Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Asceticism

View on WikipediaAsceticism[a] is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from worldly pleasures through self-discipline, self-imposed poverty, and simple living,[3] often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals.[4] Ascetics may withdraw from the world or continue to be part of their society, but typically adopt a frugal lifestyle,[5] characterized by the renunciation of material possessions and physical pleasures, and also spend time fasting while concentrating on religion, prayer, or meditation.[6] Some individuals have also attempted an ascetic lifestyle to free themselves from addictions to things such as alcohol, smoking, drugs, sex, porn, lavish food, and entertainment.[7]

Asceticism has been historically observed in many religious and philosophical traditions,[8] most notably among Ancient Greek philosophical schools[5] (Epicureanism, Gymnosophism, Stoicism, and Pythagoreanism),[5] Indian religions (Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism),[8] Abrahamic religions[8] (Christianity, Judaism, Islam),[8] and contemporary practices continue amongst some of their followers.[7] Practitioners abandon sensual pleasures and lead an abstinent lifestyle,[5] in the pursuit of redemption,[9] salvation,[6] or spirituality.[10] Many ascetics believe the action of purifying the body helps to purify the body and soul, and that in doing so, they will obtain a greater connection with the Divine or find inner peace.[5] This may take the form of rituals, the renunciation of wealth and sensual pleasures,[5] or self-mortification in order to pursue spiritual goals.[8]

However, ascetics maintain that self-imposed constraints bring them greater freedom in various areas of their lives, such as increased clarity of thought and the ability to resist potentially destructive temptations. Asceticism is seen in some ancient theologies as a journey towards spiritual transformation, where the simple is sufficient, the bliss is within, the frugal is plenty.[6] Inversely, several ancient religious traditions, such as Zoroastrianism, Ancient Egyptian religion,[11] the Dionysian Mysteries, and vāmācāra (left-handed Hindu Tantrism), abstain from ascetic practices and focus on various types of good deeds in the world and the importance of family life.

Etymology and meaning

[edit]The adjective "ascetic" derives from the ancient Greek term áskēsis, which means "training" or "exercise".[12] The original usage did not refer to self-denial, but to the physical training required for athletic events.[4] Its usage later extended to rigorous practices used in many major religious traditions, in varying degrees, to attain redemption and higher spirituality.[13]

Edward Cuthbert Butler classified asceticism into natural and unnatural forms:[14]

- "Natural asceticism" involves a lifestyle that reduces material aspects of life to the utmost simplicity and to a minimum. This may include minimal, simple clothing, sleeping on a floor or in caves, and eating a simple, minimal amount of food.[14] Natural asceticism, stated Wimbush and Valantasis, does not include maiming the body or harsher austerities that make the body suffer.[14]

- "Unnatural asceticism", in contrast, covers practices that go further, including body mortification, punishing one's own flesh, and habitual self-infliction of pain, such as sleeping on a bed of nails.[14]

Religion

[edit]Self-discipline and abstinence in some form and degree are parts of religious practice within many religious and spiritual traditions. Ascetic lifestyle is associated particularly with monks, nuns, and fakirs in Abrahamic religions, and bhikkhus, munis, sannyasis, vairagis, goswamis, and yogis in Indian religions.[15][16]

Abrahamic religions

[edit]Bahá'í Faith

[edit]In the Baháʼí Faith, according to Shoghi Effendi, the maintenance of a high standard of moral conduct is neither to be associated nor confused with any form of extreme asceticism, nor of excessive and bigoted puritanism. The religious standard set by Baháʼu'lláh, founder of the Baháʼí Faith, seeks under no circumstances to deny anyone the legitimate right and privilege to derive the fullest advantage and benefit from the manifold joys, beauties, and pleasures with which the world has been so plentifully enriched by God, who Baháʼís regard as an all-loving creator.[17]: 44

Christianity

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Christian mysticism |

|---|

|

Notable Christian authors of Late Antiquity such as Origen, Jerome, John Chrysostom, and Augustine of Hippo, interpreted meanings of the Christian Bible within a highly asceticized religious environment.[18] Scriptural examples of asceticism could be found in the lives of John the Baptist, Jesus, the twelve apostles, and Paul the Apostle.[18] The Dead Sea Scrolls revealed ascetic practices of the ancient Jewish sect of the Essenes, who took vows of abstinence to prepare for a holy war. An emphasis on an ascetic religious life was evident in both early Christian writings (e.g., the Philokalia) and practices (e.g., Hesychasm). Christian saints, including Paul the Hermit, Simeon Stylites, David of Wales, John of Damascus, Peter Waldo, Tamar of Georgia,[19] and Francis of Assisi practiced asceticism, as well.[18][20]

According to British historian and Roman Catholic theologian Richard Finn, much of early Christian asceticism has been traced to early Judaism, not to Ancient Greek asceticism.[6] Some of the ascetic thought in Christianity nevertheless, Finn states, has roots in Ancient Greek philosophy.[6] Virtuous living is often considered incompatible with a strong craving for bodily pleasures driven by desire and passion. In ancient theology, morality is typically viewed not merely as a balance between right and wrong, but as a form of spiritual transformation. In this perspective, simplicity is regarded as sufficient, inner bliss is valued, and frugality is seen as abundant.[6]

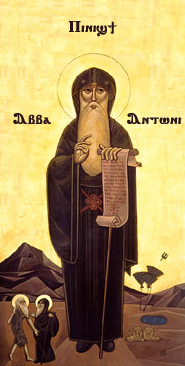

Middle Eastern deserts were at one time inhabited by thousands of male and female Christian ascetics, hermits, and anchorites,[21] including Anthony the Great (a.k.a. St. Anthony of the Desert), Mary of Egypt, and Simeon Stylites, collectively known as the Desert Fathers and Desert Mothers. In 963 CE, an association of monasteries called Lavras was formed on Mount Athos, according Eastern Orthodox tradition.[22] This became the most important center of Orthodox Christian ascetic groups in the centuries that followed.[22] In the modern era, Mount Athos and Meteora have remained a significant center.[23]

Sexual abstinence, as practiced by Encratites sect of Christianity, for example, was only one aspect of ascetic renunciation, and both natural and unnatural asceticism have been part of Christian asceticism. Other ascetic practices have included simple living, begging,[24] and fasting, as well as ethical practices like humility, compassion, meditation, patience, and prayer.[25] Evidence of extreme asceticism in Christianity appears in second-century texts and thereafter in both Eastern and Western Christian traditions, including the practices of chaining one's body to rocks, eating only grass,[26] praying seated on a pillar in the elements (e.g., the monk Simeon Stylites,[27] solitary confinement inside a cell, abandoning personal hygiene and adopting lifestyle of a beast, mortification of the flesh, and voluntary suffering.[24][28] Nevertheless, said practices were often rejected as beyond acceptable by ascetics like Barsanuphius of Gaza and John the Prophet.[29] Ascetic practices were linked to the Christian concepts of sin and redemption.[30][31]

The ascetic literature of early Christianity was influenced by pagan Greek philosophical traditions, especially those of Plato and Aristotle, which sought the perfect spiritual way of life.[32] According to Clement of Alexandria, philosophy and scriptures can be seen as "double expressions of one pattern of knowledge".[33] According to Evagrius, "body and the soul are there to help the intellect and not to hinder it".[34] Evagrius Ponticus (345–399 CE) was a highly educated monastic teacher who produced a large theological body of work,[33] mainly ascetic, including the Gnostikos (Ancient Greek: γνωστικός, gnōstikos, "learned", from γνῶσις, gnōsis, "knowledge"), also known as The Gnostic: To the One Made Worthy of Gnosis. The Gnostikos is the second volume of a trilogy containing the Praktikos, intended for young monks seeking apatheia (i.e., "a state of calm which is the prerequisite for love and knowledge"),[33] which would purify their intellect and make it impassible, revealing the truth hidden in every being. The third book, Kephalaia Gnostika, was meant for meditation by advanced monks. Those writings made him one of the most recognized ascetic teachers and scriptural interpreters of his time,[33] which included Clement of Alexandria and Origen.

Between the Middle Ages and the Protestant Reformation, Christian asceticism became more focused on communal life of studying and translating the Bible, prayer, preaching the Gospel, and other spiritual practices.[35] The proto-Protestant Lollards and Waldensians originated as ascetic lay movements within medieval Western Christianity, and both were persecuted by the Roman Catholic Church throughout several centuries.[20][36] Notable examples of Protestant asceticism are the Anabaptist Churches (Amish, Hutterites, Mennonites, Schwarzenau Brethren), Quakers, and Shakers, which espouse their pacifist ethics and separation from the world by simple living, which includes plain dressing and preference for antiquated technology.[35][37]

Islam

[edit]

The Arabic term for "asceticism" is zuhd.[38] The Islamic prophet Muhammad and his followers practiced asceticism.[39] However, contemporary mainstream Islam has not had a tradition of asceticism, but its Sufi groups[40] have cherished their own ascetic tradition for several centuries.[39][41][42] Islamic literary sources and historians report that during the early Muslim conquests of the Middle East and North Africa (7th–10th centuries), some of the Muslim warriors guarding the frontier settlements were also ascetics;[43][44] numerous historical accounts also report of some Christian monks that apostatized from Christianity, converted to Islam, and joined the jihad,[44] as well as of several Muslim warriors that repudiated Islam, converted to Christianity, and became Christian monks.[44][45] Monasticism is forbidden in Islam.[43][44][46] Scholars in the field of Islamic studies have argued that asceticism (zuhd) served as a precursor to the later doctrinal formations of Sufis that began to emerge in the tenth century[39] through the works of individuals such as al-Junayd, al-Qushayrī, al-Sarrāj, al-Hujwīrī and others.[47][48]

Sufism emerged and grew as a mystical,[39] somewhat hidden tradition in the mainstream Sunni and Shia denominations of Islam,[39] state Eric Hanson and Karen Armstrong, likely in reaction to "the growing worldliness of Umayyad and Abbasid societies".[49] Acceptance of asceticism emerged in Sufism slowly because it was contrary to the sunnah, states Nile Green, and early Sufis condemned "ascetic practices as unnecessary public displays of what amounted to false piety".[50] The ascetic Sufis were hunted and persecuted both by Sunni and Shia rulers, in various centuries.[51][52] Sufis were highly influential and greatly successful in spreading Islam between the 10th and 19th centuries,[39] particularly to the furthest outposts of the Muslim world in the Middle East and North Africa, the Balkans and Caucasus, the Indian subcontinent, and finally Central, Eastern, and Southeast Asia.[39] Some scholars have argued that Sufi Muslim ascetics and mystics played a decisive role in converting the Turkic peoples to Islam between the 10th and 12th centuries and Mongol invaders in Persia during the 13th and 14th centuries, mainly because of the similarities between the extreme, ascetic Sufis (fakirs and dervishes) and the Shamans of the traditional Turco-Mongol religion.[53][54]

Sufism was adopted and then grew particularly in the frontier areas of Islamic states,[39][53] where the asceticism of its fakirs and dervishes appealed to populations already used to the monastic traditions of Hinduism, Buddhism, and medieval Christianity.[49][55][56] Ascetic practices of Sufi fakirs have included celibacy, fasting, and self-mortification.[57][58] Sufi ascetics also participated in mobilizing Muslim warriors for holy wars, helping travelers, dispensing blessings through their perceived magical powers, and in helping settle disputes.[59] Ritual ascetic practices, such as self-flagellation (Tatbir), have been practiced by Shia Muslims annually at the Mourning of Muharram.[60]

Judaism

[edit]

Asceticism has not been a dominant theme within Judaism, but minor to significant ascetic traditions have been a part of Jewish spirituality.[61] The history of Jewish asceticism is traceable to the 1st millennium BCE with the references of the Nazirites, whose rules of practice are found in Book of Numbers 6:1–21.[62] The ascetic practices included not cutting the hair, abstaining from eating meat or grapes, abstention from wine, or fasting and hermit style living conditions for a period of time.[62] Literary evidence suggests that this tradition continued for a long time, well into the common era, and both Jewish men and women could follow the ascetic path, with examples such as the ascetic practices for fourteen years by Queen Helena of Adiabene, and by Miriam of Tadmor.[62][63] After the Jews returned from the Babylonian exile and the Mosaic institution was done away with, a different form of asceticism arose when Antiochus IV Epiphanes threatened the Jewish religion in 167 BCE. The Essene tradition of the Second Temple period is described as one of the movements within historic Jewish asceticism between 2nd century BCE and 1st century CE.[64]

The Ashkenazi Hasidim (Hebrew: חסידי אשכנז, romanized: Chassidei Ashkenaz) were a Jewish mystical, ascetic movement in the German Rhineland whose practices are documented in the texts of the 12th and 13th centuries.[65] Peter Meister states that this Jewish asceticism emerged in the 10th century, grew much wider with prevalence in Southern Europe and the Middle East through the Jewish pietistic movement.[66] According to Shimon Shokek, these ascetic practices were the result of an influence of medieval Christianity on Ashkenazi Hasidism. The Jewish faithful of this Hasidic tradition practiced the punishment of the body, self-torture by starvation, sitting in the open in freezing snow, or in the sun with fleas in summer, all with the goal of purifying the soul and turning one's attention away from the body unto the soul.[65]

Ascetic Jewish sects existed in ancient and medieval era times,[67] most notably the Essenes. According to Allan Nadler, Professor Emeritus of Religious Studies and Former Director of the Jewish Studies Program at Drew University, two most significant examples of medieval Jewish asceticism have been the Havoth ha-Levavoth and Chassidei Ashkenaz.[61] Pious self-deprivation was a part of the dualism and mysticism in these ascetic groups. This voluntary separation from the world was called Perishuth, and the Jewish society widely accepted this tradition in the late medieval era.[61] Extreme forms of ascetic practices have been opposed or controversial in the Hasidic movement.[68]

Another significant school of Jewish asceticism appeared in the 16th century, led from Safed.[69] These mystics engaged in radical material abstentions and self-mortification with the belief that this helps them transcend the created material world, reach and exist in the mystical spiritual world. A studied example of this group was Hayyim ben Joseph Vital, and their rules of ascetic lifestyle (Hanhagoth) are documented.[61][70]

Indian religions

[edit]

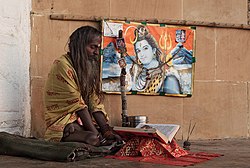

Asceticism is found in both non-theistic and theistic traditions within Indian religions. The origins of the practice are ancient, and a heritage shared by the three major Indian religions: Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism. They are referred to by many names, such as Sadhu, Pravrajita, Bhikshu, Yati, etc.[71]

Asceticism in Indian religions includes a spectrum of diverse practices, ranging from the mild self-discipline, self-imposed poverty, and simple living typical of Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism,[72][73] to more severe austerities and self-mortification practices of monks in Jainism and now extinct Ajivikas in the pursuit of salvation.[74] Some ascetics live as hermits relying on whatever food they can find in the forests, then sleep and meditate in caves; others travel from one holy site to another while sustaining their body by begging for food; yet others live in monasteries as monks or nuns.[75] Some ascetics live like priests and preachers, other ascetics are armed and militant,[75] to resist any persecution—a phenomenon that emerged after the Muslim invasions of India during the Middle Ages.[76][77] Self-torture is a relatively uncommon practice but one that attracts public attention. In Indian traditions such as Buddhism and Hinduism, self-mortification is typically criticized.[75] However, Indian mythologies also describe numerous ascetic gods or demons who pursued harsh austerities for decades or centuries that helped each gain special powers.[78]

Buddhism

[edit]

Buddhism is devoted primarily to awakening or enlightenment (bodhi), Nirvāṇa ("blowing out"), and liberation (vimokṣa) from all causes of suffering (duḥkha) due to the existence of sentient beings in saṃsāra (the cycle of compulsory birth, death, and rebirth) through the threefold trainings (ethical conduct, meditative absorption, and wisdom). Classical Indian Buddhism emphasized the importance of the individual's self-cultivation (through numerous spiritual practices like keeping ethical precepts, Buddhist meditation, and worship) in the process of liberation from the defilements which keep us bound to the cycle of rebirth. According to the standard Buddhist scholastic understanding, liberation arises when the proper elements (dhārmata) are cultivated and when the mind has been purified of its attachment to fetters and hindrances that produce unwholesome mental factors (various called defilements, poisons, or fluxes).[79]

The historical Buddha (c. 5th century BCE) adopted an extreme ascetic life in search of enlightenment.[1][80] However, after enlightenment he rejected extreme asceticism in favor of a more moderated version, the "Middle Way".[1][81] The Buddha defined his teaching as "the Middle Way" (Pāli: majjhimāpaṭipadā). In the Dharmacakrapravartana Sūtra, this is used to refer to the fact that his teachings steer a middle course between the extremes of asceticism and bodily denial (as practiced by the Jains and other Indian ascetic groups) and sensual hedonism or indulgence. Many Śramaṇa ascetics of the Buddha's time placed much emphasis on a denial of the body, using practices such as fasting, to liberate the mind from the body. Gautama Buddha, however, realized that the mind was embodied and causally dependent on the body, and therefore that a malnourished body did not allow the mind to be trained and developed.[82] Thus, Buddhism's main concern is not with luxury or poverty, but instead with the human response to circumstances.[83]

Another related teaching of the historical Buddha is "the teaching through the middle" (majjhena dhammaṃ desana), which claims to be a metaphysical middle path between the extremes of eternalism and annihilationism, as well as the extremes of existence and non-existence.[84][85] This idea would become central to later Buddhist metaphysics, as all Buddhist philosophies would claim to steer a metaphysical middle course.

According to Hajime Nakamura and other scholars, some early Buddhist texts suggest that asceticism was a part of Buddhist practice in its early days.[81][86] Further, in practice, records from about the start of the common era through the 19th century suggest that asceticism continued to be a part of Buddhism, both in Theravada and Mahayana traditions.

Theravada

[edit]Textual evidence suggests that ascetic practices were a part of the Buddhist tradition in Sri Lanka by the third century BCE, and this tradition continued through the medieval era in parallel to sangha style monastic tradition.[87]

In the Theravada tradition of Thailand, medieval texts report of ascetic monks who wander and dwell in the forest or crematory alone, do austere practices, and these came to be known as Thudong.[88][89] Ascetic Buddhist monks have been and continue to be found in Myanmar, and as in Thailand, they are known to pursue their own version of Buddhism, resisting the hierarchical institutionalized sangha structure of monasteries in Buddhism.[90]

Mahayana

[edit]In the Mahayana tradition, asceticism with esoteric and mystical meanings became an accepted practice, such as in the Tendai and Shingon schools of Japanese Buddhism.[87] These Japanese practices included penance, austerities, ablutions under a waterfall, and rituals to purify oneself.[87] Japanese records from the 12th century record stories of monks undertaking severe asceticism, while records suggest that 19th-century Nichiren Buddhist monks woke up at midnight or 2:00 am daily, and performed ascetic water purification rituals under cold waterfalls.[87] Other practices include the extreme ascetic practices of eating only pine needles, resins, seeds and ultimately self-mummification, while alive, or Sokushinbutsu (miira) in Japan.[91][92][93]

In Chinese Buddhism, self-mummification ascetic practices were less common but recorded in the Ch'an (Zen Buddhism) tradition there.[94] More ancient Chinese Buddhist asceticism, somewhat similar to Sokushinbutsu are also known, such as the public self-immolation (self-cremation, as shaoshen 燒身 or zifen 自焚)[95] practice, aimed at abandoning the impermanent body.[note 1] The earliest-documented ascetic Buddhist monk biography is of Fayu (法羽) in 396 CE, followed by more than fifty documented cases in the centuries that followed including that of monk Daodu (道度).[98][99] This was considered as evidence of a renunciant bodhisattva, and may have been inspired by the Jataka tales wherein the Buddha in his earlier lives immolates himself to assist other living beings,[100] or by the Bhaiṣajyaguruvaiḍūryaprabhārāja-related teachings in the Lotus Sutra.[101] Historical records suggest that the self-immolation practices were observed by nuns in Chinese Buddhism as well.[102]

The Chinese Buddhist asceticism practices, states James Benn, were not an adaptation or import of Indian ascetic practices, but an invention of Chinese Buddhists, based on their unique interpretations of Saddharmapuṇḍarīka or Lotus Sūtra.[103] It may be an adoption of more ancient pre-Buddhist Chinese practices,[104][105] or from Taoism.[102] It is unclear if self-immolation was limited primarily to Chinese asceticism tradition, and strong evidence of it being a part of a large scale, comprehensive ascetic program among Chinese Buddhists is lacking.[97]

Hinduism

[edit]

Renunciation from worldly life and a pursuit of spiritual life, either as a part of a monastic community or as a hermit, has been a historic tradition of Hinduism since ancient times. The renunciation tradition is called Sannyasa, and this is not the same as asceticism—which typically connotes severe self-denial and self-mortification. Sannyasa often involved a simple life, one with minimal or no material possessions, study, meditation and ethical living. Those who undertook this lifestyle were called Sannyasi, Sadhu, Yati,[106] Bhiksu, Pravrajita/Pravrajitā[107] and Parivrajaka in Hindu texts.[108] The term with a meaning closer to asceticism in Hindu texts is Tapas, but it too spans a spectrum of meanings ranging from inner heat, to self-mortification and penance with austerities, to meditation and self-discipline.[73][109][110]

The 11th century literary work Yatidharmasamuccaya is a Vaishnava text that summarizes ascetic practices in Vaishnavism tradition of Hinduism.[111] In Hindu traditions, as with other Indian religions, both men and women have historically participated in a diverse spectrum of ascetic practices.[10]

Vedas and Upanishads

[edit]Asceticism-like practices are hinted at in the Vedas, but these hymns have been variously interpreted as referring to early Yogis and loner renouncers. One such mention is in the Kesin hymn of the Rigveda, where Keśins ("long-haired" ascetics) and Munis ("silent ones") are described.[112][113] These Kesins of the Vedic era, are described as follows by Karel Werner:[114]

The Keśin does not live a normal life of convention. His hair and beard grow longer, he spends long periods of time in absorption, musing and meditating and therefore he is called "sage" (muni). They wear clothes made of yellow rags fluttering in the wind, or perhaps more likely, they go naked, clad only in the yellow dust of the Indian soil. But their personalities are not bound to earth, for they follow the path of the mysterious wind when the gods enter them. He is someone lost in thoughts: he is miles away.

— Karel Werner (1977), "Yoga and the Ṛg Veda: An Interpretation of the Keśin Hymn"[114]

The Vedic and Upanishadic texts of Hinduism, states Mariasusai Dhavamony, do not discuss self-inflicted pain, but do discuss self-restraint and self-control.[115] The monastic tradition of Hinduism is evidenced in first millennium BCE, particularly in its Advaita Vedanta tradition. This is evidenced by the oldest Sannyasa Upanishads, because all of them have a strong Advaita Vedanta outlook.[116] Most of the Sannyasa Upanishads present a Yoga and nondualism (Advaita) Vedanta philosophy.[117][118] The 12th-century Shatyayaniya Upanishad is a significant exception, which presents qualified dualistic and Vaishnavism (Vishishtadvaita Vedanta) philosophy.[118][119] These texts mention a simple, ethical lifestyle but do not mention self-torture or body mortification. For example:

These are the vows a Sannyasi must keep:

Abstention from injuring living beings, truthfulness, abstention from appropriating the property of others, abstention from sex, liberality (kindness, gentleness) are the major vows. There are five minor vows: abstention from anger, obedience towards the guru, avoidance of rashness, cleanliness, and purity in eating. He should beg (for food) without annoying others, any food he gets he must compassionately share a portion with other living beings, sprinkling the remainder with water he should eat it as if it were a medicine.

— Baudhayana Dharmasūtra, II.10.18.1–10[120]

Similarly, the Nirvana Upanishad asserts that the Hindu ascetic should hold, according to Patrick Olivelle, that "the sky is his belief, his knowledge is of the absolute, union is his initiation, compassion alone is his pastime, bliss is his garland, the cave of solitude is his fellowship", and so on, as he proceeds in his effort to gain self-knowledge (or soul-knowledge) and its identity with the Hindu metaphysical concept of Brahman.[121] Other behavioral characteristics of the Sannyasi include: ahimsa (non-violence), akrodha (not become angry even if you are abused by others),[122] disarmament (no weapons), chastity, bachelorhood (no marriage), avyati (non-desirous), amati (poverty), self-restraint, truthfulness, sarvabhutahita (kindness to all creatures), asteya (non-stealing), aparigraha (non-acceptance of gifts, non-possessiveness) and shaucha (purity of body speech and mind).[123][124]

Bhagavad Gita

[edit]In the Bhagavad Gita, verse 17.5 criticizes a form of asceticism that diverges from scriptural guidance and is driven by pride, ego, or attachment, rather than for genuine spiritual growth. Verse 17.6 extends the criticism of such ascetic practices, noting that they are considered harmful to both the practitioner's body and the divine within. With these two verses, Krishna emphasizes that true ascetic practices should align with scriptural teachings and aim towards higher spiritual goals.[125]

Some people who undertake acts of austerity perform ferocious deeds not sanctioned by scripture. They are motivated by hypocrisy and egotism, and are beset by the power of desire and passion.

— Bhagavad Gita, Verse 17.5

Jainism

[edit]

Asceticism in one of its most intense forms can be found in Jainism. Ascetic life may include nakedness symbolizing non-possession of even clothes, fasting, body mortification, penance and other austerities, in order to burn away past karma and stop producing new karma, both of which are believed in Jainism to be essential for reaching siddha and moksha (liberation from rebirths, salvation).[126][127][128] In Jainism, the ultimate goal of life is to achieve the liberation of soul from endless cycle of rebirths (moksha from samsara), which requires ethical living and asceticism. Most of the austerities and ascetic practices can be traced back to Mahavira, the twenty-fourth Tirthankara who practiced 12 years of asceticism before reaching enlightenment.[129][130]

Jain texts such as Tattvartha Sutra and Uttaradhyayana Sutra discuss ascetic austerities to great lengths and formulations. Six outer and six inner practices are most common, and often repeated in later Jain texts.[131] According to John Cort, outer austerities include complete fasting, eating limited amounts, eating restricted items, abstaining from tasty foods, mortifying the flesh and guarding the flesh (avoiding anything that is a source of temptation).[132] Inner austerities include expiation, confession, respecting and assisting mendicants, studying, meditation and ignoring bodily wants in order to abandon the body.[132]

The Jain text of Kalpa Sūtra describes Mahavira's asceticism in detail, whose life is a source of guidance on most of the ascetic practices in Jainism:[133]

The Venerable Ascetic Mahavira for a year and a month wore clothes; after that time he walked about naked, and accepted the alms in the hollow of his hand. For more than twelve years the Venerable Ascetic Mahivira neglected his body and abandoned the care of it; he with equanimity bore, underwent, and suffered all pleasant or unpleasant occurrences arising from divine powers, men, or animals.

— Kalpa Sutra 117

Both Mahavira and his ancient Jaina followers are described in Jainism texts as practicing body mortification and being abused by animals as well as people, but never retaliating and never initiating harm or injury (ahimsa) to any other being.[134] With such ascetic practices, he burnt off his past Karma, gained spiritual knowledge, and became a Jina.[134] These austere practices are part of the monastic path in Jainism.[135] The practice of body mortification is called kaya klesha in Jainism and is found in verse 9.19 of the Tattvartha Sutra by Umaswati, the most authoritative, oldest surviving Jaina philosophical text.[136][137]

Monastic practice

[edit]In Jain monastic practice, the monks and nuns take ascetic vows after renouncing all relations and possessions. The vows include a complete commitment to nonviolence (Ahimsa). They travel from city to city, often crossing forests and deserts, and always barefoot. Jain ascetics do not stay in a single place for more than two months to prevent attachment to any place.[138][139] However, during the four months of monsoon (rainy season) known as chaturmaas, they stay at a single place to avoid killing life forms that thrive during the rains.[140] Jain monks and nuns practice complete celibacy. They do not touch or share a sitting platform with a person of the opposite sex.[citation needed]

Jain ascetics follow a strict vegetarian diet without root vegetables. Prof. Pushpendra K. Jain explains:

Clearly enough, to procure such vegetables and fruits, one must pull out the plant from the root, thus destroying the entire plant, and with it all the other micro organisms around the root. Fresh fruits and vegetables should be plucked only when ripe and ready to fall off, or ideally after they have fallen off the plant. In case they are plucked from the plants, only as much as required should be procured and consumed without waste.[141]

The monks of Śvetāmbara sub-tradition within Jainism do not cook food but solicit alms from householders. Digambara monks have only a single meal a day.[142] Neither group will beg for food, but a Jain ascetic may accept a meal from a householder, provided that the latter is pure of mind and body and offers the food of his own volition and in the prescribed manner. During such an encounter, the monk remains standing and eats only a measured amount. A routine feature of Jain asceticism is fasting periods, where adherents abstain from consuming food, and sometimes water, only during daylight hours, for up to 30 days. Some monks avoid (or limit) medicine or hospitalization out of disregard for the physical body.[141]

Śvētāmbara monks and nuns wear only unstitched white robes (an upper and lower garment), and own one bowl they use for eating and collecting alms. Male Digambara sect monks do not wear any clothes, carry nothing with them except a soft broom made of shed peacock feathers (pinchi) to gently remove any insect or living creature in their way or bowl, and they eat with their hands.[142] They sleep on the floor without blankets and sit on wooden platforms. Other austerities include meditation in seated or standing posture near riverbanks in the cold wind, or meditation atop hills and mountains, especially at noon when the sun is at its fiercest.[143] Such austerities are undertaken according to the physical and mental limits of the individual ascetic.

When death is imminent from an advanced age or terminal disease, many Jain ascetics take a final vow of Santhara or Sallekhana, a fast to peaceful and detached death, by first reducing intake of and then ultimately abandoning all medicines, food, and water.[144] Scholars state that this ascetic practice is not suicide, but a form of natural death, done without passion or turmoil or suddenness, and because it is done without active violence to the body.[144]

Sikhism

[edit]While Sikhism treats lust as a vice, it has at the same time unmistakably pointed out that man must share the moral responsibility by leading the life of a householder. What is important is to be God-centred. According to Sikhism, ascetics are certainly not on the right path.[145] When Guru Nanak visited Gorakhmata, he discussed the true meaning of asceticism with some yogis:[146]

Asceticism doesn't lie in ascetic robes, or in walking staff, nor in the ashes. Asceticism doesn't lie in the earring, nor in the shaven head, nor blowing a conch. Asceticism lies in remaining pure amidst impurities. Asceticism doesn't lie in mere words; He is an ascetic who treats everyone alike. Asceticism doesn't lie in visiting burial places, It lies not in wandering about, nor in bathing at places of pilgrimage. Asceticism is to remain pure amidst impurities.

— Guru Nanak[146]

Other religions

[edit]Inca religion

[edit]In Inca religion of medieval South America, asceticism was practiced.[147] The high priests of the Inca people lived an ascetic life, which included fasting, chastity and eating simple food.[148] The Jesuit records report Christian missionaries encountering ascetic Inca hermits in the Andean mountains.[149]

Taoism

[edit]Historical evidence suggests that the monastic tradition in Taoism practiced asceticism, and the most common ascetic practices included fasting, complete sexual abstinence, self-imposed poverty, sleep deprivation, and secluding oneself in the wilderness.[150][151] More extreme and unnatural ascetic Taoist practices have included public self-drowning and self-cremation.[152] The goal of this spectrum of practices, like in other religions, was to reach the divine and get past the mortal body.[153] According to Stephen Eskildsen, asceticism continues to be a part of modern Taoism.[154][155]

Zoroastrianism

[edit]In Zoroastrianism, active participation in life through good thoughts, good words and good deeds is necessary to ensure happiness and to keep the chaos at bay. This active participation is a central element in Zoroaster's concept of free will. In the Avesta, the sacred scriptures of Zoroastrianism, fasting and mortification are forbidden.[156]

Academic views

[edit]Sociological and psychological views

[edit]Early 20th-century German sociologist Max Weber made a distinction between innerweltliche and ausserweltliche asceticism, which means (roughly) "inside the world" and "outside the world", respectively. Talcott Parsons translated these as "worldly" and "otherworldly"—however, some translators use "inner-worldly", and this is more in line with inner world explorations of mysticism, a common purpose of asceticism. "Inner- or Other-worldly" asceticism is practised by people who withdraw from the world to live an ascetic life (this includes monks who live communally in monasteries, as well as hermits who live alone). "Worldly" asceticism refers to people who live ascetic lives but do not withdraw from the world:

Wealth is thus bad ethically only in so far as it is a temptation to idleness and sinful enjoyment of life, and its acquisition is bad only when it is with the purpose of later living merrily and without care.

Weber claimed this distinction originated in the Protestant Reformation, but later became secularized, so the concept can be applied to both religious and secular ascetics.[158]

The 20th-century American psychological theorist David McClelland suggested worldly asceticism specifically targets worldly pleasures that "distract" people from their calling, and may accept worldly pleasures that are not distracting. As an example, he pointed out Quakers have historically objected to bright-coloured clothing, but wealthy Quakers often made their drab clothing out of expensive materials. The color was considered distracting, but the materials were not. Amish groups use similar criteria to make decisions about which modern technologies to use and which to avoid.[159]

Nietzsche's and Epicurus's view

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2012) |

In the third essay ("What Do Ascetic Ideals Mean?")[160] from his 1887 book On the Genealogy of Morals, Friedrich Nietzsche[161] discusses what he terms the "ascetic ideal" and its role in the formulation of morality along with the history of the will. In the essay, Nietzsche describes how such a paradoxical action as asceticism might serve the interests of life: through asceticism, one can overcome one's desire to perish from pain and despair and attain mastery over oneself. In this way, one can express both ressentiment and the will to power. Nietzsche describes the morality of the ascetic priest as characterized by Christianity as one where, finding oneself in pain or despair and desiring to perish from it, the will to live causes one to place oneself in a state of hibernation and denial of the material world in order to minimize that pain and thus preserve life, a technique which Nietzsche locates at the very origin of secular science as well as of religion. He associated the "ascetic ideal" with Christian decadence.[162][163][164]

Asceticism is not always life-denying or pleasure-denying. Some ascetic practices have actually been carried out as disciplines of pleasure. Epicurus taught a philosophy of pleasure, but he also engaged in ascetic practices like fasting. This may have been done in the service of testing the limits of nature, of desires, of pleasure, and of his own body. In the eighth of his Principal Doctrines, Epicurus says that we sometimes choose pains if greater pleasures ensue from them, or avoid pleasures if greater pains ensue, and in the "autarchy" portion of his Letter to Menoeceus, he teaches that living frugally can help us to better enjoy luxuries when we have them.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ /əˈsɛtɪsɪzəm/; from Ancient Greek ἄσκησις (áskēsis) 'exercise, training'

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Laumakis, Stephen J. (2023) [2018]. "Chapter 3: The Basic Teachings of the Buddha". An Introduction to Buddhist Philosophy. Cambridge Introductions to Philosophy (2nd ed.). Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 48. doi:10.1017/9781009337076.005. ISBN 9781009337076.

Having lived and experienced both the excesses and deficiencies of the extremes of pleasure and deprivation, the Buddha was painfully aware of their debilitating consequences. On the one hand, the pleasurable excesses of his princely life were not satisfying for at least two reasons: while enjoying them he was poignantly aware of their imminent passing, and while not enjoying them he found himself longing for what he knew could not truly satisfy him because of their inherent transience. On the other hand, his experiments with extreme ascetic practices left him physically emaciated and mentally unfulfilled. Moreover, these practices failed to produce their advertised goals and promised ends; they left him both mentally distracted and physically enfeebled. So, his followers insisted that one of the most basic teachings of the "Awakened One" was his insistence on the "Middle Way" between the two extremes of pleasure and pain.

- ^ William Cook (2008), Francis of Assisi: The Way of Poverty and Humility, Wipf and Stock Publishers, ISBN 978-1556357305, p. 46–47.

- ^ Randall Collins (2000), The sociology of philosophies: a global theory of intellectual change, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0674001879, p. 204.

- ^ a b "Asceticism". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Finn, Richard (2009). "Pagan asceticism: cultic and contemplative purity". Asceticism in the Graeco-Roman World. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 9–33. ISBN 978-1-139-48066-6. LCCN 2009009367.

- ^ a b c d e f Finn, Richard (2009). "Christian asceticism before Origen". Asceticism in the Graeco-Roman World. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 94–99. ISBN 978-1-139-48066-6. LCCN 2009009367.

- ^ a b Deezia, Burabari S. (Autumn 2017). "IAFOR Journal of Ethics, Religion & Philosophy" (PDF). Asceticism: A Match Towards the Absolute. 3 (2): 14. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Furey, Constance M. (March 2012). "Body, Society, and Subjectivity in Religious Studies". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 80 (1). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Academy of Religion: 7–33. doi:10.1093/jaarel/lfr088. ISSN 1477-4585. LCCN sc76000837. OCLC 1479270. PMID 22530258. S2CID 45476670.

- ^ Valantasis, Richard; Wimbush, Vincent L. (2002). Asceticism. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 247, 351. ISBN 978-0-19-803451-3.

- ^ a b Denton, Lynn (1992). Leslie, Julia (ed.). Roles and Rituals for Hindu Women. Delhi and London: Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 212–219. ISBN 978-81-208-1036-5.

- ^ Wilson, John A. (1969). "Egyptian Secular Songs and Poems". Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 467.

- ^ "Asceticism | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ Clarke, Paul A. B.; Linzey, Andrew (1996). Dictionary of Ethics, Theology and Society. Routledge Reference. London: Taylor & Francis. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-415-06212-1.

- ^ a b c d Wimbush, Vincent L.; Valantasis, Richard (2002). Asceticism. Oxford University Press. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-0-19-803451-3.

- ^ Waite, Maurice (2009). Oxford Thesaurus of English. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-19-956081-3.

- ^ Wiltshire, Martin G. (1990). Ascetic Figures Before and in Early Buddhism: The Emergence of Gautama as the Buddha. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. pp. xvi. ISBN 978-3-11-009896-9.

- ^ Effendi, Shoghi. Advent of Divine Justice.

- ^ a b c Campbell, Thomas (2022) [1907]. "Asceticism". In Knight, Kevin (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New Advent. Archived from the original on 16 March 2022. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ Machitadze, Zakaria (2006). "Holy Queen Tamar (†1213)". Lives of the Georgian Saints. Saint Herman Press. ISBN 978-1-887904-65-0 – via OrthoChristian.Com.

- ^ a b Wylie, J. A. (1880). History of the Waldenses. Cornell University Library. London, New York [etc.]: Cassell & Company.

- ^ For a study of the continuation of this early tradition in the Middle Ages, see Marina Miladinov, Margins of Solitude: Eremitism in Central Europe between East and West (Zagreb: Leykam International, 2008).

- ^ a b Johnston, William M. (2013). Encyclopedia of Monasticism (1st ed.). London and New York: Routledge. pp. 290, 548, 577. ISBN 978-1-136-78716-4.

- ^ Johnston, William M. (2013). Encyclopedia of Monasticism (1st ed.). London and New York: Routledge. pp. 548–550. ISBN 978-1-136-78716-4.

- ^ a b Barrier, Jeremy (2013). "Asceticism in the Acts of Paul and Thecla's Beatitudes". In Weidemann, Hans-Ulrich (ed.). Asceticism and Exegesis in Early Christianity: The Reception of New Testament Texts in Ancient Ascetic Discourses. Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus/Studien zur Umwelt des Neuen Testaments. Vol. 10. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 163–185. ISBN 978-3-525-59358-5.

- ^ Elizabeth A. Clark. Reading Renunciation: Asceticism and Scripture in Early Christianity. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1999.

- ^ Robinson, Thomas A.; Rodrigues, Hillary P. (2014). World Religions: A Guide to the Essentials. Ada, Michigan: Baker Academic. pp. 147–148. ISBN 978-1-4412-1972-5.

- ^ Johnston, William M. (2013). Encyclopedia of Monasticism (1st ed.). London and New York: Routledge. pp. 582–583. ISBN 978-1-136-78716-4.

- ^ Johnston, William M. (2013). Encyclopedia of Monasticism (1st ed.). London and New York: Routledge. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-136-78716-4.

- ^ Torrance, Alexis (2013). Repentance in Late Antiquity: Eastern Asceticism and the Framing of the Christian Life C.400-650 CE. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-19-966536-5. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ Chin, Catherine M. (2013). "Who is the Ascetic Exegete?". In Weidemann, Hans-Ulrich (ed.). Asceticism and Exegesis in Early Christianity: The Reception of New Testament Texts in Ancient Ascetic Discourses. Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus/Studien zur Umwelt des Neuen Testaments. Vol. 10. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 203–218. ISBN 978-3-525-59358-5.

- ^ Peeters, Evert; Van Molle, Leen; Wils, Kaat (2011). "Introduction to Modern Asceticism: A Historical Exploration". In Peeters, Evert; Van Molle, Leen; Wils, Kaat (eds.). Beyond Pleasure: Cultures of Modern Asceticism. London and New York: Berghahn Books. pp. 1–18. doi:10.3167/9781845457730. ISBN 978-1-84545-987-1. JSTOR j.ctt9qd2zc.5.

- ^ Rubenson, Samuel (2007). "Asceticism and monasticism, I: Eastern". In Casiday, Augustine; Norris, Frederick W. (eds.). The Cambridge History of Christianity: Constantine to c. 600. Vol. 2. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 637–668. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521812443.029. ISBN 978-1139054133.

- ^ a b c d Young, Robin Darling (Spring 2001). "Evagrius the Iconographer: Monastic Pedagogy in the Gnostikos". Journal of Early Christian Studies. 9 (1). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press: 53–71. doi:10.1353/earl.2001.0017. S2CID 170981765.

- ^ Plested, Marcus (2004). The Macarian Legacy: The Place of Macarius-Symeon in the Eastern Christian Tradition. Oxford Theology and Religion Monographs. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 67. doi:10.1093/0199267790.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-926779-8.

- ^ a b Hamalis, Perry T. (2014) [2003]. "Asceticism". In Djupe, Paul A.; Olson, Laura R. (eds.). Encyclopedia of American Religion and Politics. New York: Facts On File. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-0-8160-7555-3. LCCN 2002033921.

- ^ Macy, Gary (1984). The theologies of the Eucharist in the early scholastic period: a study of the salvific function of the sacrament according to the theologians, c. 1080 – c. 1220. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-826669-3.

- ^ Davies, Alan (1999). "Tradition and Modernity in Protestant Christianity". In Ishwaran, K. (ed.). Ascetic Culture: Renunciation and Worldly Engagement. International Studies in Sociology and Social Anthropology. Vol. 73. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. p. 30. ISBN 978-90-04-47648-6. ISSN 0074-8684.

- ^ Meri, Josef W. (2004) [2002]. "The Friends of God". The Cult of Saints among Muslims and Jews in Medieval Syria. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 66–83. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199250783.003.0003. ISBN 978-0-19-155473-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cook, David (May 2015). "Mysticism in Sufi Islam". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.51. ISBN 9780199340378. Archived from the original on 28 November 2018. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ The World's Muslims: Religious Affiliations, Pew Research (2012).

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (2010). The Encyclopedia of Middle East Wars. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-Clio. p. 1176. ISBN 978-1-85109-948-1.

- ^ Crowe, Felicity; et al. (2011). Illustrated Dictionary of the Muslim World. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-7614-7929-1.

- ^ a b Sizgorich, Thomas (2009). Violence and Belief in Late Antiquity: Militant Devotion in Christianity and Islam. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 178–182. ISBN 978-0-8122-4113-6. LCCN 2008017407.

- ^ a b c d Sahner, Christian C. (June 2017). ""The Monasticism of My Community is Jihad": A Debate on Asceticism, Sex, and Warfare in Early Islam". Arabica. 64 (2). Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers: 149–183. doi:10.1163/15700585-12341453. ISSN 1570-0585. S2CID 165034994.

- ^ Sahner, Christian C. (April–June 2016). "Swimming against the Current: Muslim Conversion to Christianity in the Early Islamic Period". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 136 (2). American Oriental Society: 265–284. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.136.2.265. ISSN 0003-0279. LCCN 12032032. OCLC 47785421. S2CID 163469239.

- ^ Ruthven, Malise (2006). Islam in the World. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-19-530503-6.

The misogynism in Islam may perhaps be partly attributed to the absence of outlets for celibacy. Ascetical tendencies are usually strong among the pious: the whole history of Western religions illustrates an intimate connection between religious enthusiasm and sexual repression. In Islam, however, celibacy was explicitly discouraged both by the Prophet's own example and by the famous hadith, "There is no monasticism in Islam – the monasticism (rahbaniya) of my community is the jihad".

- ^ Knysh, Alexander (2010) [1999]. Islamic Mysticism: A Short History. Themes in Islamic Studies. Vol. 1. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 1–30. ISBN 978-90-04-10717-5.

- ^ Karamustafa, Ahmet T. (2007). Sufism: The Formative Period. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25269-1.

- ^ a b Hanson, Eric O. (2006). Religion and Politics in the International System Today. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 102–104. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511616457. ISBN 978-0-521-85245-6.

- ^ Green, Nile (2012). Sufism: A Global History. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 20–22. ISBN 978-1-4051-5765-0.

- ^ Başkan, Birol (2014). From Religious Empires to Secular States: State Secularization in Turkey, Iran, and Russia. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. pp. 77–80. ISBN 978-1-317-80204-4.

- ^ Armajani, Jon (2004). Dynamic Islam: Liberal Muslim Perspectives in a Transnational Age. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-7618-2967-6.

- ^ a b Findley, Carter V. (2005). "Islam and Empire from the Seljuks through the Mongols". The Turks in World History. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 56–66. ISBN 9780195177268. OCLC 54529318.

- ^ Amitai-Preiss, Reuven (January 1999). "Sufis and Shamans: Some Remarks on the Islamization of the Mongols in the Ilkhanate". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 42 (1). Leiden: Brill Publishers: 27–46. doi:10.1163/1568520991445605. ISSN 1568-5209. JSTOR 3632297.

- ^ Bashir, Shahzad (2013). Sufi Bodies: Religion and Society in Medieval Islam. Columbia University Press. pp. 9–11, 58–67. ISBN 978-0-231-14491-9.

- ^ Black, Antony (2011). The History of Islamic Political Thought: From the Prophet to the Present. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 241–242. ISBN 978-0-7486-8878-4.

- ^ Olson, Carl (2007). Celibacy and Religious Traditions. Oxford University Press. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-0-19-804181-8.

- ^ Metcalf, Barbara D. (2009). Islam in South Asia in Practice. Princeton University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-4008-3138-8.

- ^ Lapidus, Ira M. (2014). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press. p. 357. ISBN 978-1-139-99150-6.

- ^ Juergensmeyer, Mark; Roof, Wade Clark (2011). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. SAGE Publications. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-4522-6656-5.

- ^ a b c d Nadler, Allan (1999). The Faith of the Mithnagdim: Rabbinic Responses to Hasidic Rapture. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-0-8018-6182-6.

- ^ a b c Horn, Cornelia B. (2006). Asceticism and Christological Controversy in Fifth-Century Palestine. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 188–190 with footnotes. ISBN 978-0-19-927753-7.

- ^ Bockmuehl, Markus (2000). Jewish Law in Gentile Churches. London: A&C Black. pp. 38–40 with footnote 57. ISBN 978-0-567-08734-8.

- ^ Rosner, Brian S. (1994). Paul's Scripture and Ethics: A Study of 1 Corinthians 5–7. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 153–157. ISBN 90-04-10065-2.

- ^ a b Shokek, Shimon (2013). Kabbalah and the Art of Being: The Smithsonian Lectures (1st ed.). London and New York: Routledge. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-1-317-79738-8.

- ^ Meister, Peter (2004). German Literature Between Faiths: Jew and Christian at Odds and in Harmony. Lausanne: Peter Lang. pp. 41–43. ISBN 978-3-03910-174-0.

- ^ Meijers, Daniël (1992). Ascetic Hasidism in Jerusalem: The Guardian-Of-The-Faithful Community of Mea Shearim. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 14–19, 111–125. ISBN 90-04-09562-4.

- ^ Rabinowicz, Tzvi (1996). The Encyclopedia of Hasidism. Lanham, Maryland: Jason Aronson. pp. 7, 26–27, 191. ISBN 978-1-56821-123-7.

- ^ Wolfson, Elliot R. (2016). "Asceticism, Mysticism, and Messianism: A Reappraisal of Schechter's Portrait of Sixteenth-Century Safed". Jewish Quarterly Review. 106 (2). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press on behalf of the Herbert D. Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies (University of Pennsylvania): 165–177. doi:10.1353/jqr.2016.0007. ISSN 1553-0604. S2CID 171299402.

- ^ Teshima, Yūrō (1995). Zen Buddhism and Hasidism: A Comparative Study. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-0-7618-0003-3.

- ^ Michaels, Axel; Harshav, Barbara (2004). Hinduism: Past and Present. Princeton University Press. p. 315. ISBN 0-691-08952-3.

- ^ Gombrich, Richard F. (2006). Theravada Buddhism: A Social History from Ancient Benares to Modern Colombo. Routledge. pp. 44, 62. ISBN 978-1-134-21718-2.

- ^ a b Smith, Benjamin R. (2008). Mark Singleton and Jean Byrne (ed.). Yoga in the Modern World: Contemporary Perspectives. Routledge. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-134-05520-3.

- ^ Dundas, Paul (2003). The Jains (2nd ed.). Routledge. pp. 27, 165–166, 180. ISBN 978-0415266055.

- ^ a b c Michaels, Axel; Harshav, Barbara (2004). Hinduism: Past and Present. Princeton University Press. p. 316. ISBN 0-691-08952-3.

- ^ David N. Lorenzen (1978), Warrior Ascetics in Indian History, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 98(1): 61–75.

- ^ William Pinch (2012), Warrior Ascetics and Indian Empires, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1107406377.

- ^ Amore, Roy C.; Shinn, Larry D. (1981). Lustful Maidens and Ascetic Kings: Buddhist and Hindu Stories of Life. Oxford University Press. pp. 155–164. ISBN 978-0-19-536535-1.

- ^ Brunnhölzl, Karl (2004). The Center of the Sunlit Sky: Madhyamaka in the Kagyü Tradition. Nitartha Institute Series. Snow Lion. p. 131. ISBN 978-1559392181.

- ^ Buswell Jr., Robert E.; Lopez Jr., Donald S., eds. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 894. ISBN 978-1-4008-4805-8.

- ^ a b Nakamura, Hajime (1980). Indian Buddhism: A Survey with Bibliographical Notes. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 73 with footnote 2. ISBN 978-81-208-0272-8.

- ^ Panjvani, Cyrus; Buddhism: A Philosophical Approach (2013), p. 29

- ^ Swearer, Donald K. Ethics, wealth, and salvation: A study in Buddhist social ethics. Edited by Russell F. Sizemore. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1990. (from the introduction)

- ^ Wallis, Glenn (2007) Basic Teachings of the Buddha: A New Translation and Compilation, With a Guide to Reading the Texts, p. 114.

- ^ See: Kaccānagotta Sutta SN 12.15 (SN ii 16), translated by Bhikkhu Sujato

- ^ Liu, Shuxian; Allinson, Robert Elliott (1988). Harmony and Strife: Contemporary Perspectives, East & West. Chinese University Press. pp. 99 with footnote 25. ISBN 978-962-201-412-1.

- ^ a b c d Johnston, William M. (2000). Encyclopedia of Monasticism: A-L. Routledge. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-1-57958-090-2.

- ^ Buswell Jr., Robert E.; Lopez Jr., Donald S. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. pp. 22, 910. ISBN 978-1-4008-4805-8.

- ^ Taylor, James (1993). Forest Monks and the Nation State: An Anthropological and Historical Study in Northeastern Thailand. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 981-3016-49-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Powers, John (2015). The Buddhist World. Routledge. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-317-42017-0.

- ^ Ichiro Hori (1962), Self-Mummified Buddhas in Japan. An Aspect of the Shugen-Dô ("Mountain Asceticism") Sect, History of Religions, Vol. 1, No. 2 (Winter, 1962), pp. 222–242.

- ^ Boscaro, Adriana; Gatti, Franco; Raveri, Massimo (1990). Rethinking Japan: Social sciences, ideology & thought. Routledge. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-904404-79-1.

- ^ Lobetti, Tullio Federico (2013). Ascetic Practices in Japanese Religion. Routledge. pp. 130–136. ISBN 978-1-134-47273-4.

- ^ Williams, Paul (2005). Buddhism: Buddhism in China, East Asia, and Japan. Routledge. pp. 362 with footnote 37. ISBN 978-0-415-33234-7.

- ^ James A. Benn (2012), Multiple Meanings of Buddhist Self-Immolation in China – A Historical Perspective, Revue des Études Tibétaines, no. 25, p. 205.

- ^ Shufen, Liu (2000). "Death and the Degeneration of Life Exposure of the Corpse in Medieval Chinese Buddhism". Journal of Chinese Religions. 28 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1179/073776900805306720.

- ^ a b James A. Benn (2012), Multiple Meanings of Buddhist Self-Immolation in China – A Historical Perspective, Revue des Études Tibétaines, no. 25, p. 211.

- ^ Benn, James A. (2007). Burning for the Buddha: Self-Immolation in Chinese Buddhism. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 33–34, 82–84, 3–4. ISBN 978-0-8248-2992-6.

- ^ Yün-hua Jan (1965), Buddhist Self-Immolation in Medieval China, History of Religions, Vol. 4, No. 2 (Winter, 1965), pp. 243–268.

- ^ Benn, James A. (2007). Burning for the Buddha: Self-Immolation in Chinese Buddhism. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 112–114, 14–16. ISBN 978-0-8248-2992-6.

- ^ Benn, James A. (2007). Burning for the Buddha: Self-Immolation in Chinese Buddhism. University of Hawaii Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-8248-2992-6.

- ^ a b Pao-ch'ang, Shih; Tsai, Kathryn Ann (1994). Lives of the Nuns: Biographies of Chinese Buddhist Nuns from the Fourth to Sixth Centuries : a Translation of the Pi-chʻiu-ni Chuan. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 10–12, 65–66. ISBN 978-0-8248-1541-7.

- ^ James A. Benn (2012), Multiple Meanings of Buddhist Self-Immolation in China – A Historical Perspective, Revue des Études Tibétaines, no. 25, pp. 203–212, Quote: "Of all the forms of self-immolation, auto-cremation in particular seems to have been primarily created by medieval Chinese Buddhists. Rather than being a continuation or adaptation of an Indian practice (although there were Indians who burned themselves), as far as we can tell, auto-cremation was constructed on Chinese soil and drew on range of influences such as a particular interpretation of an Indian Buddhist scripture (the Saddharmapuṇḍarīka or Lotus Sūtra) along with indigenous traditions, such as burning the body to bring rain, that long pre-dated the arrival of Buddhism in China."

- ^ James A. Benn (2012), Multiple Meanings of Buddhist Self-Immolation in China – A Historical Perspective, Revue des Études Tibétaines, no. 25, p. 207.

- ^ James A. Benn (1998), Where Text Meets Flesh: Burning the Body as an Apocryphal Practice in Chinese Buddhism, History of Religions, Vol. 37, No. 4 (May, 1998), pp. 295–322.

- ^ yatin Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Koeln University, Germany.

- ^ pravrajitA Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Koeln University, Germany.

- ^ Patrick Olivelle (1981), "Contributions to the Semantic History of Saṃnyāsa," Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 101, No. 3, pp. 265–274.

- ^ Kaelber, W. O. (1976). "Tapas", Birth, and Spiritual Rebirth in the Veda, History of Religions, 15(4), pp. 343–386.

- ^ Sedlar, Jean W. (1980). India and the Greek world: a study in the transmission of culture. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-8476-6173-2.;

Lowitz, L. & Datta, R. (2004). Sacred Sanskrit Words: For Yoga, Chant, and Meditation. Stone Bridge Press, Incorporated; see Tapas or tapasya in Sanskrit means, the conditioning of the body through the proper kinds and amounts of diet, rest, bodily training, meditation, etc., to bring it to the greatest possible state of creative power. It involves practicing the art of controlling materialistic desires to attain moksha.Yoga, Meditation on Om, Tapas, and Turiya in the principal Upanishads, Archived 2013-09-08 at the Wayback Machine, Chicago, Illinois. - ^ Pprakāśa, Yādava (1995). Rules and Regulations of Brahmanical Asceticism: Yatidharmasamuccaya of Yādava Prakāśa. Translated by Olivelle, Patrick. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2283-0.

- ^ Flood, Gavin D. (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-521-43878-0.

- ^ Doniger O'Flaherty, Wendy (2005). The RigVeda. Penguin Classics. p. 137. ISBN 0140449892.

- ^ a b Werner, Karel (1977). "Yoga and the Ṛg Veda: An Interpretation of the Keśin Hymn (RV 10, 136)". Religious Studies. 13 (3): 289–302. doi:10.1017/S0034412500010076. S2CID 170592174.

- ^ Dhavamony, Mariausai (1982). Classical Hinduism. Gregorian Biblical University. pp. 368–369. ISBN 978-88-7652-482-0.

- ^ Stephen H. Phillips (1995), Classical Indian Metaphysics, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0812692983, p. 332 with note 68.

- ^ Antonio Rigopoulos (1998), Dattatreya: The Immortal Guru, Yogin, and Avatara, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791436967, pp. 62–63.

- ^ a b Olivelle, Patrick (1992). The Samnyasa Upanisads. Oxford University Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0195070453.

- ^ Antonio Rigopoulos (1998), Dattatreya: The Immortal Guru, Yogin, and Avatara, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791436967, p. 81 note 27.

- ^ Max Muller (Translator), Baudhayana Dharmasūtra Prasna II, Adhyaya 10, Kandika 18, The Sacred Books of the East, Vol. XIV, Oxford University Press, pages 279–281

- ^ Olivelle, Patrick (1992). The Samnyasa Upanisads. Oxford University Press. pp. 227–235. ISBN 978-0195070453.

- ^ Mayeul de Dreuille, The rule of Saint Benedict and the ascetic traditions from Asia to the West, p. 134.

- ^ Mariasusai Dhavamony (2002), Hindu-Christian Dialogue: Theological Soundings and Perspectives, ISBN 978-9042015104, pp. 96–97, 111–114.

- ^ Barbara Powell (2010), Windows Into the Infinite: A Guide to the Hindu Scriptures, Asian Humanities Press, ISBN 978-0875730714, pp. 292–297.

- ^ Sutton 2017, p. 241.

- ^ Cort 2001a, pp. 118–122.

- ^ Fujinaga 2003, pp. 205–212 with footnotes.

- ^ Balcerowicz 2015, pp. 144–150.

- ^ Doniger 1999, p. 549.

- ^ Winternitz 1993, pp. 408–409.

- ^ Cort 2001a, pp. 120–121.

- ^ a b Cort 2001a, pp. 120–122.

- ^ Jacobi, Hermann (1884). Müller, F. Max (ed.). The Kalpa Sūtra (Translated from Prakrit). Sacred Books of the East vol.22, Part 1. Oxford, England: The Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-7007-1538-X.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) Note: ISBN refers to the UK: Routledge (2001) reprint. URL is the scan version of the original 1884 reprint. - ^ a b Dundas 2002, p. 180.

- ^ Wiley 2009, p. 210.

- ^ Johnson, W. J. (1995). Harmless Souls: Karmic Bondage and Religious Change in Early Jainism with Special Reference to Umāsvāti and Kundakunda. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 197. ISBN 978-81-208-1309-0.

- ^ Vijay K. Jain 2011, p. 134.

- ^ Hermann Jacobi, "Sacred Books of the East", vol. 22: Gaina Sutras Part I, 1884.

- ^ "Jaina Sutras, Part I (SBE22) Index". Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2016-01-30.

- ^ Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D. (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase. pp. 207–208, see Jain Festivals. ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5.

- ^ a b Jain, P. K. "Dietary code of practice among the Jains". 34th World Vegetarian Congress Toronto, Canada, July 10 to 16, 2000.

- ^ a b Tobias, Michael (1995). A Vision of Nature: Traces of the Original World. Kent State University Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-87338-483-4.

- ^ Chapple, Christopher Key (2015). Yoga in Jainism. Routledge. pp. 199–200. ISBN 978-1-317-57218-3.

- ^ a b Battin, Margaret Pabst (2015). The Ethics of Suicide: Historical Sources. Oxford University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-19-513599-2.

- ^ Singha, H. S. (2000). The Encyclopedia of Sikhism (over 1000 Entries). Hemkunt Press. p. 22. ISBN 9788170103011.

- ^ a b Pruthi, Raj (2004). Sikhism and Indian Civilization. Discovery Publishing House. p. 55. ISBN 9788171418794.

- ^ Classen, Constance (1990). "Aesthetics and Asceticism in Inca Religion". Anthropologica. 32 (1): 101–106. doi:10.2307/25605560. JSTOR 25605560.

- ^ Baudin, Louis (1961). Daily Life of the Incas. Courier. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-486-42800-0.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Hyland, Sabine (2003). The Jesuit and the Incas: The Extraordinary Life of Padre Blas Valera, S.J. University of Michigan Press. pp. 164–165. ISBN 0-472-11353-4.

- ^ Eskildsen, Stephen (1998). Asceticism in Early Taoist Religion. State University of New York Press. pp. 24, 153. ISBN 978-0-7914-3956-2.

- ^ Pas, Julian F. (1998). Historical Dictionary of Taoism. Scarecrow. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-8108-6637-9.

- ^ Eskildsen, Stephen (1998). Asceticism in Early Taoist Religion. State University of New York Press. pp. 28–29, 93–101, 131–145. ISBN 978-0-7914-3956-2.

- ^ Admin, Purple Cloud (10 October 2019). "苦 Bitterness". Purple Cloud Institute.

- ^ Eskildsen, Stephen (1998). Asceticism in Early Taoist Religion. State University of New York Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-7914-3956-2.

- ^ W. R. Garrett (1992), The Ascetic Conundrum: The Confucian Ethic and Taoism in Chinese Culture, in William Swatos (ed.), Twentieth-Century World Religious Movements in Neo-Weberian Perspective, Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press ISBN 978-0773495500, pp. 21–30.

- ^ "Asceticism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 21, 2004.

In Zoroastrianism (founded by the Persian prophet Zoroaster, seventh century bc), there is officially no place for asceticism. In the Avesta, the sacred scriptures of Zoroastrianism, fasting and mortification are forbidden, but ascetics were not entirely absent even in Persia.

- ^ Weber, Max (1905). "The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism".

- ^ "Chapter 2". The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Translated by Parsons, Talcott. See translator's note on Weber's footnote 9 in chapter 2.

- ^ McClelland, David C. (1961). The Achieving Society. Free Press. ISBN 9780029205105.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ "Nietzsche, Genealogy of Morals: Third Essay, What Do Ascetic Ideals Mean?". 2013-12-21. Archived from the original on 2013-12-21. Retrieved 2021-09-07.

- ^ Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm (1887). The genealogy of morals. Robarts – University of Toronto. New York : Boni and Liveright.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ "Nietzsche Source – Home". www.nietzschesource.org. Retrieved 2021-09-07.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 – In Our Time, Nietzsche's Genealogy of Morality". BBC. Retrieved 2021-09-07.

- ^ Silk-Richardson, John (5 September 2021). "Nietzsche's Values". Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews. Retrieved 2021-09-07.

Sources

[edit]- Balcerowicz, Piotr (2015), Early Asceticism in India: Ājīvikism and Jainism, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-53853-0

- Cort, John E. (2001a), Jains in the World : Religious Values and Ideology in India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-513234-3

- Doniger, Wendy, ed. (1999), Encyclopedia of World Religions, Merriam-Webster, ISBN 0-87779-044-2

- Dundas, Paul (2002) [1992], The Jains (2nd ed.), London and New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26605-X

- Fujinaga, S. (2003), Qvarnström, Olle (ed.), Jainism and Early Buddhism: Essays in Honor of Padmanabh S. Jaini, Jain Publishing Company, ISBN 978-0-89581-956-7

- Jain, Vijay K. (2011), Acharya Umasvami's Tattvarthsutra (1st ed.), Uttarakhand: Vikalp Printers, ISBN 978-81-903639-2-1,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Sutton, Dr Nicholas (2017), Bhagavad Gita: The Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies Guide, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, ISBN 978-1-5030-5291-8

- Wiley, Kristi L. (2009) [1949], The A to Z of Jainism, vol. 38, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0-8108-6337-8

- Winternitz, Moriz (1993), History of Indian Literature: Buddhist & Jain Literature, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0265-0

Further reading

[edit]- Valantasis, Richard. The Making of the Self: Ancient and Modern Asceticism. James Clarke & Co (2008) ISBN 978-0-227-17281-0.

- von Glasenapp, Helmuth (1925), Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation, Delhi, India: Motilal Banarsidass (Reprinted 1999), ISBN 81-208-1376-6

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help).

External links

[edit]- Asketikos – articles, research, and discourse on asceticism.