Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Jewish Legion

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2024) |

| Jewish Legion | |

|---|---|

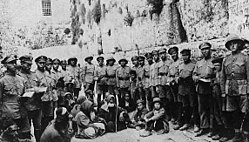

Jewish Legion soldiers in 1919 | |

| Active | 1917–1921 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Size | 5,000 Jewish troops |

| Engagements | |

The Jewish Legion was a series of battalions of Jewish soldiers who served in the British Army during the First World War. Some participated in the British conquest of Palestine from the Ottomans.

The formation of the battalions had several motives: the expulsion of the Ottomans, the gaining of military experience, and the hope that their contribution would favorably influence the support for a Jewish national home in the land when a new world order was established after the war. The idea for the battalions was proposed by Pinhas Rutenberg, Dov Ber Borochov and Ze'ev Jabotinsky and carried out by Jabotinsky and Joseph Trumpeldor, who aspired for the battalions to become the independent military force of the Yishuv in Palestine.

Their vision did not fully materialize, as the battalions were disbanded shortly after the war. However, their activities significantly contributed to the establishment of paramilitaries such as the Haganah and the Irgun (which later became the foundation for the Israel Defense Forces).

Formation and objectives

[edit]During the First World War, a debate emerged within the Zionist leadership on whether to support either side, the Entente Powers or the Central Powers, or to maintain neutrality and on the policy that would best ensure the survival of the Jewish community in Palestine during the war and benefit its aspirations for a national home afterward. The debate created a rift between those who supported the Entente Powers and those who supported the Central Powers. The Jews of German origin were patriotic to their country of origin, and the battalions were a British initiative against the Ottoman Empire, which was allied to Germany. Therefore, the "German" Jews opposed the battalions vehemently, and Chaim Weizmann yielded to them by opposing the battalions mainly because the one protecting the Yishuv in Palestine was a German general. There was also the real fear that the Ottomans would carry out a massacre if they decided that the Jews were a fifth column, as had occurred to the Armenians.

Pinhas Rutenberg was a member of the Socialist Revolutionary Party (SR), which, unlike the Bolsheviks, supported the Russians' alliance with Britain. David Ben-Gurion and Yitzhak Ben-Zvi supported the Ottomans and opposed the battalions. What changed their minds completely was the Balfour Declaration, and they later enlisted in the battalion.

First World War and establishment of battalions

[edit]

During the period leading up to the outbreak of the war in 1914, revolutionaries were waiting for a revolution in Russia. The Okhrana was successful in its activities against the revolutionaries, and SR activists went into exile from Russia. Vladimir Lenin and his colleagues also established the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, which competed with the SR in exile. When the war broke out, a meeting was held among the SR exiles' leadership, which was divided between the left and the right. Supporters of Ilya Fondaminsky argued that the war would shake the tsarist regime and therefore should enlist and aid the British to hasten the revolution. There was also an opposing trend led by Viktor Chernov, a rival to Rutenberg, who opposed that approach.

Rutenberg went to London, met with Chaim Weizmann and tried to convince him to support the establishment of the Jewish battalions. Rutenberg told Weizmann that the war was an opportunity to advance the idea of a republic in Israel. To convince the Entente Powers, Jewish legions of Jewish exiles needed to be established. According to Professor Matityahu Mintz, Rutenberg preceded Ze'ev Jabotinsky. Rutenberg acted in September 1914, and Jabotinsky began in 1915.

The question arises as to what motivated Rutenberg, who was traveling on behalf of the SR to the British and French capitals to pressure Russia for greater democratisation, engage with the Jewish people and meet Weizmann. Mintz clarifies that for Rutenberg, they were not separate domains. Before his trip, Rutenberg had not spoken about or sought a solution to the Jewish question, but that was a result of Rutenberg's discussions with the SR leadership, who sent him to France. Mintz does not believe that Rutenberg's return to the Jewish people was insincere but emphasises the alignment between his conduct and the interests of the party and of Russia. The evidence for maintaining ties and prioritising the party's interests was Rutenberg's rapid and smooth integration into the government leadership after the February Revolution of 1917, during Alexander Kerensky's Social Revolutionary administration.

The SR, as well as the Constitutional Democrats, thought that the number of Jews in Russia was too large and that it would be better if they left Russia before the revolution, which would be beneficial for the Jews as well. The SR was aware of the Jews' animosity toward the autocratic regime in Russia, alongside the growing Jewish sympathy for Germany, which had granted them freedom and rights. Rutenberg adopted that SR stance. The idea of battalions that would conquer the land from the Ottomans, who were German allies, served the interests of the Russian homeland, allied to France and Britain.

Mintz noted that the Zionist movement decided on neutrality, but in practice, that was not the case, as Zionists in each country supported their homeland. For instance, German Zionists believed that if Germany won the war, the Jews' situation would improve, as their status in Russia was worse than in Germany.

Rutenberg then went to Italy and established an organization for the Jewish cause. The basic idea was that if Italy joined the war on the side of the Entente Powers, the first Jewish battalions would be formed in Italy. Dov Ber Borochov also arrived in Italy from Vienna after the Austrian police made it clear that it would be better for him to leave Austria-Hungary, an ally of Germany. In Milan, Rutenberg and Borochov met after David Goldstein, a member of Poale Zion, connected them. Borochov joined Rutenberg and was active in leading this organization. He managed to organize not only Jews but also intellectuals, politicians, and Italian ministers like Luigi Luzzatti. In 1915, they joined, but Rutenberg decided to go to the United States. He had travelled to Bari, Italy, and invited Jabotinsky, Ben-Gurion and Ben-Zvi to present the plan. Ben-Gurion and Ben-Zvi refused to come, and only Jabotinsky met with Rutenberg before Jabotinsky's trip to London. Rutenberg and Jabotinsky divided the work. Rutenberg would work in the United States and Jabotinsky in Britain, as Rutenberg aimed to establish a non-Zionist Jewish Congress in the US.

According to Mintz, Rutenberg brought a booklet and manifesto to the US, began participating in conferences, organized a committee and started a newspaper for the Jewish Congress. Borochov was the editor of the newspaper and also wrote the articles. A conflict broke out between Rutenberg and Ben-Gurion, who was also in the US, as Ben-Gurion continued to support a pro-Ottoman orientation. Ben-Zvi joined Ben-Gurion although Mintz notes that their relationship soured in the US because Ben-Gurion published a book in which he attributed all of the work to himself. According to Mintz, there is no doubt that Ben-Gurion downplayed Ben-Zvi's contributions. There was no conflict between Ben-Zvi and Borochov, as Ben-Zvi was from Borochov's hometown, his student, and a close friend, and they respected each other.

Jabotinsky

[edit]One of the most prominent figures supporting the activist line was Jabotinsky, who knew the Ottoman Empire and so predicted that its days were numbered during the war, which would impact the future governance of Palestine. He argued that the Jews should openly support Britain and help its military efforts to capture the Land of Israel.

In 1915, Jabotinsky arrived at Camp Jabari, near Alexandria, where 1,200 Jews who had been expelled from Palestine by the Ottomans or fled by the harsh living conditions gradually gathered, along with Joseph Trumpeldor. Jabotinsky presented his ideas for establishing a Jewish military unit. On 18 Adar 5675 (February 18, 1915), a document was drafted stating the decision to establish a Jewish battalion and offering its services to the British Army for the conquest of Palestine. The document bore 100 signatures, with the first being those of Ze'ev Gluskin, Jabotinsky, and Trumpeldor. Subsequently, they began negotiations with various elements within the British army and government.

Opposition to establishment of the battalions

[edit]After numerous negotiations, the British partially agreed to the initiative, and a Jewish unit was formed with volunteers from the exiles in Egypt. Its purpose was set as a transport unit on the Gallipoli front, in Turkey. The means of transport of that time gave the unit its name: the "Zion Mule Corps". However, its activities were not connected to Palestine, as Britain did not yet plan to attack there.

Several bodies and groups opposed the establishment of the battalions, and some actively tried to stop their formation:

- Anti-Zionist or non-Zionist Jews, particularly assimilated British Jews who feared that emphasizing Jewish nationality through the battalions would harm their status among the British.

- The leadership of the Zionist Organization, including figures like Nahum Sokolow and others in London, who aimed to maintain neutrality.

- Ahad Ha'am and others who saw the main role of Zionism in spiritual activity.

- Part of the labor camp in Palestine, especially members of Hapoel Hatzair, believed that the land should be acquired through labour, not war, and therefore opposed the establishment of the battalions and joining them.

Zion Mule Corps

[edit]The Zion Mule Corps preceded the combat Jewish battalions formed later. Its recruits were Jews who had been exiled to Egypt by the Ottoman Empire. It was established in the spring of 1915 and was responsible for transporting supplies to the front lines during the Gallipoli campaign, in Turkey. The unit was praised for its performance. After the failed campaign, the British refused to transfer it to another front. The corps was disbanded, and some of its members joined the subsequent Jewish battalions.

Jewish Legion

[edit]

Unlike Trumpeldor, Jabotinsky was not satisfied with the formation of the Zion Mule Corps, which was not a combat unit and did not participate in the fight against the Ottomans. He traveled to Europe to continue advocating for the battalions. Jabotinsky contacted numerous statesmen but failed to gain genuine support for his initiative in Britain, France and Russia. The resistance stemmed from both a lack of trust in a military unit composed entirely of Jewish volunteers and the times's lack of interest in fighting the Ottomans in Palestine. Also, significant support did not come from most Jewish leaders or communities. However, a few Zionist figures tried to assist Jabotinsky. The most notable was Meir Grossman with whom he founded the newspaper Di Tribune, later known as Unser Tribune, to promote propaganda for the battalions. Rutenberg and Weizmann also supported Jabotinsky's initiative, but the Zionist Organization strongly opposed it, and its executive committee issued an order to all Zionists in Europe to fight against the propaganda supporting the Jewish Legion.

Jabotinsky eventually reached London and focused his efforts there for the next two years. He decided to concentrate on around 30,000 Jews, mostly young men who were refugees from Russia, Poland and Galicia who resided as refugees in London, particularly in Whitechapel and the rest of the East End of London. The efforts to form the battalion were highly determined and carried out against the odds: Horatio Kitchener, the British Secretary of War, believed that Britain did not need "exotic armies" and that the war would not reach Palestine. Most Zionist movement leaders, as mentioned earlier, tried to thwart the initiative, and above all, there was great apathy among young London Jews, most of whom saw no need to enlist in the British Army, did not identify with its war and did not identify with Zionism or the idea of conquering Palestine.

Nevertheless, voices in Britain began to grow in favor of compulsory enlistment. The British people witnessed the heavy losses in the youth on the battlefields compared to the "café dwellers", many of whom were European refugees in London, including young Jews. The British Home Office later ordered compulsory enlistment for British citizens. The foreign Jews initially refused enlistment. Jabotinsky and his supporters clarified to the British authorities and to the young Jews that joining a Jewish battalion was the only way out of the predicament. Two catalysts then appeared: an editorial supporting the idea in the influential newspaper The Times and a group of 120 former members of the Zion Mule Corps, along with Trumpeldor, who joined the 20th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers and formed a Jewish company within it. After a decisive meeting between Trumpeldor, Jabotinsky and senior officials at the War Office, the formation of a combat Jewish battalion was realized.

Initially, the battalion was called "The Jewish Regiment" (a regiment usually consisting of two battalions), and its symbol was a menorah with the slogan "Kadima," meaning "forward" as both "advance" and "eastward". It recommended John Henry Patterson as its commander, as he had led the Zion Mule Corps throughout its operations in Gallipoli. Trumpeldor, who had served as the deputy commander of the Mule Corps in Gallipoli and succeeded Patterson in its final months, was initially denied an officer's commission by the British and so he returned to Russia to promote his idea of forming a massive Jewish army to fight on the Caucasus front and advance toward Palestine. The Jewish company of the 20th Battalion joined the new Jewish battalion, and its members became the core of the unit.

The 38th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers

[edit]

The 38th (Service) Battalion, Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment), commonly referred to as the "London Battalion", was mainly composed of Jews from London, with a smaller number of Americans. The battalion, led by Patterson because of his success with the Zion Mule Corps, had two thirds of its officers as Jews; other battalions had mostly Christian officers. Recruitment for the battalion took place in England.

In August 1917, two official notices were issued: one obligating Russian citizens residing in England to enlist in the army and the other announcing the establishment of the Jewish battalion. Despite obstacles, the assimilated Jews in London continued to oppose its existence and tried to dissolve it. Although they failed in their efforts, their influence led to the cancellation of the name "The Jewish Regiment" and the menorah symbol. Instead, it was given the name of a regular British battalion—the 38th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers. The War Minister promised, however, that the battalion would regain its symbols after proving itself in combat. The public and the press still referred to it by its original name, the recruitment office displayed Hebrew signs, and the soldiers and officers wore Star of David insignias on their left arm (the 38th Battalion had a light purple Star of David, the 39th was red and the 40th was blue). The soldiers trained at a camp near Portsmouth.

On 2 February 1918, the Jewish battalion marched through the main streets of Whitechapel and the rest of London. Great excitement was felt among the city's Jews, many shops hung blue and white flags and the proud soldiers of the legion were received with loud cheers in the streets. The next day, the battalion set off for France and then through Italy to Egypt.

The 38th Battalion trained in Egypt and was later sent to Palestine. There were already many volunteers from among the local youths, who would later form the 40th Battalion. In early June, the battalion was stationed on the front lines of the British forces in the hills of Ephraim, an area in which the British forces were engaged in skirmishes against the Ottomans. Malaria was an issue, which afflicted many.

In mid-August, the battalion was sent to the Jordan front, where it served as a link throughout the British front. In September, at the beginning of the Battle of Megiddo, Patterson received orders to capture the Umm al-Shert Bridge in the Jordan Valley, the only bridge in the area (located directly east of Netiv HaGdud, a moshav named after the operation). The first company sent to the location came under fire; its captain, Julian, was barely rescued; the lieutenant was wounded and taken prisoner; and a private was killed. Jabotinsky then led the second company to seize the site, and the mission was successfully completed on the 22nd of the month.

From there, the battalion, already preceded by the 39th Battalion, advanced to the area of As-Salt, east of the Jordan River, and established a garrison there. In Gilead, the British completed their conquest of Palestine, and the battalion returned to its western side and took Ottoman and German prisoners. Subsequently, the battalion was tasked with guarding military facilities.

The 39th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers

[edit]

The 39th Battalion was known as "the American Battalion," since most of its soldiers coming from the Jewish community in the United States, but had a minority from England. The origins of its formation lie in Rutenberg's 1915 initiative to create a military unit composed of American and Canadian Jews. Initially, American Jews did not agree to his initiative, but when the United States entered the war in April 1917, their stance changed. The battalion was recruited in the United States.

The principal initiators of its establishment were Ben-Zvi and Ben-Gurion, who were exiled from Palestine during the war by Djemal Pasha. They changed their position after the Balfour Declaration. About 5,000 volunteers (though not all managed to arrive in Palestine) formed the battalion, which operated under British command. The battalion's commander was Colonel Eliezer Margolin. It included a core group of members from the "HaHalutz" (The Pioneer) movement and "Poalei Zion," meaning, unlike the 38th British Battalion, most of its members were Zionists. In 1918, the battalion's soldiers were sent to Palestine, where the 38th Battalion had also arrived.

About half of its members participated in the military campaigns in the Jordan Valley and Samaria while the 38th Battalion was also present there. After the capture of the Umm-Shert Bridge, half of the battalion moved to the area of Jericho and then to Gilead to complete the British conquest of Palestine. Some members of the battalion arrived in the land only after the end of the war.

The 40th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers

[edit]

The 40th Battalion, known as the "Palestinian Battalion" of the Jewish Legion, had as its primary mission to perform guard and security duties. It was formed after the British forces entered Palestine, and many local youths wanted to participate in the Jewish military effort. Even before the 38th Battalion's arrival, there were already 1,500 youths prepared to volunteer, one third of whom were women, though the women were not enlisted. The desire of the local Palestinian Jewish youth to enlist met the initiative of Major General John Hill, the commander of the 52nd Division, who called on the young men of the Yishuv in areas that had beenconquered by the British to join the army and to assist in further conquests of the land. Most of the volunteers were young "activists" from the labor camp, members of the Jaffa Group and the Small Assembly, as well as secondary school students from Herzliya Hebrew Gymnasium, who campaigned vigorously for recruitment. Their initiative met resistance, and a debate arose within the Jewish Yishuv regarding enlistment.

The decision was made at the First Constituent Assembly on 2 January 1918, following a discussion in which the leadership of Poalei Zion supported enlistment and volunteering. Moshe Smilansky and Eliyahu Golomb argued that joining the Jewish Battalions was a political endeavor that elevated the status of the Yishuv in the eyes of its new rulers and contributed to the strength of the community.

Members of the HaPoel HaTzair, including Yosef Sprinzak and A.D. Gordon, were the main opponents. The party argued that the Yishuv's efforts should focus on settlement and agriculture, alongside its pacifist ideology that opposed participation in imperialist and bloody wars. Another argument was the fear of harm to the settlers of the Galilee, who were still under Ottoman rule. Despite the opposition from the leadership of HaPoel HaTzair, the movement had volunteers who joined the battalion.

In parallel with the enlistment campaign conducted in Tel Aviv, which resulted in one company of volunteers, Baron James de Rothschild led a recruitment campaign in Jerusalem, which produced a second company of recruits. The volunteers from Jerusalem included some students from the teacher's seminary and mostly members of the old Yishuv, who enlisted with the blessing of the rabbis.

General Edmund Allenby was initially reluctant to the idea of a unit of Jewish soldiers under his command, but Zionist political activity in London led to its establishment, and 1,000 volunteers were accepted into its ranks. Smilansky, who also enlisted, spearheaded the recruitment campaign. The battalion was formed in Palestine. Among the enlistees were Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, David Ben-Gurion, and Berl Katznelson, who were already public leaders in the Yishuv but served as privates in the battalion. The 40th Battalion completed its initial training near Tel El-Kebir, Egypt, under the command of Colonel Margolin. After Margolin was appointed to command the 39th Battalion, Colonel Frederick Samuel, a member of an assimilated English-Jewish family who had served as a battalion commander on the French front, took command. He expected a promotion to brigadier but upon receiving a letter stating that Jewish officers were needed for the Jewish Legion, he left his unit, forwent the brigadier position and joined the 40th Battalion.

After him, the battalion was commanded by Colonel M.P. Scott, who was a Christian. The battalion did not participate in battles, and its soldiers served in support roles for the British Army and guarded prisoners. In December 1918, the battalion was moved to the Sarafand (now Tzrifin) area, and some of its soldiers, those who found work, were released from service. By the end of 1919, part of the battalion was stationed at Rafah and received an order to send 80 of its soldiers to the Egyptian headquarters. As that was against the "agreement", its soldiers refused to comply. Scott supported their stance and excused them from the order. After his service, Scott remained a supporter of Zionism and was quoted as saying: "England has been honored: We tore a page from the Bible inscribed with the oldest prophecy—adding England's pledge to the promissory note of God. Such a signature cannot be renounced by the nation".

The composition of the three battalions by country of origin was estimated as follows: 1,700 Americans, 1,500 Palestinian Jews, 1,400 British, 300 Canadians, 50 Argentinians and about 50 Jewish prisoners released from Ottoman captivity.

"First Judean"

[edit]

In the first year after the conquest of Palestine (1919), the battalions comprised a significant portion of the British forces maintaining order in the land. In the Autumn Offensive of Allenby 1918, only "a battalion and a half" participated, but a year later, the battalions numbered 5,000 soldiers (actually, according to British War Office records, 10,000 men were accepted into the battalions, but half did not reach Palestine because the war had already ended). The presence of the battalions in Palestine moderated the Arab population's attitude toward the Yishuv. For two months, uprisings broke out in Egypt, and the sense of Arab national awakening also reached Palestine, but it did not ignite significant actions.

After the war ended, the morale of the soldiers in the legion declined, and most of the British and American soldiers wanted to return to their home countries. The British military administration in Palestine did not align with the pro-Zionist sentiments of London and sought to disband the battalions, which they saw as potentially igniting conflict with the local Arabs.

| Battalion | Fatalities |

|---|---|

| 38th | 43 |

| 39th | 23 |

| 40th | 12 |

| 42nd | 3 |

| 38th/40th | 9 |

| Transferred from Jewish Legion |

1 |

By spring 1920, the first two battalions were already disbanded, and the remnants of their soldiers joined the Palestinian battalion, now under Margolin's command. The War Minister's promise was fulfilled, and the battalion was renamed the "First Judean". Its symbol was the menorah, and its motto was "Kadima". It was the first military body to have all of its symbols in Hebrew. The Palestinian volunteers attempted to remain despite the demobilisation orders, which were strongly enforced by the military command. Many were torn between military service and labour, but some managed to extend their service by several months. Gradually, only 400 soldiers remained. Herbert Samuel planned to establish a "mixed militia" of Jews and Arabs, and some of the legion's soldiers and veterans joined its Jewish section.

During the 1921 Palestine riots, on Margolin's initiative, several dozen armed soldiers of the battalion arrived in Jaffa and Tel Aviv and participated in defending the area from Arab rioters. Among other actions, they prevented Arabs from breaking into the Jewish compound of Batay Varsha (Jaffa). Their intervention in the pogrom led to the end of their service and closed the chapter on the planned "militia".

After disbandment of "First Judean"

[edit]

The "First Judean" battalion was disbanded by the British in May 1921. The disbandment of the battalions thwarted Jabotinsky's vision of establishing an official Jewish army and led the Yishuv to establish a clandestine armed force, the Haganah, which, as its name suggested, was primarily defensive. The disbandment of the "First Judean" battalion marked a British policy against an independent Jewish defense force in the Yishuv in response to Arab aggression.

Palestine Defense Force

[edit]At the time of the disbandment of the Jewish Battalions, a plan was proposed to establish a militia called the "Palestine Defense Force" or "Defense Corps of Palestine" (various translations of the English term). To establish this guard force, a number of officers and about 30 sergeants were retained in the army, intended to be the command staff of the first battalion of the future guard force.

However, after the riots in May 1921 in which the sergeants left their base without permission to assist Jewish defence forces, Margolin, the commander, decided to resign, and the military authorities dismissed all personnel and cancelled the plan to establish the guard. Some of the dismissed soldiers later became instructors and commanders in the newly-formed Haganah.

Legacy

[edit]

Even though the battalions' contribution to the campaign was limited, their existence was significant as the first Jewish military force of the modern era. It was an open non-clandestine force bearing Jewish symbols, and its language was Hebrew. The existence of the battalions provided proof of the possible strength of the Jewish people and gave moral and ethical justification for the demand to establish a Jewish national entity in Palestine. The military experience that was gained within the battalions, as well as the spirit of volunteerism, was later transferred to defensive frameworks like the Tel Aviv Keda Group, most of whose members had been battalion members, and later also into the underground movements operating in the land.

In his book "The Legion Scroll", Jabotinsky wrote:

The moral value of the battalion is clear to anyone capable of honest and fair thinking. War is a terrible thing—a sacrifice of human lives. But today, no one can accuse us: Where were you? Why didn't you demand: Let us, as Jews, give our lives for Eretz Yisrael? – Now we have an answer: Five thousand; and there could have been many more had your leaders not delayed our matter for two and a half years. This moral aspect is invaluable; and this is what the Prime Minister of South Africa—a great lover of peace himself—meant when he said: Letting Jews fight for the land of Israel is one of the most beautiful ideas I have ever heard in my life.

To the members of his battalion who were about to return to their homes overseas, he said:

You will return to your family far across the sea; and there, as you browse the newspaper, you will read good news about the freedom of Jews in a free Jewish land—about workshops and cathedrals, about plowed fields and theaters, and perhaps also about members of parliament and ministers. And you will be lost in thought, and the newspaper will slip from your hand; and you will remember the Jordan Valley, and the desert behind Rafah, and the hills above Aboein. Stand up then, approach the mirror, and look with pride upon yourself, stand tall and salute: This is—your very own handiwork.

The enlistment, service and experience of military life in the battalions are described in the song "Aryeh, Aryeh".

The Menorah Club[2] was a club for veterans of the Jewish Battalions and was established in Jerusalem in 1923. Initially located on Jaffa Street, it moved near the Bezalel Academy in 1929.[3][4] Various gatherings, parties and events were held at the club.[5][6] "Beit HaGdudim" is a museum commemorating their work.[7] It is located in Avihayil, a moshav founded by battalion veterans. It was also decided to move Patterson's ashes there.

The Jewish Legion Memorial Park is near the beginning of the trail in the Shiloh Stream. The Jewish battalions are also commemorated at the Memorial for the Jewish Volunteers in the British Army during the World Wars.

Gallery

[edit]-

Zion Mule Corps Ammunition Company in Egypt 1915

-

Colonel Eliezer Margolin of the "First Judeans".

-

Private Morris Ziggles of the 39th Battalion and his daughter Stella, 1917.

-

Lt. Ze'ev Jabotinsky MBE in uniform of 38th RF (centre seated).

-

Jewish Legion standard 1 January 1918

-

39th Battalion, Jewish Legion, at Fort Edward (Nova Scotia), Yom Kippur, 1918.

-

Officers of 39th Royal Fusiliers (Jewish), Helmieh Camp, Cairo, August 1918.

-

Col. Margolin leading the 39th Battalion of the Jewish Legion through Bet Shemen.

-

Jewish Legion camped at what would become Shilo, Mateh Binyamin

-

Jewish Legion Soldiers at El Arish Egypt 1918

-

Gershon Agron in his Jewish Legionnaire uniform, 1918

-

Private Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, a volunteer in the Jewish Legion 1918.

-

Shimon Kushner in the uniform of the Hebrew Battalion 1918

-

Yaakov Dori

-

Private Jacob Epstein

-

The Jewish Legion celebrates Passover 1919.

-

Judea Liberated postcard. At the lower right is a Jewish Legion soldier.

-

1940 Poster featuring Jabotinsky of the Jewish Legion. For contributions to Keren Hayesod.

-

Jewish Legion Veterans March in Jerusalem in protest against the "Palestine White Paper" restricting Jewish Immigration 18 May 1939

-

Veterans of the Jewish Legion, 27 September 1942, Tel Aviv.

Notable members

[edit]

- John Henry Patterson, Commander of Zion Mule Corps and 38th Battalion Royal Fusiliers

- Eliezer Margolin, Commander of the 39th Battalion Royal Fusiliers and the First Judaeans

- Gershon Agron, Mayor of Jerusalem

- Nathan Ausubel, Jewish American author

- Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, second Israeli President

- Yaakov Dori, Haganah leader; first Chief of Staff of the Israel Defense Forces, President of the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology

- Maxwell H. Dubin, rabbi, Wilshire Boulevard Temple, Los Angeles

- Sir Jacob Epstein, British sculptor

- Levi Eshkol, third Prime Minister of Israel

- Louis Fischer, Jewish-American journalist and author

- Eliyahu Golomb, founding member of the Haganah

- David Grün, later Ben-Gurion, first Israeli Prime Minister

- Nachum Gutman, Israeli painter

- Dov Hoz, Zionist activist, Haganah fighter

- Julius Jacobs, brother-in-law of Moshe Smilansky; killed in the King David Hotel bombing, 22 July 1946

- Bernard Joseph, later Dov Yosef, Governor of Jewish Jerusalem during the 1948 siege; longtime Labor MK

- Berl Katznelson, Zionist philosopher and activist

- Reuven Katzenelson, Sergeant under Joseph Trumpeldor at Battle of Gallipoli and father of Shmuel Tamir

- Bert "Yank" Levy, Internationalist in Spain and military instructor for the British Home Guard. His work served as the basis for a popular handbook on guerrilla warfare.[8]

- Gideon Mer,[9] physician, veteran of Zion Mule Corps, Jewish Legion and British Army in the Second World War. Served as a medic in the 1947–1949 Palestine war; later worked in the Israeli Ministry of Health. (Note: he is the unnamed officer in charge of an anti-malaria programme during the Second World War – mentioned in Martin Sugarman's article[10] on the Zion Mule Corps.)

- Nehemiah Rubitzov, father of Yitzhak Rabin

- Israel Rosenberg, also known as 'The grandfather of the Jewish Legion'[11]

- Ben Rosenthal, California State Assemblyman

- James Armand de Rothschild, DCM Major, 39th Royal Fusiliers Battalion; Captain Royal Canadian Dragoons; a member of the Rothschild family

- Redcliffe N. Salaman, medical officer, from April 1918 in Egypt and Palestine, 38th Battalion, then 39th of Royal Fusiliers

- Edwin Herbert Samuel, 2nd Viscount Samuel; CMG son of Herbert Samuel, 1st Viscount Samuel

- Moshe Smilansky, pioneer of the First Aliyah, a Zionist leader who advocated peaceful coexistence with the Arabs in Mandatory Palestine, a farmer, and a prolific author

- Edward Sperling, humourist and later director-general of the Ministry of Trade and Industry under the British Mandate of Palestine; killed in the 1946 King David Hotel bombing

- Eleazar Sukenik, Israeli archaeologist; father of Yigael Yadin

- David Tidhar, Police officer, private investigator and author

Further reading

[edit]- The Jewish Battalions in World War I: Documents and Records, Tel Aviv: Jabotinsky Institute, 1968.

- Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, The Jewish Battalions – Letters, Jerusalem: Ben-Zvi Institute, 1968.

- Rafael Doron (Boyanovsky), Legionnaires from Argentina: Volunteers in the Jewish Battalion in World War I – Life Chapters, Edited by Dvora Schechner, Afterword by Muki Tzur, Yad Yaari, Givat Haviva, 2007.

- Avraham Yaari, Memories of Eretz Yisrael, Volume II, Zionist Organization; Tel Aviv: Masada Press, 1947, pp. 1104–1133:

- Chapter 103, In the Jewish Volunteer Battalion in America, Yafat Yudilovich, 1918

- Chapter 104, Establishing the Palestinian Jewish Battalion, Moshe Smilansky, 1918

- Chapter 105, The Life of a Soldier in the Palestinian Jewish Battalion, Shimon Kushnir, 1918–1920

- Chapter 106, Passover in the Jewish Battalion in Beit Shean, Shmuel Bas, 1920

- John Patterson, With the Jewish Battalions in Eretz Yisrael (translated from English: Chaya Wali), Introduction by Ze'ev Jabotinsky, Jerusalem: Mitzpeh Publishing, Jerusalem - Tel Aviv, 1929.

- Yigal Eilam, The Jewish Battalions in World War I, Ministry of Defense Publishing, Tel Aviv, 1973.

- Ze'ev Jabotinsky, The Legion Scroll: The Story of the Jewish Battalions in World War I (revised edition), Tel Aviv: Ministry of Defense Publishing, 1991 (= Ze'ev Jabotinsky (posthumously), Autobiography (in the series of writings), published by Ari Jabotinsky, Jerusalem, 1947).

- Michael Keren and Shlomit Keren, We Are Coming, Unafraid: The Jewish Legions and the Promised Land in the First World War, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2010.

- Moshe Beller, Ze'ev Jabotinsky in His Ideological Struggle for the Jewish Battalions (On the 60th Anniversary of Their Establishment), Hauma, XV (51–52), 1977, pp. 417–427.

- Arnon Lamperom, "Yitzhak Ben-Zvi and the Commemoration of Yosef Benyamin: A Failed Attempt to Establish a Heritage Site," Archive 17, Winter 2013, pp. 48–55. See the article online in Archive 17.

- Rachel Silko, An Ephemeral Episode or the Beginning of a Military Tradition? The Military Aspect in the Families of the Jewish Legion Soldiers, The Chain of Generations Volume XXI, No. 3, August 2007, pp. 22–26.

- Shlomit Keren, The Jewish Battalions in World War I as a Source of Military Culture in Israel, National Security 5, 2007, pp. 93–109.

- Ofer Regev Book Review on John Patterson

- Patterson, John H. With the Judaeans in the Palestine campaign. Uckfield : Naval & Military Press, [2004 reprint] ISBN 978-1-84342-829-9

- Jabotinsky, Vladimir. The story of the Jewish Legion. New York: Bernard Ackerman, 1945. OCLC 177504

- Freulich, Roman. Soldiers in Judea: Stories and vignettes of the Jewish Legion. Herzl Press, 1965. OCLC 3382262

- Gilner, Elias. Fighting dreamers; a history of the Jewish Legion in World War One,: With a glimpse at other Jewish fighting groups of the period. 1968. OCLC 431968

- Gilner, Elias. War and Hope. A History of the Jewish Legion. New York; Herzl Press: 1969. OCLC 59592

- Keren, Michael and Shlomit Keren, We Are Coming, Unafraid: The Jewish Legions and the Promised Land in the First World War. Lanham MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2010. ISBN 978-1-4422-0550-5 OCLC 700447107

- Kraines, Oscar. The soldiers of Zion: The Jewish Legion, 1915–1921. 1985. OCLC 13115081

- Lammfromm, Arnon, "Izhak Ben-Zvi and the Commemoration of Joseph Binyamini: A Failed Attempt to Create a Site of National Heritage", Archion, 17, Winter 2013, pages 48–55, 68 (Hebrew and English abstract)

- Marrion, R.J. "The Jewish Legion," 39th (service) Battalion, Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment), 1918–1919. 1987.

- Watts, Martin. The Jewish Legion and the First World War. 2004. ISBN 978-1-4039-3921-0

- "When the spirit of Judah Maccabee hovered over Whitechapel Road and – The march of the 38th Royal Fusiliers" by Martin Sugarman, Western Front Association Journal, Jan 2010.

Sources

[edit]- Aspinall-Oglander, C. F. (1929). Military Operations Gallipoli: Inception of the Campaign to May 1915. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (1st ed.). London: Heinemann. OCLC 464479053.

- Alexander, H. M. (1917). On Two Fronts: Being the Adventures of an Indian Mule Corps in France and Gallipoli. London: Heinemann. OCLC 12034903.

- Patterson, J. H. (1916). With the Zionists in Gallipoli. London: Hutchinson. OCLC 466253048.

References

[edit]- ^ Approximate numbers, according to Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

- ^ Various photographs, posters and documents related to the Menorah Club are available in the National Library of Israel collections.

- ^ See the map of Jerusalem by Ze'ev Vilnai, published by Steimatzky in 1935, with the club’s location marked. Viewing is possible from the National Library building.

- ^ Dr. Eyal Davidson, "Menorah Garden: The Evolution of a Jerusalem Pit," Dr. Eyal Davidson's site.

- ^ Photos by Tzvi Oron documenting the Menorah Club.

- ^ Reuven Gefen, "The Menorah Club in Jerusalem," Zionist Archives.

- ^ The museum's page on the Ministry of Defense (Israel) site.

- ^ Levy, Bert "Yank"; Wintringham, Tom (Foreword) (1964) [1942]. Guerilla Warfare (PDF). Paladin Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ "Mer, Professor Gideon". Israel War Veterans League. Archived from the original on 25 December 2007. Retrieved 12 March 2008.

- ^ The Zion Muleteers of Gallipoli (March 1915 – May 1916) article. Retrieved 11 November 2018

- ^ "מכון ז'בוטינסקי | Item". en.jabotinsky.org.

External links

[edit]See also

[edit]- Jewish Brigade, a similar military formation of volunteer Jews in the British Army that fought in the Second World War

- Jewish Legion (Anders Army), a proposed unit in the Polish Anders Army in USSR during the Second World War

- Tilhas Tizig Gesheften, organisation which grew out of the Jewish Brigade