Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Exoenzyme

View on Wikipedia

An exoenzyme, or extracellular enzyme, is an enzyme that is secreted by a cell and functions outside that cell. Exoenzymes are produced by both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells and have been shown to be a crucial component of many biological processes. Most often these enzymes are involved in the breakdown of larger macromolecules. The breakdown of these larger macromolecules is critical for allowing their constituents to pass through the cell membrane and enter into the cell. For humans and other complex organisms, this process is best characterized by the digestive system which breaks down solid food[1] via exoenzymes. The small molecules, generated by the exoenzyme activity, enter into cells and are utilized for various cellular functions. Bacteria and fungi also produce exoenzymes to digest nutrients in their environment, and these organisms can be used to conduct laboratory assays to identify the presence and function of such exoenzymes.[2] Some pathogenic species also use exoenzymes as virulence factors to assist in the spread of these disease-causing microorganisms.[3] In addition to the integral roles in biological systems, different classes of microbial exoenzymes have been used by humans since pre-historic times for such diverse purposes as food production, biofuels, textile production and in the paper industry.[4] Another important role that microbial exoenzymes serve is in the natural ecology and bioremediation of terrestrial and marine[5] environments.

History

[edit]Very limited information is available about the original discovery of exoenzymes. According to Merriam-Webster dictionary, the term "exoenzyme" was first recognized in the English language in 1908.[6] The book "Intracellular Enzymes: A Course of Lectures Given in the Physiological," by Horace Vernon is thought to be the first publication using this word in that year.[7] Based on the book, it can be assumed that the first known exoenzymes were pepsin and trypsin, as both are mentioned by Vernon to have been discovered by scientists Briike and Kiihne before 1908.[8]

Function

[edit]In bacteria and fungi, exoenzymes play an integral role in allowing the organisms to effectively interact with their environment. Many bacteria use digestive enzymes to break down nutrients in their surroundings. Once digested, these nutrients enter the bacterium, where they are used to power cellular pathways with help from endoenzymes.[9]

Many exoenzymes are also used as virulence factors. Pathogens, both bacterial and fungal, can use exoenzymes as a primary mechanism with which to cause disease.[citation needed] The metabolic activity of the exoenzymes allows the bacterium to invade host organisms by breaking down the host cells' defensive outer layers or by necrotizing body tissues of larger organisms.[3] Many gram-negative bacteria have injectisomes, or flagella-like projections, to directly deliver the virulent exoenzyme into the host cell using a type three secretion system.[10] With either process, pathogens can attack the host cell's structure and function, as well as its nucleic DNA.[11]

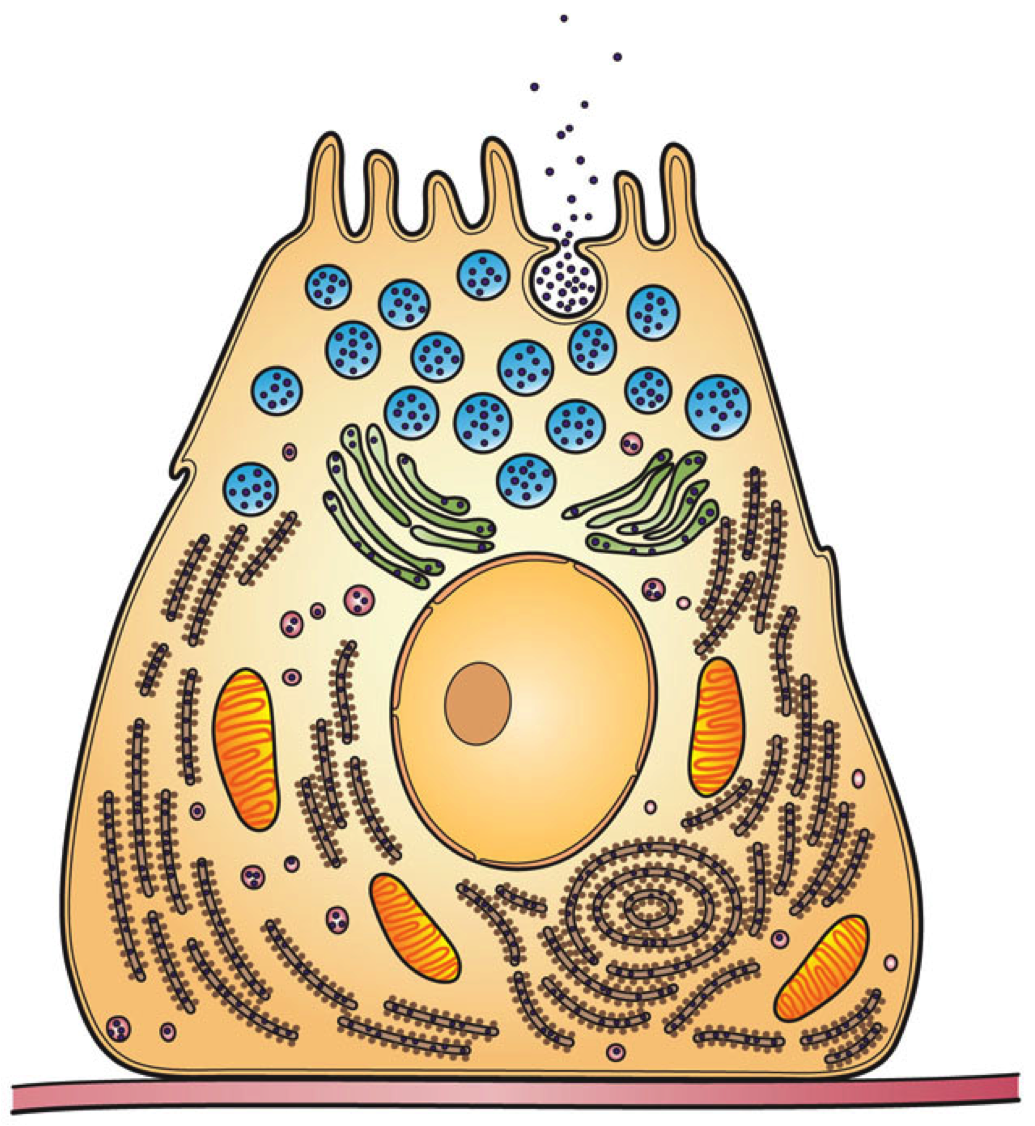

In eukaryotic cells, exoenzymes are manufactured like any other enzyme via protein synthesis, and are transported via the secretory pathway. After moving through the rough endoplasmic reticulum, they are processed through the Golgi apparatus, where they are packaged in vesicles and released out of the cell.[12] In humans, a majority of such exoenzymes can be found in the digestive system and are used for metabolic breakdown of macronutrients via hydrolysis. Breakdown of these nutrients allows for their incorporation into other metabolic pathways.[13]

Examples of exoenzymes as virulence factors

[edit]Source:[3]

Necrotizing enzymes

[edit]Necrotizing enzymes destroy cells and tissue. One of the best known examples is an exoenzyme produced by Streptococcus pyogenes that causes necrotizing fasciitis in humans.

Coagulase

[edit]By binding to prothrombin, coagulase facilitates clotting in a cell by ultimately converting fibrinogen to fibrin. Bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus use the enzyme to form a layer of fibrin around their cell to protect against host defense mechanisms.

Kinases

[edit]The opposite of coagulase, kinases can dissolve clots. S. aureus can also produce staphylokinase, allowing them to dissolve the clots they form, to rapidly diffuse into the host at the correct time.[14]

Hyaluronidase

[edit]Similar to collagenase, hyaluronidase enables a pathogen to penetrate deep into tissues. Bacteria such as Clostridium do so by using the enzyme to dissolve collagen and hyaluronic acid, the protein and saccharides, respectively, that hold tissues together.

Hemolysins

[edit]Hemolysins target erythrocytes, a.k.a. red blood cells. Attacking and lysing these cells harms the host organism, and provides the microorganism, such as the fungus Candida albicans, with a source of iron from the lysed hemoglobin.[15] Organisms can either by alpha-hemolytic, beta-hemolytic, or gamma-hemolytic (non-hemolytic).

Examples of digestive exoenzymes

[edit]Amylases

[edit]

Amylases are a group of extracellular enzymes (glycoside hydrolases) that catalyze the hydrolysis of starch into maltose. These enzymes are grouped into three classes based on their amino acid sequences, mechanism of reaction, method of catalysis and their structure.[16] The different classes of amylases are α-amylases, β-amylases, and glucoamylases. The α-amylases hydrolyze starch by randomly cleaving the 1,4-a-D-glucosidic linkages between glucose units, β-amylases cleave non-reducing chain ends of components of starch such as amylose, and glucoamylases hydrolyze glucose molecules from the ends of amylose and amylopectin.[17] Amylases are critically important extracellular enzymes and are found in plants, animals, and microorganisms. In humans, amylases are secreted by the pancreas and salivary glands, with both sources of the enzyme required for complete starch hydrolysis.[18]

Lipoprotein lipase

[edit]Lipoprotein lipase (LPL) is a type of digestive enzyme that helps regulate the uptake of triacylglycerols from chylomicrons and other low-density lipoproteins from fatty tissues in the body.[19] The exoenzymatic function allows it to break down the triacylglycerol into two free fatty acids and one molecule of monoacylglycerol. LPL can be found in endothelial cells in fatty tissues, such as adipose, cardiac, and muscle.[19] Lipoprotein lipase is downregulated by high levels of insulin,[20] and upregulated by high levels of glucagon and adrenaline.[19]

Pectinase

[edit]Pectinases, also called pectolytic enzymes, are a class of exoenzymes that are involved in the breakdown of pectic substances, most notably pectin.[21] Pectinases can be classified into two different groups based on their action against the galacturonan backbone of pectin: de-esterifying and depolymerizing.[22] These exoenzymes can be found in both plants and microbial organisms including fungi and bacteria.[23] Pectinases are most often used to break down the pectic elements found in plants and plant-derived products.

Pepsin

[edit]Discovered in 1836, pepsin was one of the first enzymes to be classified as an exoenzyme.[8] The enzyme is first made in the inactive form, pepsinogen by chief cells in the lining of the stomach.[24] With an impulse from the vagus nerve, pepsinogen is secreted into the stomach, where it mixes with hydrochloric acid to form pepsin.[25] Once active, pepsin works to break down proteins in foods such as dairy, meat, and eggs.[24] Pepsin works best at the pH of gastric acid, 1.5 to 2.5, and is deactivated when the acid is neutralized to a pH of 7.[24]

Trypsin

[edit]Also one of the first exoenzymes to be discovered, trypsin was named in 1876, forty years after pepsin.[26] This enzyme is responsible for the breakdown of large globular proteins and its activity is specific to cleaving the C-terminal sides of arginine and lysine amino acid residues.[26] It is the derivative of trypsinogen, an inactive precursor that is produced in the pancreas.[27] When secreted into the small intestine, it mixes with enterokinase to form active trypsin. Due to its role in the small intestine, trypsin works at an optimal pH of 8.0.[28]

Bacterial assays

[edit]The production of a particular digestive exoenzyme by a bacterial cell can be assessed using plate assays. Bacteria are streaked across the agar, and are left to incubate. The release of the enzyme into the surroundings of the cell cause the breakdown of the macromolecule on the plate. If a reaction does not occur, this means that the bacteria does not create an exoenzyme capable of interacting with the surroundings. If a reaction does occur, it becomes clear that the bacteria does possess an exoenzyme, and which macromolecule is hydrolyzed determines its identity.[2]

Amylase

[edit]Amylase breaks down carbohydrates into mono- and disaccharides, so a starch agar must be used for this assay. Once the bacteria is streaked on the agar, the plate is flooded with iodine. Since iodine binds to starch but not its digested by-products, a clear area will appear where the amylase reaction has occurred. Bacillus subtilis is a bacterium that results in a positive assay as shown in the picture.[2]

Lipase

[edit]Lipase assays are done using a lipid agar with a spirit blue dye. If the bacteria has lipase, a clear streak will form in the agar, and the dye will fill the gap, creating a dark blue halo around the cleared area. Staphylococcus epidermidis results in a positive lipase assay.[2]

Biotechnological and industrial applications

[edit]Microbiological sources of exoenzymes including amylases, proteases, pectinases, lipases, xylanases, and cellulases are used for a wide range of biotechnological and industrial uses including biofuel generation, food production, paper manufacturing, detergents and textile production.[4] Optimizing the production of biofuels has been a focus of researchers in recent years and is centered around the use of microorganisms to convert biomass into ethanol. The enzymes that are of particular interest in ethanol production are cellobiohydrolase which solubilizes crystalline cellulose and xylanase that hydrolyzes xylan into xylose.[29] One model of biofuel production is the use of a mixed population of bacterial strains or a consortium that work to facilitate the breakdown of cellulose materials into ethanol by secreting exoenzymes such as cellulases and laccases.[29] In addition to the important role it plays in biofuel production, xylanase is utilized in a number of other industrial and biotechnology applications due to its ability to hydrolyze cellulose and hemicellulose. These applications include the breakdown of agricultural and forestry wastes, working as a feed additive to facilitate greater nutrient uptake by livestock, and as an ingredient in bread making to improve the rise and texture of the bread.[30]

Lipases are one of the most used exoenzymes in biotechnology and industrial applications. Lipases make ideal enzymes for these applications because they are highly selective in their activity, they are readily produced and secreted by bacteria and fungi, their crystal structure is well characterized, they do not require cofactors for their enzymatic activity, and they do not catalyze side reactions.[31] The range of uses of lipases encompasses production of biopolymers, generation of cosmetics, use as a herbicide, and as an effective solvent.[31] However, perhaps the most well known use of lipases in this field is its use in the production of biodiesel fuel. In this role, lipases are used to convert vegetable oil to methyl- and other short-chain alcohol esters by a single transesterification reaction.[32]

Cellulases, hemicellulases and pectinases are different exoenzymes that are involved in a wide variety of biotechnological and industrial applications. In the food industry these exoenzymes are used in the production of fruit juices, fruit nectars, fruit purees and in the extraction of olive oil among many others.[33] The role these enzymes play in these food applications is to partially breakdown the plant cell walls and pectin. In addition to the role they play in food production, cellulases are used in the textile industry to remove excess dye from denim, soften cotton fabrics, and restore the color brightness of cotton fabrics.[33] Cellulases and hemicellulases (including xylanases) are also used in the paper and pulp industry to de-ink recycled fibers, modify coarse mechanical pulp, and for the partial or complete hydrolysis of pulp fibers.[33] Cellulases and hemicellulases are used in these industrial applications due to their ability to hydrolyze the cellulose and hemicellulose components found in these materials.

Bioremediation applications

[edit]

Bioremediation is a process in which pollutants or contaminants in the environment are removed through the use of biological organisms or their products. The removal of these often hazardous pollutants is mostly carried out by naturally occurring or purposely introduced microorganisms that are capable of breaking down or absorbing the desired pollutant. The types of pollutants that are often the targets of bioremediation strategies are petroleum products (including oil and solvents) and pesticides.[34] In addition to the microorganisms ability to digest and absorb the pollutants, their secreted exoenzymes play an important role in many bioremediation strategies.[35]

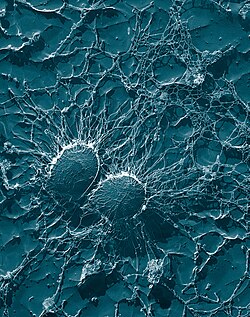

Fungi have been shown to be viable organisms to conduct bioremediation and have been used to aid in the decontamination of a number of pollutants including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), pesticides, synthetic dyes, chlorophenols, explosives, crude oil, and many others.[36] While fungi can breakdown many of these contaminants intracellularly, they also secrete numerous oxidative exoenzymes that work extracellularly. One critical aspect of fungi in regards to bioremediation is that they secrete these oxidative exoenzymes from their ever elongating hyphal tips.[36] Laccases are an important oxidative enzyme that fungi secrete and use oxygen to oxidize many pollutants. Some of the pollutants that laccases have been used to treat include dye-containing effluents from the textile industry, wastewater pollutants (chlorophenols, PAHs, etc.), and sulfur-containing compounds from coal processing.[36]

Bacteria are also a viable source of exoenzymes capable of facilitating the bioremediation of the environment. There are many examples of the use of bacteria for this purpose and their exoenzymes encompass many different classes of bacterial enzymes. Of particular interest in this field are bacterial hydrolases as they have an intrinsic low substrate specificity and can be used for numerous pollutants including solid wastes.[37] Plastic wastes including polyurethanes are particularly hard to degrade, but an exoenzyme has been identified in a Gram-negative bacterium, Comamonas acidovorans, that was capable of degrading polyurethane waste in the environment.[37] Cell-free use of microbial exoenzymes as agents of bioremediation is also possible although their activity is often not as robust and introducing the enzymes into certain environments such as soil has been challenging.[37] In addition to terrestrial based microorganisms, marine based bacteria and their exoenzymes show potential as candidates in the field of bioremediation. Marine based bacteria have been utilized in the removal of heavy metals, petroleum/diesel degradation and in the removal of polyaromatic hydrocarbons among others.[38]

References

[edit]- ^ Kong F, Singh RP (June 2008). "Disintegration of solid foods in human stomach". Journal of Food Science. 73 (5): R67–80. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2008.00766.x. PMID 18577009.

- ^ a b c d Roberts, K. "Exoenzymes". Prince George's Community College. Archived from the original on 13 June 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ a b c Duben-Engelkirk, Paul G. Engelkirk, Janet (2010). Burton's microbiology for the health sciences (9th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 173–174. ISBN 978-1-60547-673-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Thiel, ed. by Joachim Reitner, Volker. Encyclopedia of geobiology. Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 355–359. ISBN 978-1-4020-9212-1.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Arnosti C (15 January 2011). "Microbial extracellular enzymes and the marine carbon cycle". Annual Review of Marine Science. 3 (1): 401–25. Bibcode:2011ARMS....3..401A. doi:10.1146/annurev-marine-120709-142731. PMID 21329211.

- ^ "Merriam-Webster". Retrieved 2013-10-26.

- ^ "Lexic.us". Retrieved 2013-10-26.

- ^ a b Vernon, Horace. "Intracellular Enzymes: A Course of Lectures Given in the Physiological". Retrieved 2013-10-26.

- ^ Kaiser, Gary. "Lab 8: Identification of Bacteria Through Biochemical Testing". Biol 230 Lab Manual. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ Erhardt M, Namba K, Hughes KT (November 2010). "Bacterial nanomachines: the flagellum and type III injectisome". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2 (11) a000299. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a000299. PMC 2964186. PMID 20926516.

- ^ McGuffie EM, Fraylick JE, Hazen-Martin DJ, Vincent TS, Olson JC (July 1999). "Differential sensitivity of human epithelial cells to Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S". Infection and Immunity. 67 (7): 3494–503. doi:10.1128/IAI.67.7.3494-3503.1999. PMC 116536. PMID 10377131.

- ^ Lodish, Harvey (2008). Molecular cell biology (6th ed., [2nd print.]. ed.). New York [u.a.]: Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-7601-7.

- ^ Andrews, Lary. "Supplemental Enzymes for Digestion". Health and Healing Research. Archived from the original on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ Todar, Kenneth. "Mechanisms of Bacterial Pathogenicity". Todar's Online Textbook of Bacteriology. Kenneth Todar, PhD. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ Favero D, Furlaneto-Maia L, França EJ, Góes HP, Furlaneto MC (February 2014). "Hemolytic factor production by clinical isolates of Candida species". Current Microbiology. 68 (2): 161–6. doi:10.1007/s00284-013-0459-6. PMID 24048697. S2CID 253807898.

- ^ Sharma A, Satyanarayana T (2013). "Microbial acid-stable alpha-amylases: Characteristics, genetic engineering and applications". Process Biochemistry. 48 (2): 201–211. doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2012.12.018.

- ^ Pandey A, Nigam P, Soccol CR, Soccol VT, Singh D, Mohan R (2000). "Advances in microbial amylases". Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 31 (2): 135–52. doi:10.1042/ba19990073. PMID 10744959.

- ^ Pandol, Stephen (2010). "The Exocrine Pancreas". Colloquium Series on Integrated Systems Physiology: From Molecule to Function. 3 (2). Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences: 1–64. doi:10.4199/C00026ED1V01Y201102ISP014. PMID 21634067. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ a b c Mead JR, Irvine SA, Ramji DP (December 2002). "Lipoprotein lipase: structure, function, regulation, and role in disease". Journal of Molecular Medicine. 80 (12): 753–69. doi:10.1007/s00109-002-0384-9. PMID 12483461. S2CID 40089672.

- ^ Kiens B, Lithell H, Mikines KJ, Richter EA (October 1989). "Effects of insulin and exercise on muscle lipoprotein lipase activity in man and its relation to insulin action". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 84 (4): 1124–9. doi:10.1172/JCI114275. PMC 329768. PMID 2677048.

- ^ Jayani, Ranveer Singh; Saxena, Shivalika; Gupta, Reena (1 September 2005). "Microbial pectinolytic enzymes: A review". Process Biochemistry. 40 (9): 2931–2944. doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2005.03.026.

- ^ Alimardani-Theuil, Parissa; Gainvors-Claisse, Angélique; Duchiron, Francis (1 August 2011). "Yeasts: An attractive source of pectinases—From gene expression to potential applications: A review". Process Biochemistry. 46 (8): 1525–1537. doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2011.05.010.

- ^ Gummadi, Sathyanarayana N.; Panda, T. (1 February 2003). "Purification and biochemical properties of microbial pectinases—a review". Process Biochemistry. 38 (7): 987–996. doi:10.1016/S0032-9592(02)00203-0.

- ^ a b c "Encyclopædia Britannica". Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ^ Guldvog I, Berstad A (1981). "Physiological stimulation of pepsin secretion. The role of vagal innervation". Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 16 (1): 17–25. PMID 6785873.

- ^ a b Worthington, Krystal. "Trypsin". Worthington Biochemical Corporation. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ^ "Trypsin". Free Dictionary. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ^ "Trypsin Product Information". Worthington Biochemical Corporation. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ^ a b Alper H, Stephanopoulos G (October 2009). "Engineering for biofuels: exploiting innate microbial capacity or importing biosynthetic potential?". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 7 (10): 715–23. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2186. PMID 19756010. S2CID 7785046.

- ^ Juturu V, Wu JC (1 November 2012). "Microbial xylanases: engineering, production and industrial applications". Biotechnology Advances. 30 (6): 1219–27. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.11.006. PMID 22138412.

- ^ a b Jaeger, Karl-Erich; Thorsten Eggert (2002). "Lipases for biotechnology". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 13 (4): 390–397. doi:10.1016/s0958-1669(02)00341-5. PMID 12323363.

- ^ Fan X, Niehus X, Sandoval G (2012). "Lipases as Biocatalyst for Biodiesel Production". Lipases and Phospholipases. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 861. pp. 471–83. doi:10.1007/978-1-61779-600-5_27. ISBN 978-1-61779-599-2. PMID 22426735.

- ^ a b c Bhat, M.K. (2000). "Cellulases and related enzymes in biotechnology". Biotechnology Advances. 18 (5): 355–383. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.461.2075. doi:10.1016/s0734-9750(00)00041-0. PMID 14538100.

- ^ "A Citizen's Guide to Bioremediation". United States Environmental Protection Agency. September 2012. Archived from the original on October 14, 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ Karigar CS, Rao SS (2011). "Role of microbial enzymes in the bioremediation of pollutants: a review". Enzyme Research. 2011: 1–11. doi:10.4061/2011/805187. PMC 3168789. PMID 21912739.

- ^ a b c Harms H, Schlosser D, Wick LY (March 2011). "Untapped potential: exploiting fungi in bioremediation of hazardous chemicals". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 9 (3): 177–92. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2519. PMID 21297669. S2CID 24676340.

- ^ a b c Gianfreda, Liliana; Rao, Maria A (September 2004). "Potential of extra cellular enzymes in remediation of polluted soils: a review". Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 35 (4): 339–354. doi:10.1016/j.enzmictec.2004.05.006.

- ^ Dash HR, Mangwani N, Chakraborty J, Kumari S, Das S (Jan 2013). "Marine bacteria: potential candidates for enhanced bioremediation". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 97 (2): 561–71. doi:10.1007/s00253-012-4584-0. PMID 23212672. S2CID 253773148.