Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

A cube is a three-dimensional solid object in geometry. A cube has eight vertices and twelve straight edges of the same length, so that these edges form six square faces of the same size. It is an example of a polyhedron.

The cube is found in many popular cultures, including toys and games, the arts, optical illusions, and architectural buildings. Cubes can be found in crystal structures, science, and technological devices. It is also found in ancient texts, such as Plato's work Timaeus, which described a set of solids now called Platonic solids, associating a cube with the classical element of earth. A cube with unit length is the canonical unit of volume in three-dimensional space, relative to which other solid objects are measured.

The cube relates to the construction of many polyhedra, such as truncation and attaching to other polyhedra. It also represents geometrical shapes. The cube can be attached to its faces with its copy to fill a space without leaving a gap, which forms a honeycomb.

The cube can be represented in many ways. One example is by drawing a graph, a structure in graph theory consisting of a set of vertices that are connected with an edge. This graph also represents the family of a cuboid, a polyhedron with six quadrilateral faces, which includes the cube as its special case. The cube and its graph are a three-dimensional hypercube, a family of polytopes that also includes the two-dimensional square and four-dimensional tesseract.

Properties

[edit]

A cube is a polyhedron with eight vertices and twelve equal-length edges, forming six squares as its faces. A cube is a special case of a rectangular cuboid, which has six rectangular faces, each of which has a pair of opposite equal-length and parallel edges.[1] Both polyhedra have the same dihedral angle, the angle between two adjacent faces at a common edge, a right angle or 90°, obtained from the interior angle (an angle formed between two adjacent sides at a common point of a polygon within) of a square.[2][3] More generally, the cube and the rectangular cuboid are special cases of a cuboid, a polyhedron with six quadrilaterals (four-sided polygons).[4] As for all convex polyhedra, the cube has Euler characteristic of 2, according to the formula ; the three letters denote respectively the number of vertices, edges, and faces.[5]

All three square faces surrounding a vertex are orthogonal to each other, meaning the planes are perpendicular, forming a right angle between two adjacent squares. Hence, the cube is classified as an orthogonal polyhedron.[6] The cube is a special case of other cuboids. These include a parallelepiped, a polyhedron with six parallelograms faces, because its pairs of opposite faces are congruent;[7] a rhombohedron, as a special case of a parallelepiped with six rhombi faces, because the interior angle of all of the faces is right;[8] and a trigonal trapezohedron, a polyhedron with congruent quadrilateral faces, since its square faces are the special cases of rhombi.[9]

The cube is a non-composite or an elementary polyhedron. That is, no plane intersecting its surface only along edges, thereby cutting into two or more convex, regular-faced polyhedra.[10]

Measurement

[edit]

Given a cube with edge length , the face diagonal of the cube is the diagonal of a square , and the space diagonal of the cube is a line connecting two vertices that are not in the same face, formulated as . Both formulas can be determined by using the Pythagorean theorem. The surface area of a cube is six times the area of a square:[11] The volume of a rectangular cuboid is the product of its length, width, and height. Because all the edges of a cube are equal in length, the formula for the volume of a cube is the third power of its side length.[11] This leads to the use of the term cube as a verb, to mean raising any number to the third power:[4]

The cube has three types of closed geodesics, or paths on a cube's surface that are locally straight. In other words, they avoid the vertices, follow line segments across the faces that they cross, and form complementary angles on the two incident faces of each edge that they cross. One type lies in a plane parallel to any face of the cube, forming a square congruent to a face, four times the length of each edge. Another type lies in a plane perpendicular to the long diagonal, forming a regular hexagon; its length is times that of an edge. The third type is a non-planar hexagon.[12]

Insphere, midsphere, circumsphere

[edit]An insphere of a cube is a sphere tangent to the faces of a cube at their centroids. Its midsphere is a sphere tangent to the edges of a cube. Its circumsphere is a sphere tangent to the vertices of a cube. With edge length , they are respectively:[13]

Unit cube

[edit]

A unit cube is a cube with 1 unit in length along each edge. It follows that each face is a unit square and that the entire figure has a volume of 1 cubic unit.[14][15] Prince Rupert of the Rhine, known for Prince Rupert's drop, wagered whether a cube could be passed through a hole made in another cube of the same size. The story recounted in 1693 by English mathematician John Wallis answered that it is possible, although there were some errors in Wallis's presentation. Roughly a century later, Dutch mathematician Pieter Nieuwland provided a better solution that the edges of a cube passing through the unit cube's hole could be as large as approximately 1.06 units in length.[16][17] One way to obtain this result is by using the Pythagorean theorem or the formula for Euclidean distance in three-dimensional space.[18]

An ancient problem of doubling the cube requires the construction of a cube with a volume twice the original by using only a compass and straightedge. This was concluded by French mathematician Pierre Wantzel in 1837, proving that it is impossible to implement since a cube with twice the volume of the original—the cube root of 2, —is not constructible.[19] However, this problem was solved with folding an origami paper by Messer (1986).[20]

Symmetry

[edit]

The cube has octahedral symmetry of order 48. In other words, the cube has 48 isometries (including identity), each of which transforms the cube to itself. These transformations include nine reflection symmetries (where two halves cut by a plane are identical): three cut the cube at the midpoints of its edges, and six cut diagonally. The cube also has thirteen axes of rotational symmetry (whereby rotation around the axis results in an identical appearance): three axes pass through the centroids of opposite faces, six through the midpoints of opposite edges, and four through opposite vertices; these axes are respectively four-fold rotational symmetry (0°, 90°, 180°, and 270°), two-fold rotational symmetry (0° and 180°), and three-fold rotational symmetry (0°, 120°, and 240°).[21][22][23][24]

The dual polyhedron can be obtained from each of the polyhedra's vertices tangent to a plane by a process known as polar reciprocation.[25] One property of dual polyhedra is that the polyhedron and its dual share their three-dimensional symmetry point group. In this case, the dual polyhedron of a cube is the regular octahedron, and both of these polyhedra have the same octahedral symmetry.[26]

The cube is face-transitive, meaning its two square faces are alike and can be mapped by rotation and reflection.[27] It is vertex-transitive, meaning all of its vertices are equivalent and can be mapped isometrically under its symmetry.[28] It is also edge-transitive, meaning the same kind of faces surround each of its vertices in the same or reverse order, and each pair of adjacent faces has the same dihedral angle. Therefore, the cube is a regular polyhedron.[29] Each vertex is surrounded by three squares, so the cube is by vertex configuration or by Schläfli symbol.[30]

Appearances

[edit]In popular cultures

[edit]Cubes have appeared in many roles in popular culture. It is the most common form of dice.[27] Puzzle toys such as pieces of a Soma cube,[31] Rubik's Cube, and Skewb are built of cubes.[32] Minecraft is an example of a sandbox video game of cubic blocks.[33] The outdoor sculpture Alamo (1967) is a cube that spins around its vertical axis.[34] Optical illusions such as the impossible cube and Necker cube have been explored by artists such as M. C. Escher.[35] The cube was applied in Alberti's treatise on Renaissance architecture, De re aedificatoria (1450).[36] Cube houses in the Netherlands are a set of cubical houses whose hexagonal space diagonals become the main floor.[37]

In nature and science

[edit]Cubes are also found in various fields of natural science and technology. It is applied to the unit cell of a crystal known as a cubic crystal system.[38] Table salt is an example of a mineral with a commonly cubic shape.[39] Other examples are pyrite (although there are many variations)[40] and uranium cubic-shaped in nuclear program.[41] The radiolarian Lithocubus geometricus, discovered by Ernst Haeckel, has a cubic shape.[42] Cubane is a synthetic hydrocarbon consisting of eight carbon atoms arranged at the corners of a cube, with one hydrogen atom attached to each carbon atom.[43]

A historical attempt to unify three physics ideas of relativity, gravitation, and quantum mechanics used the framework of a cube known as a cGh cube.[44]

Technological cubes include the spacecraft device CubeSat,[45] thermal radiation demonstration device Leslie cube,[46] and web server machine Cobalt Qube.[47] Cubical grids are usual in three-dimensional Cartesian coordinate systems.[48] In computer graphics, an algorithm divides the input volume into a discrete set of cubes known as the unit on isosurface,[49] and the faces of a cube can be used for mapping a shape.[50] In various areas of engineering, including traffic signs and radar, the corner of a cube is useful as a retroreflector, called a corner reflector, which redirects any ray or wave back to its source.[51]

In antiquity

[edit]The Platonic solids are five polyhedra known since antiquity. The set is named for Plato, who attributed these solids to nature in his dialogue Timaeus. One of them, the cube, represented the classical element of earth because of the building blocks of Earth's foundation.[52] Euclid's Elements defined the Platonic solids, including the cube, and showed how to find the ratio of the circumscribed sphere's diameter to the edge length.[53]

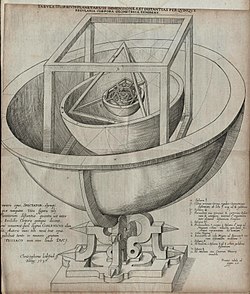

Following Plato's use of the regular polyhedra as symbols of nature, Johannes Kepler in his Harmonices Mundi sketched each of the Platonic solids; he decorated the cube's side with a tree.[54] In his Mysterium Cosmographicum, Kepler proposed the structure of Solar System and the relationships between its extraterrestrial planets with the set of Platonic solids, inscribed and circumscribed by spherical orbs. Each solid encased in a sphere, within one another, would produce six layers, corresponding to the six known planets. Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. From innermost to outermost, these solids were arranged from octahedron, followed by the icosahedron, dodecahedron, tetrahedron, and eventually the cube.[55]

Constructions

[edit]

The cube has eleven different nets, which consist of an arrangement of edge-joined squares. These squares can be folded along the edges and connected to those polygons, which eventually become the faces of a cube.[56][57]

In analytic geometry, a cube may be constructed using the Cartesian coordinate systems. For a cube centered at the origin, with edges parallel to the axes and with an edge length of 2, the Cartesian coordinates of the vertices are .[58] Its interior consists of all points with for all . A cube's surface with center and edge length of is the locus of all points such that

The cube is a Hanner polytope, because it can be constructed by using the Cartesian product of three line segments. Its dual polyhedron, the regular octahedron, is constructed by the direct sum of three line segments.[59]

Representation

[edit]As a graph

[edit]

The cube can be drawn into a graph, a structure in graph theory consisting of a set of vertices that are connected with an edge. It is attainable according to Steinitz's theorem, which states that a graph can be represented as the vertex-edge graph of a polyhedron, as long as it possesses the following two properties. These are planarity (the edges of a graph are connected to every vertex without crossing other edges), and 3-connected (whenever a graph with more than three vertices, and two of the vertices are removed, the edges remain connected).[60][61] The skeleton of a cube, represented as the graph, is called the cubical graph, a Platonic graph. It has the same number of vertices and edges as the cube, twelve vertices and eight edges.[62] The cubical graph is also classified as a prism graph, resembling the skeleton of a cuboid.[63]

The cubical graph is a special case of hypercube graph or -cube—denoted as —because it can be constructed by using the Cartesian product of graphs: two graphs connecting the pair of vertices with an edge to form a new graph.[64] In the case of the cubical graph, it is the product of , where denotes the Cartesian product of graphs. In other words, the cubical graph is constructed by connecting each vertex of two squares with an edge. Notationally, the cubical graph is .[65] Like any hypercube graph, it has a cycle which visits every vertex exactly once,[66] and it is also an example of a unit distance graph.[67]

The cubical graph is bipartite, meaning every independent set of four vertices can be disjoint and the edges connected in those sets.[68] However, every vertex in one set cannot connect all vertices in the second, so this bipartite graph is not complete.[69] It is an example of both a crown graph and a bipartite Kneser graph.[70][68]

In orthogonal projection

[edit]An object illuminated by parallel rays of light casts a shadow on a plane perpendicular to those rays, called an orthogonal projection. A polyhedron is considered equiprojective if, for some position of the light, its orthogonal projection is a regular polygon. The cube is equiprojective because, if the light is parallel to one of the four lines joining a vertex to the opposite vertex, its projection is a regular hexagon.[71]

As a configuration matrix

[edit]The cube can be represented as a configuration matrix, a matrix in which the rows and columns correspond to the elements of a polyhedron as the vertices, edges, and faces. The diagonal of a matrix denotes the number of each element that appears in a polyhedron, whereas the non-diagonal of a matrix denotes the number of the column's elements that occur in or at the row's element. The cube's eight vertices, twelve edges, and six faces are denoted by each element in a matrix's diagonal (8, 12, and 6). The first column of the middle row indicates that there are two vertices on each edge, denoted as 2; the middle column of the first row indicates that three edges meet at each vertex, denoted as 3. The configuration matrix of a cube is:[72]

Related topics

[edit]Construction of polyhedra

[edit]Many polyhedra can be constructed based on a cube. Examples include:

- When faceting a cube, meaning removing part of the polygonal faces without creating new vertices of a cube, the resulting polyhedron is the stellated octahedron.[73]

- New convex polyhedra can be constructed by attaching less-regular polyhedra to a cube's faces.[10] The cube is thus a component of two Johnson solids, the elongated square pyramid and elongated square bipyramid, the latter being a cube with square pyramids on opposite faces.[74]

- Attaching a low pyramid to each face of a cube produces its Kleetope, the tetrakis hexahedron,[75] dual to the truncated octahedron.

- The barycentric subdivision of a cube (or its dual, the regular octahedron) is the disdyakis dodecahedron, a Catalan solid.[76]

- The corner region of a cube can also be truncated by a plane (e.g., spanned by the three neighboring vertices), resulting in a trirectangular tetrahedron.[77]

- The snub cube is an Archimedean solid that can be constructed by separating the cube's faces, and filling the gaps with twisted angle equilateral triangles, a process known as a snub.[78]

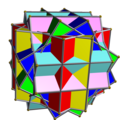

- Each of the cube's vertices can be truncated, and the resulting polyhedron is the Archimedean solid, the truncated cube.[79] When its edges are truncated, it is a rhombicuboctahedron.[80] Relatedly, the rhombicuboctahedron can also be constructed by separating the cube's faces and then spreading away, after which adding other triangular and square faces between them; this is known as the "expanded cube". The same figure can be derived in the same way from the cube's dual, the regular octahedron.[81]

- The chamfered cube is constructed from a cube by a truncating operator called chamfer. The resulting polyhedron has twelve hexagonal and six square centrally symmetric faces, a zonohedron.[82][83]

- Three mutually perpendicular golden rectangles can be constructed from a pair of vertices located on the midpoints of the opposite edges on a cube's surface, drawing a segment line between those two, and dividing that segment line in a golden ratio from its midpoint. The corners of these rectangles are the vertices of a regular icosahedron with twenty equilateral triangles.[84]

The cube can be constructed with six square pyramids, tiling space by attaching their apices. In some cases, this produces the rhombic dodecahedron circumscribing a cube.[85][86]

Polycubes

[edit]A polycube is a solid figure formed by joining one or more equal cubes face-to-face. Polycubes are the three-dimensional analogues of two-dimensional polyominoes.[87]

When four cubes are stacked vertically, and four others are attached to the second-from-top cube of the stack, the resulting polycube is the Dalí cross, named after Spanish surrealist artist Salvador Dalí, whose painting Corpus Hypercubus (1954) contains a tesseract unfolding into a six-armed cross; a similar construction is central to Robert A. Heinlein's short story "And He Built a Crooked House" (1940).[88][89] The Dalí cross can be folded in a fourth dimension to enclose a tesseract.[90] A cube is a three-dimensional instance of a hypercube (also known as a 3-cube); the two-dimensional hypercube (2-cube) is a square, and the four-dimensional hypercube (4-cube) is a tesseract.[91]

Space-filling

[edit]

A cube can achieve a honeycomb by filling together with its copy in three-dimensional space without leaving a gap. Cubes are space-fillings, where the phrase "space-filling" can be understood as a generalized tessellation.[92] The cube is a plesiohedron, a special kind of space-filling polyhedron that can be defined as the Voronoi cell of a symmetric Delone set.[93] The plesiohedra include the parallelohedra, which can be translated without rotating to fill a space in which each face of any of its copies is attached to a like face of another copy. There are five kinds of parallelohedra, one of which is the parallelepiped.[94] Every three-dimensional parallelohedron is a zonohedron, a centrally symmetric polyhedron whose faces are centrally symmetric polygons.[95]

An example of a honeycomb with a cubic type only, called a cell, is a cubic honeycomb that consists of four cubes around its edges in Euclidean three-dimensional space.[96][97] More examples in three-dimensional non-Euclidean space are the honeycomb with three cubes around its edges in a three-dimensional sphere and the honeycomb with five cubes around its edges in hyperbolic space.[97]

Any parallelepiped, including a cube, can achieve a honeycomb if its Dehn invariant is zero.[98] The Dehn invariant's inception dates back to Hilbert's third problem, whether every two equal-volume polyhedra can always be dissected into polyhedral pieces and reassembled into each other. If yes, then the volume of any polyhedron could be defined axiomatically as the volume of an equivalent cube into which it could be reassembled. This problem was solved by Max Dehn, inventing his invariant, answering that not all polyhedra can be reassembled into a cube.[99] It showed that two equal volume polyhedra should have the same Dehn invariant, except for the two tetrahedra whose Dehn invariants were different.[100]

Miscellanea

[edit]The polyhedral compounds, in which the cubes share the same centre, are uniform polyhedron compounds, meaning they are polyhedral compounds whose constituents are identical—although possibly enantiomorphous—uniform polyhedra, in an arrangement that is also uniform. Respectively, the list of compounds enumerated by Skilling (1976) in the seventh to ninth uniform compounds for the compound of six cubes with rotational freedom, three cubes, and five cubes.[101] Two compounds, consisting of two and three cubes were found in Escher's wood engraving print Stars and Max Brückner's book Vielecke und Vielflache.[102]

The spherical cube represents the spherical polyhedron, which can be modeled with the arcs of great circles, creating bounds as the edges of a spherical square.[103] Hence, the spherical cube consists of six spherical squares with 120° interior angles on each vertex. It has vector equilibrium, meaning that the distance from the centroid and each vertex is the same as the distance from that to each edge.[104][105] Its dual is the spherical octahedron.[103]

The topological object three-dimensional torus is a topological space defined to be homeomorphic to the Cartesian product of three circles. It can be represented as a three-dimensional model of the cube shape.[106]

A cube can have fractal shapes, which retain the pattern shape recursively regardless of the magnification. The Menger sponge is an example of a fractal-shaped cube, analogous to the two-dimensional version, the Sierpiński carpet.[107] Other varieties are the Jerusalem cube and Mosely snowflake.[108][109]

See also

[edit]- Bhargava cube, a configuration to study the law of binary quadratic form and other such forms, of which the cube's vertices represent the integer.

- Chazelle polyhedron, a notched opposite faces of a cube.

- Cubism, an art movement of revolutionized painting and the visual arts.

- Hemicube, an abstract polyhedron produced by identifying opposite faces of a cube

- Kaaba, cubic buildings of importance to Islam.

- Magic cube, a magic square in three-dimensional version

- Schläfli double six, a configuration of 30 points and 12 lines in three-dimensional Euclidean space

- Squaring the square's three-dimensional analogue, cubing the cube

- Superellipsoid, a solid whose horizontal sections are of the same squareness

- Tychonoff cube, generalization of a unit cube

References

[edit]- ^ Dupuis, Nathan Fellowes (1893). Elements of Synthetic Solid Geometry. Macmillan. p. 68.

- ^ Johnson, Norman W. (1966). "Convex Polyhedra with Regular Faces". Canadian Journal of Mathematics. 18: 169–200. doi:10.4153/cjm-1966-021-8. MR 0185507. S2CID 122006114. Zbl 0132.14603. See table II, line 3.

- ^ Bird, John (2020). Science and Mathematics for Engineering (6th ed.). Routledge. pp. 143–144. ISBN 9780429261701.

- ^ a b Mills, Steve; Kolf, Hillary (1999). Maths Dictionary. Heinemann. p. 16. ISBN 9780435024741.

- ^ Richeson, D. S. (2008). Euler's Gem: The Polyhedron Formula and the Birth of Topology. Princeton University Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9780691126777.

- ^ Jessen, Børge (1967). "Orthogonal Icosahedra". Nordisk Matematisk Tidskrift. 15 (2): 90–96. JSTOR 24524998. MR 0226494.

- ^ Calter, Paul; Calter, Michael (2011). Technical Mathematics. John Wiley & Sons. p. 197. ISBN 9780470534922.

- ^ Hoffmann (2020), p. 83.

- ^ Chilton, B. L.; Coxeter, H. S. M. (1963). "Polar Zonohedra". The American Mathematical Monthly. 70 (9): 946–951. doi:10.1080/00029890.1963.11992147. JSTOR 2313051. MR 0157282.

- ^ a b Timofeenko, A. V. (2010). "Junction of Non-composite Polyhedra" (PDF). St. Petersburg Mathematical Journal. 21 (3): 483–512. doi:10.1090/S1061-0022-10-01105-2.

- ^ a b Khattar, Dinesh (2008). Guide to Objective Arithmetic (2nd ed.). Pearson Education. p. 377. ISBN 9788131716823.

- ^ Fuchs, Dmitry; Fuchs, Ekaterina (2007). "Closed Geodesics on Regular Polyhedra" (PDF). Moscow Mathematical Journal. 7 (2): 265–279. See Figure 11, p. 273, for showing three types of cube's geodesics.

- ^ Coxeter (1973) Table I(i), pp. 292–293. See the columns labeled , , and , Coxeter's notation for the circumradius, midradius, and inradius, respectively, also noting that Coxeter uses as the edge length (see p. 2).

- ^ Ball, Keith (2010). "High-dimensional Geometry and Its Probabilistic Analogues". In Gowers, Timothy (ed.). The Princeton Companion to Mathematics. Princeton University Press. p. 671. ISBN 9781400830398.

- ^ Geometry: Reteaching Masters. Holt Rinehart & Winston. 2001. p. 74. ISBN 9780030543289.

- ^ Jerrard, Richard P.; Wetzel, John E. (2004). "Prince Rupert's rectangles". The American Mathematical Monthly. 111 (1): 22–31. doi:10.2307/4145012. JSTOR 4145012. MR 2026310.

- ^ Rickey, V. Frederick (2005). "Dürer's Magic Square, Cardano's Rings, Prince Rupert's Cube, and Other Neat Things" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-05. Notes for “Recreational Mathematics: A Short Course in Honor of the 300th Birthday of Benjamin Franklin,” Mathematical Association of America, Albuquerque, NM, August 2–3, 2005

- ^ Gardner, Martin (2001). The Colossal Book of Mathematics: Classic Puzzles, Paradoxes, and Problems: Number Theory, Algebra, Geometry, Probability, Topology, Game Theory, Infinity, and Other Topics of Recreational Mathematics. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 172–173. ISBN 9780393020236.

- ^ Lützen, Jesper (2010). "The Algebra of Geometric Impossibility: Descartes and Montucla on the Impossibility of the Duplication of the Cube and the Trisection of the Angle". Centaurus. 52 (1): 4–37. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0498.2009.00160.x.

- ^ Messer, Peter (1986). "Problem 1054" (PDF). Crux Mathematicorum. 12 (10): 284–285 – via Canadian Mathematical Society.

- ^ French, Doug (1988). "Reflections on a Cube". Mathematics in School. 17 (4): 30–33. JSTOR 30214515.

- ^ Cromwell, Peter R. (1997). Polyhedra. Cambridge University Press. p. 309. ISBN 9780521554329.

- ^ Cunningham, Gabe; Pellicer, Daniel (2024). "Finite 3-orbit Polyhedra in Ordinary Space, II". Boletín de la Sociedad Matemática Mexicana. 30 (32) 32. doi:10.1007/s40590-024-00600-z. See p. 276.

- ^ Kane, Richard (2001). Reflection Groups and Invariant Theory. Springer. p. 16. ISBN 9780387989792.

- ^ Cundy, H. Martyn; Rollett, A.P. (1961). "3.2 Duality". Mathematical Models (2nd ed.). Clarendon Press. pp. 78–79. MR 0124167.

- ^ Erickson, Martin (2011). Beautiful Mathematics. Mathematical Association of America. p. 62. ISBN 9781614445098.

- ^ a b McLean, K. Robin (1990). "Dungeons, Dragons, and Dice". The Mathematical Gazette. 74 (469): 243–256. doi:10.2307/3619822. JSTOR 3619822. S2CID 195047512. See p. 247.

- ^ Grünbaum, Branko (1997). "Isogonal Prismatoids". Discrete & Computational Geometry. 18 (1): 13–52. doi:10.1007/PL00009307.

- ^ Senechal, Marjorie (1989). "A Brief Introduction to Tilings". In Jarić, Marko (ed.). Introduction to the Mathematics of Quasicrystals. Academic Press. p. 12.

- ^ Walter, Steurer; Deloudi, Sofia (2009). Crystallography of Quasicrystals: Concepts, Methods and Structures. Springer Series in Materials Science. Vol. 126. p. 50. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-01899-2. ISBN 9783642018985.

- ^ Masalski, William J. (1977). "Polycubes". The Mathematics Teacher. 70 (1): 46–50. doi:10.5951/MT.70.1.0046. JSTOR 27960702.

- ^ Joyner, David (2008). Adventures in Group Theory: Rubik's Cube, Merlin's Machine, and Other Mathematical Toys (2nd ed.). The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 76. ISBN 9780801890123.

- ^ Moore, Kimberly (2018). "Minecraft Comes to Math Class". Mathematics Teaching in the Middle School. 23 (6): 334–341. doi:10.5951/mathteacmiddscho.23.6.0334. JSTOR 10.5951/mathteacmiddscho.23.6.0334.

- ^ Reaven, Marci; Zeilten, Steve (2006). Hidden New York: A Guide to Places that Matter. Rutgers University Press. p. 77. ISBN 9780813538907.

- ^ Barrow, John D. (1999). Impossibility: The Limits of Science and the Science of Limits. Oxford University Press. p. 14. ISBN 9780195130829.

- ^ March, Lionel (1996). "Renaissance Mathematics and Architectural Proportion in Alberti's De re aedificatoria". Architectural Research Quarterly. 2 (1): 54–65. doi:10.1017/S135913550000110X. S2CID 110346888.

- ^ Alsina, Claudi; Nelsen, Roger B. (2015). A Mathematical Space Odyssey: Solid Geometry in the 21st Century. Vol. 50. Mathematical Association of America. p. 85. ISBN 9781614442165.

- ^ Tisza, Miklós (2001). Physical Metallurgy for Engineers. ASM International. p. 45. ISBN 9781615032419.

- ^ Chieh, Chung (2013). "Polyhedra and Crystal Structures". In Senechal, Marjorie (ed.). Shaping Space: Exploring Polyhedra in Nature, Art, and the Geometrical Imagination. Springer. p. 141. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-92714-5_10. ISBN 9780387927138.

- ^ Hoffmann, Frank (2020). Introduction to Crystallography. Springer. p. 35. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-35110-6. ISBN 9783030351106.

- ^ Kratz, Jens-Volker (2021). Nuclear and Radiochemistry: Fundamentals and Applications. John Wiley & Sons. p. 31. doi:10.1002/9783527831944. ISBN 9783527831944.

- ^ Haeckel, E. (1904). Kunstformen der Natur (in German). See here for an online book.

- ^ Biegasiewicz, Kyle; Griffiths, Justin; Savage, G. Paul; Tsanakstidis, John; Priefer, Ronny (2015). "Cubane: 50 Years Later". Chemical Reviews. 115 (14): 6719–6745. doi:10.1021/cr500523x. PMID 26102302.

- ^ Padmanabhan, Thanu (2015). "The Grand Cube of Theoretical Physics". Sleeping Beauties in Theoretical Physics. Springer. pp. 1–8. ISBN 9783319134420.

- ^ Helvajian, Henry; Janson, Siegfried W., eds. (2008). Small Satellites: Past, Present, and Future. Aerospace Press. p. 159. ISBN 9781884989223.

- ^ Vollmer, Michael; Möllmann, Klaus-Peter (2011). Infrared Thermal Imaging: Fundamentals, Research and Applications. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 36–38. ISBN 9783527641550.

- ^ Sims, Ralph (Oct 1, 1998). "Cobalt Qube Microserver". Linux Journal.

- ^ Kov´acs, Gergely; Nagy, Benedek Nagy; Stomfai, Gergely; Turgay, Nes¸et Deni̇z; Vizv´ari, B´ela (2021). "On Chamfer Distances on the Square and Body-Centered CubicGrids: An Operational Research Approach". Mathematical Problems in Engineering: 1–9. doi:10.1155/2021/5582034. hdl:10831/111490.

- ^ Chin, Daniel Jie Yuan Chin; Mohamed, Ahmad Sufril Azlan; Shariff, Khairul Anuar; Ishikawa, Kunio (23–25 November 2021). "GPU-Accelerated Enhanced Marching Cubes 33 for Fast 3D Reconstruction of Large Bone Defect CT Images". In Zaman, Halimah Badioze; Smeaton, Alan; Shih, Timothy; Velastin, Sergio; Terutoshi, Tada; Jørgensen, Bo Nørregaard; Aris, Hazleen Aris; Ibrahim, Nazrita Ibrahim (eds.). Advances in Visual Informatics. 7th International Visual Informatics Conference. Kajang, Malaysia. p. 376.

- ^ Greene, N (1986). "Environment Mapping and Other Applications of World Projections". IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications. 6 (11): 21–29. Bibcode:1986ICGA....6k..21G. doi:10.1109/MCG.1986.276658. S2CID 11301955.

- ^ Kraus, John D.; Fleisch, Daniel A. (1999). Electromagnetics With Applications. Boston: McGraw Hill. p. 324. ISBN 0-07-289969-7. LCCN 98-34935.

- ^ Domokos, Gábor; Jerolmack, Douglas J.; Kun, Ferenc; Török, János (2020). "Plato's Cube and the Natural Geometry of Fragmentation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117 (31): 18178–18185. arXiv:1912.04628. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11718178D. doi:10.1073/pnas.2001037117. PMID 32680966.

- ^ Heath, Thomas L. (1908). The Thirteen Books of Euclid's Elements (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 262, 478, 480.

- ^ Cromwell (1997), p. 55.

- ^ Livio, Mario (2003) [2002]. The Golden Ratio: The Story of Phi, the World's Most Astonishing Number (1st trade paperback ed.). Broadway Books. p. 147. ISBN 9780767908160.

- ^ Jeon, Kyungsoon (2009). "Mathematics Hiding in the Nets for a CUBE". Teaching Children Mathematics. 15 (7): 394–399. doi:10.5951/TCM.15.7.0394. JSTOR 41199313.

- ^ Turney, Peter D. (1984–1985). "Unfolding the Tesseract". Journal of Recreational Mathematics. 17 (1).

- ^ Smith, James (2000). Methods of Geometry. John Wiley & Sons. p. 392. ISBN 9781118031032.

- ^ Kozachok, Marina (2012). "Perfect Prismatoids and the Conjecture Concerning with Face Numbers of Centrally Symmetric Polytopes". Yaroslavl International Conference "Discrete Geometry" Dedicated to the Centenary of A.D. Alexandrov (Yaroslavl, August 13-18, 2012) (PDF). P.G. Demidov Yaroslavl State University, International B.N. Delaunay Laboratory. pp. 46–49.

- ^ Grünbaum, Branko (2003). "13.1 Steinitz's Theorem". Convex Polytopes. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. Vol. 221 (2nd ed.). Springer-Verlag. pp. 235–244. ISBN 0387404090.

- ^ Ziegler, Günter M. (1995). "Chapter 4: Steinitz' Theorem for 3-Polytopes". Lectures on Polytopes. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. Vol. 152. Springer-Verlag. pp. 103–126. ISBN 038794365X.

- ^ Rudolph, Michael (2022). The Mathematics of Finite Networks: An Introduction to Operator Graph Theory. Cambridge University Press. p. 25. doi:10.1017/9781316466919. ISBN 9781316466919.

- ^ Pisanski, Tomaž; Servatius, Brigitte (2013). Configuration from a Graphical Viewpoint. Springer. p. 21. doi:10.1007/978-0-8176-8364-1. ISBN 9780817683634.

- ^ Harary, F.; Hayes, J. P.; Wu, H.-J. (1988). "A Survey of the Theory of Hypercube Graphs". Computers & Mathematics with Applications. 15 (4): 277–289. doi:10.1016/0898-1221(88)90213-1. hdl:2027.42/27522.

- ^ Chartrand, Gary; Zhang, Ping (2012). A First Course in Graph Theory. Dover Publications. p. 25. ISBN 9780486297309.

- ^ Gross, Jonathan L.; Yellen, Yellen (2006). Graph Theory and Its Applications, Second Edition. Taylor & Francis. p. 273. ISBN 9781584885054.

- ^ Horvat, Boris; Pisanski, Tomaž (2010). "Products of Unit Distance Graphs". Discrete Mathematics. 310 (12): 1783–1792. doi:10.1016/j.disc.2009.11.035. MR 2610282.

- ^ a b Berman, Leah (2014). "Geometric Constructions for Symmetric 6-Configurations". In Connelly, Robert; Weiss, Asia; Whiteley, Walter (eds.). Rigidity and Symmetry. Fields Institute Communications. Vol. 70. Springer. p. 84. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-0781-6. ISBN 9781493907816.

- ^ Aldous, Joan; Wilson, Robin (2000). Graphs and Applications: An Introductory Approach. Springer. ISBN 9781852332594.

- ^ Kitaev, Sergey; Lozin, Vadim (2015). Words and Graphs. p. 171. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-25859-1. ISBN 9783319258591.

- ^ Hasan, Masud; Hossain, Mohammad M.; López-Ortiz, Alejandro; Nusrat, Sabrina; Quader, Saad A.; Rahman, Nabila (2010). "Some New Equiprojective Polyhedra". arXiv:1009.2252 [cs.CG].

- ^ Coxeter, H.S.M. (1973). Regular Polytopes (3rd ed.). New York: Dover Publications. pp. 122–123. See §1.8 Configurations.

- ^ Inchbald, Guy (2006). "Facetting Diagrams". The Mathematical Gazette. 90 (518): 253–261. doi:10.1017/S0025557200179653. JSTOR 40378613.

- ^ Rajwade, A. R. (2001). Convex Polyhedra with Regularity Conditions and Hilbert's Third Problem. Texts and Readings in Mathematics. Hindustan Book Agency. p. 84–89. doi:10.1007/978-93-86279-06-4. ISBN 9789386279064.

- ^ Slobodan, Mišić; Obradović, Marija; Ðukanović, Gordana (2015). "Composite Concave Cupolae as Geometric and Architectural Forms" (PDF). Journal for Geometry and Graphics. 19 (1): 79–91.

- ^ Langer, Joel C.; Singer, David A. (2010). "Reflections on the Lemniscate of Bernoulli: The Forty-Eight Faces of a Mathematical Gem". Milan Journal of Mathematics. 78 (2): 643–682. doi:10.1007/s00032-010-0124-5.

- ^ Coxeter (1973), p. 71.

- ^ Holme, A. (2010). Geometry: Our Cultural Heritage. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-14441-7. ISBN 9783642144417.

- ^ Cromwell (1997), pp. 81–82.

- ^ Linti, G. (2013). "Catenated Compounds - Group 13 [Al, Ga, In, Tl]". In Reedijk, J.; Poeppelmmeier, K. (eds.). Comprehensive Inorganic Chemistry II: From Elements to Applications. Newnes. p. 41. ISBN 9780080965291.

- ^ Viana, Vera; Xavier, João Pedro; Aires, Ana Paula; Campos, Helena (2019). "Interactive Expansion of Achiral Polyhedra". In Cocchiarella, Luigi (ed.). ICGG 2018 - Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Geometry and Graphics 40th Anniversary - Milan, Italy, August 3-7, 2018. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing. Vol. 809. Springer. p. 1123. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-95588-9. ISBN 9783319955872. See Fig. 6.

- ^ Gelişgen, Özcan; Yavuz, Serhat (2019). "Isometry Groups of Chamfered Cube and Chamfered Octahedron Spaces". Mathematical Sciences and Applications E-Notes. 7 (2): 174–182. doi:10.36753/mathenot.542272.

- ^ Deza, Antoinea; Michel, Deza; Grishukhin, Viatcheslav (1998). "Fullerenes and Coordination Polyhedra versus Half-cube Embeddings". Discrete Mathematics. 192 (1–3): 41–80. doi:10.1016/S0012-365X(98)00065-X.

- ^ Cromwell (1997), p. 70.

- ^ Barnes, John (2012). Gems of Geometry (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 82. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-30964-9. ISBN 9783642309649.

- ^ Cundy, H. Martyn (1956). "2642. Unitary Construction of Certain Polyhedra". The Mathematical Gazette. 40 (234): 280–282. doi:10.2307/3609622. JSTOR 3609622.

- ^ Lunnon, W. F. (1972). "Symmetry of Cubical and General Polyominoes". In Read, Ronald C. (ed.). Graph Theory and Computing. New York: Academic Press. pp. 101–108. ISBN 9781483255125.

- ^ Kemp, Martin (1 January 1998). "Dali's Dimensions". Nature. 391 (27): 27. Bibcode:1998Natur.391...27K. doi:10.1038/34063.

- ^ Fowler, David (2010). "Mathematics in Science Fiction: Mathematics as Science Fiction". World Literature Today. 84 (3): 48–52. doi:10.1353/wlt.2010.0188. JSTOR 27871086. S2CID 115769478.

Robert Heinlein's "And He Built a Crooked House," published in 1940, and Martin Gardner's "The No-Sided Professor," published in 1946, are among the first in science fiction to introduce readers to the Moebius band, the Klein bottle, and the hypercube (tesseract).

- ^ Langerman, Stefan; Winslow, Andrew (2016). "Polycube Unfoldings Satisfying Conway's Criterion" (PDF). 19th Japan Conference on Discrete and Computational Geometry, Graphs, and Games (JCDCG^3 2016).

- ^ Hall, T. Proctor (1893). "The Projection of Fourfold Figures on a Three-flat". American Journal of Mathematics. 15 (2): 179–189. doi:10.2307/2369565. JSTOR 2369565.

- ^ Lagarias, J. C.; Moews, D. (1995). "Polytopes that Fill and Scissors Congruence". Discrete & Computational Geometry. 13 (3–4): 573–583. doi:10.1007/BF02574064. MR 1318797.

- ^ Erdahl, R. M. (1999). "Zonotopes, Dicings, and Voronoi's Conjecture on Parallelohedra". European Journal of Combinatorics. 20 (6): 527–549. doi:10.1006/eujc.1999.0294. MR 1703597.. Voronoi conjectured that all tilings of higher-dimensional spaces by translates of a single convex polytope are combinatorially equivalent to Voronoi tilings, and Erdahl proves this in the special case of zonotopes. But as he writes (p. 429), Voronoi's conjecture for dimensions at most four was already proven by Delaunay. For the classification of three-dimensional parallelohedra into these five types, see Grünbaum, Branko; Shephard, G. C. (1980). "Tilings with congruent tiles". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. New Series. 3 (3): 951–973. doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-1980-14827-2. MR 0585178.

- ^ Horváth, Ákos G. (1995). "On Dirichlet–Voronoi Cell, Part I: Classical Problems". Periodica Polytechnica Mechanical Engineering. 39 (1): 25–42.

- ^ In higher dimensions, however, there exist parallelopes that are not zonotopes. See e.g. Shephard, G. C. (1974). "Space-filling Zonotopes". Mathematika. 21 (2): 261–269. doi:10.1112/S0025579300008652. MR 0365332.

- ^ Coxeter, H. S. M. (1968). The Beauty of Geometry: Twelve Essays. Dover Publications. p. 167. ISBN 9780486409191. See table III.

- ^ a b Nelson, Roice; Segerman, Henry (2017). "Visualizing Hyperbolic Honeycombs". Journal of Mathematics and the Arts. 11 (1): 4–39. arXiv:1511.02851. doi:10.1080/17513472.2016.1263789.

- ^ Akiyama, Jin; Matsunaga, Kiyoko (2015). "15.3 Hilbert's Third Problem and Dehn Theorem". Treks Into Intuitive Geometry. Springer Tokyo. pp. 382–388. doi:10.1007/978-4-431-55843-9. ISBN 9784431558415. MR 3380801.

- ^ Gruber, Peter M. (2007). "Chapter 16: Volume of Polytopes and Hilbert's Third Problem". Convex and Discrete Geometry. Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften [Fundamental Principles of Mathematical Sciences]. Vol. 336. Springer, Berlin. pp. 280–291. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-71133-9. ISBN 9783540711322. MR 2335496.

- ^ Zeeman, E. C. (July 2002). "On Hilbert's third problem". The Mathematical Gazette. 86 (506): 241–247. doi:10.2307/3621846. JSTOR 3621846.

- ^ Skilling, John (1976). "Uniform Compounds of Uniform Polyhedra". Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 79 (3): 447–457. Bibcode:1976MPCPS..79..447S. doi:10.1017/S0305004100052440. MR 0397554.

- ^ Hart, George (16–20 July 2019). "Max Brücknerʼs Wunderkammer of Paper Polyhedra" (PDF). In Goldstein, Susan; McKenna, Douglas; Fenyvesi, Kristóf (eds.). Bridges 2019 Conference Proceedings. Linz, Austria: Tessellations Publishing, Phoenix, Arizona. ISBN 9781938664304.

- ^ a b Yackel, Carolyn (26–30 July 2013). "Marking a Physical Sphere with a Projected Platonic Solid" (PDF). In Kaplan, Craig; Sarhangi, Reza (eds.). Proceedings of Bridges 2009: Mathematics, Music, Art, Architecture, Culture. Banff, Alberta, Canada. pp. 123–130. ISBN 9780966520200.

- ^ Popko, Edward S. (2012). Divided Spheres: Geodesics and the Orderly Subdivision of the Sphere. CRC Press. pp. 100–101. ISBN 9781466504295.

- ^ Fuller, Buckimster (1975). Synergetics: Explorations in the Geometry of Thinking. MacMillan Publishing. p. 173. ISBN 9780020653202.

- ^ Marat, Ton (2022). A Ludic Journey into Geometric Topology. Springer. p. 112. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-07442-4. ISBN 9783031074424.

- ^ Bunde, Armin; Havlin, Shlomo (2013). Fractals in Science. Springer. p. 7. ISBN 9783642779534.

- ^ Husain, Sakhlaq (2025). "On Jerusalem Square Fractal, Its Construction and Properties". Annals of Communications in Mathematics. 8 (2): 293–298. doi:10.62072/acm.2025.080211. ISSN 2582-0818.

- ^ Regueiro, Manuel Diaz; Allegue, Luis Diaz (July 7, 2023). "An Algorithm for Extending Menger-type Fractal Structures" (PDF). Hyperseeing: Proceedings of SMI-SCULPT 2023: Shape Modeling International 2023, Shape Creation Using Layouts, Programs, & Technology (SCULPT) Event: Twenty-second Interdisciplinary Conference of the International Society of the Arts, Mathematics, and Architecture (PDF). pp. 55–62. ISBN 9781387733309.

External links

[edit]- Weisstein, Eric W. "Cube". MathWorld.

- Cube: Interactive Polyhedron Model*

- Volume of a cube, with interactive animation

- Cube (Robert Webb's site)

Introduction and Fundamentals

Definition

A cube is defined as a regular hexahedron, a three-dimensional polyhedron consisting of six congruent square faces, twelve edges of equal length, and eight vertices where three faces meet at each.[8] This structure makes it the only regular convex hexahedron, with all faces meeting at right angles.[8] As one of the five Platonic solids, the cube exemplifies a convex polyhedron where all faces are identical regular polygons—specifically squares—and the same number of faces (three) converge at each vertex, ensuring uniformity in its geometric form.[9] These solids, including the cube, are characterized by being equilateral, with all edges of identical length, and equiangular within their faces, adhering to the strict regularity criteria established in Euclidean geometry.[9] The term "cube" originates from the Ancient Greek word kúbos (κύβος), meaning a six-sided die, which entered English through Latin cubus and Old French cube, historically linking the shape to cubic dice used in games.[10] In the context of Euclidean geometry, the cube functions as the foundational three-dimensional analog of the square, representing the extension of a two-dimensional regular polygon into a fully symmetric solid figure.[8]Basic Elements

The cube is composed of six square faces.[8] Each square face is bounded by four edges and contains four vertices. The cube has twelve edges in total.[8] Each edge connects two vertices and is shared by exactly two faces. There are eight vertices on the cube.[8] At each vertex, three edges meet, and three faces are incident.[11] These counts satisfy the Euler characteristic for convex polyhedra: .[12] Each face shares an edge with four other faces, while the remaining face is opposite and non-adjacent.[13] These connectivity relations underpin the cube's octahedral symmetry group.[8]Geometric Properties

Metric Characteristics

The cube is characterized metrically by its edge length , which defines all its primary dimensions as a regular hexahedron with equal edges.[8] Each of the six square faces has an area of , yielding a total surface area of .[8] The volume enclosed by the cube is , representing the space it occupies in three dimensions.[8] The face diagonal, spanning from one vertex to the non-adjacent vertex on the same square face, measures . This length arises from applying the Pythagorean theorem to the right triangle formed by two perpendicular edges of length on the face.[8] The space diagonal, connecting opposite vertices through the cube's interior, has length . To derive this, consider the cube positioned in 3D Cartesian coordinates with vertices at and ; the Euclidean distance is , extending the Pythagorean theorem to three dimensions.[8] The surface-to-volume ratio of highlights scaling effects, where larger cubes become relatively more voluminous compared to their surface, influencing applications in optimization and physics.Associated Spheres

The cube is associated with three principal spheres: the insphere, midsphere, and circumsphere, each defined by tangency or passage through specific elements of the polyhedron. These spheres are centered at the cube's centroid due to its high symmetry. For a cube with side length , the formulas for their radii can be derived using Cartesian coordinates, positioning the cube with its center at the origin and vertices at .[8] The insphere, also known as the inscribed sphere, is tangent to all six faces of the cube at their centroids. The inradius is given by , corresponding to the perpendicular distance from the center to any face, such as the plane . This sphere fits snugly inside the cube, touching each square face at its center point.[8] The midsphere, or intersphere, is tangent to all twelve edges of the cube at their midpoints. The midradius is , calculated as the distance from the center to an edge midpoint, for example, the point on the edge parallel to the z-axis. This configuration highlights the cube's uniform edge lengths and perpendicular face arrangements, enabling such tangency.[8] The circumsphere passes through all eight vertices of the cube. The circumradius is , derived from the Euclidean distance from the center to a vertex like , yielding . These spheres collectively illustrate the cube's geometric harmony, with their centers coinciding along the symmetry axes of the polyhedron.[8]Symmetry Group

The symmetry group of the cube encompasses all isometries that map the cube onto itself, preserving its geometric structure. The rotational symmetry group, consisting of orientation-preserving transformations, has order 24 and is isomorphic to the symmetric group , which permutes the four main space diagonals of the cube.[14] This isomorphism arises because each rotation corresponds to a unique permutation of these diagonals, providing a concrete realization of in three-dimensional space.[15] The full symmetry group, including reflections and other orientation-reversing isometries, has order 48 and is isomorphic to the direct product , where the factor accounts for the inclusion of improper rotations or reflections. The rotational subgroup forms an index-2 normal subgroup within this full group, highlighting the chiral nature of the pure rotations: the cube and its mirror image are enantiomers under rotations alone but become superimposable when reflections are allowed.[16] Orientation-reversing isometries, such as reflections and improper rotations (rotoreflections), reverse the handedness of the object, enabling the full set of 48 symmetries. The rotational symmetries can be classified by their axes and angles. There are three 4-fold rotation axes passing through the centers of opposite faces, supporting rotations of 90°, 180°, and 270° (9 non-identity rotations total). Four 3-fold axes pass through opposite vertices, allowing 120° and 240° rotations (8 rotations). Six 2-fold axes go through the midpoints of opposite edges, each permitting a 180° rotation (6 rotations). Including the identity, these account for the full order of 24.[17] The orientation-reversing symmetries include reflections across nine distinct planes. Three of these planes are parallel to pairs of opposite faces and pass through the cube's center, reflecting the structure across the principal coordinate directions. The remaining six are diagonal planes, each passing through a pair of opposite edges and the center, bisecting the dihedral angles between adjacent faces. These reflections, combined with the rotations, generate the complete symmetry group, with the diagonal planes particularly illustrating the cube's ability to map edges to adjacent positions under mirroring.Constructions

Physical Models

One straightforward method for constructing a physical model of a cube involves folding a paper net, a two-dimensional pattern of six connected squares that unfolds the cube's surfaces. Common configurations include the cross-shaped net, where four squares form a vertical column flanked by one square on each side of the second and third squares from the top, allowing the paper to be cut, creased along edges, and taped or glued into a three-dimensional form. This approach is widely used in educational settings to demonstrate geometric assembly.[18] There are exactly 11 distinct nets for a cube, each valid for folding without overlap, providing varied options for hands-on creation from materials like cardstock.[19] For more robust models, woodworking techniques entail cutting square wooden pieces to an edge length and joining them at right angles using methods such as mitered corners, dowels, or glue to enclose the volume. Softwoods like pine are often selected for ease of cutting and finishing with sandpaper to achieve smooth faces.[20] Similarly, 3D printing enables precise fabrication by modeling a cube with edge length in software, then layering filament or resin additively to build the solid object, commonly used for calibration tests where a 20 mm edge verifies printer accuracy.[21][22] Cubes have long been produced as dice through specialized manufacturing, with ancient examples carved from bone or ivory for uniformity in early gaming and divination practices across Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Greco-Roman cultures.[23] Modern dice are typically molded from plastic or filled resins to ensure balanced weight distribution and numbered faces, allowing mass production of precise 16 mm or larger edge lengths.[24] Dissection puzzles offer an interactive way to assemble a cube from component pieces, as in the Soma cube, where seven irregular polycubes consisting of one piece of three unit cubes and six pieces of four unit cubes each interlock to create a 3×3×3 structure of 27 unit volumes.[25][26] These puzzles emphasize spatial reasoning in physical construction, often using wooden or plastic blocks glued or fitted together. Such assemblies relate briefly to broader polycube models, where unit cubes connect face-to-face to form larger composite shapes.[27]Mathematical Formulations

The unit cube centered at the origin in three-dimensional Euclidean space is defined by its eight vertices, given by all possible combinations of coordinates .[8] This positioning ensures the cube has side length 1 and is symmetric about the coordinate axes, with faces parallel to the coordinate planes.[8] A general cube in Euclidean space can be obtained by applying affine transformations to this unit cube, including translations, rotations, and scalings. An affine transformation is represented as , where is a point on the unit cube, is a invertible matrix encoding linear transformations (such as rotation via orthogonal matrices or scaling via diagonal matrices), and is the translation vector.[28] For example, to position and orient the cube arbitrarily, one first applies a rotation matrix (with ) followed by scaling and translation , yielding the composite and the full map .[29] Edges of the cube can be parameterized using vectors between adjacent vertices. For an edge connecting vertices and , the parametric equation is , where .[29] Faces, being squares, require two parameters: for a face spanned by vectors and from a base vertex , the parameterization is , with .[29] Matrix representations facilitate generating the cube via affine transformations from a single point, such as the origin. Starting from the origin, successive applications of edge vectors along the axes (e.g., , , for a unit cube aligned with axes) produce vertices through combinations like for , then generalized by the affine map to arbitrary position.[28] In the Cartesian coordinate system, an axis-aligned cube serves as the axis-aligned bounding box (AABB) for a set of points, defined by the interval where and bound the extents along each axis, with the cube encompassing all points satisfying , , .[30]Representations

Graph Theory View

In graph theory, the cube's skeleton is represented by the cube graph , which has 8 vertices corresponding to the cube's corners and 12 edges corresponding to its edges; it is a 3-regular graph, with every vertex having degree 3.[31] This graph is bipartite, partitioned into two sets of 4 vertices each, where one set consists of vertices with an even number of adjacent edges in the cube's structure (or even parity in binary labeling), and the other with odd parity.[32] As the 3-dimensional hypercube graph, is defined on the vertex set of all binary strings of length 3, with edges between strings that differ in exactly one position, establishing its isomorphism to the hypercube .[31] The graph admits both Hamiltonian paths and cycles; a Hamiltonian cycle traverses all 8 vertices exactly once before returning to the starting vertex, and such cycles exist in all hypercube graphs including .[33] Shortest path distances in are determined by the Hamming distance between binary labels of vertices, ranging from 1 (adjacent vertices) to 3 (antipodal vertices), with the graph's diameter being 3.[31] The automorphism group of , consisting of all graph isomorphisms from the graph to itself, has order 48; this matches the order of the cube's rotational and reflectional symmetry group.[34] Spectral properties of are captured by its adjacency matrix, a symmetric 8×8 matrix with 0s on the diagonal and 1s for adjacent vertices. The eigenvalues are (multiplicity 1), (multiplicity 3), (multiplicity 3), and (multiplicity 1), reflecting the graph's regularity and bipartiteness.[31]Orthogonal Projections

Orthogonal projections of a cube onto a two-dimensional plane involve mapping the three-dimensional vertices along lines perpendicular to the projection plane, preserving parallelism among edges but potentially obscuring some features due to overlaps. These projections are fundamental in technical drawing and computer graphics for representing the cube without depth distortion from perspective. The appearance varies based on the orientation of the projection direction relative to the cube's axes, faces, edges, or diagonals.[35] In the face-on projection, the direction is aligned with one of the cube's principal axes, perpendicular to a pair of opposite faces, resulting in a square outline on the projection plane. The visible edges form the front square, while the back face and connecting edges are hidden behind it, often indicated by dashed lines in drawings to convey the full structure. For a unit cube centered at the origin with vertices at (\pm 1, \pm 1, \pm 1), projecting onto the xy-plane (direction along the z-axis) simply discards the z-coordinate, yielding the square with vertices at all combinations of (\pm 1, \pm 1)./06%3A_Orthogonality/6.03%3A_Orthogonal_Projection)[36] The edge-on projection occurs when the projection direction is parallel to a face diagonal, such as along the vector (1,1,0) for the xy-face. This yields a rectangular silhouette, with the longer side corresponding to the projected length of edges perpendicular to the direction, and visible diagonals appearing as lines connecting the corners of adjacent faces. Hidden edges include those parallel to the projection direction, which collapse to points. Using the general orthogonal projection matrix where is the unit normal to the plane (or equivalently, the projection direction), for this case with , the matrix is applied to the vertices before extracting 2D coordinates./06%3A_Orthogonality/6.03%3A_Orthogonal_Projection)[37] The vertex-on projection aligns the direction with a space diagonal, such as (1,1,1), producing a regular hexagonal outline formed by the silhouette of three adjacent faces. Internal lines connect opposite vertices, revealing the cube's depth structure without overlaps obscuring the hexagon's regularity. For the unit cube, with , the projection matrix is and applying P to the vertices yields the hexagonal points after coordinate reduction. This projection highlights the cube's threefold rotational symmetry around the diagonal./06%3A_Orthogonality/6.03%3A_Orthogonal_Projection)[36] Unlike perspective projections, where parallel lines converge to vanishing points, strict orthogonal projections maintain all parallel edges as parallel in the 2D image, eliminating depth cues from convergence but introducing no distortion in angles or lengths along the projection direction.[38]Configuration Matrices

The cube realizes a fundamental point-line configuration in incidence geometry, denoted as the (8_3 12_2) configuration, comprising 8 points and 12 lines such that each point is incident with exactly 3 lines and each line contains exactly 2 points. Here, the points correspond to the vertices of the cube, and the lines to its edges, with incidence reflecting the adjacency structure. This incidence structure is formally encoded by the vertex-edge incidence matrix, an 8×12 binary matrix where the rows index the 8 points (vertices), the columns index the 12 lines (edges), and the entry if point lies on line , and 0 otherwise. The row sums of are all 3, reflecting the degree of each vertex, while the column sums are all 2, as each edge connects two vertices; the matrix thus satisfies and , where denotes the all-ones vector of length . The dual configuration interchanges the roles of points and lines, yielding a (12_2 8_3) configuration with 12 points (now the original edges) and 8 lines (the original vertices), where each point is incident with 2 lines and each line contains 3 points. This duality preserves the total number of incidences (24 in both cases) and highlights the symmetric combinatorial properties of the cube's skeleton. Combinatorially, the Levi graph of this configuration—a bipartite graph with 8 vertices on one part (points), 12 on the other (lines), and 24 edges corresponding to incidences—is a (3,2)-regular bipartite graph of girth 6, as the underlying structure admits no two points on multiple lines or two lines through multiple points. This Levi graph relates to the graph-theoretic view of the cube by capturing the full incidence beyond mere vertex adjacency.Related Figures

Dual and Truncations

The dual polyhedron of the cube is the regular octahedron, in which each vertex of the octahedron corresponds to the center of a face on the cube, and each face of the octahedron corresponds to a vertex of the cube.[39] This duality preserves the combinatorial structure, with the cube's 6 faces mapping to the octahedron's 6 vertices and its 8 vertices mapping to the octahedron's 8 triangular faces.[40] Rectification of the cube involves truncating its vertices until they meet at the midpoints of the original edges, yielding the cuboctahedron as the resulting quasiregular polyhedron.[41] The cuboctahedron features 8 equilateral triangular faces from the original vertices and 6 square faces from the original faces, with all edges of equal length and 12 vertices where two triangles and two squares meet alternately.[42] Further truncation of the cube, cutting off vertices to produce regular faces, results in the truncated cube, an Archimedean solid with 8 equilateral triangular faces and 6 regular octagonal faces, 24 vertices, and 36 edges.[43] Each vertex of the truncated cube is surrounded by one triangle and two octagons. In this construction from a cube of side length , the uniform edge length of the truncated cube satisfies .[44] The rhombic dodecahedron arises as the dual of the rectified cube (cuboctahedron) and represents the bitruncated form in the dual truncation sequence of the cube and octahedron.[45] It consists of 12 congruent rhombic faces, with 14 vertices (8 of degree 3 and 6 of degree 4) and 24 edges, and is notable for its role in space-filling tessellations.[46]Compound and Derived Polyhedra

The stella octangula, a regular polyhedral compound consisting of two dual regular tetrahedra interpenetrating each other, represents a key derivation from the cube, as its edges align with the face diagonals of a circumscribed cube.[47] This compound was first described and named by Johannes Kepler in his 1619 work Harmonices Mundi, where he recognized it as a stellation of the regular octahedron and noted its inscription within a cube, highlighting the cube's role in generating such star polyhedra through dual interpenetration.[47] Kepler's construction emphasized the geometric harmony between the cube and its dual octahedron, with the stella octangula emerging as their skeletal intersection in compound form.[48] Derived polyhedra from the cube include uniform polyhedra such as the cuboctahedron, which arises as the rectification of the cube (or equivalently, the convex hull of the cube-octahedron compound), featuring eight triangular and six square faces.[49] Stellating the cuboctahedron yields further compounds, with the first stellation being the cube-octahedron compound itself, where the cube and its dual octahedron share the same center, demonstrating how cube-based derivations extend to Archimedean solids and their star variants.[49] These uniform derivations maintain the cube's octahedral symmetry group while expanding its facial structure, as explored in enumerations of stellated cuboctahedra that preserve regularity.[48] Rhombohedra, particularly golden rhombohedra with edge lengths related by the golden ratio, can be dissected into cubes, illustrating the cube's foundational role in parallelohedral decompositions. For instance, half an obtuse golden rhombohedron combined with half an acute golden rhombohedron dissects into a single cube, a result achieved through planar cuts that align with cubic lattice points.[50] This dissection underscores the cube's utility as a unit in tiling rhombohedral volumes, with applications in quasicrystal modeling where such polyhedra approximate aperiodic structures built from cubic subunits.[50] The cube serves as the isotropic building block for cuboids, which generalize it by allowing unequal edge lengths while retaining right-angled parallelepiped form, thus extending cubic symmetry to rectangular prisms used in crystallographic and architectural contexts. This derivation preserves the cube's topological properties, such as six quadrilateral faces, but introduces anisotropy for practical modeling of volumes in three dimensions.Polycubes and Dissections

Polycubes are three-dimensional polyforms formed by connecting one or more unit cubes face to face along their faces, creating connected solid figures in the cubic lattice. They generalize polyominoes to three dimensions and are classified as fixed, one-sided, or free depending on whether rotations and reflections are considered distinct. Fixed polycubes treat different orientations and mirror images as unique, while one-sided polycubes identify rotations but distinguish reflections, and free polycubes identify both. Connectivity is defined by shared full faces, ensuring the structure is simply connected without holes unless specified otherwise.[51] The basic building blocks include the monomino (a single cube, n=1), the domino or dicube (two cubes, n=2), and the tromino or tricube (three cubes, n=3). For fixed polycubes, there is 1 monomino, 3 dicubes (one along each coordinate axis), and 15 tricubes (3 straight and 12 L-shaped in various orientations). Enumeration of fixed polycubes of size n, denoted A_3(n), is a classic problem in combinatorial geometry, with known values up to n=28 computed using transfer-matrix methods and computer enumeration. The sequence begins 1, 3, 15, 86, 534, 3481 for n=1 to 6, growing asymptotically as approximately 7.20^n. Seminal work on enumeration includes Lunnon's 1972 computations up to n=10 and later extensions by Redelmeier and others using recursive generation algorithms that build polycubes cell by cell while avoiding duplicates via canonical representations.[52] Cube dissections involve dividing a cube into smaller pieces, often polycubes, to form other shapes or solve puzzles, highlighting properties like volume preservation and rigidity. A landmark result is the resolution of Hilbert's third problem, posed in 1900, which asked whether a cube and a regular tetrahedron of equal volume can be dissected into finitely many congruent polyhedral pieces. Max Dehn proved in 1901 that no such dissection exists by introducing the Dehn invariant, a scissors congruence invariant based on edge lengths and dihedral angles in terms of π; the cube has Dehn invariant zero, while the tetrahedron's is nonzero, making them non-dissectible despite equal volumes. This invariant has since been generalized to higher dimensions and used in geometric topology. The Soma cube exemplifies polycube dissections in recreational mathematics. Invented by Piet Hein in 1933 and popularized by Martin Gardner in 1958, it consists of seven irregular polycubes: one tricube and six tetracubes, selected from the 8 free tetracubes to avoid chirality issues. These pieces can be assembled in 240 distinct ways (up to rotation) to form a 3×3×3 cube of volume 27, demonstrating how polycubes enable finite dissections for puzzle design. Physical models of these pieces, often made from wood or plastic, facilitate hands-on exploration of assembly configurations.Tesselations and Honeycombs

The cubic honeycomb is the regular tessellation of three-dimensional Euclidean space by cubes, where each cube shares faces with six adjacent cubes, four cubes meet at each vertex, and four cubes surround each edge.[53] This structure, denoted by the Schläfli symbol {4,3,4}, arises from the natural packing of cubes along orthogonal axes, filling space without gaps or overlaps and achieving a packing density of 1.[54] The dihedral angle of the cube, measuring 90°, facilitates this orthogonal arrangement, allowing cubes to align perfectly at right angles without angular mismatches that would prevent complete space filling.[8] In the context of lattice theory, the Voronoi cell associated with the face-centered cubic lattice—which relates to the dual structure of the cubic honeycomb—is the rhombic dodecahedron, a space-filling polyhedron that partitions space around lattice points.[55] Variations of the cubic honeycomb include the alternated cubic honeycomb, also known as the tetrahedral-octahedral honeycomb, which substitutes cubes with regular tetrahedra and octahedra while maintaining space-filling properties through alternation of the original cubic cells.[56] Another form is the bitruncated cubic honeycomb, composed of truncated octahedra, representing a uniform truncation that preserves the tessellation of space.[57] These variations highlight the cubic honeycomb's role as a foundational regular tessellation from which other uniform honeycombs can be derived via operations like alternation and truncation.Applications

In Mathematics

In number theory, the cube plays a prominent role in the study of sums of cubes, particularly through taxicab numbers, which are positive integers that can be expressed as the sum of two positive cubes in multiple distinct ways. The smallest such nontrivial number is 1729, known as the Hardy–Ramanujan number, satisfying This equality was noted by Srinivasa Ramanujan during a conversation with G. H. Hardy in 1919, highlighting the cube's utility in Diophantine equations involving higher powers.[58] More generally, the search for numbers expressible as sums of cubes connects to Waring's problem, where every natural number can be represented as a sum of at most nine positive cubes, though only finitely many require nine.[58] In group theory, the cube serves as a fundamental domain for certain crystallographic groups, which are discrete subgroups of isometries of Euclidean space preserving a lattice. For instance, specific Bieberbach groups, such as those classifying flat 3-manifolds, admit the cube as a normal fundamental polyhedron, meaning the group action tiles space by translates and rotations of the cube without overlaps or gaps in the interior. This property arises because the cube's symmetry aligns with the group's translational and rotational structure, facilitating the computation of orbifolds and cohomology in geometric group theory.[59] The full symmetry group of the cube, including reflections, is the octahedral group of order 48, isomorphic to , underscoring its role in finite group representations.[16] Topologically, the 3-cube (or unit cube ) provides a standard model for the closed 3-ball, being homeomorphic to the set of points in at distance at most 1 from the origin, with its boundary homeomorphic to the 2-sphere . This equivalence follows from the cube's contractibility and the fact that its boundary consists of six squares glued along edges, forming a spherical surface. In broader contexts, cubes feature in cubical complexes, which parallel simplicial complexes but use hypercubes as building blocks; these are essential in studying CAT(0) spaces and hyperbolic groups, where the cube's combinatorial structure aids in defining nonpositively curved metrics.[60][61] The cube also underlies fractal constructions, notably the Menger sponge, introduced by Karl Menger in 1926 as an example of a space with topological dimension 1 but Hausdorff dimension . Starting from a unit cube subdivided into 27 smaller cubes of side , the construction removes the central cube and the six face-centered cubes iteratively, yielding a porous object with zero volume but infinite surface area in the limit. This iteration demonstrates the cube's role in generating self-similar sets with pathological connectivity, such as being universally curve-like—any continuous curve in 3-space embeds in the sponge.[62] A classic problem involving cube dissections concerns whether a cube can be partitioned into finitely many smaller cubes of unequal sizes. This is impossible, as proved by combinatorial arguments showing that assuming such a dissection leads to a contradiction via infinite descent, where the placement of the smallest cube implies the existence of an even smaller one, highlighting the cube's rigidity in Euclidean dissections compared to 2D analogs like squared squares.[63]In Science and Engineering

In crystallography, the cubic crystal system is one of the seven crystal systems, characterized by a unit cell in the shape of a cube with equal lattice parameters and 90-degree angles between them. This system encompasses three primary Bravais lattices: the simple cubic (primitive cubic), where atoms occupy only the corners of the cube; the body-centered cubic (BCC), with an additional atom at the cube's center; and the face-centered cubic (FCC), featuring atoms at the corners and the centers of each face. These structures determine the packing efficiency and symmetry of crystals, influencing their physical properties.[64][65] In materials science, cubic lattices are prevalent in metals such as iron, which adopts a BCC structure in its alpha phase at room temperature. This arrangement affects mechanical properties like ductility; BCC lattices in metals like iron exhibit fewer slip systems compared to FCC structures, leading to reduced plasticity and higher brittleness under certain conditions, as slip occurs primarily along {110} planes. For instance, alpha-iron's BCC lattice contributes to its moderate ductility, enabling applications in structural engineering while requiring alloying to enhance toughness. FCC metals, such as austenitic stainless steels derived from iron, demonstrate superior ductility due to 12 slip systems, allowing greater deformation without fracture.[66][67] In computing, the Rubik's Cube serves as a practical model for applying group theory to algorithm design, where the cube's configurations form a finite group of order approximately 4.3 × 10^19, generated by face rotations. This structure enables the development of efficient solving algorithms, such as those using commutators and conjugates to manipulate permutations without disrupting solved parts, demonstrating concepts like subgroup generation and coset enumeration in computational puzzle-solving. Additionally, voxel-based 3D modeling represents objects as grids of cubic volume elements (voxels), facilitating simulations in computer graphics and scientific visualization; for example, sparse voxel hierarchies allow efficient rendering of complex scenes by hierarchically organizing cubic data, reducing memory usage for large-scale generative models.[68][69] In engineering, the cubic foot (ft³) is a standard imperial unit for measuring volume, defined as the space occupied by a cube with sides of one foot, commonly used in construction and fluid dynamics to quantify material quantities or capacities, such as concrete pours or HVAC airflow rates. Cubic feet calculations ensure precise scaling in designs, where volume is computed as length × width × height in feet. Dice, typically cubic with six faces, are employed in probability simulations within engineering contexts like reliability testing and Monte Carlo methods; for instance, algorithms simulate dice rolls to model random processes in risk assessment, approximating outcomes such as failure probabilities in systems by generating thousands of iterations to converge on statistical distributions.[70][71] In nanotechnology, cubic quantum dots are semiconductor nanocrystals with cuboidal shapes, typically 5–20 nm in edge length, exhibiting quantum confinement effects that tune their electronic and optical properties for applications in photovoltaics and LEDs. Precision synthesis of deep-blue emitting cubic zinc-blende CdSe quantum dots reveals size-dependent bandgaps, enabling atomistic-level control over emission wavelengths through colloidal methods. Cubic carbon structures, such as nano-cages formed by multiwalled graphitic layers, provide robust scaffolds in nanocomposites, with edges of 20–100 nm offering high surface area for catalysis and energy storage. These structures self-assemble via templating, enhancing mechanical stability in advanced materials.[72][73]Cultural and Everyday Uses