Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

African art

View on Wikipedia

| African art | |

|---|---|

| History of art |

|---|

African art refers to works of visual art, including works of sculpture, painting, metalwork, and pottery, originating from the various peoples of the African continent and influenced by distinct, indigenous traditions of aesthetic expression.

While the various artistic traditions of such a large and diverse continent display considerable regional and cultural variety, there are consistent artistic themes, recurring motifs, and unifying elements across the broad spectrum of the African visual expression.[2] As is the case for every artistic tradition in human history, African art was created within specific social, political, and religious contexts. Likewise, African art was often created not purely for art's sake, but rather with some practical, spiritual, and/or didactic purpose in mind. In general, African art prioritizes conceptual and symbolic representation over realism, aiming to visualize the subject's spiritual essence.[3]

Ethiopian art, heavily influenced by Ethiopia's long-standing Christian tradition,[4] is also different from most African art, where Traditional African religion (with Islam prevalent in the north east and north west presently) was dominant until the 20th century.[5] African art includes prehistoric and ancient art, the Islamic art of West Africa, the Christian art of East Africa, and the traditional artifacts of these and other regions. Many African sculptures were historically made of wood and other natural materials that have not survived from earlier than a few centuries ago, although rare older pottery and metal figures can be found in some areas.[6] Some of the earliest decorative objects, such as shell beads and evidence of paint, have been discovered in Africa, dating to the Middle Stone Age.[7][8][9]

Masks are important elements in the art of many people, along with human figures, and are often highly stylized. There exist diverse styles, which can often be observed within a single context of origin and may be influenced by the intended use of the object. Nevertheless, broad regional trends are discernible. Sculpture is most common among "groups of settled cultivators in the areas drained by the Niger and Congo rivers" in West Africa.[10] Direct images of deities are relatively infrequent, but masks in particular are or were often made for ritual ceremonies. Since the late 19th century, there has been an increasing amount of African art in Western collections, the finest pieces of which are displayed as part of the history of colonization.

African art had an important influence on European Modernist art,[11] which was inspired by their interest in abstract depiction.[3] It was this appreciation of African sculpture that has been attributed to the very concept of "African art", as seen by European and American artists and art historians.[12]

West African cultures developed bronze casting for reliefs, like the famous Benin Bronzes, to decorate palaces and for highly naturalistic royal heads from around the Bini town of Benin City, Edo State, as well as in terracotta or metal, from the 12th–14th centuries. Akan gold weights are a form of small metal sculptures produced from 1400 to 1900; some represent proverbs, contributing a narrative element rare in African sculpture; and royal regalia included gold sculptured elements.[13] Many West African figures are used in religious rituals and are often coated with materials placed on them for ceremonial offerings. The Mande-speaking peoples of the same region make pieces from wood with broad, flat surfaces and arms and legs shaped like cylinders. But in Central Africa the main distinguishing characteristics include heart-shaped faces that are curved inward and display patterns of circles and dots.

Definitions

[edit]Some definitions of African art include the artistic production of African diasporas, such as African-American art, Afro-Caribbean Art, and Latin American art inspired by African traditions. However, African art does not usually encompass the artistic traditions of North Africa, which have been predominantly influenced by distinct artistic traditions, such as Punic art, Greco-Roman Art, Islamic Art, and other styles originating beyond Africa. As a result of geographic factors, namely North Africa's proximity with the Mediterranean and the natural boundaries, such as the Sahara, separating North Africa with the rest of continent, the influence of indigenous African forms of art would have been lower by comparison.

Thematic elements

[edit]In Western African art there is a particular focus on expressiveness and individuality. The art of the Dan people is an example of this, and it has also extended its influence beyond the continent.[14]

The human figure has long been the central subject of most African art, and this emphasis has influenced certain European artistic traditions.[11] For instance, during the fifteenth century, Portugal engaged in trade with the Sapi culture near the Ivory Coast in West Africa. The Sapi artists produced intricate ivory salt cellars that merged African and European design elements—most notably through the inclusion of the human figure, which was typically absent in Portuguese saltcellars. In African art, the human figure can symbolize the living or the dead, represent chiefs, dancers, or various trades, serve as an anthropomorphic image of a deity, or fulfill other votive and spiritual functions. Another recurring theme is the intermorphosis of humans and animals, blurring the boundaries between species to convey symbolic meaning.

Visual abstraction: African artworks often prioritize visual abstraction over naturalistic representation. This stylistic tendency stems from the widespread use of generalized and codified forms, which reflect cultural values, spiritual beliefs, and artistic conventions rather than realistic depictions.[15]

Scope

[edit]The study of African art until recently[when?] focused on the traditional art of certain well-known groups on the continent, with a particular emphasis on traditional sculpture, masks and other visual culture from non-Islamic West Africa, Central Africa,[16] and Southern Africa with a particular emphasis on the 19th and 20th centuries. Recently, however, there has been a movement among African art historians and other scholars to include the visual culture of other regions and time periods. The notion is that by including all African cultures and their visual culture over time in African art, there will be a greater understanding of the continent's visual aesthetics across time. Finally, the arts of the African diaspora, in Brazil, the Caribbean and the south-eastern United States, have also begun to be included in the study of African art.

Materials

[edit]

African art is produced using a wide range of materials and takes many distinct shapes. Because wood is a prevalent material, wood sculptures make up the majority of African art. Other materials used in creating African art include clay soil. Jewelry is a popular art form used to indicate rank, affiliation with a group, or purely aesthetics.[17] African jewelry is made from such diverse materials as Tiger's eye stone, Hematite, Sisal, coconut shell, beads and Ebony wood. Sculptures can be wooden, ceramic or carved out of stone like the famous Shona sculptures,[18] and decorated or sculpted pottery comes from many regions. Various forms of textiles are made including Kitenge, mud cloth and Kente cloth. Mosaics made of butterfly wings or colored sand are popular in West Africa. Early African sculptures can be identified as being made of terracotta and bronze.[19]

Traditional African religions

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2018) |

Traditional African religions have been extremely influential on African art forms across the continent. African art often stems from the themes of religious symbolism, functionalism and utilitarianism. With many pieces of art that are created for spiritual rather than purely creative purposes. The majority of popular African artworks can be understood as the tools, such as the representative figurines used in religious rituals and ceremonies.[20] Many African cultures emphasize the importance of ancestors as intermediaries between the living, the Gods, and the supreme creator. Art is seen as a way to contact these spirits of ancestors. Art may also be used to depict Gods and is valued for its functional purposes.[21] For example, African God Ogun who is the God of iron, war, and craftsmanship.

However, it is important to note that the arrival of both Christianity and Islam have also greatly influenced the art of the African continent, and the traditions of both have been integrated into the beliefs and artwork of traditional African religion.[22]

History

[edit]The origins of African art lie long before the recorded history. The region's oldest known beads were made from Nassarius shells and worn as personal ornaments 72,000 years ago.[7] In Africa, evidence for the making of paints by a complex process exists from about 100,000 years ago[8] and of the use of pigments from around 320,000 years ago.[9][23] African rock art in the Sahara in Niger preserves 6000-year-old carvings.[24] Along with sub-Saharan Africa, the Western cultural arts, ancient Egyptian paintings and artifacts, and indigenous southern crafts also contributed greatly to African art. The abundance of surrounding nature was often depicted through abstract interpretations of animals, plant life, or natural designs and shapes. The Nubian Kingdom of Kush in modern Sudan was in close and often hostile contact with Egypt and produced monumental sculptures mostly derivative of styles that did not lead to the north. In West Africa, the earliest known sculptures are from the Nok culture, which thrived between 1,500 BC and 500 AD in modern Nigeria. Its clay figures typically feature elongated bodies and angular shapes.[25]

More complex methods of producing art were developed in sub-Saharan Africa around the 10th century, some of the most notable advancements include the bronze work of Igbo Ukwu and the terracotta and metalworks of Ile Ife Bronze and brass castings, often ornamented with ivory and precious stones, became highly prestigious in much of West Africa, sometimes being limited to the work of court artisans and identified with royalty, as with the Benin Bronzes.

As Europeans explored the coasts of West Africa, they discovered a wide range of functional objects that Africans used for cultural, social, and economic purposes. Oath devices, for instance, were essential to securing business relationships during the era of the Atlantic slave trade. Though these works of craftsmanship followed their own aesthetic principles, they were regarded as tools of sorcery by European travel writers and reduced to a category of "fetish," which was understood to be outside the realm of art.[26]

Influence on Western art

[edit]

During and after the 19th and 20th-century colonial period, Westerners long characterized African art as "primitive." The term carries with it negative connotations of underdevelopment and poverty. Colonization during the nineteenth century set up a Western understanding hinged on the belief that African art lacked technical ability due to its low socioeconomic status.

At the start of the twentieth century, art historians like Carl Einstein, Michał Sobeski and Leo Frobenius published important works about the theme, giving African art the status of an aesthetic object, not only of an ethnographic object.[27] At the same time, artists like Paul Gauguin, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, André Derain, Henri Matisse, Joseph Csaky, and Amedeo Modigliani became aware of and inspired by, African art, amongst other art forms.[11] In a situation where the established avant-garde was straining against the constraints imposed by serving the world of appearances, African art demonstrated the power of supremely well-organized forms; produced not only by responding to the faculty of sight but also and often primarily, the faculty of imagination, emotion and mystical and religious experience. These artists saw in African art a formal perfection and sophistication unified with phenomenal expressive power. The study of and response to African art, by artists at the beginning of the twentieth century facilitated an explosion of interest in the abstraction, organization, and reorganization of forms, and the exploration of emotional and psychological areas hitherto unseen in Western art. By these means, the status of visual art was changed. Art ceased to be merely and primarily aesthetic, but became also a true medium for philosophic and intellectual discourse, and hence more truly and profoundly aesthetic than ever before.[28]

- Abstraction and Form: African sculptures and masks showcased a departure from literal representation, emphasizing geometric forms and symbolic proportions, which inspired movements like Cubism and Fauvism.

- Emotional and Psychological Depth: The expressive power of African art encouraged modernist artists to explore raw emotion, spirituality, and the subconscious.

- Philosophical and Intellectual Discourse: The integration of African aesthetics transformed art from mere representation to a medium for exploring profound ideas, redefining the role of visual art in intellectual and cultural contexts.

Traditional art

[edit]Traditional art describes the most popular and studied forms of African art typically found in museum collections.

Wooden masks, which might either be of human, animal or legendary creatures, are one of the most commonly found forms of art in Western Africa. In their original contexts, ceremonial masks are used for celebrations, initiations, crop harvesting, and war preparation. The masks are worn by a chosen or initiated dancer. During the mask ceremony the dancer goes into a deep trance, and during this state of mind he "communicates" with his ancestors. The masks can be worn in three different ways: vertically covering the face: as helmets, encasing the entire head, and as a crest, resting upon the head, which was commonly covered by material as part of the disguise. African masks often represent a spirit and it is strongly believed that the spirit of the ancestors possesses the wearer. Most African masks are made with wood, and can be decorated with: Ivory, animal hair, plant fibers (such as raffia), pigments (like kaolin), stones, and semi-precious gems also are included in the masks.

Statues, usually of wood or ivory, are often inlaid with cowrie shells, metal studs and nails. Decorative clothing is also commonplace and comprises another large part of African art. Among the most complex of African textiles is the colorful, strip-woven Kente cloth of Ghana. Boldly patterned mudcloth is another well-known technique.

Contemporary African art

[edit]

Africa is home to a thriving contemporary art and fine art culture. This has been under-studied until recently, due to scholars' and art collectors' emphasis on traditional art. Notable modern artists include El Anatsui, Marlene Dumas, William Kentridge, Karel Nel, Kendell Geers, Yinka Shonibare, Zerihun Yetmgeta, Odhiambo Siangla, George Lilanga, Elias Jengo, Olu Oguibe, Lubaina Himid, Bili Bidjocka and Henry Tayali. Art bienniales are held in Dakar, Senegal, and Johannesburg, South Africa. Many contemporary African artists are represented in museum collections, and their art may sell for high prices at art auctions. Despite this, many contemporary African artists tend to have a difficult time finding a market for their work. Many contemporary African arts borrow heavily from traditional predecessors. Ironically, this emphasis on abstraction is seen by Westerners as an imitation of European and American Cubist and totemic artists, such as Pablo Picasso, Amedeo Modigliani and Henri Matisse, who, in the early twentieth century, were heavily influenced by traditional African art. This period was critical to the evolution of Western modernism in visual arts, symbolized by Picasso's breakthrough painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon.[29]

Since the late 20th century, artists such as Ibrahim El-Salahi and Fathi Hassan have emerged as significant early figures in the development of contemporary Black African art. However, the foundations of contemporary African artistic expression were laid earlier, particularly during the 1950s and 1960s in South Africa, where artists like Irma Stern, Cyril Fradan, and Walter Battiss played pioneering roles. Institutions such as the Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg also contributed to the promotion and visibility of African modernism during this period.

In more recent decades, the global art scene has shown growing interest in African contemporary art, largely thanks to the support of European galleries like the October Gallery in London and the involvement of prominent collectors such as Jean Pigozzi, Artur Walther, and Gianni Baiocchi. This international interest has led to an increase in major exhibitions featuring African artists, including events held at the Africa Center in New York and the African Pavilion at the 2007 Venice Biennale.

A pivotal moment for the international recognition of African art came with the appointment of Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor as the artistic director of Documenta 11 in 2002. His African-centered curatorial approach provided a global platform for many African artists, significantly advancing their visibility and careers within the broader contemporary art world.

A wide range of more-or-less traditional forms of art or adaptations of traditional style to contemporary taste is made for sale to tourists and others, including so-called "airport art". Several popular traditions assimilate Western influences into African styles such as the elaborate fantasy coffins of Southern Ghana, made in a variety of different shapes which represent the occupations or interests of the deceased or elevate their status. The Ga people are said to believe that an elaborate funeral will benefit the status of their loved ones in the afterlife, so families often spare no expense when deciding which coffin they want for their relatives.[30] These coffins can take the forms of cars, cocoa pods, chickens, or any other shape a family may choose to represent the deceased.[31]

Pop art and advertising art

[edit]Art used to advertise for local businesses, including barbershops, movie houses, and appliance stores has become internationally celebrated in galleries and has launched the careers of many contemporary African artists, from Joseph Bertiers of Kenya to several movie poster painters in Ghana.[32] Ghanaian hand-painted movie posters on canvas and flour sacks from the 1980s and 1990s have been exhibited at museums around the world and sparked viral social media attention due to their highly imaginative and stylized depictions of Western films.[33][34] This creative interpretation of Western culture through African art styles is also on display with the tradition of praise portraits depicting international celebrities, which often served as storefront advertising art, and have since become widely valued and collected in the global art market.

Minimalist African art

[edit]Another notable contemporary African artist is Amir Nour, a Sudanese artist who lived in Chicago. In the 1960s he created a metal sculpture called Grazing at Shendi (1969) which consists of geometric shapes that connect with his memory of his homeland.[35] The sculpture resembles grazing sheep in the distance. He valued discovering art within the society of the artist, including culture, tradition, and background.[36]

By country, civilizations or people

[edit]West Africa

[edit]Ghana

[edit]In the 17th century, the area of present-day Ghana was a center for trade and cultural exchange. The states in the region were connected through trading networks and shared cultural beliefs but remained politically independent. This arrangement lasted until the early 18th century when the leader Osei Tutu initiated a vast land expansion that unified these smaller states.

The kingdom's economy, which grew through trade in gold, cloth, and enslaved people, supported the development of its artistic culture. Ghanaian artworks range from wood carvings to brass works, figures, and gems.

Kente is a traditional, multi-colored, hand-woven cloth made from silk and cotton. It consists of interwoven cloth strips and is central to Ghanaian culture. It is traditionally worn as a wrap by men and women of various Ghanaian ethnic groups, with variations in style for each.

- Colors and their meanings

There are different color variations for Kente, each with a different meaning:

- Black: maturation

- White: purification

- Yellow: preciousness

- Blue: peacefulness

- Red: bloodshed[37]

Akan art originated among the Akan people. Akan art includes traditions such as textiles, sculpture, Akan goldweights, and gold and silver jewelry. Akan art is characterized by a connection between visual and verbal expression and a blending of art and philosophy. Akan culture values gold above other metals, and it is used to represent supernatural elements, royal authority, and cultural values. According to Asante oral tradition, their origins are linked to the arrival of a golden stool, which is believed to hold the soul of the Asante nation. In some Akan cultural beliefs, gold symbolized the sun and was associated with royal authority. It was often used in art to signify the king's importance, representing key cultural and social values.[38] Kente cloth is another important art tradition of Akan culture. According to oral tradition, Kente cloth originated from attempts to replicate spider webs through weaving. Kente cloth is recognized for its colors and intricate patterns. Its original purpose was to represent royal power and authority, but it has since become a symbol of tradition and has been adopted by other cultures.[39]

-

Ashanti trophy head; circa 1870; pure gold; Wallace Collection (London). This artwork represents an enemy chief killed in battle. Weighing 1.5 kg (3.3 lb), it was attached to the Asante king's state sword

-

Doll (Akuaba); 20th century; 27.3 x 11.4 x 3.8 cm (103⁄4 x 41⁄2 x 11⁄2 in.); Brooklyn Museum (New York City)

-

Soul washer badge (Akrafokonmu); 18th-19th century; gold; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Nigeria

[edit]Nigerian art is inspired by the country's diverse folklore and traditional heritage. Art forms from Nigeria include stone carvings, pottery, glasswork, woodcarvings, and bronze works. Benin and Awka are known as centers for wood carving, a craft that has long been practiced throughout southern Nigeria.

Examples of Nigerian Traditional Art

Masks

Masks are part of the animist beliefs of the Yoruba people. Painted masks are worn by dancers during funerals and other ceremonies to communicate with or appease spirits.

Pottery

Pottery has a long tradition in Nigeria, with evidence of its production dating back to at least 100 B.C. Suleja, Abuja, and Ilorin are considered important centers of traditional pottery. Potters in Nigeria are often women, and the techniques are typically passed down through families.

Textiles

The Yoruba use a local plant to create indigo-dyed batik cloth. Women traditionally perform the dyeing, while in the north, the craft is practiced exclusively by men. Weavers in many parts of the country produce textiles with lace-like designs. Oyo state is known for its fine woven textiles, while weavers in Abia state use a broadloom technique.

The Nok culture is an early Iron Age population whose material remains are named after the Ham village of Nok in Kaduna State of Nigeria, where their famous terracotta sculptures were first discovered in 1928. The Nok Culture appeared in northern Nigeria around 1500 BC[25] and vanished under unknown circumstances around 500 AD, having lasted for approximately 2,000 years.[40]

The function of Nok terracotta sculptures remains unknown. For the most part, the terracotta is preserved in the form of scattered fragments. For this reason, Nok art is best known today for its heads, both male and female, which feature particularly detailed and refined hairstyles. The statues are fragmented because the discoveries are usually made from alluvial mud,[41][42][43] in terrain formed by water erosion. The terracotta statues recovered from these deposits are typically rolled, polished, and broken. Rarely are works of great size conserved intact, making them highly valued on the international art market. The terracotta figures are hollow, coil-built, nearly life-sized human heads and bodies that are depicted with highly stylized features, abundant jewelry, and varied postures.

Little is known of the original function of the pieces, but theories include ancestor portrayal, grave markers, and charms to prevent crop failure, infertility, and illness. Also, based on the dome-shaped bases found on several figures, they could have been used as finials for the roofs of ancient structures. Margaret Young-Sanchez, Associate Curator of Art of the Americas, Africa, and Oceania in The Cleveland Museum of Art, explains that most Nok ceramics were shaped by hand from coarse-grained clay and subtractively sculpted in a manner that suggests an influence from wood carving. After some drying, the sculptures were covered with slip and burnished to produce a smooth, glossy surface. The figures are hollow, with several openings to facilitate thorough drying and firing. The firing process most likely resembled that used today in Nigeria, in which the pieces are covered with grass, twigs, and leaves and burned for several hours.

As a result of natural erosion and deposition, Nok terracottas were scattered at various depths throughout the Sahel grasslands, causing difficulty in the dating and classification of the artifacts. Two archaeological sites, Samun Dukiya and Taruga, were found containing Nok art that had remained unmoved. Radiocarbon and thermo-luminescence tests narrowed the sculptures’ age down to between 2,000 and 2,500 years ago, making them some of the oldest in Western Africa. Many further dates were retrieved in the course of new archaeological excavations, extending the beginnings of the Nok tradition even further back in time.[44]

Because of the similarities between the two sites, archaeologist Graham Connah believes that "Nok artwork represents a style that was adopted by a range of iron-using farming societies of varying cultures, rather than being the diagnostic feature of a particular human group as has often been claimed."

-

Nok seated figure; 5th century BC – 5th century AD; terracotta; 38 cm (1 ft 3 in); Musée du quai Branly (Paris). In this Nok work, the head is dramatically larger than the body supporting it, yet the figure possesses elegant details and a powerful focus. The neat protrusion from the chin represents a beard. Necklaces form a cone around the neck and keep the focus on the face.

-

Relief fragment with heads and figures; 5th century BC – 5th century AD; length: 50 cm (20 in), height: 54 cm (21 in), width: 50 cm (20 in); terracotta; Musée du quai Branly. Like most African art styles, the Nok style focuses mainly on people, rarely on animals. All of the Nok statues are stylized and similar in that they have triangular-shaped eyes with perforated pupils, and arched eyebrows.

-

Male head; 550–50 BC; terracotta; Brooklyn Museum (New York City, USA). The mouth of this head is slightly open. It may suggest speech, that the figure has something to say. This is a figure that seems to be in the midst of a conversation. The eyes and the eyebrows suggest an inner calm or an inner serenity.

-

Male figure; terracotta; Detroit Institute of Art (Michigan, USA)

Benin art

[edit]Benin art is the art from the Kingdom of Benin or Edo Empire (1440–1897), a pre-colonial African state located in what is now the South-South region of Nigeria. The Benin Bronzes are a group of more than a thousand metal plaques and sculptures that decorated the royal palace of the Kingdom of Benin in what is now Nigeria.[a] Collectively, the objects form the best-known examples of Benin art, created from the thirteenth century onwards, by the Edo people. This art also included other sculptures in brass or bronze, including some famous portrait heads and smaller pieces.

In 1897, most of the plaques and other objects in the collection were taken by a British force during the Benin Expedition of 1897, which took place as British control in Southern Nigeria was being consolidated.[47] Two hundred of the pieces were taken to the British Museum, while the rest were purchased by other museums in Europe.[48] Today, a large number are held by the British Museum,[47] as well as by other notable collections in German and American museums.[49]

-

Plaque with warriors and attendants; 16th–17th century; brass; height: 47.6 cm (183⁄4 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Plaque equestrian an Oba on horseback with attendants; between 1550 and 1680; brass; height: 49.5 cm (197⁄16 in.), width: 41.9 (161⁄2 in.), diameter: 11.4 cm (41⁄2 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Plaque that probably represents a musician; 17th century; bronze; 48.26 cm (19 in.) x 18.42 (71⁄4 in.) x 8.89 cm (31⁄2 in.), irregular; Los Angeles County Museum of Art (USA)

-

Rooster figure; 18th century; brass; overall: 45.4 cm (177⁄8 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Bronze Head of Queen Idia; early 16th century; bronze; Ethnological Museum of Berlin (Germany). Four cast bronze heads of the queen are known and are currently in the collections of the British Museum, the World Museum (Liverpool), the Nigerian National Museum (Lagos) and the Ethnological Museum of Berlin.

-

Leopard aquamanile; 17th century; brass; Ethnological Museum of Berlin. The bronze leopards were used to decorate the altar of the oba. The leopard, a symbol of power, appears in many bronze plaques, from the oba's palace.

-

Figure of a horn blower; 1504–1550; copper alloy; 62.2 x 21.6 x 15.2 cm (241⁄2 x 81⁄2 x 6 in.); Brooklyn Museum (New York City). Blowing a horn or flute with his right hand, his left arm is truncated. He also wears a netted cap with chevron design decorated with a feather.

-

Benin ivory mask of the queen mother Idia; 16th century; ivory, iron and copper; Metropolitan Museum of Art. One of four related ivory pendant masks among the prized regalia of the Oba of Benin; taken during the Benin Expedition of 1897 in the Southern Nigeria Protectorate

Igbo

[edit]The Igbo produce a wide variety of art, including traditional figures, masks, artifacts and textiles, as well as works in metals such as bronze. Ninth-century bronze artifacts found at Igbo Ukwu are among the earliest known Igbo artworks. Their masks are similar to those of the Fang people, as they share a combination of white and black colors in roughly the same areas.

-

Maiden spirit mask; early 20th century; wood & pigment; Brooklyn Museum (New York City, USA)

-

A mask known as the Queen of Women (Eze Nwanyi); late 19th-early 20th century; wood & pigment; Birmingham Museum of Art (Alabama, USA)

-

Bronze ceremonial vessel in form of a snail shell; 9th century; Igbo-Ukwu; Nigerian National Museum (Lagos, Nigeria)

-

Bronze ornamental staff head; 9th century; Igbo-Ukwu; Nigerian National Museum

-

Female figure for a small temple; 20th century; Indianapolis Museum of Art

Yoruba

[edit]Yoruba art is best known for the heads from Ife, made from ceramic, brass, and other materials. Much of their art is associated with the royal courts. They also produced elaborate and detailed masks and doors, painted in bright colors such as blue, yellow, red, and white.

-

Head of a king or dignitary; 12th–15th century AD; terracotta; Ethnological Museum of Berlin (Germany); discovered at Ife (Nigeria)

-

Mask for Obalufon II; circa 1300 AD; copper; height: 29.2 cm; discovered at Ife; Ife Museum of Antiquities (Ife, Nigeria)[50]

-

Gelede mask; circa 1900–1915; Detroit Institute of Arts (USA)

-

Pair of door panels and a lintel; circa 1910–1914; by Olowe of Ise; (British Museum, London)

Other ethnic groups of Nigeria

[edit]-

Carved door; circa 1920–1940; wood with iron staples; by Nupe people; Hood Museum of Art (Hanover, New Hampshire, USA)

-

Headdress; early 1900s; wood, antelope skin, basketry, cane, metal; by Ejagham people; Cleveland Museum of Art (USA)

-

Headdress; early 1900s; wood, hair; Idoma people; Cleveland Museum of Art

-

Otobo (hippopotamus) mask; by Kalabari people; British Museum (London)

Mali

[edit]The primary ethnic groups in Mali are the Bambara (also known as Bamana) and the Dogon. Smaller ethnic groups include the Marka and the Bozo fishermen of the Niger River. Ancient civilizations flourished in areas like Djenné-Djenno and Timbuktu, where numerous ancient bronze and terracotta figures have been unearthed.

Djenné-Djenno

[edit]Djenné-Djenno is famous for its figurines, which depict humans and animals, including snakes and horses. They are made of terracotta, a material that has been used in West Africa for approximately ten thousand years.

-

Terracotta seated figure; 13th century; earthenware; 29.9 cm (113⁄4 in.) high; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City, USA) The raised marks and indentations on the back of this hunched Djenné figure may represent disease or, more likely, scarification patterns. The facial expression and pose could depict an individual in mourning or pain.

-

Female figure; 13th-–15th century; terracotta covered with red ochre; height: 37.5 cm (14.8 in), width: 31 cm (12 in), depth: 24 cm (9.4 in); Musée du quai Branly (Paris)

-

Equestrian figure; 13th–15th century; height: 70.5 cm; National Museum of African Art (Washington D.C., USA)

-

Male figure; 14th-17th century; Cleveland Museum of Art (Ohio, USA)

Bambara

[edit]

The Bambara people (Bambara: Bamanankaw) adapted many artistic traditions and began to create display pieces. Before commerce was a primary motivation, their art was a sacred craft intended to display spiritual pride, religious beliefs, and customs. Examples of their artworks include the Bamana n'tomo mask. Other statues were created for communities of hunters and farmers, so that offerings could be left after long farming seasons or group hunts. Bambara art is stylistically diverse, with sculptures, masks, and headdresses that display either stylized or realistic features and either weathered or encrusted patinas. Until recently, the function of many Bambara pieces was not well understood, but in the last twenty years, field studies have revealed that certain types of figures and headdresses were associated with various societies that structure Bambara life. During the 1970s, a group of approximately twenty figures, masks, and TjiWara headdresses belonging to the "Segou style" were identified. The style is distinct and recognizable by its typical flat faces, arrow-shaped noses, all-over body triangular scarifications and, on the figures, splayed hands.

- Masks

There are three major and one minor type of Bambara mask. The first type, used by the N'tomo society, has a typical comb-like structure above the face, is worn during dances, and may be covered with cowrie shells. The second type of mask, associated with the Komo society, has a spherical head with two antelope horns on top and an enlarged, flattened mouth. They are used during dances, but some have a thickly encrusted patina acquired during other ceremonies in which libations are poured over them.

The third type has connections with the Nama society and is carved in the form of an articulated bird's head, while the fourth, minor type represents a stylized animal head and is used by the Kore society. Other Bambara masks are known to exist, but unlike those described above, they cannot be linked to specific societies or ceremonies. Bambara carvers have established a reputation for the zoomorphic headdresses worn by Tji-Wara society members. Although they are all different, they all display a highly abstract body, often incorporating a zig-zag motif, which represents the sun's course from east to west, and a head with two large horns. Bambara members of the Tji-Wara society wear the headdress while dancing in their fields at sowing time, hoping to increase the crop yield.

- Statuettes

Statuettes are a significant form of African art, often embodying cultural, spiritual, and social values. These small, often intricately crafted sculptures serve not only decorative purposes but also function as symbols of identity, ritual, and community. Found across diverse African regions, statuettes vary widely in style, material, and function, but share a common thread of storytelling and cultural significance.

- Spiritual Significance: Many African statuettes are created to honor ancestors, deities, or spirits. They are often used in religious ceremonies or placed in shrines to serve as intermediaries between the human and spiritual worlds. For example, the Bakongo Nkisi figures from Central Africa are believed to harness spiritual energy for protection, healing, or justice.

- Representation of Life Stages and Roles: Statuettes often depict key aspects of human life, such as fertility, motherhood, initiation, and leadership. The Akua’ba fertility dolls of the Akan people in Ghana symbolize the hope for healthy children, while sculptures of chiefs or elders reflect authority and wisdom.

Other Bambara figures, called Dyonyeni, are thought to be associated with either the southern Dyo society or the Kwore society. These female or hermaphrodite figures usually appear with geometric features such as large conical breasts and measure between 40 and 85 cm in height. The blacksmith members of the Dyo society used them during dances to celebrate the end of their initiation ceremonies. They were handled by dancers and placed in the middle of the ceremonial circle.

Among the corpus of Bambara figures, Boh sculptures are perhaps the best known. These statues represent a highly stylized animal or human figure and are made of wood which is repeatedly covered in thick layers of earth impregnated with sacrificial materials such as millet, chicken or goat blood, kola nuts, and alcoholic drinks. They were employed by the Kono and the Komo societies and served as receptacles for spiritual forces and could, in turn, be used for apotropaic purposes.

Individual creative talents were sometimes viewed as ways to honor spiritual beings.

Dogon

[edit]Dogon art, which consists primarily of sculptures, revolves around Dogon religious values, ideals, and beliefs.[51] Dogon sculptures are not made to be seen publicly; they are commonly hidden from the public eye within the houses of families, in sanctuaries, or kept with the Hogon.[52] The importance of secrecy is due to the symbolic meaning behind the pieces and the process by which they are made.

Themes found throughout Dogon sculpture include figures with raised arms, superimposed bearded figures, horsemen, stools with caryatids, women with children, figures covering their faces, women grinding pearl millet, women bearing vessels on their heads, donkeys bearing cups, musicians, dogs, quadruped-shaped troughs or benches, figures bending from the waist, mirror-images, aproned figures, and standing figures.[53] Signs of other contacts and origins are evident in Dogon art. The Dogon people were not the first inhabitants of the cliffs of Bandiagara. Influence from Tellem art is evident in Dogon art because of its rectilinear designs.[54]

Dogon art is extremely versatile, although common stylistic characteristics – such as a tendency towards stylization – are apparent on the statues. Their art deals with myths whose complex ensemble regulates the life of the individual. The sculptures are preserved in innumerable sites of worship, personal or family altars, altars for rain, altars to protect hunters, and in markets. As a general characterization of Dogon statues, one could say that they render the human body in a simplified way, reducing it to its essentials. Some are extremely elongated with an emphasis on geometric forms. The subjective impression is one of immobility with a sense of solemn gravity and serene majesty, although conveying at the same time a latent movement. Dogon sculpture recreates the hermaphroditic silhouettes of the Tellem, featuring raised arms and a thick patina made of blood and millet beer. The four Nommo couples, the mythical ancestors born of the god Amma, ornament stools, pillars or men's meeting houses, door locks, and granary doors. The primordial couple is represented sitting on a stool, the base of which depicts the earth while the upper surface represents the sky; the two are interconnected by the Nommo. The seated female figures, their hands on their abdomen, are linked to the fertility cult, incarnating the first ancestor who died in childbirth, and are the object of offerings of food and sacrifices by women who are expecting a child.

Kneeling statues of protective spirits are placed at the head of the dead to absorb their spiritual strength and to be their intermediaries with the world of the dead, into which they accompany the deceased before once again being placed on the shrines of the ancestors. Horsemen are reminders of the fact that, according to myth, the horse was the first animal present on earth. The Dogon style has evolved into a kind of cubism: ovoid head, squared shoulders, tapered extremities, pointed breasts, forearms and thighs on a parallel plane, and hairdos stylized by three or four incised lines. Dogon sculptures serve as a physical medium in initiations and as an explanation of the world. They serve to transmit an understanding to the initiated, who will decipher the statue according to the level of their knowledge. Carved animal figures, such as dogs and ostriches, are placed on village foundation altars to commemorate sacrificed animals, while granary doors, stools, and house posts are also adorned with figures and symbols.

There are nearly eighty styles of masks, but their basic characteristic is great boldness in the use of geometric shapes, independent of the various animals they are supposed to represent. The structure of many masks is based on the interplay of vertical and horizontal lines and shapes, while others feature triangular and conical forms. All masks have large geometric eyes and stylized features. The masks are often polychrome, but on many the color is lost; after the ceremonies, they were left on the ground and deteriorated due to termites and exposure to the elements. The Dogon continue an ancient masquerading tradition which commemorates the origin of death. According to their myths, death came into the world as a result of primeval man's transgressions against the divine order. Dama memorial ceremonies are held to accompany the dead into the ancestral realm and restore order to the universe. The performance of masqueraders – sometimes as many as 400 – at these ceremonies is considered necessary. In the case of the dama, the timing, types of masks involved, and other ritual elements are often specific to one or two villages and may not resemble those seen in locations only several kilometers distant. The masks also appear during baga-bundo rites performed by small numbers of masqueraders before the burial of a male Dogon. Dogon masks evoke the form of animals associated with their mythology, yet their significance is only understood by the highest-ranking cult members, whose role is to explain the meaning of each mask to a captivated audience.

-

Person who wears a Satimbe mask

-

Figure of a kneeling woman; circa 1500; wood; height: 35.2 cm (137⁄8 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Equestrian figure; 16th–17th century; wood; height: 68.9 cm (271⁄8 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Stool; possibly late 19th to early 20th century; wood & pigment; National Museum of African Art (Washington D.C., U.S.)

Other ethnic groups of Mali

[edit]-

Black and white picture of a female figure with raised arm; 15th–17th century; wood (ficus, moraceae), sacrificial materials; height: 44.8 cm (175⁄8 in.); by the Tellem people; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Zoomorphic figurine; 12th-16th century; by Tennenkou culture; Museo de Arte Africano Arellano Alonso (Valladolid, Spain)

-

Equestrian figurine; by Bankoni culture; Museo de Arte Africano Arellano Alonso

Burkina Faso

[edit]

Burkina Faso is a small, landlocked country north of Ghana and south of Mali and Niger. Economically, it is one of the poorest countries in the world, while its cultural traditions are diverse. This is partly because a significant portion of the population has not converted to Islam or Christianity.[55] Many of the ancient artistic traditions for which Africa is known have been preserved in Burkina Faso because many people continue to honor ancestral spirits and the spirits of nature. To a large extent, they honor the spirits through the use of masks and carved figures. Many of the countries to the north of Burkina Faso have become predominantly Muslim, while many of the countries to the south are heavily Christian. In contrast, many of the people of Burkina Faso continue to offer prayers and sacrifices to the spirits of nature and to their ancestors. As a result, they continue to use the types of art found in many museum collections in Europe and America.[56]

One of the principal obstacles to understanding the art of Burkina Faso, including that of the Bwa, has been confusion between the styles of the Bwa, "gurunsi", and Mossi, and confusion of the Bwa people with their neighbors to the west, the Bobo people. This confusion was the result of the use by French colonial officers of Jula interpreters at the turn of the century. These interpreters considered the two peoples to be the same and therefore referred to the Bobo as "Bobo-Fing" and to the Bwa as "Bobo-Oule." In fact, these two peoples are not related. Their languages and social systems are quite different, as is their art. In terms of artistic styles, the confusion stems from the fact that the Bwa, "gurunsi", and Mossi make masks that are covered with red, white, and black geometric graphic patterns. This is simply the style of the Voltaic or Gur peoples, and also includes the Dogon and other peoples who speak Voltaic languages.[57]

Ivory Coast (Côte d'Ivoire)

[edit]

The Baoulé people, the Senoufo, and the Dan people are skilled at carving wood, and each culture produces a wide variety of wooden masks. The Ivorian people use masks to represent animals in caricature, to depict deities, or to represent the souls of the departed.

As the masks are held to be of great spiritual power, it is considered taboo for anyone other than specially trained persons or chosen ones to wear or possess certain masks. These ceremonial masks are each thought to have a soul, or life force, and wearing these masks is thought to transform the wearer into the entity the mask represents.

Ivory Coast (Côte d'Ivoire) also has modern painters and illustrators. Gilbert G. Groud[58] criticizes ancient beliefs in black magic, as held with the spiritual masks mentioned above, in his illustrated book Magie Noire.

East Africa

[edit]East Africa, a region encompassing countries like Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, and Ethiopia, has a rich and diverse artistic heritage. From traditional crafts to contemporary expressions, East African art reflects the region's history, cultural complexity, and evolving identity.

Kenya

[edit]Around Lake Turkana, ancient petroglyphs exist depicting human figures and animals. Some Bantu-speaking groups create funeral posts, and carvings of human heads atop geometric designs are still produced. These more recent creations are considered a continuation of the practice, although original posts no longer exist. The Kikuyu people also continue ancient traditions in the designs painted on their shields.[59]

Contemporary Kenyan artists include Elimo Njau, founder of the Paa Ya Paa Art Centre, a Nairobi-based artists' workshop.[60] From the University of Nairobi School of Fine Art and Design came Bulinya Martins and Sarah Shiundu. They are known for their style, use of color, and execution, which builds on foundational design techniques. Unlike many of their Kenyan contemporaries, they paint using oils, acrylics, watercolors, and combinations of these media.[61][62]

The Eskenazi Museum of Art at Indiana University has a large collection of traditional art objects from Kenya including jewelry, containers, weapons, walking sticks, headrests, stools, utensils, and other objects available online.[63]

Ethiopia

[edit]

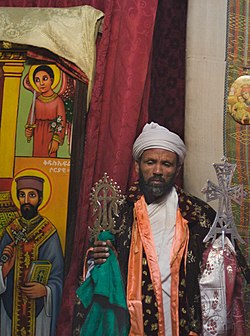

Ethiopian art from the 4th to the 20th century can be divided into two broad groupings. The first is a distinctive tradition of Christian art, mostly for churches, in forms including painting, crosses, icons, illuminated manuscripts, and other metalwork such as crowns. The second includes popular arts and crafts such as textiles, basketry, and jewellery, in which Ethiopian traditions are closer to those of other peoples in the region. Its history goes back almost three thousand years to the kingdom of D'mt. The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church has been the predominant religion in Ethiopia for over 1500 years, for most of this period in a very close relation, or union, with the Coptic Christianity of Egypt, so that Coptic art has been the main formative influence on Ethiopian church art.

Prehistoric rock art comparable to that of other African sites survives in a number of places. Until the arrival of Christianity, stone stelae, often carved with simple reliefs, were erected as grave markers and for other purposes in many regions; Tiya is one important site. The "pre-Axumite" Iron Age culture of about the 5th century BCE to the 1st century CE was influenced by the Kingdom of Kush to the north and settlers from Arabia, and produced cities with simple temples in stone, such as the ruined one at Yeha, which dates to the 4th or 5th century BCE.

The powerful Kingdom of Aksum emerged in the 1st century BCE and dominated Ethiopia until the 10th century, having become very largely Christian from the 4th century.[64] Although some buildings and large, pre-Christian stelae exist, there appears to be no surviving Ethiopian Christian art from the Axumite period. However, the earliest works remaining show a clear continuity with Coptic art of earlier periods. There was considerable destruction of churches and their contents in the 16th century when the country was invaded by Muslim neighbors. The revival of art after this was influenced by Catholic European art in both iconography and elements of style, but retained its Ethiopian character. In the 20th century, Western artists and architects began to be commissioned by the government and to train local students, and more fully Westernized art was produced alongside continuations of traditional church art.[64]

Church paintings in Ethiopia were likely produced as far back as the introduction of Christianity in the 4th century AD,[65] although the earliest surviving examples come from the church of Debre Selam Mikael in the Tigray Region, dated to the 11th century AD.[66] However, the 7th-century AD followers of the Islamic prophet Muhammad who fled to Axum in temporary exile mentioned that the original Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion was decorated with paintings.[66] Other early paintings include those from the rock-hewn churches of Lalibela, dated to the 12th century AD, and in nearby Genete Maryam, dated to the 13th century AD.[66] However, paintings in illuminated manuscripts predate the earliest surviving church paintings; for instance, the Ethiopian Garima Gospels of the 4th–6th centuries AD contain illuminated scenes imitating the contemporary Byzantine style.[67]

Ethiopian painting, on walls, in books, and in icons,[68] is highly distinctive, though the style and iconography are closely related to the simplified Coptic version of late antique and Byzantine Christian art. From the 16th century, Roman Catholic church art and European art in general began to exert some influence. However, Ethiopian art is highly conservative and retained much of its distinct character until modern times. The production of illuminated manuscripts for use continued up to the present day.[69]

Another important form of Ethiopian art, also related to Coptic styles, is crosses made from wood and metal.[70][71] They are usually copper alloy or brass, plated (at least originally) with gold or silver. The heads are typically flat cast plates with elaborate and complex openwork decoration. The cross motif emerges from the decoration, with the whole design often forming a rotated square or circular shape, though the designs are highly varied and inventive. Many incorporate curved motifs rising from the base, which are called the "arms of Adam". Except in recent Western-influenced examples, they usually have no corpus, or figure of Christ, and the design often incorporates numerous smaller crosses. Engraved figurative imagery has sometimes been added. Crosses are mostly either processional crosses, with the metal head mounted on a long wooden staff, carried in religious processions and during the liturgy, or hand crosses, with a shorter metal handle in the same casting as the head. Smaller crosses worn as jewellery are also common.

Ethiopia has great ethnic and linguistic diversity, and styles in secular traditional crafts vary greatly in different parts of the country. There is a range of traditions in textiles, many with woven geometric decoration, although many types are also usually plain. Ethiopian church practices make great use of colorful textiles, and the more elaborate types are widely used as church vestments and as hangings, curtains, and wrappings in churches, although they have now largely been supplanted by Western fabrics. Examples of both types can be seen in the picture at the top of the article. Icons may normally be veiled with a semi-transparent or opaque cloth; very thin chiffon-type cotton cloth is a speciality of Ethiopia, though usually with no pattern.

Colorful basketry with a coiled construction is common in rural Ethiopia. The products have many uses, such as storing grains, seeds, and food and being used as tables and bowls. The Muslim city of Harar is well known for its high-quality basketry,[72] and many craft products of the Muslim minority relate to wider Islamic decorative traditions.

Tanzania

[edit]

Art from Tanzania is known for paintings by modern artists like Tinga Tinga or George Lilanga, and for traditional as well as modern Makonde sculptures. Like in other regions, there is also a diversified tradition of producing textile art.[10]

Tinga Tinga art has roots in decorating hut walls in central and south Tanzania. It was first in 1968 when Edward Said Tingatinga started to paint on wooden sheets with enamel colours that Tinga Tinga art became known. The art of the Makonde must be subdivided into different areas. The Makonde are known as master carvers throughout East Africa, and their statuary can be found being sold in tourist markets and museums alike. They traditionally carve household objects, figures, and masks. Since the 1950s, the so-called Modern Makonde Art has been developed. An essential step was the turning to abstract figures, mostly spirits (Shetani) that play a special role. Makonde are also part of the important contemporary artists of Africa today. An outstanding position is taken by George Lilanga.

Central Africa

[edit]Democratic Republic of Congo

[edit]Kuba Kingdom

[edit]The Kuba Kingdom (also rendered as the Kingdom of the Bakuba, Songora or Bushongo) was a pre-colonial kingdom in Central Africa. The Kuba Kingdom flourished between the 17th and 19th centuries in the region bordered by the Sankuru, Lulua, and Kasai rivers in the south-east of the modern-day Democratic Republic of the Congo. A great deal of the art was created for the courts of chiefs and kings and was extensively decorated, incorporating cowrie shells and animal skins (especially leopard) as symbols of wealth, prestige and power. Masks are also important to the Kuba. They are used both in the rituals of the court and in the initiation of boys into adulthood, as well as at funerals.

-

Ngady-Mwash mask; 19th century; Ethnological Museum of Berlin (Germany). The colors, red, brown & beige create a warm atmosphere of a savanna, in contrast with the rows of blue beads. Like many other Kuba masks, this one is decorated with cowrie shells. Like many Kuba types of masks, the ngady-mwash mask is extensively polychromed, or multicolored.

-

Mulwalwa mask; 19th or early 20th century; painted wood and raffia; Ethnological Museum of Berlin. This mask embodies a powerful nature spirit. As there are no holes through which a performer could see, it was probably mounted on a wall at an initiation camp, signaling that the initiation was almost complete.

-

Pwoom Itok mask; late 19th century; 39.1 x 28.6 x 29.8 cm (153⁄8 x 111⁄4 x 113⁄4 in.); Brooklyn Museum (USA). This mask may have represented a wise older man at boys' initiations. One of the principal Kuba dance masks is called pwoom itok. The chief identifying characteristic is the shape of the eyes, whose centers are cones surrounded by holes through which the wearer sees.

-

Belt (Yet); possibly early 1900s; cord, leather, glass beads, shells; Cleveland Museum of Art (USA). Like some of the masks, this belt is decorated with colorful beads.

-

Ndop of King Mishe miShyaang maMbul; 1760–1780; wood; 49.5 x 19.4 x 21.9 cm (191⁄2 x 75⁄8 x 85⁄8 in.); Brooklyn Museum (New York City). Ndops are royal memorial portraits carved by the Kuba people of Central Africa. They are not naturalistic portrayals but are intended as representations of the king's spirit and as an encapsulation of the principle of kingship.

-

Head goblet (Mbwoongntey); 19th century; wood; Brooklyn Museum. It has a one-inch cylindrical lip with linear decoration. The hair is made up of crosshatched lines with a raised diamond-shaped segment on the back of the head. Its cheeks have curved multilinear scarification.

-

Itoon (diviner's instrument, in form of a hippopotamus); 19th century; wood; 7.5 × 26.6 × 6.4 cm (215⁄16 × 101⁄2 × 21⁄2 in.); Brooklyn Museum

-

Cloth; raffia; 20.3 x 85.7 cm (8 x 333⁄4 in.); Brooklyn Museum. In Kuba culture, men are responsible for raffia palm cultivation and the weaving of raffia cloth.[73] Several types of raffia cloth are produced for different purposes, the most common form of which is a plain woven cloth that is used as the foundation for decorated textile production.

Luba Kingdom

[edit]The Kingdom of Luba or Luba Empire (1585–1889) was a pre-colonial Central African state that arose in the marshy grasslands of the Upemba Depression in what is now the southern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Today, the Luba people or baLuba are an ethno-linguistic group indigenous to the south-central region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[74] The majority of them live in this country, residing mainly in its Katanga, Kasai, and Maniema provinces.

As in the Kuba Kingdom, the Luba Kingdom held the arts in high esteem. A carver held a relatively high status, which was displayed by an adze (axe) that he carried over his shoulder. Luba art was not very uniform because of the vast territory the kingdom controlled. However, some characteristics are common. The prominent role of women in creation myths and political society resulted in many objects of prestige being decorated with female figures.

-

Headrest; 19th century; wood; height: 18.5 cm (7.3 in), width: 19 cm (7.5 in), thickness: 8 cm (3.1 in); Musée du quai Branly (Paris). This headrest presents 19th century Luba hairstyles, as well as the long limbs, bent-back legs, cylindrical torso and dynamic pose typical of the artist who made it.

-

Figurine of a standing woman; late 19th or early 20th century; wood; 27.9 × 8.3 × 10.2 cm (11 × 31⁄4 × 4 in.); Brooklyn Museum (New York City)

-

Heddle pulley with female head; late 19th or early 20th century; wood; 20.6 × 5.4 × 4.8 cm (81⁄8 × 21⁄8 × 17⁄8 in); Brooklyn Museum

-

Kifwebe mask; wood; Royal Museum for Central Africa (Tervuren, Belgium)

Other ethnic groups of Democratic Republic of Congo

[edit]-

Anthropomorphic pot; early 20th century; pottery; 40.0 × 24.0 cm (153⁄4 × 91⁄2 in.); by Mangbetu people; Brooklyn Museum (New York City)

-

Plank mask (emangungu); possibly early 1900s; wood; by Bembe people; Cleveland Museum of Art (USA)

-

Head of a scepter; 19th century; by Yombe people

-

Female figure; 20th century; wood; by Lumbo people; Indianapolis Museum of Art (USA)

-

Mask; early 20th century; wood, raffia & color pigments; by Yaka people; Rietberg Museum (Zürich, Switzerland)

-

Chair (throne) of a chief; 19th or early 20th century; wood; by Hemba people; Rietberg Museum

-

Funerary figure (tumba); 19th century; wood; by Sundi people; Rietberg Museum

-

Mbangu mask; wood, pigment & fibres; height: 27 cm; by Pende people; Royal Museum for Central Africa. Representing a disturbed man, the hooded V-looking eyes and the mask's artistic elements – face surfaces, distorted features, and divided colour – evoke the experience of personal inner conflict

-

Tomb figure; soapstone; by Boma people; Royal Museum for Central Africa. Stone sculptures are extremely rare in African art

-

Warrior ancestor figure; 19th century; wood; 84.1 cm × 26 cm × 23.2 cm (33.1 in × 10.2 in × 9.1 in); by Hemba people; Kimbell Art Museum (Fort Worth, Texas, USA)

-

Statuette of a woman; 19th century or early 20th century; by Holoholo people; Ethnological Museum of Berlin (Germany)

Chad

[edit]Sao

[edit]The Sao civilization, which existed in Middle Africa from circa the 6th century BC to as late as the 16th century AD, lived by the Chari River around Lake Chad in territory that later became part of Cameroon and Chad. Their most significant artworks include terracotta figurines representing humans and animals. Other artifacts show that the Sao were skilled workers in bronze, copper, and iron.[75]

-

Anthropomorphic figurine; terracotta; 9th-16th century; Musée du quai Branly (Paris)

-

Anthropomorphic figurine; 9th-16th century; terracotta; Musée du quai Branly

-

Anthropomorphic figurine; 9th-16th century; terracotta; Musée du quai Branly

-

Anthropomorphic figurine; 9th-16th century; terracotta; Musée du quai Branly

-

Head; terracotta; Muséum d'Histoire naturelle de La Rochelle (La Rochelle, France)

-

Zoomorphic figure; 9th-16th century; terracotta; Musée du quai Branly

-

Fragment of a pectoral; 9th-16th century; cuprous alloy; Musée du quai Branly

Gabon

[edit]

The Fang people create masks, basketry, carvings, and sculptures. Fang art is characterized by clarity of form and distinct lines and shapes. Bieri, boxes for holding ancestral remains, are carved with protective figures. Masks with faces painted white with black features are worn in ceremonies and for hunting. Myene art centers on rituals for death. Female ancestors are represented by white-painted masks worn by male relatives. The Bekota use brass and copper to cover their carvings and use baskets to hold ancestral remains. Compared to some other African countries, Gabon has less tourism, and its art production is less driven by commerce.

Southern Africa

[edit]Botswana

[edit]In the northern part of Botswana, women in the villages of Etsha and Gumare[76] are noted for their skill at crafting baskets from Mokola Palm and local dyes. The baskets are generally woven into three types: large, lidded baskets used for storage; large, open baskets for carrying objects on the head or for winnowing threshed grain; and smaller plates for winnowing pounded grain. The artistry of these baskets is being steadily enhanced through color use and improved designs as they are increasingly produced for commercial use.

The oldest evidence of art in the region consists of ancient paintings from both Botswana and South Africa. Depictions of hunting and both animal and human figures, made by the San people and dating back more than 20,000 years, are found within the Kalahari desert.

Zimbabwe

[edit]The culture of Great Zimbabwe is known for its buildings and sculptures, including the eight soapstone Zimbabwe Birds. These appear to have had a special significance and were presumably mounted on monoliths. Modern Zimbabwean sculptors in soapstone have achieved international success. Southern Africa's oldest known clay figures date from 400 to 600 AD and have cylindrical heads with a mixture of human and animal features.

South Africa

[edit]Mapungubwe

[edit]

The Kingdom of Mapungubwe (1075–1220) was a pre-colonial state in Southern Africa located at the confluence of the Shashe and Limpopo rivers, south of Great Zimbabwe. The most famous Mapungubwe artwork is a tiny golden rhino, known as the Golden Rhinoceros of Mapungubwe. In other graves from Mapungubwe, objects made of iron, gold, copper, ceramic, and glass beads were found.

Southern Ndebele

[edit]The Southern Ndebele people are famous for the way they paint their houses. Distinct geometric forms against stark, contrasting colors form the basis of the Ndebele style, which encompassed the architecture, clothing, and tools of the people. While color has almost always had a role in drawing emotions in art, the Ndebele were one of the first Southern African tribes to utilize a wide array of colors to convey specific meanings in their daily lives.

-

Murals in the Ndebele style from the Maastricht University (the Netherlands)

-

Murals in the Ndebele style from the Maastricht University

-

A beaded apron or meputo; late 19th-early 20th century; hide, glass beads, metal beads, straw; 46.9 cm × 50.8 cm (18.5 in × 20.0 in); Birmingham Museum of Art (Alabama, USA)

North Africa

[edit]Art in many African traditions often carries symbolic meaning related to community values, ancestral reverence, or spiritual beliefs. For example, masks may represent spirits or deities, and sculptures can symbolize fertility, protection, or wisdom.

Rock Art and Prehistoric Art:

North Africa's artistic heritage dates back to prehistoric times, evidenced by rock art in the Sahara Desert. Sites like Tassili n'Ajjer in Algeria feature thousands of petroglyphs and paintings, depicting animals, hunting scenes, and daily life from as far back as 10,000 BCE. These works reflect the relationship between early humans and their environment.

Egypt

[edit]Persisting for 3,000 years and thirty dynasties, the "official" art of Ancient Egypt centered on the state religion. The art ranged from stone carvings of both massive statues and small statuettes to wall art that depicted both history and mythology. In 2600 BC, the maturity of Egyptian carving reached a peak that was not surpassed for another 1,500 years, until the reign of Ramesses II.[77]

Much of the art possesses a certain stiffness, with figures poised upright and rigid in a regal fashion. Bodily proportions also appear to be mathematically derived, giving rise to a sense of idealized perfection in the figures depicted. This was likely used to reinforce the godliness of the ruling caste.

-

Both sides of the Narmer Palette; circa 3100 BC; greywacke; height: 63 cm (243⁄4 in.); from Hierakonpolis (Egypt); Egyptian Museum (Cairo). The Narmer palette is the quintessential statement of the Egyptians' mythology of kingship. A clear manifesto of royal power, it is also one with multiple layers of symbolism.

-

A guardian statue which reflects the facial features of the reigning king, probably Amenemhat I or Senwosret I, and which functioned as a divine guardian for the imiut. Made of cedar wood and plaster c. 1919–1885 BC[78]

-

Stele of Princess Nefertiabet eating; 2589-2566 BC; limestone & paint; height: 37.7 cm (147⁄8 in.), length: 52.5 cm (205⁄8 in.), depth: 8.3 cm (31⁄4 in.); from Giza; Louvre (Paris). This finely executed relief represents the most succinct assurance of perpetual offering for the deceased.

-

The Bust of Nefertiti; 1352-1336 BC; limestone, plaster & paint; height: 48 cm (197⁄8 in.); from Amarna (Egypt); Egyptian Museum of Berlin (Germany). Perhaps the most iconic image of a woman from the ancient world, the Bust of Nefertiti is difficult to contextualize because it seems so exceptional.

-

The Mask of Tutankhamun; circa 1327 BC; gold, glass and semi-precious stones; height: 54 cm (211⁄4 in.), width: 39.3 cm (151⁄2 in.), depth: 49 cm (191⁄4 in.); from the Valley of the Kings (Thebes, Egypt); Egyptian Museum. The mummy mask of Tutankhamun is perhaps the most iconic object to survive from ancient Egypt.

Nubia and Sudan

[edit]The people of Nubia, living in southern Egypt and the northern region of Sudan, developed historical art styles similar to those of their Egyptian neighbors to the north. However, Nubian art was not merely a product of colonization by ancient Egypt, but was also the result of a mutual exchange of ideas and ideologies along the Nile Valley. The earliest art of the region comes from the Kerma culture, which was contemporary to the Old and Middle Kingdom of Egypt. Art from this period exhibits Egyptian faience alongside the distinct black-topped pottery of Nubian origin. In the later Napatan period of the Kingdom of Kush, art showed more influence from Egypt as the people in the region worshiped Egyptian gods.[79][80]

After these historical periods, the inhabitants of Sudan created artworks in different styles, both in indigenous African ways and influenced by Byzantine Christian, Islamic, and modern art traditions.[81]

African Diaspora

[edit]Museums

[edit]

Many art and ethnographic museums have a section dedicated to the art from Sub-Saharan Africa, such as the British Museum, Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac in Paris, Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Ethnological Museum of Berlin. Not many Western museums are dedicated only to African art, like the Africa Museum in Brussels, National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C., and African Art Museum of Maryland in Columbia, Maryland.[82] Some colleges and universities hold collections of African art, like Howard University in Washington, DC and Spelman College in Atlanta, Georgia.

Nearly all countries in Africa have at least a national museum housing African art, often very largely from that country, such as the Sierra Leone National Museum and Nigerian National Museum in Lagos. There are also many smaller museums in the provinces.

The display of African art and artifacts in European museums has long been controversial in various ways, and the French-commissioned "Report on the restitution of African cultural heritage" (2018) has marked a key moment, leading to an increase in the return of artifacts. However, there are other examples, such as the Museum of African Art in Belgrade which was opened in 1977 because of Yugoslavia's relations with many African countries thanks to the Non-Aligned Movement. The museum was opened out of the desire to acquaint the people of Yugoslavia with the art and culture of Africa since there was a deeply rooted notion about Yugoslavia sharing a friendship with African countries thanks to their similar struggles; all of the original items in the museums were legally bought by the Yugoslav ambassador and journalist Zdravko Pečar and his wife Veda Zagorac, while more recent acquisitions were either bought by the museum, received as gifts from Yugoslavs who lived in Africa, or were diplomatic gifts to the museum by the ambassadors of African countries.[83]

The Congolese activist Mwazulu Diyabanza has taken direct action against European museums to take back items he says belong to Africa.[84][85]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Fortenberry, Diane (2017). The Art Museum. Phaidon. pp. 309, 314. ISBN 978-0-7148-7502-6.

- ^ Suzanne Blier: "Africa, Art, and History: An Introduction", A History of Art in Africa, pp. 15–19

- ^ a b Lawal, Babatunde (2005). "Art and architecture, History of African". In Shillington, Kevin (ed.). Encyclopedia of African History. Fitzroy Dearborn. ISBN 1-57958-245-1.

- ^ Ross, Emma George (October 2002). "African Christianity in Ethiopia". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ Kino, Carol (2012-10-26). "When Artifact 'Became' Art". The New York Times. Retrieved 2014-12-12.

- ^ Breunig, Peter (2014), Nok: African Sculpture in Archaeological Context, Frankfurt: Africa Magna Verlag, ISBN 978-3-937248-46-2.

- ^ a b Mitchell, Peter and Lane, Paul (2013) The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology. Oxford University Press. p. 375. ISBN 0191626147

- ^ a b Henshilwood, Christopher S.; et al. (2011). "A 100,000-Year-Old Ochre-Processing Workshop at Blombos Cave, South Africa". Science. 334 (6053): 219–222. Bibcode:2011Sci...334..219H. doi:10.1126/science.1211535. PMID 21998386. S2CID 40455940.

- ^ a b McBrearty, Sally; Brooks, Allison (2000). "The revolution that wasn't: a new interpretation of the origin of modern human behavior". Journal of Human Evolution. 39 (5): 453–563. Bibcode:2000JHumE..39..453M. doi:10.1006/jhev.2000.0435. PMID 11102266.

- ^ a b Honour & Fleming, 557

- ^ a b c Murrell, Denise. "African Influences in Modern Art", The Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2008. Retrieved on 31 January 2013.

- ^ Mark, Peter (1999). "Is There Such a Thing as African Art?". Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University. 58 (1/2): 7–15. doi:10.2307/3774788. JSTOR 3774788.

- ^ Honour & Fleming, 556–561

- ^ Vangheluwe, S.; Vandenhoute, J. (2001). The Artist Himself in African Art Studies: Jan Vandenhoute's Investigation of the Dan Sculptor in Côte D'Ivoire. Academia Press. p. 19. ISBN 9789038202860. Retrieved 2014-12-12.

- ^ Suzanne Blier, "Africa, Art, and History: An Introduction", A History of Art in Africa, p. 16

- ^ Art of central Africa Retrieved 28 April 2022

- ^ "The Use of Haematite, Tiger's Eye Stone and Ebony Wood for African Jewelry". Squinti African Art. Archived from the original on 2012-01-19. Retrieved 2012-01-15.

- ^ "What is African Art". Squinti African Art. Archived from the original on 2012-01-19. Retrieved 2012-01-15.

- ^ "African Art and Architecture". Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia. Chicago: World Book, Inc. 30 September 2021. Retrieved 11 December 2023 – via EBSCOhost.

- ^ Olupọna, Jacob J. (2014-01-09), "5. Sacred arts and ritual performances", African Religions, Oxford University Press, pp. 72–88, doi:10.1093/actrade/9780199790586.003.0005, ISBN 978-0-19-979058-6, retrieved 2024-10-06

- ^ "Purpose and Meaning of ART". The Sunday News. 29 September 2019. Archived from the original on 2022-06-07.

- ^ Bourdillon, Michael F. C. (10 March 1975). "Themes in the Understanding of Traditional African Religion". Journal of Theology for Southern Africa. University of KwaZulu-Natal: 37–50. ISSN 0047-2867 – via EBSCOhost (indexed in Atla Religion Database).

- ^ Yong, Ed (15 March 2018). "A Cultural Leap at the Dawn of Humanity - New finds from Kenya suggest that humans used long-distance trade networks, sophisticated tools, and symbolic pigments right from the dawn of our species". The Atlantic. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ ""New" Giraffe Engravings Found". The 153 Club. Archived from the original on 12 June 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-31.

- ^ a b Breunig (2014). Nok: African Sculpture in Archaeological Context. Africa Magna Verlag. p. 21. ISBN 9783937248462.

- ^ Pietz, William (March 1985). "The Problem of the Fetish, I". Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics. 9: 5–17. doi:10.1086/resv9n1ms20166719. ISSN 0277-1322.

- ^ Strother, Z. S. (2011). À la recherche de l’Afrique dans Negerplastik de Carl Einstein. Gradhiva, 14: 30–55. link.

- ^ Mashabane, Phill (2018). "Africanism in art and architecture: The keynote address delivered at the twelfth annual conference of the South African Journal of Art History". South African Journal of Art History. 33 (3): iv-vii.

- ^ Richardson, John (2007). A Life of Picasso: The Cubist Rebel, 1907–1916. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-71150-3.

- ^ Kampen-O'Riley, Michael (2013). Art beyond the West: the arts of the Islamic world, India and Southeast Asia, China, Japan and Korea, the Pacific, Africa, and the Americas (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River. ISBN 9780205887897. OCLC 798221651.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ross, Doran H. (April 1994). "Coffins With Style". Faces. Vol. 10, no. 8. Cricket Media. p. 33. ISSN 0749-1387 – via EBSCOhost MAS Ultra: School Edition.

- ^ "Joseph Bertiers, Kenya". AFRICANAH.ORG. 2016-09-04. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- ^ Extreme Canvas 2 : The Golden Age of Hand-Painted Movie Posters from Ghana. Wolfe III, Ernie (1st ed.). [Los Angeles, CA]: Kesho & Malaika Press. 2012. ISBN 978-0-615-54525-7. OCLC 855806853.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Brown, Ryan Lenora (2016-02-04). "How Ghana's Gory, Gaudy Movie Posters Became High Art". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- ^ "people - Sharjah Art Foundation". sharjahart.org. Archived from the original on 2018-11-26. Retrieved 2018-11-26.

- ^ "Transatlantic Dialogue". africa.si.edu. Retrieved 2018-11-26.

- ^ "Kente Cloth: History, Meaning, Symbolism, and Applications". Stoles.com. 2023-02-25. Retrieved 2024-10-06.

- ^ Kowalski, Jeff Karl (July–August 2018). "Symbols of the Asante Kingdom". Dig into History. Vol. 20, no. 6. Cricket Media. pp. 18–21. ISSN 1539-7130 – via EBSCOhost MasterFILE Premier.