Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

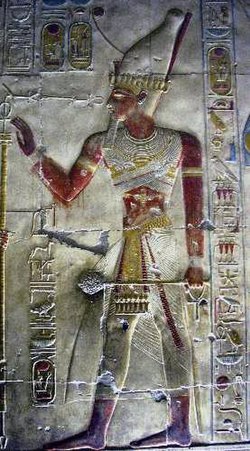

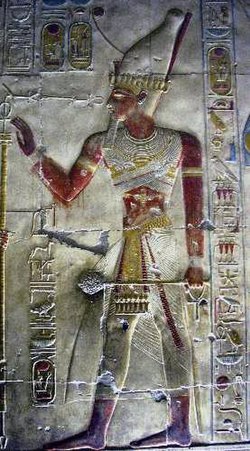

Seti I

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2024) |

Menmaatre Seti I (or Sethos I in Greek) was the second pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt during the New Kingdom period, ruling c. 1294 or 1290 BC to 1279 BC.[4][5] He was the son of Ramesses I and Sitre, and the father of Ramesses II (commonly known as Ramesses the Great).

Key Information

The name 'Seti' means "of Set", which indicates that he was consecrated to the god Set (also termed "Sutekh" or "Seth"). As with most pharaohs, Seti had several names. Upon his ascension, he took the prenomen "mn-m3't-r' ", usually vocalized in Egyptian as Menmaatre (Established is the Justice of Re).[3] His better known nomen, or birth name, is transliterated as "sty mry-n-ptḥ" or Sety Merenptah, meaning "Man of Set, beloved of Ptah". Manetho incorrectly considered him to be the founder of the 19th Dynasty, and gave him a reign length of 55 years, though no evidence has ever been found for so long a reign.

Reign

[edit]Background

[edit]After the enormous social upheavals generated by Akhenaten's religious reform, Horemheb, Ramesses I and Seti I's main priority was to re-establish order in the kingdom and to reaffirm Egypt's sovereignty over Canaan and Syria, which had been compromised by the increasing external pressures from the Hittite state. Seti, with energy and determination, confronted the Hittites several times in battle. Without succeeding in destroying the Hittites as a potential danger to Egypt, he reconquered most of the disputed territories for Egypt and generally concluded his military campaigns with victories. The memory of Seti I's military successes was recorded in some large scenes placed on the front of the temple of Amun, situated in Karnak. A funerary temple for Seti was constructed in what is now known as Qurna (Mortuary Temple of Seti I), on the west bank of the Nile at Thebes while a magnificent temple made of white limestone at Abydos featuring exquisite relief scenes was started by Seti, and later completed by his son. His capital was at Memphis. He was considered a great king by his peers, but his fame has been overshadowed since ancient times by that of his son, Ramesses II.

Reign Length

[edit]

Seti I's accession date is known to be III Shemu day 24.[6] Seti I's reign length was either 9 or 11 rather than 15 full years. Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen has estimated that it was 15 years, but there are no dates recorded for Seti I after his Year 11 Gebel Barkal stela. As this king is otherwise quite well documented in historical records, other scholars suggest that a continuous break in the record for his last four years is unlikely, although it is technically possible simply that no records have yet been discovered.

Peter J. Brand noted that the king personally opened new rock quarries at Aswan to build obelisks and colossal statues in his Year 9.[7] This event is commemorated on two rock stelas in Aswan. However, most of Seti's obelisks and statues such as the Flaminian and Luxor obelisks were only partly finished or decorated by the time of his death, since they were completed early under his son's reign based on epigraphic evidence (they bore the early form of Ramesses II's royal prenomen "Usermaatre"). Ramesses II used the prenomen Usermaatre to refer to himself in his first year and did not adopt the final form of his royal title "Usermaatre Setepenre" until late into his second year.[8]

Brand aptly notes that this evidence calls into question the idea of a 15 Year reign for Seti I and suggests that "Seti died after a ten to eleven year reign" because only two years would have passed between the opening of the Rock Quarries and the partial completion and decoration of these monuments.[9] This explanation conforms better with the evidence of the unfinished state of Seti I's monuments and the fact that Ramesses II had to complete the decorations on "many of his father's unfinished monuments, including the southern half of the Great Hypostyle Hall at Karnak and portions of his father's temples at Gurnah and Abydos" during the very first Year of his own reign.[10] Critically, Brand notes that the larger of the two Aswan rock stelas states that Seti I "has ordered the commissioning of multitudinous works for the making of very great obelisks and great and wondrous statues (i.e. colossi) in the name of His Majesty, L.P.H. He made great barges for transporting them, and ships crews to match them for ferrying them from the quarry." (KRI 74:12-14)[11] However, despite this promise, Brand stresses that

There are few obelisks and apparently no colossi inscribed for Seti. Ramesses II, however, was able to complete the two obelisks and four seated colossi from Luxor within the first years of his reign, the two obelisks in particular being partly inscribed before he adopted the final form of his prenomen sometime in [his] year two. This state of affairs strongly implies that Seti died after ten to eleven years. Had he [Seti I] ruled on until his fourteenth or fifteenth year, then surely more of the obelisks and colossi he commissioned in [his] year nine would have been completed, in particular those from Luxor. If he in fact died after little more than a decade on the throne, however, then at most two years would have elapsed since the Aswan quarries were opened in year nine, and only a fraction of the great monoliths would have been complete and inscribed at his death, with others just emerging from the quarries so that Ramesses would be able to decorate them shortly after his accession. ... It now seems clear that a long, fourteen-to fifteen-year reign for Seti I can be rejected for lack of evidence. Rather, a tenure of ten or more likely probably eleven, years appears the most likely scenario.[12]

The German Egyptologist Jürgen von Beckerath also accepts that Seti I's reign lasted only 11 Years in a 1997 book.[13] Seti's highest known date is Year 11, IV Shemu day 12 or 13 on a sandstone stela from Gebel Barkal[12] but he would have briefly survived for 2 to 3 days into his Year 12 before dying based on the date of Ramesses II's rise to power. Seti I's accession date has been determined by Wolfgang Helck to be III Shemu day 24, which is very close to Ramesses II's known accession date of III Shemu day 27.[14]

More recently, in 2011, the Dutch Egyptologist Jacobus Van Dijk questioned the "Year 11" date stated in the great temple of Amun on the Gebel Barkal stela—Seti I's previously known highest attested date.[15] This monument is quite badly preserved but still depicts Seti I in erect posture, which is the only case occurring since his Year 4 when he started to be depicted in a stooping posture on his stelae. Furthermore, the glyphs "I ∩" representing the 11 are damaged in the upper part and may just as well be "I I I" instead. Subsequently, Van Dijk proposed that the Gebel Barkal stela should be dated to Year 3 of Seti I, and that Seti's highest date more likely is Year 9 as suggested by the wine jars found in his tomb.[16] In a 2012 paper, David Aston analyzed the wine jars and came to the same conclusion since no wine labels higher than Seti I's 8th regnal year were found in his KV17 tomb.[17]

Military campaigns

[edit]This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (September 2024) |

Seti I fought a series of wars in western Asia, Libya and Nubia in the first decade of his reign. The main source for Seti's military activities are his battle scenes on the north exterior wall of the Karnak Hypostyle Hall, along with several royal stelas with inscriptions mentioning battles in Canaan and Nubia.

In his first regnal year, he led his armies along the "Horus Military road", the coastal road that led from the Egyptian city of Tjaru (Zarw/Sile) in the northeast corner of the Egyptian Nile Delta along the northern coast of the Sinai peninsula ending in the town of "Canaan" in the modern Gaza strip. The Ways of Horus consisted of a series of military forts, each with a well, that are depicted in detail in the king's war scenes on the north wall of the Karnak Hypostyle Hall. While crossing the Sinai, the king's army fought local Bedouins called the Shasu. In Canaan, he received the tribute of some of the city states he visited. Others, including Beth-Shan and Yenoam, had to be captured but were easily defeated. A stele in Beth-Shan testifies to that reconquest; according to Grdsseloff, Rowe, Albrecht et Albright,[18] Seti defeated Asian nomads in war against the Apirus (Hebrews). Dussaud commented Albright's article: "The interest of Professor Albright's note is mainly due to the fact that he no longer objects to the identification of "Apiru" with "Ibri" (i.e. the Hebrews) provided that we grant him that the vocal change has been driven by a popular etymology that brought the term "eber" (formerly 'ibr), that is to say the man from beyond the river."[19] It seems that Egypt extends beyond the river. The attack on Yenoam is illustrated in his war scenes, while other battles, such as the defeat of Beth-Shan, were not shown because the king himself did not participate, sending a division of his army instead. The year one campaign continued into Lebanon where the king received the submission of its chiefs who were compelled to cut down valuable cedar wood themselves as tribute.

At some unknown point in his reign, Seti I defeated Libyan tribesmen who had invaded Egypt's western border. Although defeated, the Libyans would pose an ever-increasing threat to Egypt during the reigns of Merenptah and Ramesses III. The Egyptian army also put down a minor "rebellion" in Nubia in the 8th year of Seti I. Seti himself did not participate in it although his crown prince, the future Ramesses II, may have.

Capture of Kadesh

[edit]This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (September 2024) |

The greatest achievement of Seti I's foreign policy was the capture of the Syrian town of Kadesh and neighboring territory of Amurru from the Hittite Empire. Egypt had not held Kadesh since the time of Akhenaten. Seti I was successful in defeating a Hittite army that tried to defend the town. He entered the city in triumph together with his son Ramesses II and erected a victory stela at the site which has been found by archaeologists.[20] Kadesh, however, soon reverted to Hittite control because the Egyptians did not or could not maintain a permanent military occupation of Kadesh and Amurru so close to the Hittite homelands. It is unlikely that Seti I made a peace treaty with the Hittites or voluntarily returned Kadesh and Amurru, but he may have reached an informal understanding with the Hittite king Muwatalli on the precise boundaries of their empires. Five years after Seti I's death, however, his son Ramesses II resumed hostilities and made a failed attempt to recapture Kadesh. Kadesh was henceforth effectively held by the Hittites even though Ramesses temporarily occupied the city in his 8th year.

The traditional view of Seti I's wars was that he restored the Egyptian empire after it had been lost in the time of Akhenaten. This was based on the chaotic picture of Egyptian-controlled Syria and Canaan seen in the Amarna letters, a cache of diplomatic correspondence from the time of Akhenaten found at Akhenaten's capital at el-Amarna in Middle Egypt. Recent scholarship, however, indicates that the empire was not lost at this time, except for its northern border provinces of Kadesh and Amurru in Syria and Lebanon. While evidence for the military activities of Akhenaten, Tutankhamun and Horemheb is fragmentary or ambiguous, Seti I left a war monument that glorifies his achievements, along with a number of texts, all of which tend to magnify his prowess on the battlefield.

Burial

[edit]Mummy

[edit]

From an examination of Seti's extremely well-preserved mummy, Seti I appears to have been less than forty years old when he died unexpectedly. This is in stark contrast to the situation with Horemheb, Ramesses I and Ramesses II who all lived to an advanced age. The reasons for his relatively early death are uncertain, but there is no evidence of violence on his mummy. His mummy was found decapitated, but this was likely caused by tomb robbers after his death. The Amun priest carefully reattached his head to his body with the use of linen cloths. It has been suggested that he died from a disease which had affected him for years, possibly related to his heart. The latter was found placed in the right part of the body, while the usual practice of the day was to place it in the left part during the mummification process. Opinions vary whether this was a mistake or an attempt to have Seti's heart work better in his afterlife. Seti I's mummy is about 1.7 metres (5 feet 7 inches) tall.[21]

In April 2021, his mummy was moved from the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization along with those of 17 other kings and 4 queens in an event termed the Pharaohs' Golden Parade.[22]

Tomb

[edit]

Seti's well-preserved tomb (KV17) was found in 1817 by Giovanni Belzoni, in the Valley of the Kings;[23] it proved to be the longest at 446 feet (136 meters)[24] and deepest of all the New Kingdom royal tombs. It was also the first tomb to feature decorations (including the Book of the Heavenly Cow)[25] on every passageway and chamber with highly refined bas-reliefs and colorful paintings – fragments of which, including a large column depicting Seti I with the goddess Hathor, can be seen in the National Archaeological Museum, Florence. This decorative style set a precedent which was followed in full or in part in the tombs of later New Kingdom kings. Seti's mummy itself was discovered by Émile Brugsch on June 6, 1881, in the Royal Cache (tomb DB320) at Deir el-Bahari and has since been kept at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.[26]

His huge sarcophagus, carved in one piece and intricately decorated on every surface (including the goddess Nut on the interior base), is in Sir John Soane's Museum.[27] Soane bought it for exhibition in his open collection in 1824, when the British Museum refused to pay the £2,000 demanded.[28] On its arrival at the museum, the alabaster was pure white and inlaid with blue copper sulphate. Years of the London climate and pollution have darkened the alabaster to a buff colour and absorbed moisture has caused the hygroscopic inlay material to fall out and disappear completely. A small watercolour nearby records the appearance, as it was.

The tomb also had an entrance to a secret tunnel hidden behind the sarcophagus, which Belzoni's team estimated to be 100 meters (330 feet) long.[29] However, the tunnel was not truly excavated until 1961, when a team led by Sheikh Ali Abdel-Rasoul began digging in hopes of discovering a secret burial chamber containing hidden treasures.[29] The team failed to follow the original passage in their excavations, and had to call a halt due to instabilities in the tunnel;[30] further issues with permits and finances eventually ended Sheikh Ali's dreams of treasure,[29] though they were at least able to establish that the passage was over 30 meters (98 feet) longer than the original estimate. In June 2010, a team from Egypt's Ministry of Antiquities led by Dr. Zahi Hawass completed excavation of the tunnel, which had begun again after the discovery in 2007 of a downward-sloping passage beginning approximately 136 meters (446 feet) into the previously excavated tunnel. After uncovering two separate staircases, they found that the tunnel ran for 174 meters (571 feet) in total; unfortunately, the last step seemed to have been abandoned prior to completion and no secret burial chamber was found.[30]

Alleged co-regency with Ramesses II

[edit]Around Year 9 of his reign, Seti appointed his son Ramesses II as the crown prince and his chosen successor, but the evidence for a coregency between the two kings is likely illusory. Peter J. Brand stresses in his thesis[31] that relief decorations at various temple sites at Karnak, Qurna and Abydos, which associate Ramesses II with Seti I, were actually carved after Seti's death by Ramesses II himself and, hence, cannot be used as source material to support a co-regency between the two monarchs. In addition, the late William Murnane, who first endorsed the theory of a co-regency between Seti I and Ramesses II,[32] later revised his view of the proposed co-regency and rejected the idea that Ramesses II had begun to count his own regnal years while Seti I was still alive.[33] Finally, Kenneth Kitchen rejects the term co-regency to describe the relationship between Seti I and Ramesses II; he describes the earliest phase of Ramesses II's career as a "prince regency" where the young Ramesses enjoyed all the trappings of royalty including the use of a royal titulary and harem but did not count his regnal years until after his father's death.[34] This is due to the fact that the evidence for a co-regency between the two kings is vague and highly ambiguous. Two important inscriptions from the first decade of Ramesses' reign, namely the Abydos Dedicatory Inscription and the Kuban Stela of Ramesses II, consistently give the latter titles associated with those of a crown prince only, namely the "king's eldest son and hereditary prince" or "child-heir" to the throne "along with some military titles."[35]

Hence, no clear evidence supports the hypothesis that Ramesses II was a co-regent under his father. Brand stresses that:

Ramesses' claim that he was crowned king by Seti, even as a child in his arms [in the Dedicatory Inscription], is highly self-serving and open to question although his description of his role as crown prince is more accurate...The most reliable and concrete portion of this statement is the enumeration of Ramesses' titles as eldest king's son and heir apparent, well attested in sources contemporary with Seti's reign.[36]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Sety I Menmaatre (Sethos I) King Sety I". Digital Egypt. UCL. Retrieved 15 February 2007.

- ^ "Ancient Egyptian Royalty". Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- ^ a b Peter Clayton, Chronicle of the Pharaohs, Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1994. p.140

- ^ Michael Rice (1999). Who's Who in Ancient Egypt. Routledge.

- ^ J. von Beckerath (1997). Chronologie des Äegyptischen Pharaonischen (in German). Phillip von Zabern. p. 190.

- ^ Peter J. Brand, The Monuments of Seti I and their Historical Significance: Epigraphic, Historical and Art Historical Analysis pp.301-302 PDF Brill, 2000, pp.301-302

- ^ Peter J. Brand, "The 'Lost' Obelisks and Colossi of Seti I", JARCE, 34 (1997), pp. 101-114

- ^ Brand, "The 'Lost' Obelisks", pp. 106-107

- ^ Brand, "The 'Lost' Obelisks", p. 114

- ^ Brand, "The 'Lost' Obelisks", p.107

- ^ Brand, "The 'Lost' Obelisks", p.104

- ^ a b Peter J. Brand (2000). The Monuments of Seti I: Epigraphic, Historical and Art Historical Analysis. Brill. p. 308.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ von Beckerath, Chronologie, p.190

- ^ Brand, The Monuments of Seti I, pp. 301-302

- ^ J. Van Dijk, The Date of the Gebel Barkal Stela of Seti I PDF, in: in D. Aston, B. Bader, C. Gallorini, P. Nicholson & S. Buckingham (eds), Under the Potter's tree. Studies on Ancient Egypt presented to Janine Bourriau on the Occasion of her 70th Birthday (= Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 204), Uitgeverij Peeters en Departement Oosterse Studies, Leuven - Paris - Walpole, MA 2011, pp.325–332.

- ^ J. van Dijk, "The Date of the Gebel Barkal Stela of Seti I PDF, in D. Aston, B. Bader, C. Gallorini, P. Nicholson & S. Buckingham (eds), Under the Potter's tree. Studies on Ancient Egypt presented to Janine Bourriau on the Occasion of her 70th Birthday (= Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 204), Uitgeverij Peeters en Departement Oosterse Studies, Leuven - Paris - Walpole, MA 2011, pp.325–332.

- ^ D. A. Aston, "Radiocarbon, Wine Jars and New Kingdom Chronology PDF", Ägypten und Levante 22-23 (2012-13), pp. 289–315.

- ^ Albright W. The smaller Beth-Shean stele of Sethos I (1309-1290 B. C.), Bulletin of the American schools of Oriental research, feb 1952, p. 24-32.

- ^ Dussaud R. Syria, Revue d'art oriental et d'archéologie, 1952, 29-3-4, p. 386.

- ^ Brand, P.J. (2000). The Monuments of Seti I. Brill Academic Pub. pp. 120–122.

- ^ Christine Hobson, Exploring the World of the Pharaohs: A Complete Guide to Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson, (1993), p. 97

- ^ Parisse, Emmanuel (5 April 2021). "22 Ancient Pharaohs Have Been Carried Across Cairo in an Epic 'Golden Parade'". ScienceAlert. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ "This pharaoh's painted tomb was missing its mummy". 25 June 2020.

- ^ "Pharaoh Seti I's Tomb Bigger Than Thought". Archived from the original on 20 April 2008. Retrieved 19 April 2008.

- ^ "Legend of the Gods". Kegan Paul. 1912. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ Rohl 1995, pp. 71–73.

- ^ "Egyptian Collection at the Sir John Soane's Museum". Archived from the original on 3 October 2010. Retrieved 15 February 2007.

- ^ "Sir John Soane's museum recreates architect's vision of pharaoh's tomb". TheGuardian.com. 5 November 2017.

- ^ a b c El-Aref, Nevine (29 October 2009). "Secret Tunnels And Ancient Mysteries". Al-Ahram Weekly. No. 970. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ a b Williams, Sean (30 June 2010). "No Secret Burial At End Of Seti I Tunnel". The Independent. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ Peter J. Brand (1998). "Studies on the Historical Implications of Seti I's Monuments" (PDF). The Monuments of Seti I and their Historical Significance (PhD thesis). University of Toronto. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 June 2007. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ William Murnane (1977). Ancient Egyptian Coregencies. Seminal book on the Egyptian coregency system

- ^ W. Murnane (1990). The road to Kadesh: A Historical interpretation of the battle reliefs of King Seti I at Karnak. SAOC. pp. 93 footnote 90.

- ^ K.A. Kitchen, Pharaoh Triumphant: The Life and Times of Ramesses II, King of Egypt, Benben Publication, (1982), pp. 27-30

- ^ Brand, The Monuments of Seti I, pp. 315–316

- ^ Brand, The Monuments of Seti I, p. 316

Bibliography

[edit]- Brand, Peter J. The Monuments of Seti I: Epigraphic, Historical, and Art-Historical Analysis. E. J. Brill, Leiden 2000, ISBN 978-9004117709.

- Epigraphic Survey, The Battle Reliefs of King Sety I. Reliefs and Inscriptions at Karnak vol. 4. (Chicago, 1985).

- Caverley, Amice "The Temple of King Sethos I at Abydos", (London, Chicago, 1933–58), 4 volumes.

- Gaballa, Gaballa A. Narrative in Egyptian Art. (Mainz, 1976)

- Hasel, Michael G., Domination & Resistance: Egyptian Military Activity in the Southern Levant, 1300-1185 BC, (Leiden, 1998). ISBN 90-04-10984-6

- Kitchen, Kenneth, Pharaoh Triumphant: The Life and Times of Ramesses II (Warminster, 1982). ISBN 0-85668-215-2

- Liverani, Mario Three Amarna Essays, Monographs on the Ancient Near East 1/5 (Malibu, 1979).

- Murnane, William J. (1990) The Road to Kadesh, Chicago.

- Rohl, David M. (1995). Pharaohs and Kings: A Biblical Quest (illustrated, reprint ed.). Crown Publishers. ISBN 9780517703151.

- Schulman, Alan R. "Hittites, Helmets & Amarna: Akhenaten's First Hittite War," Akhenaten Temple Project volume II, (Toronto, 1988), 53–79.

- Spalinger, Anthony J. "The Northern Wars of Seti I: An Integrative Study." Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 16 (1979). 29–46.

- Spalinger, Anthony J. "Egyptian-Hittite Relations at the Close of the Amarna Age and Some Notes on Hittite Military Strategy in North Syria," Bulletin of the Egyptological Seminar 1 (1979):55-89.