Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Karnataka

View on Wikipedia

Karnataka[a] is a state in the southwestern region of India. It was formed as Mysore State on 1 November 1956, with the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, and renamed Karnataka in 1973. The state is bordered by the Lakshadweep Sea to the west, Goa to the northwest, Maharashtra to the north, Telangana to the northeast, Andhra Pradesh to the east, Tamil Nadu to the southeast, and Kerala to the southwest. With 61,130,704 inhabitants at the 2011 census, Karnataka is the eighth-largest state by population, comprising 31 districts. With 15,257,000 residents, the state capital Bengaluru is the largest city of Karnataka.[14]

Key Information

The economy of Karnataka is among the most productive in the country with a gross state domestic product (GSDP) of ₹25.01 trillion (US$300 billion) and a per capita GSDP of ₹332,926 (US$3,900) for the financial year 2023–24.[15][16] The state experienced a GSDP growth of 10.2% for the same fiscal year.[15] After Bengaluru Urban, Dakshina Kannada, Hubli–Dharwad, and Belagavi districts contribute the highest revenue to the state respectively. The capital of the state, Bengaluru, is known as the Silicon Valley of India, for its immense contributions to the country's information technology sector. A total of 1,973 companies in the state were found to have been involved in the IT sector as of 2007.[17]

Karnataka is the only southern state to have land borders with all of the other four southern Indian sister states. The state covers an area of 191,791 km2 (74,051 sq mi), or 5.83 per cent of the total geographical area of India.[18] It is the sixth-largest Indian state by area.[18] Kannada, one of the classical languages of India, is the most widely spoken and official language of the state. Other minority languages spoken include Urdu, Konkani, Marathi, Tulu, Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, Kodava and Beary. Karnataka also contains some of the only villages in India where Sanskrit is primarily spoken.[19][20][21]

Though several etymologies have been suggested for the name Karnataka, the generally accepted one is that Karnataka is derived from the Kannada words karu and nādu, meaning "elevated land". Karu Nadu may also be read as karu, meaning "black" and nadu, meaning "region", as a reference to the black cotton soil found in the Bayalu Seeme region of the state. The British used the word Carnatic, sometimes Karnatak, to describe both sides of peninsular India, south of the Krishna.[22] With an antiquity that dates to the Paleolithic, Karnataka has been home to some of the most powerful empires of ancient and medieval India. The philosophers and musical bards patronised by these empires launched socio-religious and literary movements which have endured to the present day. Karnataka has contributed significantly to both forms of Indian classical music, the Carnatic and Hindustani traditions.

Etymology

[edit]History

[edit]

Karnataka's pre-history goes back to a Paleolithic hand-axe culture evidenced by discoveries of, among other things, hand axes and cleavers in the region.[23] Evidence of Neolithic and megalithic cultures have also been found in the state. Gold discovered in Harappa was found to be imported from mines in Karnataka, prompting scholars to hypothesise about contacts between ancient Karnataka and the Indus Valley Civilisation c. 3300 BCE.[24][25]

Prior to the third century BCE, most of Karnataka formed part of the Mauryan Empire of Emperor Ashoka. Four centuries of Satavahana rule followed, allowing them to control large areas of Karnataka. The decline of Satavahana power led to the rise of the earliest native kingdoms, the Kadambas and the Western Gangas, marking the region's emergence as an independent political entity. The Kadamba Dynasty, founded by Mayurasharma, had its capital at Banavasi;[26][27] the Western Ganga Dynasty was formed with Talakad as its capital.[28][29]

These were also the first kingdoms to use Kannada in administration, as evidenced by the Halmidi inscription and a fifth-century copper coin discovered at Banavasi.[30][31] These dynasties were followed by imperial Kannada empires such as the Badami Chalukyas,[32][33] the Rashtrakuta Empire[34][35] and the Western Chalukya Empire,[36][37] which ruled over large parts of the Deccan and had their capitals in what is now Karnataka. The Western Chalukyas patronised a unique style of architecture and Kannada literature which became a precursor to the Hoysala art of the 12th century.[38][39] Parts of modern-day Southern Karnataka (Gangavadi) were occupied by the Chola Empire at the turn of the 11th century.[40] The Cholas and the Hoysalas fought over the region in the early 12th century before it eventually came under Hoysala rule.[40]

At the turn of the first millennium, the Hoysalas gained power in the region. Literature flourished during this time, which led to the emergence of distinctive Kannada literary metres, and the construction of temples and sculptures adhering to the Vesara style of architecture.[41][42][43][44] The expansion of the Hoysala Empire brought minor parts of modern Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu under its rule. In the early 14th century, Harihara and Bukka Raya established the Vijayanagara empire with its capital, Hosapattana (later named Vijayanagara), on the banks of the Tungabhadra River in the modern Bellary district. Under the rule of Krishnadevaraya, a distinct form of literature and architecture evolved.[45][46] The empire rose as a bulwark against Muslim advances into South India, which it completely controlled for over two centuries.[47][48] In 1537, Kempe Gowda I, a chieftain of the Vijayanagara Empire, widely held as the founder of modern Bengaluru, built a fort and established the area around it as Bengaluru Pete.[49]

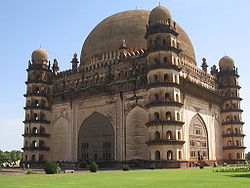

In 1565, Karnataka and the rest of South India experienced a major geopolitical shift when the Vijayanagara empire fell to a confederation of Islamic sultanates in the Battle of Talikota.[50] The Bijapur Sultanate, which had risen after the demise of the Bahmani Sultanate of Bidar, soon took control of much of the Deccan; it was defeated by the Mughals in the late 17th century.[51][52] The Bahmani and Bijapur rulers encouraged Urdu and Persian literature and Indo-Saracenic architecture, the Gol Gumbaz being one of the high points of this style.[53] During the sixteenth century, Konkani Hindus migrated to Karnataka, mostly from Salcette, Goa,[54] while during the seventeenth and eighteenth century, Goan Catholics migrated to North Canara and South Canara, especially from Bardes, Goa, as a result of food shortages, epidemics and heavy taxation imposed by the Portuguese.[55]

In the period that followed, parts of northern Karnataka were ruled by the Nizam of Hyderabad, the Maratha Empire, the British, and other powers.[56] In the south, the Mysore Kingdom, a former vassal of the Vijayanagara Empire, was briefly independent.[57] With the death of Krishnaraja Wodeyar II, Haidar Ali, the commander-in-chief of the Mysore army, gained control of the region. After his death, the kingdom was inherited by his son Tipu Sultan.[58] To contain European expansion in South India, Hyder Ali and later Tipu Sultan fought four significant Anglo-Mysore Wars, the last of which resulted in Tippu Sultan's death and the incorporation of Mysore into British India in 1799.[59] Mysore was restored to the Wodeyars, and the Kingdom of Mysore became a princely state outside but in a subsidiary alliance with British India.[58]

As the "doctrine of lapse" gave way to dissent and resistance from princely states across the country, Kittur Chennamma, Queen of Kittur, her military leader Sangolli Rayanna, and others, spearheaded rebellions in part of what is now Karnataka in 1830, nearly three decades before the Indian Rebellion of 1857. However, Kitturu was taken over by the British East India Company even before the doctrine was officially articulated by Lord Dalhousie in 1848.[60] Other uprisings followed, such as the ones at Supa, Bagalkot, Shorapur, Nargund and Dandeli. These rebellions—which coincided with the Indian Rebellion of 1857—were led by Mundargi Bhimarao, Bhaskar Rao Bhave, the Halagali Bedas, Raja Venkatappa Nayaka and others. By the late 19th century, the independence movement had gained momentum; Karnad Sadashiva Rao, Aluru Venkata Raya, S. Nijalingappa, Kengal Hanumanthaiah, Nittoor Srinivasa Rau and others carried on the struggle into the early 20th century.[61]

After the independence of British India, the Maharaja, Jayachamarajendra Wodeyar, signed an instrument of accession to accede his state to the new India. In 1950, Mysore became an Indian state of the same name; the former Maharaja served as its Rajpramukh (head of state) until 1975. Following the long-standing demand of the Ekikarana Movement, Kodagu- and Kannada-speaking regions from the adjoining states of Madras, Hyderabad and Bombay were incorporated into the Mysore state, under the States Reorganisation Act of 1956. The thus expanded state was renamed Karnataka, seventeen years later, on 1 November 1973.[62] In the early 1900s through the post-independence era, industrial visionaries such as Sir Mokshagundam Visvesvarayya, played an important role in the development of Karnataka's strong manufacturing and industrial base.[63][64]

Geography

[edit]The state has three principal geographical zones:

- The coastal region of Karavali and Tulu Nadu

- The hilly Malenadu region comprising the Western Ghats

- The Bayaluseeme region comprising the plains of the Deccan Plateau

The bulk of the state is in the Bayaluseeme region, the northern part of which is the second-largest arid region in India.[65] The highest point in Karnataka is the Mullayanagiri hills in Chikmagalur district which has an altitude of 1,925 m (6,316 ft). The two main river systems of the state are the Krishna and its tributaries, the Bhima, Ghataprabha, Vedavathi, Malaprabha and Tungabhadra in North Karnataka, and the Kaveri and its tributaries, the Hemavati, Shimsha, Arkavati, Lakshmana Thirtha and Kabini, in South Karnataka. Most of these rivers flow out of Karnataka eastward, reaching the sea at the Bay of Bengal. Other prominent rivers such as the Sharavati in Shimoga and Netravati in Dakshina Kannada flow westward to the Lakshadweep Sea. A large number of dams and reservoirs are constructed across these rivers which richly add to the irrigation and hydroelectricity power generation capacities of the state.[66][67]

Karnataka consists of four main types of geological formations[68] – the Archean complex made up of Dharwad schists and granitic gneisses,[69] the Proterozoic non-fossiliferous sedimentary formations of the Kaladgi and Bhima series,[70] the Deccan trappean and intertrappean deposits and the tertiary and recent laterites and alluvial deposits.[71] Laterite cappings that are found in many districts over the Deccan Traps were formed after the cessation of volcanic activity in the early tertiary period. Eleven groups of soil orders are found in Karnataka, viz. Entisols, Inceptisols, Mollisols, Spodosols, Alfisols, Ultisols, Oxisols, Aridisols, Vertisols, Andisols and Histosols.[68][72] Depending on the agricultural capability of the soil, the soil types are divided into six types, viz. red, lateritic, black, alluvio-colluvial, forest and coastal soils.[72]

About 38,284 km2 (14,782 sq mi) of Karnataka (i.e. 16% of the state's geographic area) is covered by forests.[73][74] The forests are classified as reserved, protected, unclosed, village and private forests.[73] The percentage of forested area is slightly less than the all-India average of about 23%,[73] and significantly less than the 33% prescribed in the National Forest Policy.[75]

Climate

[edit]Karnataka experiences four seasons. The winter in January and February is followed by summer between March and May, the monsoon season between June and September and the post-monsoon season from October till December. Meteorologically, Karnataka is divided into three zones – coastal, north interior and south interior. Of these, the coastal zone receives the heaviest rainfall with an average rainfall of about 3,638.5 mm (143 in) per annum, far in excess of the state average of 1,139 mm (45 in). Amagaon in Khanapura taluka of Belgaum district received 10,068 mm (396 in) of rainfall in 2010.[76] In 2014 Kokalli in Sirsi taluka of Uttara Kannada district received 8,746 mm (344 in) of rainfall.[77] Agumbe in Thirthahalli taluka and Hulikal of Hosanagara taluka in Shimoga district were the rainiest cities in Karnataka, situated in one of the wettest regions in the world.[78]

The state is projected to warm about 2.0 °C (4 °F) by 2030. The monsoon is set to provide less rainfall. Agriculture in Karnataka is mostly rainfed as opposed to irrigated, making it highly vulnerable to expected changes in the monsoon.[79] The highest recorded temperature was 45.6 °C (114 °F) in Raichuru district. The lowest recorded temperature was 2.8 °C (37 °F) at Bidar district.[80]

Flora and fauna

[edit]

Karnataka is home to a variety of wildlife. It has a recorded forest area of 38,720 km2 (14,950 sq mi) which constitutes 12.3% of the total geographical area of the state.[81] These forests support 25% of the Indian elephant and 10% of the tiger population of India. Many regions of Karnataka are as yet unexplored, so new species of flora and fauna are found periodically. The Western Ghats, a biodiversity hotspot, includes the western region of Karnataka. Bandipur and Nagarhole National Parks were included in the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve in 1986, a UNESCO designation.[82] The Indian roller and the Indian elephant are recognised as the state bird and animal while sandalwood and the lotus are recognised as the state tree and flower respectively. Karnataka has five national parks: Anshi, Bandipur, Bannerghatta, Kudremukh and Nagarhole.[83] It also has 27 wildlife sanctuaries of which seven are bird sanctuaries.[84][81]

Wild animals in Karnataka include the Indian elephant, tiger, leopard, gaur, sambar deer, chital, Indian muntjac, bonnet macaque, slender loris, Asian palm civet, small Indian civet, sloth bear, dhole, striped hyena, Bengal fox and golden jackal. Some of the birds present include the great hornbill, Malabar pied hornbill, Ceylon frogmouth, herons, ducks, kites, eagles, falcons, quails, partridges, lapwings, sandpipers, pigeons, doves, parakeets, cuckoos, owls, nightjars, swifts, kingfishers, bee-eaters and munias.[83][85][86] Some species of trees are Calophyllum tomentosum, Calophyllum apetalum, Garcinia cambogia, Garcinia morella, Alstonia scholaris, Flacourtia montana, Artocarpus hirsutus, Artocarpus lacucha, Cinnamomum zeylanicum, Grewia tiliifolia, Santalum album, Shorea talura, Emblica officinalis, Vitex altissima and Wrightia tinctoria. Wildlife in Karnataka is threatened by poaching, habitat destruction, human-wildlife conflict and pollution.[83]

Sub-divisions

[edit]

There are 31 districts in Karnataka. Each district (zila) is administered by a Deputy Commissioner (also known as the District Collector), who is typically an officer of the Indian Administrative Service (IAS). The districts are further divided into revenue sub-divisions, which are administered by assistant commissioners. These sub-divisions are further divided into taluks (or talukas), which are administered by Tahsildars. Taluks comprise hoblis (clusters of adjoining villages), which include revenue villages.

Karnataka has around 6,022 Gram Panchayats, 226 Taluk Panchayats, and 31 Zilla Panchayats in rural areas. In urban areas, there are 318 urban local bodies, including 1 BBMP, 13 Municipal Corporations, 60 City Municipal Councils, 126 Town Municipal Councils, 114 Town Panchayats and 4 notified area committees.[87][88][89][90]

| Sl. no. | Divisions | Capital | Sl. no. | Districts | Capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kitturu Karnataka | Belgaum | 1 | Bagalkot | Bagalkot |

| 2 | Belgaum | Belgaum | |||

| 3 | Dharwad | Dharwad | |||

| 4 | Gadag | Gadag-Betageri | |||

| 5 | Haveri | Haveri | |||

| 6 | Uttara Kannada | Karwar | |||

| 7 | Bijapur | Bijapur | |||

| 2 | Bengaluru | Bengaluru | 8 | Bengaluru Urban | Bengaluru |

| 9 | Bengaluru Rural | Doddaballapura | |||

| 10 | Bengaluru South | Ramanagara | |||

| 11 | Chikkaballapura | Chikkaballapur | |||

| 12 | Chitradurga | Chitradurga | |||

| 13 | Davanagere | Davanagere | |||

| 14 | Kolar | Kolar | |||

| 15 | Shimoga | Shimoga | |||

| 16 | Tumakuru | Tumkur | |||

| 3 | Kalyana Karnataka | Kalabuargi | 17 | Ballari | Ballari |

| 18 | Bidar | Bidar | |||

| 19 | Kalabuargi | Kalabuargi | |||

| 20 | Koppal | Koppal | |||

| 21 | Raichur | Raichur | |||

| 22 | Yadagiri | Yadagiri | |||

| 23 | Vijayanagara | Hospet | |||

| 4 | Mysore | Mysore | 24 | Chamarajanagara | Chamarajanagar |

| 25 | Chikmagalur | Chikmagalur | |||

| 26 | Dakshina Kannada | Mangaluru | |||

| 27 | Hassan | Hassan | |||

| 28 | Kodagu | Madikeri | |||

| 29 | Mandya | Mandya | |||

| 30 | Mysore | Mysore | |||

| 31 | Udupi | Udupi |

Demographics

[edit]| Rank | City | District | Population (2011) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bengaluru | Bengaluru Urban | 10,456,000 |

| 2 | Hubli–Dharwad | Dharwad | 943,857 |

| 3 | Mysore | Mysore | 920,550 |

| 4 | Belgaum | Belagavi | 610,350 |

| 5 | Kalaburagi | Kalaburagi | 543,147 |

| 6 | Mangaluru | Dakshina Kannada | 484,785 |

| 7 | Davanagere | Davanagere | 435,128 |

| 8 | Ballari | Ballari | 409,444 |

| 9 | Bijapur | Bijapur | 330,143 |

| 10 | Shimoga | Shimoga | 322,650 |

| 11 | Tumkur | Tumakuru | 305,821 |

According to the 2011 census of India,[91] the total population of Karnataka was 61,095,297 of which 30,966,657 (50.7%) were male and 30,128,640 (49.3%) were female, or 1000 males for every 973 females. This represents a 15.60% increase over the population in 2001. The population density was 319 per km2 and 38.67% of the people lived in urban areas. The literacy rate was 75.36% with 82.47% of males and 68.08% of females being literate.[91]

In 2007 the state had a birth rate of 2.2%, a death rate of 0.7%, an infant mortality rate of 5.5% and a maternal mortality rate of 0.2%. The total fertility rate was 2.2.[92]

Karnataka's private sector speciality health care competes with the best in the world.[93][94] Karnataka has also established a modicum of public health services having a better record of health care and child care than most other states of India. In spite of these advances, some parts of the state still suffer from the lack of primary health care.[95]

Karnataka ranked tenth in the Fiscal Health Index (FHI) 2025, with a score of 40.8.[96]

Religion

[edit]

Adi Shankara (788–820 CE) chose Sringeri in Karnataka to establish the first of his four mathas (monastery). Madhvacharya (1238–1317) was the chief proponent of Tattvavada (philosophy of reality), popularly known as Dvaita or Dualistic school of Hindu philosophy – one of the three most influential Vedanta philosophies. Madhvacharya was one of the important philosophers during the Bhakti movement. He was a pioneer in many ways, going against standard conventions and norms. According to tradition, Madhvacharya is believed to be the third incarnation of Vayu (Mukhyaprana), after Hanuman and Bhima. The Haridasa devotional movement is considered one of the turning points in the cultural history of India. Over a span of nearly six centuries, several saints and mystics helped shape the culture, philosophy, and art of South India and Karnataka in particular by exerting considerable spiritual influence over the masses and kingdoms that ruled South India.[citation needed]

This movement was ushered in by the Haridasas (literally "servants of Hari") and took shape in the 13th century – 14th century CE, period, prior to and during the early rule of the Vijayanagara empire. The main objective of this movement was to propagate the Dvaita philosophy of Madhvacharya (Madhva Siddhanta) to the masses through a literary medium known as Dasa Sahitya. Purandara dasa is widely recognised as the "Pithamaha" of Carnatic Music for his immense contribution. Ramanuja, the leading expounder of Vishishtadvaita, spent many years in Melkote. He came to Karnataka in 1098 CE and lived here until 1122 CE. He first lived in Tondanur and then moved to Melkote where the Cheluvanarayana Swamy Temple and a well-organised matha were built. He was patronised by the Hoysala king, Vishnuvardhana.[98]

In the twelfth century, Lingayatism emerged in northern Karnataka as a protest against the rigidity of the prevailing social and caste system. Leading figures of this movement were Basava, Akka Mahadevi and Allama Prabhu, who established the Anubhava Mantapa which was the centre of all religious and philosophical thoughts and discussions pertaining to Lingayats. These three social reformers did so by the literary means of "Vachana Sahitya" which is very famous for its simple, straight forward and easily understandable Kannada language. Lingayatism preached women equality by letting women wear Ishtalinga i.e. Symbol of god around their neck. Basava shunned the sharp hierarchical divisions that existed and sought to remove all distinctions between the hierarchically superior master class and the subordinate, servile class. He also supported inter-caste marriages and Kaay Ta tTatva of Basavanna. This was the basis of the Lingayat faith which today counts millions among its followers.[99]

The Jain philosophy and literature have contributed immensely to the religious and cultural landscape of Karnataka.[citation needed]

Islam, which had an early presence on the west coast of India as early as the tenth century, gained a foothold in Karnataka with the rise of the Bahamani and Bijapur sultanates that ruled parts of Karnataka.[100] Christianity reached Karnataka in the sixteenth century with the arrival of the Portuguese and St. Francis Xavier in 1545.[101]

Buddhism was popular in Karnataka during the first millennium in places such as Gulbarga and Banavasi. A chance discovery of edicts and several Mauryan relics at Sannati in Kalaburagi district in 1986 has proven that the Krishna River basin was once home to both Mahayana and Hinayana Buddhism. There are Tibetan refugee camps in Karnataka.[citation needed]

Festivals

[edit]Mysore Dasara is celebrated as the Nada habba (state festival) and this is marked by major festivities at Mysore. Bengaluru Karaga, celebrated in the heart of Bengaluru, is the second most important festival celebrated in Karnataka.[102] Ugadi (Kannada New Year), Makara Sankranti (the harvest festival), Ganesh Chaturthi, Gowri Habba, Ram Navami, Nagapanchami, Basava Jayanthi, Deepavali, and Balipadyami are the other major festivals of Karnataka.[citation needed]

Language

[edit]

Kannada is the official language of the state of Karnataka, as the native language of 66.46% of its population as of 2011 and is one of the classical languages of India. Urdu is the second largest language, spoken by 10.83% of the population, and is the language of Muslims outside the coastal region. Telugu (5.84%) is a major language in areas bordering Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka as well as Bengaluru, while Tamil (3.45%) is a major language of Bengaluru and in the Kolar district. Marathi (3.29%) is concentrated in areas of Uttara Kannada, Belgaum and Bidar districts bordering Maharashtra. Lambadi is spoken by the Lambadis scattered throughout North Karnataka, while Hindi is spoken in Bengaluru. Tulu (2.61%), Konkani (1.29%), and Malayalam (1.27%) are all found in linguistically diverse Coastal Karnataka, where a number of mixed and distinct dialects such as Are Bhashe, Beary Bhashe, and Nawayathi are found. Kodava Takk is the language of Kodagu.[103][104][105]

Kannada played a crucial role in the creation of Karnataka: linguistic demographics played a major role in defining the new state in 1956. Tulu, Konkani and Kodava are other minor native languages that share a long history in the state. Urdu is spoken widely by the Muslim population. Less widely spoken languages include Beary bashe and certain languages such as Sankethi. Some of the regional languages in Karnataka are Tulu, Kodava, Konkani and Beary.[106][107][108]

Kannada features a rich and ancient body of literature including religious and secular genre, covering topics as diverse as Jainism (such as Puranas), Lingayatism (such as Vachanas), Vaishnavism (such as Haridasa Sahitya) and modern literature. Evidence from edicts during the time of Ashoka (reigned 274–232 BCE) suggest that Buddhist literature influenced the Kannada script and its literature. The Halmidi inscription, the earliest attested full-length inscription in the Kannada language and script, dates from 450 CE, while the earliest available literary work, the Kavirajamarga, has been dated to 850 CE. References made in the Kavirajamarga, however, prove that Kannada literature flourished in the native composition metres such as Chattana, Beddande and Melvadu during earlier centuries. The classic refers to several earlier greats (purvacharyar) of Kannada poetry and prose.[109] Kuvempu, the renowned Kannada poet and writer who wrote Jaya Bharata Jananiya Tanujate, the state anthem of Karnataka[1] was the first recipient of the Karnataka Ratna, the highest civilian award bestowed by the Government of Karnataka. Contemporary Kannada literature has received considerable acknowledgement in the arena of Indian literature, with eight Kannada writers winning India's highest literary honour, the Jnanpith award.[110][111]

Tulu is the majority language in the coastal district of Dakshina Kannada and is the second most spoken in the Udupi district.[112] This region is also known as Tulu Nadu.[113] Tulu Mahabharato, written by Arunabja in the Tigalari script, is the oldest surviving Tulu text.[114] Tigalari script was used by Brahmins to write Sanskrit language. The use of the Kannada script for writing Tulu and non-availability of print in Tigalari script contributed to the marginalisation of Tigalari script.[citation needed] In Karnataka Konkani is mostly spoken in the Uttara Kannada and Dakshina Kannada districts and in parts of Udupi, Konkani use the Devanagari Script (which is official)/Kannada script (Optional) for writing as identified by government of Karnataka.[115][116]

The Kodavas who mainly reside in the Kodagu district, speak Kodava Takk. Kodagu was a separate State with its own Chief Minister and Council of Ministers till 1956. Two regional variations of the language exist, the northern Mendale Takka and the southern Kiggaati Takka.[117] Kodava Takk has its own script, Karnataka Kodava Sahitya Academy has accepted I. M. Muthanna's script which was developed in 1970 as the official script of Kodava Thakk. English is the medium of education in many schools and widely used for business communication in most private companies.[citation needed] All of the state's languages are patronised and promoted by governmental and quasi-governmental bodies. The Kannada Sahitya Parishat and the Kannada Sahitya Akademi are responsible for the promotion of Kannada while the Karnataka Konkani Sahitya Akademi,[118] the Tulu Sahitya Akademi and the Kodava Sahitya Akademi promote their respective languages.[citation needed]

Government and administration

[edit]Karnataka has a parliamentary system of government with two democratically elected houses, the Legislative Assembly and the Legislative Council. The Legislative Assembly consists of 224 members who are elected for five-year terms.[119] The Legislative Council is a permanent body of 75 members with one-third (25 members) retiring every two years.[119]

The government of Karnataka is headed by the Chief Minister who is chosen by the ruling party members of the Legislative Assembly. The Chief Minister, along with the council of ministers, executes the legislative agenda and exercises most of the executive powers.[120] However, the constitutional and formal head of the state is the Governor who is appointed for a five-year term by the President of India on the advice of the Union government.[121] The people of Karnataka also elect 28 members to the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Indian Parliament.[122] The members of the state Legislative Assembly elect 12 members to the Rajya Sabha, the upper house of the Indian Parliament.[citation needed]

For administrative purposes, Karnataka has been divided into four revenue divisions, 49 sub-divisions, 31 districts, 175 taluks and 745 hoblies / revenue circles.[123] The administration in each district is headed by a Deputy Commissioner who belongs to the Indian Administrative Service and is assisted by a number of officers belonging to Karnataka state services. The Superintendent of Police, an officer belonging to the Indian Police Service and assisted by the officers of the Karnataka Police Service, is entrusted with the responsibility of maintaining law and order and related issues in each district. The Deputy Conservator of Forests, an officer belonging to the Indian Forest Service, is entrusted with the responsibility of managing forests, environment and wildlife of the district, he will be assisted by the officers belonging to Karnataka Forest Service and officers belonging to Karnataka Forest Subordinate Service. Sectoral development in the districts is looked after by the district head of each development department such as Public Works Department, Health, Education, Agriculture, Animal Husbandry, etc. The judiciary in the state consists of the Karnataka High Court (Attara Kacheri) in Bengaluru, Hubli–Dharwad, and Kalaburagi, district and session courts in each district and lower courts and judges at the taluk level.[citation needed]

Politics in Karnataka has been dominated by three political parties, the Indian National Congress, the Janata Dal (Secular) and the Bharatiya Janata Party.[124] Politicians from Karnataka have played prominent roles in federal government of India with some of them having held the high positions of Prime Minister and Vice-President. Border disputes involving Karnataka's claim on the Kasaragod[125] and Solapur[126] districts and Maharashtra's claim on Belagavi are ongoing since the states reorganisation.[127] The official emblem of Karnataka has a Ganda Berunda in the centre. Surmounting this are four lions facing the four directions, taken from the Lion Capital of Ashoka at Sarnath. The emblem also carries two Sharabhas with the head of an elephant and the body of a lion.[citation needed]

Economy

[edit]

Karnataka had an estimated GSDP (Gross State Domestic Product) of about US$115.86 billion in the 2014–15 fiscal year.[128] The state registered a GSDP growth rate of 7% for the year 2014–2015.[129] Karnataka's contribution to India's GDP in the year 2014–15 was 7.54%.[128] With GDP growth of 17.59% and per capita GDP growth of 16.04%, Karnataka is on the 6th position among all states and union territories.[130][131] In an employment survey conducted for the year 2013–2014, the unemployment rate in Karnataka was 1.8% compared to the national rate of 4.9%.[132] In 2011–2012, Karnataka had an estimated poverty ratio of 20.91% compared to the national ratio of 21.92%.[133] In 2024, Karnataka had a multi-dimensional poverty rate of 5.67%, compared to the all India average of 11.28%.[134]

Nearly 56% of the workforce in Karnataka is engaged in agriculture and related activities.[135] A total of 12.31 million hectares of land, or 64.6% of the state's total area, is cultivated.[136] Much of the agricultural output is dependent on the southwest monsoon as only 26.5% of the sown area is irrigated.[136]

According to most recent data, Karnataka is considered the third richest state in India.[137]

Karnataka is the manufacturing hub for some of the largest public sector industries in India, including Hindustan Aeronautics Limited, National Aerospace Laboratories, Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited, Bharat Earth Movers Limited and HMT (formerly Hindustan Machine Tools), which are based in Bengaluru. Many of India's premier science and technology research centres, such as Indian Space Research Organisation, Central Power Research Institute, Bharat Electronics Limited and the Central Food Technological Research Institute, are also headquartered in Karnataka. Mangalore Refinery and Petrochemicals Limited is an oil refinery, located in Mangalore.[citation needed]

The state has also begun to invest heavily in solar power centered on the Pavagada Solar Park. As of December 2017, the state has installed an estimated 2.2 gigawatts of block solar panelling and in January 2018 announced a tender to generate a further 1.2 gigawatts in the coming years: Karnataka Renewable Energy Development suggests that this will be based on 24 separate systems (or 'blocks') generating 50 megawatts each.[138][139][140]

Since the 1980s, Karnataka has emerged as the pan-Indian leader in the field of IT (information technology). In 2007, there were nearly 2,000 firms operating in Karnataka. Many of them, including two of India's biggest software firms, Infosys and Wipro, are also headquartered in the state.[141] Exports from these firms exceeded ₹500 billion (equivalent to ₹1.6 trillion or US$19 billion in 2023) in 2006–07, accounting for nearly 38% of all IT exports from India.[141] The Nandi Hills area in the outskirts of Devanahalli is the site of the upcoming $22 billion, 50 km2 BIAL IT Investment Region, one of the largest infrastructure projects in the history of Karnataka.[142] All this has earned the state capital, Bengaluru, the sobriquet Silicon Valley of India.[143][144][145]

Karnataka also leads the nation in biotechnology. It is home to India's largest biocluster, with 60% of the country's biotechnology firms being based here.[146][147][148] The state has 18,000 hectares of land under flower cultivation, an upcoming industry which supplies flowers and ornamental plants worldwide.[149][150]

Seven of India's banks, Canara Bank, Syndicate Bank, Corporation Bank, Vijaya Bank, Karnataka Bank, ING Vysya Bank and the State Bank of Mysore originated in this state.[151] The coastal districts of Udupi and Dakshina Kannada have a branch for every 500 persons—the best distribution of banks in India.[152] In March 2002, Karnataka had 4767 branches of different banks with each branch serving 11,000 persons, which is lower than the national average of 16,000.[153]

A majority of the silk industry in India is headquartered in Karnataka, much of it in Doddaballapura in Bengaluru Rural district and the state government intends to invest ₹700 million (equivalent to ₹1.4 billion or US$17 million in 2023) in a "Silk City" at Muddenahalli in Chikkaballapura district.[154][155][156]

Karnataka also produces silver. The silver production of the state in 2018–19 was 214 kg whereas in 2019–20 it was 187 kg and in 2020–21 the silver production was 120 kg.[157]

Karnataka has the only village in the country which produces authentic Indian national flags according to manufacturing process and specifications for the flag are laid out by the Bureau of Indian Standards at Hubli.[158]

Transport

[edit]Air transport in Karnataka, as in the rest of the country, is still a fledgling but fast expanding sector. Karnataka has airports at Bengaluru, Mangalore, Belgaum, Hubli, Hampi, Bellary, Gulbarga, and Mysore with international operations from Bengaluru and Mangalore airports.[159][160] Shimoga and Bijapur airports are being built under the UDAN Scheme.[161][162][163][160]

Karnataka has a railway network with a total length of approximately 3,089 km (1,919 mi). Until the creation of the South-Western Railway Zone headquartered at Hubli in 2003, the railway network in the state was in the Southern Railway zone, South-Central Railway Zone and Western Railway zone. Several parts of the state now come under the South Western Railway zone with 3 Railway Divisions at Bengaluru, Mysore, Hubli, with the remainder under the Southern Railway zone and Konkan Railway Zone, which is considered one of India's biggest railway projects of the century due to the difficult terrain.[164] Bengaluru and other cities in the state are well-connected with intrastate and inter-state destinations.[citation needed]

Karnataka has 11 ports, including the New Mangalore Port, a major port and ten minor ports, of which three were operational in 2012.[165] The New Mangalore port was incorporated as the ninth major port in India on 4 May 1974.[166] This port handled 32.04 million tonnes of traffic in the fiscal year 2006–07 with 17.92 million tonnes of imports and 14.12 million tonnes of exports. The port also handled 1015 vessels including 18 cruise vessels during the year 2006–07. Foreigners can enter Mangalore through the New Mangalore Port with the help of Electronic visa (e-visa).[167] Cruise ships from Europe, North America and UAE arrive at New Mangalore Port to visit the tourist places across Coastal Karnataka.[168][169] The port of Mangalore is among the 4 major ports of India that receive over 25 international cruise ships every year.[170]

The total lengths of National Highways and State Highways in Karnataka are 3,973 and 9,829 km (2,469 and 6,107 mi), respectively.[171][172]

The state transport corporations, transports an average of 2.2 million passengers daily and employs about 25,000 people.[173] The Karnataka State Road Transport Corporation (KSRTC) and The Bengaluru Metropolitan Transport Corporation (BMTC) headquartered in Bengaluru, The Kalyana Karnataka Road Transport Corporation (KKRTC) headquartered in Gulbarga, and The North Western Karnataka Road Transport Corporation (NWKRTC) headquartered in Hubli are the 4 state-owned transport corporations.[citation needed]

Culture

[edit]The diverse linguistic and religious ethnicities that are native to Karnataka, combined with their long histories, have contributed immensely to the varied cultural heritage of the state. Apart from Kannadigas, Karnataka is home to Tuluvas, Kodavas and Konkanis. Minor populations of Tibetan Buddhists and tribes like the Soligas, Yeravas, Todas and Siddhis also live in Karnataka. The traditional folk arts cover the entire gamut of music, dance, drama, storytelling by itinerant troupes, etc. Yakshagana of Tulu Nadu, Uttara Kannada, and Malnad regions Karnataka, a classical dance drama, is one of the major theatrical forms of Karnataka. Contemporary theatre culture in Karnataka remains vibrant with organisations like Ninasam, Ranga Shankara, Rangayana and Prabhat Kalavidaru continuing to build on the foundations laid by Gubbi Veeranna, T. P. Kailasam, B. V. Karanth, K V Subbanna, Prasanna and others.[175] Veeragase, Kamsale, Kolata and Dollu Kunitha are popular dance forms. The Mysore style of Bharatanatya, nurtured and popularised by the likes of the legendary Jatti Tayamma, continues to hold sway in Karnataka, and Bengaluru also enjoys an eminent place as one of the foremost centres of Bharatanatya.[176]

Karnataka also has a special place in the world of Indian classical music, with both Karnataka[177] (Carnatic) and Hindustani styles finding place in the state, and Karnataka has produced a number of stalwarts in both styles. The Haridasa movement of the sixteenth century contributed significantly to the development of Karnataka (Carnatic) music as a performing art form. Purandara Dasa, one of the most revered Haridasas, is known as the Karnataka Sangeeta Pitamaha ('Father of Karnataka a.k.a. Carnatic music').[178] Celebrated Hindustani musicians like Gangubai Hangal, Mallikarjun Mansur, Bhimsen Joshi, Basavaraja Rajaguru, Sawai Gandharva and several others hail from Karnataka, and some of them have been recipients of the Kalidas Samman, Padma Bhushan and Padma Vibhushan awards. Noted Carnatic musicians include Violin T. Chowdiah, Veena Sheshanna, Mysore Vasudevachar, Doreswamy Iyengar and Thitte Krishna Iyengar.[citation needed]

Gamaka is another classical music genre based on Carnatic music that is practised in Karnataka. Kannada Bhavageete is a genre of popular music that draws inspiration from the expressionist poetry of modern poets. The Mysore school of painting has produced painters like Sundarayya, Tanjavur Kondayya, B. Venkatappa and Keshavayya.[179] Chitrakala Parishat is an organisation in Karnataka dedicated to promoting painting, mainly in the Mysore painting style.[citation needed]

Saree is the traditional dress of women in Karnataka. Women in Kodagu have a distinct style of wearing the saree, different from the rest of Karnataka. Dhoti, known as Panche in Karnataka, is the traditional attire of men. Shirt, Trousers and Salwar kameez are widely worn in Urban areas. Mysore Peta is the traditional headgear of southern Karnataka, while the pagadi or pataga (similar to the Rajasthani turban) is preferred in the northern areas of the state.[citation needed]

Rice and Ragi form the staple food in South Karnataka, whereas Jolada rotti, Sorghum is staple to North Karnataka. Bisi bele bath, Jolada rotti, Ragi mudde, Uppittu, Benne Dose, Masala Dose and Maddur Vade are some of the popular food items in Karnataka. Among sweets, Mysore Pak, Karadantu of Gokak and Amingad, Belgaavi Kunda and Dharwad pedha are popular. Apart from this, coastal Karnataka and Kodagu have distinctive cuisines of their own. Udupi cuisine of coastal Karnataka is popular all over India.[180]

Education

[edit]

As per the 2011 census, Karnataka had a literacy rate of 75.60%, with 82.85% of males and 68.13% of females in the state being literate.[181]

The Indian Institute of Science and Manipal Academy of Higher Education were ranked within the top 10 universities of India by NIRF 2020.[182] The state is home to some of the premier educational and research institutions of India such as the Indian Institute of Management – Bengaluru, the Indian Institute of Technology – Dharwad the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences – Bengaluru, the National Institute of Technology Karnataka – Surathkal and the National Law School of India University – Bengaluru.[183]

In March 2006, Karnataka had 54,529 primary schools with 252,875 teachers and 8.495 million students,[184] and 9498 secondary schools with 92,287 teachers and 1.384 million students.[184] There are three kinds of schools in the state, viz., government-run, private aided (financial aid is provided by the government) and private unaided (no financial aid is provided). The primary languages of instruction in most schools are Kannada and English.[185]

The syllabus taught in the schools is either of KSEEB (SSLC) and Pre-University Course (PUC) of the State Syllabus, the CBSE of the Central Syllabus, CISCE, IGCSE, IB, NIOS, etc., are all defined by the Department of Public Instruction of the Government of Karnataka. The state has two Sainik Schools – Kodagu Sainik School in Kodagu and Bijapur Sainik School in Bijapur.[187]

To maximise attendance in schools, the Karnataka Government has launched a mid-day meal scheme in government and aided schools in which free lunch is provided to the students.[188]

Statewide board examinations are conducted at the end of secondary education. Students who qualify are allowed to pursue a two-year pre-university course, after which they become eligible to pursue under-graduate degrees.[183]

There are 481-degree colleges affiliated with one of the universities in the state, viz. Bengaluru University, Rani Channamma University, Belagavi, Gulbarga University, Karnatak University, Kuvempu University, Mangalore University and Mysore University.[189] In 1998, the engineering colleges in the state were brought under the newly formed Visvesvaraya Technological University headquartered in Belgaum, whereas the medical colleges are run under the jurisdiction of the Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences headquartered in Bengaluru. Some of these baccalaureate colleges are accredited with the status of a deemed university. There are 186 engineering, 39 medical and 41 dental colleges in the state.[190] Udupi, Sringeri, Gokarna and Melkote are well-known places of Sanskrit and Vedic learning. In 2015 the Central Government decided to establish the first Indian Institute of Technology in Karnataka at Dharwad.[191] Tulu and Konkani[192] languages are taught as an optional subject in the twin districts of Dakshina Kannada and Udupi.[193]

Christ University, Jain University, CMR University, Dayananda Sagar University, PES University and REVA University are notable private universities in Karnataka.[citation needed]

On 9 February 2022, Karnataka shut its schools for three days after the regional administration-backed schools imposed a hijab ban, leading to widespread protests and violence. Other universities in the state began enforcing prohibitions after Hindu students, supported by right-wing Hindu groups, argued that if hijabs were allowed in classrooms, they should wear saffron shawls. On 5 February 2022, the Karnataka state government advised colleges to guarantee that "clothes which disturb equality, integrity, and public law and order should not be worn" in apparent support of schools' ability to enforce a ban.[194]

Media

[edit]The era of Kannada newspapers started in the year 1843 when Hermann Mögling, a missionary from Basel Mission, published the first Kannada newspaper called Mangaluru Samachara in Mangalore. The first Kannada periodical, Mysuru Vrittanta Bodhini was started by Bhashyam Bhashyacharya in Mysore. Shortly after Indian independence in 1948, K. N. Guruswamy founded The Printers (Mysuru) Private Limited and began publishing two newspapers, Deccan Herald and Prajavani. Presently The Times of India and Vijaya Karnataka are the largest-selling English and Kannada newspapers respectively.[195][196] A vast number of weekly, biweekly and monthly magazines are under publication in both Kannada and English. Vijay Karnataka, Vijayvani, Prajavani, Udaywani, Kannada Prabha are some popular dailies published from Karnataka.[197]

Doordarshan is the broadcaster of the Government of India and its channel DD Chandana is dedicated to Kannada. Prominent Kannada channels include Colors Kannada, Zee Kannada, Star Suvarna and Udaya TV.[198]

Karnataka occupies a special place in the history of Indian radio. In 1935, Aakashvani, the first private radio station in India, was started by Prof. M.V. Gopalaswamy in Mysore.[199] The popular radio station was taken over by the local municipality and later by All India Radio (AIR) and moved to Bengaluru in 1955. Later in 1957, AIR adopted the original name of the radio station, Aakashavani as its own. Some of the popular programs aired by AIR Bengaluru included Nisarga Sampada and Sasya Sanjeevini which were programs that taught science through songs, plays, and stories. These two programs became so popular that they were translated and broadcast in 18 different languages and the entire series was recorded on cassettes by the Government of Karnataka and distributed to thousands of schools across the state.[199] Karnataka has witnessed a growth in FM radio channels, mainly in the cities of Bengaluru, Mangalore and Mysore, which has become hugely popular.[200][201]

Sports

[edit]Karnataka's smallest district, Kodagu, is a major contributor to Indian field hockey, producing numerous players who have represented India at the international level.[202] The annual Kodava Hockey Festival is the largest hockey tournament in the world.[203] Bengaluru has hosted a WTA tennis event and, in 1997, it hosted the fourth National Games of India.[204] The Sports Authority of India, the premier sports institute in the country, and the Nike Tennis Academy are also situated in Bengaluru. Karnataka has been referred to as the cradle of Indian swimming because of its high standards in comparison to other states.[205]

One of the most popular sports in Karnataka is cricket. The state cricket team has won the Ranji Trophy seven times, second only to Mumbai in terms of success.[206] Chinnaswamy Stadium in Bengaluru regularly hosts international Cricket matches and is also the home of the National Cricket Academy, which was opened in 2000 to nurture potential international players. Many cricketers have represented India and in one international match held in the 1990s; players from Karnataka composed the majority of the national team.[207][208] The Royal Challengers Bengaluru, an Indian Premier League franchise, the Bengaluru Football Club, an Indian Super League franchise, the Bengaluru Yodhas, a Pro Wrestling League franchise, the Bengaluru Blasters, a Premier Badminton League franchise and the Bengaluru Bulls, a Pro Kabaddi League franchise are based in Bengaluru. The Karnataka Premier League is an inter-regional Twenty20 cricket tournament played in the state for eight seasons till 2019.[209] After 2019, it was replaced by Maharaja Trophy KSCA T20 tournament.[209]

Notable sportsmen from Karnataka include B.S. Chandrasekhar, Roger Binny, E. A. S. Prasanna, Anil Kumble, Javagal Srinath, Rahul Dravid, Venkatesh Prasad, Robin Uthappa, Vinay Kumar, Gundappa Vishwanath, Syed Kirmani, Stuart Binny, K. L. Rahul, Mayank Agarwal, Manish Pandey, Karun Nair, Ashwini Ponnappa, Mahesh Bhupathi, Rohan Bopanna, Prakash Padukone who won the All England Badminton Championships in 1980 and Pankaj Advani who has won three world titles in cue sports by the age of 20 including the amateur World Snooker Championship in 2003 and the World Billiards Championship in 2005.[210][211]

Bijapur district has produced some of the best-known road cyclists in the national circuit. Premalata Sureban was part of the Indian contingent at the Perlis Open '99 in Malaysia. In recognition of the talent of cyclists in the district, the state government laid down a cycling track at the B.R. Ambedkar Stadium at a cost of ₹4 million (US$47,000).[212]

Tourism

[edit]

By virtue of its varied geography and long history, Karnataka hosts numerous spots of interest for tourists. There is an array of ancient sculptured temples, modern cities, scenic hill ranges, forests and beaches. Karnataka has been ranked as the fourth most popular destination for tourism among the states of India.[215] Karnataka has the second highest number of nationally protected monuments in India, second only to Uttar Pradesh,[216] in addition to 752 monuments protected by the State Directorate of Archaeology and Museums. Another 25,000 monuments are yet to receive protection.[217][218]

The districts of the Western Ghats and the southern districts of the state have popular eco-tourism locations including Kudremukh, Madikeri and Agumbe. Karnataka has 25 wildlife sanctuaries and five national parks. Popular among them are Bandipura National Park, Bannerghatta National Park and Nagarhole National Park. The ruins of the Vijayanagara Empire at Hampi and the monuments of Pattadakal are on the list of UNESCO's World Heritage Sites. The cave temples at Badami and the rock-cut temples at Aihole representing the Badami Chalukyan style of architecture are also popular tourist destinations. The Hoysala temples at Beluru and Halebidu, which were built with Chloritic schist (soapstone) are proposed UNESCO World Heritage sites.[219] The Gol Gumbaz and Ibrahim Rauza are famous examples of the Deccan Sultanate style of architecture. The monolith of Gomateshwara Bahubali at Shravanabelagola is the tallest sculpted monolith in the world, attracting tens of thousands of pilgrims during the Mahamastakabhisheka festival.[220]

The waterfalls of Karnataka and Kudremukh are considered by some to be among the "1001 Natural Wonders of the World".[221] Jog Falls is India's tallest single-tiered waterfall with Gokak Falls, Unchalli Falls, Magod Falls, Abbey Falls and Shivanasamudra Falls among other popular waterfalls.[221]

Several popular beaches dot the coastline, including Murudeshwara, Gokarna, Malpe and Karwar. In addition, Karnataka is home to several places of religious importance. Several Hindu temples including the famous Udupi Sri Krishna Matha, the Marikamba Temple at Sirsi, the Kollur Mookambika Temple, the Sri Manjunatha Temple at Dharmasthala, Kukke Subramanya Temple, Janardhana and Mahakali Temple at Ambalpadi, Sharadamba Temple at Shringeri attract pilgrims from all over India. Most of the holy sites of Lingayatism, like Kudalasangama and Basavana Bagewadi, are found in northern parts of the state. Shravanabelagola, Mudabidri and Karkala are famous for Jain history and monuments. Jainism had a stronghold in Karnataka in the early medieval period with Shravanabelagola as its most important centre. The Shettihalli Rosary Church near Shettihalli, an example of French colonial Gothic architecture, is a rare example of a Christian ruin, is a popular tourist site.[222][223]

Karnataka has become a center of health care tourism and has the highest number of approved health systems and alternative therapies in India. Along with some ISO certified government-owned hospitals, private institutions which provide international-quality services, Hospitals in Karnataka treat around 8,000 health tourists every year.[224]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Kannada: Karnāṭaka, pronounced [kəɾᵊˈnaːʈəkɐː] kər-NAH-tə-kə

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Poem declared 'State song'". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- ^ "Poem declared 'State song'". The Hindu. 11 January 2004. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ "Rajneesh Goel Appointed As Karnataka's New Chief Secretary". NDTV. PTI. 22 November 2023. Archived from the original on 3 February 2024. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ "Karnataka CM swearing in ceremony live updates: 'In larger interest of party,' says DK Shivakumar on becoming deputy CM and Siddaramaiah as new CM". The Times of India. 18 May 2023. Archived from the original on 18 May 2023. Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- ^ "Protected Areas of India: State-wise break up of Wildlife Sanctuaries" (PDF). Wildlife Institute of India. Government of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ^ "Udupi-Chikmagalur: A constituency that's beset by problems". The Hindu. 18 March 2014. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- ^ "Figures at a glance" (PDF). 2011 Provisional census data. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- ^ 50th Report of the Commission for Linguistic Minorities in India (PDF). National Commissioner Linguistic Minorities. p. 123. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2016.

- ^ "THE KARNATAKA OFFICIAL LANGUAGE ACT, 1963" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ "MOSPI State Domestic Product, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India". 15 March 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ "India: Subnational HDI". Global Data Labs. Retrieved 8 June 2025.

- ^ "Appendix-A: Detailed tables, Table (7): Literacy rate (in per cent) of persons of different age groups for each State/UT (persons, age-group (years): 7 & above, rural+urban (column 6))". Annual Report, Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) (July 2023 – June 2024) (PDF). National Sample Survey Office, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India. 23 September 2024. pp. A-10.

- ^ Huq, Iteshamul, ed. (2015). "Introduction" (PDF). A Handbook of Karnataka (Fifth ed.). Karnataka Gazetteer Department. p. 48. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 May 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ "Population" (PDF).

- ^ a b Gross State Domestic Product (Current Prices) (Report). Government of India. Archived from the original on 26 November 2024. Retrieved 1 November 2024.

- ^ Per Capita Net State Domestic Product (Current Prices) (Report). Government of India. Retrieved 1 November 2024.

- ^ "Business News: Business News India, Business News Today, Latest Finance News, Business News Live". Financialexpress. 4 April 2024. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Census Reference Tables, B-Series - Area". censusindia.gov.in. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- ^ "Seven Indian villages where people speak in Sanskrit". 24 September 2017. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ^ "Know about these 4 Indian villages where Sanskrit is still their first language". Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ^ "Five Indian villages where Sanskrit is spoken". Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ^ See Lord Macaulay's life of Clive and James Talboys Wheeler: Early History of British India, London (1878) p.98. The principal meaning is the western half of this area, but the rulers there controlled the Coromandel Coast as well.

- ^ Paddayya, K.; et al. (10 September 2002). "Recent findings on the Acheulian of the Hunsgi and Baichbal valleys, Karnataka, with special reference to the Isampur excavation and its dating". Current Science. 83 (5): 641–648.

- ^ S. Ranganathan. "THE Golden Heritage of Karnataka". Department of Metallurgy. Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore. Archived from the original on 21 January 2007. Retrieved 7 June 2007.

- ^ "Trade". The British Museum. Archived from the original on 26 May 2007. Retrieved 6 May 2007.

- ^ From the Talagunda inscription (B. L. Rice in Kamath (2001), p. 30.)

- ^ Moares (1931), p. 10.

- ^ Adiga and Sheik Ali in Adiga (2006), p. 89.

- ^ Ramesh (1984), pp. 1–2.

- ^ From the Halmidi inscription (Ramesh 1984, pp. 10–11.)

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 10.

- ^ The Chalukyas hailed from present-day Karnataka (Keay (2000), p. 168.)

- ^ The Chalukyas were native Kannadigas (N. Laxminarayana Rao and S. C. Nandinath in Kamath (2001), p. 57.)

- ^ Altekar (1934), pp. 21–24.

- ^ Masica (1991), pp. 45–46.

- ^ Balagamve in Mysore territory was an early power centre (Cousens (1926), pp. 10, 105.)

- ^ Tailapa II, the founder king was the governor of Tardavadi in modern Bijapur district, under the Rashtrakutas (Kamath (2001), p. 101.).

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 115.

- ^ Foekema (2003), p. 9.

- ^ a b Sastri (1955), p.164

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 132–134.

- ^ Sastri (1955), pp. 358–359, 361.

- ^ Foekema (1996), p. 14.

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 122–124.

- ^ Kāmat, Sūryanātha. A concise history of Karnataka: from pre-historic times to the present. OCLC 993095629.

- ^ Prof K.A.N. Sastri, History of South India pp 355–366

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 157–160.

- ^ Kulke and Rothermund (2004), p. 188.

- ^ "The Hindu: A grand dream". 1 July 2003. Archived from the original on 1 July 2003. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 190–191.

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 201.

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 202.

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 207.

- ^ Jain, Dhanesh; Cardona, George (2003). Jain, Dhanesh; Cardona, George (eds.). The Indo-Aryan languages. Routledge language family series. Vol. 2. Routledge. p. 757. ISBN 978-0-7007-1130-7.

- ^ Pinto, Pius Fidelis (1999). History of Christians in coastal Karnataka, 1500–1763 A.D. Mangalore: Samanvaya Prakashan. p. 124.

- ^ A History of India by Burton Stein p.190

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 171.

- ^ a b Kamath (2001), pp. 171, 173, 174, 204.

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 231–234.

- ^ "Rani Chennamma of Kittur". Archived from the original on 18 April 2017.

- ^ Kamath, Suryanath (20 May 2007). "The rising in the south". The Printers (Mysore) Private Limited. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

- ^ Ninan, Prem Paul (1 November 2005). "History in the making". Deccan Herald. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ Gowda, Chandan (15 September 2010). "Visvesvaraya, an engineer of modernity". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Gupta, Jyoti Bhusan Das, ed. (2007). Science, Technology, Imperialism and War. History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization. XV(1). Pearson Longman. p. 247.

- ^ Menon, Parvathi. "Karnataka's agony". The Frontline, Volume 18 – Issue 17, 18–31 August 2001. Frontline. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2007.

- ^ "Hydropower generation doubled in 5 yrs but poor monsoon brings bad news". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 24 October 2024.

- ^ "India - Karnataka Irrigation Project". World Bank.

- ^ a b Ramachandra T.V. & Kamakshi G. "Bioresource Potential of Karnataka" (PDF). Technical Report No. 109, November 2005. Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 June 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2007.

- ^ Naha, K.; Srinivasan, R.; Jayaram, S. (1990). "Structural evolution of the Peninsular Gneiss — an early Precambrian migmatitic complex from South India". Geologische Rundschau. 79 (1): 99–109. Bibcode:1990GeoRu..79...99N. doi:10.1007/BF01830449. ISSN 0016-7835. S2CID 140553127. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ Dey, Sukanta (2015). "Chapter 19 Geological history of the Kaladgi–Badami and Bhima basins, south India: sedimentation in a Proterozoic intracratonic setup". Geological Society, London, Memoirs. 43 (1): 283–296. Bibcode:2015GSLMm..43..283D. doi:10.1144/M43.19. ISSN 0435-4052. S2CID 140664449. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ Radhakrishna, B. P. (1997). Geology of Karnataka. R. Vaidyanadhan (2nd ed.). Bangalore [India]: Geological Society of India. ISBN 81-85867-08-9. OCLC 39707803.

- ^ a b National Informatics Centre. "Traditional Soil Groups of Karnataka and their Geographic Distribution". Official Website of the Department of Agriculture, Govt. of Karnataka. Govt. of Karnataka. Retrieved 25 March 2007.

- ^ a b c "Forest Survey of India- Karnataka" (PDF). Forest Survey of India. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- ^ India. Directorate of Economics and Statistics (2015). Agricultural statistics at a glance 2014 (1st ed.). New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-945965-0. OCLC 905588033.

- ^ "Karnataka – An Introduction". Official website of the Karnataka legislature. Archived from the original on 7 August 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ "Rainfall Statistics of Karnataka 2010" (PDF). Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Karnataka. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ "Rainfall Statistics of Karnataka 2014" (PDF). Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Karnataka. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 March 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ Agumbe's receiving the second highest rainfall in India is mentioned by Ghose, Arabinda. "Link Godavari, Krishna & Cauvery". The Central Chronicle, dated 2007-03-28. 2007, Central Chronicle. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 16 May 2007.

- ^ Kumar, Suresh; Raizada, A.; Biswas, H.; Srinivas, S.; Mondal, Biswajit (2016). "Application of indicators for identifying climate change vulnerable areas in semi-arid regions of India". Ecological Indicators. Navigating Urban Complexity: Advancing Understanding of Urban Social – Ecological Systems for Transformation and Resilience. 70: 507–517. Bibcode:2016EcInd..70..507K. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.06.041. ISSN 1470-160X. S2CID 89533768.

- ^ "Extremes of Temperature & Rainfall for Indian Stations (up to 2012)" (PDF). India Meteorological Department, Extremes of Temperature & Rainfall for Indian Stations (Up to 2012): 40. December 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ^ a b Statistics related to forests in Karnataka is provided by "Statistics". Online Webpage of the Forest Department. Government of Karnataka. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 6 May 2007.

- ^ "Seville 5, Internal Meeting of Expects, Proceedings, Pamplona, Spain, 23–27 October 2000" (PDF). UNESCO. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ a b c A Walk on the Wild Side, An Information Guide to National Parks and Wildlife Sanctuaries of Karnataka, Compiled and Edited by Nima Manjrekar, Karnataka Forest Department, Wildlife Wing, October 2000

- ^ "Wildlife Sanctuaries". ENVIS Centre on Wildlife & Protected Areas. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ Threatened Fauna of Karnataka Archived 27 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine By the Karnataka Forest Department

- ^ Endemic fauna of Karnataka Archived 27 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine By the Karnataka Forest Department

- ^ "List of City Corporations/Municipal Corporations in Karnataka- Directorate of Municipal Administration".

- ^ "City Municipal Council's | Directorate of Municipal Administration". www.municipaladmn.gov.in. Archived from the original on 16 July 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- ^ "Town Municipal Council's | Directorate of Municipal Administration". www.municipaladmn.gov.in. Archived from the original on 14 July 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- ^ "List of Town Panchayats in Karnataka - Directorate of Municipal Administration".

- ^ a b "Karnataka Population Sex Ratio in Karnataka Literacy rate data". Archived from the original on 7 August 2013.

- ^ "Envisaging a healthy growth". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 8 October 2010. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

- ^ Kanathanda, ManuAiyappa (18 October 2017). "Karnataka to standardize costs of medical tourism services". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ "Karnataka bets big on healthcare tourism". The Hindu Business Line, dated 2004-11-23. 2004, The Hindu. Archived from the original on 29 September 2008. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

- ^ "Ticking child healthcare time bomb". The Education World. Education World. Archived from the original on 17 March 2008. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

- ^ Gupta, Cherry (28 January 2025). "India's top 10 best-performing states in the Fiscal Health Index 2025". The Indian Express. Retrieved 20 February 2025.

- ^ "Population by religion community – 2011". Census of India, 2011. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015.

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 150–152

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 152–154.

- ^ Sastri (1955), p. 396.

- ^ Sastri (1955), p. 398.

- ^ "Dasara fest panel meets Thursday". The Times of India, dated 2003-07-22. Times Internet Limited. 22 July 2003. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 17 July 2007.

- ^ a b "Language – India, States and Union Territories" (PDF). Census of India 2011. Office of the Registrar General. pp. 12–14, 49. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 November 2018. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ "The Karnataka Local Authorities (Official Language) Act, 1981" (PDF). Official website of Government of Karnataka. Government of Karnataka. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2007. Retrieved 26 July 2007.

- ^ "Declaration of Telugu and Kannada as classical languages". Press Information Bureau. Ministry of Tourism and Culture, Government of India. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 31 October 2008.

- ^ "Karnataka Tulu Sahithya Academy". Archived from the original on 25 November 2015.

- ^ "Karnataka Beary Sahithya Academy". Archived from the original on 12 December 2016.

- ^ "Karnataka Konkani Sahithya Academy". Archived from the original on 22 December 2015.

- ^ Narasimhacharya (1988), pp. 12, 17.

- ^ "Jnanapeeta Award Recipients". www.karnataka.gov.in. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ "The anatomy of Indian literary prizes: Who writes the award-winning books in India?". Firstpost. 3 October 2018. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ India, Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner. "C-16 Population By Mother Tongue". censusindia.gov.in. Archived from the original on 22 November 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ Anthropological Survey of India (Department of Anthropology) (1980). Bulletin of the Anthropological Survey of India, Volume 25. Director, Anthropological Survey of India, Indian Museum. p. 41.

- ^ Raviprasad Kamila (13 November 2004). "Tulu Academy yet to realise its goal". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2007.

- ^ "News headlines". www.daijiworld.com. 14 July 2007. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ "Konkani script row may now reach Supreme Court". The Times of India. 2 February 2016. Archived from the original on 8 February 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ K.S. Rajyashree. "Kodava Speech Community: An Ethnolinguistic Study". Online webpage of languageindia.com. M. S. Thirumalai. Archived from the original on 25 June 2007. Retrieved 6 May 2007.

- ^ "Konkan Prabha released". Online webpage of The Deccan Herald, dated 2005-09-16. 2005, The Printers (Mysore) Private Ltd. Archived from the original on 2 March 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2007.

- ^ a b "Origin and Growth of Karnataka Legislature". The Government of Karnataka. Government of Karnataka. Archived from the original on 26 May 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2007.

- ^ Pylee, M. V. 2003. Constitutional government in India. New Delhi: S. Chand & Co, p. 365.

- ^ "The Head of the State is called the Governor who is the constitutional head of the state as the President is for the whole of India", Pylee, M. V. 2003. Constitutional government in India. New Delhi: S. Chand & Co, p. 357.

- ^ "Lok Sabha-Introduction". The Indian Parliament. Govt. of India. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 4 June 2007.

- ^ "Statistics – Karnataka state". The Forest Department. Government of Karnataka. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 4 June 2007.

- ^ "Karnataka Politics – Suspense till 27 January". OurKarnataka.com. OurKarnataka.Com, Inc. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 4 June 2007.

- ^ "Government not keen on solving Kasaragod dispute". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 24 October 2005. Archived from the original on 16 January 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ^ "Border row: Government told to find permanent solution". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 29 September 2006. Archived from the original on 1 October 2007. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ^ "Border dispute saves NCP the blushes". The Times of India. 26 September 2006. Archived from the original on 12 January 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ a b "Industrial Development & Economic Growth in Karnataka". Indian Brand Equity Foundation. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016.

- ^ "State and district domestic product of Karnataka" (PDF). Directorate of Economics and Statistics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 July 2015.

- ^ "Indian states by GDP Growth". Statistics Times. Archived from the original on 8 August 2015. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ "Indian states by GDP per capita Growth". Statistics Times. Archived from the original on 21 August 2015. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ "Report on employment-unemployment survey" (PDF). Ministry of Labour and Employment. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ^ "Table 162, Number and Percentage of Population Below Poverty Line". Reserve Bank of India, Government of India. 2013. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ^ List of Indian states and union territories by poverty rate#:~:text=Mobile view-,"MULTIDIMENSIONAL POVERTY IN INDIA SINCE 2005-06",-(PDF).

- ^ "Karnataka Human Development Report 2005" (PDF). The Planning Commission. Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2007. Retrieved 4 June 2007.

- ^ a b "Karnataka Agricultural Policy 2006" (PDF). Department of Agriculture. Government of Karnataka. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 June 2007. Retrieved 4 June 2007.

- ^ GUpta, Cherry (21 February 2025). "Top 10 richest states in India by GDSP and GDP per capita, as of 2024". The Indian Express. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ^ "Karnataka: KREDL tenders 1.2 GW of solar PV". February 2018. Archived from the original on 2 February 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2018., KREDL tenders 1.2GW of solar PV

- ^ "Juwi baut 40-Megawatt-Park in Indien Archived 21 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine". Energie-Allee, issue of 2017, september. Retrieved 4 February 2019. (german) (pdf)

- ^ Pearson, Natalie Obiko (9 October 2014). "Kotak Mahindra, EIB to Invest in India's SolarArise". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ a b "IT exports from Karnataka cross Rs 50k cr". The Financial Express, dated 2007-05-22. 2007: Indian Express Newspapers (Mumbai) Ltd. Archived from the original on 12 February 2008.

- ^ "Karnataka / Bangalore News: State Cabinet approves IT park near Devanahalli airport". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 29 January 2010. Archived from the original on 5 April 2010. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- ^ "India in Business". Ministry of External affairs. Government of India. Archived from the original on 5 August 2007. Retrieved 11 June 2007.

- ^ "India's silicon valley 'living the dream'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Kar, Suparna (1 April 2016). "Locating Bengaluru as India's Silicon Valley". Artha - Journal of Social Sciences. 15 (2): 49. doi:10.12724/ajss.37.3. ISSN 0975-329X.

- ^ "Bangalore tops biocluster list with Rs 1,400-cr revenue". The Hindu Business Line, dated 2006-06-08. 2006, The Hindu Business Line. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007.

- ^ "Karnataka aims to become $50 billion bioeconomy by 2025". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ "Karnataka aims at $50 billion bio-economy by 2025". The Indian Express. 21 November 2020. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Raggi Mudde (17 July 2007). "Floriculture". www.Karnataka.com. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ Tejaswi, Mini; Tejaswibengaluru, Mini (23 February 2021). "Karnataka set to add value to its flower power". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Ravi Sharma (21 October 2005). "Building on a strong base". The Frontline. Frontline. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

- ^ Ravi Sharma (1 August 2003). "A pioneer's progress". The Frontline volume 20 issue 15. Frontline. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

- ^ "State/Union Territory-Wise Number of Branches of Scheduled Commercial Banks and Average Population Per Bank Branch – March 2002" (PDF). Online webpage of the Reserve Bank of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2007. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

- ^ "Silk city to come up near B'lore". Deccanherald.com. 17 October 2009. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ^ "Karnataka silk weavers fret over falling profits due to globalisation". Sify.com. 27 June 2009. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- ^ Prakash, K. Bhagya (6 October 2019). "Odds galore, but Karnataka's silk city Ramanagara survives". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "Production of silver" (PDF).

- ^ "Karnataka Khadi Gramodyog Samyukta Sangh (Federation), Hubli". Khadifederation.com. Archived from the original on 31 October 2007. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ^ "5 airports to be functional soon". Online Webpage of The Deccan Herald, dated 2007-06-05. 2007, The Printers (Mysore) Private Ltd. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 29 June 2007.

- ^ a b Moudgal, Sandeep (4 October 2021). "Raichur: Four greenfield airports may be ready in 3-4 years in Karnataka". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Poovanna, Sharan (15 June 2020). "Karnataka's Shivamogga airport to be completed in a year". Livemint. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "Vijayapura airport gets Karnataka cabinet nod, 18-month deadline to start operations". The New Indian Express. 10 July 2020. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ "Karnataka to get brand-new airport at Vijayapura". Bangalore Mirror. 16 February 2021. Archived from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ "Prime Minister to Dedicate Konkan Railway Line to Nation on 1 May". Press Information Bureau. Government of India. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

- ^ Feedback Infrastructure Services (May 2012). "Prefeasibility Report on Development of Captive Port at Padubidri" (PDF). Government of Karnataka, Infrastructure Development Department. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ^ "Brief history". New Mangalore Port Trust. Archived from the original on 28 November 2016.

- ^ "Foreigners can enter India through five ports on e-visa". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 5 December 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ "Nautica and Norwegian Star cruise through M'luru coast". Deccan Herald. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ "Aida Aura arrives in Mangaluru". Deccan Chronicle. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ "NMP draws up big plans to ramp up cruise tourism". The Times of India. 11 September 2019. Archived from the original on 6 November 2019. Retrieved 6 October 2019.