Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Photic zone

View on Wikipedia| Aquatic layers |

|---|

| Stratification |

| See also |

The photic zone (or euphotic zone, epipelagic zone, or sunlight zone) is the uppermost layer of a body of water that receives sunlight, allowing phytoplankton to perform photosynthesis. It undergoes a series of physical, chemical, and biological processes that supply nutrients into the upper water column. The photic zone is home to the majority of aquatic life due to the activity (primary production) of the phytoplankton. The thicknesses of the photic and euphotic zones vary with the intensity of sunlight as a function of season and latitude and with the degree of water turbidity. The bottommost, or aphotic, zone is the region of perpetual darkness that lies beneath the photic zone and includes most of the ocean waters.[1]

Photosynthesis in photic zone

[edit]In the photic zone, the photosynthesis rate exceeds the respiration rate. This is due to the abundant solar energy which is used as an energy source for photosynthesis by primary producers such as phytoplankton. These phytoplankton grow extremely quickly because of sunlight's heavy influence, enabling it to be produced at a fast rate. In fact, ninety five percent of photosynthesis in the ocean occurs in the photic zone. Therefore, if we go deeper, beyond the photic zone, such as into the compensation point, there is little to no phytoplankton, because of insufficient sunlight.[2] The zone which extends from the base of the euphotic zone to the aphotic zone is sometimes called the dysphotic zone.[3]

Life in the photic zone

[edit]

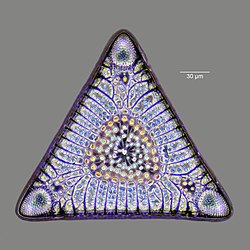

Ninety percent of marine life lives in the photic zone, which is approximately two hundred meters deep. This includes phytoplankton (plants), including dinoflagellates, diatoms, cyanobacteria, coccolithophores, and cryptomonads. It also includes zooplankton, the consumers in the photic zone. There are carnivorous meat eaters and herbivorous plant eaters. Next, copepods are the small crustaceans distributed everywhere in the photic zone. Finally, there are nekton (animals that can propel themselves, like fish, squids, and crabs), which are the largest and the most obvious animals in the photic zone, but their quantity is the smallest among all the groups.[4] Phytoplankton are microscopic plants living suspended in the water column that have little or no means of motility. They are primary producers that use solar energy as a food source.[citation needed]

"Detritivores and scavengers are rare in the photic zone. Microbial decomposition of dead organisms begins here and continues once the bodies sink to the aphotic zone where they form the most important source of nutrients for deep sea organisms."[5] The depth of the photic zone depends on the transparency of the water. If the water is very clear, the photic zone can become very deep. If it is very murky, it can be only fifty feet (fifteen meters) deep.[citation needed]

Animals within the photic zone use the cycle of light and dark as an important environmental signal, migration is directly linked to this fact, fishes use the concept of dusk and dawn when its time to migrate, the photic zone resembles this concept providing a sense of time. These animals can be herrings and sardines and other fishes that consistently live within the photic zone.[6]

Nutrient uptake in the photic zone

[edit]Due to biological uptake, the photic zone has relatively low levels of nutrient concentrations. As a result, phytoplankton doesn't receive enough nutrients when there is high water-column stability.[7] The spatial distribution of organisms can be controlled by a number of factors. Physical factors include: temperature, hydrostatic pressure, turbulent mixing such as the upward turbulent flux of inorganic nitrogen across the nutricline.[8] Chemical factors include oxygen and trace elements. Biological factors include grazing and migrations.[9] Upwelling carries nutrients from the deep waters into the photic zone, strengthening phytoplankton growth. The remixing and upwelling eventually bring nutrient-rich wastes back into the photic zone. The Ekman transport additionally brings more nutrients to the photic zone. Nutrient pulse frequency affects the phytoplankton competition. Photosynthesis produces more of it. Being the first link in the food chain, what happens to phytoplankton creates a rippling effect for other species. Besides phytoplankton, many other animals also live in this zone and utilize these nutrients. The majority of ocean life occurs in the photic zone, the smallest ocean zone by water volume. The photic zone, although small, has a large impact on those who reside in it.

Photic zone depth

[edit]

The depth is, by definition, where radiation is degraded down to 1% of its surface strength.[10] Accordingly, its thickness depends on the extent of light attenuation in the water column. As incoming light at the surface can vary widely, this says little about the net growth of phytoplankton. Typical euphotic depths vary from only a few centimetres in highly turbid eutrophic lakes, to around 200 meters in the open ocean. It also varies with seasonal changes in turbidity, which can be strongly driven by phytoplankton concentrations, such that the depth of the photic zone often decreases as primary production increases. Moreover, the respiration rate is actually greater than the photosynthesis rate. The reason why phytoplankton production is so important is because it plays a prominent role when interwoven with other food webs.

Light attenuation

[edit]

and in the process called photosynthesis absorb light

in the blue and red range through photosynthetic pigments

Most of the solar energy reaching the Earth is in the range of visible light, with wavelengths between about 400-700 nm. Each colour of visible light has a unique wavelength, and together they make up white light. The shortest wavelengths are on the violet and ultraviolet end of the spectrum, while the longest wavelengths are at the red and infrared end. In between, the colours of the visible spectrum comprise the familiar “ROYGBIV”; red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet.[12]

Water is very effective at absorbing incoming light, so the amount of light penetrating the ocean declines rapidly (is attenuated) with depth. At one metre depth only 45% of the solar energy that falls on the ocean surface remains. At 10 metres depth only 16% of the light is still present, and only 1% of the original light is left at 100 metres. No light penetrates beyond 1000 metres.[12]

In addition to overall attenuation, the oceans absorb the different wavelengths of light at different rates. The wavelengths at the extreme ends of the visible spectrum are attenuated faster than those wavelengths in the middle. Longer wavelengths are absorbed first; red is absorbed in the upper 10 metres, orange by about 40 metres, and yellow disappears before 100 metres. Shorter wavelengths penetrate further, with blue and green light reaching the deepest depths.[12]

This is why things appear blue underwater. How colours are perceived by the eye depends on the wavelengths of light that are received by the eye. An object appears red to the eye because it reflects red light and absorbs other colours. So the only colour reaching the eye is red. Blue is the only colour of light available at depth underwater, so it is the only colour that can be reflected back to the eye, and everything has a blue tinge under water. A red object at depth will not appear red to us because there is no red light available to reflect off of the object. Objects in water will only appear as their real colours near the surface where all wavelengths of light are still available, or if the other wavelengths of light are provided artificially, such as by illuminating the object with a dive light.[12]

Water in the open ocean appears clear and blue because it contains much less particulate matter, such as phytoplankton or other suspended particles, and the clearer the water, the deeper the light penetration. Blue light penetrates deeply and is scattered by the water molecules, while all other colours are absorbed; thus the water appears blue. On the other hand, coastal water often appears greenish. Coastal water contains much more suspended silt and algae and microscopic organisms than the open ocean. Many of these organisms, such as phytoplankton, absorb light in the blue and red range through their photosynthetic pigments, leaving green as the dominant wavelength of reflected light. Therefore the higher the phytoplankton concentration in water, the greener it appears. Small silt particles may also absorb blue light, further shifting the colour of water away from blue when there are high concentrations of suspended particles.[12]

The ocean can be divided into depth layers depending on the amount of light penetration, as discussed in pelagic zone. The upper 200 metres is referred to as the photic or euphotic zone. This represents the region where enough light can penetrate to support photosynthesis, and it corresponds to the epipelagic zone. From 200 to 1000 metres lies the dysphotic zone, or the twilight zone (corresponding with the mesopelagic zone). There is still some light at these depths, but not enough to support photosynthesis. Below 1000 metres is the aphotic (or midnight) zone, where no light penetrates. This region includes the majority of the ocean volume, which exists in complete darkness.[12]

Paleoclimatology

[edit]

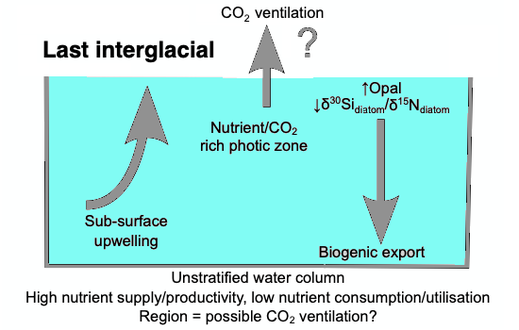

Phytoplankton are unicellular microorganisms which form the base of the ocean food chains. They are dominated by diatoms, which grow silicate shells called frustules. When diatoms die their shells can settle on the seafloor and become microfossils. Over time, these microfossils become buried as opal deposits in the marine sediment. Paleoclimatology is the study of past climates. Proxy data is used in order to relate elements collected in modern-day sedimentary samples to climatic and oceanic conditions in the past. Paleoclimate proxies refer to preserved or fossilized physical markers which serve as substitutes for direct meteorological or ocean measurements.[13] An example of proxies is the use of diatom isotope records of δ13C, δ18O, δ30Si (δ13Cdiatom, δ18Odiatom, and δ30Sidiatom). In 2015, Swann and Snelling used these isotope records to document historic changes in the photic zone conditions of the north-west Pacific Ocean, including nutrient supply and the efficiency of the soft-tissue biological pump, from the modern day back to marine isotope stage 5e, which coincides with the last interglacial period. Peaks in opal productivity in the marine isotope stage are associated with the breakdown of the regional halocline stratification and increased nutrient supply to the photic zone.[14]

The initial development of the halocline and stratified water column has been attributed to the onset of major Northern Hemisphere glaciation at 2.73 Ma, which increased the flux of freshwater to the region, via increased monsoonal rainfall and/or glacial meltwater, and sea surface temperatures.[15][16][17][18] The decrease of abyssal water upwelling associated with this may have contributed to the establishment of globally cooler conditions and the expansion of glaciers across the Northern Hemisphere from 2.73 Ma.[16] While the halocline appears to have prevailed through the late Pliocene and early Quaternary glacial–interglacial cycles,[19] other studies have shown that the stratification boundary may have broken down in the late Quaternary at glacial terminations and during the early part of interglacials.[20][21][22][23][24][14]

Phytoplankton

[edit]

An increase in the amount of phytoplankton also creates an increase in zooplankton, the zooplankton feeds on the phytoplankton as they are at the bottom of the food chain.[25]

Phytoplankton are restricted to the photic zone only, as their growth is completely dependent upon photosynthesis. This results in phytoplankton only occupying the uppermost 50–100 m of the water column. Phytoplankton growth within the photic zone can also be influenced by terrestrial factors, like the weathering of crustal rocks or nutrients from the respiration of plants and animals on land that are carried to the ocean via runoff or riverine input.[25]

Dimethylsulfide loss within the photic zone is controlled by microbial uptake and photochemical degradation.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Photic zone | Marine Life, Photosynthesis & Light | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ Falkowski, Paul G.; Knoll, Andrew H., eds. (2007). Evolution of Primary Producers in the Sea. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-370518-1.X5000-0. ISBN 978-0-12-370518-1.[page needed]

- ^ Photic zone Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 14 August 2009.

- ^ "Trophic Levels of Coral Reefs". Sciencing. 21 May 2018. Retrieved 2019-11-22.

- ^ Göltenboth, Friedhelm; Schoppe, Sabine; Widmann, Peter (2006). "Open Ocean". Ecology of Insular Southeast Asia. pp. 71–84. doi:10.1016/B978-044452739-4/50006-1. ISBN 978-0-444-52739-4.

- ^ Neilson, John D.; Ian Perry, R.; Crawford, Lisa M. (2019). "Fish Migration, Vertical". Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences. pp. 217–223. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-409548-9.10778-X. ISBN 978-0-12-813082-7.

- ^ Sheppard, Charles R. C. (1982). "Photic zone". Beaches and Coastal Geology. Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series. p. 636. doi:10.1007/0-387-30843-1_325. ISBN 978-0-87933-213-6.

- ^ Longhurst, Alan R.; Glen Harrison, W. (June 1988). "Vertical nitrogen flux from the oceanic photic zone by diel migrant zooplankton and nekton". Deep Sea Research Part A. Oceanographic Research Papers. 35 (6): 881–889. Bibcode:1988DSRA...35..881L. doi:10.1016/0198-0149(88)90065-9.

- ^ Gundersen, K.; Mountain, C. W.; Taylor, Diane; Ohye, R.; Shen, J. (July 1972). "Some Chemical and Microbiological Observations in the Pacific Ocean off the Hawaiian Islands". Limnology and Oceanography. 17 (4): 524–532. Bibcode:1972LimOc..17..524G. doi:10.4319/lo.1972.17.4.0524.

- ^ Lee, ZhongPing; Weidemann, Alan; Kindle, John; Arnone, Robert; Carder, Kendall L.; Davis, Curtiss (March 2007). "Euphotic zone depth: Its derivation and implication to ocean-color remote sensing". Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 112 (C3). Bibcode:2007JGRC..112.3009L. doi:10.1029/2006JC003802.

- ^ Ocean Explorer NOAA. Updated: 26 August 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Webb, Paul (2019) Introduction to Oceanography, chapter 6.5 Light, Rebus Community, Roger Williams University, open textbook.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ "What Are "Proxy" Data? | National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) formerly known as National Climatic Data Center (NCDC)". www.ncdc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- ^ a b Swann, G. E. A.; Snelling, A. M. (6 January 2015). "Photic zone changes in the north-west Pacific Ocean from MIS 4–5e". Climate of the Past. 11 (1): 15–25. Bibcode:2015CliPa..11...15S. doi:10.5194/cp-11-15-2015.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 International License.

- ^ Sigman, Daniel M.; Jaccard, Samuel L.; Haug, Gerald H. (March 2004). "Polar ocean stratification in a cold climate". Nature. 428 (6978): 59–63. Bibcode:2004Natur.428...59S. doi:10.1038/nature02357. PMID 14999278.

- ^ a b Haug, Gerald H.; Ganopolski, Andrey; Sigman, Daniel M.; Rosell-Mele, Antoni; Swann, George E. A.; Tiedemann, Ralf; Jaccard, Samuel L.; Bollmann, Jörg; Maslin, Mark A.; Leng, Melanie J.; Eglinton, Geoffrey (February 2005). "North Pacific seasonality and the glaciation of North America 2.7 million years ago". Nature. 433 (7028): 821–825. Bibcode:2005Natur.433..821H. doi:10.1038/nature03332. PMID 15729332.

- ^ Swann, George E. A.; Maslin, Mark A.; Leng, Melanie J.; Sloane, Hilary J.; Haug, Gerald H. (March 2006). "Diatom δ 18 O evidence for the development of the modern halocline system in the subarctic northwest Pacific at the onset of major Northern Hemisphere glaciation". Paleoceanography. 21 (1). doi:10.1029/2005pa001147.

- ^ Nie, Junsheng; King, John; Liu, Zhengyu; Clemens, Steve; Prell, Warren; Fang, Xiaomin (November 2008). "Surface-water freshening: A cause for the onset of North Pacific stratification from 2.75 Ma onward?". Global and Planetary Change. 64 (1–2): 49–52. Bibcode:2008GPC....64...49N. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2008.08.003.

- ^ Swann, George E.A. (August 2010). "Salinity changes in the North West Pacific Ocean during the late Pliocene/early Quaternary from 2.73 Ma to 2.52 Ma". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 297 (1–2): 332–338. Bibcode:2010E&PSL.297..332S. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2010.06.035.

- ^ Sarnthein, M.; Gebhardt, H.; Kiefer, T.; Kucera, M.; Cook, M.; Erlenkeuser, H. (November 2004). "Mid Holocene origin of the sea-surface salinity low in the subarctic North Pacific". Quaternary Science Reviews. 23 (20–22): 2089–2099. Bibcode:2004QSRv...23.2089S. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2004.08.008.

- ^ Jaccard, S.L.; Galbraith, E.D.; Sigman, D.M.; Haug, G.H. (January 2010). "A pervasive link between Antarctic ice core and subarctic Pacific sediment records over the past 800kyrs". Quaternary Science Reviews. 29 (1–2): 206–212. Bibcode:2010QSRv...29..206J. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2009.10.007.

- ^ Galbraith, Eric D.; Kienast, Markus; Jaccard, Samuel L.; Pedersen, Thomas F.; Brunelle, Brigitte G.; Sigman, Daniel M.; Kiefer, Thorsten (June 2008). "Consistent relationship between global climate and surface nitrate utilization in the western subarctic Pacific throughout the last 500 ka". Paleoceanography. 23 (2). Bibcode:2008PalOc..23.2212G. doi:10.1029/2007pa001518.

- ^ Brunelle, Brigitte G.; Sigman, Daniel M.; Jaccard, Samuel L.; Keigwin, Lloyd D.; Plessen, Birgit; Schettler, Georg; Cook, Mea S.; Haug, Gerald H. (September 2010). "Glacial/interglacial changes in nutrient supply and stratification in the western subarctic North Pacific since the penultimate glacial maximum". Quaternary Science Reviews. 29 (19–20): 2579–2590. Bibcode:2010QSRv...29.2579B. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.03.010.

- ^ Kohfeld, Karen E.; Chase, Zanna (November 2011). "Controls on deglacial changes in biogenic fluxes in the North Pacific Ocean". Quaternary Science Reviews. 30 (23–24): 3350–3363. Bibcode:2011QSRv...30.3350K. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2011.08.007.

- ^ a b "Accumulation". www.dnr.louisiana.gov. Retrieved 2023-12-01.