Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning

View on Wikipedia

Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC /ˈeɪtʃˌvæk/) systems use advanced technologies to regulate temperature, humidity, and indoor air quality in residential, commercial, and industrial buildings, and in enclosed vehicles. Its goal is to provide thermal comfort and remove contaminants from the air. HVAC system design is a subdiscipline of mechanical engineering, based on the principles of thermodynamics, fluid mechanics, and heat transfer. Modern HVAC designs focus on energy efficiency and sustainability, especially with the rising demand for green building solutions. In modern construction, MEP (Mechanical, Electrical, and Plumbing) engineers integrate HVAC systems with energy modeling techniques to optimize system performance and reduce operational costs. "Refrigeration" is sometimes added to the field's abbreviation as HVAC&R or HVACR, or "ventilation" is dropped, as in HACR (as in the designation of HACR-rated circuit breakers).

HVAC is an important part of residential structures such as single family homes, apartment buildings, hotels, and senior living facilities; medium to large industrial and office buildings such as skyscrapers and hospitals; vehicles such as cars, trains, airplanes, ships and submarines; and in marine environments, where safe and healthy building conditions are regulated with respect to temperature and humidity, using fresh air from outdoors.

Ventilating or ventilation (the "V" in HVAC) is the process of exchanging or replacing air in any space to provide high indoor air quality which involves temperature control, oxygen replenishment, and removal of moisture, odors, smoke, heat, dust, airborne bacteria, carbon dioxide, and other gases. Ventilation removes unpleasant smells and excessive moisture, introduces outside air, and keeps interior air circulating. Building ventilation methods are categorized as mechanical (forced) or natural.[1]

Overview

[edit]The three major functions of heating, ventilation, and air conditioning are interrelated, especially with the need to provide thermal comfort and acceptable indoor air quality within reasonable installation, operation, and maintenance costs. HVAC systems can be used in both domestic and commercial environments. HVAC systems can provide ventilation, and maintain pressure relationships between spaces. The means of air delivery and removal from spaces is known as room air distribution.[2]

Individual systems

[edit]In modern buildings, the design, installation, and control systems of these functions are integrated into one or more HVAC systems. For very small buildings, contractors normally estimate the capacity and type of system needed and then design the system, selecting the appropriate refrigerant and various components needed. For larger buildings, building service designers, mechanical engineers, or building services engineers analyze, design, and specify the HVAC systems. Specialty mechanical contractors and suppliers then fabricate, install and commission the systems. Building permits and code-compliance inspections of the installations are normally required for all sizes of buildings.[3][4]

District networks

[edit]Although HVAC is executed in individual buildings or other enclosed spaces (like NORAD's underground headquarters), the equipment involved is in some cases an extension of a larger district heating (DH) or district cooling (DC) network, or a combined DHC network. In such cases, the operating and maintenance aspects are simplified and metering becomes necessary to bill for the energy that is consumed, and in some cases energy that is returned to the larger system. For example, at a given time one building may be utilizing chilled water for air conditioning and the warm water it returns may be used in another building for heating, or for the overall heating-portion of the DHC network (likely with energy added to boost the temperature).[5][6][7]

Basing HVAC on a larger network helps provide an economy of scale that is often not possible for individual buildings, for utilizing renewable energy sources such as solar heat,[8][9][10] winter's cold,[11][12] the cooling potential in some places of lakes or seawater for free cooling, and the enabling function of seasonal thermal energy storage. Utilizing natural sources for HVAC can significantly benefit the environment and promote awareness of alternative methods.

History

[edit]HVAC is based on inventions and discoveries made by Nikolay Lvov, Michael Faraday, Rolla C. Carpenter, Willis Carrier, Edwin Ruud, Reuben Trane, James Joule, William Rankine, Sadi Carnot, Alice Parker and many others.[13]

Multiple inventions within this time frame preceded the beginnings of the first comfort air conditioning system, which was designed in 1902 by Alfred Wolff (Cooper, 2003) for the New York Stock Exchange, while Willis Carrier equipped the Sacketts-Wilhems Printing Company with the process AC unit the same year. Coyne College was the first school to offer HVAC training in 1899.[14] The first residential AC was installed by 1914, and by the 1950s there was "widespread adoption of residential AC".[15]

The invention of the components of HVAC systems went hand-in-hand with the Industrial Revolution, and new methods of modernization, higher efficiency, and system control are constantly being introduced by companies and inventors worldwide.

Heating

[edit]Heaters are appliances whose purpose is to generate heat (i.e. warmth) for the building. This can be done via central heating. Such a system contains a boiler, furnace, or heat pump to heat water, steam, or air in a central location such as a furnace room in a home, or a mechanical room in a large building. The heat can be transferred by convection, conduction, or radiation. Space heaters are used to heat single rooms and only consist of a single unit.

Generation

[edit]

Heaters exist for various types of fuel, including solid fuels, liquids, and gases. Another type of heat source is electricity, normally heating ribbons composed of high resistance wire (see Nichrome). This principle is also used for baseboard heaters and portable heaters. Electrical heaters are often used as backup or supplemental heat for heat pump systems.[citation needed]

The heat pump gained popularity in the 1950s in Japan and the United States.[16] Heat pumps can extract heat from various sources, such as environmental air, exhaust air from a building, or from the ground. Heat pumps transfer heat from outside the structure into the air inside. Initially, heat pump HVAC systems were only used in moderate climates, but with improvements in low temperature operation and reduced loads due to more efficient homes, they are increasing in popularity in cooler climates. They can also operate in reverse to cool an interior.[17][18]

Distribution

[edit]Water/steam

[edit]In the case of heated water or steam, piping is used to transport the heat to the rooms. Most modern hot water boiler heating systems have a circulator, which is a pump, to move hot water through the distribution system (as opposed to older gravity-fed systems). The heat can be transferred to the surrounding air using radiators, hot water coils (hydro-air), or other heat exchangers. The radiators may be mounted on walls or installed within the floor to produce floor heat.[citation needed]

The use of water as the heat transfer medium is known as hydronics. The heated water can also supply an auxiliary heat exchanger to supply hot water for bathing and washing.[19][3]

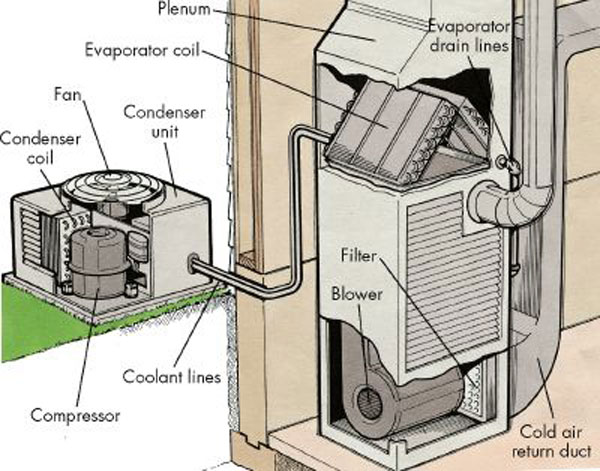

Air

[edit]Warm air systems distribute the heated air through ductwork systems of supply and return air through metal or fiberglass ducts. Many systems use the same ducts to distribute air cooled by an evaporator coil for air conditioning. The air supply is normally filtered through air filters[dubious – discuss] to remove dust and pollen particles.[20]

Dangers

[edit]The use of furnaces, space heaters, and boilers as a method of indoor heating could result in incomplete combustion and the emission of carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, formaldehyde, volatile organic compounds, and other combustion byproducts. Incomplete combustion occurs when there is insufficient oxygen; the inputs are fuels containing various contaminants and the outputs are harmful byproducts, most dangerously carbon monoxide, which is a tasteless and odorless gas with serious adverse health effects.[21]

Without proper ventilation, carbon monoxide can be lethal at concentrations of 1000 ppm (0.1%). However, at several hundred ppm, carbon monoxide exposure induces headaches, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting. Carbon monoxide binds with hemoglobin in the blood, forming carboxyhemoglobin, reducing the blood's ability to transport oxygen. The primary health concerns associated with carbon monoxide exposure are its cardiovascular and neurobehavioral effects. Carbon monoxide can cause atherosclerosis (the hardening of arteries) and can also trigger heart attacks. Neurologically, carbon monoxide exposure reduces hand to eye coordination, vigilance, and continuous performance. It can also affect time discrimination.[22]

Ventilation

[edit]Ventilation is the process of changing or replacing air in any space to control the temperature or remove any combination of moisture, odors, smoke, heat, dust, airborne bacteria, or carbon dioxide, and to replenish oxygen. It plays a critical role in maintaining a healthy indoor environment by preventing the buildup of harmful pollutants and ensuring the circulation of fresh air. Different methods, such as natural ventilation through windows and mechanical ventilation systems, can be used depending on the building design and air quality needs. Ventilation often refers to the intentional delivery of the outside air to the building indoor space. It is one of the most important factors for maintaining acceptable indoor air quality in buildings.

Although ventilation plays a key role in indoor air quality, it may not be sufficient on its own.[23] A clear understanding of both indoor and outdoor air quality parameters is needed to improve the performance of ventilation in terms of ...[24] In scenarios where outdoor pollution would deteriorate indoor air quality, other treatment devices such as filtration may also be necessary.[25]

Methods for ventilating a building may be divided into mechanical/forced and natural types.[26]

Mechanical or forced

[edit]

Mechanical, or forced, ventilation is provided by an air handler (AHU) and used to control indoor air quality. Excess humidity, odors, and contaminants can often be controlled via dilution or replacement with outside air. However, in humid climates more energy is required to remove excess moisture from ventilation air.

Kitchens and bathrooms typically have mechanical exhausts to control odors and sometimes humidity. Factors in the design of such systems include the flow rate (which is a function of the fan speed and exhaust vent size) and noise level. Direct drive fans are available for many applications and can reduce maintenance needs.

In summer, ceiling fans and table/floor fans circulate air within a room for the purpose of reducing the perceived temperature by increasing evaporation of perspiration on the skin of the occupants. Because hot air rises, ceiling fans may be used to keep a room warmer in the winter by circulating the warm stratified air from the ceiling to the floor.

Passive

[edit]

Natural ventilation is the ventilation of a building with outside air without using fans or other mechanical systems. It can be via operable windows, louvers, or trickle vents when spaces are small and the architecture permits. ASHRAE defined Natural ventilation as the flow of air through open windows, doors, grilles, and other planned building envelope penetrations, and as being driven by natural and/or artificially produced pressure differentials.[1]

Natural ventilation strategies also include cross ventilation, which relies on wind pressure differences on opposite sides of a building. By strategically placing openings, such as windows or vents, on opposing walls, air is channeled through the space to enhance cooling and ventilation. Cross ventilation is most effective when there are clear, unobstructed paths for airflow within the building.

In more complex schemes, warm air is allowed to rise and flow out high building openings to the outside (stack effect), causing cool outside air to be drawn into low building openings. Natural ventilation schemes can use very little energy, but care must be taken to ensure comfort. In warm or humid climates, maintaining thermal comfort solely via natural ventilation might not be possible. Air conditioning systems are used, either as backups or supplements. Air-side economizers also use outside air to condition spaces, but do so using fans, ducts, dampers, and control systems to introduce and distribute cool outdoor air when appropriate.

An important component of natural ventilation is air change rate or air changes per hour: the hourly rate of ventilation divided by the volume of the space. For example, six air changes per hour means an amount of new air, equal to the volume of the space, is added every ten minutes. For human comfort, a minimum of four air changes per hour is typical, though warehouses might have only two. Too high of an air change rate may be uncomfortable, akin to a wind tunnel which has thousands of changes per hour. The highest air change rates are for crowded spaces, bars, night clubs, commercial kitchens at around 30 to 50 air changes per hour.[27]

Room pressure can be either positive or negative with respect to outside the room. Positive pressure occurs when there is more air being supplied than exhausted, and is common to reduce the infiltration of outside contaminants.[28]

Airborne diseases

[edit]Natural ventilation [29] is a key factor in reducing the spread of airborne illnesses such as tuberculosis, the common cold, influenza, meningitis or COVID-19. Opening doors and windows are good ways to maximize natural ventilation, which would make the risk of airborne contagion much lower than with costly and maintenance-requiring mechanical systems. Old-fashioned clinical areas with high ceilings and large windows provide the greatest protection. Natural ventilation costs little and is maintenance free, and is particularly suited to limited-resource settings and tropical climates, where the burden of TB and institutional TB transmission is highest. In settings where respiratory isolation is difficult and climate permits, windows and doors should be opened to reduce the risk of airborne contagion. Natural ventilation requires little maintenance and is inexpensive.[30]

Natural ventilation is not practical in much of the infrastructure because of climate. This means that the facilities need to have effective mechanical ventilation systems and or use Ceiling Level UV or FAR UV ventilation systems.

Ventilation is measured in terms of Air Changes Per Hour (ACH). As of 2023, the CDC recommends that all spaces have a minimum of 5 ACH.[31] For hospital rooms with airborne contagions the CDC recommends a minimum of 12 ACH.[32] The challenges in facility ventilation are public unawareness,[33][34] ineffective government oversight, poor building codes that are based on comfort levels, poor system operations, poor maintenance, and lack of transparency.[35]

UVC or Ultraviolet Germicidal Irradiation is a function used in modern air conditioners which reduces airborne viruses, bacteria, and fungi, through the use of a built-in LED UV light that emits a gentle glow across the evaporator. As the cross-flow fan circulates the room air, any viruses are guided through the sterilization module’s irradiation range, rendering them instantly inactive.[36]

Air conditioning

[edit]An air conditioning system, or a standalone air conditioner, provides cooling and/or humidity control for all or part of a building. Air conditioned buildings often have sealed windows, because open windows would work against the system intended to maintain constant indoor air conditions. Outside, fresh air is generally drawn into the system by a vent into a mix air chamber for mixing with the space return air. Then the mixture air enters an indoor or outdoor heat exchanger section where the air is to be cooled down, then be guided to the space creating positive air pressure. The percentage of return air made up of fresh air can usually be manipulated by adjusting the opening of this vent. Typical fresh air intake is about 10% of the total supply air.[citation needed]

Air conditioning and refrigeration are provided through the removal of heat. Heat can be removed through radiation, convection, or conduction. The heat transfer medium is a refrigeration system, such as water, air, ice, and chemicals are referred to as refrigerants. A refrigerant is employed either in a heat pump system in which a compressor is used to drive thermodynamic refrigeration cycle, or in a free cooling system that uses pumps to circulate a cool refrigerant (typically water or a glycol mix).

It is imperative that the air conditioning horsepower is sufficient for the area being cooled. Underpowered air conditioning systems will lead to power wastage and inefficient usage. Adequate horsepower is required for any air conditioner installed.

Refrigeration cycle

[edit]

The refrigeration cycle uses four essential elements to cool, which are compressor, condenser, metering device, and evaporator.

- At the inlet of a compressor, the refrigerant inside the system is in a low pressure, low temperature, gaseous state. The compressor pumps the refrigerant gas up to high pressure and temperature.

- From there it enters a heat exchanger (sometimes called a condensing coil or condenser) where it loses heat to the outside, cools, and condenses into its liquid phase.

- An expansion valve (also called metering device) regulates the refrigerant liquid to flow at the proper rate.

- The liquid refrigerant is returned to another heat exchanger where it is allowed to evaporate, hence the heat exchanger is often called an evaporating coil or evaporator. As the liquid refrigerant evaporates it absorbs heat from the inside air, returns to the compressor, and repeats the cycle. In the process, heat is absorbed from indoors and transferred outdoors, resulting in cooling of the building.

In variable climates, the system may include a reversing valve that switches from heating in winter to cooling in summer. By reversing the flow of refrigerant, the heat pump refrigeration cycle is changed from cooling to heating or vice versa. This allows a facility to be heated and cooled by a single piece of equipment by the same means, and with the same hardware.

Free cooling

[edit]Free cooling systems can have very high efficiencies, and are sometimes combined with seasonal thermal energy storage so that the cold of winter can be used for summer air conditioning. Common storage mediums are deep aquifers or a natural underground rock mass accessed via a cluster of small-diameter, heat-exchanger-equipped boreholes. Some systems with small storages are hybrids, using free cooling early in the cooling season, and later employing a heat pump to chill the circulation coming from the storage. The heat pump is added-in because the storage acts as a heat sink when the system is in cooling (as opposed to charging) mode, causing the temperature to gradually increase during the cooling season.

Some systems include an "economizer mode", which is sometimes called a "free-cooling mode". When economizing, the control system will open (fully or partially) the outside air damper and close (fully or partially) the return air damper. This will cause fresh, outside air to be supplied to the system. When the outside air is cooler than the demanded cool air, this will allow the demand to be met without using the mechanical supply of cooling (typically chilled water or a direct expansion "DX" unit), thus saving energy. The control system can compare the temperature of the outside air vs. return air, or it can compare the enthalpy of the air, as is frequently done in climates where humidity is more of an issue. In both cases, the outside air must be less energetic than the return air for the system to enter the economizer mode.

Packaged split system

[edit]Central, "all-air" air-conditioning systems (or package systems) with a combined outdoor condenser/evaporator unit are often installed in North American residences, offices, and public buildings, but are difficult to retrofit (install in a building that was not designed to receive it) because of the bulky air ducts required.[37] (Minisplit ductless systems are used in these situations.) Outside of North America, packaged systems are only used in limited applications involving large indoor space such as stadiums, theatres or exhibition halls.

An alternative to packaged systems is the use of separate indoor and outdoor coils in split systems. Split systems are preferred and widely used worldwide except in North America. In North America, split systems are most often seen in residential applications, but they are gaining popularity in small commercial buildings. Split systems are used where ductwork is not feasible or where the space conditioning efficiency is of prime concern.[38] The benefits of ductless air conditioning systems include easy installation, no ductwork, greater zonal control, flexibility of control, and quiet operation.[39] In space conditioning, the duct losses can account for 30% of energy consumption.[40] The use of minisplits can result in energy savings in space conditioning as there are no losses associated with ducting.

With the split system, the evaporator coil is connected to a remote condenser unit using refrigerant piping between an indoor and outdoor unit instead of ducting air directly from the outdoor unit. Indoor units with directional vents mount onto walls, suspended from ceilings, or fit into the ceiling. Other indoor units mount inside the ceiling cavity so that short lengths of duct handle air from the indoor unit to vents or diffusers around the rooms.

Split systems are more efficient and the footprint is typically smaller than the package systems. On the other hand, package systems tend to have a slightly lower indoor noise level compared to split systems since the fan motor is located outside.

Dehumidification

[edit]Dehumidification (air drying) in an air conditioning system is provided by the evaporator. Since the evaporator operates at a temperature below the dew point, moisture in the air condenses on the evaporator coil tubes. This moisture is collected at the bottom of the evaporator in a pan and removed by piping to a central drain or onto the ground outside.

A dehumidifier is an air-conditioner-like device that controls the humidity of a room or building. It is often employed in basements that have a higher relative humidity because of their lower temperature (and propensity for damp floors and walls). In food retailing establishments, large open chiller cabinets are highly effective at dehumidifying the internal air. Conversely, a humidifier increases the humidity of a building.

The HVAC components that dehumidify the ventilation air deserve careful attention because outdoor air constitutes most of the annual humidity load for nearly all buildings.[41]

Humidification

[edit]A humidifier is a household appliance or device designed to increase the moisture level in the air within a room or an enclosed space. It achieves this by emitting water droplets or steam into the surrounding air, thereby raising the humidity.

In the home, point-of-use humidifiers are commonly used to humidify a single room, while whole-house or furnace humidifiers, which connect to a home's HVAC system, provide humidity to the entire house. Medical ventilators often include humidifiers for increased patient comfort. Large humidifiers are used in commercial, institutional, or industrial contexts, often as part of a larger HVAC system.

Maintenance

[edit]All modern air conditioning systems, even small window package units, are equipped with internal air filters.[citation needed] These are generally of a lightweight gauze-like material, and must be replaced or washed as conditions warrant. For example, a building in a high dust environment, or a home with furry pets, will need to have the filters changed more often than buildings without these dirt loads. Failure to replace these filters as needed will contribute to a lower heat exchange rate, resulting in wasted energy, shortened equipment life, and higher energy bills; low air flow can result in iced-over evaporator coils, which can completely stop airflow. Additionally, very dirty or plugged filters can cause overheating during a heating cycle, which can result in damage to the system or even fire.

Because an air conditioner moves heat between the indoor coil and the outdoor coil, both must be kept clean. This means that, in addition to replacing the air filter at the evaporator coil, it is also necessary to regularly clean the condenser coil. Failure to keep the condenser clean will eventually result in harm to the compressor because the condenser coil is responsible for discharging both the indoor heat (as picked up by the evaporator) and the heat generated by the electric motor driving the compressor.[42]

Energy efficiency

[edit]HVAC systems play a key role in improving the energy efficiency of buildings, as the building sector accounts for one of the highest shares of global energy consumption.[43] Since the 1980s, HVAC equipment manufacturers have focused on improving system efficiency. Initially, these efforts were driven by rising energy costs, but in recent years, environmental sustainability and stricter efficiency regulations have become the primary motivators. Additionally, improving HVAC system efficiency can enhance indoor air quality, which may lead to better occupant health, comfort, and productivity.[44] In the US, the EPA has imposed tighter restrictions over the years. There are several methods for making HVAC systems more efficient.

Heating energy

[edit]In the past, water heating was more efficient for heating buildings and was the standard in the United States. Today, forced air systems can double for air conditioning and are more popular.

Some benefits of forced air systems, which are now widely used in churches, schools, and high-end residences, are

- Better air conditioning effects

- Energy savings of up to 15–20%

- Even conditioning[citation needed]

A drawback is the installation cost, which can be slightly higher than traditional HVAC systems.

Energy efficiency can be improved even more in central heating systems by introducing zoned heating. This allows a more granular application of heat, similar to non-central heating systems. Zones are controlled by multiple thermostats. In water heating systems the thermostats control zone valves, and in forced air systems they control zone dampers inside the vents which selectively block the flow of air. In this case, the control system is very critical to maintaining a proper temperature.

Forecasting is another method of controlling building heating by calculating the demand for heating energy that should be supplied to the building in each time unit.

Ground source heat pump

[edit]Ground source, or geothermal, heat pumps are similar to ordinary heat pumps, but instead of transferring heat to or from outside air, they rely on the stable, even temperature of the earth to provide heating and air conditioning. Many regions experience seasonal temperature extremes, which would require large-capacity heating and cooling equipment to heat or cool buildings. For example, a conventional heat pump system used to heat a building in Montana's −57 °C (−70 °F) low temperature or cool a building in the highest temperature ever recorded in the US—57 °C (134 °F) in Death Valley, California, in 1913 would require a large amount of energy due to the extreme difference between inside and outside air temperatures. A metre below the earth's surface, however, the ground remains at a relatively constant temperature. Utilizing this large source of relatively moderate temperature earth, a heating or cooling system's capacity can often be significantly reduced. Although ground temperatures vary according to latitude, at 1.8 metres (6 ft) underground, temperatures generally only range from 7 to 24 °C (45 to 75 °F).

Solar air conditioning

[edit]Photovoltaic solar panels offer a new way to potentially decrease the operating cost of air conditioning. Traditional air conditioners run using alternating current, and hence, any direct-current solar power needs to be inverted to be compatible with these units. New variable-speed DC-motor units allow solar power to more easily run them since this conversion is unnecessary, and since the motors are tolerant of voltage fluctuations associated with variance in supplied solar power (e.g., due to cloud cover).

Ventilation energy recovery

[edit]Energy recovery systems sometimes utilize heat recovery ventilation or energy recovery ventilation systems that employ heat exchangers or enthalpy wheels to recover sensible or latent heat from exhausted air. This is done by transfer of energy from the stale air inside the home to the incoming fresh air from outside.

Air conditioning energy

[edit]The performance of vapor compression refrigeration cycles is limited by thermodynamics.[45] These air conditioning and heat pump devices move heat rather than convert it from one form to another, so thermal efficiencies do not appropriately describe the performance of these devices. The Coefficient of performance (COP) measures performance, but this dimensionless measure has not been adopted. Instead, the Energy Efficiency Ratio (EER) has traditionally been used to characterize the performance of many HVAC systems. EER is the Energy Efficiency Ratio based on a 35 °C (95 °F) outdoor temperature. To more accurately describe the performance of air conditioning equipment over a typical cooling season a modified version of the EER, the Seasonal Energy Efficiency Ratio (SEER), or in Europe the ESEER, is used. SEER ratings are based on seasonal temperature averages instead of a constant 35 °C (95 °F) outdoor temperature. The current industry minimum SEER rating is 14 SEER. Engineers have pointed out some areas where efficiency of the existing hardware could be improved. For example, the fan blades used to move the air are usually stamped from sheet metal, an economical method of manufacture, but as a result they are not aerodynamically efficient. A well-designed blade could reduce the electrical power required to move the air by a third.[46]

Demand-controlled kitchen ventilation

[edit]Demand-controlled kitchen ventilation (DCKV) is a building controls approach to controlling the volume of kitchen exhaust and supply air in response to the actual cooking loads in a commercial kitchen. Traditional commercial kitchen ventilation systems operate at 100% fan speed independent of the volume of cooking activity and DCKV technology changes that to provide significant fan energy and conditioned air savings. By deploying smart sensing technology, both the exhaust and supply fans can be controlled to capitalize on the affinity laws for motor energy savings, reduce makeup air heating and cooling energy, increasing safety, and reducing ambient kitchen noise levels.[47]

Air filtration and cleaning

[edit]

Air cleaning and filtration removes particles, contaminants, vapors and gases from the air. The filtered and cleaned air then is used in heating, ventilation, and air conditioning. Air cleaning and filtration should be taken in account when protecting our building environments.[48] If present, contaminants can come out from the HVAC systems if not removed or filtered properly.

Clean air delivery rate (CADR) is the amount of clean air an air cleaner provides to a room or space. When determining CADR, the amount of airflow in a space is taken into account. For example, an air cleaner with a flow rate of 30 cubic metres (1,000 cu ft) per minute and an efficiency of 50% has a CADR of 15 cubic metres (500 cu ft) per minute. Along with CADR, filtration performance is very important when it comes to the air in our indoor environment. This depends on the size of the particle or fiber, the filter packing density and depth, and the airflow rate.[48]

Industry and standards

[edit]The HVAC industry is a worldwide enterprise, with roles including operation and maintenance, system design and construction, equipment manufacturing and sales, and in education and research. The HVAC industry was historically regulated by the manufacturers of HVAC equipment, but regulating and standards organizations such as HARDI (Heating, Air-conditioning and Refrigeration Distributors International), ASHRAE, SMACNA, ACCA (Air Conditioning Contractors of America), Uniform Mechanical Code, International Mechanical Code, and AMCA have been established to support the industry and encourage high standards and achievement. (UL as an omnibus agency is not specific to the HVAC industry.)

The starting point in carrying out an estimate both for cooling and heating depends on the exterior climate and interior specified conditions. However, before taking up the heat load calculation, it is necessary to find fresh air requirements for each area in detail, as pressurization is an important consideration.

International

[edit]ISO 16813:2006 is one of the ISO building environment standards.[49] It establishes the general principles of building environment design. It takes into account the need to provide a healthy indoor environment for the occupants as well as the need to protect the environment for future generations and promote collaboration among the various parties involved in building environmental design for sustainability. ISO16813 is applicable to new construction and the retrofit of existing buildings.[50]

The building environmental design standard aims to:[50]

- provide the constraints concerning sustainability issues from the initial stage of the design process, with building and plant life cycle to be considered together with owning and operating costs from the beginning of the design process;

- assess the proposed design with rational criteria for indoor air quality, thermal comfort, acoustical comfort, visual comfort, energy efficiency, and HVAC system controls at every stage of the design process;

- iterate decisions and evaluations of the design throughout the design process.

United States

[edit]Licensing

[edit]In the United States, federal licensure is generally handled by EPA certified (for installation and service of HVAC devices).

Many U.S. states have licensing for boiler operation. Some of these are listed as follows:

- Arkansas[51]

- Georgia[52]

- Michigan[53]

- Minnesota[54]

- Montana[55]

- New Jersey[56]

- North Dakota[57]

- Ohio[58]

- Oklahoma[59]

- Oregon[60]

Finally, some U.S. cities may have additional labor laws that apply to HVAC professionals.

Societies

[edit]Many HVAC engineers are members of the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE). ASHRAE regularly organizes two annual technical committees and publishes recognized standards for HVAC design, which are updated every four years.[61]

Another popular society is AHRI, which provides regular information on new refrigeration technology, and publishes relevant standards and codes.

Codes

[edit]Codes such as the UMC and IMC do include much detail on installation requirements, however. Other useful reference materials include items from SMACNA, ACGIH, and technical trade journals.

American design standards are legislated in the Uniform Mechanical Code or International Mechanical Code. In certain states, counties, or cities, either of these codes may be adopted and amended via various legislative processes. These codes are updated and published by the International Association of Plumbing and Mechanical Officials (IAPMO) or the International Code Council (ICC) respectively, on a 3-year code development cycle. Typically, local building permit departments are charged with enforcement of these standards on private and certain public properties.

Technicians

[edit]| Occupation | |

|---|---|

Occupation type | Vocational |

Activity sectors | Construction |

| Description | |

Education required | Apprenticeship |

Related jobs | Carpenter, electrician, plumber, welder |

An HVAC technician is a tradesman who specializes in heating, ventilation, air conditioning, and refrigeration. HVAC technicians in the US can receive training through formal training institutions, where most earn associate degrees. Training for HVAC technicians includes classroom lectures and hands-on tasks, and can be followed by an apprenticeship wherein the recent graduate works alongside a professional HVAC technician for a temporary period.[62] HVAC techs who have been trained can also be certified in areas such as air conditioning, heat pumps, gas heating, and commercial refrigeration.

United Kingdom

[edit]The Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers is a body that covers the essential Service (systems architecture) that allow buildings to operate. It includes the electrotechnical, heating, ventilating, air conditioning, refrigeration and plumbing industries. To train as a building services engineer, the academic requirements are GCSEs (A-C) / Standard Grades (1-3) in Maths and Science, which are important in measurements, planning and theory. Employers will often want a degree in a branch of engineering, such as building environment engineering, electrical engineering or mechanical engineering. To become a full member of CIBSE, and so also to be registered by the Engineering Council UK as a chartered engineer, engineers must also attain an Honours Degree and a master's degree in a relevant engineering subject.[citation needed] CIBSE publishes several guides to HVAC design relevant to the UK market, and also the Republic of Ireland, Australia, New Zealand and Hong Kong. These guides include various recommended design criteria and standards, some of which are cited within the UK building regulations, and therefore form a legislative requirement for major building services works. The main guides are:

- Guide A: Environmental Design

- Guide B: Heating, Ventilating, Air Conditioning and Refrigeration

- Guide C: Reference Data

- Guide D: Transportation systems in Buildings

- Guide E: Fire Safety Engineering

- Guide F: Energy Efficiency in Buildings

- Guide G: Public Health Engineering

- Guide H: Building Control Systems

- Guide J: Weather, Solar and Illuminance Data

- Guide K: Electricity in Buildings

- Guide L: Sustainability

- Guide M: Maintenance Engineering and Management

Within the construction sector, it is the job of the building services engineer to design and oversee the installation and maintenance of the essential services such as gas, electricity, water, heating and lighting, as well as many others. These all help to make buildings comfortable and healthy places to live and work in. Building Services is part of a sector that has over 51,000 businesses and employs represents 2–3% of the GDP.

Australia

[edit]The Air Conditioning and Mechanical Contractors Association of Australia (AMCA), Australian Institute of Refrigeration, Air Conditioning and Heating (AIRAH), Australian Refrigeration Mechanical Association and CIBSE are responsible.

Asia

[edit]Asian architectural temperature-control have different priorities than European methods. For example, Asian heating traditionally focuses on maintaining temperatures of objects such as the floor or furnishings such as Kotatsu tables and directly warming people, as opposed to the Western focus, in modern periods, on designing air systems.

Philippines

[edit]The Philippine Society of Ventilating, Air Conditioning and Refrigerating Engineers (PSVARE) along with Philippine Society of Mechanical Engineers (PSME) govern on the codes and standards for HVAC / MVAC (MVAC means "mechanical ventilation and air conditioning") in the Philippines.

India

[edit]The Indian Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air Conditioning Engineers (ISHRAE) was established to promote the HVAC industry in India. ISHRAE is an associate of ASHRAE. ISHRAE was founded at New Delhi[63] in 1981 and a chapter was started in Bangalore in 1989. Between 1989 & 1993, ISHRAE chapters were formed in all major cities in India.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Architectural engineering – Engineering discipline of engineering systems of buildings

- Cleanroom – Dust-free room for research or production

- Electric heating – Process in which electrical energy is converted to heat

- Fan coil unit – HVAC device

- Glossary of HVAC terms

- Outdoor wood-fired boiler – Variant of the wood stove

- Radiant cooling – Category of HVAC technologies

- Sick building syndrome – Symptoms of illness attributed to a building

- Ventilation (architecture) – Intentional introduction of outside air into a space

- Windcatcher – Architectural element for creating a draft

- World Refrigeration Day – Annual international event on June 26

References

[edit]- ^ a b Ventilation and Infiltration chapter, Fundamentals volume of the ASHRAE Handbook, ASHRAE, Inc., Atlanta, GA, 2005

- ^ Rock, Ben; Zhu, Yuanxiong (2002). Designer's Guide to Ceiling-Based Air Diffusion. New York: ASHRAE, Inc. ISBN 9781931862110.

- ^ a b CIBSE Guide B: Heating, Ventilating, Air Conditioning and Refrigeration. London: Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers. 2016.

- ^ "Heating and Cooling". U.S. Department of Energy. Retrieved 16 October 2025.

- ^ Rezaie, Behnaz; Rosen, Marc A. (2012). "District heating and cooling: Review of technology and potential enhancements". Applied Energy. 93: 2–10. Bibcode:2012ApEn...93....2R. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2011.04.020.

- ^ Werner S. (2006). ECOHEATCOOL (WP4) Possibilities with more district heating in Europe. Euroheat & Power, Brussels. Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dalin P., Rubenhag A. (2006). ECOHEATCOOL (WP5) Possibilities with more district cooling in Europe, final report from the project. Final Rep. Brussels: Euroheat & Power. Archived 2012-10-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Nielsen, Jan Erik (2014). Solar District Heating Experiences from Denmark. Energy Systems in the Alps - storage and distribution … Energy Platform Workshop 3, Zurich - 13/2 2014

- ^ Wong B., Thornton J. (2013). Integrating Solar & Heat Pumps. Renewable Heat Workshop.

- ^ Pauschinger T. (2012). Solar District Heating with Seasonal Thermal Energy Storage in Germany Archived 2016-10-18 at the Wayback Machine. European Sustainable Energy Week, Brussels. 18–22 June 2012.

- ^ "How Renewable Energy Is Redefining HVAC | AltEnergyMag". www.altenergymag.com. Retrieved 2020-09-29.

- ^ ""Lake Source" Heat Pump System". HVAC-Talk: Heating, Air & Refrigeration Discussion. Archived from the original on 2015-10-03. Retrieved 2020-09-29.

- ^ Swenson, S. Don (1995). HVAC: heating, ventilating, and air conditioning. Homewood, Illinois: American Technical Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8269-0675-5.

- ^ "History of Heating, Air Conditioning & Refrigeration". Coyne College. Archived from the original on August 28, 2016.

- ^ "What is HVAC? A Comprehensive Guide".

- ^ Staffell, Iain; Brett, Dan; Brandon, Nigel; Hawkes, Adam (30 May 2014). "A review of domestic heat pumps".

- ^ Zogg, Martin (May 2008). History of Heat Pumps (Report). Swiss Federal Office of Energy. Retrieved 16 October 2025.

- ^ Cox, Vivian (11 April 2024). "The History of Heat Pumps: Technology Advances to Meet the Cold-Climate Challenge". Regulatory Assistance Project. Retrieved 16 October 2025.

- ^ "Geothermal Hydronic Heating Heat Pumps". STIEBEL ELTRON New Zealand. Retrieved 16 October 2025.

- ^ (Alta.), Edmonton. Edmonton's green home guide : you're gonna love green. OCLC 884861834.

- ^ Bearg, David W. (1993). Indoor Air Quality and HVAC Systems. New York: Lewis Publishers. pp. 107–112.

- ^ Dianat, I.; Nazari, I. "Characteristic of unintentional carbon monoxide poisoning in Northwest Iran-Tabriz". International Journal of Injury Control and Promotion. Retrieved 2011-11-15.

- ^ ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 62.1, Ventilation for Acceptable Indoor Air Quality, ASHRAE, Inc., Atlanta, GA, US

- ^ Belias, Evangelos; Licina, Dusan (2024). "European residential ventilation: Investigating the impact on health and energy demand". Energy and Buildings. 304 113839. Bibcode:2024EneBu.30413839B. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2023.113839.

- ^ Belias, Evangelos; Licina, Dusan (2022). "Outdoor PM2. 5 air filtration: optimising indoor air quality and energy". Buildings & Cities. 3 (1): 186–203. doi:10.5334/bc.153.

- ^ Ventilation and Infiltration chapter, Fundamentals volume of the ASHRAE Handbook, ASHRAE, Inc., Atlanta, Georgia, 2005

- ^ "Air Change Rates for typical Rooms and Buildings". The Engineering ToolBox. Retrieved 2012-12-12.

- ^ Bell, Geoffrey. "Room Air Change Rate". A Design Guide for Energy-Efficient Research Laboratories. Archived from the original on 2011-11-17. Retrieved 2011-11-15.

- ^ "Natural Ventilation for Infection Control in Health-Care Settings" (PDF). World Health Organization (WHO), 2009. Retrieved 2021-07-05.

- ^ Escombe, A. R.; Oeser, C. C.; Gilman, R. H.; et al. (2007). "Natural ventilation for the prevention of airborne contagion". PLOS Med. 4 (68): e68. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040068. PMC 1808096. PMID 17326709.

- ^ Centers For Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) "Improving Ventilation In Buildings". 11 February 2020.

- ^ Centers For Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) "Guidelines for Environmental Infection Control in Health-Care Facilities". 22 July 2019. Archived from the original on 10 July 2025.

- ^ Dr. Edward A. Nardell Professor of Global Health and Social Medicine, Harvard Medical School "If We're Going to Live With COVID-19, It's Time to Clean Our Indoor Air Properly". Time. February 2022.

- ^ "A Paradigm Shift to Combat Indoor Respiratory Infection - 21st century" (PDF). University of Leeds., Morawska, L, Allen, J, Bahnfleth, W et al. (36 more authors) (2021) A paradigm shift to combat indoor respiratory infection. Science, 372 (6543). pp. 689-691. ISSN 0036-8075

- ^ Video "Building Ventilation What Everyone Should Know". YouTube. 17 June 2022.

- ^ CDC (June 1, 2020). "Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Decontamination and Reuse of Filtering Facepiece Respirators". cdc.gov. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

- ^ "What are Air Ducts? The Homeowner's Guide to HVAC Ductwork". Super Tech. Retrieved 2018-05-14.

- ^ "Ductless Mini-Split Heat Pumps". U.S. Department of Energy.

- ^ "The Pros and Cons of Ductless Mini Split Air Conditioners". Home Reference. 28 July 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ "Ductless Mini-Split Air Conditioners". ENERGY SAVER. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ Moisture Control Guidance for Building Design, Construction and Maintenance. December 2013.

- ^ "Maintaining Your Air Conditioner". U.S. Department of Energy. Retrieved 16 October 2025.

- ^ Chenari, B., Dias Carrilho, J. and Gameiro da Silva, M., 2016. Towards sustainable, energy-efficient and healthy ventilation strategies in buildings: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 59, pp.1426-1447.

- ^ "Sustainable Facilities Tool: HVAC System Overview". sftool.gov. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- ^ "Heating and Air Conditioning". www.nuclear-power.net. Retrieved 2018-02-10.

- ^ Keeping cool and green, The Economist 17 July 2010, p. 83

- ^ "Technology Profile: Demand Control Kitchen Ventilation (DCKV)" (PDF). Retrieved 2018-12-04.

- ^ a b Howard, J (2003), Guidance for Filtration and Air-Cleaning Systems to Protect Building Environments from Airborne Chemical, Biological, or Radiological Attacks, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, doi:10.26616/NIOSHPUB2003136, 2003-136

- ^ ISO. "Building environment standards". www.iso.org. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- ^ a b ISO. "Building environment design—Indoor environment—General principles". Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ^ "010.01.02 Ark. Code R. § 002 - Chapter 13 - Restricted Lifetime License".

- ^ "Boiler Professionals Training and Licensing". Archived from the original on 2023-03-06. Retrieved 2023-03-06.

- ^ "Michigan Boiler Rules".

- ^ "Minn. R. 5225.0550 - EXPERIENCE REQUIREMENTS AND DOCUMENTATION FOR LICENSURE AS AN OPERATING ENGINEER".

- ^ "Subchapter 24.122.5 - Licensing".

- ^ "Chapter 90 - BOILERS, PRESSURE VESSELS, AND REFRIGERATION".

- ^ "Article 33.1-14 - North Dakota Boiler Rules".

- ^ "Ohio Admin. Code 1301:3-5-10 - Boiler operator and steam engineer experience requirements".

- ^ "Subchapter 13 - Licensing of Boiler and Pressure Vessel Service, Repair and/or Installers".

- ^ "Or. Admin. R. 918-225-0691 - Boiler, Pressure Vessel and Pressure Piping Installation, Alteration or Repair Licensing Requirements".

- ^ "ASHRAE Handbook Online". www.ashrae.org. Retrieved 2020-06-17.

- ^ "Heating, Air Conditioning, and Refrigeration Mechanics and Installers : Occupational Outlook Handbook: : U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics". www.bls.gov. Retrieved 2023-06-22.

- ^ "About ISHRAE". ISHRAE. Retrieved 2021-10-11.

Further reading

[edit]- 2020 ASHRAE handbook : heating, ventilating, and air-conditioning systems and equipment. Atlanta, GA: American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers. 2020. ISBN 9781947192522.

- International Mechanical Code 2012. Country Club Hills, IL: International Code Council, Inc. 2011. ISBN 9781609830519.

- Althouse, Andrew D; Turnquist, Carl H (2013). Modern Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Laboratory Manual (17th ed.). Goodheart-Wilcox Publisher. ISBN 9781619602038.

- "The Cost of Cool". NY Times. 19 Oct 2012. Retrieved 16 Oct 2025.

- What is Local Exhaust Ventilation?. Health and Safety Executive. 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2025.

External links

[edit]Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning

View on GrokipediaOverview

Individual systems

Individual systems, also known as local or standalone HVAC units, are self-contained setups that independently manage heating, cooling, and ventilation for a single building or specific zone without relying on external networks.[5] These systems are typically installed within or adjacent to the conditioned space, allowing them to serve individual areas efficiently while maintaining indoor air quality and thermal comfort.[7] Unlike larger-scale alternatives such as district networks that supply multiple buildings from a central plant, individual systems focus on localized operation.[8] Key components of individual HVAC systems include furnaces or boilers for heat generation, air conditioners for cooling, air handlers with fans for circulation, and ductwork for optional air distribution.[5] Furnaces and boilers produce hot air or water, respectively, while air conditioners utilize refrigerant cycles for cooling; air handlers then condition and move the air, with ducts channeling it to rooms if needed.[9] These elements integrate into compact units, enabling straightforward assembly and operation tailored to the building's requirements.[10] Such systems find primary applications in residential settings like single-family homes and apartments, small commercial spaces such as offices and hotels, and retrofit projects in existing structures where minimal disruption is essential.[5] In residential use, they provide zoned comfort without extensive renovations, while in small commercial environments, they support precise temperature control for varied occupancy.[11] Retrofitting with individual units is advantageous for older buildings, as it avoids major infrastructure changes.[12] Advantages of individual systems include simpler installation due to their modular design and enhanced control over specific zones, allowing customized comfort levels.[5] However, disadvantages encompass higher per-unit costs compared to centralized options and potential redundancy in maintenance across multiple units.[5] Representative examples include split air conditioning units, which separate indoor evaporators from outdoor condensers connected by refrigerant lines, ideal for homes without ductwork.[11] Packaged rooftop systems, conversely, house all components in a single outdoor cabinet mounted on building roofs, commonly used in small commercial applications for efficient space utilization.[11]District networks

District networks, also known as district energy systems, represent centralized HVAC infrastructures that supply thermal energy for heating and cooling to multiple buildings via a utility-like distribution system. These networks utilize one or more central plants to generate hot water, steam, or chilled water, which is then delivered through insulated underground pipelines to end-users, enabling efficient shared resource management across large areas. Unlike individual building systems, district networks operate on a utility scale, treating thermal energy as a service similar to electricity or water supply.[8][13] The primary components of district networks include central generation facilities equipped with boilers for heat production, chillers for cooling, and circulation pumps to propel the thermal medium through the system. Insulated pipelines form the backbone of the distribution network, minimizing heat loss while transporting hot or chilled water to buildings, where heat exchangers, meters, and valves enable localized transfer and usage control. These elements allow for flexible operation, such as seasonal switching between heating and cooling modes, and integration with advanced controls for optimized flow.[8][13] District networks find widespread application in high-density urban areas, such as central business districts in cities like New York and Boston, as well as university campuses (e.g., University of Rochester), hospitals, airports, military bases, and industrial zones. In these settings, the systems support diverse thermal demands from mixed-use developments, promoting compact urban growth by reducing the need for on-site equipment in each building. For instance, over 660 such systems operated in the United States as of 2012, and more than 700 as of 2024, serving sectors with consistent year-round energy needs.[8][14][15] A key benefit of district networks is their economies of scale, achieved through large-scale equipment that operates at higher efficiencies—reaching 65% to 80% when combined with cogeneration—compared to the national average of 51% for separate heat and power generation. This leads to reduced greenhouse gas emissions, lower peak electricity demands, and enhanced energy security, as demonstrated by systems that continued operating during events like Hurricane Harvey in 2017. However, challenges include substantial upfront infrastructure costs for pipelines and plants, along with regulatory barriers related to permitting, land use, and emissions management.[8][13][16] Prominent examples include cogeneration plants that simultaneously produce electricity and thermal energy, maximizing resource use; the Texas Medical Center in Houston, for instance, employs a 48 MW combined heat and power system to deliver heating and cooling to 18 healthcare facilities, illustrating the integration potential in institutional clusters. Similarly, District Energy St. Paul in Minnesota combines multiple renewable sources for urban district service, highlighting adaptability to local conditions.[8]History

Early developments

The earliest known systems for heating and ventilation relied on passive architectural designs that harnessed natural elements to maintain comfortable indoor environments. In ancient Rome, the hypocaust system represented a pioneering form of underfloor heating, where hot air from a furnace circulated through channels beneath raised floors supported by brick pillars, warming rooms without direct smoke exposure.[17] This method, dating back to at least the 1st century BCE, was widely used in public baths, villas, and military structures across the Roman Empire, demonstrating an early understanding of convective heat transfer for space conditioning.[18] Similarly, in ancient Persia, wind catchers—known as badgirs—served as effective ventilation devices, consisting of tall towers with multiple openings that captured prevailing winds and directed cooled air into buildings while expelling hot air through downward shafts.[19] These structures, evident from the medieval period around the 14th century CE, provided natural cooling in arid climates by promoting airflow and evaporative effects, often integrated with qanats (underground water channels) for enhanced humidity control.[20] The transition toward mechanical systems began in the 17th and 18th centuries, coinciding with advancements in thermodynamics and engineering that laid the groundwork for powered heating and cooling. Thomas Newcomen's atmospheric steam engine, patented in 1712, marked a significant milestone by demonstrating practical steam generation and pressure management, which later influenced the design of early boilers for building heating applications.[21] Although initially developed for pumping water from mines, its principles enabled the production of reliable hot water and steam systems, shifting reliance from open fires to enclosed, more efficient heat sources.[22] Around the same period, in 1758, Benjamin Franklin conducted experiments on evaporative cooling in collaboration with John Hadley, using volatile liquids like alcohol and ether to lower temperatures dramatically—achieving water freezing on a warm day—thus illustrating the potential for controlled air chilling through rapid evaporation.[23] These investigations, documented in Franklin's correspondence, highlighted the latent heat of vaporization as a mechanism for cooling, predating mechanical refrigeration by over a century.[24] By the 19th century, industrialization accelerated the evolution from passive to mechanical HVAC precursors, driven by urban growth, factory demands, and innovations in heat distribution. Angier March Perkins, an American-born engineer working in London, developed one of the first viable hot water central heating systems in the 1830s, using high-pressure boilers and wrought-iron pipes to circulate heated water through buildings, offering a safer and more uniform alternative to steam or direct coal fires.[25] Installed in prominent structures like the British Museum, Perkins' "high-pressure hot water" method reduced explosion risks associated with steam while enabling zoned control, reflecting the era's push for scalable indoor climate management amid coal-powered expansion.[26] This period's mechanization, fueled by steam technology and material advances like cast iron, transformed HVAC from localized, labor-intensive practices to centralized systems, setting the stage for broader adoption in residential and commercial settings. A key precursor to modern air conditioning emerged in 1902 when Willis Carrier patented an apparatus for humidity and temperature control, using cooled coils to dehumidify air in industrial spaces, though full integration awaited 20th-century electrification.[4] Overall, these developments underscored a conceptual shift toward engineered control of indoor environments, propelled by the Industrial Revolution's emphasis on efficiency and productivity.[27]Modern advancements

In the early 20th century, the invention of modern air conditioning marked a pivotal shift in HVAC technology, beginning with Willis Carrier's development of the first electrical air conditioning unit in 1902. Designed to control humidity in a Brooklyn printing plant, this system used cooling coils to regulate moisture levels, addressing a persistent issue in industrial processes like lithography.[4] Carrier's innovation laid the foundation for controlled indoor environments, evolving from industrial applications to broader use. Following World War II, widespread adoption of ducted air systems accelerated due to economic growth and housing booms, with high-velocity duct designs minimizing space requirements in office buildings. For instance, the 1948 Equitable Building in Portland featured Carrier's induction units with compact ducts, reducing operating costs by 10-25% compared to earlier all-air systems.[28] By the 1950s, these ducted systems became standard in commercial and residential structures, enabling efficient distribution of conditioned air.[28] Mid-20th-century advancements focused on energy efficiency amid growing resource demands, including the development of heat pumps in the 1930s, which reversed refrigeration cycles to extract heat from external sources for heating. Early prototypes, such as those using dry labyrinth piston compressors introduced by Sulzer, enabled practical applications without lubricants, paving the way for reversible HVAC operations.[29] The 1970s energy crises, triggered by oil embargoes, prompted regulatory responses, with ASHRAE releasing Standard 90 in 1975 as the first comprehensive energy conservation guideline for buildings. This standard addressed HVAC inefficiencies by mandating minimum performance levels for systems, influencing federal codes and reducing overall energy use in new constructions by up to 30% in targeted applications. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, environmental concerns drove refrigerant reforms and system innovations, exemplified by the 1987 Montreal Protocol, which phased out chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) due to their ozone-depleting effects. The treaty, ratified by over 190 countries, eliminated CFC production by 1996 in developed nations, spurring the adoption of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) and other alternatives in HVAC equipment.[30] Concurrently, variable refrigerant flow (VRF) systems emerged in Japan in the 1980s, pioneered by Daikin in 1982 as VRV (Variable Refrigerant Volume), allowing precise zoning and energy savings of 30-50% over traditional systems through modulated refrigerant distribution.[31] By the 2010s, integration of Internet of Things (IoT) enabled smart controls, with sensors and connectivity optimizing HVAC operations in real-time; for example, IoT-based predictive algorithms reduced energy consumption in commercial buildings by adjusting based on occupancy and weather data.[32] Recent trends since 2020 emphasize sustainability through renewables and artificial intelligence (AI), with HVAC systems increasingly coupled to solar photovoltaics and geothermal sources for net-zero performance. AI-driven optimization, using machine learning for predictive maintenance and load balancing, supports energy reductions while integrating variable renewable inputs, as demonstrated in building simulations that synchronize HVAC with on-site solar generation.[33] These advancements, supported by standards like ASHRAE 90.1 updates, prioritize decarbonization, with AI models forecasting demand to minimize grid strain from intermittent renewables.[33] Policy measures, such as the US Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 allocating funds for HVAC electrification and efficiency upgrades, have further accelerated these trends as of 2025.[34]Heating

Heat generation

Heat generation in HVAC systems primarily involves converting energy from fuels or electricity into thermal energy to warm indoor spaces. The most common methods include combustion of fossil fuels, electric resistance heating, and heat extraction via heat pumps from ambient sources. These approaches vary in efficiency, cost, and environmental impact, with selection depending on factors like fuel availability and climate.[35] Combustion-based systems, such as gas furnaces and oil boilers, produce heat through the burning of natural gas, propane, or heating oil. In natural gas combustion, the primary reaction is the oxidation of methane: , releasing significant heat energy. Oil boilers similarly combust fuel oil to generate hot combustion gases that transfer heat to water or air. These systems are widely used due to the abundance of fossil fuels and their ability to deliver high heat output rapidly.[36] Furnaces are key equipment in combustion heating, with forced-air types circulating heated air through ducts via a blower. Condensing furnaces achieve efficiencies over 90% by recovering latent heat from exhaust gases, condensing water vapor to extract additional energy before venting. Boilers, used for hydronic systems, come in fire-tube designs where hot gases pass through tubes surrounded by water, or water-tube variants where water flows through tubes exposed to combustion gases; fire-tube boilers are more common in residential HVAC for their simplicity and lower pressure requirements. Efficiency for both furnaces and boilers is measured by Annual Fuel Utilization Efficiency (AFUE), which represents the percentage of fuel energy converted to useful heat over a year—modern units often exceed 90% AFUE.[35][37][38] Electric resistance heaters generate heat by passing current through resistive elements, converting electrical energy directly to thermal energy with 100% efficiency at the point of use, though overall system efficiency depends on electricity generation sources. These include baseboard heaters, electric furnaces, and radiant panels, suitable for smaller spaces or as supplemental heating.[39] Heat pumps provide heat by extracting it from ambient air, ground, or water sources and transferring it indoors using a refrigeration cycle, often achieving efficiencies two to three times higher than resistance heating since they move heat rather than generate it. Air-source heat pumps, for instance, can reduce electricity use for heating by up to 75% compared to electric resistance systems.[40] Emerging methods include solar thermal collectors, which absorb sunlight to heat a transfer fluid for domestic hot water or space heating integration in HVAC systems. Flat-plate or evacuated-tube collectors can preheat water, reducing reliance on conventional fuels and improving overall system sustainability. Once generated, heat is typically distributed via air ducts or hydronic loops to end-use areas.[41]Distribution methods

In heating systems, distribution methods transport thermal energy from the source, such as a boiler, to occupied spaces through dedicated networks designed for efficient delivery. These methods primarily include hydronic and air-based approaches, which differ in their medium of transport—water or air—and influence factors like installation complexity, response time, and overall system performance.[42] Hydronic systems circulate heated water or steam through a closed loop of pipes to transfer heat to rooms via emitters like radiators, baseboard convectors, or underfloor heating loops. In hot water systems, a pump drives the fluid from the boiler through insulated piping to these emitters, where heat is released primarily by convection and radiation, allowing for even temperature distribution without drafts. Steam systems operate similarly but rely on natural pressure differences for circulation, though they are less common in modern installations due to higher energy use. Underfloor hydronic loops embed PEX or similar plastic pipes in concrete slabs or flooring, providing radiant heating that warms surfaces directly for improved comfort.[42][43][44] To ensure proper flow in hydronic piping, engineers calculate pressure drops using the Darcy-Weisbach equation, which accounts for friction losses: Here, is the pressure loss, is the friction factor, is pipe length, is diameter, is fluid density, and is velocity; this helps size pumps and pipes to minimize energy consumption while maintaining adequate circulation.[45] Air-based systems distribute heat by forcing heated air through ductwork from a furnace or air handler to vents in each space, enabling rapid temperature changes but potentially causing uneven heating if ducts are poorly designed. Fan coil units serve as localized air handlers in these systems, drawing room air over a hot water or electric coil and redistributing it, often integrated into ducted setups for zoned applications. Ducts must be sealed and insulated to prevent heat loss, with typical materials like sheet metal or flexible insulated tubing used to route air efficiently.[42][46] Zoned distribution enhances control by dividing a building into independent areas, each managed by separate thermostats that signal motorized dampers in the ducts or pipes to regulate flow. For instance, in a multi-story home, dampers close off unused zones to direct heat where needed, improving comfort and reducing waste; this setup requires a central control panel to coordinate signals and prevent pressure imbalances.[47][48] Efficiency in distribution methods hinges on minimizing losses through insulation and optimizing circulation energy. Pipes and ducts insulated with materials like fiberglass or foam can reduce heat loss by up to 20-30% in unconditioned spaces, while variable-speed pumps in hydronic systems and efficient fans in air-based setups lower electricity use by adjusting to demand—potentially saving 10-15% on operating costs compared to constant-speed alternatives. Regular maintenance, such as bleeding air from hydronic lines or cleaning duct filters, further sustains performance.[42][49][43]Safety risks

Heating systems pose several safety risks, primarily stemming from combustion processes in fuel-burning appliances such as furnaces and boilers. Incomplete combustion occurs when there is insufficient oxygen during fuel burning, leading to the production of carbon monoxide (CO) instead of carbon dioxide. This reaction can be represented as , where carbon from the fuel partially oxidizes.[50][51] Carbon monoxide is a colorless, odorless gas that binds to hemoglobin in the blood, preventing oxygen transport and causing poisoning symptoms ranging from headaches to death.[52][53] Common sources include malfunctioning gas furnaces, blocked vents, or cracked heat exchangers in heating systems.[54] Proper flue gas venting is essential to expel these byproducts outdoors, with requirements specifying termination heights of at least 5 feet above the appliance draft hood and clearances from combustibles to prevent re-entry into living spaces.[55] Fire hazards in heating systems often arise from overheating in furnaces, where restricted airflow from dirty filters or blocked ducts causes excessive temperatures that can ignite nearby materials.[56] The National Fire Protection Association reports that heating equipment contributes to thousands of home fires annually, many linked to such overheating or improper installation.[56] In hybrid systems combining furnaces with heat pumps, flammable refrigerants like hydrocarbons introduce additional ignition risks if leaks occur near heat sources, potentially leading to combustion upon exposure to sparks or open flames.[57][58] Other dangers include scalding from hot water heating systems, where temperatures exceeding 120°F can cause severe burns in seconds, particularly affecting children and the elderly during bathing or faucet use.[59][60] Electrical faults in electric heaters, such as frayed cords or overloaded circuits, can result in shocks, short circuits, or fires, especially if extension cords are misused.[61][62] Mitigation strategies focus on detection, compliance, and maintenance. Carbon monoxide detectors, placed near sleeping areas and fuel-burning appliances, provide early warnings by alarming at concentrations above 70 parts per million, allowing prompt evacuation and system shutdown.[63] Building codes like NFPA 54, the National Fuel Gas Code, mandate safe installation practices for gas appliances, including proper venting, pressure regulation, and combustion air supply to minimize risks.[64] Regular professional inspections, recommended annually before heating season, identify issues like heat exchanger cracks or venting blockages, ensuring system integrity and reducing hazard potential.[65]Ventilation

Mechanical systems

Mechanical ventilation systems utilize powered equipment, such as fans and ducts, to actively circulate and exchange air within buildings, ensuring adequate indoor air quality and comfort. These systems are categorized into exhaust, supply, and balanced types, each designed to address specific airflow needs. Exhaust systems remove contaminated air from indoor spaces using fans to draw air out, creating negative pressure that pulls in fresh air through leaks or openings. Supply systems, conversely, introduce filtered outdoor air into the building via fans, generating positive pressure to expel stale air. Balanced systems combine both exhaust and supply functions with equal airflow rates, maintaining neutral pressure and often incorporating energy recovery ventilators for efficiency. Positive pressure designs prevent infiltration of unconditioned air by slightly over-pressurizing interiors, while negative pressure setups isolate contaminants by drawing air inward from cleaner sources.[66][67] Key components include fans, ducts, and dampers, which work together to control airflow. Fans are primarily centrifugal or axial types; centrifugal fans accelerate air radially outward, providing high pressure for overcoming duct resistance in complex systems, whereas axial fans propel air parallel to the shaft, offering high volume at lower pressure for simpler applications. Duct sizing accounts for friction losses to minimize energy use, calculated using the Darcy-Weisbach equation: , where is head loss, is the friction factor, is duct length, is diameter, is velocity, and is gravity. Dampers, such as volume or fire dampers, regulate airflow, isolate sections, or respond to emergencies by adjusting or blocking passages.[68][69][70] In applications like commercial buildings and kitchens, mechanical systems ensure contaminant removal and compliance with standards. Commercial structures often employ balanced systems to meet ventilation rates specified in ASHRAE Standard 62.1, distributing air through extensive duct networks for offices and retail spaces. Kitchens use exhaust-dominant setups with grease-rated ducts and hoods to capture cooking fumes, as outlined in ASHRAE's design guides. Energy consumption is a critical factor, with fan power determined by , where is power, is volumetric flow rate, is total pressure rise, and is fan efficiency; this formula highlights the need for optimized designs to limit operational costs.[71][72][73] Controls enhance system performance through variable speed drives (VSDs), which adjust fan speeds based on real-time demand, such as occupancy or air quality sensors, reducing energy use by up to 50% compared to constant-speed operation. ASHRAE guidelines endorse VSDs for variable airflow systems to align ventilation with needs, minimizing over-ventilation.[74][75]Passive systems