Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Presidency of Barack Obama

View on Wikipedia

Official portrait, 2012 | |

| Presidency of Barack Obama January 20, 2009 – January 20, 2017 | |

Vice President | |

|---|---|

| Cabinet | Full list |

| Party | Democratic |

| Election | |

| Seat | White House |

|

| |

| Archived website Library website | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal

Illinois State Senator and U.S. Senator from Illinois 44th President of the United States

Tenure

|

||

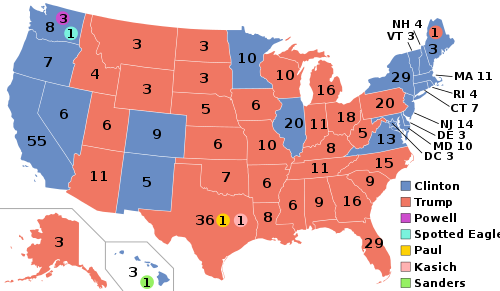

Barack Obama's tenure as the 44th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 2009, and ended on January 20, 2017. Obama, a Democrat from Illinois, took office following his victory over Republican nominee John McCain in the 2008 presidential election. Four years later, in the 2012 presidential election, he defeated Republican nominee Mitt Romney, to win re-election. Alongside Obama's presidency, the Democratic Party also held their majorities in the House of Representatives during the 111th U.S. Congress following the 2008 elections, attained an overall federal government trifecta. Obama is the first African American president, the first multiracial president, the first non-white president,[a] and the first president born in Hawaii. Obama was constitutionally limited to two terms (the second re-elected Democrat President to be so) and was succeeded by Republican Donald Trump, who won the 2016 presidential election against Obama's preferred successor, Hillary Clinton. Historians and political scientists rank him among the upper tier in historical rankings of American presidents.

Obama's accomplishments during the first 100 days of his presidency included signing the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009 relaxing the statute of limitations for equal-pay lawsuits;[2] signing into law the expanded Children's Health Insurance Program (S-CHIP); winning approval of a congressional budget resolution that put Congress on record as dedicated to dealing with major health care reform legislation in 2009; implementing new ethics guidelines designed to significantly curtail the influence of lobbyists on the executive branch; breaking from the Bush administration on a number of policy fronts, except for Iraq, in which he followed through on Bush's Iraq withdrawal of US troops;[3] supporting the UN declaration on sexual orientation and gender identity; and lifting the 7½-year ban on federal funding for embryonic stem cell research.[4] Obama also ordered the closure of the Guantanamo Bay detention camp, in Cuba, though it remains open. He lifted some travel and money restrictions to the island.[3]

Obama signed many landmark bills into law during his first two years in office. The main reforms include: the Affordable Care Act, sometimes referred to as "the ACA" or "Obamacare", the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, and the Don't Ask, Don't Tell Repeal Act of 2010. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act and Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act served as economic stimuli amidst the Great Recession. After a lengthy debate over the national debt limit, he signed the Budget Control Act of 2011 and the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012. In foreign policy, he increased US troop levels in Afghanistan, reduced nuclear weapons with the United States–Russia New START treaty, and ended military involvement in the Iraq War. He gained widespread praise for ordering Operation Neptune Spear, the raid that killed Osama bin Laden, who was responsible for the September 11 attacks. In 2011, Obama ordered the drone-strike killing in Yemen of al-Qaeda operative Anwar al-Awlaki, who was an American citizen. He ordered military involvement in Libya in order to implement UN Security Council Resolution 1973, contributing to the overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi.

After winning re-election by defeating Republican opponent Mitt Romney, Obama was sworn in for a second term on January 20, 2013. During this term, he condemned the 2013 Snowden leaks as unpatriotic, but called for more restrictions on the National Security Agency (NSA) to address privacy issues. Obama also promoted inclusion for LGBT Americans. His administration filed briefs that urged the Supreme Court to strike down same-sex marriage bans as unconstitutional (United States v. Windsor and Obergefell v. Hodges); same-sex marriage was legalized nationwide in 2015 after the Court ruled so in Obergefell. He advocated for gun control in response to the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, indicating support for a ban on assault weapons, and issued wide-ranging executive actions concerning global warming and immigration. In foreign policy, he ordered military interventions in Iraq and Syria in response to gains made by ISIL after the 2011 withdrawal from Iraq, promoted discussions that led to the 2015 Paris Agreement on global climate change, drew down US troops in Afghanistan in 2016, initiated sanctions against Russia following its annexation of Crimea and again after interference in the 2016 US elections, brokered the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action nuclear deal with Iran, and normalized US relations with Cuba. Obama nominated three justices to the Supreme Court: Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan were confirmed as justices, while Merrick Garland was denied hearings or a vote from the Republican-majority Senate.

Major acts and legislation

[edit]|

Economic policy actions

Other domestic policy actions

|

Foreign policy actions

Supreme Court nominations

|

2008 election

[edit]

Barack Obama announced his candidacy for the Democratic nomination in the 2008 presidential election on February 10, 2007.[5] In June 2008, Obama secured the Democratic nomination.[6] Obama selected Senator Joe Biden of Delaware as his running mate, and the two were officially nominated at the 2008 Democratic National Convention.

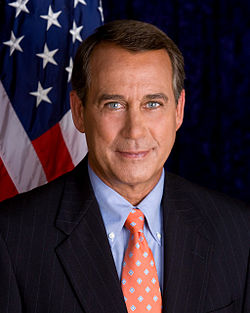

On November 4, Obama was projected to have secured the presidency. Obama won the presidential election with 365 electoral votes, while John McCain received 173. In the concurrent congressional elections, Democrats retained their expanded majorities in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, and Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid both remained in their posts. Republicans John Boehner and Mitch McConnell continued to serve as House Minority Leader and Senate Minority Leader, respectively.

Transition period, inauguration, and first 100 days

[edit]Transition period and inauguration

[edit]The presidential transition period began following Obama's victory in the 2008 U.S. presidential election, though Obama had chosen Chris Lu to begin planning for the transition in May 2008.[7] John Podesta, Valerie Jarrett, and Pete Rouse co-chaired the Obama-Biden Transition Project. During the transition period, Obama announced nominations for his cabinet and administration. In November 2008, Congressman Rahm Emanuel accepted Obama's offer to serve as White House Chief of Staff.[8]

Obama was inaugurated on January 20, 2009, officially assuming the presidency at 12:00 pm, EST,[9] and completing the oath of office at 12:05 pm, EST. He delivered his inaugural address immediately following his oath.[10] Obama's transition team was highly complimentary of the Bush administration's outgoing transition team, particularly with regards to national security, and some elements of the Bush-Obama transition were later codified into law.[7]

First 100 days

[edit]Within minutes of Obama's taking office, his chief of staff, Rahm Emanuel, issued an order suspending last-minute regulations and executive orders signed by his predecessor George W. Bush.[11] Some of the first actions of Obama's presidency focused on reversing measures taken by the Bush administration following the September 11 attacks.[12] In his first week in office, Obama signed Executive Order 13492 suspending all ongoing proceedings of the Guantanamo military commissions and ordering the Guantanamo detention facility to be shut down within the year.[13] Another order, Executive Order 13491, banned torture and other coercive techniques, such as waterboarding.[14] Obama also issued an executive order placing tighter restrictions on lobbying in the White House,[15] and rescinded the Mexico City Policy, which banned federal grants to international groups that provide abortion services or counseling.[16]

On January 29, Obama signed a bill for the first time in his presidency; the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009 revised the statute of limitations for filing pay discrimination lawsuits.[17] On February 3, he signed the Children's Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (CHIP), expanding CHIP's health care coverage from 7 million children to 11 million children.[18] On March 9, 2009, Obama lifted restrictions on federal funding of embryonic stem cell research.[19] Obama stated that, like Bush, he would employ signing statements if he deems a portion of a bill to be unconstitutional,[20] and he subsequently issued several signing statements.[21] Obama also signed the Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009, which added 2 million acres (8,100 km2) of land to the National Wilderness Preservation System,[22] as well as a law raising the cigarette pack tax by 62 cents (equivalent to $0.91 in 2024).[23]

On February 17, 2009, Obama signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) to address the Great Recession. The ARRA had been passed, after much debate, by both the House and Senate four days earlier. While it was originally intended to be a bipartisan bill, Congressional passage of the bill relied largely on Democratic votes, though three Republican senators voted for it.[24] The lack of Republican support for the bill, and the inability of Democrats to win that support, foreshadowed the gridlock and partisanship that continued throughout Obama's presidency.[24][25][26] The $787 billion bill combined tax breaks with spending on infrastructure projects, extension of welfare benefits, and education.[27][28]

Administration

[edit]Cabinet

[edit]Following his inauguration, Obama and the Senate worked to confirm his nominees to the United States Cabinet. Three Cabinet-level officers did not require confirmation: Vice President Joe Biden, whom Obama had chosen as his running mate at the 2008 Democratic National Convention, Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel, and Defense Secretary Robert Gates, whom Obama chose to retain from the previous administration.[29] An early list of suggestions came from Michael Froman, then an executive at Citigroup.[30] Obama described his Cabinet choices as a "team of rivals", and Obama chose several prominent public officials for Cabinet positions, including defeated rival Hillary Clinton as Secretary of State.[31] Obama nominated several former Clinton administration officials to the Cabinet and to other positions.[32] On April 28, 2009, the Senate confirmed former Kansas governor Kathleen Sebelius as Secretary of Health and Human Services, completing Obama's initial Cabinet.[33] During Obama's presidency, four Republicans served in Obama's Cabinet: Ray LaHood as Secretary of Transportation, Robert McDonald as Secretary of Veterans Affairs, and Gates and Chuck Hagel as Secretaries of Defense.

Notable non-Cabinet positions

[edit]- Counselor to the President

- Pete Rouse (2011–2014)

- John Podesta (2014–2015)

- Senior Advisor to the President

- Valerie Jarrett (2009–2017)

- Pete Rouse (2009–2010)

- David Axelrod (2009–2011)

- David Plouffe (2011–2013)

- Daniel Pfeiffer (2013–2015)

- Brian Deese (2015–2017)

- Shailagh Murray (2015–2017)

- White House Deputy Chief of Staff

- Jim Messina (2009–2011)

- Mona Sutphen (2009–2011)

- Nancy-Ann DeParle (2011–2013)

- Alyssa Mastromonaco (2011–2014)

- Mark B. Childress (2012–2014)

- Rob Nabors (2013–2015)

- Anita Decker Breckenridge (2014–2017)

- Kristie Canegallo (2014–2017)

- White House Press Secretary

- Robert Gibbs (2009–2011)

- Jay Carney (2011–2014)

- Josh Earnest (2014–2017)

- White House Communications Director

- Ellen Moran (2009)

- Anita Dunn (2009)

- Daniel Pfeiffer (2009–2013)

- Jennifer Palmieri (2013–2015)

- Jen Psaki (2015–2017)

- White House Counsel

- Greg Craig (2009–2010)

- Bob Bauer (2010–2011)

- Kathryn Ruemmler (2011–2014)

- Neil Eggleston (2014–2017)

- Chief of Staff to the First Lady of the United States

- Jackie Norris (2009–)

- Susan Sher (–2011)

- Tina Tchen (2011–2017)

†Appointed by President Bush

‡Originally appointed by President Bush, reappointed by President Obama

Judicial appointments

[edit]United States Supreme Court nominations

[edit]

There were three vacancies on the Supreme Court of the United States during Obama's tenure, but Obama made only two successful appointments. During the 111th Congress, when Democrats held a majority in the Senate, Obama successfully nominated two Supreme Court Justices:

- Sonia Sotomayor, replacing David Souter – 2009

- Elena Kagan, replacing John Paul Stevens – 2010

Justice Antonin Scalia died in February 2016, during the 114th Congress, which had a Republican majority in the Senate. In March 2016, Obama nominated Chief Judge Merrick Garland of the D.C. Circuit to fill Scalia's seat.[34] However, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, Judiciary Committee Chair Chuck Grassley, and other Senate Republicans argued that Supreme Court nominations should not be made during a presidential election year, and that the winner of the 2016 presidential election should instead appoint Scalia's replacement.[34][35] Garland's nomination remained before the Senate for longer than any other Supreme Court nomination in history,[36] and the nomination expired with the end of the 114th Congress.[37] President Donald Trump later nominated Neil Gorsuch to Scalia's former seat on the Supreme Court, and Gorsuch was confirmed by the Senate in April 2017.

Other courts

[edit]| Clinton | Bush | Obama | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supreme Court | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Appellate courts | 62 | 61 | 49 |

| District courts | 306 | 263 | 270 |

| Other courts | 9 | 4 | 10 |

Obama's presidency saw the continuation of battles between both parties over the confirmation of judicial nominees. Democrats continually accused Republicans of stalling nominees throughout Obama's tenure.[39] After several nomination battles, Senate Democrats in 2013 reformed the use of the filibuster so that it could no longer be used on executive or judicial nominations (excluding the Supreme Court).[40] Republicans took over the Senate after the 2014 elections, giving them the power to block any judicial nominee,[41] and the 114th Congress confirmed just 20 judicial nominees, the lowest number of confirmations since the 82nd Congress.[42] Obama's judicial nominees were significantly more diverse than those of previous administrations, with more appointments going to women and minorities.[39]

Domestic affairs

[edit]Health care reform

[edit]| Senate | House | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bill/Treaty | Dem. | Rep. | Dem. | Rep. |

| ARRA | 58–0 | 3–37 | 244–11 | 0–177 |

| ACA | 60–0 | 0–39 | 219–34 | 0–178 |

| Dodd-Frank | 57–1 | 3–35 | 234–19 | 3–173 |

| ACES | No vote | 211–44 | 8–168 | |

| DADTRA | 57–0 | 8–31 | 235–15 | 15–160 |

| DREAM | 52–5 | 3–36 | 208–38 | 8–160 |

| New START | 58–0 | 13–26 | No vote (treaty) | |

| 2010 TRA | 44–14 | 37–5 | 139–112 | 138–36 |

Once the stimulus bill was enacted in February 2009, health care reform became Obama's top domestic priority, and the 111th Congress passed a major bill that eventually became widely known as "Obamacare". Health care reform had long been a top priority of the Democratic Party, and Democrats were eager to implement a new plan that would lower costs and increase coverage.[44] In contrast to Bill Clinton's 1993 plan to reform health care, Obama adopted a strategy of letting Congress drive the process, with the House and Senate writing their own bills.[45] In the Senate, a bipartisan group of senators on the Finance Committee known as the Gang of Six began meeting with the hope of creating a bipartisan healthcare reform bill,[46] even though the Republican senators involved with the crafting of the bill ultimately came to oppose it.[45] In November 2009, the House passed the Affordable Health Care for America Act on a 220–215 vote, with only one Republican voting for the bill.[47] In December 2009, the Senate passed its own health care reform bill, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA or ACA), on a party-line, 60–39 vote.[48] Both bills expanded Medicaid and provided health care subsidies; they also established an individual mandate, health insurance exchanges, and a ban on denying coverage based on pre-existing conditions.[49] However, the House bill included a tax increase on families making more than $1 million per year and a public health insurance option, while the Senate plan included an excise tax on high-cost health plans.[49]

The 2010 Massachusetts Senate special election victory of Scott Brown seriously imperiled the prospects of a health care reform bill, as Democrats lost their 60-seat Senate super-majority.[50][51] The White House and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi engaged in an extensive campaign to convince both centrists and liberals in the House to pass the Senate's health care bill, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.[52] In March 2010, after Obama announced an executive order reinforcing the current law against spending federal funds for elective abortion services,[53] the House passed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.[54] The bill, which had passed the Senate in December 2009, did not receive a single Republican vote in either house.[54] On March 23, 2010, Obama signed the PPACA into law.[55] The New York Times described the PPACA as "the most expansive social legislation enacted in decades,"[55] while the Washington Post noted that it was the biggest expansion of health insurance coverage since the creation of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965.[54] Both houses of Congress also passed a reconciliation measure to make significant changes and corrections to the PPACA; this second bill was signed into law on March 30, 2010.[56][57] The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act became widely known as the Affordable Care Act (ACA) or "Obamacare".[58]

The Affordable Care Act faced considerable challenges and opposition after its passage, and Republicans continually attempted to repeal the law.[60] The law also survived two major challenges that went to the Supreme Court.[61] In National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, a 5–4 majority upheld the constitutionality of the Affordable Care Act, even though it made state Medicaid expansion voluntary. In King v. Burwell, a 6–3 majority allowed the use of tax credits in state-operated exchanges. The October 2013 launch of HealthCare.gov, a health insurance exchange website created under the provisions of the ACA, was widely criticized,[62] even though many of the problems were fixed by the end of the year.[63] The number of uninsured Americans dropped from 20.2% of the population in 2010 to 13.3% of the population in 2015,[64] though Republicans continued to oppose Obamacare as an unwelcome expansion of government.[65] Many liberals continued to push for a single-payer healthcare system or a public option,[52] and Obama endorsed the latter proposal, as well as an expansion of health insurance tax credits, in 2016.[66]

Wall Street reform

[edit]Risky practices among the major financial institutions on Wall Street were widely seen as contributing to the subprime mortgage crisis, the 2008 financial crisis, and the subsequent Great Recession, so Obama made Wall Street reform a priority in his first term.[67] On July 21, 2010, Obama signed the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, the largest financial regulatory overhaul since the New Deal.[68] The act increased regulation and reporting requirements on derivatives (particularly credit default swaps), and took steps to limit systemic risks to the US economy with policies such as higher capital requirements, the creation of the Orderly Liquidation Authority to help wind down large, failing financial institutions, and the creation of the Financial Stability Oversight Council to monitor systemic risks.[69] Dodd-Frank also established the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which was charged with protecting consumers against abusive financial practices.[70] On signing the bill, Obama stated that the bill would "empower consumers and investors," "bring the shadowy deals that caused the crisis to the light of day," and "put a stop to taxpayer bailouts once and for all."[71] Some liberals were disappointed that the law did not break up the country's largest banks or reinstate the Glass-Steagall Act, while many conservatives criticized the bill as a government overreach that could make the country less competitive.[71] Under the bill, the Federal Reserve and other regulatory agencies were required to propose and implement several new regulatory rules, and battles over these rules continued throughout Obama's presidency.[72] Obama called for further Wall Street reform after the passage of Dodd-Frank, saying that banks should have a smaller role in the economy and less incentive to make risky trades.[73] Obama also signed the Credit CARD Act of 2009, which created new rules for credit card companies.[74]

Climate change and the environment

[edit]During his presidency, Obama described global warming as the greatest long-term threat facing the world.[75] Obama took several steps to combat global warming, but was unable to pass a major bill addressing the issue, in part because many Republicans and some Democrats questioned whether global warming is occurring and whether human activity contributes to it.[76] Following his inauguration, Obama asked that Congress pass a bill to put a cap on domestic carbon emissions.[77] After the House passed the American Clean Energy and Security Act in 2009, Obama sought to convince the Senate to pass the bill as well.[78] The legislation would have required the US to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 17 percent by 2020 and by 83 percent by the middle of the 21st century.[78] However, the bill was strongly opposed by Republicans and neither it nor a separate proposed bipartisan compromise[77] ever came up for a vote in the Senate.[79] In 2013, Obama announced that he would bypass Congress by ordering the EPA to implement new carbon emissions limits.[80] The Clean Power Plan, unveiled in 2015, seeks to reduce US greenhouse gas emissions by 26 to 28 percent by 2025.[81] Obama also imposed regulations on soot, sulfur, and mercury that encouraged a transition away from coal as an energy source, but the falling price of wind, solar, and natural gas energy sources also contributed to coal's decline.[82] Obama encouraged this successful transition away from coal in large part due to the fact that coal emits more carbon than other sources of power, including natural gas.[82]

Obama's campaign to fight global warming found more success at the international level than in Congress. Obama attended the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference, which drafted the non-binding Copenhagen Accord as a successor to the Kyoto Protocol. The deal provided for the monitoring of carbon emissions among developing countries, but it did not include Obama's proposal to commit to cutting greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2050.[83] In 2014, Obama reached an agreement with China in which China pledged to reach peak carbon emission levels by 2030, while the US pledged to cut its emissions by 26–28 percent compared to its 2005 levels.[84] The deal provided momentum for a potential multilateral global warming agreement among the world's largest carbon emitters.[85] Many Republicans criticized Obama's climate goals as a potential drain on the economy.[85][86] At the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference, nearly every country in the world agreed to a landmark climate deal in which each nation committed lowering their greenhouse gas emissions.[87][88] The Paris Agreement created a universal accounting system for emissions, required each country to monitor its emissions, and required each country to create a plan to reduce its emissions.[87][89] Several climate negotiators noted that the US-China climate deal and the EPA's emission limits helped make the deal possible.[87] In 2016, the international community agreed to the Kigali accord, an amendment to the Montreal Protocol which sought to reduce the use of HFCs, organic compounds that contribute to global warming.[90]

From the beginning of his presidency, Obama took several actions to raise vehicle fuel efficiency in the United States. In 2009, Obama announced a plan to increase the Corporate Average Fuel Economy to 35 miles per US gallon (6.7 L/100 km)], a 40 percent increase from 2009 levels.[91] Both environmentalists and auto industry officials largely welcomed the move, as the plan raised national emission standards but provided the single national efficiency standard that auto industry officials group had long desired.[91] In 2012, Obama set even higher standards, mandating an average fuel efficiency of 54.5 miles per US gallon (4.32 L/100 km).[92] Obama also signed the "cash-for-clunkers" bill, which provided incentives to consumers to trade in older, less fuel-efficient cars for more efficient cars. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 provided $54 billion in funds to encourage domestic renewable energy production, make federal buildings more energy-efficient, improve the electricity grid, repair public housing, and weatherize modest-income homes.[93] Obama also promoted the use of plug-in electric vehicles, and 400,000 electric cars had been sold by the end of 2015.[94]

According to a report by The American Lung Association, there was a "major improvement" in air quality under Obama.[95]

Economy

[edit]| Year | Unemploy- ment[96] |

Real GDP Growth[97] |

US Government[98][99] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receipts | Outlays | Deficit | Debt | |||

| ending | Dec 31 (Calendar Year) | Sep 30 (Fiscal Year)[c] | ||||

| 2007* | 4.6% | 2.0% | $2.568 | $2.729 | − $0.161 | $5.0 |

| 2008* | 5.8% | 0.1% | $2.524 | $2.983 | − $0.459 | $5.8 |

| 2009 | 9.3% | −2.6% | $2.105 | $3.518 | − $1.413 | $7.5 |

| 2010 | 9.6% | 2.7% | $2.163 | $3.457 | − $1.294 | $9.0 |

| 2011 | 8.9% | 1.5% | $2.303 | $3.603 | − $1.300 | $10.1 |

| 2012 | 8.1% | 2.3% | $2.450 | $3.527 | − $1.077 | $11.3 |

| 2013 | 7.4% | 1.8% | $2.775 | $3.455 | − $0.680 | $12.0 |

| 2014 | 6.2% | 2.3% | $3.021 | $3.506 | − $0.485 | $12.8 |

| 2015 | 5.3% | 2.7% | $3.250 | $3.692 | − $0.442 | $13.1 |

| 2016 | 4.9% | 1.7% | $3.268 | $3.853 | − $0.585 | $14.2 |

Upon entering office, Obama focused on handling the 2008 financial crisis and the subsequent Great Recession that had begun before his election,[100][101] which was generally regarded as the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression.[102] On February 17, 2009, Obama signed into law a $787 billion economic stimulus bill that included spending for health care, infrastructure, education, various tax breaks and incentives, and direct assistance to individuals. The tax provisions of the law, including a $116 billion income tax cut, temporarily reduced taxes for 98% of taxpayers, bringing tax rates to their lowest levels in 60 years.[103][104] The Obama administration would later argue that the stimulus saved the United States from a "double-dip" recession.[105] Obama asked for a second major stimulus package in December 2009,[106] but no major second stimulus bill passed. Obama also launched a second bailout of US automakers, possibly saving General Motors and Chrysler from bankruptcy at the cost of $9.3 billion.[107][108] For homeowners in danger of defaulting on their mortgage due to the subprime mortgage crisis, Obama launched several programs, including HARP and HAMP.[109][110] Obama re-appointed Ben Bernanke as Chair of the Federal Reserve Board in 2009,[111] and appointed Janet Yellen to succeed Bernanke in 2013.[112] Short-term interest rates remained near zero for much of Obama's presidency, and the Federal Reserve did not raise interest rates during Obama's presidency until December 2015.[113]

There was a sustained increase of the US unemployment rate during the early months of the administration,[114] as multi-year economic stimulus efforts continued.[115][116] The unemployment rate reached a peak in October 2009 at 10.0%.[117] However, the economy added non-farm jobs for a record 75 straight months between October 2010 and December 2016, and the unemployment rate fell to 4.7% in December 2016.[118] The recovery from the Great Recession was marked by a lower labor force participation rate, some economists attributing the lower participation rate partially to an aging population and people staying in school longer, as well as long-term structural demographic changes.[119] The recovery also laid bare the growing income inequality in the United States,[120] which the Obama administration highlighted as a major problem.[121] The federal minimum wage increased during Obama's presidency to $7.25 per hour;[122] in his second term, Obama advocated for another increase to $12 per hour.[123]

GDP growth returned in the third quarter of 2009, expanding at a 1.6% pace, followed by a 5.0% increase in the fourth quarter.[124] Growth continued in 2010, posting an increase of 3.7% in the first quarter, with lesser gains throughout the rest of the year.[124] The country's real GDP grew by about 2% in 2011, 2012, 2013, and 2014, peaking at 2.9% in 2015.[125][126] In the aftermath of the recession, median household income (adjusted for inflation) declined during Obama's first term, before recovering to a new record high in his final year.[127] The poverty rate peaked at 15.1% in 2010 but declined to 12.7% in 2016, which was still higher than the 12.5% pre-recession figure of 2007.[128][129][130] The relatively small GDP growth rates in the United States and other developed countries following the Great Recession left economists and others wondering whether US growth rates would ever return to the levels seen in the second half of the twentieth century.[131][132]

Taxation

[edit]| Income bracket | Clinton[d] | Bush[e] | Obama[f] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bottom | 15% | 10% | 10% |

| 2nd | 28% | 15% | 15% |

| 3rd | 31% | 25% | 25% |

| 4th | 36% | 28% | 28% |

| 5th | – | 33% | 33% |

| 6th | – | – | 35% |

| Top | 39.6% | 35% | 39.6% |

Obama's presidency saw an extended battle over taxes that ultimately led to the permanent extension of most of the Bush tax cuts, which had been enacted between 2001 and 2003. Those tax cuts were set to expire during Obama's presidency since they were originally passed using a Congressional maneuver known as reconciliation, and had to fulfill the long-term deficit requirements of the "Byrd rule". During the lame duck session of the 111th Congress, Obama and Republicans wrangled over the ultimate fate of the cuts. Obama wanted to extend the tax cuts for taxpayers making less than $250,000 a year, while Congressional Republicans wanted a total extension of the tax cuts, and refused to support any bill that did not extend tax cuts for top earners.[134][135] Obama and the Republican Congressional leadership reached a deal that included a two-year extension of all the tax cuts, a 13-month extension of unemployment insurance, a one-year reduction in the FICA payroll tax, and other measures.[136] Obama ultimately persuaded many wary Democrats to support the bill, though Bernie Sanders and others continued to oppose it.[137][138] The $858 billion Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010 passed with bipartisan majorities in both houses of Congress and was signed into law by Obama on December 17, 2010.[137][139]

Shortly after Obama's 2012 re-election, Congressional Republicans and Obama again faced off over the final fate of the Bush tax cuts. Republicans sought to make all tax cuts permanent, while Obama sought to extend the tax cuts only for those making under $250,000.[140] Obama and Congressional Republicans came to an agreement on the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012, which made permanent the tax cuts for individuals making less than $400,000 a year (or less than $450,000 for couples).[140] For earnings greater than that amount, the income tax increased from 35% to 39.6%, which was the top rate before the passage of the Bush tax cuts.[141] The deal also permanently indexed the alternative minimum tax for inflation, limited deductions for individuals making more than $250,000 ($300,000 for couples), permanently set the estate tax exemption at $5.12 million (indexed to inflation), and increased the top estate tax rate from 35% to 40%.[141] Though many Republicans did not like the deal, the bill passed the Republican House in large part due to the fact that the failure to pass any bill would have resulted in the total expiration of the Bush tax cuts.[140][142]

Budget and debt ceiling

[edit]

US government debt grew substantially during the Great Recession, as government revenues fell. Obama largely rejected the austerity policies followed by many European countries.[143] US government debt grew from 52% of GDP when Obama took office in 2009 to 74% in 2014, with most of the growth in debt coming between 2009 and 2012.[125] In 2010, Obama ordered the creation of the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform (also known as the "Simpson-Bowles Commission") in order to find ways to reduce the country's debt.[144] The commission ultimately released a report that called for a mix of spending cuts and tax increases.[144] Notable recommendations of the report include a cut in military spending, a scaling back of tax deductions for mortgages and employer-provided health insurance, a raise of the Social Security retirement age, and reduced spending on Medicare, Medicaid, and federal employees.[144] The proposal never received a vote in Congress, but it served as a template for future plans to reduce the national debt.[145]

After taking control of the House in the 2010 elections, Congressional Republicans demanded spending cuts in return for raising the United States debt ceiling, the statutory limit on the total amount of debt that the Treasury Department can issue. The 2011 debt-ceiling crisis developed as Obama and Congressional Democrats demanded a "clean" debt-ceiling increase that did not include spending cuts.[146] Though some Democrats argued that Obama could unilaterally raise the debt ceiling under the terms of the Fourteenth Amendment,[147] Obama chose to negotiate with Congressional Republicans. Obama and Speaker of the House John Boehner attempted to negotiate a "grand bargain" to cut the deficit, reform entitlement programs, and re-write the tax code, but the negotiations eventually collapsed due to ideological differences between the Democratic and Republican leaders.[148][149][150] Congress instead passed the Budget Control Act of 2011, which raised the debt ceiling, provided for domestic and military spending cuts, and established the bipartisan Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction to propose further spending cuts.[151] As the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction failed to reach an agreement on further cuts, domestic and military spending cuts known as the "sequester" took effect starting in 2013.[152]

In October 2013, the government shut down for two weeks as Republicans and Democrats were unable to agree on a budget. House Republicans passed a budget that would defund Obamacare, but Senate Democrats refused to pass any budget that defunded Obamacare.[153] Meanwhile, the country faced another debt ceiling crisis. Ultimately the two sides agreed to a continuing resolution that re-opened the government and suspended the debt ceiling.[154] Months after passing the continuing resolution, Congress passed the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 and an omnibus spending bill to fund the government through 2014.[155] In 2015, after John Boehner announced that he would resign as Speaker of the House, Congress passed a bill that set government spending targets and suspended the debt limit until after Obama left office.[156]

LGBT rights

[edit]

During his presidency, Obama, Congress, and the Supreme Court all contributed to a major expansion of LGBT rights. In 2009, Obama signed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, which expanded hate crime laws to cover crimes committed because of the victim's sexual orientation.[157] In December 2010, Obama signed the Don't Ask, Don't Tell Repeal Act of 2010, which ended the military's policy of disallowing openly gay and lesbian people from openly serving in the United States Armed Forces.[158] Obama also supported the passage of ENDA, which would ban discrimination against employees on the basis of gender or sexual identity for all companies with 15 or more employees,[159] and the similar but more comprehensive Equality Act.[160] Neither bill passed Congress. In May 2012, Obama became the first sitting president to support same-sex marriage, shortly after Vice President Joe Biden had also expressed support for the institution.[161] The following year, Obama appointed Todd M. Hughes to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, making Hughes the first openly gay federal judge in US history.[162] In 2015, the Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution guarantees same-sex couples the right to marry in the case of Obergefell v. Hodges. The Obama Administration filed an amicus brief in support of gay marriage and Obama personally congratulated the plaintiff.[163] Obama also issued dozens of executive orders intended to help LGBT Americans,[164] including a 2010 order that extended full benefits to same-sex partners of federal employees.[165] A 2014 order prohibited discrimination against employees of federal contractors on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.[165] In 2015, Secretary of Defense Ash Carter ended the ban on women in combat roles,[166] and in 2016, he ended the ban on transgender individuals openly serving in the military.[167] On the international stage, Obama advocated for gay rights, particularly in Africa.[168]

Education

[edit]The Great Recession of 2008–09 caused a sharp decline in tax revenues in all cities and states. The response was to cut education budgets. Obama's $800 billion stimulus package included $100 billion for public schools, which every state used to protect its educational budget. However, in terms of sponsoring innovation, Obama and his Education Secretary Arne Duncan pursued K-12 education reform through the Race to the Top grant program. With over $15 billion of grants at stake, 34 states quickly revised their education laws according to the proposals of advanced educational reformers. In the competition points were awarded for allowing charter schools to multiply, for compensating teachers on a merit basis including student test scores, and for adopting higher educational standards. There were incentives for states to establish college and career-ready standards, which in practice meant adopting the Common Core State Standards Initiative that had been developed on a bipartisan basis by the National Governors Association, and the Council of Chief State School Officers. The criteria were not mandatory, they were incentives to improve opportunities to get a grant. Most states revised their laws accordingly, even though they realized it was unlikely they would when a highly competitive new grant. Race to the Top had strong bipartisan support, with centrist elements from both parties. It was opposed by the left wing of the Democratic Party, and by the right wing of the Republican Party, and criticized for centralizing too much power in Washington. Complaints also came from middle-class families, who were annoyed at the increasing emphasis on teaching to the test, rather than encouraging teachers to show creativity and stimulating students' imagination.[169][170][171]

Obama also advocated for universal pre-kindergarten programs,[172] and two free years of community college for everyone.[173] Through her Let's Move program and advocacy of healthier school lunches, First Lady Michelle Obama focused attention on childhood obesity, which was three times higher in 2008 than it had been in 1974.[174] In December 2015, Obama signed the Every Student Succeeds Act, a bipartisan bill that reauthorized federally mandated testing but shrank the federal government's role in education, especially with regard to troubled schools.[175] The law also ended the use of waivers by the Education Secretary.[175] In post-secondary education, Obama signed the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010, which ended the role of private banks in lending out federally insured student loans,[176] created a new income-based loan repayment plan known as Pay as You Earn, and increased the amount of Pell Grant awards given each year.[177] He also instituted new regulations on for-profit colleges, including a "gainful employment" rule that restricted federal funding from colleges that failed to adequately prepare graduates for careers.[178]

Immigration

[edit]From the beginning of his presidency, Obama supported comprehensive immigration reform, including a pathway to citizenship for many immigrants illegally residing in the United States.[179] However, Congress did not pass a comprehensive immigration bill during Obama's tenure, and Obama turned to executive actions. In the 2010 lame-duck session, Obama supported passage of the DREAM Act, which passed the House but failed to overcome a Senate filibuster in a 55–41 vote in favor of the bill.[180] In 2013, the Senate passed an immigration bill with a path to citizenship, but the House did not vote on the bill.[181][182] In 2012, Obama implemented the DACA policy, which protected roughly 700,000 illegal immigrants from deportation; the policy applies only to those who were brought to the United States before their 16th birthday.[183] In 2014, Obama announced a new executive order that would have protected another four million illegal immigrants from deportation,[184] but the order was blocked by the Supreme Court in a 4–4 tie vote that upheld a lower court's ruling.[185] Despite executive actions to protect some individuals, deportations of illegal immigrants continued under Obama. A record high of 400,000 deportations occurred in 2012, though the number of deportations fell during Obama's second term.[186] In continuation of a trend that began with the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, the percentage of foreign-born people living in the United States reached 13.7% in 2015, higher than at any point since the early 20th century.[187][188] After having risen since 1990, the number of illegal immigrants living in the United States stabilized at around 11.5 million individuals during Obama's presidency, down from a peak of 12.2 million in 2007.[189][190]

The nation's immigrant population hit a record 42.2 million in 2014.[191] In November 2015, Obama announced a plan to resettle at least 10,000 Syrian refugees in the United States.[192]

Energy

[edit]

Energy production boomed during the Obama administration.[193] An increase in oil production was driven largely by a fracking boom spurred by private investment on private land, and the Obama administration played only a small role in this development.[193] The Obama administration promoted the growth of renewable energy,[194] and solar power generation tripled during Obama's presidency.[195] Obama also issued numerous energy efficiency standards, contributing to a flattening of growth of the total US energy demand.[196] In May 2010, Obama extended a moratorium on offshore drilling permits after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, which was the worst oil spill in US history.[197][198] In December 2016, President Obama invoked the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act to ban offshore oil and gas exploration in large parts of the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans.[199]

During Obama's tenure, the battle over the Keystone XL Pipeline became a major issue, with advocates arguing that it would contribute to economic growth and environmentalists arguing that its approval would contribute to global warming.[200] The proposed 1,000-mile (1,600 km) pipeline would have connected Canada's oil sands with the Gulf of Mexico.[200] Because the pipeline crossed international boundaries, its construction required the approval of the US federal government, and the US State Department engaged in a lengthy review process.[200] President Obama vetoed a bill to construct the Keystone Pipeline in February 2015, arguing that the decision of approval should rest with the executive branch.[201] It was the first major veto of his presidency, and Congress was unable to override it.[202] In November 2015, Obama announced that he would not approve of the construction of the pipeline.[200] On vetoing the bill, he stated that the pipeline played an "overinflated role" in US political discourse and would have had relatively little impact on job creation or climate change.[200]

Drug policy and criminal justice reform

[edit]The Obama administration took a few steps to reform the criminal justice system at a time when many in both parties felt that the US had gone too far in incarcerating drug offenders,[203] and Obama was the first president since the 1960s to preside over a reduction in the federal prison population.[204] Obama's tenure also saw a continued decline of the national violent crime rate from its peak in 1991, though there was an uptick in the violent crime rate in 2015.[205][206] In October 2009, the US Department of Justice issued a directive to federal prosecutors in states with medical marijuana laws not to investigate or prosecute cases of marijuana use or production done in compliance with those laws.[207] In 2009, President Obama signed the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2010, which repealed a 21-year-old ban on federal funding of needle exchange programs.[208] In August 2010, Obama signed the Fair Sentencing Act, which reduced the sentencing disparity between crack cocaine and powder cocaine.[209] In 2012, Colorado and Washington became the first states to legalize non-medical marijuana,[210] and six more states legalized recreational marijuana by the time Obama left office.[211] Though any use of marijuana remained illegal under federal law, the Obama administration generally chose not to prosecute those who used marijuana in states that chose to legalize it.[212] In 2016, Obama announced that the federal government would phase out the use of private prisons.[213] Obama commuted the sentences of over 1,000 individuals, a higher number of commutations than any other president, and most of Obama's commutations went to nonviolent drug offenders.[214][215]

During Obama's presidency, there was a sharp rise in opioid mortality. Many of the deaths – then and now – result from fentanyl consumption where an overdose is more likely than with heroin consumption. And many people died because they were not aware of this difference or thought that they would administer themselves heroin or a drug mixture but actually used pure fentanyl.[216] Health experts criticized the government's response as slow and weak.[217][218]

Gun control

[edit]Upon taking office in 2009, Obama expressed support for reinstating the Federal Assault Weapons Ban; but did not make a strong push to pass it-or any new gun control legislation early on in his presidency.[219] During his first year in office, Obama signed into law two bills containing amendments reducing restrictions on gun owners, one which permitted guns to be transported in checked baggage on Amtrak trains[220] and another allowing the concealed carry of loaded firearms in National Parks, located in states where concealed carry was permitted.[221][222]

Following the December 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, Obama outlined a series of sweeping gun control proposals, urging Congress to reintroduce an expired ban on "military-style" assault weapons, impose limits on ammunition magazines to 10 rounds, require universal background checks for all domestic gun sales, ban the possession and sale of armor-piercing bullets and introduce harsher penalties for gun-traffickers.[223] Despite Obama's advocacy and subsequent mass shootings, no major gun control bill passed Congress during Obama's presidency. Senators Joe Manchin (D-WV) and Pat Toomey (R-PA) attempted to pass a more limited gun control measure that would have expanded background checks, but the bill was blocked in the Senate.[224]

Cybersecurity

[edit]Cybersecurity emerged as an important issue during Obama's presidency. In 2009, the Obama administration established United States Cyber Command, an armed forces sub-unified command charged with defending the military against cyber attacks.[225] Sony Pictures suffered a major hack in 2014, which the US government alleges originated from North Korea in retaliation for the release of the film The Interview.[226] China also developed sophisticated cyber-warfare forces.[227] In 2015, Obama declared cyber-attacks on the US a national emergency.[226] Later that year, Obama signed the Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act into law.[228] In 2016, the Democratic National Committee and other US organizations were hacked,[229] and the FBI and CIA concluded that Russia sponsored the hacking in hopes of helping Donald Trump win the 2016 presidential election.[230] The email accounts of other prominent individuals, including former secretary of state Colin Powell and CIA director John O. Brennan, were also hacked, leading to new fears about the confidentiality of emails.[231]

Racial issues

[edit]

In his speeches as president, Obama did not make more overt references to race relations than his predecessors,[232][233] but according to one study, he implemented stronger policy action on behalf of African-Americans than any president since the Nixon era.[234]

Following Obama's election, many pondered the existence of a "postracial America".[235][236] However, lingering racial tensions quickly became apparent,[235][237] and many African-Americans expressed outrage over what they saw as "racial venom" directed at Obama's presidency.[238] In July 2009, prominent African-American Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr., was arrested at his Cambridge, Massachusetts home by a local police officer, sparking a controversy after Obama stated that the police acted "stupidly" in handling the incident. To reduce tensions, Obama invited Gates and the police officer to the White House in what became known as the "Beer Summit".[239] Several other incidents during Obama's presidency sparked outrage in the African-American community or the law enforcement community, and Obama sought to build trust between law enforcement officials and civil rights activists.[240] The acquittal of George Zimmerman following the killing of Trayvon Martin sparked national outrage, leading to Obama giving a speech in which he noted that "Trayvon Martin could have been me 35 years ago."[241] The shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri sparked a wave of protests.[242] These and other events led to the birth of the Black Lives Matter movement, which campaigns against violence and systemic racism toward black people.[242] Some in the law enforcement community criticized Obama's condemnation of racial bias after incidents in which police action led to the death of African-American men, while some racial justice activists criticized Obama's expressions of empathy for the police.[240] Though Obama entered office reluctant to talk about race, by 2014 he began openly discussing the disadvantages faced by many members of minority groups.[243] In a March 2016 Gallup poll, nearly one third of Americans said they worried "a great deal" about race relations, a higher figure than in any previous Gallup poll since 2001.[244]

NASA space policy

[edit]

In July 2009, Obama appointed Charles Bolden, a former astronaut, as NASA Administrator.[245] That same year, Obama set up the Augustine panel to review the Constellation program. In February 2010, Obama announced that he was cutting the program from the 2011 United States federal budget, describing it as "over budget, behind schedule, and lacking in innovation."[246][247] After the decision drew criticism in the United States, a new "Flexible path to Mars" plan was unveiled at a space conference in April 2010.[248][249] It included new technology programs, increased R&D spending, an increase in NASA's 2011 budget from $18.3 billion to $19 billion, a focus on the International Space Station, and plans to contract future transportation to Low Earth orbit to private companies.[248] During Obama's presidency, NASA designed the Space Launch System and developed the Commercial Crew Development and Commercial Orbital Transportation Services to cooperate with private space flight companies.[250][251] These private companies, including SpaceX, Virgin Galactic, Blue Origin, Boeing, and Bigelow Aerospace, became increasingly active during Obama's presidency.[252] The Space Shuttle program ended in 2011, and NASA relied on the Russian space program to launch its astronauts into orbit for the remainder of the Obama administration.[250][253] Obama's presidency also saw the launch of the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and the Mars Science Laboratory. In 2016, Obama called on the United States to land a human on Mars by the 2030s.[252]

High tech initiatives

[edit]Obama promoted various technologies and the technological prowess of the United States. The number of American adults using the internet grew from 74% in 2008 to 84% in 2013,[254] and Obama pushed programs to extend broadband internet to lower income Americans.[255] Over the opposition of many Republicans, the Federal Communications Commission began regulating internet providers as public utilities, with the goal of protecting "net neutrality".[256] Obama launched 18F and the United States Digital Service, two organizations devoted to modernizing government information technology.[257][258] The stimulus package included money to build high-speed rail networks such as the proposed Florida High Speed Corridor, but political resistance and funding problems stymied those efforts.[259] In January 2016, Obama announced a plan to invest $4 billion in the development of self-driving cars, as well as an initiative by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration to develop regulations for self-driving cars.[260] That same month, Obama called for a national effort led by Vice President Biden to develop a cure for cancer.[261] On October 19, 2016, Biden spoke at the Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate at the University of Massachusetts Boston to speak about the administration's cancer initiative.[262] A 2020 study in the American Economic Review found that the decision by the Obama administration to issue press releases that named and shamed facilities that violated OSHA safety and health regulations led other facilities to increase their compliance and to experience fewer workplace injuries. The study estimated that each press release had the same effect on compliance as 210 inspections.[263][264]

Foreign affairs

[edit]

The Obama administration inherited a war in Afghanistan, a war in Iraq, and a global "War on Terror", all launched by Congress during the term of President Bush in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks. Upon taking office, Obama called for a "new beginning" in relations between the Muslim world and the United States,[266][267] and he discontinued the use of the term "War on Terror" in favor of the term "Overseas Contingency Operation".[268] Obama pursued a "light footprint" military strategy in the Middle East that emphasized special forces, drone strikes, and diplomacy over large ground troop occupations.[269] However, American forces continued to clash with Islamic militant organizations such as al-Qaeda, ISIL, and al-Shabaab[270] under the terms of the AUMF passed by Congress in 2001.[271] Though the Middle East remained important to American foreign policy, Obama pursued a "pivot" to East Asia.[272][273] Obama also emphasized closer relations with India, and was the first president to visit the country twice.[274] An advocate for nuclear non-proliferation, Obama successfully negotiated arms-reduction deals with Iran and Russia.[275] In 2015, Obama described the Obama Doctrine, saying "we will engage, but we preserve all our capabilities."[276] Obama also described himself as an internationalist who rejected isolationism and was influenced by realism and liberal interventionism.[277]

Iraq and Afghanistan

[edit]| Year | Iraq | Afghanistan |

|---|---|---|

| 2007* | 137,000[279] | 26,000[279] |

| 2008* | 154,000[279] | 27,500[279] |

| 2009 | 139,500[279] | 34,400[279] |

| 2010 | 107,100[279] | 71,700[279] |

| 2011 | 47,000[279] | 97,000[279] |

| 2012 | 150[280] | 91,000[281] |

| 2013 | ≈150 | 66,000[282] |

| 2014 | ≈150 | 38,000[283] |

| 2015 | 2,100[284] | 12,000[285] |

| 2016 | 4,450[286] | 9,800[287] |

| 2017 | 5,300[288] | 8,400[289] |

During the 2008 presidential election, Obama strongly criticized the Iraq War,[290] and Obama withdrew the vast majority of US soldiers in Iraq by late 2011. On taking office, Obama announced that US combat forces would leave Iraq by August 2010, with 35,000–50,000 American soldiers remaining in Iraq as advisers and trainers,[291] down from the roughly 150,000 American soldiers in Iraq in early 2009.[292] In 2008, President Bush had signed the US–Iraq Status of Forces Agreement, in which the United States committed to withdrawing all forces by late 2011.[293][294] Obama attempted to convince Iraqi prime minister Nouri al-Maliki to allow US soldiers to stay past 2011, but the large presence of American soldiers was unpopular with most Iraqis.[293] By late-December 2011, only 150 American soldiers remained to serve at the US embassy.[280] However, in 2014, the US began a campaign against ISIL, an Islamic extremist terrorist group operating in Iraq and Syria that grew dramatically after the withdrawal of US soldiers from Iraq and the start of the Syrian civil war.[295][296] By June 2015, there were about 3500 American soldiers in Iraq serving as advisers to anti-ISIL forces in the Iraqi civil war,[297] and Obama left office with roughly 5,262 US soldiers in Iraq and 503 of them in Syria.[298]

It is unacceptable that almost seven years after nearly 3,000 Americans were killed on our soil, the terrorists who attacked us on 9/11 are still at large. Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahari are recording messages to their followers and plotting more terror. The Taliban controls parts of Afghanistan. Al Qaeda has an expanding base in Pakistan that is probably no farther from their old Afghan sanctuary than a train ride from Washington to Philadelphia. If another attack on our homeland comes, it will likely come from the same region where 9/11 was planned. And yet today, we have five times more troops in Iraq than Afghanistan.[299]

— Obama during his 2008 presidential campaign speech

Obama increased the number of American soldiers in Afghanistan during his first term before withdrawing most military personnel in his second term. On taking office, Obama announced that the US military presence in Afghanistan would be bolstered by 17,000 new troops by Summer 2009,[300] on top of the roughly 30,000 soldiers already in Afghanistan at the start of 2009.[301] Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and Joint Chiefs of Staff Chair Michael Mullen all argued for further troops, and Obama dispatched additional soldiers after a lengthy review process.[302][303] During this time, his administration had used the neologism AfPak to denote Afghanistan and Pakistan as a single theater of operations in the war on terror.[304] The number of American soldiers in Afghanistan would peak at 100,000 in 2010.[279] In 2012, the US and Afghanistan signed a strategic partnership agreement in which the US agreed to hand over major combat operation to Afghan forces.[305] That same year, the Obama administration designated Afghanistan as a major non-NATO ally.[306] In 2014, Obama announced that most troops would leave Afghanistan by late 2016, with a small force remaining at the US embassy.[307] In September 2014, Ashraf Ghani succeeded Hamid Karzai as the President of Afghanistan after the US helped negotiate a power-sharing agreement between Ghani and Abdullah Abdullah.[308] On January 1, 2015, the US military ended Operation Enduring Freedom and began Resolute Support Mission, in which the US shifted to more of a training role, although some combat operations continued.[309] In October 2015, Obama announced that US soldiers would remain in Afghanistan indefinitely in order support the Afghan government in the civil war against the Taliban, al-Qaeda, and ISIL.[310] Joint Chiefs of Staff Chair Martin Dempsey framed the decision to keep soldiers in Afghanistan as part of a long-term counter-terrorism operation stretching across Central Asia.[311] Obama left office with roughly 8,400 US soldiers remaining in Afghanistan.[289]

East Asia

[edit]Though other areas of the world remained important to American foreign policy, Obama pursued a "pivot" to East Asia, focusing the US's diplomacy and trade in the region.[272][273] China's continued emergence as a major power was a major issue of Obama's presidency; while the two countries worked together on issues such as climate change, the China-United States relationship also experienced tensions regarding territorial claims in the South China Sea and the East China Sea.[312] In 2016, the United States hosted a summit with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) for the first time, reflecting the Obama administration's pursuit of closer relations with ASEAN and other Asian countries.[313] After helping to encourage openly contested elections in Myanmar, Obama lifted many US sanctions on Myanmar.[314][315] Obama also increased US military ties with Vietnam,[316] Australia, and the Philippines, increased aid to Laos, and contributed to a warming of relations between South Korea and Japan.[317] Obama designed the Trans-Pacific Partnership as the key economic pillar of the Asian pivot, though the agreement remains unratified.[317] Obama made little progress with relations with North Korea, a long-time adversary of the United States, and North Korea continued to develop its WMD program.[318]

Russia

[edit]

On taking office, Obama called for a "reset" in relations with Russia, which had declined following the 2008 Russo-Georgian War.[319] While President Bush had successfully pushed for NATO expansion into former Eastern bloc states, the early Obama era saw NATO put more of an emphasis on creating a long-term partnership with Russia.[320] Obama and Russian President Dmitry Medvedev worked together on a new treaty to reduce and monitor nuclear weapons, Russian accession to the World Trade Organization, and counterterrorism.[319] On April 8, 2010, Obama and Medvedev signed the New START treaty, a major nuclear arms control agreement that reduced the nuclear weapons stockpiles of both countries and provided for a monitoring regime.[321] In December 2010, the Senate ratified New START in a 71–26 vote, with 13 Republicans and all Democrats voting in favor of the treaty.[322] In 2012, Russia joined the World Trade Organization and Obama normalized trade relations with Russia.[323]

US–Russia relations declined after Vladimir Putin returned to the presidency in 2012.[319] Russia's invasion of Ukraine and annexation of Crimea in response to the Euromaidan movement led to a strong condemnation by Obama and other Western leaders, who imposed sanctions on Russian leaders.[319][324] The sanctions contributed to the Russian financial crisis (2014–2016).[325] Some members of Congress from both parties also called for the US to arm Ukrainian forces, but Obama resisted becoming closely involved in the War in Donbas.[326] In 2016, following several cybersecurity incidents, the Obama administration formally accused Russia of engaging in a campaign to undermine the 2016 election, and the administration imposed sanctions on some Russian-linked people and organizations.[327][328] In 2017, after Obama left office, Robert Mueller was appointed as special counsel to investigate Russian's involvement in the 2016 election, including allegations of conspiracy or coordination between Trump's presidential campaign and Russia.[329] The Mueller Report, released in 2019, concludes that Russia undertook a sustained social media campaign and cyberhacking operation to bolster the Trump campaign.[330] The report did not reach a conclusion on allegations that the Trump campaign had colluded with Russia, but, according to Mueller, his investigation did not find evidence "sufficient to charge any member of the [Trump] campaign with taking part in a criminal conspiracy."[331]

Israel

[edit]The relationship between Obama and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu (who held office for all but two months of Obama's presidency) was notably icy, with many commenting on their mutual distaste for each other.[332][333] On taking office, Obama appointed George J. Mitchell as a special envoy to the Middle East to work towards a settlement of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, but Mitchell made little progress before stepping down in 2011.[334] In March 2010, Secretary of State Clinton criticized the Israeli government for approving expansion of settlements in East Jerusalem.[335] Netanyahu strongly opposed Obama's efforts to negotiate with Iran and was seen as favoring Mitt Romney in the 2012 US presidential election.[332] However, Obama continued the US policy of vetoing UN resolutions calling for a Palestinian state, and the administration continued to advocate for a negotiated two-state solution.[336] Obama also increased aid to Israel, including a $225 million emergency aid package for the Iron Dome air defense program.[337]

During Obama's last months in office, his administration chose not to veto United Nations Security Council Resolution 2334, which urged the end of Israeli settlement in the territories that Israel captured in the Six-Day War of 1967. The Obama administration argued that the abstention was consistent with long-standing American opposition to the expansion of settlements, while critics of the abstention argued that it abandoned a close US ally.[338]

Trade agreements

[edit]

Like his predecessor, Obama pursued free trade agreements, in part due to the lack of progress at the Doha negotiations in lowering trade barriers worldwide.[339] In October 2011, the United States entered into free trade agreements with Colombia, Panama, and South Korea. Congressional Republicans overwhelmingly supported the agreements, while Congressional Democrats cast a mix of votes.[340] The three agreements had originally been negotiated by the Bush administration, but Obama re-opened negotiations with each country and changed some terms of each deal.[340]

Obama promoted two significantly larger, multilateral free trade agreements: the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) with eleven Pacific Rim countries, including Japan, Mexico, and Canada, and the proposed Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) with the European Union.[341] TPP negotiations began under President Bush, and Obama continued them as part of a long-term strategy that sought to refocus on rapidly growing economies in East Asia.[342] The chief administration goals in the TPP, included: (1) establishing free market capitalism as the main normative platform for economic integration in the region; (2) guaranteeing standards for intellectual property rights, especially regarding copyright, software, and technology; (3) underscore American leadership in shaping the rules and norms of the emerging global order; (4) and blocking China from establishing a rival network.[343]

After years of negotiations, the 12 countries reached a final agreement on the content of the TPP in October 2015,[344] and the full text of the treaty was made public in November 2015.[345] The Obama administration was criticized from the left for a lack of transparency in the negotiations, as well as the presence of corporate representatives who assisted in the drafting process.[346][347][348] In July 2015, Congress passed a bill giving trade promotion authority to the president until 2021; trade promotion authority requires Congress to vote up or down on trade agreements signed by the president, with no possibility of amendments or filibusters.[349] The TPP became a major campaign issue in the 2016 elections, with both major party presidential nominees opposing its ratification.[350] After Obama left office, President Trump pulled the United States out of the TPP negotiations, and the remaining TPP signatories later concluded a separate free trade agreement known as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.[351]

In June 2011, it was reported that the US Embassy aided Levi's, Hanes contractors in their fight against an increase in Haiti's minimum wage.[352]

Guantanamo Bay detention camp

[edit]In 2002, the Bush administration established the Guantanamo Bay detention camp to hold alleged "enemy combatants" in a manner that did not treat the detainees as conventional prisoners of war.[353] Obama repeatedly stated his desire to close the detention camp, arguing that the camp's extrajudicial nature provided a recruitment tool for terrorist organizations.[353] On his first day in office, Obama instructed all military prosecutors to suspend proceedings so that the incoming administration could review the military commission process.[354] On January 22, 2009, Obama signed an executive order restricting interrogators to methods listed and authorized by an Army Field Manual,[355] ending the use of "enhanced interrogation techniques".[356] In March 2009, the administration announced that it would no longer refer to prisoners at Guantanamo Bay as enemy combatants, but it also asserted that the president had the authority to detain terrorism suspects there without criminal charges.[357] The prisoner population of the detention camp fell from 242 in January 2009 to 91 in January 2016, in part due to the Periodic Review Boards that Obama established in 2011.[358] Many members of Congress strongly opposed plans to transfer Guantanamo detainees to prisons in US states, and the Obama administration was reluctant to send potentially dangerous prisoners to other countries, especially unstable countries such as Yemen.[359] Though Obama continued to advocate for the closure of the detention camp,[359] 41 inmates remained in Guantanamo when Obama left office.[360][361]

Killing of Osama bin Laden

[edit]

The Obama administration launched a successful operation that resulted in the death of Osama bin Laden, the leader of al-Qaeda, a global Sunni Islamist militant organization responsible for the September 11 attacks and several other terrorist attacks.[362] Starting with information received in July 2010, the CIA located Osama bin Laden in a large compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, a suburban area 35 miles (56 km) from Islamabad.[363] CIA head Leon Panetta reported this intelligence to Obama in March 2011. Meeting with his national security advisers over the course of the next six weeks, Obama rejected a plan to bomb the compound, and authorized a "surgical raid" to be conducted by United States Navy SEALs. The operation took place on May 1, 2011, resulting in the death of bin Laden and the seizure of papers and computer drives and disks from the compound.[364] Bin Laden's body was identified through DNA testing, and buried at sea several hours later.[365] Reaction to the announcement was positive across party lines, including from his two predecessors George W. Bush and Bill Clinton,[366] and from many countries around the world.[367]

Drone warfare

[edit]Obama expanded the drone strike program begun by the Bush administration, and the Obama administration conducted drone strikes against targets in Yemen, Somalia, and, most prominently, Pakistan.[368] Though the drone strikes killed high-ranking terrorists, they were also criticized for resulting in civilian casualties.[369] A 2013 Pew research poll showed that the strikes were broadly unpopular in Pakistan,[370] and some former members of the Obama administration have criticized the strikes for causing a backlash against the United States.[369] However, based on 147 interviews conducted in 2015, professor Aqil Shah argued that the strikes were popular in North Waziristan, the area in which most of the strikes take place, and that little blowback occurred.[371] In 2009, the UN special investigator on extrajudicial, summary, or arbitrary executions called the United States' reliance on drones "increasingly common" and "deeply troubling", and called on the US to justify its use of targeted assassinations rather than attempting to capture al Qaeda or Taliban suspects.[372][373]

Starting in 2011, in response to Obama's attempts to avoid civilian casualties, the Hellfire R9X "flying Ginsu" missile was developed. It is usually fired from drones. It does not have an explosive warhead that causes a large area of destruction but kills by using six rotating blades that cut the target into shreds. On July 31, 2022, Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri was killed by an R9X missile.[374] In 2013, Obama appointed John Brennan as the new CIA Director and announced a new policy that required CIA operatives to determine with a "near-certainty" that no civilians would be hurt in a drone strike.[368] The number of drone strikes fell substantially after the announcement of the new policy.[368][369]

As of 2015, US drone strikes had killed eight American citizens, one of whom, Anwar al-Aulaqi, was targeted.[369] The targeted killing of a United States citizen raised Constitutional issues, as it is the first known instance of a sitting US president ordering the extrajudicial killing of a US citizen.[375][376] Obama had ordered the targeted killing of al-Aulaqi, a Muslim cleric with ties to al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, after al-Aulaqi allegedly shifted from encouraging attacks on the United States to directly participating in them.[377][378] The Obama administration continually sought to keep classified the legal opinions justifying drone strikes, but it said that it conducted special legal reviews before targeting Americans in order to purportedly satisfy the due process requirements of the Constitution.[369][379]

Cuban thaw

[edit]

The Obama presidency saw a major thaw in relations with Cuba, which the United States embargoed following the Cuban Revolution and the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. Starting in the spring of 2013 secret meetings were conducted between the United States and Cuba, with the meetings taking place in the neutral locations of Canada and Vatican City.[380] The Vatican was consulted initially in 2013 as Pope Francis advised the US and Cuba to exchange prisoners as a gesture of goodwill.[381] On December 10, 2013, Cuban President Raúl Castro, in a significant public moment, shook hands with and greeted Obama at Nelson Mandela's memorial service in Johannesburg.[citation needed] In December 2014, Cuba released Alan Gross in exchange for the remaining members of the Cuban Five.[381] That same month, President Obama ordered the restoration of diplomatic ties with Cuba.[382] Obama stated that he was normalizing relationships because the economic embargo had been ineffective in persuading Cuba to develop a democratic society.[383] In May 2015, Cuba was taken off the United States's list of State Sponsors of Terrorism.[384] In August 2015, following the restoration of official diplomatic relations, the United States and Cuba reopened their respective embassies.[385] In March 2016, Obama visited Cuba, making him the first American president to set foot on the island since Calvin Coolidge.[386] In 2017, Obama ended the "wet feet, dry feet policy", which had given special rights to Cuban immigrants to the United States.[387] The restored ties between Cuba and the US were seen as a boon to broader Latin America–United States relations, as Latin American leaders unanimously approved of the move.[388][389] Presidential candidate Donald Trump promised to reverse the Obama policies and return to a hard line on Cuba.[390]

Iran