Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Solar flare

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series of articles about |

| Heliophysics |

|---|

|

A solar flare is a relatively intense, localized emission of electromagnetic radiation in the Sun's atmosphere. Flares occur in active regions and are often, but not always, accompanied by coronal mass ejections, solar particle events, and other eruptive solar phenomena. The occurrence of solar flares varies with the 11-year solar cycle.

Solar flares are thought to occur when stored magnetic energy in the Sun's atmosphere accelerates charged particles in the surrounding plasma. This results in the emission of electromagnetic radiation across the electromagnetic spectrum. The typical time profile of these emissions features three identifiable phases: a precursor phase, an impulsive phase when particle acceleration dominates, a gradual phase in which hot plasma injected into the corona by the flare cools by a combination of radiation and conduction of energy back down to the lower atmosphere, and a currently unexplained EUV late phase [1] that occurs in some flares.

The extreme ultraviolet and X-ray radiation from solar flares is absorbed by the daylight side of Earth's upper atmosphere, in particular the ionosphere, and does not reach the surface. This absorption can temporarily increase the ionization of the ionosphere which may interfere with short-wave radio communication. The prediction of solar flares is an active area of research.

Flares also occur on other stars, where the term stellar flare applies.

Physical description

[edit]

Solar flares are eruptions of electromagnetic radiation originating in the Sun's atmosphere.[2] They affect all layers of the solar atmosphere (photosphere, chromosphere, and corona).[3] The plasma medium is heated to >107 kelvin, while electrons, protons, and heavier ions are accelerated to near the speed of light.[4][5] Flares emit electromagnetic radiation across the electromagnetic spectrum, from radio waves to gamma rays.[3]

Flares occur in active regions, often around sunspots, where intense magnetic fields penetrate the photosphere to link the corona to the solar interior. Flares are powered by the sudden (timescales of minutes to tens of minutes) release of magnetic energy stored in the corona. The same energy releases may also produce coronal mass ejections (CMEs), although the relationship between CMEs and flares is not well understood.[6]

Associated with solar flares are flare sprays.[7] They involve faster ejections of material than eruptive prominences,[8] and reach velocities of 20 to 2,000 kilometres per second.[9]

Cause

[edit]Flares occur when accelerated charged particles, mainly electrons, interact with the plasma medium. Evidence suggests that the phenomenon of magnetic reconnection leads to this extreme acceleration of charged particles.[10] On the Sun, magnetic reconnection may happen on solar arcades—a type of prominence consisting of a series of closely occurring loops following magnetic lines of force.[11] These lines of force quickly reconnect into a lower arcade of loops leaving a helix of magnetic field unconnected to the rest of the arcade. The sudden release of energy in this reconnection is the origin of the particle acceleration. The unconnected magnetic helical field and the material that it contains may violently expand outwards forming a coronal mass ejection.[12] This also explains why solar flares typically erupt from active regions on the Sun where magnetic fields are much stronger. [citation needed]

Although there is a general agreement on the source of a flare's energy, the mechanisms involved are not well understood. It is not clear how the magnetic energy is transformed into the kinetic energy of the particles, nor is it known how some particles can be accelerated to the GeV range (109 electron volt) and beyond. There are also some inconsistencies regarding the total number of accelerated particles, which sometimes seems to be greater than the total number in the coronal loop.[13]

Post-eruption loops and arcades

[edit]

After the eruption of a solar flare, post-eruption loops made of hot plasma begin to form across the neutral line separating regions of opposite magnetic polarity near the flare's source. These loops extend from the photosphere up into the corona and form along the neutral line at increasingly greater distances from the source as time progresses.[15] The existence of these hot loops is thought to be continued by prolonged heating present after the eruption and during the flare's decay stage.[16]

In sufficiently powerful flares, typically of C-class or higher, the loops may combine to form an elongated arch-like structure known as a post-eruption arcade. These structures may last anywhere from multiple hours to multiple days after the initial flare.[15] In some cases, dark sunward-traveling plasma voids known as supra-arcade downflows may form above these arcades.[17]

Frequency

[edit]The frequency of occurrence of solar flares varies with the 11-year solar cycle. It can typically range from several per day during solar maxima to less than one every week during solar minima. Additionally, more powerful flares are less frequent than weaker ones. For example, X10-class (severe) flares occur on average about eight times per cycle, whereas M1-class (minor) flares occur on average about 2,000 times per cycle.[18]

In 1984 Erich Rieger and coworkers discovered an approximately 154-day period in the occurrence of gamma-ray emitting solar flares at least since the solar cycle 19.[19] The period has since been confirmed in most heliophysics data and the interplanetary magnetic field and is commonly known as the Rieger period. The period's resonance harmonics also have been reported from most data types in the heliosphere. [citation needed]

The frequency distributions of various flare phenomena can be characterized by power-law distributions. For example, the peak fluxes of radio, extreme ultraviolet, and hard and soft X-ray emissions; total energies; and flare durations (see § Duration) have been found to follow power-law distributions.[20][21][22][23]: 23–28

Classification

[edit]Soft X-ray

[edit]

The modern classification system for solar flares uses the letters A, B, C, M, or X, according to the peak flux in watts per square metre (W/m2) of soft X-rays with wavelengths 0.1 to 0.8 nanometres (1 to 8 ångströms), as measured by GOES satellites in geosynchronous orbit. [citation needed]

| Classification | Peak flux range (W/m2) |

|---|---|

| A | < 10−7 |

| B | 10−7 – 10−6 |

| C | 10−6 – 10−5 |

| M | 10−5 – 10−4 |

| X | > 10−4 |

The strength of an event within a class is noted by a numerical suffix ranging from 1 up to, but excluding, 10, which is also the factor for that event within the class. Hence, an X2 flare is twice the strength of an X1 flare, an X3 flare is three times as powerful as an X1. M-class flares are a tenth the size of X-class flares with the same numeric suffix.[24] An X2 is four times more powerful than an M5 flare.[25] X-class flares with a peak flux that exceeds 10−3 W/m2 may be noted with a numerical suffix equal to or greater than 10.

This system was originally devised in 1970 and included only the letters C, M, and X. These letters were chosen to avoid confusion with other optical classification systems. The A and B classes were added in the 1990s as instruments became more sensitive to weaker flares. Around the same time, the backronym moderate for M-class flares and extreme for X-class flares began to be used.[26]

Importance

[edit]An earlier classification system, sometimes referred to as the flare importance, was based on H-alpha spectral observations. The scheme uses both the intensity and emitting surface. The classification in intensity is qualitative, referring to the flares as: faint (f), normal (n), or brilliant (b). The emitting surface is measured in terms of millionths of the hemisphere and is described below. (The total hemisphere area AH = 15.5 × 1012 km2.) [citation needed]

| Classification | Corrected area (millionths of hemisphere) |

|---|---|

| S | < 100 |

| 1 | 100–250 |

| 2 | 250–600 |

| 3 | 600–1200 |

| 4 | > 1200 |

A flare is then classified taking S or a number that represents its size and a letter that represents its peak intensity, v.g.: Sn is a normal sunflare.[27]

Duration

[edit]A common measure of flare duration is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) time of flux in the soft X-ray bands 0.05 to 0.4 and 0.1 to 0.8 nm measured by GOES. The FWHM time spans from when a flare's flux first reaches halfway between its maximum flux and the background flux and when it again reaches this value as the flare decays. Using this measure, the duration of a flare ranges from approximately tens of seconds to several hours with a median duration of approximately 6 and 11 minutes in the 0.05 to 0.4 and 0.1 to 0.8 nm bands, respectively.[28][29]

Flares can also be classified based on their duration as either impulsive or long duration events (LDE). The time threshold separating the two is not well defined. The SWPC regards events requiring 30 minutes or more to decay to half maximum as LDEs, whereas Belgium's Solar-Terrestrial Centre of Excellence regards events with duration greater than 60 minutes as LDEs.[30][31]

Effects

[edit]The electromagnetic radiation emitted during a solar flare propagates away from the Sun at the speed of light with intensity inversely proportional to the square of the distance from its source region. The excess ionizing radiation, namely X-ray and extreme ultraviolet (XUV) radiation, is known to affect planetary atmospheres and is of relevance to human space exploration and the search for extraterrestrial life. [citation needed]

Solar flares also affect other objects in the Solar System. Research into these effects has primarily focused on the atmosphere of Mars and, to a lesser extent, that of Venus.[32] The impacts on other planets in the Solar System are little studied in comparison. As of 2024, research on their effects on Mercury have been limited to modeling of the response of ions in the planet's magnetosphere,[33] and their impact on Jupiter and Saturn have only been studied in the context of X-ray radiation back scattering off of the planets' upper atmospheres.[34][35]

Ionosphere

[edit]

Enhanced XUV irradiance during solar flares can result in increased ionization, dissociation, and heating in the ionospheres of Earth and Earth-like planets. On Earth, these changes to the upper atmosphere, collectively referred to as sudden ionospheric disturbances, can interfere with short-wave radio communication and global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) such as GPS,[36] and subsequent expansion of the upper atmosphere can increase drag on satellites in low Earth orbit leading to orbital decay over time.[37][38][additional citation(s) needed]

Flare-associated XUV photons interact with and ionize neutral constituents of planetary atmospheres via the process of photoionization. The electrons that are freed in this process, referred to as photoelectrons to distinguish them from the ambient ionospheric electrons, are left with kinetic energies equal to the photon energy in excess of the ionization threshold. In the lower ionosphere where flare impacts are greatest and transport phenomena are less important, the newly liberated photoelectrons lose energy primarily via thermalization with the ambient electrons and neutral species and via secondary ionization due to collisions with the latter, or so-called photoelectron impact ionization. In the process of thermalization, photoelectrons transfer energy to neutral species, resulting in heating and expansion of the neutral atmosphere.[39] The greatest increases in ionization occur in the lower ionosphere where wavelengths with the greatest relative increase in irradiance—the highly penetrative X-ray wavelengths—are absorbed, corresponding to Earth's E and D layers and Mars's M1 layer.[32][36][40][41][42]

Radio blackouts

[edit]The temporary increase in ionization of the daylight side of Earth's atmosphere, in particular the D layer of the ionosphere, can interfere with short-wave radio communications that rely on its level of ionization for skywave propagation. Skywave, or skip, refers to the propagation of radio waves reflected or refracted off of the ionized ionosphere. When ionization is higher than normal, radio waves get degraded or completely absorbed by losing energy from the more frequent collisions with free electrons.[2][36]

The level of ionization of the atmosphere correlates with the strength of the associated solar flare in soft X-ray radiation. The Space Weather Prediction Center, a part of the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, classifies radio blackouts by the peak soft X-ray intensity of the associated flare.[2]

| Classification | Associated SXR class |

Description[18] |

|---|---|---|

| R1 | M1 | Minor radio blackout |

| R2 | M5 | Moderate radio blackout |

| R3 | X1 | Strong radio blackout |

| R4 | X10 | Severe radio blackout |

| R5 | X20 | Extreme radio blackout |

Solar flare effect

[edit]

During non-flaring or solar quiet conditions, electric currents flow through the ionosphere's dayside E layer inducing small-amplitude diurnal variations in the geomagnetic field. These ionospheric currents can be strengthened during large solar flares due to increases in electrical conductivity associated with enhanced ionization of the E and D layers. The subsequent increase in the induced geomagnetic field variation is referred to as a solar flare effect (sfe) or historically as a magnetic crochet. The latter term derives from the French word crochet meaning hook reflecting the hook-like disturbances in magnetic field strength observed by ground-based magnetometers. These disturbances are on the order of a few nanoteslas and last for a few minutes, which is relatively minor compared to those induced during geomagnetic storms.[43][44]

Health

[edit]Low Earth orbit

[edit]For astronauts in low Earth orbit, an expected radiation dose from the electromagnetic radiation emitted during a solar flare is about 0.05 gray, which is not immediately lethal on its own. Of much more concern for astronauts is the particle radiation associated with solar particle events.[45]

Mars

[edit]The impacts of solar flare radiation on Mars are relevant to exploration and the search for life on the planet. Models of its atmosphere indicate that the most energetic solar flares previously recorded may have provided acute doses of radiation that would have been harmful or almost lethal to mammals and other higher organisms on Mars's surface. Furthermore, flares energetic enough to provide lethal doses, while not yet observed on the Sun, are thought to occur and have been observed on other Sun-like stars.[46][47][48]

Observational history

[edit]Flares produce radiation across the electromagnetic spectrum, although with different intensity. They are not very intense in visible light, but they can be very bright at particular spectral lines. They normally produce bremsstrahlung in X-rays and synchrotron radiation in radio.[49]

Optical observations

[edit]

Solar flares were first observed by Richard Carrington and Richard Hodgson independently on 1 September 1859 by projecting the image of the solar disk produced by an optical telescope through a broad-band filter.[51][52] It was an extraordinarily intense white light flare, a flare emitting a high amount of light in the visual spectrum.[51]

Since flares produce copious amounts of radiation at H-alpha,[53] adding a narrow (≈1 Å) passband filter centered at this wavelength to the optical telescope allows the observation of not very bright flares with small telescopes. For years Hα was the main, if not the only, source of information about solar flares. Other passband filters are also used.[citation needed]

Radio observations

[edit]During World War II, on February 25 and 26, 1942, British radar operators observed radiation that Stanley Hey interpreted as solar emission.[54] Their discovery did not go public until the end of the conflict. The same year, Southworth also observed the Sun in radio, but as with Hey, his observations were only known after 1945. In 1943, Grote Reber was the first to report radioastronomical observations of the Sun at 160 MHz.[55] The fast development of radioastronomy revealed new peculiarities of the solar activity like storms and bursts related to the flares. Today, ground-based radiotelescopes observe the Sun from c. 15 MHz up to 400 GHz.

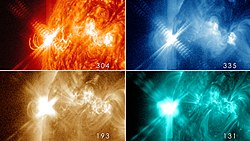

Space telescopes

[edit]Because the Earth's atmosphere absorbs much of the electromagnetic radiation emitted by the Sun with wavelengths shorter than 300 nm, space-based telescopes allowed for the observation of solar flares in previously unobserved high-energy spectral lines. Since the 1970s, the GOES series of satellites have been continuously observing the Sun in soft X-rays, and their observations have become the standard measure of flares, diminishing the importance of the H-alpha classification. Additionally, space-based telescopes allow for the observation of extremely long wavelengths—as long as a few kilometres—which cannot propagate through the ionosphere.

Examples of large solar flares

[edit]

The most powerful flare ever observed is thought to be the flare associated with the 1859 Carrington Event.[57] While no soft X-ray measurements were made at the time, the magnetic crochet associated with the flare was recorded by ground-based magnetometers allowing the flare's strength to be estimated after the event. Using these magnetometer readings, its soft X-ray class has been estimated to be greater than X10[58] and around X45 (±5).[59][60]

In modern times, the largest solar flare measured with instruments occurred on 4 November 2003. This event saturated the GOES detectors, and because of this, its classification is only approximate. Initially, extrapolating the GOES curve, it was estimated to be X28.[61] Later analysis of the ionospheric effects suggested increasing this estimate to X45.[62][63] This event produced the first clear evidence of a new spectral component above 100 GHz.[64]

Prediction

[edit]Current methods of flare prediction are problematic, and there is no certain indication that an active region on the Sun will produce a flare. However, many properties of active regions and their sunspots correlate with flaring. For example, magnetically complex regions (based on line-of-sight magnetic field) referred to as delta spots frequently produce the largest flares. A simple scheme of sunspot classification based on the McIntosh system for sunspot groups, or related to a region's fractal complexity[65] is commonly used as a starting point for flare prediction.[66] Predictions are usually stated in terms of probabilities for occurrence of flares above M- or X-class within 24 or 48 hours. The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) issues forecasts of this kind.[67] MAG4 was developed at the University of Alabama in Huntsville with support from the Space Radiation Analysis Group at Johnson Space Flight Center (NASA/SRAG) for forecasting M- and X-class flares, CMEs, fast CME, and solar energetic particle events.[68] A physics-based method that can predict imminent large solar flares was proposed by Institute for Space-Earth Environmental Research (ISEE), Nagoya University.[69]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Thomas N. Woods (September 2014). "Extreme Ultraviolet Late-Phase Flares: Before and During the Solar Dynamics Observatory Mission". Solar Physics. 289: 3391–3401.

- ^ a b c "Solar Flares (Radio Blackouts)". NOAA/NWS Space Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ a b Woods, Thomas N.; Kopp, Greg; Chamberlin, Phillip C. (2006). "Contributions of the solar ultraviolet irradiance to the total solar irradiance during large flares". Journal of Geophysical Research. 111 (A10). Bibcode:2005AGUFMSA33A..07W. doi:10.1029/2005JA011507.

- ^ Ishikawa, Shin-nosuke; Glesener, Lindsay; Krucker, Säm; Christe, Steven; Buitrago-Casas, Juan Camilo; Narukage, Noriyuki; Vievering, Juliana (2017). "Detection of nanoflare-heated plasma in the solar corona by the FOXSI-2 sounding rocket". Nature Astronomy. 1 (11): 771–774. Bibcode:2017NatAs...1..771I. doi:10.1038/s41550-017-0269-z. ISSN 2397-3366.

- ^ Sigalotti, Leonardo Di G.; Cruz, Fidel (2023). "Unveiling the mystery of solar-coronal heating". Physics Today. 76 (4): 34–40. Bibcode:2023PhT....76d..34S. doi:10.1063/pt.3.5217. Retrieved 2024-05-17.

- ^ Fletcher, L.; Dennis, B. R.; Hudson, H. S.; Krucker, S.; Phillips, K.; Veronig, A.; Battaglia, M.; Bone, L.; Caspi, A.; Chen, Q.; Gallagher, P.; Grigis, P. T.; Ji, H.; Liu, W.; Milligan, R. O.; Temmer, M. (September 2011). "An Observational Overview of Solar Flares" (PDF). Space Science Reviews. 159 (1–4): 19–106. arXiv:1109.5932. Bibcode:2011SSRv..159...19F. doi:10.1007/s11214-010-9701-8. S2CID 21203102.

- ^ Morimoto, Tarou; Kurokawa, Hiroki (31 May 2002). Effects of Magnetic and Gravity forces on the Acceleration of Solar Filaments and Coronal Mass Ejections (PDF). 地球惑星科学関連学会2002年合同大会 2002 Joint Conference of Earth and Planetary Science Related Societies (in Japanese). Tokyo. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ^ Tandberg-Hanssen, E.; Martin, Sara F.; Hansen, Richard T. (March 1980). "Dynamics of flare sprays". Solar Physics. 65 (2): 357–368. Bibcode:1980SoPh...65..357T. doi:10.1007/BF00152799. ISSN 0038-0938. S2CID 122385884.

- ^ "Biggest Solar Flare on Record". Visible Earth. NASA. 15 May 2001.

- ^ Zhu, Chunming; Liu, Rui; Alexander, David; McAteer, R. T. James (19 April 2016). "Observation of the Evolution of a Current Sheet in a Solar Flare". The Astrophysical Journal. 821 (2): L29. arXiv:1603.07062. Bibcode:2016ApJ...821L..29Z. doi:10.3847/2041-8205/821/2/L29.

- ^ Priest, E. R.; Forbes, T. G. (2002). "The magnetic nature of solar flares". The Astronomy and Astrophysics Review. 10 (4): 314–317. Bibcode:2002A&ARv..10..313P. doi:10.1007/s001590100013.

- ^ Holman, Gordon D. (1 April 2006). "The Mysterious Origins of Solar Flares". Scientific American. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ Ryan, James M.; Lee, Martin A. (1991-02-01). "On the Transport and Acceleration of Solar Flare Particles in a Coronal Loop". The Astrophysical Journal. 368: 316. Bibcode:1991ApJ...368..316R. doi:10.1086/169695. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Handy, Brian; Hudson, Hugh (14 July 2000). "Super Regions". Montana State University Solar Physics Group. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ a b Livshits, M. A.; Urnov, A. M.; Goryaev, F. F.; Kashapova, L. K.; Grigor'eva, I. Yu.; Kal'tman, T. I. (October 2011). "Physics of post-eruptive solar arcades: Interpretation of RATAN-600 and STEREO spacecraft observations". Astronomy Reports. 55 (10): 918–927. Bibcode:2011ARep...55..918L. doi:10.1134/S1063772911100064. S2CID 121487634. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Grechnev, V. V.; Kuzin, S. V.; Urnov, A. M.; Zhitnik, I. A.; Uralov, A. M.; Bogachev, S. A.; Livshits, M. A.; Bugaenko, O. I.; Zandanov, V. G.; Ignat'ev, A. P.; Krutov, V. V.; Oparin, S. N.; Pertsov, A. A.; Slemzin, V. A.; Chertok, I. M.; Stepanov, A. I. (July 2006). "Long-lived hot coronal structures observed with CORONAS-F/SPIRIT in the Mg XII line". Solar System Research. 40 (4): 286–293. Bibcode:2006SoSyR..40..286G. doi:10.1134/S0038094606040046. S2CID 121291767. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Savage, Sabrina L.; McKenzie, David E. (1 May 2011). "Quantitative Examination of a Large Sample of Supra-Arcade Downflows in Eruptive Solar Flares". The Astrophysical Journal. 730 (2): 98. arXiv:1101.1540. Bibcode:2011ApJ...730...98S. doi:10.1088/0004-637x/730/2/98. S2CID 119273860.

- ^ a b "NOAA Space Weather Scales". NOAA/NWS Space Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ Rieger, E.; Share, G. H.; Forrest, D. J.; Kanbach, G.; Reppin, C.; Chupp, E. L. (1984). "A 154-day periodicity in the occurrence of hard solar flares?". Nature. 312 (5995): 623–625. Bibcode:1984Natur.312..623R. doi:10.1038/312623a0. S2CID 4348672.

- ^ Kurochka, L. N. (April 1987). "Energy distribution of 15,000 solar flares". Astronomicheskii Zhurnal. 64: 443. Bibcode:1987AZh....64..443K.

- ^ Crosby, Norma B.; Aschwanden, Markus J.; Dennis, Brian R. (February 1993). "Frequency distributions and correlations of solar X-ray flare parameters". Solar Physics. 143 (2): 275–299. Bibcode:1993SoPh..143..275C. doi:10.1007/BF00646488.

- ^ Li, Y. P.; Gan, W. Q.; Feng, L. (March 2012). "Statistical analyses on thermal aspects of solar flares". The Astrophysical Journal. 747 (2): 133. Bibcode:2012ApJ...747..133L. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/747/2/133.

- ^ Aschwanden, Markus J. (2011). Self-Organized Criticality in Astrophysics: The Statistics of Nonlinear Processes in the Universe. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-15001-2. ISBN 978-3-642-15001-2.

- ^ Garner, Rob (6 September 2017). "Sun Erupts With Significant Flare". NASA. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ Schrijver, Carolus J.; Siscoe, George L., eds. (2010), Heliophysics: Space Storms and Radiation: Causes and Effects, Cambridge University Press, p. 375, ISBN 978-1-107-04904-8.

- ^ Pietrow, A. G. M. (2022). Physical properties of chromospheric features: Plage, peacock jets, and calibrating it all (PhD). Stockholm, Sweden: Stockholm University. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.36047.76968.

- ^ Tandberg-Hanssen, Einar; Emslie, A. Gordon (1988). The Physics of Solar Flares. Cambridge University Press. Bibcode:1988psf..book.....T.

- ^ Reep, Jeffrey W.; Knizhnik, Kalman J. (3 April 2019). "What Determines the X-Ray Intensity and Duration of a Solar Flare?". The Astrophysical Journal. 874 (2): 157. arXiv:1903.10564. Bibcode:2019ApJ...874..157R. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab0ae7. S2CID 85517195.

- ^ Reep, Jeffrey W.; Barnes, Will T. (October 2021). "Forecasting the Remaining Duration of an Ongoing Solar Flare". Space Weather. 19 (10). arXiv:2103.03957. Bibcode:2021SpWea..1902754R. doi:10.1029/2021SW002754. S2CID 237709521.

- ^ "Space Weather Glossary". NOAA/NWS Space Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ "The duration of solar flares". Solar-Terrestrial Centre of Excellence. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ a b Yan, Maodong; Dang, Tong; Cao, Yu-Tian; Cui, Jun; Zhang, Binzheng; Liu, Zerui; Lei, Jiuhou (1 November 2022). "A Comparative Study of Ionospheric Response to Solar Flares at Earth, Venus, and Mars". The Astrophysical Journal. 939 (1): 23. Bibcode:2022ApJ...939...23Y. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ac92ff.

- ^ Werner, A. L. E.; Leblanc, F.; Chaufray, J. Y.; Modolo, R.; Aizawa, S.; Hadid, L. Z.; Baskevitch, C. (16 February 2022). "Modeling the Impact of a Strong X-Class Solar Flare on the Planetary Ion Composition in Mercury's Magnetosphere". Geophysical Research Letters. 49 (3). Bibcode:2022GeoRL..4996614W. doi:10.1029/2021GL096614.

- ^ Bhardwaj, Anil; Branduardi-Raymont, G.; Elsner, R. F.; Gladstone, G. R.; Ramsay, G.; Rodriguez, P.; Soria, R.; Waite, J. H.; Cravens, T. E. (February 2005). "Solar control on Jupiter's equatorial X-ray emissions: 26–29 November 2003 XMM-Newton observation". Geophysical Research Letters. 32 (3). arXiv:astro-ph/0504670. Bibcode:2005GeoRL..32.3S08B. doi:10.1029/2004GL021497.

- ^ Bhardwaj, Anil; Elsner, Ronald F.; Waite, J. Hunter Jr.; Gladstone, G. Randall; Cravens, Thomas E.; Ford, Peter G. (10 May 2005). "Chandra Observation of an X-Ray Flare at Saturn: Evidence of Direct Solar Control on Saturn's Disk X-Ray Emissions". The Astrophysical Journal. 624 (2): L121 – L124. arXiv:astro-ph/0504110. Bibcode:2005ApJ...624L.121B. doi:10.1086/430521.

- ^ a b c Mitra, A. P. (1974). Ionospheric Effects of Solar Flares. Astrophysics and Space Science Library. Vol. 46. Dordrecht: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-010-2231-6. ISBN 978-94-010-2233-0.

- ^ "The Impact of Flares". RHESSI Web Site. NASA. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Hayes, Laura A.; O'Hara, Oscar S. D.; Murray, Sophie A.; Gallagher, Peter T. (November 2021). "Solar Flare Effects on the Earth's Lower Ionosphere". Solar Physics. 296 (11): 157. arXiv:2109.06558. Bibcode:2021SoPh..296..157H. doi:10.1007/s11207-021-01898-y.

- ^ Smithtro, C. G.; Solomon, S. C. (August 2008). "An improved parameterization of thermal electron heating by photoelectrons, with application to an X17 flare". Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics. 113 (A8). Bibcode:2008JGRA..113.8307S. doi:10.1029/2008JA013077.

- ^ Fallows, K.; Withers, P.; Gonzalez, G. (November 2015). "Response of the Mars ionosphere to solar flares: Analysis of MGS radio occultation data". Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics. 120 (11): 9805–9825. Bibcode:2015JGRA..120.9805F. doi:10.1002/2015JA021108.

- ^ Thiemann, E. M. B.; Andersson, L.; Lillis, R.; Withers, P.; Xu, S.; Elrod, M.; Jain, S.; Pilinski, M. D.; Pawlowski, D.; Chamberlin, P. C.; Eparvier, F. G.; Benna, M.; Fowler, C.; Curry, S.; Peterson, W. K.; Deighan, J. (28 August 2018). "The Mars Topside Ionosphere Response to the X8.2 Solar Flare of 10 September 2017". Geophysical Research Letters. 45 (16): 8005–8013. Bibcode:2018GeoRL..45.8005T. doi:10.1029/2018GL077730.

- ^ Lollo, Anthony; Withers, Paul; Fallows, Kathryn; Girazian, Zachary; Matta, Majd; Chamberlin, P. C. (May 2012). "Numerical simulations of the ionosphere of Mars during a solar flare". Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics. 117 (A5). Bibcode:2012JGRA..117.5314L. doi:10.1029/2011JA017399.

- ^ Thompson, Richard. "A Solar Flare Effect". Australian Bureau of Meteorology Space Weather Forecasting Centre. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ Curto, Juan José (2020). "Geomagnetic solar flare effects: a review". Journal of Space Weather and Space Climate. 10: 27. Bibcode:2020JSWSC..10...27C. doi:10.1051/swsc/2020027. S2CID 226442270.

- ^ "Why Space Radiation Matters - NASA". 2017-04-13. Retrieved 2025-06-30.

- ^ Smith, David S.; Scalo, John (March 2007). "Solar X-ray flare hazards on the surface of Mars". Planetary and Space Science. 55 (4): 517–527. arXiv:astro-ph/0610091. Bibcode:2007P&SS...55..517S. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2006.10.001.

- ^ Jain, Rajmal; Awasthi, Arun K.; Tripathi, Sharad C.; Bhatt, Nipa J.; Khan, Parvaiz A. (August 2012). "Influence of solar flare X-rays on the habitability on the Mars". Icarus. 220 (2): 889–895. Bibcode:2012Icar..220..889J. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2012.06.011.

- ^ Thirupathaiah, P.; Shah, Siddhi Y.; Haider, S.A. (September 2019). "Characteristics of solar X-ray flares and their effects on the ionosphere and human exploration to Mars: MGS radio science observations". Icarus. 330: 60–74. Bibcode:2018cosp...42E1350H. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2019.04.015.

- ^ Winckler, J. R. (1964-01-01). "Energetic X-Ray Bursts From Solar Flares". NASA Special Publication. 50: 117. Bibcode:1964NASSP..50..117W.

- ^ Carrington, R. C. (November 1859). "Description of a Singular Appearance seen in the Sun on September 1, 1859". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 20: 13–15. Bibcode:1859MNRAS..20...13C. doi:10.1093/mnras/20.1.13.

- ^ a b Carrington, Richard C. (November 1859). "Description of a singular appearance seen in the Sun on September 1, 1859". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 20 (1): 13–15. Bibcode:1859MNRAS..20...13C. doi:10.1093/mnras/20.1.13.

- ^ Hodgson, Richard (November 1859). "On a curious Appearance seen in the Sun". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 20 (1): 15–16. doi:10.1093/mnras/20.1.15a.

- ^ Druett, Malcolm; Scullion, Eamon; Zharkova, Valentina; Matthews, Sarah; Zharkov, Sergei; Rouppe Van der Voort, Luc (27 June 2017). "Beam electrons as a source of Hα flare ribbons". Nature Communications. 8 (1) 15905. Bibcode:2017NatCo...815905D. doi:10.1038/ncomms15905. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5490266. PMID 28653670.

- ^ Goss, W. M.; Hooker, Claire; Ekers, Ronald D. (2023), Goss, W. M.; Hooker, Claire; Ekers, Ronald D. (eds.), "Beginnings of Solar Radio Astronomy, 1944–1945", Joe Pawsey and the Founding of Australian Radio Astronomy: Early Discoveries, from the Sun to the Cosmos, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 155–168, doi:10.1007/978-3-031-07916-0_11, ISBN 978-3-031-07916-0

- ^ "Grote Reber | Department of Physics & Astronomy at Sonoma State University". phys-astro.sonoma.edu. 1911-12-22. Retrieved 2025-06-30.

- ^ "Extreme Space Weather Events". National Geophysical Data Center. Archived from the original on May 22, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ Bell, Trudy E.; Phillips, Tony (6 May 2008). "A Super Solar Flare". Science News. NASA Science. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ Cliver, E. W.; Svalgaard, L. (October 2004). "The 1859 Solar–Terrestrial Disturbance And the Current Limits of Extreme Space Weather Activity". Solar Physics. 224 (1–2): 407–422. Bibcode:2004SoPh..224..407C. doi:10.1007/s11207-005-4980-z. S2CID 120093108.

- ^ Woods, Tom. "Solar Flares" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 October 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ Cliver, Edward W.; Dietrich, William F. (4 April 2013). "The 1859 space weather event revisited: limits of extreme activity" (PDF). J. Space Weather Space Clim. 3: A31. Bibcode:2013JSWSC...3A..31C. doi:10.1051/swsc/2013053. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

- ^ "X-Whatever Flare! (X 28)". SOHO Hotshots. ESA/NASA. 4 November 2003. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ "Biggest ever solar flare was even bigger than thought | SpaceRef – Your Space Reference". SpaceRef. 2004-03-15. Archived from the original on 2012-09-10. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ Curto, Juan José; Castell, Josep; Moral, Ferran Del (2016). "Sfe: waiting for the big one". Journal of Space Weather and Space Climate. 6: A23. Bibcode:2016JSWSC...6A..23C. doi:10.1051/swsc/2016018. ISSN 2115-7251.

- ^ Kaufmann, Pierre; Raulin, Jean-Pierre; de Castro, C. G. Gimnez; Levato, Hugo; Gary, Dale E.; Costa, Joaquim E. R.; Marun, Adolfo; Pereyra, Pablo; Silva, Adriana V. R.; Correia, Emilia (10 March 2004). "A New Solar Burst Spectral Component Emitting Only in the Terahertz Range". The Astrophysical Journal. 603 (2): L121 – L124. Bibcode:2004ApJ...603L.121K. doi:10.1086/383186. S2CID 54878789.

- ^ McAteer, James (2005). "Statistics of Active Region Complexy". The Astrophysical Journal. 631 (2): 638. Bibcode:2005ApJ...631..628M. doi:10.1086/432412.

- ^ Wheatland, M. S. (2008). "A Bayesian approach to solar flare prediction". The Astrophysical Journal. 609 (2): 1134–1139. arXiv:astro-ph/0403613. Bibcode:2004ApJ...609.1134W. doi:10.1086/421261. S2CID 10273389.

- ^ "Forecasts". NOAA/NWS Space Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ Falconer, David; Barghouty, Abdulnasser F.; Khazanov, Igor; Moore, Ron (April 2011). "A tool for empirical forecasting of major flares, coronal mass ejections, and solar particle events from a proxy of active-region free magnetic energy". Space Weather. 9 (4). Bibcode:2011SpWea...9.4003F. doi:10.1029/2009SW000537. hdl:2060/20100032971.

- ^ Kusano, Kanya; Iju, Tomoya; Bamba, Yumi; Inoue, Satoshi (July 31, 2020). "A physics-based method that can predict imminent large solar flares". Science. 369 (6503): 587–591. Bibcode:2020Sci...369..587K. doi:10.1126/science.aaz2511. PMID 32732427.

External links

[edit]- NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center's near real-time solar flare data and resources:

Solar flare

View on GrokipediaPhysical Characteristics

Definition and Overview

A solar flare is a sudden, intense burst of radiation from the Sun's atmosphere, primarily emitting in X-rays, ultraviolet (UV), and radio waves, with durations ranging from minutes to hours.[5][3][9] This phenomenon originates in the solar corona and chromosphere, where it manifests as a rapid release of electromagnetic energy across much of the spectrum, from radio waves to gamma rays.[3] Unlike coronal mass ejections (CMEs), which involve the expulsion of plasma and magnetic fields, solar flares are distinct as primarily electromagnetic radiation events, though they often occur in conjunction with CMEs as part of broader solar eruptive activity.[10][11] At its core, a solar flare involves the basic physical process of magnetic reconnection in the solar corona, where built-up magnetic energy is suddenly converted into thermal and kinetic energy.[12][13] This reconnection accelerates particles and heats plasma to temperatures of 10 to 20 million degrees Kelvin, producing the observed radiation bursts.[14] The process is triggered by the tangling and reconfiguration of magnetic field lines near sunspots, releasing stored energy that powers the flare's explosive characteristics.[15] Solar flares play a key role in solar activity, contributing to the dynamic variability of the Sun's output over its 11-year cycle.[1] Their typical energy output ranges from to ergs, equivalent to the explosive force of millions of hydrogen bombs.[3][16] Visually, flares appear as compact brightenings on the solar disk when observed in H-alpha or extreme ultraviolet (EUV) wavelengths, highlighting the localized regions of intensified emission.[17][18]Cause and Trigger Mechanisms

Solar flares are primarily driven by the process of magnetic reconnection in the Sun's corona, where oppositely directed magnetic field lines in the solar atmosphere come into close proximity, break, and reconnect in a new configuration, thereby converting stored magnetic energy into kinetic, thermal, and radiative energy. Direct evidence for this process includes observations of coronal loop structures, hard X-ray sources at reconnection sites, plasma inflows and outflows, and signatures of particle acceleration, obtained from multi-wavelength observations by missions such as SOHO, SDO, Parker Solar Probe, and RHESSI.[19][20][21] This reconnection occurs in magnetically complex regions, allowing the sudden release of energy that powers the flare.[22] The energy available for release is approximated by the magnetic energy content in the reconnection volume, given by the formula where is the magnetic field strength and is the volume of the reconnection region; this expression derives from the magnetic energy density in magnetohydrodynamics and highlights how stronger fields or larger volumes can yield greater flare energies.[23] The triggers for initiating magnetic reconnection often involve photospheric motions that build up magnetic stress over time. Shearing motions from convection in the photosphere twist and shear magnetic field lines, increasing the non-potentiality of the field and leading to instability.[24] Flux emergence, where new magnetic flux rises from the solar interior into the atmosphere, can bring opposite-polarity fields into contact, promoting reconnection.[25] Additionally, tether-cutting instabilities occur when internal reconnection within a sheared arcade severs overlying field lines, allowing the core field to erupt and initiate the main reconnection site higher in the corona.[26] The standard model for many solar flares, particularly two-ribbon flares, is the CSHKP model, which integrates these processes into a cohesive framework.[27] Named after contributions from Carmichael (1964), Sturrock (1966), Hirayama (1974), and Kopp and Pneuman (1976), it describes a slow buildup phase where magnetic shear accumulates in active regions, followed by a fast impulsive phase triggered by reconnection that forms a current sheet and ejects plasma, leading to sequential energy release.[28][29][30] Flares predominantly originate in active regions near sunspot groups, where concentrated magnetic fields create the necessary complexity for reconnection; sunspots serve as footpoints for these arched field lines, and their relative motions drive the shearing that destabilizes the configuration.[31]Morphological Features

Solar flares exhibit distinct morphological features that evolve through their lifecycle, revealing the spatial and temporal manifestations of energy release in the solar atmosphere. During the impulsive phase, compact bright regions known as flare kernels emerge at the footpoints of reconnected magnetic field lines, appearing as intense emission in chromospheric lines such as H-alpha. These kernels are often clustered within elongated structures called flare ribbons, which trace the polarity inversion line of the underlying photospheric magnetic field and can span tens of thousands of kilometers. The ribbons typically brighten rapidly as non-thermal electrons precipitate into the chromosphere, heating the plasma and producing enhanced H-alpha emission. In the post-eruption phase, the flare develops prominent coronal structures, including loops filled with hot plasma reaching temperatures of 10-20 MK, which organize into arcades perpendicular to the ribbons. These loops form as successive magnetic reconnections occur at higher altitudes, creating nested arcades where cooler, inner loops are enveloped by hotter, outer ones. Chromospheric evaporation plays a key role here, as energy input from accelerated particles drives upward flows of heated plasma from the chromosphere into the corona, filling the loops with dense, hot material over minutes. Subsequent cooling leads to condensation, where the plasma density increases and temperatures drop, sometimes forming cooler threads within the arcades.[32] Associated with many flares, particularly those accompanied by coronal mass ejections, are dimming regions—transient areas of reduced coronal density and emission in extreme ultraviolet (EUV) and soft X-ray wavelengths, resulting from the evacuation of plasma during mass ejection. These dimmings often appear as expansive, low-intensity patches near the flare site, with density depletions up to 50% or more, recovering over hours to days as plasma refills the volume.[33] The temporal evolution of these features unfolds in distinct phases: a rapid rise phase lasting minutes, marked by the initial brightening of kernels and ribbons alongside the onset of evaporation; a peak phase where emissions in hard X-rays and H-alpha maximize, coinciding with loop filling; and a prolonged decay phase of hours, during which arcade structures cool and dimmings persist. EUV and soft X-ray imaging, such as from the Solar Dynamics Observatory, vividly captures this progression, revealing the nested arcades as layered brightenings that grow outward with time.Classification and Occurrence

Classification Systems

Solar flares are primarily classified using the Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES) soft X-ray scale, which measures the peak flux of emissions in the 1–8 Å (0.1–0.8 nm) wavelength band in units of watts per square meter (W/m²).[7] This logarithmic system divides flares into five classes—A, B, C, M, and X—each representing an order-of-magnitude increase in intensity, with further subdivisions from 1 to 9 within each class based on the exact flux value.[7] For instance, an A-class flare has a peak flux of to W/m², while an X-class flare exceeds W/m²; the notation X1.0 specifically denotes a flux of W/m² at the boundary of the X class.[7] An earlier and complementary classification system relies on observations in the H-alpha spectral line, assessing flares by their optical brightness and apparent area on the solar disk as seen from Earth.[34] Flares smaller than the threshold for numbered classes are termed subflares, while larger events are graded by area in millionths of the Sun's visible disk (1, 2, or 3) combined with brightness intensity: N for normal, B for bright, or F for faint.[35] Thus, a 2N flare covers about 2% of the solar disk with normal brightness, and a 3B represents the most intense, covering 3% with bright emission; this system, though subjective, provides morphological context not captured by X-ray measurements alone.[35] Flares are also categorized by duration, distinguishing short-lived impulsive events, which typically last minutes and exhibit rapid rise and decay in emissions, from gradual or long-duration events (LDEs) that persist for hours with slower, extended profiles.[36] Impulsive flares are often compact and associated with quick energy release in lower atmospheric layers, whereas gradual flares involve prolonged heating and complex structures, such as arcades of loops, leading to sustained soft X-ray output.[37] For a more comprehensive assessment, classifications often combine soft X-ray and H-alpha metrics, as seen in historical catalogs that pair GOES intensity with optical importance to rate overall flare significance.[34] This integrated approach accounts for multi-wavelength signatures, though no single universal composite index exists. These systems have inherent limitations: the GOES scale reflects only peak flux, not total radiated energy, which requires integrating flux over time for accurate estimation.[38] Moreover, flare classes do not directly indicate geoeffectiveness, as impacts on Earth depend on factors like the flare's solar location, association with coronal mass ejections, and interplanetary propagation rather than intensity alone.[38]Frequency and Distribution

Solar flares exhibit a pronounced variation in frequency tied to the 11-year solar cycle, with activity peaking during solar maximum when magnetic complexity on the Sun is highest and declining sharply toward solar minimum. During solar maximum, the rate of C-class flares can approach 10,000 per year, reflecting the abundance of active regions capable of producing lower-energy events, while near solar minimum, overall flare occurrences drop to a few hundred C-class events annually or less.[39] This cyclic modulation arises from the evolution of the Sun's global magnetic dynamo, which generates more sunspot groups and twisted field lines conducive to reconnection during the cycle's ascending and peak phases.[5] The distribution of flares by intensity class underscores their rarity at higher energies: X-class flares, the most powerful, occur approximately 8 times per 11-year cycle on average for events exceeding X10 intensity, though all X-class events number around 100 in active cycles like Solar Cycle 23. M-class flares are more common, totaling about 100–200 per cycle for moderate intensities, while C-class events number in the thousands across the cycle, comprising the bulk of observed activity.[40] These statistics highlight how flare productivity scales inversely with energy output, with lower-class events dominating due to the prevalence of weaker magnetic instabilities. In Solar Cycle 25, which began in December 2019, activity has exceeded initial predictions, with over 50 X-class flares recorded by mid-2025, indicating a stronger-than-average cycle.[41] Spatially, solar flares are highly concentrated in active regions, which cover only 5–10% of the solar surface even at maximum and serve as hotspots for magnetic reconnection. These regions, often associated with sunspot groups, host the vast majority of flares, with over 90% occurring within 30° of the solar equator. During the rising phase of the solar cycle, flare frequency increases near the equator as active regions migrate equatorward from higher latitudes (Spörer's law), leading to a band-like distribution symmetric about the equator but with occasional hemispheric preferences.[3][42] Over longer timescales, flare frequency is modulated by the 11-year Schwabe cycle superimposed on the 22-year Hale cycle, which influences hemispheric asymmetry through the reversal of the Sun's magnetic polarity every cycle. The Hale cycle introduces alternating dominance between hemispheres, with northern-hemisphere flares often outnumbering southern during even cycles and vice versa in odd cycles, resulting in asymmetry indices that oscillate with a ~22-year period. This pattern, evident in radio flux and sunspot data, extends to flare distributions and reflects underlying dynamo asymmetries, including a possible northward-shifted relic field. Recent analyses of Cycles 17–25 confirm this Hale modulation, with Cycle 25 showing reduced overall asymmetry compared to Cycle 24.[43][44]Impacts and Effects

Effects on Earth's Atmosphere and Magnetosphere

Solar flares release intense bursts of X-ray and extreme ultraviolet (EUV) radiation that propagate to Earth at the speed of light, interacting primarily with the sunlit side of the planet's upper atmosphere. This radiation enhances ionization in the lower ionosphere, particularly the D-layer at altitudes of 60–90 km, by breaking apart neutral molecules and producing additional free electrons. The resulting increase in electron density can be significant, with studies showing enhancements of up to several orders of magnitude during intense events, altering the refractive properties of the ionosphere for radio wave propagation.[7][45] These ionospheric disturbances manifest as radio blackouts, where high-frequency (HF) radio signals (3–30 MHz) are absorbed due to energy loss from electron collisions in the denser D-layer. Blackouts are more pronounced on the dayside and scale with flare intensity: M-class flares (peak flux ~10^{-5} W/m² in 1–8 Å X-rays) typically cause disruptions lasting 5–20 minutes, while X-class flares (≥10^{-4} W/m²) can extend blackouts to 30 minutes to 2 hours, with examples like the X9.3 event on 6 September 2017 producing fade-outs up to 120 minutes at mid-latitude stations. A related phenomenon is the sudden ionospheric disturbance (SID), characterized by rapid enhancements in D-layer absorption that cause phase anomalies in very low frequency (VLF) signals, often detectable within seconds of the flare onset and lasting 5–20 minutes as the ionization peaks and decays.[7][38][45] Direct geomagnetic effects from solar flares are generally subtle and arise from enhanced ionospheric conductivity, which amplifies the solar quiet (Sq) currents and induces small variations (solar flare effects, or Sfes) in Earth's magnetic field, typically on the order of 1–10 nT at mid-latitudes with durations around 16 minutes. These are distinct from stronger indirect geomagnetic storms triggered by coronal mass ejections (CMEs) associated with flares, as direct particle acceleration into the magnetosphere during flares is minimal without magnetic reconnection. Polar regions may experience more noticeable electrodynamic coupling, including reconfiguration of magnetospheric convection and reduced Joule heating in the E-region (90–150 km), as observed during the 2017 X-class flare.[38][46] Navigation systems like GPS are affected through ionospheric scintillation and delays caused by total electron content (TEC) fluctuations, where flare-induced ionization can increase vertical TEC by 10–100% or more, leading to signal phase shifts and positioning errors up to several meters. For instance, during large flares, TEC enhancements correlate with EUV flux peaks, exacerbating range errors on the dayside where the ionosphere is most disturbed. These effects highlight the flares' role in short-term disruptions to the coupled atmosphere-magnetosphere system, though they typically subside as the radiation subsides.[38][45]Technological and Biological Impacts

Solar flares pose significant risks to technological infrastructure primarily through their associated emissions of X-rays and high-energy particles, which can disrupt satellite operations and communication systems. The intense X-ray radiation from flares ionizes the Earth's upper atmosphere, leading to shortwave fadeouts that cause blackouts in high-frequency (HF) radio communications on the sunlit side of the planet, with durations scaling by intensity: typically 5–20 minutes for M-class and up to 30 minutes to 2 hours for X-class events. These blackouts affect aviation, maritime, and amateur radio operations in affected regions, with mitigation often involving switching to satellite-based relays or very high-frequency (VHF) alternatives. Additionally, solar energetic particles (SEPs) released during flares can penetrate satellite electronics in low Earth orbit (LEO), causing single-event upsets (SEUs) that flip bits in memory and lead to temporary malfunctions or data errors in unshielded components. Flares also heat and expand the ionosphere, increasing atmospheric density and drag on LEO satellites, which can alter orbits and necessitate fuel-intensive maneuvers to maintain positioning. Power grids experience indirect vulnerabilities from solar flares through their frequent association with coronal mass ejections (CMEs), which trigger geomagnetic storms and induce geomagnetically induced currents (GICs) in long transmission lines, potentially overheating transformers and causing widespread outages. Flares alone produce minimal direct induction on power systems due to their electromagnetic nature, but the coupled effects with storms amplify risks, as seen in historical events where grid failures led to blackouts affecting millions. Economic impacts from major flare-related disruptions, particularly in satellite operations, are estimated at $10 million to $100 million per event, including costs for orbit corrections, lost revenue from service interruptions, and hardware repairs, with global annual figures exceeding $200 million from space weather effects. For instance, a 2022 geomagnetic storm linked to solar activity resulted in the loss of 40 Starlink satellites due to enhanced drag, costing SpaceX approximately $20 million. On the biological front, solar flares elevate radiation exposure risks for air travelers and astronauts, primarily via SEPs that partially penetrate Earth's magnetosphere during solar proton events. Polar flights, which traverse regions of weaker magnetic shielding, can see dose rates spike to levels delivering 10 to 20 microsieverts (μSv) per event, comparable to several chest X-rays and contributing to cumulative exposure for frequent flyers. For astronauts in space, NASA models assess cancer risks from chronic and acute radiation, including flare-induced SEPs, with projections indicating a potential 1% increase in lifetime fatal cancer risk per year of exposure in low-Earth orbit environments, though protective measures like storm shelters mitigate acute doses. These models, such as the 2020 NASA Space Cancer Risk Model, incorporate epidemiological data and incorporate uncertainties to limit overall exposure-induced death risk to 3% for career astronauts.Effects Beyond Earth

Solar flares release solar energetic particles (SEPs) that propagate through the heliosphere, creating enhanced radiation environments in deep space far beyond Earth's influence. These particles, accelerated to energies reaching up to several GeV during major events, pose risks to uncrewed probes operating at great distances from the Sun. For instance, the Voyager spacecraft, launched in 1977, detected SEPs from 22 solar flare events between 1977 and 1982, with composition measurements for elements from Z=3 to Z=30 revealing fluxes that could degrade electronics and scientific instruments over long missions.[47] Such SEP fluxes, often impulsive and lasting hours to days, increase the cumulative radiation dose for deep-space explorers like Voyager 1 and 2, which continue to monitor heliospheric boundaries into the 2020s.[48] On Mars, lacking a global magnetic field, solar flares directly ionize the thin upper atmosphere, precipitating charged particles that produce widespread aurorae visible across the planet. During the X8.2-class flare on 10 September 2017, the MAVEN orbiter observed global auroral emissions more than 25 times brighter than previous records, resulting from SEP precipitation into the atmosphere and enhanced X-ray ionization.[49] Similarly, an X12-class flare on May 20, 2024, generated planet-engulfing aurorae and elevated radiation levels on the surface, as measured by the Curiosity rover's Radiation Assessment Detector (RAD).[50] For surface habitats, these events deliver radiation doses of approximately 0.2 to 2 mSv per X-class flare, depending on event intensity and atmospheric attenuation, comparable to several weeks of galactic cosmic ray background but acutely hazardous without shielding.[51] The Moon, with no magnetosphere or substantial atmosphere, experiences even more direct exposure to SEP fluxes from solar flares, amplifying risks for lunar surface operations like NASA's Artemis program. During a major solar eruption in August 2023, instruments on the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) detected significant increases in particle fluxes at the lunar surface, highlighting the vulnerability of astronauts to doses potentially exceeding 100 mGy in unshielded scenarios for extreme events.[52] Artemis missions must account for this enhanced particle environment, where radiation levels can be an order of magnitude higher than in low Earth orbit, necessitating habitat designs with regolith shielding or storm shelters.[53] In the broader heliosphere, electromagnetic radiation from solar flares propagates at the speed of light, arriving nearly instantaneously across interplanetary distances, while SEPs travel at 0.1 to 1 times the speed of light, allowing extended exposure windows. These SEPs can interact with comet tails, as observed during a March 2015 event at comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, where Rosetta detected SEP fluxes altering plasma densities and ion distributions in the coma.[54] At Jupiter, SEP influxes from flares contribute to magnetospheric compression and auroral intensification; solar storms associated with flares shift the magnetopause boundary, injecting particles that enhance X-ray aurorae and heat the ionosphere.[55] Such interactions demonstrate how flare-driven SEPs permeate the heliosphere, influencing distant magnetospheres and neutral structures over scales of astronomical units.[56] Recent missions have provided in-situ observations of these effects. During its 2022 close approach, ESA/NASA's Solar Orbiter detected an M-class flare on April 2, 2022, including associated filament eruption and SEP onset, revealing particle acceleration mechanisms at unprecedented proximity.[57] NASA's Parker Solar Probe, from 2018 through 2025, has made multiple in-situ detections of impulsive flares, confirming that low-energy ions (tens to hundreds of keV) observed in interplanetary space originate directly from flare reconnection sites, with over a dozen events analyzed by mid-2025.[58] These observations underscore the heliosphere-wide reach of flare emissions, informing models for deep-space mission planning.Observation and History

Early Observations

The first documented observation of a solar flare occurred on September 1, 1859, during what is known as the Carrington Event, when British astronomer Richard Carrington visually detected a sudden brightening in white light above a large sunspot group using a projected telescope image.[59] This event, independently confirmed by Richard Hodgson, appeared as two patches of intense illumination that intensified and faded over about 17 minutes, marking the initial recognition of solar flares as transient phenomena distinct from the more persistent sunspots.[60] Carrington described the patches as covering an area of about 116 millionths of the solar hemisphere (equivalent to roughly 180 million square kilometers).[61] Advancements in optical observations began in the early 20th century with the development of spectroheliographs, enabling imaging in specific wavelengths like hydrogen-alpha (H-alpha). At Mount Wilson Observatory, George Ellery Hale pioneered H-alpha spectroheliography in 1908, but the first clear detection of a solar flare in this line occurred in 1917, when Ferdinand Ellerman recorded bright, compact emissions associated with active regions, confirming flares as chromospheric brightenings separate from sunspot umbrae and penumbrae.[62] These ground-based H-alpha images from the 1910s and 1920s, taken with tower telescopes, revealed flares' rapid evolution and association with prominences, though limited resolution often blurred finer details.[63] The discovery of solar radio emissions in the 1940s expanded flare observations beyond visible light, initially as unintended wartime detections. In February 1942, British radar operators, led by James Hey, recorded intense noise bursts interfering with coastal defense systems at wavelengths around 4-6 meters, later correlated with optical flares during solar active periods.[64] These solar radio bursts, confirmed in 1946 by Hey's analysis, demonstrated that flares produce broadband radio emissions, providing evidence of accelerated electrons in the solar atmosphere.[65] Key milestones in radio studies included the first dynamic radio spectrum of a solar flare in 1947, obtained by J. Paul Wild using a swept-frequency receiver in Australia, which visualized frequency-drifting bursts linked to flare onset.[66] By the 1950s, researchers established a direct connection between major flares and geomagnetic storms on Earth; for instance, a 1958 study by Warwick analyzed 115 class 3+ flares and found 68 associated with subsequent storms, attributing disturbances to flare-ejected plasma impacting the magnetosphere.[67] Theoretically, Ronald G. Giovanelli proposed in 1946 that flares arise from magnetic reconnection, where oppositely directed fields in sunspot penumbrae annihilate, releasing energy to accelerate particles and heat plasma.[68] This hypothesis, building on observations of neutral-line alignments in flares, laid foundational groundwork despite lacking direct field measurements. Pre-space era studies were constrained by ground-based limitations, including atmospheric absorption of ultraviolet and X-ray emissions, daytime-only visibility, and seeing distortions that obscured sub-arcsecond structures and coronal extensions.[69]Modern Detection Methods

Modern detection of solar flares relies on a suite of space-based and ground-based instruments operating across multiple wavelengths, enabling comprehensive monitoring of flare onset, evolution, and impacts. These methods have evolved since the 1960s, incorporating advanced imaging, spectroscopy, and in-situ measurements to capture phenomena from extreme ultraviolet (EUV) emissions to high-energy particles. Space-based observatories play a central role in flare detection by providing uninterrupted, high-resolution data above Earth's atmosphere. The Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), launched in 1995, uses the Extreme-ultraviolet Imaging Telescope (EIT) to observe solar flares in EUV wavelengths, revealing coronal plasma dynamics and pre-flare activity through four spectral filters. Similarly, the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), operational since 2010, employs the Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA) for multi-wavelength EUV and X-ray imaging at 1-arcsecond resolution and 12-second cadence, allowing detailed tracking of flare ribbon formation and loop oscillations. SDO's Helioseismic and Magnetic Imager (HMI) complements this by providing vector magnetograms of the solar surface, which correlate magnetic field changes with flare initiation. For hard X-ray emissions indicative of particle acceleration, the Reuven Ramaty High Energy Solar Spectroscopic Imager (RHESSI), active from 2002 to 2018, performed spectroscopy and imaging using germanium detectors, resolving energy spectra from 3 keV to 17 MeV to study non-thermal processes in flares. Ground-based instruments supplement space observations by capturing radio and optical signatures unaffected by atmospheric absorption in those bands. The Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) in New Mexico detects radio bursts from solar flares, producing dynamic spectra that trace gyrosynchrotron emission from accelerated electrons during the impulsive phase. Japan's Nobeyama Radioheliograph, operational since 1992, offers high spatial resolution radio imaging at 17 GHz, enabling mapping of flare-associated microwave sources. For optical observations, the Global Oscillation Network Group (GONG) network of six stations worldwide provides full-disk H-alpha images every minute, capturing chromospheric brightenings and filament eruptions linked to flares. A multi-wavelength approach integrates data from these instruments to reconstruct the full temporal and spatial evolution of solar flares. Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites (GOES), operated by NOAA since the 1970s, monitor soft X-ray fluxes (1-8 Å) in real-time to classify flare intensity. Real-time GOES data are disseminated by NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC), with recent measurements (up to 7 days) accessible through JSON endpoints such as [70]. No public JSON endpoint exists for historical archives; these are maintained by NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) in netCDF-4 format for operational observations and text formats for daily summaries.[71][72] These GOES measurements are cross-referenced with EUV images from SDO/AIA and radio spectra from VLA or Nobeyama for a holistic view of energy release phases. This synergy reveals how flares progress from magnetic reconnection in the corona (detected in EUV) to particle precipitation (seen in hard X-rays and H-alpha). In-situ measurements detect flare-related effects propagating through the heliosphere. The Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE), launched in 1997, and the Wind spacecraft, operational since 1994, use particle detectors to monitor solar energetic particles (SEPs) accelerated by flares, measuring fluxes and compositions near Earth. More recently, the Parker Solar Probe, launched in 2018, has provided unprecedented in-situ data on near-Sun magnetic fields and plasma during flybys, capturing flare-driven shocks and turbulence at distances as close as 0.17 AU. Data analysis techniques enhance interpretation of these observations, particularly for inferring physical conditions. Inversion methods applied to multi-filter EUV or X-ray data, such as filter-ratio techniques on SDO/AIA images, estimate flare loop temperatures around 10^7 K by comparing intensities in different passbands, assuming optically thin plasma emission.Notable Solar Flares

One of the most significant historical solar flares is the Carrington Event on September 1, 1859, during solar cycle 10. British astronomer Richard Carrington observed a brilliant white-light flare on the Sun's surface through a projected telescope image for about 5 minutes, covering an area equivalent to roughly 116 millionths of the solar hemisphere (about 180 million square kilometers).[73][61][74] Modern estimates classify it as an X45 (±5) intensity based on reconstructions of its soft X-ray flux and associated geomagnetic effects, far exceeding typical X-class events. The flare triggered a massive coronal mass ejection (CME) that arrived at Earth within 17 hours, inducing currents that disrupted telegraph systems worldwide, caused fires in equipment, and produced auroras visible in tropical latitudes.[73][61][74] Another impactful event occurred in March 1989 during solar cycle 22, when active region 5395 produced a series of intense X-class flares, including an X15 on March 6. The region culminated in a major X-class flare and high-speed halo CME on March 12, which struck Earth's magnetosphere on March 13, generating severe geomagnetic disturbances. The resulting induced currents overwhelmed the Hydro-Québec power grid, leading to a cascading blackout that left about 6 million people without electricity for up to 9 hours and caused economic losses estimated in the tens of millions of dollars. Satellite operations were also affected, with temporary loss of control for several U.S. spacecraft due to enhanced atmospheric drag.[75][76][77] In modern times, the Halloween solar storms of October-November 2003 marked one of the most active periods since the Space Age began, featuring multiple X-class flares from active region 0486 during solar cycle 23. The strongest was an X17 flare on October 28, peaking at over 17 × 10^{-4} W/m² in soft X-ray flux, followed by an X10 flare on November 2; both were associated with fast CMEs traveling at speeds exceeding 2,000 km/s. These events elevated radiation levels on the International Space Station, prompting crew alerts and safe haven procedures, while ground-based systems experienced minor power fluctuations and widespread high-frequency radio blackouts lasting several hours.[78][79][80] A close call came on July 23, 2012, when an X1.8-class solar flare from active region 1520 produced a powerful CME during solar cycle 24. The CME, ejecting material at over 2,200 km/s and spanning more than 1 astronomical unit in width, narrowly missed Earth by passing about 5 days late relative to our orbit, as captured by NASA's STEREO-A spacecraft. Had it struck, models suggest it could have rivaled the 1989 event in geomagnetic impact, potentially disrupting satellites, power grids, and communications globally.[81][82][83] More recently, on May 14, 2024, the Sun produced an X8.7 flare—the strongest of solar cycle 25 to that point—from active region 3664. Peaking at 12:51 p.m. ET, it emitted intense soft X-ray radiation and was accompanied by a CME, though the main impacts were ionospheric: severe radio blackouts affected high-frequency communications over Europe and Asia for up to 2 hours, with R3-level disruptions reported. This event underscored ongoing solar maximum activity, with no major geomagnetic effects on Earth due to the CME's trajectory.[84][85][86] In March 2025, during the peak of solar cycle 25, an X1.1 flare erupted on March 28 from active region 4046 near the solar limb. Observed by NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory, it was associated with a significant plasma eruption and a solar energetic particle (SEP) event detected by the Solar Orbiter mission, highlighting interplanetary propagation effects. The flare caused brief radio blackouts but no widespread terrestrial disruptions. As of November 2025, solar cycle 25 continues with heightened activity, though no subsequent flares have exceeded X-class intensities reported here.[87][88][89]Forecasting and Research

Prediction Techniques

Solar flare prediction relies on a combination of statistical and physics-based techniques to estimate the likelihood and timing of eruptions from active regions on the Sun. Statistical methods often model flare occurrences using Poisson statistics, assuming that flares in a given active region follow a random process where the rate is constant over short intervals. This approach calculates flare probabilities based on the historical flaring rate of the region, enabling simple Bayesian forecasts that update predictions as new flares are observed.[90] Additionally, flare probabilities are derived from the magnetic complexity of sunspots, such as through the McIntosh classification system, which categorizes active regions by size, shape, and magnetic structure to assign qualitative flare potential (e.g., simple regions like A-type have low risk, while complex beta-gamma-delta groups indicate higher M- and X-class flare chances).[91] Physics-based methods focus on the underlying magnetic processes driving flares, such as the buildup of free magnetic energy in the corona. Magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) simulations model the evolution of coronal magnetic fields, driven by photospheric observations, to track energy accumulation and identify instability thresholds that precede eruptions. Proxies for this energy, like photospheric magnetic shear—the angle between magnetic field lines and the neutral line separating opposite polarities—serve as indicators of stress in active regions, with higher shear correlating to increased flare productivity.[92][93] Short-term forecasting, or nowcasting, typically covers 1-24 hours ahead and uses real-time magnetograms from instruments like the Solar Dynamics Observatory to monitor active region evolution, applying machine learning or heuristic rules to detect precursors like emerging flux or shear changes. Long-term predictions, spanning days to the solar cycle duration, integrate solar cycle models that extrapolate sunspot numbers and active region emergence patterns to estimate overall flare activity levels.[94][95] Current prediction success rates vary by flare class and timeframe. A verification of operational probabilistic forecasts issued by the NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) for M-class and X-class solar flares over 1998–2024 shows that these forecasts do not outperform simple baselines such as persistence and climatology across key metrics. They exhibit poor calibration, high false alarm rates (61–71% for X-class flares at a 0.5 probability threshold, depending on lead time), low recall for rare events (e.g., approximately 0.08 for X-class at the same threshold), and misleadingly high accuracy due to severe class imbalance (where a trivial "no flare" baseline can achieve approximately 97.4% accuracy for X-class events). The True Skill Statistic (TSS) for SWPC operational models is approximately 0.4 for M-class flares within 24 hours under standard thresholds but around 0.05–0.08 for rarer X-class events, though advanced or optimized methods can reach up to 0.61. Research models in various studies have achieved TSS scores in the 0.3–0.7 range. Due to the nonlinear and chaotic nature of the solar dynamo, which introduces inherent unpredictability in magnetic field evolution, forecasting remains challenging, and no major improvements or updated performance metrics have been reported for 2025–2026 during the peak of Solar Cycle 25.[96] Operational systems, such as the NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) alerts, provide probabilistic forecasts based on these techniques, issuing warnings for radio blackouts from expected flares. European Union H2020 projects, like FLARECAST, have advanced heuristic methods by automating feature extraction from multi-instrument data to improve short-term flare likelihood estimates.[97][98][99]Recent Advances and Missions