Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Wisdom King

View on Wikipedia

A wisdom king (Sanskrit: विद्याराज; IAST: vidyārāja, Chinese: 明王; pinyin: Míngwáng; Japanese pronunciation: Myōō) is a type of wrathful deity in East Asian Buddhism.

Whereas the Sanskrit name is translated literally as "wisdom / knowledge king(s)," the term vidyā in Vajrayana Buddhism is also specifically used to denote mantras;[1] the term may thus also be rendered "mantra king(s)."[2][3] Vidyā is translated in Chinese with the character 明 (lit. "bright, radiant", figuratively "knowledge(able), wisdom, wise"), leading to a wide array of alternative translations such as "bright king(s)" or "radiant king(s)". A similar category of fierce deities known as herukas are found in Tibetan Buddhism.

The female counterparts of wisdom kings are known as wisdom queens (Sanskrit (IAST): vidyārājñī, Chinese and Japanese: 明妃; pinyin: Míngfēi; rōmaji: Myōhi).

Overview

[edit]Development

[edit]Vidyārājas, as their name suggests, are originally conceived of as the guardians and personifications of esoteric wisdom (vidyā), namely mantras and dharanis. They were seen as embodying the mystic power contained in these sacred utterances.[2][4]

During the early stages of esoteric (Vajrayana) Buddhism, many of the deities that would become known as vidyārājas (a term that only came into use around the late 7th-early 8th century[5]) were mainly seen as attendants of bodhisattvas who were invoked for specific ends such as the removal of misfortune and obstacles to enlightenment. They personified certain attributes of these bodhisattvas such as their wisdom or the power of their voices and were held to perform various tasks such as gathering together sentient beings to whom the bodhisattva preaches, subjugating unruly elements, or protecting adherents of Buddhism.[6] Eventually, these divinities became objects of veneration in their own right; no longer necessarily paired with a bodhisattva, they became considered as the manifestations of the bodhisattvas themselves and/or of buddhas, who are believed to assume terrifying forms as a means to save sentient beings out of compassion for them.[7] A belief prevalent in the Japanese tradition known as the sanrinjin (三輪身, "bodies of the three wheels") theory for instance posits that five Wisdom Kings are the fierce incarnations (教令輪身, kyōryōrin-shin, lit. "embodiments of the wheel of injunction") of the Five Wisdom Buddhas, who appear both as gentle bodhisattvas who teach the Dharma through compassion and as terrifying vidyārājas who teach through fear, shocking nonbelievers into faith.[8][9][10][11]

The evolution of the vidyārāja will be illustrated here by the deity Yamāntaka, one of the earliest Buddhist wrathful deities. In the 6th century text Mañjuśrī-mūla-kalpa, Yamāntaka is portrayed as the oath-bound servant of the bodhisattva Mañjuśrī who assembles all beings from across the world to hear the Buddha's preaching and vanquishes (and converts) those who are hostile to Buddhism; at the same time, Yamāntaka is also the personification of Mañjuśrī's dharani, the benefits of which are identical to his abilities.[12] He was also commonly depicted in statuary along with Mañjuśrī as a diminutive yaksha-like attendant figure.[13]

Later, as Yamāntaka and similar subordinates of various bodhisattvas (e.g. Hayagrīva, who was associated with Avalokiteśvara) became fully independent deities, they began to be portrayed by themselves and increasingly acquired iconographic attributes specific to each. Yamāntaka, for instance, is commonly shown with six heads, arms, and legs and riding or standing on a buffalo mount.[14] The status and function of these deities have shifted from being minor emissaries who gather together and intimidate recalcitrant beings to being intimately involved in the primary task of esoteric Buddhism: the transformation of passions and ignorance (avidyā) into compassion and wisdom.[15] As a result of this development, the relationship between Mañjuśrī and Yamāntaka was recontextualized such that Yamāntaka is now considered to be the incarnation of Mañjuśrī himself (so the Mañjuśrī-nāma-samgīti).[14] Eventually, in the sanrinjin interpretation of Japanese esoteric Buddhism, both Yamāntaka and Mañjuśrī - under the name Vajratīkṣṇa (金剛利菩薩, Kongōri Bosatsu)[16][17] - became classified as avatars of the buddha Amitābha.[18][19]

Other Wisdom Kings followed a more or less similar development. Hayagrīva, for example, was originally the horse-headed incarnation of the Hindu god Vishnu which was adopted into Buddhism as Avalokiteśvara's attendant (although unlike the Hindu Hayagrīva, the Buddhist figure was never portrayed with a horse's head, instead being depicted like Yamāntaka as a yaksha who may have a miniature horse head emerging from his hair).[20] Eventually, as Hayagrīva increasingly rose to prominence, the distinction between him and his superior became increasingly blurred so that he ultimately turned into one of Avalokiteśvara's many guises in both China and Japan.[21] One of the more famous vidyārājas, Acala (Acalanātha), was originally an acolyte or messenger of the buddha Vairocana before he was interpreted as Vairocana's fierce aspect or kyōryōrin-shin in the Japanese tradition.[22] (In Nepal and Tibet, meanwhile, he is instead identified as the incarnation of either Mañjuśrī or the buddha Akṣobhya.[23][24][25][26])

Iconography

[edit]

The iconography of Buddhist wrathful deities are usually considered to be derived from yaksha.

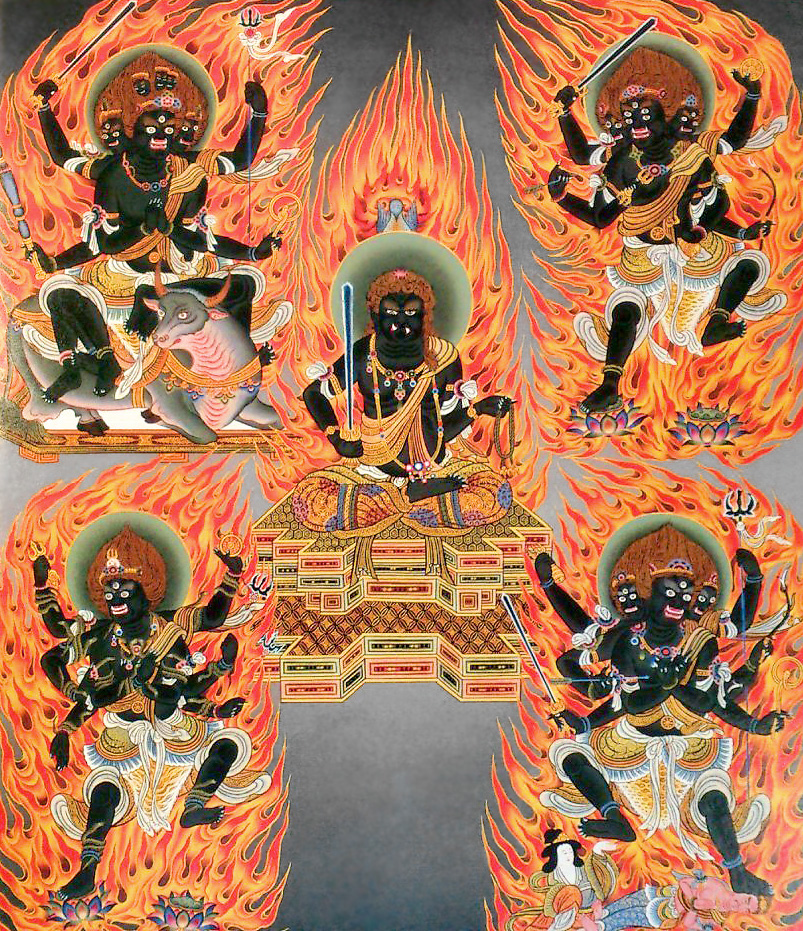

Wisdom Kings are usually represented as fierce-looking, often with blue or black skin and multiple heads, arms, and legs. They hold various weapons in their hands and are sometimes adorned with skulls, snakes or animal skins and wreathed in flames. This fiery aura is symbolically interpreted as the fire that purifies the practitioner and transforms one's passions into awakening, the so-called "fire samadhi" (火生三昧 kashō-zanmai).[27]

Certain vidyārājas bear attributes that reflect the historical rivalry between Hinduism and Buddhism. For instance, the Wisdom King Trailokyavijaya is shown defeating and trampling on the deva Maheśvara (one of the Buddhist analogues to Shiva) and his consort Umā (Pārvatī).[28] A commentary on the Mahavairocana Tantra by the Tang monk Yi Xing meanwhile attributes the taming of Maheśvara to another vidyārāja, Acala.

List of Wisdom Kings

[edit]The Five Wisdom Kings

[edit]In Chinese and Japanese (Shingon and Tendai) esoteric Buddhism, the Five Great Wisdom Kings (五大明王, Godai Myōō; Wǔdà Míngwáng), also known as the Five Guardian Kings, are a group of vidyārājas who are considered to be both the fierce emanations of the Five Wisdom Buddhas and the guardians of Buddhist doctrine.[29][30] Organized according to the five directions (the four cardinal points plus the center), the Five Kings are usually defined as follows:

- Acala / Acalanātha (Chinese: 不動明王; pinyin: Bùdòng Míngwáng; Japanese pronunciation: Fudō Myōō) - Manifestation of Mahāvairocana, associated with the center

- Trailokyavijaya (Chinese: 降三世明王; pinyin: Xiángsānshì Míngwáng; Japanese pronunciation: Gōzanze Myōō) - Manifestation of Akṣobhya, associated with the east

- Kuṇḍali / Amṛtakuṇḍalin (Chinese: 軍荼利明王; pinyin: Jūntúlì Míngwáng; Japanese pronunciation: Gundari Myōō) - Manifestation of Ratnasambhava, associated with the south

- Yamāntaka (Chinese: 大威徳明王; pinyin: Dàwēidé Míngwáng; Japanese pronunciation: Daiitoku Myōō) - Manifestation of Amitābha, associated with the west

- Vajrayakṣa (Chinese: 金剛夜叉明王; pinyin: Jīngāng Yèchā Míngwáng; Japanese pronunciation: Kongōyasha Myōō) - Manifestation of Amoghasiddhi, associated with the north in the Shingon school

- Ucchuṣma (Chinese: 烏枢沙摩明王; pinyin: Wūshūshāmó Míngwáng; Japanese pronunciation: Ususama Myōō) - Associated with the north in the Tendai school[31]

| Vajrayakṣa or Ucchuṣma

(north) |

||

| Yamāntaka

(west) |

Acala

(center) |

Trailokyavijaya

(east) |

| Kuṇḍali

(south) |

The Eight Wisdom Kings

[edit]In Chinese Buddhism, the Eight Great Wisdom Kings (八大明王; Bādà Míngwáng) is another grouping of Wisdom Kings that is depicted in statues, mural art and paintings. The acknowledged canonical source of the grouping of eight is The Sūtra of the Blazing Uṣṇīṣa of the Wondrous Vajra Kuṇḍali and Yamāntaka (大妙金剛大甘露軍拏利焰鬘熾盛佛頂經; Dàmiào Jīngāng Dà Gānlu Jūnnálì Yànmán Chìshèng Fódǐng Jīng).[32] Another canonical source for the grouping of eight is the Mañjuśrī-mūla-kalpa (大方廣菩薩藏文殊舍利根本儀軌經; Dà Fāngguǎng Púsà Zàng Wénshūshèlì Gēnběn Yíguǐ Jīng; 'The Fundamental Ordinance of Mañjuśrī'), the Chinese translation of which, completed in about 980-1000 CE, is attributed to the monk Tianxizai, who is possibly the north Indian Shantideva.[33] Each of the Wisdom Kings correspond to one of the Eight Great Bodhisattvas[zh] in Chinese Buddhism as well as to a specific compass direction.

The Eight Wisdom Kings, with exceptions in certain lists, are usually defined as:[33]

- Acala (不動明王; Bùdòng Míngwáng) - Manifestation of Sarvanivāraṇaviṣkambhin, associated with the north-east

- Kuṇḍali (軍荼利明王; Jūntúlì Míngwáng) - Manifestation of Ākāśagarbha, associated with the north-west

- Trailokyavijaya (降三世明王; Xiángsānshì Míngwáng) - Manifestation of Vajrapāṇi, associated with the south-east

- Yamāntaka (大威徳明王; Dàwēidé Míngwáng) - Manifestation of Mañjuśrī, associated with the east

- Mahācakra (大輪明王; Dàlún Míngwáng) - Manifestation of Maitreya, associated with the south-west

- Padanakṣipa (步擲明王; Bùzhì Míngwáng) - Manifestation of Samantabhadra, associated with the north

- Aparājita (無能勝明王; Wúnéngshèng Míngwáng) - Manifestation of Kṣitigarbha, associated with the south

- Hayagrīva (馬頭明王; Mǎtóu Míngwáng) - Manifestation of Avalokiteśvara (Guanyin), associated with the west

| Kuṇḍali

(north-west) |

Padanakṣipa

(north) |

Acala

(north-east) |

| Hayagrīva

(west) |

Yamāntaka

(east) | |

| Mahācakra

(south-west) |

Aparājita

(south) |

Trailokyavijaya

(south-east) |

The Ten Wisdom Kings

[edit]The more common grouping found in Chinese Buddhism is the Ten Great Wisdom Kings (十大明王; Shídà Míngwáng). Several groupings of the Ten Kings exist based on different canonical scriptural sources, each of which differ slightly in the naming of certain vidyārājas and attributing certain Kings to different Buddhas and bodhisattvas. Some examples of acknowledged canonical sources for the grouping of the Ten Wisdom Kings are The Sūtra of the Liturgy for Brilliant Contemplation of the Ten Wrathful Wisdom Kings of the Illusory Net of the Great Yoga Teachings (佛說幻化網大瑜伽教十忿怒明王大明觀想儀軌經; Fóshuō Huànhuàwǎng Dà Yújiājiào Shífènnù Míngwáng Dàmíng Guānxiǎng Yíguǐ Jīng) as well as The Sūtra with the Great Instructions that are Universal, Secret, and Unexcelled about the Contemplations of Mañjuśrī (妙吉祥平等秘密最 上觀門大教王經; Miàojíxiáng Píngděng Mìmì Zuìshàng Guānmén Dàjiàowáng Jīng).[33][32]

In contemporary Chinese Buddhist practice, the Ten Wisdom Kings are regularly invoked in ceremonies and rituals, such as the Shuilu Fahui ceremony, where they are provided offerings and entreated to expel evil from the ritual platform. In particular, ritual paintings of the Ten Wisdom Kings are arranged in a particular maṇḍala (壇; tán) during the Shuilu Fahui ceremony, with a particular direction associated with each Wisdom King.[34][35] The Wisdom King Ucchuṣma (穢跡金剛明王; Huìjì Jīngāng Míngwáng; 'Vajra Being of Impure Traces'), a manifestation of Śakyamuni, is not counted among the Ten Wisdom Kings in the ceremony, but he is still invoked separately from the grouping in the same ritual and his image is typically enshrined ahead of the outer north direction of the maṇḍala of the Ten Wisdom Kings. The specific list of the Ten Wisdom Kings invoked during the Shuilu Fahui ceremony, along with their associated directions in the maṇḍala, is canonized in the ceremony's ritual manual (水陸儀軌會本; Shuǐlù Yíguǐ Huìběn) based on scriptural sources.[36] They are as follows:[33][36]

- Acala (不動明王; Bùdòng Míngwáng) - Manifestation of Sarvanivāraṇaviṣkambhin, associated with the east

- Trailokyavijaya (降三世明王; Xiángsānshì Míngwáng) - Manifestation of Vajrapāṇi, associated with the outer south

- Kuṇḍali (軍荼利明王; Jūntúlì Míngwáng) - Manifestation of Amitābha, associated with the inner north

- Yamāntaka (大威徳明王; Dàwēidé Míngwáng) - Manifestation of the Mañjuśrī, associated with the north-east

- Mahācakra (大輪明王; Dàlún Míngwáng) - Manifestation of Maitreya, associated with the outer north

- Padanakṣipa (步擲明王; Bùzhì Míngwáng) - Manifestation of Samantabhadra, associated with the south-west

- Aparājita (無能勝明王; Wúnéngshèng Míngwáng) - Manifestation of Kṣitigarbha, associated with the inner south

- Hayagrīva (馬頭明王; Mǎtóu Míngwáng) - Manifestation of Avalokiteśvara (Guanyin), associated with the west

- Vajrahāsa (大笑明王; Dàxiào Míngwáng) - Manifestation of Ākāśagarbha, associated with the south-east

- Mahābala (大力明王; Dàlì Míngwáng) - Manifestation of Śakyamuni, associated with the north-west

| Mahācakra

(outer north) |

||

| Mahābala

(north-west) |

Kuṇḍali

(inner north) |

Yamāntaka

(north-east) |

| Hayagrīva

(west) |

Acala

(east) | |

| Padanakṣipa

(south-west) |

Aparājita

(inner south) |

Vajrahāsa

(south-east) |

| Trailokyavijaya

(outer south) |

- Ming dynasty mural of the Ten Wisdom Kings in Yong'an Temple[zh] in Hunyuan, Shanxi, China

-

Mahābala (Dàlì Míngwáng)

-

Hayagrīva (Mǎtóu Míngwáng)

-

Acala (Bùdòng Míngwáng)

-

Aparajita (Wúnéngshēng Míngwáng)

-

Yamāntaka (Dàwēidé Míngwáng)

-

Padanaksipa (Bùzhì Míngwáng)

-

Vajrahāsa (Dàxiào Míngwáng)

-

Trailokyavijaya (Xiángsānshì Míngwáng)

-

Kuṇḍali (Jūntúlì Míngwáng)

-

Mahācakra (Dàlún Míngwáng)

Others

[edit]

Other deities to whom the title vidyārāja is applied include:

- Rāgarāja (Chinese: 愛染明王; pinyin: Àirǎn Míngwáng; Japanese pronunciation: Aizen Myōō) - A vidyaraja considered to transform worldly lust and sexual passion into pathways to spiritual awakening; manifestation of the bodhisattva Vajrasattva and/or the buddha Vairochana.[37]

- Āṭavaka (Chinese: 大元帥明王; pinyin: Dàyuánshuài Míngwáng; Japanese pronunciation: Daigensui Myōō or 大元明王, Daigen Myōō) - A yaksha attendant of the deva Vaishravana.

- Mahāmāyūrī (Chinese: 孔雀明王; pinyin: Kǒngquè Míngwáng; Japanese pronunciation: Kujaku Myōō) - A Wisdom Queen (vidyārājñī); sometimes also classified as a bodhisattva. Unlike most other vidyārājas, s/he is depicted with a benevolent expression.

- Mahākrodharāja (Chinese: 大可畏明王; pinyin: Dàkěwèi Míngwáng; Japanese pronunciation: Daikai Myōō) - Attendant or manifestation of Amoghapasha (Chinese: 不空羂索観音; pinyin: Bùkōng Juànsuǒ Guānyīn; Japanese pronunciation: Fukū Kensaku/Kenjaku Kannon), one of Avalokiteshvara's forms.[38][39][40]

- Sadākṣara (Chinese: 六字明王; pinyin: Liùzì Míngwáng; Japanese pronunciation: Rokuji Myōō) - A deification of the Sadākṣara (Six-Letter) Sutra Ritual (Japanese: 六字経法; rōmaji: Rokuji-kyō hō), a rite of subjugation focused on the six manifestations of Avalokiteshvara.[41] Unlike other Wisdom Kings but like Mahamayuri, he sports a gentle bodhisattva-like countenance and is shown with four or six arms and standing on one leg.[42][43][44]

Examples

[edit]

Examples of depictions of the Eight Wisdom Kings can be found at:

- Cliff reliefs and rock carvings at Shizhongshan Grottoes[zh] in Jianchuan, Yunnan

- Statues in the Datong Guanyin-tang[zh] in Datong, Shanxi

- Frescos in the pagoda at Jueshan Temple[zh] in Lingqiu, Shanxi

Examples of depictions of the Ten Wisdom Kings can be found at:

- Rock carvings at the Dazu Rock Carving sites in Dazu, Chongqing

- Statues in Shuanglin Temple near Pingyao, Shanxi

- Statues in Shuilu Nunnery[zh] in Lantian, Xi'an

- Frescos in Qinglong Temple in Jishan, Shanxi

- Frescos in Yong'an Temple[zh] in Hunyuan, Shanxi

- Frescos in Yunlin Temple[zh] in Yanggao, Shanxi

- Frescos in Pilu Temple[zh] in Shijiazhuang, Hebei

- Frescos in Dayun Temple[zh] in Hunyuan, Shanxi

- Shuilu ritual paintings from various temples, such as Baoning Temple[zh] in Youyu, Shanxi (Currently kept in the Shanxi Museum)

- Documents and carvings from the Mogao Caves near Dunhuang, Gansu

Gallery

[edit]-

Tang dynasty statue of Acala, now kept at the Forest of Steles, Beilin Stone Museum in Xi'an, Shaanxi Province, China

-

Head of a Qing dynasty statue of Hayagrīva, now held in the Gansu Provincial Museum, Lanzhou, Gansu, China

-

Liao dynasty (916-1125) statutes of four of the Eight Wisdom Kings and an attendant warrior at Datong Guanyin-tang[zh], Datong, Shanxi, China. From left to right: Padanakṣipa, Acala, Yamāntaka, Aparājita

-

Liao dynasty (916-1125) statutes of four of the Eight Wisdom Kings and an attendant warrior at Datong Guanyin-tang[zh], Datong, Shanxi, China. From left to right: Hayagrīva, Vajrahāsa, Mahācakra, Mahāmāyūrī

-

Trailokyavijaya in the Buddhist relic collection at the Buddha Tooth Relic Temple and Museum (Chinatown, Singapore)

-

Statue of Āṭavaka at Akishino-dera, Nara, Japan

See also

[edit]- Dharmapāla and Lokapāla, guardian deities

- Zaō Gongen

References

[edit]- ^ Toganoo, Shozui Makoto (1971). "The Symbol-System of Shingon Buddhism (1)". Journal of Esoteric Buddhism – Mikkyō Bunka: 91, 86.

- ^ a b Haneda (2018), pp. 25–27.

- ^ Mack (2006), p. 298.

- ^ Faure (2015a), p. 116.

- ^ Linrothe (1999), p. 90.

- ^ Linrothe (1999), p. 13, 64-65.

- ^ Linrothe (1999), p. 13.

- ^ Baroni (2002), p. 100.

- ^ Miyasaka (2006), p. 56.

- ^ Shōwa shinsan Kokuyaku Daizōkyō: Kaisetsu 昭和新纂国訳大蔵経 解説部第1巻 (in Japanese). Vol. 1. Tōhō Shuppan. 1930. p. 120.

- ^ 三輪身. コトバンク (kotobank) (in Japanese). Retrieved 2020-11-28.

- ^ Linrothe (1999), p. 64-67.

- ^ Linrothe (1999), pp. 68–81.

- ^ a b Linrothe (1999), pp. 163–175.

- ^ Linrothe (1999), pp. 155.

- ^ 3. 両界曼荼羅(りょうかいまんだら). Shingon-shū Sennyū-ji-ha Jōdo-ji Official Website. Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ^ "Vajratiksna". English Tibetan Dictionary Online. Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ^ 大威徳明王. コトバンク (Kotobank). Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ^ 大威徳明王. Shingon-shū Buzan-ha Kōki-zan Jōfuku-ji Official Website. Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ^ Linrothe (1999), pp. 85–91.

- ^ Chandra (1988), pp. 29–31.

- ^ Faure (2015a), pp. 120–123.

- ^ Pal (1974), p. 6.

- ^ "Acala, The Buddhist Protector". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2020-11-28.

- ^ Jha (1993), pp. 35–36.

- ^ "Sacred Visions: Early Paintings from Central Tibet - Achala". www.asianart.com. Retrieved 2020-11-28.

- ^ Faure (2015a), p. 117.

- ^ Linrothe (1999), pp. 178–187.

- ^ De Visser (1928), pp. 143–151.

- ^ Vilbar, Sinéad (October 2013). "Kings of Brightness in Japanese Esoteric Buddhist Art". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2021-10-01.

- ^ 五大尊. Flying Deity Tobifudō (Ryukō-zan Shōbō-in Official Website). Retrieved 2021-10-01.

- ^ a b Huang, Yongjian (2000). 蘇曼殊繪畫硏究 (Thesis). The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology Library. doi:10.14711/thesis-b685589.

- ^ a b c d Howard (2002), pp. 92–107.

- ^ Bloom, Phillip Emmanual (2013). Descent of the Deities: The Water-Land Retreat and the Transformation of the Visual Culture of Song-Dynasty (960–1279) Buddhism (Thesis). OCLC 864907811. ProQuest 1422026705.[page needed]

- ^ Hong, Tsai-Hsia (2005). The Water-Land Dharma Function Platform Ritual and the Great Compassion Repentance Ritual. OCLC 64281400.[page needed]

- ^ a b 上海佛学书局, 水陸儀軌會本 卷1-卷4 (PDF), retrieved 2025-05-06

- ^ "愛染明王". Flying Deity Tobifudo (Ryūkō-zan Shōbō-in Official Website). Retrieved 2021-10-16.

- ^ Linrothe (1999), p. 89.

- ^ 仏像がわかる! バックナンバー4・明王部. Kōya-san Shingon-shū Hōon-in Official Website. Retrieved 2021-10-02.

- ^ 不空大可畏明王央俱拾真言 (PDF). JBox-智慧宝箧. Retrieved 2021-10-02.

- ^ Fuji, Tatsuhiko (2012). 呪法全書 (Juhō Zensho). Gakken Plus. ISBN 978-4-0591-1008-8.

- ^ 円成庵 木造六字尊立像. 2017年度 文化財維持・修復事業助成 助成対象. The Sumitomo Foundation. Retrieved 2021-10-16.

- ^ 木造六字明王立像. Takamatsu City Official Website. Retrieved 2021-10-16.

- ^ 六字明王. Flying Deity Tobifudo (Ryūkō-zan Shōbō-in Official Website). Retrieved 2021-10-16.

Further reading

[edit]- Baroni, Helen Josephine (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Zen Buddhism. New York: Rosen Pub. Group. ISBN 0-8239-2240-5.

- Chandra, Lokesh (1988). The Thousand-Armed Avalokiteśvara, Volume 1. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-8-1701-7247-5.

- De Visser, Marinus Willem (1928). Ancient Buddhism in Japan. Brill Archive.

- Faure, Bernard (2015a). The Fluid Pantheon: Gods of Medieval Japan, Volume 1. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-5702-8.

- Faure, Bernard (2015b). Protectors and Predators: Gods of Medieval Japan, Volume 2. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-5772-1.

- Haneda, Shukai (2018). 不動明王から力をもらえる本 (Fudō Myōō kara chikara o moraeru hon) (in Japanese). Daihōrinkaku. ISBN 978-4-8046-1386-4.

- Howard, Angela F. (1999-03-01). "The Eight Brilliant Kings of Wisdom of Southwest China". Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics. 35: 92–107. doi:10.1086/RESv35n1ms20167019. ISSN 0277-1322. S2CID 164236937. Archived from the original on 2021-08-24. Retrieved 2021-08-24.

- Jha, Achyutanand (1993). Tathagata Akshobhya and the Vajra Kula: Studies in the Iconography of the Akshobhya Family. National Centre for Oriental Studies.

- Linrothe, Robert N. (1999). Ruthless Compassion: Wrathful Deities in Early Indo-Tibetan Esoteric Buddhist Art. Serindia Publications, Inc. ISBN 978-0-9060-2651-9.

- Mack, Karen (2006). "The Phenomenon of Invoking Fudō for Pure Land Rebirth in Image and Text". Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 33 (2): 297–317. JSTOR 30234078.

- Miyasaka, Yūshō (2006). 不動信仰事典 (Fudō-shinkō Jiten) (in Japanese). Ebisu Kōshō Shuppan. ISBN 978-4-900901-68-1.

- Pal, Pratapaditya (1974). The Arts of Nepal - Volume II: Painting. Brill Archive. ISBN 978-90-04-05750-0.

Wisdom King

View on Grokipedia- Fudō Myō-ō (Acala, the Immovable One), central guardian and emanation of Vairocana; holds a sword to sever delusions and a lasso to restrain evil, often accompanied by child attendants; widely venerated across Buddhist sects for personal protection.[1][2]

- Gōzanze Myō-ō (Trailokyavijaya, Conqueror of the Three Worlds), eastern protector linked to Akṣobhya; multi-armed with a vajra and noose to subdue demonic realms.[1][2]

- Gundari Myō-ō (Kuṇḍali, Dispenser of Heavenly Nectar), southern guardian associated with Ratnasambhava; depicted with serpents and a wish-fulfilling jewel to purify defilements.[1][2]

- Daiitoku Myō-ō (Yamāntaka, Terminator of Death), western protector of Amitābha; eight-headed and multi-armed, clutching a sword and elephant-goad to overcome mortality and greed.[1][2]

- Kongōyasha Myō-ō (Vajrayakṣa, Devourer of Demons), northern guardian tied to Amoghasiddhi; fierce with a vajra and serpent noose to destroy illusions and obstacles.[1][2]

Definition and Role

Etymology and Terminology

The Sanskrit term for a Wisdom King is vidyārāja (विद्याराज), composed of vidyā ("knowledge," "wisdom," or specifically in esoteric Buddhist contexts, "magical knowledge" or "spells" referring to mantras and dhāraṇīs) and rāja ("king"). This yields the literal translation "king of knowledge" or "wisdom king," emphasizing their embodiment of enlightened insight manifested through ritual incantations.[5] In East Asian traditions, the term is rendered as Chinese míng wáng (明王), where míng evokes "brightness" or "illumination" to capture the radiant quality of wisdom, and Japanese myō-ō (明王), using the same characters with phonetic adaptation.[6] These translations preserve the core notion of sovereign mastery over transformative esoteric knowledge while adapting to linguistic and cultural nuances. Related terminology includes vidyārājñī (विद्याराज्ञी), denoting female counterparts known as "wisdom queens," who similarly personify protective mantras but in feminine form, as seen in figures like Mahāmāyūrī.[7] The concept of vidyārājas as a distinct class of wrathful deities first emerges in key tantric texts, notably the Mahāvairocana Sūtra (Vairocana-bhisambodhi Sūtra), composed in the 7th century CE and translated into Chinese in 724 CE, where they are described as emanations of Vairocana Buddha guarding the mandala's boundaries.[8]Theological Function in Esoteric Buddhism

In Esoteric Buddhism, Wisdom Kings (Sanskrit: Vidyārājas) function as enlightened manifestations of prajñā, or transcendent wisdom, designed to dismantle ignorance (avidyā) and delusions that obstruct the path to awakening. As wrathful emanations of buddhas or bodhisattvas, they embody the fierce aspect of compassion, wielding their power not for personal gain but to shatter the mental fetters binding sentient beings to saṃsāra. This doctrinal role positions them as indispensable allies in tantric sādhanas, where their invoked presence accelerates the practitioner's realization by directly confronting and dissolving karmic obstructions.[9] Central to their theological framework is their association with the Five Wisdom Buddhas, serving as their dynamic, transformative counterparts. Each Wisdom King channels the wisdom of a corresponding buddha, such as Acala (Fudō Myōō) manifesting Vairocana's all-pervading wisdom to immobilize delusions. In Japanese Esoteric traditions, this linkage is systematized through the sanrinjin (three-wheel bodies) theory, which posits the Wisdom Kings as the "wheel body of mysterious activity" corresponding to the wisdom buddhas' self-nature wheel and the bodhisattvas' teaching wheel, actively converting phenomenal hindrances into enlightened qualities.[10] Within tantric practices, Wisdom Kings fulfill protective roles by warding off external threats like malevolent spirits or internal ones like doubt, often through mantra recitation that harnesses their vidyā (esoteric knowledge) to purify the practitioner's continuum. They facilitate the transmutation of defilements—the three poisons of greed, hatred, and delusion—into corresponding wisdoms, as seen in rituals like the homa fire offering, where symbolic burning invokes their agency to alchemize afflictions into the basis for enlightenment. This process underscores their function as doctrinal enforcers, ensuring the integrity of the Dharma against erosion.[4] Unlike devas, who are impermanent celestial beings ensnared in cyclic existence and motivated by worldly desires, or mārās, demonic forces that perpetuate suffering, Wisdom Kings are fully enlightened entities whose wrathful demeanor arises purely from compassion (karuṇā). Their actions represent upāya, or skillful means, tailored to shock and liberate those unresponsive to gentler teachings, thereby distinguishing them as supreme guardians of the Buddhist path rather than subordinate or adversarial powers.[9]Historical Development

Origins in Indian Tantric Traditions

The Wisdom Kings, known in Sanskrit as Vidyārājas, first emerged in Indian Tantric Buddhism during the late 6th to 7th centuries as subsidiary wrathful figures serving as attendants to principal Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in esoteric mandalas and rituals.[11] Early tantric texts such as the Guhyāsamāja Tantra, composed around the 8th century but drawing on earlier traditions, positioned these deities within complex assemblies to embody the transformative power of enlightened wisdom, often manifesting to protect practitioners from obstacles.[11] Similarly, the Mahāvairocana Sūtra, a foundational esoteric scripture from the mid-7th century, describes Vidyārājas like Trailokyavijaya and Acala as emanations of the cosmic Buddha Mahāvairocana, aiding in the subjugation of hindrances and the establishment of ritual purity.[11] These initial depictions emphasized their role in bridging exoteric Mahāyāna practices with emerging tantric methods, where they functioned as dynamic enforcers of the Dharma. In their formative stages, Wisdom Kings appeared as wrathful Bodhisattvas, adapting fierce iconography from Shiva-like Hindu deities to assert Buddhist supremacy and neutralize adversarial forces. For instance, Yamāntaka, the "conqueror of death," originated as an emanation of Mañjuśrī, modeled after the Vedic god Yama and Shaivite forms such as Bhairava, complete with a buffalo mount, black complexion, and tiger-skin attire to symbolize the destruction of ego and mortality.[11] This adaptation is evident in texts like the Mañjuśrīmūlakalpa, which details Yamāntaka's deployment to trample death personified, reflecting a strategic incorporation of non-Buddhist elements to subjugate deities like Maheśvara (Shiva) and integrate them into Buddhist cosmology.[11] Such forms underscored the tantric principle of converting destructive energies into enlightened activity, with sculptural evidence from sites like Aurangabad Cave 7 (late 6th/early 7th century) illustrating these hybrid figures in attendant roles.[11] Central to early tantric practice, Wisdom Kings played a protective role in vidyā (mantra) traditions, wielding dhāranīs and spells to ward off malevolent spirits, purify internal defilements, and secure sacred spaces for initiates. In the Dhāraṇīsaṃgraha (compiled 653 CE), Hayagrīva emerges as a four-headed, horse-maned attendant to Avalokiteśvara, embodying sonic power through neighing mantras to dispel calamities and enemies.[11] These practices, rooted in the esoteric emphasis on mantra as a tool for empowerment, positioned Vidyārājas as indispensable guardians, transforming fear into faith and obstacles into paths of realization.[11] By the 8th century, texts like the Hevajra Tantra further developed these concepts, portraying wrathful figures such as Hevajra— a multi-limbed, blue-skinned deity crushing Māras— as supreme manifestations integrating wisdom and method to overcome delusions.[11] This tantra, emphasizing completion-stage practices, highlights the Vidyārājas' evolution toward embodying the non-dual union of compassion and emptiness, influencing subsequent esoteric lineages while maintaining their Indian tantric foundations.[11]Transmission and Evolution in East Asia

The transmission of Wisdom Kings (Sanskrit: Vidyarāja) to East Asia began with the spread of esoteric Buddhism during the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) in China, where they evolved from minor attendants to bodhisattvas into a distinct pantheon of protective deities. Although evidence for their presence in China prior to the 6th century is sparse, reflecting the gradual integration of tantric elements into Mahayana traditions, by the 8th century, Vidyarāja had gained significant prominence, as seen in artifacts like bells inscribed with their figures and sutras such as the Mahamayuri Vidyarajni Sutra, which emphasized their role in warding off calamities like poison and invasion.[1][4][12] This development was bolstered by the Tang court's patronage of esoteric practices, culminating in a full pantheon by the dynasty's end, with texts and rituals adapting Indian tantric origins to Chinese contexts.[4] In the early 9th century, Japanese monks Saichō (767–822 CE) and Kūkai (774–835 CE) facilitated the transmission from Tang China to Japan, importing scriptures, mandalas, and ritual manuals that prominently featured Wisdom Kings. Saichō, founder of the Tendai sect, incorporated them into his synthesis of esoteric and exoteric teachings after his studies in China, while Kūkai, who established the Shingon sect upon his return in 806 CE, emphasized their centrality in mandalas like the Taizōkai and Kongōkai, viewing them as emanations of Dainichi Nyorai (Vairocana).[1][4] These imports marked a pivotal evolution, as Wisdom Kings became integral to Japanese esoteric Buddhism, adapting to local needs through the Shingon and Tendai sects' rituals for protection and enlightenment.[13] In Japan, Wisdom Kings achieved particular prominence in esoteric practices from the Heian period (794–1185 CE) onward, with Acala (Japanese: Fudō Myōō) emerging as a national protector invoked to safeguard the imperial court and the realm from threats like rebellion and disaster. This role was formalized in state-sponsored rituals, such as those based on the Benevolent Kings Sutra, where the Five Great Wisdom Kings were collectively summoned to ensure national stability, reflecting their adaptation from Chinese models to Japan's political and spiritual landscape.[1][13]Iconography and Symbolism

Physical Depictions

Wisdom Kings, known as Vidyārāja in Sanskrit, are characteristically portrayed in esoteric Buddhist art with intensely wrathful physical forms to embody their function as fierce protectors of the Dharma. These depictions emphasize multi-faced and multi-armed configurations, often featuring multiple faces and arms, with the number varying by specific Wisdom King (for example, three faces and six or eight arms for some like Gōzanze Myō-ō, while Fudō Myō-ō has one face and two arms), which allow for a multifaceted representation of their all-encompassing wisdom and power. The faces display exaggerated fierce expressions, including bulging or rolling eyes, protruding fangs, and contorted grimaces with one canine tooth often visible from the upper jaw and another from the lower, signifying the subjugation of defilements.[4][14] Their bodily postures convey dynamic energy and unyielding resolve, most notably in the alidha stance, where the right leg is extended forward and the left knee is bent backward, evoking a warrior's readiness to advance against obstacles. This aggressive pose, rooted in Indian tantric iconographic traditions, underscores their role in trampling ignorance and demonic forces, with the figure often appearing erect and towering to amplify their intimidating presence. In some representations, such as those of Acala (Fudō Myō-ō), the body adopts a more static seated or standing position on a rock base, yet retains the overall menacing demeanor through wavy locks of hair piled high and a stocky, childlike build.[11][1] Surrounding elements enhance the volatile aura of these figures, with wreaths of flames or swirling smoke encircling their forms in elaborate mandorlas, symbolizing the transformative fire of wisdom that consumes delusions. Many Wisdom Kings are shown standing atop prostrate human or demonic figures, which represent the ego or malevolent entities being subdued underfoot. Color variations distinguish individual kings and align with elemental or directional associations; for instance, Acala is rendered in deep blue-black, evoking immovability and the void, while others like Aizen Myō-ō appear in vivid red to denote passion transmuted into enlightenment.[1][4]Attributes, Weapons, and Symbolic Elements

In Esoteric Buddhism, Wisdom Kings (Vidyārāja) are typically depicted wielding specific weapons that embody the transformative power of wisdom to overcome spiritual obstacles. The sword, often a flaming vajra sword, symbolizes the cutting through of ignorance and delusions, representing the sharp discernment of prajñā (wisdom) that severs the roots of samsaric suffering.[15][16] The noose or lasso serves to bind and subdue malevolent forces or wandering spirits, metaphorically capturing and redirecting negative karma toward enlightenment, thus enforcing the protective aspect of the Dharma.[15][17] The wheel, akin to the dharmachakra, signifies the turning of the wheel of the Buddhist teachings, ensuring the continuity and unhindered propagation of the Dharma while preventing doctrinal regression.[15] Flames encircling the figures of Wisdom Kings represent the purifying fire of wisdom that incinerates accumulated karma and defilements, transforming wrathful energy into a force for spiritual renewal and the destruction of obstacles to practice.[16][17] Skull cups, sometimes held or incorporated into staffs, evoke the transience of worldly attachments and the conquest of deathly illusions, holding the nectar of immortality as a ritual emblem of transcending samsara.[15] Lotuses, often blue for wisdom or red for compassion, underscore purity emerging from defilement, symbolizing the enlightened mind's ability to bloom amid adversity in meditative visualizations.[15][16] Seed syllables (bīja mantras), such as "hūṃ" or variants like "hāṃ," are inscribed on the bodies or hearts of Wisdom Kings during visualization practices, encapsulating their essence as sonic embodiments of enlightened awareness that practitioners recite to invoke protective energies and align with the deity's wisdom.[18] These mantras facilitate ritual concentration, where the syllable's vibration aids in dissolving ego-clinging and manifesting the deity's qualities internally.[18] Wisdom Kings are predominantly portrayed as male figures, embodying fierce, unyielding authority in safeguarding the teachings, yet they connect to female counterparts known as Wisdom Queens (vidyārājñī), who represent complementary aspects of enlightened activity; for instance, figures like Kurukullā link to this tradition as embodiments of magnetizing wisdom that draws beings toward liberation.[15][19]Major Classifications

The Five Wisdom Kings

The Five Wisdom Kings, known as the Godai Myōō in Japanese Esoteric Buddhism, represent wrathful manifestations of the five Dhyani Buddhas, serving as fierce protectors of the Dharma who subjugate delusions and obstacles to enlightenment through their terrifying forms and symbolic attributes.[1] These deities are arranged in a pentadic mandala corresponding to the five directions, colors, and elements, facilitating meditative visualization and ritual practices to invoke their protective powers and transform negative passions into wisdom.[4] Each king embodies the enlightened qualities of their associated Buddha, wielding weapons that symbolize the cutting of ignorance and the binding of evil forces. Acala, also known as Acalanātha or Fudō Myōō, occupies the center in the mandala and corresponds to Vairocana Buddha, with associations to the fire element that signifies purification and immovability.[4] Depicted in dark blue or black hues to evoke unyielding stability, Acala holds a flaming sword in his right hand to sever delusions and a noose in his left to bind afflictions, often seated on a rock pedestal amid encircling flames that burn away impurities.[1] His third eye and wrathful glare emphasize his role in safeguarding the Buddhist teachings against ignorance and external threats, embodying the "immovable" wisdom that remains unshaken by worldly disturbances.[4] Kuṇḍali Vidyarāja, or Gundari Myōō, is positioned in the south and linked to Ratnasambhava Buddha, characterized by the yellow color symbolizing equality and the earth's nurturing fertility.[4] He is portrayed with eight arms, snakes coiled around his body and ankles as a noose-like attribute to invoke protective energies against malevolent spirits, and a fierce expression that wards off devils and invokes heavenly nectar for spiritual enrichment.[4] This configuration highlights Kuṇḍali's function in dispelling pride and fostering equanimity, channeling the jewel-like generosity of Ratnasambhava to protect practitioners from harm.[20] Vajrayakṣa Vidyarāja, or Kongōyasha Myōō, guards the north and manifests Amoghasiddhi Buddha's all-accomplishing wisdom, aligned with the green color representing accomplishment and the wind element's dynamic force.[4] With three faces, six arms wielding a vajra bell, bow, wheel, and sword to purify defilements and devour demonic influences, Vajrayakṣa tramples filth and obstacles, symbolizing the eradication of foolish desires through indestructible vajra energy.[4] His lotus base underscores themes of enlightened activity, aiding meditators in cleansing karmic impurities for unhindered spiritual progress.[20] Trailokyavijaya, or Gōzanze Myōō, dominates the east and corresponds to Akṣobhya Buddha, embodying mirror-like wisdom in blue tones that reflect the water element's clarity and the conquest of anger.[4] Featuring eight arms holding an arrow of mercy, sword, and staff, he tramples the figures of Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva to subjugate the three realms of existence—desire, form, and formlessness—thus overcoming egotism and worldly attachments.[4] This iconography illustrates Trailokyavijaya's power to vanquish ignorance and hatred, integrating non-Buddhist deities into the fold of enlightenment.[20] Yamāntaka, referred to as Daiitoku Myōō, presides over the west and aligns with Amitābha Buddha, associated with the red color denoting discriminating wisdom and the fire element's transformative passion.[4] Portrayed with six faces—including a central buffalo head—six arms grasping weapons like a chopper and skull-cup, and riding a white buffalo or cow, Yamāntaka conquers Yama, the lord of death, to liberate beings from the cycle of suffering and poisons.[1] His multi-limbed form suppresses evil influences and guards the Western Pure Land, emphasizing victory over mortality and the redirection of desire toward boundless compassion.[4] In Esoteric Buddhist practice, these five kings form the core of the Vidyarāja mandala, with Acala at the center radiating to the four cardinal directions, used in meditation to visualize their protective array and in rituals such as fire offerings (goma) to invoke collective guardianship over the sangha and nation.[1] This arrangement, rooted in texts like the Benevolent Kings Sutra, enables practitioners to harness the kings' wrathful compassion for personal transformation and cosmic harmony.[20]The Eight Wisdom Kings

The Eight Wisdom Kings represent an expanded classification in esoteric Buddhism, augmenting the core pentad with three additional wrathful deities to encompass comprehensive protection across all directions and realms. This octet is prominently featured in the Vajraśekhara Sūtra (Kongōchō-kyō), a foundational tantric text transmitted to East Asia and central to Shingon Buddhism's doctrinal framework, where the kings embody the fierce aspects of enlightened wisdom to conquer inner and outer obstacles.[4] The unique additions to the five are Ucchuṣma (Ususama Myōō), associated with purification of afflictions and healing; Hayagrīva, depicted with a horse head and tasked with subduing nāgas and other serpentine forces; and Candarāśi, the unconquerable king who provides overarching protection against calamities.[4][21] Each of these kings, alongside the core five such as Acala, is positioned in a directional mandala layout distinct from the pentad's central focus, with Acala guarding the southeast and the others aligned to the remaining directions for total encirclement.[4] Furthermore, the Eight Wisdom Kings are each paired with one of the eight great bodhisattvas—such as Mañjuśrī for Acala—symbolizing the integration of wrathful expediency with compassionate wisdom in esoteric practice.[4] In Japanese Shingon traditions, this grouping is invoked during goma fire rituals, where their mantras and visualizations facilitate the burning away of defilements and the summoning of protective energies.[4] While the core five are primarily tied to the five wisdom buddhas, the octet extends this to a holistic safeguard aligned with the eightfold path of enlightenment.[21]Extended and Regional Variations

The Ten Wisdom Kings

The Ten Wisdom Kings form a ritual-specific decadic grouping of wrathful deities in Chinese and Japanese Esoteric Buddhism, expanding the directional protections beyond the core five or eight classifications to encompass the full ten directions of the cosmos, including zenith and nadir. This arrangement overlaps with the major groupings by incorporating four of the primary five Wisdom Kings (Acala, Trailokyavijaya, Kuṇḍali, and Vajrayakṣa) as key figures while adding supplementary protectors for comprehensive ritual safeguarding. Originating in China during the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE), the configuration was formalized in liturgical manuals such as the Fozu tongji by the Tiantai monk Zhipan (1220–1275), reflecting integrations into Chan, Tiantai, and Pure Land practices for universal salvation rites.[22] In the Shuilu Fahui (Water-Land Dharma Assembly), a grand ritual for nourishing and liberating all sentient beings across realms of water and land, the Ten Wisdom Kings are invoked and arranged in a maṇḍala on the second tier of the Precept Altar of the Five Directions or the Upper Hall of the ritual site. Their directional associations align with Buddhist cosmology fused with Chinese cardinal points, such as Acala (Bùdòng Míngwáng) to the east, Trailokyavijaya (Jiàngsānshì Míngwáng) to the south, Kuṇḍali (Jūntílì Míngwáng) to the southeast, Vajrayakṣa (Jīngāngyèshā Míngwáng) to the southwest, and extensions to other quarters like Yamāntaka (Dàxiǎo Míngwáng) for the north, Hayagrīva (Mǎtóu Míngwáng) for the northeast, along with assignments for northwest, west, zenith, and nadir to cover the complete spatial expanse.[22][23] The primary purpose of this grouping in the Shuilu Fahui is to protect the ritual platform from obstructive forces, expiate collective sins, and guide deceased souls—particularly wandering spirits and hungry ghosts—toward rebirth or enlightenment by subduing defilements across all directions. Performed over seven to forty-nine days, the rite summons these kings alongside Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and other assemblies to offer feasts and merits, ensuring the deceased receive aid in navigating purgatorial realms.[22][23] Distinguishing the ten from the eight Wisdom Kings, this expanded set incorporates outer protectors such as Ucchuṣma (Wūchūshì Míngwáng), the impurity-purifying deity who wields a fiery sword against filth, and Rāgarāja (Qíngbó Míngwáng), the subduer of passionate attachments through his binding noose and flames. These additions enhance the ritual's efficacy in comprehensive purification and directional guardianship, drawing from Tang Esoteric influences like those of masters Vajrabodhi and Amoghavajra, while adapting to Song-era syncretic needs.[22]| Wisdom King (Sanskrit/Chinese) | Directional Association (Example) | Key Function in Ritual |

|---|---|---|

| Acala (Bùdòng Míngwáng) | East | Immovable guardian against hindrances[22] |

| Trailokyavijaya (Jiàngsānshì Míngwáng) | South | Victor over the three realms, subduing delusions[22] |

| Kuṇḍali (Jūntílì Míngwáng) | Southeast | Binding of negative forces with noose and wheel[22] |

| Vajrayakṣa (Jīngāngyèshā Míngwáng) | Southwest | Yakṣa protection, devouring obstacles with fangs[22] |

| Yamāntaka (Dàxiǎo Míngwáng) | North | Death-conqueror, laughing at Yama to free souls[22] |

| Hayagrīva (Mǎtóu Míngwáng) | Northeast | Horse-headed ferocity against ignorance[22] |

| Suratha (Bùzhì Míngwáng) | Northwest | Stomping subjugation of earthly attachments[22] |

| Rāgarāja (Qíngbó Míngwáng) | West | Subduer of desire, binding passions with flames[22] |

| Ucchuṣma (Wūchūshì Míngwáng) | Zenith | Purification of impurities through fire and sword[22] |

| Mahācakra (Dàlún Míngwáng) | Nadir | Great wheel turnover for karmic resolution[22] |

Other Notable Wisdom Kings

Rāgarāja, known in Japanese esoteric Buddhism as Aizen Myōō (愛染明王), is a prominent Wisdom King revered for transforming worldly passions, particularly lust and desire, into pathways for spiritual enlightenment, embodying the tantric principle of bonnō soku bodai (delusions are identical with enlightenment).[1][24] Originating from Indian tantric traditions as a vidyarāja associated with the Hindu deity Kāma, Aizen Myōō was integrated into Shingon Buddhism by the monk Kūkai in the 9th century, where he serves as a protector deity invoked in rituals to purify attachments and foster compassion.[24] His iconography typically depicts a fierce, bright red figure with a lion-head crown that symbolizes the devouring of defiling thoughts, seated on a lotus throne amid spilling jewels representing abundance; he possesses multiple arms—often six—wielding a vajra, bell, lotus bud, and notably a bow and arrow borrowed from Kāma to pierce and redirect desires toward awakening.[1][25] In practices at sites like Mount Kōya, variants such as the two-headed Ryōzu Aizen emphasize his dual role in exorcism and desire subjugation, historically employed in 13th-century Shugendō rituals to combat malevolent forces.[25] In Tibetan Vajrayāna Buddhism, a prominent wrathful deity analogous to the Wisdom Kings is Yamantaka (Tibetan: gShin-rje gshed; Sanskrit: Yamāntaka), the "Destroyer of Death," who stands as a major yidam (meditational deity) especially in the Gelug tradition, manifesting the wrathful aspect of Mañjuśrī, the Buddha of Wisdom, to conquer ignorance, ego, and the lord of death, Yama.[26] Popularized by Tsongkhapa as one of the principal Highest Yoga Tantra practices alongside Guhyasamāja and Cakrasamvara, Yamantaka's sadhana involves visualizing his multi-headed, multi-limbed form to overcome the four māras (demons of death, passion, aggregates, and devas), transforming anger into insightful compassion.[26] His unique iconography centers on a dark blue buffalo head—symbolizing dominion over Yama's beast—crowned by Mañjuśrī's serene face amid nine heads total, with thirty-four arms wielding weapons to sever delusions and sixteen legs trampling obstructors, often depicted in mandalas like the Thirteen-Deity or Solitary Hero forms for initiations in Gelug monasteries.[27] This buffalo-headed ferocity underscores his role in tantric antinomianism, where practitioners identify with his form to realize emptiness and non-duality, making him a cornerstone for advanced Gelug meditators seeking swift enlightenment.[26]Representations in Art and Practice

Artistic Examples

In the Dazu Rock Carvings of Chongqing, China, dating from the 9th to 13th centuries, multi-figure groups depict Acala, known as the Wisdom King, alongside attendant boys (tongzi) serving as acolytes to Buddhas and bodhisattvas in the Daboruodong cave complex. These carvings illustrate five boys arranged symmetrically on the sidewalls in three layers, emphasizing esoteric Buddhist themes of protection and enlightenment within larger assemblages of deities.[28] Additionally, the Baodingshan site features representations of the Ten Great Vidyarajas (Wisdom Kings), including Acala, integrated into expansive cliffside ensembles that blend Tantric Buddhist motifs with local sculptural traditions.[28][29] The Baoning Temple in Shanxi Province, China, houses Ming dynasty murals from around the 15th century that portray the Ten Wisdom Kings as part of Water-Land ritual assemblies, showcasing their wrathful forms in ink and color on silk to invoke divine protection and salvation. These paintings, now preserved in the Shanxi Provincial Museum, depict the kings as manifestations of Buddhas, arranged in hierarchical compositions that highlight their roles in esoteric cosmology.[30] In Japan, Acala (Fudō Myōō) statues from the Heian period (794–1185) exemplify early esoteric influences at key monastic sites. At Mount Kōya's Shōchiin sub-temple, a seated cypress wood statue from the early Heian period, the oldest extant standing Acala at the site, features wide-open eyes and a large lotus crown, conveying unyielding resolve through its weighted, single-block form.[31] Similarly, at Enryakuji Temple on Mount Hiei, a 10-centimeter gold-plated standing Fudō Myōō statue, discovered concealed within a larger wooden figure, dates to the Heian period or earlier and exemplifies portable esoteric iconography with its fierce expression and dynamic posture.[32] Tibetan thangkas from the 15th century onward frequently illustrate Yamantaka mandalas, portraying the Wisdom King as a central multi-headed, multi-armed deity conquering death within intricate palace structures. A notable example is the Yamantaka Palace Mandala, featuring layered views of the deity's interior realm surrounded by retinues, painted in mineral pigments on cotton to aid meditation on tantric subjugation of ego.[33] Another late 15th-century thangka from Central Tibet depicts Yamantaka's multi-faceted palace from bird's-eye and interior perspectives, emphasizing the mandala's geometric symmetry and symbolic flames to represent transformative wisdom.[34]Role in Rituals and Worship

In Shingon Buddhism, the Goma fire offering ritual prominently features the invocation of Wisdom Kings, particularly Acala (Fudō Myōō), to purify obstacles and negative karma. Practitioners chant Acala's mantra, "Namaḥ samanta vajrāṇāṃ," while offering wooden tablets inscribed with prayers into the consecrated fire, symbolizing the burning away of defilements and the transmission of aspirations to the divine.[35][36] This rite, rooted in esoteric traditions, is performed daily or during special ceremonies at temples like Naritasan Shinshō-ji, where the flames represent enlightened wisdom consuming ignorance.[37] Wisdom Kings also play a protective role in household devotion, with small statues and amulets of Acala placed in Japanese homes to ward off misfortune and safeguard family members, especially children from illness or malevolent spirits. These talismans, often distributed during temple festivals, embody Acala's immovable resolve as a guardian deity, invoking his fierce compassion to shield the vulnerable.[38] In esoteric practice, such items are consecrated through rituals to amplify their efficacy against external threats. Within Vajrayana sadhana, meditators engage in visualization techniques where they embody the form and qualities of Wisdom Kings to subdue inner delusions and afflictions. By generating the deity's wrathful aspect in meditation—such as Acala's sword-wielding stance—practitioners cultivate transformative wisdom, conquering ego-clinging and emotional disturbances as a path to enlightenment.[39] This immersive practice, guided by tantric texts, integrates mantra recitation and mudra to dissolve dualistic perceptions. In Chinese Buddhist traditions, the Shuilu (Water-Land) assembly employs the Ten Wisdom Kings in elaborate chanting sessions aimed at ancestral salvation and the liberation of suffering beings from realms like the hungry ghost domain. Monks recite sutras and dharanis invoking these kings during the multi-day rite, offering feasts and visualizations to guide souls toward rebirth in pure lands, emphasizing universal compassion.[40][41]References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%E6%B0%B4%E9%99%86%E7%94%BB%E5%AE%9D%E5%AE%81%E5%AF%BA_%E6%97%A0%E8%83%BD%E8%83%9C%E6%98%8E%E7%8E%8B.jpg

![Liao dynasty (916-1125) statutes of four of the Eight Wisdom Kings and an attendant warrior at Datong Guanyin-tang[zh], Datong, Shanxi, China. From left to right: Padanakṣipa, Acala, Yamāntaka, Aparājita](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/76/%E5%A4%A7%E5%90%8C%E8%A7%82%E9%9F%B3%E5%A0%82%E6%AE%BF%E5%B7%A6%E4%BE%A7%E8%BE%BD%E4%BB%A3%E4%BA%94%E5%B0%8A%E9%80%A0%E5%83%8F.jpg/250px-%E5%A4%A7%E5%90%8C%E8%A7%82%E9%9F%B3%E5%A0%82%E6%AE%BF%E5%B7%A6%E4%BE%A7%E8%BE%BD%E4%BB%A3%E4%BA%94%E5%B0%8A%E9%80%A0%E5%83%8F.jpg)

![Liao dynasty (916-1125) statutes of four of the Eight Wisdom Kings and an attendant warrior at Datong Guanyin-tang[zh], Datong, Shanxi, China. From left to right: Hayagrīva, Vajrahāsa, Mahācakra, Mahāmāyūrī](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8e/%E5%A4%A7%E5%90%8C%E8%A7%82%E9%9F%B3%E5%A0%82%E6%AE%BF%E5%8F%B3%E4%BE%A7%E4%BA%94%E5%B0%8A%E8%BE%BD%E4%BB%A3%E9%80%A0%E5%83%8F.jpg/250px-%E5%A4%A7%E5%90%8C%E8%A7%82%E9%9F%B3%E5%A0%82%E6%AE%BF%E5%8F%B3%E4%BE%A7%E4%BA%94%E5%B0%8A%E8%BE%BD%E4%BB%A3%E9%80%A0%E5%83%8F.jpg)

![Yuan dynasty (1271-1368) figure of a Wisdom King, one out of a pair flanking a central figure of Guanyin, at Fusheng Temple[zh] in Yuncheng, Shanxi, China](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6c/%E5%B7%A6%E4%BE%A7%E6%98%8E%E7%8E%8B.jpg/250px-%E5%B7%A6%E4%BE%A7%E6%98%8E%E7%8E%8B.jpg)

![Yuan dynasty (1271-1368) figure of a Wisdom King, one out of a pair flanking a central figure of Guanyin, at Fusheng Temple[zh] in Yuncheng, Shanxi, China](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c4/%E5%8F%B3%E4%BE%A7%E6%98%8E%E7%8E%8B%E5%85%A8%E8%BA%AB%E7%85%A7.jpg/250px-%E5%8F%B3%E4%BE%A7%E6%98%8E%E7%8E%8B%E5%85%A8%E8%BA%AB%E7%85%A7.jpg)