Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

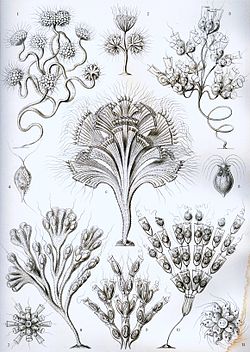

Flagellate

View on Wikipedia

A flagellate is a cell or organism with one or more whip-like appendages called flagella. The word flagellate also describes a particular construction (or level of organization) characteristic of many prokaryotes and eukaryotes and their means of motion. The term presently does not imply any specific relationship or classification of the organisms that possess flagella. However, several derivations of the term "flagellate" (such as "dinoflagellate" and "choanoflagellate") are more formally characterized.[1]

Form and behavior

[edit]Flagella in eukaryotes are supported by microtubules in a characteristic arrangement, with nine fused pairs surrounding two central singlets. These arise from a basal body. In some flagellates, flagella direct food into a cytostome or mouth, where food is ingested. Flagella role in classifying eukaryotes.

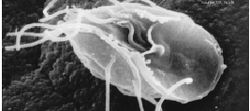

Among protoctists and microscopic animals, a flagellate is an organism with one or more flagella. Some cells in other animals may be flagellate, for instance the spermatozoa of most animal phyla. Flowering plants do not produce flagellate cells, but ferns, mosses, green algae, and some gymnosperms and closely related plants do so.[2] Likewise, most fungi do not produce cells with flagellae, but the primitive fungal chytrids do.[3] Many protists take the form of single-celled flagellates.

Flagella are generally used for propulsion. They may also be used to create a current that brings in food. In most such organisms, one or more flagella are located at or near the anterior of the cell (e.g., Euglena). Often there is one directed forwards and one trailing behind. Many parasites that affect human health or economy are flagellates in at least one stage of life cycle, such as Naegleria, Trichomonas and Plasmodium.[4][5] Flagellates are the major consumers of primary and secondary production in aquatic ecosystems - consuming bacteria and other protists.[citation needed]

Flagellates as specialized cells or life cycle stages

[edit]An overview of the occurrence of flagellated cells in eukaryote groups, as specialized cells of multicellular organisms or as life cycle stages, is given below (see also the article flagellum):[6][7][8]

- Archaeplastida: most green algae (zoospores and male gametes, except in Zygnematophyceae), bryophytes (male gametes), pteridophytes (male gametes), some gymnosperms (cycads and Ginkgo, as male gametes)

- Stramenopiles: centric diatoms (male gametes), brown algae (zoospores and gametes), oomycetes (assexual zoospores and gametes), hyphochytrids (zoospores), labyrinthulomycetes (zoospores), some chrysophytes, some xanthophytes, eustigmatophytes

- Alveolata: some apicomplexans (gametes)

- Rhizaria: some radiolarians (probably gametes),[9] foraminiferans (as gametes)

- Cercozoa: plasmodiophoromycetes (zoospores and gametes), chlorarachniophytes (zoospores)

- Amoebozoa: myxogastrids

- Opisthokonta: most metazoans (male gametes, epithelia and choanocytes), chytrid fungi (zoospores and gametes)

- Excavata: some acrasids (Pocheina, as zoospores)[10]

Flagellates as organisms: the Flagellata

[edit]In older classifications, flagellated protozoa were grouped in Flagellata (= Mastigophora), sometimes divided into Phytoflagellata (= Phytomastigina, mostly autotrophic) and Zooflagellata (= Zoomastigina, heterotrophic). They were sometimes grouped with Sarcodina (ameboids) in the group Sarcomastigophora.

The autotrophic flagellates were grouped similarly to the botanical schemes used for the corresponding algae groups. The colourless flagellates were customarily grouped in three groups, highly artificial:[11]

- Protomastigineae, in which absorption of food-particles in holozoic nutrition occurs at a localised point of the cell surface, often at a cytostome, although many groups were merely saprophytes; it included the majority of colourless flagellates, and even many "apochlorotic" algae;

- Pantostomatineae (or Rhizomastigineae), in which the absorption takes place at any point on the cell surface; roughly corresponds to "amoeboflagellates";

- Distomatineae, a group of binucleate "double individuals" with symmetrically distributed flagella and, in many species, two symmetrical mouths; roughly corresponds to current Diplomonadida.

Presently, these groups are known to be highly polyphyletic. In modern classifications of the protists, the principal flagellated taxa are placed in the following eukaryote groups, which include also non-flagellated forms (where "A", "F", "P" and "S" stands for autotrophic, free-living heterotrophic, parasitic and symbiotic, respectively):[12][13]

- Archaeplastida: volvocids (A/F), prasinophytes (A), glaucophytes (A)

- Stramenopiles: bicosoecids (F), proteromonads (F), opalines (F), most chrysophytes (A/F), part of xanthophytes (A), raphidophytes/chloromonads (A), silicoflagellates (A), ciliophryids (F), pedinellids (A/F)

- Alveolata: dinoflagellates (A/F), Colpodella (F)

- Rhizaria

- Cercozoa: cercomonads (F), spongomonads (F), thaumatomonads (F), glissomonads (F), cryomonads (F), heliomonads/dimorphids (F), ebriids (F)

- Amoebozoa: Multicilia (F), phalansteriids (F), some archamoebae (F/S)

- Opisthokonta: choanoflagellates (F)

- Excavata

- Discoba: jakobids (F), kinetoplastids (bodonids, F/P, trypanosomatids, P), euglenids (F/A), some heteroloboseans (P/F/S)

- Metamonada: diplomonads (P/F), retortamonads (S), Preaxostyla/anaeromonads (oxymonads, S, Trimastix, F, Paratrimastix, F), parabasalids (trichomonads, P/S, hypermastigids, S)

- Eukaryota incertae sedis : haptophytes (F/A), cryptophytes (F/A), kathablepharids (F), Apusozoa (apusomondas, F, ancyromonads, F, spironemids/hemimastigids, F), collodictyonids/diphylleids (F), Phyllomonas (F), and about a hundred genera[14]

Although the taxonomic group Flagellata was abandoned, the term "flagellate" is still used as the description of a level of organization and also as an ecological functional group. Another term used is "monadoid", from monad.[15] as in Monas, and Cryptomonas and in the groups as listed above.

The amoeboflagellates (e.g., the rhizarian genus Cercomonas, some amoebozoan Archamoebae, some excavate Heterolobosea) have a peculiar type of flagellate/amoeboid organization, in which cells may present flagella and pseudopods, simultaneously or sequentially, while the helioflagellates (e.g., the cercozoan heliomonads/dimorphids, the stramenopile pedinellids and ciliophryids) have a flagellate/heliozoan organization.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ Cavalier-Smith T. (1995). "Zooflagellate phylogeny and classification". Tsitologiya. 37 (11): 1010–29. PMID 8868448.

- ^ Philip E. Pack, Ph.D., Cliff's Notes: AP Biology 4th edition.

- ^ Hibbett; et al. (2007). "A higher-level phylogenetic classification of the Fungi". Mycologia. 111 (5): 509–547. doi:10.1016/j.mycres.2007.03.004. PMID 17572334. S2CID 4686378.

- ^ Dash, Manoswini; Sachdeva, Sherry; Bansal, Abhisheka; Sinha, Abhinav (2022-06-15). "Gametogenesis in Plasmodium: Delving Deeper to Connect the Dots". Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 12 877907. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2022.877907. ISSN 2235-2988. PMC 9241518. PMID 35782151.

- ^ Sparagano, O.; Drouet, E.; Brebant, R.; Manet, E.; Denoyel, G. A.; Pernin, P. (1993). "Use of monoclonal antibodies to distinguish pathogenic Naegleria fowleri (cysts, trophozoites, or flagellate forms) from other Naegleria species". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 31 (10): 2758–2763. doi:10.1128/jcm.31.10.2758-2763.1993. ISSN 0095-1137. PMC 266008. PMID 8253977.

- ^ Raven, J.A. 2000. The flagellate condition. In: (B.S.C. Leadbeater and J.C. Green, eds) The flagellates. Unity, diversity and evolution. The Systematics Association Special Volume 59. Taylor and Francis, London. pp. 269–287.

- ^ Webster, J & Weber, R (2007). Introduction to Fungi (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 23–24, [1]

- ^ Adl et al. (2012).

- ^ Lahr DJ, Parfrey LW, Mitchell EA, Katz LA, Lara E (July 2011). The chastity of amoebae: re-evaluating evidence for sex in amoeboid organisms. Proc. Biol. Sci. 278 (1715): 2083–6.

- ^ Tice, Alexander (2015). Understanding the evolution of aggregative multicellularity : a molecular phylogenetic study of the cellular slime mold genera sorodiplophrys and pocheina. University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. ISBN 978-1-321-68823-8. OCLC 985464464.

- ^ Fritsch, F.E. The Structure and Reproduction of the Algae. Vol. I. Introduction, Chlorophyceae. Xanthophyceae, Chrysophyceae, Bacillariophyceae, Cryptophyceae, Dinophyceae, Chloromonadineae, Euglenineae, Colourless Flagellata. 1935. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, [2].

- ^ Jeuck, Alexandra; Arndt, Hartmut (2013). "A Short Guide to Common Heterotrophic Flagellates of Freshwater Habitats Based on the Morphology of Living Organisms". Protist. 164 (6): 842–860. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2013.08.003. PMID 24239731.

- ^ Patterson, D.J. (2000). Flagellates: Heterotrophic Protists With Flagella. Tree of Life, [3].

- ^ Patterson, D.J., Vørs, N., Simpson, A.G.B. & O'Kelly, C., 2000. Residual Free-living and Predatory Heterotrophic Flagellates. In: Lee, J.J., Leedale, G.F. & Bradbury, P. An Illustrated Guide to the Protozoa. Society of Protozoologists/Allen Press: Lawrence, Kansas, U.S.A, 2nd ed., vol. 2, p. 1302–1328, [4].

- ^ Hoek, C. van den, Mann, D.G. and Jahns, H.M. (1995). Algae An Introduction to Phycology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-30419-9.

- ^ Mikryukov, K.A. (2001). Heliozoa as a component of marine microbenthos: a study of Heliozoa of the White Sea. Ophelia 54: 51–73.

External links

[edit]- Flagellata at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Leadbeater, B.S.C. & Green, J.C., eds. (2000). The Flagellates. Unity, diversity and evolution. Taylor and Francis, London.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.