Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nafir

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2022) |

Moroccan brass nafīr. Length 110 centimeters, before 1978. | |

| Brass instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | būq al-nafīr[1] nefir (Turkish spelling) |

| Classification | Brass |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 423.121 (Natural trumpets – There are no means of changing the pitch apart from the player's lips; end-blown trumpets – The mouth-hole faces the axis of the trumpet.) |

| Inventor(s) | Earliest known are Egyptian. Greek and Etruscan trumpets from antiquity passed through Romans to Persians. Possibly a Middle East Assyrian tradition as well. |

| Developed | Persian Empire and Arab conquerors spread instrument to India, China, Malaysia, Africa and Andalusia. Wars between Europe and Islamic powers brought horn to Europe. Europeans changed horn by bending it into compact forms, which reinfluenced Islamic world. |

| Related instruments | |

|

Straight tube Bent tube

| |

| Sound sample | |

|

| |

Nafir (Arabic نَفير, DMG an-nafīr), also nfīr, plural anfār, Turkish nefir, is a slender shrill-sounding straight natural trumpet with a cylindrical tube and a conical metal bell, producing one or two notes. It was used as a military signaling instrument and as a ceremonial instrument in countries shaped by Islamic culture in North Africa, the Middle East and South Asia. In Ottoman, Persian and Mugulin miniatures, the nafīr is depicted in battle scenes. In Christian culture, it displaced or was played alongside of the curved tuba or horn, as seen in artwork of about the 14th century A.D.

Similar straight signal trumpets have been known since ancient Egyptian times and among the Assyrians and Etruscans. After the fall of the Roman Empire, the straight-tubed Roman tuba continued to flourish in the Middle East among the Sassanids and their Arabic successors. The Saracens, whose long metal trumpets greatly impressed the Christian armies at the time of the Crusades, were ultimately responsible for reintroducing the instrument to Europe after a lapse of six hundred years. The straight trumpet type, called añafil in Spanish, also entered medieval Europe via medieval al-Andalus.

From the Middle Ages to the early 20th century, the nafīr and the straight or S-curved, conical metal trumpet kārna belonged to the Persian military bands and representative orchestras (naqqāra-khāna), which were played in Iran, India (called naubat) and were common as far as the Malay Archipelago (nobat).[2] In the later Ottoman military bands (mehterhâne), the straight nafīr was distinguished from the twisted trumpet boru in which the straight tube was bent into a loop, influenced by such European instruments as the clarion.

The instruments retain ceremonial functions today in Morocco (nafīr played in the month of Ramadan), Nigeria (kakaki played in Ramadan), and Malaysia (as a representative instrument of the sultanates the silver nafiri in the nobat orchestra). Its cousin the Karnay is similarly used in Iran, Tajikistan Uzbekistan and Rajistan, and the Karnal in Nepal.

Nafir versus karnay

[edit]The nafir has been compared to another trumpet, the karnay. The two may possibly have been the same instrument.[3] However, today a difference can be stated in terms of the instruments' dimensions. The karnay in Tajikistan which reaches 190–210 cm in length tends to have a larger diameter, about 3.3 centimeters.[4]

The nafir in Morocco averages 150 centimeters in length and a diameter of 1.6 cm on the outside of the tube.[5] According to the Persian music theorist Abd al-Qadir Maraghi (bin Ghaybi, c. 1350–1435), the nafīr was 168 centimeters (two gaz) long.[6]

The difference is visible in miniatures, with artists depicting some instruments thinner. Also visible in miniatures is the gradually increasing the bore size (conically), which some karnays have in the same way a Tibetan horn does.[7]

The Arabic nafīr was probably mostly a long, cylindrical metal trumpet with a high-pitched sound better suited to signaling than the deeper, duller sound of the conical trumpets such as the karna.[6] The tonal difference was illustrated in the vocabulary of the Iraqi historian Ibn al-Tiqtaqa (1262–1310), according to which the nafīr player "shouted out" (sāha) the trumpet, while the player of the conical trumpet, here referred to as a būq, "blew" (nafacha).[6] A writer in 1606, Nicot, said the trumpet was treble when compared with other trumpets that only played tenor and bass.[8]

Another confused point about karna versus nafirs concerns S-curved trumpets. Abd al-Qadir al-Maraghi described the karnā as curved in an S-shape out of two semicircles which are turned towards each other in the middle - like today's sringa in India.[6] However, unlike the sringa, the S-curve karna could be very long.[6]

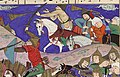

The S-curved instrument was identified as a karrahnāy (or karnay) by ʿAbdalqādir ibn Ġaibī (died 1435).[9] It is often paired with a slender straight trumpet in miniatures. Miniatures that show the karrahnāy and nafir together show that the karrahnāy was also slim, unlike the sringa.

-

Musicians advance behind Emperor Humayun defeating the Afghans. One straight-tubed nafir trumpet, one S-curved karnay.

Origin

[edit]In Arabic, būq is a term used for conical horns, whether curved or straight and regardless of the construction material, including shell, bone, ivory, wood and metal.[10][11] This is important because in Islamic areas, būq could mean a number of different instruments, including the būq al-nafir (horn of battle).[11]

Conical horns have been common across many unassociated cultures, but the straight cylindrical tubed instruments had a narrow range of users who had ties to one another; the Greeks, Egyptians and Romans interacted, as did the Egyptians and Assyrians and the Arabs, Persians, Turkmen and Indians all of whom had the cylindrical straight tubed trumpet, before it was further developed by medieval and early Renaissance Europeans.

Earliest trumpets and horns

[edit]Trumpet instruments originally consisted either of relatively short animal horns, bones and snail horns or of long, rather cylindrical tubes of wood and bamboo. [12]

The former and their later replicas made of wood or metal (such as the Northern European Bronze Age lur) are attributed to the natural horns, while Curt Sachs (1930) suspected the origin of today's trumpets and trombones to be the straight natural trumpets made of bamboo or wood.[13]

Egypt, Assyria, Rome, Greece, Israel

[edit]The simple straight trumpets are called tuba-shaped, derived from the tuba used in the Roman Empire. Other straight trumpets in antiquity were the Etruscan-Roman lituus and the Greek salpinx.

Tuba-shaped trumpets have been around since the mid-3rd millennium BC. known from illustrations from Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt. According to written records, they were blown as signaling instruments in a military context or as ritual instruments in religious cults. As has been demonstrated with the ancient Egyptian sheneb, of which two specimens survive in good condition from the tomb of Tutankhamen (ruled c. 1332–1323), the long trumpets produced only one or two notes and were not built to sustain the pressure that a very high third note would produce.[14][15]

Among the early ritual instruments mentioned in the Old Testament is the curved ram's horn, the shofar, and the straight metal trumpet chazozra (hasosrah) made of hammered silver sheet.[16] In the Hebrew Bible, qeren also stands for an animal horn, which is used in different ways, but only in one place (Josh 6:5 EU) for a horn blown to produce sound. Queren is rendered in the Aramaic translations of the Bible (Targumim) with the etymologically derived qarnā, which later appears in the Book of Daniel (written 167–164 BC) as a musical instrument (trumpet made of clay or metal). In the (Septuagint) Greek Bible, the original animal horn qarnā is rendered salpinx and in the Latin Vulgate tuba, thus reinterpreting it as a straight metal trumpet.[17] The word qarnā becomes karnā in the medieval Arabic texts for a straight or curved trumpet with a conical tube (for the exact origin of the ancient trumpets see there).

In ancient times, war and ritual trumpets were widespread throughout the Mediterranean region and from Mesopotamia to South Asia. Like the chazozra of the Hebrews, these trumpets could only be blown by priests or by a select group of people. The Romans knew from the Etruscans the circularly curved horn cornu with a cup-shaped mouthpiece made of cast bronze and a stabilizing rod running across the middle. In the Roman Empire (27 BC – 284 AD), the Romans introduced a variant of the cornu with a narrower tube in the shape of a G in the military bands. This is pictured as a relief on Trajan's Column. The length of the tube could be up to 330 centimeters. The straight cylindrical tuba, which is around 120 centimeters long in the depictions, had a greater influence on posterity than this curved wind instrument. In the Loire Valley, which belonged to Roman Gaul, two celtic long trumpets with cylindrical bronze tubes that could be dismantled into several parts were excavated.[19]

In late Roman times, a trumpet bent in a circle like the cornu was called a bucina. The difference between the straight and curved trumpets was presumably less in form than in use. While cornu and tuba were blown on the battlefield, the bucina presumably served as a signal trumpet in the camp, for example at the changing of the guard.[20]

Curved trumpets and horns and hornpipes may fit into a horn tradition, with the instruments curving as animal horns, much as the Roman bucina. After the fall of the Roman Empire, the tubular trumpet (made from sheet metal) was lost to Europe.[21] The technology to bend metal tubes was also lost until the problem was re-addressed by Europeans in about the early 15th century, when illustrations began to appear of trumpets with curves.[22][21][23]

After the reinvention of a metal-tube-bending technology, European trumpets began to use it, and instruments were able to have longer and thinner tubes (bent compactly),[22] creating a huge line of brass instruments, including the clarion trumpet. The bent tube instruments moved into Persian and Turkish countries and to India, becoming the boru in Turkish, showing up in artwork in the 15th and 16th centuries.[21]

The Latin bucina has been connected to the names used for a variety of unrelated horns and trumpets, including the albogue (a "horn pipe" in Spain), buki in Georgia and bankia in India (a regional name of the S-shaped curved trumpet, which includes shringa, ransingha, narsinga and kombu).[1]

Persians, Arabs, Islam

[edit]The history of mounted military musicians begins with the Persian Sassanids (224–651), who banged kettledrums on elephants imported from India. Apart from little reliable evidence for the use of war elephants in the 3rd century, the sources indicate that the Sassanids used elephants in the fight against the Roman army and against the Armenians from the 4th century under Shapur II (ruled 309–379).[25] The Sassanids also used trumpets to call the start of battle and the troops to order. In the Persian national epic Shahnameh, trumpet players and drummers are mentioned who acted in the battles against the Arabs at the beginning of the 7th century on the backs of elephants. Possibly Firdausi took over the situation in his time, for which mounted war musicians are otherwise documented, in the historical account.[26]

The Fatimids maintained huge representative orchestras with trumpet players and drummers. The Fatimid Caliph al-ʿAzīz (r. 975–996) invaded Syria from Egypt in 978 with 500 musicians blowing bugles (abwāq or būqāt, singular būq).[27] In 1171 Saladin resigned the successor of the last Fatimid caliph. During his time as Sultan of Egypt (until 1193), the historian Ibn at-Tuwair († 1120) wrote about the parade of a representative Fatimid orchestra at the end of the 11th century, which included trumpeters and 20 drummers on mules. Each drummer played three double-headed cylinder drums (t'ubūl ) mounted on the animals' backs, while the musicians marched in pairs.[28] The musical instruments of these orchestras are listed by the Persian poet Nāsir-i Chusrau (1004 – after 1072): trumpet būq (according to Henry George Farmer, a twisted trumpet, clairon), double - piped ball instrument surnā, drum tabl, tubular drum duhul (in India dhol ), kettledrum kūs, and cymbals kāsa.[27] According to the Arab historian Ibn Chaldūn (1332–1406), the musical instruments mentioned were still unknown in early Islamic times. Instead, the square frame drum duff and the reed instrument mizmar (zamr) were used in military. During the rule of the Abbasids (750–1258) larger military orchestras were introduced, which also had ceremonial functions and performed alongside surna and tabl contained the long metal trumpet būq an-nafīr, the kettle drum dabdāb, the flat kettle drum qas'a and the cymbals sunūj (singular sindsch).[29] Arabic authors in the late Abbasid period distinguished brass instruments between the coiled trumpet būq and the straight nafīr. The woodwind instruments of the time included the reed instrument mizmar, the doubled reed instrument zummara, the cone oboe surnā, the longitudinal flutes made of reed (ney and shababa) as well as the fission flute qasaba.[30]

A miniature illustrated by Yahya ibn Mahmud al-Wasiti for the Maqāmāt by the Arabic poet al-Hariri (1054–1122) in a manuscript from 1237 shows an Arabic military band with flags and standards in the depiction of the 7th Maqāma. Typical of similar paintings from the 13th century are the paired, largely cylindrical long trumpets nafīr and the pair of kettledrums naqqāra. The size of the military orchestra subordinate to them was measured according to the ruler's power. A typical large orchestra consisted of about 40 musicians, who, in addition to kettle drums (small naqqārat, medium-sized kūsāt and large kūrgāt), cylinder drums (tabl), cylindrical trumpets (nafīr) and conical trumpets (būq), cymbals (sunūj), gongs (tusūt) and bells (jalajil).[32]

Another type of trumpet, with a short cylindrical tube, is shown in a Persian miniature in a late fourteenth-century manuscript. The manuscript contains the cosmography ja'ib al-machlūqāt ("Wonders of Creation") written by Zakariya al-Qazwini (1203–1283). The Muslim angel Isrāfīl, who appears as a herald of the Day of Resurrection similar to the Christian archangel Gabriel, blows his trumpet for the Last Judgment. The two spherical ridges on the trumpet are the junctions of the mouthpiece, tube and funnel-shaped bell.[33] They resemble the thickenings on the pipe in Germany and France introduced in the military trumpet busine (French buisine) in the 13th century.[34] As a possible early precursor of this nafīr type, Joachim Braun (2002) mentions the depiction of two short wind instruments with funnel-shaped bells on an Israelite bar kokhba coin minted between 132 and 135 AD. According to Braun, the unclearly designed thickenings at the upper end of these instruments could also refer to reed instruments.[35]

Name

[edit]

The Arabic instrument name nafīr was first mentioned in the 11th century.[36]

It stands for "‘trumpet’, ‘pipe’, ‘flute’, ‘sound’ or ‘noise’, and also as ‘men in flight’ or ‘an assembly of men for warlike or political action.’".[37]

The original meaning of nafīr was the "call to war"[6] Hence the military trumpet was called būq al-nafīr.[6]

Nafir was also part of a military term in 19th century Persia for all troop members to assemble (nafīr-nāma).[38]

Nafīr goes back to the Semitic root np-Ḥ with the context of meaning "to breathe" and this is via the common Proto-Indo-European root sn-uā- (derived from this also "snort, snort") connected to the ancient Egyptian šnb (sheneb).[39]

The word nafīr and the long trumpet so referred to spread with Islamic culture in Asia, North Africa and Europe. Even before the First Crusade (1096–1099), the Seljuk Turks brought the nafīr along with other military musical instruments westward as far as Anatolia and the Arab countries in the course of their conquests.[40] In the Arabic version of the tale One Thousand and One Nights, the nafīr occurs only in one passage as a single trumpet, played together with horns (būqāt), cymbals (kāsāt), reed instruments (zumūr) and drums (tubūl) at the head of the army going to war.[41]

In the Ottoman Empire, the nefīr was part of the instruments of military bands (mehterhâne) and its player was called nefīri.[42] Ottoman Sultan Mustafa III (reigned 1757–1774) had volunteers assembled before the war against Russia (1768–1774) in a general call to arms called nefīr-i ʿāmm, so as not to be exclusively dependent on the professional army of the janissaries.[42] This was distinguished from the nefīr-i chāss, the military mobilization of a selected group of people.[42]

In today's Turkish, nefir means "trumpet/horn" and "war signal".[37] In military music, the straight natural trumpet nefir is distinguished from the general Turkic word for "tube" and "trumpet," boru.[37] Boru refers to the looped military trumpet (see Clairon), which is due to European influence,[37] while the derived borazan (“trumpeter”) is understood today in Turkish folk music as a spirally wound bark oboe.[43]

In the 17th century, when the Ottoman writer Evliya Çelebi (1611 – after 1683) wrote his travelogue Seyahatnâme, the nafīr was a straight trumpet that was played in Constantinople by only 10 musicians and had fallen behind the European boru (also tūrumpata būrūsī), for which Çelebi states 77 musicians.[44] Nefir, or nüfür in religious folk music, was a simple buffalo horn without a mouthpiece, blown by Bektashi in ceremonies and by itinerant dervishes for begging until the early 20th century.[44]

After the Muslim conquest of al-Andalus, the Spanish adopted the trumpet under the Spanish name añafil, derived from an-nafīr.[3] Other Arabic instruments introduced via the Iberian Peninsula or brought with them by the Crusaders have also entered Spanish with their names, including from tabl (via Late Latin tabornum) the cylindrical drum tabor, from naqqāra the small kettle drum naker (Old French nacaire) and from sunūdsch (cymbals) the Spanish bells sonajas. Henry George Farmer, who emphasized the influence of Arabic on European music in the early 20th century, repeated the 20 instrument names listed by the Andalusian poet aš-Šaqundī († 1231) from Seville,[45] in the Spanish song collection Cantigas de Santa Maria from the second half of the 13th century and the names mentioned in the verses of the poet Juan Ruiz (around 1283 – around 1350), all of Arabic origin. These include laúd (from al-ʿūd, guitarra morisca (“ Moorish guitar”), tamborete, panderete (with Arabic tanbūr related, cf. panduri), gaita (from al-ghaita), exabeba (axabeba, ajabeba, small flute, from shabbaba), rebec (from rabāb), atanbor (drum, from at-tunbūr), albogon (trumpet, from al-būq) and añafil.[46] The word fanfare is probably based on anfār, the plural form of nafīr.[47]

After the disappearance of the large naubat orchestras in Persia and northern India at the beginning of the 20th century, nafīr refers to a long trumpet that still exists in Morocco today. The trumpet was known as nafiri in northern India and as nempiri in China. In Malaysia, the nafiri is still used.[48] In India today, nafiri is one name among many for a short conical oboe.

Distribution

[edit]Europe

[edit]After the end of the Western Roman Empire, curved horns of various sizes and shapes existed, as shown by illustrations, from about the 5th to the 10th century, but hardly any straight trumpets. The mosaic from the apse of the Basilica of San Michele in Africisco in Ravenna, consecrated in 545, depicts seven tuba angels blowing long, slightly curved horns, the shape of which is reminiscent of Byzantine military horns. Similar curved trumpets, light enough for the musician to hold with one hand but considerably longer than animal horns, are depicted in the Utrecht Psalter around 820.[49] The numerous representations of conical curved horns follow from the 10th/11th century again conical straight trumpets after Roman model, which are blown by angels. In the epic heroic poem Beowulf, written in the late 10th or early 11th century, Hygelac, the uncle of the eponymous hero, calls the soldiers to battle with 'horn and bieme'. The Old English bieme, standing for tuba, may have originally denoted a wooden trumpet.[50]

The straight long trumpet with a bell-shaped bell is depicted along with other wind instruments in a manuscript of the Etymologiae of Isidore of Seville from this period.[51] A little later, at the beginning of the 12th century, the wall painting with an Apocalypse cycle was created in the Baptistery of the Cathedral of Novara. The seven tuba angels announce the plagues for the sins committed by humans with long slender trumpets.[52] In the course of the 12th century, further frescoes were created in Italian churches, on which long trumpets with bells are depicted. The frescoes in the abbey church of Sant'Angelo in Formis in Capua are particularly important for the history of musical instruments, because the tuba angels depicted hold straight trumpets with both hands for a very long time, which refers to the influence of Arabic culture after the Norman conquest of Sicily from the Arabs. Under Arabic influence, a trumpet corresponding to the Roman tuba was revived in Europe, which first appeared around 1100 in the Old French Song of Roland under the name buisine.[53] In the Song of Roland, only the nafīr straight trumpet type is referred to as buisine, while the Franks themselves used trumpets shaped as animal horns (corn), the elephant ivory (olifant) and a smaller horn (graisle).[54]

A visible feature of the oriental trumpets were several spherical thickenings (knobs) on the cylindrical tube. A short trumpet with such bulges is depicted on a 12th-century relief on one of the Hindu temples of Khajuraho in northern India. In Europe, this type of trumpet with one to three thickenings and a mouthpiece first appeared in a 13th-century sculpture in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela as well as in the Cantigas de Santa Maria from the second half of the 13th century and in other manuscripts. According to Anthony Baines (1976), this is primarily an Indo-Persian and less an Arabic type of trumpet, which was probably distributed with the Seljuks before the First Crusade (from 1095). In the illustration for the Lincoln College Apocalypse (MS 16, in Oxford) from the beginning of the 14th century, the angels blow a very long, narrow-bore trumpet with three thickenings, held horizontally in one hand,[55] such an oversized trumpet plays Man in the Gorleston Psalter (fol. 43v). Jeremy Montagu (1981) highlights the influence of Moorish armies in the Iberian Peninsula, from where the long trumpet, with its Spanish name añafil, spread.[56]

Añafil was the name of a trumpet in Spanish from the 13th to the 15th century, which was considered "trompeta de los moros" (trumpet of the Moores) because of its origin. The ballad La pérdida de Alhama, which has survived in several versions from the 16th century, is about the conquest of the Muslim city of Alhama by the Catholic Monarchs in 1482, told like a lament from the perspective of the Muslim Emir of Granada. This event marks the beginning of the last military actions against al-Andalus during the Reconquista that ended in 1492 with the capture of the city of Granada. In the ballad, when the Emir reaches the conquered city, he sounds his silver-made ceremonial trumpets (añafiles). The mentioned expensive metal from which the trumpets are made is said to refer to the luxurious life of the Muslim rulers in al-Andalus and to identify the trumpets as royal instruments. Silver añafiles are also a symbol of the luxurious life of the Muslims in other poems about the Spanish reconquest of Granada (genre: romances fronterizos). A ballad entitled La Conquista de Antequera states: "añafiles, trompetas de plata fina" ("Trumpets of Fine Silver").[57]

Some military musical instruments, including trumpets, mentioned by common Latin names, were taken by Crusaders to the Middle East, where they encountered the military bands there. The eyewitness Fulcher of Chartres was impressed when he reported how the Egyptians jumped ashore from their ships in 1123 with loud shouts and the blowing of brass trumpets (aereae tubae).[58] In 1250, the Christian army attempted the Sixth Crusade under the leadership of the French King Louis IX to conquer Egypt. As the Christians from the Mamluks were successfully repulsed, the Sultan's military band played a major part in the victory. At that time it consisted of 20 trumpets, 4 cone oboes, 40 kettle drums and 4 cylinder drums.[59]

Curt Sachs (1930) is of the opinion that the oriental trumpet, adopted by the Muslims, was understood by the Christians as a "ceremonial weapon, equal to the standard" and as a "precious trophy in the religious struggle in hard strife... snatched from the enemy" and as due to its princely origins, it remained a “noble instrument” in Europe as part of the booty.[60] Alfons M. Dauer (1985) contradicts this when he suspects that the combination of trumpets and drums was adopted as a whole and served in Europe with the same purposes of representing and deterring the war enemy. Apocalypse depictions of the trumpet calling down the end of the world before the Last Judgment were terrifying images that continued to be associated with this instrument. [61]

Up until the 14th century, except for hunting horns (Latin bucullus, "little ox"), there were only straight trumpets in Europe, no twisted ones.[62] Two sizes of straight trumpets were distinguished: trompe and the smaller trompette in France, trompa and añafil in Spain. The oriental nafīr was often tonally different shrill, high-pitched instrument in contrast to the other trumpets, which sound low and dull. An orchestra often consisted of several large and only one or a few small trumpets. This emerges from the written sources in Spain, France and England; trumpets of different sizes in an ensemble can hardly be seen in illustrations. The French musicologist Guillaume André Villoteau (1759–1839), who belonged to the group of scholars who took part in Napoleon's Egyptian campaign (1798–1801), observed that the nafīr was the only trumpet used by the Egyptians to rise above the noisy wild overall sound of the conical oboes, drums and cymbals, emitting single, piercingly high bursts of sound.[63]

The tradition of the long trumpet añafil is still cultivated in Andalusia today in Holy Week processions during religious prayers (saetas). Short trumpet blasts are produced at a very fast tempo at a height of up to d3, above the vocal parts.[64] The saeta singing is stylistically linked to the medieval Portuguese cantiga ("song") and the singing forms abūdhiyya in Iraq and nubah in Arabic-Andalusian music in the Maghreb, which is a result of the eight centuries of cultural encounters (until 1492) between al Andalus and Christian Spain.[65]

Arabia

[edit]In the 7th/8th century, būq was not yet a war trumpet for the Arabs, but used for the snail horn blown on the Arabian Peninsula.[66] According to the historian Ibn Hischām in the 9th century, būq in previous centuries referred only to the war trumpet of the Christians and the wind instrument for the call to prayer among the Jews (the shofur).

Instead, the early Islamic Arabs used the reed instrument mizmar and the rectangular frame drum duff in battles.[67]

In the 10th century, the military orchestra, composed of the trumpet būq an-nafīr, the conical oboe surnā, the differently sized kettle drums dabdab and qasa, and the cymbals sunūj (singular sinj); this orchestra represented an important symbol of representation for the Arab rulers.[67] As the Fatimid Caliph al-ʿAzīz(r. 975–996) invaded Syria from Egypt in 978, he had 500 musicians with bugles (clairon, būq) with him; the sources also report large Fatimid military orchestras on other occasions. Arab authors around this time distinguished the metal trumpets būq and nafīr.[68] Between the 11th and 14th centuries, the range of instruments used in military bands became significantly more diverse and the musical possibilities may have expanded as a result.[69]

In 1260 A.D. the Egyptian Mamluk army fought and defeated the European Army led by the French King Louis IX in the Sixth Crusade. The Sultan's military band had a certain share in the victory. During the reign of the Mamluk Bahri Dynasty in the 13th century, the Sultan's military orchestras included 20 trumpets, 4 conical oboes, 40 kettle drums and 4 other drums. The Mamluk army was commanded by 30 emirs, each with their own musicians playing 4 trumpets, 2 conical oboes and 10 drums. The military bands were called tabl-chāna ("Drum House") because they were kept in a room in the main gate of the palace.[70]

Arabic sources provide information about the names and approximate shape of the oriental trumpets in the late Middle Ages. The Arabic name nafīr was first mentioned by the Seljuks in the 11th century. The original meaning of nafīr was "call to war", which is why the corresponding trumpet used was called būq an-nafīr. In today's Turkish, nefir means "trumpet/horn" and "war signal".[71] A distinction must be made between the straight trumpet nafīr of the early Ottoman military bands (mehterhâne) and the twisted trumpet boru, which derives from European influence in later time.[72] Spanish añafil is traced back to nafīr for a medieval Spanish long trumpet, and the German word fanfare is thought to derive from anfār, the Arabic plural form of nafīr.

Persia

[edit]In Persia, the Arab military orchestra tabl-chāna, consisting of kettle drums, cylinder drums, cymbals, straight and curved trumpets, and cone oboes, which initially belonged to the privileges of the caliphs and emirs, was soon also permitted under the Buyid dynasty (ruled 930–1062). Military commanders and ministers are maintained with their own army. The size of the orchestra was graduated according to the rank of those in power.[73] The orchestras named after the kettle drum naqqāra as naqqāra-khāna or as naubat were given representative functions in addition to the military ones.[74][75][76]

The historical work Tuzūkāt-i Tīmūrī became known in Persian in the Mughal Empire in the time of Shah Jahan (r. 1627–1658). It deals with the rule of Timur over the Iranian highlands in the second half of the 14th century and was apparently originally written in a Turkic language. The tuzūkāt gives details of the insignia of the military leaders, consisting of banners (ʿalam), drums and trumpets, according to their rank. Each of the twelve emirs accordingly received a banner and a cauldron drum (naqqāra). The Commander-in-Chief (amīr al-umarāʾ) also received the exclusive banner tümentug (tümen stands for a military unit of 10,000 men) and the banner tschartug. The colonel (minbaschi) received the banner tug (with a ponytail) and a trumpet nafīr, the four provincial governors (beglerbegi, beylerbey in the Ottoman Empire) received two banners (ʿalam and tschartug), a naqqāra and the trumpet burghu (horn).[77]

The nafīr in Persia had a long cylindrical tube and a conical bell. A drawing with Turkmen and Chinese influences, probably made in Herat in the 15th century, shows houris playing music in paradise, playing a round frame drum with a tambourine ring, a bent-necked lute (barbat) and a long cylindrical trumpet. What is unusual about this nafīr is the large bell-shaped bell.[78]

After the detailed description of Persian musical instruments in Abd al-Qadir Maraghi's (circa 1350–1435) music-theoretical works Jame' al-Alhān (“Collection of Melodies”) and Maqasid al-Alhān (“Sense of Melodies”) was written at the beginning of the 15th century the straight trumpet nafīr was distinguished from the S-curved trumpet karnā and the wider trumpet burgwāʾ (burghu, cognate with boru for the twisted Turkish trumpet).[9] The Arabic name būq for "(brass) wind instrument" apparently did not denote a trumpet, but in the combination būq zamrīa indicated a reed instrument made of metal. A single-reed instrument was called zamr siyāh nāy (Arabic mizmar),[79] a double-reed instrument was called surnāy or surnā, and another nāʾiha balabān. In the first place with Abd al-Qadir is the flute nāy, of which there were different sizes.[80]

A regulation of privileges as in Persia also existed in the Ottoman Empire. There, in the second half of the 18th century, the sultan's representative orchestra had around 60 members, 12 of whom were nefīr players (nefīrī). Such orchestras, which belonged to the high dignitaries, traveled with them and otherwise played every day before the three times of prayer (salāt) and on the occasion of special secular events.[81]

-

Persian naqqāra-khāna or naubat.

-

Musicians pursuing, in fight where Bahram Recovers the Crown of Rivniz

-

Kay Khusrau kills Aila. Baysungur's Shahnama. Painted 1430. The Gulistan Palace Museum, Tehran

-

Israfel blowing nafir, early 15th century miniature.

-

Archangel Israfel blows nafir, from Al-Qazwinis The Wonders of Creation, Or 4701 fol38v

-

Faridun Embraces Manuchihr. Painted circa 1525. (Upper left, right middle)

-

Nafir trumpets, from the Tarikh-i 'alam-ara-yi Abbasi of Iskander Bayg Munshi, circa 1650.

-

Nafir or karna trumpets, from the Tarikh-i 'alam-ara-yi Abbasi of Iskander Bayg Munshi, circa 1650.

India

[edit]

From the 8th century onwards, Arab-Persian military music came to northern India with the Muslim conquerors. The name naqqāra for kettle drums (as nagārā and similar variations) became common with the coming to power of the Delhi Sultanate from 1206 A.D. In addition to their military duties, the naqqāra-khāna or naubat developed into splendid representative orchestras at the ruling houses.[2][75] The naqqāra-khāna of the Mughal emperor Akbar (r. 1556–1605) existed according to the court chronicle Āʾīn-i Akbarī written by Abu 'l-Fazl around 1590[2][82]

It included 63 instruments, two thirds of which were different drums. Wind instruments were added: 4 straight long trumpets karnā made of "gold, silver, brass or other metal", 3 smaller straight metal trumpets nafīr, 2 curved brass horns sings (or sringas) in the shape of cow horns and 9 cone oboes surnā (now known as shehnai in North India).[83]

Early evidence of the wind instrument designation nafīr in India is the historical work Tajul-Ma'asir by the 12th and 13th century historian and poet Hasan Nizami, in which nafīr and surnā are mentioned. The Persian poet Nezāmi (c. 1141–1209) mentions the wind instruments nafīr, shehnai and surana. The folk epic Katamaraju, about the hero of the same name and a caste of cowherds in the 12th century, was written either by the early 15th century Telugu poet Srinatha or after 1632. It contains the word nafiri for a wind instrument. By nafiri or naferi, however, outside the context of Persian representative orchestras is meant cone oboes derived only by name from the Persian trumpet and related to the shehnai imported from central or west Asia.[84] The nafiri is a slightly smaller conical oboe found regionally in northern India in folk music. Numerous other regional names for double-reed instruments in India include mukhavina, sundri, sundari, mohori, pipahi, and kuzhal.

Mughal-era representative orchestras have disappeared in India since the early 20th century. What remains are simple naubat ensembles with the pair of kettledrums nagara and a conical oboe (shehnai or nafiri) at a few Muslim shrines in Rajasthan, including the tomb of the Sufi saint Muinuddin Chishti in Ajmer, where — following tradition — they appear at the entrances.[85][86]

Instead of the short, straight trumpet nafir, longer trumpets are used in some regions of India today on ceremonial occasions (temple services or family celebrations), the tradition of which may date back to pre-Islamic times, including the bhankora in the northern Indian state of Uttarakhand and the tirucinnam in Tamil Nadu in southern India. The most widespread is the semi-circular trumpet or kombu (in southern India, in the north shringa and ransingha, also turahi, a conical trumpet curved into an S.

-

Circumcision ceremony for Akbar's sons. (Bottom left corner)

-

Akbar in Ghazni ((Upper left corner)

-

The Birth of Timur. (Bottom right corner)

-

Chester-Beatty Akbarnama, kept in the Cincinnati Art Museum

-

English: Hunting scene near Agra, June/July 1561. Illustration for 1. Akbar-nama, Victoria and Albert Museum, IS. 2:24-1896. Curved trumpet top right.

-

Page from Tales of a Parrot (Tuti-nama)- 1655. Cleveland Museum of Art

-

Illustration (detail) for the Akbarnama in the Golestan Palace Library (circa 1590 A.D.). Trumpets, to left.

Africa

[edit]After the Muslim Arabs conquered the whole of North Africa as far as the Maghreb in the 7th century, most of the empires on the southern edge of the Sahara were at least partially Islamized by the 14th century. With the founding of Islamic sultanates, the African rulers adopted kettle drums, long trumpets and double-reed instruments from the Arab-Persian tradition in their representative orchestras and as insignia of their power. The instruments were adopted in musical styles that were still mainly rooted in the African tradition.[87] The narrow-bore metal trumpets used by the Hausa in northern Nigeria and in the south are typical. In Nigera they are known as kakaki and with similar names further afield in the western Sudan region. The kakaki is an extremely long, thin trumpet related to the Central Asian karnai.[61] These are known as gashi among Islamic people in Chad and among the Kanuri people in Nigeria.[88]

The kakaki trumpet type differs from the shorter nafīr, now found primarily in Morocco, and was probably spread in other ways. When the Arabic name nafīr referred to a metal trumpet in the 11th century, būq was no longer understood as a trumpet, but as an animal horn. From this time the metal trumpet nafīr may have arrived in the Maghreb on its way along the African Mediterranean coast to al-Andalus. The kakaki, on the other hand, could have been introduced from the north through the Sahara, up the Nile via the Sudan, or from the east coast of Africa. The Muslim traveler Ibn Battūta (1304–1368 or 1377) first visited Mogadishu on the east coast of Africa at the beginning of the 14th century, coming from Aden. He reports seeing a procession of the Sultan there led by a military band with drums (tabl), horns (būq) and trumpets (nafīr). At the sultan's palace, this military band (tabl-chāna) played the same instruments, but reinforced by cone oboes (surnāy), based on Egyptian models, while the audience stayed silent.[89] In whatever route that oriental trumpets were distributed south of the Sahara, they encountered numerous horns and trumpets already common to sub-Saharan Africa that also served representative purposes, including transverse horns like the phalaphala or long longitudinal trumpets like the wazza. The kakaki may have replaced a long wooden ceremonial trumpet which survives among the Hausa in a short version called the farai.[90]

Today, the old military signal trumpet nafīr is still occasionally used in Morocco to call out prayer times in Ramadan, unless replaced by a loudspeaker on the minaret. According to tradition, during the fasting month of Ramadan in the old town (Medina) of the big cities, a nafīr wind blower goes through the streets at nightfall and gives the signal to break the fast (iftār), as well as early in the morning it announces the last meal (sahūr) before sunrise. In the 17th century in the Maghreb there was also the nafīr called tarunbataa, a European single-wind trumpet presumably equivalent to the Clairon.[91]

The Moroccan nafīr,[92] with which only one tone is produced, consists of a brass or copper tube averaging 150 centimeters in length, the outer diameter of which is reportedly 16 millimeters. The one-to three-part cylindrical tube widens at the bottom to form a funnel-shaped bell with a diameter of 8 centimeters or more. The funnel-shaped mouthpiece is soldered to the tube.[5]

Theodore C. Grame (1970) heard among the musicians who regularly performed on the Djemaa el Fna in Marrakesh a group from the esoteric Sufi sect Aissaoua, who practiced snake charmering with music on the square, partly as a public spectacle and partly as a religious exercise. They consider snakes and scorpions to be protective forces. On one occasion five Aissaoua musicians performed with three frame drums banādir (singular bandīr), a conical oboe ghaita and a trumpet nafīr louder than anything else.[93] Bandīr, ghaita and nafīr can also be played as processional music at weddings, circumcisions and other family celebrations.[5]

Malay Archipelago

[edit]In contrast to the large number of African trumpet types, traditional trumpets are almost unknown in Southeast Asia. In some places animal horns or snail horns were used as signaling instruments. The name tarompet, taken from the Dutch, does not mean a trumpet in Indonesia, but a rare double-reed instrument.

The Persian representational orchestra, naubat, spread east to the Malay Archipelago with the spread of Indo-Islamic culture. The first small Muslim empires with a naubat (Malay gendang nobat) were probably the Sultanate of Pasai on the northern tip of Sumatra and the island of Bintan in the Riau archipelago in the 13th century. From Bintan, the nobat was taken to Temasek, now Singapore, on the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula.[94] According to the Sejarah Melayu ("Malay Annals"), a historical work probably first written in the 17th century, the nobat orchestra was introduced in the Kingdom of Malacca after the third ruler Mohammed Shah (r. 1424–1444) converted to Islam. A little later most of the sultanates in North Sumatra and Malaysia had adopted such a nobat. While in Indonesia the sultanates on Sumatra lost their independence after the colonial period with independence in 1945 (Java did not have such, choosing to rely on the pre-existing gamelan orchestras), in Malaysia the king remained head of state and a palace orchestra is used in his presence to this day. Corresponding orchestras are also used in individual Malaysian states to this day on courtly ceremonial occasions and on Muslim holidays.[95]

The orchestras usually consist of one or two kettledrums nengkara (nehara or nekara, derived from naqqāra, head diameter 40 centimetres), which are not played in pairs here, two double-headed drums gendang nobat, one or two conical oboes called serunai (derived from surnāy), a trumpet nafiri and in Kedah and Brunei a hanging nipple gong (in the latter two large gongs are added), while in Terengganu the cymbals are called kopak-kopak. Kelantan's orchestra has no nafiri, instead they have rebab lutes due to Thai influence. Brunei's two orchestras, the Naubat Diraja & Gendang Jaga-Jaga, also have none. The nafiri has a conical tube about 70 centimeters long that is made of silver. In the states of Kedah and Perak, the musical instruments are kept in a separate building Balai Nobat (corresponding to the naqqāra-khāna, "drum house" of the Mughal palaces), otherwise in a separate room in the palace.[96] The nobat of the Palace of Kedah displayed in the State Museum of Kedah (Muzium Negeri Kedah) in Alor Setar is composed of seven instruments: a kettle drum nohara, a large tubular drum gendang ibu, a small tubular drum gendang anak (“mother-drum” or “child-drum”), a trumpet nafiri, a conical oboe serunai, a brass gong and a 1.8 meter long ceremonial staff (semambu) made of rattan. The trumpet is 89 centimeters long and is made of pure silver.[97][98]

The instruments of the nobat, especially the drums, had a magical meaning, which is why some rituals and regulations were associated with them that date back to pre-Islamic times. According to tradition, the ceremonial instruments of Kedah predate those of Malacca and were brought directly from Persia. The loudest possible sound of drums, trumpets and conical oboes should be reminiscent of thunder; only with the sound of thunder could a ruler with the necessary legitimacy be installed in his office when there was a change in power.[99] The rulers trace their lineage through a son of the last Sultan of Malacca to the kings of ancient Singapore and on to the mythical founder of the Malay empires who once appeared at the sacred site of Bukit Seguntang (near Palembang) in Sumatra.[100]

The word daulat (from Arabic ad-dawla, "state", "state power") has a religious component in the Malay language beyond the worldly power of the king, which refers to the idea of a god-king introduced by the Indians in the 1st millennium (devaraja, from Sanskrit deva, "god"; rājā, "king") and ascribes divine power over his people to the sultan. According to the notion that is still widespread today, this daulat should also be included in the insignia of the sultan, which includes the musical instruments of the nobat. The law of the Riau-Lingga Sultanate in the 19th century dictated that every person had to stand still as soon as a nafiri was heard, because the nafiri deserved respect as an instrument bearing the daulat.[101]

The court musicians of the nobat of Perak, Kedah and Selangor are called orang kalur (also orang kalau). They have a hereditary status and a lineage lost in ancient times and mythical tales.[102] Walter William Skeat (1900)[103] and Richard James Wilkinson (1932) comment on the sacred importance of musical instruments that the tubular drums and the silver trumpet may only be played when the king is present, meaning that these instruments are held in the highest esteem. The two kettle drums were therefore of the second highest importance at the beginning of the 20th century, they could be sent to a guest of honour on behalf of the king or accompany them. Only those of the orang kalur were allowed to touch the instruments; if someone else blew the trumpet, it should mean instant death for that person by the powerful spirit within the trumpet. It was said that when the king died, drops of sweat would form on the trumpet. In order to maintain this power of the instruments, it was the king's duty to perform a magical renewal ceremony every two to three years.[104]

Literature

[edit]- Anthony Baines: Brass Instruments. Their History and Development. Faber & Faber, London 1976

- Alfons Michael Dauer: Tradition of African wind orchestras and the emergence of jazz. (Contributions to Jazz Research Vol. 7) Academic Printing and Publishing House, Graz 1985

- Henry George Farmer: Islam. (Heinrich Besseler, Max Schneider (ed.): Music history in pictures. Volume III: Music of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Delivery 2) Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1966

- Henry George Farmer: Būķ. In: The Encyclopedia of Islam. New Edition, Vol. 1, 1960, pp. 1290b–1292a

- Henry George Farmer: A History of Arabian Music to the XIIIth Century. Luzac & Co., London 1929

- KA Gourlay: Long Trumpets of Northern Nigeria - In History and Today. In: Journal of International Library of African Music, Vol. 6, No. 2, 1982, pp. 48–72

- Sibyl Marcuse: Musical Instruments: A Comprehensive Dictionary. A complete, authoritative encyclopedia of instruments throughout the world. Country Life Limited, London 1966, p. 356f, sv “Nafīr”

- Michael Pirker: Nafīr. In: Grove Music Online, 2001

- Curt Sachs: Handbook of Musical Instruments. (1930) Georg Olms, Hildesheim 1967

References

[edit]- ^ a b Christian Poché (2001). "Būq (Iran. bāq)". Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.04336.

- ^ a b c d Geeti Sen (1 January 1979). "Music and Musical Instruments in the Paintings of the Akbar Nama". Library Artifacts. 8 (4).

the paintings of the Akbar Nama...these illustrations confirm the fact that the naqqarakhana was intended to refer to a musicians' gallery, assigned to a specific place in Mughal architecture...[pages 2-3]...to indicate the ritual progression of time through the hours of a day [page 1]...scenes of court festivity. Rites of births and marriage are invariably accompanied with a specific role assigned to the musicians of the naqqarakhana [page 4]...these same instruments of royalty were carried into the battlefield

- ^ a b Stanley Sadie (ed.). "Nafir". The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments.

...it also spread to India where it is known as the karnā and karnay...

- ^ Д. Раҳимов. Касбу ҳунарҳои анъанавии тоҷикон. – Душанбе, 2014. – С. 40 - 42 (D. Rahimov. Traditional crafts of Tajiks. - Dushanbe, 2014. - p. 40 - 42.)

- ^ a b c Anthony Baines: Encyclopedia of Musical Instruments. JB Metzler, Stuttgart 2005, p. 216, sv "Nafīr"

- ^ a b c d e f g Farmer, H.G. (1960). "Būḳ". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). The encyclopaedia of Islam (Second ed.). Leiden: Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0127. ISBN 90-04-16121-X. OCLC 399624.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ "Karnay". Musical Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. - M. Soviet Encyclopedia. 1974.

КАРНАЙ - духовой музыкальный инструмент: труба из латуни с прямым, реже коленчатым стволом и большим колоколообразным раструбом. Общая дл. 3 м. (translation: KARNAI - a wind musical instrument: a brass trumpet with a straight, less often angular barrel and a large bell-shaped bell. Total length 3 m.)

- ^ Sibyl Marcuse (1964). "Añafil". Musical instruments; a comprehensive dictionary. New York: Doubleday and Company. p. 15.

- ^ a b Henry George Farmer (December 1962). "ʿAbdalqādir ibn Ġaibī on Instruments of Music". Oriens. 15: 247.

ʿAbdalqādir ibn Ġaibī al-Ḥāfiz al-Marāġī, who died in the year 1435 at Herdt...Cāmi' al-alḥān...The nafir (trumpet) was the longest of its kind. Whatever was longer was known as the burġwā (sic! but usually termed the būrū or borī). If the centre of the tube of a trumpet was turned back upon itself—in a flattened 'S' shape—it was known as the karrahnāy (sic! the modern karnā).

- ^ Sibyl Marcuse (1964). "Būq". Musical instruments; a comprehensive dictionary. New York: Doubleday and Company. p. 73.

trumpet...conical bore...originally a *natural horn, the būq was subsequently made of metal...

- ^ a b Farmer, H.G. (1960). "Būḳ". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). The encyclopaedia of Islam (Second ed.). Leiden: Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0127. ISBN 90-04-16121-X. OCLC 399624.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) It should be understood that the term būḳ was used for all instruments with a conical tube, whether crescent-shaped or straight, irrespective of the material of its facture,—shell, horn, or metal. - ^ Curt Sachs, 1967, p. 282

- ^ Curt Sachs, 1967, p. 282

- ^ Ghost Music. British Broadcasting Corporations (BBC). April 2011.

[Summary: King Tut's trumpets and also close reproductions were tested using modern mouthpieces as well as without a mouthpiece. The latter was how they originally were played. Using a mouthpiece allowed more notes to be played, but one of the original trumpets was damaged from the pressure made by playing the highest note. Without the modern mouthpiece, only two notes were playable.]

- ^ Jeremy Montagu (1978). "One of Tut'ankhamūn's Trumpets". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 64. Sage Publications, Ltd.: 133–134. doi:10.2307/3856451. JSTOR 3856451.

a ceremonial instrument capable of producing only one or two notes. The lowest note is poor in quality and carrying power...the Egyptian military trumpet signal code was a rhythmic one on a single pitch...

- ^ Joachim Braun: Music in Ancient Israel/Palestine. Archaeological, Written, and Comparative Sources. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids (Michigan) 2002, p. 11

- ^ Jeremy Montagu, Musical Instruments of the Bible. Scarecrow Press, Lanham 2002, pp. 56f, 97

- ^ Illustrated in: Piotr Bieńkowski: Representations of the Gauls in Hellenistic Art. Alfred Hölder, Vienna 1908, Plate VIIb

- ^ Anthony Baines, 1976, pp. 61–64

- ^ James W McKinnon: Buccina. In: Grove Music Online, 2001

- ^ a b c Michael Pirker (Spring 1993). "The Looped Trumpet in the Near East". RIdIM/RCMI Newsletter. 18 (1). Research Center for Music Iconography, The Graduate Center, City University of New York: 3–8. JSTOR 41604971.

century. Shortly before the turn of that century, a new type of trumpet.. a bent tube with an S-shape...is depicted on a wooden relief from 1397 in Worcester Cathedral...Early evidence of the trumpet with an S-shaped tube in the Orient is in the illuminated manuscript from the year 1486 (Türk ve Islam Eserleri Müzesi, Istanbul, T1964, f.32r [fig 1]

- ^ a b Margaret Sarkissian; Edward H. Tarr (2001). "Trumpet (Fr. trompette; Ger. Trompete; It. tromba)". Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.49912.

Around 1400 instrument makers learnt to bend the trumpet's tubing: first to an S-shape...soon afterwards with this S-shape folded back on itself to form a loop – a more compact arrangement

- ^ Hours of Charles the Noble, King of Navarre (1361-1425), fol. 316v, Text. 1405.

[summary: In the margin is an illustration of a half-human, playing a curved trumpet, curved with an s-curve]

- ^ Paul Kahle : Islamic shadow play figures from Egypt. Part 2. In CH Becker (ed.): The Islam. Journal for history and culture of the Islamic Orient. 2nd volume, Karl J. Trübner, Strasbourg 1911, pp. 143–195, here p. 145

- ^ Michael B. Charles: Elephant ii. In the Sasanian Army. In: Encyclopædia Iranica, December 15, 1998

- ^ Bruce P. Gleason: Cavalry Trumpet and Kettledrum Practice from the Time of the Celts and Romans to the Renaissance. In: The Galpin Society Journal, Vol. 61, April 2008, pp. 231–239, 251, here p. 232

- ^ a b Henry George Farmer, 1929, p. 208

- ^ Bruce P Gleason, 2008, p. 233

- ^ Henry George Farmer, 1929, p. 154

- ^ Henry George Farmer, 1929, p. 210

- ^ "The Archangel Israfil late 14th–early 15th century". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ Henry George Farmer, 1966, p. 76

- ^ Henry George Farmer, 1966, p. 84

- ^ Bernhard Höfele: Military Music. III. Field Music in the Middle Ages. In: MGG Online, November 2016 ( The Music Past and Present, 1997)

- ^ Joachim Braun: Music in Ancient Israel/Palestine. Archaeological, Written, and Comparative Sources. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids (Michigan) 2002, pp. 292f

- ^ Sibyl Marcuse (1964). "Nafir". Musical instruments; a comprehensive dictionary. New York: Doubleday and Company. p. 356.

- ^ a b c d Michael Pirker (2001). "Nafīr". Grove Music Online.

- ^ Munshi Bahmanji Dosabhai (1873). Idiomatic Sentences in the English, Gujarati, and Persian Languages, the Whole in Oriental an Roman Characters in Seven Parts. Bombay: Reporter's Press. p. 122.

- ^ Hermann Möller : Comparative Indo-European-Semitic dictionary. (1911) 2nd edition: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1970, p. 227

- ^ Alfons Michael Dauer, 1985, p. 56

- ^ Henry George Farmer: The Music of the Arabian Nights (Continued from p. 185, October, 1944). In: The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, No. 1, April 1945, pp. 39-60, here p. 47

- ^ a b c Müge Göçek, F. (2012). ""Nefīr"". In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Retrieved 13 January 2023.

- ^ Laurence Picken : Folk Musical Instruments of Turkey. Oxford University Press, London 1975, p. 482

- ^ a b Henry George Farmer: Turkish Instruments of Music in the Seventeenth Century. In: Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, No. 1, January 1936, pp. 1-43, here p. 28

- ^ Robert Stevenson, Spanish Music in the Age of Columbus. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague 1960, p. 22

- ^ Henry George Farmer: Historical Facts for the Arabian Musical Influence. William Reeves, London 1930, p. 13; Henry George Farmer, 1966, p. 106

- ^ Edward H. Tarr (2001). "Fanfare (Fr. fanfare; Ger. Fanfare; It. fanfara)". Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.09285. Retrieved 13 January 2023.

Published in print: 20 January 2001Published online: 2001

- ^ KA Gourlay, 1982, p. 50

- ^ Anthony Baines, 1976, pp. 67f

- ^ Sadie Stanley (ed.). "Beme". The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. Vol. 1. p. 219.

'Bemastocc' signifies one made of wood

- ^ Heinrich Hüschen: Isidore of Seville. In: Friedrich Blume (ed.): Music in the past and present, 1st edition, volume 6, 1957, column 1438, table 64

- ^ Adriano Peroni: The Baptistery of Novara. architecture and painting. In: ICOMOD - Issues of the German National Committee, Vol. 23, 1998, pp. 155–160

- ^ Anthony Baines, 1976, S. 72–74

- ^ Büchler, Alfred (1992). "Olifan, Graisles, Buisines and Taburs: The Music of War and the Structure and Dating of the Oxford Roland". Olifant. 17 (3–4): 147.

- ^ Anthony Baines, 1976, pp. 74–76

- ^ Jeremy Montagu: History of Musical Instruments in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Herder, Freiburg 1981, p. 41

- ^ Jan Gilbert: The Lamentable Loss of Alhama in “Paseábase el rey moro”. In: The Modern Language Review, Vol. 100, No. 4, October 2005, pp. 1000–1014, here p. 108

- ^ Anthony Baines, 1976, p. 75

- ^ Henry George Farmer, 1966, p. 52

- ^ Curt Sachs, 1967, p. 285

- ^ a b Alfons Michael Dauer, 1985, p. 58

- ^ Jeremy Montagu, 1981, p. 42

- ^ Anthony Baines, 1976, p. 88

- ^ Anthony Baines, The Evolution of Trumpet Music up to Fantini. In: Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association, Vol. 101, 1974–1975, pp. 1-9, here pp. 8f

- ^ Habib Hassan Touma: Indications of Arabian Musical Influence on the Iberian Peninsula from the 8th to the 13th Century. In: Revista de Musicología, Vol. 10, No. 1, January–April 1987, pp. 137–150, here p. 147

- ^ Henry George Farmer, 1960, p. 1291a

- ^ a b Henry George Farmer: A History of Arabian Music to the XIIIth Century. Luzac & Co., London 1929, p. 154

- ^ Henry George Farmer, 1929, pp. 208, 210

- ^ Christian Poché: Būq. In: Grove Music Online , 2001

- ^ Henry George Farmer, 1966, p. 52

- ^ Michael Pirker (2001). "Nafīr [nefir, nfīr]". Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.19529.

- ^ Cf. F. Müge Göçek (1995). Encyclopedia of Islam. New Edition. Vol. 8. p. 3b.

- ^ Henry George Farmer: Ṭabl-Khāna. In: Encyclopedia of Islam. New Edition, Volume 10, 2000, p. 35b

- ^ John Baily; Alastair Dick (20 January 2001). "Naqqārakhāna [naqqāraḵẖāna, tablkhāna]". New Grove Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.51719.

- ^ a b Alastair Dick: Nagāṙā. In: Grove Music Online, 2001

- ^ John Baily (1980). "A description of the naqqarakhana of Herat, Afghanistan". Asian Music. 11 (2).

An important feature of the old music of North India, Afghanistan, Iran and Central Asia was that type of ensemble known as the naqqarakhana, named after the kettledrums (naqqara) that were one of its prominent features. The music played by ensembles of this kind can be variously described as royal, ceremonial, civil or military.

- ^ Gergely Csiky: The Tuzūkāt-i Tīmūrī as a Source for Military History. In: Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, Vol. 59, No. 4, 2006, pp. 439–491, here p. 476

- ^ Henry George Farmer, 1966, p. 114

- ^ Henry George Farmer: Meccan Musical Instruments. In: The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, no. 3, July 1929, pp. 489–505, here pp. 498f

- ^ Henry George Farmer, 1966, p. 116

- ^ F. Müge Göçek: Nefīr. In: Encyclopedia of Islam. New Edition, Vol. 8, 1995, p. 3b

- ^ Geeti Sen: Music and Musical Instruments in the Paintings of the Akbar Nama.. In: National Center for the Performing Arts Quarterly Journal, Vol. 8, No. 4, 1979, pp. 1-7

- ^ Reis Flora: Styles of the Śahnāī in Recent Decades: From naubat to gāyakī ang. In: Yearbook for Traditional Music, Vol. 27, 1995, pp. 52–75, here p. 56

- ^ Bigamudre Chaitanya Deva: The Double-Reed Aerophone in India. In: Yearbook of the International Folk Music Council, Vol. 7, 1975, pp. 77–84, here pp. 79f

- ^ RAM Charndrakausika. "अजमेर-Ceremonies from The Holy Shrines of Ajmer-اجمير".

Naubat of Ajmer

- ^ See Kathleen Toomey: Study of Nagara Drum in Pushkar, Rajasthan.. Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection, 1816, Spring 2014

- ^ Amnon Shiloah: Arabic Music. VII. Decentralization and emergence of local styles since the 10th century. 5. Arabic Music in Islamic Africa. In: MGG Online, November 2016

- ^ Brandily, Monique (1984). "Gashi". In Sadie Stanley (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. Vol. 2. London: MacMillan Press. p. 26.

- ^ Henry George Farmer: Early References to Music in the Western Sūdān. In: The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, No. 4, October 1939, pp. 569–579, here pp. 571f

- ^ KA Gourlay: Farai. In: Grove Music Online, February 11, 2013

- ^ Henry George Farmer: Turkish Instruments of Music in the Seventeenth Century. In: Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, No. 1, January 1936, pp. 1-43, here p. 29

- ^ "Nafir trumpet, Fès, Morocco, ca. 1975, and Kakaki, Konni, Niger, ca. 1975". National Music Museum. Retrieved 2023-01-13.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Theodore C. Grame: Music in the Jma al-Fna of Marrakesh. In: The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 56, No. 1, January 1970, pp. 74–87, here p. 83

- ^ Patricia Ann Matusky, Tan Sooi Beng: The Music of Malaysia: The Classical, Folk, and Syncretic Traditions. (SOAS musicology series) Ashgate Publishing, Aldershot 2004, p. 240

- ^ Margaret J. Kartomi: The Royal Nobat Ensemble of Indragiri in Riau, Sumatra, in Colonial and Post-Colonial Times. Galpin Society Journal, 1997, pp. 3–15, here pp. 3f

- ^ Patricia Ann Matusky, Tan Sooi Beng, 2004, p. 241

- ^ Abu Talib Ahmad: Museums in the Northern Region of Peninsula Malaysia and Cultural Heritage. In: Kemanuslaan, vol. 22, no. 2, 2015, pp. 23–45, here p. 35

- ^ Terry E. Miller; Sean Williams, eds. (2008). The Garland Book of Southeast Asian Music. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-93144-8.

The instrumentation of late-twentieth-century nobat included one oboe (serunai); one trumpet (nafiri); two gendang, one drumhead, hit with the hand and the other with a stick; one kettledrum (nehara, alternately, nahara and nagara), hit with a pair of rattan sticks; and sometimes one knobbed gong, hit with a padded beater

- ^ Barbara Watson Andaya: Distant Drums and Thunderous Cannon: Sounding Authority in Traditional Malay Society. In: International Journal of Asia Pacific Studies, Vol. 7, No. 2, July 2011, pp. 19-35, here p. 26

- ^ W. Linehan: The Nobat and the Orang Kalau of Perak. In: Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. 24, No. 3 (156), October 1951, pp. 60–68, here p. 60

- ^ Raja Iskandar Bin Raja Halid: The Royal Nobat of Perak - Between Daulat and Music. In: Jurnal ASWARA. Akademi Seni Budaya dan Warisan Kebangsaan, Vol. 5, No. 1, June 2010, pp. 38–48, here p. 41

- ^ See Raja Iskandar Bin Raja Halid: Orang Kalur - Musicians of the Royal Nobat of Perak. 2009, pp. 1–23

- ^ Skeat, Walter W. (Walter William) (1900). Malay magic : being an introduction to the folklore and popular religion of the Malay Peninsula. London: Macmillan. p. 40.

- ^ Richard James Wilkinson : Some Malay Studies. In: Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. 10, No. 1 (113) January 1932, pp. 67-137, here pp. 82f