Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Protist

View on Wikipedia

| Protists Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Examples of protists. Clockwise from top left: red algae, kelp, ciliate, golden alga, dinoflagellate, metamonad, amoeba, slime mold. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Major subdivisions[2] | |

| Cladistically included but traditionally excluded taxa | |

| |

A protist (/ˈproʊtɪst/ PROH-tist) or protoctist is any eukaryotic organism that is not an animal, land plant, or fungus. Protists do not form a natural group, or clade, but are a paraphyletic grouping of all descendants of the last eukaryotic common ancestor excluding land plants, animals, and fungi.

Protists were historically regarded as a separate taxonomic kingdom known as Protista or Protoctista. With the advent of phylogenetic analysis and electron microscopy studies, the use of Protista as a formal taxon was gradually abandoned. In modern classifications, protists are spread across several eukaryotic clades called supergroups, such as Archaeplastida (photoautotrophs that includes land plants), SAR, Obazoa (which includes fungi and animals), Amoebozoa and "Excavata".

Protists represent an extremely large genetic and ecological diversity in all environments, including extreme habitats. Their diversity, larger than for all other eukaryotes, has only been discovered in recent decades through the study of environmental DNA and is still in the process of being fully described. They are present in all ecosystems as important components of the biogeochemical cycles and trophic webs. They exist abundantly and ubiquitously in a variety of mostly unicellular forms that evolved multiple times independently, such as free-living algae, amoebae and slime moulds, or as important parasites. Together, they compose an amount of biomass that doubles that of animals. They exhibit varied types of nutrition (such as phototrophy, phagotrophy or osmotrophy), sometimes combining them (in mixotrophy). They present unique adaptations not present in multicellular animals, fungi or land plants. The study of protists is termed protistology.

Definition

[edit]

Protists are a diverse group of eukaryotes that are primarily single-celled and microscopic and exhibit a wide variety of shapes and life strategies. They have different life cycles, trophic levels, modes of locomotion, and cellular structures.[4][5] Although most protists are unicellular, there is a considerable range of multicellularity amongst them; some form colonies or multicellular structures visible to the naked eye. The term 'protist' refers to all eukaryotes that are not animals, land plants or fungi, the three traditional eukaryotic kingdoms.[a][13] Because of this definition by exclusion, protists compose a paraphyletic group that includes the ancestors of those three kingdoms.[14]

The names of some protists (called ambiregnal protists), because of their mixture of traits similar to both animals and land plants or fungi (e.g., slime molds and flagellated algae like euglenids), have been published under either or both of the botanical (ICNafp) and the zoological (ICZN) codes of nomenclature.[15][16]

Common types

[edit]Protists display a wide range of distinct morphological types that have been used to classify them for practical purposes, although most of these categories do not represent evolutionary cohesive lineages or clades and have instead evolved independently several times. The most recognizable types are:[17]

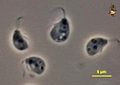

- Amoebae. Characterized by their irregular, flexible shapes, these protists move by extending portions of their cytoplasm, known as pseudopodia, to crawl along surfaces.[18] Many groups of amoebae are naked, but testate amoebae and foraminifera grow a shell around their cell made from digested material or surrounding debris. Some, known as radiolarians and heliozoans, have special spherical shapes with microtubule-supported pseudopodia radiating from the cell.[17] Some amoebae are capable of producing stalked multicellular stages that bear spores, often by aggregating together; these are known as slime molds.[19] The main clades containing amoebae are Amoebozoa (including various slime molds and testate amoebae) and Rhizaria (including famous groups such as foraminifera and radiolarians, as well as a few testate amoebae).[20][21] Even some individual amoebae can grow to giant sizes visible to the naked eye.[22][23]

- Flagellates. These protists are equipped with one or more whip-like appendages called cilia, undulipodia or eukaryotic flagella,[b] which enable them to swim or glide freely through the environment. Flagellates are found in all lineages, reflecting that the common ancestor of all living eukaryotes was a flagellate. They usually exhibit two cilia (e.g., in Provora, Telonemia, Stramenopiles, Alveolata, Obazoa and most excavates), but there are a number of flagellate groups with a high number of cilia (such as Hemimastigophora and other excavates).[17] Some groups, such as the well-known ciliates and the parasitic opalinids, have a cell surface covered in rows of cilia that beat rhythmically. A few groups of amoebae have retained their flagella, making them amoeboflagellates.[27]

- Algae. They are the photosynthetic protists, and can be found in most of the main clades, completely intermingled with heterotrophic protists which are traditionally called protozoa.[28] Algae exhibit the most diverse range of morphologies, from single flagellated or coccoid cells (e.g., cryptophytes, haptophytes, dinoflagellates, chromerids, many green algae, ochrophytes, euglenophytes) to amoeboid cells (chlorarachniophytes) to colonial and multicellular macroscopic forms (e.g., red algae, some green algae, and some ochrophytes such as kelp).[29]

- Fungus-like protists. Several clades of protists have evolved an appearance similar to fungi through hyphae-like structures and a saprophytic nutrition. They have evolved multiple times, often very distantly from true fungi (e.g., the oomycetes, labyrinthulomycetes and hyphochytrids, in Stramenopiles; the myxomycetes, in Amoebozoa; the phytomyxeans, in Rhizaria; the perkinsozoans, in Alveolata).[30][31]

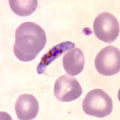

- Sporozoa. This category traditionally included parasitic protists that reproduced via spores (the apicomplexans, microsporidians, myxozoans and ascetosporeans).[6] Its current use is restricted to the apicomplexans,[32] such as Plasmodium falciparum, the cause of malaria.[33]

Diversity

[edit]

The species diversity of protists is severely underestimated by traditional methods that differentiate species based on morphological characteristics. The number of described protist species is very low (ranging from 26,000[35] to over 76,000)[c] in comparison to the diversity of land plants, animals and fungi, which are historically and biologically well-known and studied. The predicted number of species also varies greatly, ranging from 140,000 to 1,600,000, and in several groups the number of predicted species is arbitrarily doubled. Most of these predictions are highly subjective. Molecular techniques such as environmental DNA barcoding have revealed a vast diversity of undescribed protists that accounts for the majority of eukaryotic sequences or operational taxonomic units (OTUs), dwarfing those from land plants, animals and fungi.[34] As such, it is considered that protists dominate eukaryotic diversity.[37]

| Protist phylogeny |

| One possible topology for the eukaryotic tree of life, with uncertain positions of ancyromonads, excavates, provorans and hemimastigotes.[38][3][39][40] Excavate groups are shown in green. 1Includes land plants. 2Includes animals and fungi. |

The evolutionary relationships of protists have been explained through molecular phylogenetics, the sequencing of entire genomes and transcriptomes, and electron microscopy studies of the flagellar apparatus and cytoskeleton. New major lineages of protists and novel biodiversity continue to be discovered, resulting in dramatic changes to the eukaryotic tree of life. The newest classification systems of eukaryotes do not recognize the formal taxonomic ranks (kingdom, phylum, class, order...) and instead only recognize clades of related organisms, making the classification more stable in the long term and easier to update. In this new cladistic scheme, the protists are divided into various branches informally named supergroups. Most photosynthetic eukaryotes fall under the Diaphoretickes clade, which contains the supergroups Archaeplastida (which includes land plants) and SAR (including, Stramenopiles, Alveolata and Rhizaria), as well as the phyla Telonemia, Cryptista and Haptista.[17][41] The animals and fungi fall into the Amorphea supergroup, which contains the phylum Amoebozoa and several other protist lineages. Various groups of eukaryotes with primitive cell architecture are collectively known as the "Excavata".[2]

"Excavata"

[edit]"Excavata" is a group that encompasses diverse protists, mostly flagellates, ranging from aerobic and anaerobic predators to phototrophs and heterotrophs.[42]: 597 The common name 'excavate' refers to the common characteristic of a ventral groove in the cell used for suspension feeding, which is considered to be an ancestral trait present in the last eukaryotic common ancestor.[43] The "Excavata" is composed of three clades: Discoba, Metamonada and Malawimonadida, each including 'typical excavates' that are free-living phagotrophic flagellates with the characteristic ventral groove.[44] According to most phylogenetic analyses, this group is paraphyletic,[40] with some analyses placing the root of the eukaryote tree within Metamonada.[45]

Discoba includes three major groups: Jakobida, Euglenozoa and Percolozoa.[d] Jakobida are a small group (~20 species) of free-living heterotrophic flagellates, with two cilia, that primarily eat bacteria through suspension feeding; most are aquatic aerobes, with some anaerobic species, found in marine, brackish or fresh water.[47] They are best known for their bacterial-like mitochondrial genomes.[17] Euglenozoa is a rich (>2,000 species)[48] group of flagellates with very different lifestyles, including: the free-living heterotrophic (both osmo- and phagotrophic)[42] and photosynthetic euglenids (e.g., the euglenophytes, with chloroplasts originated from green algae); the free-living and parasitic kinetoplastids (such as Trypanosoma); the deep-sea anaerobic symbiontids; and the elusive diplonemids.[49] Percolozoa[d] (~150 species) are a collection of amoebae, flagellates and amoeboflagellates with complex life cycles, among which are some slime molds (acrasids).[17][46] The two clades Euglenozoa and Percolozoa are sister taxa, united under the name Discicristata, in reference to their mitochondrial cristae shaped like discs.[9] The species Tsukubamonas globosa is a free-living flagellate whose precise position within Discoba is not yet settled, but is probably more closely related to Discicristata than to Jakobida.[47]

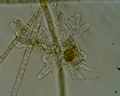

The metamonads (Metamonada) are a phylum of completely anaerobic or microaerophilic protozoa, primarily flagellates. Some are gut symbionts of animals such as termites, others are free-living, and others are parasitic. They include three main clades: Fornicata, Parabasalia and Preaxostyla.[17] Fornicata (>140 species)[36] encompasses the diplomonads, with two nuclei (e.g., Giardia), and several smaller groups of free-living, commensal and parasitic protists (e.g., Carpediemonas, retortamonads).[17] Parabasalia (>460 species)[36] is a varied group of anaerobic, mostly endobiotic organisms, ranging from small parasites (like Trichomonas) to giant intestinal symbionts with numerous flagella and nuclei found in wood-eating termites and cockroaches.[17] Preaxostyla (~140 species) includes the anaerobic and endobiotic oxymonads, with modified (or completely lost)[50][51] mitochondria, and two genera of free-living microaerophilic bacterivorous flagellates Trimastix and Paratrimastix, with typical excavate morphology.[51][52] Two genera of anaerobic flagellates of recent description and unique cell architecture, Barthelona and Skoliomonas, are closely related to the Fornicata.[53]

The malawimonads (Malawimonadida) are a small group (three species) of freshwater or marine suspension-feeding bacterivorous flagellates[54] with typical excavate appearance, closely resembling Jakobida and some metamonads but not phylogenetically close to either in most analyses.[17]

-

Giardia, a genus of intestinal parasites that cause giardiasis

-

Trichomonas vaginalis, the causative agent of trichomoniasis

-

Trypanosoma cruzi, the causative agent of Chagas disease

-

Euglena, a genus of photosynthetic euglenids

-

Malawimonas cells, with typical excavate architecture

Diaphoretickes

[edit]Diaphoretickes includes nearly all photosynthetic eukaryotes. The SAR supergroup gathers a colossal diversity of protists. It includes Stramenopiles, Alveolata and Rhizaria.[55] Another highly diverse clade within Diaphoretickes is Archaeplastida, which houses land plants and a variety of algae. In addition, three smaller groups, Telonemia, Haptista and Cryptista, also belong to Diaphoretickes.[2] TSAR is a possible clade that would comprise Telonemia and SAR,[56] although Telonemia may branch with Haptista instead of SAR.[57][58] Telonemia shares some cellular similarities with the SAR supergroup.[55]

Stramenopiles

[edit]The stramenopiles, also known as Heterokonta, are characterized by the presence of two cilia, one of which bears many short, straw-like hairs (mastigonemes). They include one clade of phototrophs and numerous clades of heterotrophs, present in virtually all habitats. Stramenopiles include two usually well-supported clades, Bigyra and Gyrista, although the monophyly of Bigyra is being questioned.[59] Branching outside both Bigyra and Gyrista is a single species of enigmatic heterotrophic flagellates, Platysulcus tardus.[59] Much of the diversity of heterotrophic stramenopiles is still uncharacterized, known almost entirely from lineages of genetic sequences known as MASTs (MArine STramenopiles),[59] of which only a few species have been described.[60][61]

The phylum Gyrista includes the photosynthetic Ochrophyta or Heterokontophyta (>23,000 species),[48] which contain chloroplasts originated from a red alga. Among these are many lineages of algae that encompass a wide range of structures and morphologies. The three most diverse ochrophyte classes are: the diatoms, unicellular or colonial organisms encased in silica cell walls (frustules) that exhibit widely different shapes and ornamentations and comprise much of the marine phytoplankton;[17][62] the brown algae, filamentous or 'truly' multicellular (with differentiated tissues) macroalgae that constitute the basis of many temperate and cold marine ecosystems, such as kelp forests;[63] and the golden algae, unicellular or colonial flagellates that are mostly present in freshwater habitats.[64] Inside Gyrista, the sister clade to Ochrophyta are the predominantly osmotrophic and filamentous pseudofungi (>1,200 species),[65] which include three distinct lineages: the parasitic oomycetes or water moulds (e.g., Phytophthora), which encompass most of the pseudofungi species; the less diverse non-parasitic hyphochytrids that maintain a fungus-like lifestyle; and the bigyromonads, a group of bacterivorous or eukaryovorous phagotrophs.[59] A small group of heliozoan-like heterotrophic amoebae, Actinophryida, has an uncertain position, either within or as the sister taxon of Ochrophyta.[66]

The little studied phylum Bigyra is an assemblage of exclusively heterotrophic organisms, most of which are free-living. It includes the labyrinthulomycetes, among which are single-celled amoeboid phagotrophs, mixotrophs, and fungus-like filamentous heterotrophs that create slime networks to move and absorb nutrients, as well as some parasites and a few testate amoebae (Amphitremida). Also included in Bigyra are the bicosoecids, phagotrophic flagellates that consume bacteria, and the closely related Placidozoa, which consists of several groups of heterotrophic flagellates (e.g., the deep-sea halophilic Placididea) as well as the intestinal commensals known as Opalinata (e.g., the human parasite Blastocystis, and the highly unusual opalinids, composed of giant cells with numerous nuclei and cilia, originally misclassified as ciliates).[59]

-

Macrocystis pyrifera, the giant kelp

-

Cafeteria, a genus of bicosoecids

-

Opalina cell covered in numerous rows of cilia

Alveolata

[edit]The alveolates (Alveolata) are characterized by the presence of cortical alveoli, cytoplasmic sacs underlying the cell membrane of unknown physiological function.[42]: 599 Among them are three of the most well-known groups of protists: apicomplexans, dinoflagellates and ciliates. The ciliates (Ciliophora) are a highly diverse (>8,000 species) and probably the most thoroughly studied[17] group of protists. They are mostly free-living microbes characterized by large cells covered in rows of cilia and containing two kinds of nuclei, micronucleus and macronucleus. Free-living ciliates are usually the top heterotrophs and predators in microbial food webs, feeding on bacteria and smaller eukaryotes, present in a variety of ecosystems, although a few species are kleptoplastic. Others are parasitic of numerous animals.[67] Ciliates have a basal position in the evolution of alveolates, together with a few species of heterotrophic flagellates with two cilia collectively known as colponemids.[68]

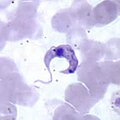

The remaining alveolates are grouped under the clade Myzozoa, whose common ancestor acquired chloroplasts through a secondary endosymbiosis from a red alga.[69] One branch of Myzozoa contains the apicomplexans and their closest relatives, a small clade of flagellates known as Chrompodellida where phototrophic and heterotrophic flagellates, called chromerids and colpodellids respectively, are evolutionarily intermingled.[69] In contrast, the apicomplexans (Apicomplexa) are a large (>6,000 species) and highly specialized group of obligate parasites who have all secondarily lost their photosynthetic ability (e.g., Plasmodium). Their adult stages absorb nutrients from the host through the cell membrane, and they reproduce between hosts via sporozoites, which exhibit an organelle complex (the apicoplast) evolved from non-photosynthetic chloroplasts.[70][42]: 600

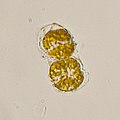

The other branch of Myzozoa contains the dinoflagellates and their closest relatives, the perkinsids (Perkinsozoa), a small group (26 species) of aquatic intracellular parasites which have lost their photosynthetic ability similarly to apicomplexans.[69] They reproduce through flagellated spores that infect dinoflagellates, molluscs and fish.[71] In contrast, the dinoflagellates (Dinoflagellata) are a highly diversified (~4,500 species)[72] group of aquatic algae that have mostly retained their chloroplasts, although many lineages have lost their own and instead either live as heterotrophs or reacquire new chloroplasts from other sources, including tertiary endosymbiosis and kleptoplasty.[73] Most dinoflagellates are free-living and compose an important portion of phytoplankton, as well as a major cause of harmful algal blooms due to their toxicity; some live as symbionts of corals, allowing the creation of coral reefs. Dinoflagellates exhibit a diversity of cellular structures, such as complex eyelike ocelli, specialized vacuoles, bioluminescent organelles, and a wall surrounding the cell known as the theca.[72]

-

Paramecium, a well-studied genus of ciliates[74]

-

Vitrella brassicaformis, a photosynthetic chromerid, relative of apicomplexans

-

Plasmodium falciparum, the causative agent of malaria, infecting blood cells

-

Dinovorax, a perkinsid that infects dinoflagellates

-

Alexandrium dinoflagellates, responsible for certain harmful algal blooms

Rhizaria

[edit]Rhizaria is a lineage of morphologically diverse organisms, composed almost entirely of unicellular heterotrophic amoebae, flagellates and amoeboflagellates,[17] commonly with reticulose (net-like) or filose (thread-like) pseudopodia for feeding and locomotion.[75][42]: 604 It was the last supergroup to be described, because it lacks any defining characteristic and was discovered exclusively through molecular phylogenetics.[76] Three major clades are included, namely the phyla Cercozoa, Endomyxa and Retaria.[2]

Retaria contains the most familiar rhizarians: forams and radiolarians, two groups of large free-living marine amoebae with pseudopodia supported by microtubules, many of which are macroscopic.[17] The radiolarians (Radiolaria) are a diverse group (>1,000 living species) of amoebae, often bearing delicate and intricate siliceous skeletons.[77] The forams (Foraminifera) are also diverse (>6,700 living species),[78] and most of them are encased in multichambered tests constructed from calcium carbonate or agglutinated mineral particles.[17] Both groups have a rich fossil record, with tens of thousands of described fossil species.[78][79]

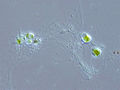

Cercozoa (also known as Filosa) is an assemblage of free-living protists with very different morphologies. Cercozoan amoeboflagellates are important predators of other microbes in terrestrial habitats and the plant microbiota (e.g., cercomonads and paracercomonads and glissomonads, collectively known as class SARcomonadea),[80] and a few can generate slime molds (e.g., Helkesea).[81] Many cercozoans are testate or scale-bearing amoebae, namely the elusive Kraken and the two classes Imbricatea (e.g., the euglyphids) and Thecofilosea.[80] Thecofilosea also contains the Phaeodaria (~400–500 species), a group of skeleton-bearing marine amoebae previously classified as radiolarians,[79] and both classes include some non-scaly naked flagellates (e.g., spongomonads in Imbricatea and thaumatomonads in Thecofilosea).[82] Among the basal-branching cercozoans are the pseudopodia-lacking thecate flagellates of Metromonadea, the heliozoan-like Granofilosea[82] and the photosynthetic chlorarachniophytes, whose chloroplasts originated from a secondary endosymbiosis with a green alga.[17]

Endomyxa contains two major clades of parasitic protists: Ascetosporea are sporozoan-type parasites of marine invertebrates,[83] while Phytomyxea are obligate pathogens of plants and algae, divided into the terrestrial plasmodiophorids and the marine phagomyxids.[84] Also included in Endomyxa are the order of predatory amoebae Vampyrellida (48 species)[85] and two genera of marine amoebae, the thecate Gromia and the naked Filoreta.[2]

Besides these three phyla, Rhizaria includes numerous enigmatic and understudied lineages of uncertain evolutionary position. One such clade is the Gymnosphaerida, which includes heliozoan-type protists.[86] Several clades labeled as Novel Clades (NC) are entirely composed of environmental DNA from uncultured protists, although a few have slowly been resolved over the decades with the description of new taxa (e.g., Tremulida and Aquavolonida, formerly NC11 and NC10 respectively, with a deep-branching position in Rhizaria).[87]

-

Globorotalia, a genus of forams visible to the naked eye

-

Cladococcus cell, showing the intricate radiolarian skeleton

-

Chlorarachnion, a genus of photosynthetic cercozoans

-

Euglypha, a prominent genus of testate amoebae

-

Haplosporidium species infect a variety of invertebrates

Haptista and Cryptista

[edit]Haptista and Cryptista are two similar phyla of single-celled protists previously thought to be closely related, and collectively known as Hacrobia.[88] However, the monophyly of Hacrobia was disproven, as the two groups originated independently.[89] Molecular analyses place Cryptista next to Archaeplastida, forming the hypothesized CAM clade,[39] and Haptista next to the Telonemia and the SAR clade[40] (Telonemia may either be the sister group to SAR, forming the hypothesized TSAR clade,[90] or to Haptista, forming a common sister clade to SAR[91][39][92]). Within the CAM clade, the closest relative of Cryptista is the species Microheliella maris, together composing the clade Pancryptista.[39]

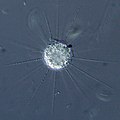

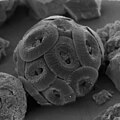

The phylum Haptista includes two distinct clades with mineralized scales: haptophytes and centrohelids.[17] The haptophytes (Haptophyta) are a group of over 500 living species[48] of flagellated or coccoid algae that have acquired chloroplasts from a secondary endosymbiosis. They are mostly marine, comprise an important portion of oceanic plankton, and include the coccolithophores, whose calcified scales ('coccoliths') contribute to the formation of sedimentary rocks and the biogeochemical cycles of carbon and calcium. Some species are capable of forming toxic blooms.[93] The centrohelids (Centroplasthelida) are a small (~95 species)[94] but widespread group of heterotrophic heliozoan-type amoebae, usually covered in scale-bearing mucous, that form an important component of benthic food webs of aquatic habitats, both marine and freshwater.[95]

The phylum Cryptista is a clade of three distinct groups of unicellular protists: cryptomonads, katablepharids, and the species Palpitomonas bilix.[2] The cryptomonads (>100 species), also known as cryptophytes, are flagellated algae found in aquatic habitats of diverse salinity, characterized by extrusive organelles or extrusomes called ejectisomes. Their chloroplasts, of red algal origin, contain a nucleomorph, a remnant of the eukaryotic nucleus belonging to the endosymbiotic red alga.[96] The katablepharids, the closest relatives of cryptomonads, are heterotrophic flagellates with two cilia, also characterized by ejectisomes.[88][2] The species Palpitomonas bilix is the most basal-branching member of Cryptista, a marine heterotrophic flagellate with two cilia, but unlike the remaining members it lacks ejectisomes.[97]

-

Raphidiophrys, a centrohelid heliozoan

-

Coccolithophore covered in coccoliths

-

Cryptomonas, common algae in fresh waters worldwide

-

Roombia truncata, filled with rows of ejectisomes

Archaeplastida

[edit]Archaeplastida is the clade containing those photosynthetic groups whose plastids were likely obtained through a single event of primary endosymbiosis with a cyanobacterium. It contains land plants (Embryophyta) and a big portion of the diversity of algae, most of which are the green algae, from which plants evolved, and the red algae.[98] A third lineage of algae, the glaucophytes (25 species),[48] contains rare and obscure species found in surfaces of freshwater and terrestrial habitats.[98]

The red algae or Rhodophyta (>7,100 species) are a group of diverse morphologies, ranging from single cells to multicellular filaments to giant pseudoparenchymatous thalli, all without flagella. They lack chlorophyll and only harvest light energy through phycobiliproteins. Their life cycles are varied and may include two or three generations. They are present in terrestrial, freshwater and primarily marine habitats, from the intertidal zone to deep waters; some are calcified and are vital components of marine ecosystems such as coral reefs.[99] Closely related to the red algae are two small lineages of non-photosynthetic predatory flagellates: the freshwater and marine Rhodelphidia (3 species),[100] which still retain genetic evidence of relic plastids;[101] and the marine Picozoa (1 species), which lack any remains of plastids. The evolutionary position of Picozoa may indicate that there have been two separate events of primary endosymbiosis, as opposed to one.[102]

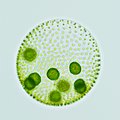

The green algae, unlike the monophyletic glaucophytes and rhodophytes, are a paraphyletic group from which land plants evolved. Together they compose the Chloroplastida or Viridiplantae clade.[2] The earliest branching member is the phylum Prasinodermophyta (ten species), whose members are exclusively marine coccoid cells or small macroscopic thalli.[103] The remaining green algae are distributed in two major clades. One clade is the phylum Chlorophyta (>7,900 species),[48] which includes numerous lineages of scaly unicellular flagellate algae known collectively as prasinophytes along with the Prasinodermophyta, but also includes a variety of morphologies such as coccoids, palmelloids, colonies, and macroscopic filamentous, foliose or tubular thalli, present in aquatic and terrestrial habitats.[2] The opposed clade is Streptophyta, which contains the land plants and a paraphyletic group of green algae collectively known as phylum Charophyta, composed of several classes: Zygnematophyceae (>4,300 species),[48] containing unicellular, colonial and filamentous flagella-lacking organisms found almost exclusively in freshwater habitats;[104] Charophyceae (450 living species),[48] also known as stoneworts, consisting of complex multicellular thalli only found in freshwater habitats;[105] Klebsormidiophyceae (52 species), with unbranched filamentous thalli; Coleochaetophyceae (36 species), containing branched filamentous thalli; Mesostigmatophyceae, composed of a single species of scaly flagellates; and Chlorokybophyceae (five species), with sarcinoid forms.[106][48]

-

Cyanophora, a glaucophyte genus

-

Corallina officinalis, a coralline red alga

-

Volvox, a colonial chlorophyte

-

Spirogyra, a filamentous streptophyte, during conjugation

-

Chara, a complex plant-like streptophyte with reproductive structures

Amorphea

[edit]Amorphea is a group of exclusively heterotrophic organisms. It contains the fungi and animals, as well as most slime moulds, many amoebae and some flagellates.[107] Many of its protist members exhibit complex life cycles with different levels of multicellularity.[108] Amorphea is roughly equivalent to the concept of 'unikonts', meaning 'single cilium', although it currently contains several organisms with more cilia.[109] It is defined as the smallest clade containing the groups Amoebozoa (containing mostly slime moulds and amoebae) and Opisthokonta (containing fungi, animals, and their closest relatives).[107][2] The closest relatives of Opisthokonta are two small lineages of single-celled protists with two cilia: the flagellate Apusomonadida (28 species)[110] and the amoeboflagellate anaerobic Breviatea (four species).[17] Together with opisthokonts, these two groups form the clade Obazoa, the sister clade to Amoebozoa.[109]

The phylum Amoebozoa (2,400 species)[34] is a large group of morphologically diverse phagotrophic protists, mostly amoebae. A considerable portion of amoebozoans are lobose amoebae, meaning they produce round, blunt-ended pseudopods.[111] It includes the 'archetypal' amoebae, known as the naked lobose amoebae or 'gymnamoebae'[112] (such as Amoeba itself),[113] among which is a genus of sorocarp-forming slime moulds, Copromyxa.[114] Some gymnamoebae are important pathogens to animals (e.g., Acanthamoeba).[115] Other relevant lobose amoebae are the Arcellinida, a diverse order of testate amoebae and one of the most conspicuous protist groups overall.[116] The remaining, non-lobose amoebozoans include the Eumycetozoa or 'true slime moulds', comprising the sorocarp-producing bacterivorous dictyostelids and the sporocarp-producing omnivorous myxogastrids and protosporangiids.[2] Due to the fungus-like appearance of their fruiting bodies, eumycetozoans are often studied by mycologists.[17] Closely related to the eumycetozoans are two lineages: the Variosea, a heterogeneous assortment of amoeboid, reticulate or flagellated organisms[113] (including some sorocarp-producing organisms);[117] and the anaerobic Archamoebae, some of which live as intestinal symbionts of some animals (e.g., Entamoeba).[2]

Opisthokonta includes the animal and fungal kingdoms,[a] as well as their closest protist relatives. The branch leading to the fungi is known as Nucletmycea or Holomycota, while the branch leading to the animals is called Holozoa.[118] The Holomycota includes the closest relatives of fungi, the nucleariids, a small group (~50 species) of free-living naked or scale-bearing phagotrophic amoebae with filose pseudopodia, some of which can aggregate into slime moulds.[119] Within the wider definition of fungi, three groups are studied as protists by some authors: Aphelida (15 species),[12] Rozellida (27 species)[120] and Microsporidia (~1,300 species),[121] collectively known as Opisthosporidia, as opposed to the 'true' or osmotrophic fungi. Both aphelids and rozellids are single-celled phagotrophic flagellates that feed in an endobiotic manner, penetrating the cells of their respective hosts. Microsporidians are obligate intracellular parasites that feed through osmotrophy, much like true fungi. Aphelids and true fungi are closest relatives, and generally feed on cellulose-walled organisms (many algae and plants). Conversely, rozellids and microsporidians form a separate clade, and generally feed on chitin-walled organisms (fungi and animals).[122]

The Holozoa includes various lineages with complex life cycles involving different cell types and associated with the origin of animal multicellularity.[17] The closest relatives to animals are the choanoflagellates (~360 species), free-living flagellates that feed through a collar of microvilli surrounding a larger cilium and often form colonies.[123] The Ichthyosporea (>40 species), otherwise known as mesomycetozoans, are a group of fungus-like pathogenic holozoans specialized in infecting fish and other animals.[124] The Filasterea (six species) are a heterogeneous group of free-living, endosymbiotic, or parasitic amoebae or flagellates.[125] Lastly, the Pluriformea are two species of free-living holozoans with life cycles that include multicellular aggregates.[126] An elusive flagellate species Tunicaraptor unikontum has an uncertain evolutionary position among these holozoan groups.[127]

-

Amoeba, the archetypal amoebae

-

Physarum polycephalum, a true slime mould

-

Nuclearia, filose amoebae related to fungi

-

Creolimax fragrantissima, an ichthyosporean that infects peanut worms

-

A choanoflagellate colony, with cells resembling choanocytes found in sponges

Orphan groups

[edit]Several smaller lineages do not belong to any of the three main supergroups, and instead have a deep-branching "kingdom-level" position in eukaryote evolution. They are usually poorly known groups with limited data and few species, often referred to as "orphan groups".[40] The CRuMs clade, containing the free-swimming Collodictyonidae (seven species) with two to four cilia, the amoeboid Rigifilida (two species) with filose pseudopodia, and the gliding Mantamonadidae (three species)[128] and Glissandridae (two species)[129][130] with two cilia, are the sister clade of Amorphea.[38] The Ancyromonadida (35 species)[131] are aquatic gliding flagellates with two cilia, positioned near Amorphea and CRuMs.[38] The Hemimastigophora (ten species), or hemimastigotes, are predatory flagellates with a distinctive cell morphology and two rows of around a dozen flagella.[132] The Provora (eight species)[133] are predatory flagellates with an unremarkable morphology similar to that of excavates and other flagellates with two cilia. Both Hemimastigophora and Provora were thought to be related to or within Diaphoretickes,[3] although further analyses have placed them in a separate clade along with a mysterious species of predatory protists, Meteora sporadica. This species has a remarkable morphology: they lack flagella, are bilaterally symmetrical, project a pair of lateral "arms" that swing back and forth, and contain a system of motility unlike any other.[40]

There are also many genera of uncertain affiliation among eukaryotes because their DNA has not been sequenced, and consequently their phylogenetic affinities are unknown.[2] One enigmatic heliozoan species is so large that it does not match the description of any known genus, and was consequently transferred to a separate genus Berkeleyaesol with an unclear position, although it probably belongs to Diaphoretickes along with all other heliozoa.[134] The organism Parakaryon is harder to place, as it shares traits from both prokaryotes and eukaryotes.[135]

Biology

[edit]In general, protists have typical eukaryotic cells that follow the same principles of biology described for those cells within the "higher" eukaryotes (animals, fungi and land plants).[136] However, many have evolved a variety of unique physiological adaptations that do not appear in the remaining eukaryotes,[137] and in fact protists encompass almost all of the broad spectrum of biological characteristics expected in eukaryotes.[37]

Nutrition

[edit]Protists display a wide variety of food preferences and feeding mechanisms.[2][138] According to the source of their nutrients, they can be divided into autotrophs (producers, traditionally algae) and heterotrophs (consumers, traditionally protozoa). Autotrophic protists synthesize their own organic compounds from inorganic substrates through the process of photosynthesis, using light as the source of energy;[139]: 217 accordingly, they are also known as phototrophs.[140]

Heterotrophic protists obtain organic molecules synthesized by other organisms, and can be further divided according to the size of their nutrients. Those that feed on soluble molecules[139]: 218 or macromolecules under 0.5 μm in size are called osmotrophs,[138] and they absorb them by diffusion, ciliary pits, transport proteins of the cell membrane, and a type of endocytosis (i.e., invagination of the cell membrane into vacuoles, called endosomes) known as pinocytosis[2] or fluid-phase endocytosis.[138] Those that feed on organic particles over 0.5 μm in size or entire cells are called phagotrophs, and they ingest them through a type of endocytosis known as phagocytosis.[138][139]: 218 Endocytosis is considered one of the most important adaptations in the origin of eukaryotes because it increased the potential food supply, and phagocytosis allowed the endosymbiosis and development of mitochondria and chloroplasts. In both osmotrophs and phagotrophs, endocytosis is often restricted to a specific region of the cell membrane, known as the cytostome, which may be followed by a cytopharynx, a specialized tract supported by microtubules.[138]

Osmotrophy

[edit]Osmotrophic protists acquire soluble nutrients through membrane channels and carriers, but also through different types of pinocytosis. Macropinocytosis involves the folding of membrane into ruffles,[141] which creates large (0.2 to 1.0 μm) vacuoles. Micropinocytosis involves smaller vesicles that are usually formed by clathrin. In both scenarios, the vesicles merge into a digestive vacuole or endosome where digestion takes place.[138] Some osmotrophs, called saprotrophs or lysotrophs, perform external digestion by releasing enzymes into the environment and decomposing organic matter[2] into simpler molecules that can be absorbed. This external digestion has a distinct advantage: it allows greater control over the substances that are allowed to enter the cell, thus minimizing the intake of harmful substances or infection.[142]

Probably all eukaryotes are capable of osmotrophy, but some have no alternative of acquiring nutrients. Obligate osmotrophs and saprotrophs include some euglenids, some green algae, the human parasite Blastocystis, some metamonads,[2] the parasitic trypanosomatids,[143] and the fungus-like oomycetes and hyphochytrids.[142]

Phagotrophy

[edit]

Phagotrophic feeding consists of two phases: the concentration of food particles in the environment, and the phagocytosis, which encloses the food particle in a vacuole (the phagosome)[138] where digestion takes place. In ciliates and most phagotrophic flagellates, digestion occurs at the oral region or cytostome, which is covered by a single membrane from which vacuoles are formed; the phagosomes then may be shuttled to the interior of the cell along the cytopharynx.[145] In amoebae, phagocytosis takes place anywhere on the cell surface. The average food particle size is around one tenth the size of the protist cell.[146]

Phagotrophic protists can be further classified according to how they approach the nutrients. The filter feeders acquire small, suspended food particles or prokaryotic cells and accumulate them by filtration into the cytostome (e.g., choanoflagellates, some chrysomonads, most ciliates);[2] filter-feeding flagellates accumulate particles by propelling them with a flagellum through a collar of rigid tentacles or pseudopodia that act as a filter, while filter-feeding ciliates generate water currents through cilia and membranelle zones surrounding the cytostome. The raptorial feeders (e.g., bicosoecids, chrysomonads, kinetoplastids, some euglenids, many dinoflagellates and ciliates), instead of retaining all particles in bulk, capture each particle individually.[146] Among raptorial protists, the grazers search and ingest prey from surfaces covered with potential food items such as bacterial lawns, while the predators actively pursue scarce prey.[2] Predators that feed on filamentous algae or fungal hyphae either swallow the filaments entirely or penetrate the cell wall and ingest the cytoplasm (e.g., Viridiraptoridae).[2] Predators may have adaptations to hunt prey, such as 'toxicysts' that immobilize prey cells. Certain ciliates have developed a specialized kind of raptorial feeding called histophagy, where they attack damaged but live animals (e.g., annelids and small crustaceans), enter the wounds, and ingest animal tissue. Large raptorial amoebae enclose their prey in a "food cup" of pseudopodia, prior to the formation of the food vacuole.[146] Lastly, diffusion feeders (e.g., heliozoa, foraminifera and many other amoebae, suctorian ciliates) engulf prey that happen to collide with their pseudopods or, in the case of ciliates, tentacles that carry toxicysts or extrusomes to immobilize the prey.[146]

Consumers of prokaryotes are popularly called bacterivores (e.g., most amoebae), while consumers (including osmotrophic parasites) of eukaryotes are known as eukaryovores. In particular, eukaryovores that feed on unicellular protists are cytotrophs (e.g., colponemids, colpodellids, many amoebae, some ciliates); those that feed on fungi are mycophages or mycotrophs (e.g., the ciliate family Grossglockneriidae of obligate mycophages);[147] those that prey on nematodes are nematophages;[148] and those that feed on algae are phycotrophs (e.g., vampyrellids).[2]

Mixotrophy

[edit]Most autotrophic protists are mixotrophs[150] and combine photosynthesis with phagocytosis.[e] They are classified into various functional groups or 'mixotypes'.[152][153] Constitutive mixotrophs have the innate ability to photosynthesize through already present chloroplasts, and have diverse feeding behaviors, as some require phototrophy, others phagotrophy, and others are obligate mixotrophs (e.g., nanoflagellates such as some haptophytes and dinoflagellates). Non-constitutive mixotrophs acquire the ability to photosynthesize by stealing chloroplasts from their prey, a process known as kleptoplasty. Non-constitutives can be divided into two: generalists, which can steal chloroplasts from a variety of prey (e.g., oligotrich ciliates), or specialists, which can only acquire chloroplasts from a few specific prey (e.g., Rapaza viridis can only steal from Tetraselmis cells).[149] The specialists are further divided into two types: plastidic, which contain differentiated plastids (e.g., Mesodinium, Dinophysis), and endosymbiotic, which contain whole endosymbionts (e.g., mixotrophic Rhizaria such as Foraminifera and Radiolaria, dinoflagellates like Noctiluca).[152]

Among exclusively heterotrophic protists, variation of nutritional modes is also observed. The diplonemids, which inhabit deep waters where photosynthesis is absent, can flexibly switch between osmotrophy and bacterivory depending on the environmental conditions.[154]

Osmoregulation

[edit]

Many freshwater protists need to osmoregulate (i.e., remove excess water volume to adjust the ion concentrations) because non-saline water enters in excess by osmosis from the environment[155] and by endocytosis when feeding.[145] Osmoregulation is done through active ion transporters of the cell membrane and through contractile vacuoles, specialized organelles that periodically excrete fluid high in potassium and sodium through a cycle of diastole and systole. The cycle stops when the cells are placed in a medium with different salinity, until the cell adapts.[137]

The contractile vacuoles are surrounded by the spongiome, an array of cytoplasmic vesicles or tubes that slowly collect fluid from the cytoplasm into the vacuole. The vacuoles then contract and discharge the fluid outside of the cell through a pore. The contractile mechanism varies depending on the protist: in ciliates, the spongiome is composed of irregular tubules and actin filaments wind around the pore and over the vacuole surface, together with microtubules; in most flagellates and amoebae, the spongiome is composed of both vesicles and tubules; in dinoflagellates, a flagellar rootlet branches to form a contractile sheath around the vacuole (known as pusule).[145] The location and amount also varies: unicellular flagellated algae (cryptomonads, euglenids, prasinophytes, golden algae, haptophytes, etc.) typically have a single contractile vacuole in a fixed position; naked amoebae have numerous small vesicles that fuse into one vacuole and then split again after excretion. Marine or parasitic protists (e.g., metamonads), as well as those with rigid cell walls, lack these vacuoles.[155]

Respiration

[edit]The last eukaryotic common ancestor was aerobic, bearing mitochondria for oxidative metabolism. Many lineages of free-living and parasitic protists have independently evolved and adapted to inhabit anaerobic or microaerophilic habitats, by modifying the early mitochondria into hydrogenosomes, organelles that generate ATP anaerobically through fermentation of pyruvate. In a parallel manner, in the microaerophilic trypanosomatid protists, the fermentative glycosome evolved from the peroxisome.[137]

Sensory perception

[edit]

Many flagellates and probably all motile algae exhibit a positive phototaxis (i.e. they swim or glide toward a source of light). For this purpose, they exhibit three kinds of photoreceptors or "eyespots": (1) receptors with light antennae, found in many green algae, dinoflagellates and cryptophytes; (2) receptors with opaque screens; and (3) complex ocelloids with intracellular lenses, found in one group of predatory dinoflagellates, the Warnowiaceae. Additionally, some ciliates orient themselves in relation to the Earth's gravitational field while moving (geotaxis), and others swim in relation to the concentration of dissolved oxygen in the water.[137]

Endosymbionts

[edit]Protists have an accentuated tendency to include endosymbionts in their cells, and these have produced new physiological opportunities. Some associations are more permanent, such as Paramecium bursaria and its endosymbiont Chlorella; others more transient. Many protists contain captured chloroplasts, chloroplast-mitochondrial complexes, and even eyespots from algae. The xenosomes are bacterial endosymbionts found in ciliates, sometimes with a methanogenic role inside anaerobic ciliates.[137]

Life cycle and reproduction

[edit]

Protists exhibit a large range of life cycles and strategies involving multiple stages of different morphologies which have allowed them to thrive in most environments. Nevertheless, most of the knowledge concerning protist life cycles concerns model organisms and important parasites. Free-living uncultivated protists represent the majority, but knowledge on their life cycles remains fragmentary.[157]

Asexual reproduction

[edit]Protists typically reproduce asexually under favorable environmental conditions,[158] allowing for rapid exponential population growth with minimal genetic diversification. This asexual reproduction, occurs through mitosis and has historically been regarded as the primary reproductive mode in protists.[157] This process is also known as vegetative reproduction, as it is only performed by the 'vegetative stage' or individual.[159]

Unicellular protists often multiply via binary fission, similarly to bacteria.[157] They can also divide through budding, similarly to yeasts, or through multiple fissions, a process known as schizogony.[160] In multicellular protists, vegetative reproduction can take the form of fragmentation of body parts, or specialized propagules composed of numerous cells (e.g., in red algae).[159]

Sexual reproduction

[edit]While asexual reproduction remains the most common strategy among protists, sexual reproduction is also a fundamental characteristic of eukaryotes.[161][162] Sexual reproduction involves meiosis (a specialized nuclear division enabling genetic recombination) and syngamy (the fusion of nuclei from two parents).[157] These processes are thought to have been present in the last eukaryotic common ancestor,[163] which likely had the ability to reproduce sexually on a facultative (non-obligate) basis.[164] Even protists that no longer reproduce sexually still retain a core set of meiosis-related genes, reflecting their descent from sexual ancestors.[165][166] For example, although amoebae are traditionally considered asexual organisms, most asexual amoebae likely arose recently and independently from sexually reproducing amoeboid ancestors.[167] Even in the early 20th century, some researchers interpreted phenomena related to chromidia (chromatin granules free in the cytoplasm) in amoebae as sexual reproduction.[168]

Basic sexual cycles

[edit]Every sexual cycle involves the events of syngamy and meiosis, which increase or decrease the ploidy (i.e., number of chromosome sets, represented by the letter n), respectively. Syngamy implies the fusion of two haploid (1n) reproductive cells, known as gametes, which generates a diploid (2n) cell called zygote. The diploid cell then undergoes meiosis to generate haploid cells. Depending on which cells compose the individual or vegetative stage (i.e., the stage that grows by mitosis), there are three distinguishable sexual cycles observed in free-living protists:[157]

- In the haploid cycle, the individual is haploid and differentiates into haploid gametes through mitosis. The gametes fuse into a zygote which immediately undergoes meiosis to generate new haploid individuals.[157] This is the case for some green algae (namely Volvocales), many dinoflagellates, some metamonads, and apicomplexans.[145]: 26

- In the diploid cycle, the individual is diploid and undergoes meiosis to generate haploid gametes, which in turn fuse with others to form a zygote that develops into a new individual.[157] This is the case for some metamonads, heliozoans, many green algae, diatoms, and ciliates, as well as animals.[145]: 26 Instead of generating gametes, ciliates divide their diploid micronucleus into two haploid nuclei, exchange one of them by conjugation with another ciliate, and fuse the two nuclei into a new diploid nucleus.[67]

- In the haplo-diploid cycle, there are two alternating generations of individuals. One generation is the diploid 'agamont', which undergoes meiosis to generate haploid cells (spores) that develop into the other generation, the haploid 'gamont'. The gamont then generates gametes by mitosis, which in turn fuse to form the zygote that develops into the agamont.[157] This is the case for many foraminifera and many algae, as well as land plants.[145]: 26 There are three modes of this cycle depending on the relative growth and lifespan of one generation compared to the other: haploid-dominant, diploid-dominant, or equally dominant generations. Brown algae exhibit the full range of these modes.[169]

Free-living protists tend to reproduce sexually under stressful conditions, such as starvation or heat shock. Oxidative stress, which leads to DNA damage, also appears to be an important factor in the induction of sex in protists.[158]

Sexual cycles in pathogenic protists

[edit]Pathogenic protists tend to have extremely complex life cycles that involve multiple forms of the organism, some of which reproduce sexually and others asexually.[170] The stages that feed and multiply inside the host are generally known as trophozoites (from Greek trophos 'nutrition' and zoia 'animals'), but the names of each stage vary depending on the protist group.[160] For example:

- In apicomplexans, a haploid sporozoite is released into the host, penetrates a host cell, begins the infection and transforms into a meront that grows and asexually divides into numerous merozoites (a schizogony called merogony); each merozoite continues the infection by multiplying. Eventually, the merozoites differentiate (gamogony) into female (macrogametocytes) and male (microgametocytes) that generate gametes, which in turn fuse (sporogony) into a diploid zygote that grows into a sporocyst. The sporocyst then undergoes meiosis to form sporozoites that transmit the infection.[70][162]

- In phytomyxeans, the diploid primary zoospores enter the host, encyst, and penetrate cells as a uninucleate protoplast or plasmodium. Inside the cells, the protoplast grows into a multinucleate zoosporangium, which then divides into secondary zoospores that infect more cells. These multiply into thick-walled resting spores that begin meiosis and divide into binucleate resting spores; one nucleus is lost, and the spores hatch as primary zoospores.[171]

Some protist pathogens undergo asexual reproduction in a wide variety of organisms – which act as secondary or intermediate hosts – but can undergo sexual reproduction only in the primary or definitive host (e.g., Toxoplasma gondii in felids such as domestic cats).[172] Others, such as Leishmania, are capable of performing syngamy in the secondary vector.[173] In apicomplexans, sexual reproduction is obligatory for parasite transmission.[174]

Despite undergoing sexual reproduction, it is unclear how frequently there is genetic exchange between different strains of pathogenic protists, as most populations may be clonal lines that rarely exchange genes with other members of their species.[175]

Ecology

[edit]Protists are indispensable to modern ecosystems worldwide. They also have been the only eukaryotic component of all ecosystems for much of Earth's history, which allowed them to evolve a vast functional diversity that explains their critical ecological significance. They are essential as primary producers, as intermediates in multiple trophic levels, as key regulating parasites or parasitoids, and as partners in diverse symbioses.[37]

Habitat diversity

[edit]Protists are abundant and diverse in nearly all habitats. They contribute 4 gigatons (Gt) to Earth's biomass—double that of animals (2 Gt), but less than 1% of the total. Combined, protists, animals, archaea (7 Gt), and fungi (12 Gt) make up less than 10% of global biomass, with plants (450 Gt) and bacteria (70 Gt) dominating.[176] Protist diversity, as detected through environmental DNA surveys, is vast in every sampled environment, but it is mostly undescribed.[177] The richest protist communities appear in soils, followed by oceanic and lastly freshwater habitats, mostly as part of the plankton.[178] Freshwater protist communities are characterized by a higher "beta diversity" (i.e. highly heterogeneous between samples) than soil and marine plankton. The high diversity can be a result of the hydrological dynamic of recruiting organisms from different habitats through extreme floods.[179] Soil-dwelling protist communities are ecologically the richest, possibly be due to the complex and highly dynamic distribution of water in the sediment, which creates extremely heterogenous environmental conditions. The constantly changing environment promotes the activity of only one part of the community at a time, while the rest remains inactive; this phenomenon promotes high microbial diversity in prokaryotes as well as protists.[178]

Primary producers

[edit]Microscopic phototrophic protists (or microalgae) are the main contributors to the biomass and primary production in nearly all aquatic environments, where they are collectively known as phytoplankton (together with cyanobacteria). In marine phytoplankton, the smallest fractions, the picoplankton (<2 μm) and nanoplankton (2–20 μm), are dominated by several different algae (prymnesiophytes, pelagophytes, prasinophytes); fractions larger than 5 μm are instead dominated by diatoms and dinoflagellates.[177] In freshwater phytoplankton, golden algae, cryptophytes and dinoflagellates are the most abundant groups.[178] Altogether, they are responsible for almost half of the global primary production.[180] They are the main providers of much of the energy and organic matter used by bacteria, archaea, and higher trophic levels (zooplankton and fish), including essential nutrients such as fatty acids.[181] Their abundance in the oceans depends mostly on the availability of inorganic nutrients, rather than temperature or sunlight; they are most abundant in coastal waters that receive nutrient-rich run-off from land, and areas where nutrient-rich deep ocean water reaches the surface, namely the upwelling zones in the Arctic Ocean and along continental margins.[180] In freshwater habitats, most phototrophic protists are mixotrophic, meaning they also behave as consumers, while strict consumers (heterotrophs) are less abundant.[178]

Macroalgae (namely red algae, green algae and brown algae), unlike phytoplankton, generally require a fixation point, which limits their marine distribution to coastal waters, and particularly to rocky substrates. They support numerous herbivorous animals, especially benthic ones, as both food and refuge from predators. Some communities of seaweeds exist adrift on the ocean surface, serving as a refuge and means of dispersal for associated organisms.[182][183]

Phototrophic protists are as abundant in soils as their aquatic counterparts. Given the importance of aquatic algae, soil algae may provide a larger contribution to the global carbon cycle than previously thought, but the magnitude of their carbon fixation has yet to be quantified.[178] Most soil algae are stramenopiles (diatoms, xanthophytes and eustigmatophytes) and archaeplastids (green algae). There is also presence of environmental DNA from dinoflagellates and haptophytes in soil, but no living forms have been seen.[184]

Consumers

[edit]Phagotrophic protists are the most diverse functional group in all ecosystems, primarily represented by cercozoans (dominant in freshwater and soils), radiolarians (dominant in oceans), non-photosynthetic stramenopiles (with higher abundance in soils than in oceans), and ciliates.[178]

Contrary to the common division between phytoplankton and zooplankton, much of the marine plankton is composed of mixotrophic protists, which pose a largely underestimated importance and abundance (around 12% of all marine environmental DNA sequences). Mixotrophs have varied presence due to seasonal abundance[185] and depending on their specific type of mixotrophy. Constitutive mixotrophs are present in almost the entire range of oceanic conditions, from eutrophic shallow habitats to oligotrophic subtropical waters but mostly dominating the photic zone, and they account for most of the predation of bacteria. They are also responsible for harmful algal blooms. Plastidic and generalist non-constitutive mixotrophs have similar biogeographies and low abundance, mostly found in eutrophic coastal waters, with generalist ciliates dominating up to half of ciliate communities in the photic zone. Lastly, endosymbiotic mixotrophs are by far the most widespread and abundant non-constitutive type, representing over 90% of all mixotroph sequences (mostly radiolarians).[153][152]

In the trophic webs of soils, protists are the main consumers of both bacteria and fungi, the two main pathways of nutrient flow towards higher trophic levels.[186] Amoeboflagellates like the glissomonads and cercomonads are among the most abundant soil protists: they possess both flagella and pseudopodia, a morphological variability well suited for foraging between soil particles. Testate amoebae are also acclimated to the soil environment, as their shells protect against desiccation.[184] As bacterial grazers, they have a significant role in the foodweb: they excrete nitrogen in the form of NH3, making it available to plants and other microbes.[186] Traditionally, protists were considered primarily bacterivorous due to biases in cultivation techniques, but many (e.g., vampyrellids, cercomonads, gymnamoebae, testate amoebae, small flagellates) are omnivores that feed on a wide range of soil eukaryotes, including fungi and even some animals such as nematodes. Bacterivorous and mycophagous protists amount to similar biomasses.[147]

Decomposers

[edit]Necrophagy (the degradation of dead biomass) among microbes is mainly attributed to bacteria and fungi, but protists have a still poorly recognized role as decomposers with specialized lytic enzymes.[187] In soils, fungus-like protists and slime molds (e.g., oomycetes, myxomycetes, acrasids) are present abundantly as osmotrophs and saprotrophs.[184] In marine and estuarine environments, the well-studied thraustochytrids (part of labyrinthulomycetes) are relevant saprotrophs that decompose various substrates, including dead plant and animal tissue. Various ciliates and testate amoebae scavenge on dead animals. Some nucleariid amoebae specifically consume the contents of dead or damaged cells, but not healthy cells. However, all these examples are only facultative necrophages that also feed on live prey. In contrast, the algivorous cercozoan family Viridiraptoridae, present in shallow bog waters, are broad-range but sophisticated necrophages that feed on a variety of exclusively dead algae, potentially fulfilling an important role in cleaning up the environment and releasing nutrients for live microbes.[187]

Parasites and pathogens

[edit]Parasitic protists occupy around 15–20% of all environmental DNA in marine and soil systems, but only around 5% in freshwater systems, where chytrid fungi likely fill that ecological niche. In oceanic systems, parasitoids (i.e. those which kill their hosts, e.g. Syndiniales) are more abundant. In freshwater ecosystems, parasitoids are mainly Perkinsea and Syndiniales (Alveolata), while true parasites (i.e. those which do not kill their hosts) in freshwater are mostly oomycetes, Apicomplexa and Ichthyosporea.[178] In soil ecosystems, true parasites are primarily animal-hosted apicomplexans and plant-hosted oomycetes and plasmodiophorids.[184] In Neotropical forest soils, apicomplexans dominate eukaryotic diversity and have an important role as parasites of small invertebrates, while oomycetes are very scarce in contrast.[188]

Some protists are significant parasites of animals (e.g.; five species of the parasitic genus Plasmodium cause malaria in humans and many others cause similar diseases in other vertebrates), land plants[189][190] (the oomycete Phytophthora infestans causes late blight in potatoes)[191] or even of other protists.[192][193] Around 100 protist species can infect humans.[184]

Biogeochemical cycles

[edit]Marine protists have a fundamental impact on biogeochemical cycles, particularly the carbon cycle.[194] As phytoplankton, they fix as much carbon as all terrestrial plants combined.[178] Soil protists, particularly testate amoebae, contribute to the silica cycle as much as forest trees through the biomineralization of their shells.[184]

History of classification

[edit]Early classification

[edit]

From the start of the 18th century, the popular term "infusion animals" (later infusoria) was used for protists, bacteria and small invertebrates. In the mid-18th century, while Swedish biologist Carl Linnaeus largely ignored the protists,[f] his Danish contemporary Otto Friedrich Müller was the first to introduce protists to the binomial nomenclature system.[195][196]

In 1820, German naturalist Georg August Goldfuss coined the term "Protozoa" (meaning 'early animals') as a class within Kingdom Animalia[197] that consisted of four groups: Infusoria (ciliates), Lithozoa (corals), Phytozoa, and Medusinae (jellyfish). Later, in 1845, Carl Theodor von Siebold used the term "Protozoa" as a phylum of exclusively unicellular animals consisting of two classes: Infusoria (ciliates) and Rhizopoda (amoebae, foraminifera).[198] Other scientists did not consider all protozoans part of the animal kingdom, and by the middle of the century most biologists grouped microorganisms into Protozoa, Protophyta (primitive plants), Phytozoa (animal-like plants), and Bacteria (mostly considered plants). In 1860, palaeontolgist Richard Owen was the first to define Protozoa as its own kingdom of eukaryotes, although he also included sponges within his group.[28]

In 1860, British naturalist John Hogg proposed "Protoctista" as the name for a fourth kingdom, (the other kingdoms being plant, animal and mineral) which he described as containing "all the lower creatures, or the primary organic beings", which included Protophyta, Protozoa and sponges.[199][28]

In 1866, the 'father of protistology', German scientist Ernst Haeckel, addressed the problem of classifying all these organisms as a mixture of animal and vegetable characters, and proposed Protistenreich[200] (Kingdom Protista) as the third kingdom of life, comprising primitive forms that were "neither animals nor plants". He grouped both bacteria[201] and eukaryotes, both unicellular and multicellular organisms, as Protista. He retained the Infusoria in the animal kingdom, until German zoologist Otto Bütschli demonstrated that they were unicellular.[202][203] At first, he included sponges and fungi, but in later publications he explicitly restricted Protista to predominantly unicellular organisms or colonies incapable of forming tissues. He clearly separated Protista from true animals on the basis that the defining character of protists was the absence of sexual reproduction, while the defining character of animals was the blastula stage of animal development. He also returned the terms Protozoa and Protophyta as subkingdoms of Protista.[28]

End of the animal-plant dichotomy

[edit]Bütschli considered the kingdom to be too polyphyletic and rejected the inclusion of bacteria. He fragmented the kingdom into protozoa (only nucleated, unicellular animal-like organisms), while bacteria and the protophyta were a separate grouping. This strengthened the old dichotomy of protozoa/protophyta from German scientist Carl Theodor von Siebold, and the German naturalists asserted this view over the worldwide scientific community by the turn of the century. However, British biologist C. Clifford Dobell in 1911 brought attention to the fact that protists functioned very differently compared to the animal and vegetable cellular organization, and gave importance to Protista as a group with a different organization that he called "acellularity", shifting away from the dogma of German cell theory. He coined the term protistology and solidified it as a branch of study independent from zoology and botany.[28]

In 1938, American biologist Herbert Copeland resurrected Hogg's label, arguing that Haeckel's term Protista included anucleated microbes such as bacteria, which the term Protoctista (meaning "first established beings") did not. Under his four-kingdom classification (Monera, Protoctista, Plantae, Animalia), the protists and bacteria were finally split apart, recognizing the difference between anucleate (prokaryotic) and nucleate (eukaryotic) organisms. To firmly separate protists from plants, he followed Haeckel's blastular definition of true animals, and proposed defining true plants as those with chlorophyll a and b, carotene, xanthophyll and production of starch. He also was the first to recognize that the unicellular/multicellular dichotomy was invalid. Still, he kept fungi within Protoctista, together with red algae, brown algae and protozoans.[28][204] This classification was the basis for Whittaker's later definition of Fungi, Animalia, Plantae and Protista as the four kingdoms of life.[205]

In the popular five-kingdom scheme published by American plant ecologist Robert Whittaker in 1969, Protista was defined as eukaryotic "organisms which are unicellular or unicellular-colonial and which form no tissues". Just as the prokaryotic/eukaryotic division was becoming mainstream, Whittaker, after a decade from Copeland's system,[205] recognized the fundamental division of life between the prokaryotic Monera and the eukaryotic kingdoms: Animalia (ingestion), Plantae (photosynthesis), Fungi (absorption) and the remaining Protista.[206][207][28]

In the five-kingdom system of American evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis, the term "protist" was reserved for microscopic organisms, while the more inclusive kingdom Protoctista (or protoctists) included certain large multicellular eukaryotes, such as kelp, red algae, and slime molds.[208] Some use the term protist interchangeably with Margulis' protoctist, to encompass both single-celled and multicellular eukaryotes, including those that form specialized tissues but do not fit into any of the other traditional kingdoms.[209]

Advances in electron microscopy and molecular phylogenetics

[edit]

The five-kingdom model remained the accepted classification until the development of molecular phylogenetics in the late 20th century, when it became apparent that protists are a paraphyletic group from which animals, fungi and land plants evolved, and the three-domain system (Bacteria, Archaea, Eukarya) became prevalent.[210] Today, protists are not treated as a formal taxon, but the term is commonly used for convenience in two ways:[13]

- Phylogenetic definition: protists are a paraphyletic group.[211] A protist is any eukaryote that is not an animal, land plant or fungus,[212] thus excluding many unicellular groups like the fungal Microsporidia, Chytridiomycetes and yeasts, and the non-unicellular Myxozoan animals included in Protista in the past.[213]

- Functional definition: protists are essentially those eukaryotes that are never multicellular,[13] that either exist as independent cells, or if they occur in colonies, do not show differentiation into tissues.[214] While in popular usage, this definition excludes the variety of non-colonial multicellularity types that protists exhibit, such as aggregative (e.g., choanoflagellates) or complex multicellularity (e.g., brown algae).[215]

There is, however, one classification of protists based on traditional ranks that lasted until the 21st century. The British protozoologist Thomas Cavalier-Smith, since 1998, developed a six-kingdom model:[g] Bacteria, Animalia, Plantae, Fungi, Protozoa and Chromista.[10][216] In his context, paraphyletic groups take preference over clades:[10] both protist kingdoms Protozoa and Chromista contain paraphyletic phyla such as Apusozoa, Eolouka or Opisthosporidia. Additionally, red and green algae are considered true plants, while the fungal groups Microsporidia, Rozellida and Aphelida are considered protozoans under the phylum Opisthosporidia. This scheme endured until 2021, the year of his last publication.[9]

Fossil record

[edit]Before the existence of land plants, animals and fungi, all eukaryotes were protists. As a result, the early fossil record of protists is equivalent to the early record of eukaryotic life.[174] The protist fossil record is mainly represented by protists with fossilizable coverings, such as foraminifera, radiolaria, testate amoebae and diatoms, as well as multicellular algae.[217]

accepted fossil record (including name of earliest fossil), putative fossil record, biochemical signatures, molecular clock estimate, †major extinctions.

Paleo- and Mesoproterozoic

[edit]Modern or crown-group eukaryotes originated from the last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA) and emerged between 1600 and 2400 million years ago (Ma), during the Paleoproterozoic and Mesoproterozoic eras.[1] However, the fossil record through this time is scarce and dominated by stem-group eukaryotes, extinct lineages preceding LECA. These lineages displayed early eukaryotic traits like flexible cell membranes and complex cell wall ornamentations, which require a flexible endomembrane system, but they lacked crown-group eukaryotes' advanced sterols (e.g., cholesterol), and instead produced simpler protosterols that require less oxygen during biosynthesis.[218] Examples of these are: Trachyhystrichosphaera and Leiosphaeridia dated at 1100 Ma,[219] Satka dated at 1300 Ma,[220] Tappania and Shuiyousphaeridium dated at 1600 Ma,[221] Grypania dated at 1800–1900 Ma, and Valeria which ranges from 1650 to 700 Ma.[222]

Crown-group eukaryotes achieved significant morphological and ecological diversity before 1000 Ma, with multicellular algae capable of sexual reproduction and unicellular protists exhibiting modern phagocytosis and locomotion. Their advanced but metabolically expensive sterols likely provided numerous evolutionary advantages due to the increased membrane flexibility, including resilience to osmotic shock during desiccation and rehydration cycles, extreme temperatures, UV light exposure, and protection against changing oxygen levels. These adaptations allowed crown-group eukaryotes to colonize diverse and harsh environments (e.g., mudflats, rivers, agitated shorelines and land). In contrast, stem-group eukaryotes occupied the low-oxygen marine waters as anaerobes.[218] The oldest definitive crown-group eukaryotic fossils include Rafatazmia and Ramathallus, both putative red algae, dated at 1600 Ma.[1]

Neoproterozoic

[edit]As oxygen levels rose during the Tonian period, crown-group eukaryotes outcompeted stem-group eukaryotes, expanding into oxygen-rich marine environments that supported an aerobic metabolism enabled by their mitochondria. Stem-group eukaryotes may have gone extinct due to competition and the extreme climatic changes of the Cryogenian glaciations and subsequent global warming, cementing the dominance of crown-group eukaryotes.[218] Crown-group eukaryotes began to appear abundantly in this era, fueled by the proliferation of red algae. The oldest fossils firmly assigned to existing protist groups include three multicellular algae: the rhodophyte Bangiomorpha (1047 Ma),[223] the chlorophyte Proterocladus (1000 Ma),[218] and the xanthophyte Paleovaucheria (1000 Ma).[224][225] Also included are the oldest fossils of Opisthokonta: Ourasphaira giraldae (1010–890 Ma), interpreted as the earliest fungus,[218] and Bicellum brasieri (1000 Ma), the earliest holozoan, showing traits associated with complex multicellularity.[226]

Abundant fossils of heterotrophic protists appear significantly later, parallel to the emergence of fungi.[218] Vase-shaped microfossils (VSMs), widespread rocks dated at 780–720 Ma (Tonian to Cryogenian), have been described as a variety of organisms across the decades (e.g., algae, chitinozoans, tintinnids), but current scientific consensus relates most VSMs to marine testate amoebae.[227] As such, VSMs comprise the oldest known fossils of both filose (Cercozoa) and lobose (Amoebozoa) testate amoebae.[228][229]

After the Gaskiers glaciation of the Late Ediacaran (~579 Ma), fossils of heterotrophic protists undergo diversification. Some fossils similar to VSMs are interpreted as the oldest fossils of Foraminifera dated at 548 Ma (e.g., Protolagena),[227] but their foraminiferal affinity is doubtful. Other microfossils that are possibly foraminifera include some poorly preserved tubular shells from 716–635 Ma rocks.[230]

Paleozoic

[edit]Radiolarian shells appear abundantly in the fossil record since the Cambrian, with the first definitive radiolarian fossils found at the very start of this period (~540 Ma) together with the first small shelly fauna.[231] Radiolarian records from older Precambrian rocks have been disregarded due to the lack of reliable fossils.[232][233][234] Around this time, between 540 and 510 Ma, the oldest Foraminifera shells appear, first multi-chambered and later tubular.[235][217][230]

Following the Cambrian explosion and rapid diversification of animals, the Precambrian microbe-dominated ecosystems were replaced by primarily benthic and nekto-benthic communities, with most marine organisms (animals, foraminifers, radiolarians) limited to the depths of shallow water environments.[236] Mirroring the animal radiation, there was a radiation of phytoplanktonic protists (i.e., acritarchs)[237] around 520–510 Ma, followed by a decrease in diversity around 500 Ma.[238] Later, the surviving acritarchs expanded in diversity and morphological innovation[237] due to a decrease in predation from benthic animals (particularly trilobites and brachiopods), which suffered extinction due to various proposed environmental factors such as anoxia.[239] Both phytoplankton and zooplankton (e.g., radiolarians) flourished, as signaled by an increase of organic carbon buried in the sediment known as the SPICE event (~497 Ma).[236][239] This abundant biomass supported a second animal radiation known as the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event (GOBE), where many animals switched to a planktonic lifestyle and pelagic predators first appeared (e.g., cephalopods, swimming arthropods). This event is also known as the 'Ordovician Plankton Revolution' due to the significant diversification of planktonic protists, and it spanned from the late Cambrian well into the Ordovician.[236]

The Ordovician also includes the oldest euglenid fossil, known as Moyeria, which is found in rocks spanning from the middle Ordovician (~471 Ma) to the Silurian.[240] There are putative records of calcareous foraminifera from the Early Ordovician to the Silurian, but these are not widely accepted; the oldest trusted and well-known calcaerous foraminifera appear in the Middle Devonian, the next geological period.[217][241]