Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nutrition

View on Wikipedia

Nutrition is the biochemical and physiological process by which an organism uses food and water to support its life. The intake of these substances provides organisms with nutrients (divided into macro- and micro-) which can be metabolized to create energy and chemical structures; too much or too little of an essential nutrient can cause malnutrition. Nutritional science, the study of nutrition as a hard science, typically emphasizes human nutrition.

The type of organism determines what nutrients it needs and how it obtains them. Organisms obtain nutrients by consuming organic matter, consuming inorganic matter, absorbing light, or some combination of these. Some can produce nutrients internally by consuming basic elements, while some must consume other organisms to obtain pre-existing nutrients. All forms of life require carbon, energy, and water as well as various other molecules. Animals require complex nutrients such as carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins, obtaining them by consuming other organisms. Humans have developed agriculture and cooking to replace foraging and advance human nutrition. Plants acquire nutrients through the soil and the atmosphere. Fungi absorb nutrients around them by breaking them down and absorbing them through the mycelium.

History

[edit]Scientific analysis of food and nutrients began during the chemical revolution in the late 18th century. Chemists in the 18th and 19th centuries experimented with different elements and food sources to develop theories of nutrition.[1] Modern nutrition science began in the 1910s as individual micronutrients began to be identified. The first vitamin to be chemically identified was thiamine in 1926, and vitamin C was identified as a protection against scurvy in 1932.[2] The role of vitamins in nutrition was studied in the following decades. The first recommended dietary allowances for humans were developed to address fears of disease caused by food deficiencies during the Great Depression and the Second World War.[3] Due to its importance in human health, the study of nutrition has heavily emphasized human nutrition and agriculture, while ecology is a secondary concern.[4]

Nutrients

[edit]Nutrients are substances that provide energy and physical components to the organism, allowing it to survive, grow, and reproduce. Nutrients can be basic elements or complex macromolecules. Approximately 30 elements are found in organic matter, with nitrogen, carbon, and phosphorus being the most important.[5] Macronutrients are the primary substances required by an organism, and micronutrients are substances required by an organism in trace amounts. Organic micronutrients are classified as vitamins, and inorganic micronutrients are classified as minerals. Over-nutrition of macronutrients is a major cause of obesity and increases the risk of developing various non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including type 2 diabetes, stroke, hypertension, coronary heart disease, osteoporosis, and some forms of cancer.[6] Nutrients can also be classified as essential or nonessential, with essential meaning the body cannot synthesize the nutrient on its own.[7]

Nutrients are absorbed by the cells and used in metabolic biochemical reactions. These include fueling reactions that create precursor metabolites and energy, biosynthetic reactions that convert precursor metabolites into building block molecules, polymerizations that combine these molecules into macromolecule polymers, and assembly reactions that use these polymers to construct cellular structures.[5]

Nutritional groups

[edit]Organisms can be classified by how they obtain carbon and energy. Heterotrophs are organisms that obtain nutrients by consuming the carbon of other organisms, while autotrophs are organisms that produce their own nutrients from the carbon of inorganic substances like carbon dioxide. Mixotrophs are organisms that can be heterotrophs and autotrophs, including some plankton and carnivorous plants. Phototrophs obtain energy from light, while chemotrophs obtain energy by consuming chemical energy from matter. Organotrophs consume other organisms to obtain electrons, while lithotrophs obtain electrons from inorganic substances, such as water, hydrogen sulfide, dihydrogen, iron(II), sulfur, or ammonium.[8] Prototrophs can create essential nutrients from other compounds, while auxotrophs must consume preexisting nutrients.[9]

Diet

[edit]In nutrition, the diet of an organism is the sum of the foods it eats.[10] A healthy diet improves the physical and mental health of an organism. This requires ingestion and absorption of vitamins, minerals, essential amino acids from protein and essential fatty acids from fat-containing food. Carbohydrates, protein and fat play major roles in ensuring the quality of life, health and longevity of the organism.[11] Some cultures and religions have restrictions on what is acceptable for their diet.[12]

Nutrient cycle

[edit]A nutrient cycle is a biogeochemical cycle involving the movement of inorganic matter through a combination of soil, organisms, air or water, where they are exchanged in organic matter.[13] Energy flow is a unidirectional and noncyclic pathway, whereas the movement of mineral nutrients is cyclic. Mineral cycles include the carbon cycle, sulfur cycle, nitrogen cycle, water cycle, phosphorus cycle, and oxygen cycle, among others that continually recycle along with other mineral nutrients into productive ecological nutrition.[13]

Biogeochemical cycles that are performed by living organisms and natural processes are water, carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur cycles.[14] Nutrient cycles allow these essential elements to return to the environment after being absorbed or consumed.[15] Without proper nutrient cycling, there would be risk of change in oxygen levels, climate, and ecosystem function.[citation needed]

Foraging

[edit]

Foraging is the process of seeking out nutrients in the environment. It may also be defined to include the subsequent use of the resources. Some organisms, such as animals and bacteria, can navigate to find nutrients, while others, such as plants and fungi, extend outward to find nutrients. Foraging may be random, in which the organism seeks nutrients without method, or it may be systematic, in which the organism can go directly to a food source.[16] Organisms are able to detect nutrients through taste or other forms of nutrient sensing, allowing them to regulate nutrient intake.[17] Optimal foraging theory is a model that explains foraging behavior as a cost–benefit analysis in which an animal must maximize the gain of nutrients while minimizing the amount of time and energy spent foraging. It was created to analyze the foraging habits of animals, but it can also be extended to other organisms.[18] Some organisms are specialists that are adapted to forage for a single food source, while others are generalists that can consume a variety of food sources.[19]

Nutrient deficiency

[edit]Nutrient deficiencies, known as malnutrition, occur when an organism does not have the nutrients that it needs. A deficiency is not the same as a nutrient inadequacy which occurs when the intake of nutrients is above the level of deficiency, but below the recommended dietary level. This may lead to hidden symptoms of nutrient deficiency that are difficult to identify.[20] Nutrient deficiency may be caused by a sudden decrease in nutrient intake or by an inability to absorb essential nutrients. Not only is malnutrition the result of a lack of necessary nutrients,[21] but it can also be a result of other illnesses and health conditions. When this occurs, an organism will adapt by reducing energy consumption and expenditure to prolong the use of stored nutrients. It will use stored energy reserves until they are depleted.[22]

A balanced diet includes appropriate amounts of all essential and non-essential nutrients. These can vary by age, weight, sex, physical activity levels, and more. A lack of just one essential nutrient can cause bodily harm, just as an overabundance can cause toxicity. The Daily Reference Values keep the majority of people from nutrient deficiencies.[23] DRVs are not recommendations but a combination of nutrient references to educate professionals and policymakers on what the maximum and minimum nutrient intakes are for the average person.[24] Food labels also use DRVs as a reference to create safe nutritional guidelines for the average healthy person.[25]

In organisms

[edit]Animal

[edit]

Animals are heterotrophs that consume other organisms to obtain nutrients. Herbivores are animals that eat plants, carnivores are animals that eat other animals, and omnivores are animals that eat both plants and other animals.[26] Many herbivores rely on bacterial fermentation to create digestible nutrients from indigestible plant cellulose, while obligate carnivores must eat animal meats to obtain certain vitamins or nutrients their bodies cannot otherwise synthesize. Animals generally have a higher requirement of energy in comparison to plants.[27] The macronutrients essential to animal life are carbohydrates, amino acids, and fatty acids.[7][28]

All macronutrients except water are required by the body for energy, however, this is not their sole physiological function. The energy provided by macronutrients in food is measured in kilocalories, usually called Calories, where 1 Calorie is the amount of energy required to raise 1 kilogram of water by 1 degree Celsius.[29]

Carbohydrates are molecules that store significant amounts of energy. Animals digest and metabolize carbohydrates to obtain this energy. Carbohydrates are typically synthesized by plants during metabolism, and animals have to obtain most carbohydrates from nature, as they have only a limited ability to generate them. They include sugars, oligosaccharides, and polysaccharides. Glucose is the simplest form of carbohydrate.[30] Carbohydrates are broken down to produce glucose and short-chain fatty acids, and they are the most abundant nutrients for herbivorous land animals.[31] Carbohydrates contain 4 calories per gram.

Lipids provide animals with fats and oils. They are not soluble in water, and they can store energy for an extended period of time. They can be obtained from many different plant and animal sources. Most dietary lipids are triglycerides, composed of glycerol and fatty acids. Phospholipids and sterols are found in smaller amounts.[32] An animal's body will reduce the amount of fatty acids it produces as dietary fat intake increases, while it increases the amount of fatty acids it produces as carbohydrate intake increases.[33] Fats contain 9 calories per gram.

Protein consumed by animals is broken down to amino acids, which would be later used to synthesize new proteins. Protein is used to form cellular structures, fluids,[34] and enzymes (biological catalysts). Enzymes are essential to most metabolic processes, as well as DNA replication, repair, and transcription.[35] Protein contains 4 calories per gram.

Much of animal behavior is governed by nutrition. Migration patterns and seasonal breeding take place in conjunction with food availability, and courtship displays are used to display an animal's health.[36] Animals develop positive and negative associations with foods that affect their health, and they can instinctively avoid foods that have caused toxic injury or nutritional imbalances through a conditioned food aversion. Some animals, such as rats, do not seek out new types of foods unless they have a nutrient deficiency.[37]

Human

[edit]Early human nutrition consisted of foraging for nutrients, like other animals, but it diverged at the beginning of the Holocene with the Neolithic Revolution, in which humans developed agriculture to produce food. The Chemical Revolution in the 18th century allowed humans to study the nutrients in foods and develop more advanced methods of food preparation. Major advances in economics and technology during the 20th century allowed mass production and food fortification to better meet the nutritional needs of humans.[38] Human behavior is closely related to human nutrition, making it a subject of social science in addition to biology. Nutrition in humans is balanced with eating for pleasure, and optimal diet may vary depending on the demographics and health concerns of each person.[39] Social determinants of health (SDOH) and structural factors drive nutrition and diet-related health disparities.[40]

Humans are omnivores that eat a variety of foods. Cultivation of cereals and production of bread has made up a key component of human nutrition since the beginning of agriculture. Early humans hunted animals for meat, and modern humans domesticate animals to consume their meat and eggs. The development of animal husbandry has also allowed humans in some cultures to consume the milk of other animals and process it into foods such as cheese. Other foods eaten by humans include nuts, seeds, fruits, and vegetables. Access to domesticated animals as well as vegetable oils has caused a significant increase in human intake of fats and oils. Humans have developed advanced methods of food processing that prevent contamination of pathogenic microorganisms and simplify the production of food. These include drying, freezing, heating, milling, pressing, packaging, refrigeration, and irradiation. Most cultures add herbs and spices to foods before eating to add flavor, though most do not significantly affect nutrition. Other additives are also used to improve the safety, quality, flavor, and nutritional content of food.[41]

Humans obtain most carbohydrates as starch from cereals, though sugar has grown in importance.[30] Lipids can be found in animal fat, butterfat, vegetable oil, and leaf vegetables, and they are also used to increase flavor in foods.[32] Protein can be found in virtually all foods, as it makes up cellular material, though certain methods of food processing may reduce the amount of protein in a food.[42] Humans can also obtain energy from ethanol, which is both a food and a drug, but it provides relatively few essential nutrients and is associated with nutritional deficiencies and other health risks.[43]

In humans, poor nutrition can cause deficiency-related diseases, such as blindness, anemia, scurvy, preterm birth, stillbirth and cretinism,[44] or nutrient-excess conditions, such as obesity[45] and metabolic syndrome.[46] Other conditions possibly affected by nutrition disorders include cardiovascular diseases,[47] diabetes,[48][49] and osteoporosis.[50] Undernutrition can lead to wasting in acute cases, and stunting of marasmus in chronic cases of malnutrition.[44]

Domesticated animal

[edit]In domesticated animals, such as pets, livestock, and working animals, as well as other animals in captivity, nutrition is managed by humans through animal feed. Fodder and forage are provided to livestock. Specialized pet food has been manufactured since 1860, and subsequent research and development have addressed the nutritional needs of pets. Dog food and cat food in particular are heavily studied and typically include all essential nutrients for these animals. Cats are sensitive to some common nutrients, such as taurine, and require additional nutrients derived from meat. Large-breed puppies are susceptible to overnutrition, as small-breed dog food is more energy dense than they can absorb.[51]

Plant

[edit]

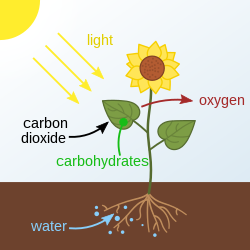

Most plants obtain nutrients through inorganic substances absorbed from the soil or the atmosphere. Carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur are essential nutrients that make up organic material in a plant and allow enzymic processes. These are absorbed ions in the soil, such as bicarbonate, nitrate, ammonium, and sulfate, or they are absorbed as gases, such as carbon dioxide, water, oxygen gas, and sulfur dioxide. Phosphorus, boron, and silicon are used for esterification. They are obtained through the soil as phosphates, boric acid, and silicic acid, respectively. Other nutrients used by plants are potassium, sodium, calcium, magnesium, manganese, chlorine, iron, copper, zinc, and molybdenum.[52]

Plants uptake essential elements from the soil through their roots and from the air (consisting of mainly nitrogen and oxygen) through their leaves. Nutrient uptake in the soil is achieved by cation exchange, wherein root hairs pump hydrogen ions (H+) into the soil through proton pumps. These hydrogen ions displace cations attached to negatively charged soil particles so that the cations are available for uptake by the root. In the leaves, stomata open to take in carbon dioxide and expel oxygen.[53] Although nitrogen is plentiful in the Earth's atmosphere, very few plants can use this directly. Most plants, therefore, require nitrogen compounds to be present in the soil in which they grow. This is made possible by the fact that largely inert atmospheric nitrogen is changed in a nitrogen fixation process to biologically usable forms in the soil by bacteria.[54]

As these nutrients do not provide the plant with energy, they must obtain energy by other means. Green plants absorb energy from sunlight with chloroplasts and convert it to usable energy through photosynthesis.[55]

Fungus

[edit]Fungi are chemoheterotrophs that consume external matter for energy. Most fungi absorb matter through the root-like mycelium, which grows through the organism's source of nutrients and can extend indefinitely. The fungus excretes extracellular enzymes to break down surrounding matter and then absorbs the nutrients through the cell wall. Fungi can be parasitic, saprophytic, or symbiotic. Parasitic fungi attach and feed on living hosts, such as animals, plants, or other fungi. Saprophytic fungi feed on dead and decomposing organisms. Symbiotic fungi grow around other organisms and exchange nutrients with them.[56]

Protist

[edit]Protists include all eukaryotes that are not animals, plants, or fungi, resulting in great diversity between them. Algae are photosynthetic protists that can produce energy from light. Several types of protists use mycelium similar to those of fungi. Protozoa are heterotrophic protists, and different protozoa seek nutrients in different ways. Flagellate protozoa use a flagellum to assist in hunting for food, and some protozoa travel via infectious spores to act as parasites.[57] Many protists are mixotrophic, having both phototrophic and heterotrophic characteristics. Mixotrophic protists will typically depend on one source of nutrients while using the other as a supplemental source or a temporary alternative when its primary source is unavailable.[58]

Prokaryote

[edit]

Prokaryotes, including bacteria and archaea, vary greatly in how they obtain nutrients across nutritional groups. Prokaryotes can only transport soluble compounds across their cell envelopes, but they can break down chemical components around them. Some lithotrophic prokaryotes are extremophiles that can survive in nutrient-deprived environments by breaking down inorganic matter.[59] Phototrophic prokaryotes, such as cyanobacteria and Chloroflexia, can engage in photosynthesis to obtain energy from sunlight. This is common among bacteria that form in mats atop geothermal springs. Phototrophic prokaryotes typically obtain carbon from assimilating carbon dioxide through the Calvin cycle.[60]

Some prokaryotes, such as Bdellovibrio and Ensifer, are predatory and feed on other single-celled organisms. Predatory prokaryotes seek out other organisms through chemotaxis or random collision, merge with the organism, degrade it, and absorb the released nutrients. Predatory strategies of prokaryotes include attaching to the outer surface of the organism and degrading it externally, entering the cytoplasm of the organism, or by entering the periplasmic space of the organism. Groups of predatory prokaryotes may forgo attachment by collectively producing hydrolytic enzymes.[61]

See also

[edit]- Liebig's law of the minimum – Growth is limited by the scarcest resource

- Nutrient density

- Nutrition analysis – Determining nutritional content of food

- Resource (biology) – Anything required by an organism to survive, grow, and reproduce

- Substrate (biology) – Surface on which a plant or animal lives

- Milan Charter 2015 Charter on Nutrition

References

[edit]- ^ Carpenter KJ (1 March 2003). "A Short History of Nutritional Science: Part 1 (1785–1885)". The Journal of Nutrition. 133 (3): 638–645. doi:10.1093/jn/133.3.638. PMID 12612130.

- ^ Stafford N (December 2010). "History: The changing notion of food". Nature. 468 (7327): S16 – S17. Bibcode:2010Natur.468S..16S. doi:10.1038/468S16a. PMID 21179078.

- ^ Mozaffarian D, Rosenberg I, Uauy R (13 June 2018). "History of modern nutrition science—implications for current research, dietary guidelines, and food policy". BMJ. 361 k2392. doi:10.1136/bmj.k2392. PMC 5998735. PMID 29899124.

- ^ Simpson & Raubenheimer 2012, p. 2.

- ^ a b Andrews 2017, pp. 70–72.

- ^ Gibney MJ, Lanham-New SA, Cassidy A, et al. (14 March 2013). Introduction to Human Nutrition. John Wiley & Sons. p. 350. ISBN 978-1-118-68470-2.

- ^ a b Wu 2017, pp. 2–4.

- ^ Andrews 2017, pp. 72–79.

- ^ Andrews 2017, p. 93.

- ^ "Diet". National Geographic. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ^ "Benefits of Healthy Eating". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 16 May 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2023.

- ^ "Religion and dietary choices". Independent Nurse. 19 September 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2023.

- ^ a b Allaby M (2015). "Nutrient cycle". A Dictionary of Ecology (5th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-179315-8. (subscription required)

- ^ "Intro to biogeochemical cycles (article)". Khan Academy. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "4.3.3: Nutrient Cycles". 29 May 2020.

- ^ Andrews 2017, pp. 83–85.

- ^ Simpson & Raubenheimer 2012, p. 36.

- ^ Andrews 2017, p. 16.

- ^ Andrews 2017, p. 98.

- ^ Kiani AK, Dhuli K, Donato K, et al. (2022). "Main nutritional deficiencies". Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene. 63 (2 Suppl 3) 93. doi:10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2022.63.2S3.2752. ISSN 2421-4248. PMC 9710417. PMID 36479498.

- ^ Mora RJ (June 1999). "Malnutrition: Organic and Functional Consequences". World Journal of Surgery. 23 (6): 530–535. doi:10.1007/PL00012343. PMID 10227920.

- ^ Mora RJ (1 June 1999). "Malnutrition: Organic and Functional Consequences". World Journal of Surgery. 23 (6): 530–535. doi:10.1007/PL00012343. PMID 10227920.

- ^ "Dietary reference values | EFSA". 5 August 2024.

- ^ "Dietary reference values | EFSA". 5 August 2024.

- ^ Nutrition Cf (13 March 2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 1 October 2023.

- ^ Wu 2017, p. 1.

- ^ National Geographic Society (21 January 2011). "Herbivore". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ "Nutrition: What Plants and Animals Need to Survive | Organismal Biology". organismalbio.biosci.gatech.edu. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "4.2: Nutrients". Biology LibreTexts. 21 December 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ a b Mann & Truswell 2012, pp. 21–26.

- ^ Wu 2017, pp. 193–194.

- ^ a b Mann & Truswell 2012, pp. 49–55.

- ^ Wu 2017, p. 271.

- ^ Mann & Truswell 2012, pp. 70–73.

- ^ Bairoch A (January 2000). "The ENZYME database in 2000". Nucleic Acids Research. 28 (1): 304–05. doi:10.1093/nar/28.1.304. PMC 102465. PMID 10592255.

- ^ Simpson & Raubenheimer 2012, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Simpson & Raubenheimer 2012, pp. 39–41.

- ^ Trüeb RM (2020). "Brief History of Human Nutrition". Nutrition for Healthy Hair. Springer. pp. 3–15. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-59920-1_2. ISBN 978-3-030-59920-1.

- ^ Mann & Truswell 2012, p. 1.

- ^ Kahlon M (1 April 2024). "Understanding and Intervening in Nutrition-Related Health Disparities". Advances in Nutrition. 15 (4): 2. doi:10.1016/j.advnut.2024.100195. ISSN 2161-8313. PMC 11031373.

- ^ Mann & Truswell 2012, pp. 409–437.

- ^ Mann & Truswell 2012, p. 86.

- ^ Mann & Truswell 2012, pp. 109–120.

- ^ a b Whitney E, Rolfes SR (2013). Understanding Nutrition (13 ed.). Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. pp. 667, 670. ISBN 978-1-133-58752-1.

- ^ "Defining Adult Overweight and Obesity". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 7 June 2021. Archived from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ "Metabolic syndrome – PubMed Health". National Center for Biotechnology Information. Archived from the original on 5 February 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Omega-3 fatty acids". Umm.edu. 5 October 2011. Archived from the original on 9 July 2008. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ What I need to know about eating and diabetes (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Diabetes Information Clearinghouse. 2007. OCLC 656826809. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2022. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ "Diabetes Diet and Food Tips: Eating to Prevent and Control Diabetes". Helpguide.org. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Dietary Supplement Fact Sheet: Vitamin D". Office of Dietary Supplements, US National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ Taylor MB (2011). "Pet Nutrition". In Davis RG (ed.). Caring for Family Pets: Choosing and Keeping Our Companion Animals Healthy. ABC-CLIO. pp. 177–194. ISBN 978-0-313-38527-8.

- ^ Mengel et al. 2001, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Mengel et al. 2001, pp. 111–135.

- ^ Lindemann W, Glover C (2003). "Nitrogen Fixation by Legumes". New Mexico State University. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013.

- ^ Mengel et al. 2001, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Charya MA (2015). "Fungi: An Overview". In Bahadur B, Rajam MV, Sahijram L, Krishnamurthy KV (eds.). Plant Biology and Biotechnology. Springer. pp. 197–215. doi:10.1007/978-81-322-2286-6_7. ISBN 978-81-322-2286-6.

- ^ Archibald JM, Simpson AG, Slamovits CH, eds. (2017). Handbook of the Protists (2nd ed.). Springer. pp. 2–4. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-28149-0. ISBN 978-3-319-28149-0. LCCN 2017945328.

- ^ Jones H (1997). "A classification of mixotrophic protists based on their behaviour". Freshwater Biology. 37 (1): 35–43. Bibcode:1997FrBio..37...35J. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2427.1997.00138.x.

- ^ Southam G, Westall F (2007). "Geology, Life and Habitability" (PDF). Treatise on Geophysics. pp. 421–437. doi:10.1016/B978-044452748-6.00164-4. ISBN 978-0-444-52748-6.

- ^ Overmann J, Garcia-Pichel F (2006). "The Phototrophic Way of Life". The Prokaryotes. pp. 32–85. doi:10.1007/0-387-30742-7_3. ISBN 978-0-387-25492-0.

- ^ Martin MO (September 2002). "Predatory prokaryotes: an emerging research opportunity". Journal of Molecular Microbiology and Biotechnology. 4 (5): 467–477. PMID 12432957.

Bibliography

[edit]- Andrews JH (2017). Comparative Ecology of Microorganisms and Macroorganisms (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4939-6897-8.

- Callahan A, Leonard H, Powell T (2022). Nutrition: Science and Everyday Application. Pressbooks.

- Mann J, Truswell AS, eds. (2012). Essentials of Human Nutrition (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-956634-1.

- Mengel K, Kirkby EA, Kosegarten H, Appel T, eds. (2001). Principles of Plant Nutrition (5th ed.). New York: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-010-1009-2. ISBN 978-94-010-1009-2.

- Simpson SJ, Raubenheimer D (2012). The Nature of Nutrition: A Unifying Framework from Animal Adaptation to Human Obesity. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-4280-3.

- Wu G (2017). Principles of Animal Nutrition. Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-351-64637-6.

Nutrition

View on GrokipediaFundamentals of Nutrition

Definition and Scope

Nutrition is the biological process by which living organisms obtain, consume, absorb, and utilize nutrients from food or other sources to support energy production, growth, tissue repair, and overall maintenance of vital functions.[2] This process encompasses the intake of dietary substances and their transformation into usable forms through metabolic pathways, ensuring the sustenance of life across diverse species.[8] A fundamental distinction in nutrition lies between autotrophic and heterotrophic modes. Autotrophs, such as plants and certain bacteria, are self-sustaining organisms that synthesize their own food from inorganic compounds, primarily through photosynthesis using sunlight, carbon dioxide, and water to produce carbohydrates.[9] In contrast, heterotrophs, including animals and fungi, cannot produce their own food and must acquire nutrients by consuming autotrophs or other heterotrophs, relying on external organic sources for energy and building blocks.[10] Nutrition plays a pivotal role in individual health by providing essential substrates for immune function, cellular repair, and disease prevention, with inadequate intake linked to weakened immunity and developmental impairments.[4] It also influences reproduction, as nutrient availability affects gamete production, fetal development, and maternal health outcomes, with balanced nutrition supporting fertility and reducing risks of complications.[11] On a broader scale, nutrition drives ecosystem dynamics through nutrient cycling, where organisms facilitate the flow and recycling of elements like carbon and nitrogen via food webs, maintaining biodiversity and environmental stability.[12] A balanced diet is one that supplies adequate energy and a variety of nutrients in proportions that meet physiological needs without excess, promoting optimal health and preventing nutrient-related disorders.[13] Malnutrition arises from imbalances in this process, manifesting as undernutrition—characterized by insufficient calorie or nutrient intake leading to conditions like wasting, stunting, and underweight—or overnutrition, involving excessive energy consumption that contributes to obesity and related metabolic diseases.[14] Nutritional status is commonly assessed using methods such as body mass index (BMI), calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared, which provides a simple indicator of underweight, normal weight, overweight, or obesity in populations.[15]Essential Nutrients

Essential nutrients are chemical substances required by organisms for normal growth, maintenance, and reproduction, but which cannot be synthesized by the organism itself in adequate amounts and thus must be obtained from external sources such as diet or the environment. This definition underscores the dependency of organisms on their surroundings to fulfill basic physiological needs, distinguishing essential nutrients from non-essential ones that can be endogenously produced.[3][16] Essential nutrients are classified into two primary categories based on the quantities required: macronutrients, needed in relatively large amounts (typically grams per day in multicellular organisms), and micronutrients, required in trace amounts (milligrams or micrograms). Macronutrients generally include carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, and water, providing the bulk of caloric intake and structural integrity, while micronutrients comprise vitamins (organic compounds) and minerals (inorganic elements) that support regulatory processes. This classification reflects the diverse scales at which these substances contribute to biological functions across organisms, from bacteria to higher plants and animals.[17][18][3] In terms of functions, essential nutrients play foundational roles in energy provision, primarily through macronutrients like carbohydrates and lipids that are oxidized to generate ATP; structural components, such as proteins for tissues and lipids for membranes; and cofactors in enzymatic reactions, where micronutrients like vitamins facilitate metabolic pathways and minerals stabilize enzyme structures. These roles ensure the integrity of cellular processes, from biosynthesis to signaling, and their absence leads to disruptions in homeostasis. For instance, water as a macronutrient is vital for solvent properties and transport, while vitamins often serve as coenzymes in redox reactions.[19][20][17] The criteria for determining essentiality involve rigorous testing, such as observing deficiency symptoms in controlled deprivation studies that are reversed upon reintroduction of the nutrient, confirming its irreplaceable role in specific biochemical pathways. Historically, this concept evolved significantly with the identification of organic essential factors in the early 20th century; Polish biochemist Casimir Funk coined the term "vitamine" in 1912 to describe these vital amines preventing diseases like beriberi and rickets, marking a shift from calorie-focused nutrition to recognition of trace organics. This period, spanning the late 19th to mid-20th centuries, saw the isolation of key vitamins through animal and human experiments, establishing the framework for modern nutrient classification.[21][22][23]Macronutrients

Macronutrients are nutrients required by the body in relatively large quantities to provide energy, support growth, and maintain essential physiological functions. They include carbohydrates, proteins, fats, and water, which together constitute the bulk of dietary intake and are measured in grams per day rather than trace amounts. These components supply calories—4 kcal per gram for carbohydrates and proteins, 9 kcal per gram for fats—and play distinct roles in metabolism, with water facilitating many of these processes without contributing energy.[3] Carbohydrates form the primary energy source for the body, structured as organic compounds containing carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen in a typical ratio of 1:2:1. They are categorized into simple forms like monosaccharides (e.g., glucose and fructose) and complex polysaccharides (e.g., starch and glycogen, linked by glycosidic bonds). Through glycolysis, carbohydrates are broken down to produce ATP, providing rapid energy for cells, while also aiding in blood glucose regulation, insulin metabolism, and cholesterol control. Common sources include grains such as brown rice, fruits like apples, vegetables like broccoli, and simple sugars from honey or fruit juices. The recommended intake is 45-65% of total daily calories, equivalent to about 200-300 grams for an average adult diet.[24][25] Proteins are composed of chains of amino acids, with nine essential ones—histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine—that the body cannot synthesize and must obtain from diet, alongside non-essential amino acids produced endogenously. They function in building and repairing tissues, synthesizing enzymes and hormones, and supporting immune responses, with nitrogen comprising about 16% of their weight for metabolic assessments. Dietary sources encompass animal products like meat, fish, eggs, and dairy, which provide complete proteins, as well as plant-based options such as legumes, cereal grains, and nuts. Requirements are determined via nitrogen balance studies, recommending 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight daily for healthy adults to maintain equilibrium, or 10-35% of total calories.[26] Fats, or lipids, encompass a diverse group including saturated fatty acids (no double bonds, e.g., palmitic acid), unsaturated types like monounsaturated (one double bond, e.g., oleic acid) and polyunsaturated fatty acids (multiple double bonds, e.g., linoleic and alpha-linolenic acids), and essential fatty acids such as omega-3 and omega-6 that cannot be produced by the body. They serve as a concentrated energy store (providing over 90% of fat mass energy), form structural components of cell membranes via phospholipids and cholesterol, and act as precursors for hormones, bile acids, and eicosanoids like prostaglandins. Key sources are oils (e.g., olive, corn, and fish oils), nuts, seeds, meats, and dairy products. Optimal intake guidelines suggest total fats at 20-35% of calories, with saturated fats limited to less than 10%, polyunsaturated fats at 6-10%, and a balanced omega-6 to omega-3 ratio (ideally around 4:1 or lower) to support cardiovascular health.[27][28] Water, often considered the quintessential macronutrient, constitutes 55-75% of body weight and is vital for nearly all physiological processes without caloric contribution. It enables hydration to maintain cellular function, facilitates the transport of nutrients and waste through blood and lymph, and supports thermoregulation via sweating and evaporation, with losses up to 2 liters per hour during intense activity. Daily needs for adults average 3.7 liters for men and 2.7 liters for women from all sources (beverages and food), varying by climate, activity, and age to prevent dehydration. Water also aids electrolyte balance by helping kidneys regulate ions like sodium and potassium, preserving plasma osmolality between 275-290 mOsm/kg for nerve and muscle function.[29][30]Micronutrients

Micronutrients are essential vitamins and minerals required in small quantities to support physiological functions, primarily acting as cofactors in enzymatic reactions, antioxidants, and regulators of cellular processes. Unlike macronutrients, they do not provide energy but are vital for metabolism, immune response, and structural integrity. Deficiencies can lead to specific disorders, while excesses may cause toxicity, highlighting the need for balanced intake.[3] Vitamins are organic compounds classified into water-soluble and fat-soluble groups based on solubility and absorption mechanisms. Water-soluble vitamins, including the B-complex (thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, pantothenic acid, pyridoxine, biotin, folate, and cobalamin) and vitamin C, function primarily as coenzymes in energy metabolism, nucleic acid synthesis, and antioxidant defense. For instance, B vitamins facilitate carbohydrate, protein, and fat catabolism, while vitamin C supports collagen formation and iron absorption as an antioxidant.[31] Fat-soluble vitamins—A, D, E, and K—are absorbed with dietary fats and stored in tissues, playing roles in vision (vitamin A as retinal in rhodopsin), bone mineralization (vitamin D regulating calcium homeostasis), cellular protection (vitamin E as a lipid peroxidation inhibitor), and hemostasis (vitamin K in gamma-carboxylation of clotting factors). Deficiencies in water-soluble vitamins often arise from poor diet or malabsorption, such as scurvy from vitamin C deficiency, characterized by bleeding gums and fatigue due to impaired collagen synthesis. Fat-soluble vitamin shortages, like rickets from vitamin D lack, result in skeletal deformities from inadequate calcium absorption. Sources include fruits and vegetables for vitamin C, leafy greens for vitamin K, and fortified foods or sunlight for vitamin D.[32] Minerals, inorganic elements, are categorized as macrominerals (needed in amounts >100 mg/day) and trace minerals (<100 mg/day), both integral to structural, regulatory, and catalytic functions. Macrominerals such as calcium and phosphorus form hydroxyapatite for bone and teeth, while sodium and potassium maintain electrolyte balance and enable nerve impulse transmission via membrane potential regulation. Trace minerals like iron and zinc serve as components of proteins and enzymes; iron is central to hemoglobin for oxygen transport, and zinc supports immune cell development and DNA synthesis. Deficiencies manifest as anemia from iron shortfall, impairing oxygen delivery, or weakened immunity from zinc deficiency. Dietary sources encompass dairy for calcium, meats for iron, and nuts for zinc, though absorption varies. Factors like phytates in grains and legumes bind iron and zinc, reducing bioavailability by forming insoluble complexes in the gut, whereas vitamin C enhances non-heme iron uptake.[31][33] Bioavailability—the fraction of a micronutrient absorbed and utilized—depends on food matrix, processing, and interactions, influencing supplementation strategies. Historical interventions like salt iodization, introduced in the U.S. in 1924, dramatically reduced goiter prevalence by addressing iodine deficiency, a trace mineral essential for thyroid hormone synthesis; Michigan's program cut rates from 38.6% to 9% within five years. Fortification of staples, such as iron in flour or vitamin A in oil, and supplementation programs have since prevented widespread deficiencies globally.[34][35] Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs), established by the National Academies, provide intake levels meeting needs of 97-98% of healthy individuals, with Tolerable Upper Intake Levels (ULs) to prevent toxicity. For example:| Micronutrient | RDA (Adult Males, 19-50 y) | RDA (Adult Females, 19-50 y) | UL (Adults) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C | 90 mg | 75 mg | 2,000 mg |

| Vitamin A | 900 µg RAE | 700 µg RAE | 3,000 µg |

| Calcium | 1,000 mg | 1,000 mg | 2,500 mg |

| Iron | 8 mg | 18 mg | 45 mg |

| Zinc | 11 mg | 8 mg | 40 mg |

_-_Purple_Leaf_Blue_(Male)_gathering_nutrients_from_bird_dropping_WLB.jpg/250px-Close_wing_posture_of_Amblypodia_anita_(Hewitson,_1862)_-_Purple_Leaf_Blue_(Male)_gathering_nutrients_from_bird_dropping_WLB.jpg)

_-_Purple_Leaf_Blue_(Male)_gathering_nutrients_from_bird_dropping_WLB.jpg/2000px-Close_wing_posture_of_Amblypodia_anita_(Hewitson,_1862)_-_Purple_Leaf_Blue_(Male)_gathering_nutrients_from_bird_dropping_WLB.jpg)