Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Peafowl

View on Wikipedia

| Peafowl Temporal range: Late Pliocene – present

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Indian peacock displaying his train | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Galliformes |

| Family: | Phasianidae |

| Subfamily: | Phasianinae |

| Tribe: | Pavonini |

| Groups included | |

| Cladistically included but traditionally excluded taxa | |

Peafowl is a common name for two bird species of the genus Pavo and one species of the closely related genus Afropavo within the tribe Pavonini of the family Phasianidae (the pheasants and their allies). Male peafowl are referred to as peacocks, and female peafowl are referred to as peahens.[1] Despite this, peacock is usually used to refer to both sexes, in common language.

The two Asiatic species are the blue or Indian peafowl originally from the Indian subcontinent, and the green peafowl from Southeast Asia. The third peafowl species, the Congo peafowl, is native only to the Congo Basin. Male peafowl are known for their piercing calls and their extravagant plumage. The latter is especially prominent in the Asiatic species, which have an eye-spotted "tail" or "train" of covert feathers, which they display as part of a courtship ritual.

The functions of the elaborate iridescent coloration and large "train" of peacocks have been the subject of extensive scientific debate. Charles Darwin suggested that they served to attract females, and the showy features of the males had evolved by sexual selection. More recently, Amotz Zahavi proposed in his handicap principle that these features acted as honest signals of the males' fitness, since less-fit males would be disadvantaged by the difficulty of surviving with such large and conspicuous structures.

Description

[edit]

The Indian peacock (Pavo cristatus) has iridescent blue and green plumage, mostly metal-like blue and green. In both species, females are a little smaller than males in terms of weight and wingspan, but males are significantly longer due to the "tail", also known as a "train".[2] The peacock train consists not of tail quill feathers but highly elongated upper tail coverts. These feathers are marked with eyespots, best seen when a peacock fans his tail. All species have a crest atop the head. The Indian peahen has a mixture of dull grey, brown, and green in her plumage. The female also displays her plumage to ward off female competition or signal danger to her young.

Male green peafowls (Pavo muticus) have green and bronze or gold plumage, and black wings with a sheen of blue. Unlike Indian peafowl, the green peahen is similar to the male, but has shorter upper tail coverts, a more coppery neck, and overall less iridescence. Both males and females have spurs.[3][page needed]

The Congo peacock (Afropavo congensis) male does not display his covert feathers, but uses his actual tail feathers during courtship displays. These feathers are much shorter than those of the Indian and green species, and the ocelli are much less pronounced. Females of the Indian and African species are dull grey and/or brown.

Chicks of both sexes in all the species are cryptically colored. They vary between yellow and tawny, usually with patches of darker brown or light tan and "dirty white" ivory.

Mature peahens have been recorded as suddenly growing typically male peacock plumage and making male calls.[4] Research has suggested that changes in mature birds are due to a lack of estrogen from old or damaged ovaries, and that male plumage and calls are the default unless hormonally suppressed.[5]

Iridescence and structural coloration

[edit]As with many birds, vibrant iridescent plumage colors are not primarily pigments, but structural coloration. Optical interference of Bragg reflections, from regular, periodic nanostructures of the barbules (fiber-like components) of the feathers, produce the peacock's colors.[6] Slight changes to the spacing of the barbules result in different colors. Brown feathers are a mixture of red and blue: one color is created by the periodic structure and the other is created by a Fabry–Pérot interference peak from reflections from the outer and inner boundaries. Color derived from physical structure rather than pigment can vary with viewing angle, causing iridescence.[7]

Courtship

[edit]Most commonly, during a courtship display, the visiting peahen will stop directly in front of the peacock, thus providing her with the ability to assess the male at 90° to the surface of the feather. Then, the male will turn and display his feathers about 45° to the right of the sun's azimuth which allows the sunlight to accentuate the iridescence of his train. If the female chooses to interact with the male, he will then turn to face her and shiver his train so as to begin the mating process.[8]

Evolution

[edit]Sexual selection

[edit]Charles Darwin suggested in The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex that peafowl plumage may have evolved through sexual selection:

Many female progenitors of the peacock must, during a long line of descent, have appreciated this superiority; for they have unconsciously, by the continued preference for the most beautiful males, rendered the peacock the most splendid of living birds.

Aposematism and natural selection

[edit]It has been suggested that a peacock's train, loud call, and fearless behavior have been formed by natural selection (with or without sexual selection too), and served as an aposematic display to intimidate predators and rivals.[9][10] This hypothesis is designed to explain Takahashi's observations that in Japan, neither reproductive success nor physical condition correlate with the train's length, symmetry or number of eyespots.[11]

Female choice

[edit]

Multiple hypotheses involving female choice have been posited. One hypothesis is that females choose mates with good genes. Males with more exaggerated secondary sexual characteristics, such as bigger, brighter peacock trains, tend to have better genes[example needed] in the peahen's eyes.[12] These better genes directly benefit her offspring, as well as her fitness and reproductive success.

Runaway selection is another hypothesis. In runaway sexual selection, linked genes in males and females code for sexually dimorphic traits in males, and preference for those traits in females.[13] The close spatial association of alleles[which?] for loci[which?] involved in the train in males, and for preference for more exuberant trains in females, on the chromosome (linkage disequilibrium) causes a positive feedback loop that exaggerates both the male traits and the female preferences.

Another hypothesis is sensory bias, in which females have a preference for a trait in a non-mating context that becomes transferred to mating, such as Merle Jacobs' food-courtship hypothesis, which suggests that peahens are attracted to peacocks for the resemblance of their eye spots to blue berries.[14]

Multiple causalities for the evolution of female choice are also possible.

The peacock's train and iridescent plumage are perhaps the best-known examples of traits believed to have arisen through sexual selection, though with some controversy.[15] Male peafowl erect their trains to form a shimmering fan in their display for females. Marion Petrie tested whether or not these displays signalled a male's genetic quality by studying a feral population of peafowl in Whipsnade Wildlife Park in southern England. The number of eyespots in the train predicted a male's mating success. She was able to manipulate this success by cutting the eyespots off some of the males' tails:[16] females lost interest in pruned males and retained interest in untrimmed ones. Males with fewer eyespots, thus having lower mating success, suffered from greater predation.[17] She allowed females to mate with males with differing numbers of eyespots, and reared the offspring in a communal incubator to control for differences in maternal care. Chicks fathered by more ornamented males weighed more than those fathered by less ornamented males, an attribute generally associated with better survival rate in birds. These chicks were released into the park and recaptured one year later. Those with heavily ornamented feathers were better able to avoid predators and survive in natural conditions.[18] Thus, Petrie's work shows correlations between tail ornamentation, mating success, and increased survival ability in both the ornamented males and their offspring.

Furthermore, peafowl and their sexual characteristics have been used in the discussion of the causes for sexual traits. Amotz Zahavi used the excessive tail plumes of male peafowls as evidence for his "handicap principle".[19] Since these trains are likely to be deleterious to an individual's survival (as their brilliance makes them more visible to predators and their length hinders escape from danger), Zahavi argued that only the fittest males could survive the handicap of a large train. Thus, a brilliant train serves as an honest indicator for females that these highly ornamented males are good at surviving for other reasons, so are preferable mates.[20] This theory may be contrasted with Ronald Fisher's hypothesis that male sexual traits are the result of initially arbitrary aesthetic selection by females.

In contrast to Petrie's findings, a seven-year Japanese study of free-ranging peafowl concluded that female peafowl do not select mates solely on the basis of their trains. Mariko Takahashi found no evidence that peahens preferred peacocks with more elaborate trains (such as with more eyespots), a more symmetrical arrangement, or a greater length.[11] Takahashi determined that the peacock's train was not the universal target of female mate choice, showed little variance across male populations, and did not correlate with male physiological condition. Adeline Loyau and her colleagues responded that alternative and possibly central explanations for these results had been overlooked.[21] They concluded that female choice might indeed vary in different ecological conditions.

Plumage colours as attractants

[edit]

A peacock's copulation success rate depends on the colours of his eyespots (ocelli) and the angle at which they are displayed. The angle at which the ocelli are displayed during courtship is more important in a peahen's choice of males than train size or number of ocelli.[22] Peahens pay careful attention to the different parts of a peacock's train during his display. The lower train is usually evaluated during close-up courtship, while the upper train is more of a long-distance attraction signal. Actions such as train rattling and wing shaking also kept the peahens' attention.[23]

Redundant signal hypothesis

[edit]Although an intricate display catches a peahen's attention, the redundant signal hypothesis also plays a crucial role in keeping this attention on the peacock's display. The redundant signal hypothesis explains that whilst each signal that a male projects is about the same quality, the addition of multiple signals enhances the reliability of that mate. This idea also suggests that the success of multiple signalling is not only due to the repetitiveness of the signal, but also of multiple receivers of the signal. In the peacock species, males congregate a communal display during breeding season and the peahens observe. Peacocks first defend their territory through intra-sexual behaviour, defending their areas from intruders. They fight for areas within the congregation to display a strong front for the peahens. Central positions are usually taken by older, dominant males, which influences mating success. Certain morphological and behavioural traits come in to play during inter and intra-sexual selection, which include train length for territory acquisition and visual and vocal displays involved in mate choice by peahens.[24]

Behaviour

[edit]

Peafowl are forest birds that nest on the ground, but roost in trees. They are terrestrial feeders. All species of peafowl are believed to be polygamous. In common with other members of the Galliformes, the males possess metatarsal spurs or "thorns" on their legs used during intraspecific territorial fights with some other members of their kind.

In courtship, vocalisation stands to be a primary way for peacocks to attract peahens. Some studies suggest that the intricacy of the "song" produced by displaying peacocks proved to be impressive to peafowl. Singing in peacocks usually occurs just before, just after, or sometimes during copulation.[25]

Diet

[edit]

Peafowl are omnivores and mostly eat plants, flower petals, seed heads, insects and other arthropods, reptiles, and amphibians. Wild peafowl look for their food scratching around in leaf litter either early in the morning or at dusk. They retreat to the shade and security of the woods for the hottest portion of the day. These birds are not picky and will eat almost anything they can fit in their beak and digest. They actively hunt insects like ants, crickets and termites; millipedes; and other arthropods and small mammals.[26] Indian peafowl also eat small snakes.[27]

Domesticated peafowl may also eat bread and cracked grain such as oats and corn, cheese, cooked rice and sometimes cat food. It has been noticed by keepers that peafowl enjoy protein-rich food including larvae that infest granaries, different kinds of meat and fruit, as well as vegetables including dark leafy greens, broccoli, carrots, beans, beets, and peas.[28]

Cultural significance

[edit]Indian peafowl

[edit]

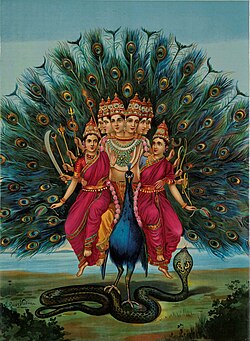

The peafowl is native to India[29] and significant in its culture.[30] In Hinduism, the Indian peacock is the mount of the god of war, Kartikeya, and the warrior goddess Kaumari, and is also depicted around the goddess Santoshi.[31] During a war with Asuras, Kartikeya split the demon king Surapadman in half. Out of respect for his adversary's prowess in battle, the god converted the two halves into an integral part of himself. One half became a peacock serving as his mount, and the other a rooster adorning his flag. The peacock displays the divine shape of Omkara when it spreads its magnificent plumes into a full-blown circular form.[32] In the Tantric traditions of Hinduism the goddess Tvarita is depicted with peacock feathers.[33] A peacock feather also adorns the crest of the god Krishna.[34]

Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of the Mauryan Empire, was born an orphan and raised by a family farming peacocks. According to the Buddhist tradition[which?], the ancestors of the Maurya kings had settled in a region where peacocks (mora in Pali) were abundant. Therefore, they came to be known as "Moriyas", literally, "belonging to the place of peacocks". According to another Buddhist account, these ancestors built a city called Moriya-nagara ("Moriya-city"), which was so called, because it was built with the "bricks coloured like peacocks' necks".[35] After conquering the Nanda Empire and defeating the Seleucid Empire, the Chandragupta dynasty reigned uncontested during its time. Its royal emblem remained the peacock until Emperor Ashoka changed it to a lion, as seen in the Lion Capital of Ashoka, as well in his edicts. The peacock continued to represent elegance and royalty in India during medieval times; for instance, the Mughal seat of power was called the Peacock Throne.

The peacock is represented in both the Burmese and Sinhalese zodiacs. To the Sinhalese people, the peacock is the third animal of the zodiac of Sri Lanka.[36]

Peacocks (often a symbol of pride and vanity) were believed[by whom?] to deliberately consume poisonous substances in order to become immune to them, as well as to make the colours of their resplendent plumage all the more vibrant – seeing as so many poisonous flora and fauna are so colourful due to aposematism, this idea appears to have merit. The Buddhist deity Mahamayuri is depicted seated on a peacock. Peacocks are seen supporting the throne of Amitabha, the ruby red sunset coloured archetypal Buddha of Infinite Light.

India adopted the peacock as its national bird in 1963 and it is one of the national symbols of India.[37]

Middle East

[edit]Yazidism

[edit]Tawûsî Melek (lit. 'Peacock Angel')[38][39][40][41] one of the central figures of the Yazidi religion, is symbolized with a peacock.[42][38] In Yazidi creation stories, before the creation of this world, God created seven Divine Beings, of whom Tawûsî Melek was appointed as the leader. God assigned all of the world's affairs to these seven Divine Beings, also often referred to as the Seven Angels or heft sirr ("the Seven Mysteries").[42][43][44][45]

In Yazidism, the peacock is believed to represent the diversity of the world,[46] and the colourfulness of the peacock's feathers is considered to represent of all the colours of nature. The feathers of the peacock also symbolize sun rays, from which come light, luminosity and brightness. The peacock opening the feathers of its tail in a circular shape symbolizes the sunrise.[47]

Consequently, due to its holiness, Yazidis are not allowed to hunt and eat the peacock, ill-treat it or utter bad words about it. Images of the peacock are also found drawn around the sanctuary of Lalish and on other Yazidi shrines and holy sites, homes, as well as religious, social, cultural and academic centres.[47]

Mandaeism

[edit]In The Baptism of Hibil Ziwa, the Mandaean uthra and emanation Yushamin is described as a peacock.[48]

Ancient Greece

[edit]

Ancient Greeks believed that the flesh of peafowl did not decay after death,[citation needed] so it became a symbol of immortality. In Hellenistic imagery, the Greek goddess Hera's chariot was pulled by peacocks, birds not known to Greeks before the conquests of Alexander. Alexander's tutor, Aristotle, refers to it as "the Persian bird". When Alexander saw the birds in India, he was so amazed at their beauty that he threatened the severest penalties for any man who slew one.[49] Claudius Aelianus writes that there were peacocks in India, larger than anywhere else.[50]

One myth states that Hera's servant, the hundred-eyed Argus Panoptes, was instructed to guard the woman-turned-cow, Io. Hera had transformed Io into a cow after learning of Zeus's interest in her. Zeus had the messenger of the gods, Hermes, kill Argus through eternal sleep and free Io. According to Ovid, to commemorate her faithful watchman, Hera had the hundred eyes of Argus preserved forever, in the peacock's tail.[51]

Christianity

[edit]The symbolism was adopted by early Christianity, thus many early Christian paintings and mosaics show the peacock.[52] The peacock is still used in the Easter season, especially in the east. The "eyes" in the peacock's tail feathers can symbolise the all-seeing Christian God,[53] the Church,[54] or angelic wisdom.[55] The emblem of a pair of peacocks drinking from a vase is used as a symbol of the eucharist and the resurrection, as it represents the Christian believer drinking from the waters of eternal life.[56] The peacock can also symbolise the cosmos if one interprets its tail with its many "eyes" as the vault of heaven dotted by the sun, moon, and stars.[57] Due to the adoption by Augustine of the ancient idea that the peacock's flesh did not decay, the bird was again associated with immortality.[54][56] In Christian iconography, two peacocks are often depicted either side of the Tree of Life.[58]

The symbolic association of peacock feathers with the wings of angels led to the belief that the waving of such liturgical fans resulted in an automated emission of prayers. This affinity between peacocks' and angels' feathers was also expressed in other artistic media, including paintings of angels with peacock feather wings [59]

Judaism

[edit]Among Ashkenazi Jews, the golden peacock is a symbol for joy and creativity, with quills from the bird's feathers being a metaphor for a writer's inspiration.[60]

Renaissance

[edit]The peacock motif was revived in the Renaissance iconography that unified Hera and Juno, and on which European painters focused.[61]

Contemporary

[edit]In 1956, John J. Graham created an abstraction of an 11-feathered peacock logo for American broadcaster NBC. This brightly hued peacock was adopted due to the increase in colour programming. NBC's first colour broadcasts showed only a still frame of the colourful peacock. The emblem made its first on-air appearance on 22 May 1956.[62] The current, six-feathered logo debuted on 12 May 1986.

Peacocks are a popular ornamental animal due to their beauty.[63]

-

Stone from Mingachevir Church Complex (4th-7th century AD)

-

Roundel with dragon design. China, Qing-dynasty, late 17th century. Peacock feather barbules are used to highlight the dragon's scales.

-

Peacock by Merab Abramishvili (1957–2006)

-

Annunciation with St. Emidius (1486) by Carlo Crivelli. A peacock is sitting on the roof above the praying Virgin Mary.

-

Painting by Abbott Thayer and Richard Meryman for Thayer's 1909 book, wrongly suggesting that the peacock's plumage was camouflage

-

Common peafowl, by John Gould, c. 1880. Brooklyn Museum.

-

Syrian bowl with peacock motif, c. 1200. Brooklyn Museum.

-

Peacock sculpture at Golingeshwara temple complex in Biccavolu, India

Breeding and colour variations

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2023) |

Hybrids between Indian peafowl and Green peafowl are called Spaldings, after the first person to successfully hybridise them, Keith Spalding.[citation needed] Spaldings with a high-green phenotype do much better in cold temperatures than the cold-intolerant green peafowl while still looking like their green parents. Plumage varies between individual spaldings, with some looking far more like green peafowl and some looking far more like blue peafowl, though most visually carry traits of both.

In addition to the wild-type "blue" colouration, several hundred variations in colour and pattern are recognised as separate morphs of the Indian Blue among peafowl breeders. Pattern variations include solid-wing/black shoulder (the black and brown stripes on the wing are instead one solid colour), pied, white-eye (the ocelli in a male's eye feathers have white spots instead of black), and silver pied (a mostly white bird with small patches of colour). Colour variations include white, purple, Buford bronze, opal, midnight, charcoal, jade, and taupe, as well as the sex-linked colours purple, cameo, peach, and Sonja's Violeta. Additional colour and pattern variations are first approved by the United Peafowl Association to become officially recognised as a morph among breeders. Alternately-coloured peafowl are born differently coloured than wild-type peafowl, and though each colour is recognisable at hatch, their peachick plumage does not necessarily match their adult plumage.

Occasionally, peafowl appear with white plumage. Although albino peafowl do exist,[citation needed] this is quite rare, and almost all white peafowl are not albinos; they have a genetic condition called leucism, which causes pigment cells to fail to migrate from the neural crest during development. Leucistic peafowl can produce pigment but not deposit the pigment to their feathers, resulting in a blue-grey eye colour and the complete lack of colouration in their plumage. Pied peafowl are affected by partial leucism, where only some pigment cells fail to migrate, resulting in birds that have colour but also have patches absent of all colour; they, too, have blue-grey eyes. By contrast, true albino peafowl would have a complete lack of melanin, resulting in irises that look red or pink. Leucistic peachicks are born yellow and become fully white as they mature.

The black-shouldered or Japanned mutation was initially considered as a subspecies of the Indian peafowl (P. c. nigripennis) (or even a separate species (P. nigripennis))[64] and was a topic of some interest during Darwin's time. Others had doubts about its taxonomic status, but the English naturalist and biologist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) presented firm evidence for it being a variety under domestication, which treatment is now well established and accepted. It being a colour variation rather than a wild species was important for Darwin to prove, as otherwise it could undermine his theory of slow modification by natural selection in the wild.[65] It is, however, only a case of genetic variation within the population. In this mutation, the adult male is melanistic with black wings.

Gastronomy

[edit]

In ancient Rome, peafowl were served as a delicacy.[66] The dish was introduced there in approximately 35 B.C. The poet Horace ridiculed the eating of peafowl, saying they tasted like chicken. Peafowl eggs were also valued. Gaius Petronius in his Satyricon also mocked the ostentation and snobbery of eating peafowl and their eggs.

During the Medieval period, various types of fowl were consumed as food, with the poorer populations (such as serfs) consuming more common birds, such as chicken. However, the more wealthy gentry were privileged to eat less usual foods, such as swan, and even peafowl were consumed. On a king's table, a peacock would be for ostentatious display as much as for culinary consumption.[67]

From the 1864 The English and Australian Cookery Book, regarding occasions and preparation of the bird:

Instead of plucking this bird, take off the skin with the greatest care, so that the feathers do not get detached or broken. Stuff it with what you like, as truffles, mushrooms, livers of fowls, bacon, salt, spice, thyme, crumbs of bread, and a bay-leaf. Wrap the claws and head in several folds of cloth, and envelope the body in buttered paper. The head and claws, which project at the two ends, must be basted with water during the cooking, to preserve them, and especially the tuft. Before taking it off the spit, brown the bird by removing the paper. Garnish with lemon and flowers. If to come on the table cold, place the bird in a wooden trencher, in the middle of which is fixed a wooden skewer, which should penetrate the body of the bird, to keep it upright. Arrange the claws and feathers in a natural manner, and the tail like a fan, supported with wire. No ordinary cook can place a peacock on the table properly. This ceremony was reserved, in the times of chivalry, for the lady most distinguished for her beauty. She carried it, amidst inspiring music, and placed it, at the commencement of the banquet, before the master of the house. At a nuptial feast, the peacock was served by the maid of honour, and placed before the bride for her to consume.[68]

References

[edit]- ^ "Peacock | Facts & Habitat | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2 October 2025. Retrieved 17 October 2025.

- ^ "Peafowl". San Diego Zoo Animals & Plants. San Diego Zoo. 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2021. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ Darwin, Charles (1871). The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. Archived from the original on 29 April 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2023 – via Gutenberg.org.

- ^ Morgan, T. H. (July 1942). "Sex inversion in the peafowl". Journal of Heredity. 33 (7): 247–248. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a105182.

- ^ Inglis-Arkell, Esther (7 May 2013). "The long-running mystery of why birds seemingly change sex". io9. Archived from the original on 19 July 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ Zi, Jian; Yu, Xindi; Li, Yizhou; Hu, Xinhua; Xu, Chun; Wang, Xingjun; Liu, Xiaohan; Fu, Rongtang (28 October 2003). "Coloration strategies in peacock feathers". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (22): 12576–12578. Bibcode:2003PNAS..10012576Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.2133313100. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 240659. PMID 14557541.

- ^ Blau, Steven K. (January 2004). "Light as a Feather: Structural Elements Give Peacock Plumes Their Color". Physics Today. 57 (1): 18–20. Bibcode:2004PhT....57a..18B. doi:10.1063/1.1650059.

- ^ Adeline Loyau, Doris Gomez, Benoît Moureau, Marc Théry, Nathan S. Hart, Michel Saint Jalme, Andrew T.D. Bennett, Gabriele Sorci (November 2007). "Iridescent structurally based coloration of eyespots correlates with mating success in the peacock". Behavioral Ecology. 18 (6): 1123–1131. doi:10.1093/beheco/arm088.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jordania, Joseph (September 2021). "Can there be an Alternative Evolutionary Reason Behind the Peacock's Impressive Train?". Academia Letters. doi:10.20935/AL3534. S2CID 244187388. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ Jordania, Joseph (2011). "Peacock's Tail: Tale of Beauty and Intimidation". Why do People Sing? Music in Human Evolution. Tbilisi, Georgia: Logos. pp. 192–196. ISBN 978-9941-401-86-2.

- ^ a b Takahashi, Mariko; Arita, Hiroyuki; Hiraiwa-Hasegawa, Mariko; Hasegawa, Toshikazu (April 2008). "Peahens do not prefer peacocks with more elaborate trains". Animal Behaviour. 75 (4): 1209–1219. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2007.10.004. S2CID 53196851.

- ^ Manning, J. T. (September 1989). "Age-advertisement and the evolution of the peacock's train". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2 (5): 379–384. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.1989.2050379.x. S2CID 86740688.

- ^ Caldwell, Roy, and Jennifer Collins. "When Sexual Selection Runs Away Archived 29 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine." Evolution 101: Runaway Selection. N.p., n.d. 24 November 2014.

- ^ Jacobs, Merle. "A New Look at Darwinian Sexual Selection". NaturalSCIENCE. Heron Publishing. Archived from the original on 8 September 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ Male Peacock's Feather Fails to Impress Females: Study Archived 27 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine. The Indian News. 27 March 2008.

- ^ Petrie, Marion; Halliday, T.; Sanders, C. (1991). "Peahens prefer peacocks with elaborate trains". Animal Behaviour. 41 (2): 323–331. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80484-1. S2CID 53201236.

- ^ Petrie, M. (1992). "Peacocks with low mating success are more likely to suffer predation". Animal Behaviour. 44: 585–586. doi:10.1016/0003-3472(92)90072-H. S2CID 53167596.

- ^ Zuk, Marlene. (2002). Sexual Selections: What we can and can't learn about sex from animals. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA. ISBN 0520240758

- ^ Zahavi, Amotz (1975). "Mate selection—A selection for a handicap" (PDF). Journal of Theoretical Biology. 53 (1): 205–214. Bibcode:1975JThBi..53..205Z. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.586.3819. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(75)90111-3. PMID 1195756. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ Loyau, Adeline; Saint Jalme, Michel; Cagniant, Cécile; Sorci, Gabriele (October 2005). "Multiple sexual advertisements honestly reflect health status in peacocks (Pavo cristatus)". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 58 (6): 552–557. doi:10.1007/s00265-005-0958-y. S2CID 27621492.

- ^ Loyau, Adeline; Petrie, Marion; Saint Jalme, Michel; Sorci, Gabriele (November 2008). "Do peahens not prefer peacocks with more elaborate trains?". Animal Behaviour. 76 (5): e5 – e9. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.07.021. S2CID 40638610.

- ^ Dakin, Roslyn; Montgomerie, Robert (June 2013). "Eye for an eyespot: how iridescent plumage ocelli influence peacock mating success". Behavioral Ecology. 24 (5): 1048–1057. doi:10.1093/beheco/art045.

- ^ Yorzinski, Jessica L.; Patricelli, Gail L.; Babcock, Jason S.; Pearson, John M.; Platt, Michael L. (15 August 2013). "Through their eyes: selective attention in peahens during courtship". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 216 (16): 3035–3046. Bibcode:2013JExpB.216.3035Y. doi:10.1242/jeb.087338. PMC 4232502. PMID 23885088.

- ^ Loyau, Adeline; Jalme, Michel Saint; Sorci, Gabriele (September 2005). "Intra- and Intersexual Selection for Multiple Traits in the Peacock (Pavo cristatus)". Ethology. 111 (9): 810–820. Bibcode:2005Ethol.111..810L. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2005.01091.x.

- ^ Anoop, K. R.; Yorzinski, Jessica L. (1 January 2013). "Peacock copulation calls attract distant females". Behaviour. 150 (1): 61–74. doi:10.1163/1568539X-00003037. S2CID 86482247.

- ^ "Peacock". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2 March 2010.

- ^ Johnsingh, A. J. T. (1976). "Peacocks and cobra". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 73 (1): 214.

- ^ "What Is a Peacock's Diet?". pawnation.com. Archived from the original on 11 May 2014.

- ^ "Indian Peafowl". San Francisco Zoo & Gardens. 16 October 2021. Archived from the original on 20 September 2024. Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- ^ "Why Are There So Many Peacocks in India's Arts, Culture, and Legends?". Fodors Travel Guide. 20 October 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- ^ Clothey, Fred W. Many Faces of Murakan: The History and Meaning of a South Indian God. Walter De Gruyter Inc., 1978. ISBN 978-9027976321.

- ^ Ayyar, SRS. "Muruga – The Ever-Merciful Lord". Murugan Bhakti: The Skanda Kumāra site. Archived from the original on 9 February 2014. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ Slouber, Michael. 2017. Early Tantric Medicine: Snakebite, Mantras, and Healing in the Garuda Tantras. Page 99. Oxford University Press.

- ^ "Why does Lord Krishna wear a peacock feather on his head?". The Times of India. 1 March 2024. Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- ^ R. K. Mookerji 1966, p. 14.

- ^ Upham, Edward (20 June 2018). "The history and doctrine of Budhism, popularly illustrated". Ackermann – via Google Books.

- ^ "Indian Peacock: A Symbol of Grace, Joy, Beauty and Love". Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Sembolîzma teyran di Êzîdîtiyê de (1)" (in Kurdish). Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ Omarkhali, Khanna (2017). The Yezidi Religious Textual Tradition : From Oral to Written Categories, Transmission, Scripturalisation and Canonisation of the Yezidi Oral Religious Texts. Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-10856-0. OCLC 1329211153.

- ^ Aysif, Rezan Shivan (2021). The Role of Nature in Yezidism: Poetic Texts and Living Tradition. Göttingen: Göttingen University Press. doi:10.17875/gup2021-1855. ISBN 978-3-86395-514-4. S2CID 246596953.

- ^ "مەھدى حەسەن:جەژنا سەر سالێ دمیتۆلۆژیا ئێزدیان دا". 13 April 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ a b Asatrian, Garnik S.; Arakelova, Victoria (January 2003). Asatrian, Garnik S. (ed.). "Malak-Tāwūs: The Peacock Angel of the Yezidis". Iran and the Caucasus. 7 (1–2). Leiden: Brill Publishers in collaboration with the Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies (Yerevan): 1–36. doi:10.1163/157338403X00015. eISSN 1573-384X. ISSN 1609-8498. JSTOR 4030968. LCCN 2001227055. OCLC 233145721.

- ^ Allison, Christine (25 January 2017). "The Yazidis". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.254. ISBN 9780199340378. Archived from the original on 11 March 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ Asatrian, Garnik S.; Arakelova, Victoria (2014). "Part I: The One God - Malak-Tāwūs: The Leader of the Triad". The Religion of the Peacock Angel: The Yezidis and Their Spirit World. Gnostica. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. pp. 1–28. doi:10.4324/9781315728896. ISBN 978-1-84465-761-2. OCLC 931029996.

- ^ Omarkhali, Khanna (2017). The Yezidi religious textual tradition : from oral to written categories, transmission, scripturalisation and canonisation of the Yezidi oral religious texts. Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 26. ISBN 978-3-447-10856-0. OCLC 1007841078.

- ^ Pirbari, Dimitri; Grigoriev, Stanislav (25 January 2013). Holy Lalish, 2008 (Ezidian temple Lalish in Iraqi Kurdistan). p. 183. Archived from the original on 9 January 2022. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ a b Aysif, Rezan Shivan (2021). The Role of Nature in Yezidism. pp. 61–67, 207–208, 264–265. doi:10.17875/gup2021-1855. ISBN 978-3-86395-514-4. S2CID 246596953. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ Drower, Ethel S. (1953). The Haran Gawaita and The Baptism of Hibil-Ziwa: The Mandaic text reproduced together with translation, notes and commentary. Vatican City: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. p. 52.

- ^ "Aelian, De Natura Animalium, book 5, chapter 21". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Archived from the original on 4 June 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ "Aelian, De Natura Animalium, book 16, chapter 2". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Ovid I, 625. The peacock is an Eastern bird, unknown to Greeks before the time of Alexander.

- ^ Murray, Peter; Murray, Linda (2004). "Birds, symbolic". Oxford Dictionary of Christian Art. Oxford University Press. p. 61. ISBN 0-19-860966-3.

- ^ Keating, Jessica (November 2021). "Hidden in plain sight: on copiousness in the Kunstkammer of Emperor Rudolf II". Journal of the History of Collections. 33 (3): 448. doi:10.1093/jhc/fhab009.

- ^ a b Mercatante, Anthony S. (1988). The Facts on File Encyclopedia of World Mythology and Legend. Facts on File. p. 518. ISBN 0-8160-1049-8.

- ^ Mathews, Thomas (2022). "The iconography of the visions of Isaiah and Ezekiel". In Alpi, F.; Meyer, R.; Tinti, I.; Zakarian, D. (eds.). Armenia Through the Lens of Time. Brill. p. 28. doi:10.1163/9789004527607_003. ISBN 978-90-04-52760-7.

- ^ a b Migotti, Branka (1997). "An early Christian fresco from Štrbinci near Đakovo". Hortus Artium Medievalium. 3: 215–216. doi:10.1484/J.HAM.2.305110.

- ^ Miller, Patricia Cox (2018). In the Eye of the Animal: Zoological Imagination in Ancient Christianity. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-8122-5035-0.

- ^ Hall, James (1994). Hall's Illustrated Dictionary of Symbols in Eastern and Western Art. John Murray. p. 38. ISBN 0-7195-4954-X.

- ^ Green, N. (2006). Ostrich Eggs and Peacock Feathers: Sacred Objects as Cultural Exchange between Christianity and Islam. Al-Masāq, 18(1), 27–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503110500222328

- ^ "The Golden Peacock". Jewish Folk Songs. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- ^ Seznec, Jean (1953) The Survival of the Pagan Gods: Mythological Tradition in Renaissance Humanism and Art

- ^ Brown, Les (1977). The New York Times Encyclopedia of Television. Times Books. p. 328. ISBN 978-0-8129-0721-6.

- ^ "They might look pretty, but do peacocks make good pets?". ABC News. 27 June 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2025.

- ^ Sclater PL (1860). "On the black-shouldered peafowl of Latham (Pavo nigripennis)". Proc. Zool. Soc. London: 221–222.

- ^ van Grouw, H. & Dekkers, W. 2023. The taxonomic history of Black-shouldered Peafowl; with Darwin’s help downgraded from species to variation. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club, 143(1): 111–121. https://doi.org/10.25226/bboc.v143i1.2023.a7

- ^ Gillis, Francesca (4 May 2020). "Ancient Foodies: Modern Misconceptions, Alternative Uses, and Recipes for Food in Ancient Rome". Classics Honors Projects. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ "Fowl Recipes". Medieval-Recipes.com. 2010. Archived from the original on 13 December 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- ^ Abbott, Edward (1864). The English and Australian Cookery Book.

Further reading

[edit]- R. K. Mookerji (1966). Chandragupta Maurya and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0405-0.