Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Kepler space telescope

View on Wikipedia

Artist's impression of the Kepler telescope | |

| Mission type | Space telescope |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA / LASP |

| COSPAR ID | 2009-011A |

| SATCAT no. | 34380 |

| Website | www |

| Mission duration | Planned: 3.5 years Final: 9 years, 7 months, 23 days |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | Ball Aerospace & Technologies |

| Launch mass | 1,052.4 kg (2,320 lb)[1] |

| Dry mass | 1,040.7 kg (2,294 lb)[1] |

| Payload mass | 478 kg (1,054 lb)[1] |

| Dimensions | 4.7 m × 2.7 m (15.4 ft × 8.9 ft)[1] |

| Power | 1100 watts[1] |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | March 7, 2009, 03:49:57 UTC[2] |

| Rocket | Delta II (7925-10L) |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral SLC-17B |

| Contractor | United Launch Alliance |

| Entered service | May 12, 2009, 09:01 UTC |

| End of mission | |

| Deactivated | November 15, 2018 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Heliocentric |

| Regime | Earth-trailing |

| Semi-major axis | 1.0133 AU |

| Eccentricity | 0.036116 |

| Perihelion altitude | 0.97671 AU |

| Aphelion altitude | 1.0499 AU |

| Inclination | 0.4474 degrees |

| Period | 372.57 days |

| Argument of perihelion | 294.04 degrees |

| Mean anomaly | 311.67 degrees |

| Mean motion | 0.96626 deg/day |

| Epoch | January 1, 2018 (J2000: 2458119.5)[3] |

| Main telescope | |

| Type | Schmidt |

| Diameter | 0.95 m (3.1 ft) |

| Collecting area | 0.708 m2 (7.62 sq ft)[A] |

| Wavelengths | 430–890 nm[3] |

| Transponders | |

| Bandwidth | X band up: 7.8 bit/s – 2 kbit/s[3] X band down: 10 bit/s – 16 kbit/s[3] Ka band down: Up to 4.3 Mbit/s[3] |

| |

The Kepler space telescope is an inactive space telescope launched by NASA in 2009[5] to discover Earth-sized planets orbiting other stars.[6][7] Named after astronomer Johannes Kepler,[8] the spacecraft was launched into an Earth-trailing heliocentric orbit. The principal investigator was William J. Borucki. After nine and a half years of operation, the telescope's reaction control system fuel was depleted, and NASA announced its retirement on October 30, 2018.[9][10]

Designed to survey a portion of Earth's region of the Milky Way to discover Earth-size exoplanets in or near habitable zones and to estimate how many of the billions of stars in the Milky Way have such planets,[6][11][12] Kepler's sole scientific instrument is a photometer that continually monitored the brightness of approximately 150,000 main sequence stars in a fixed field of view.[13] These data were transmitted to Earth, then analyzed to detect periodic dimming caused by exoplanets that cross in front of their host star. Only planets whose orbits are seen edge-on from Earth could be detected. Kepler observed 530,506 stars, and had detected 2,778 confirmed planets as of June 16, 2023.[14][15]

History

[edit]Pre-launch development

[edit]The Kepler space telescope was part of NASA's Discovery Program of relatively low-cost science missions. The telescope's construction and initial operation were managed by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, with Ball Aerospace responsible for developing the Kepler flight system.[16]

In January 2006, the project's launch was delayed eight months because of budget cuts and consolidation at NASA.[17] It was delayed again by four months in March 2006 due to fiscal problems.[17] During this time, the high-gain antenna was changed from a design using a gimbal to one fixed to the frame of the spacecraft to reduce cost and complexity, at the cost of one observation day per month.[18]

Post launch

[edit]The Ames Research Center was responsible for the ground system development, mission operations since December 2009, and scientific data analysis. The initial planned lifetime was three and a half years,[19] but greater-than-expected noise in the data, from both the stars and the spacecraft, meant additional time was needed to fulfill all mission goals. Initially, in 2012, the mission was expected to be extended until 2016,[20] but on July 14, 2012, one of the four reaction wheels used for pointing the spacecraft stopped turning, and completing the mission would only be possible if the other three all remained reliable.[21] Then, on May 11, 2013, a second one failed, disabling the collection of science data[22] and threatening the continuation of the mission.[23]

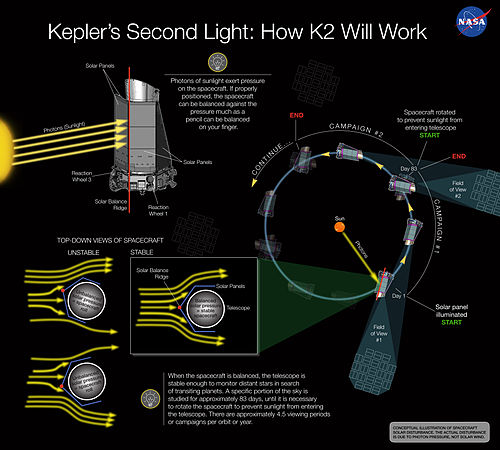

On August 15, 2013, NASA announced that they had given up trying to fix the two failed reaction wheels. This meant the current mission needed to be modified, but it did not necessarily mean the end of planet hunting. NASA had asked the space science community to propose alternative mission plans "potentially including an exoplanet search, using the remaining two good reaction wheels and thrusters".[24][25][26][27] On November 18, 2013, the K2 "Second Light" proposal was reported. This would include utilizing the disabled Kepler in a way that could detect habitable planets around smaller, dimmer red dwarfs.[28][29][30][31] On May 16, 2014, NASA announced the approval of the K2 extension.[32]

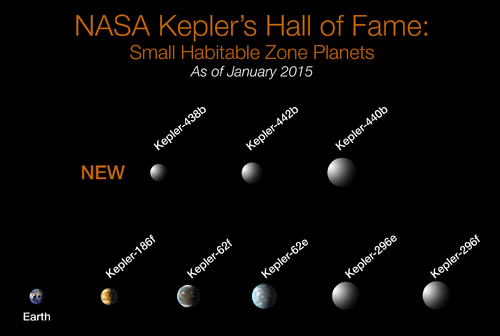

By January 2015, Kepler and its follow-up observations had found 1,013 confirmed exoplanets in about 440 star systems, along with a further 3,199 unconfirmed planet candidates.[B][33][34] Four planets have been confirmed through Kepler's K2 mission.[35] In November 2013, astronomers estimated, based on Kepler space mission data, that there could be as many as 40 billion rocky Earth-size exoplanets orbiting in the habitable zones of Sun-like stars and red dwarfs within the Milky Way.[36][37][38] It is estimated that 11 billion of these planets may be orbiting Sun-like stars.[39] The nearest such planet may be 3.7 parsecs (12 ly) away, according to the scientists.[36][37]

On January 6, 2015, NASA announced the 1,000th confirmed exoplanet discovered by the Kepler space telescope. Four of the newly confirmed exoplanets were found to orbit within habitable zones of their related stars: three of the four, Kepler-438b, Kepler-442b and Kepler-452b, are almost Earth-size and likely rocky; the fourth, Kepler-440b, is a super-Earth.[40] On May 10, 2016, NASA verified 1,284 new exoplanets found by Kepler, the single largest finding of planets to date.[41][42][43]

Kepler data have also helped scientists observe and understand supernovae; measurements were collected every half-hour so the light curves were especially useful for studying these types of astronomical events.[44]

On October 30, 2018, after the spacecraft ran out of fuel, NASA announced that the telescope would be retired.[45] The telescope was shut down the same day, bringing an end to its nine-year service. Kepler observed 530,506 stars and discovered 2,662 exoplanets over its lifetime.[15] A newer NASA mission, TESS, launched in 2018, is continuing the search for exoplanets.[46]

Spacecraft design

[edit]

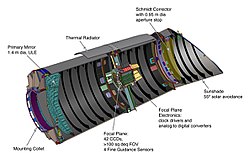

The telescope has a mass of 1,039 kilograms (2,291 lb) and contains a Schmidt camera with a 0.95-meter (37.4 in) front corrector plate (lens) feeding a 1.4-meter (55 in) primary mirror—at the time of its launch this was the largest mirror on any telescope outside Earth orbit,[47] though the Herschel Space Observatory took this title a few months later. Its telescope has a 115 deg2 (about 12-degree diameter) field of view (FoV), roughly equivalent to the size of one's fist held at arm's length. Of this, 105 deg2 is of science quality, with less than 11% vignetting. The photometer has a soft focus to provide excellent photometry, rather than sharp images. The mission goal was a combined differential photometric precision (CDPP) of 20 ppm for a m(V)=12 Sun-like star for a 6.5-hour integration, though the observations fell short of this objective (see mission status).

Camera

[edit]

The focal plane of the spacecraft's camera is made out of forty-two 50 × 25 mm (2 × 1 in) CCDs at 2200×1024 pixels each, possessing a total resolution of 94.6 megapixels,[48][49] which at the time made it the largest camera system launched into space.[19] The array was cooled by heat pipes connected to an external radiator.[1] The CCDs were read out every 6.5 seconds (to limit saturation) and co-added on board for 58.89 seconds for short cadence targets, and 1765.5 seconds (29.4 minutes) for long cadence targets.[50] Due to the larger bandwidth requirements for the former, these were limited in number to 512 compared to 170,000 for long cadence. However, even though at launch Kepler had the highest data rate of any NASA mission,[citation needed] the 29-minute sums of all 95 million pixels constituted more data than could be stored and sent back to Earth. Therefore, the science team pre-selected the relevant pixels associated with each star of interest, amounting to about 6 percent of the pixels (5.4 megapixels). The data from these pixels was then requantized, compressed and stored, along with other auxiliary data, in the on-board 16 gigabyte solid-state recorder. Data that was stored and downlinked includes science stars, p-mode stars, smear, black level, background and full field-of-view images.[1][51]

Primary mirror

[edit]

The Kepler primary mirror is 1.4 meters (4.6 ft) in diameter. Manufactured by glass maker Corning using ultra-low expansion (ULE) glass, the mirror is specifically designed to have a mass only 14% that of a solid mirror of the same size.[52][53] To produce a space telescope system with sufficient sensitivity to detect relatively small planets, as they pass in front of stars, a very high reflectance coating on the primary mirror was required. Using ion assisted evaporation, Surface Optics Corp. applied a protective nine-layer silver coating to enhance reflection and a dielectric interference coating to minimize the formation of color centers and atmospheric moisture absorption.[54][55]

Photometric performance

[edit]In terms of photometric performance, Kepler worked well, much better than any Earth-bound telescope, but short of design goals. The objective was a combined differential photometric precision (CDPP) of 20 parts per million (PPM) on a magnitude 12 star for a 6.5-hour integration. This estimate was developed allowing 10 ppm for stellar variability, roughly the value for the Sun. The obtained accuracy for this observation has a wide range, depending on the star and position on the focal plane, with a median of 29 ppm. Most of the additional noise appears to be due to a larger-than-expected variability in the stars themselves (19.5 ppm as opposed to the assumed 10.0 ppm), with the rest due to instrumental noise sources slightly larger than predicted.[56][48]

Because decrease in brightness from an Earth-size planet transiting a Sun-like star is so small, only 80 ppm, the increased noise means each individual transit is only a 2.7 σ event, instead of the intended 4 σ. This, in turn, means more transits must be observed to be sure of a detection. Scientific estimates indicated that a mission lasting 7 to 8 years, as opposed to the originally planned 3.5 years, would be needed to find all transiting Earth-sized planets.[57] On April 4, 2012, the Kepler mission was approved for extension through the fiscal year 2016,[20][58] but this also depended on all remaining reaction wheels staying healthy, which turned out not to be the case (see Reaction wheel issues below).

Orbit and orientation

[edit]

Kepler orbits the Sun,[59][60] which avoids Earth occultations, stray light, and gravitational perturbations and torques inherent in an Earth orbit.

NASA has characterized Kepler's orbit as "Earth-trailing".[61] With an orbital period of 372.5 days, Kepler is slowly falling farther behind Earth (about 16 million miles per annum). As of May 1, 2018[update], the distance to Kepler from Earth was about 0.917 AU (137 million km).[3] This means that after about 26 years Kepler will reach the other side of the Sun and will get back to the neighborhood of the Earth after 51 years.

Until 2013 the photometer pointed to a field in the northern constellations of Cygnus, Lyra and Draco, which is well out of the ecliptic plane, so that sunlight never enters the photometer as the spacecraft orbits.[1] This is also the direction of the Solar System's motion around the center of the galaxy. Thus, the stars which Kepler observed are roughly the same distance from the Galactic Center as the Solar System, and also close to the galactic plane. This fact is important if position in the galaxy is related to habitability, as suggested by the Rare Earth hypothesis.

Orientation is three-axis stabilized by sensing rotations using fine-guidance sensors located on the instrument focal plane (instead of rate sensing gyroscopes, e.g. as used on Hubble).[1] and using reaction wheels and hydrazine thrusters[62] to control the orientation.

Operations

[edit]

Kepler was operated out of Boulder, Colorado, by the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) under contract to Ball Aerospace & Technologies. The spacecraft's solar array was rotated to face the Sun at the solstices and equinoxes, so as to optimize the amount of sunlight falling on the solar array and to keep the heat radiator pointing towards deep space.[1] Together, LASP and Ball Aerospace controlled the spacecraft from a mission operations center located on the research campus of the University of Colorado. LASP performs essential mission planning and the initial collection and distribution of the science data. The mission's initial life-cycle cost was estimated at US$600 million, including funding for 3.5 years of operation.[1] In 2012, NASA announced that the Kepler mission would be funded until 2016 at a cost of about $20 million per year.[20]

Communications

[edit]NASA contacted the spacecraft using the X band communication link twice a week for command and status updates. Scientific data are downloaded once a month using the Ka band link at a maximum data transfer rate of approximately 550 kB/s. The high gain antenna is not steerable so data collection is interrupted for a day to reorient the whole spacecraft and the high gain antenna for communications to Earth.[1]: 16 Kepler was the first mission to rely on Ka-band data downlink, and in turn collected statistics on Ka-band performance for later missions using this technology.[63]

The Kepler space telescope conducted its own partial analysis on board and only transmitted scientific data deemed necessary to the mission in order to conserve bandwidth.[64]

Data management

[edit]Science data telemetry collected during mission operations at LASP is sent for processing to the Kepler Data Management Center (DMC) which is located at the Space Telescope Science Institute on the campus of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. The science data telemetry is decoded and processed into uncalibrated FITS-format science data products by the DMC, which are then passed along to the Science Operations Center (SOC) at NASA Ames Research Center, for calibration and final processing. The SOC at NASA Ames Research Center (ARC) develops and operates the tools needed to process scientific data for use by the Kepler Science Office (SO). Accordingly, the SOC develops the pipeline data processing software based on scientific algorithms developed jointly by the SO and SOC. During operations, the SOC:[65]

- Receives uncalibrated pixel data from the DMC

- Applies the analysis algorithms to produce calibrated pixels and light curves for each star

- Performs transit searches for detection of planets (threshold-crossing events, or TCEs)

- Performs data validation of candidate planets by evaluating various data products for consistency as a way to eliminate false positive detections

The SOC also evaluates the photometric performance on an ongoing basis and provides the performance metrics to the SO and Mission Management Office. Finally, the SOC develops and maintains the project's scientific databases, including catalogs and processed data. The SOC finally returns calibrated data products and scientific results back to the DMC for long-term archiving, and distribution to astronomers around the world through the Multimission Archive at STScI (MAST).

Reaction wheel failures

[edit]On July 14, 2012, one of the four reaction wheels used for fine pointing of the spacecraft failed.[66] While Kepler requires only three reaction wheels to accurately aim the telescope, another failure would leave the spacecraft unable to aim at its original field.[67]

After showing some problems in January 2013, a second reaction wheel failed on May 11, 2013, ending Kepler's primary mission. The spacecraft was put into safe mode, then from June to August 2013 a series of engineering tests were done to try to recover either failed wheel. By August 15, 2013, it was decided that the wheels were unrecoverable,[24][25][26] and an engineering report was ordered to assess the spacecraft's remaining capabilities.[24]

This effort ultimately led to the "K2" follow-on mission observing different fields near the ecliptic.

The reaction wheel failures were traced back to pitting caused by arcing between the steel ball bearings in the reaction wheel. The arcing was in turn caused by coronal mass ejections (CMEs) from the sun. Kepler's position far from Earth helped in determining the cause, due to the significant delay between the arrival of a CME at Kepler and Earth.[68]

Operational timeline

[edit]

In January 2006, the project's launch was delayed eight months because of budget cuts and consolidation at NASA.[17] It was delayed again by four months in March 2006 due to fiscal problems.[17] At this time, the high-gain antenna was changed from a gimballed design to one fixed to the frame of the spacecraft to reduce cost and complexity, at the cost of one observation day per month.

The Kepler observatory was launched on March 7, 2009, at 03:49:57 UTC aboard a Delta II rocket from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida.[2][5] The launch was a success and all three stages were completed by 04:55 UTC. The cover of the telescope was jettisoned on April 7, 2009, and the first light images were taken on the next day.[69][70]

On April 20, 2009, it was announced that the Kepler science team had concluded that further refinement of the focus would dramatically increase the scientific return.[71] On April 23, 2009, it was announced that the focus had been successfully optimized by moving the primary mirror 40 micrometers (1.6 thousandths of an inch) towards the focal plane and tilting the primary mirror 0.0072 degree.[72]

On May 13, 2009, at 00:01 UTC, Kepler successfully completed its commissioning phase and began its search for planets around other stars.[73][74]

On June 19, 2009, the spacecraft successfully sent its first science data to Earth. It was discovered that Kepler had entered safe mode on June 15. A second safe mode event occurred on July 2. In both cases the event was triggered by a processor reset. The spacecraft resumed normal operation on July 3 and the science data that had been collected since June 19 was downlinked that day.[75] On October 14, 2009, the cause of these safing events was determined to be a low voltage power supply that provides power to the RAD750 processor.[76] On January 12, 2010, one portion of the focal plane transmitted anomalous data, suggesting a problem with focal plane MOD-3 module, covering two out of Kepler's 42 CCDs. As of October 2010[update], the module was described as "failed", but the coverage still exceeded the science goals.[77]

Kepler downlinked roughly twelve gigabytes of data[78] about once per month.[79]

Field of view

[edit]

Kepler has a fixed field of view (FOV) against the sky. The diagram to the right shows the celestial coordinates and where the detector fields are located, along with the locations of a few bright stars with celestial north at the top left corner. The mission website has a calculator[80] that will determine if a given object falls in the FOV, and if so, where it will appear in the photo detector output data stream. Data on exoplanet candidates is submitted to the Kepler Follow-up Program, or KFOP, to conduct follow-up observations.

Kepler's field of view covers 115 square degrees, around 0.25 percent of the sky, or "about two scoops of the Big Dipper". Thus, it would require around 400 Kepler-like telescopes to cover the whole sky.[81] The Kepler field contains portions of the constellations Cygnus, Lyra, and Draco.

The nearest star system in Kepler's field of view is the triple star system Gliese 1245, 15 light years from the Sun. The brown dwarf WISE J2000+3629, 22.8 ± 1 light years from the Sun is also in the field of view, but is invisible to Kepler due to emitting light primarily in infrared wavelengths.

Objectives and methods

[edit]The scientific objective of the Kepler space telescope was to explore the structure and diversity of planetary systems.[82] This spacecraft observes a large sample of stars to achieve several key goals:

- To determine how many Earth-size and larger planets there are in or near the habitable zone (often called "Goldilocks planets")[83] of a wide variety of spectral types of stars.

- To determine the range of size and shape of the orbits of these planets.

- To estimate how many planets there are in multiple-star systems.

- To determine the range of orbit size, brightness, size, mass and density of short-period giant planets.

- To identify additional members of each discovered planetary system using other techniques.

- Determine the properties of those stars that harbor planetary systems.

Most of the exoplanets previously detected by other projects were giant planets, mostly the size of Jupiter and bigger. Kepler was designed to look for planets 30 to 600 times less massive, closer to the order of Earth's mass (Jupiter is 318 times more massive than Earth). The method used, the transit method, involves observing repeated transit of planets in front of their stars, which causes a slight reduction in the star's apparent magnitude, on the order of 0.01% for an Earth-size planet. The degree of this reduction in brightness can be used to deduce the diameter of the planet, and the interval between transits can be used to deduce the planet's orbital period, from which estimates of its orbital semi-major axis (using Kepler's laws) and its temperature (using models of stellar radiation) can be calculated.[citation needed]

The probability of a random planetary orbit being along the line-of-sight to a star is the diameter of the star divided by the diameter of the orbit.[84] For an Earth-size planet at 1 AU transiting a Sun-like star the probability is 0.47%, or about 1 in 210.[84] For a planet like Venus orbiting a Sun-like star the probability is slightly higher, at 0.65%;[84] If the host star has multiple planets, the probability of additional detections is higher than the probability of initial detection assuming planets in a given system tend to orbit in similar planes—an assumption consistent with current models of planetary system formation.[84] For instance, if a Kepler-like mission conducted by aliens observed Earth transiting the Sun, there is a 7% chance that it would also see Venus transiting.[84]

Kepler's 115 deg2 field of view gives it a much higher probability of detecting Earth-sized planets than the Hubble Space Telescope, which has a field of view of only 10 sq. arc-minutes. Moreover, Kepler is dedicated to detecting planetary transits, while the Hubble Space Telescope is used to address a wide range of scientific questions, and rarely looks continuously at just one starfield. Of the approximately half-million stars in Kepler's field of view, around 150,000 stars were selected for observation. More than 90,000 are G-type stars on, or near, the main sequence. Thus, Kepler was designed to be sensitive to wavelengths of 400–865 nm where brightness of those stars peaks. Most of the stars observed by Kepler have apparent visual magnitude between 14 and 16 but the brightest observed stars have apparent visual magnitude of 8 or lower. Most of the planet candidates were initially not expected to be confirmed due to being too faint for follow-up observations.[85] All the selected stars are observed simultaneously, with the spacecraft measuring variations in their brightness every thirty minutes. This provides a better chance for seeing a transit. The mission was designed to maximize the probability of detecting planets orbiting other stars.[1][86]

Because Kepler must observe at least three transits to confirm that the dimming of a star was caused by a transiting planet, and because larger planets give a signal that is easier to check, scientists expected the first reported results to be larger Jupiter-size planets in tight orbits. The first of these were reported after only a few months of operation. Smaller planets, and planets farther from their sun would take longer, and discovering planets comparable to Earth were expected to take three years or longer.[59]

Data collected by Kepler is also being used for studying variable stars of various types and performing asteroseismology,[87] particularly on stars showing solar-like oscillations.[88]

Planet finding process

[edit]Finding planet candidates

[edit]

Once Kepler has collected and sent back the data, raw light curves are constructed. Brightness values are then adjusted to take the brightness variations due to the rotation of the spacecraft into account. The next step is processing (folding) light curves into a more easily observable form and letting software select signals that seem potentially transit-like. At this point, any signal that shows potential transit-like features is called a threshold crossing event. These signals are individually inspected in two inspection rounds, with the first round taking only a few seconds per target. This inspection eliminates erroneously selected non-signals, signals caused by instrumental noise and obvious eclipsing binaries.[89]

Threshold crossing events that pass these tests are called Kepler Objects of Interest (KOI), receive a KOI designation and are archived. KOIs are inspected more thoroughly in a process called dispositioning. Those which pass the dispositioning are called Kepler planet candidates. The KOI archive is not static, meaning that a Kepler candidate could end up in the false-positive list upon further inspection. In turn, KOIs that were mistakenly classified as false positives could end up back in the candidates list.[90]

Not all the planet candidates go through this process. Circumbinary planets do not show strictly periodic transits, and have to be inspected through other methods. In addition, third-party researchers use different data-processing methods, or even search planet candidates from the unprocessed light curve data. As a consequence, those planets may be missing KOI designation.

Confirming planet candidates

[edit]

Once suitable candidates have been found from Kepler data, it is necessary to rule out false positives with follow-up tests.

Usually, Kepler candidates are imaged individually with more-advanced ground-based telescopes in order to resolve any background objects which could contaminate the brightness signature of the transit signal.[92] Another method to rule out planet candidates is astrometry for which Kepler can collect good data even though doing so was not a design goal. While Kepler cannot detect planetary-mass objects with this method, it can be used to determine if the transit was caused by a stellar-mass object.[93]

Through other detection methods

[edit]There are a few different exoplanet detection methods which help to rule out false positives by giving further proof that a candidate is a real planet. One of the methods, called doppler spectroscopy, requires follow-up observations from ground-based telescopes. This method works well if the planet is massive or is located around a relatively bright star. While current spectrographs are insufficient for confirming planetary candidates with small masses around relatively dim stars, this method can be used to discover additional massive non-transiting planet candidates around targeted stars.[citation needed]

In multiplanetary systems, planets can often be confirmed through transit timing variation by looking at the time between successive transits, which may vary if planets are gravitationally perturbed by each other. This helps to confirm relatively low-mass planets even when the star is relatively distant. Transit timing variations indicate that two or more planets belong to the same planetary system. There are even cases where a non-transiting planet is also discovered in this way.[94]

Circumbinary planets show much larger transit timing variations between transits than planets gravitationally disturbed by other planets. Their transit duration times also vary significantly. Transit timing and duration variations for circumbinary planets are caused by the orbital motion of the host stars, rather than by other planets.[95] In addition, if the planet is massive enough, it can cause slight variations of the host stars' orbital periods. Despite being harder to find circumbinary planets due to their non-periodic transits, it is much easier to confirm them, as timing patterns of transits cannot be mimicked by an eclipsing binary or a background star system.[96]

In addition to transits, planets orbiting around their stars undergo reflected-light variations—like the Moon, they go through phases from full to new and back again. Because Kepler cannot resolve the planet from the star, it sees only the combined light, and the brightness of the host star seems to change over each orbit in a periodic manner. Although the effect is small—the photometric precision required to see a close-in giant planet is about the same as to detect an Earth-sized planet in transit across a solar-type star—Jupiter-sized planets with an orbital period of a few days or less are detectable by sensitive space telescopes such as Kepler. In the long run, this method may help find more planets than the transit method, because the reflected light variation with orbital phase is largely independent of the planet's orbital inclination, and does not require the planet to pass in front of the disk of the star. In addition, the phase function of a giant planet is also a function of its thermal properties and atmosphere, if any. Therefore, the phase curve may constrain other planetary properties, such as the particle size distribution of the atmospheric particles.[97]

Kepler's photometric precision is often high enough to observe a star's brightness changes caused by doppler beaming or a star's shape deformation by a companion. These can sometimes be used to rule out hot Jupiter candidates as false positives caused by a star or a brown dwarf when these effects are too noticeable.[98] However, there are some cases where such effects are detected even by planetary-mass companions such as TrES-2b.[99]

Through validation

[edit]If a planet cannot be detected through at least one of the other detection methods, it can be confirmed by determining if the possibility of a Kepler candidate being a real planet is significantly larger than any false-positive scenarios combined. One of the first methods was to see if other telescopes can see the transit as well. The first planet confirmed through this method was Kepler-22b which was also observed with the Spitzer Space Telescope in addition to analyzing any other false-positive possibilities.[100] Such confirmation is costly, as small planets can generally be detected only with space telescopes.

In 2014, a new confirmation method called "validation by multiplicity" was announced. From the planets previously confirmed through various methods, it was found that planets in most planetary systems orbit in a relatively flat plane, similar to the planets found in the Solar System. This means that if a star has multiple planet candidates, it is very likely a real planetary system.[101] Transit signals still need to meet several criteria which rule out false-positive scenarios. For instance, it has to have considerable signal-to-noise ratio, it has at least three observed transits, orbital stability of those systems have to be stable and transit curve has to have a shape that partly eclipsing binaries could not mimic the transit signal. In addition, its orbital period needs to be 1.6 days or longer to rule out common false positives caused by eclipsing binaries.[102] Validation by multiplicity method is very efficient and allows to confirm hundreds of Kepler candidates in a relatively short amount of time.

A new validation method using a tool called PASTIS has been developed. It makes it possible to confirm a planet even when only a single candidate transit event for the host star has been detected. A drawback of this tool is that it requires a relatively high signal-to-noise ratio from Kepler data, so it can mainly confirm only larger planets or planets around quiet and relatively bright stars. Currently, the analysis of Kepler candidates through this method is underway.[103] PASTIS was first successful for validating the planet Kepler-420b.[104]

K2 Extension

[edit]

In April 2012, an independent panel of senior NASA scientists recommended that the Kepler mission be continued through 2016. According to the senior review, Kepler observations needed to continue until at least 2015 to achieve all the stated scientific goals.[105] On November 14, 2012, NASA announced the completion of Kepler's primary mission, and the beginning of its extended mission, which ended in 2018 when it ran out of fuel.[106]

Reaction wheel issues

[edit]In July 2012, one of Kepler's four reaction wheels (wheel 2) failed.[24] On May 11, 2013, a second wheel (wheel 4) failed, jeopardizing the continuation of the mission, as three wheels are necessary for its planet hunting.[22][23] Kepler had not collected science data since May because it was not able to point with sufficient accuracy.[107] On July 18 and 22 reaction wheels 4 and 2 were tested respectively; wheel 4 only rotated counter-clockwise but wheel 2 ran in both directions, albeit with significantly elevated friction levels.[108] A further test of wheel 4 on July 25 managed to achieve bi-directional rotation.[109] Both wheels, however, exhibited too much friction to be useful.[26] On August 2, NASA put out a call for proposals to use the remaining capabilities of Kepler for other scientific missions. Starting on August 8, a full systems evaluation was conducted. It was determined that wheel 2 could not provide sufficient precision for scientific missions and the spacecraft was returned to a "rest" state to conserve fuel.[24] Wheel 4 was previously ruled out because it exhibited higher friction levels than wheel 2 in previous tests.[109] Sending astronauts to fix Kepler is not an option because it orbits the Sun and is millions of kilometers from Earth.[26]

On August 15, 2013, NASA announced that Kepler would not continue searching for planets using the transit method after attempts to resolve issues with two of the four reaction wheels failed.[24][25][26] An engineering report was ordered to assess the spacecraft's capabilities, its two good reaction wheels and its thrusters.[24] Concurrently, a scientific study was conducted to determine whether enough knowledge can be obtained from Kepler's limited scope to justify its $18 million per year cost.

Possible ideas included searching for asteroids and comets, looking for evidence of supernovas, and finding huge exoplanets through gravitational microlensing.[26] Another proposal was to modify the software on Kepler to compensate for the disabled reaction wheels. Instead of the stars being fixed and stable in Kepler's field of view, they will drift. Proposed software was to track this drift and more or less completely recover the mission goals despite being unable to hold the stars in a fixed view.[110]

Previously collected data continued to be analyzed.[111]

Second Light (K2)

[edit]In November 2013, a new mission plan named K2 "Second Light" was presented for consideration.[29][30][31][112] K2 would involve using Kepler's remaining capability, photometric precision of about 300 parts per million, compared with about 20 parts per million earlier, to collect data for the study of "supernova explosions, star formation and Solar-System bodies such as asteroids and comets, ... " and for finding and studying more exoplanets.[29][30][112] In this proposed mission plan, Kepler would search a much larger area in the plane of Earth's orbit around the Sun.[29][30][112] Celestial objects, including exoplanets, stars and others, detected by the K2 mission would be associated with the EPIC acronym, standing for Ecliptic Plane Input Catalog.

In early 2014, the spacecraft underwent successful testing for the K2 mission.[114] From March to May 2014, data from a new field called Field 0 was collected as a testing run.[115] On May 16, 2014, NASA announced the approval of extending the Kepler mission to the K2 mission.[32] Kepler's photometric precision for the K2 mission was estimated to be 50 ppm on a magnitude 12 star for a 6.5-hour integration.[116] In February 2014, photometric precision for the K2 mission using two-wheel, fine-point precision operations was measured as 44 ppm on magnitude 12 stars for a 6.5-hour integration. The analysis of these measurements by NASA suggests the K2 photometric precision approaches that of the Kepler archive of three-wheel, fine-point precision data.[117]

On May 29, 2014, campaign fields 0 to 13 were reported and described in detail.[118]

Field 1 of the K2 mission is set towards the Leo-Virgo region of the sky, while Field 2 is towards the "head" area of Scorpius and includes two globular clusters, Messier 4 and Messier 80,[119] and part of the Scorpius–Centaurus association, which is only about 11 million years old[120] and 120–140 parsecs (380–470 ly) distant[121] with probably over 1,000 members.[122]

On December 18, 2014, NASA announced that the K2 mission had detected its first confirmed exoplanet, a super-Earth named HIP 116454 b. Its signature was found in a set of engineering data meant to prepare the spacecraft for the full K2 mission. Radial velocity follow-up observations were needed as only a single transit of the planet was detected.[123]

During a scheduled contact on April 7, 2016, Kepler was found to be operating in emergency mode, the lowest operational and most fuel intensive mode. Mission operations declared a spacecraft emergency, which afforded them priority access to NASA's Deep Space Network.[124][125] By the evening of April 8 the spacecraft had been upgraded to safe mode, and on April 10 it was placed into point-rest state,[126] a stable mode which provides normal communication and the lowest fuel burn.[124] At that time, the cause of the emergency was unknown, but it was not believed that Kepler's reaction wheels or a planned maneuver to support K2's Campaign 9 were responsible. Operators downloaded and analyzed engineering data from the spacecraft, with the prioritization of returning to normal science operations.[124][127] Kepler was returned to science mode on April 22.[128] The emergency caused the first half of Campaign 9 to be shortened by two weeks.[129]

In June 2016, NASA announced a K2 mission extension of three additional years, beyond the expected exhaustion of on-board fuel in 2018.[130] In August 2018, NASA roused the spacecraft from sleep mode, applied a modified configuration to deal with thruster problems that degraded pointing performance, and began collecting scientific data for the 19th observation campaign, finding that the onboard fuel was not yet utterly exhausted.[131]

On October 30, 2018, NASA announced that the spacecraft was out of fuel and its mission was officially ended.[132]

Mission results

[edit]

The Kepler space telescope was in active operation from 2009 through 2013, with the first main results announced on January 4, 2010. As expected, the initial discoveries were all short-period planets. As the mission continued, additional longer-period candidates were found. As of November 2018[update], Kepler has discovered 5,011 exoplanet candidates and 2,662 confirmed exoplanets.[133] [134] As of August 2022, 2,056 exoplanet candidates remain to be confirmed and 2,711 are now confirmed exoplanets.[135]

2009

[edit]NASA held a press conference to discuss early science results of the Kepler mission on August 6, 2009.[136] At this press conference, it was revealed that Kepler had confirmed the existence of the previously known transiting exoplanet HAT-P-7b, and was functioning well enough to discover Earth-size planets.[137][138]

Because Kepler's detection of planets depends on seeing very small changes in brightness, stars that vary in brightness by themselves (variable stars) are not useful in this search.[79] From the first few months of data, Kepler scientists determined that about 7,500 stars from the initial target list are such variable stars. These were dropped from the target list, and replaced by new candidates. On November 4, 2009, the Kepler project publicly released the light curves of the dropped stars.[139] The first new planet candidate observed by Kepler was originally marked as a false positive because of uncertainties in the mass of its parent star. However, it was confirmed ten years later and is now designated Kepler-1658b.[140][141]

The first six weeks of data revealed five previously unknown planets, all very close to their stars.[142][143] Among the notable results are one of the least dense planets yet found,[144] two low-mass white dwarfs[145] that were initially reported as being members of a new class of stellar objects,[146] and Kepler-16b, a well-characterized planet orbiting a binary star.

2010

[edit]On June 15, 2010, the Kepler mission released data on all but 400 of the ~156,000 planetary target stars to the public. 706 targets from this first data set have viable exoplanet candidates, with sizes ranging from as small as Earth to larger than Jupiter. The identity and characteristics of 306 of the 706 targets were given. The released targets included five[citation needed] candidate multi-planet systems, including six extra exoplanet candidates.[147] Only 33.5 days of data were available for most of the candidates.[147] NASA also announced data for another 400 candidates were being withheld to allow members of the Kepler team to perform follow-up observations.[148] The data for these candidates was published February 2, 2011.[149] (See the Kepler results for 2011 below.)

The Kepler results, based on the candidates in the list released in 2010, implied that most candidate planets have radii less than half that of Jupiter. The results also imply that small candidate planets with periods less than thirty days are much more common than large candidate planets with periods less than thirty days and that the ground-based discoveries are sampling the large-size tail of the size distribution.[147] This contradicted older theories which had suggested small and Earth-size planets would be relatively infrequent.[150][151] Based on extrapolations from the Kepler data, an estimate of around 100 million habitable planets in the Milky Way may be realistic.[152] Some media reports of the TED talk have led to the misunderstanding that Kepler had actually found these planets. This was clarified in a letter to the Director of the NASA Ames Research Center, for the Kepler Science Council dated August 2, 2010 states, "Analysis of the current Kepler data does not support the assertion that Kepler has found any Earth-like planets."[7][153][154]

In 2010, Kepler identified two systems containing objects which are smaller and hotter than their parent stars: KOI 74 and KOI 81.[155] These objects are probably low-mass white dwarfs produced by previous episodes of mass transfer in their systems.[145]

2011

[edit]

On February 2, 2011, the Kepler team announced the results of analysis of the data taken between 2 May and September 16, 2009.[149] They found 1235 planetary candidates circling 997 host stars. (The numbers that follow assume the candidates are really planets, though the official papers called them only candidates. Independent analysis indicated that at least 90% of them are real planets and not false positives).[158] 68 planets were approximately Earth-size, 288 super-Earth-size, 662 Neptune-size, 165 Jupiter-size, and 19 up to twice the size of Jupiter. In contrast to previous work, roughly 74% of the planets are smaller than Neptune, most likely as a result of previous work finding large planets more easily than smaller ones.

That February 2, 2011 release of 1235 exoplanet candidates included 54 that may be in the "habitable zone", including five less than twice the size of Earth.[159][160] There were previously only two planets thought to be in the "habitable zone", so these new findings represent an enormous expansion of the potential number of "Goldilocks planets" (planets of the right temperature to support liquid water).[161] All of the habitable zone candidates found thus far orbit stars significantly smaller and cooler than the Sun (habitable candidates around Sun-like stars will take several additional years to accumulate the three transits required for detection).[162] Of all the new planet candidates, 68 are 125% of Earth's size or smaller, or smaller than all previously discovered exoplanets.[160] "Earth-size" and "super-Earth-size" is defined as "less than or equal to 2 Earth radii (Re)" [(or, Rp ≤ 2.0 Re) – Table 5].[149] Six such planet candidates [namely: KOI 326.01 (Rp=0.85), KOI 701.03 (Rp=1.73), KOI 268.01 (Rp=1.75), KOI 1026.01 (Rp=1.77), KOI 854.01 (Rp=1.91), KOI 70.03 (Rp=1.96) – Table 6][149] are in the "habitable zone."[159] A more recent study found that one of these candidates (KOI 326.01) is in fact much larger and hotter than first reported.[163]

The frequency of planet observations was highest for exoplanets two to three times Earth-size, and then declined in inverse proportionality to the area of the planet. The best estimate (as of March 2011), after accounting for observational biases, was: 5.4% of stars host Earth-size candidates, 6.8% host super-Earth-size candidates, 19.3% host Neptune-size candidates, and 2.55% host Jupiter-size or larger candidates. Multi-planet systems are common; 17% of the host stars have multi-candidate systems, and 33.9% of all the planets are in multiple planet systems.[164]

By December 5, 2011, the Kepler team announced that they had discovered 2,326 planetary candidates, of which 207 are similar in size to Earth, 680 are super-Earth-size, 1,181 are Neptune-size, 203 are Jupiter-size and 55 are larger than Jupiter. Compared to the February 2011 figures, the number of Earth-size and super-Earth-size planets increased by 200% and 140% respectively. Moreover, 48 planet candidates were found in the habitable zones of surveyed stars, marking a decrease from the February figure; this was due to the more stringent criteria in use in the December data.[165]

On December 20, 2011, the Kepler team announced the discovery of the first Earth-size exoplanets, Kepler-20e[156] and Kepler-20f,[157] orbiting a Sun-like star, Kepler-20.[166]

Based on Kepler's findings, astronomer Seth Shostak estimated in 2011 that "within a thousand light-years of Earth", there are "at least 30,000" habitable planets.[167] Also based on the findings, the Kepler team has estimated that there are "at least 50 billion planets in the Milky Way", of which "at least 500 million" are in the habitable zone.[168] In March 2011, astronomers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) reported that about "1.4 to 2.7 percent" of all Sun-like stars are expected to have Earth-size planets "within the habitable zones of their stars". This means there are "two billion" of these "Earth analogs" in the Milky Way alone. The JPL astronomers also noted that there are "50 billion other galaxies", potentially yielding more than one sextillion "Earth analog" planets if all galaxies have similar numbers of planets to the Milky Way.[169]

2012

[edit]In January 2012, an international team of astronomers reported that each star in the Milky Way may host "on average...at least 1.6 planets", suggesting that over 160 billion star-bound planets may exist in the Milky Way.[170][171] Kepler also recorded distant stellar super-flares, some of which are 10,000 times more powerful than the 1859 Carrington event.[172] The superflares may be triggered by close-orbiting Jupiter-sized planets.[172] The Transit Timing Variation (TTV) technique, which was used to discover Kepler-9d, gained popularity for confirming exoplanet discoveries.[173] A planet in a system with four stars was also confirmed, the first time such a system had been discovered.[174]

As of 2012[update], there were a total of 2,321 candidates.[165][175][176] Of these, 207 are similar in size to Earth, 680 are super-Earth-size, 1,181 are Neptune-size, 203 are Jupiter-size and 55 are larger than Jupiter. Moreover, 48 planet candidates were found in the habitable zones of surveyed stars. The Kepler team estimated that 5.4% of all stars host Earth-size planet candidates, and that 17% of all stars have multiple planets.

2013

[edit]

According to a study by Caltech astronomers published in January 2013, the Milky Way contains at least as many planets as it does stars, resulting in 100–400 billion exoplanets.[177][178] The study, based on planets orbiting the star Kepler-32, suggests that planetary systems may be common around stars in the Milky Way. The discovery of 461 more candidates was announced on January 7, 2013.[107] The longer Kepler watches, the more planets with long periods it can detect.[107]

Since the last Kepler catalog was released in February 2012, the number of candidates discovered in the Kepler data has increased by 20 percent and now totals 2,740 potential planets orbiting 2,036 stars

A candidate, newly announced on January 7, 2013, was Kepler-69c (formerly, KOI-172.02), an Earth-size exoplanet orbiting a star similar to the Sun in the habitable zone and possibly habitable.[179]

In April 2013, a white dwarf was discovered bending the light of its companion red dwarf in the KOI-256 star system.[180]

In April 2013, NASA announced the discovery of three new Earth-size exoplanets—Kepler-62e, Kepler-62f, and Kepler-69c—in the habitable zones of their respective host stars, Kepler-62 and Kepler-69. The new exoplanets are considered prime candidates for possessing liquid water and thus a habitable environment.[181][182][183] A more recent analysis has shown that Kepler-69c is likely more analogous to Venus, and thus unlikely to be habitable.[184]

On May 15, 2013, NASA announced the space telescope had been crippled by failure of a reaction wheel that keeps it pointed in the right direction. A second wheel had previously failed, and the telescope required three wheels (out of four total) to be operational for the instrument to function properly. Further testing in July and August determined that while Kepler was capable of using its damaged reaction wheels to prevent itself from entering safe mode and of downlinking previously collected science data it was not capable of collecting further science data as previously configured.[185] Scientists working on the Kepler project said there was a backlog of data still to be looked at, and that more discoveries would be made in the following couple of years, despite the setback.[186]

Although no new science data from Kepler field had been collected since the problem, an additional sixty-three candidates were announced in July 2013 based on the previously collected observations.[187]

In November 2013, the second Kepler science conference was held. The discoveries included the median size of planet candidates getting smaller compared to early 2013, preliminary results of the discovery of a few circumbinary planets and planets in the habitable zone.[188]

2014

[edit]

On February 13, over 530 additional planet candidates were announced residing around single planet systems. Several of them were nearly Earth-sized and located in the habitable zone. This number was further increased by about 400 in June 2014.[189]

On February 26, scientists announced that data from Kepler had confirmed the existence of 715 new exoplanets. A new statistical method of confirmation was used called "verification by multiplicity" which is based on how many planets around multiple stars were found to be real planets. This allowed much quicker confirmation of numerous candidates which are part of multiplanetary systems. 95% of the discovered exoplanets were smaller than Neptune and four, including Kepler-296f, were less than 2 1/2 the size of Earth and were in habitable zones where surface temperatures are suitable for liquid water.[101][190][191][192]

In March, a study found that small planets with orbital periods of less than one day are usually accompanied by at least one additional planet with orbital period of 1–50 days. This study also noted that ultra-short period planets are almost always smaller than 2 Earth radii unless it is a misaligned hot Jupiter.[193]

On April 17, the Kepler team announced the discovery of Kepler-186f, the first nearly Earth-sized planet located in the habitable zone. This planet orbits around a red dwarf.[194]

In May 2014, K2 observations fields 0 to 13 were announced and described in detail.[118] K2 observations began in June 2014.

In July 2014, the first discoveries from K2 field data were reported in the form of eclipsing binaries. Discoveries were derived from a Kepler engineering data set which was collected prior to campaign 0[195] in preparation to the main K2 mission.[196]

On September 23, 2014, NASA reported that the K2 mission had completed campaign 1,[197] the first official set of science observations, and that campaign 2[198] was underway.[199]

Campaign 3[201] lasted from November 14, 2014, to February 6, 2015, and included "16,375 standard long cadence and 55 standard short cadence targets".[118]

2015

[edit]- In January 2015, the number of confirmed Kepler planets exceeded 1000. At least two (Kepler-438b and Kepler-442b) of the discovered planets announced that month were likely rocky and in the habitable zone.[40] Also in January 2015, NASA reported that five confirmed sub-earth-sized rocky exoplanets, all smaller than the planet Venus, were found orbiting the 11.2 billion year old star Kepler-444, making this star system, at 80% of the age of the universe, the oldest yet discovered.[202][203][204]

- In April 2015, campaign 4[205] was reported to last between February 7, 2015, and April 24, 2015, and to include observations of nearly 16,000 target stars and two notable open star clusters, Pleiades and Hyades.[206]

- In May 2015, Kepler observed a newly discovered supernova, KSN 2011b (Type Ia), before, during and after explosion. Details of the pre-nova moments may help scientists better understand dark energy.[200]

- On July 24, 2015, NASA announced the discovery of Kepler-452b, a confirmed exoplanet that is near-Earth in size and found orbiting the habitable zone of a Sun-like star.[207][208] The seventh Kepler planet candidate catalog was released, containing 4,696 candidates, and increase of 521 candidates since the previous catalog release in January 2015.[209][210]

- On September 14, 2015, astronomers reported unusual light fluctuations of KIC 8462852, an F-type main-sequence star in the constellation Cygnus, as detected by Kepler, while searching for exoplanets. Various hypotheses have been presented, including comets, asteroids, and an alien civilization.[211][212][213]

2016

[edit]By May 10, 2016, the Kepler mission had verified 1,284 new planets.[41] Based on their size, about 550 could be rocky planets. Nine of these orbit in their stars' habitable zone: Kepler-560b, Kepler-705b, Kepler-1229b, Kepler-1410b, Kepler-1455b, Kepler-1544 b, Kepler-1593b, Kepler-1606b, and Kepler-1638b.[41]

Data releases

[edit]The Kepler team originally promised to release data within one year of observations.[214] However, this plan was changed after launch, with data being scheduled for release up to three years after its collection.[215] This resulted in considerable criticism,[216][217][218][219][220] leading the Kepler science team to release the third quarter of their data one year and nine months after collection.[221] The data through September 2010 (quarters 4, 5, and 6) was made public in January 2012.[222]

Follow-ups by others

[edit]Periodically, the Kepler team releases a list of candidates (Kepler Objects of Interest, or KOIs) to the public. Using this information, a team of astronomers collected radial velocity data using the SOPHIE échelle spectrograph to confirm the existence of the candidate KOI-428b in 2010, later named Kepler-40b.[223] In 2011, the same team confirmed candidate KOI-423b, later named Kepler-39b.[224]

Citizen scientist participation

[edit]Since December 2010, Kepler mission data has been used for the Planet Hunters project, which allows volunteers to look for transit events in the light curves of Kepler images to identify planets that computer algorithms might miss.[225] By June 2011, users had found sixty-nine potential candidates that were previously unrecognized by the Kepler mission team.[226] The team has plans to publicly credit amateurs who spot such planets.

In January 2012, the BBC program Stargazing Live aired a public appeal for volunteers to analyse Planethunters.org data for potential new exoplanets. This led two amateur astronomers—one in Peterborough, England—to discover a new Neptune-sized exoplanet, to be named Threapleton Holmes B.[227] One hundred thousand other volunteers were also engaged in the search by late January, analyzing over one million Kepler images by early 2012.[228] One such exoplanet, PH1b (or Kepler-64b from its Kepler designation), was discovered in 2012. A second exoplanet, PH2b (Kepler-86b) was discovered in 2013.

In April 2017, ABC Stargazing Live, a variation of BBC Stargazing Live, launched the Zooniverse project "Exoplanet Explorers". While Planethunters.org worked with archived data, Exoplanet Explorers used recently downlinked data from the K2 mission. On the first day of the project, 184 transit candidates were identified that passed simple tests. On the second day, the research team identified a star system, later named K2-138, with a Sun-like star and four super-Earths in a tight orbit. In the end, volunteers helped to identify 90 exoplanet candidates.[229][230] The citizen scientists that helped discover the new star system will be added as co-authors in the research paper when published.[231]

Confirmed exoplanets

[edit]

Exoplanets discovered using Kepler's data, but confirmed by outside researchers, include Kepler-39b,[224] Kepler-40b,[223] Kepler-41b,[232] Kepler-43b,[233] Kepler-44b,[234] Kepler-45b,[235] as well as the planets orbiting Kepler-223[236] and Kepler-42.[237] The "KOI" acronym indicates that the star is a Kepler Object of Interest.

Kepler Input Catalog

[edit]The Kepler Input Catalog is a publicly searchable database of roughly 13.2 million targets used for the Kepler Spectral Classification Program and the Kepler mission.[238][239] The catalog alone is not used for finding Kepler targets, because only a portion of the listed stars (about one-third of the catalog) can be observed by the spacecraft.[238]

Solar System observations

[edit]Kepler has been assigned an observatory code (C55) in order to report its astrometric observations of small Solar System bodies to the Minor Planet Center. In 2013 the alternative NEOKepler mission was proposed, a search for near-Earth objects, in particular potentially hazardous asteroids (PHAs). Its unique orbit and larger field of view than existing survey telescopes allow it to look for objects inside Earth's orbit. It was predicted a 12-month survey could make a significant contribution to the hunt for PHAs as well as potentially locating targets for NASA's Asteroid Redirect Mission.[240] Kepler's first discovery in the Solar System, however, was (506121) 2016 BP81, a 200-kilometer cold classical Kuiper belt object located beyond the orbit of Neptune.[241]

Retirement

[edit]

On October 30, 2018, NASA announced that the Kepler space telescope, having run out of fuel, and after nine years of service and the discovery of over 2,600 exoplanets, has been officially retired, and will maintain its current, safe orbit, away from Earth.[9][10] The spacecraft was deactivated with a "goodnight" command sent from the mission's control center at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics on November 15, 2018.[242] Kepler's retirement coincides with the 388th anniversary of Johannes Kepler's death in 1630.[243]

See also

[edit]- Kepler-22b, the first exoplanet confirmed by Kepler to have an average orbital distance within its star's habitable zone

- List of exoplanets discovered using the Kepler spacecraft

- List of exoplanets

- List of multiplanetary systems

- List of stars that dim oddly

- Hunt for Exomoons with Kepler

- William J. Borucki, the chief investigator for Kepler

- NASA Exoplanet Archive, online exoplanet catalog

Other space-based exoplanet search projects

Other ground-based exoplanet search projects

Notes

[edit]- ^ Aperture of 0.95 m yields a light-gathering area of Pi×(0.95/2)2 = 0.708 m2; the 42 CCDs each sized 0.050 m × 0.025m yields a total sensor area of 0.0525 m2:[4]

- ^ This does not include Kepler candidates without a KOI designation, such as circumbinary planets, or candidates found in the Planet Hunters project.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Kepler: NASA's First Mission Capable of Finding Earth-Size Planets" (PDF). NASA. February 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 27, 2024. Retrieved March 13, 2015.

- ^ a b "KASC Scientific Webpage". Kepler Asteroseismic Science Consortium. Aarhus University. March 14, 2009. Archived from the original on May 5, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f "Kepler (spacecraft)". JPL Horizons On-Line Ephemeris System. NASA / JPL. January 6, 2018. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ^ "Kepler Spacecraft and Instrument". NASA. June 26, 2013. Archived from the original on January 19, 2014. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ a b "Kepler Launch". NASA. Archived from the original on March 17, 2010. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- ^ a b c "Kepler: About the Mission". NASA Ames Research Center. 2013. Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2016.

- ^ a b Dunham, Edward W.; Gautier, Thomas N.; Borucki, William J. (August 2, 2010). "Statement from the Kepler Science Council" (Press release). NASA Ames Research Center. Archived from the original on August 10, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2016.

- ^ DeVore, Edna (June 9, 2008). "Closing in on Extrasolar Earths". Space.com. Archived from the original on June 14, 2024. Retrieved March 14, 2009.

- ^ a b c Chou, Felicia; Hawkes, Alison; Cofield, Calia (October 30, 2018). "NASA Retires Kepler Space Telescope" (Press release). NASA / JPL. 2018-254. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- ^ a b c Overbye, Dennis (October 30, 2018). "Kepler, the Little NASA Spacecraft That Could, No Longer Can". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 30, 2018. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (May 12, 2013). "Finder of New Worlds". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 4, 2024. Retrieved May 13, 2014.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (January 6, 2015). "As Ranks of Goldilocks Planets Grow, Astronomers Consider What's Next". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 7, 2024. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ^ Borucki, William J.; Koch, David; Basri, Gibor; Batalha, Natalie; Brown, Timothy; Caldwell, Douglas; Caldwell, John; Christensen-Dalsgaard, Jørgen; Cochran, William D.; DeVore, Edna; Dunham, Edward W.; Dupree, Andrea K.; Gautier, Thomas N.; Geary, John C.; Gilliland, Ronald; Gould, Alan; Howell, Steve B.; Jenkins, Jon M.; Kondo, Yoji; et al. (February 2010). "Kepler Planet-Detection Mission: Introduction and First Results" (PDF). Science. 327 (5968): 977–980. Bibcode:2010Sci...327..977B. doi:10.1126/science.1185402. PMID 20056856. S2CID 22858074. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 2, 2022.

- ^ "Exoplanet and Candidate Statistics". exoplanetarchive.ipac.caltech.edu. NASA/Caltech. Archived from the original on October 7, 2024. Retrieved June 16, 2023.

- ^ a b Overbye, Dennis (October 30, 2018). "Kepler, the Little NASA Spacecraft That Could, No Longer Can". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 30, 2018. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- ^ "Ball Aerospace Kepler Satellite Marks Five Years of Planet Hunting" (Press release). Ball Aerospace & Technologies. March 6, 2014. Archived from the original on October 21, 2024. Retrieved July 25, 2024 – via SpaceNews.

- ^ a b c d Borucki, W. J. (May 22, 2010). "Brief History of the Kepler Mission". NASA. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ Taylor, Travis S.; Osborn, Stephanie (November 15, 2012). A New American Space Plan. Baen Publishing Enterprises. ISBN 978-1-61824-961-6.

- ^ a b "Nasa launches Earth hunter probe". BBC News. March 7, 2009. Archived from the original on December 7, 2023. Retrieved March 14, 2009.

- ^ a b c Wall, Mike (April 4, 2012). "NASA Extends Planet-Hunting Kepler Mission Through 2016". Space.com. Archived from the original on July 15, 2024. Retrieved May 2, 2012.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (October 16, 2012). "Kepler's exoplanet survey jeopardized by two issues". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on June 16, 2024. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- ^ a b "Kepler Mission Manager Update" (Press release). NASA. May 21, 2013. Archived from the original on July 11, 2023. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ a b Overbye, Dennis (May 15, 2013). "Equipment Failure May Cut Kepler Mission Short". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 16, 2013. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g "NASA Ends Attempts to Fully Recover Kepler Spacecraft, Potential New Missions Considered" (Press release). NASA. August 15, 2013. 13-254. Archived from the original on March 12, 2024. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ a b c Overbye, Dennis (August 15, 2013). "NASA's Kepler Mended, but May Never Fully Recover". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 16, 2013. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Wall, Mike (August 15, 2013). "Planet-Hunting Days of NASA's Kepler Spacecraft Likely Over". Space.com. Archived from the original on June 27, 2024. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ "Kepler: NASA retires prolific telescope from planet-hunting duties". BBC News. August 16, 2013. Archived from the original on December 26, 2022.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (November 18, 2013). "New Plan for a Disabled Kepler". The New York Times. Mountain View, California. Archived from the original on November 19, 2013. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Johnson, Michele (November 25, 2013). Johnson, Michele (ed.). "A Sunny Outlook for NASA Kepler's Second Light". NASA Official: Brian Dunbar; Image credits: NASA Ames; NASA Ames/W Stenzel. NASA. Archived from the original on April 18, 2014. Retrieved December 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Johnson, Michele (December 11, 2013). Johnson, Michele (ed.). "Kepler's Second Light: How K2 Will Work". NASA Official: Brian Dunbar; Image credit: NASA Ames/W Stenzel. NASA. Archived from the original on April 18, 2014. Retrieved December 12, 2013.

- ^ a b Hunter, Roger (December 11, 2013). Johnson, Michele (ed.). "Kepler Mission Manager Update: Invited to 2014 Senior Review". NASA Official: Brian Dunbar. NASA. Archived from the original on April 18, 2014. Retrieved December 12, 2013.

- ^ a b Sobeck, Charlie (May 16, 2014). Johnson, Michele (ed.). "Kepler Mission Manager Update: K2 Has Been Approved!". NASA Official: Brian Dunbar; Image credit(s): NASA Ames/W. Stenzel. NASA. Archived from the original on May 17, 2014. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ^ Wall, Mike (June 14, 2013). "Ailing NASA Telescope Spots 503 New Alien Planet Candidates". Space.com. TechMediaNetwork. Archived from the original on June 17, 2024. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ^ "NASA's Exoplanet Archive KOI table". NASA. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

- ^ Crossfield, Ian J. M.; Petigura, Erik; Schlieder, Joshua; Howard, Andrew W.; Fulton, B. J.; et al. (January 2015). "A nearby M star with three transiting super-Earths discovered by K2". The Astrophysical Journal. 804 (1): 10. arXiv:1501.03798. Bibcode:2015ApJ...804...10C. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/804/1/10. S2CID 14204860.

- ^ a b Overbye, Dennis (November 4, 2013). "Far-Off Planets Like the Earth Dot the Galaxy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 24, 2015. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ a b Petigura, Erik A.; Howard, Andrew W.; Marcy, Geoffrey W. (October 31, 2013). "Prevalence of Earth-size planets orbiting Sun-like stars". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States. 110 (48): 19273–19278. arXiv:1311.6806. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11019273P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1319909110. PMC 3845182. PMID 24191033.

- ^ "17 Billion Earth-Size Alien Planets Inhabit Milky Way". Space.com. January 7, 2013. Archived from the original on September 20, 2024. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ^ Khan, Amina (November 4, 2013). "Milky Way may host billions of Earth-size planets". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 25, 2024. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ a b c Clavin, Whitney; Chou, Felicia; Johnson, Michele (January 6, 2015). "NASA's Kepler Marks 1,000th Exoplanet Discovery, Uncovers More Small Worlds in Habitable Zones" (Press release). NASA / JPL. 2015-003. Archived from the original on September 27, 2024. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ^ a b c "NASA's Kepler Mission Announces Largest Collection of Planets Ever Discovered" (Press release). NASA. May 10, 2016. 16-051. Archived from the original on October 3, 2024. Retrieved May 10, 2016.

- ^ "Briefing materials: 1,284 Newly Validated Kepler Planets". NASA. May 10, 2016. Archived from the original on May 5, 2019. Retrieved May 10, 2016.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (May 10, 2016). "Kepler Finds 1,284 New Planets". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 10, 2016. Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- ^ Cowen, Ron (January 16, 2014). "Kepler clue to supernova puzzle". Nature. 505 (7483). Nature Publishing Group: 274–275. Bibcode:2014Natur.505..274C. doi:10.1038/505274a. ISSN 1476-4687. OCLC 01586310. PMID 24429610.

- ^ "NASA Retires Kepler Space Telescope, Passes Planet-Hunting Torch" (Press release). NASA. October 30, 2018. 18-092. Archived from the original on October 3, 2024.

- ^ Wiessinger, Scott; Lepsch, Aaron E.; Kazmierczak, Jeanette; Reddy, Francis; Boyd, Padi (September 17, 2018). "NASA's TESS Releases First Science Image". NASA. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- ^ Atkins, William (December 28, 2008). "Exoplanet Search Begins with French Launch of Corot Telescope Satellite". iTWire. Archived from the original on December 4, 2008. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- ^ a b Caldwell, Douglas A.; van Cleve, Jeffrey E.; Jenkins, Jon M.; Argabright, Vic S.; Kolodziejczak, Jeffery J.; et al. (July 2010). Oschmann, Jacobus M. Jr.; Clampin, Mark C.; MacEwen, Howard A. (eds.). Kepler instrument performance: An in-flight update (PDF). Space Telescopes and Instrumentation 2010: Optical, Infrared, and Millimeter Wave. Vol. 7731. San Diego, California, United States: SPIE. 773117. Bibcode:2010SPIE.7731E..17C. doi:10.1117/12.856638. S2CID 121398671. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 21, 2011.

- ^ Johnson, Michele, ed. (July 30, 2015). "Kepler: Spacecraft and Instrument". NASA. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ Barentsen, Geert, ed. (August 16, 2017). "Kepler and K2 data products". NASA. Archived from the original on January 7, 2016. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ "PyKE Primer – 2. Data Resources". NASA. Archived from the original on February 17, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- ^ "Kepler Primary Mirror". NASA. Archived from the original on June 18, 2020. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ^ "Corning To Build Primary Mirror For Kepler Photometer". Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ^ Fulton L., Michael; Dummer, Richard S. (2011). "Advanced Large Area Deposition Technology for Astronomical and Space Applications". Vacuum & Coating Technology (December 2011): 43–47. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- ^ "Ball Aerospace Completes Primary Mirror and Detector Array Assembly Milestones for Kepler Mission". SpaceRef.com (Press release). Ball Aerospace and Technologies. September 25, 2007. Archived from the original on June 16, 2013. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- ^ Gilliland, Ronald L.; et al. (2011). "Kepler Mission Stellar and Instrument Noise Properties". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 197 (1): 6. arXiv:1107.5207. Bibcode:2011ApJS..197....6G. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/197/1/6. S2CID 118626534.

- ^ Beatty, Kelly (September 2011). "Kepler's Dilemma: Not Enough Time". Sky and Telescope. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ^ "NASA Approves Kepler Mission Extension". NASA. April 4, 2012. Archived from the original on July 7, 2012.

- ^ a b "Kepler Mission Rockets to Space in Search of Other Earth" (Press release). NASA. March 6, 2009. Archived from the original on March 15, 2009. Retrieved March 14, 2009.

- ^ Koch, David; Gould, Alan (March 2009). "Kepler Mission: Launch Vehicle and Orbit". NASA. Archived from the original on June 22, 2007. Retrieved March 14, 2009.

- ^ "Kepler: Spacecraft and Instrument". NASA. Archived from the original on October 6, 2020. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ "NASA Astrobiology".

- ^ "Performance Analysis of Operational Ka-band Link with Kepler" (PDF).

- ^ Ng, Jansen (March 8, 2009). "Kepler Mission Sets Out to Find Planets Using CCD Cameras". DailyTech. Archived from the original on March 10, 2009. Retrieved March 14, 2009.

- ^ Jenkins, Jon M. (January 25, 2017). "Kepler Data Processing Handbook (KSCI-19081-002)" (PDF). NASA.

- ^ Hunter, Roger (July 24, 2012). "Kepler Mission Manager Update". NASA. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2012.

- ^ McKee, Maggie (July 24, 2012). "Kepler glitch may lower odds of finding Earth's twin". New Scientist. Archived from the original on July 2, 2024.

- ^ "A Newly Discovered Branch of the Fault Tree Explaining Systematic Reaction Wheel Failures and Anomalies" (PDF).

- ^ DeVore, Edna (April 9, 2009). "Planet-Hunting Kepler Telescope Lifts Its Lid". Space.com. Archived from the original on June 29, 2024. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ "NASA's Kepler Captures First Views of Planet-Hunting Territory". NASA. April 16, 2009. Archived from the original on April 18, 2009. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ "04.20.09 – Kepler Mission Manager Update". NASA. April 20, 2009. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- ^ "04.23.09 – Kepler Mission Manager Update". NASA. April 23, 2009. Archived from the original on July 22, 2016. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- ^ "05.14.09 – Kepler Mission Manager Update". NASA. May 14, 2009. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

- ^ "Let the Planet Hunt Begin". NASA. May 13, 2009. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2009.

- ^ "2009 July 7 Mission Manager Update". NASA. July 7, 2009. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Kepler Mission Manager Update". NASA. October 14, 2009. Archived from the original on May 10, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

- ^ "Kepler outlook positive; Followup Observing Program in full swing". August 23, 2010. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Kepler Mission Manager Update". NASA. September 23, 2009. Archived from the original on April 17, 2020. Retrieved September 25, 2009.

- ^ a b "Kepler Mission Manager Update". NASA. November 5, 2009. Archived from the original on July 23, 2020. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ^ mission website calculator

- ^ "Kepler mission & program information". Ball Aerospace & Technologies. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ^ Koch, David; Gould, Alan (2004). "Overview of the Kepler Mission" (PDF). SPIE. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ Muir, Hazel (April 25, 2007). "'Goldilocks' planet may be just right for life". New Scientist. Archived from the original on July 4, 2024. Retrieved April 2, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e David Koch and Alan Gould, curators (March 2009). "Kepler Mission: Characteristics of Transits (section 'Geometric Probability')". NASA. Archived from the original on August 25, 2009. Retrieved September 21, 2009.

- ^ Batalha, N. M.; Borucki, W. J.; Koch, D. G.; Bryson, S. T.; Haas, M. R.; et al. (January 3, 2010). "Selection, Prioritization, and Characteristics of Kepler Target Stars". The Astrophysical Journal. 713 (2): L109 – L114. arXiv:1001.0349. Bibcode:2010ApJ...713L.109B. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/713/2/L109. S2CID 39251116.

- ^ "Kepler Mission: Frequently Asked Questions". NASA. March 2009. Archived from the original on August 20, 2007. Retrieved March 14, 2009.

- ^ Grigahcène, A.; et al. (2010). "Hybrid γ Doradus – δ Scuti pulsators: New insights into the physics of the oscillations from Kepler observations". The Astrophysical Journal. 713 (2): L192 – L197. arXiv:1001.0747. Bibcode:2010ApJ...713L.192G. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/713/2/L192. S2CID 56144432.

- ^ Chaplin, W. J.; et al. (2010). "The asteroseismic potential of Kepler: first results for solar-type stars". The Astrophysical Journal. 713 (2): L169 – L175. arXiv:1001.0506. Bibcode:2010ApJ...713L.169C. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/713/2/L169. S2CID 67758571.