Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

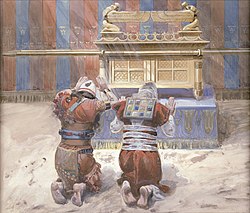

Ark of the Covenant

View on Wikipedia

The Ark of the Covenant,[a] also known as the Ark of the Testimony[b] or the Ark of God,[c][1][2] was a religious storage chest and relic held to be the most sacred object by the Israelites.

Religious tradition describes it as a wooden storage chest decorated in solid gold accompanied by an ornamental lid known as the Seat of Mercy. According to the Book of Exodus[3] and First Book of Kings[4] in the Hebrew Bible and the Old Testament, the Ark contained the Tablets of the Law, by which God delivered the Ten Commandments to Moses at Mount Sinai. According to the Book of Exodus,[5] the Book of Numbers,[6] and the Epistle to the Hebrews[7] in the New Testament, it also contained Aaron's rod and a pot of manna.[8] The biblical account relates that approximately one year after the Israelites' exodus from Egypt, the Ark was created according to the pattern that God gave to Moses when the Israelites were encamped at the foot of Mount Sinai. Thereafter, the gold-plated acacia chest's staves were lifted and carried by the Levites approximately 2,000 cubits (800 meters or 2,600 feet) in advance of the people while they marched.[9] God spoke with Moses "from between the two cherubim" on the Ark's cover.[10]

Jewish tradition holds various views on the Ark’s fate, including that it was taken to Babylon, hidden by King Josiah in the Temple or underground chambers, or concealed by Jeremiah in a cave on Mount Nebo. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church asserts it is housed in Axum; the Lemba people of southern Africa claim ancestral possession with a replica in Zimbabwe; some traditions say it was in Rome or Ireland but lost, though no verified evidence conclusively confirms its location today. It is honored by Samaritans, symbolized in Christianity as a type of Christ and the Virgin Mary, mentioned in the Quran, and viewed with spiritual significance in the Baháʼí Faith. The Ark of the Covenant has been prominently featured in modern films such as Raiders of the Lost Ark and other literary and artistic works, often depicted as a powerful and mysterious relic with both historical and supernatural significance.

There are ongoing academic discussions among biblical scholars and archeologists regarding the history of the Ark's movements around the Ancient Near East as well as the history and dating of the Ark narratives in the Hebrew Bible.[11][12][13] There is additional scholarly debate over possible historical influences that led to the creation of the Ark, including Bedouin or Egyptian influences.[14][15][16]

Biblical account

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Ten Commandments |

|---|

|

| Related articles |

Construction and description

[edit]

According to the Book of Exodus, God instructed Moses to build the Ark during his 40-day stay upon Mount Sinai.[17][18] He was shown the pattern for the tabernacle and furnishings of the Ark, and told that it would be made of shittim wood (also known as acacia wood)[19] to house the Tablets of Stone.[19] Moses instructed Bezalel and Oholiab to construct the Ark.[20][21][22]

The Book of Exodus gives detailed instructions on how the Ark is to be constructed.[23] It is to be 2+1⁄2 cubits in length, 1+1⁄2 cubits breadth, and 1+1⁄2 cubits height (approximately 131×79×79 cm or 52×31×31 in) of acacia wood. Then it is to be gilded entirely with gold, and a crown or molding of gold is to be put around it. Four rings of gold are to be attached to its four corners, two on each side—and through these rings staves of shittim wood overlaid with gold for carrying the Ark are to be inserted; and these are not to be removed.[24]

Mobile vanguard

[edit]The biblical account continues that, after its creation by Moses, the Ark was carried by the Israelites during their 40 years of wandering in the desert. Whenever the Israelites camped, the Ark was placed in the tent of meeting, inside the Tabernacle.

When the Israelites, led by Joshua toward the Promised Land, arrived at the banks of the River Jordan, the Ark was carried in the lead, preceding the people, and was the signal for their advance.[25][26] During the crossing, the river grew dry as soon as the feet of the priests carrying the Ark touched its waters, and remained so until the priests—with the Ark—left the river after the people had passed over.[27][28][29][30] As memorials, twelve stones were taken from the Jordan at the place where the priests had stood.[31]

During the Battle of Jericho, the Ark was carried around the city once a day for six days, preceded by the armed men and seven priests sounding seven trumpets of rams' horns.[32] On the seventh day, the seven priests sounding the seven trumpets of rams' horns before the Ark compassed the city seven times, and, with a great shout, Jericho's wall fell down flat and the people took the city.[33]

After the defeat at Ai, Joshua lamented before the Ark.[34] When Joshua read the Law to the people between Mount Gerizim and Mount Ebal, they stood on each side of the Ark. The Ark was then kept at Shiloh after the Israelites finished their conquest of Canaan.[35] We next hear of the Ark in Bethel,[d] where it was being cared for by the priest Phinehas, the grandson of Aaron.[36] According to this verse, it was consulted by the people of Israel when they were planning to attack the Benjaminites at the Battle of Gibeah. Later the Ark was kept at Shiloh again,[37] where it was cared for by Hophni and Phinehas, two sons of Eli.[38]

Capture by the Philistines

[edit]

According to the biblical narrative, a few years later the elders of Israel decided to take the Ark onto the battlefield to assist them against the Philistines, having recently been defeated at the battle of Eben-Ezer.[39] They were again heavily defeated, with the loss of 30,000 men. The Ark was captured by the Philistines, and Hophni and Phinehas were killed. The news of its capture was at once taken to Shiloh by a messenger "with his clothes rent, and with earth upon his head". The old priest, Eli, fell dead when he heard it, and his daughter-in-law, bearing a son at the time the news of the Ark's capture was received, named him Ichabod—explained as "The glory has departed Israel" in reference to the loss of the Ark.[40] Ichabod's mother died at his birth.[41]

The Philistines took the Ark to several places in their country, and at each place misfortune befell them.[42] At Ashdod it was placed in the temple of Dagon. The next morning Dagon was found prostrate, bowed down, before it; and on being restored to his place, he was on the following morning again found prostrate and broken. The people of Ashdod were smitten with tumors; a plague of rodents was sent over the land. This may have been the bubonic plague.[43][44][45] The affliction of tumours was also visited upon the people of Gath and of Ekron, whither the Ark was successively removed.[46]

Return of the Ark to the Israelites

[edit]

After the Ark had been among them for seven months, the Philistines, on the advice of their diviners, returned it to the Israelites, accompanying its return with an offering consisting of golden images of the tumors and mice wherewith they had been afflicted. The Ark was set up in the field of Joshua of Beit Shemesh, and the people of Beit Shemesh offered sacrifices and burnt offerings according to the first five verses of 1 Samuel 6. Verse 19, 1 Samuel 6 states that out of curiosity, the people of Beit Shemesh gazed at the Ark, and as a punishment, God struck down seventy of them (fifty thousand and seventy in some translations). The men of Beit Shemesh sent to Qiryath Ye'arim to have the Ark removed in verse 21, and it was taken to the house of Abinadab, whose son Eleazar was sanctified to keep it. Qiryath Ye'arim remained the abode of the Ark for twenty years, according to 1 Samuel 7.

Under Saul, the Ark was with the army before he first met the Philistines, but the king was too impatient to consult it before engaging in battle. In 1 Chronicles 13, it is stated that the people were not accustomed to consulting the Ark in the days of Saul.

During the reign of King David

[edit]

In the biblical narrative, at the beginning of his reign over the United Monarchy, King David removed the Ark from Kirjath-jearim amid great rejoicing. On the way to Zion, Uzzah, one of the drivers of the cart that carried the Ark, put out his hand to steady the Ark, and was struck dead by God for touching it. The place was subsequently named "Perez-Uzzah", literally 'outburst against Uzzah',[47] as a result. David, in fear, carried the Ark aside into the house of Obed-edom the Gittite, instead of carrying it on to Zion, and it stayed there for three months.[48][49]

On hearing that God had blessed Obed-edom because of the presence of the Ark in his house, David had the Ark brought to Zion by the Levites, while he himself, "girded with a linen ephod [...] danced before the Lord with all his might" and in the sight of all the public gathered in Jerusalem, a performance which caused him to be scornfully rebuked by his first wife, Saul's daughter Michal.[50][51][52] In Zion, David put the Ark in the tent he had prepared for it, offered sacrifices, distributed food, and blessed the people and his own household.[53][54][55] David used the tent as a personal place of prayer.[56][57]

The Levites were appointed to minister before the Ark.[58] David's plan of building a temple for the Ark was stopped on the advice of the prophet Nathan.[59][60][61][62] The Ark was with the army during the siege of Rabbah;[63] and when David fled from Jerusalem at the time of Absalom's conspiracy, the Ark was carried along with him until he ordered Zadok the priest to return it to Jerusalem.[64]

The Temple of King Solomon

[edit]

According to the Biblical narrative, when Abiathar was dismissed from the priesthood by King Solomon for having taken part in Adonijah's conspiracy against David, his life was spared because he had formerly borne the Ark.[65] Solomon worshipped before the Ark after his dream in which God promised him wisdom.[66]

During the construction of Solomon's Temple, a special inner room, named Kodesh Hakodashim ('Holy of Holies'), was prepared to receive and house the Ark;[67] and when the Temple was dedicated, the Ark—containing the original tablets of the Ten Commandments—was placed therein.[68] When the priests emerged from the holy place after placing the Ark there, the Temple was filled with a cloud, "for the glory of the Lord had filled the house of the Lord".[69][70][71]

When Solomon married Pharaoh's daughter, he caused her to dwell in a house outside Zion, as Zion was consecrated because it contained the Ark.[72] King Josiah also had the Ark returned to the Temple,[73] from which it appears to have been removed by one of his predecessors (cf. 2 Chronicles 33–34 and 2 Kings 21–23).

During the reign of King Hezekiah

[edit]

Prior to king Josiah who is the last biblical figure mentioned as having seen the Ark, king Hezekiah had seen the Ark.[74][75] Hezekiah is also known for protecting Jerusalem against the Assyrian Empire by improving the city walls and diverting the waters of the Gihon Spring through a tunnel known today as Hezekiah's Tunnel, which channeled the water inside the city walls to the Pool of Siloam.[76]

In a noncanonical text known as the Treatise of the Vessels, Hezekiah is identified as one of the kings who had the Ark and the other treasures of Solomon's Temple hidden during a time of crisis. This text lists the following hiding places, which it says were recorded on a bronze tablet: (1) a spring named Kohel or Kahal with pure water in a valley with a stopped-up gate; (2) a spring named Kotel (or "wall" in Hebrew); (3) a spring named Zedekiah; (4) an unidentified cistern; (5) Mount Carmel; and (6) locations in Babylon.[77]

To many scholars, Hezekiah is also credited as having written all or some of the Book of Kohelet (Ecclesiastes in the Christian tradition), in particular the famously enigmatic epilogue.[78] Notably, the epilogue appears to refer to the Ark story with references to almond blossoms (i.e., Aaron's rod), locusts, silver, and gold. The epilogue then cryptically refers to a pitcher broken at a fountain and a wheel broken at a cistern.[79]

Although scholars disagree on whether the Pool of Siloam's pure spring waters were used by pilgrims for ritual purification, many scholars agree that a stepped pilgrimage road between the pool and the Temple had been built in the first century CE.[80] This roadway has been partially excavated, but the west side of the Pool of Siloam remained unexcavated, as of 2016.[81]

The invasion of the Kingdom of Babylon

[edit]In 587 BC, when the Babylonians destroyed Jerusalem, an ancient Greek version of the biblical third Book of Ezra, 1 Esdras, suggests that Babylonians took away the vessels of the ark of God, but does not mention taking away the Ark:

And they took all the holy vessels of the Lord, both great and small, with the vessels of the ark of God, and the king's treasures, and carried them away into Babylon[82]

In Rabbinic literature, the final disposition of the Ark is disputed. Some rabbis hold that it must have been carried off to Babylon, while others hold that it must have been hidden lest it be carried off into Babylon and never brought back.[83] A late 2nd-century rabbinic work known as the Tosefta states the opinions of these rabbis that Josiah, the king of Judah, stored away the Ark, along with the jar of manna, and a jar containing the holy anointing oil, the rod of Aaron which budded and a chest given to Israel by the Philistines.[84]

Service of the Kohathites

[edit]The Kohathites were one of the Levite houses from the Book of Numbers. Theirs was the responsibility to care for "the most holy things" in the tabernacle. When the camp, then wandering the Wilderness, set out the Kohathites would enter the tabernacle with Aaron and cover the ark with the screening curtain and "then they shall put on it a covering of fine leather, and spread over that a cloth all of blue, and shall put its poles in place." The ark was one of the items of the tent of meeting that the Kohathites were responsible for carrying.[85]

Jewish tradition on location today

[edit]The Talmud in Yoma[86] suggests that the Ark was removed from the Temple towards the end of the era of the First Temple and the Second Temple never housed it. According to one view, it was taken to Babylon when Nebuchadnezzar conquered Jerusalem in 587 BCE, exiling King Jeconiah along with the upper classes.[87]

Another perspective proposes that Josiah, king of Judah, hid the Ark in anticipation of the Temple's destruction. Where it was hidden remains uncertain. One account in the Talmud[88][89][90] mentions a priest's suspicion of a tampered stone in a chamber designated for wood storage, hinting at the Ark's concealment.

Alternatively, it has been suggested that the Ark remained underground in the Holy of Holies. Some of the Chazal, including the Radak and Maimonides, propose that Solomon designed tunnels beneath the Temple to safeguard the Ark that Josiah later used. Attempts to excavate this area have yielded little due to political sensitivities.[91][92][93]

An opinion found in the II Maccabees 2:4-10, asserts that Jeremiah hid the Ark and other sacred items in a cave on Mount Nebo (now in Jordan), anticipating the Neo-Babylonian invasion.

Archaeology and historical context

[edit]Archaeological evidence shows strong cultic activity at Kiriath-Jearim in the 8th and 7th centuries BC, well after the ark was supposedly removed from there to Jerusalem.[94] In particular, archaeologists found a large elevated podium, associated with the Northern Kingdom and not the Southern Kingdom, which may have been a shrine.[95] Thomas Römer suggests that this may indicate that the ark was not moved to Jerusalem until much later, possibly during the reign of King Josiah (reigned c. 640–609 BCE). He notes that this might explain why the ark featured prominently in the history before Solomon, but not after. Additionally, 2 Chronicles 35:3[73] indicates that it was moved during King Josiah's reign.[94] However, Yigal Levin argues that there is no evidence that Kiriath-Jearim was a cultic center in the monarchical era or that it ever housed any "temple of the Ark".[12]: 52, 57

K. L. Sparks believes the story of the Ark was written independently around the 8th century BC in a text referred to as the "Ark Narrative" and then incorporated into the main biblical narrative just before the Babylonian exile.[96]

Römer also suggests that the ark may have carried sacred stones "of the kind found in the chests of pre-Islamic Bedouins" and speculates that these may have been either a statue of Yahweh or a pair of statues depicting both Yahweh and his companion goddess Asherah.[14] In contrast, Scott Noegel has argued that the parallels between the ark and these practices remain "unconvincing" in part because the Bedouin objects lack the ark's distinctive structure, function, and mode of transportation.[15] Unlike the ark, the Bedouin chests "contained no box, no lid, and no poles," they did not serve as the throne or footstool of a god, they were not overlaid with gold, did not have kerubim figures upon them, there were no restrictions on who could touch them, and they were transported on horses or camels.[15]

Noegel suggests that the ancient Egyptian Solar barque is a more plausible model for the Israelite ark, since Egyptian barques had all the features just mentioned. He adds that the Egyptians also were known to place written covenants beneath the feet of statues, proving a further parallel to the placement of the covenantal tablets inside the ark.[15]

Levin holds that some biblical texts suggest that the Ark of the Covenant was only one among many other different arks at regional shrines prior to the centralization of worship in Jerusalem,[97] although Raanan Eichler disagrees.[98] While Clifford Mark McCormick has questioned whether the Ark ever existed,[99] other scholars such as Eichler, David A. Falk, Roger D. Isaacs, and Adam R. Hemmings have defended its historicity and antiquity based on linguistic evidence and significant parallels with similar artifacts from New Kingdom Egypt.[100][101][16]

References in Abrahamic religions

[edit]Tanakh

[edit]

The Ark is first mentioned in the Book of Exodus and then numerous times in Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, I Samuel, II Samuel, I Kings, I Chronicles, II Chronicles, Psalms, and Jeremiah.

In the Book of Jeremiah, it is referenced by Jeremiah, who, speaking in the days of Josiah,[102] prophesied a future time, possibly the end of days, when the Ark will no longer be talked about or be made use of again:

And it shall be that when you multiply and become fruitful in the land, in those days—the word of the LORD—they will no longer say, 'The Ark of the Covenant of the LORD' and it will not come to mind; they will not mention it, and will not recall it, and it will not be used any more.

Rashi comments on this verse that "The entire people will be so imbued with the spirit of sanctity that God's Presence will rest upon them collectively, as if the congregation itself was the Ark of the Covenant."[103]

Second Book of Maccabees

[edit]According to Second Maccabees, at the beginning of chapter 2:[104]

The records show that it was the prophet Jeremiah who [...] prompted by a divine message [...] gave orders that the Tent of Meeting and the ark should go with him. Then he went away to the mountain from the top of which Moses saw God's promised land. When he reached the mountain, Jeremiah found a cave-dwelling; he carried the tent, the ark, and the incense-altar into it, then blocked up the entrance. Some of his companions came to mark out the way, but were unable to find it. When Jeremiah learnt of this he reprimanded them. "The place shall remain unknown", he said, "until God finally gathers his people together and shows mercy to them. The Lord will bring these things to light again, and the glory of the Lord will appear with the cloud, as it was seen both in the time of Moses and when Solomon prayed that the shrine might be worthily consecrated."

The "mountain from the top of which Moses saw God's promised land" would be Mount Nebo, located in what is now Jordan.

Samaritan tradition

[edit]Samaritan tradition claims that the Ark of the Covenant had been kept at a sanctuary on Mt. Gerizim.[105]

New Testament

[edit]The physical ark of the Old Testament

[edit]

In the New Testament, the Ark is mentioned in the Letter to the Hebrews and the Revelation to St. John. Hebrews 9:4 states that the Ark contained "the golden pot that had manna, and Aaron's rod that budded, and the tablets of the covenant."[106] Revelation 11:19 says the prophet saw God's temple in heaven opened, "and the ark of his covenant was seen within his temple."

The Blessed Virgin Mary as the “New Ark”

[edit]In the Gospel of Luke, the author's accounts of the Annunciation and Visitation are constructed using eight points of literary parallelism to compare Mary to the Ark.[107][108]

The contents of the ark were seen by Church Fathers including Thomas Aquinas as symbolic of the attributes of Jesus Christ: the manna as the Holy Eucharist; Aaron's rod as Jesus' eternal priestly authority; and the tablets of the Law, as the Lawgiver himself.[109][110] Thomas Aquinas compared the two types of materials of the ark to the two natures of Christ in the hypostatic union (Jesus having human and divine natures). He wrote, "The Ark, wherein were the Law and the manna, signified Christ, who is 'the living bread that came down from Heaven' and 'the fulfillment of the Law'. Moreover, the wood overlaid with gold signifies that Christ was true man and true God."[111]

Catholic scholars connect the pregnant, birthing Woman of the Apocalypse from Revelation 12:1-2, with the Blessed Virgin Mary, whom they identify as the "Ark of the New Covenant."[107][112] Carrying the saviour of mankind within her, she herself became the Holy of Holies. This is the interpretation given in the third century by Gregory Thaumaturgus, and in the fourth century by Saint Ambrose, Saint Ephraem of Syria and Saint Augustine.[113] The Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches that Mary is a metaphorical version of the ark: "Mary, in whom the Lord himself has just made his dwelling, is the daughter of Zion in person, the ark of the covenant, the place where the glory of the Lord dwells. She is 'the dwelling of God [...] with men."[114]

Saint Athanasius, the bishop of Alexandria, is credited with writing about the connections between the Ark and the Virgin Mary: "O noble Virgin, truly you are greater than any other greatness. For who is your equal in greatness, O dwelling place of God the Word? To whom among all creatures shall I compare you, O Virgin? You are greater than them all O (Ark of the) Covenant, clothed with purity instead of gold! You are the Ark in which is found the golden vessel containing the true manna, that is, the flesh in which Divinity resides" (Homily of the Papyrus of Turin).[107]

Quran

[edit]The Ark is referred to in the Quran (Surah Al-Baqara: 248):[115]

Their prophet further told them, “The sign of Saul’s kingship is that the Ark will come to you—containing reassurance from your Lord and relics of the family of Moses and the family of Aaron, which will be carried by the angels. Surely in this is a sign for you, if you ˹truly˺ believe."

The Ark in other faiths

[edit]According to Uri Rubin, the Ark of the Covenant has a religious basis in Islam (and the Baháʼí Faith), which gives it special significance.[116]

Claims of current status

[edit]According to the Book of Maccabees

[edit]The Book of 2 Maccabees 2:4–10, written around 100 B.C. claims that the prophet Jeremiah, following “being warned by God" before the Babylonian invasion, took the Ark, the Tabernacle, and the Altar of Incense, and buried them in a cave, informing those of his followers who wished to find the place that it should remain unknown "until the time that God should gather His people again together, and receive them unto mercy."[117]

Ethiopia

[edit]

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church claims to possess the Ark of the Covenant in Axum. The Ark is kept under guard in a treasury near the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion. Replicas of the tablets within the Ark, or tabots, are kept in every Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. Each tabot is kept in its own holy of holies, each with its own dedication to a particular saint; the most popular of these include Saint Mary, Saint George and Saint Michael.[118][119]

The Kebra Nagast is often said to have been composed to legitimise the Solomonic dynasty, which ruled the Ethiopian Empire following its establishment in 1270, but this is not the case. It was originally composed in some other language (Coptic or Greek), then translated into Arabic, and translated into Geʽez in 1321.[120] It narrates how the Ark of the Covenant was brought to Ethiopia by Menelik I with divine assistance, while a forgery was left in the Temple in Jerusalem. Although the Kebra Nagast is the best-known account of this belief, the belief predates the document. Abu al-Makarim, writing in the last quarter of the twelfth century, makes one early reference to this belief that they possessed the Ark. "The Abyssinians possess also the Ark of the Covenant", he wrote, and, after a description of the object, describes how the liturgy is celebrated upon the Ark four times a year, "on the feast of the great nativity, on the feast of the glorious Baptism, on the feast of the holy Resurrection, and on the feast of the illuminating Cross."[121]

In his controversial 1992 book The Sign and the Seal, British writer Graham Hancock reports on the Ethiopian belief that the ark spent several years in Egypt before it came to Ethiopia via the Nile River, where it was kept on the islands of Lake Tana for about four hundred years and finally taken to Axum.[122] Archaeologist John Holladay of the University of Toronto called Hancock's theory "garbage and hogwash"; Edward Ullendorff, a former professor of Ethiopian Studies at the University of London, said he "wasted a lot of time reading it." In a 1992 interview, Ullendorff says that he examined the ark held in the church in Axum in 1941. Describing the ark there, he says, "They have a wooden box, but it's empty. Middle- to late-medieval construction, when these were fabricated ad hoc."[123][124]

On 25 June 2009, the patriarch of the Orthodox Church of Ethiopia, Abune Paulos, said he would announce to the world the next day the unveiling of the Ark of the Covenant, which he said had been kept safe and secure in a church in Axum.[125] The following day, he announced that he would not unveil the Ark after all, but that instead he could attest to its current status.[126]

Southern Africa

[edit]The Lemba people of South Africa and Zimbabwe have claimed that their ancestors carried the Ark south, calling it the ngoma lungundu "voice of God", eventually hiding it in a deep cave in the Dumghe mountains, their spiritual home.[127][128]

On 14 April 2008, in a UK Channel 4 documentary, Tudor Parfitt, taking a literalist approach to the Biblical story, described his research into this claim. He says that the object described by the Lemba has attributes similar to the Ark. It was of similar size, was carried on poles by priests, was not allowed to touch the ground, was revered as a voice of their God, and was used as a weapon of great power, sweeping enemies aside.[129]

In his book The Lost Ark of the Covenant (2008), Parfitt also suggests that the Ark was taken to Arabia following the events depicted in the Second Book of Maccabees, and cites Arabic sources which maintain it was brought in distant times to Yemen. Genetic Y-DNA analyses in the 2000s have established a partially Middle-Eastern origin for a portion of the male Lemba population but no specific Jewish connection.[130] Lemba tradition maintains that the Ark spent some time in a place called Sena, which might be Sena, Yemen. Later, it was taken across the sea to East Africa and may have been taken inland at the time of Great Zimbabwe. According to their oral traditions, it self-destructed sometime after the Lemba's arrival with the Ark. Using a core from the original, the Lemba priests constructed a new one. This replica was discovered in a cave by a Swedish-German missionary named Harald Philip Hans von Sicard in the 1940s and eventually found its way to the Museum of Human Sciences in Harare.[128]

Europe

[edit]Rome

[edit]The 2nd century Rabbi Eliezer ben Jose claimed that he saw somewhere in Rome the mercy-seat lid of the ark. According to his account, a bloodstain was present and was told that it was a stain from the blood which the Jewish high priest sprinkled thereon on the Day of Atonement."[131][132]

Accordingly, another tale claims that the Ark was kept within the Basilica of Saint John Lateran, surviving the pillages of Rome by King of the Visigoths Alaric I and King of the Vandals Gaiseric but was eventually lost when the basilica burned in the fifth century.[133][134]

Ireland

[edit]Between 1899 and 1902, the British-Israel Association of London carried out limited excavations of the Hill of Tara in Ireland looking for the Ark of the Covenant. Irish nationalists, including Maud Gonne and the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland (RSAI), campaigned successfully to have them stopped before they destroyed the hill.[135][136][137] A non-invasive survey by archaeologist Conor Newman carried out from 1992 until 1995 found no evidence of the Ark.[137]

The British Israelites believed that the Ark was located at the grave of the Egyptian princess Tea Tephi, who according to Irish legend came to Ireland in the 6th century BC and married Irish King Érimón. Because of the historical importance of Tara, Irish nationalists like Douglas Hyde and W. B. Yeats voiced their protests in newspapers, and in 1902 Maud Gonne led a campaign against the excavations at the site.[138]

Malaita Island

[edit]Many Malaitans claim that the ark of covenant is buried somewhere deep in the jungle of their island. They have a family tradition that they are a lost Jewish tribe from Zedekiah the high priest of Israel. And that he came there in the year 66 AD to bury it. This idea has been recently presented in the article “Ark of Covenant Location Discovered!” by Mike Edery. In the article, he argues that a Torah code from the Baal Shem Tov reveals its current location on Malaita island.[139]

Additionally in the year 2013, a journalist by the name of Mathew Fishbane had visited the island in the hopes of finding the ark on Malaita island. He interviewed several Malaitans who gave the story of how the ark ended up there. Although he was unable to find it, the legend still lives on today.[140]

In literature and the arts

[edit]Philip Kaufman conceived of the Ark of the Covenant as the main plot device of Steven Spielberg's 1981 adventure film Raiders of the Lost Ark,[141][142] where it is found by Indiana Jones in the Egyptian city of Tanis in 1936.[143][e]

In the Danish family film The Lost Treasure of the Knights Templar from 2006, the main part of the treasure found in the end is the Ark of the Covenant. The power of the Ark comes from static electricity stored in separated metal plates like a giant Leyden jar.[144]

In Harry Turtledove's novel Alpha and Omega (2019) the ark is found by archeologists, and the characters have to deal with the proven existence of God.[145]

The Ark has been depicted many times in art for two thousand years, some examples are in the article above, a few more are here.

-

The legendary Emperor Menelik I of Ethiopia (traditionally fl. tenth century BCE) carries the Ark (shown here as small) into Axum.

-

Joshua passing the River Jordan with the Ark of the Covenant. 1800, oil on wood, Benjamin West. Held at Art Gallery of New South Wales.

-

The Philistines Place the Ark of the Covenant in a Temple of their god Dagon. c. 1450, Battista Franco Veneziano. Held at Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

-

Ark of the Covenant. Painted between 1865 and 1880, Erastus Salisbury Field. Held at the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

-

1417 A.D. The Levites, led by King David, carry the Ark of God to Zion, from the Olomouc Bible, Part I, folio 279v, held at the Scientific Library, Olomouc, Czech Republic.

Yom HaAliyah

[edit]Yom HaAliyah (Aliyah Day) (Hebrew: יום העלייה) is an Israeli national holiday celebrated annually on the tenth of the Hebrew month of Nisan to commemorate the Israelites crossing the Jordan River into the Land of Israel while carrying the Ark of the Covenant.[146][147]

See also

[edit]- Ngoma Lungundu

- Copper Scroll

- List of artifacts in biblical archaeology

- The Exodus Decoded (2006 television documentary)

- History of ancient Israel and Judah

- Jewish symbolism

- Mikoshi, a portable Shinto shrine

- Gihon Spring

- Josephus

- Mount Gerizim

- Temple menorah

- Pool of Siloam

- Samaritans

- Siloam Tunnel

- Solomon's Temple

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Biblical Hebrew: אֲרוֹן הַבְּרִית, romanized: ʾĂrōn haBǝrīṯ; Koine Greek: Κιβωτὸς τῆς Διαθήκης, romanized: Kībōtòs tês Diathḗkēs; Ge'ez: ታቦት, romanized: tābōt; Standard Arabic: التابوت, romanized: Al-Tābūt;

- ^ אֲרוֹן הָעֵדוּת, ʾĂrōn hāʿĒdūṯ

- ^ אֲרוֹן־יְהוָה, ʾĂrōn-YHWH or אֲרוֹן הָאֱלֹהִים, ʾĂrōn hāʾĔlōhīm

- ^ 'Bethel' is translated as 'the House of God' in the King James Version.

- ^ The Ark is mentioned in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) and briefly appears in Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008).

References

[edit]- ^ "Bible Gateway passage: 1 Chronicles 16–18 – New Living Translation". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- ^ "Bible Gateway passage: 1 Samuel 3:3 – New International Version". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- ^ Exodus 40:20.

- ^ 1 Kings 8:9.

- ^ Exodus 16:33.

- ^ Numbers 17:6–11.

- ^ Hebrews 9:4.

- ^ Ackerman, Susan (2000). "Ark of the Covenant". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. p. 102. ISBN 978-90-5356-503-2.

- ^ Joshua 3:4.

- ^ Exodus 25:22.

- ^ McGeough, Kevin M. (2025). Readers of the Lost Ark: Imagining the Ark of the Covenant from Ancient Times to the Present. Oxford University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-19-765388-3.

- ^ a b Levin, Yigal (2021). "Was Kiriath-jearim in Judah or in Benjamin?". Israel Exploration Journal. 71 (1): 43–63. ISSN 0021-2059. JSTOR 27100296.

- ^ Römer, Thomas (2023). "The mysteries of the Ark of the Covenant". Studia Theologica - Nordic Journal of Theology. 77 (2): 169–185. doi:10.1080/0039338X.2023.2167861.

- ^ a b Thomas Römer, The Invention of God (Harvard University Press, 2015), p. 92.

- ^ a b c d Scott Noegel, "The Egyptian Origin of the Ark of the Covenant" in Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider, and William H. C. Propp (eds.), Israel's Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective (Springer, 2015), pp. 223–242.

- ^ a b Isaacs, Roger D.; Hemmings, Adam R. (2023-11-08). "The "Mercy Seat" and the Ark of the Testimony: An Age-Old Misnomer?". Studies of Biblical Interest. 1 (1): 11–20. doi:10.5281/zenodo.8311390. ISSN 2993-6217.

- ^ Exodus 19:20.

- ^ Exodus 24:18.

- ^ a b Exodus 25:10.

- ^ Exodus 31.

- ^ Sigurd Grindheim, Introducing Biblical Theology, Bloomsbury Publishing, United Kingdom, 2013, p. 59.

- ^ Joseph Ponessa, Laurie Watson Manhardt, Moses and The Torah: Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, pp. 85–86 (Emmaus Road Publishing, 2007). ISBN 978-1-931018-45-6.

- ^ Exodus 25.

- ^ ""Four feet"; see Exodus 25:12, majority of translations. "Four corners" in King James Version". Biblestudytools.com. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ Joshua 3:3.

- ^ Joshua 6.

- ^ Joshua 3:15–17.

- ^ Joshua 4:10.

- ^ Joshua 11.

- ^ Joshua 18.

- ^ Joshua 4:1–9.

- ^ Joshua 6:4–15.

- ^ Joshua 6:16–20.

- ^ Josh 7:6–9.

- ^ "oremus Bible Browser : Joshua 7:6–9". bible.oremus.org.

- ^ Judges 20:26f.

- ^ 1 Samuel 3:3.

- ^ 1 Samuel 4:3f.

- ^ 1 Samuel 4:3–11.

- ^ 1 Samuel 4:12–22.

- ^ 1 Samuel 4:20.

- ^ 1 Samuel 5:1–6.

- ^ Asensi, Victor; Fierer, Joshua (January 2018). "Of Rats and Men: Poussin's Plague at Ashdod". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 24 (1): 186–187. doi:10.3201/eid2401.AC2401. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 5749463.

- ^ Freemon, Frank R. (September 2005). "Bubonic plague in the Book of Samuel". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 98 (9): 436. doi:10.1177/014107680509800923. ISSN 0141-0768. PMC 1199652. PMID 16140864.

- ^ 1 Samuel 6:5.

- ^ 1 Samuel 5:8–12.

- ^ 2 Samuel 6:8.

- ^ 2 Samuel 6:1–11.

- ^ 1 Chronicles 13:1–13.

- ^ 2 Samuel 6:12–16.

- ^ 2 Samuel 6:20–22.

- ^ 1 Chronicles 15.

- ^ 2 Samuel 6:17–20.

- ^ 1 Chronicles 16:1–3.

- ^ 2 Chronicles 1:4.

- ^ 1 Chronicles 17:16.

- ^ Barnes, W. E. (1899), Cambridge Bible for Schools on 1 Chronicles 17, accessed 22 February 2020.

- ^ 1 Chronicles 16:4.

- ^ 2 Samuel 7:1–17.

- ^ 1 Chronicles 17:1–15.

- ^ 1 Chronicles 28:2.

- ^ 1 Chronicles 3.

- ^ 2 Samuel 11:11.

- ^ 2 Samuel 15:24–29.

- ^ 1 Kings 2:26.

- ^ 1 Kings 3:15.

- ^ 1 Kings 6:19.

- ^ 1 Kings 8:6–9.

- ^ 1 Kings 8:10·11.

- ^ 2 Chronicles 5:13.

- ^ 2 Chronicles 14.

- ^ 2 Chronicles 8:11.

- ^ a b 2 Chronicles 35:3.

- ^ Isaiah 37:14–17.

- ^ 2 Kings 19:14–19.

- ^ 2 Chronicles 32:3–5.

- ^ Davila, J., The Treatise of the Vessels (Massekhet Kelim): A New Translation and Introduction, p. 626 (2013).

- ^ Quackenbos, D., Recovering an Ancient Tradition: Toward an Understanding of Hezekiah as the Author of Ecclesiastes, pp. 238–253 (2019).

- ^ Ecclesiastes 12:5–6.

- ^ Tercatin, R. (2021-05-05). "Second Temple period 'lucky lamp' found on Jerusalem's Pilgrimage Road". The Jerusalem Post. ISSN 0792-822X. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ^ Szanton, N.; Uziel, J. (2016), "Jerusalem, City of David [stepped street dig, July 2013 – end 2014], Preliminary Report (21/08/2016)". Hadashot Arkheologiyot. Israel Antiquities Authority, http://www.hadashot-esi.org.il/report_detail_eng.aspx?id=25046&mag_id=124.

- ^ 1 Esdras 1:54

- ^ "Ark of the Covenant". Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ Tosefta (Sotah 13:1); cf. Babylonian Talmud (Kereithot 5b).

- ^ Numbers 4:5.

- ^ Yoma 52b, 53b-54a.

- ^ Isaiah 39:6.

- ^ "Yoma 54a:7". www.sefaria.org.

- ^ Yoma 54a, 157/271, text accompanying notes 13-15 (PDF).

- ^ Citing Mishnah Shekalim 6.2

- ^ "II Chronicles 35:3". www.sefaria.org.

- ^ Citing Yoma 52b.11

- ^ "Beit Habechirah - Chapter 4 - Chabad.org".

- ^ a b David, Ariel (30 Aug 2017). "The Real Ark of the Covenant may have Housed Pagan Gods". Haaretz.

- ^ Borschel-Dan, Amanda (10 January 2019). "Biblical site tied to Ark of the Covenant unearthed at convent in central Israel". Times of Israel. Retrieved 21 March 2025.

- ^ K. L. Sparks, "Ark of the Covenant" in Bill T. Arnold and H. G. M. Williamson (eds.), Dictionary of the Old Testament: Historical Books (InterVarsity Press, 2005), p. 91.

- ^ Yigal Levin, “One Ark, Two Arks, Three Arks, More? The Many Arks of Ancient Israel,” in Epigraphy, Iconography and the Bible, ed., Meir and Edith Lubetski (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2021).

- ^ Eichler, Raanan (2021). The Ark and the Cherubim. Mohr Siebeck. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-3-16-155432-2.

- ^ Clifford Mark McCormick. Palace and Temple: A Study of Architectural and Verbal Icons (Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft, 313). pp. 169-190. De Gruyter. 2002.

- ^ Falk, David A. (2020). The Ark of the Covenant in Its Egyptian Context: An Illustrated Journey. Hendrickson Publishers. ISBN 978-1-68307-267-6.

- ^ Eichler, Raanan (2021). The Ark and the Cherubim. Forschungen zum Alten Testament. Vol. 146. Mohr Siebeck. pp. 302–304. ISBN 978-3-16-155432-2.

- ^ Jeremiah 3:16.

- ^ Jeremiah 3:16, Tanach. Brooklyn, New York: ArtScroll. p. 1078.

- ^ 2 Maccabees 2:4–8.

- ^ Matassa, Lidia Domenica (2007). "Samaritans History". In Skolnik, Fred; Michael Berenbaum (eds.). ENCYCLOPAEDIA JUDAICA. Vol. 17 Ra–Sam (2nd ed.). Thomson Gale. p. 719. ISBN 978-0-02-865945-9.

- ^ Hebrews 9:4.

- ^ a b c Ray, Steve (October 2005). "Mary, the Ark of the New Covenant". This Rock. 16 (8). Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ "Holy Queen, Lesson 3.1".

- ^ "Ark of the Covenant". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2020-04-18 – via New Advent.

- ^ Feingold, Lawrence (2018-04-01). "2". The Eucharist: Mystery of Presence, Sacrifice, and Communion. Emmaus Academic. ISBN 978-1-945125-74-4.

- ^ Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica Part: III (Tertia Pars), Question 25, Article 3

- ^ David Michael Lindsey, The Woman and The Dragon: Apparitions of Mary, p. 21 (Pelican Publishing Company, Incorporated, 2000). ISBN 1-56554-731-4.

- ^ Dwight Longenecker, David Gustafson, Mary: A Catholic Evangelical Debate, p. 32 (Gracewing, 2003). ISBN 0-85244-582-2.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 2676.

- ^ "Surah Al-Baqarah – 248". Quran.com. Retrieved 2023-07-05.

- ^ Rubin, Uri (2001). "Traditions in Transformation: The Ark of the Covenant and the Golden Calf in Biblical and Islamic Historiography" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- ^ Cf. Deuteronomy 34:1–3 and 2 Maccabees 2:4–8.

- ^ Stuart Munro-Hay, 2005, The Quest for the Ark of the Covenant, Tauris (reviewed in Times Literary Supplement 19 August 2005 p. 36).

- ^ Raffaele, Paul. "Keepers of the lost Ark?". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ Bezold, Carl. 1905. Kebra Nagast, die Kerrlichkeit der Könige: Nach den Handschriften in Berlin, London, Oxford und Paris. München: K.B. Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- ^ B. T. A. Evetts (translator), The Churches and Monasteries of Egypt and Some Neighboring Countries attributed to Abu Salih, the Armenian, with added notes by Alfred J. Butler (Oxford, 1895), p. 287f.

- ^ Hancock, Graham (1992). The Sign and the Seal: The Quest for the Lost Ark of the Covenant. New York: Crown. ISBN 0-517-57813-1.

- ^ Hiltzik, Michael (9 June 1992). "Documentary : Does Trail to Ark of Covenant End Behind Aksum Curtain?: A British author believes the long-lost religious object may actually be inside a stone chapel in Ethiopia". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ Jarus, Owen (7 December 2018). "Sorry Indiana Jones, the Ark of the Covenant Is Not Inside This Ethiopian Church". Live Science. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ Fendel, Hillel (2009-06-25). "Holy Ark Announcement Due on Friday", Aruta Sheva (Israel International News). Retrieved on 2009-06-25

- ^ Richard (2009-07-01). "Ho visto l'Arca dell'Alleanza ed è in buone condizioni". Altrogiornale.org (in Italian). Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ^ Parfitt, Tudor (2008). The Lost Ark of the Covenant. HarperCollins.

- ^ a b Van Biema, David (2008-02-25). "A Lead on the Ark of the Covenant – TIME". Archived from the original on 2008-02-25. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ^ "Debates & Controversies – Quest for the Lost Ark". Channel4.com. 2008-04-14. Archived from the original on May 13, 2008. Retrieved 2010-03-07.

- ^ Spurdle, A. B.; Jenkins, T. (November 1996), "The origins of the Lemba "Black Jews" of southern Africa: evidence from p12F2 and other Y-chromosome markers.", Am. J. Hum. Genet., 59 (5): 1126–33, PMC 1914832, PMID 8900243.

- ^ Midrash Tanḥuma. p. 33. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ Midrash Tanchuma, Vayakhel 10:2.

- ^ Salmon, J. (1798). A Description of the Works of Art of Ancient and Modern Rome: Particularly in Architecture, Sculpture & Painting. To which is Added, a Tour Through the Cities and Towns in the Environs of that Metropolis. Vol. 1. London, England: J. Sammells. p. 108.

- ^ Debra J. Birch, Pilgrimage To Rome In The Middle Ages: Continuity and Change, p. 111 (The Boydell Press, 1998). ISBN 0-85115-771-8.

- ^ McAvinchey, Ivan. "News 2006 (March 9)". Rsai.ie. Archived from the original on 2009-03-08. Retrieved 2010-03-07.

- ^ Tara and the Ark of the Covenant. Royal Irish Academy. 7 October 2015.

- ^ a b "Demolishing the myths at Tara". The Irish Times. 1998.

- ^ Carew (Dr.), Mairead. "British Jewish leaders searched for the Ark of the Covenant at Tara". Irish Central.

- ^ Edery, Mike. "Ark of Covenant Location Discovered!". Torahtable.

- ^ Fishbane, Mathew (2013). "Solomon's Island". Tablet Magazine. Retrieved 15 September 2025.

- ^ Graham, Lynn; Graham, David (2003). I Am.. The Power and the Presence. Kindred Productions. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-921788-91-1.

- ^ Insdorf, Annette (15 March 2012). Philip Kaufman. University of Illinois Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-252-09397-5.

- ^ McLoughlin, Tom (2014). A Strange Idea of Entertainment – Conversations with Tom McLoughlin. BearManor Media. p. 66.

- ^ "Tempelriddernes skat". Filmcentralen / streaming af danske kortfilm og dokumentarfilm (in Danish). Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ "Alpha and Omega". Publishers Weekly. July 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ Atali, Amichai (19 June 2016). "Government to pass new holiday: 'Aliyah Day'". Ynetnews. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ^ Yashar, Ari (24 March 2014). "Knesset Proposes Aliyah Holiday Bill". Israel National News. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- Carew, Mairead, Tara and the Ark of the Covenant: A Search for the Ark of the Covenant by British Israelites on the Hill of Tara, 1899–1902. Royal Irish Academy, 2003. ISBN 0-9543855-2-7

- Cline, Eric H. (2007), From Eden to Exile: Unravelling Mysteries of the Bible, National Geographic Society, ISBN 978-1-4262-0084-7

- Falk, David A. (2020), The Ark of the Covenant in Its Egyptian Context: An Illustrated Journey, Hendrickson Publishers, ISBN 978-1-68307-267-6

- Foster, Charles, Tracking the Ark of the Covenant. Monarch, 2007.

- Grierson, Roderick & Munro-Hay, Stuart, The Ark of the Covenant. Orion Books Ltd, 2000. ISBN 0-7538-1010-7

- Hancock, Graham, The Sign and the Seal: The Quest for the Lost Ark of the Covenant. Touchstone Books, 1993. ISBN 0-671-86541-2

- Haran, M., The Disappearance of the Ark, IEJ 13 (1963), pp. 46–58

- Hertz, J. H., The Pentateuch and Haftoras. Deuteronomy. Oxford University Press, 1936.

- Hubbard, David (1956) The Literary Sources of the Kebra Nagast Ph.D. dissertation, St. Andrews University, Scotland

- Munro-Hay, Stuart, The Quest For The Ark of The Covenant: The True History of The Tablets of Moses. L. B. Tauris & Co Ltd., 2006. ISBN 1-84511-248-2

- Ritmeyer, L., The Ark of the Covenant: Where It Stood in Solomon's Temple. Biblical Archaeology Review 22/1: 46–55, 70–73, 1996

- Stolz, Fritz. "Ark of the Covenant." In The Encyclopedia of Christianity, edited by Erwin Fahlbusch and Geoffrey William Bromiley, 125. Vol. 1. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1999. ISBN 0-8028-2413-7

External links

[edit]- Portions of this article have been taken from the Jewish Encyclopedia of 1906. Ark of the Covenant

- The Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume I. Ark of the Covenant

- Smith, William Robertson (1878). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. II (9th ed.). p. 539.

- Smithsonian.com "Keepers of the Lost Ark?"'

- Shyovitz, David, The Lost Ark of the Covenant, Jewish Virtual Library

Ark of the Covenant

View on GrokipediaBiblical Description

Construction Instructions and Materials

The Lord provided Moses with detailed instructions for constructing the Ark while on Mount Sinai, specifying that it serve as a chest to hold the tablets of the covenant law.[9] The Ark was to be crafted from acacia wood, measuring two and a half cubits in length, one and a half cubits in width, and one and a half cubits in height, then overlaid inside and outside with pure gold to form a unified structure.[10] Four gold rings were to be cast and attached to its four feet—two on one side and two on the other—for inserting carrying poles made of acacia wood and overlaid with gold; these poles were expressly forbidden from being removed from the rings.[11] A separate cover, termed the mercy seat and measuring two and a half cubits long by one and a half cubits wide, was to be fashioned from pure gold and placed atop the Ark.[12] At each end of this mercy seat, two cherubim were to be formed from a single piece of hammered gold, with their wings extended upward to overshadow the mercy seat; the cherubim's faces were to look toward one another and downward at the mercy seat itself.[13] The instructions emphasized precise adherence, stating that God would meet with Moses there above the mercy seat, between the cherubim, to communicate commands for the Israelites.[14] To ensure skilled execution, the Lord designated Bezalel, son of Uri and grandson of Hur from the tribe of Judah, as the chief artisan, endowing him with the Spirit of God in wisdom, understanding, knowledge, and all types of craftsmanship for working with gold, silver, bronze, cutting stones for setting, and carving wood.[15] Bezalel was assisted by Oholiab, son of Ahisamach from the tribe of Dan, similarly gifted in artistic design and teaching, along with other capable workers whose hearts the Lord had stirred.[16] [17] These directives prioritized materials native to the region, such as durable acacia wood known for its resistance to decay, and pure gold for overlay and components, requiring contributions from the Israelite community.[18]Physical Dimensions and Features

The Ark of the Covenant is described in the Hebrew Bible as measuring two and a half cubits in length, one and a half cubits in width, and one and a half cubits in height.[19] [20] Using the common ancient Near Eastern cubit of approximately 18 inches (457 mm), these dimensions equate to roughly 45 inches long, 27 inches wide, and 27 inches high.[21] [19] Structurally, the Ark featured gold rings affixed to its four corners, through which passed carrying poles made of acacia wood overlaid with gold; these poles were explicitly commanded to remain permanently inserted and not removed.[20] [22] The upper surface consisted of a solid gold lid, termed the kapporet in Hebrew, measuring two and a half cubits by one and a half cubits, with two cherubim figures of hammered gold positioned at its ends facing each other.[20] [23]Contents and Theological Symbolism

The Ark of the Covenant housed three primary items according to the New Testament description in Hebrews 9:4: a golden pot containing manna, Aaron's rod that had budded, and the two stone tablets inscribed with the Ten Commandments.[24] The stone tablets, cut from Mount Sinai and written by the finger of God, represented the foundational covenant law given to Moses (Exodus 31:18; 32:15-16).[25] The pot of manna served as a perpetual memorial to God's miraculous provision of bread from heaven during the wilderness wanderings, with instructions to store an omer of it as testimony for future generations (Exodus 16:32-34).[26] Aaron's rod, which miraculously budded, blossomed, and produced almonds overnight to affirm his priestly authority amid rebellion, symbolized divine selection and the rejection of unauthorized leadership (Numbers 17:1-11).[27] These contents collectively embodied tangible evidence of God's covenantal acts: legislative authority through the tablets, providential sustenance via the manna, and hierarchical order in the priesthood through the rod.[28] Unlike mere relics, they functioned causally in Israelite religious practice by anchoring communal memory to specific historical interventions, reinforcing obedience to the law as the condition for divine favor and presence. Theologically, the items underscored a relational dynamic where God's past faithfulness demanded ongoing fidelity, with the Ark's interior serving as a sacred archive of these proofs. Theologically, the Ark itself symbolized the footstool of God's throne, with its mercy seat (kapporet) functioning as the divine pedestal upon which Yahweh's presence rested, as articulated in 1 Chronicles 28:2 where David refers to it explicitly as "the footstool of our God."[29] This imagery drew from ancient Near Eastern royal motifs, where a king's footstool signified dominion over subdued realms, here extending to Yahweh's sovereignty over Israel as His covenant people (Psalm 99:5; 132:7). The cherubim atop the mercy seat flanked the throne-like space, evoking Ezekiel's visions of divine mobility and judgment (Ezekiel 1:4-28; 10:1-22), while the contents beneath reinforced the Ark's role as the earthly locus of revelation and atonement, where God communed with Moses "from above the mercy seat" (Exodus 25:22).[30] In Israelite identity formation, the Ark's contents and structure causally linked national cohesion to empirical reminders of Sinai's miracles, fostering a theocratic worldview where divine law, provision, and authority were not abstract but materially attested—thus countering polytheistic alternatives by privileging monotheistic covenantalism rooted in verifiable historical claims. Later biblical accounts note that by Solomon's temple dedication, only the tablets remained inside (1 Kings 8:9; 2 Chronicles 5:10), suggesting possible removal of the manna and rod for preservation or symbolic obsolescence under settled worship, though Hebrews retroactively affirms their original inclusion as typological of eternal realities.[31][32]Biblical Narrative History

Role in the Exodus and Wanderings

According to traditional biblical chronology derived from 1 Kings 6:1, which states that Solomon's temple construction began 480 years after the Exodus, the event is dated to approximately 1446 BCE, placing the subsequent construction of the Ark shortly thereafter at Mount Sinai.[33] The Ark served as the central element of the Tabernacle, a portable sanctuary assembled per divine specifications in Exodus 25–31 and 35–40, housing the stone tablets of the Ten Commandments and symbolizing God's covenant presence among the Israelites during their 40-year desert sojourn.[34] Crafted from acacia wood overlaid with gold, the Ark was placed within the Holy of Holies, veiled from view, and the Tabernacle's movements dictated by a divine cloud or pillar of fire that rested upon it, signaling when the camp should advance or halt (Exodus 40:36–38; Numbers 9:15–23).[35] During the wanderings, the Ark functioned primarily as a focal point for divine guidance and worship, carried by Levitical Kohathites on poles to avoid direct contact, ensuring ritual purity amid the nomadic existence marked by hardships like thirst and rebellion (Numbers 4:4–15; 10:33–36).[36] The biblical narrative attributes supernatural interventions to the Ark's proximity, such as the parting of waters at Rephidim for provision, though these accounts lack independent archaeological corroboration and reflect theological emphases on covenant fidelity rather than empirical historical records.[37] This mobility underscored the Ark's role in maintaining communal identity and Yahweh's sovereignty over the nomadic tribes, transitioning from Sinai's theophany to preparations for settlement. As the period of wanderings concluded under Joshua's leadership, the Ark played a pivotal role in the transition to Canaan, with priests bearing it ahead of the people to cross the Jordan River, where the waters reportedly halted upstream upon the Ark's entry, enabling passage on dry ground—a event paralleled to the Red Sea crossing and framed as confirmatory of Joshua's authority (Joshua 3:1–17).[38] Twelve stones were then erected from the riverbed as a memorial at Gilgal, the site's initial encampment east of Jericho, where the Ark was established as the cultic center for circumcision renewals and Passover observance, marking the end of manna provision and the onset of settled worship (Joshua 4:19–5:12).[39] This placement at Gilgal positioned the Ark for early conquest phases, emphasizing its narrative function in manifesting divine aid without implying verified causality beyond scriptural testimony.[40]Military and Oracular Functions

The Ark of the Covenant featured centrally in Israelite military endeavors during the conquest of Canaan, embodying Yahweh's presence and ensuring success contingent on covenantal fidelity. Priests carried the Ark ahead of the people across the Jordan River in Joshua 3, where its placement in the riverbed halted the waters upstream, enabling the nation to traverse on dry ground as a prelude to warfare.[41] This act signified divine empowerment through the Ark, marking the transition from wilderness to battleground.[42] In the assault on Jericho recorded in Joshua 6, armed men preceded seven priests bearing rams' horns and the Ark in a daily circumambulation of the city for six days, culminating on the seventh day with seven circuits, trumpet blasts, and a shout that precipitated the walls' collapse, yielding unconditional victory. The narrative attributes the outcome to Yahweh's intervention invoked via the Ark's ritual procession rather than conventional tactics.[43] Conversely, the initial foray against Ai in Joshua 7 resulted in rout despite inquiries before the Ark, traced to Achan's covert violation of spoils prohibitions; post-atonement, an ambush strategy prevailed, illustrating defeats as consequences of disobedience despite the Ark's symbolic deployment.[44] As an oracular instrument, the Ark represented Yahweh's throne, with the mercy seat serving as the site for divine speech and revelation per Exodus 25:22, where God pledged to convene and issue directives. High priestly consultations employed the Urim and Thummim—objects housed in the ephod's breastplate—for discerning Yahweh's intent on warfare, appointments, and disputes, frequently proximate to the Ark in the sanctuary tent.[45] Numbers 27:21 mandates Joshua's deference to Eleazar's Urim inquiries "before Yahweh" for troop deployments, tying oracular verdicts to the Ark's precinct as the nexus of purported celestial causality over human affairs.[46]