Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Poverty

View on Wikipedia

Poverty is a state or condition in which an individual lacks the financial resources and essentials for a basic standard of living. Poverty can have diverse environmental, legal, social, economic, and political causes and effects.[1] When evaluating poverty in statistics or economics there are two main measures: absolute poverty which compares income against the amount needed to meet basic personal needs, such as food, clothing, and shelter;[2] secondly, relative poverty measures when a person cannot meet a minimum level of living standards, compared to others in the same time and place. The definition of relative poverty varies from one country to another, or from one society to another.[2]

Statistically, as of 2019[update], most of the world's population live in poverty: in PPP dollars, 85% of people live on less than $30 per day, two-thirds live on less than $10 per day, and 10% live on less than $1.90 per day.[3] According to the World Bank Group in 2020, more than 40% of the poor live in conflict-affected countries.[4] Even when countries experience economic development, the poorest citizens of middle-income countries frequently do not gain an adequate share of their countries' increased wealth to leave poverty.[5][page needed] Governments and non-governmental organizations have experimented with a number of different policies and programs for poverty alleviation, such as electrification in rural areas or housing first policies in urban areas. The international policy frameworks for poverty alleviation, established by the United Nations in 2015, are summarized in Sustainable Development Goal 1: "No Poverty".

Social forces, such as gender, disability, race and ethnicity, can exacerbate issues of poverty—with women, children and minorities frequently bearing unequal burdens of poverty. Moreover, impoverished individuals are more vulnerable to the effects of other social issues, such as the environmental effects of industry or the impacts of climate change or other natural disasters or extreme weather events. Poverty can also make other social problems worse; economic pressures on impoverished communities frequently play a part in deforestation, biodiversity loss and ethnic conflict. For this reason, the UN's Sustainable Development Goals and other international policy programs, such as the international recovery from COVID-19, emphasize the connection of poverty alleviation with other societal goals.[6]

Definitions and etymology

[edit]The word poverty comes from the old (Norman) French word poverté (Modern French: pauvreté), from Latin paupertās from pauper (poor).[7][page needed]

There are several definitions of poverty depending on the context of the situation it is placed in. It usually references a state or condition in which a person or community lacks the financial resources and essentials for a basic standard of living.

United Nations: Fundamentally, poverty is a denial of choices and opportunities, a violation of human dignity. It means lack of basic capacity to participate effectively in society. It means not having enough to feed and clothe a family, not having a school or clinic to go to, not having the land on which to grow one's food or a job to earn one's living, not having access to credit. It means insecurity, powerlessness and exclusion of individuals, households and communities. It means susceptibility to violence, and it often implies living in marginal or fragile environments, without access to clean water or sanitation.[8]

World Bank: Poverty is pronounced deprivation in well-being, and comprises many dimensions. It includes low incomes and the inability to acquire the basic goods and services necessary for survival with dignity. Poverty also encompasses low levels of health and education, poor access to clean water and sanitation, inadequate physical security, lack of voice, and insufficient capacity and opportunity to better one's life.[9]

European Union (EU): The European Union's definition of poverty is significantly different from definitions in other parts of the world, and consequently policy measures introduced to combat poverty in EU countries also differ from measures in other nations. Poverty is measured in relation to the distribution of income in each member country using relative income poverty lines:[10] an EEC Council Decision in 1984 stated that for EEC purposes, "the poor" should be taken to "mean persons, families and groups of persons whose resources (material, cultural and social) are so limited as to exclude them from the minimum acceptable way of life in the Member States in which they live".[11][a] Relative-income poverty rates in the EU are compiled by the Eurostat, in charge of coordinating, gathering, and disseminating member country statistics using European Union Survey of Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) surveys.[10]

Measuring poverty

[edit]Absolute poverty

[edit]

Absolute poverty, often synonymous with 'extreme poverty' or 'abject poverty', refers to a set standard which is consistent over time and between countries. This set standard usually refers to "a condition characterized by severe deprivation of basic human needs, including food, safe drinking water, sanitation facilities, health, shelter, education and information. It depends not only on income but also on access to services."[14][15][16] Having an income below the poverty line, which is defined as an income needed to purchase basic needs, is also referred to as primary poverty.

The "dollar a day" poverty line was first introduced in 1990 as a measure to meet such standards of living. For nations that do not use the US dollar as currency, "dollar a day" does not translate to living a day on the equivalent amount of local currency as determined by the exchange rate.[17] Rather, it is determined by the purchasing power parity rate, which would look at how much local currency is needed to buy the same things that a dollar could buy in the United States.[17] Usually, this would translate to having less local currency than if the exchange rate were used.[17]

From 1993 through 2005, the World Bank defined absolute poverty as $1.08 a day on such a purchasing power parity basis, after adjusting for inflation to the 1993 US dollar[18] In 2009, it was updated as $1.25 a day (equivalent to $1.00 a day in 1996 US prices)[19][20] and in 2015, it was updated as living on less than US$1.90 per day,[21] and moderate poverty as less than $2 or $5 a day.[22] Similarly, 'ultra-poverty' is defined by a 2007 report issued by International Food Policy Research Institute as living on less than 54 cents per day.[23] The poverty line threshold of $1.90 per day, as set by the World Bank, is controversial. Each nation has its own threshold for absolute poverty line; in the United States, for example, the absolute poverty line was US$15.15 per day in 2010 (US$22,000 per year for a family of four),[24] while in India it was US$1.0 per day[25] and in China the absolute poverty line was US$0.55 per day, each on PPP basis in 2010.[26] These different poverty lines make data comparison between each nation's official reports qualitatively difficult. Some scholars argue that the World Bank method sets the bar too high,[27] others argue it is too low.

There is disagreement among experts as to what would be considered a realistic poverty rate with one considering it "an inaccurately measured and arbitrary cut off".[28] Some contend that a higher poverty line is needed, such as a minimum of $7.40 or even $10 to $15 a day. They argue that these levels are a minimum for basic needs and to achieve normal life expectancy.[29]

One estimate places the true scale of poverty much higher than the World Bank, with an estimated 4.3 billion people (59% of the world's population) living with less than $5 a day and unable to meet basic needs adequately.[30] Philip Alston, a UN special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, stated the World Bank's international poverty line of $1.90 a day is fundamentally flawed, and has allowed for "self congratulatory" triumphalism in the fight against extreme global poverty, which he asserts is "completely off track" and that nearly half of the global population, or 3.4 billion, lives on less than $5.50 a day, and this number has barely moved since 1990.[31] Still others suggest that poverty line misleads because many live on far less than that line.[25][32][33]

Other measures of absolute poverty without using a certain dollar amount include the standard defined as receiving less than 80% of minimum caloric intake whilst spending more than 80% of income on food, sometimes called ultra-poverty.[34]

Relative poverty

[edit]

Relative poverty views poverty as socially defined and dependent on social context. It is argued that the needs considered fundamental is not an objective measure[35][36] and could change with the custom of society.[37][35] For example, a person who cannot afford housing better than a small tent in an open field would be said to live in relative poverty if almost everyone else in that area lives in modern brick homes, but not if everyone else also lives in small tents in open fields (for example, in a nomadic tribe). Since richer nations would have lower levels of absolute poverty,[38][39] relative poverty is considered the "most useful measure for ascertaining poverty rates in wealthy developed nations"[40][41][42][43][44] and is the "most prominent and most-quoted of the EU social inclusion indicators".[45]

Usually, relative poverty is measured as the percentage of the population with income less than some fixed proportion of median income. This is a calculation of the percentage of people whose family household income falls below the Poverty Line. The main poverty line used in the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the European Union (EU) is based on "economic distance", a level of income set at 60% of the median household income.[46] The United States federal government typically regulates this line to three times the cost of an adequate meal.[47]

There are several other different income inequality metrics, for example, the Gini coefficient or the Theil Index.

Other aspects

[edit]

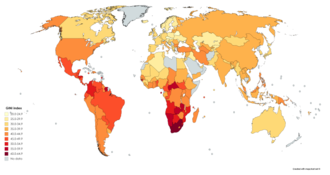

≥ 0.900 0.850–0.899 0.800–0.849 0.750–0.799 0.700–0.749 | 0.650–0.699 0.600–0.649 0.550–0.599 0.500–0.549 0.450–0.499 | 0.400–0.449 ≤ 0.399 Data unavailable |

Rather than income, poverty is also measured through individual basic needs at a time. Life expectancy has greatly increased in the developing world since World War II and is starting to close the gap to the developed world.[49] Child mortality has decreased in every developing region of the world.[50] The proportion of the world's population living in countries where the daily per-capita supply of food energy is less than 9,200 kilojoules (2,200 kilocalories) decreased from 56% in the mid-1960s to below 10% by the 1990s. Similar trends can be observed for literacy, access to clean water and electricity and basic consumer items.[51]

Poverty may also be understood as an aspect of unequal social status and inequitable social relationships, experienced as social exclusion, dependency, and diminished capacity to participate, or to develop meaningful connections with other people in society.[52][53][54] Such social exclusion can be minimized through strengthened connections with the mainstream, such as through the provision of relational care to those who are experiencing poverty. The World Bank's "Voices of the Poor", based on research with over 20,000 poor people in 23 countries, identifies a range of factors which poor people identify as part of poverty. These include abuse by those in power, dis-empowering institutions, excluded locations, gender relationships, lack of security, limited capabilities, physical limitations, precarious livelihoods, problems in social relationships, weak community organizations and discrimination. Analysis of social aspects of poverty links conditions of scarcity to aspects of the distribution of resources and power in a society and recognizes that poverty may be a function of the diminished "capability" of people to live the kinds of lives they value. The social aspects of poverty may include lack of access to information, education, health care, social capital or political power.[55][56]

Relational poverty is the idea that societal poverty exists if there is a lack of human relationships. Relational poverty can be the result of a lost contact number, lack of phone ownership, isolation, or deliberate severing of ties with an individual or community. Relational poverty is also understood "by the social institutions that organize those relationships...poverty is importantly the result of the different terms and conditions on which people are included in social life".[57]

In the United Kingdom, the second Cameron ministry came under attack for its redefinition of poverty; poverty is no longer classified by a family's income, but as to whether a family is in work or not.[58] Considering that two-thirds of people who found work were accepting wages that are below the living wage (according to the Joseph Rowntree Foundation[59]) this has been criticised by anti-poverty campaigners as an unrealistic view of poverty in the United Kingdom.[58]

Secondary poverty

[edit]Secondary poverty refers to those that earn enough income to not be impoverished, but who spend their income on unnecessary pleasures, such as alcoholic beverages, thus placing them below it in practice.[60] In 18th- and 19th-century Great Britain, the practice of temperance among Methodists, as well as their rejection of gambling, allowed them to eliminate secondary poverty and accumulate capital.[61] Factors that contribute to secondary poverty includes but are not limited to: alcohol, gambling, tobacco and drugs. Substance abuse means that the poor typically spend about 2% of their income educating their children but larger percentages of alcohol and tobacco (for example, 6% in Indonesia and 8% in Mexico as of 2006).[62][needs update]

Variability

[edit]Poverty levels are snapshot pictures in time that omits the transitional dynamics between levels. Mobility statistics supply additional information about the fraction who leave the poverty level. For example, one study finds that in a sixteen-year period (1975 to 1991 in the US) only 5% of those in the lower fifth of the income level were still at that level, while 95% transitioned to a higher income category.[63] Poverty levels can remain the same while those who rise out of poverty are replaced by others. The transient poor and chronic poor differ in each society. In a nine-year period ending in 2005 for the US, 50% of the poorest quintile transitioned to a higher quintile.[64]

Global prevalence

[edit]

According to Chen and Ravallion, about 1.76 billion people in the developing world lived above $1.25 per day and 1.9 billion people lived below $1.25 per day in 1981. In 2005, about 4.09 billion people in the developing world lived above $1.25 per day and 1.4 billion people lived below $1.25 per day (both 1981 and 2005 data are on inflation adjusted basis).[65][66] The share of the world's population living in absolute poverty fell from 43% in 1981 to 14% in 2011.[67] The absolute number of people in poverty fell from 1.95 billion in 1981 to 1.01 billion in 2011.[68] The economist Max Roser estimates that the number of people in poverty is therefore roughly the same as 200 years ago.[68] This is the case since the world population was just little more than 1 billion in 1820 and the majority (84% to 94%)[69] of the world population was living in poverty.

According to one study, the percentage of the world population in hunger and poverty fell in absolute percentage terms from 50% in 1950 to 30% in 1970.[70] According to another study the number of people worldwide living in absolute poverty fell from 1.18 billion in 1950 to 1.04 billion in 1977.[71] According to another study, the number of people worldwide estimated to be starving fell from almost 920 million in 1971 to below 797 million in 1997.[72] The proportion of the developing world's population living in extreme economic poverty fell from 28% in 1990 to 21% in 2001.[67] Most of this improvement has occurred in East and South Asia.[73]

In 1963, the Third World Food Survey estimated that 10-15% of the world’s population were undernourished and that up to half suffered from general hunger hunger and malnutrition.[74] In subsequent decades, however, estimated levels of malnutrition and undernourshent steadily fell. From 1970 to 1990, the percentage of the world’s population estimated to be suffering from malnutrition fell from 24.8% to 15.9.%.[75] From 1970 to 2015, the percentage of people in developing nations estimated to be undernourished fell from 34.75% to 12.90%.[76]

In 2012 it was estimated that, using a poverty line of $1.25 a day, 1.2 billion people lived in poverty.[77] Given the current economic model, built on GDP, it would take 100 years to bring the world's poorest up to the poverty line of $1.25 a day.[78] UNICEF estimates half the world's children (or 1.1 billion) live in poverty.[79] The World Bank forecasted in 2015 that 702.1 million people were living in extreme poverty, down from 1.75 billion in 1990.[80] Extreme poverty is observed in all parts of the world, including developed economies.[81][82] Of the 2015 population, about 347.1 million people (35.2%) lived in Sub-Saharan Africa and 231.3 million (13.5%) lived in South Asia. According to the World Bank, between 1990 and 2015, the percentage of the world's population living in extreme poverty fell from 37.1% to 9.6%, falling below 10% for the first time.[83]

During the 2013 to 2015 period, the World Bank reported that extreme poverty fell from 11% to 10%, however they also noted that the rate of decline had slowed by nearly half from the 25 year average with parts of sub-saharan Africa returning to early 2000 levels.[84][85] The World Bank attributed this to increasing violence following the Arab Spring, population increases in Sub-Saharan Africa, and general African inflationary pressures and economic malaise were the primary drivers for this slow down.[86][87] Many wealthy nations have seen an increase in relative poverty rates ever since the Great Recession, in particular among children from impoverished families who often reside in substandard housing and find educational opportunities out of reach.[88] It has been argued by some academics that the neoliberal policies promoted by global financial institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank are actually exacerbating both inequality and poverty.[89][90]

In East Asia the World Bank reported that "The poverty headcount rate at the $2-a-day level is estimated to have fallen to about 27 percent [in 2007], down from 29.5 percent in 2006 and 69 percent in 1990."[91] The People's Republic of China accounts for over three quarters of global poverty reduction from 1990 to 2005, which according to the World Bank is "historically unprecedented".[92] China accounted for nearly half of all extreme poverty in 1990.[93]

In Sub-Saharan Africa extreme poverty went up from 41% in 1981 to 46% in 2001,[94] which combined with growing population increased the number of people living in extreme poverty from 231 million to 318 million.[95] Statistics of 2018 shows population living in extreme conditions has declined by more than 1 billion in the last 25 years. As per the report published by the world bank on 19 September 2018 world poverty falls below 750 million.[96]

In the early 1990s some of the transition economies of Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia experienced a sharp drop in income.[97] The collapse of the Soviet Union resulted in large declines in GDP per capita, of about 30 to 35% between 1990 and the through year of 1998 (when it was at its minimum). As a result, poverty rates tripled,[98] excess mortality increased,[99][100] and life expectancy declined.[101] Russian President Boris Yeltsin's IMF-backed rapid privatization and austerity policies resulted in unemployment rising to double digits and half the Russian population falling into destitution by the early to mid 1990s.[102] By 1999, during the peak of the poverty crisis, 191 million people were living on less than $5.50 a day.[103] In subsequent years as per capita incomes recovered the poverty rate dropped from 31.4% of the population to 19.6%.[104][105] The average post-communist country had returned to 1989 levels of per-capita GDP by 2005,[106] although as of 2015 some are still far behind that.[107] According to the World Bank in 2014, around 80 million people were still living on less than $5.00 a day.[103]

World Bank data shows that the percentage of the population living in households with consumption or income per person below the poverty line has decreased in each region of the world except Middle East and North Africa since 1990:[108][109]

In July 2023, a group of over 200 economists from 67 countries, including Jayati Ghosh, Joseph Stiglitz and Thomas Piketty, sent a letter to the United Nations secretary general António Guterres and World Bank president Ajay Banga warning that "extreme poverty and extreme wealth have risen sharply and simultaneously for the first time in 25 years."[110] In 2024, Oxfam reported that roughly five billion people have become poorer since 2020 and warned that current trends could postpone global poverty eradication for 229 years.[111]

| Region | $2.15 per day[112] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1981 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| East Asia and Pacific | 83.5% | 65.8% | 39.5% | 13.3% | 1.6% | 1.2% |

| Europe and Central Asia | — | — | 9.1% | 4.1% | 2.3% | 2.3% |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 15.1% | 16.8% | 13.5% | 6.4% | 4.3% | 4.3% |

| Middle East and North Africa | — | 6.5% | 3.5% | 1.9% | 9.6% | — |

| South Asia | 58% | 49.8% | — | 26% | 10.1% | 8.6% |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | — | 53.8% | 56.5% | 42.2% | 35.4% | 34.9% |

| World | 43.6% | 37.9% | 29.3% | 16.3% | 9% | 8.5% |

Characteristics

[edit]

The effects of poverty may also be causes of poverty thus creating a cycle of poverty operating across multiple levels, individual, local, national and global.

Health

[edit]

One-third of deaths around the world—some 18 million people a year or 50,000 per day—are due to poverty-related causes. People living in developing nations, among them women and children, are overrepresented among the global poor and these effects of severe poverty.[114][115][116] Those living in poverty suffer disproportionately from hunger or even starvation and disease, as well as lower life expectancy.[117][118] According to the World Health Organization, hunger and malnutrition are the single gravest threats to the world's public health and malnutrition is by far the biggest contributor to child mortality, present in half of all cases.[119]

Almost 90% of maternal deaths during childbirth occur in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, compared to less than 1% in the developed world.[120] Those who live in poverty have also been shown to have a far greater likelihood of having or incurring a disability within their lifetime.[121] Infectious diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis can perpetuate poverty by diverting health and economic resources from investment and productivity; malaria decreases GDP growth by up to 1.3% in some developing nations and AIDS decreases African growth by 0.3–1.5% annually.[122][123][124]

Studies have shown that poverty impedes cognitive function although some of these findings could not be replicated in follow-up studies.[125] One hypothesised mechanism is that financial worries put a severe burden on one's mental resources so that they are no longer fully available for solving complicated problems. The reduced capability for problem solving can lead to suboptimal decisions and further perpetuate poverty.[126] Many other pathways from poverty to compromised cognitive capacities have been noted, from poor nutrition and environmental toxins to the effects of stress on parenting behavior, all of which lead to suboptimal psychological development.[127][128] Neuroscientists have documented the impact of poverty on brain structure and function throughout the lifespan.[129]

Infectious diseases continue to blight the lives of the poor across the world. 36.8 million people are living with HIV/AIDS, with 954,492 deaths in 2017.[130]

Poor people often are more prone to severe diseases due to the lack of health care, and due to living in non-optimal conditions. Among the poor, girls tend to suffer even more due to gender discrimination. Economic stability is paramount in a poor household; otherwise they go in an endless loop of negative income trying to treat diseases. Often when a person in a poor household falls ill it is up to the family members to take care of them due to limited access to health care and lack of health insurance. The household members often have to give up their income or stop seeking further education to tend to the sick member. There is a greater opportunity cost imposed on the poor to tend to someone compared to someone with better financial stability.[131] Increased access to healthcare and improved health outcomes help prevent individuals from falling into poverty due to medical expenses.[132][133]

Hunger

[edit]

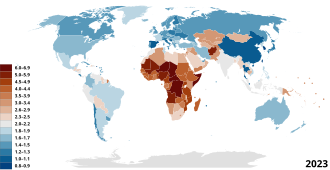

It is estimated that 1.02 billion people go to bed hungry every night.[134] According to the Global Hunger Index, Sub-Saharan Africa had the highest child malnutrition rate of the world's regions over the 2001–2006 period.[135]

Poor people spend a greater portion of their budgets on food than wealthy people and, as a result, they can be particularly vulnerable to increases in food prices. For example, in late 2007, increases in the price of grains[136] led to food riots in some countries.[137][138][139] Threats to the supply of food may also be caused by drought and the water crisis.[140] Intensive farming often leads to a vicious cycle of exhaustion of soil fertility and decline of agricultural yields.[141] Approximately 40% of the world's agricultural land is seriously degraded.[142][143] Goal 2 of the Sustainable Development Goals is the elimination of hunger and undernutrition by 2030.[144]

Mental health

[edit]

A psychological study has been conducted by four scientists during inaugural Convention of Psychological Science. The results find that people who thrive with financial stability or fall under low socioeconomic status (SES) tend to perform worse cognitively due to external pressure imposed upon them. The research found that stressors such as low income, inadequate health care, discrimination, and exposure to criminal activities all contribute to mental disorders. This study also found that children exposed to poverty-stricken environments have slower cognitive thinking.[145] It is seen that children perform better under the care of their parents and that children tend to adopt speaking language at a younger age. Since being in poverty from childhood is more harmful than it is for an adult, it is seen that children in poor households tend to fall behind in certain cognitive abilities compared to other average families.[146] The World Health Organization highlights that social determinants such as income inequality, lack of access to quality education, unemployment, insecure housing, and exposure to violence are strongly associated with poor mental health outcomes. These structural factors contribute significantly to disparities in mental well-being across different populations.[147]

For a child to grow up emotionally healthy, children under three need "A strong, reliable primary caregiver who provides consistent and unconditional love, guidance, and support. Safe, predictable, stable environments. Ten to 20 hours each week of harmonious, reciprocal interactions. This process, known as attunement, is most crucial during the first 6–24 months of infants' lives and helps them develop a wider range of healthy emotions, including gratitude, forgiveness, and empathy. Enrichment through personalized, increasingly complex activities".[citation needed]

In a 1996 survey, 67% of children from disadvantaged inner cities said they had witnessed a serious assault, and 33% reported witnessing a homicide.[148] 51% of fifth graders from New Orleans (median income for a household: $27,133) have been found to be victims of violence, compared to 32% in Washington, DC (mean income for a household: $40,127).[149] Studies have shown that poverty changes the personalities of children who live in it. The Great Smoky Mountains Study was a ten-year study that was able to demonstrate this. During the study, about one-quarter of the families saw a dramatic and unexpected increase in income. The study showed that among these children, instances of behavioral and emotional disorders decreased, and conscientiousness and agreeableness increased.[150]

Education

[edit]Research has found that there is a high risk of educational underachievement for children who are from low-income housing circumstances. This is often a process that begins in primary school. Instruction in the US educational system, as well as in most other countries, tends to be geared towards those students who come from more advantaged backgrounds. As a result, children in poverty are at a higher risk than advantaged children for retention in their grade, special deleterious placements during the school's hours and not completing their high school education.[151] Advantage breeds advantage.[152] There are many explanations for why students tend to drop out of school. One is the conditions in which they attend school. Schools in poverty-stricken areas have conditions that hinder children from learning in a safe environment. Researchers have developed a name for areas like this: an urban war zone is a poor, crime-laden district in which deteriorated, violent, even warlike conditions and underfunded, largely ineffective schools promote inferior academic performance, including irregular attendance and disruptive or non-compliant classroom behavior.[153] Because of poverty, "Students from low-income families are 2.4 times more likely to drop out than middle-income kids, and over 10 times more likely than high-income peers to drop out."[154]

For children with low resources, the risk factors are similar to others such as juvenile delinquency rates, higher levels of teenage pregnancy, and economic dependency upon their low-income parent or parents.[151] Families and society who submit low levels of investment in the education and development of less fortunate children end up with less favorable results for the children who see a life of parental employment reduction and low wages. Higher rates of early childbearing with all the connected risks to family, health and well-being are major issues to address since education from preschool to high school is identifiably meaningful in a life.[151]

Poverty often drastically affects children's success in school. A child's "home activities, preferences, mannerisms" must align with the world and in the cases that they do not do these, students are at a disadvantage in the school and, most importantly, the classroom.[155] Therefore, it is safe to state that children who live at or below the poverty level will have far less success educationally than children who live above the poverty line. Poor children have a great deal less healthcare and this ultimately results in many absences from school. Additionally, poor children are much more likely to suffer from hunger, fatigue, irritability, headaches, ear infections, flu, and colds.[155] These illnesses could potentially restrict a student's focus and concentration.[156]

In general, the interaction of gender with poverty or location tends to work to the disadvantage of girls in poorer countries with low completion rates and social expectations that they marry early, and to the disadvantage of boys in richer countries with high completion rates but social expectations that they enter the labour force early.[157] At the primary education level, most countries with a completion rate below 60% exhibit gender disparity at girls' expense, particularly poor and rural girls. In Mauritania, the adjusted gender parity index is 0.86 on average, but only 0.63 for the poorest 20%, while there is parity among the richest 20%. In countries with completion rates between 60% and 80%, gender disparity is generally smaller, but disparity at the expense of poor girls is especially marked in Cameroon, Nigeria and Yemen. Exceptions in the opposite direction are observed in countries with pastoralist economies that rely on boys' labour, such as the Kingdom of Eswatini, Lesotho and Namibia.[157]

Shelter

[edit]

The right to housing is argued to be a human right.[159][160] Higher density and lower cost housing affords low-income families and first-time homebuyers with more and less expensive shelter opportunities, reducing economic inequality.[161][162]

The geographic concentration of poverty is argued to be a factor in entrenching poverty. William J. Wilson's "concentration and isolation" hypothesis states that the economic difficulties of the very poorest African Americans are compounded by the fact that as the better-off African Americans move out, the poorest are more and more concentrated, having only other very poor people as neighbors. This concentration causes social isolation, Wilson suggests, because the very poor are now isolated from access to the job networks, role models, institutions, and other connections that might help them escape poverty.[163] Gentrification means converting an aging neighborhood into a more affluent one, as by remodeling homes. Landlords then increase rent on newly renovated real estate; the poor people cannot afford to pay high rent, and may need to leave their neighborhood to find affordable housing.[164] The poor also get more access to income and services, while studies suggest poor residents living in gentrifying neighbourhoods are actually less likely to move than poor residents of non-gentrifying areas.[165]

Poverty increases the risk of homelessness.[166] Slum-dwellers, who make up a third of the world's urban population, live in a poverty no better, if not worse, than rural people, who are the traditional focus of the poverty in the developing world, according to a report by the United Nations.[167]

There are over 100 million street children worldwide.[168] Most of the children living in institutions around the world have a surviving parent or close relative, and they most commonly entered orphanages because of poverty.[158] It is speculated that, flush with money, for-profit orphanages are increasing and push for children to join even though demographic data show that even the poorest extended families usually take in children whose parents have died.[158] Many child advocates maintain that this can harm children's development by separating them from their families and that it would be more effective and cheaper to aid close relatives who want to take in the orphans.[158]

Utilities

[edit]

The poor tend to pay more for access to utilities and ensuring the availability of water, sanitation, energy, and telecommunication services such as broadband internet service[169] help in reducing poverty in general.[170][171]

Water and sanitation

[edit]As of 2012, 2.5 billion people lack access to sanitation services and 15% practice open defecation.[172] Even while providing latrines is a challenge, people still do not use them even when available. Bangladesh had half the GDP per capita of India but has a lower mortality from diarrhea than India or the world average, with diarrhea deaths declining by 90% since the 1990s. By strategically providing pit latrines to the poorest, charities in Bangladesh sparked a cultural change as those better off perceived it as an issue of status to not use one. The vast majority of the latrines built were then not from charities but by villagers themselves.[173]

Water utility subsidies tend to subsidize water consumption by those connected to the supply grid, which is typically skewed towards the richer and urban segment of the population and those outside informal housing. As a result of heavy consumption subsidies, the price of water decreases to the extent that only 30%, on average, of the supplying costs in developing countries is covered.[174][175] This results in a lack of incentive to maintain delivery systems, leading to losses from leaks annually that are enough for 200 million people.[174][176] This also leads to a lack of incentive to invest in expanding the network, resulting in much of the poor population being unconnected to the network. Instead, the poor buy water from water vendors for, on average, about 5 to 16 times the metered price.[174][177] However, subsidies for laying new connections to the network rather than for consumption have shown more promise for the poor.[175]

Energy

[edit]

In developing countries and some areas of more developed countries, energy poverty is lack of access to modern energy services in the home.[178] In 2022, 759 million people lacked access to consistent electricity and 2.6 billion people used dangerous and inefficient cooking systems.[179] Their well-being is negatively affected by very low consumption of energy, use of dirty or polluting fuels, and excessive time spent collecting fuel to meet basic needs.

Predominant indices for measuring the complex nature of energy poverty include the Energy Development Index (EDI), the Multidimensional Energy Poverty Index (MEPI), and Energy Poverty Index (EPI). Both binary and multidimensional measures of energy poverty are required to establish indicators that simplify the process of measuring and tracking energy poverty globally.[180] Energy poverty often exacerbates existing vulnerabilities amongst underprivileged communities and negatively impacts public and household health, education, and women's opportunities.[181]

According to the Energy Poverty Action initiative of the World Economic Forum, "Access to energy is fundamental to improving quality of life and is a key imperative for economic development. In the developing world, energy poverty is still rife."[182] As a result of this situation, the United Nations (UN) launched the Sustainable Energy for All Initiative and designated 2012 as the International Year for Sustainable Energy for All, which had a major focus on reducing energy poverty.

The term energy poverty is also sometimes used in the context of developed countries to mean an inability to afford energy in the home. This concept is also known as fuel poverty, household energy insecurity or energy hardship.[178][183]Financial services

[edit]For low-income individuals and families, access to credit can be limited, predatory, or both, making it difficult to find the financial resources they need to invest in their futures.[184][185]

Prejudice and exploitation

[edit]

Cultural factors, such as discrimination of various kinds, can negatively affect productivity such as age discrimination, stereotyping,[186] discrimination against people with physical disability,[187] gender discrimination, racial discrimination, and caste discrimination. Children are more than twice as likely to live in poverty as adults.[188] Women are the group suffering from the highest rate of poverty after children, in what is referred to as the feminization of poverty. In addition, the fact that women are more likely to be caregivers, regardless of income level, to either the generations before or after them, exacerbates the burdens of their poverty.[189] Those in poverty have increased chances of incurring a disability which leads to a cycle where disability and poverty are mutually reinforcing.

Max Weber and some schools of modernization theory suggest that cultural values could affect economic success.[190][191] However, researchers[who?] have gathered evidence that suggest that values are not as deeply ingrained and that changing economic opportunities explain most of the movement into and out of poverty, as opposed to shifts in values.[192] A 2018 report on poverty in the United States by UN special rapporteur Philip Alston asserts that caricatured narratives about the rich and the poor (that "the rich are industrious, entrepreneurial, patriotic and the drivers of economic success" while "the poor are wasters, losers and scammers") are largely inaccurate, as "the poor are overwhelmingly those born into poverty, or those thrust there by circumstances largely beyond their control, such as physical or mental disabilities, divorce, family breakdown, illness, old age, unlivable wages or discrimination in the job market."[193] Societal perception of people experiencing economic difficulty has historically appeared as a conceptual dichotomy: the "good" poor (people who are physically impaired, disabled, the "ill and incurable," the elderly, pregnant women, children) vs. the "bad" poor (able-bodied, "valid" adults, most often male).[194]

According to experts, many women become victims of trafficking, the most common form of which is prostitution, as a means of survival and economic desperation.[195] Deterioration of living conditions can often compel children to abandon school to contribute to the family income, putting them at risk of being exploited.[196] For example, in Zimbabwe, a number of girls are turning to sex in return for food to survive because of the increasing poverty.[197] According to studies, as poverty decreases there will be fewer and fewer instances of violence.[198] Some data such as the UNICEF reports and also a research called "Echo of Silence" show that there is a close correlation between economic poverty and early marriage. In some developing countries, child marriage is considered an economic measure that can improve the family’s poor condition, strengthen family bonds.[199][200][201][202]

Poverty reduction

[edit]

Various poverty reduction strategies are broadly categorized based on whether they make more of the basic human needs available or whether they increase the disposable income needed to purchase those needs.[204] Some strategies such as building roads can both bring access to various basic needs, such as fertilizer or healthcare from urban areas, as well as increase incomes, by bringing better access to urban markets.[205][206]

Reducing relative poverty would also involve reducing inequality. Oxfam, among others,[207] has called for an international movement to end extreme wealth concentration arguing that the concentration of resources in the hands of the top 1% depresses economic activity and makes life harder for everyone else, particularly for those at the bottom of the economic ladder.[208][209] And they say that the gains of the world's billionaires in 2017, which amounted to $762 billion, were enough to end extreme global poverty seven times over.[210] Methods to reduce inequality and relative poverty include progressive taxation, which involves increasing tax rates on high-income earners,[211][212] wealth taxes, which involve taxing a portion of an individual's net worth above a certain threshold,[213][214][215] reducing payroll taxes, which are taxes on employees and employers and reducing this provides workers greater take-home pay and allows employers to spend more on wages and salaries,[216][217][218] and increasing the labor share, which is the proportion of business income paid as wages and salaries instead of allocated to shareholders as profit.[219][220]

Increasing the supply of basic needs

[edit]Improving technology

[edit]

Agricultural technologies such as nitrogen fertilizers, pesticides, new seed varieties and new irrigation methods have dramatically reduced food shortages in modern times by boosting yields past previous constraints.[221] Before the Industrial Revolution, poverty had been mostly accepted as inevitable as economies produced little, making wealth scarce.[222] Geoffrey Parker wrote that "In Antwerp and Lyon, two of the largest cities in western Europe, by 1600 three-quarters of the total population were too poor to pay taxes, and therefore likely to need relief in times of crisis."[223] The initial industrial revolution led to high economic growth and eliminated mass absolute poverty in what is now considered the developed world.[224] Mass production of goods in places such as rapidly industrializing China has made what were once considered luxuries, such as vehicles and computers, inexpensive and thus accessible to many who were otherwise too poor to afford them.[225][226]

Other than technology, advancements in sciences such as medicine help provide basic needs better. For example, Sri Lanka had a maternal mortality rate of 2% in the 1930s, higher than any nation today, but reduced it to 0.5–0.6% in the 1950s and to 0.6% in 2006 while spending less each year on maternal health because it learned what worked and what did not.[227][228] Knowledge on the cost effectiveness of healthcare interventions can be elusive and educational measures have been made to disseminate what works, such as the Copenhagen Consensus.[229] Cheap water filters and promoting hand washing are some of the most cost effective health interventions and can cut deaths from diarrhea and pneumonia.[230][231] Fortification with micronutrients was ranked the most cost effective aid strategy by the Copenhagen Consensus.[232] For example, iodised salt costs 2 to 3 cents per person a year while even moderate iodine deficiency in pregnancy shaves off 10 to 15 IQ points.[233]

State funding

[edit]

Certain basic needs are argued to be better provided by the state. Universal healthcare can reduce the overall cost of providing healthcare by having a single payer negotiating with healthcare providers and minimizing administrative costs.[132][133] It is also argued that subsidizing essential goods such as fuel is less efficient in helping the poor than providing that same money as income grants to the poor.[234]

Government revenue can be diverted away from basic services by corruption.[235][236] Funds from aid and natural resources are often sent by government individuals for money laundering to overseas banks which insist on bank secrecy, instead of spending on the poor.[237] A Global Witness report asked for more action from Western banks as they have proved capable of stanching the flow of funds linked to terrorism.[237]

Illicit capital flight, such as corporate tax avoidance,[238] from the developing world is estimated at ten times the size of aid it receives and twice the debt service it pays,[239] with one estimate that most of Africa would be developed if the taxes owed were paid.[240] About 60 per cent of illicit capital flight from Africa is from transfer mispricing, where a subsidiary in a developing nation sells to another subsidiary or shell company in a tax haven at an artificially low price to pay less tax.[241] An African Union report estimates that about 30% of sub-Saharan Africa's GDP has been moved to tax havens.[242] Solutions include corporate "country-by-country reporting" where corporations disclose activities in each country and thereby prohibit the use of tax havens where no effective economic activity occurs.[241]

Developing countries' debt service to banks and governments from richer countries can constrain government spending on the poor.[243] For example, Zambia spent 40% of its total budget to repay foreign debt, and only 7% for basic state services in 1997.[244] One of the proposed ways to help poor countries has been debt relief. Zambia began offering services, such as free health care even while overwhelming the health care infrastructure, because of savings that resulted from a 2005 round of debt relief.[245] Since that round of debt relief, private creditors accounted for an increasing share of poor countries' debt service obligations. This complicated efforts to renegotiate easier terms for borrowers during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic because the multiple private creditors involved say they have a fiduciary obligation to their clients such as the pension funds.[246][247]

The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, as primary holders of developing countries' debt, attach structural adjustment conditionalities in return for loans which are generally geared toward loan repayment with austerity measures such as the elimination of state subsidies and the privatization of state services. For example, the World Bank presses poor nations to eliminate subsidies for fertilizer even while many farmers cannot afford them at market prices.[248] In Malawi, almost 5 million of its 13 million people used to need emergency food aid but after the government changed policy and subsidies for fertilizer and seed were introduced, farmers produced record-breaking corn harvests in 2006 and 2007 as Malawi became a major food exporter.[248]

Distressed securities funds, also known as vulture funds, buy up the debt of poor nations cheaply and then sue countries for the full value of the debt plus interest which can be ten or 100 times what they paid.[249] They may pursue any companies which do business with their target country to force them to pay to the fund instead.[249] Considerable resources are diverted on costly court cases. For example, a court in Jersey ordered the Democratic Republic of the Congo to pay an American speculator $100 million in 2010.[249] Now, the UK, Isle of Man and Jersey have banned such payments.[249]

Improving access to available basic needs

[edit]Even with new products, such as better seeds, or greater volumes of them, such as industrial production, the poor still require access to these products. Improving road and transportation infrastructure helps solve this major bottleneck. In Africa, it costs more to move fertilizer from an African seaport 100 kilometres (60 mi) inland than to ship it from the United States to Africa because of sparse, low-quality roads, leading to fertilizer costs two to six times the world average.[250] Microfranchising models such as door-to-door distributors who earn commission-based income or Coca-Cola's successful distribution system[251][252] are used to disseminate basic needs to remote areas for below market prices.[253][254]

The loss of basic needs providers emigrating from impoverished countries has a damaging effect.[255] As of 2004, there were more Ethiopia-trained doctors living in Chicago than in Ethiopia[256] and this often leaves inadequately less skilled doctors to remain in their home countries.[257] Proposals to mitigate the problem include compulsory government service for graduates of public medical and nursing schools[255] and promoting medical tourism so that health care personnel have more incentive to practice in their home countries.[258] Telehealth is the use of telecommunication technologies to deliver health services. For remotes communities in Alaska, telehealth has been found to reduce travel costs alone for the state by $13 million in 2021[259] and, according to one study, reduced the life expectancy gap between whites and American Indian population in Alaska from eight to five years.[260]

Preventing overpopulation

[edit]

Poverty and lack of access to birth control can lead to population increases that put pressure on local economies and access to resources, amplifying other economic inequality and creating increase poverty.[261][95][262] Better education for both men and women, and more control of their lives, reduces population growth due to family planning.[263][264] According to United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), those who receive better education can earn money for their lives, thereby strengthening economic security.[265]

Increasing personal income

[edit]The following are strategies used or proposed to increase personal incomes among the poor. Raising farm incomes is described as the core of the antipoverty effort as three-quarters of the poor today are farmers.[266] Estimates show that growth in the agricultural productivity of small farmers is, on average, at least twice as effective in benefiting the poorest half of a country's population as growth generated in nonagricultural sectors.[267]

Income grants

[edit]

A guaranteed minimum income ensures that every citizen will be able to purchase a desired level of basic needs. One method is through a basic income (or negative income tax), which is a system of social security, that periodically provides each citizen, rich or poor, with a sum of money that is sufficient to live on.[268] Studies of large cash-transfer programs in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Malawi show that the programs can be effective in increasing consumption, schooling, and nutrition, whether they are tied to such conditions or not.[269][270][271]

Employment subsidies go to those already employed and this has shown to have little effect on those at the lowest income levels.[216][272][273] Proponents argue that a basic income is more efficient than a minimum wage and unemployment benefits, as the minimum wage effectively imposes a high marginal tax on employers, causing losses in efficiency. In 1968, Paul Samuelson, John Kenneth Galbraith and another 1,200 economists signed a document calling for the US Congress to introduce a system of income guarantees.[274] Winners of the Nobel Prize in Economics, with often diverse political convictions, who support a basic income include Herbert A. Simon,[275] Friedrich Hayek,[276] Robert Solow,[275] Milton Friedman,[277] Jan Tinbergen,[275] James Tobin[278][279][280] and James Meade.[275]

Income grants are argued to be vastly more efficient in extending basic needs to the poor than subsidizing supplies whose effectiveness in poverty alleviation is diluted by the non-poor who enjoy the same subsidized prices.[234] With cars and other appliances, the wealthiest 20% of Egypt uses about 93% of the country's fuel subsidies.[281] In some countries, fuel subsidies are a larger part of the budget than health and education.[281][282] A 2008 study concluded that the money spent on in-kind transfers in India in a year could lift all India's poor out of poverty for that year if transferred directly.[283] Additionally, in aid models, the famine relief model increasingly used by aid groups calls for giving cash or cash vouchers to the hungry to pay local farmers instead of buying food from donor countries, often required by law, as it wastes money on transport costs.[284][285]

The primary obstacle argued against direct cash transfers is the impractically for poor countries of such large and direct transfers. In practice, payments determined by complex iris scanning are used by war-torn Democratic Republic of Congo and Afghanistan,[286] while India modified its subsidies in favor of direct transfers.[287] Central bank digital currencies are argued to be an efficient tool in direct cash transfers to the poor as it can reach the unbanked and be more cost effective without having to physically send money and without needing an intermediary such as a bank.[288][289]

Economic freedoms

[edit]Corruption often leads to many civil services being treated by governments as employment agencies to loyal supporters[290] and so it could mean going through 20 procedures, paying $2,696 in fees, and waiting 82 business days to start a business in Bolivia, while in Canada it takes two days, two registration procedures, and $280 to do the same.[291] Such costly barriers favor big firms at the expense of small enterprises, where most jobs are created.[292] Often, businesses have to bribe government officials even for routine activities, which is, in effect, a tax on business.[293] Noted reductions in poverty in recent decades has occurred in China and India mostly as a result of the abandonment of collective farming in China and the ending of the central planning model known as the License Raj in India.[294][295][296]

The World Bank concludes that governments and feudal elites extending to the poor the right to the land that they live and use are 'the key to reducing poverty' citing that land rights greatly increase poor people's wealth, in some cases doubling it.[297] Providing secure tenure to land ownership creates incentives to improve the land and thus improves the welfare of the poor.[298] It is argued that those in power have an incentive to not secure property rights as they are able to then more easily take land or any small business that does well to their supporters.[299]

Greater access to markets brings more income to the poor. Road infrastructure has a direct impact on poverty.[300][301] Additionally, migration from poorer countries resulted in $328 billion sent from richer to poorer countries in 2010, more than double the $120 billion in official aid flows from OECD members. In 2011, India got $52 billion from its diaspora, more than it took in foreign direct investment.[302]

Financial services

[edit]

Microloans, made famous by the Grameen Bank, is where small amounts of money are loaned to borrowers who typically lack collateral, steady employment, or a verifiable credit history.. However, microlending has been criticized for making hyperprofits off the poor even from its founder, Muhammad Yunus,[303] and in India, Arundhati Roy asserts that some 250,000 debt-ridden farmers have been driven to suicide.[304][305][306]

Those in poverty place more importance on having a safe place to save money than on receiving loans.[307] Additionally, a large part of microfinance loans are spent not on investments but on products that would usually be paid by a checking or savings account.[307] A large portion of the poor are unbanked because it is often not profitable to open bank accounts for the poor. One altervative option is the postal savings system. Another option is mobile banking which utilizes the wide availability of mobile phones.[307] This usually involves a network of agents of mostly shopkeepers who would take deposits in cash and translate these onto an account on customers' phones. Cash transfers can be done between phones and issued back in cash with a small commission, making remittances safer.[308] Central bank digital currencies could allow, even in areas without internet access, digital transactions with little or no cost using simple feature phones.[288]

Education and vocational training

[edit]

Free education through public education or charitable organizations rather than through tuition, from early childhood education through the tertiary level provides children from low-income families who may not otherwise have the financial resources with better job prospects and higher earnings and promotes social mobility.[309][310][311][312] Job training and vocational education programs that target training in technical skills in specific industries or occupations that are in high demand can reduce poverty and wealth concentration.[313]

Strategies to provide education cost effectively include deworming children, which costs about 50 cents per child per year and reduces non-attendance from anemia, illness and malnutrition, while being only a twenty-fifth as expensive as increasing school attendance by constructing schools.[314] Schoolgirl absenteeism could be cut in half by simply providing free sanitary towels.[315] Paying for school meals is argued to be an efficient strategy in increasing school enrollment, reducing absenteeism and increasing student attention.[316]

Desirable actions such as enrolling children in school or receiving vaccinations can be encouraged by a form of aid known as conditional cash transfers.[317] In Mexico, for example, dropout rates of 16- to 19-year-olds in rural area dropped by 20% and children gained half an inch in height.[318] Initial fears that the program would encourage families to stay at home rather than work to collect benefits have proven to be unfounded. Instead, there is less excuse for neglectful behavior as, for example, children stopped begging on the streets instead of going to school because it could result in suspension from the program.[318]

Obstacles

[edit]Economist William Easterly diagnoses a problem with the traditional approach to poverty reduction, whose advocates he calls "Planners." He notes that $2.3 trillion were spent on foreign aid in five decades, yet twelve-cent medicines were not able to be given to children to prevent malaria-related deaths and three dollars were not given to new mothers to help prevent millions of child deaths. He argues that even though the aid was well-meaning, it failed to bring results because "Planners," and not "Searchers," are supplying it.[319]

| Planners | Searchers |

|---|---|

| Unable to motivate people to carry out their good intentions | Find ways to make things work |

| Take no responsibility for their actions | Accept responsibility |

| Determine what to supply | Find out what is in demand |

| Apply global blueprints | Adapt to local conditions |

| Lack knowledge of the bottom | Find out what the reality is at the bottom |

| Believe outsiders know enough to offer solutions | Believe that solutions must be homegrown |

Antipoverty institutions

[edit]Intergovernmental organizations

[edit]In 2015 all UN Member States adopted the 17 Sustainable Development Goals as part of the Post-2015 Development Agenda, which sought to create a future global development framework to succeed the Millennium Development Goals, which were goals set in 2000 and were meant to be achieved by 2015.[320] Most targets are to be achieved by 2030, although some have no end date.[321] Goal 1 is to "end poverty in all its forms everywhere".[322] It aims to eliminate extreme poverty for all people measured by daily wages less than $1.25 and at least half the total number of men, women, and children living in poverty. In addition, social protection systems must be established at the national level and equal access to economic resources must be ensured.[323] Strategies have to be developed at the national, regional and international levels to support the eradication of poverty.[324]

Development banks

[edit]A development financial institution, also known as a development bank, is a financial institution that provides risk capital for economic development projects on a non-commercial basis. They are often established and owned by governments to finance projects that would otherwise not be able to get financing from commercial lenders. These include international financial institutions such as the World Bank, which is the largest development bank.

Nongovernmental organizations

[edit]In recent decades, the number of nongovernmental organizations has increased dramatically. The high level forums on aid effectiveness which were coordinated by the OECD found that this leads to fragmentation where too many agencies were financing too many small projects using too many different procedures and that the civil service of the donor countries were overstretched producing reports for each.[325]

A major proportion of aid from donor nations is tied, mandating that a receiving nation spend on products and expertise originating only from the donor country.[326] US law requires food aid be spent on buying food at home, instead of where the hungry live, and, as a result, half of what is spent is used on transport.[327] Domestic NGOs have more expertise in their respective regions and have less overhead and thus tend to be more efficient in delivering aid but receive less funding. Housing only for a Western aid worker in Ethiopia is enough to pay the salaries of four or five local NGO workers, for example. Bilateral government aid programs such as US Agency for International Development aim to increase their share of funding to go through 'local partners', called 'localizing'. The obstacles include accountability where it is easier to delegate responsibility for spending on one international NGO than having to track tax payer money going to numerous smaller domestic NGOs.[328]

For-profit institutions

[edit]The Poverty industrial complex refers to for-profit companies taking over roles previously held by government agencies. The incentive for profit in such companies has been argued to interfere with efficiently providing the needed services. Aid from richer nations increasingly go through for profit institutions. Such hospitals are found to imprison patients and retain corpses for non-payment of fees.[329]

Causes

[edit]

The cause of poverty is a highly ideologically charged subject, as different causes point to different remedies. Very broadly speaking, the socialist tradition locates the roots of poverty in problems of distribution and the use of the means of production as capital benefiting individuals, and calls for redistribution of wealth as the solution, whereas the neoliberal school of thought holds that creating conditions for profitable private investment is the solution. Neoliberal think tanks have received extensive funding,[331] and proponents of neoliberalism have been able to apply their ideas in highly indebted countries in the global South as a condition for receiving emergency loans from the International Monetary Fund.

The existence of inequality is in part due to a set of self-reinforcing behaviors that all together constitute one aspect of the cycle of poverty. These behaviors, in addition to unfavorable, external circumstances, also explain the existence of the Matthew effect, which not only exacerbates existing inequality, but is more likely to make it multigenerational. Widespread, multigenerational poverty is an important contributor to civil unrest and political instability.[332] For example, Raghuram G. Rajan, former governor of the Reserve Bank of India and former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund, has blamed the ever-widening gulf between the rich and the poor, especially in the US, to be one of the main fault lines which caused the financial institutions to pump money into subprime mortgages—on political behest, as a palliative and not a remedy, for poverty—causing the subprime mortgage crisis. In Rajan's view the main cause of the increasing gap between high income and low income earners was lack of equal access to higher education for the latter.[333]

A number of articles have found linkages between poverty reduction and good governance.[334] Some find that economic growth is more impactful at reducing poverty in well governed countries.[335][336][337] Others find that there is a direct effect of governance on poverty reduction.[338][339] Research also finds that governance above a certain level contributes to poverty reduction.[340][341] Others still find a relationship between governance and poverty even controlling for economic growth, indicating an independent association.[334] A data based scientific empirical research, which studied the impact of dynastic politics on the level of poverty of the provinces, found a positive correlation between dynastic politics and poverty; i.e. the higher proportion of dynastic politicians in power in a province leads to higher poverty rate.[342] There is significant evidence that these political dynasties use their political dominance over their respective regions to enrich themselves, using methods such as graft or outright bribery of legislators.[343]

Most economic historians believe that throughout most of human history, extreme poverty was the norm for roughly 90% of the population, and only with the emergence of industrialization in the 19th century were the masses of people lifted out of it.[344][345]: 1 This narrative is advanced by, among others, Martin Ravallion,[346] Nicholas Kristof,[347] and Steven Pinker.[348]

Some academics, including Dylan Sullivan and Jason Hickel have challenged this contemporary mainstream narrative on poverty, arguing that extreme poverty was not the norm throughout human history, but emerged during "periods of severe social and economic dislocation", including high European feudalism and the apex of the Roman Empire, and that it expanded significantly after 1500 with the emergence of colonialism and the beginnings of capitalism, stating that "the expansion of the capitalist world-system caused a dramatic and prolonged process of impoverishment on a scale unparalleled in recorded history." Sullivan and Hickel assert that only with the rise of anti-colonial and socialist political movements in the 20th century did human welfare begin to see significant improvement.[344] However, all scholars and intellectuals, including Hickel, agree that the incomes of the poorest people in the world have increased since 1981.[345] Nevertheless, Sullivan and Hickel argue that poverty persists under contemporary global capitalism (in spite of it being highly productive) because masses of working people are cut off from common land and resources, have no ownership or control over the means of production, and have their labor power "appropriated by a ruling class or an external imperial power," thereby maintaining extreme inequality.[344]

Marian L. Tupy, a senior fellow of the Cato Institute, a right-libertarian think tank, criticized Hickel's claim that people before industrialization lived well without a lot of monetary income, stating that "The evidence from contemporary accounts and academic research" shows that "Compared to today, Western European living standards prior to industrialization were miserably low.", that "poverty was widespread and it was precisely the onset of industrialization and global trade … which led to poverty alleviation first in the West and then in the Rest."[349] and that both Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, while advocating for socialism, recognized that the capitalist system developing around them had improved people's material conditions.[349]

Ethics

[edit]Human rights

[edit]It is sometimes argued that poverty is a violation of human rights. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights state that “Everyone, as a member of society, has the right to social security.”[350]

Environmentalism

[edit]

The poor tend to suffer most from environmental degradation caused by reckless exploitation of natural resources by the rich.[351] For example, it is estimated that 92% of accumulated greenhouse gas emissions can be attributed to countries from the Global North while 8% of emissions are attributed to countries from the Global South.[352][353] However, developing countries suffer 99% of the casualties attributable to climate change.[354] This unfair distribution of environmental burdens and benefits has generated the global environmental justice and climate justice movement.[355]

The Brundtland Report concluded that poverty causes environmental degradation, while other theories like environmentalism of the poor conclude that the global poor may be the most important force for sustainability.[356] A 2013 World Bank report estimated that climate change was likely to hinder future attempts to reduce poverty with a 2016 UN report claiming that by 2030, an additional 122 million more people could be driven to extreme poverty because of climate change.[357] The possible impacts of a temperature rise of 2 °C include: regular food shortages in Sub-Saharan Africa; a deficiency in water availability, with droughts predicted to happen much faster and last longer;[358] degradation and loss of reefs in South East Asia, resulting in reduced fish stocks; and coastal communities and cities more vulnerable to increasingly violent storms.[359]

Green imperialism is the term used to refer to influencing poorer nations in the name of environmentalism. Green colonialism is grabbing of land in the name of environmentalism. Fortress conservation is the conservation model based on the belief that biodiversity protection is best achieved by creating protected areas in isolation from humans and this has led to the eviction of indigenous people.

Spirituality

[edit]

Among some individuals, poverty is considered a necessary or desirable condition, which must be embraced to reach certain spiritual, moral, or intellectual states. Poverty is often understood to be an essential element of renunciation in religions such as Buddhism, Hinduism (only for monks, not for lay persons) and Jainism, whilst in Christianity, in particular Roman Catholicism, it is one of the evangelical counsels. Some Christian communities, such as the Simple Way, the Bruderhof, and the Amish value voluntary poverty;[360] some even take a vow of poverty, similar to that of the traditional Catholic orders, in order to live a more complete life of discipleship.[361] Another example is mendicancy, where one chooses to rely chiefly or exclusively on alms to survive. The main aim of giving up things of the materialistic world is to withdraw oneself from sensual pleasures (as they are considered illusionary and only temporary in some religions—such as the concept of dunya in Islam).

Pope Paul VI referred to "the spirit of poverty" as a fundamental characteristic of a Christian life,[362] while Pope Benedict XVI distinguished between "poverty chosen" (the poverty of spirit proposed by Jesus), and "poverty to be fought" (unjust and imposed poverty).[363]

Voluntary poverty can also be the result of solidarity with the poor.[364] Benedict XVI considered that such solidarity is a necessary condition to fight effectively to eradicate the non-voluntary poverty.[363]

See also

[edit]- Accumulation by dispossession

- Aporophobia

- Bottom of the pyramid

- Cost of poverty

- Economic inequality

- Environmental racism

- Emotional detachment

- Cycle of poverty

- Distribution of wealth

- Food bank

- Income disparity

- In-group and out-group

- International development

- International inequality

- Involuntary unemployment

- Juvenilization of poverty

- List of countries by income inequality

- List of countries by percentage of population living in poverty

- List of sovereign states by wealth inequality

- Millennium Development Goals

- Prosperity

- Redistribution of income and wealth

- Social programs

- Social protection floor

- Social safety net

- Social stigma

- United Nations Millennium Declaration

- Universal basic income

- Working poor

- World Poverty Clock

Notes

[edit]- ^ Pope Leo XIV takes account of this definition in his work on poverty, Dilexi te (October 2025).[12]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Ending Poverty". United Nations. Archived from the original on 9 September 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Poverty | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". www.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 9 December 2019. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ Roser, Max; Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban (1 January 2019). "Global Extreme Poverty". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 30 March 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^ World Bank Group (7 October 2015). "Fragile and Conflict-Affected Countries and Situations". The World Bank Group A to Z 2016. The World Bank. pp. 60a–62. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-0484-7_fragile_and_conflict_affected. ISBN 978-1-4648-0484-7.

- ^ Milanovic, Branko (2016). Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization. Harvard University Press.

- ^ "Goal 1: End poverty in all its forms everywhere". United Nations Sustainable Development. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ Skeat, Walter (2005). An Etymological Dictionary of the English Language. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-44052-1.

- ^ Gordon, David. "Indicators of Poverty & Hunger" (PDF). United Nations. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- ^ "Poverty and Inequality Analysis". worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 3 June 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ^ a b Dvorak, Jaroslav (November 2015). "European Union Definition of Poverty". The SAGE Encyclopedia of World Poverty. doi:10.4135/9781483345727.n270. ISBN 978-1-4833-4570-3 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ EUR-Lex, Council Decision of 19 December 1984 on specific Community action to combat poverty, Decision 85/8/EEC, Article 1:2, accessed on 20 October 2025

- ^ Pope Leo XIV, Dilexi te, paragraph 13, published on 4 October 2025, accessed on 20 October 2025

- ^ "Poverty headcount ratio at $1.90 a day (2011 PPP) (% of population) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ UN declaration at World Summit on Social Development in Copenhagen in 1995

- ^ "Poverty". World Bank. Archived from the original on 30 August 2004. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ Sachs, Jeffrey D. (2005). The End of Poverty. Penguin Press. p. 416. ISBN 978-1-59420-045-8.

- ^ a b c Devichand, Mukul (2 December 2007). "When a dollar a day means 25 cents". bbcnews.com. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ Ravallion, Martin; Chen, Shaohua & Sangraula, Prem (2008). "Dollar a Day Revisited" (PDF). The World Bank. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ Ravallion, Martin; Chen, Shaohua; Sangraula, Prem (May 2008). Dollar a Day Revisited (PDF) (Report). Washington, DC: The World Bank. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ Ravallion, Martin; Chen, Shaohua; Sangraula, Prem (2009). "Dollar a day" (PDF). The World Bank Economic Review. 23 (2): 163–184. doi:10.1093/wber/lhp007. ISSN 0258-6770. S2CID 26832525. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ ""The Bank uses an updated international poverty line of US $1.90 a day, which incorporates new information on differences in the cost of living across countries (the PPP exchange rates)."". Archived from the original on 3 January 2016. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ WDI. "Societal poverty a global measure of relative poverty". Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ International Food Policy Research Institute, The World's Most Deprived. Characteristics and Causes of Extreme Poverty and Hunger Archived 23 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Washington: IFPRI Oct 2007

- ^ "Poverty Definitions". US Census Bureau. 2011. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2017.