Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

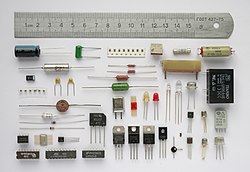

Electronics

View on Wikipedia

Electronics is a scientific and engineering discipline that studies and applies the principles of physics to design, create, and operate devices that manipulate electrons and other electrically charged particles. It is a subfield of physics[1][2] and electrical engineering which uses active devices such as transistors, diodes, and integrated circuits to control and amplify the flow of electric current and to convert it from one form to another, such as from alternating current (AC) to direct current (DC) or from analog signals to digital signals. Electronics is often contrasted with electrical power engineering, which focuses on generation, transmission, and distribution of electric power rather than signal processing or device level control.[3]

Electronic devices have significantly influenced the development of many aspects of modern society, such as telecommunications, entertainment, education, health care, industry, and security. The main driving force behind the advancement of electronics is the semiconductor industry, which continually produces ever-more sophisticated electronic devices and circuits in response to global demand. The semiconductor industry is one of the global economy's largest and most profitable industries, with annual revenues exceeding $481 billion in 2018. The electronics industry also encompasses other branches that rely on electronic devices and systems, such as e-commerce,[citation needed] which generated over $29 trillion in online sales in 2017. Practical electronic systems commonly combine analog and digital techniques, using analog front ends with digital processing.[4]

History and development

[edit]

Karl Ferdinand Braun's development of the crystal detector, the first semiconductor device, in 1874 and the identification of the electron in 1897 by Sir Joseph John Thomson, along with the subsequent invention of the vacuum tube which could amplify and rectify small electrical signals, inaugurated the field of electronics and the electron age.[5][6] Practical applications started with the invention of the diode by Ambrose Fleming and the triode by Lee De Forest in the early 1900s, which made the detection of small electrical voltages, such as radio signals from a radio antenna, practicable. Thermionic vacuum tubes enabled reliable amplification and detection, making long-distance telephony, broadcast radio, and early television feasible by 1920s-1930s.[7]

Vacuum tubes (thermionic valves) were the first active electronic components which controlled current flow by influencing the flow of individual electrons, and enabled the construction of equipment that used current amplification and rectification to give us radio, television, radar, long-distance telephony and much more. The early growth of electronics was rapid, and by the 1920s, commercial radio broadcasting and telecommunications were becoming widespread and electronic amplifiers were being used in such diverse applications as long-distance telephony and the music recording industry.[8]

The next big technological step took several decades to appear, when the first working point-contact transistor was invented by John Bardeen and Walter Houser Brattain at Bell Labs in 1947.[9] The 1947 point contact transistor showed that semiconductors could replace many tube functions with lower power and size.[10] However, vacuum tubes continued to play a leading role in the field of microwave and high power transmission as well as television receivers until the middle of the 1980s.[11] Since then, solid-state devices have all but completely taken over. Vacuum tubes are still used in some specialist applications such as high power RF amplifiers, cathode-ray tubes, specialist audio equipment, guitar amplifiers and some microwave devices.

In April 1955, the IBM 608 was the first IBM product to use transistor circuits without any vacuum tubes and is believed to be the first all-transistorized calculator to be manufactured for the commercial market.[12][13] The 608 contained more than 3,000 germanium transistors. Thomas J. Watson Jr. ordered all future IBM products to use transistors in their design. From that time on transistors were almost exclusively used for computer logic circuits and peripheral devices. However, early junction transistors were relatively bulky devices that were difficult to manufacture on a mass-production basis, which limited them to a number of specialised applications.[14]

The MOSFET was invented at Bell Labs between 1955 and 1960.[15][16][17][18][19][20] It was the first truly compact transistor that could be miniaturised and mass-produced for a wide range of uses.[14] The MOSFET became the most widely used device in VLSI, enabling compact, low power circuits.[21] Its advantages include high scalability,[22] affordability,[23] low power consumption, and high density.[24] The MOSFET's scalability and cost made it dominant in modern electronics.[25] It revolutionized the electronics industry,[26][27] becoming the most widely used electronic device in the world.[28][29] The MOSFET is the basic element in most modern electronic equipment.[30][31] As the complexity of circuits grew, problems arose.[32] One problem was the size of the circuit. A complex circuit like a computer was dependent on speed. If the components were large, the wires interconnecting them must be long. The electric signals took time to go through the circuit, thus slowing the computer.[32] The invention of the integrated circuit by Jack Kilby and Robert Noyce solved this problem by making all the components and the chip out of the same block (monolith) of semiconductor material. The circuits could be made smaller, and the manufacturing process could be automated. This led to the idea of integrating all components on a single-crystal silicon wafer, which led to small-scale integration (SSI) in the early 1960s, and then medium-scale integration (MSI) in the late 1960s, followed by VLSI. In 2008, billion-transistor processors became commercially available.[33] Integrated circuits put many components on one chip, shortening interconnects and increase speed.[25]

Subfields

[edit]Devices and components

[edit]

An electronic component is any component, either active or passive, in an electronic system or electronic device. Components are connected together, usually by being soldered to a printed circuit board (PCB), to create an electronic circuit with a particular function. Components may be packaged singly, or in more complex groups as integrated circuits. Passive electronic components are capacitors, inductors, resistors, whilst active components are such as semiconductor devices; transistors and thyristors, which control current flow at electron level.[34]

Types of circuits

[edit]Electronic circuit functions can be divided into two function groups: analog and digital. A particular device may consist of circuitry that has either or a mix of the two types. Analog circuits are becoming less common, as many of their functions are being digitized.

Analog circuits

[edit]Analog circuits use a continuous range of voltage or current for signal processing, as opposed to the discrete levels used in digital circuits. Analog circuits were common throughout an electronic device in the early years in devices such as radio receivers and transmitters. Analog electronic computers were valuable for solving problems with continuous variables until digital processing advanced.

As semiconductor technology developed, many of the functions of analog circuits were taken over by digital circuits, and modern circuits that are entirely analog are less common; their functions being replaced by hybrid approach which, for instance, uses analog circuits at the front end of a device receiving an analog signal, and then use digital processing using microprocessor techniques thereafter.

Sometimes it may be difficult to classify some circuits that have elements of both linear and non-linear operation. An example is the voltage comparator which receives a continuous range of voltage but only outputs one of two levels as in a digital circuit. Similarly, an overdriven transistor amplifier can take on the characteristics of a controlled switch, having essentially two levels of output.

Analog circuits are still widely used for signal amplification, such as in the entertainment industry, and conditioning signals from analog sensors, such as in industrial measurement and control.

Digital circuits

[edit]Digital circuits are electric circuits based on discrete voltage levels. Digital circuits use Boolean algebra and are the basis of all digital computers and microprocessor devices. They range from simple logic gates to large integrated circuits, employing millions of such gates.

Digital circuits use a binary system with two voltage levels labelled "0" and "1" to indicated logical status. Often logic "0" will be a lower voltage and referred to as "Low" while logic "1" is referred to as "High". However, some systems use the reverse definition ("0" is "High") or are current based. Quite often the logic designer may reverse these definitions from one circuit to the next as they see fit to facilitate their design. The definition of the levels as "0" or "1" is arbitrary.[35]

Ternary (with three states) logic has been studied, and some prototype computers made, but have not gained any significant practical acceptance.[36] Universally, Computers and Digital signal processors are constructed with digital circuits using Transistors such as MOSFETs in the electronic logic gates to generate binary states.

Highly integrated devices:

Design

[edit]Electronic systems design deals with the multi-disciplinary design issues of complex electronic devices and systems, such as mobile phones and computers. The subject covers a broad spectrum, from the design and development of an electronic system (new product development) to assuring its proper function, service life and disposal.[37] Electronic systems design is therefore the process of defining and developing complex electronic devices to satisfy specified requirements of the user.

Due to the complex nature of electronics theory, laboratory experimentation is an important part of the development of electronic devices. These experiments are used to test or verify the engineer's design and detect errors. Historically, electronics labs have consisted of electronics devices and equipment located in a physical space, although in more recent years the trend has been towards electronics lab simulation software, such as CircuitLogix, Multisim, and PSpice.

Computer-aided design

[edit]Today's electronics engineers have the ability to design circuits using premanufactured building blocks such as power supplies, semiconductors (i.e. semiconductor devices, such as transistors), and integrated circuits. Electronic design automation software programs include schematic capture programs and printed circuit board design programs. Popular names in the EDA software world are NI Multisim, Cadence (ORCAD), EAGLE PCB[38] and Schematic, Mentor (PADS PCB and LOGIC Schematic), Altium (Protel), LabCentre Electronics (Proteus), gEDA, KiCad and many others.

Negative qualities

[edit]Thermal management

[edit]Heat generated by electronic circuitry must be dissipated to prevent immediate failure and improve long term reliability. Heat dissipation is mostly achieved by passive conduction/convection. Means to achieve greater dissipation include heat sinks and fans for air cooling, and other forms of computer cooling such as water cooling. These techniques use convection, conduction, and radiation of heat energy.

Noise

[edit]Electronic noise is defined[39] as unwanted disturbances superposed on a useful signal that tend to obscure its information content. Noise is not the same as signal distortion caused by a circuit. Noise is associated with all electronic circuits. Noise may be electromagnetically or thermally generated, which can be decreased by lowering the operating temperature of the circuit. Other types of noise, such as shot noise cannot be removed as they are due to limitations in physical properties.

Packaging methods

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2025) |

Many different methods of connecting components have been used over the years. For instance, early electronics often used point to point wiring with components attached to wooden breadboards to construct circuits. Cordwood construction and wire wrap were other methods used. Most modern-day electronics now use printed circuit boards made of materials such as FR-4 and FR-2. Modern PCBs are usually FR-4 epoxy boards with through hole or surface mount parts.[40] Electrical components are generally mounted to PCBs using through-hole or surface mount.

Health and environmental concerns associated with electronics assembly have gained increased attention in recent years.

Industry

[edit]The electronics industry consists of various branches. The central driving force behind the entire electronics industry is the semiconductor industry,[41] which has annual sales of over $481 billion as of 2018.[42] The largest industry sector is e-commerce,[citation needed] which generated over $29 trillion in 2017.[43] The most widely manufactured electronic device is the metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET), with an estimated 13 sextillion MOSFETs having been manufactured between 1960 and 2018.[44] In the 1960s, U.S. manufacturers were unable to compete with Japanese companies such as Sony and Hitachi who could produce high-quality goods at lower prices. By the 1980s, however, U.S. manufacturers became the world leaders in semiconductor development and assembly.[45]

However, during the 1990s and subsequently, the industry shifted overwhelmingly to East Asia (a process begun with the initial movement of microchip mass-production there in the 1970s), as plentiful, cheap labor, and increasing technological sophistication, became widely available there.[46][47]

Over three decades, the United States' global share of semiconductor manufacturing capacity fell, from 37% in 1990, to 12% in 2022.[47] America's pre-eminent semiconductor manufacturer, Intel Corporation, fell far behind its subcontractor Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) in manufacturing technology.[46]

By that time, Taiwan had become the world's leading source of advanced semiconductors[47][46]—followed by South Korea, the United States, Japan, Singapore, and China.[47][46]

Important semiconductor industry facilities (which often are subsidiaries of a leading producer based elsewhere) also exist in Europe (notably the Netherlands), Southeast Asia, South America, and Israel.[46]

See also

[edit]- Index of electronics articles

- Outline of electronics

- Atomtronics

- Audio engineering

- Biodegradable electronics

- Broadcast engineering

- Computer engineering

- Electronics and Computer Engineering

- Electronics engineering

- Electronics engineering technology

- Fuzzy electronics

- Go-box

- Marine electronics

- Photonics

- Robotics

References

[edit]- ^ française, Académie. "électronique | Dictionnaire de l'Académie française | 9e édition". www.dictionnaire-academie.fr (in French). Retrieved 26 May 2024.

- ^ "Definition of ELECTRONICS". www.merriam-webster.com. 21 May 2024. Retrieved 26 May 2024.

- ^ IEEE. ''IEEE Dictionary of Electrical and Electronics Terms''. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-42806-0

- ^ Brown, Stephen; Vranesic, Zvonko (2008). ''Fundamentals of Digital Logic''. McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-714422-7

- ^ "Urvater der Kommunikationsgesellschaft: Ferdinand Braun – Student und Professor in Marburg – kam vor 150 Jahren zur Welt" [Forefather of the communications society: Ferdinand Braun – student and professor in Marburg – was born 150 years ago] (PDF) (in German). Philipps-Universität Marburg. 17 December 2007. Retrieved 5 September 2025.

- ^ "This Month in Physics History - October 1897: The Discovery of the Electron". American Physical Society. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ Guarnieri, M. (2012). "The age of vacuum tubes: Early devices and the rise of radio communications". IEEE Industrial Electronics Magazine 6 (1): 41–43. doi:10.1109/MIE.2012.2182822.

- ^ Guarnieri, M. (2012). "The age of vacuum tubes: Early devices and the rise of radio communications". IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 6 (1): 41–43. Bibcode:2012IIEM....6a..41G. doi:10.1109/MIE.2012.2182822. S2CID 23351454.

- ^ "1947: Invention of the Point-Contact Transistor". Computer History Museum. Archived from the original on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ "1947: Invention of the Point-Contact Transistor". Computer History Museum. Archived 30 September 2021.

- ^ Sōgo Okamura (1994). History of Electron Tubes. IOS Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-9051991451. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ Bashe, Charles J.; et al. (1986). IBM's Early Computers. MIT. p. 386. ISBN 978-0262022255.

- ^ Pugh, Emerson W.; Johnson, Lyle R.; Palmer, John H. (1991). IBM's 360 and early 370 systems. MIT Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0262161237.

- ^ a b Moskowitz, Sanford L. (2016). Advanced Materials Innovation: Managing Global Technology in the 21st century. John Wiley & Sons. p. 168. ISBN 978-0470508923. Archived from the original on 5 November 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ Huff, Howard; Riordan, Michael (1 September 2007). "Frosch and Derick: Fifty Years Later (Foreword)". The Electrochemical Society Interface. 16 (3): 29. doi:10.1149/2.F02073IF. ISSN 1064-8208.

- ^ Frosch, C. J.; Derick, L (1957). "Surface Protection and Selective Masking during Diffusion in Silicon". Journal of the Electrochemical Society. 104 (9): 547. doi:10.1149/1.2428650.

- ^ Kahng, Dawon (March 1991) [Orig. pub. 1961]. "Silicon-Silicon Dioxide Surface Device". In Sze, Simon Min (ed.). Semiconductor Devices: Pioneering Papers (2nd ed.). World Scientific. pp. 583–596. doi:10.1142/1087. ISBN 978-981-02-0209-5.

- ^ Lojek, Bo (2007). History of Semiconductor Engineering. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. p. 321. ISBN 978-3-540-34258-8.

- ^ Ligenza, J.R.; Spitzer, W.G. (1960). "The mechanisms for silicon oxidation in steam and oxygen". Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids. 14: 131–136. Bibcode:1960JPCS...14..131L. doi:10.1016/0022-3697(60)90219-5.

- ^ Lojek, Bo (2007). History of Semiconductor Engineering. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 120. ISBN 9783540342588.

- ^ Grant, Duncan A.; Gowar, John (1989). Power MOSFETS: Theory and Applications. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-82867-9

- ^ Motoyoshi, M. (2009). "Through-Silicon Via (TSV)". Proceedings of the IEEE. 97 (1): 43–48. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2008.2007462. ISSN 0018-9219. S2CID 29105721.

- ^ "Tortoise of Transistors Wins the Race – CHM Revolution". Computer History Museum. Archived from the original on 10 March 2020. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ "Transistors Keep Moore's Law Alive". EETimes. 12 December 2018. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- ^ a b "The History of the Integrated Circuit". NobelPrize.org. Archived 29 June 2018.

- ^ Chan, Yi-Jen (1992). Studies of InAIAs/InGaAs and GaInP/GaAs heterostructure FET's for high speed applications. University of Michigan. p. 1. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

The Si MOSFET has revolutionized the electronics industry and as a result impacts our daily lives in almost every conceivable way.

- ^ Grant, Duncan Andrew; Gowar, John (1989). Power MOSFETS: theory and applications. Wiley. p. 1. ISBN 978-0471828679. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

The metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET) is the most commonly used active device in the very large-scale integration of digital integrated circuits (VLSI). During the 1970s these components revolutionized electronic signal processing, control systems and computers.

- ^ "Who Invented the Transistor?". Computer History Museum. 4 December 2013. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ Golio, Mike; Golio, Janet (2018). RF and Microwave Passive and Active Technologies. CRC Press. p. 18-2. ISBN 978-1420006728. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ Daniels, Lee A. (28 May 1992). "Dr. Dawon Kahng, 61, Inventor in Field of Solid-State Electronics". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ^ Colinge, Jean-Pierre; Greer, James C. (2016). Nanowire Transistors: Physics of Devices and Materials in One Dimension. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-1107052406. Archived from the original on 17 March 2020. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ a b "The History of the Integrated Circuit". Nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 29 June 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ "Intel to deliver first computer chip with two billion transistors". The Sydney Morning Herald. 5 February 2008. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ Bose, Bimal K, ed. (1996). Power Electronics and Variable Frequency Drives: Technology and Applications. Wiley Online Library. doi:10.1002/9780470547113. ISBN 978-0470547113. S2CID 107126716.

- ^ Brown, Stephen; Vranesic, Zvonko (2008). Fundamentals of Digital Logic (e-book). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0077144227. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ Knuth, Donald (1980). The Art of Computer Programming. Vol. 2: Seminumerical Algorithms (2nd ed.). Addison-Wesley. pp. 190–192. ISBN 0201038226..

- ^ J. Lienig; H. Bruemmer (2017). Fundamentals of Electronic Systems Design. Springer International Publishing. p. 1. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-55840-0. ISBN 978-3319558394.

- ^ "PCB design made easy for every engineer". Autodesk. 19 April 2023. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ IEEE Dictionary of Electrical and Electronics Terms ISBN 978-0471428060

- ^ "PCB design made easy for every engineer". Autodesk. Archived 19 April 2023.

- ^ "Annual Semiconductor Sales Increase 21.6 Percent, Top $400 Billion for First Time". Semiconductor Industry Association. 5 February 2018. Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- ^ "Semiconductors – the Next Wave" (PDF). Deloitte. April 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- ^ "Global e-Commerce sales surged to $29 trillion". United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. 29 March 2019. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ^ "13 Sextillion & Counting: The Long & Winding Road to the Most Frequently Manufactured Human Artifact in History". Computer History Museum. 2 April 2018. Archived from the original on 28 July 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ "Consumer electronics industry in the year 1960s". NaTechnology. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Shih, Willy (Harvard Business School): "Congress Is Giving Billions To The U.S. Semiconductor Industry. Will It Ease Chip Shortages?" Archived 3 July 2023 at the Wayback Machine transcript, August 3, 2022, Forbes, retrieved September 12, 2022

- ^ a b c d Lewis, James Andrew: "Strengthening a Transnational Semiconductor Industry", Archived 13 September 2022 at the Wayback Machine June 2, 2022, Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), retrieved September 12, 2022

Further reading

[edit]- Horowitz, Paul; Hill, Winfield (1980). The Art of Electronics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521370950.

- Mims, Forrest M. (2003). Getting Started in Electronics. Master Publishing, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-945053-28-6.

External links

[edit]- Navy 1998 Navy Electricity and Electronics Training Series (NEETS) Archived 2 November 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- DOE 1998 Electrical Science, Fundamentals Handbook, 4 vols.