Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Seamount

View on Wikipedia

| Marine habitats |

|---|

| Coastal habitats |

| Ocean surface |

| Open ocean |

| Sea floor |

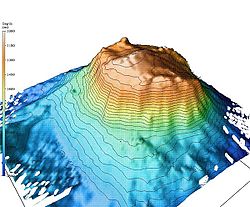

A seamount is a large submarine landform that rises from the ocean floor without reaching the water surface (sea level), and thus is not an island, islet, or cliff-rock. Seamounts are typically formed from extinct volcanoes that rise abruptly and are usually found rising from the seafloor to 100–4,000 m (330–13,120 ft) in height. They are defined by oceanographers as independent features that rise to at least 1,000 m (3,281 ft) above the seafloor, characteristically of conical form.[1] The peaks are often found hundreds to thousands of meters below the surface, and are therefore considered to be within the deep sea.[2] During their evolution over geologic time, the largest seamounts may reach the sea surface where wave action erodes the summit to form a flat surface. After they have subsided and sunk below the sea surface, such flat-top seamounts are called "guyots" or "tablemounts".[1]

Earth's oceans contain more than 14,500 identified seamounts,[3] of which 9,951 seamounts and 283 guyots, covering a total area of 8,796,150 km2 (3,396,210 sq mi), have been mapped[4] but only a few have been studied in detail by scientists. Seamounts and guyots are most abundant in the North Pacific Ocean, and follow a distinctive evolutionary pattern of eruption, build-up, subsidence and erosion. In recent years, several active seamounts have been observed, for example Kamaʻehuakanaloa (formerly Lōʻihi) in the Hawaiian Islands.

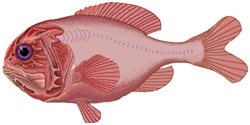

Because of their abundance, seamounts are one of the most common marine ecosystems in the world. Interactions between seamounts and underwater currents, as well as their elevated position in the water, attract plankton, corals, fish, and marine mammals alike. Their aggregational effect has been noted by the commercial fishing industry, and many seamounts support extensive fisheries. There are ongoing concerns on the negative impact of fishing on seamount ecosystems, and well-documented cases of stock decline, for example with the orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus). 95% of ecological damage is done by bottom trawling, which scrapes whole ecosystems off seamounts.

Because of their large numbers, many seamounts remain to be properly studied, and even mapped. Bathymetry and satellite altimetry are two technologies working to close the gap. There have been instances where naval vessels have collided with uncharted seamounts; for example, Muirfield Seamount is named after the ship that struck it in 1973. However, the greatest danger from seamounts are flank collapses; as they get older, extrusions seeping in the seamounts put pressure on their sides, causing landslides that have the potential to generate massive tsunamis.

Geography

[edit]

Seamounts can be found in every ocean basin in the world, distributed extremely widely both in space and in age. A seamount is technically defined as an isolated rise in elevation of 1,000 m (3,281 ft) or more from the surrounding seafloor, and with a limited summit area,[5] of conical form.[1] There are more than 14,500 seamounts.[3] In addition to seamounts, there are more than 80,000 small knolls, ridges and hills less than 1,000 m in height in the world's oceans.[4]

Most seamounts are volcanic in origin, and thus tend to be found on oceanic crust near mid-ocean ridges, mantle plumes, and island arcs. Overall, seamount and guyot coverage is greatest as a proportion of seafloor area in the North Pacific Ocean, equal to 4.39% of that ocean region. The Arctic Ocean has only 16 seamounts and no guyots, and the Mediterranean and Black seas together have only 23 seamounts and 2 guyots. The 9,951 seamounts which have been mapped cover an area of 8,088,550 km2 (3,123,010 sq mi). Seamounts have an average area of 790 km2 (310 sq mi), with the smallest seamounts found in the Arctic Ocean and the Mediterranean and Black Seas; whilst the largest mean seamount size, 890 km2 (340 sq mi), occurs in the Indian Ocean. The largest seamount has an area of 15,500 km2 (6,000 sq mi) and it occurs in the North Pacific. Guyots cover a total area of 707,600 km2 (273,200 sq mi) and have an average area of 2,500 km2 (970 sq mi), more than twice the average size of seamounts. Nearly 50% of guyot area and 42% of the number of guyots occur in the North Pacific Ocean, covering 342,070 km2 (132,070 sq mi). The largest three guyots are all in the North Pacific: the Kuko Guyot (estimated 24,600 km2 (9,500 sq mi)), Suiko Guyot (estimated 20,220 km2 (7,810 sq mi)) and the Pallada Guyot (estimated 13,680 km2 (5,280 sq mi)).[4]

Grouping

[edit]Seamounts are often found in groupings or submerged archipelagos, a classic example being the Emperor Seamounts, an extension of the Hawaiian Islands. Formed millions of years ago by volcanism, they have since subsided far below sea level. This long chain of islands and seamounts extends thousands of kilometers northwest from the island of Hawaii.

There are more seamounts in the Pacific Ocean than in the Atlantic, and their distribution can be described as comprising several elongate chains of seamounts superimposed on a more or less random background distribution.[6] Seamount chains occur in all three major ocean basins, with the Pacific having the most number and most extensive seamount chains. These include the Hawaiian (Emperor), Mariana, Gilbert, Tuomotu and Austral Seamounts (and island groups) in the north Pacific and the Louisville and Sala y Gomez ridges in the southern Pacific Ocean. In the North Atlantic Ocean, the New England Seamounts extend from the eastern coast of the United States to the mid-ocean ridge. Craig and Sandwell[6] noted that clusters of larger Atlantic seamounts tend to be associated with other evidence of hotspot activity, such as on the Walvis Ridge, Vitória-Trindade Ridge, Bermuda Islands and Cape Verde Islands. The mid-Atlantic ridge and spreading ridges in the Indian Ocean are also associated with abundant seamounts.[7] Otherwise, seamounts tend not to form distinctive chains in the Indian and Southern Oceans, but rather their distribution appears to be more or less random.

Isolated seamounts and those without clear volcanic origins are less common; examples include Bollons Seamount, Eratosthenes Seamount, Axial Seamount and Gorringe Ridge.[8]

If all known seamounts were collected into one area, they would make a landform the size of Europe.[9] Their overall abundance makes them one of the most common, and least understood, marine structures and biomes on Earth,[10] a sort of exploratory frontier.[11]

Geology

[edit]Geochemistry and evolution

[edit]

Most seamounts are built by one of two volcanic processes, although some, such as the Christmas Island Seamount Province near Australia, are more enigmatic.[12] Volcanoes near plate boundaries and mid-ocean ridges are built by decompression melting of rock in the upper mantle. The lower density magma rises through the crust to the surface. Volcanoes formed near or above subducting zones are created because the subducting tectonic plate adds volatiles to the overriding plate that lowers its melting point. Which of these two process involved in the formation of a seamount has a profound effect on its eruptive materials. Lava flows from mid-ocean ridge and plate boundary seamounts are mostly basaltic (both tholeiitic and alkalic), whereas flows from subducting ridge volcanoes are mostly calc-alkaline lavas. Compared to mid-ocean ridge seamounts, subduction zone seamounts generally have more sodium, alkali, and volatile abundances, and less magnesium, resulting in more explosive, viscous eruptions.[11]

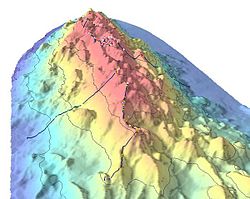

All volcanic seamounts follow a particular pattern of growth, activity, subsidence and eventual extinction. The first stage of a seamount's evolution is its early activity, building its flanks and core up from the sea floor. This is followed by a period of intense volcanism, during which the new volcano erupts almost all (e.g. 98%) of its total magmatic volume. The seamount may even grow above sea level to become an oceanic island (for example, the 2009 eruption of Hunga Tonga). After a period of explosive activity near the ocean surface, the eruptions slowly die away. With eruptions becoming infrequent and the seamount losing its ability to maintain itself, the volcano starts to erode. After finally becoming extinct (possibly after a brief rejuvenated period), they are ground back down by the waves. Seamounts are built in a far more dynamic oceanic setting than their land counterparts, resulting in horizontal subsidence as the seamount moves with the tectonic plate towards a subduction zone. Here it is subducted under the plate margin and ultimately destroyed, but it may leave evidence of its passage by carving an indentation into the opposing wall of the subduction trench. The majority of seamounts have already completed their eruptive cycle, so access to early flows by researchers is limited by late volcanic activity.[11]

Ocean-ridge volcanoes in particular have been observed to follow a certain pattern in terms of eruptive activity, first observed with Hawaiian seamounts but now shown to be the process followed by all seamounts of the ocean-ridge type. During the first stage the volcano erupts basalt of various types, caused by various degrees of mantle melting. In the second, most active stage of its life, ocean-ridge volcanoes erupt tholeiitic to mildly alkalic basalt as a result of a larger area melting in the mantle. This is finally capped by alkalic flows late in its eruptive history, as the link between the seamount and its source of volcanism is cut by crustal movement. Some seamounts also experience a brief "rejuvenated" period after a hiatus of 1.5 to 10 million years, the flows of which are highly alkalic and produce many xenoliths.[11]

In recent years, geologists have confirmed that a number of seamounts are active undersea volcanoes; two examples are Kamaʻehuakanaloa (formerly Lo'ihi) in the Hawaiian Islands and Vailulu'u in the Manu'a Group (Samoa).[8]

Lava types

[edit]

The most apparent lava flows at a seamount are the eruptive flows that cover their flanks, however igneous intrusions, in the forms of dikes and sills, are also an important part of seamount growth. The most common type of flow is pillow lava, named so after its distinctive shape. Less common are sheet flows, which are glassy and marginal, and indicative of larger-scale flows. Volcaniclastic sedimentary rocks dominate shallow-water seamounts. They are the products of the explosive activity of seamounts that are near the water's surface, and can also form from mechanical wear of existing volcanic rock.[11]

Structure

[edit]Seamounts can form in a wide variety of tectonic settings, resulting in a very diverse structural bank. Seamounts come in a wide variety of structural shapes, from conical to flat-topped to complexly shaped.[11] Some are built very large and very low, such as Koko Guyot[14] and Detroit Seamount;[15] others are built more steeply, such as Kamaʻehuakanaloa Seamount[16] and Bowie Seamount.[17] Some seamounts also have a carbonate or sediment cap.[11]

Many seamounts show signs of intrusive activity, which is likely to lead to inflation, steepening of volcanic slopes, and ultimately, flank collapse.[11] There are also several sub-classes of seamounts. The first are guyots, seamounts with a flat top. These tops must be 200 m (656 ft) or more below the surface of the sea; the diameters of these flat summits can be over 10 km (6.2 mi).[18] Knolls are isolated elevation spikes measuring less than 1,000 meters (3,281 ft).[clarification needed] Lastly, pinnacles are small pillar-like seamounts.[5]

Ecology

[edit]Ecological role of seamounts

[edit]

Seamounts are exceptionally important to their biome ecologically, but their role in their environment is poorly understood. Because they project out above the surrounding sea floor, they disturb standard water flow, causing eddies and associated hydrological phenomena that ultimately result in water movement in an otherwise still ocean bottom. Currents have been measured at up to 0.9 knots, or 48 centimeters per second. Because of this upwelling seamounts often carry above-average plankton populations, seamounts are thus centers where the fish that feed on them aggregate, in turn falling prey to further predation, making seamounts important biological hotspots.[5]

Seamounts provide habitats and spawning grounds for these larger animals, including numerous fish. Some species, including black oreo (Allocyttus niger) and blackstripe cardinalfish (Apogon nigrofasciatus), have been shown to occur more often on seamounts than anywhere else on the ocean floor. Marine mammals, sharks, tuna, and cephalopods all congregate over seamounts to feed, as well as some species of seabirds when the features are particularly shallow.[5]

Seamounts often project upwards into shallower zones more hospitable to sea life, providing habitats for marine species that are not found on or around the surrounding deeper ocean bottom. Because seamounts are isolated from each other they form "undersea islands" creating the same biogeographical interest. As they are formed from volcanic rock, the substrate is much harder than the surrounding sedimentary deep sea floor. This causes a different type of fauna to exist than on the seafloor, and leads to a theoretically higher degree of endemism.[20] However, recent research especially centered at Davidson Seamount suggests that seamounts may not be especially endemic, and discussions are ongoing on the effect of seamounts on endemicity. They have, however, been confidently shown to provide a habitat to species that have difficulty surviving elsewhere.[21][22]

The volcanic rocks on the slopes of seamounts are heavily populated by suspension feeders, particularly corals, which capitalize on the strong currents around the seamount to supply them with food. These coral are therefore host to numerous other organisms in a commensal relationship, for example brittle stars, who climb the coral to get themselves off the seafloor, helping them to catch food particles, or small zooplankton, as they drift by.[23] This is in sharp contrast with the typical deep-sea habitat, where deposit-feeding animals rely on food they get off the ground.[5] In tropical zones extensive coral growth results in the formation of coral atolls late in the seamount's life.[22][24]

In addition soft sediments tend to accumulate on seamounts, which are typically populated by polychaetes (annelid marine worms) oligochaetes (microdrile worms), and gastropod mollusks (sea slugs). Xenophyophores have also been found. They tend to gather small particulates and thus form beds, which alters sediment deposition and creates a habitat for smaller animals.[5] Many seamounts also have hydrothermal vent communities, for example Suiyo[25] and Kamaʻehuakanaloa seamounts.[26] This is helped by geochemical exchange between the seamounts and the ocean water.[11]

Seamounts may thus be vital stopping points for some migratory animals, specifically whales. Some recent research indicates whales may use such features as navigational aids throughout their migration.[27] For a long time it has been surmised that many pelagic animals visit seamounts as well, to gather food, but proof of this aggregating effect has been lacking. The first demonstration of this conjecture was published in 2008.[28]

Fishing

[edit]The effect that seamounts have on fish populations has not gone unnoticed by the commercial fishing industry. Seamounts were first extensively fished in the second half of the 20th century, due to poor management practices and increased fishing pressure seriously depleting stock numbers on the typical fishing ground, the continental shelf. Seamounts have been the site of targeted fishing since that time.[29]

Nearly 80 species of fish and shellfish are commercially harvested from seamounts, including spiny lobster (Palinuridae), mackerel (Scombridae and others), red king crab (Paralithodes camtschaticus), red snapper (Lutjanus campechanus), tuna (Scombridae), Orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus), and perch (Percidae).[5]

Conservation

[edit]

The ecological conservation of seamounts is hurt by the simple lack of information available. Seamounts are very poorly studied, with only 350 of the estimated 100,000 seamounts in the world having received sampling, and fewer than 100 in depth.[30] Much of this lack of information can be attributed to a lack of technology,[clarification needed] and to the daunting task of reaching these underwater structures; the technology to fully explore them has only been around the last few decades. Before consistent conservation efforts can begin, the seamounts of the world must first be mapped, a task that is still in progress.[5]

Overfishing is a serious threat to seamount ecological welfare. There are several well-documented cases of fishery exploitation, for example the orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus) off the coasts of Australia and New Zealand and the pelagic armorhead (Pseudopentaceros richardsoni) near Japan and Russia.[5] The reason for this is that the fishes that are targeted over seamounts are typically long-lived, slow-growing, and slow-maturing. The problem is confounded by the dangers of trawling, which damages seamount surface communities, and the fact that many seamounts are located in international waters, making proper monitoring difficult.[29] Bottom trawling in particular is extremely devastating to seamount ecology, and is responsible for as much as 95% of ecological damage to seamounts.[31]

Corals from seamounts are also vulnerable, as they are highly valued for making jewellery and decorative objects. Significant harvests have been produced from seamounts, often leaving coral beds depleted.[5]

Individual nations are beginning to note the effect of fishing on seamounts, and the European Commission has agreed to fund the OASIS project, a detailed study of the effects of fishing on seamount communities in the North Atlantic.[29] Another project working towards conservation is CenSeam, a Census of Marine Life project formed in 2005. CenSeam is intended to provide the framework needed to prioritise, integrate, expand and facilitate seamount research efforts in order to significantly reduce the unknown and build towards a global understanding of seamount ecosystems, and the roles they have in the biogeography, biodiversity, productivity and evolution of marine organisms.[30][32]

Possibly the best ecologically studied seamount in the world is Davidson Seamount, with six major expeditions recording over 60,000 species observations. The contrast between the seamount and the surrounding area was well-marked.[21] One of the primary ecological havens on the seamount is its deep sea coral garden, and many of the specimens noted were over a century old.[19] Following the expansion of knowledge on the seamount there was extensive support to make it a marine sanctuary, a motion that was granted in 2008 as part of the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary.[33] Much of what is known about seamounts ecologically is based on observations from Davidson.[19][28] Another such seamount is Bowie Seamount, which has also been declared a marine protected area by Canada for its ecological richness.[34]

Exploration

[edit]

The study of seamounts has been hindered for a long time by the lack of technology. Although seamounts have been sampled as far back as the 19th century, their depth and position meant that the technology to explore and sample seamounts in sufficient detail did not exist until the last few decades. Even with the right technology available,[clarification needed] only a scant 1% of the total number have been explored,[9] and sampling and information remains biased towards the top 500 m (1,640 ft).[5] New species are observed or collected and valuable information is obtained on almost every submersible dive at seamounts.[10]

Before seamounts and their oceanographic impact can be fully understood, they must be mapped, a daunting task due to their sheer number.[5] The most detailed seamount mappings are provided by multibeam echosounding (sonar), however after more than 5000 publicly held cruises, the amount of the sea floor that has been mapped remains minuscule. Satellite altimetry is a broader alternative, albeit not as detailed, with 13,000 catalogued seamounts; however this is still only a fraction of the total 100,000. The reason for this is that uncertainties in the technology limit recognition to features 1,500 m (4,921 ft) or larger. In the future, technological advances could allow for a larger and more detailed catalogue.[24]

Observations from CryoSat-2 combined with data from other satellites has shown thousands of previously uncharted seamounts, with more to come as data is interpreted.[35][36][37][38]

Deep-sea mining

[edit]Seamounts are a possible future source of economically important metals. Even though the ocean makes up 70% of Earth's surface area, technological challenges have severely limited the extent of deep sea mining. But with the constantly decreasing supply on land, some mining specialists see oceanic mining as the destined future, and seamounts stand out as candidates.[39]

Seamounts are abundant, and all have metal resource potential because of various enrichment processes during the seamount's life. An example for epithermal gold mineralization on the seafloor is Conical Seamount, located about 8 km south of Lihir Island in Papua New Guinea. Conical Seamount has a basal diameter of about 2.8 km and rises about 600 m above the seafloor to a water depth of 1050 m. Grab samples from its summit contain the highest gold concentrations yet reported from the modern seafloor (max. 230 g/t Au, avg. 26 g/t, n=40).[40] Iron-manganese, hydrothermal iron oxide, sulfide, sulfate, sulfur, hydrothermal manganese oxide, and phosphorite[41] (the latter especially in parts of Micronesia) are all mineral resources that are deposited upon or within seamounts. However, only the first two have any potential of being targeted by mining in the next few decades.[39]

Dangers

[edit]

Some seamounts have not been mapped and thus pose a navigational danger. For instance, Muirfield Seamount is named after the ship that hit it in 1973.[43] More recently, the submarine USS San Francisco ran into an uncharted seamount in 2005 at a speed of 35 knots (40.3 mph; 64.8 km/h), sustaining serious damage and killing one seaman.[42]

One major seamount risk is that often, in the late of stages of their life, extrusions begin to seep in the seamount. This activity leads to inflation, over-extension of the volcano's flanks, and ultimately flank collapse, leading to submarine landslides with the potential to start major tsunamis, which can be among the largest natural disasters in the world. In an illustration of the potent power of flank collapses, a summit collapse on the northern edge of Vlinder Seamount resulted in a pronounced headwall scarp and a field of debris up to 6 km (4 mi) away.[11] A catastrophic collapse at Detroit Seamount flattened its whole structure extensively.[15] Lastly, in 2004, scientists found marine fossils 61 m (200 ft) up the flank of Kohala mountain in Hawaii. Subsidation analysis found that at the time of their deposition, this would have been 500 m (1,640 ft) up the flank of the volcano,[44] far too high for a normal wave to reach. The date corresponded with a massive flank collapse at the nearby Mauna Loa, and it was theorized that it was a massive tsunami, generated by the landslide, that deposited the fossils.[45]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c IHO, 2008. Standardization of Undersea Feature Names: Guidelines Proposal form Terminology, 4th ed. International Hydrographic Organization and Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission, Monaco.

- ^ Nybakken, James W. and Bertness, Mark D., 2008. Marine Biology: An Ecological Approach. Sixth Edition. Benjamin Cummings, San Francisco

- ^ a b Watts, T. (August 2019). "Science, Seamounts and Society". Geoscientist: 10–16.

- ^ a b c Harris, P. T.; MacMillan-Lawler, M.; Rupp, J.; Baker, E. K. (2014). "Geomorphology of the oceans". Marine Geology. 352: 4–24. Bibcode:2014MGeol.352....4H. doi:10.1016/j.margeo.2014.01.011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Seamount". Encyclopedia of Earth. December 9, 2008. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ^ a b Craig, C.H.; Sandwell, D.T. (1988). "Global distribution of seamounts from Seasat profiles". Journal of Geophysical Research. 93 (B9): 10408–410, 420. Bibcode:1988JGR....9310408C. doi:10.1029/jb093ib09p10408.

- ^ Kitchingman, A., Lai, S., 2004. Inferences on Potential Seamount Locations from Mid-Resolution Bathymetric Data. in: Morato, T., Pauly, D. (Eds.), FCRR Seamounts: Biodiversity and Fisheries. Fisheries Centre Research Reports. University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, pages 7–12.

- ^ a b Keating, Barbara H.; Fryer, Patricia; Batiza, Rodey; Boehlert, George W. (1987). Seamounts, Islands, and Atolls. Geophysical Monograph Series. Vol. 43. Bibcode:1987GMS....43.....K. doi:10.1029/GM043. ISBN 978-1-118-66420-9.[page needed]

- ^ a b "Seamount scientists offer new comprehensive view of deep-sea mountains". ScienceDaily (Press release). Scripps Institution of Oceanography / UC San Diego. 23 February 2010.

- ^ a b "Seamounts identified as significant, unexplored territory". ScienceDaily (Press release). National Oceanic And Atmospheric Administration. 30 April 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hubert Straudigal & David A Clauge. "The Geological History of Deep-Sea Volcanoes: Biosphere, Hydrosphere, and Lithosphere Interactions" (PDF). Oceanography. Seamounts Special Issue. 32 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2010. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ^ K. Hoernle; F. Hauff; R. Werner; P. van den Bogaard; A. D. Gibbons; S. Conrad & R. D. Müller (27 November 2011). "Origin of Indian Ocean Seamount Province by shallow recycling of continental lithosphere". Nature Geoscience. 4 (12): 883–887. Bibcode:2011NatGe...4..883H. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.656.2778. doi:10.1038/ngeo1331.

- ^ "Pillow lava". NOAA. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ^ "SITE 1206". Ocean Drilling Program Database-Results of Site 1206. Ocean Drilling Program. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ a b Kerr, B. C.; D. W. Scholl; S. L. Klemperer (July 12, 2005). "Seismic stratigraphy of Detroit Seamount, Hawaiian–Emperor Seamount chain" (PDF). Stanford University. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ Rubin, Ken (January 19, 2006). "General Information About Loihi". Hawaii Center for Volcanology. School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ "The Bowie Seamount Area" (PDF). John F. Dower and Frances J. Fee. February 1999. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ "Guyots". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ^ a b c "Seamounts may serve as refuges for deep-sea animals that struggle to survive elsewhere". PhysOrg. February 11, 2009. Retrieved December 7, 2009.

- ^ "Davidson Seamount" (PDF). NOAA, Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. 2006. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ^ a b McClain, Craig R.; Lundsten L.; Ream M., Barry J.; DeVogelaere A. (January 7, 2009). Rands, Sean (ed.). "Endemicity, Biogeography, Composition, and Community Structure On a Northeast Pacific Seamount". PLoS ONE. 4 (1) e4141. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.4141M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004141. PMC 2613552. PMID 19127302.

- ^ a b Lundsten, L; J. P. Barry; G. M. Cailliet; D. A. Clague; A. DeVogelaere; J. B. Geller (January 13, 2009). "Benthic invertebrate communities on three seamounts off southern and central California". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 374: 23–32. Bibcode:2009MEPS..374...23L. doi:10.3354/meps07745.

- ^ "NOAA Ocean Explorer: Mountains in the Sea 2004".

- ^ a b Wessel, Paul; Sandwell, David T.; Kim, Seung-Sep (2010). "The Global Seamount Census". Oceanography. 23 (1): 24–33. Bibcode:2010Ocgpy..23...24W. doi:10.5670/oceanog.2010.60. JSTOR 24861056.

- ^ Higashi, Y; et al. (2004). "Microbial diversity in hydrothermal surface to subsurface environments of Suiyo Seamount, Izu-Bonin Arc, using a catheter-type in situ growth chamber". FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 47 (3): 327–336. Bibcode:2004FEMME..47..327H. doi:10.1016/S0168-6496(04)00004-2. PMID 19712321.

- ^ "Introduction to the Biology and Geology of Lōʻihi Seamount". Lōʻihi Seamount. Fe-Oxidizing Microbial Observatory (FeMO). 2009-02-01. Retrieved 2009-03-02.

- ^ Kennedy, Jennifer. "Seamount: What is a Seamount?". ask.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2010. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ^ a b Morato, T., Varkey, D.A., Damaso, C., Machete, M., Santos, M., Prieto, R., Santos, R.S. and Pitcher, T.J. (2008). "Evidence of a seamount effect on aggregating visitors". Marine Ecology Progress Series 357: pages 23–32.

- ^ a b c d "Seamounts – hotspots of marine life". International Council for the Exploration of the Sea. Archived from the original on 13 April 2010. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ^ a b "CenSeam Mission". CenSeam. Archived from the original on 24 May 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ^ Report of the Secretary-General (2006) The Impacts of Fishing on Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems United Nations. 14 July 2006. Retrieved on 26 July 2010.

- ^ "CenSeam Science". CenSeam. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ^ "NOAA Releases Plans for Managing and Protecting Cordell Bank, Gulf of Farallones and Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuaries" (PDF). Press release. NOAA. November 20, 2008. Retrieved 2 December 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Bowie Seamount Marine Protected Area". Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 1 October 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan. "Satellites detect 'thousands' of new ocean-bottom mountains" BBC News, 2 October 2014.

- ^ "New Map Exposes Previously Unseen Details of Seafloor"

- ^ Sandwell, David T.; Müller, R. Dietmar; Smith, Walter H. F.; Garcia, Emmanuel; Francis, Richard (2014). "New global marine gravity model from CryoSat-2 and Jason-1 reveals buried tectonic structure". Science. 346 (6205): 65–67. Bibcode:2014Sci...346...65S. doi:10.1126/science.1258213. PMID 25278606. S2CID 31851740.

- ^ "Cryosat 4 Plus" DTU Space

- ^ a b James R. Hein; Tracy A. Conrad; Hubert Staudigel. "Seamount Mineral Deposits: A Source for Rare Minerals for High Technology Industries" (PDF). Oceanography. Seamounts Special Issue. 23 (1). ISSN 1042-8275. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2010. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ Muller, Daniel; Leander Franz; Sven Petersen; Peter Herzig; Mark Hannington (2003). "Comparison between magmatic activity and gold mineralization at Conical Seamount and Lihir Island, Papua New Guinea". Mineralogy and Petrology. 79 (3–4): 259–283. Bibcode:2003MinPe..79..259M. doi:10.1007/s00710-003-0007-3. S2CID 129643758.

- ^ C.Michael Hogan. 2011. Phosphate. Encyclopedia of Earth. Topic ed. Andy Jorgensen. Ed.-in-Chief C.J.Cleveland. National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington DC

- ^ a b "USS San Francisco (SSN 711)". Archived from the original on 25 September 2009. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ^ Nigel Calder (2002). How to Read a Navigational Chart: A Complete Guide to the Symbols, Abbreviations, and Data Displayed on Nautical Charts. International Marine/Ragged Mountain Press.

- ^ Seach, John. "Kohala Volcano". Volcanism reference base. John Seach, vulcanologist. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ^ "Hawaiian tsunami left a gift at foot of volcano". New Scientist (2464): 14. 2004-09-11. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

Bibliography

[edit]Geology

- Keating, B.H., Fryer, P., Batiza, R., Boehlert, G.W. (Eds.), 1987: Seamounts, islands and atolls. Geophys. Monogr. 43:319–334.

- Menard, H.W. (1964). Marine Geology of the Pacific. International Series in the Earth Sciences. McGraw-Hill, New York, 271 pp.

Ecology

- Clark, M. R.; Rowden, A. A.; Schlacher, T.; Williams, A.; Consalvey, M.; Stocks, K. I.; Rogers, A. D.; O'Hara, T. D.; White, M.; Shank, T. M.; Hall-Spencer, J. M. (2010). "The Ecology of Seamounts: Structure, Function, and Human Impacts". Annual Review of Marine Science. 2: 253–278. Bibcode:2010ARMS....2..253C. doi:10.1146/annurev-marine-120308-081109. hdl:10026.1/1339. PMID 21141665.

- Richer de Forges; J. Anthony Koslow & G. C. B. Poore (22 June 2000). "Diversity and endemism of the benthic seamount fauna in the southwest Pacific". Nature. 405 (6789): 944–947. Bibcode:2000Natur.405..944R. doi:10.1038/35016066. PMID 10879534. S2CID 4382477.

- Koslow, J.A. (1997). "Seamounts and the ecology of deep-sea fisheries". Am. Sci. 85 (2): 168–176. Bibcode:1997AmSci..85..168K.

- Lundsten, L; McClain, CR; Barry, JP; Cailliet, GM; Clague, DA; DeVogelaere, AP (2009). "Ichthyofauna on Three Seamounts off Southern and Central California, USA". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 389: 223–232. Bibcode:2009MEPS..389..223L. doi:10.3354/meps08181.

- Pitcher, T.J., Morato, T., Hart, P.J.B., Clark, M.R., Haggan, N. and Santos, R.S. (eds) (2007). "Seamounts: Ecology, Fisheries and Conservation". Fish and Aquatic Resources Series 12, Blackwell, Oxford, UK. 527pp. ISBN 978-1-4051-3343-2

External links

[edit]Geography and geology

- Earthref Seamount Catalogue. A database of seamount maps and catalogue listings.

- Volcanic History of Seamounts in the Gulf of Alaska.

- The giant Ruatoria debris avalanche on the northern Hikurangi margin, New Zealand Archived 2010-07-16 at the Wayback Machine. Aftermath of a seamount carving into the far side of a subduction trench.

- Evolution of Hawaiian volcanoes. The life cycle of seamounts was originally observed off of the Hawaiian arc.

- How Volcanoes Work: Lava and Water. An explanation of the different types of lava-water interactions.

Ecology

- A review of the effects of seamounts on biological processes.[dead link] NOAA paper.

- Mountains in the Sea, a volume on the biological and geological effects of seamounts, available fully online.

- SeamountsOnline, seamount biology database.

- Vulnerability of deep sea corals to fishing on seamounts beyond areas of national jurisdiction Archived 2007-06-27 at the Wayback Machine, United Nations Environment Program.