Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

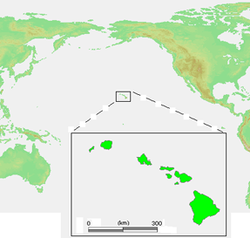

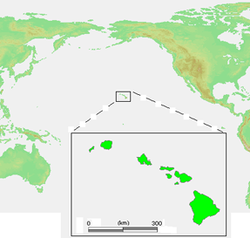

Naval Base Hawaii

View on Wikipedia21°21′23″N 157°57′53″W / 21.356365°N 157.964705°W

Key Information

Naval Base Hawaii was a number of United States Navy bases in the Territory of Hawaii during World War II. At the start of the war, much of the Hawaiian Islands was converted from tourism to a United States Armed Forces base. With the loss of US Naval Base Philippines in Philippines campaign of 1941 and 1942, Hawaii became the US Navy's main base for the early part of the island-hopping Pacific War against Empire of Japan. Naval Station Pearl Harbor was founded in 1899 with the annexation of Hawaii.[1][2]

History

[edit]Pearl Harbor started as a naval facility and coaling station after a December 9, 1887, agreement. King Kalākaua granted the United States exclusive rights to use Pearl Harbor as a port and repair base. The United States - Hawaii relationship started with the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875, a free trade agreement. On May 28, 1903, the first battleship, USS Wisconsin arrived at the new coal station for coal and water. The Naval Station had existed in Pearl Harbor since 1898, but in 1908 the United States Congress allocated $3 million to build Navy Yard Pearl Harbor. Also in 1908 the Great White Fleet stopped at Pearl Harbor on its journey around the globe.[3] During World War II Naval Base Hawaii was given the codename Copper and Naval Station Pearl Harbor the codename FRAY.[4] The fear of Japan's aggression started at the end of World War I.

After World War I in which Japan fought on the Allied side, Japan took control of German bases in China and the Pacific. In 1919, the League of Nations approved Japan's mandate over the German islands north of the equator. The United States did not want any mandates and was concerned with Japan's aggressiveness. As such Wilson Administration transferred 200 Atlantic warships to the Pacific Fleet in 1919.[5][6] The Port of San Diego was too shallow to handle the battleships, so San Pedro Submarine Base became a Naval Base on August 9, 1919. San Pedro Submarine Base and Long Beach became fleet anchorage for the 200 ships. In 1940, President Roosevelt had the fleet at San Pedro moved and stationed at Honolulu's Naval Base Pearl Harbor due to Japanese war actions in China. While the United States was committed to Neutrality in the 1930s, Japan's aggression against China had caused concern.

On December 7, 1941, Japan carried out a surprise military strike on the Naval Base in Pearl Harbor.[7][8] Japan hoped to eliminate US military force in the Pacific as it soon carried out attacks across the South Pacific. The attack led the US to enter World War II. For the US all of the Pacific Fleet aircraft carriers were at sea during the attack and most of the other ships sunk in the attack were repaired and put back in service. During the war, Hawaii became a major staging and training base for the Pacific War. Many wounded troops were sent to Hawaii hospitals.[9] The Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard became a major repair base for the war. Hawaii was a major supply depot and refueling depot for the Pacific War. A vast fleet of United States Merchant Navy ships help keep the base depots supplied. After the attack at Pearl Harbor, General Walter Short put Hawaii on Martial law, putting all of Hawaii under military rule till the end of the war. Japanese-Americans and Japanese immigrants on Hawaii were sent to Internment Camps during the war. Two small internment camps were built in Honolulu Harbor and Honouliuli. At Honouliuli 3,000 Japanese were held and later Italians, Okinawans, German Americans, Taiwanese, and a few Koreans were later held. At the end of the war, many of the troops returned home in Operation Magic Carpet and some of the small bases were closed. In the Korean War (1950–1953) some ships in the United States Navy reserve fleets returned to active duty after being overhauled at the shipyard and sea trialed by the base. With the Vietnam War (1955–1975) the base was again busy with support efforts. The Cold War (1947-1991) and the 600-ship Navy had Naval Base Hawaii active.[10][11] Hawaii was admitted as a US state on August 21, 1959 by the Hawaii Admission Act.[12]

Pearl Harbor attack

[edit]

Japan planned and carried out a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. Japanese midget submarines type Kō-hyōteki were used during the Pearl Harbor attack. Five midget submarines were launched before the Pearl Harbor attack: 16, 18, 19, 20, and 22. Of the five submarines it is thought that only two made it into the harbor. No. 19 was captured as it grounded on the east side of Oahu. No. 18 sank after a depth charge attack. No. 20 was sunk by Ward. No. 22 made it into Pearl Harbor and fired two torpedoes, both missed their targets before being sunk by the USS Monaghan. No.16 fired two torpedoes, at an unknown target. The midget submarines had been launched by fleet submarines I-16, I-18, I-20, I-22, and I-24 10 nmi (19 km; 12 mi) from Pearl Harbor.[13][14]

Imperial Japanese aircraft (including fighters, level and dive bombers, and torpedo bombers) attacked bases in Hawaii, including Pearl Harbor in two waves. The aircraft were launched from six aircraft carriers 430 km (260 mi) north of Hawaii. The main target was Battleship Row at Ford Island and the airfields. Seven battleships were at Ford Island and one was in dry dock No. 1 for repairs, the USS Pennsylvania. All eight battleships were damaged and four were sunk in the shallow waters of Pearl Harbor. The battleship USS Arizona and USS Utah were not salvaged and remain as war grave memorials. The battleship Oklahoma was salvaged and then scrapped due to her age. The other battleships damaged were repaired and returned to service: West Virginia, California, Nevada, Maryland, Tennessee and Pennsylvania. In the attack three cruisers: Helena, Raleigh and Honolulu were damaged and later repaired. Four destroyers: Cassin, Downes, Helm, Shaw were damaged and later repaired.[15] and one minelayer. More than 180 US aircraft were destroyed.[16] In the attack 2,403 Americans were killed and 1,178 others were wounded.[17] The attack destroyed most of the planes at NAS Ford Island, Hickam Field, to the North Wheeler Airfield and NAS Kaneohe Bay. Japan's focus on the battleships, other large ships and airfields in the attack left other parts of the base unharmed: the power station, dry docks, shipyard, depots, fuel tanks, and torpedo depot, ammo, depots, submarine base, intelligence office. Of the Japanese 354 planes 29 aircraft were lost.[18][19][20]

At the time of the attack, no US aircraft carriers were at Pearl Harbor. The USS Enterprise was returning to Pearl Harbor and was 215 miles west of Pearl Harbor. USS Lexington was 500 miles southeast of Midway. USS Saratoga was at NAS San Diego preparing to depart to Pearl Harbor. Due to the attack, the USS Yorktown was transferred to the Pacific Fleet on 16 December 1941. New aircraft carriers would join the Pacific War and other transferred. The USS Yorktown was later sunk by Japanese submarine I-168 on 7 June 1942. USS Lexington (CV-2) was badly damaged in the Battle of the Coral on 8 May 1942 and was scuttled.[21]

Current Hawaii Naval Bases

[edit]- Joint Base Pearl Harbor–Hickam - Navy Region Hawaii since 25 July 1997

- Lualualei VLF transmitter

- Pearl Fleet Navy Exchange Store[22]

- Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard

- Mana Airport, became Pacific Missile Range Facility in 1957, Barking Sands, Kauai FPO# 901

- Naval Computer and Telecommunications Area Master Station Pacific in Wahiawa, was Naval Radio Station Wahiawa

- Navy Information Operations Command, Hawaii (NIOC Hawaii)

- The US Navy supports: Marine Corps Air Station Kaneohe Bay

Naval Submarine Base Pearl Harbor

[edit]

Naval Submarine Base Pearl Harbor opened in 1918 at the end of World War I. The US Navy sent United States R-class submarines: USS R-15 (SS-92) and USS R-20 (SS-97). The submarines arrived in January 1919. In 1912 four F-class submarines operated out of the Naval Station at Pier 5 in Honolulu. USS F-4 sank off Honolulu in 1915 and the remaining F-class submarines were taken back to the states.[23] In 1916 four K type submarines operated out of Pearl Harbor with the submarine tender USS Alert (AS-4) till after World War I.[24] In 1919 a submarine base was built with waterfront concrete docking slabs at 21°21′18″N 157°56′31″W / 21.355°N 157.942°W, on Quarry Loch and Magazine Loch. Commander Chester W. Nimitz, later Fleet Admiral Nimitz, was the first Commanding Officer of the Pearl Harbor Submarine Base, Submarine Division 14. Some of the new bases building were aviation cantonment buildings from World War I France. The new base had a mess hall, administration building; machine shop, carpenter shop, electric plant, gyro-compass shop, optical and battery overhaul shops. For general stores, a floating barge was used. Starting in 1920, nine United States R-class submarine were stationed Pearl Harbor in 1920. In 1923 permanent building construction was stated. With limited barracks during construction submarine personnel lived on the 1885 cruiser USS Chicago, later renamed the USS Alton, at where pier S1 is now.[25] By 1925, the sub base had about 25 buildings and some swamp land had been turned in usable land. In 1928, the current U-shaped barracks building was built to house all submarine and submarine base personnel. By 1933, submarine berths 10 to 14 were completed with a 30-ton crane for servicing the subs. In 1933 a submarine rescue and training tank was built. In 1933 a new torpedo shop, pool, theater and repair building were completed and the USS Alton retired. Pearl Harbor Submarine Base was not attacked on 7 December 1941, the base was small compared to Naval Base and battleships. So the submarine fleet was the first to take the war to Japan in the Pacific.[26][27] The submarine Base started with 359 men on 30 June 1940, then 700 on 15 August 1941, to 1,081 by July 1942, and peaked July 1944 with 6,633 men at the Submarine Base.[28] Over 400 men were stationed on submarines out of the 123.5 acre base. During the war, the base handled 15,644 torpedoes and 5,185 torpedoes fired at enemy vessels. Of these 1,860 torpedoes made successful hits. Submarine Base had is own Base Medical Department, as medical needs on a sub are different than a ship. For Rest and Recuperation, the Submarine Base used the nearby Royal Hawaiian Hotel with 425 rooms, air crew and small craft crew used the hotel also. The base had a baseball team: the Pearl Harbor Submarine Base Dolphins. The bases on Hawaii each had a team that would play in their downtime. Submarine Memorial Chapel it is the oldest chapel at Pearl Harbor, it in now a remembrance of all the submariners who died in World War II.[29][30] On 7 December 1941, the US Navy had operational: 55 fleet submarine and 18 medium-sized submarines (S-class submarines) in the Pacific, 38 submarines in other theaters, and 73 submarines under construction.[31] By the end of World War II, the Navy had built 228 submarines.[32] Commander, Submarine Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet, USS Parche Memorial, Submarine Memorial Park, Sharkey Theater, Paquet Hall, NGIS Lockwood Hall Annex, and Navy Gateway Lockwood Hall are on the former Naval Submarine Base Pearl Harbor location on Quarry Loch and Magazine Loch in Southeast Loch.

Pearl Harbor PT Boat Base

[edit]

At the Naval Submarine Base Pearl Harbor was the Pearl Harbor PT Boat Base. PT boats used the same torpedoes as the submarines so the PT Boat base operated out of the Submarine Base. At the time of the attack six PT boats were in Magazine Loch at the base at Berth S-13: PT-20, PT-21, PT-22, PT-23, PT-24, and PT-25, Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron One. The PT Boats were the first to use their anti-aircraft guns to shoot back. The PT Boats fired over 4,000 rounds at the planes with Boat PT-23 shooting down the first Japanese torpedo bomber in the attack. The boats engaged in anti-submarine patrols after the attack. YR-20, a submarine barge, was being used as a PT Boat tender for the PT Boat squadron at Pearl Harbor. Six PT Boats, at the time of the attack, were in various stages of being loaded onto the deck of the oil tanker, USS Ramapo, to be shipped to Naval Base Philippines. Ramapo was at berth B-12 at the Naval Yard, as a Naval Yard crane was being used to load the boats. Patrol torpedo boat PT-29 was one the boats already loaded on Ramapo. The six PT-Boats at replenishment oiler Ramapo, PT-26, PT-27, PT-28, PT-29, PT-30 and PT-42, were able to fire at the attackers. With the fall of the Philippines the 12 PT Boats were sent to defend the Midway Atoll in May 1942 under their own power. PT-23 broke down en route and was returned to Pearl Harbor.[33][34] In 1943 PT Boats with Squadron 26, (PT-255 thru PT-264) were stationed at Pearl Harbor. PT Boats had a range of about 500 miles and were armed with four .50-caliber machine guns and four 21-inch torpedo tubes. PT Boat were wooden boat that were small, fast and able to attack large ships.[35][36]

Ford Island Seaplane Base

[edit]

Ford Island Seaplane Base was located on Ford Island's southwestern corner in Pearl Harbor. The base was called Naval Air Station Ford Island, (NAS Ford Island). On December 16, 1918, two seaplane ramps and two seaplane hangars were built. The base was near the Joint Services Flying Field, later renamed Luke Field Amphibian Base. The Island in the early days was called Rabbit Island. The US Army operated Luke Field, a 5,400 foot long runway, on Ford Island from 1919 to 1941.[37] In 1941 all of Ford Island used by the US Navy and renamed NAS Pearl Harbor. US Navy unit VJ-1 (JRS-1) was based at the Seaplane Base. Ford Island Seaplane Base was the first base hit on the 7 December 1941 attack. An Aichi D3A Val piloted by Lt Cdr Takahashi dropped the first bomb, a 242 kg Type 98 land bomb at 7:55am on the seaplane ramp. During the war Consolidated PBY Catalina and Martin PBM Mariner were both stationed and passed through the base. Battleship Row was along the east shore of Ford Island.[38][39][40] K. Mark Takai Pacific Warfighting Center is currently on Ford Island.

Net laying

[edit]

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, there was concern about a second attack, as such more anti-submarine net operations were put in place to protect capital ships and the dry docks. Net laying ships: USS Ash, and USS Cinchona Aloe-class net laying ships, worked at Pearl Harbor through the war. YNG-17 a net barge was used by the net laying ships to store nets at Pearl Harbor. In 1941 at the Pearl Harbor entrance the Navy had only a torpedo net installed. The torpedo net was only about 30 feet deep and did not extend down to the bottom of the channel with anchors. Submarine nets are anchored to the bottom. One and maybe two midget submarines were able to go under the torpedo net. At the time of the attack, no nets were installed in the Naval Base harbor, as the shallow harbor was thought to be safe from air torpedoes. After the attack temporary and later permanent nets were placed to protect capital ships and the dry docks. a fleet of net laying ship ships were built and used at major bases across the Pacific War.[41][42][43]

Kaneohe Bay Seaplane Base

[edit]

Kaneohe Bay Seaplane Base, Naval Air Station Kaneohe Bay, at Kaneohe Bay, Oʻahu on 464 acres of the Mokapu Peninsula.[44] In 1940 a 5,700 by 1,000 foot runway was added to seaplane base, with housing for 9,000 men. During the 1941 attack, only 9 of the 36 PBY Catalinas at Kaneohe Base survived the attack and of the 9 that survived, six were damaged. At the Kaneohe Bay Seaplane Base 18 sailors were killed in the attack. Seabees built an assembly depot, repair depot, plating shop, engine testing depot, and an engine-overhaul depot. In February 1944 the Seabees built a second runway 5,000-feet long, Kaneohe Field.[45][46] US Navy units stationed during the war at Kaneohe were: Patrol Wing 1, VP-14 with PBY, 318th Fighter Group, 73rd Fight group with Curtiss P-40E Warhawk) and VP-137 with Lockheed Ventura PV-1). Kaneohe Field had an assembly and repair shop for aircraft. Naval Air Station Kaneohe was a training center for aviation, naval gunnery, turret operations, celestial navigation, sonar, and other naval operations till 1949. For baseball the base had the: Naval Air Station (NAS) Kaneohe Bay Klippers. Kaneohe Field is now part of Marine Corps Base Hawaii - Marine Corps Air Station Kaneohe Bay. In 1951, the Marine Corps took over Kaneohe Field, and the Navy moved land operations to NAS Barbers Point.[47][48]

Naval Air Station Honolulu

[edit]

Naval Air Station Honolulu also called Honolulu Airfield, was John Rodgers Field at Keehi Lagoon on the south shore of Oahu.[49] The Navy acquired the commercial airfield John Rodgers Airport, in February 1943. John Rodgers Airport opened in March 1927. Next to the John Rodgers runway, the Navy built a second runway and a seaplane base. The Seabee lengthened the John Rodgers, the two runways were 7,400 feet and 6,800-foot long. The Seabee built two new 6,600-foot parallel runways on fill, aviation-gasoline storage, control tower, barracks, depot, 10 plane nose hangar, and two seaplane ramps. The main Naval activity at the base was the Naval Air Transport Service. The US Navy WAVES were stationed at Naval Air Station Honolulu with their own quarters. Naval Air Station Honolulu support the largest seaplane, Martin JRM Mars.[50] The US Navy used Martin JRM Mars for cargo from San Francisco Bay starting 23 January 1944.[51][52] The Martin JRM Mars service continued until 1956. In 1946 Airfield was returned to commercial use. The runways are now Honolulu International Airport.[53][54]

Pearl City Seaplane Base

[edit]During the war, in 1942, the Navy took over most of the Pan American Airways terminal, the Pan American Clipper Hawaii Terminal, on the southern tip of the Pearl City Peninsula at 21°22′31″N 157°58′37″W / 21.375375°N 157.976901°W. The Naval Air Transport Service operated out of the base, new Pearl City Seaplane Base. Once Naval Air Station Honolulu opened Naval Air Transport Service moved to Honolulu Seaplane base. Pan American Airways started using the Pearl City terminal in 1934, including the China Clipper and Honolulu Clipper. The terminal was returned to Pan American after the war, but with many land base runways built during the war, the terminal was closed in a few years.[55]

Aiea Naval Hospital

[edit]

Aiea Naval Hospital construction started in July 1939. There was an expectation of war and the Navy wanted to be sure to care for the troops. The Aiea Naval Hospital was on 41 acres of land atop a steep hill north of Pearl Harbor. The Aiea Naval Hospital opened with 1,100-beds in early 1941. After the December 1941 attack, construction accelerated. After the attack, 960 patients were admitted and 452 died over the three hours after the attack. The Hospital Ship USS Solace, not damaged in the attack took in 177 patients. Aiea Naval Hospital was the primary rear-area hospital for Navy and Marines. As the Pacific War grew, so did the hospital. In 1944 temporary wards with 5,000 beds was added by the US Navy's Seabees, Naval Construction Battalion. Aiea Naval Hospital had patients from battles in Solomon, Gilbert, Marshall Islands, Saipan, Guam, and Mariana Islands. In 1944 the hospital received 41,872 patients, and 39,006 of these patients were transferred to the mainland or returned to active duty. The hospital's patients peaked in March 1945 with 5,676 patients after the battles of Okinawa and Iwo Jima. Hospital patients were entertained by 1940s celebrities like: Boston Red Sox Joe Cronin, organist Gaylord Carter, Nearby recreation center had: bowling alleys, tennis, and volleyball courts, and billiard tables for able patients.

The 25-acre site's Richardson Recreation Center was used by all troops. The Hospital patient's food gardens, cared for by patients, as part of rehabilitation. The staff had a baseball team the: Aiea Naval Hospital Hilltoppers, as the hospital was on volcanic ridge overlooking Pearl Harbor. The teams played in the Central Pacific Area (CPA) League. Next to the hospital was the Aiea Naval Barracks, with the Aiea Naval Barracks Maroons team. Aiea Naval Hospital closed in June 1949 and is now part of Camp H. M. Smith. The 1949 patients were moved to a joint Army and Navy medical center at Tripler Army Medical Center.[56]

- On McGrew Point in Pearl Harbor at Aiea Heights was Naval Base Hospital No. 8, a temporary hospital to augment Pearl Harbor hospital facilities. The hospital was built with quonset hut and closed in 1945. Mobile Hospital No. 2 operated at McGrew Point before No. 8 from 1941 to 1943. Mobile Hospital No. 2 received 110 patients from the 1941 attack.[57] Naval Regional Medical Clinic (NRMC), Pearl Harbor was opened on March 8, 1974.[58]

- The Naval also built a temporary Naval hospital near the Tripler Army Medical Center called the Moanalua Ridge Naval Hospital, with 3,000 beds.[59]

Hospital Point

[edit]Naval Hospital Pearl Harbor at Hospital Point was the first naval hospital at Pearl Harbor opened in May 1915 with a 50-bed at 21°20′53″N 157°58′01″W / 21.348°N 157.967°W. From 1892 to 1910 the USS Iroquois was used as the Marine Hospital Service Hospital Ship for the base. In 1901 a dispensary building was built at the old Honolulu Naval Station. Surgeon General Rixey put in a request for new Hospital in 1909, which lead to the construction of the 1915 hospital at Hospital Point. Starting in 1925 and completed in 1930 more wards and buildings were added to keep up with the growth of the base. On Ford Island a Naval Dispensary was built in 1940. With Aiea Naval Hospital completed the plan was to close the Hospital Point Hospital, but with World War II the need was great and the old Hospital continued operations, called Naval Hospital Navy No. 10, till the end of the war. Hospital Point is now a Naval House complex.[60]

Navy Yard Pearl Harbor

[edit]

Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard was built in 1908. The first drydock was completed in 1919.[61] Ship repairs start with the founding of the base in 1898. Three more drydocks were completed in 1941, 1942 and 1943. Dry Dock No. 4 built in 1943 was built at Hospital Point. To help with the World War II workload, the Auxiliary floating drydock USS YFD-2 was added in October 1940 until 1947. The main shipyard was not attacked in 1941, only the ships at the yard were targeted. After the 1941 attack, only Dock No. 2 was working. YFD-2 and Dock No. 1 were repaired and used to repair the many ships damaged in the 1941 attack. The four drydocks and YFD-2 could not keep up with the demand of the war, a new Auxiliary floating drydock, USS ARD-1 was stationed at the yard during the war able to repair destroy-size ships. USS ARD-8 was stationed at Pearl Harbor and Midway. USS Richland (YFD-64) started work at Pearl Harbor and then was sent to Naval Base Eniwetok, Naval Base Ulithi and then Leyte-Samar Naval Base.[62][63][64] At the end of the war the USS Arco (ARD-29) transferred from Naval Base Okinawa to Pearl Harbor in 1946.

After the war the shipyard was renamed, Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard. After Naval Submarine Base Pearl Harbor closed, submarine service was moved to Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard.[65]US Nuclear Submarines are still supported at the shipyard.[66][3]

Naval Air Station Kahului

[edit]

Naval Air Station Kahului was a US Naval Air Station on the north shore of Maui, Hawaii. Naval Air Station Kahului was used for carrier aircraft aviation training. The airfield opened 15 March 1943, construction started 16 November 1942. The land had been leased from a sugar company, Hawaiian Commercial and Sugar Company. Five miles south of Naval Air Station Kahului was NAS Puunene, which was too small to keep up with the carrier aircraft demands of World War II. Holmes and Narver, Industrial and Architectural Engineers in Los Angeles won the contract to build the first part of the Air Station. Naval Air Station Kahului had two runways, 5,000 feet and 7,000 feet long. Navy Squadron VC-23 with Douglas SBD Dauntless scout bombers were the first unit based at Naval Air Station Kahului. Some troops trained at Naval Air Station Kahului joined Carrier Aircraft Service Units (CASUs). Carrier Air Service Unit 32 was the first unit at the base, on 1 September 1943. In April 1943 Seabee expanded the Air Station, 142nd Construction and 39th Construction worked on the base. On 11 February 1944 Construction Maintenance Unit 563 arrived to run the Air Station. The airfield was support by a small Naval Base at Kahului Harbor. Naval Air Station Kahului was deactivated in December 1947. The Navy turned the airfield over to civil aviation, Hawaii Aeronautics Commission and the base became the Kahului Airport. Commercial airline operations started in June 1952.[67][68]

Naval Air Station Puunene

[edit]

Naval Air Station Puunene started as a civil airport at Puʻunene in 1939, the Navy took over the airport on December 7, 1941, after the attack. At the time the construction work at the airport was about 90 percent completed at 20°49′01″N 156°27′36″W / 20.817°N 156.46°W. The 2,202 acres airfield had two 4,500-foot runway. The Naval Air Station Puunene facilities were expanded to support the carrier plane training base. The southwest runway was extended to 6,000 feet. The northwest–southeast runway was extended s7,000 feet. The base was renamed Naval Air Station Maui in 1942. US Navy CASU 4 and VF-72 were the first to operate out of the NAS Maui. Naval Air Station Puunene also used the Maalaea Outlying Landing Field for training and Kahoolawe island for a bombing range.[69] Later part of the carrier plane training base moved to the newer Naval Air Station Kahului five miles away, in 1943, as NAS Puunene could not keep up with the war demand for carrier aircraft aviation training. Interisland Airlines was operated out of the base with limited civil air travel. Naval Air Station Puunene became a commercial airport on October 1, 1946. The Navy ended ownership in December 1948, the base-airport facilities was larger than needed for a civil airport and some of the surplus land and surplus buildings were sold. The 515.639 acres base was now in the ownership of the Territory of Hawaii, the Army, the Navy and the Hawaiian Commercial and Hawaiian Sugar Company. Hawaiian Airlines (now American) was the only operator out of the airport. All airport operations moved to Kahului Airport (former Naval Air Station Kahului) and Puunene Airport on June 24, 1952. The title of Maui airport also moved from Puunene Airport to Kahului Airport. Puunene Airport closed on December 31, 1955. Puunene Airport was used for drag racing in 1956. Starting in September 1958 the Puunene Airport land was sold off, with the profits going to improve the Kahului Airport. One runways is still used by the Maui Raceway Park. Nearby on the former base are the Maui Go Karters Association, Signature Maui Event Rentals, Maui Motocross Track and the Army National Guard Armory off the Maui Veterans Hwy.[70][71][72]

Carrier Aircraft Service Units

[edit]

In 1942, Ewa Field, Naval Air Station Kahulu and NAS Puunene became a major United States Marine Corps and US Navy aviation training facilities for Carrier Aircraft Service Unit (CASU). Flight crews and air mechanics trained at Ewa Field for the upcoming Pacific War, including Battles at Wake Island, Guadalcanal, and Midway. Also at Ewa Field the Navy had a lighter-than-air base for blimps and WAVES base. Ewa airfield had four runways from 2,900 feet to 5,000 feet.[73][74]

- Carrier aircraft used during World War II by US Navy: (years used) (number built)

- Douglas TBD Devastator - torpedo bomber (1937-1944) (130)

- Grumman F4F Wildcat - torpedo bomber (1941-1945) (7,885)

- Grumman TBF Avenger - torpedo bomber (1941-1948) (9,839)

- Grumman F6F Hellcat - fighter-bomber (1942-1947) (12,275)

- Curtiss SB2C Helldiver - dive bomber (1943-1953) (7,140)

- Vought F4U Corsair - fighter-bomber (1943-1953) (12,571)

- A few North American T-6 Texan - Land Trainer aircraft were stationed in Hawaii (1935-1958) (15,495)

Aircraft carriers of World War II would have 70 to 100 planes on board. Escort carriers would carry 20 to 30 planes. US Navy and US Marines also operate the planes from land bases.

Tenders

[edit]During World War II the demand for servicing ships and submarines was so great that the land base operations could not supply all the needs. As in many of the US Naval Advance Bases across the Pacific War, tender ships were used to support Navy vessels. Tenders provided: food, water, fuel, ammo, repairs, and for submarines and seaplanes crew living quarter.

The submarine tenders: USS Argonne (AS-10), USS Widgeon (ASR-1) and USS Pelias were at Pearl Harbor during the Japanese attack. The USS Fulton (AS-11), a submarine tender was used to support submarines at Pearl Harbor from 15 March 1942 to 8 July 1942.[75] YR-20, was submarine barge used as a submarine and PT Boat tender. USS Orion (AS-18) was station from November 1943 to 10 December 1943, the USS Gar (SS-206) is one of the Submarines she repaired at Pearl Harbor.[76] USS Sperry (AS-12) worked at Pearl Harbor in 1942.[77] USS Bushnell (AS-15) and USS Griffin (AS-13) worked at Pearl Harbor in 1943 and 1944.[78]

The destroyer tender USS Whitney (AD-4) and USS Dobbin (AD-3) were at Pearl Harbor during the Japanese attack.[79] USS Dixie (AD-14) worked at Pearl Harbor in 1942.[80] USS Piedmont (AD-17) worked at Pearl Harbor 1944.[81]

The seaplane tenders, USS Avocet (AVP-4), USS Swan (AVP-7), USS Hulbert (AVD-6), USS Thornton (AVD-11) USS Curtiss (AV-4), and USS Tangier (AV-8) were at Pearl Harbor during the Japanese attack.[82]

US Navy repair ships would come alongside a vessel, like a tender, to provide repair (or salvage) operations. The repair ship had machine shops, parts depot, the tools and crews to get ships repaired or able to get to drydocks. The USS Vestal was next to the USS Arizona during the attack.[83][84] Other repair ships during the attack: USS Medusa (AR-1) and USS Rigel (AR-11)

Waipio Peninsula Amphibious Base

[edit]On the Waipio Peninsula the Navy operated a US Amphibious Training Base, Waipio Peninsula Amphibious Base. The base was at 21°21′40″N 157°59′13″W / 21.361°N 157.987°W and trained troops for the Pacific island-hopping campaigns.[85] Waipio Peninsula Naval Reservation Airfield was built at the base after the war, with a single northeast–southwest runway along the eastern shore of the Walker Bay of the base. The airfield and run runway were abandoned, little remain of the base, as it is now overgrown with vegetation.[86][87][88]

Underwater Demolition Teams

[edit]

The US Navy's Underwater Demolition Teams are the forerunner to today's United States Navy SEALs, they were founded in December 1943 in Hawaii. The first of 30 WW2 teams, was Underwater Demolition Team One, UDT-1 established with UDT-2 in December 1943. The Underwater Demolition Team trained at Amphibious Training Base Kamaole an (ATB) on Maui and Amphibious Training Base Waimanalo (ATB) at Waimanalo on Oahu near current Bellows Air Force Station. The Amphibious Training Base Kamaole used the 8 miles of beach from Māʻalaea Bay to Makena Landing at 20°43′14″N 156°26′57″E / 20.720466°N 156.449091°E from 1943 to 1944. Amphibious Training Base Waimanalo at Waimanalo Beach, 21°22′05″N 157°42′33″W / 21.36805°N 157.7091°W, was used from 1943 to 1944. At Bellows Air Force Station is memorial to the men of the Underwater Demolition Team, that reads: This WWII combat swimmer commemorates the birthplace of the U.S. Navy SEAL Teams. Commissioned here in December 1943, UDT-1 and UDT-2 paved the way for 28 more Maui-based UDTs, which played a major role in the island battles of the Pacific between 1944 and 1945. These "Naked Warriors" swam unarmed onto heavily-defended enemy beaches with explosives to clear the way for amphibious landings. The concrete "scully" on which this swimmer stands is typical of the underwater obstacles they risked their lives to destroy. [89]

Station HYPO

[edit]Fleet Radio Unit Pacific, also called Station HYPO, was the US Navy's codebreaking unit in Hawaii. The Navy unit was used in breaking Japanese naval codes.[90] The US Navy's Station CAST and Fleet Radio Unit at Naval Base Melbourne was the other unit working on codebreaking. The unit at Naval Base Cavite and Naval Base Manila's Corregidor Island was lost with the fall of the Philippines in 1942. Station HYPO was key in finding the planned attack on Midway in 1942.[91][92]

Supply depots

[edit]

- On Kuahua Island, now Kuahua peninsula, due to land fill, the Navy built a large supply depot on 47-acres at 21°21′25″N 157°56′46″W / 21.357°N 157.946°W called Supply Base Magazine Island. Fill material was used to extend the island to 116 acres and turn the island into a peninsula (current site of NAVSUP Fleet Logistics Center Pearl Harbor). Piers and railway tracks were built to move the vast amount of supplies needed to support the Troops in the Pacific war. Still a depot for the base, NAVSUP Fleet Logistics Center Pearl Harbor.[93]

- A second supply depot was built at Merry Point Landing on Quarry Loch, at 21°21′07″N 157°56′35″W / 21.352°N 157.943°W just south of the Sub Base. Merry Point depot was built by the 64th and the 90th Seabees. Also at Merry Point was the fuel depot ship landing for fleet oil tankers. Still a depot for the base.

- A third depot was built at Pearl City (Pearl City peninsula) called the Manana Supply Center at 21°22′N 157°58′W / 21.37°N 157.96°W. Pearl City was the site for Naval Base Hawaii part distribution and the Naval Air Transport station. Depot closed after war.

- At Salt Lake, a neighborhood of Honolulu, was a storage area and the Seabees Advance Base Construction Depot (ABCD), stored supplies used to build new advance bases across the Pacific. Advance Base Construction Depot was built by the 117th Battalion Seabees, with 26,000 square feet of covered storage. The Advance Base Construction Depot camp also had a Seabee heavy equipment overhaul depot. Still a depot for the base.[94]

- Seabees 98th Battalion built the Iroquois Supply Annex at Iroquois Point. Depot closed after war.

- The Navy handled aviation supplies, at Waiawa Gulch by the Waiawa river. The Navy built the Waianae Aviation Depot. Depot closed after war.

- The Navy rented storage space in Honolulu in 30 buildings during the war.

- Ship taken out of service due to damage of age were salvage for part at Waipio Point depot. Parts of Waipio Depot were operated by the WAVES. Depot closed after war.

- Tank farms. Both above and underground tank farm were built for: fuel oil, gasoline and diesel. Oil storage tanks were not hit in the 1941 attack. Red Hill Underground Fuel Storage Facility was built in 1940 as storage would be safe from an enemy aerial attack. During the war there were two large Pearl Harbor tank farms, upper and lower. Only a few tanks near the former Submarine Base remain.[95]: 178–179

- The Coal Dock, Pearl Harbor was built is 1915, was located just south of Hospital Point next to Dry Dock No. 4, at 21°20′38″N 157°57′54″W / 21.344°N 157.965°W. Coal Dock, Pearl Harbor was the first official Naval installation in Hawaii for US Navy coal fired ships. The Coal Dock was used during World War II, as older World War I ships were removed from the reserve fleet and put into active duty, due to the great demand for ships. Today the Coal Dock site is a base parking lot.

- West Loch Ammunition Depot at West Loch. Also staging area for transport, LSTs and cargo ships. By 1944 depot and dock were built. Site of West Loch Disaster, kept secret until 1960. Still in use.[96]

- Lualualei Ammunition Depot at Lualualei, also called Naval Ammunition Depot Oʻahu and now Naval Magazine Pearl Harbor. Still in use, Navy would like to move to West Loch.[97]

- Each base in Hawaii had its own local depot for its own needs and was resupplied from the large depots.

Hawaii Naval Bases

[edit]- Naval Station Pearl Harbor, Oahu FPO# 128

- Naval Submarine Base Pearl Harbor (1918–)[29]

- Naval Air Station Barbers Point, Oahu, FPO# 14

- NAS Kahului, carrier-group operations and training

- Aiea Naval Hospital, opened in July 1939, closed 1, 1949, now Camp H. M. Smith

- Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard

- Navy Receiving Barracks, Aiea, Oahu FPO# 10[56]

- Naval Section Base Bishop's Point, Oahu FPO# 15, blimp base and supply depot at 21°19′53″N 157°58′07″W / 21.3314°N 157.9685°W, now a park [98]

- Naval Section Base Pearl City

- Naval Auxiliary Landing Field Ford Island, Oahu

- Naval Section Base Hilo, Hilo, Hawaii FPO#24

- Naval Section Base Kahului, Kahului, Maui FPO# 27, support carrier-group operations and training .

- Naval Air Station Kaneohe, Kaneohe, Oahu FPO# 28, now Marine Corps Air Station Kaneohe Bay

- Naval Air Station Keehi Lagoon, Keehi Lagoon, Honolulu FPO# 29

- Naval Air Station Puʻunene, Maui FPO# 30, NAS Puunene

- NAS Maui was Kahului Airport and Maui Airport, five miles south of Kahului.

- Naval Air Field Molokai, Molokai, Maui FPO# 31, now Molokai Airport

- Naval Section Base Nawiliwili, Nawiliwili, Kauai FPO# 33

- Amphibious Air Traffic Control Waianae, Waianae Oahu (AATC) FPO# 36

- Waianae Naval Anti-Aircraft Training Center was on 42 acres at Waianae

- Amphibious Air Traffic Control Honolulu, Oahu FPO# 59 (AATG)

- Master-at-arms Ewa, Ewa Oahu (MAS) FPO# 61[99]

- Camp Andrews, Oahu, FOP# 77, Recreation center for R&R on west of Pearl Harbor near City of Nanakuli

- Camp Catlin, Oahu FPO# 91, Housing Camp east of Honolulu, shared with 5,000 Marines, and Naval Post Office.[100]

- Kewalo Basin, Oahu FPO# 78, small port

- Port Alen, Kauai FPO# 821, small harbor on Kauai's southern coast in Hanapepe Bay, also small Burns Field with two runways.[101]

- Amphibious Training Base, Kamaole, Maui FPO# 900,

- Amphibious Training Base Waimanalo (ATB), Waimanalo, Oahu FPO# 905, Start of US Navy SEAL Teams[89]

- Manana Naval Barracks, Mānana, Oahu, FPO# 919[102]

- Hickam Field, US Navy used part of base

- West Loch ammunition depot.

- Sand Island internment camp and Japanese Prisoners Of War

- Puuloa Rifle Range at Puuloa, Iroquois Point

- Aiea Naval Fire Fighting School at Aiea Bay

- Naval Base Tern Island on Tern Island, French Frigate Shoals in

- Lualualei ammunition depot.

- French Frigate Shoals FPO# 80, now French Frigate Shoals Airport, Naval Auxiliary Air Facility French Frigate Shoals opened 15 March 1943.[103]

- Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, Small US Navy base built in early 1943, after Japan anchorage off one of the islands in March 1942 as part of Operation K.[104]

- Naval Base Hawaii supported the Sand Island seaplane base on Johnston Atoll 1,514 km (940 miles) from Hawaii.

- Naval Base Hawaii supported the Kingman Reef Naval Defensive Sea Area 1,480 km (920 miles) from Hawaii.

- Naval Base Hawaii supported the base on Wake Island but it surrender to Japan in the Battle of Wake Island on December 23, 1941. Wake Island is 3,955 km (2457 miles) from Hawaii.

- Naval Base Hawaii supported the base on Palmyra Island Naval Air Station 1,704 km (1,059 miles) from Hawaii.

Naval Radio Stations

United States Coast Guard

- The United States Coast Guard was supported by the US Navy, United States Coast Guard had bases at the US Navy bases:

- Port Allen, Kauai, FPO# 43

- Hilo, Hawaii, FPO# 47 Captain of the Port Offices

- Nawiliwili, Kauai, FPO# 45

- Kahului, Maui, FPO# 46

- Honolulu, Oahu, FPO# 48 Post Office-Pier II

- Ahukini, Kauai, FPO# 44, Ahukini Landing and Ahukini Breakwater Lighthouse

Naval Inactive Ship Maintenance Facility Naval Inactive Ship Maintenance Facility at Pearl Harbor is holding base for decommissioned naval ships, waiting final fate of the ship. The ships are inactive, some are still on the Naval Vessel Register (NVR) and others have struck from the Naval Register.[105]

Current Coast Guard base

Naval Station Pearl Harbor

[edit]Naval Station Pearl Harbor was made up of a number of bases, docks, berths, and depots at Pearl Harbor:[109][110]

- Naval Submarine Base Pearl Harbor with berths S-1 to S-21

- Pearl Harbor PT Boat Base at berth S-13

- Navy Yard Pearl Harbor with berths B-1 to B-26

- Dry dock No. 1, 2 & 3 with berths DG-1 to DG-4

- Dry dock YFD-2, next to Drydock 3 (1940-1947)

- 1010 dock, a 1,010 foot wharf at the Navy Yard berth B-1, B-2 and B-3

- Bravo Docks, a 2,900 foot wharf at the Navy Yard berth B-22 to B-26

- Dry dock No. 4 at Hospital Point

- Merry Point Landing with berths M-1 to M-4

- Kuahua Depot with berths K-1 to K-11

- CINCPAC and CINCPAC Landing with berths H-1 to H-6

- CINCPAC small boat landing

- Richardson Recreation Center and boat landing

- Fire Fighting School and boat landing

- Aiea Boat Mooring and landing, Aiea with berths C-3 to C-6 and D-24

- East Lock and McGrew Point (Naval Base Hospital No. 8) with berths X-6 to X-15

- Pearl City Peninsula East Loch with berths X-16 to X18

- Pearl City Peninsula Middle Loch with berths X-21 to X23 and D-14 to D-21

- Bluff Point, Waipio with berths D-1 to D-13 (and Waipio Depot)

- Magnetic Proving Ground, Degaussing range on Beckoning Point Waipio Peninsula at 21°21′52″N 157°58′31″W / 21.3645°N 157.9753°W.[111]

- Minesweeper range Waipio Peninsula

- West Loch Ammo Depot and wharf at Powder Point

- Pearl Harbor Naval Hospital at Hospital Point

- Coal Dock south of Hospital Point with berths DE-1 to DE-6

- NAS Ford Island, Seaplane base on South Shore

- Ford Island East shore with berths F-1 to F-8, called Battleship Row and AM-2 to AM-8

- Ford Island West shore with berths F-9 to F-13 and AM-9 to AM-13

- Ford Island North shore with berths X-2 to X-6

- Advance Base Construction Depot (ABCD), next to the shipyard

- Naval Section Base Bishop's Point

- Aiea Naval Hospital

- Moanalua Ridge Naval Hospital

- Naval Headquarters

- Naval Air Station Honolulu

- Barracks and mess hall

- Motorpool

- Upper and lower tank farm, Red Hill Underground Fuel Storage Facility

Airfields

[edit]

Wheeler Army Airfield was a primary target and site of the first attack on 7 December 1941, leading up to the attack on Pearl Harbor The US Navy supported the Airfields with aviation gas, spare parts and shipped in planes. The Navy played baseball against the 7th Army Air Force (7th AAF) Fliers.

- Lyman Field now Hilo Airport[112]

- Upolu Airfield (Suiter Field), now ʻUpolu Airport[113]

- Morse Field, abandoned in 1983.

- Kalaupapa Airfield, emergency war airfield, now Kalaupapa Airport

- Homestead Airfield (Molokai Airfield) now Molokai Airport

- Oahu Airfields:

- Honolulu Airfield (John Rodgers Field) now Honolulu International Airport

- Hickam Field now Joint Base Pearl Harbor Hickam (JBPHH).

- Luke Field (Ford Island Airfield) located on Ford Island in Pearl Harbor.

- Barber's Point Field, now Kalaeloa Airport) southern coast of Oahu.

- Ewa Field now Marine Corps Air Station Ewa.

- Bellows Field now Bellows Air Force Station MCTAB.

- Wheeler Field near Wahiawa across from Schofield Barracks. (Baseball: Wheeler Field Wingmen)

- Waiele Field (Waiele Gulch Army Airfield) located next to Wheeler Field[114]

- Kaneohe Field (NAS Kaneohe) now Marine Corps Base Hawaii (MCBH).

- Kahuku Airfield now Kuilima Air Park [115]

- Haleiwa Fighter Strip, auxiliary field to Wheeler Field, civilian airport, now abandoned

- Dillingham Airfield Honolulu, general aviation airfield starting 1962

- Kipapa Airfield, closed in 1947, now gone.

- Stanley Field, closed not trace.

- Kualoa Field (Kualoa Point) built in 1942, now part of Kualoa Regional Park and Kualoa Ranch.[116]

- Naval Auxiliary Air Facility French Frigate Shoals opened 15 March 1943. Now a private use airport, French Frigate Shoals Airport.[103]

- Haleiwa Fighter Strip US Army[117]

- Mokuleia Army Airfield, then Dillingham Air Force Base[118]

- Kure Atoll Airfield was built by the Navy on the small Kure Atoll west of Hawaii.[119]

- Baker Field, the Navy built a runway on the small Outlying Island Baker[120][121]

Marine Corps Base Hawaii

[edit]The US Navy supports the current Marine Corps Base Hawaii and Marine Corps Air Station Kaneohe Bay. During the war Marine barracks were on 55 acres next to the navy yard with 29 buildings. The Marine Corps baseball team was the Camp Catlin Gators. On Moanalua Ridge the Marines had a large staging base, built by the Seabees, able to house up to 20,000 troops in 3 camps, for troops departing. Marine base depot was on 73-acre next to the Seabee Camp depot. Camp Maui was a large staging camp.[122][123] Camp Tarawa was a training camp built on the island of Hawaiʻi for the 2nd Marine Division during World War II.[124]

USO Hawaii

[edit]

With thousands of Troops stationed and passing through Hawaii, the USO Hawaii was an important part of the life of many Troops. The United Service Organizations (USO) was founded in 1941 to lift the morale of our military and nourish support on the home front. The USO was formed by having existing organizations work together to support the Troops, the first groups were: Salvation Army, Young Men's Christian Association, Young Women's Christian Association, National Catholic Community Services, National Travelers Aid Association and the National Jewish Welfare Board. USO Hawaii serve all the military bases in Hawaii. Current USO Locations are: USO Honolulu, USO Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, USO Pohakuloa Training Area, USO Schofield Barracks, USO Schofield Transitions.[125][126] USO operated Clubs, like: Hilo Downtown Club, Victory Club, Hu Welina club, Mo'oheau Park Club, Mokuola Club, Rainbow Club, Haili Street Club, Barbara Hall, Molokai Club, Honoka'a Club, Naalehu, Pahala, Pahoa and Kopoho clubs.[127][128]

One of the major events during World War II was the Bob Hope show at the Nimitz Bowl. Hope called his 1944 USO World War II military tour of the South Pacific: "Loew's Malaria Circuit" and "the Pineapple Circuit". Hope, Jerry Colonna, Frances Langford, musician guitarist Tony Romano and Patty Thomas did 150 shows in the two 1/2 months they were on road. Hope and Thomas would do soft shoe dance together in the show and Thomas would do solo tap dance numbers. So the Troops could see Patty Thomas tap dance Hope followed her around a microphone. Also on the tour were singer Gale Robbins, musicians June Brenner and Ruth Denas, and comedians Roger Price and Jack Pepper.[129] The tours visited: Naval Base Pearl Harbor Hawaii at the Nimitz Bowl, Naval Base Eniwetok, Naval Base Cairns, Green Islands, Bougainville, Milner Bay, Naval Base Treasury Islands, Naval Base Mios Woendi called Wendy Island, and Naval Base Kwajalein.[130]

Nimitz Bowl

[edit]

Nimitz Bowl (1944-1948) was a US Navy outdoor venue in the Punchbowl Crater at Aiea, Honolulu dedication was held on 14 April 1944. The US Naval's Seabees built the Nimitz Bowl with 12,000 seats in a natural Bowl, there was more seating for overflow attendees in the natural Bowl.[131] USO shows, music and sporting events. Nimitz Bowl Sporting events included wrestling and boxing. Army/Naval and Naval District Championship, boxing matches were held at the Nimitz Bowl. Nimitz Bowl was sometime call the Hill.[132][133] Bob Hope released as record album recorded at the I Never Left Home in June 1944, A tribute to the armed forces on Capitol Records.[134] Site of Nimitz Bowl is now the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific also called the Punchbowl Cemetery. Congress approved funding and construction in February 1948 for a new national cemetery in Hawaii. The new cemetery was dedicated on September 2, 1949, at the site of the former Nimitz Bowl at 21°18′46″N 157°50′47″W / 21.31278°N 157.84639°W.[135][136]

Recreation

[edit]Naval Base Hawaii was both a major staging place for troops and supplies going to more forward base and a major rear base for R&R for Troops that had been on the front lines. Due to the fear of Japanese invasion after the attack, the US government took back all regular United States dollars and replaced them with new Hawaii overprint note during the war.[137]

- Bloch Recreation Center near Merry Point, now the Bloch Arena at 21°20′49″N 157°56′28″W / 21.347°N 157.941°W.

- Richardson Recreation Center by Aiea Bay, now site of Richardson Field, Rainbow Bay A-Frame Pavilion, COMPACFLT Boathouse, part of Aloha Stadium at 21°22′N 157°56′W / 21.37°N 157.93°W. .

- Fort DeRussy was the largest recreation center on Oʻahu.

- Hana Kai Maui Resort

- Nimitz Bowl (1944-1948)

- Baseball clubs

- Camp Andrews, Nānākuli beach (Kalanianaʻole Park) rest and recreation (R&R) area [138]

- Camp Erdman, Oahu recreation camp for fleet officers, now a YMCA camp at Waialua[139]

- Submarine Base Rest and Recuperation Annex at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel

- Schofield Recreation Center, next to Schofield training center

- Waikiki Beach Recreation Center

- Ward Field, Baseball[140]

- Quick Field, Baseball [141]

- Navy Marine Golf Course, Pearl Harbor, opened in 1948[142]

- Ke'alohi Golf Course, Pearl Harbor, opened in 1965[143]

- Halsey Terrace Community Center, Pearl Harbor[144]

- JBPHH Fitness Center, Pearl Harbor, opened 2012[145]

- MWR Youth Sports Office Pearl Harbor[146]

- Hickam Bowling Center[147]

Base Baseball

[edit]

Baseball was a popular pastime in Hawaii, different bases and organizations had Baseball Clubs. Furlong Field was a baseball field built in 1943 at Naval Air Station Kaneohe. This is where some of the base's Hawaii baseball teams played. Peterson Field at Aiea Barracks was another. At Furlong Field on September 26, 1945, was the first game of the 1945 All-Star Game. The best for the base's teams played off in American League Vs. National League. About 26,000 came to the Base's 7 game All-Star Baseball Series. Admiral Chester Nimitz tossed out the first ball in Game 1. Game 6 was played at Hickam Field. Game 3 was played at Redlander Field near Schofield Barracks and Poamoho Camp at Whitmore Village. Of the 50 All-Star players in the series, 36 had played in the major leagues. Navy Fleet tournaments were also played in Hawaii.[148][149]Joe DiMaggio, hit a home run out of the Honolulu Stadium while playing for a military base team in 1944.[150][151]

- Navy All Stars (noted player: Bill Dickey, Virgil Trucks, Dom DiMaggio, Jack Hallett, Phil Rizzuto, Schoolboy Rowe, Johnny Vander Meer).

- The All-Service Women's Softball League had: Base 8 Hospital Babes, Pearl Harbor Hospital, Aiea Heights Hospital Hilltopperettes, Hawaiian Air Depot Black Widows, Pearl Harbor Shop Wahines and the Stores House

Kamaainas.

- Central Pacific Area (CPA) League Base Teams:

- Aiea Naval Barracks Maroons

- 7th Army Air Force Fliers (noted player: Joe DiMaggio, Rugger Ardizoia, Johnny Beazley, Bob Dillinger, Joe Gordon, Walt Judnich, Don Lang, Dario Lodigiani, Jerry Priddy, Red Ruffing, Charlie Silvera, and Tom Winsett)

- Pearl Harbor Submarine Base Dolphins (noted player: Al Brancato, Joe Grace, Bob Harris, Ken Sears, Rankin Johnson, Jr., Walt Masterson)

- Kaneohe NAS Klippers (noted player Tom Ferrick, Johnny Mize, Marv Felderman, Wes Schulmerich)

- Aiea Naval Hospital Hilltoppers (noted player: Jim Carlin, George Dickey, Vern Olsen, Eddie Pellagrini, Pee Wee Reese, Eddie Shokes

- Schofield Redlanders ((noted player Army: Sid Gautreaux)

- South Sector Commandos

- Wheeler Field Wingmen

- Honolulu League East Division:

- Pearl Harbor Marines (noted player: Sam Mele)

- Aiea Naval Barracks (Noted player: Johnny Lucadello, Eddie Pellagrini, Hugh Casey, Vinnie Smith and Barney McCosky, Bob Usher)

- 7th Army Air Force

- Mutual Telephone Company

- Police

- Camp Catlin Gators (USMC) (noted player: Tom Ferrick and Jim Davis)

- Coast Guard Cutters

- Atkinson Athletic Club

- Kalihi

- Tripler Army Medical Center

- Honolulu League West Division:

- Pearl Harbor Civilians

- Rainbows

- Fort Shafter

- Waikiki

- Hawaiian Air Depot

- CHA-3 Volunteers

- Engineers

- Pearl Harbor Receiving Station

- St. Louis Hospital

- Red Sox

Internment Camps

[edit]

After the attack on Pearl Harbor it was feared that some Japanese Americans might be loyal to the Empire of Japan and the Emperor of Japan after the Niihau incident. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the Secretary of War to set some military zones for the internment of Japanese Americans. Hawaii had some of the U.S. prisoner of war camps and Japanese Americans internment camps. Hawaii had more than 150,000 Japanese Americans or about one-third of Hawaii population, but only 1,200 to 1,800 were sent to the Internment camps.[152] War Relocation Authority built both temporary and permanent relocation camps. As aliens they had to register in accordance with the law and were required to turn in all weapons and short-wave radios. Even with internment, a number of American-born Japanese (or Nisei) volunteered to join the U.S. armed services. The Nisei units fought well and are highly decorated units. Nisei joined all the U.S. armed branches, most joined the U.S. Army.[153][154][155]

Post WWII

[edit]- Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum

- Battleship Missouri Memorial

- USS Arizona Memorial

- Pearl Harbor National Memorial

- Pearl Harbor Survivors Association

- USS Utah Memorial

- USS Bowfin Submarine Museum - Pacific Fleet Submarine Museum

- U.S. Army Museum of Hawaii

- Home of the Brave Hawaii-Welcome Home

- Naval Air Museum Barbers Point

- Joint Base Pearl Harbor–Hickam occupies: Hickam Field, Ford Island, former Naval Submarine Base Pearl Harbor, Hospital Point, Navy Yard Pearl Harbor, Kuahua Peninsula Depot, Merry Point, Kamehameha Beach, Hickam Beach, Navy Marine Golf Course, Ke'alohi Golf Course, Halsey Terrace Community, Forest City Community, Fort Kamehameha, Battery Jackson, and water way Southeast Loch, water way Quarry Loch and water way Magazine Loch.

Gallery

[edit]-

Joint Base Pearl Harbor–Hickam at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii 2004, center Kuahua peninsula depot.

-

Waipio Peninsula Amphibious Base near Pearl Harbor in 1944. Used in training of the island-hopping Pacific War.

-

Pearl Harbor looking southwest in October 1941, Ford Island is at its center.

-

USS R-1 at Pearl Harbor 1925

-

USS Altair (AD-11) at Pearl Harbor with destroyers on 8 February 1925

-

USS Jason (AC-12) at Pearl Harbor 18 July 1923

-

USS Chicago at Naval Submarine Base Pearl Harbor in 1926

-

Naval Air Station, Kaneohe Bay, after the Pearl Harbor raid. With burnt hanger, seaplane PBY, the 5 seaplane ramps are visible.

-

Dry Dock No. 1 opening at Pearl Harbor in 1919

-

Pearl Harbor coaling station in 1919, near radio tower No.1.

-

Pearl Harbor Submarine Escape Trainer at Submarine escape training facility

-

USS Ronquil (SS-396) entering Pearl Harbor 1944

-

Attack on Pearl Harbor by Japanese planes

-

Marine Corps Air Station Ewa, barracks for civilian housing

-

USS Langley (CV-1) in Pearl Harbor, in May 1928, the US Navy first aircraft carrier

-

Ford Island Pearl Harbor in 1930

-

Route followed by the Japanese fleet to Pearl Harbor and back

-

Haleiwa Fighter Strip in 1933

-

SCR-270 like the one that detected the attacking Pearl Harbor planes

-

Opana Radar Site first operational use of radar by the United States in wartime during the attack on Pearl Harbor

-

USS New Mexico (BB-40) at Pearl Harbor 1935

-

Japan's attacks across the Pacific

-

Auxiliary floating drydock USS YFD-2 arriving Pearl Harbor in 1940

-

Hickam Field and the Naval Yard in 1940

-

Battleship Row ship placement in 1941 attack

-

Pearl Harbor after the attack

-

USS Oklahoma salvage from shore 19 March 1943

-

Commander in Chief Pacific Fleet Headquarters in World War II, Pearl Harbor, Makalapa administration building in 1943

-

USS Arizona Memorial in 2002

-

Pearl Harbor, Hawaii in 2009 from International Space Station

-

War Shipping Administration and United States Merchant Navy routes during World War 2

-

USS Wisconsin and USS Oklahoma (BB-37) at Pearl Harbor in November 1944

-

USS Bowfin at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii a museum ship

-

US Navy Pearl Harbor, Hawaii in 2000

-

U.S. Naval Combat Demolition insignia

-

Oahu City Map.

-

ARD-29 floating repair in dry dock N0. 4 at Pearl Harbor 1951

-

USS Greeneville (SSN 772) in dry dock Pearl Harbor

-

Tripler Army Medical Center on Moanalua Ridge

-

Pearl Harbor December 7, 1941 map by US National Park. With a few present-day facilities

|

1: California

West side of Ford Island: (N to S) Detroit, Raleigh, Utah, Tangier A: Oil storage tanks, not targeted |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Hawaiian History – Hawaiʻi (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov.

- ^ Naval Base Hawaii Archived 2023-03-06 at the Wayback Machinepacificwrecks.com

- ^ a b "Shipyard Highlights – Hawaii". www.honolulumagazine.com. Archived from the original on 2018-11-30. Retrieved 2022-12-28.

- ^ "The Logistics of Advance Bases". Retrieved 11 September 2024.

- ^ Cathal J. Nolan, et al. Turbulence in the Pacific: Japanese-U.S. Relations during World War I (2000)

- ^ Development of the Naval Establishment Pearl HarborUS Navy

- ^ Island of Oahu, Attack on Pearl Harborhmdb.org

- ^ Pearl Harbor: Its Origin and Administrative History Through World War TwoUS Navy

- ^ Base PlansUS Navy

- ^ Town, Maalaea (November 12, 2021). "The Impact Of World War II On Hawaii and the Aftermath". maalaea.com.

- ^ Building BAses, Pearl Harbor and the Outlying Islands US Navy

- ^ "Hawaiian language". Wow Polynesia. December 2, 2009. Archived from the original on June 18, 2011. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ "The Search for the World War II Japanese Midget Submarine Sunk off Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941". Archived from the original on 26 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

- ^ Stewart, A.J., LCDR USN. "Those Mysterious Midgets", United States Naval Institute Proceedings, December 1974, p.55-63

- ^ Thomas 2007, pp. 57–59

- ^ "Pearl Harbor attack | Date, History, Map, Casualties, Timeline, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ Rosenberg, Jennifer (January 23, 2019), "Facts About the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor", ThoughtCo. Humanities > History & Culture, archived from the original on October 24, 2021, retrieved December 10, 2021

- ^ Fuchida 2011, chs. 19, 20

- ^ "Aircraft Attack Organization". Ibiblio.org. Archived from the original on June 23, 2011. Retrieved July 17, 2011.

- ^ Prange, Goldstein & Dillon 1988, p. 174

- ^ Pearl Harbor Attack, 7 December 1941 Carrier LocationsUS Navy

- ^ "Pearl Fleet Navy Exchange Store In Pearl Harbor, Hi | Shop Your Navy Exchange - Official Site". www.mynavyexchange.com.

- ^ "WATER IN HULL OF F-4.; Diver Also Reports That Superstructure of Submarine Has Caved In" (PDF). The New York Times. 16 April 1915. Retrieved 2011-08-24.

- ^ Johnson, Robert Erwin (2013). Far China Station: The U.S. Navy in Asian Waters, 1800–1898. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-409-0. page 195

- ^ United States Submarine Operations in World War II, by Theodore Roscoe

- ^ USS Seawolf (SS-197) Markerhmdb.org

- ^ USS Swordfish (SS-193) Markerhmdb.org

- ^ How Allied Submarines Crippled Japan in WW2youtube.com

- ^ a b Naval Submarine Base Pearl HarborUS Navy

- ^ "In the Waters of Pearl – Building the Pearl Harbor Submarine Base 1918-1945". August 17, 2017.

- ^ Morison (1949), p.188.

- ^ Lenton, H. T. American Submarines (Navies of the Second World War Series; New York: Doubleday, 1973), p.5 table.

- ^ Bulkley, Robert Johns (1962). Bulkley. p. 79.

- ^ The Navy's Gallant Sentriesusni.org

- ^ PT Boats At Pearl Harbor On 7 December 1941ptboatworld.com

- ^ PT-20 NavSource

- ^ Ford Island Luke Fieldairfields-freeman.com

- ^ Ford Island Seaplane Basepacificwrecks.com

- ^ Luke Fieldhiavps.com

- ^ Osprey Combat Aircraft 63, Aichi 99 Kanbaku 'Val' Units 1937–42, by Osamu Tagaya and Justin Taylan

- ^ Revolution in Nets: An Unglamorous But Essential Phase of Naval Warfare, by Buford Rowland, Vol. 11, No. 3, 1947), pp. 149-158

- ^ Net laying Pearl Harbor NavSource

- ^ At Dawn We Slept, The Untold Story of PEARL HARBOR, by Gordon W. Prange

- ^ Naval Air Station Kaneohe Baypearlharbor.org

- ^ Kaneohe Baypacificwrecks.com

- ^ Naval Air Station Kaneohe BayUS Navy

- ^ Kaneohe Baypacificwrecks.com

- ^ Naval Air Station Kaneoheww2db.com

- ^ Pearl Harbor and the Outlying IslandsUS Navy

- ^ "The Martin Mariner, Mars, & Marlin Flying Boats."vectorsite.net

- ^ Associated Press, "Aerial Box Car Sent To Nimitz", The Spokesman- Review, Spokane, Washington, Monday 24 January 1944, Volume 61, Number 255, page 1.

- ^ Boyne, Walter J. (July 2007). Beyond the Wild Blue (2nd edition): A History of the U.S. Air Force, 1947-2007. St. Martin's' Press. p. 465. ISBN 978-0-312-35811-2..

- ^ "Honolulu International Airport...Celebrating 80 years" (PDF). Gateway to the Pacific: Honolulu International Airport 80th Anniversary. Hawaii Department of Transportation, Airports Division. 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 23, 2012. Retrieved January 12, 2009.

John Rodgers Airport was dedicated March 21, 1927. The field was named in honor of the late Commander John Rodgers, who had been Commanding Officer of the Naval Air Station at Pearl Harbor from 1923 and 1925...

- ^ Naval Air Station Honolulu Report 1945 US Navy

- ^ Pan American Airwayshawaii.gov

- ^ a b "U.S. Naval Base, Pearl Harbor, Receiving Barracks, Willamette Street at Spruance Street, Pearl City, Honolulu County, HI". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA.

- ^ Naval Base Hospitals, page 5 US Navy

- ^ Naval Health Clinic Hawaiitricare.mil

- ^ Moanalua Ridge Naval Hospitalww2db.com, US Navy

- ^ NMRTC Pearl Harbor HIUS Navy

- ^ "Drydocking Facilities Characteristics" (PDF).

- ^ Popular Science Feb 1937, page 43

- ^ "HyperWar: Building the Navy's Bases in World War II [Chapter 9]". www.ibiblio.org.

- ^ "Floating Dry Docks". The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia.

- ^ "Civilian Casualties – Pearl Harbor National Memorial (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov.

- ^ "U.S. Naval Shipyards: Keeping the Fleet at Sea" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 23, 2014.

- ^ "Kahului Airport Information: Airport History", hawaii.gov/ogg, archived from the original on 2016-05-14

- ^ Naval Air Station Kahului2db.com

- ^ "Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields: Hawaii, Maui island". Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields.

- ^ "Maui Airport (Puunene)". aviation.hawaii.gov.

- ^ "Governor's Executive Orders Maui Airport". aviation.hawaii.gov.

- ^ Naval Air Station Puunene, aviation.hawaii.gov

- ^ McElhiney, Allan. "Charles Ivins". Naval Air Station Fort Lauderdale Museum.

- ^ "Insignia, Carrier Aircraft Service Unit CASU-21, United States Navy | National Air and Space Museum". airandspace.si.edu.

- ^ Ford, Roger (2001) The Encyclopedia of Ships, pg. 377. Amber Books, London. ISBN 9781905704439

- ^ USS Orion (AS-18)US Navy

- ^ USS Sperry tendertale.com

- ^ USS GriffinUS Navy

- ^ Brokaw, Tom (December 7, 2006). "Pearl Harbor survivor witnesses history — twice". NBC News. Archived from the original on November 11, 2013.

- ^ USS Dixie (AD-14) NavSource

- ^ Naval Historical Center – DANFS entry for PiedmontUS Navy

- ^ "Avocet I (Minesweeper No. 19)". NHHC.

- ^ USS Vestal US Navy

- ^ USS Vestal hazegray.org

- ^ "Photocopy, U.S. Navy photograph, 1945. (BMA - CP 116,995) Aerial oblique of Waipio Peninsula Amphibious Base - U.S. Naval Base, Pearl Harbor, Waipio Peninsula, Waipo Peninsula, Pearl City, Honolulu County, HI". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA.

- ^ "U.S. Naval Base, Pearl Harbor, Waipio Peninsula, Waipo Peninsula, Pearl City, Honolulu County, HI". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA.

- ^ "Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields: Hawaii: Southern Oahu Island". Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields.

- ^ "Photocopy, U.S. Navy photograph, 1944. (BMA - CP 121,957) Aerial view of Waipio Peninsula Amphibious Base - U.S. Naval Base, Pearl Harbor, Waipio Peninsula, Waipo Peninsula, Pearl City, Honolulu County, HI". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA.

- ^ a b "Hawaii". National Navy UDT-SEAL Museum.

- ^ "US Codebreakers In The Shadow Of War"airvectors.net

- ^ Naval Supplementary Radio Station Melbourne Australia stationhypo.com

- ^ Fleet Radio Unit, Melbournenavycthistory.com

- ^ "NAVSUP Fleet Logistics Center Pearl Harbor". Naval Supply Systems Command. Archived from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ Procurement and Logistics for Advance BasesUS Navy

- ^ Woodbury, David O. (1946). Builders for Battle. New York: E. P. Dutton and Company, Inc.

- ^ West Loch Ammunition Depotnavytimes.com

- ^ "Lualualei / Naval Magazine Pearl Harbor". August 28, 2020.

- ^ "U.S. Naval Base, Pearl Harbor, Naval Net Depot Storehouse & Shop, Bishop Point, Pearl City, Honolulu County, HI". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA.

- ^ "Resurrection of a Lost Battlefield: Ewa Plain (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov.

- ^ "Opening Moves: Marines Gear Up For War (Pacific Theater)". www.nps.gov.

- ^ "Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields: Hawaii, Kauai island". Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields.

- ^ Manana Naval Barracksus naVY

- ^ a b Naval Auxiliary Air Facility French Frigate Shoalspacificwrecks.com

- ^ French Frigate Shoalspacificwrecks.com

- ^ "PHNSY & IMF". www.navsea.navy.mil.

- ^ "USCG Station Honolulu". Wikimapia. 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- ^ "US Coast Guard Station Maui". United States Coast Guard. 27 June 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- ^ "United States Coast Guard District 14". United States Coast Guard. 20 August 2011. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ Thrum, Thos. G (1910). All about Hawaii. The recognized book of authentic information on Hawaii, combined with Thrum's Hawaiian annual and standard guide. Honolulu. Honolulu: Honolulu Star-Bulletin. pp. 163–164. OCLC 1663720.

- ^ "Pearl Harbor Facts". Archived from the original on 2011-03-07. Retrieved 2023-01-01.

- ^ Degaussing range on Beckoning Point Waipio Peninsula LOC.gov

- ^ "Pacific Wrecks - Hilo, Hawaii, United States". pacificwrecks.com.

- ^ "Pacific Wrecks - Hawaii (Hawaiʻi) Hawaiian Islands, United States". pacificwrecks.com.

- ^ "Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields: Hawaiii: Northern Oahu Island". Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields.

- ^ "Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields: Hawaiii: Northern Oahu Island". Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields.

- ^ "Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields: Hawaiii: Northern Oahu Island". Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields.

- ^ "Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields: Hawaiii: Northern Oahu Island". Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields.

- ^ "Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields: Hawaiii: Northern Oahu Island". Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields.

- ^ "Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields: Western Pacific Islands".

- ^ "Pacific Wrecks - Baker Island Airfield (Baker Airfield) Minor Outlying Islands, United States". pacificwrecks.com.

- ^ "Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields: Western Pacific Islands". Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields.

- ^ "PHNG Kaneohe Bay Marine Corps Air Station (Marion E Carl Field)". Airnav.com. 21 May 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ Marine Corps Base Hawaiimarines.mil

- ^ Johnston, Richard (1948). Follow Me: The Story of the Second Marine Division in World War II. New York: Random House. p. 166. ASIN B000WLAD86.

- ^ USO Hawaiihawaii.uso.org

- ^ About USO Hawaiiuso.org

- ^ Inside the Archives: Down Honolulu Way: The USO and The Navy in Hawaii 1942-1947ijnhonline.org

- ^ USO Clubshistorichawaii.org

- ^ Bob Hope Tour 1944eaglehorse.org

- ^ Patty Thomas gallery loc.gov

- ^ Nimitz Bowl The Honolulu Advertiser, Honolulu, Hawaii, 12 April 1944, Page 8

- ^ Naval District ChampionshipUS Navy

- ^ NAVY BOXERS TRIUMPH, 4-3; Beat Army in Bouts Dedicating Nimitz Bowl at Pearl Harbor, May 24, 1944. NY Times.

- ^ I Never Left Home discogs.com

- ^ "Hawaii Volcano Crater has new 25-bell Carillon" (PDF). The Diapason. 47 (3): 6. February 1, 1956. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 12, 2022. Retrieved December 27, 2022.

- ^ "Korean War Exchange of Dead – Operation GLORY". Qmmuseum.lee.army.mil. Archived from the original on December 28, 2007. Retrieved 2013-11-13.

- ^ Krauss, Bob (2005-07-27). "Wartime currency not so rare". Honolulu Advertiser. Archived from the original on 2014-07-12. Retrieved 2009-07-10.

- ^ Camp Andrews imagesofoldhawaii.com

- ^ Camp Erdman, by Susan Kang Sunderland on June 7, 2016, midweek.com

- ^ Ward Field, Baseballloc.gov

- ^ Quick Fieldaf.mil

- ^ Navy Marine Golf Coursemilitary.com

- ^ Ke'alohi Golf Coursehawaiigolf.com

- ^ alsey Terrace Communityohananavycommunities.com

- ^ BPHH Fitness Centerextdesignllc.com

- ^ WR Youth Sports Office Pearl Harbor hawaii.armymwr.com

- ^ "Hickam Bowling Center". www.greatlifehawaii.com.

- ^ War me Baseball in Hawaii - Baseball in Wartimebaseballinwartime.com

- ^ "The 1945 All-Star Game: The Baseball Navy World Series at Furlong Field, Hawaii – Society for American Baseball Research".

- ^ Machado, Carl (June 5, 1944). "DiMaggio Homers Over Left Wall". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. p. 8. Retrieved January 24, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Joe DiMaggio and the 7th AAF March 24, 2017, By Howard E. Halvorsen af.mil

- ^ Ogawa, Dennis M. and Fox, Jr., Evarts C. Japanese Americans, from Relocation to Redress. 1991, p. 135.

- ^ Ng, Wendy L. (2002). Japanese American Internment During World War II: A History and Reference Guide. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-31375-2.

- ^ Semiannual Report of the War Relocation Authority, for the period January 1 to June 30, 1946, not dated. Papers of Dillon S. Myer. Scanned image at Archived 2018-06-16 at the Wayback Machine trumanlibrary.org. Retrieved September 18, 2006.

- ^ "The War Relocation Authority and The Incarceration of Japanese Americans During World War II: 1948 Chronology," Web page Archived 2020-11-12 at the Wayback Machine at www.trumanlibrary.org. Retrieved September 11, 2006.

External links

[edit]Sources

[edit]- Fuchida, Mitsuo (2011), For That One Day: The Memoirs of Mitsuo Fuchida, Commander of the Attack on Pearl Harbor, translated by Shinsato, Douglas; Urabe, Tadanori, Kamuela, Hawaii: eXperience, ISBN 978-0-9846745-0-3

- Prange, Gordon William; Goldstein, Donald M.; Dillon, Katherine V. (1988), December 7, 1941: The Day the Japanese Attacked Pearl Harbor, McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-050682-4

- Thomas, Evan (2007), Sea of Thunder: Four Commanders and the Last Great Naval Campaign 1941–1945, Simon and Schuster, ISBN 978-0-7432-5222-5, archived from the original on September 6, 2015, retrieved June 27, 2015