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-956875-8, retrieved 1 August 2012 (subscription required)

- ^ John Baschab, Jon Piot, The Executive's Guide to Information Technology, John Wiley & Sons, 2007, p. 119 Archived 2016-05-01 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0470135914

- ^ G. David Garson, Modern Public Information Technology Systems: Issues and Challenges, IGI Global, 2007, p. 115–20 Archived 2016-05-19 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-1599040530

- ^ a b Kopfstein, Janus (12 December 2013). "The Mission To Decentralize The Internet". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ Thomas W. Malone, Robert Laubacher, Michael S. Scott Morton, Inventing Organizations 21st Century, MIT Press, 2003, 65–66 Archived 2016-04-28 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0262632737

- ^ Chris DiBona, Mark Stone, Danese Cooper, Open Sources 2.0: The Continuing Evolution, O'Reilly Media, Inc., 2008, p. 316 Archived 2016-06-10 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0596553890

- ^ Axel Bruns, Blogs, Wikipedia, Second Life, and Beyond: From Production to Produsage, Peter Lang, 2008, p. 80 Archived 2016-05-28 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0820488660

- ^ Joseph Nye, The politics of the information age Archived 2013-02-21 at the Wayback Machine, Prague Post, February 13, 2010.

- ^ Adi Kamdar and Peter Eckersley, Can the FCC Create Public "Super WiFi Networks"? Archived 2013-02-12 at the Wayback Machine, Electronic Frontier Foundation, February 5, 2013.

- ^ Jennifer Holt, Alisa Perren, Media Industries: History, Theory, and Method, John Wiley & Sons, 2011, pp. 1995–97 Archived 2016-05-04 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-1444360233

- ^ David G. Post and David R. Johnson, 'Chaos Prevailing on Every Continent': Towards a New Theory of Decentralized Decision-Making in Complex Systems Archived 2011-08-26 at the Wayback Machine, Chicago-Kent Law Review, Vol. 73, No. 4, p. 1055, 1998, full version at David G. Post's Temple University website Archived 2012-10-03 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Pandl, Konstantin D.; Thiebes, Scott; Schmidt-Kraepelin, Manuel; Sunyaev, Ali (2020). "On the Convergence of Artificial Intelligence and Distributed Ledger Technology: A Scoping Review and Future Research Agenda". IEEE Access. 8: 57075–57095. arXiv:2001.11017. Bibcode:2020IEEEA...857075P. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2981447. ISSN 2169-3536.

- ^ Anderson, Mally (7 February 2019). "Exploring Decentralization: Blockchain Technology and Complex Coordination". Journal of Design and Science.

- ^ Zarrin, Javad; Wen Phang, Hao; Babu Saheer, Lakshmi; Zarrin, Bahram (December 2021). "Blockchain for decentralization of internet: prospects, trends, and challenges". Cluster Computing. 24 (4): 2841–2866. doi:10.1007/s10586-021-03301-8. PMC 8122205. PMID 34025209.

- ^ Gururaj, H. L.; Manoj Athreya, A.; Kumar, Ashwin A.; Holla, Abhishek M.; Nagarajath, S. M.; Ravi Kumar, V. (2020). "Blockchain". Cryptocurrencies and Blockchain Technology Applications. pp. 1–24. doi:10.1002/9781119621201.ch1. ISBN 9781119621164. S2CID 242394449.

- ^ McGinnis, John; Roche, Kyle (October 2019). "Bitcoin: Order Without Law in the Digital Age". Indiana Law Journal. 94 (4): 6.

- ^ Litvack Ilene, Jennie; Seddon, Jessica (1999). Decentralization briefing notes. Washington, DC: World Bank Institute. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ Chapter 2. Decentralization and environmental issues Archived 2013-01-02 at the Wayback Machine, "Environment in decentralized development", United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization ("FAO"), accessed February 23, 2013; also see Environment in Decentralized Decision Making, An Overview Archived 2013-05-29 at the Wayback Machine, Agricultural Policy Support Service, Policy Assistance Division, FAO, Rome, Italy, November 2005.

- ^ Summary of Remy Prud'homme, "The Dangers of Decentralization Archived 2012-06-16 at the Wayback Machine", World Bank Research Observer, 10(2):201, 1995, linked from Decentralization Archived 2012-10-26 at the Wayback Machine, article "Restructuring local government project" of Dr. Mildred Warner.

Further reading

[edit]- Aucoin, Peter, and Herman Bakvis. The Centralization-Decentralization Conundrum: Organization and Management in the Canadian Government (IRPP, 1988), ISBN 978-0886450700

- Buck, Charles (Charlie) (2022). ""Laboratories of Democracry" Through Decentralization: TWO CHEERS FOR FEDERALISM". Federalism-E. 23 (1): 51–60. doi:10.24908/fede.v23i1.15352.

- Campbell, Tim. Quiet Revolution: Decentralization and the Rise of Political Participation in Latin American Cities (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2003), ISBN 978-0822957966.

- Faguet, Jean-Paul. Decentralization and Popular Democracy: Governance from Below in Bolivia, (University of Michigan Press, 2012), ISBN 978-0472118199.

- Fisman, Raymond and Roberta Gatti (2000). Decentralization and Corruption: Evidence Across Countries, Journal of Public Economics, Vol.83, No.3, pp. 325–45.

- Frischmann, Eva. Decentralization and Corruption. A Cross-Country Analysis, (Grin Verlag, 2010), ISBN 978-3640710959.

- Miller, Michelle Ann, ed. Autonomy and Armed Separatism in South and Southeast Asia (Singapore: ISEAS, 2012).

- Miller, Michelle Ann. Rebellion and Reform in Indonesia. Jakarta's Security and Autonomy Policies in Aceh (London and New York: Routledge, 2009).

- Rosen, Harvey S., ed.. Fiscal Federalism: Quantitative Studies National Bureau of Economic Research Project Report, NBER-Project Report, University of Chicago Press, 2008), ISBN 978-0226726236.