Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sadhu

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

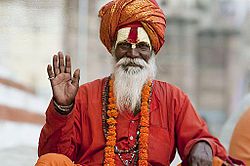

Sadhu (Sanskrit: साधु, IAST: sādhu (male), sādhvī or sādhvīne (female), also spelled saddhu) is a religious ascetic, mendicant or any holy person in Hinduism and Jainism who has renounced the worldly life.[1][2][3] They are sometimes alternatively referred to as yogi, sannyasi or vairagi.[1]

Sādhu means one who follows a path of sadhana(spiritual discipline).[4] Although the vast majority of sādhus are yogīs, not all yogīs are sādhus. A sādhu's life is solely dedicated to achieving mokṣa (liberation from the cycle of death and rebirth), the fourth and final aśrama (stage of life), through meditation and contemplation of Brahman. Sādhus often wear simple clothing, such as saffron-coloured clothing in Hinduism and white or nothing in Jainism, symbolising their sannyāsa (renunciation of worldly possessions). A female mendicant in Hinduism and Jainism is often called a sadhvi, or in some texts as aryika.[2][3]

In Sikhism, a person who has become Brahmgiani is considered a sadhu. However, asceticism, celibacy and begging are prohibited in Sikhism.[5]

Etymology

[edit]

The term sadhu (Sanskrit: साधु) appears in Rigveda and Atharvaveda where it means "straight, right, leading straight to goal", according to Monier Monier-Williams.[6][note 1] In the Brahmanas layer of Vedic literature, the term connotes someone who is "well disposed, kind, willing, effective or efficient, peaceful, secure, good, virtuous, honourable, righteous, noble" depending on the context.[6] In the Hindu Epics, the term implies someone who is a "saint, sage, seer, holy man, virtuous, chaste, honest or right".[6]

The Sanskrit terms sādhu ("good man") and sādhvī ("good woman") refer to renouncers who have chosen to live lives apart from or on the edges of society to focus on their own spiritual practices.[7]

The words come from the root sādh, which means to "reach one's goal", "straighten", or "master".[8] The same root is used in the word sādhanā, which means "spiritual practice".[4]

Demographics and lifestyle

[edit]Sadhus are widely considered holy.[9] It is also thought that the austere practices of the sadhus help to burn off their karma and that of the community at large. Thus seen as benefiting society, sadhus are supported by donations from many people. However, reverence of sadhus is by no means universal in India. For example, Nath yogi sadhus have been viewed with a certain degree of suspicion particularly amongst the urban populations of India, but they have been revered and are popular in rural India.[10][11]

There are naked (digambara, or "sky-clad") sadhus who wear their hair in thick dreadlocks called jata. Sadhus engage in a wide variety of religious practices. Some practice asceticism and solitary meditation, while others prefer group praying, chanting or meditating. They typically live a simple lifestyle, and have very few or no possessions. Many sadhus have rules for alms collection, and do not visit the same place twice on different days to avoid bothering the residents. They generally walk or travel over distant places, homeless, visiting temples and pilgrimage centers as a part of their spiritual practice.[12][13] Celibacy is common, but some sects experiment with consensual tantric sex as a part of their practice. Sex is viewed by them as a transcendence from a personal, intimate act to something impersonal and ascetic.[14]

Sadhu sects

[edit]

Hinduism

[edit]Shaiva sadhus are renunciants devoted to Shiva, and Vaishnava sadhus are renouncers devoted to Vishnu (or his avatars, such as Rama or Krishna). The Vaishnava sadhus are sometimes referred to as vairagis.[1] Less numerous are Shakta sadhus, who are devoted to Shakti. Within these general divisions are numerous sects and sub-sects, reflecting different lineages and philosophical schools and traditions often referred to as "sampradayas". Each sampradaya has several "orders" called parampara based on the lineage of the founder of the order. Each sampradaya and parampara may have several monastic and martial akharas.

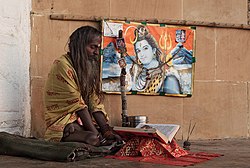

Within the Shaiva sadhus are many subgroups. Most Shaiva sadhus wear a Tripundra mark on their forehead, dress in saffron, red or orange-coloured clothes, and live a monastic life. Some sadhus such as the Aghori share the practices of ancient Kapalikas, in which they beg with a skull, smear their body with ashes from the cremation ground, and experiment with substances or practices that are generally abhorred by society.[15][16]

Among the Shaiva sadhus, the Dashanami Sampradaya belong to the Smarta Tradition. They are said to have been formed by the philosopher and renunciant Adi Shankara, believed to have lived in the 8th century CE, though the full history of the sect's formation is not clear. Among them are the Naga subgroups, naked sadhu known for carrying weapons like tridents, swords, canes, and spears. Said to have once functioned as an armed order to protect Hindus from the Mughal rulers, they were involved in a number of military defence campaigns.[17][18] Generally in the ambit of non-violence at present, some sections are known to practice wrestling and martial arts. Their retreats are still called chhaavni or armed camps (akhara), and mock duels are still sometimes held between them.

Female sadhus (sadhvis) exist in many sects. In many cases, the women that take to the life of renunciation are widows, and these types of sadhvis often live secluded lives in ascetic compounds. Sadhvis are sometimes regarded by some as manifestations or forms of the Goddess, or Devi, and are honoured as such. There have been a number of charismatic sadhvis that have risen to fame as religious teachers in contemporary India, e.g. Anandamayi Ma, Sarada Devi, Mata Amritanandamayi, and Karunamayi.[19]

Jainism

[edit]The Jain community is traditionally discussed in its texts with four terms: sadhu (monks), sadhvi or aryika (nuns), sravaka (laymen householders) and sravika (laywomen householders). As in Hinduism, the Jain householders support the monastic community.[2] The sadhus and sadhvis are intertwined with the Jain lay society, perform murtipuja (Jina idol worship) and lead festive rituals, and they are organized in a strongly hierarchical monastic structure.[20]

There are differences between the Digambara and Śvetāmbara sadhus and sadhvi traditions.[20] The Digambara sadhus own no clothes as a part of their interpretation of Five vows, and they live their ascetic austere lives in nakedness. The Digambara sadhvis wear white clothes. The Śvetāmbara sadhus and sadhvis both wear white clothes. According to a 2009 publication by Harvey J. Sindima, Jain monastic community had 6,000 sadhvis of which less than 100 belong to the Digambara tradition and rest to Śvetāmbara.[21]

Festive gatherings

[edit]

Kumbh Mela, a mass gathering of sadhus from all parts of India, takes place every three years at one of four points along sacred rivers throughout India. In 2007, it was held in Nasik, Maharashtra. Peter Owen-Jones filmed one episode of "Extreme Pilgrim" there during this event. It took place again in Haridwar in 2010.[22] Sadhus of all sects join in this reunion. Millions of non-sadhu pilgrims also attend the festivals, and the Kumbh Mela is the largest gathering of human beings for a single religious purpose on the planet. The Kumbh Mela of 2013 started on 14 January of that year at Allahabad.[23] At the festival, sadhus appear in large numbers, including those "completely naked with ash-smeared bodies, [who] sprint into the chilly waters for a dip at the crack of dawn".[24]

Gallery

[edit]- Sadhu

-

Sadhu in Orchha

-

A sadhu in Kathmandu, Nepal

-

Sadhu in Orchha, Madhya Pradesh

-

Sadhus walking on Durbar Square, Kathmandu

-

Sadhu from Vārāņsī

-

Sadhu by the Ghats on the Ganges

-

Sadhus at Kathmandu Durbar Square

-

A sadhu playing flute

-

Sadhu in Varanasi, India.

-

Sadhu at Kaathe Swyambhu, Kathmandu

-

Sadhu in India

-

Sadhvi or female Sadhu at the Gangasagar Fair transit camp, Kolkata

-

Sadhu at a river bank

-

Sadhu in Nepal

-

Shiva sadhu in Pushkar, India

-

Sadhu in Pashupatinath Temple, Kathmandu, Nepal

-

A female sādhvī in Chanpatia, India, 1906.

-

A sadhu at a market in Debe, Trinidad and Tobago

-

A sadhu at Bhadrachalam on the eve of Ram Navami

See also

[edit]- Types

- Lineage

- Lifestyle

- Personalities

Notes

[edit]- ^ See for example:

अग्ने विश्वेभिः स्वनीक देवैरूर्णावन्तं प्रथमः सीद योनिम् । कुलायिनं घृतवन्तं सवित्रे यज्ञं नय यजमानाय साधु ॥१६॥ – Rigveda 6.15.16 (Rigveda Hymn सूक्तं ६.१५, Wikisource)

प्र यज्ञ एतु हेत्वो न सप्तिरुद्यच्छध्वं समनसो घृताचीः । स्तृणीत बर्हिरध्वराय साधूर्ध्वा शोचींषि देवयून्यस्थुः ॥२॥ – Rigveda 7.43.2 (Rigveda Hymn सूक्तं ७.४३, Wikisource)

यथाहान्यनुपूर्वं भवन्ति यथ ऋतव ऋतुभिर्यन्ति साधु । यथा न पूर्वमपरो जहात्येवा धातरायूंषि कल्पयैषाम् ॥५॥ – Rigveda 10.18.5 (Rigveda Hymn सूक्तं १०.१८, Wikisource), etc.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "sadhu and swami | Hindu ascetic | Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ a b c Jaini 1991, p. xxviii, 180.

- ^ a b Klaus K. Klostermaier (2007). A Survey of Hinduism: Third Edition. State University of New York Press. p. 299. ISBN 978-0-7914-7082-4.

- ^ a b ″Autobiography of an Yogi″, Yogananda, Paramhamsa, Jaico Publishing House, 127, Mahatma Gandhi Road, Bombay Fort Road, Bombay (Mumbai) – 400 0023 (ed.1997) p.16

- ^ Winternitz, M., History of Indian Literature. Tr. S. Ketkar. Calcutta, 1927

- ^ a b c Sadhu, Monier Williams Sanskrit English Dictionary with Etymology, Oxford University Press, page 1201

- ^ Flood, Gavin. An introduction to Hinduism. (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1996) p. 92. ISBN 0-521-43878-0

- ^ Arthur Anthony Macdonell. A Practical Sanskrit Dictionary. p. 346.

- ^ Dolf Hartsuiker. Sadhus and Yogis of India Archived 15 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ White, David Gordon (2012), The Alchemical Body: Siddha Traditions in Medieval India, University of Chicago Press, pp. 7–8

- ^ David N. Lorenzen and Adrián Muñoz (2012), Yogi Heroes and Poets: Histories and Legends of the Naths, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-1438438900, pages x-xi

- ^ M Khandelwal (2003), Women in Ochre Robes: Gendering Hindu Renunciation, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791459225, pages 24-29

- ^ Mariasusai Dhavamony (2002), Hindu-Christian Dialogue: Theological Soundings and Perspectives, ISBN 978-9042015104, pages 97-98

- ^ Gavin Flood (2005), The Ascetic Self: Subjectivity, Memory and Tradition, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521604017, Chapter 4 with pages 105-107 in particular

- ^ Gavin Flood (2008). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. John Wiley & Sons, pp. 212–213, ISBN 978-0-470-99868-7

- ^ David N. Lorenzen (1972). The Kāpālikas and Kālāmukhas: Two Lost Śaivite Sects. University of California Press, pp. 4-16, ISBN 978-0-520-01842-6

- ^ 1953: 116; cf. also Farquhar 1925; J. Ghose 1930; Lorenzen 1978

- ^ "The Wrestler's Body". Publishing.cdlib.org. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Home – Amma Sri Karunamayi". Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ a b Cort, John E. (1991). "The Svetambar Murtipujak Jain Mendicant". Man. 26 (4). Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland: 651–671. doi:10.2307/2803774. JSTOR 2803774.

- ^ Harvey J. Sindima (2009). Introduction to Religious Studies. University Press of America. pp. 100–101. ISBN 978-0-7618-4762-5.

- ^ Yardley, Jim; Kumar, Hari (14 April 2010). "Taking a Sacred Plunge, One Wave of Humanity at a Time". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- ^ "Lakhs of pilgrims flock to Allahabad as Maha Kumbh Mela begins". NDTV.

- ^ Pandey, Geeta (14 January 2013). "Kumbh Mela: 'Eight million' bathers on first day of festival". BBC News.

Further reading

[edit]- Jaini, Padmanabh S. (1991), Gender and Salvation: Jaina Debates on the Spiritual Liberation of Women, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-06820-3

- Indian Sadhus, by Govind Sadashiv Ghurye, L. N. Chapekar. Published by Popular Prakashan, 1964.

- Sadhus of India: The Sociological View, by Bansi Dhar Tripathi. Published by Popular Prakashan, 1978.

- The Sadhu: A Study in Mysticism and Practical Religion, by Burnett Hillman Streeter, Aiyadurai Jesudasen Appasamy. Published by Mittal, 1987. ISBN 0-8364-2097-7.

- The Way of the Vaishnava Sages: A Medieval Story of South Indian Sadhus : Based on the Sanskrit Notes of Vishnu-Vijay Swami, by N. S. Narasimha, Rāmānanda, Vishnu-Vijay. Published by University Press of America, 1987. ISBN 0-8191-6061-X.

- Sadhus: The Holy Men of India, by Rajesh Bedi. Published by Entourage Pub, 1993. ISBN 81-7107-021-3.

- Sadhus: Holy Men of India, by Dolf Hartsuiker. Published by Thames & Hudson, 1993. ISBN 0-500-27735-4.

- The Sadhus and Indian Civilisation, by Vijay Prakash Sharma. Published by Anmol Publications PVT. LTD., 1998. ISBN 81-261-0108-3.

- Women in Ochre Robes: Gendering Hindu Renunciation, by Meena Khandelwal. Published by State University of New York Press, 2003. ISBN 0-7914-5922-5.

- Wandering with Sadhus: Ascetics in the Hindu Himalayas, Sondra L. Hausner, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-253-21949-7

- Naked in Ashes, Paradise Filmworks International – Documentary on Naga Sadhus of Northern India.

External links

[edit]- Sadhus and Yogis of India

- "Sadhus from India"—Extract from The Last Free Men by José Manuel Novoa

- "Interview of a Sadhu Living Inside a Cave in the Himalayas"—Episode from Ganga Ma: A Pilgrimage to the Source by Pepe Ozan and Melitta Tchaicovsky

Sadhu

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Terminology

Historical Development

The origins of the sadhu tradition can be traced to ancient Vedic literature, where early ascetics known as keshins (long-haired ones) appear in the Rigveda as ecstatic wanderers embodying divine inspiration and renunciation of worldly ties. These figures, described in hymns like Rigveda 10.136, roamed freely, their matted locks symbolizing detachment and connection to the divine, laying the groundwork for later ascetic practices.[9] The Upanishads, emerging around 800–200 BCE, deepened this foundation by emphasizing sannyasa (complete renunciation) as an essential stage for realizing the self (atman) and ultimate liberation (moksha), portraying ascetics as seekers who abandon material life to pursue philosophical inquiry and meditation.[10] During the classical period of Hinduism (c. 200 BCE–500 CE), the tradition evolved through legal and philosophical texts that formalized asceticism within the life stages (ashramas). The Manusmriti, a key Dharma-shastra composed around the 2nd century BCE to 2nd century CE, delineates four ashramas: brahmacharya (student), grihastha (householder), vanaprastha (forest hermit), and sannyasa (renunciate), positioning the sadhu-like sannyasin as the culmination of spiritual progression, free from societal obligations and focused on eternal truths.[11] This framework integrated renunciation into orthodox Hindu life, influencing the proliferation of wandering ascetics who embodied these ideals. In the medieval era (c. 500–1500 CE), the sadhu tradition diversified under the influences of Bhakti and Tantric movements, which democratized devotion and esoteric practices. The Bhakti movement, flourishing from the 7th century onward, encouraged personal surrender to deities through emotional devotion, attracting ascetics who combined renunciation with itinerant preaching across regions like South India and the Deccan.[12] Concurrently, Tantric traditions, particularly the Nath Sampradaya founded by Gorakhnath (c. 11th–12th century), elevated yogic asceticism, with sadhus practicing hatha yoga, alchemy, and non-dual philosophy to transcend the body and achieve immortality, often forming organized groups of wandering avdhutas.[13] A pivotal figure in formalizing the tradition was Adi Shankara (c. 788–820 CE), who revitalized Advaita Vedanta and established the Dashanami monastic orders, unifying disparate ascetic lineages under ten philosophical names (dashanami) and four cardinal mathas (monasteries) to propagate non-dualistic teachings.[14] These orders institutionalized sadhu practices, emphasizing scriptural study and renunciation while countering heterodox challenges. During the colonial period (18th–20th centuries), British policies severely impacted wandering sadhus, viewing them as potential threats due to their mobility and occasional militancy, which disrupted traditional pilgrimages and networks.[15] Sadhus played roles in resistance, including the 1857 Indian Rebellion, where figures like the Naga sadhus and other ascetics aided sepoys by spreading anti-colonial messages, providing shelter, and participating in uprisings against British annexations and cultural impositions.[16]Etymology and Definitions

The term "sadhu" originates from the Sanskrit word sādhu (साधु), which fundamentally denotes "straight," "good," or "virtuous," derived from the root sadh meaning "to go straight" or "to accomplish."[17] Over time, this evolved to signify a person embodying spiritual purity and ethical rectitude, particularly one who has attained a state of moral and devotional excellence through disciplined practice (sadhana).[4] In classical Sanskrit literature, sādhu initially referred to an upright or righteous individual in ethical contexts, but by later periods, it came to specifically designate an ascetic or holy figure committed to renunciation and divine pursuit.[18] While "sadhu" encompasses a broad category of ascetics who pursue spiritual discipline, it is distinct from related terms in Indian traditions. A sannyasi represents the full renouncer in the fourth stage of life (ashrama), having formally abandoned worldly ties as outlined in Hindu scriptures on renunciation.[19] In contrast, a yogi emphasizes meditative and yogic practices for self-realization, not necessarily involving complete mendicancy.[19] The title baba serves as an informal honorific for elder sadhus or spiritual guides, often denoting respect rather than a specific ascetic path.[19] The term appears with variations across regional Indian languages, retaining its core connotations while adapting phonetically; for instance, it is rendered as "sadhu" in Hindi and "sādu" (சாது) in Tamil, both implying a virtuous or holy person.[20] Scriptural definitions further refine its meaning, as seen in the Bhagavad Gita's Chapter 18, "Moksha Sannyasa Yoga," which elaborates on true renunciation (sannyasa) as the relinquishment of selfish actions while performing duties selflessly, aligning with the sadhu's virtuous detachment from material outcomes.[21] Conceptually, "sadhu" transitioned from denoting an ethical "good person" in early Vedic and Upanishadic texts—where it described individuals of moral integrity—to representing the ascetic mendicant in post-Vedic literature like the Puranas, which portray sadhus as wandering devotees exemplifying devotion and austerity.[22] This shift reflects broader developments in Hindu thought, emphasizing spiritual accomplishment over mere ethical conduct.[23]Types and Sects

Hindu Sadhus

Hindu sadhus represent a diverse array of ascetic orders within Hinduism, organized primarily into monastic institutions known as akharas, which serve as both spiritual communities and custodians of tradition. These akharas trace their origins to medieval reforms by saints like Adi Shankaracharya and emphasize renunciation, discipline, and devotion to specific deities. The major akharas include the Juna Akhara, the largest Shaiva order with over 400,000 members, renowned for its Naga sadhus who practice extreme austerities and lead ceremonial processions.[24] Another prominent one is the Niranjani Akhara, a Shaiva institution that coordinates rituals and maintains order during large gatherings.[25] These akharas play a central role in governing the Kumbh Mela, where they determine the sequence of royal baths (shahi snan), oversee security for pilgrims, and preserve ancient Hindu practices through structured hierarchies led by mahants and mahamandaleshwars.[26] Sectarian divisions among Hindu sadhus reflect Hinduism's polytheistic framework, with primary affiliations to Shaiva, Vaishnava, Shakta, and Udasi traditions. Shaiva sadhus, devotees of Shiva, often smear their bodies with sacred ash (vibhuti) as a symbol of renunciation and impermanence, aligning with ascetic ideals of detachment from worldly illusions.[27] Vaishnava sadhus honor Vishnu and his avatars, marking their foreheads with vertical tilak lines using clay or sandalwood paste to signify devotion and purity, including orders like the Ramanandi.[28][3] Shakta sadhus revere the Divine Mother (Shakti) in forms like Durga or Kali, incorporating tantric rituals that emphasize feminine energy and cosmic power. Udasi sadhus, influenced by Sikh founder Guru Nanak's son Sri Chand, adopt a non-sectarian approach blending Hindu and Sikh elements, promoting universal spirituality without strict deity exclusivity. Initiation into the sadhu life occurs through diksha, a sacred rite administered by a guru that involves mantra transmission, vows of renunciation, and often a symbolic funeral rite to sever ties with family and society. Most sadhus take the vow of brahmacharya, lifelong celibacy, to channel energy toward spiritual realization, while tantric traditions may allow householders to engage in esoteric practices.[29] These processes vary by akhara but universally require rigorous training in meditation, scripture study, and service. Philosophically, Hindu sadhus draw from non-dualistic schools like Advaita Vedanta, which posits the unity of individual soul (atman) and ultimate reality (Brahman), influencing many Shaiva orders toward contemplative renunciation. Devotional Bhakti traditions, emphasizing personal love for the divine, underpin Vaishnava and Shakta sadhus, fostering paths of surrender and grace over intellectual inquiry.[30] An estimated 4 to 5 million Hindu sadhus reside in India as of the 2020s, with major centers in Varanasi, a hub for Shaiva and Shakta ascetics along the Ganges, and Haridwar, a gateway for Himalayan orders participating in riverine pilgrimages.[31]Jain Sadhus

In Jainism, sadhus represent the pinnacle of ascetic renunciation, embodying the path to spiritual liberation through extreme discipline and detachment from worldly attachments. Male ascetics are termed sadhu or muni, denoting those who have fully renounced lay life to pursue meditation, scriptural study, and ethical conduct, while female counterparts are known as sadhvi.[32] These terms underscore the gender-specific roles within the monastic order, where sadhus and sadhvis form the core of the sangha, the fourfold community alongside lay followers. Jain sadhus belong to two primary sects: Digambara and Svetambara, distinguished by their approach to clothing and possessions as symbols of non-attachment. Digambara sadhus, meaning "sky-clad," practice complete nudity to signify total renunciation, believing that any covering contradicts the ideal of absolute non-possession; this tradition traces back to the sect's foundational principles emphasizing nudity as essential for moksha. In contrast, Svetambara sadhus, or "white-clad," wear simple white robes, viewing minimal clothing as permissible for practical reasons without compromising core vows, a practice rooted in their scriptural interpretations allowing for such accommodations.[32][33] At the heart of a Jain sadhu's life are the five great vows, or mahavratas, observed in their strictest form to purify the soul and halt karmic influx. These include ahimsa (absolute non-violence toward all living beings, extending to thoughts, words, and actions); satya (truthfulness in speech and intent, avoiding all falsehoods); asteya (non-stealing, refraining from taking anything not freely given); brahmacharya (complete celibacy, eliminating all sexual impulses); and aparigraha (non-possession, relinquishing all material attachments including clothing in Digambara practice). Unlike lay followers who observe milder anuvratas, sadhus uphold these vows without exception, as they form the ethical foundation for shedding karma and attaining liberation.[34][35] The journey to becoming a full sadhu begins with the novice stage as a brahmachari (or brahmacharini for women), where candidates undergo preliminary training in ethical conduct, scriptural learning, and partial vows under a guru's guidance, often lasting months or years to test commitment. Full initiation, known as diksha, marks the transition to muni or sadhvi status through a ceremonial renunciation, involving the public acceptance of the mahavratas and receipt of monastic items like alms bowls (for Svetambaras) or peacock feathers for sweeping paths to avoid harming insects. Advanced sadhus may eventually undertake sallekhana, a voluntary fast unto death practiced in terminal illness or advanced age, aimed at thinning bodily attachments and karmic residues for a pure exit from the cycle of rebirth.[36] Estimates place the total number of Jain sadhus and sadhvis in India at around 20,000, with the majority concentrated in western states like Rajasthan and Gujarat, where strong lay support networks sustain monastic wandering and alms collection.[37] This distribution aligns with the broader Jain population, which is predominantly urban and prosperous in these regions, providing essential resources for the ascetics' itinerant lifestyle. Philosophically, Jain sadhus pursue moksha—eternal liberation of the soul—by systematically shedding accumulated karma, viewed as subtle material particles that bind the inherently pure jiva (soul) to the cycle of rebirth. This process, guided by the nine tattvas (fundamentals) including influx (asrava), bondage (bandha), and exhaustion (nirjara), emphasizes rigorous self-discipline over divine grace. Unlike Hindu concepts where maya represents cosmic illusion obscuring Brahman, Jainism treats karma as a tangible obstruction removable through personal effort, without reliance on illusion-dispelling knowledge alone.[38]Lifestyle and Practices

Daily Routines and Renunciation

The renunciation process for a sadhu typically begins with initiation rites under the guidance of a guru, marking the formal abandonment of family ties, material possessions, and caste identity to embrace a life of spiritual detachment.[39] This initiation often includes a symbolic funeral ritual, known as the antyeshti samskara adapted for the living, where the aspirant is considered "dead" to worldly society, severing legal and social obligations such as inheritance or familial duties.[40] Through these rites, the individual adopts a new spiritual name and vows of poverty, chastity, and non-violence, fully committing to sannyasa or ascetic orders.[41] A sadhu's daily schedule emphasizes discipline and introspection, commencing at dawn with ablutions in a river or natural water source followed by prolonged meditation to attune the mind to divine contemplation.[42] Mid-morning involves madhukari, the traditional practice of begging alms by collecting small portions of food from multiple households, akin to a bee gathering nectar without depleting any single source, to foster humility and dependence on providence.[43] The afternoon is dedicated to scriptural study, reciting texts like the Upanishads or Bhagavad Gita, while evenings may feature discourses or satsang with fellow ascetics or devotees to share spiritual insights.[44] Sadhus maintain minimal living arrangements, often leading a parivrajaka existence as wandering mendicants without a fixed abode, traversing pilgrimage routes or forests to avoid attachment to place.[45] Some settle in ashrams, caves, or mathas for periods of intense practice, but even then, possessions are limited to essentials like a kamandalu (a simple water pot symbolizing purity and self-sufficiency) and a danda (staff representing support from the divine).[46] This austere setup reinforces detachment from material comforts, with shelter sought under trees or in temporary kutirs during travels.[6] Dietary habits among sadhus adhere strictly to vegetarianism, rooted in ahimsa (non-violence), consuming only sattvic foods such as fruits, dairy, grains, and vegetables to promote mental clarity and spiritual purity.[6] Many observe fasting on Ekadashi, the eleventh lunar day, abstaining from grains and pulses to detoxify the body and heighten devotion, often sustaining on water, milk, or fruits alone.[47] Certain sects, particularly Vaishnava sadhus, avoid root vegetables like onions, garlic, and potatoes, viewing them as tamasic and disruptive to meditative states.[48] Social detachment defines the sadhu's ethos, with no permanent residence or familial anchors, enabling complete focus on moksha (liberation) while relying on dana—voluntary offerings from lay devotees for sustenance.[49] This dependence on dana, especially anna dana (food gifts), cultivates interdependence between ascetics and householders, as alms are given without expectation of return, purifying both giver and receiver.[50] By eschewing ownership and societal roles, sadhus embody vairagya (dispassion), wandering freely to inspire ethical living among communities.[39]Ascetic Disciplines and Symbols

Sadhus engage in a range of physical austerities to transcend bodily attachments and cultivate spiritual discipline. Hindu sadhus often maintain a dhuni, an eternal sacred fire ritual performed multiple times daily, which serves as a means of purification, invoking divine blessings and representing the transformative power of fire in ascetic worship.[51] Additionally, many undertake mauna, a vow of prolonged silence akin to being inert like wood (kashtha mauna), aimed at controlling speech, fostering inner quietude, and achieving deeper meditative states.[52] Symbolic markers distinguish sadhu sects and signify their devotional affiliations. Shaiva sadhus commonly wear rudraksha beads, derived from the Elaeocarpus ganitrus tree and associated with Lord Shiva, believed to embody tears of compassion and aid in spiritual protection and meditation.[53] In contrast, Vaishnava sadhus don tulsi necklaces made from the sacred basil plant (Ocimum tenuiflorum), revered as an incarnation of the goddess and essential for devotion to Vishnu, promoting purity and divine connection.[54] Dreadlocks (jata) are prevalent among many Hindu ascetics, emulating Shiva's matted hair as a sign of renunciation and untamed spiritual energy, while vibhuti—sacred ash applied to the body—represents the impermanence of life and Shiva's transformative essence for Shaivas.[3] Mental disciplines form the core of sadhu spiritual cultivation, emphasizing inner transformation. Practices such as yoga asanas and pranayama breathing exercises are employed to regulate vital energy (prana), preparing the body for higher states of awareness.[55] Mantra recitation, often chanted repetitively, facilitates kundalini awakening—the uncoiling of dormant spiritual energy at the spine's base—leading to profound meditative experiences and self-realization.[56] Endurance practices test the sadhu's detachment from worldly comforts and build resilience. Exposure to natural elements, such as meditating in extreme weather without shelter, and limiting sleep to minimal hours cultivate tolerance (titiksha) and focus on the eternal self over physical needs.[57] Pilgrimages known as tirtha yatra, including rigorous circumambulations of sacred hills like those around Mount Kailash or during Kumbh Mela circuits, embody devotional perseverance, covering vast distances on foot to accrue spiritual merit and purify the soul.[58] While traditional claims attribute longevity to these ascetic disciplines through caloric restriction and spiritual purity, enhancing vitality and delaying aging,[59] studies on sadhu populations indicate associated health risks, including hypertension (29.6%), diabetes (6%), overweight or obesity (36.6%), and anemia (20.2% as of a 2022 cross-sectional study of 960 ascetics), often undiagnosed and linked to irregular diets and physical strain.[60][61] These findings underscore the need for balanced health awareness amid their austere lifestyles.Social and Cultural Role

Spiritual Guidance and Influence

Sadhus play a pivotal role as spiritual teachers within Hindu communities, employing oral discourses known as katha to expound upon scriptures, myths, and ethical dilemmas, thereby imparting lessons on dharma and moral conduct to both disciples and lay audiences.[62] These sessions often occur in ashrams or during pilgrimages, where sadhus use storytelling to make complex philosophical concepts accessible and inspire personal transformation. Additionally, they initiate disciples through rituals such as diksha, formally guiding them into ascetic practices or devotional paths while emphasizing self-discipline and renunciation as exemplars of righteous living. In lay society, sadhus exert influence as moral authorities, offering counsel on ethical matters. Their visible renunciation—abstaining from material possessions and worldly ties—serves as a powerful model, motivating philanthropy among householders who provide alms (dana) to sustain sadhus, thereby cultivating a reciprocal ethic of generosity and detachment in broader Hindu culture.[63] Historically, sadhus have acted as custodians of oral traditions, preserving Sanskrit texts through recitation and memorization, as well as folk knowledge embedded in rituals like the dhuni sacred fire, ensuring the continuity of Hindu philosophical and cultural heritage across generations via embodied and verbal transmission.[51] In interfaith contexts, sects such as the Udasis exemplify bridging roles between Hinduism and Sikhism, revering the Guru Granth Sahib alongside Hindu scriptures to foster shared devotional practices and spiritual unity.[64] Furthermore, contemporary sadhus contribute to environmental movements by invoking Hindu reverence for nature—viewing rivers and forests as divine manifestations—to advocate for ecological protection and ethical stewardship.[65] Female sadhus, known as sadhavis, hold significant yet underrepresented roles in guiding women toward spiritual empowerment, often serving as mentors in ashrams where they teach meditation, scriptural interpretation, and ascetic disciplines tailored to female experiences of devotion and renunciation.[66] Through personal example and direct instruction, sadhavis challenge gender norms by leading all-female groups and inspiring female disciples to pursue independent spiritual paths, thereby expanding access to esoteric knowledge traditionally dominated by male ascetics.[67]Participation in Festivals and Gatherings

Sadhus hold a prominent position in major religious festivals and gatherings, where their presence underscores themes of renunciation, spiritual authority, and communal harmony. The Kumbh Mela stands as the preeminent event, recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity and held every 12 years in rotation at four sacred sites—Prayagraj, Haridwar, Nashik, and Ujjain—drawing tens of millions of pilgrims from diverse backgrounds.[68] Organized by akharas (monastic orders), the festival features elaborate temporary camps, or akhadas, that serve as hubs for sadhus from various sects, accommodating hundreds of thousands and facilitating rituals, meditation, and yogic demonstrations.[69] These gatherings culminate in the shahi snan, or royal bathing rituals on auspicious dates, where sadhus lead processions to the confluence of holy rivers, symbolizing purification and the pursuit of moksha (liberation).[70] During the Kumbh Mela, sadhus actively engage in ceremonial roles that enhance the event's spiritual depth. Naga sadhus, known for their ascetic nudity and ash-covered bodies, often spearhead the peshwai processions—grand parades with chariots, elephants, and martial displays—to mark akhara arrivals and assert sectarian traditions.[70] The Akhil Bharatiya Akhara Parishad, a governing council of 13 major akharas, coordinates the sequence of these processions and bathing rites to prevent inter-sect conflicts, historically resolving disputes through deliberations that maintain order among the converging monastic groups.[69][71] Sadhus lead communal chants such as "Har Har Mahadev," distribute prasad (blessed offerings), and offer darshan (auspicious viewing) to devotees, fostering a sense of shared devotion amid the massive influx of participants.[72][73] These logistics, including akhara-managed hospitality and crowd oversight, enable the event to function as a vast temporary city, blending ritual with practical governance.[74] Beyond the Kumbh Mela, sadhus contribute to other festivals, adapting their ascetic roles to specific traditions. In Hindu observances like Maha Shivaratri, akhara sadhus organize shahi processions to Shiva temples, such as Kashi Vishwanath in Varanasi, where they perform rites and lead devotees in night-long vigils honoring Lord Shiva.[75] Jain sadhus participate in Paryushana, an annual festival of atonement lasting eight days for Śvētāmbaras or ten for Digambaras, residing with lay communities to deliver pravachans (discourses) from texts like the Kalpa Sūtra, guide collective meditations, and emphasize forgiveness through rituals like Pratikraman.[76] Such engagements highlight sadhus' function in these events as spiritual exemplars, briefly referencing sect-specific processions without delving into broader sectarian details. The participation of sadhus in these festivals reinforces longstanding monastic traditions, serves as a platform for inter-akharas networking, and draws global pilgrims, thereby sustaining cultural and spiritual continuity in Hinduism and Jainism.[68] By converging in vast assemblies, sadhus not only perpetuate rituals but also embody detachment, inspiring attendees toward ethical living and devotion.[70]Modern Context and Challenges

Contemporary Demographics

Contemporary demographics of sadhus reflect a predominantly Indian population with limited global presence, shaped by ongoing social and economic transformations. Estimates place the total number of sadhus in India at approximately 4 to 5 million, encompassing Hindu and Jain ascetics who have renounced worldly life for spiritual pursuits.[77] Smaller communities exist in Nepal, particularly around sacred sites like Pashupatinath Temple in Kathmandu, where sadhus engage in meditation and rituals, though exact figures remain undocumented in census data.[78] In the diaspora, small numbers of sadhus reside in ashrams in countries such as the UK and US, maintaining traditional practices within Hindu expatriate networks, though exact figures are not well-documented. Demographic shifts indicate gradual changes in composition and location. Female sadhus, known as sadhvis, constitute about 10 to 15 percent of the ascetic population, a rising proportion driven by increased acceptance in certain orders and the formation of women-led akharas.[79] Urbanization has drawn more sadhus to cities, contrasting with traditional rural wandering. Recruitment often draws from rural poor backgrounds, with initiates typically embracing sannyasa after personal crises or spiritual calling, though modern materialism poses challenges to sustaining numbers.[80] Age profiles skew toward middle-aged and older individuals, with around 52 percent between 51 and 60 years and 26 percent aged 41 to 50, reflecting the rigorous lifelong commitment required.[42] Regional hotspots include the Himalayas for hermitic Hindu sadhus seeking isolation, Rajasthan for Jain monks in monastic centers, and South India for Shaiva traditions centered on temple vicinities. These patterns draw from post-2000 scholarly studies and ethnographic reports, as official censuses like India's do not separately enumerate ascetics.[77]Controversies and Adaptations

In recent years, the sadhu tradition has faced significant controversies surrounding impostors who exploit devotees for financial gain or commit crimes, tarnishing the image of genuine ascetics. In 2017, the Akhil Bharatiya Akhara Parishad, a prominent body representing Hindu monastic orders, released a list of 14 "fake babas," including figures like Asaram Bapu and Gurmeet Ram Rahim, accused of serious offenses such as rape, murder, and financial scams often targeting pilgrims at religious sites. These cases, peaking in the 2010s, highlighted how fraudulent individuals posed as sadhus to perpetrate exploitation, particularly during mass gatherings like the Kumbh Mela, where vulnerable devotees were defrauded of donations or coerced into illicit activities.[81] Debates on superstition versus authentic spirituality have intensified scrutiny of sadhu practices, with critics arguing that some rituals perpetuate irrational beliefs while defenders emphasize their philosophical depth. Rationalist movements in India, such as those led by organizations like the Indian Rationalist Association, have challenged sadhu-led practices like faith healing or occult predictions as superstitious, linking them to broader societal harms like delayed medical treatment. Conversely, proponents, drawing from historical figures like Swami Vivekananda, advocate for distinguishing genuine spiritual renunciation from exploitative superstitions, urging reforms to preserve the tradition's core emphasis on self-realization over ritualistic excess.[82][83] Legal challenges have arisen from Indian laws that intersect with sadhu lifestyles, particularly regarding wandering and public conduct. The Bombay Prevention of Begging Act of 1959, extended across several states, criminalizes soliciting alms in public spaces, inadvertently affecting sadhus whose renunciation includes bhiksha (ritual begging) as a means of detachment from material wealth; studies show this has led to arrests of ascetics in urban areas like Mumbai, where religious mendicancy is often indistinguishable from secular begging under the law.[84] Court cases on public nudity, a key practice for Digambara Jain sadhus symbolizing complete renunciation, have tested constitutional rights against obscenity laws. In 2015, a Goa court ordered an FIR against monk Pranam Sagar Maharaj under Section 294 of the Indian Penal Code for roaming naked in Margao, ruling that while it did not outrage religious sentiments, it caused public annoyance, balancing freedom of religion with societal norms.[85] Modern adaptations reflect the sadhu tradition's evolution amid technological and environmental shifts. Post-COVID-19, many gurus and sadhus turned to social media for online discourses, conducting e-satsangs, virtual prayers, and live streams to maintain spiritual guidance during lockdowns, thereby broadening access to teachings for global audiences including marginalized groups.[86] Environmental activism has seen the rise of eco-sadhus who integrate sustainability into asceticism, such as Himalayan sadhus advocating for river rights through legal petitions invoking Hindu cosmology of ecological interconnectedness, exemplified by campaigns to protect the Ganga from pollution and dam projects.[65] Efforts to address gender and caste barriers are fostering greater inclusivity within sadhu orders. Women's participation has grown through initiatives like the 2016 formation of the Pari Akhara, an all-female sadhu group challenging male dominance by allowing women to lead rituals and akharas independently, countering historical exclusions in traditions like the Naga sadhus. Similarly, caste hierarchies are being contested, as seen in the 2025 initiation of over 20% Dalit and tribal members into Naga orders at the Maha Kumbh, marking a historic shift toward dismantling varna-based restrictions in monastic recruitment.[87][88] Global perceptions of sadhus often romanticize them as enigmatic "holy men" in yoga tourism, where Western travelers encounter them as symbols of exotic spirituality during retreats in Rishikesh or at festivals, fostering a commodified view that blends genuine asceticism with performative mysticism. However, critiques highlight patriarchal structures within these traditions, such as gender-segregated akharas and exclusionary practices, which perpetuate inequality and clash with modern egalitarian ideals in international discourse on Indian spirituality.[89]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/sadhu