Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

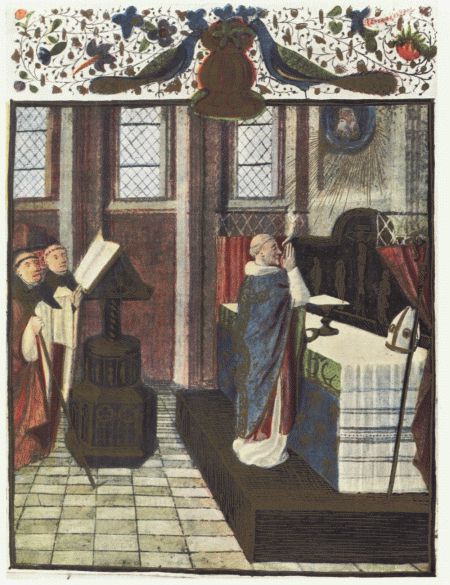

Mass (liturgy)

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on the |

| Eucharist |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Mass is the main Eucharistic liturgical service in many forms of Western Christianity. The term Mass is commonly used in the Catholic Church,[1] Western Rite Orthodoxy, Old Catholicism, and Independent Catholicism. The term is also used in many Lutheran churches,[2][3][4] as well as in some Anglican churches,[5] and on rare occasion by other Protestant churches.

Other Christian denominations may employ terms such as Divine Service or worship service (and often just "service"), rather than the word Mass.[6] For the celebration of the Eucharist in Eastern Christianity, including Eastern Catholic Churches, other terms such as Divine Liturgy, Holy Qurbana, Holy Qurobo and Badarak (or Patarag) are typically used instead.

Etymology

[edit]The English noun Mass is derived from the Middle Latin missa. The Latin word was adopted in Old English as mæsse (via a Vulgar Latin form *messa), and was sometimes glossed as sendnes (i.e. 'a sending, dismission').[7]

The Latin term missa itself was in use by the 6th century.[8] It is most likely derived from the concluding formula Ite, missa est ("Go; the dismissal is made"); missa here is a Late Latin substantive corresponding to classical missio.

Historically, however, there have been other etymological explanations of the noun missa that claim not to derive from the formula ite, missa est. Fortescue (1910) cites older, "fanciful" etymological explanations, notably a latinization of Hebrew matzâh (מַצָּה) "unleavened bread; oblation", a derivation favoured in the 16th century by Reuchlin and Luther, or Greek μύησις "initiation", or even Germanic mese "assembly".[a] The French historian Du Cange in 1678 reported "various opinions on the origin" of the noun missa "Mass", including the derivation from Hebrew matzah (Missah, id est, oblatio), here attributed to Caesar Baronius. The Hebrew derivation is learned speculation from 16th-century philology; medieval authorities did derive the noun missa from the verb mittere, but not in connection with the formula ite, missa est.[10] Thus, De divinis officiis (9th century)[11] explains the word as "a mittendo, quod nos mittat ad Deo" ("from 'sending', because it sends us towards God"),[12] while Rupert of Deutz (early 12th century) derives it from a "dismissal" of the "enmities which had been between God and men" ("inimicitiarum quæ erant inter Deum et homines").[13]

Order of the Mass

[edit]A distinction is made between texts that recur for every Mass celebration (ordinarium, ordinary), and texts that are sung depending on the occasion (proprium, proper).[14]

Catholic Church

[edit]The Catholic Church sees the Mass or Eucharist as "the source and summit of the Christian life", to which the other sacraments are oriented.[15] Remembered in the Mass are Jesus' life, Last Supper, and sacrificial death on the cross at Calvary. The ordained celebrant (priest or bishop) is understood to act in persona Christi, as he recalls the words and gestures of Jesus Christ at the Last Supper and leads the congregation in praise of God. The Mass is composed of two parts, the Liturgy of the Word and the Liturgy of the Eucharist.

Jesuit priest Rune P. Thuringer, writing in 1965, noted that "The eucharistic liturgy of the state Church of Sweden, which is Lutheran, is closer in many respects to the rite of the Roman Mass than that of any other Protestant church."[16][17] Although similar in outward appearance to the Lutheran Mass or Anglican Mass,[17][18][19] the Catholic Church distinguishes between its own Mass and theirs on the basis of what it views as the validity of the orders of their clergy, and as a result, does not ordinarily permit intercommunion between members of these Churches.[20][21] In a 1993 letter to Bishop Johannes Hanselmann of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria, Cardinal Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) affirmed that "a theology oriented to the concept of succession [of bishops], such as that which holds in the Catholic and in the Orthodox church, need not in any way deny the salvation-granting presence of the Lord [Heilschaffende Gegenwart des Herrn] in a Lutheran [evangelische] Lord's Supper".[22] The Decree on Ecumenism, produced by Vatican II in 1964, records that the Catholic Church notes its understanding that when other faith groups (such as Lutherans, Anglicans, and Presbyterians) "commemorate His death and resurrection in the Lord's Supper, they profess that it signifies life in communion with Christ and look forward to His coming in glory".[21]

Within the fixed structure outlined below, which is specific to the Roman Rite, the Scripture readings, the antiphons sung or recited during the entrance procession or at Communion, and certain other prayers vary each day according to the liturgical calendar.[23]

Traditionalist Roman Catholics use the term salvific "Sacrifice (prosphora, oblatio) of the Mass".[24]

Introductory rites

[edit]

The priest enters, with a deacon if there is one, and altar servers (who may act as crucifer, candle-bearers and thurifer). The priest makes the sign of the cross with the people and formally greets them. Of the options offered for the Introductory Rites, that preferred by liturgists would bridge the praise of the opening hymn with the Glory to God which follows.[25] The Kyrie eleison here has from early times been an acclamation of God's mercy.[26] The Penitential Act instituted by the Council of Trent is also still permitted here, with the caution that it should not turn the congregation in upon itself during these rites which are aimed at uniting those gathered as one praiseful congregation.[27][28] The Introductory Rites are brought to a close by the Collect Prayer.

Liturgy of the Word

[edit]On Sundays and solemnities, three Scripture readings are given. On other days there are only two. If there are three readings, the first is from the Old Testament (a term wider than "Hebrew Scriptures", since it includes the Deuterocanonical Books), or the Acts of the Apostles during Eastertide. The first reading is followed by a psalm, recited or sung responsorially. The second reading is from the New Testament epistles, typically from one of the Pauline epistles. A Gospel acclamation is then sung as the Book of the Gospels is processed, sometimes with incense and candles, to the ambo; if not sung it may be omitted. The final reading and high point of the Liturgy of the Word is the proclamation of the Gospel by the deacon or priest. On all Sundays and Holy Days of Obligation, and preferably at all Masses, a homily or sermon that draws upon some aspect of the readings or the liturgy itself, is then given.[29] The homily is preferably moral and hortatory.[30] Finally, the Nicene Creed or, especially from Easter to Pentecost, the Apostles' Creed is professed on Sundays and solemnities,[31] and the Universal Prayer or Prayer of the Faithful follows.[32] The designation "of the faithful" comes from when catechumens did not remain for this prayer or for what follows.

Liturgy of the Eucharist

[edit]

The Liturgy of the Eucharist begins with the preparation of the altar and gifts,[33] while the collection may be taken. This concludes with the priest saying: "Pray, brethren, that my sacrifice and yours may be acceptable to God, the almighty Father." The congregation stands and responds: "May the Lord accept the sacrifice at your hands, for the praise and glory of His name, for our good, and the good of all His holy Church."[34] The priest then pronounces the variable prayer over the gifts.

Then in dialogue with the faithful the priest brings to mind the meaning of "eucharist", to give thanks to God. A variable prayer of thanksgiving follows, concluding with the acclamation "Holy, Holy ....Heaven and earth are full of your glory. ...Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord. Hosanna in the highest."

The anaphora, or more properly "Eucharistic Prayer", follows. The oldest of the anaphoras of the Roman Rite, fixed since the Council of Trent, is called the Roman Canon, with central elements dating to the fourth century. With the liturgical renewal following the Second Vatican Council, numerous other Eucharistic prayers have been composed, including four for children's Masses. Central to the Eucharist is the Institution Narrative, recalling the words and actions of Jesus at his Last Supper, which he told his disciples to do in remembrance of him.[35] Then the congregation acclaims its belief in Christ's conquest over death, and their hope of eternal life.[36] Since the early church an essential part of the Eucharistic prayer has been the epiclesis, the calling down of the Holy Spirit to sanctify the offering and that "the unblemished sacrificial victim to be consumed in Communion may be for the salvation of those who will partake of it."[37] The priest concludes with a doxology in praise of God's work, at which the people give their Amen to the whole Eucharistic prayer.[38]

Communion rite

[edit]

All together recite or sing the "Lord's Prayer" ("Pater Noster" or "Our Father"). The priest introduces it with a short phrase and follows it up with a prayer called the embolism, after which the people respond with another doxology. The sign of peace is exchanged and then the "Lamb of God" ("Agnus Dei" in Latin) litany is sung or recited while the priest breaks the host and places a piece in the main chalice; this is known as the rite of fraction and commingling.

The priest then displays the consecrated elements to the congregation, saying: "Behold the Lamb of God, behold him who takes away the sins of the world. Blessed are those called to the supper of the Lamb," to which all respond: "Lord, I am not worthy that you should enter under my roof, but only say the word and my soul shall be healed." Then Communion is given, often with lay ministers assisting with the consecrated wine.[39] According to Catholic teaching, one should be in the state of grace, without mortal sin, to receive Communion.[40] Singing by all the faithful during the Communion procession is encouraged "to express the communicants' union in spirit"[41] from the bread that makes them one. A silent time for reflection follows, and then the variable concluding prayer of the Mass.

Concluding rite

[edit]The priest imparts a blessing over those present. The deacon or, in his absence, the priest himself then dismisses the people, choosing a formula by which the people are "sent forth" to spread the good news. The congregation responds: "Thanks be to God." A recessional hymn is sung by all, as the ministers process to the rear of the church.[42]

Western Rite Orthodox Churches

[edit]Since most Eastern Orthodox Christians use the Byzantine Rite, most Eastern Orthodox Churches call their Eucharistic service "the Divine Liturgy." However, there are a number of parishes within the Eastern Orthodox Church which use an edited version of Latin liturgical rites. Most parishes use the "Divine Liturgy of St. Tikhon" which is a revision of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, or "the Divine Liturgy of St. Gregory" which is derived from the Tridentine form of the Roman Rite Mass. These rubrics have been revised to reflect the doctrine and dogmas of the Eastern Orthodox Church. Therefore, the filioque clause has been removed, a fuller epiclesis has been added, and the use of leavened bread has been introduced.[43]

Divine Liturgy of St. Gregory

[edit]- The Preparation for Mass

- Confiteor

- Kyrie Eleison

- Gloria in excelsis deo

- Collect of the Day

- Epistle

- Gradual

- Alleluia

- Gospel

- Sermon

- Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed

- Offertory

- Dialogue

- Preface

- Sanctus

- Canon

- Lord's Prayer

- Fraction

- Agnus Dei

- Prayers before Communion

- Holy Communion

- Prayer of Thanksgiving

- Dismissal

- Blessing of the Faithful

- Last Gospel

Lutheranism

[edit]

In the Book of Concord, Article XXIV ("Of the Mass") of the Augsburg Confession (1530) begins thus:

...the Mass is retained among us, and celebrated with the highest reverence. We do not abolish the Mass but religiously keep and defend it. [...] We keep the traditional liturgical form. [...] In our churches Mass is celebrated every Sunday and on other holy days, when the sacrament is offered to those who wish for it after they have been examined and absolved (Article XXIV).

Lutheran churches often celebrate the Eucharist each Sunday (Lord's Day) in the Mass. This aligns with the Lutheran Confessions, as with the views promulgated by Martin Luther.[44] Eucharistic Ministers take the sacramental elements to the sick in hospitals and nursing homes, as well as prisons. The practice of weekly Communion is the norm in most Lutheran parishes throughout the world. The bishops and priests (pastors) of the larger Lutheran bodies have strongly encouraged the practice of weekly Mass, and daily Mass is offered in some Lutheran churches, as well as at Lutheran convents and monasteries, such as Östanbäck Monastery and Saint Augustine's House.[45][46][47]

Traditionally, in the Lutheran Churches, the Mass is celebrated ad orientem, being "oriented to the East from which the Sun of Righteousness will return".[48] Though some parishes now celebrate the Mass versus populum, the traditional liturgical posture of ad orientem is retained by many Lutheran churches.[49]

Order of the Mass

[edit]

- Introit[50]

- The Preparation for Mass[50]

- The Absolution[50]

- Prayer of Thanksgiving[50]

- Kyrie Eleison[50]

- Gloria and Laudamus[50]

- Collect of the Day[50]

- Old Testament reading[50]

- Responsorial Psalm[50]

- Epistle reading[50]

- Gradual[50]

- Alleluia[50]

- Gospel reading[50]

- Sermon[50]

- Nicene Creed[50]

- Notices[50]

- Intercessions[50]

- Offertory[50]

- Eucharistic Prayer[50]

- Lord's Prayer[50]

- Fraction[50]

- Pax[50]

- Agnus Dei[50]

- Prayers before Communion[50]

- Holy Communion[50]

- Prayer of Thanksgiving[50]

- Benedicamus Domino[50]

- Blessing of the Faithful[50]

- Dismissal[50]

Lutherans affirm that the Sacrifice of the Mass (sacrificium eucharistikon) is a sacrifice of thanksgiving and praise (sacrificia laudis):[51]

We are perfectly willing for the Mass to be understood as a daily sacrifice, provided this means the whole Mass, the ceremony and also the proclamation of the Gospel, faith, prayer, and thanksgiving. Taken together, these are the daily sacrifice of the New Testament; the ceremony was instituted because of them and ought not be separated from them. Therefore Paul says (I Cor. 11:26), “As often as you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death.” (Apology XXIV:35)[52]

Martin Luther rejected parts of the Roman Rite Mass, specifically the Roman Catholic Canon of the Mass, which, as he argued, did not conform with Hebrews 7:27. That verse contrasts the Old Testament priests, who needed to make a propitiatory sacrifice for sins on a regular basis, with the single priest Christ, who offers his body only once as a sacrifice. The theme is carried out also in Hebrews 9:26, 9:28, and 10:10. Luther composed as a replacement a revised Latin-language rite, Formula Missae, in 1523, and the vernacular Deutsche Messe in 1526.[53] The Formula Missae supplanted the Canon of the Mass with the following:

(i) Sursum Corda and preface, to 'through Christ our Lord'.

(ii) The Words of Institution, intoned.

(iii) The Sanctus and Benedictus with the elevation of the bread and the cup.[54]

The Apology of the Augsburg Confession affirmed the Greek Canon, and the Pfalz-Neuburg Church Order (1543), modeled by the Lutheran divine Philip Melanchthon includes the following Eucharistic Prayer prior to the Words of Institution:[55]

Lord Jesus Christ, thou only true Son of the living God, who hast given thy body unto bitter death for us all, and hast shed thy blood for the forgiveness of our sins, and hast bidden all thy disciples to eat that same thy body and to drink thy blood whereby to remember thy death ; we bring before thy divine Majesty these thy gifts of bread and wine and beseech thee to hallow and bless the same by thy divine grace, goodness and power and ordain [schaffen] that this bread and wine may be [sei] thy body and blood, even unto eternal life to all who eat and drink thereof.[55]

The Order of the Mass produced under the liturgical reforms of the Lutheran divine Olavus Petri, expanded the anaphora from the Formula Missae, which liturgical scholar Frank Senn states fostered "a church life that was both catholic and evangelical, embracing the whole population of the country and maintaining continuity with pre-Reformation traditions, but centered in the Bible's gospel."[55]

Scandinavian, Finnish, and some English-speaking Lutherans, use the term "Mass" for their Eucharistic service,[56] though in most German- and English-speaking churches, the terms "Divine Service", "Holy Communion, or "the Holy Eucharist" are used more frequently, though the term "Mass" enjoys usage as well.[52]

Anglicanism

[edit]

In the Anglican tradition, Mass is one of many terms for the Eucharist. More frequently, the term used is either Holy Communion, Holy Eucharist, or the Lord's Supper. Occasionally the term used in Eastern churches, the Divine Liturgy, is also used.[57] In the English-speaking Anglican world, the term used often identifies the Eucharistic theology of the person using it. "Mass" is frequently used by Anglo-Catholics.

Structure of the rite

[edit]The various Eucharistic liturgies used by national churches of the Anglican Communion have continuously evolved from the 1549 and 1552 editions of the Book of Common Prayer, both of which owed their form and contents chiefly to the work of Thomas Cranmer, who in about 1547 had rejected the medieval theology of the Mass.[58] Although the 1549 rite retained the traditional sequence of the Mass, its underlying theology was Cranmer's and the four-day debate in the House of Lords during December 1548 makes it clear that this had already moved far beyond traditional Catholicism.[59] In the 1552 revision, this was made clear by the restructuring of the elements of the rite while retaining nearly all the language so that it became, in the words of an Anglo-Catholic liturgical historian (Arthur Couratin) "a series of communion devotions; disembarrassed of the Mass with which they were temporarily associated in 1548 and 1549".[58] Some rites, such as the 1637 Scottish rite and the 1789 rite in the United States, went back to the 1549 model.[60] From the time of the Elizabethan Settlement in 1559 the services allowed for a certain variety of theological interpretation. Today's rites generally follow the same general five-part shape.[61] Some or all of the following elements may be altered, transposed or absent depending on the rite, the liturgical season and use of the province or national church:

- Gathering: Begins with a Trinitarian-based greeting or seasonal acclamation ("Blessed be God: Father, Son and Holy spirit. And Blessed be his kingdom, now and forever. Amen").[62] Then the Kyrie and a general confession and absolution follow. On Sundays outside Advent and Lent and on major festivals, the Gloria in Excelsis Deo is sung or said. The entrance rite then concludes with the collect of the day.

- Proclaiming and Hearing the Word: Usually two to three readings of Scripture, one of which is always from the Gospels, plus a psalm (or portion thereof) or canticle between the lessons. This is followed by a sermon or homily; the recitation of one of the Creeds, viz., the Apostles' or Nicene, is done on Sundays and feasts.

- The Prayers of the People: Quite varied in their form.

- The Peace: The people stand and greet one another and exchange signs of God's peace in the name of the Lord. It functions as a bridge between the prayers, lessons, sermon and creeds to the Communion part of the Eucharist.

- The Celebration of the Eucharist: The gifts of bread and wine are brought up, along with other gifts (such as money or food for a food bank, etc.), and an offertory prayer is recited. Following this, a Eucharistic Prayer (called "The Great Thanksgiving") is offered. This prayer consists of a dialogue (the Sursum Corda), a preface, the sanctus and benedictus, the Words of Institution, the Anamnesis, an Epiclesis, a petition for salvation, and a Doxology. The Lord's Prayer precedes the fraction (the breaking of the bread), followed by the Prayer of Humble Access or the Agnus Dei and the distribution of the sacred elements (the bread and wine).

- Dismissal: There is a post-Communion prayer, which is a general prayer of thanksgiving. The service concludes with a Trinitarian blessing and the dismissal.

The liturgy is divided into two main parts: The Liturgy of the Word (Gathering, Proclaiming and Hearing the Word, Prayers of the People) and the Liturgy of the Eucharist (together with the Dismissal), but the entire liturgy itself is also properly referred to as the Holy Eucharist. The sequence of the liturgy is almost identical to the Roman Rite, except the Confession of Sin ends the Liturgy of the Word in the Anglican rites in North America, while in the Roman Rite (when used) and in Anglican rites in many jurisdictions the Confession is near the beginning of the service.

Special Masses

[edit]The Anglican tradition includes separate rites for nuptial, funeral, and votive Masses. The Eucharist is an integral part of many other sacramental services, including ordination and Confirmation.

Ceremonial

[edit]Some Anglo-Catholic parishes use Anglican versions of the Tridentine Missal, such as the English Missal, The Anglican Missal, or the American Missal, for the celebration of Mass, all of which are intended primarily for the celebration of the Eucharist, or use the order for the Eucharist in Common Worship arranged according to the traditional structure, and often with interpolations from the Roman Rite. In the Episcopal Church (United States), a traditional-language, Anglo-Catholic adaptation of the 1979 Book of Common Prayer has been published (An Anglican Service Book).

All of these books contain such features as meditations for the presiding celebrant(s) during the liturgy, and other material such as the rite for the blessing of palms on Palm Sunday, propers for special feast days, and instructions for proper ceremonial order. These books are used as a more expansively Catholic context in which to celebrate the liturgical use found in the Book of Common Prayer and related liturgical books. In England supplementary liturgical texts for the proper celebration of Festivals, Feast days and the seasons is provided in Common Worship; Times and Seasons (2013), Festivals (Common Worship: Services and Prayers for the Church of England) (2008) and Common Worship: Holy Week and Easter (2011).

These are often supplemented in Anglo-Catholic parishes by books specifying ceremonial actions, such as A Priest's Handbook by Dennis G. Michno, Ceremonies of the Eucharist by Howard E. Galley, Low Mass Ceremonial by C. P. A. Burnett, Ritual Notes by E.C.R. Lamburn, and The Parson's Handbook (Percy Dearmer). In Evangelical Anglican parishes, the rubrics detailed in the Book of Common Prayer are considered normative.

Methodism

[edit]

The celebration of the "Mass" in Methodist churches, commonly known as the Service of the Table, is based on The Sunday Service of 1784, a revision of the liturgy of the 1662 Book of Common Prayer authorized by John Wesley.[63] The use of the term "Mass" is very rare in Methodism. The terms "Holy Communion", "Lord's Supper", and to a lesser extent "Eucharist" are far more typical.

The celebrant of a Methodist Eucharist must be an ordained or licensed minister.[64] In the Free Methodist Church, the liturgy of the Eucharist, as provided in its Book of Discipline, is outlined as follows:[65]

- The Invitation: You who truly and earnestly repent of your sins, who live in love and peace with your neighbors and who intend to lead a new life, following the commandments of God and walking in His holy ways, draw near with faith, and take this holy sacrament to your comfort; and humbly kneeling, make your honest confession to Almighty God.

- General Confession

- Lord's Prayer

- Affirmation of Faith

- Collect

- Sanctus

- Prayer of Humble Access

- Prayer of Consecration of the Elements

- Benediction[65]

Methodist services of worship, post-1992, reflect the ecumenical movement and Liturgical Movement, particularly the Methodist Mass, largely the work of theologian Donald C. Lacy.[66]

Calendrical usage

[edit]The English suffix -mas (equivalent to modern English "Mass") can label certain prominent (originally religious) feasts or seasons based on a traditional liturgical year. For example:

See also

[edit]- Asperges

- Blue Mass

- Chantry

- Eucharistic theology

- Gold Mass

- Liturgical reforms of Pope Pius XII

- Mass (music)

- Mass in the Catholic Church

- Mass of Paul VI

- Origin of the Eucharist

- Papal Mass

- Pontifical High Mass

- Red Mass

- Requiem Mass

- Roman Missal

- Sacraments of the Catholic Church

- Solemn Mass

- Suffrage Mass (Votive mass for souls who are in purgatory)

Notes

[edit]- ^ The Germanic word is likely itself an early loan of the Latin mensa, "table". "The origin and first meaning of the word, once much discussed, is not really doubtful. We may dismiss at once such fanciful explanations as that missa is the Hebrew missah ("oblation" — so Reuchlin and Luther), or the Greek myesis ("initiation"), or the German Mess ("assembly", "market"). Nor is it the participle feminine of mittere, with a noun understood ("oblatio missa ad Deum", "congregatio missa", i.e., dimissa.[9]

References

[edit]- ^ John Trigilio, Kenneth Brighenti (2 March 2007). The Catholicism Answer Book. Sourcebooks, Inc.

The term "Mass", used for the weekly Sunday service in Catholic churches as well as services on Holy Days of Obligation, derives its meaning from the Latin term Missa.

- ^ DeGarmeaux, Mark E. (1995). "O Come, Let Us Worship! I. The Church Service II. The Church Song A Study in Lutheran Liturgy and Hymnody presented to the 78th Annual Convention of the Evangelical Lutheran Synod". Bethany Lutheran College. Retrieved 5 October 2024.

The basic structure of the Western liturgy is generally called the Mass, even in Lutheran countries. Our Scandinavian brothers and sisters still use the term High Mass (Høimesse) for the Communion Service. Luther called his two services: the German Mass and the Formula of the Mass. Bach and other Lutheran composers (such as Hassler and Pedersøn) wrote masses or parts of masses for use in Lutheran churches. Other Lutheran composers who wrote works for use within the Divine Service include Walter, Schütz, Scheidt, Schein, Buxtehude, Pachelbel, Praetorius, Walther, Telemann, Zachau, Mendelssohn, Brahms, Bender, Distler, Pepping, Micheelsen, Nystedt, and many others.

- ^ "Article XXIV (XII): Of the Mass". Book of Concord. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ Joseph Augustus Seiss (1871). Ecclesia Lutherana: a brief survey of the Evangelical Lutheran Church. Lutheran Book Store.

Melancthon, the author of the Augsburg Confession, states, that he uses the words Mass and the Lord's Supper as convertible terms: 'The Mass, as they call it, or, with the Apostle Paul, to speak more accurately, the celebration of the Lord's Supper,' &c. The Evangelical Princes, in their protest at the Diet of Spires, April 19th, 1529, say, 'Our preachers and teachers have attacked and utterly confuted the popish Mass, with holy, invincible, sure Scripture, and in its place raised up again the precious, priceless SUPPER OF OUR DEAR LORD AND SAVIOUR JESUS CHRIST, which is called THE EVANGELICAL MASS. This is the only Mass founded in the Scriptures of God, in accordance with the plain and incontestable institution of the Saviour.'

- ^ Seddon, Philip (1996). "Word and Sacrament". In Bunting, Ian (ed.). Celebrating the Anglican Way. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 100.

- ^ Brad Harper, Paul Louis Metzger (1 March 2009). Exploring Ecclesiology. Brazos Press. ISBN 9781587431739.

Luther also challenged the teaching that Christ is sacrificed at the celebration of the mass. Contrary to popular Protestant opinion, Magisterial Roman Catholic teaching denies that Christ is, in the Mass, sacrificed time and time again. According to The Catechism of the Catholic Church, 'The Eucharist is thus a sacrifice because it re-presents (makes present) the sacrifice of the cross, because it is its memorial and because it applies its fruit.'

- ^ Bosworth-Toller, s.v. sendness (citing Wright, Vocabularies vol. 2, 1873), "mæsse" (citing Ælfric of Eynsham).

- ^ It is used by Caesarius of Arles (e.g. Regula ad monachos, PL 67, 1102B Omni dominica sex missas facite). Before this, it occurs singularly in a letter attributed to Saint Ambrose (d. 397), Ego mansi in munere, missam facere coepi (ep. 20.3, PL 16, 0995A ). F. Probst, Liturgie der drei ersten christlichen Jahrhunderte, 1870, 5f.). "the fragment in Pseudo-Ambrose, 'De sacramentis' (about 400. Cf. P.L., XVI, 443), and the letter of Pope Innocent I (401–17) to Decentius of Eugubium (P.L., XX, 553). In these documents we see that the Roman Liturgy is said in Latin and has already become in essence the rite we still use." (Fortescue 1910).

- ^ Diez, "Etymol. Wörterbuch der roman. Sprachen", 212, and others). Fortescue, A. (1910). Liturgy of the Mass. In The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ De vocabuli origine variæ sunt Scriptorum sententiæ. Hanc enim quidam, ut idem Baronius, ab Hebræo Missah, id est, oblatio, arcessunt : alii a mittendo, quod nos mittat ad Deum Du Cange, et al., Glossarium mediae et infimae latinitatis, éd. augm., Niort : L. Favre, 1883‑1887, t. 5, col. 412b, s.v. 4. missa.

- ^ De divinis officiis, formerly attributed to Alcuin but now dated to the late 9th or early 10th century, partly based on the works of Amalarius and Remigius of Auxerre. M.-H. Jullien and F. Perelman, Clavis Scriptorum Latinorum Medii Aevii. Auctores Galliae 735–987. II: Alcuin, 1999, 133ff.; R. Sharpe, A Handlist of the Latin Writers of Great Britain and Ireland before 1540 (1997, p. 45) attributes the entire work to Remigius.

- ^ In Migne, PL 101: Alcuinus Incertus, De divinis officiis, caput XL, De celebratione missae et eius significatione (1247A)

- ^ This explanation is attributed by Du Cange to Gaufridus S Barbarae in Neustria (Godfrey of Saint Victor, fl. 1175), but it is found in the earlier De divinis officiis by Rupert of Deutz (Rupertus Tuitiensis), caput XXIII, De ornatu altaris vel templi: Sacrosanctum altaris ministerium idcirco, ut dictum est, missa dicitur, quia ad placationem inimicitiarum, quae erant inter Deum et homines, sola valens et idonea mittitur legatio. PL 170, 52A.

- ^ "Mass: Music". Encyclopedia Britannica. 11 October 2007. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ "Catechism of the Catholic Church – IntraText". www.vatican.va. Retrieved 2020-06-22.

- ^ Rune P. Thuringer (11 March 1965). "Swedish Lutheran Liturgy Close to Rome's". The Catholic Advocate. Retrieved 25 May 2025.

- ^ a b Manos, John K. (2024). "Lutheranism". EBSCO Information Services. Retrieved 10 June 2025.

Luther was an Augustine monk and teacher at the University of Wittenberg in Germany. His initial effort was not to create a schism within the Roman Catholic Church; he originally only wanted to reform some Church practices and theological beliefs. Thus, the Reformation inspired by Luther was very conservative; the original Lutherans sought to retain Roman Catholic elements to the greatest possible extent. As a result, Lutheran worship is more similar to the Roman Catholic style of worship than any other Protestant church. ... In practice, Lutheran worship bears a closer resemblance to Roman Catholic services than it does to most other Protestant denominations. Luther did not seek to reject the Roman Catholic Church but to reform it. Many aspects of Lutheran worship are quite similar to Catholic services, and generally speaking, Roman Catholics will feel a greater familiarity with Lutheran practices than most other Protestants.

- ^ Herl, Joseph (1 July 2004). Worship Wars in Early Lutheranism. Oxford University Press. p. 35. ISBN 9780195348309.

There is evidence that the late sixteenth-century Catholic mass as held in Germany was quite similar in outward appearance to the Lutheran mass

- ^ Bahr, Ann Marie B. (1 January 2009). Christianity. Infobase Publishing. p. 66. ISBN 9781438106397.

Anglicans worship with a service that may be called either Holy Eucharist or the Mass. Like the Lutheran Eucharist, it is very similar to the Catholic Mass.

- ^ Dimock, Giles (2006). 101 Questions and Answers on the Eucharist. Paulist Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780809143658.

Thus Anglican Eucharist is not the same as Catholic Mass or the Divine Liturgy celebrated by Eastern Catholics or Eastern Orthodox. Therefore Catholics may not receive at an Anglican Eucharist.

- ^ a b "Unitatis Redintegratio (Decree on Ecumenism), Section 22". Vatican. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

Though the ecclesial Communities which are separated from us lack the fullness of unity with us flowing from Baptism, and though we believe they have not retained the proper reality of the eucharistic mystery in its fullness, especially because of the absence of the sacrament of Orders, nevertheless when they commemorate His death and resurrection in the Lord's Supper, they profess that it signifies life in communion with Christ and look forward to His coming in glory. Therefore the teaching concerning the Lord's Supper, the other sacraments, worship, the ministry of the Church, must be the subject of the dialogue.

- ^ Rausch, Thomas P. (2005). Towards a Truly Catholic Church: An Ecclesiology for the Third Millennium. Liturgical Press. p. 212. ISBN 9780814651872.

- ^ Order of the Mass.

- ^ Sacrifice of the Mass, Catholic Encyclopedia

- ^ Grigassy, Daniel (1991). New Dictionary of Sacramental Worship. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press. pp. 944f. ISBN 9780814657881.

- ^ Pecklers, Keith (2010). The Genius of the Roman Rite. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814660218.

- ^ Leon-Dufour, Xavier (1988). Sharing the Eucharist Bread: The Witness of the New Testament Xavier Leon-Dufour. Continuum. ISBN 978-0225665321.

- ^ Weil, Louis (1991). New Dictionary of Sacramental Worship. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press. pp. 949ff. ISBN 9780814657881.

- ^ GIRM, paragraph 66

- ^ "Homily". The Catholic Encyclopedia (1910).

- ^ GIRM, paragraph 68

- ^ GIRM, paragraph 69

- ^ GIRM, paragraph 73

- ^ Mass as the renovation of Christ Passover's sacrifice on the altar is a concept expressed not solely by the Tridentine Mass, but also by the Second Vatican Council. Quote: "As often as the sacrifice of the cross in which Christ our Passover was sacrificed, is celebrated on the altar, the work of our redemption is carried on, and, in the sacrament of the eucharistic bread, the unity of all believers who form one body in Christ is both expressed and brought about. All men are called to this union with Christ, who is the light of the world, from whom we go forth, through whom we live, and toward whom our whole life strains." (Lumen Gentium, n°. 3).

- ^ Luke 22:19; 1 Corinthians 11:24–25

- ^ GIRM, paragraph 151

- ^ GIRM, paragraph 79c

- ^ Jungmann, SJ, Josef (1948). Mass of the Roman Rite (PDF). pp. 101–259.

- ^ GIRM, paragraph 160

- ^ Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church # 291. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ GIRM, paragraph 86

- ^ Catholic Sacramentary (PDF). ICEL. 2010.

- ^ "Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America". www.antiochian.org. Retrieved 2020-06-22.

- ^ Preus, Klemet. "Communion Every Sunday: Why?". Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ Wieting, Kenneth (23 November 2020). "Are You Fanatical about the Lord's Supper?". The Lutheran Witness. Retrieved 27 December 2024.

- ^ "Monastic Life". Saint Augustine's House. 2025. Retrieved 18 May 2025.

Following the Benedictine Rule, seven separate liturgical offices plus the Eucharist are observed each day.

- ^ "Why and how do we move to weekly communion?" (PDF). Evangelical Lutheran Church of America. 2018. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ "The Direction of Christian Worship". Christ Lutheran Church. 30 April 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ Ruff, Anthony (11 August 2016). "The Worst Reasons for Ad Orientem". The Catholic Herald. Archived from the original on 25 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af "The Eucharist also called Holy Communion (High Mass)". Church of Sweden. 2007. Archived from the original on 4 July 2007. Retrieved 19 May 2025.

- ^ "The Mystery of the Church: D. The Holy Eucharist in the Life of the Church" (PDF). Bratislava: Lutheran World Federation. 2006. p. 1.

- ^ a b Webber, David Jay (1992). "Why is the Lutheran Church a Liturgical Church?". Bethany Lutheran College. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Reuther, Thomas (1952-06-01). "The Background and Objectives of Luther's Formula Missae and Deutsche Messe". Bachelor of Divinity.

- ^ Spinks, Bryan D. (1975). Luther and the Canon of the Mass. Liturgical Review. p. 36.

- ^ a b c Bradshaw, Paul F.; Johnson, Maxwell E. (2012). The Eucharistic Liturgies: Their Evolution and Interpretation. Liturgical Press. p. 250-251. ISBN 978-0-8146-6240-3.

- ^ Hope, Nicholas (1995). German and Scandinavian Protestantism 1700 to 1918. Oxford University Press, Inc. p. 18. ISBN 0-19-826994-3. Retrieved November 19, 2011.; see also Deutsche Messe

- ^ "The Catechism (1979 Book of Common Prayer): The Holy Eucharist". Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ^ a b MacCulloch, Diarmaid (1996). Thomas Cranmer. London: Yale UP. p. 412.

- ^ MacCulloch, Diarmaid (1996). Thomas Cranmer. London: Yale UP. pp. 404–8 & 629.

- ^ Neill, Stephen (1960). Anglicanism. London: Penguin. p. 152,3.

- ^ Seddon, Philip (1996). "Word and Sacrament". In Bunting, Ian (ed.). Celebrating the Anglican Way. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 107,8.

- ^ Book of Common Prayer p. 355 Holy Eucharist Rite II

- ^ Westerfield Tucker, Karen B. (2006). "North America". In Wainwright, Geoffrey; Westerfield Tucker, Karen B. (eds.). The Oxford History of Christian Worship. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 602. ISBN 9780195138863.

- ^ Beckwith, R.T. Methodism and the Mass. Church Society. p. 116.

- ^ a b David W. Kendall; Barbara Fox; Carolyn Martin Vernon Snyder, eds. (2008). 2007 Book of Discipline. Free Methodist Church. pp. 219–223.

- ^ Carpenter, Marian (2013). "Donald C. Lacy Collection: 1954 – 2011" (PDF). Indiana Historical Society. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

Lacy also published fourteen books and pamphlets. His first pamphlet, Methodist Mass (1971), became a model for current United Methodist liturgical expression. Lacy's goal was to make ecumenism a reality by blending the United Methodist Order for the Administration of the Sacrament of the Lord's Supper or Holy Communion and "The New Order of Mass" in the Roman Catholic Church.

Sources

[edit]- The General Instruction of the Roman Missal (PDF). Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops Publication Service. 2011. ISBN 978-0-88997-655-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 25, 2012. Retrieved November 19, 2011. (GIRM)

Further reading

[edit]- Balzaretti, C., (2000). Missa: storia di una secolare ricerca etimologica ancora aperta. Edizioni Liturgiche

- Baldovin, SJ, John F., (2008). Reforming the Liturgy: A Response to the Critics. The Liturgical Press.

- Berington, Joseph (1830). . The Faith of Catholics: confirmed by Scripture, and attested by the Fathers of the five first centuries of the Church, Volume 1. Jos. Booker.

- Bugnini, Annibale (Archbishop), (1990). The Reform of the Liturgy 1948–1975. The Liturgical Press.

- Donghi, Antonio, (2009). Words and Gestures in the Liturgy. The Liturgical Press.

- Foley, Edward. From Age to Age: How Christians Have Celebrated the Eucharist, Revised and Expanded Edition. The Liturgical Press.

- Fr. Nikolaus Gihr (1902). The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass: Dogmatically, Liturgically, and Ascetically Explained. St. Louis: Freiburg im Breisgau. OCLC 262469879. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- Johnson, Lawrence J., (2009). Worship in the Early Church: An Anthology of Historical Sources. The Liturgical Press.

- Jungmann, Josef Andreas, (1948). Missarum Sollemnia. A genetic explanation of the Roman Mass (2 volumes). Herder, Vienna. First edition, 1948; 2nd Edition, 1949, 5th edition, Herder, Vienna-Freiburg-Basel, and Nova & Vetera, Bonn, 1962, ISBN 3-936741-13-1.

- Marini, Piero (Archbishop), (2007). A Challenging Reform: Realizing the Vision of the Liturgical Renewal. The Liturgical Press.

- Martimort, A.G. (editor). The Church At Prayer. The Liturgical Press.

- Stuckwisch, Richard, (2011). Philip Melanchthon and the Lutheran Confession of Eucharistic Sacrifice. Repristination Press.

External links

[edit]Present form of the Roman Rite

- The Order of Mass

- Fr. Larry Fama's Instructional Mass Archived 2011-07-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Today's Mass readings (New American Bible version)

- The Readings of the Mass (Jerusalem Bible version)

- Mass Readings (text in official Lectionary for Ireland, Australia, Britain, New Zealand etc.)

Tridentine Mass

Lutheran Mass

- The Church of Sweden Service Book including the orders for High and Low Mass

- Text of the Lutheran Mass in English

Anglican Holy Communion