Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Fixed-wing aircraft

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2024) |

A fixed-wing aircraft is a heavier-than-air aircraft, such as an airplane, which is capable of flight using aerodynamic lift. Fixed-wing aircraft are distinct from rotary-wing aircraft (in which a rotor mounted on a spinning shaft generates lift), and ornithopters (in which the wings oscillate to generate lift). The wings of a fixed-wing aircraft are not necessarily rigid; kites, hang gliders, variable-sweep wing aircraft, and airplanes that use wing morphing are all classified as fixed wing.

Gliding fixed-wing aircraft, including free-flying gliders and tethered kites, can use moving air to gain altitude. Powered fixed-wing aircraft (airplanes) that gain forward thrust from an engine include powered paragliders, powered hang gliders and ground effect vehicles. Most fixed-wing aircraft are operated by a pilot, but some are unmanned or controlled remotely or are completely autonomous (no remote pilot).

History

[edit]Kites

[edit]Kites were used approximately 2,800 years ago in China, where kite building materials were available. Leaf kites may have been flown earlier in what is now Sulawesi, based on their interpretation of cave paintings on nearby Muna Island.[1] By at least 549 AD paper kites were flying, as recorded that year, a paper kite was used as a message for a rescue mission.[2] Ancient and medieval Chinese sources report kites used for measuring distances, testing the wind, lifting men, signaling, and communication for military operations.[2]

Kite stories were brought to Europe by Marco Polo towards the end of the 13th century, and kites were brought back by sailors from Japan and Malaysia in the 16th and 17th centuries.[3] Although initially regarded as curiosities, by the 18th and 19th centuries kites were used for scientific research.[3]

Gliders and powered devices

[edit]Around 400 BC in Greece, Archytas was reputed to have designed and built the first self-propelled flying device, shaped like a bird and propelled by a jet of what was probably steam, said to have flown some 200 m (660 ft).[4][5] This machine may have been suspended during its flight.[6][7]

One of the earliest attempts with gliders was by 11th-century monk Eilmer of Malmesbury, which failed. A 17th-century account states that 9th-century poet Abbas Ibn Firnas made a similar attempt, though no earlier sources record this event.[8]

In 1799, Sir George Cayley laid out the concept of the modern airplane as a fixed-wing machine with systems for lift, propulsion, and control.[9][10] Cayley was building and flying models of fixed-wing aircraft as early as 1803, and built a successful passenger-carrying glider in 1853.[11] In 1856, Frenchman Jean-Marie Le Bris made the first powered flight, had his glider L'Albatros artificiel towed by a horse along a beach.[12] In 1884, American John J. Montgomery made controlled flights in a glider as a part of a series of gliders he built between 1883 and 1886.[13] Other aviators who made similar flights at that time were Otto Lilienthal, Percy Pilcher, and protégés of Octave Chanute.

In the 1890s, Lawrence Hargrave conducted research on wing structures and developed a box kite that lifted the weight of a man. His designs were widely adopted. He also developed a type of rotary aircraft engine, but did not create a powered fixed-wing aircraft.[14]

Powered flight

[edit]Sir Hiram Maxim built a craft that weighed 3.5 tons, with a 110-foot (34-meter) wingspan powered by two 360-horsepower (270-kW) steam engines driving two propellers. In 1894, his machine was tested with overhead rails to prevent it from rising. The test showed that it had enough lift to take off. The craft was uncontrollable, and Maxim abandoned work on it.[15]

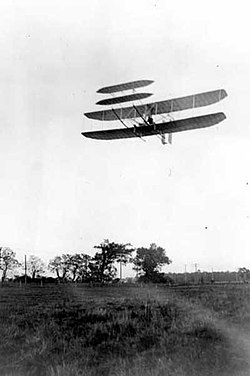

The Wright brothers' flights in 1903 with their Flyer I are recognized by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI), the standard setting and record-keeping body for aeronautics, as "the first sustained and controlled heavier-than-air powered flight".[16] By 1905, the Wright Flyer III was capable of fully controllable, stable flight for substantial periods.

In 1906, Brazilian inventor Alberto Santos Dumont designed, built and piloted an aircraft that set the first world record recognized by the Aéro-Club de France by flying the 14 bis 220 metres (720 ft) in less than 22 seconds.[17] The flight was certified by the FAI.[18]

The Bleriot VIII design of 1908 was an early aircraft design that had the modern monoplane tractor configuration. It had movable tail surfaces controlling both yaw and pitch, a form of roll control supplied either by wing warping or by ailerons and controlled by its pilot with a joystick and rudder bar. It was an important predecessor of his later Bleriot XI Channel-crossing aircraft of the summer of 1909.[19]

World War I

[edit]World War I served initiated the use of aircraft as weapons and observation platforms. The earliest known aerial victory with a synchronized machine gun-armed fighter aircraft occurred in 1915, flown by German Luftstreitkräfte Lieutenant Kurt Wintgens. Fighter aces appeared; the greatest (by number of air victories) was Manfred von Richthofen.[20]

Alcock and Brown crossed the Atlantic non-stop for the first time in 1919. The first commercial flights traveled between the United States and Canada in 1919.[citation needed]

Interwar aviation; the "Golden Age"

[edit]The so-called Golden Age of Aviation occurred between the two World Wars, during which updated interpretations of earlier breakthroughs. Innovations include Hugo Junkers' all-metal air frames in 1915 leading to multi-engine aircraft of up to 60+ meter wingspan sizes by the early 1930s, adoption of the mostly air-cooled radial engine as a practical aircraft power plant alongside V-12 liquid-cooled aviation engines, and longer and longer flights – as with a Vickers Vimy in 1919, followed months later by the U.S. Navy's NC-4 transatlantic flight; culminating in May 1927 with Charles Lindbergh's solo trans-Atlantic flight in the Spirit of St. Louis spurring ever-longer flight attempts.

World War II

[edit]Airplanes had a presence in the major battles of World War II. They were an essential component of military strategies, such as the German Blitzkrieg or the American and Japanese aircraft carrier campaigns of the Pacific.

Military gliders were developed and used in several campaigns, but were limited by the high casualty rate encountered. The Focke-Achgelis Fa 330 Bachstelze (Wagtail) rotor kite of 1942 was notable for its use by German U-boats.

Before and during the war, British and German designers worked on jet engines. The first jet aircraft to fly, in 1939, was the German Heinkel He 178. In 1943, the first operational jet fighter, the Messerschmitt Me 262, went into service with the German Luftwaffe. Later in the war the British Gloster Meteor entered service, but never saw action – top air speeds for that era went as high as 1,130 km/h (700 mph), with the early July 1944 unofficial record flight of the German Me 163B V18 rocket fighter prototype.[21]

Postwar

[edit]In October 1947, the Bell X-1 was the first aircraft to exceed the speed of sound, flown by Chuck Yeager.[22]

In 1948–49, aircraft transported supplies during the Berlin Blockade. New aircraft types, such as the B-52, were produced during the Cold War.

The first jet airliner, the de Havilland Comet, was introduced in 1952, followed by the Soviet Tupolev Tu-104 in 1956. The Boeing 707, the first widely successful commercial jet, was in commercial service for more than 50 years, from 1958 to 2010. The Boeing 747 was the world's largest passenger aircraft from 1970 until it was surpassed by the Airbus A380 in 2005. The most successful aircraft is the Douglas DC-3 and its military version, the C-47,[23] a medium sized twin engine passenger or transport aircraft that has been in service since 1936 and is still used throughout the world. Some of the hundreds of versions found other purposes, like the AC-47, a Vietnam War era gunship, which is still used in the Colombian Air Force.[24]

Types

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2024) |

Airplane/aeroplane

[edit]

An airplane (spelled aeroplane in British English and shortened to plane) is a powered fixed-wing aircraft propelled by thrust from a jet engine or propeller. Planes come in many sizes, shapes, and wing configurations. Uses include recreation, transportation of goods and people, military, and research.

Seaplane

[edit]A seaplane (hydroplane) is capable of taking off and landing (alighting) on water. Seaplanes that can also operate from dry land are a subclass called amphibian aircraft.[25] Seaplanes and amphibians divide into two categories: float planes and flying boats.

- A float plane is similar to a land-based airplane. The fuselage is not specialized. The wheels are replaced/enveloped by floats, allowing the craft to make remain afloat for water landings.

- A flying boat is a seaplane with a watertight hull for the lower (ventral) areas of its fuselage. The fuselage lands and then rests directly on the water's surface, held afloat by the hull. It does not need additional floats for buoyancy, although small underwing floats or fuselage-mounted sponsons may be used to stabilize it. Large seaplanes are usually flying boats, embodying most classic amphibian aircraft designs.

Powered gliders

[edit]Many forms of glider may include a small power plant. These include:

- Motor glider – a conventional glider or sailplane with an auxiliary power plant that may be used when in flight to increase performance.[26]

- Powered hang glider – a hang glider with a power plant added.

- Powered parachute – a paraglider type of parachute with an integrated air frame, seat, undercarriage and power plant hung beneath.[27]

- Powered paraglider or paramotor – a paraglider with a power plant suspended behind the pilot.[28]

Ground effect vehicle

[edit]A ground effect vehicle (GEV) flies close to the terrain, making use of the ground effect – the interaction between the wings and the surface. Some GEVs are able to fly higher out of ground effect (OGE) when required – these are classed as powered fixed-wing aircraft.[29]

Glider

[edit]

A glider is a heavier-than-air craft whose free flight does not require an engine. A sailplane is a fixed-wing glider designed for soaring – gaining height using updrafts of air and to fly for long periods.

Gliders are mainly used for recreation but have found use for purposes such as aerodynamics research, warfare and spacecraft recovery.

Motor gliders are equipped with a limited propulsion system for takeoff, or to extend flight duration.

As is the case with planes, gliders come in diverse forms with varied wings, aerodynamic efficiency, pilot location, and controls.

Large gliders are most commonly born aloft by a tow-plane or by a winch. Military gliders have been used in combat to deliver troops and equipment, while specialized gliders have been used in atmospheric and aerodynamic research. Rocket-powered aircraft and spaceplanes have made unpowered landings similar to a glider.

Gliders and sailplanes that are used for the sport of gliding have high aerodynamic efficiency. The highest lift-to-drag ratio is 70:1, though 50:1 is common. After take-off, further altitude can be gained through the skillful exploitation of rising air. Flights of thousands of kilometers at average speeds over 200 km/h have been achieved.

One small-scale example of a glider is the paper airplane. An ordinary sheet of paper can be folded into an aerodynamic shape fairly easily; its low mass relative to its surface area reduces the required lift for flight, allowing it to glide some distance.

Gliders and sailplanes share many design elements and aerodynamic principles with powered aircraft. For example, the Horten H.IV was a tailless flying wing glider, and the delta-winged Space Shuttle orbiter glided during its descent phase. Many gliders adopt similar control surfaces and instruments as airplanes.

Types

[edit]The main application of modern glider aircraft is sport and recreation.

Sailplane

[edit]Gliders were developed in the 1920s for recreational purposes. As pilots began to understand how to use rising air, sailplane gliders were developed with a high lift-to-drag ratio. These allowed the craft to glide to the next source of "lift", increasing their range. This gave rise to the popular sport of gliding.

Early gliders were built mainly of wood and metal, later replaced by composite materials incorporating glass, carbon or aramid fibers. To minimize drag, these types have a streamlined fuselage and long narrow wings incorporating a high aspect ratio. Single-seat and two-seat gliders are available.

Initially, training was done by short "hops" in primary gliders, which have no cockpit and minimal instruments.[30] Since shortly after World War II, training is done in two-seat dual control gliders, but high-performance two-seaters can make long flights. Originally skids were used for landing, later replaced by wheels, often retractable. Gliders known as motor gliders are designed for unpowered flight, but can deploy piston, rotary, jet or electric engines.[31] Gliders are classified by the FAI for competitions into glider competition classes mainly on the basis of wingspan and flaps.

A class of ultralight sailplanes, including some known as microlift gliders and some known as airchairs, has been defined by the FAI based on weight. They are light enough to be transported easily, and can be flown without licensing in some countries. Ultralight gliders have performance similar to hang gliders, but offer some crash safety as the pilot can strap into an upright seat within a deform-able structure. Landing is usually on one or two wheels which distinguishes these craft from hang gliders. Most are built by individual designers and hobbyists.

Military gliders

[edit]

Military gliders were used during World War II for carrying troops (glider infantry) and heavy equipment to combat zones. The gliders were towed into the air and most of the way to their target by transport planes, e.g. C-47 Dakota, or by one-time bombers that had been relegated to secondary activities, e.g. Short Stirling. The advantage over paratroopers were that heavy equipment could be landed and that troops were quickly assembled rather than dispersed over a parachute drop zone. The gliders were treated as disposable, constructed from inexpensive materials such as wood, though a few were re-used. By the time of the Korean War, transport aircraft had become larger and more efficient so that even light tanks could be dropped by parachute, obsoleting gliders.

Research gliders

[edit]Even after the development of powered aircraft, gliders continued to be used for aviation research. The NASA Paresev Rogallo flexible wing was developed to investigate alternative methods of recovering spacecraft. Although this application was abandoned, publicity inspired hobbyists to adapt the flexible-wing airfoil for hang gliders.

Initial research into many types of fixed-wing craft, including flying wings and lifting bodies was also carried out using unpowered prototypes.

Hang glider

[edit]

A hang glider is a glider aircraft in which the pilot is suspended in a harness suspended from the air frame, and exercises control by shifting body weight in opposition to a control frame. Hang gliders are typically made of an aluminum alloy or composite-framed fabric wing. Pilots can soar for hours, gain thousands of meters of altitude in thermal updrafts, perform aerobatics, and glide cross-country for hundreds of kilometers.

Paraglider

[edit]A paraglider is a lightweight, free-flying, foot-launched glider with no rigid body.[32] The pilot is suspended in a harness below a hollow fabric wing whose shape is formed by its suspension lines. Air entering vents in the front of the wing and the aerodynamic forces of the air flowing over the outside power the craft. Paragliding is most often a recreational activity.

Unmanned gliders

[edit]A paper plane is a toy aircraft (usually a glider) made out of paper or paperboard.

Model glider aircraft are models of aircraft using lightweight materials such as polystyrene and balsa wood. Designs range from simple glider aircraft to accurate scale models, some of which can be very large.

Glide bombs are bombs with aerodynamic surfaces to allow a gliding flight path rather than a ballistic one. This enables stand-off aircraft to attack a target from a distance.

Kite

[edit]

A kite is a tethered aircraft held aloft by wind that blows over its wing(s).[33] High pressure below the wing deflects the airflow downwards. This deflection generates horizontal drag in the direction of the wind. The resultant force vector from the lift and drag force components is opposed by the tension of the tether.

Kites are mostly flown for recreational purposes, but have many other uses. Early pioneers such as the Wright brothers and J.W. Dunne sometimes flew an aircraft as a kite in order to confirm its flight characteristics, before adding an engine and flight controls.

Applications

[edit]

Military

[edit]Kites have been used for signaling, for delivery of munitions, and for observation, by lifting an observer above the field of battle, and by using kite aerial photography.

Science and meteorology

[edit]Kites have been used for scientific purposes, such as Benjamin Franklin's famous experiment proving that lightning is electricity. Kites were the precursors to the traditional aircraft, and were instrumental in the development of early flying craft. Alexander Graham Bell experimented with large man-lifting kites, as did the Wright brothers and Lawrence Hargrave. Kites had a historical role in lifting scientific instruments to measure atmospheric conditions for weather forecasting.

Radio aerials and light beacons

[edit]Kites can be used to carry radio antennas. This method was used for the reception station of the first transatlantic transmission by Marconi. Captive balloons may be more convenient for such experiments, because kite-carried antennas require strong wind, which may be not always available with heavy equipment and a ground conductor.

Kites can be used to carry light sources such as light sticks or battery-powered lights.

Kite traction

[edit]

Kites can be used to pull people and vehicles downwind. Efficient foil-type kites such as power kites can also be used to sail upwind under the same principles as used by other sailing craft, provided that lateral forces on the ground or in the water are redirected as with the keels, center boards, wheels and ice blades of traditional sailing craft. In the last two decades, kite sailing sports have become popular, such as kite buggying, kite landboarding, kite boating and kite surfing. Snow kiting is also popular.

Kite sailing opens several possibilities not available in traditional sailing:

- Wind speeds are greater at higher altitudes

- Kites may be maneuvered dynamically, which dramatically increases the available force

- Mechanical structures are not needed to withstand bending forces; vehicles/hulls can be light or eliminated.

Power generation

[edit]Research and development projects investigate kites for harnessing high altitude wind currents for electricity generation.[34]

Cultural uses

[edit]Kite festivals are a popular form of entertainment throughout the world. They include local events, traditional festivals and major international festivals.

Designs

[edit]

- Bermuda kite

- Bowed kite, e.g. Rokkaku

- Cellular or box kite

- Chapi-chapi

- Delta kite

- Foil, parafoil or bow kite

- Malay kite see also wau bulan

- Tetrahedral kite

Types

[edit]Characteristics

[edit]

Air frame

[edit]The structural element of a fixed-wing aircraft is the air frame. It varies according to the aircraft's type, purpose, and technology. Early airframes were made of wood with fabric wing surfaces, When engines became available for powered flight, their mounts were made of metal. As speeds increased metal became more common until by the end of World War II, all-metal (and glass) aircraft were common. In modern times, composite materials became more common.

Typical structural elements include:

- One or more mostly horizontal wings, often with an airfoil cross-section. The wing deflects air downward as the aircraft moves forward, generating lifting force to support it in flight. The wing also provides lateral stability to stop the aircraft level in steady flight. Other roles are to hold the fuel and mount the engines.

- A fuselage, typically a long, thin body, usually with tapered or rounded ends to make its shape aerodynamically slippery. The fuselage joins the other parts of the air frame and contains the payload, and flight systems.

- A vertical stabilizer or fin is a rigid surface mounted at the rear of the plane and typically protruding above it. The fin stabilizes the plane's yaw (turn left or right) and mounts the rudder which controls its rotation along that axis.

- A horizontal stabilizer, usually mounted at the tail near the vertical stabilizer. The horizontal stabilizer is used to stabilize the plane's pitch (tilt up or down) and mounts the elevators that provide pitch control.

- Landing gear, a set of wheels, skids, or floats that support the plane while it is not in flight. On seaplanes, the bottom of the fuselage or floats (pontoons) support it while on the water. On some planes, the landing gear retracts during the flight to reduce drag.

Wings

[edit]The wings of a fixed-wing aircraft are static planes extending to either side of the aircraft. When the aircraft travels forwards, air flows over the wings that are shaped to create lift.

Structure

[edit]Kites and some lightweight gliders and airplanes have flexible wing surfaces that are stretched across a frame and made rigid by the lift forces exerted by the airflow over them. Larger aircraft have rigid wing surfaces.

Whether flexible or rigid, most wings have a strong frame to give them shape and to transfer lift from the wing surface to the rest of the aircraft. The main structural elements are one or more spars running from root to tip, and ribs running from the leading (front) to the trailing (rear) edge.

Early airplane engines had little power and light weight was critical. Also, early airfoil sections were thin, and could not support a strong frame. Until the 1930s, most wings were so fragile that external bracing struts and wires were added. As engine power increased, wings could be made heavy and strong enough that bracing was unnecessary. Such an unbraced wing is called a cantilever wing.

Configuration

[edit]

The number and shape of wings vary widely. Some designs blend the wing with the fuselage, while left and right wings separated by the fuselage are more common.

Occasionally more wings have been used, such as the three-winged triplane from World War I. Four-winged quadruplanes and other multiplane designs have had little success.

Most planes are monoplanes, with one or two parallel wings. Biplanes and triplanes stack one wing above the other. Tandem wings place one wing behind the other, possibly joined at the tips. When the available engine power increased during the 1920s and 1930s and bracing was no longer needed, the unbraced or cantilever monoplane became the most common form.

The planform is the shape when seen from above/below. To be aerodynamically efficient, wings are straight with a long span, but a short chord (high aspect ratio). To be structurally efficient, and hence lightweight, wingspan must be as small as possible, but offer enough area to provide lift.

To travel at transonic speeds, variable geometry wings change orientation, angling backward to reduce drag from supersonic shock waves. The variable-sweep wing transforms between an efficient straight configuration for takeoff and landing, to a low-drag swept configuration for high-speed flight. Other forms of variable planform have been flown, but none have gone beyond the research stage. The swept wing is a straight wing swept backward or forwards.

The delta wing is a triangular shape that serves various purposes. As a flexible Rogallo wing, it allows a stable shape under aerodynamic forces, and is often used for kites and other ultralight craft. It is supersonic capable, combining high strength with low drag.

Wings are typically hollow, also serving as fuel tanks. They are equipped with flaps, which allow the wing to increase/decrease drag/lift, for take-off and landing, and acting in opposition, to change direction.

Fuselage

[edit]The fuselage is typically long and thin, usually with tapered or rounded ends to make its shape aerodynamically smooth. Most fixed-wing aircraft have a single fuselage. Others may have multiple fuselages, or the fuselage may be fitted with booms on either side of the tail to allow the extreme rear of the fuselage to be utilized.

The fuselage typically carries the flight crew, passengers, cargo, and sometimes fuel and engine(s). Gliders typically omit fuel and engines, although some variations such as motor gliders and rocket gliders have them for temporary or optional use.

Pilots of manned commercial fixed-wing aircraft control them from inside a cockpit within the fuselage, typically located at the front/top, equipped with controls, windows, and instruments, separated from passengers by a secure door. In small aircraft, the passengers typically sit behind the pilot(s) in the cabin, Occasionally, a passenger may sit beside or in front of the pilot. Larger passenger aircraft have a separate passenger cabin or occasionally cabins that are physically separated from the cockpit.

Aircraft often have two or more pilots, with one in overall command (the "pilot") and one or more "co-pilots". On larger aircraft a navigator is typically also seated in the cockpit as well. Some military or specialized aircraft may have other flight crew members in the cockpit as well.

Wings vs. bodies

[edit]Flying wing

[edit]

A flying wing is a tailless aircraft that has no distinct fuselage, housing the crew, payload, and equipment inside.[35]: 224

The flying wing configuration was studied extensively in the 1930s and 1940s, notably by Jack Northrop and Cheston L. Eshelman in the United States, and Alexander Lippisch and the Horten brothers in Germany. After the war, numerous experimental designs were based on the flying wing concept. General interest continued into the 1950s, but designs did not offer a great advantage in range and presented technical problems. The flying wing is most practical for designs in the slow-to-medium speed range, and drew continual interest as a tactical airlifter design.

Interest in flying wings reemerged in the 1980s due to their potentially low radar cross-sections. Stealth technology relies on shapes that reflect radar waves only in certain directions, thus making it harder to detect. This approach eventually led to the Northrop B-2 Spirit stealth bomber (pictured). The flying wing's aerodynamics are not the primary concern. Computer-controlled fly-by-wire systems compensated for many of the aerodynamic drawbacks, enabling an efficient and stable long-range aircraft.

Blended wing body

[edit]

Blended wing body aircraft have a flattened airfoil-shaped body, which produces most of the lift to keep itself aloft, and distinct and separate wing structures, though the wings are blended with the body.

Blended wing bodied aircraft incorporate design features from both fuselage and flying wing designs. The purported advantages of the blended wing body approach are efficient, high-lift wings and a wide, airfoil-shaped body. This enables the entire craft to contribute to lift generation with potentially increased fuel economy.

Lifting body

[edit]

A lifting body is a configuration in which the body produces lift. In contrast to a flying wing, which is a wing with minimal or no conventional fuselage, a lifting body can be thought of as a fuselage with little or no conventional wing. Whereas a flying wing seeks to maximize cruise efficiency at subsonic speeds by eliminating non-lifting surfaces, lifting bodies generally minimize the drag and structure of a wing for subsonic, supersonic, and hypersonic flight, or, spacecraft re-entry. All of these flight regimes pose challenges for flight stability.

Lifting bodies were a major area of research in the 1960s and 1970s as a means to build small and lightweight crewed spacecraft. The US built lifting body rocket planes to test the concept, as well as several rocket-launched re-entry vehicles. Interest waned as the US Air Force lost interest in the crewed mission, and major development ended during the Space Shuttle design process when it became clear that highly shaped fuselages made it difficult to fit fuel tanks.

Empennage and foreplane

[edit]The classic airfoil section wing is unstable in flight. Flexible-wing planes often rely on an anchor line or the weight of a pilot hanging beneath to maintain the correct attitude. Some free-flying types use an adapted airfoil that is stable, or other mechanisms including electronic artificial stability.

In order to achieve trim, stability, and control, most fixed-wing types have an empennage comprising a fin and rudder that act horizontally, and a tailplane and elevator that act vertically. This is so common that it is known as the conventional layout. Sometimes two or more fins are spaced out along the tailplane.

Some types have a horizontal "canard" foreplane ahead of the main wing, instead of behind it.[35]: 86 [36][37] This foreplane may contribute to the trim, stability or control of the aircraft, or to several of these.

Aircraft controls

[edit]Kite control

[edit]Kites are controlled by one or more tethers.

Free-flying aircraft controls

[edit]Gliders and airplanes have sophisticated control systems, especially if they are piloted.

The controls allow the pilot to direct the aircraft in the air and on the ground. Typically these are:

- The yoke or joystick controls rotation of the plane about the pitch and roll axes. A yoke resembles a steering wheel. The pilot can pitch the plane down by pushing on the yoke or joystick, and pitch the plane up by pulling on it. Rolling the plane is accomplished by turning the yoke in the direction of the desired roll, or by tilting the joystick in that direction.

- Rudder pedals control rotation of the plane about the yaw axis. Two pedals pivot so that when one is pressed forward the other moves backward, and vice versa. The pilot presses on the right rudder pedal to make the plane yaw to the right, and pushes on the left pedal to make it yaw to the left. The rudder is used mainly to balance the plane in turns, or to compensate for winds or other effects that push the plane about the yaw axis.

- On powered types, an engine stop control ("fuel cutoff", for example) and, usually, a throttle or thrust lever and other controls, such as a fuel-mixture control (to compensate for air density changes with altitude change).

Other common controls include:

- Flap levers, which are used to control the deflection position of flaps on the wings.

- Spoiler levers, which are used to control the position of spoilers on the wings, and to arm their automatic deployment in planes designed to deploy them upon landing. The spoilers reduce lift for landing.

- Trim controls, which usually take the form of knobs or wheels and are used to adjust pitch, roll, or yaw trim. These are often connected to small airfoils on the trailing edge of the control surfaces and are called "trim tabs". Trim is used to reduce the amount of pressure on the control forces needed to maintain a steady course.

- On wheeled types, brakes are used to slow and stop the plane on the ground, and sometimes for turns on the ground.

A craft may have two pilot seats with dual controls, allowing two to take turns.

The control system may allow full or partial automation, such as an autopilot, a wing leveler, or a flight management system. An unmanned aircraft has no pilot and is controlled remotely or via gyroscopes, computers/sensors or other forms of autonomous control.

Cockpit instrumentation

[edit]On manned fixed-wing aircraft, instruments provide information to the pilots, including flight, engines, navigation, communications, and other aircraft systems that may be installed.

Top row (left to right): airspeed indicator, attitude indicator, altimeter.

Bottom row (left to right): turn coordinator, heading indicator, vertical speed indicator.

The six basic instruments, sometimes referred to as the six pack, are:[38]

- The airspeed indicator (ASI) shows the speed at which the plane is moving through the air.

- The attitude indicator (AI), sometimes called the artificial horizon, indicates the exact orientation of the aircraft about its pitch and roll axes.

- The altimeter indicates the altitude or height of the plane above mean sea level (AMSL).

- The vertical speed indicator (VSI), or variometer, shows the rate at which the plane is climbing or descending.

- The heading indicator (HI), sometimes called the directional gyro (DG), shows the magnetic compass orientation of the fuselage. The direction is affected by wind conditions and magnetic declination.

- The turn coordinator (TC), or turn and bank indicator, helps the pilot to control the plane in a coordinated attitude while turning.

Other cockpit instruments include:

- A two-way radio, to enable communications with other planes and with air traffic control.

- A horizontal situation indicator (HSI) indicates the position and movement of the plane as seen from above with respect to the ground, including course/heading and other information.

- Instruments showing the status of the plane's engines (operating speed, thrust, temperature, and other variables).

- Combined display systems such as primary flight displays or navigation aids.

- Information displays such as onboard weather radar displays.

- A radio direction finder (RDF), to indicate the direction to one or more radio beacons, which can be used to determine the plane's position.

- A satellite navigation (satnav) system, to provide an accurate position.

Some or all of these instruments may appear on a computer display and be operated with touches, ala a phone.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- In 1903, when the Wright brothers used the word, "aeroplane" (a British English term that can also mean airplane in American English) meant wing, not the whole aircraft. See text of their patent. Patent 821,393 – Wright brothers' patent for "Flying Machine"

Citations

[edit]- ^ "Drachen Foundation Journal Fall 2002, page 18. Two lines of evidence: analysis of leaf kiting and some cave drawings" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ^ a b Needham, Volume 4, Part 1, 127.

- ^ a b Anon. "Kite History: A Simple History of Kiting". G-Kites. Archived from the original on 29 May 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ Aulus Gellius, "Attic Nights", Book X, 12.9 at LacusCurtius

- ^ Archytas of Tarentum, Technology Museum of Thessaloniki, Macedonia, Greece. Tmth.edu.gr.

- ^ Modern rocketry[dead link]. Pressconnects.com.

- ^ Automata history Archived 15 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Automata.co.uk.

- ^ White, Lynn. "Eilmer of Malmesbury, an Eleventh Century Aviator: A Case Study of Technological Innovation, Its Context and Tradition." Technology and Culture, Volume 2, Issue 2, 1961, pp. 97–111 (97–99 resp. 100–101).

- ^ "Aviation History". Archived from the original on 13 April 2009. Retrieved 26 July 2009.

In 1799 he set forth for the first time in history the concept of the modern aeroplane. Cayley had identified the drag vector (parallel to the flow) and the lift vector (perpendicular to the flow).

- ^ "Sir George Cayley (British Inventor and Scientist)". Britannica. Archived from the original on 11 March 2009. Retrieved 26 July 2009.

English pioneer of aerial navigation and aeronautical engineering and designer of the first successful glider to carry a human being aloft. Cayley established the modern configuration of an aeroplane as a fixed-wing flying machine with separate systems for lift, propulsion, and control as early as 1799.

- ^ "Cayley, Sir George: Encyclopædia Britannica 2007." Archived 11 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 25 August 2007.

- ^ Gibbs-Smith, Charles Harvard (2003). Aviation : an historical survey from its origins to the end of the Second World War. London: Science Museum. ISBN 1-900747-52-9. OCLC 52566384.

- ^ Harwood, Craig; Fogel, Gary (2012). Quest for Flight: John J. Montgomery and the Dawn of Aviation in the West. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806142647.

- ^ Inglis, Amirah. "Hargrave, Lawrence (1850–1915)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 9. Melbourne University Press. Archived from the original on 29 December 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ Beril, Becker (1967). Dreams and Realities of the Conquest of the Skies. New York: Atheneum. pp. 124–125

- ^ FAI News: 100 Years Ago, the Dream of Icarus Became Reality Archived 13 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine posted 17 December 2003. (The 1903 flights are not listed in the official FAI flight records, however, because the organization and its predecessors did not yet exist.) Retrieved 5 January 2007.

- ^ Jones, Ernest. "Santos Dumont in France 1906–1916: The Very Earliest Early Birds." Archived 16 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine earlyaviators.com, 25 December 2006. Retrieved 17 August 2009.

- ^ Les vols du 14bis relatés au fil des éditions du journal l'illustration de 1906. The wording is: "cette prouesse est le premier vol au monde homologué par l'Aéro-Club de France et la toute jeune Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI)." (This achievement is the first flight in the world to be recognized by the France Air Club and by the new International Aeronautical Federation (FAI).)

- ^ Crouch, Tom (1982). Bleriot XI, The Story of a Classic Aircraft. Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 21 and 22. ISBN 0-87474-345-1.

- ^ "Ace of Aces: How the Red Baron Became WWI's Most Legendary Fighter Pilot". HISTORY. 1 September 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2025.

- ^ de Bie, Rob. "Me 163B Komet – Me 163 Production – Me 163B: Werknummern list." Archived 22 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine robdebie.home. Retrieved: 28 July 2013.

- ^ NASA Armstrong Fact Sheet: First Generation X-1 Archived 13 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine, 28 February 2014

- ^ "Douglas DC-3 | National Air and Space Museum".

- ^ "There's One Place in the World Where AC-47 Spooky Gunships Still Fly". 12 February 2021.

- ^ de Saint-Exupery, A. (1940). "Wind, Sand and Stars" p33, Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc.

- ^ "3. Gliding, chapter 1: General Rules and Definitions". FAI Sporting Code. Archived from the original on 7 October 2007. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ Code of Federal Regulations (U.S.). "14 CFR 1.1 - General definitions". www.ecfr.gov.

- ^ Goin, Jeff (2006). Dennis Pagen (ed.). The Powered Paragliding Bible. Airhead Creations. p. 253. ISBN 0-9770966-0-2.

- ^ Michael Halloran and Sean O'Meara, Wing in Ground Effect Craft Review, DSTO, Australia "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), p51. Notes an agreement between ICAO and IMO that WIGs come under the jurisdiction of the International Maritime Organisation although there an exception for craft with a sustained use out of ground effect (OGE) to be considered as aircraft. - ^ Schweizer, Paul A: Wings Like Eagles, The Story of Soaring in the United States, pages 14–22. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1988. ISBN 0-87474-828-3

- ^ "Definition of gliders used for sporting purposes in FAI Sporting Code". Archived from the original on 3 September 2009.

- ^ Whittall, Noel (2002). Paragliding: The Complete Guide. Airlife Pub. ISBN 1-84037-016-5.

- ^ "Beginner's Guide to Aeronautics" Archived 25 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine, NASA (11 July 2008).

- ^ Joseph Faust. "Kite Energy Systems". Energykitesystems.net. Archived from the original on 24 August 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ a b Crane, Dale: Dictionary of Aeronautical Terms, third edition. Aviation Supplies & Academics, 1997. ISBN 1-56027-287-2

- ^ Aviation Publishers Co. Limited, From the Ground Up, page 10 (27th revised edition) ISBN 0-9690054-9-0

- ^ Federal Aviation Administration (August 2008). "Title 14: Aeronautics and Space – PART 1—DEFINITIONS AND ABBREVIATIONS". Archived from the original on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ^ "Six Pack – The Primary Flight Instruments". LearnToFly.ca. 13 March 2010. Archived from the original on 19 March 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

Bibliography

[edit]- Blatner, David. The Flying Book: Everything You've Ever Wondered About Flying on Airplanes. ISBN 0-8027-7691-4

External links

[edit]Fixed-wing aircraft

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Principles

A fixed-wing aircraft is a heavier-than-air flying vehicle that uses fixed, rigid wings to generate aerodynamic lift primarily through forward motion relative to the surrounding air, distinguishing it from vehicles employing flapping wings like birds or rotating wings like helicopters.[2] This category encompasses powered airplanes, which are engine-driven and supported in flight by the dynamic reaction of air against their wings; unpowered gliders, which rely on initial launch energy and atmospheric conditions for sustained flight via the same lifting surfaces; and tethered kites, which maintain altitude through tension in their control lines while generating lift similarly to free-flying fixed-wing craft.[1][2][8] The fundamental principles governing lift in fixed-wing aircraft combine Bernoulli's principle, which explains pressure differences arising from variations in airflow speed over the wing surfaces, and Newton's third law, which accounts for the reactive force from the wing's deflection of oncoming air downward.[9] Bernoulli's principle posits that faster-moving air over the curved upper surface of a typical airfoil creates lower pressure compared to the slower air beneath, producing an upward net force; simultaneously, the wing imparts downward momentum to the air, resulting in an equal and opposite upward lift on the aircraft per Newton's third law.[10] These effects are interdependent, with the airfoil shape—often cambered and asymmetric—optimizing airflow to maximize lift while minimizing drag.[9] The angle of attack, defined as the angle between the wing's chord line and the relative wind direction, critically influences the lift coefficient , which quantifies the airfoil's efficiency in generating lift at a given condition.[11] Lift force is mathematically expressed as: where is air density, is the aircraft's velocity relative to the air, is the wing reference area, and increases with angle of attack up to a maximum value.[12] Increasing the angle of attack enhances lift by altering airflow curvature, but beyond a critical angle—typically 15–20 degrees for conventional airfoils—airflow separates from the upper surface, causing a phenomenon known as stall.[11] Stall results in a abrupt reduction in and lift, often accompanied by increased drag and potential loss of control, as the airflow separates from the upper surface due to exceeding the critical angle of attack, leading to turbulent wake formation behind the wing.[13] The basic flight envelope delineates the safe operational limits for a fixed-wing aircraft, bounded by the minimum speed required to generate sufficient lift for takeoff or level flight—known as stall speed—and maximum speeds constrained by structural integrity, such as the never-exceed speed (V_NE) to prevent aerodynamic or material failure.[14] This envelope also considers load factors, where the aircraft must withstand forces from maneuvers without exceeding design limits, ensuring stability across altitudes and configurations; for instance, a typical light airplane's stall speed might be around 50 knots at sea level, while structural limits cap speeds at 150–200 knots depending on the model.[11]Comparison to Rotary-Wing and Other Aircraft

Fixed-wing aircraft generate lift through the aerodynamic interaction of air flowing over stationary wings, requiring forward motion to maintain flight, whereas rotary-wing aircraft, such as helicopters, use rotating blades to produce lift and thrust, enabling vertical takeoff, landing, and hovering without forward speed.[15] This fundamental difference means fixed-wing designs lack the inherent hover capability of rotary-wing systems, which rely on the rotor's autorotation or powered rotation for low-speed operations like search and rescue.[16] Vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) and tiltrotor hybrids represent transitional designs that blend elements of both categories, such as the Harrier Jump Jet, a fixed-wing aircraft that achieves VTOL through vectored thrust from its engine nozzles directed downward for lift during hover and transition.[17] Similarly, the V-22 Osprey employs tiltrotor technology, where proprotors pivot from vertical for helicopter-like operations to horizontal for fixed-wing cruise, offering improved speed and range over pure rotary-wing but with added mechanical complexity compared to conventional fixed-wing efficiency.[18] Despite these bridges, fixed-wing aircraft dominate long-duration missions due to their superior fuel efficiency in sustained forward flight.[16] Ornithopters, which mimic bird or insect flight via flapping wings, provide an experimental contrast to fixed-wing stability, generating both lift and thrust through oscillatory motion but suffering from higher induced drag and lower overall efficiency in scaled-up designs.[19] These rare prototypes, often limited to short flights, lack the aerodynamic predictability of fixed wings, which maintain consistent lift coefficients across a wide speed range, making ornithopters impractical for most operational roles.[20] In opposition to dynamic lift in fixed-wing aircraft, balloons and airships rely on static buoyancy from lighter-than-air gases like helium, providing passive lift without propulsion for altitude control and requiring minimal active maneuvering.[21] This aerostatic principle allows prolonged stationary flight but contrasts sharply with fixed-wing needs for continuous engine power and airflow to sustain dynamic lift and directional control.[22] Key trade-offs highlight fixed-wing advantages in speed and range, with typical cruise velocities of 500-900 km/h enabling efficient long-haul travel, compared to rotary-wing limits around 200-300 km/h due to retreating blade stall and profile drag. However, fixed-wing aircraft exhibit poorer low-speed handling, necessitating runways for takeoff and landing, unlike the vertical agility of rotary or buoyant alternatives.[16]History

Early Concepts and Unpowered Flight

Early concepts of fixed-wing flight drew inspiration from ancient myths and rudimentary devices, reflecting humanity's enduring aspiration to mimic birds. The Greek myth of Daedalus and Icarus, dating back to around 1000 BCE, depicted an engineer crafting wings of feathers and wax to escape captivity, symbolizing early imaginative notions of sustained aerial travel through wing-like structures.[23] Similarly, Chinese inventors developed kites around the 5th century BCE, using fixed bamboo frames covered in silk to create lightweight structures that harnessed wind for lift, laying foundational principles for aerodynamic stability in unpowered flight.[24] The 18th century marked a pivotal shift toward practical experimentation, initially influenced by lighter-than-air devices before emphasis turned to heavier-than-air fixed-wing designs. In 1783, the Montgolfier brothers' hot-air balloon ascents captivated Europe, demonstrating human flight but highlighting limitations in control and direction.[24] By the early 19th century, interest pivoted to winged gliders, with British engineer Sir George Cayley establishing core principles in 1804 through a small model glider featuring a kite-shaped wing, cruciform tail for stability, and adjustable center of gravity via movable ballast.[25] Cayley's work emphasized the separation of lift-generating wings from propulsion and control surfaces, proving that fixed wings could sustain unpowered flight in straight-line glides. This conceptual framework influenced subsequent designs, transitioning from balloon-dominated aerial pursuits to aerodynamic fixed-wing experiments by the 1850s. The late 19th century saw significant advancements in human-carrying gliders, driven by systematic testing and iterative improvements. German aviation pioneer Otto Lilienthal conducted over 2,000 flights in his hang gliders during the 1890s, starting with his 1891 Derwisch model and refining designs like the 1894 Normalseglider, a monoplane with a 6.7-meter wingspan that allowed controlled glides of up to 250 meters from hillsides.[26] Lilienthal's approach relied on body-weight shifting for pitch and roll control, providing empirical data on cambered wings and balance that advanced fixed-wing aerodynamics.[27] Parallel developments in kite technology evolved man-lifting variants for observation, with fixed-surface designs achieving heights of 400 meters by the late 19th century, demonstrating inherent stability but requiring tethering for safety.[28] Despite these milestones, early unpowered fixed-wing efforts faced inherent challenges stemming from the absence of onboard propulsion. Gliders depended entirely on external forces like gravity from elevated launches or wind gradients, resulting in short-duration flights typically limited to downhill trajectories of mere hundreds of meters.[29] Control remained precarious without powered thrust for recovery from stalls or gusts, often leading to crashes and underscoring the need for precise weight distribution and surface shaping to maintain lift-to-drag ratios. These limitations confined experiments to favorable terrain and weather, hindering broader adoption until propulsion solutions emerged.Powered Flight and Early Aviation

The invention of powered fixed-wing flight is credited to Orville and Wilbur Wright, who achieved the first sustained, controlled, and manned heavier-than-air flight on December 17, 1903, near Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. Their aircraft, the Wright Flyer, was a canard biplane constructed primarily of spruce wood and muslin fabric, featuring a wingspan of 40 feet 4 inches and employing wing warping—a system of cables that twisted the wings to enable roll control, building on their earlier glider experiments. The Flyer's inaugural flight lasted 12 seconds and covered 120 feet, with subsequent attempts that day reaching up to 59 seconds and 852 feet, demonstrating the feasibility of powered aerial navigation.[3][30][30] Central to this breakthrough was the Wrights' development of a lightweight 12-horsepower inline four-cylinder gasoline engine, weighing approximately 180 pounds, which drove two contra-rotating pusher propellers via a chain-and-sprocket transmission. This engine represented a pivotal innovation, providing sufficient thrust for takeoff and sustained flight while overcoming the limitations of earlier power sources, such as steam engines attempted by pioneers like Clément Ader in 1890 or rubber-band propulsion used in 19th-century model aircraft that offered only brief hops. The gasoline engine's reliability and power-to-weight ratio enabled the Flyer to achieve a takeoff speed of about 30 miles per hour, marking the transition from unpowered gliders to viable powered aircraft.[31][24][32] In Europe, rapid advancements followed, with Brazilian inventor Alberto Santos-Dumont achieving the first public powered flight on October 23, 1906, in his boxy biplane known as the 14-bis, covering 60 meters at an altitude of about 2 meters near Paris; a subsequent flight on November 12 extended to 220 meters in 21.5 seconds. French aviator Louis Blériot further advanced the field with his monoplane design, the Blériot XI, powered by a 25-horsepower rotary engine, which on July 25, 1909, completed the first aerial crossing of the English Channel from Calais, France, to Dover, England, in approximately 38 minutes over 23 miles. These feats spurred international interest and competition.[33][34] By the early 1910s, aviation records reflected growing capabilities, with speeds reaching up to 106 kilometers per hour, as set by Léon Morane in a Blériot monoplane in 1910, and altitudes climbing to around 1,900 meters, exemplified by Walter Brookins' 6,234-foot flight in a Wright biplane that same year. Practical applications emerged, including the inauguration of airmail service in 1911, when French pilot Henri Pequet carried approximately 6,500 letters over 8 kilometers from Allahabad to Naini, India, aboard a Humber-Sommer biplane.[35][35][36] Regulatory frameworks also began to formalize, with the Aéro-Club de France issuing the world's first pilot licenses on January 7, 1909, retroactively certifying pioneers like Blériot to ensure safety amid increasing aerial activity.[37]World Wars and Interwar Period

The period encompassing World War I (1914–1918), the interwar years (1919–1939), and World War II (1939–1945) marked a transformative era for fixed-wing aircraft, driven primarily by military demands that spurred mass production and technological innovation, while laying the groundwork for nascent commercial aviation. In World War I, aircraft transitioned from fragile reconnaissance platforms to specialized fighters and bombers, with total production exceeding 100,000 units across all major powers, enabling widespread tactical employment on the Western Front. The British Sopwith Camel, introduced in 1917, exemplified agile fighter design with a maximum speed of approximately 185 km/h and rotary engine powering twin machine guns, crediting it with over 1,200 aerial victories.[38] German bombers like the Gotha G.IV, operational from 1917, featured twin engines and a bomb load of up to 500 kg, conducting strategic raids on London that highlighted the shift toward offensive bombing capabilities. The interwar "Golden Age" saw aviation's commercialization accelerate, fueled by surplus military aircraft and pioneering flights that captured public imagination. Commercial airlines emerged in the 1920s, with precursors to the Douglas DC-3—such as the Ford Trimotor (1926)—enabling reliable passenger transport over short routes, carrying up to 12 passengers at speeds around 200 km/h. Charles Lindbergh's solo nonstop transatlantic flight from New York to Paris on May 20–21, 1927, in the Ryan NYP Spirit of St. Louis, covering 5,800 km in 33.5 hours, not only won a $25,000 prize but symbolized aviation's potential for long-distance travel.[39] Technological leaps during this time included the replacement of biplanes with monoplanes for improved aerodynamics and speed, the adoption of all-metal construction pioneered by designers like Hugo Junkers in the 1910s and refined in the 1930s, and the integration of superchargers in engines to maintain power at higher altitudes, as seen in aircraft like the Boeing P-26 Peashooter (1932). World War II amplified these advancements on an industrial scale, with global aircraft production surpassing 300,000 units, dominated by Allied output that overwhelmed Axis capabilities. The British Supermarine Spitfire, entering service in 1938, achieved speeds up to 595 km/h with its elliptical wings and Rolls-Royce Merlin engine, proving pivotal in the Battle of Britain by intercepting Luftwaffe bombers.[40] American heavy bombers like the Boeing B-29 Superfortress, introduced in 1944, featured pressurized cabins and a range exceeding 5,000 km, enabling high-altitude raids over Japan with radar-guided bombing systems. Radar integration transformed aircraft operations, with systems like the British Chain Home providing early warning and airborne sets such as the AI Mk. IV enabling nighttime interceptions by night fighters.[41] Civilian aviation benefited indirectly through the era's innovations, particularly in the 1930s when air races like the Schneider Trophy (1927–1931) pushed speed records to over 650 km/h and influenced monoplane designs, while airmail expansion established transoceanic routes, such as the U.S. Pan American Clipper service from San Francisco to Manila starting in 1935, carrying approximately 830 kg of mail across the Pacific. These developments not only enhanced military efficacy but also seeded the postwar commercial boom by demonstrating reliable long-range flight.Postwar and Modern Developments

Following World War II, fixed-wing aircraft entered the jet age, with the Messerschmitt Me 262 recognized as the first operational jet fighter, achieving service in 1944 and demonstrating turbojet propulsion in combat. Postwar advancements accelerated this transition, as Allied nations captured German technology and developed their own jets. The Boeing 707, introduced in 1958 as the first successful commercial jet airliner, revolutionized passenger travel with its four turbofan engines enabling transatlantic flights at speeds up to 600 mph, carrying up to 189 passengers.[42] This model set the standard for the jet age through the 1960s, with over 1,000 units produced and influencing global air transport economics by reducing flight times dramatically.[43] Supersonic capabilities emerged as a key postwar milestone, exemplified by the Anglo-French Concorde, which entered commercial service in 1976 and achieved cruise speeds exceeding Mach 2 (approximately 1,354 mph), allowing New York to London flights in under three hours.[44] Military applications pushed boundaries further, with the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird entering service in 1964 and capable of sustained speeds over Mach 3 (more than 2,200 mph) at altitudes above 85,000 feet, providing reconnaissance during the Cold War without interception.[45] Hybrid spaceplane designs like the North American X-15, first flown in 1959, blended fixed-wing aerodynamics with rocket propulsion, reaching speeds of Mach 6.7 (about 4,520 mph) and altitudes over 350,000 feet, informing later orbital vehicle technologies.[46] The 1970s brought a materials revolution, with composite structures reducing aircraft weight and improving efficiency. The Boeing 787 Dreamliner, entering service in 2011, incorporates 50% composites by weight in its airframe, achieving a 20% reduction in fuel consumption compared to previous generations through lighter construction and enhanced aerodynamics.[47] Concurrently, digital fly-by-wire systems transformed flight controls by replacing mechanical linkages with electronic signals, first fully implemented in the Airbus A320, certified in 1988, which enhanced precision, reduced pilot workload, and improved safety via envelope protection features.[48] Unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) integration advanced fixed-wing designs post-2000, with the MQ-9 Reaper, introduced in 2007, serving as a multi-mission platform for intelligence, surveillance, and strike operations at altitudes up to 50,000 feet and endurance exceeding 27 hours.[49] In recent decades (2010–2025), sustainability efforts have focused on sustainable aviation fuels (SAF), derived from non-petroleum sources like waste oils, which reduce lifecycle CO2 emissions by up to 80%; production scaled from pilot projects in 2011 to commercial blending mandates in Europe by 2025, with global supply reaching 1 million tons in 2024. As of 2025, production is projected to reach 2 million tons, with the EU's 2% SAF blending mandate in effect since January.[50][51][52] Hypersonic prototypes like the X-51A Waverider demonstrated scramjet propulsion in 2013, sustaining Mach 5+ flight for over six minutes during its final test, paving the way for future high-speed transport.[53] Electric fixed-wing aircraft gained traction with the Pipistrel Velis Electro, the first fully electric model to receive type certification in 2020, enabling zero-emission training flights with a 50-minute endurance and operations in over 30 countries.[54]Types and Classifications

Powered Airplanes

Powered airplanes represent the primary category of fixed-wing aircraft equipped with propulsion systems, such as piston, turboprop, or jet engines, enabling sustained, self-powered flight for transport, utility, and other roles. These aircraft are distinguished by their reliance on onboard power for takeoff, climb, cruise, and landing, contrasting with unpowered types that depend on external forces like thermals or towing. Design and classification focus on operational purpose, size, and performance requirements, with examples spanning light personal planes to massive freighters. Commercial airliners form a key subclass, optimized for efficient passenger transport over medium to long distances. Narrow-body models, characterized by a single central aisle, include the Boeing 737 family, which seats approximately 126 to 220 passengers depending on configuration and variant. These aircraft prioritize point-to-point routes with lower operating costs per seat. In contrast, wide-body airliners feature twin aisles for higher capacity and range; the Airbus A380, for instance, accommodates 525 to 853 passengers in typical three-class or high-density setups, respectively, enabling hub-to-hub operations on high-demand corridors. General aviation encompasses non-commercial powered airplanes used for personal, training, business, and recreational flying. Light single-engine models like the Cessna 172, introduced in 1956 as a four-seat, high-wing trainer, exemplify this group with its simplicity, reliability, and versatility for flight instruction and short trips.[55] Business jets, a specialized subset, offer speed and comfort for corporate travel; the Learjet 23, first flown in 1963, pioneered this market as a compact twin-engine jet seating up to eight passengers with a cruise speed exceeding 500 mph.[56] Cargo and freighter variants adapt powered airplane designs for freight transport, often by modifying passenger models to include large cargo doors and reinforced floors. Converted airliners such as the McDonnell Douglas DC-10 freighter feature removable passenger interiors and a main-deck cargo capacity of approximately 143,000 pounds (65,000 kg), supporting global logistics with its three-engine configuration.[57] Heavy-lift specialists like the Antonov An-225, which entered service in 1988, achieved unprecedented payloads of 250 metric tons, primarily for oversized cargo such as rocket components or wind turbine blades, but was destroyed in 2022.[58] Design subtypes in powered airplanes influence handling, efficiency, and mission suitability. High-wing configurations, common in general aviation like the Cessna 172, enhance pilot visibility over the ground and provide greater propeller clearance, aiding operations on rough fields.[59] Low-wing designs, prevalent in faster models such as business jets, reduce interference with airflow over the fuselage for improved speed and roll rates. Retractable landing gear further boosts efficiency by minimizing drag during cruise, potentially increasing airspeed by 10 to 15 mph while reducing fuel consumption on longer flights.[60] Certification standards ensure safety and airworthiness, varying by aircraft size and role under U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations. Part 23 applies to small airplanes, covering normal, utility, acrobatic, and commuter categories with maximum takeoff weights up to 19,000 pounds, emphasizing simplicity for general aviation.[61] Part 25 governs larger transport-category airplanes, including commercial airliners and freighters over 12,500 pounds, with stringent requirements for crashworthiness, systems redundancy, and performance in adverse conditions.[62]Unpowered Gliders and Kites

Unpowered fixed-wing aircraft encompass a range of designs that achieve sustained flight without onboard propulsion, relying instead on gravity for initial descent, atmospheric thermals for lift, or wind gradients for energy extraction. These craft prioritize aerodynamic efficiency through high lift-to-drag (L/D) ratios to minimize sink rates and maximize glide distances. Sailplanes, also known as gliders, represent the most advanced crewed examples, featuring rigid wings with high aspect ratios typically exceeding 30:1, which enable low drag and efficient lift generation at low angles of attack. Modern sailplanes achieve glide ratios of 40:1 to 70:1, allowing them to travel forward distances far exceeding their altitude loss in still air; for instance, the high-performance DG-800 sailplane boasts a glide ratio of approximately 50:1. Launch methods for sailplanes include aerotowing by powered aircraft, which elevates the glider to several thousand feet, or ground-based winches that accelerate the craft to takeoff speed via a cable, providing altitudes up to 2,000 feet in seconds. World records for sailplane distance flights exceed 1,000 kilometers, often accomplished by exploiting ridge lift or thermals over extended cross-country routes.[63] Hang gliders, developed in the late 1960s and gaining widespread popularity in the 1970s, utilize flexible delta-shaped wings constructed from aluminum frames and Dacron sailcloth, with the pilot suspended prone in a harness beneath the wing for control via weight shift. Early innovations, such as those by Francis Rogallo and companies like Delta Wing Kites, adapted flexible wing concepts from NASA research, enabling safe recreational flight and leading to cross-country capabilities by the mid-1970s. Typical performance includes forward speeds of 50-100 km/h and glide ratios ranging from 5:1 for basic models to over 10:1 for advanced designs, allowing flights of tens of kilometers when using thermals.[64][65][66] Kites, as tethered fixed-wing unpowered craft, generate lift from wind to provide traction or elevation, differing from free-flight gliders by their ground-anchored lines that limit range but enable controlled maneuvers. Sport kites, often rigid or semi-rigid designs with aspect ratios around 3:1 to 5:1, are used for precision aerobatics and can achieve speeds up to 100 km/h in gusty winds, emphasizing agility over distance. Utility kites, such as parafoils—inflatable ram-air designs resembling flexible wings—offer high lift coefficients for applications like towing watercraft or generating airborne wind energy, with tether lengths up to several hundred meters to harness traction forces exceeding 10 kN in strong winds.[67] Unmanned variants of fixed-wing gliders extend these principles to remote operations, including model gliders for hobbyist testing and larger drones for reconnaissance, which deploy via catapult or hand-launch and rely on passive gliding or active soaring. Dynamic soaring techniques, inspired by albatross flight, enable extended endurance by cyclically diving and climbing through wind shear gradients, allowing small UAVs to harvest energy without propulsion; NASA simulations demonstrate potential flight durations of hours in suitable wind conditions. These systems are employed in environmental monitoring and military surveillance, with examples like the Pathfinder glider achieving reconnaissance flights over 100 km using thermal updrafts.[68][69] Performance in unpowered fixed-wing craft centers on minimizing sink rates—typically 0.5 to 2 m/s for efficient designs—to extend glide time, achieved through wing shapes that maximize the L/D ratio, often 20:1 or higher in sailplanes. For example, at best L/D speed, a glider with a 2.1 m/s sink rate and 50 km/h forward speed yields an L/D of approximately 24:1, illustrating how low induced drag from high-aspect-ratio wings sustains flight in weak updrafts. No engines are present, so operational focus remains on environmental energy capture to counter inevitable descent.[63][70]Specialized Variants

Fixed-wing aircraft have been adapted into specialized variants to operate in unique environments or fulfill niche functions, such as water-based operations or extreme altitude profiles, by incorporating modifications like floats, hulls, or advanced propulsion systems. These designs prioritize environmental compatibility over conventional land-based performance, enabling access to remote or challenging terrains. Seaplanes and amphibians represent early adaptations for water operations, featuring floats or hulls that allow takeoff and landing on water surfaces. The first successful powered seaplane flight occurred on March 28, 1910, when French inventor Henri Fabre piloted the Hydravion from the Étang de Berre near Marseille, covering approximately 650 meters.[71] This milestone marked the origins of seaplane technology in the 1910s, with subsequent developments including flying boats and floatplanes for reconnaissance and transport. Modern amphibians, such as the Cessna 208 Caravan, combine a robust utility airframe with amphibious floats or retractable landing gear, enabling operations on both water and land while carrying up to nine passengers at speeds around 185 km/h.[72] These variants emerged prominently post-World War I, with designs like the Grumman Albatross series in the 1940s exemplifying durable hull-based amphibians for search-and-rescue missions.[73] Ground-effect vehicles, or ekranoplans, exploit the wing-in-ground effect to fly at low altitudes of 1-5 meters above water or flat surfaces, reducing drag and enhancing efficiency for high-speed transport. Developed primarily in the Soviet Union during the Cold War, these fixed-wing craft resemble oversized ekranoplans with ekranodynamic wings. The KM (Korabl-Maket), an experimental prototype from the late 1960s, conducted trials on the Caspian Sea and achieved a maximum speed of 650 km/h at heights of 4-14 meters, powered by eight Kuznetsov NK-12 turboprops. Designed by Rostislav Alexeyev, the KM served as a testbed for larger operational vehicles, demonstrating the potential for rapid maritime traversal but facing challenges like structural stress from wave interactions.[74] Powered gliders, also known as motor gliders, integrate retractable or foldable engines into glider airframes for self-launch capability, extending operational range beyond traditional soaring. These variants allow pilots to launch independently from short runways or fields, then retract the propeller for efficient gliding with ratios up to 29:1. The Pipistrel Sinus, a two-seat ultralight motor glider introduced in the early 2000s, exemplifies this design with its 80 hp Rotax 912 engine and 15-meter wingspan, enabling ranges exceeding 1,500 km on full tanks while maintaining a cruise speed of 200 km/h.[75] By adding powered segments, motor gliders like the Sinus extend unpowered range by over 200 km, supporting cross-country flights in varied conditions without reliance on tow aircraft.[76] Ultralights and homebuilt aircraft emphasize minimalist, lightweight construction for recreational and experimental flying, often under strict weight limits to simplify regulation and enhance accessibility. In the United States, ultralights are defined under FAA Part 103 as powered vehicles with an empty weight below 254 pounds (115 kg), excluding floats, and a maximum fuel capacity of 5 U.S. gallons. Homebuilt variants, assembled from kits by individuals, promote innovation in composite materials and aerodynamics. The Rutan VariEze, designed by Burt Rutan and first flown in 1975 as prototype N7EZ, pioneered canard configurations in homebuilts with its all-composite structure and Volkswagen-derived engine, achieving high efficiency for cross-country travel.[77] Plans released in 1976 enabled widespread amateur construction, influencing subsequent experimental designs focused on low-cost, high-performance flight.[78][79] Space-optimized fixed-wing aircraft, such as rocket planes, adapt conventional aerodynamics for suborbital trajectories, using hybrid rocket propulsion to reach altitudes beyond 100 km. These variants feature articulated wings for reentry stability and are typically air-launched from carrier aircraft. SpaceShipOne, developed by Scaled Composites and first flown suborbitally in 2004, achieved a peak altitude of 112 km on its October 4 flight, piloted by Brian Binnie, marking the first private crewed spaceflight.[80] Powered by a nitrous oxide and rubber hybrid engine, it demonstrated feasibility for reusable suborbital vehicles, reaching speeds up to 3,000 ft/s while maintaining fixed-wing control surfaces for atmospheric reentry.[81] This design won the Ansari X Prize, catalyzing commercial space tourism initiatives.[82]Structural Design

Airframe Components

The airframe of a fixed-wing aircraft serves as the foundational skeleton, integrating the fuselage, wings, and empennage to form a cohesive structure capable of withstanding aerodynamic, gravitational, and operational loads. The fuselage acts as the central body, housing crew, passengers, cargo, and systems while providing attachment points for other components. Wings generate lift and are connected to the fuselage via primary fittings that transfer shear and bending moments. The empennage, comprising the horizontal and vertical stabilizers, ensures directional stability and control, integrated through rear fuselage attachments that distribute tail loads forward along the structure. Load paths are primarily managed by spars—longitudinal beams in wings and fuselage that carry bending and torsional forces—and ribs, which are transverse elements maintaining airfoil shape and distributing localized stresses to the skin.[1][83] Early fixed-wing aircraft relied on wood frames covered in fabric for their lightweight and easily workable properties, offering basic strength but prone to environmental degradation. By the 1930s, aluminum alloys, such as those alloyed with copper and magnesium, revolutionized construction through stressed-skin designs, providing superior strength-to-weight ratios and enabling larger, faster aircraft like the Douglas DC-3. The 1980s marked the introduction of composite materials, including carbon fiber-reinforced polymers, initially for secondary structures in models like the Boeing 767, due to their exceptional stiffness and corrosion resistance. Titanium alloys, valued for their high strength, low density, and heat tolerance, are employed in high-stress areas such as engine mounts and landing gear components to endure extreme fatigue and temperatures.[84][85][86][87] Aircraft airframes predominantly adopt semi-monocoque construction, where the outer skin shares stress loads with an internal framework of frames, stringers, and bulkheads, distributing forces across the structure for efficiency and redundancy. In contrast, pure monocoque designs rely almost entirely on the skin for load-bearing, as seen in some early fuselages, but offer less damage tolerance. Stressed-skin configurations in semi-monocoque setups enhance overall rigidity while incorporating fail-safe features, such as multiple load paths and crack-arresting elements, to prevent catastrophic failure from localized damage. This approach ensures structural integrity under dynamic conditions, with the skin contributing up to 70% of the compressive strength in modern designs.[1][83] Structural weight optimization is critical, with empty weight typically comprising 40-60% of maximum takeoff weight (MTOW) in transport aircraft, balancing payload, fuel, and performance needs. Design limits vary by category; for transport category aircraft under 14 CFR Part 25, positive load factors range from 2.5g to 3.8g and negative up to -1.0g, ensuring the airframe withstands gusts and maneuvers without permanent deformation, followed by a 1.5 safety factor to ultimate loads.[88] Maintenance standards, governed by FAA regulations, mandate periodic inspections—such as annual checks and 100-hour cycles for commercial operations—to detect fatigue, cracks, and corrosion in alloy components. Corrosion prevention involves anodizing aluminum surfaces to form protective oxide layers, applying primers and paints, and routine cleaning with corrosion-inhibiting compounds, ensuring longevity in harsh environments like saltwater exposure.[89][90]Wing Configurations