Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Seabed

View on Wikipedia

| Marine habitats |

|---|

| Coastal habitats |

| Ocean surface |

| Open ocean |

| Sea floor |

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as seabeds.

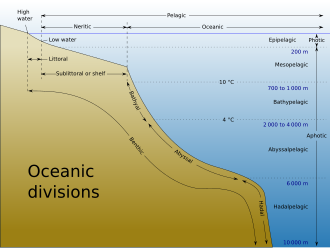

The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most of the ocean is very deep, where the seabed is known as the abyssal plain. Seafloor spreading creates mid-ocean ridges along the center line of major ocean basins, where the seabed is slightly shallower than the surrounding abyssal plain. From the abyssal plain, the seabed slopes upward toward the continents and becomes, in order from deep to shallow, the continental rise, slope, and shelf. The depth within the seabed itself, such as the depth down through a sediment core, is known as the "depth below seafloor". The ecological environment of the seabed and the deepest waters are collectively known, as a habitat for creatures, as the "benthos".

Most of the seabed throughout the world's oceans is covered in layers of marine sediments. Categorized by where the materials come from or composition, these sediments are classified as either: from land (terrigenous), from biological organisms (biogenous), from chemical reactions (hydrogenous), and from space (cosmogenous). Categorized by size, these sediments range from very small particles called clays and silts, known as mud, to larger particles from sand to boulders.

Features of the seabed are governed by the physics of sediment transport and by the biology of the creatures living in the seabed and in the ocean waters above. Physically, seabed sediments often come from the erosion of material on land and from other rarer sources, such as volcanic ash. Sea currents transport sediments, especially in shallow waters where tidal energy and wave energy cause resuspension of seabed sediments. Biologically, microorganisms living within the seabed sediments change seabed chemistry. Marine organisms create sediments, both within the seabed and in the water above. For example, phytoplankton with silicate or calcium carbonate shells grow in abundance in the upper ocean, and when they die, their shells sink to the seafloor to become seabed sediments.

Human impacts on the seabed are diverse. Examples of human effects on the seabed include exploration, plastic pollution, and exploitation by mining and dredging operations. To map the seabed, ships use acoustic technology to map water depths throughout the world. Submersible vehicles help researchers study unique seabed ecosystems such as hydrothermal vents. Plastic pollution is a global phenomenon, and because the ocean is the ultimate destination for global waterways, much of the world's plastic ends up in the ocean and some sinks to the seabed. Exploitation of the seabed involves extracting valuable minerals from sulfide deposits via deep sea mining, as well as dredging sand from shallow environments for construction and beach nourishment.

Structure

[edit]

Most of the oceans have a common structure, created by common physical phenomena, mainly from tectonic movement, and sediment from various sources. The structure of the oceans, starting with the continents, begins usually with a continental shelf, continues to the continental slope – which is a steep descent into the ocean, until reaching the abyssal plain – a topographic plain, the beginning of the seabed, and its main area. The border between the continental slope and the abyssal plain usually has a more gradual descent, and is called the continental rise, which is caused by sediment cascading down the continental slope.[citation needed]

The mid-ocean ridge, as its name implies, is a mountainous rise through the middle of all the oceans, between the continents. Typically a rift runs along the edge of this ridge. Along tectonic plate edges there are typically oceanic trenches – deep valleys, created by the mantle circulation movement from the mid-ocean mountain ridge to the oceanic trench.[1]

Hotspot volcanic island ridges are created by volcanic activity, erupting periodically, as the tectonic plates pass over a hotspot. In areas with volcanic activity and in the oceanic trenches there are hydrothermal vents – releasing high pressure and extremely hot water and chemicals into the typically freezing water around it.

Deep ocean water is divided into layers or zones, each with typical features of salinity, pressure, temperature and marine life, according to their depth. Lying along the top of the abyssal plain is the abyssal zone, whose lower boundary lies at about 6,000 m (20,000 ft). The hadal zone – which includes the oceanic trenches, lies between 6,000 and 11,000 metres (20,000–36,000 ft) and is the deepest oceanic zone.[2][3]

Depth below seafloor

[edit]Depth below seafloor is a vertical coordinate used in geology, paleontology, oceanography, and petrology (see ocean drilling). The acronym "mbsf" (meaning "meters below the seafloor") is a common convention used for depths below the seafloor.[4][5]

- Different seabeds in the world's oceans

-

gravel seabed in Italy

-

white sand seabed in Mexico

-

sand seabed in Greece

-

hydrothermal vents

Sediments

[edit]

Sediments in the seabed vary in origin, from eroded land materials carried into the ocean by rivers or wind flow, waste and decompositions of sea creatures, and precipitation of chemicals within the sea water itself, including some from outer space. There are four basic types of sediment of the sea floor:

- Terrigenous (also lithogenous) describes the sediment from continents eroded by rain, rivers, and glaciers, as well as sediment blown into the ocean by the wind, such as dust and volcanic ash.

- Biogenous material is the sediment made up of the hard parts of sea creatures, mainly phytoplankton, that accumulate on the bottom of the ocean.

- Hydrogenous sediment is material that precipitates in the ocean when oceanic conditions change, or material created in hydrothermal vent systems.

- Cosmogenous sediment comes from extraterrestrial sources.[6]

Terrigenous and biogenous

[edit]

Terrigenous sediment is the most abundant sediment found on the seafloor. Terrigenous sediments come from the continents. These materials are eroded from continents and transported by wind and water to the ocean. Fluvial sediments are transported from land by rivers and glaciers, such as clay, silt, mud, and glacial flour. Aeolian sediments are transported by wind, such as dust and volcanic ash.[7]

Biogenous sediment is the next most abundant material on the seafloor. Biogenous sediments are biologically produced by living creatures. Sediments made up of at least 30% biogenous material are called "oozes." There are two types of oozes: Calcareous oozes and Siliceous oozes. Plankton grow in ocean waters and create the materials that become oozes on the seabed. Calcareous oozes are predominantly composed of calcium shells found in phytoplankton such as coccolithophores and zooplankton like the foraminiferans. These calcareous oozes are never found deeper than about 4,000 to 5,000 meters because at further depths the calcium dissolves.[8] Similarly, Siliceous oozes are dominated by the siliceous shells of phytoplankton like diatoms and zooplankton such as radiolarians. Depending on the productivity of these planktonic organisms, the shell material that collects when these organisms die may build up at a rate anywhere from 1 mm to 1 cm every 1000 years.[8]

Hydrogenous and cosmogenous

[edit]

Hydrogenous sediments are uncommon. They only occur with changes in oceanic conditions such as temperature and pressure. Rarer still are cosmogenous sediments. Hydrogenous sediments are formed from dissolved chemicals that precipitate from the ocean water, or along the mid-ocean ridges, they can form by metallic elements binding onto rocks that have water of more than 300 °C circulating around them. When these elements mix with the cold sea water they precipitate from the cooling water.[8] Known as manganese nodules, they are composed of layers of different metals like manganese, iron, nickel, cobalt, and copper, and they are always found on the surface of the ocean floor.[8]

Cosmogenous sediments are the remains of space debris such as comets and asteroids, made up of silicates and various metals that have impacted the Earth.[9]

Size classification

[edit]

Another way that sediments are described is through their descriptive classification. These sediments vary in size, anywhere from 1/4096 of a mm to greater than 256 mm. The different types are: boulder, cobble, pebble, granule, sand, silt, and clay, each type becoming finer in grain. The grain size indicates the type of sediment and the environment in which it was created. Larger grains sink faster and can only be pushed by rapid flowing water (high energy environment) whereas small grains sink very slowly and can be suspended by slight water movement, accumulating in conditions where water is not moving so quickly.[11] This means that larger grains of sediment may come together in higher energy conditions and smaller grains in lower energy conditions.

Benthos

[edit]

Benthos (from Ancient Greek βένθος (bénthos) 'the depths [of the sea]'), also known as benthon, is the community of organisms that live on, in, or near the bottom of a sea, river, lake, or stream, also known as the benthic zone.[12] This community lives in or near marine or freshwater sedimentary environments, from tidal pools along the foreshore, out to the continental shelf, and then down to the abyssal depths.

Many organisms adapted to deep-water pressure cannot survive in the upper parts of the water column. The pressure difference can be very significant (approximately one atmosphere for every 10 metres of water depth).[13]

Because light is absorbed before it can reach deep ocean water, the energy source for deep benthic ecosystems is often organic matter from higher up in the water column that drifts down to the depths. This dead and decaying matter sustains the benthic food chain; most organisms in the benthic zone are scavengers or detritivores.

The term benthos, coined by Haeckel in 1891,[14] comes from the Greek noun βένθος 'depth of the sea'.[12][15] Benthos is used in freshwater biology to refer to organisms at the bottom of freshwater bodies of water, such as lakes, rivers, and streams.[16] There is also a redundant synonym, benthon.[17]Topography

[edit]

Seabed topography (ocean topography or marine topography) refers to the shape of the land (topography) when it interfaces with the ocean. These shapes are obvious along coastlines, but they occur also in significant ways underwater. The effectiveness of marine habitats is partially defined by these shapes, including the way they interact with and shape ocean currents, and the way sunlight diminishes when these landforms occupy increasing depths. Tidal networks depend on the balance between sedimentary processes and hydrodynamics however, anthropogenic influences can impact the natural system more than any physical driver.[18]

Marine topographies include coastal and oceanic landforms ranging from coastal estuaries and shorelines to continental shelves and coral reefs. Further out in the open ocean, they include underwater and deep sea features such as ocean rises and seamounts. The submerged surface has mountainous features, including a globe-spanning mid-ocean ridge system, as well as undersea volcanoes,[19] oceanic trenches, submarine canyons, oceanic plateaus and abyssal plains.

The mass of the oceans is approximately 1.35×1018 metric tons, or about 1/4400 of the total mass of the Earth. The oceans cover an area of 3.618×108 km2 with a mean depth of 3,682 m, resulting in an estimated volume of 1.332×109 km3.[20]

| Depth Range (meters)[21] | Seafloor Area (km²) | Seafloor Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 0 – 200 | 26,402,000 | 7.30% |

| 201 – 1000 | 15,848,000 | 4.38% |

| 1001 – 4000 | 127,423,000 | 35.22% |

| 4001 – 6000 | 188,395,000 | 52.08% |

| 6001 – 7000 | 3,207,000 | 0.89% |

| 7001 – 8000 | 320,000 | 0.09% |

| 8001 – 9000 | 111,000 | 0.03% |

| 9000 – 10,000 | 37,000 | 0.01% |

| 10,000 + | 2,000 | < 0.01% |

Features

[edit]

Each region of the seabed has typical features such as common sediment composition, typical topography, salinity of water layers above it, marine life, magnetic direction of rocks, and sedimentation. Some features of the seabed include flat abyssal plains, mid-ocean ridges, deep trenches, and hydrothermal vents.

Seabed topography is flat where layers of sediments cover the tectonic features. For example, the abyssal plain regions of the ocean are relatively flat and covered in many layers of sediments.[22] Sediments in these flat areas come from various sources, including but not limited to: land erosion sediments from rivers, chemically precipitated sediments from hydrothermal vents, Microorganism activity, sea currents eroding the seabed and transporting sediments to the deeper ocean, and phytoplankton shell materials.

Where the seafloor is actively spreading and sedimentation is relatively light, such as in the northern and eastern Atlantic Ocean, the original tectonic activity can be clearly seen as straight line "cracks" or "vents" thousands of kilometers long. These underwater mountain ranges are known as mid-ocean ridges.[6]

Other seabed environments include hydrothermal vents, cold seeps, and shallow areas. Marine life is abundant in the deep sea around hydrothermal vents.[23] Large deep sea communities of marine life have been discovered around black and white smokers – vents emitting chemicals toxic to humans and most vertebrates. This marine life receives its energy both from the extreme temperature difference (typically a drop of 150 degrees) and from chemosynthesis by bacteria. Brine pools are another seabed feature,[24] usually connected to cold seeps. In shallow areas, the seabed can host sediments created by marine life such as corals, fish, algae, crabs, marine plants and other organisms.

Human impact

[edit]Exploration

[edit]The seabed has been explored by submersibles such as Alvin and, to some extent, scuba divers with special equipment. Hydrothermal vents were discovered in 1977 by researchers using an underwater camera platform.[23] In recent years satellite measurements of ocean surface topography show very clear maps of the seabed,[25] and these satellite-derived maps are used extensively in the study and exploration of the ocean floor.

Plastic pollution

[edit]In 2020 scientists created what may be the first scientific estimate of how much microplastic currently resides in Earth's seafloor, after investigating six areas of ~3 km depth ~300 km off the Australian coast. They found the highly variable microplastic counts to be proportionate to plastic on the surface and the angle of the seafloor slope. By averaging the microplastic mass per cm3, they estimated that Earth's seafloor contains ~14 million tons of microplastic – about double the amount they estimated based on data from earlier studies – despite calling both estimates "conservative" as coastal areas are known to contain much more microplastic pollution. These estimates are about one to two times the amount of plastic thought – per Jambeck et al., 2015 – to currently enter the oceans annually.[26][27][28]

Exploitation

[edit]

Deep sea mining is the extraction of minerals from the seabed of the deep sea. The main ores of commercial interest are polymetallic nodules, which are found at depths of 4–6 km (2.5–3.7 mi) primarily on the abyssal plain. The Clarion–Clipperton zone (CCZ) alone contains over 21 billion metric tons of these nodules, with minerals such as copper, nickel, cobalt and manganese making up roughly 30% of their weight.[30] It is estimated that the global ocean floor holds more than 120 million tons of cobalt, five times the amount found in terrestrial reserves.[31]

As of July 2024[update], only exploratory licenses have been issued, with no commercial-scale deep sea mining operations yet. The International Seabed Authority (ISA) regulates all mineral-related activities in international waters and has granted 31 exploration licenses so far: 19 for polymetallic nodules, mostly in the CCZ; 7 for polymetallic sulphides in mid-ocean ridges; and 5 for cobalt-rich crusts in the Western Pacific Ocean.[32] There is a push for deep sea mining to commence by 2025, when regulations by the ISA are expected to be completed.[33][34]

In April 2025, U.S. President Trump signed an Executive Order instructing the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to expedite permits for companies to mine in both international and U.S. territorial waters, citing the Deep Seabed Hard Minerals Resource Act of 1980.[35]

Deep sea mining is being considered in the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of countries, such as Norway, where in January 2024 the government announced its intention to allow companies to apply for exploration permits in 2025. In December 2024, Norway's plans to begin awarding exploration licenses were temporarily put on hold after the Socialist Left Party (SV) blocked the planned licensing round as part of negotiations over the government budget.[36][37] In 2022, the Cook Islands Seabed Minerals Authority (SBMA) granted three exploration licenses for cobalt-rich polymetallic nodules within their EEZ.[38] In 2025, it was announced that the Cook Islands had signed a deal with China focussed on deep-sea mining.[39] Papua New Guinea was the first country to approve a deep sea mining permit in state waters for the Solwara 1 project, despite three independent reviews highlighting significant gaps and flaws in the environmental impact statement.[40]

The most common commercial model of deep sea mining proposed involves a caterpillar-track hydraulic collector and a riser lift system bringing the harvested ore to a production support vessel with dynamic positioning, and then depositing extra discharge down the water column below 2,000 meters. Related technologies include robotic mining machines, as surface ships, and offshore and onshore metal refineries.[41][42] Though largely composed of nickel and manganese which are most widely used as key inputs into the steel industry, wind farms, solar energy, electric vehicles, and battery technologies use many of the deep-sea metals.[41] Electric vehicle batteries are a key driver of the critical metals demand that incentivizes deep sea mining, as well as demands for the production of aerospace and defense technologies, and infrastructure.[43][44]

The environmental impact of deep sea mining is controversial.[45][46] Environmental advocacy groups such as Greenpeace and the Deep Sea Mining Campaign[47] claimed that seabed mining has the potential to damage deep sea ecosystems and spread pollution from heavy metal-laden plumes.[48] Critics have called for moratoria[49][50] or permanent bans.[51] Opposition campaigns enlisted the support of some industry figures, including firms reliant on the target metals. Individual countries like Norway, Cook Islands, India, Brazil and others with significant deposits within their exclusive economic zones (EEZ's) are exploring the subject.[52][53]

As of 2021, the majority of marine mining used dredging operations in far shallower depths of less than 200 m, where sand, silt and mud for construction purposes is abundant, along with mineral rich sands containing ilmenite and diamonds.[54][55]In art and culture

[edit]On and under the seabed are archaeological sites of historic interest, such as shipwrecks and sunken towns. This underwater cultural heritage is protected by the UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage. The convention aims at preventing looting and the destruction or loss of historic and cultural information by providing an international legal framework.[56]

See also

[edit]- Bottom trawling – Fishing method by towing a net along the seafloor

- Demersal fish – Fish that live and feed on or near the bottom of seas or lakes

- Human outpost – Human habitats located in environments inhospitable for humans

- International waters – Water outside of national jurisdiction

- Manganese nodule – Mineral concretion on the sea bottom made of concentric layers of iron/manganese hydroxides

- Methane clathrate – Methane-water lattice compound

- Nepheloid layer – Layer of water in deep sea

- New Zealand foreshore and seabed controversy – Indigenous rights controversy

- Offshore geotechnical engineering – Sub-field of engineering concerned with human-made structures in the sea

- Petrological Database of the Ocean Floor (PetBD)

- Plate tectonics – Movement of Earth's lithosphere

- Research vessel – Ship or boat designed, modified, or equipped to carry out research at sea

- Riverbed – Channel bottom of a stream, river, or creek

- Seabed characterization – Partitioning of a seabed acoustic image into discrete physical entities or classes

- Seafloor mapping – Study of underwater depth of lake or ocean floors

- Seafloor massive sulfide deposits – Mineral deposits from seafloor hydrothermal vents

- Sediment Profile Imagery (SPI) – Technique for photographing the interface between the seabed and the overlying water

References

[edit]- ^ Kump, Lee R.; Kasting, James F.; Crane, Robert G. (2010). "Chapter 7. Circulation of the Solid Earth". The Earth System (3rd ed.). New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc. pp. 122–148. ISBN 978-0-321-59779-3.

- ^ "Open Ocean – Oceans, Coasts, and Seashores". National Park Service. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ NOAA. "Ocean floor features". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ Flood, Roger D.; Piper, D.J.W. (1997). "Preface: Depth Below Seafloor Conventions". In Flood; Piper; Klaus, A.; Peterson, L.C. (eds.). Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results. Vol. 155. p. 3. doi:10.2973/odp.proc.sr.155.200.1997.

we follow Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) meters below seafloor (mbsf) convention

- ^ Parkes, R. John; Henrik Sass (2007). Barton, Larry L. (ed.). Sulphate-reducing bacteria environmental and engineered systems. Cambridge University Press. pp. 329–358. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511541490.012. ISBN 978-0-521-85485-6. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

metres below the seafloor (mbsf)

- ^ a b Chester, Roy; Jickells, Tim (2012). "Chapter 15. The components of marine sediments". Marine Geochemistry (3rd ed.). Blackwell Publishing Ltd. pp. 321–351. ISBN 978-1-4051-8734-3.

- ^ Chester, Roy; Jickells, Tim (2012). "Chapter 13. Marine sediments". Marine Geochemistry (3rd ed.). Blackwell Publishing Ltd. pp. 273–289. ISBN 978-1-4051-8734-3.

- ^ a b c d "The Bottom of the Ocean," Marine Science

- ^ "Types of Marine Sediments", Article Myriad

- ^ Grobe, Hannes; Kiekmann, Bernhard; Hillenbrand, Claus-Dieter. "The memory of polar oceans" (PDF). AWI: 37–45.

- ^ Tripati, Aradhna, Lab 6-Marine Sediments, Marine Sediments Reading, E&SSCI15-1, UCLA, 2012

- ^ a b Benthos from the Census of Antarctic Marine Life website

- ^ US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "How does pressure change with ocean depth?". oceanservice.NOAA.gov.

- ^ Haeckel, E. 1891. Plankton-Studien. Jenaische Zeitschrift für Naturwissenschaft 25 / (Neue Folge) 18: 232–336. BHL.

- ^ βένθος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ "North American Benthological Society website". Archived from the original on 2008-07-05. Retrieved 2008-08-16.

- ^ Nehring, S. & Albrecht, U. (1997). Benthos und das redundant Benton: Neologismen in der deutschsprachigen Limnologie. Lauterbornia 31: 17-30, [1].

- ^ Giovanni Coco, Z. Zhou, B. van Maanen, M. Olabarrieta, R. Tinoco, I. Townend. Morphodynamics of tidal networks: Advances and challenges. Marine Geology Journal. 1 December 2013.

- ^ Sandwell, D. T.; Smith, W. H. F. (2006-07-07). "Exploring the Ocean Basins with Satellite Altimeter Data". NOAA/NGDC. Archived from the original on May 13, 1997. Retrieved 2007-04-21.

- ^ Charette, Matthew A.; Smith, Walter H. F. (June 2010). "The Volume of Earth's Ocean". Oceanography. 23 (2): 112–114. Bibcode:2010Ocgpy..23b.112C. doi:10.5670/oceanog.2010.51. hdl:1912/3862.

- ^ Calculated with GEBCO_2019 grid. (May 2020). "OER Depth Comparison Maps EEZ" (PDF). NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Retrieved September 19, 2025.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Braathen, Alvar; Brekke, Harald (7 January 2020). Chapter 1 Characterizing the Seabed: a Geoscience Perspective. Brill Nijhoff. pp. 21–35. doi:10.1163/9789004391567_003. ISBN 9789004391567. S2CID 210979539. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ a b "The Discovery of Hydrothermal Vents". Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. 11 June 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ Wefer, Gerold; Billet, David; Hebbeln, Dierk; Jorgensen, Bo Barker; Schlüter, Michael; Weering, Tjeerd C. E. Van (2013-11-11). Ocean Margin Systems. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-662-05127-6.

- ^ "Ocean Surface Topography". Science Mission Directorate. 31 March 2010. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ May, Tiffany (7 October 2020). "Hidden Beneath the Ocean's Surface, Nearly 16 Million Tons of Microplastic". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ "14 million tonnes of microplastics on sea floor: Australian study". phys.org. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ Barrett, Justine; Chase, Zanna; Zhang, Jing; Holl, Mark M. Banaszak; Willis, Kathryn; Williams, Alan; Hardesty, Britta D.; Wilcox, Chris (2020). "Microplastic Pollution in Deep-Sea Sediments From the Great Australian Bight". Frontiers in Marine Science. 7. Bibcode:2020FrMaS...776170B. doi:10.3389/fmars.2020.576170. ISSN 2296-7745. S2CID 222125532.

Available under CC BY 4.0.

Available under CC BY 4.0.

- ^ Muñoz-Royo, Carlos; Peacock, Thomas; Alford, Matthew H.; Smith, Jerome A.; Le Boyer, Arnaud; Kulkarni, Chinmay S.; Lermusiaux, Pierre F. J.; Haley, Patrick J.; Mirabito, Chris; Wang, Dayang; Adams, E. Eric; Ouillon, Raphael; Breugem, Alexander; Decrop, Boudewijn; Lanckriet, Thijs; Supekar, Rohit B.; Rzeznik, Andrew J.; Gartman, Amy; Ju, Se-Jong (27 July 2021). "Extent of impact of deep-sea nodule mining midwater plumes is influenced by sediment loading, turbulence and thresholds". Communications Earth & Environment. 2 (1): 148. Bibcode:2021ComEE...2..148M. doi:10.1038/s43247-021-00213-8. hdl:1721.1/138864.2.

- ^ "Massive deposit of battery-grade nickel on deep-sea floor gets confidence boost with new data". DeepGreen. 2021-01-27. Archived from the original on 2021-03-07. Retrieved 2021-04-08.

- ^ Mineral commodity summaries 2024 (Report). U.S. Geological Survey. 2024. p. 63. doi:10.3133/mcs2024.

- ^ "Exploration Contracts". International Seabed Authority. 17 March 2022. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ "Deep-sea mining's future still murky as negotiations end on mixed note". Mongabay. 2 April 2024.

- ^ Kuo, Lily (October 19, 2023). "China is set to dominate the deep sea and its wealth of rare metals". Washington Post. Retrieved 2024-02-14.

- ^ Bearak, Max; Dzombak, Rebecca; Stevens, Harry (April 24, 2025). "Trump Takes a Major Step Toward Seabed Mining in International Waters". The New York Times. Retrieved April 29, 2025.

- ^ "Greenpeace responds to Norway's proposal to licence first Arctic areas for deep sea mining". 26 June 2024.

- ^ McVeigh, Karen (December 2, 2024). "Norway forced to pause plans to mine deep sea in Arctic". The Guardian. Retrieved March 19, 2025.

- ^ "Cook Islands Seabed Minerals Authority - Map". Archived from the original on 2022-06-30. Retrieved 2022-07-06.

- ^ Inayatullah, Saim Dušan (February 22, 2025). "Cook Islands announces deep sea minerals deal with China". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved March 27, 2025.

- ^ "Campaign Reports | Deep Sea Mining: Out Of Our Depth". Deep Sea Mining: Out Of Our Depth. 2011-11-19. Archived from the original on 2019-12-13. Retrieved 2021-09-06.

- ^ a b SPC (2013). Deep Sea Minerals: Deep Sea Minerals and the Green Economy Archived 2021-11-04 at the Wayback Machine. Baker, E., and Beaudoin, Y. (Eds.) Vol. 2, Secretariat of the Pacific Community

- ^ "Breaking Free From Mining" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-12-23.

- ^ Shukman, David (2019-11-13). "Electric car future may depend on deep sea mining". BBC. Retrieved 2025-06-05.

- ^ "Securing Critical Minerals Vital to National Security, Official Says". USDOD. 2025-01-10. Archived from the original on 2025-04-29. Retrieved 2025-06-05.

- ^ Kim, Rakhyun E. (August 2017). "Should deep seabed mining be allowed?". Marine Policy. 82: 134–137. Bibcode:2017MarPo..82..134K. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2017.05.010. hdl:1874/358248.

- ^ Costa, Corrado; Fanelli, Emanuela; Marini, Simone; Danovaro, Roberto; Aguzzi, Jacopo (2020). "Global Deep-Sea Biodiversity Research Trends Highlighted by Science Mapping Approach". Frontiers in Marine Science. 7 384. Bibcode:2020FrMaS...7..384C. doi:10.3389/fmars.2020.00384. hdl:10261/216646.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Helen (November 2011). "Out of Our Depth: Mining the Ocean Floor in Papua New Guinea". Deep Sea Mining Campaign. MiningWatch Canada, CELCoR, Packard Foundation. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ Halfar, Jochen; Fujita, Rodney M. (18 May 2007). "Danger of Deep-Sea Mining". Science. 316 (5827): 987. doi:10.1126/science.1138289. PMID 17510349.

- ^ Doherty, Ben (2019-09-15). "Collapse of PNG deep-sea mining venture sparks calls for moratorium". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2025-02-08.

- ^ McVeigh, Karen (2020-03-12). "David Attenborough calls for ban on 'devastating' deep sea mining". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2025-02-08.

- ^ "Google, BMW, Volvo, and Samsung SDI sign up to WWF call for temporary ban on deep-sea mining". Reuters. 2021-03-31. Archived from the original on 2021-09-06. Retrieved 2021-09-06.

- ^ "SPC-EU Deep Sea Minerals Project - Home". dsm.gsd.spc.int. Archived from the original on 2021-09-06. Retrieved 2021-09-06.

- ^ "The Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) has refused an application by Chatham Rock Phosphate Limited (CRP)". Deepwater group. 2015. Archived from the original on 2016-01-24. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ John J. Gurney, Alfred A. Levinson, and H. Stuart Smith (1991) Marine mining of diamonds off the West Coast of Southern Africa, Gems & Gemology, p. 206

- ^ "Seabed Mining". The Ocean Foundation. 2010-08-07. Archived from the original on 2021-09-08. Retrieved 2021-09-06.

- ^ Safeguarding the Underwater Cultural Heritage UNESCO. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

Further reading

[edit]- Roger Hekinian: Sea Floor Exploration: Scientific Adventures Diving into the Abyss. Springer, 2014. ISBN 978-3-319-03202-3 (print); ISBN 978-3-319-03203-0 (eBook)

- Stéphane Sainson: Electromagnetic Seabed Logging. A new tool for geoscientists. Springer, 2016. ISBN 978-3-319-45353-8 (print); ISBN 978-3-319-45355-2 (eBook)

External links

[edit]- Understanding the Seafloor presentation from Cosee – the Center for Ocean Sciences Educational Excellence.

- Ocean Explorer (www.oceanexplorer.noaa.gov) – Public outreach site for explorations sponsored by the Office of Ocean Exploration.

- NOAA, Ocean Explorer Gallery, Submarine Ring of Fire 2006 Gallery, Submarine Ring of Fire 2004 Gallery – A rich collection of images, video, audio and podcast.

- NOAA, Ocean Explorer YouTube Channel

- Submarine Ring of Fire, Mariana Arc – Explore the volcanoes of the Mariana Arc, Submarine Ring of Fire.

- Age of the Ocean Floor National Geophysical Data Center

- Astonishing deep sea life on TED (conference)

Seabed

View on GrokipediaPhysical and Geological Characteristics

Structure and Composition

The seabed consists of unconsolidated to semi-consolidated sediments overlying the igneous oceanic crust, with sediment thickness averaging 300-500 meters globally but exceeding 1 kilometer in some abyssal regions. These sediments derive from multiple sources: terrigenous inputs from continental weathering and fluvial transport (primarily quartz, feldspar, and clay minerals like illite and smectite), biogenous accumulations such as calcareous ooze (from foraminifera and coccolithophores, rich in CaCO₃) and siliceous ooze (from diatoms and radiolarians, comprising opal-SiO₂), and minor hydrogenous components including metal-rich nodules and crusts. In deep-sea settings beyond the carbonate compensation depth (approximately 4-5 km), calcareous oozes dissolve, leaving dominant siliceous or red clay sediments with high iron oxide content.[5][8][9] The underlying oceanic crust, formed through seafloor spreading at mid-ocean ridges via decompression melting of upwelling mantle peridotite, measures 5-10 km thick and exhibits a layered structure defined by seismic velocities and drilling data from sites like the Ocean Drilling Program. The uppermost igneous layer (Layer 2) comprises extrusive basalts, including pillow lavas and hyaloclastites (0.5-2 km thick, porosity up to 10-15% from fracturing), overlying sheeted dike swarms representing magma conduits. This transitions to Layer 3, a plutonic sequence of gabbroic rocks (3-5 km thick), intruded cumulatively from fractional crystallization of basaltic melts. The crust's bulk composition is mafic, dominated by tholeiitic basalt (45-52% SiO₂, high in MgO, FeO, and CaO, density ~2.9 g/cm³), contrasting with the felsic continental crust.[10][11][12] Beneath the crust, the Mohorovičić discontinuity (Moho) separates it from the ultramafic upper mantle (peridotite, primarily olivine and pyroxene), at depths of 5-8 km below the sediment-water interface. The oceanic lithosphere, integrating crust and lithospheric mantle, totals 50-100 km thick, cooling and densifying conductively with distance from ridges (age up to 180 million years), which drives subsidence and bathymetric deepening at rates of ~2.5 km per 100 million years. Variations occur due to hotspots or off-axis magmatism, altering local thickness and composition, as evidenced by seismic refraction profiles and xenolith analyses.[13][14][15]Sediments and Deposits

![Marine sediment thickness map][float-right] Marine sediments consist primarily of unconsolidated particles that accumulate on the seabed, derived from terrigenous, biogenic, hydrogenous, and cosmogenous sources. Lithogenous or terrigenous sediments, comprising the majority near continental margins, originate from the weathering of continental rocks and are transported by rivers, winds, glaciers, and coastal erosion, resulting in compositions dominated by quartz, feldspars, and clay minerals.[16][5] These sediments grade from coarse sands and gravels on continental shelves to fine silts and clays in deeper waters, with particle size decreasing with distance from shore due to sorting by currents and waves.[17] Biogenous sediments form from the skeletal remains of marine organisms, such as calcareous oozes from foraminifera and coccolithophores in shallow to mid-depths, and siliceous oozes from diatoms and radiolarians in high-productivity upwelling zones.[16] These oozes cover approximately 48% of the seafloor, predominantly between 2,000 and 4,500 meters depth where dissolution rates are balanced by supply.[16] Hydrogenous sediments arise from precipitation of minerals directly from seawater, including phosphates, evaporites, and metal-rich precipitates, while cosmogenous contributions from extraterrestrial dust and micrometeorites remain negligible, less than 0.01% of total sediment volume. Global sediment thickness varies markedly, with GlobSed data indicating averages of under 100 meters in abyssal plains due to low deposition rates of about 1-5 mm per thousand years, contrasting with over 5 kilometers near passive continental margins where turbidites and hemipelagic settling dominate.[18] In the Pacific Ocean, for instance, sediment thickness reaches maxima exceeding 10 km in basins like the Bengal Fan, fed by major river systems.[18] Key seabed deposits include polymetallic nodules, potato-sized concretions of manganese and iron oxides enriched in nickel, copper, and cobalt, forming slowly over millions of years on abyssal plains at depths of 4,000-6,000 meters through precipitation onto nuclei like shell fragments.[19] These nodules, covering up to 20-30% of the seafloor in areas like the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, contain economically viable concentrations, with estimates of 21 billion tons globally.[19] Hydrothermal deposits, such as massive sulfide ores rich in copper, zinc, gold, and silver, precipitate near mid-ocean ridge vents where hot, mineral-laden fluids interact with cold seawater, forming chimneys and mounds at spreading centers.[20] Cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts accrete on seamounts and ridges at 400-2,500 meters, layering metals over exposed hard substrates at rates of 1-5 mm per million years.[21]Subsurface Layers and Depth Profiles

The subsurface layers of the seabed comprise stratified deposits of sediments overlying the basaltic oceanic crust, with thickness and composition varying regionally due to depositional history, proximity to land, and tectonic setting. In deep-ocean basins, sediments typically form a sequence beginning with fine-grained pelagic clays or biogenic oozes at the surface, transitioning downward to more compacted layers reflecting episodic deposition over millions of years. Sub-bottom profiling reveals these layers as acoustically distinct strata, often spanning from Holocene recent accumulations (millimeters per millennium) to Pleistocene and older sequences, with diagenetic alterations increasing density and reducing porosity with depth.[22][23] Sediment thickness profiles exhibit systematic variations tied to the age of the underlying crust: near mid-ocean ridges, where crust is less than 10 million years old, thicknesses are minimal, often under 100 meters, due to limited time for accumulation and high dissolution rates of carbonates in young, warmer waters. Thickness increases progressively with crustal age, reaching 500–1,000 meters or more in basins with crust exceeding 100 million years, as continuous rain of fine particles from above and lateral inputs build up over time. Global compilations, such as the GlobSed dataset, quantify this at 5-arc-minute resolution across ocean basins and marginal seas, showing averages around 500–600 meters but with extremes exceeding 2 kilometers in subsiding trenches or continental rises.[24][18] Depth profiles within these layers demonstrate progressive compaction and lithification: surface porosities of 70–90% in unconsolidated muds decrease to 30–50% at depths of several hundred meters, driven by overburden pressure and mineral recrystallization, as evidenced by core samples from ocean drilling programs. Density rises accordingly, from 1.3–1.5 g/cm³ near the seafloor to over 2.0 g/cm³ in deeper, indurated zones, influencing seismic wave propagation and resource potential. In continental margin settings, profiles differ markedly, with thicker terrigenous sequences (up to kilometers) incorporating coarser sands and silts interlayered with hemipelagic muds, reflecting fluvial and glacial inputs rather than purely pelagic settling.[25][23]Topography and Morphological Features

Continental Margins and Shelves

Continental margins form the transitional zone between continental crust and oceanic crust, consisting of the continental shelf, slope, and rise. These features extend from the shoreline seaward, with the shelf representing the shallow, submerged extension of the continent, typically submerged under less than 200 meters of water. Globally, continental shelves cover approximately 7.4% of the ocean surface and exhibit an average width of about 70 kilometers, though widths vary significantly from near-zero in tectonically active regions to over 1,000 kilometers on broad passive margins.[26][27] The continental shelf slopes gently at an average gradient of 0.1 degrees, facilitating sediment deposition from terrestrial sources and supporting high biological productivity due to shallow depths and nutrient inputs. At the shelf break, usually around 135 to 200 meters depth, the seafloor steepens into the continental slope, which descends to depths of about 3,000 meters at an average angle of 4 degrees, though locally it can reach 10 degrees or more. Submarine canyons often incise the slope, channeling sediments and organic matter downslope via turbidity currents.[27][28][29] Beyond the slope lies the continental rise, a wedge-shaped depositional feature formed by the accumulation of sediments from the slope, grading into the abyssal plains. Continental margins are classified as active or passive based on tectonic setting: active margins, associated with plate convergence, feature narrower shelves, steeper slopes prone to earthquakes and volcanism, as seen along the Pacific Ring of Fire; passive margins, distant from plate boundaries, exhibit wider shelves and thicker sediment layers, exemplified by the Atlantic coasts of North America and Europe. This distinction arises from the absence of subduction or rifting at passive margins, allowing unhindered sediment buildup over geological time.[30][31]Abyssal Plains and Ocean Basins

Abyssal plains constitute vast, nearly flat regions of the deep ocean floor, occurring at depths generally between 3,000 and 6,000 meters, with surface slopes typically less than 1:1,000 due to the accumulation of thick sedimentary layers that smooth underlying irregular basaltic crust.[32][33] These plains form primarily through the gradual deposition of fine-grained particles, such as clay and silt, sourced from continental erosion, biogenic remains, and cosmic dust, which blanket volcanic topography created at mid-ocean ridges.[34] Sediment thicknesses on abyssal plains range from several hundred meters to over 1 kilometer in older regions, reflecting millions of years of low-rate accumulation at 1-10 mm per thousand years.[35][36] Ocean basins encompass the expansive central depressions of the major oceans, such as the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian basins, where abyssal plains dominate the seafloor morphology, interrupted by features like mid-ocean ridges, seamounts, and fracture zones.[37] These basins overlie oceanic lithosphere thinned by plate tectonics, with basaltic crust covered by progressively thicker sediments away from spreading centers, enabling the development of flat plains that cover approximately 70% of the total ocean floor area.[3] Abyssal plains within basins exhibit minimal relief, often less than 100 meters over tens of kilometers, sustained by hemipelagic settling and occasional turbidity currents that redistribute material from continental margins.[38] Examples include the Argentine Abyssal Plain in the South Atlantic, spanning over 1,000 km in width with sediment depths exceeding 500 meters.[35] The geological stability of abyssal plains and basins contrasts with their dynamic formation history, as seafloor spreading continuously rejuvenates crust near ridges while distant plains accumulate undisturbed sediments, preserving records of paleoceanographic conditions.[39] Bottom currents, driven by density gradients in deep waters like Antarctic Bottom Water, sculpt subtle bedforms such as elongated mounds or channels on some plains, though these rarely exceed a few meters in height.[40] Such features underscore the interplay of sedimentation and erosion in maintaining the plains' characteristic flatness over geologic timescales.[34]Seamounts, Ridges, and Trenches

Seamounts are isolated underwater mountains rising abruptly from the deep ocean floor, typically with heights exceeding 1,000 meters and steep slopes greater than 20 degrees.[41] They form primarily through volcanic activity at hotspots or mid-ocean ridges, where magma erupts and builds conical structures that eventually become extinct as tectonic plates move away from the source.[42] Global estimates indicate over 100,000 seamounts taller than 1,000 meters exist across all ocean basins, though improved bathymetric surveys continue to reveal thousands more, with recent predictions adding over 4,000 in the Pacific alone.[43][44] Prominent examples include the Hawaiian-Emperor seamount chain, extending over 5,800 kilometers northwest from Hawaii, formed by the Pacific plate drifting over a mantle hotspot.[45] Mid-ocean ridges constitute the most extensive topographic feature on the seabed, forming a global network of divergent plate boundaries where new oceanic crust is generated through seafloor spreading.[46] This system spans approximately 65,000 kilometers, encircling the planet like a seam and comprising segments such as the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and East Pacific Rise.[47] Characterized by rift valleys 1-2 kilometers deep flanked by elevated basaltic plateaus rising 2-3 kilometers above surrounding abyssal plains, ridges exhibit frequent earthquakes and hydrothermal vents due to magma upwelling and crustal thinning.[46] The process drives plate tectonics, with spreading rates varying from 2 centimeters per year at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge to over 15 centimeters per year at the East Pacific Rise, influencing ocean basin evolution over millions of years.[48] Oceanic trenches represent the deepest and most extreme morphological features of the seabed, formed at convergent plate boundaries where one tectonic plate subducts beneath another, creating curved depressions often exceeding 6,000 meters in depth.[49] The Mariana Trench in the western Pacific holds the record, with Challenger Deep reaching 10,984 meters below sea level, a product of the Pacific plate subducting under the Mariana plate at rates up to 10 centimeters per year.[50] These features concentrate along the Pacific Ring of Fire, including the Peru-Chile Trench (8,065 meters deep) and Philippine Trench (10,540 meters), where intense compression generates powerful earthquakes and volcanic arcs.[51] Trenches accumulate thick sediment fills from eroding continental margins but remain profoundly steep-sided due to ongoing subduction, shaping ocean floor asymmetry and facilitating deep-water circulation.[49]Benthic Biology and Ecosystems

Benthic Organisms and Adaptations

Benthic organisms inhabit the seabed across depths from intertidal zones to abyssal plains, categorized as epifauna living on the surface, infauna burrowing within sediments, and meiofauna occupying interstitial spaces between particles. Epifauna include sessile forms like corals, sponges, and barnacles attached to hard substrates, while mobile species such as echinoderms (e.g., starfish and sea urchins) crawl or attach via tube feet. Infauna, dominated by polychaete worms and bivalves, excavate burrows to access nutrients and evade predators, with adaptations like extensible proboscides for feeding on detritus. Meiofauna, typically nematodes and copepods smaller than 1 mm, thrive in pore waters due to high surface-to-volume ratios facilitating oxygen diffusion in low-oxygen sediments.[52] Deep-sea benthic fauna exhibit physiological adaptations to extreme hydrostatic pressure exceeding 1000 atmospheres, including pressure-resistant enzymes and proteins that maintain functionality without denaturation, alongside reduced skeletal mineralization and higher tissue water content to minimize compressibility effects. Low temperatures near 2–4°C induce metabolic suppression, with basal rates 10–20 times lower than in shallow-water counterparts, conserving energy in food-scarce environments where organic flux diminishes exponentially with depth. Sensory adaptations compensate for perpetual darkness, featuring expanded olfactory organs, mechanoreceptors along elongated bodies for detecting vibrations, and absence or reduction of eyes in many species, though some retain rudimentary photoreception or employ bioluminescence for predation or camouflage.[53][54] In oxygen minimum zones (OMZs) at intermediate depths (200–1000 m), benthic organisms adapt via high-affinity hemoglobins and enlarged gill surfaces to extract dissolved oxygen below 0.5 ml/L, enabling aerobic metabolism where shallow species perish. Feeding strategies emphasize detritivory, with holothurians (sea cucumbers) processing sediments through tentaculate oral apparatuses, ingesting up to 20 times their body weight daily to harvest sparse organic matter. Predatory infauna like nereid polychaetes use chemosensory cues to ambush prey, while epifaunal suspension feeders deploy mucus nets or cirri to capture sinking particulates.[55][56] At hydrothermal vents, chemosynthetic symbioses represent a paradigm shift from photosynthetic dependence, where vestimentiferan tubeworms (e.g., Riftia pachyptila) lack digestive systems but host sulfur-oxidizing bacteria in trophosomes, deriving energy from hydrogen sulfide oxidation at rates supporting growth to 2.4 m lengths despite null primary production from sunlight. Shrimp like Rimicaris exoculata cultivate bacterial epibionts on gill chambers for nutrition, tolerating temperatures up to 40°C via heat-shock proteins and sulfide-detoxifying enzymes. These adaptations underscore causal linkages between geochemical fluxes and faunal persistence in isolated, aphotic ecosystems, with communities exhibiting elevated biomass densities exceeding 30 kg/m² near active chimneys.[57][56]Biodiversity Patterns and Ecological Dynamics

Benthic biodiversity on the seabed displays pronounced zonation tied to depth gradients, with species richness generally declining from continental shelves toward abyssal depths due to decreasing organic flux and increasing environmental stability. A unimodal pattern often emerges, peaking between 1000 and 3000 meters where mid-slope habitats (e.g., 1220–1350 m) sustain elevated diversities through intermediate levels of disturbance and nutrient availability.[58] [59] This contrasts with shallower shelf zones, where higher productivity supports dense but less specialized assemblages, and deeper abyssal plains, characterized by sparse, opportunistic detritivores adapted to low-energy conditions. Latitudinal variations modulate these patterns, with tropical shelves exhibiting greater diversity than polar counterparts, though deep-sea gradients show less pronounced equatorial peaks.[60] [61] Isolated features disrupt uniform depth-related declines, creating hotspots of endemism and biomass. Seamounts, covering about 4.7% of the seafloor, function as oases via topographic enhancement of currents, fostering upwelling that concentrates phytoplankton detritus and retains larvae, thereby elevating local species richness—often including habitat-forming corals and sponges that structure communities.[62] [63] Hydrothermal vents, conversely, host low-diversity but high-density assemblages reliant on chemosynthetic primary production, with over 590 vent-specific species documented, including symbiotic tubeworms and mussels oxidizing sulfide via bacterial partners.[64] These ecosystems exhibit rapid succession tied to fluid chemistry, with pioneer microbes colonizing new vents within days, followed by metazoans over months to years.[65] Ecological dynamics in benthic systems emphasize efficient recycling amid energy scarcity, with food webs predominantly detritus-driven in non-chemosynthetic habitats. Surface-derived particulate organic carbon sinks to the seabed, fueling microbial decomposition and trophic transfer to deposit feeders, suspension feeders, and predators, where benthic communities process up to 10–50% of flux via bioturbation and remineralization.[66] Nutrient cycling hinges on this, as bacteria and viruses mediate carbon and nitrogen turnover, with deep-sea sediments acting as long-term sinks modulated by bottom currents and oxygenation.[67] In vent and seep enclaves, dynamics shift to sulfide- and methane-based autotrophy, supporting short, efficient chains with minimal trophic levels and high turnover rates, though succession halts with fluid cessation, leading to community collapse within decades.[68] Climate-driven fluctuations in export production propagate downward, altering benthic standing stocks by 20–50% over glacial-interglacial cycles via organic supply variations.[69] , the first dedicated global oceanographic voyage, which conducted 492 deep-sea soundings, 133 bottom dredges, and 151 trawls, disproving the prevailing azoic theory that no life existed below 300 fathoms and documenting diverse seabed biota, including over 4,000 new species.[74][75] The expedition also identified key geomorphic features like the Mariana Trench (over 8,000 meters deep) and ferromanganese nodules on abyssal plains, yielding 50 volumes of reports that established oceanography as a science.[76][77] The early 20th century introduced acoustic methods, with the first single-beam echo sounders deployed in the 1920s–1930s, enabling continuous depth profiling via sound wave reflection; by 1930, the German vessel Planet used such technology during cable-laying operations to map seafloor topography more efficiently than lines.[78][79] Manned submersibles advanced direct observation: William Beebe's Bathysphere dives (1930–1934) reached 923 meters off Bermuda, providing visual insights into benthic habitats, while the bathyscaphe Trieste's 1960 descent to 10,911 meters in the Challenger Deep confirmed extreme pressures and sparse but resilient life forms on the hadal seabed.[80][81] These efforts, complemented by post-World War II coring and dredging, laid groundwork for understanding sediment layers and tectonic features, though coverage remained sparse until satellite altimetry in the 1970s.[82]Modern Mapping and Imaging Technologies

Modern seabed mapping relies primarily on acoustic technologies, particularly multibeam echosounders (MBES), which emit fan-shaped acoustic pulses to measure depths across wide swaths, enabling high-resolution bathymetric surveys from surface vessels.[83] Developed from narrow-beam prototypes in the 1960s, the first operational multibeam system was installed in 1963, marking a shift from single-beam echo sounders that provided only nadir profiles to comprehensive areal coverage.[84] Contemporary MBES systems, such as the Kongsberg EM300, operate in water depths from 10 meters to over 5,000 meters, achieving resolutions down to meters depending on frequency and depth, with backscatter data revealing seabed composition and features like ridges or sediments.[85] Autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) complement ship-based sonar by accessing confined or hazardous areas for finer-scale imaging. AUVs, operating untethered, deploy multibeam and side-scan sonars to produce resolutions superior to hull-mounted systems, as demonstrated by MBARI's seafloor mapping AUVs that capture detailed terrain unattainable from surface platforms.[86] ROVs, connected via umbilicals for real-time control, integrate high-definition cameras, laser scanners, and synthetic aperture sonar for targeted inspections, supporting applications from shipwreck surveys to coral mapping.[87] Emerging integrations, such as underwater lidar, promise sub-centimeter resolutions for microtopography, though limited by water clarity and range.[88] Satellite altimetry provides global-scale preliminary bathymetry by detecting seafloor-induced gravity anomalies that perturb sea surface heights, filling gaps in acoustic data coverage. Combining altimeter-derived gravity with sparse ship soundings yields uniform-resolution maps, as in the 1997 global topography model blending satellite and direct measurements.[89] Recent missions enhance accuracy to 1-mGal for gravity, enabling predictions of features like seamounts in unsurveyed basins.[90] The Seabed 2030 initiative, launched in 2017 by the Nippon Foundation and GEBCO, coordinates these technologies to map the entire ocean floor at 100-meter resolution by 2030, achieving 27.3% coverage as of June 2025 through crowdsourced data exceeding 94 million square kilometers.[91] Advances like sparse-aperture multibeam sonars aim to accelerate deep-sea surveys cost-effectively from surface ships.[92] Hyperspectral imaging from submersibles adds spectral data for material identification, autonomous systems providing unbiased seabed maps.[93]Recent Expeditions and Discoveries

In 2025, a Chinese submersible expedition to the Mariana Trench identified dense communities of amphipods, polychaete worms, and mollusks inhabiting depths approaching 10 kilometers, marking some of the deepest verified animal aggregations observed to date.[94] These findings, collected via the Fendouzhe vehicle, highlighted resilient benthic ecosystems sustained by chemosynthetic processes amid extreme pressure and darkness.[94] The Schmidt Ocean Institute's RV Falkor (too) conducted multiple expeditions in 2025, including explorations off Uruguay where remotely operated vehicles documented over 30 suspected new species amid flourishing cold-water coral reefs on the seabed.[95] These sites, at depths exceeding 1,000 meters, revealed diverse benthic habitats including sponge gardens and anemone fields, contributing to biodiversity inventories in understudied Atlantic margins.[96] Earlier in the year, a Schmidt-led voyage to the South Sandwich Islands uncovered potential new species on seamounts, the shallowest known hydrothermal vents in the region, and a juvenile colossal squid, underscoring the prevalence of endemic megafauna in remote abyssal zones.[95] NOAA's Okeanos Explorer supported telepresence-enabled missions in 2025, such as mapping and sampling in the tropical Atlantic, where high-resolution sonar delineated previously unmapped seabed features including fracture zones and sediment drifts.[97] These efforts, integrated with environmental DNA analysis, identified novel microbial assemblages and debris accumulations on abyssal plains, advancing causal models of deep-ocean carbon cycling.[98] Complementing this, the Ocean Exploration Trust's Nautilus expedition in the Cook Islands that October revealed rich benthic biodiversity, including chemosynthetic communities around seeps, via real-time video feeds from ROVs.[99] Microbial surveys in hadal trenches, reported in March 2025, sequenced over 7,564 novel species-level genomes from Mariana sediments, comprising nearly 90% previously unknown taxa adapted to ultrahigh-pressure conditions.[100] Off Japan, a 2025 deep-sea dive captured a new pleurobranch sea snail species at record depths for the genus, exhibiting morphological adaptations like reduced eyes and chemoreceptive enhancements.[101] These discoveries, enabled by autonomous underwater vehicles and submersibles, have mapped an additional increment toward the Seabed 2030 goal, with 27.3% of global seafloor resolved at high resolution by mid-2025.[102]Resources and Economic Significance

Mineral Deposits and Critical Resources

The seabed contains vast deposits of minerals vital for advanced technologies, including polymetallic nodules, cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts, and seafloor massive sulfides, which supply critical elements like nickel, cobalt, copper, manganese, and rare earths. These resources form through geological processes such as precipitation from seawater, hydrothermal activity, and sediment interaction, often in deep-ocean environments beyond national jurisdictions.[103][104] Polymetallic nodules, roughly potato-sized rounded accretions of manganese and iron oxides, lie scattered or in carpets on abyssal plains at depths of 4,000 to 6,000 meters. They incorporate metals precipitated from overlying seawater and pore fluids over millions of years, with typical compositions including 29% manganese, 1.3% nickel, 1.2% copper, and 0.2% cobalt by weight. Highest abundances occur in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) of the eastern Pacific Ocean, where nodules can cover up to 35% of the seafloor in patches 1-5 km wide and 10-18 km long.[105][106][107] The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that CCZ nodules hold more nickel, cobalt, copper, and manganese than all known land-based reserves combined.[108] Cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts encrust hard substrates such as seamounts, ridges, and plateaus at depths generally between 400 and 4,000 meters. These hydrogenetic deposits grow slowly at rates of 1-5 mm per million years, concentrating cobalt up to 2% alongside platinum-group metals, titanium, and rare earth elements. Significant accumulations are found on Pacific seamounts and the Mid-Atlantic Ridge flanks, with thicknesses reaching 25 cm in optimal sites.[103][109] Their cobalt content addresses shortages in terrestrial supplies, crucial for lithium-ion batteries and superalloys.[104] Seafloor massive sulfides form chimney-like structures and mounds near hydrothermal vents along mid-ocean ridges and volcanic arcs, at depths exceeding 2,000 meters. These polymetallic deposits, resulting from high-temperature fluid circulation through oceanic crust, are enriched in copper (up to 8%), zinc (5-10%), lead, gold (up to 10 g/t), and silver (up to 1,000 g/t). Notable occurrences include the East Pacific Rise and Mariana Back-Arc, with individual deposits spanning tens to hundreds of meters.[110][111] Exploration by the International Seabed Authority has delineated over 20 contract areas for sulfides since 2010, highlighting their potential for base and precious metals.[109] These seabed resources are deemed critical due to their role in electric vehicle batteries, wind turbines, and electronics, amid rising demand and terrestrial supply vulnerabilities. USGS assessments identify 37 of 50 critical minerals in U.S. outer continental shelf deposits, underscoring the seafloor's strategic importance.[112][113] However, accurate global reserve quantification remains challenging, relying on sparse sampling and acoustic surveys prone to underestimation in heterogeneous terrains.[103]Hydrocarbon and Other Energy Reserves

Offshore hydrocarbon reserves, primarily oil and natural gas trapped in sedimentary formations beneath the seabed, constitute a major component of global energy supplies. Proven reserves in offshore fields, including those in the Gulf of Mexico, North Sea, and emerging deepwater basins like Guyana's Stabroek Block, account for approximately 25-30% of total global crude oil reserves, estimated at 1.567 trillion barrels as of the end of 2024.[114] In the U.S. Gulf of Mexico Outer Continental Shelf alone, recoverable reserves are assessed at 4.32 billion barrels of oil and 11.3 trillion cubic feet of natural gas across 782 fields.[115] Recent deepwater discoveries, such as Guyana's offshore fields exceeding 11 billion barrels of oil equivalent and Namibia's Orange Basin with over 2 billion barrels of oil equivalent, highlight untapped potential in frontier areas, driven by advancements in seismic imaging and drilling technologies.[116] Methane hydrates, ice-like crystalline structures of methane and water embedded in seabed sediments at depths greater than 500 meters, represent an enormous but largely uncommercialized resource. These deposits occur globally in continental margins and Arctic permafrost regions, with U.S. Geological Survey assessments indicating potential volumes equivalent to twice the methane in all known conventional gas reserves, though recovery rates remain uncertain due to stability challenges upon depressurization.[117] [118] Experimental extractions in sand-hosted hydrates, tested in Japan and Canada, have demonstrated technical feasibility but not economic viability at scale, with risks of seabed destabilization and methane release complicating development.[119] Beyond hydrocarbons, seabed-associated energy potentials include limited geothermal resources from hydrothermal vents and fracture zones, though these are site-specific and dwarfed by conventional sources. Tidal energy infrastructure, such as seabed-mounted turbines harnessing kinetic flows, offers renewable generation but relies on predictable tidal cycles rather than stored reserves, with global capacity under 1 gigawatt as of 2024.[120] Overall, hydrocarbon dominance persists due to established extraction economics, while hydrate and alternative seabed energies face geophysical and infrastructural hurdles.Exploitation Efforts and Technologies

Deep-Sea Mining Operations and Prototypes

Deep-sea mining operations target polymetallic nodules, cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts, and seafloor massive sulfides in areas beyond national jurisdiction, primarily in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) of the Pacific Ocean. Proposed systems involve autonomous or remotely operated collector vehicles that traverse the seabed at depths of 4,000 to 6,000 meters, using tracks or skids to disturb and vacuum nodules from the sediment while minimizing habitat destruction. Collected nodules are lifted via a riser pipe to a surface vessel for dewatering, separation from tailings, and initial processing, with processed ore stored for transport to land-based refineries. Tailings and excess water are discharged back into the ocean, generating sediment plumes that disperse horizontally and vertically, potentially affecting midwater and benthic ecosystems.[105][121][122] No commercial-scale deep-sea mining operations have commenced as of October 2025, with activities limited to exploration contracts issued by the International Seabed Authority (ISA), totaling 31 for public and private entities. Prototype testing has focused on nodule collection systems, with early trials dating to 1970 using hydraulic dredges and, by the late 1970s, U.S. consortia deploying pre-prototype miners that recovered thousands of tons of nodules in short bursts. Modern prototypes emphasize selectivity and reduced sediment disturbance; for instance, Global Sea Mineral Resources (GSR), a subsidiary of DEME Group, conducted an industrial-scale collector trial in the CCZ in April 2024 using the Patania II vehicle, which operated at 4,400 meters and collected nodules while generating monitored plumes.[123][109][105] The Metals Company (TMC) has advanced its NORI-D prototype collector vehicle (PCV), tested in the CCZ, integrating nodule harvesting, riser lifting, and onboard processing to achieve continuous operation rates of up to 400 tons per hour. In January 2025, a pre-prototype collector trial at 4,500 meters demonstrated plume dynamics, with initial dynamic plumes descending rapidly before forming ambient plumes advected by currents. Other efforts include China's COMRA developing nodule mining prototypes with integrated engineering designs and Japan's national jurisdiction tests at Minamitorishima for rare earth elements, though international operations remain in the prototype phase pending ISA exploitation regulations. TMC announced plans in March 2025 to seek U.S. permits under existing mining codes for high-seas extraction, aiming for potential operations in 2026 or later.[121][122][124][125]Regulatory Frameworks and International Agreements

The primary international framework governing seabed activities beyond national jurisdiction, known as "the Area," is established by Part XI of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), adopted in 1982 and entered into force on November 16, 1994.[126] UNCLOS designates mineral resources in the Area as the "common heritage of mankind," prohibiting national appropriation and requiring activities to be carried out for the benefit of all humankind through an international regime.[126] The International Seabed Authority (ISA), headquartered in Kingston, Jamaica, was created under UNCLOS to administer this regime, with 169 member states as of 2025, authorizing exploration and future exploitation contracts while ensuring environmental protection, equitable benefit-sharing, and technology transfer.[127] The ISA's regulatory powers are operationalized through the "Mining Code," a set of rules, regulations, and procedures for prospecting, exploration, and exploitation of seabed minerals such as polymetallic nodules, sulfides, and crusts.[128] Exploration regulations have been adopted for these resources since 2000, 2010, and 2012, respectively, leading to 31 active contracts covering approximately 1.3 million square kilometers as of June 2025, primarily in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone of the Pacific Ocean.[109] Exploitation regulations remain under development, with the ISA Council targeting adoption by July 2023 but failing to finalize them; sessions in March and July 2025 concluded without approval amid debates over environmental standards, royalty structures, and profit-sharing formulas.[123][129] Within national jurisdictions, including exclusive economic zones (EEZs) extending 200 nautical miles from baselines and extended continental shelves up to 350 nautical miles (delineated via the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf), seabed exploitation falls under sovereign rights governed by domestic laws compliant with UNCLOS Articles 77 and 82.[126] For instance, the United States, not a party to UNCLOS, regulates deep seabed mining through the Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act of 1980, administered by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which issued updated rules for licenses and permits on July 7, 2025, to facilitate exploration and recovery.[130] A U.S. Executive Order on April 24, 2025, directed acceleration of permits for critical minerals on the U.S. continental shelf, bypassing ISA processes for areas under U.S. jurisdiction.[131] Complementary agreements include the 2023 Agreement on Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ Agreement), which entered into force on future ratification and addresses conservation in the Area while deferring mineral resource activities to the ISA.[132] This framework emphasizes precaution but has faced criticism for potential overlaps that could delay mineral development without addressing resource scarcity driven by green energy demands. ISA decisions require consensus among member states, often stalling progress due to calls for moratoriums from environmental advocates, despite empirical evidence from exploration indicating manageable localized impacts under proposed mitigation measures.[133][134]Debates and Environmental Considerations

Potential Ecological Impacts and Resilience

could diversify supply chains and reduce reliance on terrestrial mining, which often involves higher social and environmental costs in developing regions.[142] However, economic models indicate modest revenues for International Seabed Authority (ISA) member states; for instance, a single polymetallic nodule mine might generate $55–165 million annually in ISA revenues, translating to an average of $42,000–$7.35 million per year across 169 members after distribution.[143] [144] These figures suggest limited direct fiscal benefits for developing countries, potentially offset by depressed metal prices that could erode royalties from existing land-based operations.[145] Environmental risks, including sediment plumes that may smother benthic organisms and alter food webs over hundreds of kilometers, complicate the calculus, though the scale and persistence of impacts remain uncertain due to limited baseline data.[146] Critics from conservation groups emphasize irreversible biodiversity loss in largely unexplored habitats, while industry analyses counter that deep-sea operations could avoid the deforestation, water pollution, and community displacements common in onshore mining.[147] [148] Quantifying ecosystem service values—such as carbon sequestration or fishery productivity—is challenging, but preliminary assessments indicate potential fishery revenue losses in regions like the CCZ could exceed projected mining gains if plumes affect pelagic species.[149] Policy perspectives diverge sharply under the ISA framework, which mandates equitable benefit-sharing from "the Area" beyond national jurisdictions while protecting the marine environment.[150] Developing nations, including Nauru and Tonga, advocate proceeding with exploitation contracts to fund development, viewing delays as perpetuating resource inequities favoring wealthy consumers of minerals.[151] Conversely, 32 ISA members, including Germany and Canada, support a precautionary pause or moratorium until environmental regulations are robust, citing gaps in impact assessments and risks to global ocean health.[152] The United States, via a 2025 executive order, pushes for accelerated access to seabed resources to secure domestic supply chains, bypassing ISA timelines amid stalled multilateral talks.[153] These tensions reflect broader debates on whether seabed mining enables a low-carbon transition or risks preempting less invasive alternatives like recycling and substitution, with empirical evidence on net socioeconomic gains still emerging.[148]References

- https://www.coastalwiki.org/wiki/Coastal_and_marine_sediments

- https://www.coastalwiki.org/wiki/Continental_shelf_habitat

- https://www.coastalwiki.org/wiki/Benthos