Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bishop

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

A bishop is an ordained member of the clergy who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution. In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance and administration of dioceses. The role or office of the bishop is called episcopacy or the episcopate. Organisationally, several Christian denominations utilise ecclesiastical structures that call for the position of bishops, while other denominations have dispensed with this office, seeing it as a symbol of power. Bishops have also exercised political authority within their dioceses.

Traditionally, bishops claim apostolic succession and the historic episcopacy, a direct historical lineage dating back to the original Twelve Apostles or Saint Paul. The bishops are by doctrine understood as those who possess the full priesthood given by Jesus Christ, and therefore may ordain other clergy, including other bishops.[1] A person ordained as a deacon, priest (i.e. presbyter), and then bishop is understood to hold the fullness of the ministerial priesthood, given responsibility by Christ to govern, teach and sanctify the Body of Christ (the Christian Church). Priests, deacons and lay ministers co-operate and assist their bishops in pastoral ministry.

Some Pentecostal and other Protestant denominations have bishops who oversee congregations, though they do not necessarily claim apostolic succession, with exception to those Pentecostals and Charismatics affiliated to churches founded by J. Delano Ellis and Paul S. Morton.

Etymology and terminology

[edit]The English word bishop derives, via Latin episcopus, Old English biscop, and Middle English bisshop, from the Greek word ἐπίσκοπος, epískopos, meaning "overseer" or "supervisor".[2] Greek was the language of the early Christian church,[3] but the term epískopos did not originate in Christianity: it had been used in Greek for several centuries before the advent of Christianity.[2]

The English words priest and presbyter both derive, via Latin, from the Greek word πρεσβύτερος, presbýteros, meaning "elder" or "senior", and not originally referring to priesthood.[4]

In the early Christian era the two terms were not always clearly distinguished, but epískopos is used in the sense of the order or office of bishop, distinct from that of presbýteros, in the writings attributed to Ignatius of Antioch in the second century.[3]

Christian episcopal development

[edit]The earliest organization of the Church in Jerusalem was, according to most scholars, similar to that of Jewish synagogues, but it had a council or college of ordained presbyters (πρεσβύτεροι, 'elders'). In Acts 11:30[5] and Acts 15:22,[6] a collegiate system of government in Jerusalem is chaired by James the Just, according to tradition the first bishop of the city. In Acts 14:23,[7] the Apostle Paul ordains presbyters in churches in Anatolia.[8] The word presbyter was not yet distinguished from overseer (ἐπίσκοπος, episkopos, later used exclusively to mean bishop), as in Acts 20:17,[9] Titus 1:5–7[10] and 1 Peter 5:1.[11][a][b] The earliest writings of the Apostolic Fathers, the Didache and the First Epistle of Clement, for example, show the church used two terms for local church offices—presbyters (seen by many as an interchangeable term with episkopos or overseer) and deacon.

In the First Epistle to Timothy and Epistle to Titus in the New Testament a more clearly defined episcopate can be seen. Both letters state that Paul had left Timothy in Ephesus and Titus in Crete to oversee the local church.[15][16] Paul commands Titus to ordain presbyters/bishops and to exercise general oversight. John Zizioulas argues that "The task of the Bishop was from the beginning principally liturgical, consisting in the offering of the Divine Eucharist."[17] The authorship of both those letters is questioned by many scholars in the field and the question whether they reflect a first or second century structure of church hierarchy is among the arguments used in the debate as to their authenticity.

Early sources are unclear but various groups of Christian communities may have had the bishop surrounded by a group or college functioning as leaders of the local churches.[18][19] Eventually the head or "monarchic" bishop came to rule more clearly,[20] and all local churches would eventually follow the example of the other churches and structure themselves after the model of the others with the one bishop in clearer charge,[18] though the role of the body of presbyters remained important.[20]

Apostolic Fathers

[edit]

Around the end of the 1st century, the early church's organization became clearer in historical documents.[citation needed] In the works of the Apostolic Fathers, and Ignatius of Antioch in particular, the role of the episkopos, or bishop, became more important or, rather, already was very important and being clearly defined. While Ignatius of Antioch offers the earliest clear description of monarchial bishops (a single bishop over all house churches in a city)[c] he is an advocate of monoepiscopal structure rather than describing an accepted reality. To the bishops and house churches to which he writes, he offers strategies on how to pressure house churches who do not recognize the bishop into compliance. Other contemporary Christian writers do not describe monarchial bishops, either continuing to equate them with the presbyters or speaking of episkopoi (bishops, plural) in a city.

Clement of Alexandria (end of the 2nd century) writes about the ordination of a certain Zachæus as bishop by the imposition of Simon Peter Bar-Jonah's hands. The words bishop and ordination are used in their technical meaning by the same Clement of Alexandria.[22] The bishops in the 2nd century are defined also as the only clergy to whom the ordination to priesthood (presbyterate) and diaconate is entrusted: "a priest (presbyter) lays on hands, but does not ordain." (cheirothetei ou cheirotonei).[23]

At the beginning of the 3rd century, Hippolytus of Rome describes another feature of the ministry of a bishop, which is that of the "Spiritum primatus sacerdotii habere potestatem dimittere peccata": the primate of sacrificial priesthood and the power to forgive sins.[24]

Canonical age

[edit]

As the bishop's role further developed into the 4th century, the First Council of Nicaea decreed that bishops should be ordained by at least three others.[25] Age requirements for episcopal ordination or consecration were neither universal nor fixed in early Christian churches.[26] It was, however, universally required that a bishop be male.

Lacking a definitive ecumenical age requirement for holy orders—between the early ecumenical councils of the Great and imperial Roman churches, and after schism into the Latin and Greek churches—young men had been ordained, appointed, and/or enthroned as bishops, some as young as 5.[27]

Notable younger Latin and Greek bishops have included: Hugh Vermandois (5); Luis Antonio Jaime de Borbón y Farnesio (8); Guido Ascanio Sforza di Santa Fiora (9); Benedict IX (11-20); Karol Ferdynand Vasa (11); Alexander Stewart (11); Niccolò Caetani (13); Bruno von Bayern (14); Odo of Bayeux (14); Alessandro Farnese (14); Cesare Borgia (15); Clemens August (15); Ranuccio Farnese (16); Alfonso Carafa (16); James II of Cyprus (16) Theophylact (16); Ippolito de' Medici (17); Diomede Carafa (19); Stephen I (19); Luis de Milà y de Borja (21); Nicolas de Besse (21); Clemente Grosso della Rovere (21); Niccolò Gaddi (22); Juan de Borja Lanzol de Romaní, el menor (24); Gabriele Condulmer (later Eugene IV, aged 24) of Rome;[28] Ludovico Ludovisi (25); Giovanni Michiel (25); Charles Borromeo (25); Pietro Riario (26); Mark Sittich von Hohenems Altemps (26); Jošt Rožmberk (26); Giuliano della Rovere (later Julius II, aged 27); Bonifazio Bevilacqua Aldobrandini (27); Philipp Ludwig von Sinzendorf (27); Pedro Luis de Borja Lanzol de Romaní (27); and Gerhard II Lippe (29). Throughout the Church of the East, other notable younger bishops have included: Shimun XXIII Eshai (12);[29] Shimun XIX Benyamin (16);[30] Yohannan VIII Hormizd (16); Sargis Yosip (17);[31] Shimun XVII Abraham (20);[32] and Yosip Khnaninsho (22).[33]

During the Catholic Church's Council of Trent, the Holy See dogmatically mandated a minimum canonical age of 30 for the episcopacy.[26] The Eastern Orthodox Church would also impose a minimum age of 30 for the priesthood.[34] The Coptic Orthodox have adopted a minimum canonical age of at least 28 for the priesthood, including its specialized ministries leading to the chorepiscopacy.[35] For the office of bishop, the Eastern Orthodox Church imposed a minimum canonical age of 35.[36][37][38] Overall, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, the Assyrian Church of the East and Protestantism have not established a universal, canonical age.

During the 20th century, the Holiness-Pentecostal Church of God in Christ elevated Clarence Leslie Morton Jr. (born 1942) into the episcopacy at the age of 20 in 1962.[39] J. Delano Ellis (born 1944), co-founder of the Joint College of African-American Pentecostal Bishops, was also elevated as bishop at the age of 26 in 1970.[40][41]

Christian bishops and civil government

[edit]The efficient organization of the Roman Empire became the template for the organisation of the Great Church in the 4th century, particularly after Constantine's Edict of Milan. As the church moved from the shadows of privacy into the public forum it acquired land for churches, burials and clergy. In 391, Theodosius I decreed that any land that had been confiscated from the church by Roman authorities be returned.[42]

The most usual term for the geographic area of a bishop's authority and ministry, the diocese, began as part of the structure of the Roman Empire under Diocletian. As Roman authority began to fail in the western portion of the empire, the church took over much of the civil administration.[43] This can be clearly seen in the ministry of two popes: Pope Leo I in the 5th century, and Pope Gregory I in the 6th century. Both of these men were statesmen and public administrators in addition to their role as Christian pastors, teachers and leaders. In the Eastern churches, latifundia entailed to a bishop's see were much less common, the state power did not collapse the way it did in the West, and thus the tendency of bishops acquiring civil power was much weaker than in the West. However, the role of Western bishops as civil authorities, often called prince bishops, continued throughout much of the Middle Ages.[44]

Bishops holding political office

[edit]

As well as being archchancellors of the Holy Roman Empire after the 9th century, bishops generally served as chancellors to medieval monarchs, acting as head of the justiciary and chief chaplain. The Lord Chancellor of England was almost always a bishop up until the dismissal of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey by Henry VIII.[45] Similarly, the position of Kanclerz in the Polish kingdom was always held by a bishop until the 16th century.[citation needed]

In modern times, the principality of Andorra is headed by Co-Princes of Andorra, one of whom is the Bishop of Urgell and the other, the sitting President of France, an arrangement that began with the Paréage of Andorra (1278), and was ratified in the 1993 constitution of Andorra.[46]

The office of the Papacy is inherently held by the sitting Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome.[47][48] Though not originally intended to hold temporal authority, since the Middle Ages the power of the Roman papacy gradually expanded deep into the secular realm and for centuries the sitting Bishop of Rome was the most powerful governmental office in Central Italy.[49] In modern times, the Pope of Rome is also the sovereign Prince of Vatican City, an internationally recognized micro-state located entirely within the city of Rome.[50][51][52][53]

In France, prior to the Revolution, representatives of the clergy—in practice, bishops and abbots of the largest monasteries—comprised the First Estate of the Estates-General. This role was abolished after separation of church and state was implemented during the French Revolution.[54]

In the 21st century, the more senior bishops of the Church of England continue to sit in the House of Lords of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, as representatives of the established church, and are known as Lords Spiritual. The Bishop of Sodor and Man, whose diocese lies outside the United Kingdom, is an ex officio member of the Legislative Council of the Isle of Man.[55] In the past, the Bishop of Durham had extensive vice-regal powers within his northern diocese, which was a county palatine, the County Palatine of Durham, (previously, Liberty of Durham) of which he was ex officio the earl. In the 19th century, a gradual process of reform was enacted, with the majority of the bishop's historic powers vested in The Crown by 1858.[56]

Eastern Orthodox bishops, along with all other members of the clergy, are canonically forbidden to hold political office.[57] Occasional exceptions to this rule are tolerated when the alternative is political chaos. In the Ottoman Empire, the Patriarch of Constantinople, for example, had de facto administrative, cultural and legal jurisdiction,[58] as well as spiritual authority, over all Eastern Orthodox Christians of the empire, as part of the Ottoman millet system. An Eastern Orthodox bishop headed the Prince-Bishopric of Montenegro from 1516 to 1852, assisted by a secular guvernadur. More recently, Archbishop Makarios III of Cyprus, served as President of the Cyprus from 1960 to 1977, an extremely turbulent time period on the island.[59]

In 2001, Peter Hollingworth, AC, OBE—then the Anglican Archbishop of Brisbane—was controversially appointed Governor-General of Australia. Although Hollingworth gave up his episcopal position to accept the appointment, it still attracted considerable opposition in a country which maintains a formal separation between Church and State.[60][61]

Episcopacy during the English Civil War

[edit]During the period of the English Civil War, the role of bishops as wielders of political power and as upholders of the established church became a matter of heated political controversy. Presbyterianism was the polity of most Reformed Christianity in Europe, and had been favored by many in England since the English Reformation. Since in the primitive Church the offices of presbyter and episkopos were not clearly distinguished, many Puritans held that this was the only form of government the church should have. The Anglican divine, Richard Hooker, objected to this claim in his famous work Of the Laws of Ecclesiastic Polity while, at the same time, defending Presbyterian ordination as valid (in particular Calvin's ordination of Beza). This was the official stance of the English Church until the Commonwealth, during which time, the views of Presbyterians and Independents (Congregationalists) were more freely expressed and practiced.

Christian churches

[edit]Catholic, Eastern and Oriental Orthodox, Lutheran and Anglican churches

[edit]

Bishops exercise leadership roles in the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, certain Lutheran churches, the Anglican Communion, the Independent Catholic churches, the Independent Anglican churches, and certain other, smaller, denominations.

The traditional role of a bishop is as pastor of a diocese (also called a bishopric, synod, eparchy or see), and so to serve as a "diocesan bishop", or "eparch" as it is called in many Eastern Christian churches. Dioceses vary considerably in size, geographically and population-wise. Some dioceses around the Mediterranean Sea which were Christianised early are rather compact, whereas dioceses in areas of rapid modern growth in Christian commitment, as in some parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, South America and the Far East, are much larger and more populous.

As well as traditional diocesan bishops, many churches have a well-developed structure of church leadership that involves a number of layers of authority and responsibility:

- Archbishop

- An archbishop is the bishop of an archdiocese. This is usually a prestigious diocese with an important place in local church history. In the Catholic Church, the title is purely honorific and carries no extra jurisdiction, though most archbishops are also metropolitan bishops, as above, and are always awarded a pallium. In most provinces of the Anglican Communion, however, an archbishop has metropolitical and primatial power.

- Area bishop

- Some Anglican suffragans are given the responsibility for a geographical area within the diocese (for example, the Bishop of Stepney is an area bishop within the Diocese of London).

- Assistant bishop

- Honorary assistant bishop, assisting bishop, or bishop emeritus: these titles are usually applied to retired bishops who are given a general licence to minister as episcopal pastors under a diocesan's oversight. The titles, in this meaning, are not used by the Catholic Church.

- Auxiliary bishop

- An auxiliary bishop is a full-time assistant to a diocesan bishop (the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox equivalent of an Anglican suffragan bishop). An auxiliary bishop is a titular bishop, and he is to be appointed as a vicar general or at least as an episcopal vicar of the diocese in which he serves.[62]

- Catholicos

- Catholicoi are the heads of some of the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Eastern Rite Catholic sui iuris churches (notably the Armenian), roughly similar to a Patriarch.

- Chorbishop

- A chorbishop is an official of a diocese in some Eastern Christian churches. Chorbishops are not generally ordained bishops – they are not given the sacrament of Holy Orders in that degree – but function as assistants to the diocesan bishop with certain honorary privileges.

- Coadjutor bishop

- A coadjutor bishop is an auxiliary bishop who is given almost equal authority in a diocese with the diocesan bishop, and the automatic right to succeed the incumbent diocesan bishop. The appointment of coadjutors is often seen as a means of providing for continuity of church leadership.

- General bishop

- A title and role in some churches, not associated with a diocese. In the Coptic Orthodox Church the episcopal ranks from highest to lowest are metropolitan archbishops, metropolitan bishops, diocesan bishops, bishops exarchs of the throne, suffragan bishops, auxiliary bishops, general bishops, and finally chorbishops. Bishops of the same category rank according to date of consecration.

- Major archbishop

- Major archbishops are the heads of some of the Eastern Catholic Churches. Their authority within their sui juris church is equal to that of a patriarch, but they receive fewer ceremonial honors.

- Metropolitan bishop

- A metropolitan bishop is an archbishop in charge of an ecclesiastical province, or group of dioceses, and in addition to having immediate jurisdiction over his own archdiocese, also exercises some oversight over the other dioceses within that province. Sometimes a metropolitan may also be the head of an autocephalous, sui iuris, or autonomous church when the number of adherents of that tradition are small. In the Latin Church, metropolitans are always archbishops; in many Eastern churches, the title is "metropolitan", with some of these churches using "archbishop" as a separate office.

- Patriarch

- Patriarchs are the bishops who head certain ancient autocephalous or sui iuris churches, which are a collection of metropolitan sees or provinces. After the First Ecumenical Council at Nicea, the church structure was patterned after the administrative divisions of the Roman Empire wherein a metropolitan or bishop of a metropolis came to be the ecclesiastical head of a civil capital of a province or a metropolis. Whereas, the bishop of the larger administrative district, diocese, came to be called an exarch. In a few cases, a bishop came to preside over a number of dioceses, i.e., Rome, Antioch, and Alexandria. At the Fourth Ecumenical Council at Chalcedon in 451, Constantinople was given jurisdiction over three dioceses for the reason that the city was "the residence of the emperor and senate". Additionally, Jerusalem was recognized at the Council of Chalcedon as one of the major sees. In 692, the Quinisext Council formally recognized and ranked the sees of the Pentarchy in order of preeminence, at that time Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem. In the Catholic Church, Patriarchs sometimes call their leaders Catholicos; the Patriarch of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, Egypt, is called Pope, meaning 'Father'. While most patriarchs in the Eastern Catholic Churches have jurisdiction over a particular church sui iuris, all Latin Church patriarchs, except for the Pope, have only honorary titles. In 2006, Pope Benedict XVI gave up the title of Patriarch of the West. The first recorded use of the title by a Roman Pope was by Theodore I in 620. However, early church documents, such as those of the First Council of Nicaea (325) had always listed the Pope of Rome first among the Ancient Patriarchs (first three, and later five: Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem—collectively referred to as the Pentarchy). Later, the heads of various national churches became Patriarchs, but they are ranked below the Pentarchy.

- Te Pīhopa

- The Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia uses — even in English language usage — this Māori language term for its tikanga Māori bishops.

- Primate

- A primate is usually the bishop of the oldest church of a nation. Sometimes this carries jurisdiction over metropolitan bishops, but usually it is purely honorific. The primate of the Scottish Episcopal Church is chosen from among the diocesan bishops, and, while retaining diocesan responsibility, is called Primus.

- Presiding bishop or president bishop

- These titles are often used for the head of a national Anglican church, but the title is not usually associated with a particular episcopal see like the title of a primate.

- Suffragan bishop

- A suffragan bishop is a bishop subordinate to a metropolitan. In the Catholic Church this term is applied to all non-metropolitan bishops (that is, diocesan bishops of dioceses within a metropolitan's province, and auxiliary bishops). In the Anglican Communion, the term applies to a bishop who is a full-time assistant to a diocesan bishop: the Bishop of Warwick is suffragan to the Bishop of Coventry (the diocesan), though both live in Coventry.

- Supreme bishop

- The obispo maximo, or supreme bishop, of the Philippine Independent Church is elected by the General Assembly of the church. He is the chief executive officer of the church. He also holds an important pastoral role, being the spiritual head and chief pastor of the church. He has precedence of honor and prominence of position among, and recognized to have primacy, over other bishops.

- Titular bishop

- A titular bishop is a bishop without a diocese. Rather, the bishop is head of a titular see, which is usually an ancient city that used to have a bishop, but, for some reason or other, does not have one now. Titular bishops often serve as auxiliary bishops. In the Ecumenical Patriarchate, bishops of modern dioceses are often given a titular see alongside their modern one (for example, the archbishop of Thyateira and Great Britain).

Duties

[edit]

In Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, High Church Lutheranism, and Anglicanism, only a bishop can ordain other bishops, priests, and deacons.[63]

The bishop is the ordinary minister of the sacrament of confirmation in the Latin Church, and in the Old Catholic communion only a bishop may administer this sacrament. In the Lutheran and Anglican churches, the bishop normatively administers the rite of confirmation, although in those denominations that do not have an episcopal polity, confirmation is administered by the priest.[64] However, in the Byzantine and other Eastern rites, whether Eastern or Oriental Orthodox or Eastern Catholic, chrismation is done immediately after baptism, and thus the priest is the one who confirms, using chrism blessed by a bishop.[65]

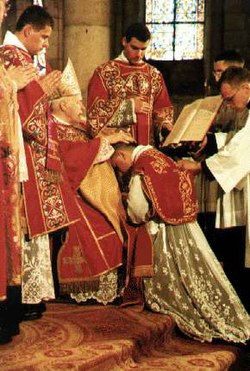

Ordination of bishops

[edit]Bishops in all of these communions are ordained or consecrated by other bishops through the laying on of hands. Ordination of a bishop, and thus continuation of apostolic succession, takes place through a ritual centred on the imposition of hands and prayer.[66][67][68]

In Scandinavia and the Baltic region, Lutheran churches participating in the Porvoo Communion (those of Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Estonia, and Lithuania), as well as many non-Porvoo membership Lutheran churches (including those of Kenya, Latvia, and Russia), as well as the confessional Communion of Nordic Lutheran Dioceses, believe that they ordain their bishops in the apostolic succession in lines stemming from the original apostles.[69][70][71] The New Westminster Dictionary of Church History states that "In Sweden the apostolic succession was preserved because the Catholic bishops were allowed to stay in office, but they had to approve changes in the ceremonies."[72]

While traditional teaching maintains that any bishop with apostolic succession can validly perform the ordination of another bishop, some churches require two or three bishops participate, either to ensure sacramental validity or to conform with church law.

Peculiar to the Catholic Church

[edit]Catholic doctrine holds that one bishop can validly ordain another (priest) as a bishop. Although a minimum of three bishops participating is desirable (there are usually several more) in order to demonstrate collegiality, canonically only one bishop is necessary.[73] The Second Vatican Council's Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy stated that "when a bishop is consecrated, the laying of hands may be done by all the bishops present".[74]

Apart from the ordination, which is always done by other bishops, there are different methods as to the actual selection of a candidate for ordination as bishop. The Dicastery for Bishops generally oversees the selection of new bishops, with recommendations sent for the approval of the pope.[75] The papal nuncio usually solicits names from the bishops of a country, consults with priests and leading members of a laity, and then selects three to be forwarded to the Holy See. In Europe, some cathedral chapters have duties to elect bishops. The Eastern Catholic churches generally elect their own bishops. Most Eastern Orthodox churches allow varying amounts of formalised laity or lower clergy influence on the choice of bishops. This also applies in those Eastern churches which are in union with the pope, though it is required that he give assent.

The pope, in addition to being the Bishop of Rome and spiritual head of the Catholic Church, is also the Patriarch of the Latin Church. Each bishop within the Latin Church is answerable directly to the Pope and not any other bishop except to metropolitans in certain oversight instances. In this instante, the pope uses the title Patriarch of the West, although this title was dropped from use between 2006 and 2024, when Pope Francis reinstituted it.[76]

Recognition of other churches' ordinations

[edit]The Catholic Church does recognise as valid (though illicit) ordinations done by breakaway Catholic, Old Catholic or Oriental bishops, and groups descended from them; it also regards as both valid and licit those ordinations done by bishops of the Eastern churches,[d] so long as those receiving the ordination conform to other canonical requirements (for example, is an adult male) and an eastern orthodox rite of episcopal ordination, expressing the proper functions and sacramental status of a bishop, is used; this has given rise to the phenomenon of episcopi vagantes (for example, clergy of the Independent Catholic groups which claim apostolic succession, though this claim is rejected by both Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy). With respect to Lutheranism, "the Catholic Church has never officially expressed its judgement on the validity of orders as they have been handed down by episcopal succession in these two national Lutheran churches" (the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Sweden and the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland) though it does "question how the ecclesiastical break in the 16th century has affected the apostolicity of the churches of the Reformation and thus the apostolicity of their ministry".[77][78]

Since Pope Leo XIII issued the bull Apostolicae curae in 1896, the Catholic Church has insisted that Anglican orders are invalid because of the Reformed changes in the Anglican ordination rites of the 16th century and divergence in understanding of the theology of priesthood, episcopacy and Eucharist. However, since the 1930s, Utrecht Old Catholic bishops (recognised by the Holy See as validly ordained) have sometimes taken part in the ordination of Anglican bishops. According to the writer Timothy Dufort, by 1969, all Church of England bishops had acquired Old Catholic lines of apostolic succession recognised by the Holy See.[79] This development has been used to argue that the strain of apostolic succession has been re-introduced into Anglicanism, at least within the Church of England.[80] However, other issues, such as the Anglican ordination of women, is at variance with Catholic understanding of Christian teaching, and have contributed to the reaffirmation of Catholic rejection of Anglican ordinations.[81][82]

The Eastern Orthodox Church does not accept the validity of any ordinations performed by the Independent Catholic or Independent Orthodox groups, as Eastern Orthodoxy considers to be spurious any consecration outside the church as a whole. Eastern Orthodoxy considers apostolic succession to exist only within themselves as the one true church, and not through any authority held by individual bishops; thus, if a bishop ordains someone to serve outside the (Eastern Orthodox) Church, the ceremony is ineffectual, and no ordination has taken place regardless of the ritual used or the ordaining prelate's position within the Eastern Orthodox Church.

The position of the Catholic Church is slightly different. Whilst it does recognise the validity of the orders of certain groups which separated from communion with Holy See (for instance, the ordinations of the Old Catholics in communion with Utrecht, as well as the Polish National Catholic Church, which received its orders directly from Utrecht, and was until recently part of that communion), Catholicism does not recognise the orders of any group whose teaching is at variance with what they consider the core tenets of Christianity; this is the case even though the clergy of the Independent Catholic groups may use the proper ordination ritual. There are also other reasons why the Holy See does not recognise the validity of the orders of the independent clergy:

- They hold that the continuing practice among many independent clergy of one person receiving multiple ordinations in order to secure apostolic succession, betrays an incorrect and mechanistic theology of ordination.

- They hold that the practice within independent groups of ordaining women (such as within certain member communities of the Anglican Communion) demonstrates an understanding of priesthood that they vindicate is totally unacceptable to the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches as they believe that the Universal Church does not possess such authority; thus, they uphold that any ceremonies performed by these women should be considered being sacramentally invalid.[81][82]

- The theology of male clergy within the Independent movement is also suspect according to the Catholics, as they presumably approve of the ordination of females, and may have even undergone an (invalid) ordination ceremony conducted by a woman.

Whilst members of the Independent Catholic movement take seriously the issue of valid orders, it is highly significant that the relevant Vatican Congregations tend not to respond to petitions from Independent Catholic bishops and clergy who seek to be received into communion with the Holy See, hoping to continue in some sacramental role. In those instances where the pope does grant reconciliation, those deemed to be clerics within the Independent Old Catholic movement are invariably admitted as laity and not priests or bishops.

There is a mutual recognition of the validity of orders amongst Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Old Catholic, Oriental Orthodox and Assyrian Church of the East churches.[83]

Some provinces of the Anglican Communion have begun ordaining women as bishops in recent decades—for example, England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, the United States, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and Cuba. The first woman to be consecrated a bishop within Anglicanism was Barbara Harris, who was ordained in the United States in 1989.[84] In 2006, Katharine Jefferts Schori, the Episcopal Bishop of Nevada, became the first woman to become the presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church.[85]

In the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada (ELCIC), the largest Lutheran church bodies in the United States and Canada, respectively, and roughly based on the Nordic Lutheran national churches (similar to that of the Church of England), bishops are elected by Synod Assemblies, consisting of both lay members and clergy, for a term of six years, which can be renewed, depending upon the local synod's "constitution" (which is mirrored on either the ELCA or ELCIC's national constitution). Since the implementation of concordats between the ELCA and the Episcopal Church of the United States and the ELCIC and the Anglican Church of Canada, all bishops, including the presiding bishop (ELCA) or the national bishop (ELCIC), have been consecrated using the historic succession in line with bishops from the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Sweden,[86] with at least one Anglican bishop serving as co-consecrator.[87][88]

Although ELCA agreed with the Episcopal Church to limit ordination to the bishop "ordinarily", ELCA pastor-ordinators are given permission to perform the rites in "extraordinary" circumstance. In practice, "extraordinary" circumstance have included disagreeing with Episcopalian views of the episcopate, and as a result, ELCA pastors ordained by other pastors are not permitted to be deployed to Episcopal Churches (they can, however, serve in Presbyterian Church USA, United Methodist Church, Reformed Church in America, and Moravian Church congregations, as the ELCA is in full communion with these denominations). The Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod (LCMS) and the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod (WELS), the second and third largest Lutheran bodies in the United States and the two largest Confessional Lutheran bodies in North America, do not follow an episcopal form of governance, settling instead on a form of quasi-congregationalism patterned off what they believe to be the practice of the early church. The second largest of the three predecessor bodies of the ELCA, the American Lutheran Church, was a congregationalist body, with national and synod presidents before they were re-titled as bishops (borrowing from the Lutheran churches in Germany) in the 1980s. With regard to ecclesial discipline and oversight, national and synod presidents typically function similarly to bishops in episcopal bodies.[89]

Methodism

[edit]African Methodist Episcopal Church

[edit]In the African Methodist Episcopal Church, "Bishops are the Chief Officers of the Connectional Organization. They are elected for life by a majority vote of the General Conference which meets every four years."[90]

Christian Methodist Episcopal Church

[edit]In the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States, bishops are administrative superintendents of the church; they are elected by "delegate" votes for as many years deemed until the age of 74, then the bishop must retire. Among their duties, are responsibility for appointing clergy to serve local churches as pastor, for performing ordinations, and for safeguarding the doctrine and discipline of the church. The General Conference, a meeting every four years, has an equal number of clergy and lay delegates. In each Annual Conference, CME bishops serve for four-year terms. In 2010, Teresa E. Jefferson-Snorton was elected as a bishop, becoming the first woman to hold that position.[91] As of 2024, she remains the only female bishop in CME.[92]

United Methodist Church

[edit]

In the United Methodist Church (the largest branch of Methodism in the world) bishops serve as administrative and pastoral superintendents of the church. They are elected for life from among the ordained elders (presbyters) by vote of the delegates in regional (called jurisdictional) conferences, and are consecrated by the other bishops present at the conference through the laying on of hands. In the United Methodist Church bishops remain members of the "Order of Elders" while being consecrated to the "Office of the Episcopacy". Within the United Methodist Church only bishops are empowered to consecrate bishops and ordain clergy. Among their most critical duties is the ordination and appointment of clergy to serve local churches as pastor, presiding at sessions of the Annual, Jurisdictional, and General Conferences, providing pastoral ministry for the clergy under their charge, and safeguarding the doctrine and discipline of the church. Furthermore, individual bishops, or the Council of Bishops as a whole, often serve a prophetic role, making statements on important social issues and setting forth a vision for the denomination, though they have no legislative authority of their own. In all of these areas, bishops of the United Methodist Church function very much in the historic meaning of the term. According to the Book of Discipline of the United Methodist Church, a bishop's responsibilities are:

Leadership.—Spiritual and Temporal—

- To lead and oversee the spiritual and temporal affairs of The United Methodist Church, which confesses Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior, and particularly to lead the Church in its mission of witness and service in the world.

- To travel through the connection at large as the Council of Bishops (¶ 526) to implement strategy for the concern of the Church.

- To provide liaison and leadership in the quest for Christian unity in ministry, mission, and structure and in the search for strengthened relationships with other living faith communities.

- To organize such Missions as shall have been authorized by the General Conference.

- To promote and support the evangelistic vision of the whole Church.

- To discharge such other duties as the Discipline may direct.

Presidential Duties.—1. To preside in the General, Jurisdictional, Central, and Annual Conferences. 2. To form the districts after consultation with the district superintendents and after the number of the same has been determined by vote of the Annual Conference. 3. To appoint the district superintendents annually (¶¶ 517–518). 4. To consecrate bishops, to ordain elders and deacons, to consecrate diaconal ministers, to commission deaconesses and home missionaries, and to see that the names of the persons commissioned and consecrated are entered on the journals of the conference and that proper credentials are furnished to these persons.

Working with Ministers.—1. To make and fix the appointments in the Annual Conferences, Provisional Annual Conferences, and Missions as the Discipline may direct (¶¶ 529–533).

2. To divide or to unite a circuit(s), stations(s), or mission(s) as judged necessary for missionary strategy and then to make appropriate appointments. 3. To read the appointments of deaconesses, diaconal ministers, lay persons in service under the World Division of the General Board of Global Ministries, and home missionaries. 4. To fix the Charge Conference membership of all ordained ministers appointed to ministries other than the local church in keeping with ¶443.3. 5. To transfer, upon the request of the receiving bishop, ministerial member(s) of one Annual Conference to another, provided said member(s) agrees to transfer; and to send immediately to the secretaries of both conferences involved, to the conference Boards of Ordained Ministry, and to the clearing house of the General Board of Pensions written notices of the transfer of members and of their standing in the course of study if they are undergraduates.[93]

In each Annual Conference, United Methodist bishops serve for four-year terms, and may serve up to three terms before either retirement or appointment to a new Conference. United Methodist bishops may be male or female, with Marjorie Matthews being the first woman to be consecrated a bishop in 1980.

The collegial expression of episcopal leadership in the United Methodist Church is known as the Council of Bishops. The Council of Bishops speaks to the church and through the church into the world and gives leadership in the quest for Christian unity and interreligious relationships.[93] The Conference of Methodist Bishops includes the United Methodist Council of Bishops plus bishops from affiliated autonomous Methodist or United churches.

John Wesley consecrated Thomas Coke a "General Superintendent", and directed that Francis Asbury also be consecrated for the United States of America in 1784, where the Methodist Episcopal Church first became a separate denomination apart from the Church of England. Coke soon returned to England, but Asbury was the primary builder of the new church. At first he did not call himself bishop, but eventually submitted to the usage by the denomination.

Notable bishops in United Methodist history include Coke, Asbury, Richard Whatcoat, Philip William Otterbein, Martin Boehm, Jacob Albright, John Seybert, Matthew Simpson, John S. Stamm, William Ragsdale Cannon, Marjorie Matthews, Leontine T. Kelly, William B. Oden, Ntambo Nkulu Ntanda, Joseph Sprague, William Henry Willimon, and Thomas Bickerton.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

[edit]In The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the bishop is the leader of a local congregation, called a ward. As with most LDS priesthood holders, the bishop is a part-time lay minister and earns a living through other employment. As such, it is his duty to preside, call local leaders, and judge the worthiness of members for certain activities. The bishop does not deliver sermons at every service (generally asking members to do so), but is expected to be a spiritual guide for his congregation. It is therefore believed that he has both the right and ability to receive divine inspiration (through the Holy Spirit) for the ward under his direction. Because it is a part-time position, all able members are expected to assist in the management of the ward by holding delegated lay positions (for example, women's and youth leaders, teachers) referred to as callings. The bishop is especially responsible for leading the youth,[94] in connection with the fact that a bishop is the president of the Aaronic priesthood in his ward (and is thus a form of Mormon Kohen). Although members are asked to confess serious sins to him, unlike the Catholic Church, he is not the instrument of divine forgiveness, but merely a guide through the repentance process (and a judge in case transgressions warrant excommunication or other official discipline). The bishop is also responsible for the physical welfare of the ward, and thus collects tithing and fast offerings and distributes financial assistance where needed.

A literal descendant of Aaron has "legal right" to act as a bishop[95] after being found worthy and ordained by the First Presidency.[96] In the absence of a literal descendant of Aaron, a high priest in the Melchizedek priesthood is called to be a bishop.[96] Each bishop is selected from resident members of the ward by the stake presidency with approval of the First Presidency, and chooses two counselors to form a bishopric. An priesthood holder called as bishop must be ordained a high priest if he is not already one, unlike the similar function of branch president.[97] In special circumstances (such as a ward consisting entirely of young university students), a bishop may be chosen from outside the ward. Traditionally, bishops are married, though this is not always the case.[98] A bishop is typically released after about five years and a new bishop is called to the position. Although the former bishop is released from his duties, he continues to hold the Aaronic priesthood office of bishop. Church members frequently refer to a former bishop as "Bishop" as a sign of respect and affection.

Latter-day Saint bishops do not wear any special clothing or insignia the way clergy in many other churches do, but are expected to dress and groom themselves neatly and conservatively per their local culture, especially when performing official duties. Bishops (as well as other members of the priesthood) can trace their line of authority back to Joseph Smith, who, according to church doctrine, was ordained to lead the church in modern times by the ancient apostles Peter, James, and John, who were ordained to lead the Church by Jesus Christ.[99]

At the global level, the presiding bishop oversees the temporal affairs (buildings, properties, commercial corporations, and so on) of the worldwide church, including the church's massive global humanitarian aid and social welfare programs. The presiding bishop has two counselors; the three together form the presiding bishopric.[100] As opposed to ward bishoprics, where the counselors do not hold the office of bishop, all three men in the presiding bishopric hold the office of bishop, and thus the counselors, as with the presiding bishop, are formally referred to as "Bishop".[101]

Irvingism

[edit]New Apostolic Church

[edit]The New Apostolic Church (NAC) teaches three classes of ministries: deacons, priests and apostles. The apostles, who are all included in the apostolate with the Chief Apostle as head, are the highest ministries. Of the several kinds of priestly ministries, the bishop is the highest. Nearly all bishops are set in line directly from the chief apostle. They support and help their superior apostle.[citation needed]

Pentecostalism

[edit]Church of God in Christ

[edit]In the Church of God in Christ (COGIC), the ecclesiastical structure is composed of large dioceses that are called "jurisdictions" within COGIC, each under the authority of a bishop, sometimes called "state bishops". They can either be made up of large geographical regions of churches or churches that are grouped and organized together as their own separate jurisdictions because of similar affiliations, regardless of geographical location or dispersion. Each state in the U.S. has at least one jurisdiction while others may have several more, and each jurisdiction is usually composed of between 30 and 100 churches. Each jurisdiction is then broken down into several districts, which are smaller groups of churches (either grouped by geographical situation or by similar affiliations) which are each under the authority of District Superintendents who answer to the authority of their jurisdictional/state bishop. There are currently over 170 jurisdictions in the United States, and over 30 jurisdictions in other countries. The bishops of each jurisdiction, according to the COGIC Manual, are considered to be the modern day equivalent in the church of the early apostles and overseers of the New Testament church, and as the highest ranking clergymen in the COGIC, they are tasked with the responsibilities of being the head overseers of all religious, civil, and economic ministries and protocol for the church denomination.[102] They also have the authority to appoint and ordain local pastors, elders, ministers, and reverends within the denomination. The bishops of the COGIC denomination are all collectively called "The Board of Bishops".[103] From the Board of Bishops, and the General Assembly of the COGIC, the body of the church composed of clergy and lay delegates that are responsible for making and enforcing the bylaws of the denomination, every four years, twelve bishops from the COGIC are elected as "The General Board" of the church, who work alongside the delegates of the General Assembly and Board of Bishops to provide administration over the denomination as the church's head executive leaders.[104] One of twelve bishops of the General Board is also elected the "presiding bishop" of the church, and two others are appointed by the presiding bishop himself, as his first and second assistant presiding bishops.

Bishops in the Church of God in Christ usually wear black clergy suits which consist of a black suit blazer, black pants, a purple or scarlet clergy shirt and a white clerical collar, which is usually referred to as "Class B Civic attire". Bishops in COGIC also typically wear the Anglican Choir Dress style vestments of a long purple or scarlet chimere, cuffs, and tippet worn over a long white rochet, and a gold pectoral cross worn around the neck with the tippet. This is usually referred to as "Class A Ceremonial attire". The bishops of COGIC alternate between Class A Ceremonial attire and Class B Civic attire depending on the protocol of the religious services and other events they have to attend.[103][102]

Church of God (Cleveland, Tennessee)

[edit]In the polity of the Church of God (Cleveland, Tennessee), the international leader is the presiding bishop, and the members of the executive committee are executive bishops. Collectively, they supervise and appoint national and state leaders across the world. Leaders of individual states and regions are administrative bishops, who have jurisdiction over local churches in their respective states and are vested with appointment authority for local pastorates. All ministers are credentialed at one of three levels of licensure, the most senior of which is the rank of ordained bishop. To be eligible to serve in state, national, or international positions of authority, a minister must hold the rank of ordained bishop.

Seventh-day Adventists

[edit]According to the Seventh-day Adventist understanding of the doctrine of the church:

"The "elders" (Greek, presbuteros) or "bishops" (episkopos) were the most important officers of the church. The term elder means older one, implying dignity and respect. His position was similar to that of the one who had supervision of the synagogue. The term bishop means "overseer". Paul used these terms interchangeably, equating elders with overseers or bishops (Acts 20:17, 28; Titus 1:5, 7).

"Those who held this position supervised the newly formed churches. Elder referred to the status or rank of the office, while bishop denoted the duty or responsibility of the office—"overseer". Since the apostles also called themselves elders (1 Peter 5:1; 2 John 1; 3 John 1), it is apparent that there were both local elders and itinerant elders, or elders at large. But both kinds of elder functioned as shepherds of the congregations.[105]"

The above understanding is part of the basis of Adventist organizational structure. The world wide Seventh-day Adventist church is organized into local districts, conferences or missions, union conferences or union missions, divisions, and finally at the top is the general conference. At each level (with exception to the local districts), there is an elder who is elected president and a group of elders who serve on the executive committee with the elected president. Those who have been elected president would in effect be the "bishop" while never actually carrying the title or ordained as such because the term is usually associated with the episcopal style of church governance most often found in Catholic, Anglican, Methodist and some Pentecostal/Charismatic circles.

Others

[edit]Some Baptists also have begun taking on the title of bishop.[106] In some smaller Protestant denominations and independent churches, the term bishop is used in the same way as pastor, to refer to the leader of the local congregation, and may be male or female. This usage is especially common in African-American churches, particularly through the Full Gospel Baptist Church Fellowship.

In the Church of Scotland, which has a Presbyterian church structure, the word "bishop" refers to an ordained person, usually a normal parish minister, who has temporary oversight of a trainee minister. In the Presbyterian Church (USA), the term bishop is an expressive name for a Minister of Word and Sacrament who serves a congregation and exercises "the oversight of the flock of Christ."[107] The term is traceable to the 1789 Form of Government of the PC (USA) and the Presbyterian understanding of the pastoral office.[108] Reformed churches on the whole do not tend to have bishops, although there are exceptions.

While not considered orthodox Christian, the Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica uses roles and titles derived from Christianity for its clerical hierarchy, including bishops who have much the same authority and responsibilities as in Catholicism.

The Salvation Army does not have bishops but has appointed leaders of geographical areas, known as Divisional Commanders. Larger geographical areas, called territories, are led by a territorial commander, who is the highest-ranking officer in that territory.

Jehovah's Witnesses do not use the title 'bishop' within their organizational structure, but appoint elders to be overseers (to fulfill the role of oversight) within their congregations.[109]

The Batak Christian Protestant Church of Indonesia, the most prominent Protestant denomination in Indonesia, uses the term Ephorus instead of bishop.[110]

In the Vietnamese syncretist religion of Caodaism, bishops (giáo sư) comprise the fifth of nine hierarchical levels, and are responsible for spiritual and temporal education as well as record-keeping and ceremonies in their parishes. At any one time there are seventy-two bishops. Their authority is described in Section I of the text Tân Luật (revealed through seances in December 1926). Caodai bishops wear robes and headgear of embroidered silk depicting the Divine Eye and the Eight Trigrams. (The color varies according to branch.) This is the full ceremonial dress; the simple version consists of a seven-layered turban.

Dress and insignia in Christianity

[edit]Traditionally, a number of items are associated with the office of a bishop, most notably the mitre and the crosier. Other vestments and insignia vary between Eastern and Western Christianity.

In the Latin Church of the Catholic Church, the choir dress of a bishop includes the purple cassock with amaranth trim, rochet, purple zucchetto (skull cap), purple biretta, and pectoral cross. The cappa magna may be worn, but only within the bishop's own diocese and on especially solemn occasions.[111] The mitre, zucchetto, and stole are generally worn by bishops when presiding over liturgical functions. For liturgical functions other than the Mass the bishop typically wears the cope. Within his own diocese and when celebrating solemnly elsewhere with the consent of the local ordinary, he also uses the crosier.[111] When celebrating Mass, a bishop, like a priest, wears the chasuble. The Caeremoniale Episcoporum recommends, but does not impose, that in solemn celebrations a bishop should also wear a dalmatic, which can always be white, beneath the chasuble, especially when administering the sacrament of holy orders, blessing an abbot or abbess, and dedicating a church or an altar.[111] The Caeremoniale Episcoporum no longer makes mention of episcopal gloves, episcopal sandals, liturgical stockings (also known as buskins), or the accoutrements that it once prescribed for the bishop's horse. The coat of arms of a Latin Church Catholic bishop usually displays a galero with a cross and crosier behind the escutcheon; the specifics differ by location and ecclesiastical rank (see Ecclesiastical heraldry).

Anglican bishops generally make use of the mitre, crosier, ecclesiastical ring, purple cassock, purple zucchetto, and pectoral cross. However, the traditional choir dress of Anglican bishops retains its late mediaeval form, and looks quite different from that of their Catholic counterparts; it consists of a long rochet which is worn with a chimere.

In the Eastern churches (Eastern Orthodox, Eastern Rite Catholic) a bishop will wear the mandyas, panagia (and perhaps an enkolpion), sakkos, omophorion and an Eastern-style mitre. Eastern bishops do not normally wear an episcopal ring; the faithful kiss (or, alternatively, touch their forehead to) the bishop's hand. To seal official documents, he will usually use an inked stamp. An Eastern bishop's coat of arms will normally display an Eastern-style mitre, cross, Eastern-style crosier and a red and white (or red and gold) mantle. The arms of Oriental Orthodox bishops will display the episcopal insignia (mitre or turban) specific to their own liturgical traditions. Variations occur based upon jurisdiction and national customs.

Cathedra

[edit]In Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Lutheran and Anglican cathedrals there is a special chair set aside for the exclusive use of the bishop. This is the bishop's cathedra and is often called the throne. In some Christian denominations, for example, the Anglican Communion, parish churches may maintain a chair for the use of the bishop when he visits; this is to signify the parish's union with the bishop.

-

Byzantine Rite Catholic bishop in non-liturgical clothing

-

An Anglican bishop with a crosier, wearing a rochet under a red chimere and cuffs, a black tippet, and a pectoral cross

-

An Episcopal bishop immediately before presiding at the Great Vigil of Easter in the narthex of St. Michael's Episcopal Cathedral in Boise, Idaho.

-

An Ephorus of the Batak Christian Protestant Church in Indonesia, one of the largest Lutheran churches in Southeast Asia, wearing white bands and Geneva gown

In non-Christian religions

[edit]Buddhism

[edit]The leader of the Buddhist Churches of America (BCA) is their bishop,[112][113][114] The Japanese title for the bishop of the BCA is sochō,[114][115][116] although the English title is favored over the Japanese. When it comes to many other Buddhist terms, the BCA chose to keep them in their original language (terms such as sangha and dana), but with some words (including sochō), they changed/translated these terms into English words.[117][118][119]

Between 1899 and 1944, the BCA held the name Buddhist Mission of North America. The leader of the Buddhist Mission of North America was called kantoku (superintendent/director) between 1899 and 1918. In 1918 the kantoku was promoted to bishop (sochō).[120][121][122] However, according to George J. Tanabe, the title "bishop" was in practice already used by Hawaiian Shin Buddhists (in Honpa Hongwanji Mission of Hawaii) even when the official title was kantoku.[123]

Bishops are also present in other Japanese Buddhist organizations. Higashi Hongan-ji's North American District, Honpa Honganji Mission of Hawaii, Jodo Shinshu Buddhist Temples of Canada,[124] a Jodo Shu temple in Los Angeles, the Shingon temple Koyasan Buddhist Temple,[125] Sōtō Mission in Hawai‘i (a Soto Zen Buddhist institution),[126][127] and the Sōtō Zen Buddhist Community of South America (Comunidade Budista Sōtō Zenshū da América do Sul) all have or have had leaders with the title bishop. As for the Sōtō Zen Buddhist Community of South America, the Japanese title is sōkan, but the leader is in practice referred to as "bishop".[128]

Tenrikyo

[edit]Tenrikyo is a Japanese New Religion with influences from both Shinto and Buddhism.[129] The leader of the Tenrikyo North American Mission has the title of bishop.[129][130]

See also

[edit]- Anglican bishops

- Appointment of Catholic bishops

- Appointment of Church of England bishops

- Bishop in Europe

- Bishops in the Catholic Church

- Bishop of Alexandria, or Pope

- Bishops in the Church of Scotland

- Diocesan bishop

- Ecclesiastical polity (church governance)

- Ganzibra

- Gay bishops

- Hierarchy of the Catholic Church

- List of Catholic bishops of the United States

- List of metropolitans and patriarchs of Moscow

- List of types of spiritual teachers

- List of Lutheran bishops and archbishops

- Lists of patriarchs, archbishops, and bishops

- Lord Bishop

- Order of precedence in the Catholic Church

- Shepherd in religion

- Spokesperson bishops in the Church of England

- Suffragan Bishop in Europe

Notes

[edit]- ^ "It seems that at first the terms 'episcopos' and 'presbyter' were used interchangeably ..."[12]

- ^ "The general consensus among scholars has been that, at the turn of the first and second centuries, local congregations were led by bishops and presbyters whose offices were overlapping or indistinguishable."[13]

- ^

Blessed be God, who has granted unto you, who are yourselves so excellent, to obtain such an excellent bishop.

— Epistle of Ignatius to the Ephesians 1:1[21]

- ^ Section 16 of the Second Vatican Council's Decree on Ecumenism, Unitatis Redintegratio states: "To remove, then, all shadow of doubt, this holy Council solemnly declares that the Churches of the East, while remembering the necessary unity of the whole Church, have the power to govern themselves according to the disciplines proper to them, since these are better suited to the character of their faithful, and more for the good of their souls."

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Ten Frequently Asked Questions About the Reservation of Priestly Ordination to Men | USCCB". www.usccb.org. Retrieved 16 January 2025.

- ^ a b Kashima, Tetsuden (1977). Buddhism in America: the social organization of an ethnic religious institution. Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-8371-9534-6.

- ^ a b "Early Christian Fathers". Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ^ International Standard Version. "Elders". Archived from the original on 5 November 2011. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ Acts 11:30

- ^ Acts 15:22

- ^ Acts 14:23

- ^ Hill 2007.

- ^ Acts 20:17

- ^ Titus 1:5–7

- ^ 1 Peter 5:1

- ^ Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 211.

- ^ Mitchell, Young & Scott Bowie 2006, p. 417.

- ^ "Bona, Algeria". World Digital Library. 1899. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ 1 Timothy 1:3

- ^ Titus 1:5

- ^ Zizioulas, John (2001). Eucharist, Bishop, Church: The Unity of the Church in the Divine Eucharist and the Bishop During the First Three Centuries. Holy Cross Orthodox Press. p. 66.

- ^ a b O'Grady 1997, p. 140.

- ^ Handl, András (1 January 2016). "Viktor I. (189 ?-199 ?) von Rom und die Entstehung des "monarchischen" Episkopats in Rom". Sacris Erudiri. 55: 7–56. doi:10.1484/J.SE.5.112597. ISSN 0771-7776.

- ^ a b Van Hove 1907.

- ^ "Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus". Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Clement, "Hom.", III, lxxii; cfr. Stromata, VI, xiii, cvi; cf. "Const. Apost.", II, viii, 36

- ^ "Didascalia Syr.", IV; III, 10, 11, 20; Cornelius, "Ad Fabianum" in Eusebius, Historia Ecclesiastica, VI, xliii.

- ^ Fr. Pierre-Marie, O.P. (January 2006). "Why the New Rite of Episcopal Consecration is Valid". The Angelus. Archived from the original on 15 November 2006. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ "CHURCH FATHERS: First Council of Nicaea (A.D. 325)". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 27 July 2025.

- ^ a b "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Canonical Age". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 27 July 2025.

- ^ Flodoard de Reims; Fanning, Steven; Bachrach, Bernard S. (2008). The "Annals" of Flodoard of Reims: 919-966. Readings in Medieval Civilizations and Cultures. Peterborough (Ont.): University of Toronto press. ISBN 978-1-4426-0001-0.

- ^ "Pope Eugene IV (Gabriele Condulmer)". Catholic Hierarchy. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Mar Eshai Shimun". Mar Shimun Memorial Foundation. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Mar Benyamin Shimun". Mar Shimun Memorial Foundation. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

Ordained Metropolitan at the age of sixteen on March 2, 1903 by his uncle Mar Rowil Shimun, Catholicos Patriarch XX, Mar Benyamin later succeeded him. Mar Rowil passed away on March 16th of that year and on March 30th Mar Benyamin was consecrated Catholicos Patriarch by Mar Iskhaq (Issac) Khnanishu, Metropolitan, and Mar Estapanos (Stephen), Bishop of Gawar. Mar Benyamin was known for his fair-minded adjudication of all, Assyrian, Turks and Kurds alike.

- ^ "Voice of the East" (PDF). Assyrian Church of the East News. 2015. p. 6.

Born on 10 April 1950 at Kirkuk; Consecrated Bishop in Baghdad by Mar Yosip Khnanishu Metropolitan on 19 February 1967. Living in USA since 2004. Senior-most Bishop of the Assyrian Church of the East.

- ^ "Mar Auraham Shimun". Mar Shimun Memorial Foundation. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Mar Yosip". Mar Yosip Parish. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ Namee, Matthew (18 July 2019). "How long do converts wait before ordination?". Orthodox History. Retrieved 27 July 2025.

- ^ "The Sacrament of Priesthoood - CopticChurch.net". www.copticchurch.net. Retrieved 27 July 2025.

- ^ "Regulations Regarding the Auxiliary Bishops of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America". Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

The candidate for the office of Auxiliary Bishop must be a person of deep faith and ethos, a graduate of an academically accredited Orthodox Theological School of the highest level; be competent in both written and spoken Greek and English, and be known for his administrative and pastoral skills. Furthermore, the candidate must not be younger than 35 years of age, and must have at least five (5) years of recognized successful service in the Holy Archdiocese of America. The manner of enlisting a candidate for the office of Auxiliary Bishop in the catalogue of eligible Bishops is the same with the manner of enlisting a candidate for the office of a Hierarch in general.

- ^ "Ordination". St. Andrew's Greek Orthodox Cathedral. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

The bishop ensures every Christian's membership of the Church of Christ throughout the world and throughout time. Throughout the world in the sense that all Orthodox bishops throughout the world recognise one another by commemorating one another in the diptychs (list of all canonical hierarchs), and throughout time in the sense that every Orthodox bishop can trace their ordination back to the Apostles — and, through them, to our Lord himself — in an unbroken line of succession. Each bishop is typically connected to a particular geographical area, called a diocese. According to the canons of the Church, there should never be more than one bishop with ecclesiastical authority over any particular geographical area. The episcopacy is the only order of the priesthood with mandatory celibacy in the Orthodox Church, and bishops are therefore chosen from monastic or widowed clergy. A bishop should be at least 35 years of age.

- ^ "A New Bishop for Our Diocese – Some Questions and Answers". Diocese of New England. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

A special Diocesan Assembly is convened at which the gathered delegates (each parish body usually has a clergy and a lay delegate representing them at this special Assembly) nominate a candidate. The candidate must be a celibate (never-married or presently widowed) Orthodox Christian man of at least 35 years of age (in practice, of at least 30 years of age), who has no impediments that would impede his service as a bishop. In the Church, the word "impediment" means a specific condition or situation that might disqualify a person from holding a particular office, or carrying out a specific role.

- ^ Spelbring, Meredith. "Bishop C.L. Morton dies: Preacher will be missed all over the world". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

- ^ "About Bishop J. Delano Ellis, II". J.D. Ellis Ministries. Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

- ^ "Beloved Cleveland Bishop J. Delano Ellis dies at age of 75". WEWS. 20 September 2020. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

- ^ "Fourth Century Christianity » Imperial Laws and Letters Involving Religion AD, 364-395". Retrieved 27 July 2025.

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Diocese". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 27 July 2025.

- ^ Library, Cosin's. "Cosin's Durham". Cosin's Library. Retrieved 27 July 2025.

- ^ "Lords Chancellors". tudorplace.com.ar. Retrieved 27 July 2025.

- ^ Vela Palomares, Susanna; Govern d'Andorra; Ministry of Social Affairs and Culture (1997). "Andorra – First and second Paréages (feudal charters)". United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ^ "Apostolic See definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary".

- ^ Collins, Roger (2009). "Introduction". Keepers of the keys of heaven: a history of the papacy. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-01195-7.

One of the most enduring and influential of all human institutions, [...] No one who seeks to make sense of modern issues within Christendom – or, indeed, world history – can neglect the vital shaping role of the popes.

- ^ Faus, José Ignacio Gonzáles. "VIII: Os papas repartem terras". Autoridade da Verdade – Momentos Obscuros do Magistério Eclesiástico (in Spanish). Edições Loyola. pp. 64–65. ISBN 85-15-01750-4.. See also chapter VI, O papa tem poder temporal absoluto (pages 49–55).

- ^ "The Role of the Vatican in the Modern World". Archived from the original on 4 May 2005.

- ^ "The World's Most Powerful People". Forbes. November 2014. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- ^ "The World's Most Powerful People". Forbes. January 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ^ Agnew, John (12 February 2010). "Deus Vult: The Geopolitics of Catholic Church". Geopolitics. 15 (1): 39–61. doi:10.1080/14650040903420388. S2CID 144793259.

- ^ "The First Estate Facts, Overview & Key Information". School History. Retrieved 27 July 2025.

- ^ "The Lord Bishop" (PDF). Tynwald Day 2017. Tynwald. 5 July 2017. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ "Durham County Palatine Act 1858", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 23 July 1858, 1858 c. 45, retrieved 29 November 2021

- ^ "Ukrainian schismatic synod allows "clergy" to run for political office, against Church canons". OrthoChristian.Com. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ "Eastern Orthodoxy - The church of Russia (1448–1800) | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ Wuthnow, Robert (4 December 2013). "Orthodoxy, Greek". The Encyclopedia of Politics and Religion: 2-volume Set. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-28493-9. OCLC 1307463108.

He continued as president and archbishop during the turbulent 1960s and 1970s, when Greek and Turkish Cypriots clashed over what Turks viewed as Greek efforts to disenfranchise them, and the governments of both Greece and Turkey intervened in Cypriot affairs.

- ^ Crampton, Dave (30 April 2001). "Church Vs State Issues Raised In Oz GG Appointment". www.scoop.co.nz. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ "A churchman cannot serve two masters". The Sydney Morning Herald. 4 June 2003. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ "Canon 406". Code of Canon Law. The Holy See. 1983. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- ^ "Ministry and Ministries". Evangelical Lutheran Church of Sweden. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ Wordsworth, John (1911). The National Church of Sweden. A. R. Mowbray & Company Limited. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-8401-2821-8.

This same archbishop compiled a code of the statues of his diocese, from which we may learn much as to the administration of the sacraments customary in Sweden. The three forms just named were to be taught to children by their parents and god-parents. Children of seven years old and upwards were to be confirmed by the bishop fasting—the implication that if they were confirmed at an earlier age they need not fast. No one was to be confirmed more than once, and parents were frequently to remind their children by whom and where they were confirmed. Bishops might change names in confirmation, and no one is to be admitted to minor orders without confirmation.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1313 Archived 27 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dunn, Matt (5 July 2018). "Form and Matter in the Sacraments (Continued)". Ascension Press Media. Retrieved 27 July 2025.

- ^ "The Consecration (Ordination) Of An Orthodox Bishop". American Carpatho-Russian Orthodox Diocese of North America. Retrieved 27 July 2025.

- ^ "The Consecration of Bishops". Church of England. Retrieved 27 July 2025.

- ^ König, Andrea (2010). Mission, Dialog und friedliche Koexistenz: Zusammenleben in einer multireligiösen und säkularen Gesellschaft : Situation, Initiativen und Perspektiven für die Zukunft. Peter Lang. p. 205. ISBN 9783631609453.

Having said that, Lutheran bishops in Sweden or Finland, which retained apostolic succession, or other parts of the world, such as Africa or Asia, which gained it from Scandinavia, could easily be engaged to do something similar in Australia, as has been done in the United States, without reliance on Anglicans.

- ^ Walter Obare. "Choose Life!". Concordia Theological Seminary.

- ^ Mark A. Granquist; Jonathan Strom; Mary Jane Haemig; Robert Kolb; Mark C. Mattes (2017). Dictionary of Luther and the Lutheran Traditions. Baker Academic. ISBN 978-1-4934-1023-1.

- ^ Benedetto, Robert; Duke, James O. (13 August 2008). The New Westminster Dictionary of Church History: The Early, Medieval, and Reformation Eras. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 594. ISBN 978-0664224165.

In Sweden the apostolic succession was preserved because the Catholic bishops were allowed to stay in office, but they had to approve changes in the ceremonies.

- ^ "One is not enough: Why new bishops need 'co-consecrators'". 25 September 2023. Retrieved 27 July 2025.

- ^ Second Vatican Council, Sacrosanctum Concilium, paragraph 76, published on 4 December 1963, accessed on 15 July 2025

- ^ "How Bishops Are Appointed". United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ "Catholic News Service". Archived from the original on 8 March 2006. Retrieved 19 October 2008.

- ^ Sullivan, Francis Aloysius (2001). From Apostles to Bishops: The Development of the Episcopacy in the Early Church. Paulist Press. p. 4. ISBN 0809105349.

To my knowledge, the Catholic Church has never officially expressed its judgement on the validity of orders as they have been handed down by episcopal succession in these two national Lutheran churches.

- ^ "Roman Catholic – Lutheran Dialogue Group for Sweden and Finland, Justification in the Life of the Church, section 297, page 101" (PDF).[permanent dead link]

- ^ Timothy Dufort, The Tablet, 29 May 1982, pp. 536–538.

- ^ Dufort, Timothy (29 May 1982). The Tablet. pp. 536–538.

- ^ a b Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Responsum ad Dubium Concerning the Teaching Contained in Ordinatio Sacerdotalis Archived 4 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine, 25 October 1995; Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Commentary, Concerning the Reply of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith on the Teaching Contained in the Apostolic Letter "Ordinatio Sacerdotalis", 25 October 1995.

- ^ a b Handley, Paul (27 May 2003). "Churches' Goal Is Unity, Not Uniformity Spokesman for Vatican Declares". Church Times. p. 2.

- ^ Roberson, Ronald (Spring 2010). "The Dialogues of the Catholic Church with the Separated Eastern Churches". U.S. Catholic Historian. 28 (2): 135–152. doi:10.1353/cht.0.0041. JSTOR 40731267. S2CID 161330476.

- ^ Doubek, James (14 March 2020). "Barbara C. Harris, First Female Bishop In Anglican Communion, Dies At 89". NPR. Retrieved 27 July 2025.

- ^ "A Woman Is Installed as Top Episcopal Bishop (Published 2006)". 5 November 2006. Retrieved 27 July 2025.

- ^ Veliko, Lydia; Gros, Jeffrey (2005). Growing Consensus II: Church Dialogues in the United States, 1992-2004. USCCB Publishing. ISBN 978-1-57455-557-8.

In order to receive the historic episcopate, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America pledges that, following the adoption of this Concordat and in keeping with the collegiality and continuity of ordained ministry attested as early as canon 4 of the First Ecumenical Council (Nicea I, AD 325), at least three bishops already sharing in the sign of episcopal succession will be invited to participate in the installation of its next Presiding Bishop through prayer for the gift of the Holy Spirit and with the laying-on of hands. These participating bishops will be invited from churches of the Lutheran communion which share in the historic episcopate.

- ^ "A Lutheran Proposal for a Revision of the Concordat of Agreement". 19 August 1999. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011.

- ^ Wright, J. Robert (Spring 1999). "The Historic Episcopate: An Episcopalian Viewpoint". Lutheran Partners. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011.

- ^ "The Function of Bishops in the Ancient Church". kencollins.com.

- ^ "Bishops of the Church". African Methodist Episcopal Church. 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ McGuffie, Felicia (18 July 2010). "The Rev. Dr. Teresa Snorton is elected first female bishop of the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church (C.M.E.)". The Philadelphia Sunday Sun. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015.

- ^ Blake, John (15 July 2024). "Many women stay in religious groups that don't let them become leaders. Here are three reasons why". CNN. Retrieved 15 February 2025.

- ^ a b Anon 1980.

- ^ "General Handbook, 6.1.2".

- ^ "Doctrine and Covenants 107:76".

- ^ a b "Doctrine and Covenants 68:20".

- ^ "General Handbook, 6.2".