Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

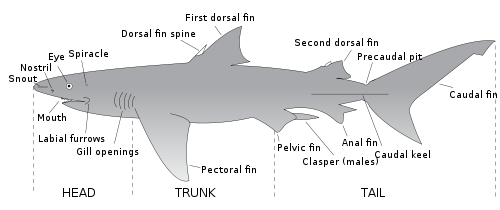

Fish fin

View on Wikipedia

(1) pectoral fins (paired), (2) pelvic fins (paired), (3) dorsal fin,

(4) adipose fin, (5) anal fin, (6) caudal (tail) fin

Fins are moving appendages protruding from the body of fish that interact with water to generate thrust and lift, which help the fish swim. Apart from the tail or caudal fin, fish fins have no direct articulations with the axial skeleton and are attached to the core only via muscles and ligaments.

Fish fins are distinctive anatomical features with varying internal structures among different clades: in ray-finned fish (Actinopterygii), fins are mainly composed of spreading bony spines or "rays" covered by a thin stretch of scaleless skin, resembling a folding fan; in lobe-finned fish (Sarcopterygii) such as coelacanths and lungfish, fins are short rays based around a muscular central bud internally supported by a jointed appendicular skeleton; in cartilaginous fish (Chondrichthyes) and jawless fish (Agnatha), fins are fleshy "flippers" supported by a cartilaginous skeleton. The limbs of tetrapods, a mostly terrestrial clade evolved from freshwater lobe-finned fish, are homologous to the pectoral and pelvic fins of all jawed fish.

Fins at different locations of the fish body serve different functions, and are divided into two groups: the midsagittal unpaired fins and the more laterally located paired fins. Unpaired fins are predominantly associated with generating linear acceleration via oscillating propulsion, as well as providing directional stability; while paired fins are used for generating paddling acceleration, deceleration, and differential thrust or lift for turning, surfacing or diving and rolling. Fins can also be used for other locomotions other than swimming, for example, flying fish use pectoral fins for gliding flight above water surface, and frogfish and many amphibious fishes (e.g. mudskippers) use pectoral and/or pelvic fins for crawling. Fins can also be used for other purposes: remoras and gobies have evolved sucker-like dorsal and pelvic fins for attaching to surfaces and "hitchhiking"; male sharks and mosquitofish use modified pelvic fins known as claspers to deliver semen during mating; thresher sharks use their caudal fin to whip and stun prey; reef stonefish have spines in their dorsal fins that inject venom as an anti-predator defense; anglerfish use the first spine of their dorsal fin like a fishing rod to lure prey; and triggerfish avoid predators by squeezing into coral crevices and using spines in their fins to anchor themselves in place.

Types of fins

[edit]Fins can either be paired or unpaired. The pectoral and pelvic fins are paired, whereas the dorsal, anal and caudal fins are unpaired and situated along the midline of the body. For every type of fin, there are a number of fish species in which this particular fin has been lost during evolution (e.g. pelvic fins in †Bobasatrania, caudal fin in ocean sunfish). In some clades, additional unpaired fins were acquired during evolution (e.g. additional dorsal fins, adipose fin). In some †Acanthodii ("spiny sharks"), one or more pairs of "intermediate" or "prepelvic" spines are present between the pectoral and pelvic fins, but these are not associated with fins.

| Pectoral fins (Arm fins) |

|

The paired pectoral fins are located on each side, usually kept folded just behind the operculum, and are homologous to the forelimbs of quadrupedal tetrapods or the upper limbs of bipedal tetrapods.

|

|---|---|---|

| Pelvic / Ventral fins (Belly fins) |

|

The paired pelvic or ventral fins are the belly fins (from Latin venter 'belly') are typically located ventrally below and behind the pectoral fins, although in many fish families they may be positioned in front of the pectoral fins (e.g. cods). They are homologous to the hindlimbs of quadrupedal tetrapods or the lower limbs of bipedal tetrapods.

The pelvic fin assists the fish in going up or down through the water, turning sharply, and stopping quickly.

|

| Dorsal fin (Spinal fins) |

Dorsal fin of a shark

|

The dorsal fins are located on the back. A fish can have up to three dorsal fins. The dorsal fins serve to protect the fish against rolling, and assist it in sudden turns and stops.

|

| Anal/cloacal fin |

|

The anal/cloacal fin is located on the ventral surface behind the anus/cloaca.

|

| Adipose fin |  Adipose fin of a trout

|

The adipose fin is a soft, fleshy fin found on the back behind the dorsal fin and just forward of the caudal fin. It is absent in many fish families, but found in nine of the 31 euteleostean orders (Percopsiformes, Myctophiformes, Aulopiformes, Stomiiformes, Salmoniformes, Osmeriformes, Characiformes, Siluriformes and Argentiniformes).[3] Famous representatives of these orders are salmon, characids and catfish.

The function of the adipose fin is something of a mystery. It is frequently clipped off to mark hatchery-raised fish, though data from 2005 showed that trout with their adipose fin removed have an 8% higher tailbeat frequency.[4][5] Additional information released in 2011 has suggested that the fin may be vital for the detection of, and response to, stimuli such as touch, sound and changes in pressure. Canadian researchers identified a neural network in the fin, indicating that it likely has a sensory function, but are still not sure exactly what the consequences of removing it are.[6][7] A comparative study in 2013 indicates the adipose fin can develop in two different ways. One is the salmoniform-type way, where the adipose fin develops from the larval-fin fold at the same time and in the same direct manner as the other median fins. The other is the characiform-type way, where the adipose fin develops late after the larval-fin fold has diminished and the other median fins have developed. They claim the existence of the characiform-type of development suggests the adipose fin is not "just a larval fin fold remainder" and is inconsistent with the view that the adipose fin lacks function.[3] Research published in 2014 indicates that the adipose fin has evolved repeatedly in separate lineages.[8] |

| Caudal fin (Tail fin) |

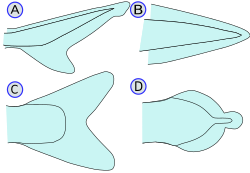

Heterocercal caudal fin (A)  Homocercal caudal fin (C)

|

The caudal fin is the tail fin (from the Latin cauda meaning tail), located at the end of the caudal peduncle. It is used for propulsion in most taxa (see also body-caudal fin locomotion). The tail fin is supported by the vertebrae of the axial skeleton and pterygiophores (radials). Depending on the relationship with the axial skeleton, four types of caudal fins (A-D) are distinguished:

(A) - Heterocercal means the vertebrae extend into the upper lobe of the tail, often making it longer than the lower lobe (as in sharks, †Placodermi, most stem Actinopterygii, and sturgeons and paddlefish). However, the external shape of heterocercal tail fins can also appear symmetric (e.g. †Birgeria, †Bobasatrania). Heterocercal is the opposite of hypocercal

(B) - Protocercal means the vertebrae extend to the tip of the tail and the tail is symmetrical but not expanded (as in the first fishes and the cyclostomes, and a more primitive precursor in lancelets) (C) - Homocercal where the fin usually appears superficially symmetric but in fact the vertebrae extend for a very short distance into the upper lobe of the fin. Homocercal caudal fins can, however, also appear asymmetric (e.g. blue flying fish). Most modern fishes (teleosts) have a homocercal tail. These come in a variety of shapes, and can appear:

(D) - Diphycercal means the vertebrae extend to the tip of the tail and the tail is symmetrical and expanded (as in the bichir, lungfish, lamprey, coelacanths and †Tarrasiiformes). Most Palaeozoic fishes had a diphycercal heterocercal tail.[11]

|

| Caudal keel Finlets |

|

Some types of fast-swimming fish have a horizontal caudal keel just forward of the tail fin. Much like the keel of a ship, this is a lateral ridge on the caudal peduncle, usually composed of scutes (see below), that provides stability and support to the caudal fin. There may be a single paired keel, one on each side, or two pairs above and below.

Finlets are small fins, generally behind the dorsal and anal fins (in bichirs, there are only finlets on the dorsal surface and no dorsal fin). In some fish such as tuna or sauries, they are rayless, non-retractable, and found between the last dorsal and/or anal fin and the caudal fin. |

Bony fishes

[edit]

Bony fishes (Actinopterygii and Sarcopterygii) form a taxonomic group called Osteichthyes (or Euteleostomi, which includes also land vertebrates); they have skeletons made of bone mostly, and can be contrasted with cartilaginous fishes (see below), which have skeletons made mainly of cartilage (except for their teeth, fin spines, and denticles).

Bony fishes are divided into ray-finned and lobe-finned fish. Most living fish are ray-finned, an extremely diverse and abundant group consisting of over 30,000 species. It is the largest class of vertebrates in existence today, making up more than 50% of species.[13] In the distant past, lobe-finned fish were abundant; however, there are currently only eight species.

Bony fish have fin spines called lepidotrichia or "rays" (due to how the spines spread open). They typically have swim bladders, which allow the fish to alter the relative density of its body and thus the buoyancy, so it can sink or float without having to use the fins to swim up and down.[14] However, swim bladders are absent in many fish, most notably in lungfishes, who have evolved their swim bladders into primitive lungs,[15] which may have a shared evolutionary origin with those of their terrestrial relatives, the tetrapods.[16] Bony fishes also have a pair of opercula that function to draw water across the gills, which help them breathe without needing to swim forward to force the water into the mouth across the gills.[14]

Lobe-fins

[edit]

Lobe-finned fishes form a class of bony fishes called Sarcopterygii. They have fleshy, lobed, paired fins, which are joined to the body by a series of bones.[17] The fins of lobe-finned fish differ from those of all other fish in that each is borne on a fleshy, lobe-like, scaly stalk extending from the body. Pectoral and pelvic fins have articulations resembling those of tetrapod limbs. These fins evolved into legs of the first tetrapod land vertebrates (amphibians) in the Devonian Period. Sarcopterygians also possess two dorsal fins with separate bases, as opposed to the single dorsal fin of most ray-finned fish (except some teleosts). The caudal fin is either heterocercal (only fossil taxa) or diphycercal.

The coelacanth is one type of living lobe-finned fish. Both extant members of this group, the West Indian Ocean coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae) and the Indonesian coelacanth (Latimeria menadoensis), are found in the genus Latimeria. Coelacanths are thought to have evolved roughly into their current form about 408 million years ago, during the early Devonian.[18]

Locomotion of the coelacanths is unique to their kind. To move around, coelacanths most commonly take advantage of up or downwellings of the current and drift. They use their paired fins to stabilise their movement through the water. While on the ocean floor their paired fins are not used for any kind of movement. Coelacanths can create thrust for quick starts by using their caudal fins. Due to the high number of fins they possess, coelacanths have high manoeuvrability and can orient their bodies in almost any direction in the water. They have been seen doing headstands and swimming belly up. It is thought that their rostral organ helps give the coelacanth electroperception, which aids in their movement around obstacles.[19]

Lungfish are also living lobe-finned fish. They occur in Africa (Protopterus), Australia (Neoceratodus), and South America (Lepidosiren). Lungfish evolved during the Devonian Period. Genetic studies and palaeontological data confirm that lungfish are the closest living relatives of land vertebrates.[20]

Fin arrangement and body shape is relatively conservative in lobe-finned fishes. However, there are a few examples from the fossil record that show aberrant morphologies, such as Allenypterus, Rebellatrix, Foreyia or the tetrapodomorphs.

Diversity of fins in lobe-finned fishes

[edit]-

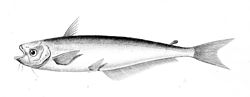

Spotted lungfish Protopterus dolloi

-

Queensland lungfish Neoceratodus forsteri

-

West Indian Ocean coelacanth Latimeria chalumnae

Ray-fins

[edit]

Ray-finned fishes form a class of bony fishes called Actinopterygii. Their fins contain spines or rays. A fin may contain only spiny rays, only soft rays, or a combination of both.[a] If both are present, the spiny rays are always anterior. Spines are generally stiff and sharp. Rays are generally soft, flexible, segmented, and may be branched. This segmentation of rays is the main difference that separates them from spines; spines may be flexible in certain species,[22]: 3 but they will never be segmented.[23][24]: 62–63

Spines have a variety of uses. In catfish, they are used as a form of defense; many catfish have the ability to lock their spines outwards. Triggerfish also use spines to lock themselves in crevices to prevent them being pulled out.

Lepidotrichia are usually composed of bone, but those of early osteichthyans - such as Cheirolepis - also had dentine and enamel.[25] They are segmented and appear as a series of disks stacked one on top of another. They may have been derived from dermal scales.[25] The genetic basis for the formation of the fin rays is thought to be genes coded for the production of certain proteins. It has been suggested that the evolution of the tetrapod limb from lobe-finned fishes is related to the loss of these proteins.[26]

Diversity of fins in ray-finned fishes

[edit]-

Fanfin angler Caulophryne jordani

-

Pancake batfish Halieutichthys aculeatus

-

Slender sunfish Ranzania laevis

-

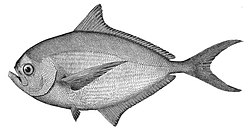

Fanfish Pteraclis carolinus

-

Diaphanous hatchetfish Sternoptyx diaphana

-

Silver roughy Hoplostethus mediterraneus

-

Crested flounder Lophonectes gallus

-

Jack-knifefish Equetus lanceolatus

-

Atlantic pomfret Brama brama

-

Atlantic wreckfish Polyprion americanus

-

Stellate pufferfish Arothron stellatus

-

Stargazing seadevil Ceratias uranoscopus

-

Ridgehead Poromitra unicornis

-

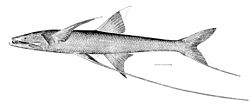

Tropical two-wing flyingfish Exocoetus evolans

-

Cusk-eel Benthocometes robustus

-

Rattail Trachonurus sulcatus

-

Tripod fish Bathypterois grallator

-

Giant oarfish Regalecus glesne

-

Shortbill spearfish Tetrapturus angustirostris

-

Ghost knifefish Sternarchorhynchus oxyrhynchus

-

Remora Remora brachyptera

-

Blue-dashed rockskipper Blenniella periophthalmus

-

Nile bichir Polypterus bichir

-

Coastal cutthroat trout Oncorhynchus clarkii

-

African butter catfish Schilbe mystus

-

Conger eel Leptocephalus conger

Cartilaginous fishes

[edit]

Cartilaginous fishes form a class of fishes called Chondrichthyes. They have skeletons made of cartilage rather than bone. The class includes sharks, rays and chimaeras.

Shark fin skeletons are elongated and supported with soft and unsegmented rays named ceratotrichia, filaments of elastic protein resembling the horny keratin in hair and feathers.[27] Originally the pectoral and pelvic girdles, which do not contain any dermal elements, did not connect. In later forms, each pair of fins became ventrally connected in the middle when scapulocoracoid and puboischiadic bars evolved. In rays, the pectoral fins have connected to the head and are very flexible. One of the primary characteristics present in most sharks is the heterocercal tail, which aids in locomotion.[28] Most sharks have eight fins. Sharks can only drift away from objects directly in front of them because their fins do not allow them to move in the tail-first direction.[29]

Unlike modern cartilaginous fish, members of stem chondrichthyan lineages (e.g. the †climatiids and the †diplacanthids)[30] possessed pectoral dermal plates as well as dermal spines associated with the paired fins. The oldest species demonstrating these features is the †acanthodian †Fanjingshania renovata[31] from the lower Silurian (Aeronian) of China. Fanjingshania possess compound pectoral plates composed of dermal scales fused to a bony plate and fin spines formed entirely of bone. Fin spines associated with the dorsal fins are rare among extant cartilaginous fishes, but are present, for instance, in Heterodontus or Squalus. Dorsal fin spines are typically developed in many fossil groups, such as in †Hybodontiformes, †Ctenacanthiformes or †Xenacanthida. In †Stethacanthus, the first dorsal fin spine was modified, forming a spine-brush complex.

As with most fish, the tails of sharks provide thrust, making speed and acceleration dependent on tail shape. Caudal fin shapes vary considerably between shark species, due to their evolution in separate environments. Sharks possess a heterocercal caudal fin in which the dorsal portion is usually noticeably larger than the ventral portion. This is because the shark's vertebral column extends into that dorsal portion, providing a greater surface area for muscle attachment. This allows more efficient locomotion among these negatively buoyant cartilaginous fish. By contrast, most bony fish possess a homocercal caudal fin.[32]

Tiger sharks have a large upper lobe, which allows for slow cruising and sudden bursts of speed. The tiger shark must be able to twist and turn in the water easily when hunting to support its varied diet, whereas the porbeagle shark, which hunts schooling fish such as mackerel and herring, has a large lower lobe to help it keep pace with its fast-swimming prey.[13] Other tail adaptations help sharks catch prey more directly, such as the thresher shark's usage of its powerful, elongated upper lobe to stun fish and squid.

On the other hand, rays rely on their enlarged pectoral fins for propulsion. Similarly enlarged pectoral fins can be found in the extinct †Petalodontiformes (e.g. †Belantsea, †Janassa, †Menaspis), which belong to Holocephali (ratfish and their fossil relatives), or in †Aquilolamna (Selachimorpha) and †Squatinactis (Squatinactiformes). Some cartilaginous fishes have an eel-like locomotion (e.g. Chlamydoselachus, †Thrinacoselache,[33] †Phoebodus[34])

Diversity of fins in cartilaginous fishes

[edit]-

Small-spotted catshark Scyliorhinus canicula

-

Great white shark Carcharodon carcharias

-

Common thresher Alopias vulpinus

-

Largetooth sawfish Pristis perotteti

-

Marbled electric ray Torpedo marmorata

-

Bennett's stingray Hemitrygon bennettii

-

Frilled shark Chlamydoselachus anguineus

-

The †Iniopterygiformes †Sibyrhynchus denisoni (Holocephali)

-

Cuban chimaera Chimaera cubana

-

American elephantfish Callorhinchus callorhynchus

Shark finning

[edit]

According to the Humane Society International, approximately 100 million sharks are killed each year for their fins, in an act known as shark finning.[35] After the fins are cut off, the mutilated sharks are thrown back in the water and left to die.

In some countries of Asia, shark fins are a culinary delicacy, such as shark fin soup.[36] Currently, international concerns over the sustainability and welfare of sharks have impacted consumption and availability of shark fin soup worldwide.[37] Shark finning is prohibited in many countries.

Fin functions

[edit]Generating thrust

[edit]Foil shaped fins generate thrust when moved, the lift of the fin sets water or air in motion and pushes the fin in the opposite direction. Aquatic animals get significant thrust by moving fins back and forth in water. Often the tail fin is used, but some aquatic animals generate thrust from pectoral fins.[38]

Cavitation occurs when negative pressure causes bubbles (cavities) to form in a liquid, which then promptly and violently collapse. It can cause significant damage and wear.[39] Cavitation damage can occur to the tail fins of powerful swimming marine animals, such as dolphins and tuna. Cavitation is more likely to occur near the surface of the ocean, where the ambient water pressure is relatively low. Even if they have the power to swim faster, dolphins may have to restrict their speed because collapsing cavitation bubbles on their tail are too painful.[40] Cavitation also slows tuna, but for a different reason. Unlike dolphins, these fish do not feel the bubbles, because they have bony fins without nerve endings. Nevertheless, they cannot swim faster because the cavitation bubbles create a vapor film around their fins that limits their speed. Lesions have been found on tuna that are consistent with cavitation damage.[40]

Scombrid fishes (tuna, mackerel and bonito) are particularly high-performance swimmers. Along the margin at the rear of their bodies is a line of small rayless, non-retractable fins, known as finlets. There has been much speculation about the function of these finlets. Research done in 2000 and 2001 by Nauen and Lauder indicated that "the finlets have a hydrodynamic effect on local flow during steady swimming" and that "the most posterior finlet is oriented to redirect flow into the developing tail vortex, which may increase thrust produced by the tail of swimming mackerel".[41][42][43]

Fish use multiple fins, so it is possible that a given fin can have a hydrodynamic interaction with another fin. In particular, the fins immediately upstream of the caudal (tail) fin may be proximate fins that can directly affect the flow dynamics at the caudal fin. In 2011, researchers using volumetric imaging techniques were able to generate "the first instantaneous three-dimensional views of wake structures as they are produced by freely swimming fishes". They found that "continuous tail beats resulted in the formation of a linked chain of vortex rings" and that "the dorsal and anal fin wakes are rapidly entrained by the caudal fin wake, approximately within the timeframe of a subsequent tail beat".[44]

Controlling motion

[edit]Once motion has been established, the motion itself can be controlled with the use of other fins.[38][45]

The bodies of reef fishes are often shaped differently from open water fishes. Open water fishes are usually built for speed, streamlined like torpedoes to minimise friction as they move through the water. Reef fish operate in the relatively confined spaces and complex underwater landscapes of coral reefs. For this manoeuvrability is more important than straight line speed, so coral reef fish have developed bodies which optimise their ability to dart and change direction. They outwit predators by dodging into fissures in the reef or playing hide and seek around coral heads.[49] The pectoral and pelvic fins of many reef fish, such as butterflyfish, damselfish and angelfish, have evolved so they can act as brakes and allow complex manoeuvres.[51] Many reef fish, such as butterflyfish, damselfish and angelfish, have evolved bodies which are deep and laterally compressed like a pancake, and will fit into fissures in rocks. Their pelvic and pectoral fins have evolved differently, so they act together with the flattened body to optimise manoeuvrability.[49] Some fishes, such as puffer fish, filefish and trunkfish, rely on pectoral fins for swimming and hardly use tail fins at all.[51]

Reproduction

[edit]Male cartilaginous fishes (sharks and rays), as well as the males of some live-bearing ray finned fishes, have fins that have been modified to function as intromittent organs, reproductive appendages which allow internal fertilization. In ray finned fish, they are called gonopodia or andropodia, and in cartilaginous fish, they are called claspers.

Gonopodia are found on the males of some species in the Anablepidae and Poeciliidae families. They are anal fins that have been modified to function as movable intromittent organs and are used to impregnate females with milt during mating. The third, fourth and fifth rays of the male's anal fin are formed into a tube-like structure in which the sperm of the fish is ejected.[54] When ready for mating, the gonopodium becomes erect and points forward towards the female. The male shortly inserts the organ into the sex opening of the female, with hook-like adaptations that allow the fish to grip onto the female to ensure impregnation. If a female remains stationary and her partner contacts her vent with his gonopodium, she is fertilised. The sperm is preserved in the female's oviduct. This allows females to fertilise themselves at any time without further assistance from males. In some species, the gonopodium may be half the total body length. Occasionally, the fin is too long to be used, as in the "lyretail" breeds of Xiphophorus helleri. Hormone treated females may develop gonopodia. These are useless for breeding.

Similar organs with similar characteristics are found in other fishes, for example the andropodium in the Hemirhamphodon or in the Goodeidae[55] or the gonopodium in the Middle Triassic †Saurichthys, the oldest known example of viviparity in a ray-finned fish.[56]

Claspers are found on the males of cartilaginous fishes. They are the posterior part of the pelvic fins that have also been modified to function as intromittent organs, and are used to channel semen into the female's cloaca during copulation. The act of mating in sharks usually includes raising one of the claspers to allow water into a siphon through a specific orifice. The clasper is then inserted into the cloaca, where it opens like an umbrella to anchor its position. The siphon then begins to contract expelling water and sperm.[57][58]

Other functions

[edit]Other uses of fins include walking and perching on the sea floor, gliding over water, cooling of body temperature, stunning of prey, display (scaring of predators, courtship), defence (venomous fin spines, locking between corals), luring of prey, and attachment structures.

The Indo-Pacific sailfish has a prominent dorsal fin. Like scombroids and other billfish, they streamline themselves by retracting their dorsal fins into a groove in their body when they swim.[59] The huge dorsal fin, or sail, of the sailfish is kept retracted most of the time. Sailfish raise them if they want to herd a school of small fish, and also after periods of high activity, presumably to cool down.[59][60]

The oriental flying gurnard has large pectoral fins which it normally holds against its body, and expands when threatened to scare predators. Despite its name, it is a demersal fish, not a flying fish, and uses its pelvic fins to walk along the bottom of the ocean.[62][63]

Fins can have an adaptive significance as sexual ornaments. During courtship, the female cichlid, Pelvicachromis taeniatus, displays a large and visually arresting purple pelvic fin. "The researchers found that males clearly preferred females with a larger pelvic fin and that pelvic fins grew in a more disproportionate way than other fins on female fish."[64][65]

Evolution

[edit]Evolution of paired fins

[edit]There are two prevailing hypotheses that have been historically debated as models for the evolution of paired fins in fish: the gill arch theory and the lateral fin-fold theory. The former, commonly referred to as the "Gegenbaur hypothesis," was posited in 1870 and proposes that the "paired fins are derived from gill structures".[67] This fell out of popularity in favour of the lateral fin-fold theory, first suggested in 1877, which proposes that paired fins budded from longitudinal, lateral folds along the epidermis just behind the gills.[68] There is weak support for both hypotheses in the fossil record and in embryology.[69] However, recent insights from developmental patterning have prompted reconsideration of both theories in order to better elucidate the origins of paired fins.

Classical theories

[edit]Carl Gegenbaur's concept of the "Archipterygium" was introduced in 1876.[70] It was described as a gill ray, or "joined cartilaginous stem," that extended from the gill arch. Additional rays arose from along the arch and from the central gill ray. Gegenbaur suggested a model of transformative homology – that all vertebrate paired fins and limbs were transformations of the archipterygium. Based on this theory, paired appendages such as pectoral and pelvic fins would have differentiated from the branchial arches and migrated posteriorly. However, there has been limited support for this hypothesis in the fossil record both morphologically and phylogenically.[69] In addition, there was little to no evidence of an anterior-posterior migration of pelvic fins.[71] Such shortcomings of the gill-arch theory led to its early demise in favour of the lateral fin-fold theory proposed by St. George Jackson Mivart, Francis Balfour, and James Kingsley Thacher.

The lateral fin-fold theory hypothesised that paired fins developed from lateral folds along the body wall of the fish.[68] Just as segmentation and budding of the median fin fold gave rise to the median fins, a similar mechanism of fin bud segmentation and elongation from a lateral fin fold was proposed to have given rise to the paired pectoral and pelvic fins. However, there was little evidence of a lateral fold-to-fin transition in the fossil record.[72] In addition, it was later demonstrated phylogenically that pectoral and pelvic fins arise from distinct evolutionary and mechanistic origins.[69]

Evolutionary developmental biology

[edit]Recent studies in the ontogeny and evolution of paired appendages have compared finless vertebrates – such as lampreys – with Chondrichthyes, the most basal living vertebrate with paired fins.[73] In 2006, researchers found that the same genetic programming involved in the segmentation and development of median fins was found in the development of paired appendages in catsharks.[74] Although these findings do not directly support the lateral fin-fold hypothesis, the original concept of a shared median-paired fin evolutionary developmental mechanism remains relevant.

A similar renovation of an old theory may be found in the developmental programming of chondricthyan gill arches and paired appendages. In 2009, researchers at the University of Chicago demonstrated that there are shared molecular patterning mechanisms in the early development of the chondricthyan gill arch and paired fins.[75] Findings such as these have prompted reconsideration of the once-debunked gill-arch theory.[72]

From fins to limbs

[edit]Fish are the ancestors of all mammals, reptiles, birds and amphibians.[76] In particular, terrestrial tetrapods (four-legged animals) evolved from fish and made their first forays onto land about 390 million years ago.[77] They used paired pectoral and pelvic fins for locomotion. The pectoral fins developed into forelegs (arms in the case of humans) and the pelvic fins developed into hind legs.[78] Much of the genetic machinery that builds a walking limb in a tetrapod is already present in the swimming fin of a fish.[79][80]

Aristotle recognised the distinction between analogous and homologous structures, and made the following prophetic comparison: "Birds in a way resemble fishes. For birds have their wings in the upper part of their bodies and fishes have two fins in the front part of their bodies. Birds have feet on their underpart and most fishes have a second pair of fins in their under-part and near their front fins."

In 2011, researchers at Monash University in Australia used primitive but still living lungfish "to trace the evolution of pelvic fin muscles to find out how the load-bearing hind limbs of the tetrapods evolved."[82][83] Further research at the University of Chicago found bottom-walking lungfishes had already evolved characteristics of the walking gaits of terrestrial tetrapods.[84][85]

In a classic example of convergent evolution, the pectoral limbs of pterosaurs, birds and bats further evolved along independent paths into flying wings. Even with flying wings, there are many similarities with walking legs, and core aspects of the genetic blueprint of the pectoral fin have been retained.[86][87]

The first mammals appeared during the Triassic period (between 251.9 and 201.4 million years ago). Several groups of these mammals started returning to the sea, including the cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoises). Recent DNA analysis suggests that cetaceans evolved from within the even-toed ungulates, and that they share a common ancestor with the hippopotamus.[88][89] About 23 million years ago, another group of bearlike land mammals started returning to the sea. These were the seals.[90] What had become walking limbs in cetaceans and seals evolved independently into new forms of swimming fins. The forelimbs became flippers, while the hindlimbs were either lost (cetaceans) or also modified into flipper (pinnipeds). In cetaceans, the tail gained two fins at the end, called a fluke.[91] Fish tails are usually vertical and move from side to side. Cetacean flukes are horizontal and move up and down, because cetacean spines bend the same way as in other mammals.[92][93]

Ichthyosaurs are ancient reptiles that resembled dolphins. They first appeared about 245 million years ago and disappeared about 90 million years ago.

"This sea-going reptile with terrestrial ancestors converged so strongly on fishes that it actually evolved a dorsal fin and tail fin for improved aquatic locomotion. These structures are all the more remarkable because they evolved from nothing — the ancestral terrestrial reptile had no hump on its back or blade on its tail to serve as a precursor."[94]

The biologist Stephen Jay Gould said the ichthyosaur was his favorite example of convergent evolution.[95]

Fins or flippers of varying forms and at varying locations (limbs, body, tail) have also evolved in a number of other tetrapod groups, including diving birds such as penguins (modified from wings), sea turtles (forelimbs modified into flippers), mosasaurs (limbs modified into flippers), and sea snakes (vertically expanded, flattened tail fin).

Robotic fins

[edit]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

The use of fins for the propulsion of aquatic animals can be remarkably effective. It has been calculated that some fish can achieve a propulsive efficiency greater than 90%.[38] Fish can accelerate and manoeuvre much more effectively than boats or submarine, and produce less water disturbance and noise. This has led to biomimetic studies of underwater robots which attempt to emulate the locomotion of aquatic animals.[97] An example is the Robot Tuna built by the Institute of Field Robotics, to analyze and mathematically model thunniform motion.[98] In 2005, the Sea Life London Aquarium displayed three robotic fish created by the computer science department at the University of Essex. The fish were designed to be autonomous, swimming around and avoiding obstacles like real fish. Their creator claimed that he was trying to combine "the speed of tuna, acceleration of a pike, and the navigating skills of an eel."[99][100][101]

The AquaPenguin, developed by Festo of Germany, copies the streamlined shape and propulsion by front flippers of penguins.[102][103] Festo also developed AquaRay,[104] AquaJelly[105] and AiraCuda,[106] respectively emulating the locomotion of manta rays, jellyfish and barracuda.

In 2004, Hugh Herr at MIT prototyped a biomechatronic robotic fish with a living actuator by surgically transplanting muscles from frog legs to the robot and then making the robot swim by pulsing the muscle fibers with electricity.[107][108]

Robotic fish offer some research advantages, such as the ability to examine an individual part of a fish design in isolation from the rest of the fish. However, this risks oversimplifying the biology so key aspects of the animal design are overlooked. Robotic fish also allow researchers to vary a single parameter, such as flexibility or a specific motion control. Researchers can directly measure forces, which is not easy to do in live fish. "Robotic devices also facilitate three-dimensional kinematic studies and correlated hydrodynamic analyses, as the location of the locomotor surface can be known accurately. And, individual components of a natural motion (such as outstroke vs. instroke of a flapping appendage) can be programmed separately, which is certainly difficult to achieve when working with a live animal."[109]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Standen, EM (2009). "Muscle activity and hydrodynamic function of pelvic fins in trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 213 (5): 831–841. doi:10.1242/jeb.033084. PMID 20154199.

- ^ Gene Helfman, Bruce Collette, Douglas Facey, & Brian Bowen. (2009) The Diversity of Fishes: biology, evolution, and ecology. John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ a b Bender, Anke; Moritz, Timo (1 September 2013). "Developmental residue and developmental novelty – different modes of adipose-fin formation during ontogeny". Zoosystematics and Evolution. 89 (2): 209–214. doi:10.1002/zoos.201300007. ISSN 1860-0743.

- ^ Tytell, E. (2005). "The Mysterious Little Fatty Fin". Journal of Experimental Biology. 208 (1): v–vi. Bibcode:2005JExpB.208Q...5T. doi:10.1242/jeb.01391.

- ^ Reimchen, T E; Temple, N F (2004). "Hydrodynamic and phylogenetic aspects of the adipose fin in fishes". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 82 (6): 910–916. Bibcode:2004CaJZ...82..910R. doi:10.1139/Z04-069.

- ^ Temple, Nicola (18 July 2011). "Removal of trout, salmon fin touches a nerve". Cosmos. Archived from the original on 12 January 2014.

- ^ Buckland-Nicks, J. A.; Gillis, M.; Reimchen, T. E. (2011). "Neural network detected in a presumed vestigial trait: ultrastructure of the salmonid adipose fin". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 279 (1728): 553–563. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.1009. PMC 3234561. PMID 21733904.

- ^ Stewart, Thomas A.; Smith, W. Leo; Coates, Michael I. (2014). "The origins of adipose fins: an analysis of homoplasy and the serial homology of vertebrate appendages". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 281 (1781) 20133120. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.3120. PMC 3953844. PMID 24598422.

- ^ Hyman, Libbie (1992). Hyman's Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy (3 ed.). The University of Chicago Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-226-87013-7. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ a b Brough, James (1936). "On the evolution of bony fishes during the Triassic Period". Biological Reviews. 11 (3): 385–405. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1936.tb00912.x. S2CID 84992418.

- ^ von Zittel KA, Woodward AS and Schlosser M (1932) Text-book of Paleontology Volume 2, Macmillan and Company. Page 13.

- ^ Kogan , Romano (2016). "Redescription of Saurichthys madagascariensis Piveteau, 1945 (Actinopterygii, Early Triassic), with implications for the early saurichthyid morphotype". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 36 (4) e1151886. Bibcode:2016JVPal..36E1886K. doi:10.1080/02724634.2016.1151886. S2CID 87234436.

- ^ a b Nelson, Joseph S. (1994). Fishes of the World. New York: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-54713-6. OCLC 28965588.

- ^ a b "Osteichthyes - Bony Fish". Wildlife Journal Junior. New Hampshire PBS. 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ Speer, B.R. (29 May 2000). "Introduction to the Dipnoi - the lungfish". University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ Biscotti, M.A.; Gerdol, M.; Canapa, A.; Forconi, M.; Olmo, E.; Pallavicini, A.; Barruca, M.; Schartl, M. (2016). "The Lungfish Transcriptome: A Glimpse into Molecular Evolution Events at the Transition from Water to Land". Scientific Reports. 6 21571: 21571. Bibcode:2016NatSR...621571B. doi:10.1038/srep21571. PMC 4764851. PMID 26908371.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: article number as page number (link) - ^ Clack, J. A. (2002) Gaining Ground. Indiana University

- ^ Johanson, Zerina; Long, John A.; Talent, John A.; Janvier, Philippe; Warren, James W. (2006). "Oldest Coelacanth, from the Early Devonian of Australia". Biology Letters. 2 (3): 443–46. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0470. PMC 1686207. PMID 17148426.

- ^ Fricke, Hans; Reinicke, Olaf; Hofer, Heribert; Nachtigall, Werner (1987). "Locomotion of the Coelacanth Latimeria Chalumnae in Its Natural Environment". Nature. 329 (6137): 331–33. Bibcode:1987Natur.329..331F. doi:10.1038/329331a0. S2CID 4353395.

- ^ Takezaki, N.; Nishihara, H. (2017). "Support for lungfish as the closest relative of tetrapods by using slowly evolving ray-finned fish as the outgroup". Genome Biology and Evolution. 9 (1): 93–101. doi:10.1093/gbe/evw288. PMC 5381532. PMID 28082606.

- ^ R. Froese; D. Pauly, eds. (October 2024). "Glossary". Fishbase. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ "Chapter 2 Lesson 2 Fins: Form and Function" (PDF). Fishing: Get in the Habitat! Leader's Guide (Second ed.). Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, MinnAqua and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Sport Fish Restoration. 2010. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ "Structure and Function - Fish". Exploring Our Fluid Earth: Teaching Science as Inquiry. Curriculum Research & Development Group, College of Education, University of Hawaiʻi. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ Lindsey, C.C. (1978). "1 - Form, Function, and Locomotory Habits in Fish". In Hoar, W.S.; Randall, D.J. (eds.). Fish Physiology. Vol. 7: Locomotion. Academic Press. pp. 1–100. doi:10.1016/S1546-5098(08)60163-6. ISBN 0-12-350407-4.

- ^ a b Zylberberg, L.; Meunier, F. J.; Laurin, M. (2016). "A microanatomical and histological study of the postcranial dermal skeleton of the Devonian actinopterygian Cheirolepis canadensis". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 61 (2): 363–376. doi:10.4202/app.00161.2015.

- ^ Zhang, J.; Wagh, P.; Guay, D.; Sanchez-Pulido, L.; Padhi, B. K.; Korzh, V.; Andrade-Navarro, M. A.; Akimenko, M. A. (2010). "Loss of fish actinotrichia proteins and the fin-to-limb transition". Nature. 466 (7303): 234–237. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..234Z. doi:10.1038/nature09137. PMID 20574421. S2CID 205221027.

- ^ Hamlett 1999, p. 528.

- ^ Function of the heterocercal tail in sharks: quantitative wake dynamics during steady horizontal swimming and vertical maneuvering - The Journal of Experimental Biology 205, 2365–2374 (2002)

- ^ "A Shark's Skeleton & Organs". Archived from the original on 5 August 2010. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- ^ Burrow, Carole (2021). Acanthodii, Stem Chondrichthyes. Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil. ISBN 978-3-89937-271-7. OCLC 1335983356.

- ^ Andreev, Plamen S.; Sansom, Ivan J.; Li, Qiang; Zhao, Wenjin; Wang, Jianhua; Wang, Chun-Chieh; Peng, Lijian; Jia, Liantao; Qiao, Tuo; Zhu, Min (September 2022). "Spiny chondrichthyan from the lower Silurian of South China". Nature. 609 (7929): 969–974. Bibcode:2022Natur.609..969A. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05233-8. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 36171377. S2CID 252570103.

- ^ Michael, Bright. "Jaws: The Natural History of Sharks". Columbia University. Archived from the original on 24 December 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ Grogan, Eileen D.; Lund, Richard (2008). "A basal elasmobranch, Thrinacoselache gracia n. gen and sp., (Thrinacodontidae, new family) from the Bear Gulch Limestone, Serpukhovian of Montana, USA". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (4): 970–988. Bibcode:2008JVPal..28..970G. doi:10.1671/0272-4634-28.4.970. S2CID 84735866.

- ^ Frey, Linda; Coates, Michael; Ginter, Michał; Hairapetian, Vachik; Rücklin, Martin; Jerjen, Iwan; Klug, Christian (2019). "The early elasmobranch Phoebodus: phylogenetic relationships, ecomorphology and a new time-scale for shark evolution". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 286 (1912). doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.1336. PMC 6790773. PMID 31575362. S2CID 203619135.

- ^ Shark Finning. Humane Society International.

- ^ Vannuccini S (1999). "Shark utilization, marketing and trade". FAO Fisheries Technical Paper. 389. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ^ "In China, victory for wildlife conservation as citizens persuaded to give up shark fin soup - The Washington Post". www.washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- ^ a b c Sfakiotakis, M; Lane, DM; Davies, JBC (1999). "Review of Fish Swimming Modes for Aquatic Locomotion" (PDF). IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering. 24 (2): 237–252. Bibcode:1999IJOE...24..237S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.459.8614. doi:10.1109/48.757275. S2CID 17226211. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013.

- ^ Franc, Jean-Pierre and Michel, Jean-Marie (2004) Fundamentals of Cavitation Springer. ISBN 9781402022326.

- ^ a b Brahic, Catherine (28 March 2008). "Dolphins swim so fast it hurts". New Scientist. Retrieved 31 March 2008.

- ^ Nauen, JC; Lauder, GV (2001a). "Locomotion in scombrid fishes: visualization of flow around the caudal peduncle and finlets of the Chub mackerel Scomber japonicus". Journal of Experimental Biology. 204 (Pt 13): 2251–63. Bibcode:2001JExpB.204.2251N. doi:10.1242/jeb.204.13.2251. PMID 11507109.

- ^ Nauen, JC; Lauder, GV (2001b). "Three-dimensional analysis of finlet kinematics in the Chub mackerel (Scomber japonicus)". The Biological Bulletin. 200 (1): 9–19. doi:10.2307/1543081. JSTOR 1543081. PMID 11249216. S2CID 28910289.

- ^ Nauen, JC; Lauder, GV (2000). "Locomotion in scombrid fishes: morphology and kinematics of the finlets of the Chub mackerel Scomber japonicus" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Biology. 203 (Pt 15): 2247–59. Bibcode:2000JExpB.203.2247N. doi:10.1242/jeb.203.15.2247. PMID 10887065.

- ^ Flammang, BE; Lauder, GV; Troolin, DR; Strand, TE (2011). "Volumetric imaging of fish locomotion". Biology Letters. 7 (5): 695–698. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.0282. PMC 3169073. PMID 21508026.

- ^ Fish, FE; Lauder, GV (2006). "Passive and active flow control by swimming fishes and mammals". Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics. 38 (1): 193–224. Bibcode:2006AnRFM..38..193F. doi:10.1146/annurev.fluid.38.050304.092201. S2CID 4983205.

- ^ Magnuson JJ (1978) "Locomotion by scombrid fishes: Hydromechanics, morphology and behavior" in Fish Physiology, Volume 7: Locomotion, WS Hoar and DJ Randall (Eds) Academic Press. Page 240–308. ISBN 9780123504074.

- ^ Ship's movements at sea Archived 25 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ Rana and Joag (2001) Classical Mechanics Page 391, Tata McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 9780074603154.

- ^ a b c Alevizon WS (1994) "Pisces Guide to Caribbean Reef Ecology" Gulf Publishing Company ISBN 1-55992-077-7

- ^ Lingham-Soliar, T. (2005). "Dorsal fin in the white shark,Carcharodon carcharias: A dynamic stabilizer for fast swimming". Journal of Morphology. 263 (1): 1–11. Bibcode:2005JMorp.263....1L. doi:10.1002/jmor.10207. PMID 15536651. S2CID 827610.

- ^ a b Ichthyology Florida Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ Masterson, J. "Gambusia affinis". Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 28 November 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ Kuntz, Albert (1913). "Notes on the Habits, Morphology of the Reproductive Organs, and Embryology of the Viviparous Fish Gambusia affinis". Bulletin of the United States Bureau of Fisheries. 33: 181–190.

- ^ Kapoor BG and Khanna B (2004) Ichthyology Handbook pp. 497–498, Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9783540428541.

- ^ Helfman G, Collette BB, Facey DH and Bowen BW (2009) The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution, and Ecology p. 35, Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-2494-2

- ^ Maxwell; et al. (2018). "Re-evaluation of the ontogeny and reproductive biology of the Triassic fish Saurichthys (Actinopterygii, Saurichthyidae)". Palaeontology. 61: 559–574. doi:10.5061/dryad.vc8h5.

- ^ "System glossary". FishBase. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ Heinicke, Matthew P.; Naylor, Gavin J. P.; Hedges, S. Blair (2009). The Timetree of Life: Cartilaginous Fishes (Chondrichthyes). Oxford University Press. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-19-156015-6.

- ^ a b Aquatic Life of the World pp. 332–333, Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 2000. ISBN 9780761471707.

- ^ Dement J Species Spotlight: Atlantic Sailfish (Istiophorus albicans) Archived 17 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine littoralsociety.org. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ Bertelsen E and Pietsch TW (1998). Encyclopedia of Fishes. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 138–139. ISBN 978-0-12-547665-2.

- ^ Purple Flying Gurnard, Dactyloptena orientalis (Cuvier, 1829) Australian Museum. Updated: 15 September 2012. Retrieved: 2 November 2012.

- ^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Dactyloptena orientalis". FishBase. November 2012 version.

- ^ Female fish flaunt fins to attract a mate ScienceDaily. 8 October 2010.

- ^ Baldauf, SA; Bakker, TCM; Herder, F; Kullmann, H; Thünken, T (2010). "Male mate choice scales female ornament allometry in a cichlid fish". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 10 (1): 301. Bibcode:2010BMCEE..10..301B. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-301. PMC 2958921. PMID 20932273.

- ^ Schultz, Ken (2011) Ken Schultz's Field Guide to Saltwater Fish Page 250, John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118039885.

- ^ Goodrich, Edwin S. 1906. "Memoirs: Notes on the Development, Structure, and Origin of the Median and Paired Fins of Fish." Journal of Cell Science s2-50 (198): 333–76.

- ^ a b Brand, Richard A (2008). "Origin and Comparative Anatomy of the Pectoral Limb". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 466 (3): 531–42. doi:10.1007/s11999-007-0102-6. PMC 2505211. PMID 18264841.

- ^ a b c Coates, M. I. (2003). "The Evolution of Paired Fins". Theory in Biosciences. 122 (2–3): 266–87. Bibcode:2003ThBio.122..266C. doi:10.1078/1431-7613-00087 (inactive 1 July 2025).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Gegenbaur, C., F. J. Bell, and E. Ray Lankester. 1878. Elements of Comparative Anatomy. By Carl Gegenbaur ... Tr. by F. Jeffrey Bell ... The Translation Rev. and a Preface Written by E. Ray Lankester ... London,: Macmillan and Co.,.

- ^ Goodrich, Edwin S. 1906. "Memoirs: Notes on the Development, Structure, and Origin of the Median and Paired Fins of Fish." Journal of Cell Science s2-50 (198): 333–76.

- ^ a b Begemann, Gerrit (2009). "Evolutionary Developmental Biology". Zebrafish. 6 (3): 303–4. doi:10.1089/zeb.2009.0593.

- ^ Cole, Nicholas J.; Currie, Peter D. (2007). "Insights from Sharks: Evolutionary and Developmental Models of Fin Development". Developmental Dynamics. 236 (9): 2421–31. doi:10.1002/dvdy.21268. PMID 17676641. S2CID 40763215.

- ^ Freitas, Renata; Zhang, GuangJun; Cohn, Martin J. (2006). "Evidence That Mechanisms of Fin Development Evolved in the Midline of Early Vertebrates". Nature. 442 (7106): 1033–37. Bibcode:2006Natur.442.1033F. doi:10.1038/nature04984. PMID 16878142. S2CID 4322878.

- ^ Gillis, J. A.; Dahn, R. D.; Shubin, N. H. (2009). "Shared Developmental Mechanisms Pattern the Vertebrate Gill Arch and Paired Fin Skeletons". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (14): 5720–24. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.5720G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810959106. PMC 2667079. PMID 19321424.

- ^ "Primordial Fish Had Rudimentary Fingers" ScienceDaily, 23 September 2008.

- ^ "From fins to limbs and water to land" The Harvard Gazette, 25 November 2020, Harvard University.

- ^ Hall, Brian K (2007) Fins into Limbs: Evolution, Development, and Transformation University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226313375.

- ^ Shubin, Neil (2009) Your inner fish: A journey into the 3.5 billion year history of the human body Vintage Books. ISBN 9780307277459. UCTV interview

- ^ Clack, Jennifer A (2012) "From fins to feet" Chapter 6, pages 187–260, in: Gaining Ground, Second Edition: The Origin and Evolution of Tetrapods, Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253356758.

- ^ Moore, John A (1988). "[www.sicb.org/dl/saawok/449.pdf "Understanding nature—form and function"] Page 485". American Zoologist. 28 (2): 449–584. doi:10.1093/icb/28.2.449.

- ^ Lungfish Provides Insight to Life On Land: 'Humans Are Just Modified Fish' ScienceDaily, 7 October 2011.

- ^ Cole, NJ; Hall, TE; Don, EK; Berger, S; Boisvert, CA; et al. (2011). "Development and Evolution of the Muscles of the Pelvic Fin". PLOS Biology. 9 (10) e1001168. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001168. PMC 3186808. PMID 21990962.

- ^ "A small step for lungfish, a big step for the evolution of walking" ScienceDaily, 13 December 2011.

- ^ King, HM; Shubin, NH; Coates, MI; Hale, ME (2011). "Behavioral evidence for the evolution of walking and bounding before terrestriality in sarcopterygian fishes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (52): 21146–21151. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10821146K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1118669109. PMC 3248479. PMID 22160688.

- ^ Shubin, N; Tabin, C; Carroll, S (1997). "Fossils, genes and the evolution of animal limbs" (PDF). Nature. 388 (6643): 639–648. Bibcode:1997Natur.388..639S. doi:10.1038/41710. PMID 9262397. S2CID 2913898. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 September 2012.

- ^ Vertebrate flight: The three solutions University of California. Updated 29 September 2005.

- ^ "Scientists find missing link between the dolphin, whale and its closest relative, the hippo". Science News Daily. 25 January 2005. Archived from the original on 4 March 2007. Retrieved 18 June 2007.

- ^ Gatesy, J. (1 May 1997). "More DNA support for a Cetacea/Hippopotamidae clade: the blood-clotting protein gene gamma-fibrinogen". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 14 (5): 537–543. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025790. PMID 9159931.

- ^ Flynn JJ, Finarelli JA, Zehr S, Hsu J, Nedbal MA (2005). "Molecular phylogeny of the carnivora (mammalia): assessing the impact of increased sampling on resolving enigmatic relationships". Systematic Biology. 54 (2): 317–337. doi:10.1080/10635150590923326. PMID 16012099.

- ^ Felts WJL "Some functional and structural characteristics of cetacean flippers and flukes" Pages 255–275 in: Norris KS (ed.) Whales, Dolphins, and Porpoises, University of California Press.

- ^ The evolution of whales University of California Museum. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ^ Thewissen, JGM; Cooper, LN; George, JC; Bajpai, S (2009). "From Land to Water: the Origin of Whales, Dolphins, and Porpoises" (PDF). Evo Edu Outreach. 2 (2): 272–288. doi:10.1007/s12052-009-0135-2. S2CID 11583496.

- ^ Martill D.M. (1993). "Soupy Substrates: A Medium for the Exceptional Preservation of Ichthyosaurs of the Posidonia Shale (Lower Jurassic) of Germany". Kaupia - Darmstädter Beiträge zur Naturgeschichte, 2 : 77-97.

- ^ Gould,Stephen Jay (1993) "Bent Out of Shape" in Eight Little Piggies: Reflections in Natural History. Norton, 179–94. ISBN 9780393311396.

- ^ "Charlie: CIA's Robotic Fish". Central Intelligence Agency. 4 June 2013. Archived from the original on 16 August 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ Richard Mason. "What is the market for robot fish?". Archived from the original on 4 July 2009.

- ^ Witoon Juwarahawong. "Fish Robot". Institute of Field Robotics. Archived from the original on 4 November 2007. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ^ "Robotic fish powered by Gumstix PC and PIC". Human Centred Robotics Group at Essex University. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ^ "Robotic fish make aquarium debut". cnn.com. CNN. 10 October 2005. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ Walsh, Dominic (3 May 2008). "Merlin Entertainments tops up list of London attractions with aquarium buy". The Times. Times of London. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ For Festo, Nature Shows the Way Control Engineering, 18 May 2009.

- ^ Bionic penguins fly through water... and air Gizmag, 27 April 2009.

- ^ Festo AquaRay Robot Technovelgy, 20 April 2009.

- ^ The AquaJelly Robotic Jellyfish from Festo Engineering TV, 12 July 2012.

- ^ Lightweight robots: Festo's flying circus Archived 19 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine The Engineer, 18 July 2011.

- ^ Huge Herr, D. Robert G (October 2004). "A Swimming Robot Actuated by Living Muscle Tissue". Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation. 1 (1) 6. doi:10.1186/1743-0003-1-6. PMC 544953. PMID 15679914.

- ^ How Biomechatronics Works HowStuffWorks/ Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ Lauder, G. V. (2011). "Swimming hydrodynamics: ten questions and the technical approaches needed to resolve them" (PDF). Experiments in Fluids. 51 (1): 23–35. Bibcode:2011ExFl...51...23L. doi:10.1007/s00348-009-0765-8. S2CID 890431.

Bibliography

[edit]- Hamlett, William C. (1999). Sharks, skates, and rays: the biology of elasmobranch fishes (1st ed.). The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-8018-6048-5.

Further reading

[edit]- Hall, Brian K (2007) Fins into Limbs: Evolution, Development, and Transformation University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226313375.

- Helfman G, Collette BB, Facey DE and Bowen BW (2009) "Functional morphology of locomotion and feeding" Chapter 8, pp. 101–116. In:The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444311907.

- Lauder, GV; Nauen, JC; Drucker, EG (2002). "Experimental Hydrodynamics and Evolution: Function of Median Fins in Ray-finned Fishes". Integr. Comp. Biol. 42 (5): 1009–1017. doi:10.1093/icb/42.5.1009. PMID 21680382.

- Lauder, GV; Drucker, EG (2004). "Morphology and experimental hydrodynamics of fish fin control surfaces" (PDF). Journal of Oceanic Engineering. 29 (3): 556–571. Bibcode:2004IJOE...29..556L. doi:10.1109/joe.2004.833219. S2CID 36207755.

External links

[edit]- Homology of fin lepidotrichia in osteichthyan fishes

- The Fish's Fin Earthlife Web

- Can robot fish find pollution? HowStuffWorks. Accessed 30 January 2012.

.png/250px-Lampanyctodes_hectoris_(fins).png)

.png/2000px-Lampanyctodes_hectoris_(fins).png)