Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Syriac alphabet

View on Wikipedia| Syriac alphabet | |

|---|---|

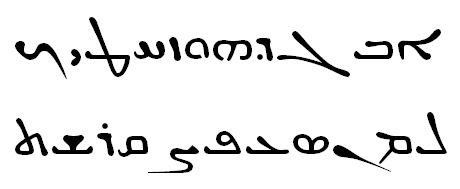

Estrangela-styled alphabet | |

| Script type | Impure abjad

|

Period | c. 1st century AD – present |

| Direction | Right-to-left script |

| Languages | Aramaic (Classical Syriac, Western Neo-Aramaic, Sureth, Turoyo, Christian Palestinian Aramaic), Arabic (Garshuni), Malayalam (Karshoni), Sogdian |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Egyptian

|

Child systems | |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Syrc (135), Syriac

|

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Syriac |

| |

The Syriac alphabet (ܐܠܦ ܒܝܬ ܣܘܪܝܝܐ ʾālep̄ bêṯ Sūryāyā[a]) is a writing system primarily used to write the Syriac language since the 1st century.[1] It is one of the Semitic abjads descending from the Aramaic alphabet through the Palmyrene alphabet,[2] and shares similarities with the Phoenician, Hebrew, Arabic and Sogdian, the precursor and a direct ancestor of the traditional Mongolian scripts.

Syriac is written from right to left in horizontal lines. It is a cursive script where most—but not all—letters connect within a word. There is no letter case distinction between upper and lower case letters, though some letters change their form depending on their position within a word. Spaces separate individual words.

All 22 letters are consonants (called ܐܵܬܘܼܬܵܐ, ˀātūṯā). There are optional diacritic marks (called ܢܘܼܩܙܵܐ, nuqzā) to indicate the vowel (ܙܵܘܥܵܐ, zāwˁā) and other features. In addition to the sounds of the language, the letters of the Syriac alphabet can be used to represent numbers in a system similar to Hebrew and Greek numerals.

Apart from Classical Syriac Aramaic, the alphabet has been used to write other dialects and languages. Several Christian Neo-Aramaic languages, from Turoyo to the Northeastern Neo-Aramaic language of Suret, once vernaculars, primarily began to be written in the 19th century. The Serṭā variant has explicitly been adapted to write Western Neo-Aramaic, previously written in the square Maalouli script, developed by George Rizkalla (Rezkallah), based on the Hebrew alphabet.[3][4] Besides Aramaic, when Arabic began to be the dominant spoken language in the Fertile Crescent after the Islamic conquest, texts were often written in Arabic using the Syriac script as knowledge of the Arabic alphabet was not yet widespread; such writings are usually called Karshuni or Garshuni (ܓܪܫܘܢܝ). In addition to Semitic languages, Sogdian was also written with Syriac script, as well as Malayalam, which form was called Suriyani Malayalam.

Alphabet forms

[edit]

There are three major variants of the Syriac alphabet: ʾEsṭrangēlā, Maḏnḥāyā and Serṭā.

Classical ʾEsṭrangēlā

[edit]

The oldest and classical form of the alphabet is ʾEsṭrangēlā[b] (ܐܣܛܪܢܓܠܐ). The name of the script is thought to derive from the Greek adjective strongýlē (στρογγύλη, 'rounded'),[5] though it has also been suggested to derive from serṭā ʾewwangēlāyā (ܣܪܛܐ ܐܘܢܓܠܝܐ, 'gospel character').[6] Although ʾEsṭrangēlā is no longer used as the main script for writing Syriac, it has received some revival since the 10th century. It is often used in scholarly publications (such as the Leiden University version of the Peshitta), in titles, and in inscriptions. In some older manuscripts and inscriptions, it is possible for any letter to join to the left, and older Aramaic letter forms (especially of ḥeṯ and the lunate mem) are found. Vowel marks are usually not used with ʾEsṭrangēlā, because it is the oldest form of the script and arose before specialized diacritics were developed.

East Syriac Maḏnḥāyā

[edit]The East Syriac dialect is usually written in the Maḏnḥāyā (ܡܲܕ݂ܢܚܵܝܵܐ, 'Eastern') form of the alphabet. Other names for the script include Swāḏāyā (ܣܘܵܕ݂ܵܝܵܐ, 'conversational' or 'vernacular', often translated as 'contemporary', reflecting its use in writing modern Neo-Aramaic), ʾĀṯōrāyā (ܐܵܬ݂ܘܿܪܵܝܵܐ, 'Assyrian', not to be confused with the traditional name for the Hebrew alphabet), Kaldāyā (ܟܲܠܕܵܝܵܐ, 'Chaldean'), and, inaccurately, "Nestorian" (a term that was originally used to refer to the Church of the East in the Sasanian Empire). The Eastern script resembles ʾEsṭrangēlā somewhat more closely than the Western script.

Vowels

[edit]The Eastern script uses a system of dots above and/or below letters, based on an older system, to indicate vowel sounds not found in the script:

- (

) A dot above and a dot below a letter represent [a], transliterated as a or ă (called ܦܬ݂ܵܚܵܐ, pṯāḥā),

) A dot above and a dot below a letter represent [a], transliterated as a or ă (called ܦܬ݂ܵܚܵܐ, pṯāḥā), - (

) Two diagonally-placed dots above a letter represent [ɑ], transliterated as ā or â or å (called ܙܩܵܦ݂ܵܐ, zqāp̄ā),

) Two diagonally-placed dots above a letter represent [ɑ], transliterated as ā or â or å (called ܙܩܵܦ݂ܵܐ, zqāp̄ā), - (

) Two horizontally-placed dots below a letter represent [ɛ], transliterated as e or ĕ (called ܪܒ݂ܵܨܵܐ ܐܲܪܝܼܟ݂ܵܐ, rḇāṣā ʾărīḵā or ܙܠܵܡܵܐ ܦܫܝܼܩܵܐ, zlāmā pšīqā; often pronounced [ɪ] and transliterated as i in the East Syriac dialect),

) Two horizontally-placed dots below a letter represent [ɛ], transliterated as e or ĕ (called ܪܒ݂ܵܨܵܐ ܐܲܪܝܼܟ݂ܵܐ, rḇāṣā ʾărīḵā or ܙܠܵܡܵܐ ܦܫܝܼܩܵܐ, zlāmā pšīqā; often pronounced [ɪ] and transliterated as i in the East Syriac dialect), - (

) Two diagonally-placed dots below a letter represent [e], transliterated as ē (called ܪܒ݂ܵܨܵܐ ܟܲܪܝܵܐ, rḇāṣā karyā or ܙܠܵܡܵܐ ܩܲܫܝܵܐ, zlāmā qašyā),

) Two diagonally-placed dots below a letter represent [e], transliterated as ē (called ܪܒ݂ܵܨܵܐ ܟܲܪܝܵܐ, rḇāṣā karyā or ܙܠܵܡܵܐ ܩܲܫܝܵܐ, zlāmā qašyā), - (ܘܼ) The letter waw with a dot below it represents [u], transliterated as ū or u (called ܥܨܵܨܵܐ ܐܲܠܝܼܨܵܐ, ʿṣāṣā ʾălīṣā or ܪܒ݂ܵܨܵܐ, rḇāṣā),

- (ܘܿ) The letter waw with a dot above it represents [o], transliterated as ō or o (called ܥܨܵܨܵܐ ܪܘܝܼܚܵܐ, ʿṣāṣā rwīḥā or ܪܘܵܚܵܐ, rwāḥā),

- (ܝܼ) The letter yōḏ with a dot beneath it represents [i], transliterated as ī or i (called ܚܒ݂ܵܨܵܐ, ḥḇāṣā),

- (

) A combination of rḇāṣā karyā (usually) followed by a letter yōḏ represents [e] (possibly *[e̝] in Proto-Syriac), transliterated as ē or ê (called ܐܲܣܵܩܵܐ, ʾăsāqā).

) A combination of rḇāṣā karyā (usually) followed by a letter yōḏ represents [e] (possibly *[e̝] in Proto-Syriac), transliterated as ē or ê (called ܐܲܣܵܩܵܐ, ʾăsāqā).

It is thought that the Eastern method for representing vowels influenced the development of the niqqud markings used for writing Hebrew.

In addition to the above vowel marks, transliteration of Syriac sometimes includes ə, e̊ or superscript e (or often nothing at all) to represent an original Aramaic schwa that became lost later on at some point in the development of Syriac. Some transliteration schemes find its inclusion necessary for showing spirantization or for historical reasons. Whether because its distribution is mostly predictable (usually inside a syllable-initial two-consonant cluster) or because its pronunciation was lost, both the East and the West variants of the alphabet traditionally have no sign to represent the schwa.

West Syriac Serṭā

[edit]

The West Syriac dialect is usually written in the Serṭā or Serṭo (ܣܶܪܛܳܐ, 'line') form of the alphabet, also known as the Pšīṭā (ܦܫܺܝܛܳܐ, 'simple'), 'Maronite' or the 'Jacobite' script (although the term Jacobite is considered derogatory). Most of the letters are clearly derived from ʾEsṭrangēlā, but are simplified, flowing lines. A cursive chancery hand is evidenced in the earliest Syriac manuscripts, but important works were written in ʾEsṭrangēlā. From the 8th century, the simpler Serṭā style came into fashion, perhaps because of its more economical use of parchment.

Vowels

[edit]The Western script is usually vowel-pointed, with miniature Greek vowel letters above or below the letter which they follow:

- (

) Capital alpha (Α) represents [a], transliterated as a or ă (ܦܬ݂ܳܚܳܐ, pṯāḥā),

) Capital alpha (Α) represents [a], transliterated as a or ă (ܦܬ݂ܳܚܳܐ, pṯāḥā), - (

) Lowercase alpha (α) represents [ɑ], transliterated as ā or â or å (ܙܩܳܦ݂ܳܐ, zqāp̄ā; pronounced as [o] and transliterated as o in the West Syriac dialect),

) Lowercase alpha (α) represents [ɑ], transliterated as ā or â or å (ܙܩܳܦ݂ܳܐ, zqāp̄ā; pronounced as [o] and transliterated as o in the West Syriac dialect), - (

) Lowercase epsilon (ε) represents both [ɛ], transliterated as e or ĕ, and [e], transliterated as ē (ܪܒ݂ܳܨܳܐ, rḇāṣā),

) Lowercase epsilon (ε) represents both [ɛ], transliterated as e or ĕ, and [e], transliterated as ē (ܪܒ݂ܳܨܳܐ, rḇāṣā), - (

) Capital eta (Η) represents [i], transliterated as ī (ܚܒ݂ܳܨܳܐ, ḥḇāṣā),

) Capital eta (Η) represents [i], transliterated as ī (ܚܒ݂ܳܨܳܐ, ḥḇāṣā), - (

) A combined symbol of capital upsilon (Υ) and lowercase omicron (ο) represents [u], transliterated as ū or u (ܥܨܳܨܳܐ, ʿṣāṣā),

) A combined symbol of capital upsilon (Υ) and lowercase omicron (ο) represents [u], transliterated as ū or u (ܥܨܳܨܳܐ, ʿṣāṣā), - Lowercase omega (ω), used only in the vocative interjection ʾō (ܐܘّ, 'O!').

Summary table

[edit]The Syriac alphabet consists of the following letters, shown in their isolated (non-connected) forms. When isolated, the letters kāp̄, mīm, and nūn are usually shown with their initial form connected to their final form (see below). The letters ʾālep̄, dālaṯ, hē, waw, zayn, ṣāḏē, rēš and taw (and, in early ʾEsṭrangēlā manuscripts, the letter semkaṯ[7]) do not connect to a following letter within a word; these are marked with an asterisk (*).

| Letter | Sound Value (Classical Syriac) |

Numerical Value |

Phoenician Equivalent |

Imperial Aramaic Equivalent |

Hebrew Equivalent |

Arabic

Equivalent | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Translit. | ʾEsṭrangēlā (classical) |

Maḏnḥāyā (eastern) |

Serṭā (western) |

Latin

(1930) |

Cyrillic

(pre-1929, 1938) |

Unicode (typing) |

Transliteration | IPA | |||||

| *ܐܠܦ | ʾĀlep̄*[c] | a, ə | ə, a | ܐ | ʾ or null mater lectionis: ā |

[ʔ] or ∅ mater lectionis: [ɑ] |

1 | 𐤀 | 𐡀 | א | ا | |||

| ܒܝܬ | Bēṯ | b, v | б, в | ܒ | hard: b soft: ḇ (also bh, v or ꞵ) |

hard: [b] soft: [v] or [w] |

2 | 𐤁 | 𐡁 | ב | ب | |||

| ܓܡܠ | Gāmal | g, x/h, ç | г, h, dж | ܓ | hard: g soft: ḡ (also g̱, gh, ġ or γ) |

hard: [ɡ] soft: [ɣ] |

3 | 𐤂 | 𐡂 | ג | ج | |||

| *ܕܠܬ | Dālaṯ* | d | d | ܕ | hard: d soft: ḏ (also dh, ð or ẟ) |

hard: [d] soft: [ð] |

4 | 𐤃 | 𐡃 | ד | د / ذ | |||

| *ܗܐ | Hē* | h | h | ܗ | h mater lectionis: ē (or e) |

[h] mater lectionis: [e] |

5 | 𐤄 | 𐡄 | ה | ه | |||

| *ܘܘ | Waw* | v, o, u | в, o, у | ܘ | consonant: w mater lectionis: ū or ō (also u or o) |

consonant: [w] mater lectionis: [u] or [o] |

6 | 𐤅 | 𐡅 | ו | و | |||

| *ܙܝܢ | Zayn* | z | з | ܙ | z | [z] | 7 | 𐤆 | 𐡆 | ז | ز | |||

| ܚܝܬ | Ḥēṯ | x | x | ܚ | ḥ (also H, kh, x or ħ) | [ħ], [x] or [χ] | 8 | 𐤇 | 𐡇 | ח | ح / خ | |||

| ܛܝܬ | Ṭēṯ | ţ | t | ܛ | ṭ (also T or ţ) | [tˤ] | 9 | 𐤈 | 𐡈 | ט | ظ / ط | |||

| ܝܘܕ | Yōḏ | j, ij/ьj | j, иj/ыj | ܝ | consonant: y mater lectionis: ī (also i) |

consonant: [j] mater lectionis: [i] or [ɪ] |

10 | 𐤉 | 𐡉 | י | ي | |||

| ܟܦ | Kāp̄ | k, x, c | q, x, ч | ܟܟ | hard: k soft: ḵ (also kh or x) |

hard: [k] soft: [x] |

20 | 𐤊 | 𐡊 | כ ך | ك | |||

| ܠܡܕ | Lāmaḏ | l | l | ܠ | l | [l] | 30 | 𐤋 | 𐡋 | ל | ل | |||

| ܡܝܡ | Mīm | m | м | ܡܡ | m | [m] | 40 | 𐤌 | 𐡌 | מ ם | م | |||

| ܢܘܢ | Nūn | n | н | ܢܢ | n | [n] | 50 | 𐤍 | 𐡍 | נ ן | ن | |||

| ܣܡܟܬ | Semkaṯ | s | c | ܣ | s | [s] | 60 | 𐤎 | 𐡎 | ס | س | |||

| ܥܐ | ʿĒ | a | ə | ܥ | ʿ | [ʕ][d] | 70 | 𐤏 | 𐡏 | ע | ع / غ | |||

| ܦܐ | Pē | p, f | п, ф | ܦ | hard: p soft: p̄ (also p̱, ᵽ, ph or f) |

hard: [p] soft: [f] |

80 | 𐤐 | 𐡐 | פ ף | ف | |||

| *ܨܕܐ | Ṣāḏē* | s | c | ܨ | ṣ (also S or ş) | [sˤ] | 90 | 𐤑 | 𐡑 | צ ץ | ض / ص | |||

| ܩܘܦ | Qōp̄ | q | к | ܩ | q (also ḳ) | [q] | 100 | 𐤒 | 𐡒 | ק | ق | |||

| *ܪܝܫ | Rēš* | r | p | ܪ | r | [r] | 200 | 𐤓 | 𐡓 | ר | ر | |||

| ܫܝܢ | Šīn | ş, ƶ | ш, ж | ܫ | š (also sh) | [ʃ] | 300 | 𐤔 | 𐡔 | ש | ش | |||

| *ܬܘ | Taw* | t | т | ܬ | hard: t soft: ṯ (also th or θ) |

hard: [t] soft: [θ] |

400 | 𐤕 | 𐡕 | ת | ت / ث | |||

Contextual forms of letters

[edit]| Letter

name |

ʾEsṭrangēlā (classical) | Maḏnḥāyā (eastern) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconnected

final |

Connected

final |

Initial or

unconnected medial |

Unconnected

final |

Connected

final |

Initial or

unconnected medial | |

| ʾĀlep̄ | ||||||

| Bēṯ | ||||||

| Gāmal | ||||||

| Dālaṯ | ||||||

| Hē | ||||||

| Waw | ||||||

| Zayn | ||||||

| Ḥēṯ | ||||||

| Ṭēṯ | ||||||

| Yōḏ | ||||||

| Kāp̄ | ||||||

| Lāmaḏ | ||||||

| Mīm | ||||||

| Nūn | ||||||

| Semkaṯ | ||||||

| ʿĒ | ||||||

| Pē | ||||||

| Ṣāḏē | ||||||

| Qōp̄ | ||||||

| Rēš | ||||||

| Šīn | ||||||

| Taw | ||||||

Ligatures

[edit]Letter alterations

[edit]Matres lectionis

[edit]

Three letters act as matres lectionis: rather than being a consonant, they indicate a vowel. ʾālep̄ (ܐ), the first letter, represents a glottal stop, but it can also indicate a vowel, especially at the beginning or the end of a word. The letter waw (ܘ) is the consonant w, but can also represent the vowels o and u. Likewise, the letter yōḏ (ܝ) represents the consonant y, but it also stands for the vowels i and e.

Majlīyānā

[edit]In modern usage, some alterations can be made to represent phonemes not represented in classical phonology. A mark similar in appearance to a tilde (~), called majlīyānā (ܡܲܓ̰ܠܝܼܵܢܵܐ), is placed above or below a letter in the Maḏnḥāyā variant of the alphabet to change its phonetic value (see also: Geresh):

- Added below gāmal: [ɡ] to [d͡ʒ] (voiced palato-alveolar affricate)

- Added below kāp̄: [k] to [t͡ʃ] (voiceless palato-alveolar affricate)

- Added above or below zayn: [z] to [ʒ] (voiced palato-alveolar sibilant)

- Added above šīn: [ʃ] to [ʒ]

Rūkkāḵā and qūššāyā

[edit]In addition to foreign sounds, a marking system is used to distinguish qūššāyā (ܩܘܫܝܐ, 'hard' letters) from rūkkāḵā (ܪܘܟܟܐ, 'soft' letters). The letters bēṯ, gāmal, dālaṯ, kāp̄, pē, and taw, all stop consonants ('hard') are able to be 'spirantized' (lenited) into fricative consonants ('soft'). The system involves placing a single dot underneath the letter to give its 'soft' variant and a dot above the letter to give its 'hard' variant (though, in modern usage, no mark at all is usually used to indicate the 'hard' value):

| Name | Stop | Translit. | IPA | Name | Fricative | Translit. | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bēṯ (qšīṯā) | ܒ݁ | b | [b] | Bēṯ rakkīḵtā | ܒ݂ | ḇ | [v] or [w] | [v] has become [w] in most modern dialects. |

| Gāmal (qšīṯā) | ܓ݁ | g | [ɡ] | Gāmal rakkīḵtā | ܓ݂ | ḡ | [ɣ] | Usually becomes [j], [ʔ], or is not pronounced in modern Eastern dialects. |

| Dālaṯ (qšīṯā) | ܕ݁ | d | [d] | Dālaṯ rakkīḵtā | ܕ݂ | ḏ | [ð] | [d] is left unspirantized in some modern Eastern dialects. |

| Kāp̄ (qšīṯā) | ܟ݁ | k | [k] | Kāp̄ rakkīḵtā | ܟ݂ | ḵ | [x] | |

| Pē (qšīṯā) | ܦ݁ | p | [p] | Pē rakkīḵtā | ܦ݂ or ܦ̮ | p̄ | [f] or [w] | [f] is not found in most modern Eastern dialects. Instead, it either is left unspirantized or sometimes appears as [w]. Pē is the only letter in the Eastern variant of the alphabet that is spirantized by the addition of a semicircle instead of a single dot. |

| Taw (qšīṯā) | ܬ݁ | t | [t] | Taw rakkīḵtā | ܬ݂ | ṯ | [θ] | [t] is left unspirantized in some modern Eastern dialects. |

The mnemonic bḡaḏkp̄āṯ (ܒܓܕܟܦܬ) is often used to remember the six letters that are able to be spirantized (see also: Begadkepat).

In the East Syriac variant of the alphabet, spirantization marks are usually omitted when they interfere with vowel marks. The degree to which letters can be spirantized varies from dialect to dialect as some dialects have lost the ability for certain letters to be spirantized. For native words, spirantization depends on the letter's position within a word or syllable, location relative to other consonants and vowels, gemination, etymology, and other factors. Foreign words do not always follow the rules for spirantization.

Syāmē

[edit]Syriac uses two (usually) horizontal dots[f] above a letter within a word, similar in appearance to diaeresis, called syāmē (ܣܝ̈ܡܐ, literally 'placings', also known in some grammars by the Hebrew name ribbuy [רִבּוּי], 'plural'), to indicate that the word is plural.[8] These dots, having no sound value in themselves, arose before both eastern and western vowel systems as it became necessary to mark plural forms of words, which are indistinguishable from their singular counterparts in regularly-inflected nouns. For instance, the word malkā (ܡܠܟܐ, 'king') is consonantally identical to its plural malkē (ܡܠܟ̈ܐ, 'kings'); the syāmē above the word malkē (ܡܠܟ̈ܐ) clarifies its grammatical number and pronunciation. Irregular plurals also receive syāmē even though their forms are clearly plural: e.g. baytā (ܒܝܬܐ, 'house') and its irregular plural bāttē (ܒ̈ܬܐ, 'houses'). Because of redundancy, some modern usage forgoes syāmē points when vowel markings are present.

There are no firm rules for which letter receives syāmē; the writer has full discretion to place them over any letter. Typically, if a word has at least one rēš, then syāmē are placed over the rēš that is nearest the end of a word (and also replace the single dot above it: ܪ̈). Other letters that often receive syāmē are low-rising letters—such as yōḏ and nūn—or letters that appear near the middle or end of a word.

Besides plural nouns, syāmē are also placed on:

- plural adjectives, including participles (except masculine plural adjectives/participles in the absolute state);

- the cardinal numbers 'two' and the feminine forms of 11–19, though inconsistently;

- and certain feminine plural verbs: the 3rd person feminine plural perfect and the 2nd and 3rd person feminine plural imperfect.

Mṭalqānā

[edit]Syriac uses a diacritic line, called mṭalqānā (ܡܛܠܩܢܐ, literally 'concealer', also known by the Latin term linea occultans in some grammars), to indicate a silent letter that can occur at the beginning or middle of a word.[9] In Eastern Syriac, this line is diagonal and only occurs above the silent letter (e.g. ܡܕ݂ܝܼܢ݇ܬܵܐ, 'city', pronounced mḏīttā, not *mḏīntā, with the mṭalqānā over the nūn, assimilating with the taw). The line can only occur above a letter ʾālep̄, hē, waw, yōḏ, lāmaḏ, mīm, nūn, ʿē or rēš (which comprise the mnemonic ܥܡ̈ܠܝ ܢܘܗܪܐ ʿamlay nūhrā, 'the works of light'). In Western Syriac, this line is horizontal and can be placed above or below the letter (e.g. ܡܕ݂ܺܝܢ̄ܬܳܐ, 'city', pronounced mḏīto, not *mḏīnto).

Classically, mṭalqānā was not used for silent letters that occurred at the end of a word (e.g. ܡܪܝ mār[ī], '[my] lord'). In modern Turoyo, however, this is not always the case (e.g. ܡܳܪܝ̱ mor[ī], '[my] lord').

Latin alphabet and romanization

[edit]In 1930, a Latin alphabet for Syriac was developed with some material promulgated.[10] It was used until around 1938, when it was replaced by a Cyrillic script. Although they did not supplant the Syriac script, the usage of the Latin script in the Syriac community has still become widespread because most of the Assyrian diaspora is in Europe and the Anglosphere, where the Latin alphabet is predominant.

In Syriac romanization, some letters are altered and would feature diacritics and macrons to indicate long vowels, schwas and diphthongs. The letters with diacritics and macrons are mostly upheld in educational or formal writing.[11]

| A | B | C | Ç | D | E | Ə | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | Ş | T | Ţ | U | V | X | Z | Ƶ | Ь | IJ/ЬJ (digraph) |

| A | Ə | Б | В | Г | Һ | D | E | Ж | З | И | J | К | Q | L | М | Н | O | П | Р | С | Т | t | У | Ф | Х | Ш | Ч | Ы | DЖ (digraph) |

The Latin letters below are commonly used when it comes to transliteration from the Syriac script to Latin:[16]

| A | Ā | B | Ḇ | C | D | Ḏ | E | Ē | Ĕ | F | G | H | Ḥ | I | J | K | Ḵ | L | M | N | O | Ō | P | Q | R | S | Š | Ṣ | T | Ṭ | Ṯ | U | Ū | V | W | X | Y | Z |

- Ā is used to denote a long "a" sound or [ɑː] as heard in "car".

- Ḏ is used to represent a voiced dental fricative [ð], the "th" sound as heard in "that".

- Ē is used to denote a long close-mid unrounded vowel, [eː].

- Ĕ is to represent an "eh" sound or [ɛ], as heard in Ninwĕ

- Ḥ represents a voiceless pharyngeal fricative ([ħ]), only upheld by Turoyo and Chaldean speakers.

- Ō represents a long "o" sound or [ɔː].

- Š is a voiceless postalveolar fricative ([ʃ]), the English digraph "sh".

- Ṣ denotes an emphatic "s" or "thick s", [sˤ].

- Ṭ is an emphatic "t", [tˤ], as heard in the word ṭla ("three").

- Ū is used to represent an "oo" sound or the close back rounded vowel [uː].

Sometimes additional letters may be used and they tend to be:

- Ḇ may be used in the transliteration of biblical Aramaic to show the voiced bilabial fricative allophone value ("v") of the letter Bēṯ.

- Ī denotes a schwa sound, usually when transliterating biblical Aramaic.

- Ḵ is utilized for the voiceless velar fricative, [x], or the "kh" sound.

- Ṯ is used to denote the "th" sound or the voiceless dental fricative, [θ].

Unicode

[edit]The Syriac alphabet was added to the Unicode Standard in September, 1999 with the release of version 3.0. Additional letters for Suriyani Malayalam were added in June, 2017 with the release of version 10.0.

Blocks

[edit]The Unicode block for Syriac is U+0700–U+074F:

| Syriac[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+070x | ܀ | ܁ | ܂ | ܃ | ܄ | ܅ | ܆ | ܇ | ܈ | ܉ | ܊ | ܋ | ܌ | ܍ | SAM | |

| U+071x | ܐ | ܑ | ܒ | ܓ | ܔ | ܕ | ܖ | ܗ | ܘ | ܙ | ܚ | ܛ | ܜ | ܝ | ܞ | ܟ |

| U+072x | ܠ | ܡ | ܢ | ܣ | ܤ | ܥ | ܦ | ܧ | ܨ | ܩ | ܪ | ܫ | ܬ | ܭ | ܮ | ܯ |

| U+073x | ܰ | ܱ | ܲ | ܳ | ܴ | ܵ | ܶ | ܷ | ܸ | ܹ | ܺ | ܻ | ܼ | ܽ | ܾ | ܿ |

| U+074x | ݀ | ݁ | ݂ | ݃ | ݄ | ݅ | ݆ | ݇ | ݈ | ݉ | ݊ | ݍ | ݎ | ݏ | ||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

The Syriac Abbreviation (a type of overline) can be represented with a special control character called the Syriac Abbreviation Mark (U+070F).

The Unicode block for Suriyani Malayalam specific letters is called the Syriac Supplement block and is U+0860–U+086F:

| Syriac Supplement[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+086x | ࡠ | ࡡ | ࡢ | ࡣ | ࡤ | ࡥ | ࡦ | ࡧ | ࡨ | ࡩ | ࡪ | |||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

HTML code table

[edit]Note: HTML numeric character references can be in decimal format (&#DDDD;) or hexadecimal format (&#xHHHH;). For example, ܕ and ܕ (1813 in decimal) both represent U+0715 SYRIAC LETTER DALATH.

Ālep̄ bēṯ

[edit]| ܕ | ܓ | ܒ | ܐ |

| ܕ | ܓ | ܒ | ܐ |

|---|---|---|---|

| ܚ | ܙ | ܘ | ܗ |

| ܚ | ܙ | ܘ | ܗ |

| ܠ | ܟܟ | ܝ | ܛ |

| ܠ | ܟ | ܝ | ܛ |

| ܥ | ܣ | ܢܢ | ܡܡ |

| ܥ | ܤ | ܢ | ܡ |

| ܪ | ܩ | ܨ | ܦ |

| ܪ | ܩ | ܨ | ܦ |

| ܬ | ܫ | ||

| ܬ | ܫ |

Vowels and unique characters

[edit]| ܲ | ܵ |

| ܲ | ܵ |

|---|---|

| ܸ | ܹ |

| ܸ | ܹ |

| ܼ | ܿ |

| ܼ | ܿ |

| ̈ | ̰ |

| ̈ | ̰ |

| ݁ | ݂ |

| ݁ | ݂ |

| ܀ | ܂ |

| ܀ | ܂ |

| ܄ | ݇ |

| ܄ | ݇ |

Comparison of scripts

[edit]Matthew 5:8 (sixth beatitude), using the Urmi dialect:

| Syriac script | Latin script

(1930) |

Cyrillic script

(before 1929, after 1938) |

Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ܛܘܼܒ̣ܵܐ ܠܐܵܢܝܼ ܕܝܼܢܵܐ ܕܸܟ̣ܝܹ̈ܐ ܒܠܸܒܵܐ: ܣܵܒܵܒ ܕܐܵܢܝܼ ܒܸܬ ܚܵܙܝܼ ܠܐܲܠܵܗܵܐ. | Ţuva l'ənij d'inə dixji b'libbə: səbəb d'ənij bit xəzij l'Ələhə. | Tyвə l'aниj d'инa dиxjи б'lиббa: caбaб d'aниj бит xaзиj l'Alaha. | Blessed are the pure in heart: for they shall see God. |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Also ܐܒܓܕ ܣܘܪܝܝܐ ʾabgad Sūryāyā.

- ^ Also pronounced/transliterated Estrangelo in Western Syriac.

- ^ Also pronounced ʾĀlap̄ or ʾOlaf (ܐܳܠܰܦ) in Western Syriac.

- ^ Among most Assyrian Neo-Aramaic speakers, the pharyngeal sound of ʿĒ (/ʕ/) is not pronounced as such; rather, it typically merges into the plain sound of ʾĀlep̄ ([ʔ] or ∅) or geminates a previous consonant.

- ^ In the final position following Dālaṯ or Rēš, ʾĀlep̄ takes the normal form rather than the final form in the Maḏnḥāyā variant of the alphabet.

- ^ In some Serṭā usages, the syāmē dots are placed diagonally when they appear above the letter Lāmaḏ.

References

[edit]- ^ "Syriac alphabet". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ P. R. Ackroyd, C. F. Evans (1975). The Cambridge History of the Bible: Volume 1, From the Beginnings to Jerome. Cambridge University Press. p. 26. ISBN 9780521099738.

- ^ Maissun Melhem (21 January 2010). "Schriftenstreit in Syrien" (in German). Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

Several years ago, the political leadership in Syria decided to establish an institute where Aramaic could be learned. Rizkalla was tasked with writing a textbook, primarily drawing upon his native language proficiency. For the script, he chose Hebrew letters.

- ^ Oriens Christianus (in German). 2003. p. 77.

As the villages are very small, located close to each other, and the three dialects are mutually intelligible, there has never been the creation of a script or a standard language. Aramaic is the unwritten village dialect...

- ^ Hatch, William (1946). An Album of Dated Syriac Manuscripts. Boston: The American Academy of Arts and Sciences, reprinted in 2002 by Gorgias Press. p. 24. ISBN 1-931956-53-7.

- ^ Nestle, Eberhard (1888). Syrische Grammatik mit Litteratur, Chrestomathie und Glossar. Berlin: H. Reuther's Verlagsbuchhandlung. [translated to English as Syriac grammar with bibliography, chrestomathy and glossary, by R. S. Kennedy. London: Williams & Norgate 1889. p. 5].

- ^ Coakley, J. F. (2002). Robinson's Paradigms and Exercises in Syriac Grammar (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-19-926129-1.

- ^ Nöldeke, Theodor and Julius Euting (1880). Kurzgefasste syrische Grammatik. Leipzig: T.O. Weigel. [translated to English as Compendious Syriac Grammar, by James A. Crichton. London: Williams & Norgate 1904. 2003 edition. pp. 10–11. ISBN 1-57506-050-7]

- ^ Nöldeke, Theodor and Julius Euting (1880). Kurzgefasste syrische Grammatik. Leipzig: T.O. Weigel. [translated to English as Compendious Syriac Grammar, by James A. Crichton. London: Williams & Norgate 1904. 2003 edition. pp. 11–12. ISBN 1-57506-050-7]

- ^ Moscati, Sabatino, et al. The Comparative Grammar of Semitic Languages. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, Germany, 1980.

- ^ S. P. Brock, "Three Thousand Years of Aramaic literature", in Aram,1:1 (1989)

- ^ Friedrich, Johannes (1959). "Neusyrisches in Lateinschrift aus der Sowjetunion". Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft (in German) (109): 50–81.

- ^ Polotsky, Hans Jakob (1961). "Studies in Modern Syriac". Journal of Semitic Studies. 6 (1): 1–32. doi:10.1093/jss/6.1.1.

- ^ Письменность и революция. Сб. 1, 1933, p. 120

- ^ [:File:Aysor cyrillic alphabet, USSR, 1930.jpg Aysor Cyrillic alphabet, from М. Бит Ләзер, В. Скоробогатов. Qтава d'аllаббит. Урха хаdта ка маdраса d'шита камета. М.: Пиjшеlи бусмина басмәхәнә кинtрунета d'әlмә d'СССР, 1930]

- ^ "Syriac Romanization Table" (PDF). Library of Congress.

- ^ Nicholas Awde; Nineb Lamassu; Nicholas Al-Jeloo (2007). Aramaic (Assyrian/Syriac) Dictionary & Phrasebook: Swadaya-English, Turoyo-English, English-Swadaya-Turoyo. Hippocrene Books. ISBN 978-0-7818-1087-6.

Sources

[edit]- Coakley, J. F. (2002). Robinson's Paradigms and Exercises in Syriac Grammar (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926129-1.

- Hatch, William (1946). An Album of Dated Syriac Manuscripts. Boston: The American Academy of Arts and Sciences, reprinted in 2002 by Gorgias Press. ISBN 1-931956-53-7.

- Kiraz, George (2015). The Syriac Dot: a Short History. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-4632-0425-9.

- Michaelis, Ioannis Davidis (1784). Grammatica Syriaca.

- Nestle, Eberhard (1888). Syrische Grammatik mit Litteratur, Chrestomathie und Glossar. Berlin: H. Reuther's Verlagsbuchhandlung. [translated to English as Syriac grammar with bibliography, chrestomathy and glossary, by R. S. Kennedy. London: Williams & Norgate 1889].

- Nöldeke, Theodor and Julius Euting (1880). Kurzgefasste syrische Grammatik. Leipzig: T.O. Weigel. [translated to English as Compendious Syriac Grammar, by James A. Crichton. London: Williams & Norgate 1904. 2003 edition: ISBN 1-57506-050-7].

- Phillips, George (1866). A Syriac Grammar. Cambridge: Deighton, Bell, & Co.; London: Bell & Daldy.

- Robinson, Theodore Henry (1915). Paradigms and Exercises in Syriac Grammar. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926129-6.

- Rudder, Joshua. Learn to Write Aramaic: A Step-by-Step Approach to the Historical & Modern Scripts. n.p.: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2011. 220 pp. ISBN 978-1461021421 Includes the Estrangela (pp. 59–113), Madnhaya (pp. 191–206), and the Western Serto (pp. 173–190) scripts.

- Segal, J. B. (1953). The Diacritical Point and the Accents in Syriac. Oxford University Press, reprinted in 2003 by Gorgias Press. ISBN 1-59333-032-4.

- Thackston, Wheeler M. (1999). Introduction to Syriac. Bethesda, MD: Ibex Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-936347-98-8.

External links

[edit]- The Syriac alphabet at Omniglot.com

- The Syriac alphabet at Ancientscripts.com

- Unicode Entity Codes for the Syriac Script

- Meltho Fonts for Syriac

- How to write Aramaic – learn the Syriac cursive scripts

- Aramaic and Syriac handwriting Archived 2018-07-23 at the Wayback Machine ʾEsṭrangēlā (classical)

- Learn Assyrian (Syriac-Aramaic) OnLine Maḏnḥāyā (eastern)

- GNU FreeFont Unicode font family with Syriac range in its sans-serif face.

- Learn Syriac Latin Alphabet on Wikiversity

Syriac alphabet

View on GrokipediaOrigins and History

Aramaic Origins

The Syriac alphabet originated as a derivative of the Imperial Aramaic script, the standardized writing system employed across the Achaemenid Empire from the late 6th to 4th centuries BCE for administrative and official purposes. This progenitor script, an abjad focused primarily on consonants with 22 letters, emerged from earlier North Semitic traditions and served as the lingua franca of the Near East, influencing various regional dialects. The Imperial Aramaic script's dissemination facilitated its adaptation for local Aramaic variants, including the Eastern dialect that would become Syriac. The script evolved through intermediate forms like Palmyrene by the 1st–3rd centuries CE.[5][6][7] By the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, Syriac-speaking communities in Mesopotamia, centered around Edessa (modern Şanlıurfa, Turkey), adopted and refined this script to encode their emerging dialect, marking the transition to a distinct writing system. This period saw the script's evolution from the waning Imperial Aramaic forms into early Syriac, driven by the need for a vernacular medium in trade, administration, and religious expression within the Osroene kingdom. The adaptation occurred amid cultural exchanges in the Parthian and early Roman eras, where Aramaic persisted as a bridge language. Estrangela, the oldest attested Syriac script variant, first appears in this context as an angular, cursive form suitable for ink-based writing.[6][5][8] The Syriac script inherited shapes traceable to Phoenician and Hebrew through the Aramaic lineage, with notable parallels in letter forms; for instance, the Syriac ʾĀlap̄, denoting the glottal stop, mirrors the Hebrew ʾālep in its simplified linear structure, both descending from the Phoenician ʾalp representing an ox head. Early inscriptions from Edessa in the 2nd century CE provide concrete evidence of this evolution, including funerary and dedicatory texts that blend Aramaic conventions with nascent Syriac features, as analyzed in collections of Osroenian epigraphy. These artifacts, often on stone or mosaic, illustrate the script's initial use in non-Christian settings before its broader application.[6][7][9] The script's development coincided with the rise of Syriac Christianity in the 2nd century CE, where it became instrumental in translating sacred texts, notably the Peshitta, the standard Syriac version of the Bible. The Old Testament Peshitta, translated from Hebrew around this time in Edessa, utilized the emerging script to render Aramaic-influenced interpretations, fostering a literary tradition that solidified Syriac's role in early Christian communities across Mesopotamia and beyond. This linkage elevated the alphabet from administrative tool to vehicle for theological expression.[10][5]Historical Development and Usage

The Syriac alphabet's oldest form, Estrangela, is attested from the 1st to 2nd centuries CE and served as the classical script for literary and liturgical texts in the Syriac language through the 8th century, reflecting the alphabet's adaptation for Syriac phonology while maintaining consonantal roots from earlier Aramaic scripts. This angular, monumental style was widely employed in early Christian manuscripts. By the 8th century, practical needs for faster writing led to the development of cursive variants, including Serto in the West Syriac tradition; Madnhaya, a later Eastern variant, emerged around the 13th–16th centuries to facilitate everyday scribal work in monasteries and churches. These evolutions marked a shift from the formal Estrangela to more fluid forms, with Estrangela continuing in use for high-status religious codices into later periods.[11][12][13] The alphabet's geographical spread began in key centers like Edessa (modern Urfa, Turkey), Nisibis (modern Nusaybin, Turkey), and Antioch (modern Antakya, Turkey), where Syriac-speaking Christian communities flourished from the 4th century onward, establishing schools and scriptoria that disseminated the script across the Roman and Persian empires. From these hubs, the script extended to monasteries in the Middle East, including those in Tur Abdin and the Syrian desert, preserving Syriac texts amid political upheavals. By the 6th century, missionaries carried the Syriac alphabet to India, particularly the [Malabar Coast](/page/Malabar Coast), where it influenced the liturgy of the Saint Thomas Christians and was used in local manuscripts blending Syriac with Malayalam elements. In the diaspora, the script reached [Central Asia](/page/Central Asia) and Europe through trade and migration, with communities maintaining its use in scattered enclaves.[14][15][16] Syriac literature, inscribed primarily in the Estrangela script during its formative phase, includes seminal works like the hymns of Ephrem the Syrian (c. 306–373 CE), poetic compositions on theology and biblical themes that established Syriac as a vehicle for Christian mysticism and were copied extensively in Edessan manuscripts. Later, in the 13th century, Bar Hebraeus (1226–1286 CE), a polymath bishop in the West Syriac tradition, composed chronicles such as the Chronicon Syriacum, a comprehensive world history blending secular and ecclesiastical narratives, often rendered in the Serto script for accessibility in monastic libraries. These texts underscore the alphabet's role in preserving Syriac intellectual heritage, from poetic liturgy to historical scholarship, influencing subsequent generations of writers.[17][18][19] Denominational traditions shaped the alphabet's usage distinctly: the East Syriac Church (Assyrian Church of the East and Chaldean Catholic Church) favored the Madnhaya script, a precise cursive form suited to their liturgical books in regions like northern Iraq, while the West Syriac Church (Syriac Orthodox and Syriac Catholic Churches) adopted Serto, a more angular cursive for hymns and rituals in Syria and Lebanon. This bifurcation, emerging around the 8th century amid Christological debates, reinforced script variants as markers of ecclesiastical identity, with each tradition developing unique vowel-pointing systems to denote pronunciation in worship.[11][20] The alphabet's prominence waned following the Arab conquests of the 7th century, as Arabic supplanted Syriac in administration and daily life across the Levant and Mesopotamia, confining the script largely to ecclesiastical contexts despite its adaptation for writing Arabic in Garshuni—a system using Syriac letters for Arabic texts with earliest evidence from the 12th century and complete literary texts from the 14th century among West Syriac communities to bridge linguistic shifts. Ottoman persecutions in the 19th and early 20th centuries, culminating in the 1915 Sayfo genocide, decimated Syriac-speaking populations and scattered manuscripts, accelerating the script's decline as survivors fled to diaspora communities. A 20th-century revival tied to Assyrian nationalism reasserted the alphabet's cultural significance, with intellectuals promoting Syriac education and publications to foster ethnic identity amid modernization.[21][22][23] In the 21st century, the Syriac alphabet persists in liturgical use among diaspora communities in Europe, North America, and Australia, where Syriac Orthodox and Assyrian churches conduct services in Classical Syriac, supported by digital resources and heritage programs to teach the script to younger generations. Garshuni continues in niche applications, such as transcribing Arabic prayers in Syriac letters for bilingual worship in non-Arabic regions like Sweden and the United States, ensuring the alphabet's role in maintaining communal bonds despite globalization.[24][25][26]Phonology

Consonantal Sounds

The Syriac alphabet comprises 22 consonants that form the core of its phonological system, reflecting the Semitic heritage of the language with a mix of stops, fricatives, approximants, and emphatics. These letters encode the primary consonantal sounds used in Classical Syriac, a Middle Aramaic dialect, and exhibit allophonic variations influenced by surrounding vowels. Unlike vocalic elements, which are often implied or marked separately, the consonants provide the skeletal structure of words, with their phonetic values largely consistent across historical texts but subject to dialectal and contextual shifts.[27] The following table lists the 22 consonants in traditional order, including their names, primary IPA transcriptions for Classical Syriac, and notable allophones such as spirantized forms. Emphatic consonants, marked with a dot in some notations, feature pharyngealization or velarization, distinguishing them as a hallmark of Semitic phonology (e.g., Ṭēṯ as /tˤ/, Ṣāḏē as /sˤ/, and Qop as /q/). For linguistic context, equivalents in Hebrew and Arabic are included, highlighting shared Proto-Semitic roots despite divergent evolutions (e.g., Syriac Gāmal /ɡ/ corresponds to Hebrew Gimel /ɡ/ but Arabic Jīm /dʒ/).[28][29]| Letter | Name | IPA (Primary) | Allophones/Notes | Hebrew Equivalent | Arabic Equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ܐ | ʾĀlap̄ | /ʔ/ | Glottal stop, often silent word-initially | א (Aleph /ʔ/) | أ (Alif /ʔ/) |

| ܒ | Bēṯ | /b/ | /v/ post-vocalic (spirantized) | ב (Bet /b/) | ب (Bāʾ /b/) |

| ܓ | Gāmal | /ɡ/ | /ɣ/ post-vocalic (spirantized) | ג (Gimel /ɡ/) | ج (Jīm /dʒ/) |

| ܕ | Dālaṯ | /d/ | /ð/ post-vocalic (spirantized) | ד (Dalet /d/) | د (Dāl /d/) |

| ܗ | Hē | /h/ | Voiceless glottal fricative | ה (He /h/) | ه (Hāʾ /h/) |

| ܘ | Waw | /w/ | Labial-velar approximant | ו (Vav /v/) | و (Wāw /w/) |

| ܙ | Zain | /z/ | Voiced alveolar fricative | ז (Zayin /z/) | ز (Zāy /z/) |

| ܚ | Ḥēṯ | /ħ/ | Voiceless pharyngeal fricative | ח (Ḥet /χ/) | ح (Ḥāʾ /ħ/) |

| ܛ | Ṭēṯ | /tˤ/ | Voiceless emphatic alveolar stop | ט (Tet /t/) | ط (Ṭāʾ /tˤ/) |

| ܝ | Yōḏ | /j/ | Palatal approximant | י (Yod /j/) | ي (Yāʾ /j/) |

| ܟ | Kāp | /k/ | /x/ post-vocalic (spirantized) | כ (Kaf /k/) | ك (Kāf /k/) |

| ܠ | Lāmaḏ | /l/ | Alveolar lateral approximant | ל (Lamed /l/) | ل (Lām /l/) |

| ܡ | Mim | /m/ | Bilabial nasal | מ (Mem /m/) | م (Mīm /m/) |

| ܢ | Nun | /n/ | Alveolar nasal | נ (Nun /n/) | ن (Nūn /n/) |

| ܣ | Semkaṯ | /s/ | Voiceless alveolar fricative | ס (Samekh /s/) | س (Sīn /s/) |

| ܥ | ʿĒ | /ʕ/ | Voiced pharyngeal fricative | ע (Ayin /ʔ/) | ع (ʿAyn /ʕ/) |

| ܦ | Pē | /p/ | /f/ post-vocalic (spirantized) | פ (Pe /p/) | ف (Fāʾ /f/) |

| ܨ | Ṣāḏē | /sˤ/ | Voiceless emphatic alveolar fricative | צ (Tsadi /ts/) | ص (Ṣād /sˤ/) |

| ܩ | Qop | /q/ | Voiceless uvular stop | ק (Qof /k/) | ق (Qāf /q/) |

| ܪ | Rēš | /r/ | Alveolar trill or tap | ר (Resh /ʁ/) | ر (Rāʾ /r/) |

| ܫ | Šin | /ʃ/ | Voiceless postalveolar fricative | ש (Shin /ʃ/) | ش (Shīn /ʃ/) |

| ܬ | Tāw | /t/ | /θ/ post-vocalic (spirantized) | ת (Tav /t/) | ت (Tāʾ /t/) |

Vocalic System

The Syriac script functions as an abjad, primarily denoting consonants while leaving vowels largely implicit, relying on the reader's knowledge of the language for interpretation. To indicate long vowels, Syriac employs matres lectionis—specific consonants repurposed as vowel carriers: ʾālap (ܐ) represents /aː/, yodh (ܝ) denotes /iː/, and waw (ܘ) signifies /uː/. These are inserted into the consonantal skeleton to mark prolonged vowel sounds, such as in the word ܐܝܟܐ (ʾykʾ, "where"), where ʾālap and yodh serve dual roles as both consonants and vowels. This system, inherited from earlier Aramaic traditions, allows for compact writing but introduces potential ambiguities, as the same sequence of consonants can correspond to multiple vocalizations depending on context or dialect. To address the limitations of implicit notation and ensure precise pronunciation, especially in liturgical and scholarly contexts, explicit vowel diacritics were developed in the 6th century CE. These marks, inspired by Greek letter forms, were initially used to distinguish homographs and foreign terms but evolved into a full vocalization system by the 7th century, aiding non-native scribes and preserving oral traditions amid linguistic shifts. Short vowels are indicated by superscript points: pṫāḥā (ܦܬܚܐ, a single dot below the line for /a/) and zqāpā (ܙܩܦܐ, two dots above for /e/), among others like ḥḇāšā (ܚܒܫܐ, for /o/) and rukkāḵā (ܪܘܟܟܐ, for /u/). This innovation marked a transition from defective to plene writing, enhancing readability without altering the core consonantal structure.[31] Differences between East and West Syriac traditions emerged in the representation of the reduced vowel /ə/ (schwa), reflecting divergent scribal practices post-5th century schisms. In East Syriac (associated with the Church of the East), /ə/ is typically marked by a diamond-shaped diacritic (mṭaʿpṭā, ܡܛܥܦܛܐ), positioned above the consonant, as seen in vocalized Psalters from Mesopotamia. Conversely, West Syriac (used by the Syriac Orthodox Church) employs two vertical dots (often called šūšā or majlīanā, ܡܓܠܝܢܐ), placed above or below to indicate the same sound, a convention solidified in Antiochene manuscripts. These variations not only highlight regional phonological preferences but also influenced later Neo-Aramaic orthographies.[32] The absence of full vocalization in unpointed texts often leads to interpretive challenges, as the consonantal framework alone cannot uniquely determine vowel placement, resulting in polysemous readings resolved through grammatical rules, syntax, or exegetical tradition. This ambiguity persists in classical literature, where, for instance, the skeleton ܟܬܒ (ktb) could vocalize as /katab/ ("he wrote") or /kōtab/ ("scribes"), depending on tense and aspect. In modern dialects such as Turoyo (also known as Suryoyo), which continue using the Syriac script, the vocalic system incorporates vowel harmony, where affix vowels assimilate to the height or backness of root vowels—e.g., a suffix /a/ may shift to /e/ after front vowels like /i/ in words like "house" (baytā) influencing possessive endings. Such features extend the traditional system's adaptability while underscoring its role in preserving Aramaic continuity.[33]Script Variants

Estrangela

Estrangela (ܐܣܛܪܢܓܠܐ), the classical and oldest variant of the Syriac script, features bold, angular letter forms that are generally disconnected or only loosely joined, lending it a monumental and stately appearance suitable for stone inscriptions and the careful copying of early manuscripts.[34][20] This non-cursive style contrasts with later developments, emphasizing clarity and durability over writing speed.[35] Historically, Estrangela served as the primary script from the 1st to the 10th centuries CE, dominating all early Syriac literature and epigraphy, including the oldest dated manuscript from 411 CE.[36] It was employed for sacred texts such as Bibles and liturgical hymns, as well as official documents from Edessan and monastic centers.[35] As the standard for printed Syriac until the 19th century, it preserved the script's ancient aesthetic in early typographic editions.[37] The script consists of 22 consonant letters, each with upright, robust shapes adapted for isolated, initial, medial, and final positions, though connections remain minimal to maintain legibility. Distinctive forms include the two-legged Alaph (ܐ) and the looped Beth (ܒ), with angular strokes evident in letters like Dalath (ܕ) and Taw (ܬ). Below is a representative table of the standard letters in their isolated Estrangela forms:| Name | Isolated Form | Phonetic Value |

|---|---|---|

| Alaph | ܐ | ʾ (glottal stop) or vowel carrier |

| Beth | ܒ | b / v |

| Gamal | ܓ | g / ġ |

| Dalath | ܕ | d / ḏ |

| He | ܗ | h |

| Waw | ܘ | w / ō |

| Zain | ܙ | z |

| Heth | ܚ | ḥ |

| Teth | ܛ | ṭ |

| Yudh | ܝ | y / ī |

| Kaph | ܟ | k / ḵ |

| Lamed | ܠ | l |

| Mim | ܡ | m |

| Nun | ܢ | n |

| Semkath | ܣ | s |

| 'E | ܥ | ʿ |

| Pe | ܦ | p / f |

| Sadhe | ܨ | ṣ |

| Qoph | ܩ | q |

| Resh | ܪ | r |

| Shin | ܫ | š |

| Taw | ܬ | t / ṯ |

Madnhaya

The Madnhaya script, also known as the Eastern Syriac or Swadaya script, is a cursive variant of the Syriac alphabet characterized by its angular, connected letter forms that slant slightly to the right, facilitating fluid handwriting.[40] It developed as a practical adaptation for everyday writing, with most letters joining within words to form a continuous flow, though certain letters like ʾĀlap̄ and Waw remain disconnected.[5] In addition to cursive forms, Madnhaya uses superscript dots to distinguish letters that are otherwise identical in shape, such as semkat from shin. This script is predominantly used in the liturgical and literary traditions of the Assyrian Church of the East and the Chaldean Catholic Church, where it supports the East Syriac dialect.[41] Madnhaya is known from around 600 CE as an angular evolution from the more monumental Estrangela script, initially serving as a chancery hand for manuscripts, correspondence, and administrative documents in the Church of the East, becoming more distinctive by the 13th century.[5] These adaptations allowed for efficient production of religious texts and personal letters in regions under East Syriac influence, such as Mesopotamia and Persia.[37] The vowel system in Madnhaya employs a set of diacritical marks derived from Estrangela, consisting primarily of dots placed above, below, or beside consonants to indicate short and long vowels.[41] Notable examples include pṯāḥā (/a/, two horizontal dots below), zqāpā (/e/, two vertical dots to the right), ṣwāḏā (/i/, two slanted dots above), and rukkāḵā (/u/, two horizontal dots above). These marks, formalized in the 8th century, enhance readability in liturgical chanting and scholarly works. Majliyānā (~), a tilde-like mark placed above or below, indicates spirantized pronunciation of bgdkpt letters. Phonetic adaptations in Madnhaya align closely with East Syriac pronunciations, such as emphatic consonants rendered through subtle letter angulations.[5][42] Exemplary letter forms in Madnhaya highlight its cursive connections; for instance, the letter Mīm (ܡ) flows with a descending tail that links seamlessly to following letters like Nūn (ܢ), creating elongated, slanted ligatures as in the word ܡܢ (mn, "from").[40] Similarly, the initial form of Lāmaḏ (ܠ) curves upward to connect with preceding elements, while its medial form adopts a hooked base for continuity. These features exemplify the script's emphasis on practicality, with 18 of the 22 letters capable of joining. In modern contexts, Madnhaya has seen renewed application in Neo-Assyrian (Sureth) print media, including newspapers and books published by Assyrian communities since the early 2000s, to preserve cultural identity amid diaspora.[43] Digital support has expanded post-2000 through Unicode integration and software keyboards, such as Keyman for Assyrian Neo-Aramaic, enabling typing on Windows and mobile devices for online publishing and education.[44]Serto

The Serto script, also known as Serta or Pšīṭā, is the primary cursive variant of the Syriac alphabet used in West Syriac traditions, characterized by its rounded, flowing letter forms that facilitate fluid connections between characters.[38] This aesthetic emphasizes elegance and readability in handwritten manuscripts, with letters often exhibiting gentle curves and arches, such as the distinctly curved Sādē (ܨ) in connected forms, where the tail loops smoothly to link with subsequent letters.[45] Serto's design reflects adaptations for rapid writing while maintaining legibility, making it ideal for extensive liturgical and literary texts.[5] Developed from the 8th century onward, Serto evolved under the influence of local handwriting styles in regions like Syria and Lebanon, transitioning from earlier monumental forms into a more practical cursive suitable for everyday ecclesiastical use.[38] It shares roots with other Syriac variants but diverged to suit Western liturgical needs, becoming the standard in the Syriac Orthodox Church and Maronite Church traditions, where it supports the vocalization of prayers, hymns, and biblical commentaries.[5][46] In terms of vocalization, Serto employs a two-dot system for indicating short vowels, with pairs of dots placed above or below letters—such as two diagonal dots for /e/ (zlamā ṣʿādā) and a dot below for /a/ (pṯāḥā)—alongside unique marks like the rbāṭā, a diacritic representing the vowel /o/.[47] These notations, refined over centuries, enhance precision in reading sacred texts without altering the core consonantal structure. In contemporary applications, Serto appears in Syriac-Arabic bilingual texts, particularly Garshuni manuscripts where Arabic content is rendered in Syriac letters for cultural and religious continuity among West Syriac communities.[11] However, digital typesetting poses challenges, including inconsistent font rendering of cursive ligatures and diacritic positioning in software like Microsoft Word, necessitating specialized tools such as TeX-based systems for accurate reproduction.[48]Letter Forms and Features

Standard Letters

The Syriac alphabet comprises 22 standard consonant letters, derived from the Imperial Aramaic script and arranged in a fixed order known as the ʾabgadā sequence, mirroring ancient Semitic alphabets. These letters serve as the core of the writing system, each with a traditional name, a numerical value for gematria (a system of assigning numbers to letters for interpretive or computational purposes), and basic isolated forms that vary slightly across the three main scripts: Estrangela (the oldest and most calligraphic), Serto (western, cursive), and Madnhaya (eastern, used in printed texts). As an abjad, Syriac letters represent consonants primarily, with vowels indicated optionally via diacritics; the numerical values follow a pattern where the first nine letters denote 1–9, the next nine 10–90 in tens, and the final four 100–400. The names of the letters originate from Proto-Semitic roots, often linked to pictographic or acrophonic principles in earlier scripts like Proto-Sinaitic, where the name evoked an object or concept beginning with the letter's sound—for instance, ʾĀlap from ʾalp- meaning "ox," symbolizing the animal's head shape in early forms. This etymological heritage underscores the alphabet's evolution from ideographic to phonetic representation across Semitic languages. Scholarly analysis traces these names through comparative Semitistics, confirming their continuity from Phoenician and Hebrew equivalents. Basic shapes of the letters are presented in their isolated (non-connected) forms to illustrate neutral appearances, typically vertical or curved strokes adapted for right-to-left writing. In Estrangela, forms are angular and monumental; Serto features more fluid, looped connections even in isolation; Madnhaya is blockier for clarity in modern use. Below is a comprehensive table summarizing the letters in alphabetical order, using Unicode representations for Estrangela (primary classical form), alongside names, transliterations, numerical values, brief etymologies, and shape descriptions. A separate pronunciation guide table provides approximate IPA values for the consonantal sounds, cross-referencing broader phonological context without detailing vocalization.| Letter (Estrangela) | Name | Transliteration | Numerical Value | Etymology (Semitic Root) | Basic Shape Description (Isolated) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ܐ | ʾĀlap | ʾ | 1 | ʾalp- "ox" (head shape) | Vertical line with possible crossbar; simple upright stroke. |

| ܒ | Bēth | b | 2 | bayt- "house" (tent floorplan) | Horizontal base with verticals; box-like. |

| ܓ | Gāmal | g | 3 | gamal- "camel" (throwing stick) | Curved horizontal with vertical tail; hook-like. |

| ܕ | Dālaṯ | d | 4 | dalt- "door" (fish or door panel) | Vertical with triangular head; arrow-point. |

| ܗ | Hē | h | 5 | hill- "fence" or "window" (wall) | Two verticals connected by horizontals; ladder-like. |

| ܘ | Waw | w | 6 | waw- "hook" (nail) | Curved hook or Y-shape; tent peg. |

| ܙ | Zain | z | 7 | zayin- "weapon" (plow or sword) | Zigzag or double curve; blade form. |

| ܚ | Ḥēṯ | ḥ | 8 | ḥiṯ- "fence" or "wall" (thread) | H with crossbar; lattice. |

| ܛ | Ṭēṯ | ṭ | 9 | ṭēṯ- "wheel" or "basket" (mark) | Circle or enclosed loop; coil. |

| ܝ | Yūḏ | y | 10 | yad- "hand" (arm) | Small vertical stroke; arm extended. |

| ܟ | Kāp | k | 20 | kap- "palm" (hand) | Open hand shape; bent arm. |

| ܠ | Lāmaḏ | l | 30 | lamd- "goad" (ox goad) | Oblique stroke with hook; staff. |

| ܡ | Mīm | m | 40 | mayim- "water" (waves) | Wavy horizontals; rippling lines. |

| ܢ | Nūn | n | 50 | nūn- "fish" or "sprout" (serpent) | Curved vertical; snake or fish. |

| ܣ | Semkaṯ | s | 60 | simk- "support" (fish or prop) | Stacked horizontals; pillar. |

| ܥ | ʿĒ | ʿ | 70 | ʿayin- "eye" (eye) | Curved enclosure; circle or eye. |

| ܦ | Pē | p | 80 | pē- "mouth" (edge) | Squared mouth; open square. |

| ܨ | Sāḏē | ṣ | 90 | ṣade- "hunt" or "plant" (hook) | Vertical with cross and foot; plant. |

| ܩ | Qōp | q | 100 | qop- "back of head" (monkey or needle) | Circle with vertical; eye or loop. |

| ܪ | Rēš | r | 200 | raʾš- "head" (head) | Rounded head with stroke; profile. |

| ܫ | Šīn | š | 300 | šin- "tooth" (composite) | W with teeth; arrow or shine. |

| ܬ | Taw | t | 400 | taw- "mark" (cross) | Cross or X; mark. |

| Letter Name | Transliteration | IPA (Approximate Consonantal Sound) |

|---|---|---|

| ʾĀlap | ʾ | /ʔ/ (glottal stop) or silent carrier |

| Bēth | b | /b/ (voiced bilabial stop) |

| Gāmal | g | /ɡ/ (voiced velar stop) |

| Dālaṯ | d | /d/ (voiced dental stop) |

| Hē | h | /h/ (voiceless glottal fricative) |

| Waw | w | /w/ (labial glide) |

| Zain | z | /z/ (voiced alveolar fricative) |

| Ḥēṯ | ḥ | /ħ/ (voiceless pharyngeal fricative) |

| Ṭēṯ | ṭ | /tˤ/ (emphatic dental stop) |

| Yūḏ | y | /j/ (palatal glide) |

| Kāp | k | /k/ (voiceless velar stop) |

| Lāmaḏ | l | /l/ (alveolar lateral) |

| Mīm | m | /m/ (bilabial nasal) |

| Nūn | n | /n/ (alveolar nasal) |

| Semkaṯ | s | /s/ (voiceless alveolar fricative) |

| ʿĒ | ʿ | /ʕ/ (voiced pharyngeal fricative) |

| Pē | p | /p/ (voiceless bilabial stop) |

| Sāḏē | ṣ | /sˤ/ (emphatic alveolar fricative) |

| Qōp | q | /q/ (voiceless uvular stop) |

| Rēš | r | /r/ (trilled alveolar) |

| Šīn | š | /ʃ/ (voiceless postalveolar fricative) |

| Taw | t | /t/ (voiceless dental stop) |

Contextual Variations

The Syriac script exhibits significant contextual variations in letter shapes, adapting to their position within a word—initial (at the beginning), medial (in the middle), or final (at the end)—to support its cursive nature. This positional system allows for fluid connections between most letters, though eight letters (ʾĀlap, Dālaṯ, Hē, Waw, Zain, Ṣāḏē, Rēš, and Taw; with Semkaṯ in some early Estrangela manuscripts) do not connect to a following letter, and others rarely join on the left. For instance, the letter Bēṯ (ܒ) appears in a straight, isolated form when standalone, but in its final position, it often curls downward with a flourish to terminate the word smoothly, enhancing readability in continuous writing.[27][38][49] Ligatures, where two or more letters fuse into a single glyph, are common in Syriac to maintain cursive flow, particularly in frequent combinations. A prominent example is the Lāmad-ʾĀlap̄ ligature in the word for "God," ʾAlāhā (ܐܠܗܐ), where the vertical stroke of Lāmad merges seamlessly with the head of ʾĀlap̄, creating a compact, elongated form that avoids disconnection. Other notable ligatures include Waw-ʾĀlap̄ and certain finals like Mīm with following letters, which are rendered as unified shapes in traditional manuscripts. These fused forms not only economize space but also reflect scribal conventions for aesthetic harmony.[48] Cursive connection rules vary across script variants, with Serto (Western) employing more pronounced joins and rounded curves than the angular Estrangela (classical). In Estrangela, connections are looser, preserving distinct letter identities for monumental or early biblical texts, while Serto's tighter ligatures and medial elongations facilitate faster handwriting in later liturgical works. Madnhaya (Eastern) follows Estrangela more closely but incorporates subtle cursive adaptations in modern usage. These differences arose as scribes prioritized efficiency in variant-specific traditions.[39][5] Historically, these variations evolved from early Aramaic cursive hands used on perishable materials like parchment for legal and administrative documents, adapting over centuries to accelerate manuscript production without sacrificing legibility. By the 3rd century CE, such forms were standard in Syriac Christian texts, with Estrangela formalizing a balanced style for durability in codices.[5][1] In digital rendering, OpenType features enforce positional substitutions and required ligatures (e.g., Rēš with seyāmē dots) to replicate these dynamics, preventing errors like disjointed finals or mismatched joins that could create visual ambiguities resembling optical illusions in connected sequences. For example, improper handling of Bēṯ's final curl might distort word boundaries, mimicking unintended letter fusions; thus, fonts must apply glyph variants contextually to preserve the script's fluid yet precise appearance.[50]Diacritical Marks

Diacritical marks in the Syriac alphabet serve to distinguish phonetically similar letters, indicate spirantization or plosiveness of consonants, mark grammatical categories such as plurality, and denote silent letters, enhancing clarity in reading and interpretation. These marks, collectively known as nuqūṣē (points or dots), are superimposed on letters and are optional, with their usage varying by script variant and historical period. In the Madnhaya and Serto scripts, they are more prevalent for disambiguation, while Estrangela relies less on them due to distinct letter shapes. The majlīyānā (ܡܓܠܝܢܐ), resembling a tilde (~) or line, is placed above or below a letter primarily in the Eastern (Madnhaya) variant to differentiate homographic consonants that appear identical in basic form. For instance, it can modify ܟ kāp to represent the affricate /tʃ/ in Assyrian Neo-Aramaic. This mark emerged as a modern orthographic tool to resolve ambiguities in printed and digital texts, though it is absent in many classical manuscripts.[27] Spirantization of the bgdkpt consonants (ܒ bēṯ, ܓ gāmal, ܕ dālaṯ, ܟ kāp, ܦ pē, ܬ tāw) is denoted by the rūkkāḵā (ܪܘܟܟܐ, "soft" or light stroke, U+0742 ◌݂), a horizontal line above the letter indicating the fricative form, such as /f/ from ܦ pē (ܦ݂). Conversely, the qūššāyā (ܩܘܫܝܐ, "hard" or heavy stroke, U+0741 ◌݁), placed below, marks the plosive pronunciation, ensuring precise articulation in both spoken and written Syriac. These strokes reflect the language's phonetic shifts post-vocalization and are essential in liturgical and scholarly readings. The syāmē (ܣܝܡܐ, "twin dots," often U+0743 ◌݃ or U+0308 ¨), two vertical dots above a noun or adjective, primarily indicates the plural form, a key grammatical marker in Syriac morphology. For example, the singular ܟܬܒܐ ktāḇā ("book") becomes plural as ܟܬܒܐ̈ ktāḇē ("books") with the syāmē. While its core function is morphological, studies show occasional phonological uses in early texts to signal vowel quality, though this is secondary and debated. Irregular plurals also receive the syāmē to avoid ambiguity.[51] The mṭalqānā (ܡܛܠܩܢܐ, "delivered" or linea occultans, U+0747 ◌݇), a vertical or oblique line above or below a letter, signals that the consonant is silent, particularly in final positions to emphasize preceding vowels or resolve orthographic redundancy. It is commonly applied to final ʾālap (ܐ) or hē (ܗ) when unpronounced, aiding in smooth recitation of poetic or prose texts. Matres lectionis—ʾālap (ܐ), waw (ܘ), and yodh (ܝ)—function orthographically as semi-vowels, inserted to represent long vowels (ā, ō/u, ē/i) while retaining consonantal potential, thus bridging consonantal script and vocalic indication without dedicated vowel letters. This integration allows flexible reading of unpointed texts, where context determines their vocalic role. Application of these marks is inconsistent across Syriac literature: classical texts from the 5th–8th centuries often omit them entirely or use them sporadically for emphasis, relying on reader familiarity, whereas modern printed editions and digital fonts standardize their inclusion for accessibility. Software rendering poses challenges, as diacritics may misalign or fail to stack properly in non-specialized tools, complicating digital preservation and editing of Syriac corpora.[52] Vowel diacritics occasionally overlap with these marks in pointed texts, but the latter focus on consonantal and grammatical distinctions.Modern Applications

Romanization Systems

Romanization of the Syriac alphabet into the Latin script facilitates the transcription of texts for academic research, library cataloging, and computational analysis. The primary standard is the ALA-LC romanization table, developed by the American Library Association and the Library of Congress, which provides a systematic mapping of the 22 consonants and associated diacritics while addressing variations between script forms like Estrangela, Serto, and Madnhaya. This system prioritizes phonetic accuracy for Classical Syriac, using diacritics to distinguish emphatic sounds. The ALA-LC table does not distinguish between hard and soft (spirantized) forms of the bgdkpt letters, romanizing them with single base letters.[53] The ALA-LC table references Estrangela letter forms but applies to pointed texts in Serto (West Syriac) and East Syriac variants, with specific notes for vowel rendering. Consonants are transcribed as follows, with examples including ʾ for ʾĀlap̄ (ܐ), which is often silent or glottal; ḥ for Ḥēṯ (ܚ), representing a voiceless pharyngeal fricative; and ṣ for Ṣāḏē (ܨ), an emphatic sibilant marked by an underdot to indicate pharyngealization. Emphatic letters like Ṭēṯ (ܛ) become ṭ. Vowels are handled with Latin letters and diacritics for length (e.g., a, ā, e, ē, i, ī, o, ō, u, ū), rendering distinctions from pointing across variants.[53] For modern Syriac used in neo-Aramaic contexts by Assyrian communities, a separate romanization system employs underdots for "strong" (emphatic or guttural) consonants and explicit vowel marks to capture contemporary pronunciation in regions like northern Iraq and Syria. This approach differs from ALA-LC by prioritizing accessibility for non-scholarly texts, such as toponyms, and avoids some diacritics for readability in print and digital media.[54] Variant-specific considerations arise due to phonological differences between East and West Syriac traditions, influencing romanization choices. In East Syriac, letters like Kāp̄ (ܟ) may require 'kh' for its spirantized sound in certain systems, while West Syriac often uses 'k' or 'ḥ' alignments closer to Arabic conventions; however, ALA-LC maintains a unified scheme with optional notes for pronunciation variants to ensure consistency in cataloging. The system's pros include precision for emphatic consonants (e.g., ṣ for Ṣāḏē avoids confusion with s), but cons involve complexity from diacritics, leading to simplified variants for popular publications that drop marks like underdots.[53] Historical schemes from the 19th century, employed by European and American missionaries in translating Syriac liturgies and grammars, typically adapted ad hoc Latin equivalents influenced by biblical Hebrew romanization, such as 'ch' for Ḥēṯ, but these lacked standardization and have been largely replaced by ALA-LC for modern scholarly and institutional applications.[53] Digital tools support these systems through online converters that automate transliteration. For instance, the Lexilogos Syriac-Latin keyboard maps input to ALA-LC-style romanization, allowing users to type Syriac letters and generate Latin output with diacritics for vowels and emphatics. Similar converters, like Aksharamukha, handle script-to-Latin conversion across variants, aiding in the processing of digitized manuscripts. Ongoing debates in romanization focus on vowel representation, particularly whether to fully transcribe short vowels via diacritics (as in ALA-LC) or rely on context for matres lectionis like Waw (ܘ) and Yōḏ (ܝ), balancing fidelity to phonology with textual readability in non-specialist contexts.[55][56]| Syriac Letter (Estrangela) | Name | ALA-LC Romanization | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| ܐ | ʾĀlap̄ | ʾ | Glottal stop or silent; initial only. |

| ܒ | Bēṯ | b | - |

| ܓ | Gāmal | g | - |

| ܕ | Dālaṯ | d | - |

| ܗ | Hē | h | Often silent word-finally. |

| ܘ | Waw | w | Consonant or mater lectionis for /u/, /o/. |

| ܙ | Zayn | z | - |

| ܚ | Ḥēṯ | ḥ | Pharyngeal fricative. |

| ܛ | Ṭēṯ | ṭ | Emphatic [tˤ]. |

| ܝ | Yōḏ | y | Consonant or mater lectionis for /i/, /e/. |

| ܟ | Kāp̄ | k | - |

| ܠ | Lāmaḏ | l | - |

| ܡ | Mīm | m | - |

| ܢ | Nūn | n | - |

| ܣ | Semkaṯ | s | - |

| ܥ | ʿĒ | ʿ | Pharyngeal approximant. |

| ܦ | Pē | p | - |

| ܨ | Ṣāḏē | ṣ | Emphatic [sˤ]. |

| ܩ | Qoph | q | Uvular . |

| ܪ | Rēš | r | - |

| ܫ | Šīn | š | [ʃ]; distinguished from Sīn (s) by dot. |

| ܬ | Taw | t | - |