Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Given name

View on Wikipedia

A given name (also known as a forename or first name) is the part of a personal name[1] that identifies a person, potentially with a middle name as well, and differentiates that person from the other members of a group (typically a family or clan) who have a common surname. The term given name refers to a name usually bestowed at or close to the time of birth, usually by the parents of the newborn. A Christian name is the first name which is given at baptism, in Christian custom.

In informal situations, given names are often used in a familiar and friendly manner.[1] In more formal situations, a person's surname is more commonly used. In Western culture, the idioms "on a first-name basis" and "being on first-name terms" refer to the familiarity inherent in addressing someone by their given name.[1]

By contrast, a surname (also known as a family name, last name, or gentile name) is normally inherited and shared with other members of one's immediate family.[2] Regnal names and religious or monastic names are special given names bestowed upon someone receiving a crown or entering a religious order; such a person then typically becomes known chiefly by that name.

Name order

[edit]The order given name – family name, commonly known as Western name order, is used throughout most European countries and in countries that have cultures predominantly influenced by European culture, including North and South America; North, East, Central and West India; Australia, New Zealand, and the Philippines.

The order family name – given name, commonly known as Eastern name order, is primarily used in East Asia (for example in China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Vietnam, among others, and by Malaysian Chinese), as well as in Southern and North-Eastern parts of India, and as a standard in Hungary. This order is also used to various degrees and in specific contexts in other European countries, such as Austria and adjacent areas of Germany (that is, Bavaria),[note 1] and in France, Switzerland, Belgium, Greece and Italy,[citation needed] possibly because of the influence of bureaucracy, which commonly puts the family name before the given name. In China and Korea, part of the given name may be shared among all members of a given generation within a family and extended family or families, in order to differentiate those generations from other generations.

The order given name – father's family name – mother's family name is commonly used in several Spanish-speaking countries to acknowledge the families of both parents.[3]

The order given name – mother's family name – father's family name is commonly used in Portuguese-speaking countries to acknowledge the families of both parents. Today, people in Spain and Uruguay can rearrange the order of their names legally to this order.

The order given name – father's given name – grandfather's given name (often referred to as triple name) is the official naming order used in Arabic countries (for example Saudi Arabia, Iraq and United Arab Emirates).

Multiple and compound given names

[edit]In many Western cultures, people often have multiple given names. Most often the first one in sequence is the one that a person goes by, although exceptions are not uncommon, such as in the cases of John Edgar Hoover (J. Edgar) and Dame Mary Barbara Hamilton Cartland (Barbara). The given name might also be used in compound form, as in, for example, John Paul or a hyphenated style like Bengt-Arne. A middle name might be part of a compound given name or might be, instead, a maiden name, a patronymic, or a baptismal name.

In England, it was unusual for a person to have more than one given name until the seventeenth century when Charles James Stuart (King Charles I) was baptised with two names. That was a French fashion, which spread to the English aristocracy, following the royal example, then spread to the general population and became common by the end of the eighteenth century.[4]

Some double-given names for women were used at the start of the eighteenth century but were used together as a unit: Anna Maria, Mary Anne and Sarah Jane. Those became stereotyped as the typical names of servants and so became unfashionable in the nineteenth century.[citation needed]

Double names remain popular in the Southern United States.[5]

Double names are also common among Vietnamese names to make repeated name in the family. For example, Đặng Vũ Minh Anh and Đặng Vũ Minh Ánh, are two sisters with the given names Minh Anh and Minh Ánh.

In some cultures there is a tradition to use the full name of a respectable person as an inseparable compound given name.[6] Examples include Thomas Jefferson in honor of Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, and Johann Nepomuk (and variants in other languages) honoring John of Nepomuk, Czech saint.

Another tradition of compound given names are bilingual Hebrew-Yiddish tautological names, such as Aryeh Leib, where both parts mean "lion" in Hebrew and Yiddish respectively.

Initials

[edit]Sometimes, a given name is used as just an initial, especially in combination with the middle initial (such as with H. G. Wells), and more rarely as an initial while the middle name is not one (such as with L. Ron Hubbard).

Legal status

[edit]A child's given name or names are usually chosen by the parents soon after birth. If a name is not assigned at birth, one may be given at a naming ceremony, with family and friends in attendance. In most jurisdictions, a child's name at birth is a matter of public record, inscribed on a birth certificate, or its equivalent. In Western cultures, people normally retain the same given name throughout their lives. However, in some cases these names may be changed by following legal processes or by repute. People may also change their names when immigrating from one country to another with different naming conventions.[7]

In certain jurisdictions, a government-appointed registrar of births may refuse to register a name for the reasons that it may cause a child harm, that it is considered offensive, or if it is deemed impractical. In France, the agency can refer the case to a local judge. Some jurisdictions, such as Sweden, restrict the spelling of names.[note 2] In Denmark, one does not need to register a given name for the child until the child is six months old, and in some cases, one can even wait a little longer than this before the child gets an official name.

Origins and meanings

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (June 2020) |

Parents may choose a name because of its meaning. This may be a personal or familial meaning, such as giving a child the name of an admired person, or it may be an example of nominative determinism, in which the parents give the child a name that they believe will be lucky or favourable for the child. Given names most often derive from the following categories:

- Aspirational personal traits (external and internal). For example, the male names:

- Clement ("merciful");[9][10] as popularised by Pope Clement I (88–98), saint, and his many papal successors of that name;

- Augustus ("consecrated, holy"[11]), first popularised by the first Roman Emperor; later (as Augustine) by two saints;

- English examples include numerous female names such as Faith, Prudence, Amanda (Latin: worthy of love); Blanche (white (pure));

- Occupations, for example George means "earth-worker", i.e., "farmer".[12]

- Circumstances of birth, for example:

- Objects, for example Peter means "rock" and Edgar means "rich spear".[15][16]

- Physical characteristics, for example Calvin means "bald".[17]

- Variations on another name, especially to change the sex of the name (Pauline, Georgia) or to adapt from another language (for instance, the names Francis or Francisco that come from the name Franciscus meaning "Frank or Frenchman").[18][19][20]

- Surnames, Such names can honour other branches of a family, where the surname would not otherwise be passed down (e.g., the mother's maiden surname). Modern examples include:

- Many were adopted from the 17th century in England to show respect to notable ancestry, usually given to nephews or male grandchildren of members of the great families concerned, from which the usage spread to general society. This was regardless of whether the family name concerned was in danger of dying out, for example with Howard, a family with many robust male lines over history. Notable examples include

- Howard, from the Howard family, Dukes of Norfolk;

- Courtenay, from the surname of the Earls of Devon;

- Trevor, from the Welsh chieftain Tudor Trevor, lord of Hereford;[24]

- Clifford, from the Barons Clifford;

- Digby, from the family of Baron Digby/Earl of Bristol;

- Shirley (originally a man's forename), from the Shirley family, Earls Ferrer;

- Percy, from the Percy Earls and Dukes of Northumberland;

- Lindsay, from that noble Scottish family, Earls of Crawford;

- Graham, from that noble Scottish family, Dukes of Montrose;

- Eliot, from the Eliot family, Earls of St Germans;

- Herbert, from the Herbert family, Earls of Pembroke;

- Russell, from the Russell family, Earls and Dukes of Bedford;

- Stanley, from the Stanley family, Earls of Derby;

- Vernon, Earl of Shipbrook

- Dillon, the Irish family of Dillon, Viscount Dillon

- Places, for example Brittany[25] and Lorraine.[26]

- Time of birth, for example, day of the week, as in Kofi Annan, whose given name means "born on Friday",[27] or the holiday on which one was born, for example, the name Natalie meaning "born on Christmas day" in Latin[28] (Noel (French "Christmas"), a name given to males born at Christmas); also April, May, or June.

- Combination of the above, for example the Armenian name Sirvart means "love rose".[29]

In many cultures, given names are reused, especially to commemorate ancestors or those who are particularly admired, resulting in a limited repertoire of names that sometimes vary by orthography.

The most familiar example of this, to Western readers, is the use of Biblical and saints' names in most of the Christian countries (with Ethiopia, in which names were often ideals or abstractions—Haile Selassie, "power of the Trinity"; Haile Miriam, "power of Mary"—as the most conspicuous exception). However, the name Jesus is considered taboo or sacrilegious in some parts of the Christian world, though this taboo does not extend to the cognate Joshua or related forms which are common in many languages even among Christians. In some Spanish-speaking countries, the name Jesus is considered a normal given name.

Similarly, the name Mary, now popular among Christians, particularly Roman Catholics, was considered too holy for secular use until about the 12th century. In countries that particularly venerated Mary, this remained the case much longer; in Poland, until the arrival in the 17th century of French queens named Marie.[30]

Most common given names in English (and many other European languages) can be grouped into broad categories based on their origin:

- Hebrew names, most often from the Bible, are very common in, or are elements of names used in historically Christian countries. Some have elements meaning "God", especially "Eli". Examples: Michael, Joshua, Daniel, Joseph, David, Adam, Samuel, Elizabeth, Hannah and Mary. There are also a handful of names in use derived from the Aramaic, particularly the names of prominent figures in the New Testament—such as Thomas, Martha and Bartholomew.

- All of the Semitic peoples of history and the present day use at least some names constructed like these in Hebrew (and the ancient Hebrews used names not constructed like these—such as Moses, probably an Egyptian name related to the names of Pharaohs like Thutmose and Ahmose). The Muslim world is the best-known example (with names like Saif-al-din, "sword of the faith", or Abd-Allah, "servant of God"), but even the Carthaginians had similar names: cf. Hannibal, "the grace of god" (in this case not the Abrahamic deity God, but the deity—probably Melkart—whose title is normally left untranslated, as Baal).

- Germanic names are characteristically warlike; roots with meanings like "glory", "strength", and "will" are common. The "-bert" element common in many such names comes from beraht, which means "bright". Examples: Robert, Edward, Roger, Richard, Albert, Carl, Alfred, Rosalind, Emma, Emmett, Eric and Matilda.

- French forms of Germanic names. Since the Norman conquest of England, many English-given names of Germanic origin are used in their French forms. Examples: Charles, Henry, William.

- Slavic names may be of peaceful character, the compounds being derived from the word roots meaning "to protect", "to love", "peace", "to praise [gods]", or "to give". Examples: Milena, Vesna, Bohumil, Dobromir, Svetlana, Vlastimil. Other names have a warlike character and are built of words meaning "fighter", "war", or "anger". Examples: Casimir, Vladimir, Sambor, Wojciech and Zbigniew. Many of them derive from the root word "slava" ("glory"): Boleslav, Miroslav, Vladislav, Radoslav, Slavomir and Stanislav. Those derived from root word "mir" ("world, peace") are also popular: Casimir, Slavomir, Radomir, Vladimir, Miroslav, Jaczemir.

- Celtic names are sometimes anglicised versions of Celtic forms, but the original form may also be used. Examples: Alan, Brian, Brigid, Mórag, Ross, Logan, Ciarán, Jennifer, and Seán. These names often have origins in Celtic words, as Celtic versions of the names of internationally known Christian saints, as names of Celtic mythological figures, or simply as long-standing names whose ultimate etymology is unclear.

- Greek names may be derived from the history and mythology of Classical Antiquity or be derived from the New Testament and early Christian traditions. Such names are often, but not always, anglicised. Examples: Helen, Stephen, Alexander, Andrew, Peter, Gregory, George, Christopher, Margaret, Nicholas, Jason, Timothy, Chloe, Zoë, Katherine, Penelope and Theodore.

- Latin names can also be adopted unchanged, or modified; in particular, the inflected element can be dropped, as often happens in borrowings from Latin to English. Examples: Laura, Victoria, Mark (Latin Marcus), Justin (Latin Justinus), Paul (Lat. Paulus), Julius, Julia, Cecilia, Felix, Vivian, Pascal (not a traditional-type Latin name, but the adjective-turned-name paschalis, meaning 'of Easter' (Pascha)).

- Word names come from English vocabulary words. Feminine names of this sort—in more languages than English, and more cultures than Europe alone—frequently derive from nature, flowers, birds, colours, or gemstones. Examples include Jasmine, Lavender, Dawn, Daisy, Rose, Iris, Petunia, Rowan, Jade, and Violet. Male names of this sort are less common—examples like Hunter and Fischer, or names associated with strong animals, such as Bronco and Wolf. (This is more common in some other languages, such as Northern Germanic and Turkish).

- Trait names most conspicuously include the Christian virtues, mentioned above, and normally used as feminine names (such as the three Christian virtues—Faith, Hope, and Charity).

- Diminutives are sometimes used to distinguish between two or more people with the same given name. In English, Robert may be changed to "Robbie" or Thomas changed to "Tommy". In German the names Hänsel and Gretel (as in the famous fairy tale) are the diminutive forms of Johann and Margarete. Examples: Vicky, Cindy, Tommy, Abby, Allie.

- Shortened names (see nickname) are generally nicknames of a longer name, but they are instead given as a person's entire given name. For example, a man may simply be named "Jim", and it is not short for James. Examples: Beth, Ben, Zach, Tom.

- Feminine variations exist for many masculine names, often in multiple forms. Examples: Charlotte, Stephanie, Victoria, Philippa, Jane, Jacqueline, Josephine, Danielle, Paula, Pauline, Patricia, Francesca.

Frequently, a given name has versions in many languages. For example, the biblical name Susanna also occurs in its original biblical Hebrew version, Shoshannah, its Spanish and Portuguese version Susana, its French version, Suzanne, its Polish version, Zuzanna, or its Hungarian version, Zsuzsanna.

East Asia

[edit]Despite the uniformity of Chinese surnames, some Chinese given names are fairly original because Chinese characters can be combined extensively. Unlike European languages, with their Biblical and Greco-Roman heritage, the Chinese language does not have a particular set of words reserved for given names: any combination of Chinese characters can theoretically be used as a given name. Nonetheless, a number of popular characters commonly recur, including "Strong" (伟, Wěi), "Learned" (文, Wén), "Peaceful" (安, Ān), and "Beautiful" (美, Měi). Despite China's increasing urbanization, several names such as "Pine" (松, Sōng) or "Plum" (梅, Méi) also still reference nature.

Most Chinese given names are two characters long and—despite the examples above—the two characters together may mean nothing at all. Instead, they may be selected to include particular sounds, tones, or radicals; to balance the Chinese elements of a child's birth chart; or to honor a generation poem handed down through the family for centuries. Traditionally, it is considered an affront, not an honor, to have a newborn named after an older relative and so full names are rarely passed down through a family in the manner of American English Seniors, Juniors, III, etc. Similarly, it is considered disadvantageous for the child to bear a name already made famous by someone else through romanizations, where a common name like Liu Xiang may be borne by tens of thousands.

Korean names and Vietnamese names are often simply conventions derived from Classical Chinese counterparts.[citation needed]

Many female Japanese names end in -ko (子), usually meaning "child" on its own. However, the character when used in given names can have a feminine (adult) connotation.

In many Westernised Asian locations, many Asians also have an unofficial or even registered Western (typically English) given name, in addition to their Asian given name. This is also true for Asian students at colleges in countries such as the United States, Canada, and Australia as well as among international businesspeople. [citation needed]

Gender

[edit]Most names in English are traditionally masculine (Hugo, James, Harold) or feminine (Daphne, Charlotte, Jane), but there are unisex names as well, such as Jordan, Jamie, Jesse, Morgan, Leslie/Lesley, Joe/Jo, Jackie, Pat, Dana, Alex, Chris/Kris, Randy/Randi, Lee, etc. Often, use for one gender is predominant. Also, a particular spelling is often more common for either men or women, even if the pronunciation is the same.

Many culture groups, past and present, did not or do not gender their names strongly; thus, many or all of their names are unisex. On the other hand, in many languages including most Indo-European languages (but not English), gender is inherent in the grammar. Some countries have laws preventing unisex names, requiring parents to give their children sex-specific names.[31] Names may have different gender connotations from country to country or language to language.

Within anthroponymic classification, names of human males are called andronyms (from Ancient Greek ἀνήρ / man, and ὄνυμα [ὄνομα] / name),[32] while names of human females are called gynonyms (from Ancient Greek γυνή / woman, and ὄνυμα [ὄνομα] / name).[33]

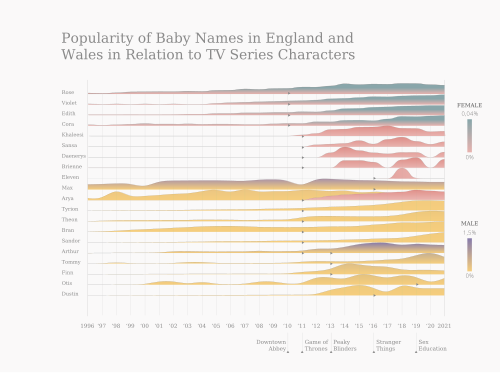

Popularity

[edit]

The popularity (frequency) distribution of given names typically follows a power law distribution.

Since about 1800 in England and Wales and in the U.S., the popularity distribution of given names has been shifting so that the most popular names are losing popularity. For example, in England and Wales, the most popular female and male names given to babies born in 1800 were Mary and John, with 24% of female babies and 22% of male babies receiving those names, respectively.[34] In contrast, the corresponding statistics for England and Wales in 1994 were Emily and James, with 3% and 4% of names, respectively. Not only have Mary and John gone out of favour in the English-speaking world, but the overall distribution of names has also changed significantly over the last 100 years for females, but not for males. This has led to an increasing amount of diversity for female names.[35]

Choice of names

[edit]Education, ethnicity, religion, class and political ideology affect parents' choice of names. Politically conservative parents choose common and traditional names, while politically liberal parents may choose the names of literary characters or other relatively obscure cultural figures.[36] Devout members of religions often choose names from their religious scriptures. For example, Hindu parents may name a daughter Saanvi after the goddess, Jewish parents may name a boy Isaac after one of the earliest ancestral figures, and Muslim parents may name a boy Mohammed after the prophet Mohammed.

There are many tools parents can use to choose names, including books, websites and applications. An example is the Baby Name Game that uses the Elo rating system to rank parents preferred names and help them select one.[37]

Influence of popular culture

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2015) |

Popular culture appears to have an influence on naming trends, at least in the United States and United Kingdom. Newly famous celebrities and public figures may influence the popularity of names. For example, in 2004, the names "Keira" and "Kiera" (anglicisation of Irish name Ciara) respectively became the 51st and 92nd most popular girls' names in the UK, following the rise in popularity of British actress Keira Knightley.[38] In 2001, the use of Colby as a boys' name for babies in the United States jumped from 233rd place to 99th, just after Colby Donaldson was the runner-up on Survivor: The Australian Outback.[citation needed] Also, the female name "Miley" which before was not in the top 1000 was 278th most popular in 2007, following the rise to fame of singer-actress Miley Cyrus (who was named Destiny at birth).[39]

Characters from fiction also seem to influence naming. After the name Kayla was used for a character on the American soap opera Days of Our Lives, the name's popularity increased greatly. The name Tammy, and the related Tamara became popular after the movie Tammy and the Bachelor came out in 1957. Some names were established or spread by being used in literature. Notable examples include Pamela, invented by Sir Philip Sidney for a pivotal character in his epic prose work, The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia; Jessica, created by William Shakespeare in his play The Merchant of Venice; Vanessa, created by Jonathan Swift; Fiona, a character from James Macpherson's spurious cycle of Ossian poems; Wendy, an obscure name popularised by J. M. Barrie in his play Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up; and Madison, a character from the movie Splash. Lara and Larissa were rare in America before the appearance of Doctor Zhivago, and have become fairly common since.

Songs can influence the naming of children. Jude jumped from 814th most popular male name in 1968 to 668th in 1969, following the release of the Beatles' "Hey Jude". Similarly, Layla charted as 969th most popular in 1972 after the Eric Clapton song. It had not been in the top 1,000 before.[39] Kayleigh became a particularly popular name in the United Kingdom following the release of a song by the British rock group Marillion. Government statistics in 2005 revealed that 96% of Kayleighs were born after 1985, the year in which Marillion released "Kayleigh". [citation needed]

Popular culture figures need not be admirable in order to influence naming trends. For example, Peyton came into the top 1000 as a female given name for babies in the United States for the first time in 1992 (at #583), immediately after it was featured as the name of an evil nanny in the film The Hand That Rocks the Cradle.[39] On the other hand, historical events can influence child-naming. For example, the given name Adolf has fallen out of use since the end of World War II in 1945.

In contrast with this anecdotal evidence, a comprehensive study of Norwegian first name datasets[40] shows that the main factors that govern first name dynamics are endogenous. Monitoring the popularity of 1,000 names over 130 years, the authors have identified only five cases of exogenous effects, three of them are connected to the names given to the babies of the Norwegian royal family.

20th century African-American names

[edit]Since the civil rights movement of 1950–1970, African-American names given to children have strongly mirrored sociopolitical movements and philosophies in the African-American community. Since the 1970s neologistic (creative, inventive) practices have become increasingly common and the subject of academic study.[41]

See also

[edit]- Hypocorism or pet name

- List of most popular given names (in many countries and cultures)

- Maiden and married names

- Name day

- Onomastics

- Personal name

- Praenomen

- Pseudonym

- Saint's name

- Slave name

- Thai name – somewhat special treatment of given names

- Theophoric name

- Unisex name

- Bilingual tautological given names

Notes

[edit]- ^ However, the family name – given name order is used only in informal or traditional contexts. The official naming order in Austria and Bavaria is given name – family name.

- ^ Protesting Swedish naming laws, in 1996, two parents attempted to name their child Brfxxccxxmnpcccclllmmnprxvclmnckssqlbb11116, stating that it was "a pregnant, expressionistic development that we see as an artistic creation".[8]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Grigg, John (2 November 1991). "The Times".

In the last century and well into the present one, grown-up British people, with rare exceptions, addressed each other by their surnames. What we now call first names (then Christian names) were very little used outside the family. Men who became friends would drop the Mr and use their bare surnames as a mark of intimacy: e.g. Holmes and Watson. First names were only generally used for, and among, children. Today we have gone to the other extreme. People tend to be on first-name terms from the moment of introduction, and surnames are often hardly mentioned. Moreover, first names are relentlessly abbreviated, particularly in the media: Susan becomes Sue, Terrence Terry and Robert Bob not only to friends and relations, but to millions who know these people only as faces and/or voices.

quoted in Burchfield, R. W. (1996). The New Fowler's Modern English Usage (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 512. ISBN 978-0-19-969036-7. - ^ "A name given to a person at birth or at baptism, as distinguished from a surname" – according to the American Heritage Dictionary Archived 11 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "WAG 25-02-07-b: SSN Applicants with Spanish Surnames". Illinois Department of Human Services.

- ^ Coates, Richard (1992), "Onomastics", The Cambridge History of the English Language, vol. 4, Cambridge University Press, pp. 346–347, ISBN 978-0-521-26477-8

- ^ "How The Double-Name Trend Started And Stayed In The South". Southern Living. 19 October 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ Section 3: NAMES BY ADAPTATION

- ^ "Naming Conventions; Use of Full Legal Name on All USCIS Issued Documents" (PDF). 13 September 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ "BBC NEWS - Entertainment - Baby named Metallica rocks Sweden". 4 April 2007.

- ^ Igor Katsev. "Origin and Meaning of Clement". MFnames.com. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- ^ Igor Katsev. "Origin and Meaning of Clemens". MFnames.com. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- ^ Cassell's Latin Dictionary, Marchant, J.R.V, & Charles, Joseph F., (Eds.), Revised Edition, 1928

- ^ Mike Campbell. "Meaning, Origin and History of the Name George". Behind the Name. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

- ^ Mike Campbell. "Meaning, Origin and History of the Name Thomas". Behind the Name. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

- ^ Mike Campbell. "Meaning, Origin and History of the Name Quintus". Behind the Name. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

- ^ Mike Campbell. "Meaning, Origin and History of the Name Edgar". Behind the Name. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

- ^ Mike Campbell. "Meaning, Origin and History of the Name Peter". Behind the Name. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

- ^ Mike Campbell. "Meaning, Origin and History of the Name Calvin". Behind the Name. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

- ^ Igor Katsev. "Origin and Meaning of Francis". MFnames.com. Archived from the original on 1 March 2011. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- ^ Igor Katsev. "Origin and Meaning of Francisco". MFnames.com. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- ^ Igor Katsev. "Origin and Meaning of Franciscus". MFnames.com. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- ^ Igor Katsev. "Origin and Meaning of Winston". MFnames.com. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- ^ Igor Katsev. "Origin and Meaning of Harrison". MFnames.com. Archived from the original on 27 May 2011. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- ^ Igor Katsev. "Origin and Meaning of Ross". MFnames.com. Archived from the original on 27 May 2011. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- ^ Trevors, whose descendant Trevor Charles Roper became Lord Dacre in 1786

- ^ Igor Katsev. "Origin and Meaning of Brittany". MFnames.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2009. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- ^ Mike Campbell. "Meaning, Origin and History of the Name Lorraine". Behind the Name. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- ^ Mike Campbell. "Meaning, Origin and History of the Name Kofi". Behind the Name. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- ^ Igor Katsev. "Origin and Meaning of Natalie". MFnames.com. Archived from the original on 7 September 2008. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- ^ Mike Campbell. "Meaning, Origin and History of the Name Sirvart". Behind the Name. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- ^ "Witamy". #Polska. Archived from the original on 3 April 2009. Retrieved 19 August 2006.

- ^ "Unisex Baby Names Are Illegal In These 4 Countries". HuffPost. 19 September 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ Room 1996, p. 6.

- ^ Barolini 2005, p. 91, 98.

- ^ "First Name Popularity in England and Wales over the Past Thousand Years".

- ^ "Names". Analytical Visions. 13 November 2006.

- ^ J. Eric Oliver, Thomas Wood, Alexandra Bass. "Liberellas versus Konservatives: Social Status, Ideology, and Birth Names in the United States" Presented at Archived 13 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine the 2013 Midwestern Political Science Association Annual Meeting

- ^ "Baby Name Game". Archived from the original on 29 March 2014.

- ^ "Babies' Names 2004". National Statistics Online. 5 January 2005. Archived from the original on 27 July 2005.

- ^ a b c "Popular Baby Names", Social Security Administration, US.

- ^ Kessler, David A.; Maruvka, Yosi E.; Ouren, Jøergen; Shnerb, Nadav M. (20 June 2012). "You Name It – How Memory and Delay Govern First Name Dynamics". PLOS ONE. 7 (6) e38790. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...738790K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038790. PMC 3380031. PMID 22745679.

- ^ Gaddis, S. (2017). "How Black Are Lakisha and Jamal? Racial Perceptions from Names Used in Correspondence Audit Studies". Sociological Science. 4: 469–489. doi:10.15195/v4.a19.

Sources

[edit]- Barolini, Teodolinda, ed. (2005). Medieval Constructions in Gender And Identity: Essays in Honor of Joan M. Ferrante. Tempe: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. ISBN 978-0-86698-337-2.

- Bourin, Monique; Martínez Sopena, Pascual, eds. (2010). Anthroponymie et migrations dans la chrétienté médiévale [Anthroponymy and Migrations in Medieval Christianity]. Madrid: Casa de Velázquez. ISBN 978-84-96820-33-3.

- Bruck, Gabriele vom; Bodenhorn, Barbara, eds. (2009) [2006]. An Anthropology of Names and Naming (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.[permanent dead link]

- Fraser, Peter M. (2000). "Ethnics as Personal Names". Greek Personal Names: Their Value as Evidence (PDF). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 149–157. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- Room, Adrian (1996). An Alphabetical Guide to the Language of Name Studies. Lanham and London: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-3169-8.

- Ziolkowska, Magdalena (2011). "Anthroponomy as an Element Identifying National Minority". Eesti ja Soome-Ugri Keeleteaduse Ajakiri. 2 (1): 383–398. doi:10.12697/jeful.2011.2.1.25. Archived from the original on 19 March 2024.

External links

[edit] given name (P735) (see uses)

given name (P735) (see uses)

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Given Name Frequency Project — Analysis of long-term trends in given names in England and Wales. Includes downloadable datasets of names for people interested in studying given name trends.

- NameVoyager Archived 30 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine — Visualization showing the frequency of the Top 1000 American baby names throughout history.

- U.S. Census Bureau: Distribution of Names Files — Large ranked list of male and female given names in addition to last names.

- Popular Baby Names — The Social Security Administration page for Popular U.S. Baby Names.

- Muslim Names — Islamic names with Audio Voice for pronunciation of Arabic names.

- Why Most European Names Ending in A Are Female — Article on Namepedia about gender and naming.

- Name Design Archived 23 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine — How to make unique name design and create name art.

Given name

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Fundamentals

Etymology and core concept

The term given name denotes a personal identifier conferred upon an individual, typically by parents or guardians at or shortly after birth, to distinguish them from others within their familial or communal group. This core function arises from the human need for precise individual reference in social coordination, predating formalized family names in most cultures and serving as the primary means of personal address in small-scale societies. In linguistic terms, it precedes any inherited surname in name sequences prevalent in Western traditions, functioning as the initial component of a full personal name.[7] Etymologically, "given name" entered American English usage between 1820 and 1830, emphasizing the act of bestowal as opposed to inheritance, with "given" deriving from Old English giefan meaning "to give" or "confer," underscoring the parental agency in name assignment. The concept aligns with broader onomastic practices where personal names originated from descriptive, occupational, or relational terms in proto-languages, evolving into standardized forms by the early modern period to facilitate record-keeping and legal identity. For instance, ancient naming systems, such as those in Sumerian cuneiform records from circa 3000 BCE, employed single personal identifiers without familial qualifiers, reflecting smaller population densities where additional distinction was unnecessary.[7][8]Distinction from family names and titles

A given name, also referred to as a forename or personal name, is the designation assigned to an individual at birth or shortly thereafter to uniquely identify them within their family or social group, distinct from a family name (surname or last name), which is inherited and shared among relatives to signify lineage or clan affiliation.[9][10] This distinction arises from historical naming practices where given names served to differentiate siblings or kin bearing the same family identifier, as seen in records from early modern Europe where multiple children in a household might share a surname but receive unique given names like "John" or "Elizabeth."[11] In legal contexts, such as birth certificates or official documents in jurisdictions like Canada, given names encompass one or more personal identifiers preceding the surname, excluding any inherited family designation.[12][13] Family names, by contrast, typically originate from patronymic, toponymic, or occupational roots and are passed down patrilineally or matrilineally, functioning as a collective marker rather than an individual distinguisher; for instance, in Western naming conventions, the sequence is given name followed by family name (e.g., "Jane Doe"), whereas East Asian conventions often reverse this to family name first (e.g., "Doe Jane"), yet the functional separation persists.[14][11] This separation ensures administrative clarity in census, taxation, and inheritance systems, where conflating the two could obscure genealogical or proprietary claims; empirical data from national registries, such as those maintained by the U.S. Social Security Administration, demonstrate that given names evolve individually over time via nicknames or legal changes, while family names remain stable indicators of descent.[15] Titles, including honorifics (e.g., Mr., Ms., Dr.) or nobility designations (e.g., Sir, Baron), differ fundamentally as they are non-hereditary prefixes or suffixes denoting social rank, professional qualification, or courtesy, not integral to the core personal or familial identity.[16][17] Unlike given or family names, titles are situational and revocable—conferred by achievement, appointment, or convention—and are omitted in formal legal naming fields; for example, a physician's full legal name remains "John Smith" irrespective of the "Dr." prefix used in professional correspondence.[18][19] In bibliographic and archival standards, titles are cataloged separately from names to avoid conflation, as they do not alter the underlying anthroponymic structure but merely contextualize it.[17] This delineation prevents titles from being mistaken for permanent identifiers, as evidenced in international passport and visa protocols where only given and family names are mandated for identity verification.[12]Structural Variations

Ordering in different cultures

In Western cultures, including those of Europe, North America, and regions colonized or heavily influenced by them, the standard order places the given name(s) before the family name. This convention structures full names as [given name(s)] [family name], as seen in English-speaking countries where individuals are formally identified as, for example, "Elizabeth Alexandra Mary Windsor" for the late Queen Elizabeth II. The practice emphasizes the personal identifier preceding the inherited lineage marker, a pattern solidified in documentation and social usage by the medieval period in much of Europe.[20] In contrast, East Asian cultures predominantly follow the reverse order, with the family name preceding the given name, a tradition rooted in Confucian emphasis on familial and ancestral priority dating back over two millennia. In China, the surname (known as xing) is listed first, followed by the one- or two-character given name (ming), as in "Xi Jinping," where "Xi" denotes the family clan. Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and Taiwan adhere to similar conventions: Japanese names like "Abe Shinzō" place the surname "Abe" first in native contexts, while Korean examples such as "Kim Jong-un" follow suit, with "Kim" as the widespread surname. This Eastern order is the default in domestic legal documents, media, and everyday address within these societies.[21][22][23] Globalization introduces variations, particularly in international or English-language settings. East Asian individuals may adopt Western order (given name first) in passports, academic publications, or business cards to align with global norms—Japan's government, for instance, permitted optional reversal in official romanization since 2019, though native media retains surname-first. However, this adaptation is not universal; Chinese state media and Korean official records preserve the traditional sequence to maintain cultural integrity. In Hispanic cultures, such as Spain and Latin America, given names precede compound family names (paternal then maternal surnames), as in "Gabriel García Márquez," upholding a given-first structure despite multiple familial elements.[24]| Region/Culture | Standard Order | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Western (e.g., English, French) | Given name(s) then family name | John Fitzgerald Kennedy[20] |

| Chinese | Family name then given name | Deng Xiaoping[21] |

| Japanese | Family name then given name | Tanaka Kazuki[25] |

| Korean | Family name then given name(s) | Park Ji-sung[23] |

| Spanish-speaking | Given name(s) then paternal/maternal surnames | Frida Kahlo y Calderón[21] |

Compound and hyphenated forms

Compound given names, also known as multiple or double given names, combine two or more distinct name elements into a single personal name, often to honor multiple relatives, saints, or cultural figures, and may or may not use a hyphen for separation.[26] These forms treat the entire construction as one indivisible unit, distinguishing them from separate middle names.[27] Historically, compound given names trace back to ancient Indo-European traditions, with examples in Sanskrit such as Devadatta ("given by god") and Devarāja ("god-king"), where elements fused to convey descriptive or theophoric meanings.[26] Similar structures appear in Avestan Iranian names, reflecting early linguistic compounding practices that integrated roots for identity or divine attributes.[26] In medieval and early modern Europe, particularly among Catholic populations, hyphenated forms proliferated to commemorate multiple religious patrons; French naming customs, for instance, routinely assigned names like Pierre-Marie to boys, blending apostolic and Marian references regardless of gender associations.[27] Cultural variations persist regionally. In Romance-language countries, such as France, Spain, and their former colonies, hyphenated given names remain prevalent, often drawing from Catholic saints—examples include Spanish María José (honoring Mary and Joseph) or Juan Felipe (John and Philip).[23] French tradition continues this, with compounds like Jean-Luc or Anne-Sophie common into the 21st century, reflecting ongoing religious and familial influences.[27] In Germanic contexts, such as Germany or Scandinavia, hyphenation occurs but emphasizes familial tribute, as in Anna-Lena or Karl-Friedrich, though less rigidly tied to ecclesiastical figures.[27] English-speaking cultures show lower adoption, favoring single names or non-hyphenated middles, with rare compounds like Mary-Beth appearing in rural or conservative U.S. Southern traditions but not achieving widespread use.[23] Legally, compound given names are registered as unified entities in many jurisdictions, avoiding subdivision in official documents; for example, French civil records treat Marie-Pierre as one name, permitting its use without abbreviation.[27] This contrasts with surname hyphenation trends, which surged in the 1980s–1990s among English-speakers for marital equity but waned due to administrative complexity, indirectly influencing perceptions of given-name compounds as cumbersome.[28] Overall, their persistence in continental Europe underscores cultural continuity in personal nomenclature, driven by tradition rather than modern egalitarian shifts.[23]Initials, diminutives, and nicknames

Initials refer to the abbreviated first letters of given names or middle names, often employed in formal, professional, or official contexts to distinguish individuals or maintain brevity. In English-speaking countries, particularly the United States during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, businessmen and public figures were frequently identified by their first initial, middle initial, and surname in print, such as J.P. Morgan or A.G. Bell, to avoid confusion among those sharing common surnames or to convey authority and efficiency in documentation.[29] This practice traces back to 19th-century British elites and persisted in American business and military nomenclature for precision in records, though full given names are now more common in casual usage.[30] Diminutives are shortened or modified forms of given names, typically conveying affection, familiarity, or smallness, and are derived phonetically from the original name through suffixes like -ie, -y, or -o, or by truncation. Examples in English include William shortened to Will, Bill, or Billy; Robert to Rob, Bob, or Bobby; and Margaret to Meg, Maggie, or Peggy, with some irregular forms arising from historical rhyming patterns dating to the 13th century.[31] These forms are primarily used informally among family and close associates, and their prevalence varies culturally; for instance, Russian naming features extensive diminutives like Sasha for Aleksandr or Katya for Yekaterina, reflecting relational intimacy.[32] In linguistic terms, diminutives modify the root to express endearment without altering core meaning, though overuse in adulthood may imply immaturity in professional settings.[33] Nicknames encompass informal alternatives to given names that may or may not derive from them, often bestowed by peers based on physical traits, personality, achievements, or events rather than phonetic variation. Unlike diminutives, which retain audible links to the original (e.g., Charlie from Charles), nicknames can be unrelated, such as "Ike" for Dwight D. Eisenhower from his middle name or "The Boss" for Bruce Springsteen reflecting leadership persona.[34] They serve social functions like group cohesion or memorability but can carry pejorative connotations if mocking; historically, 18th- and 19th-century English nicknames included "Archie" for Archibald or "Babe" for Barbara, used in familial or community records.[35] Cultural norms influence acceptance: in some Latin American or Slavic societies, affectionate nicknames persist into professional life, while Anglo-American contexts favor them less formally to preserve given-name dignity.[36]Legal Framework

Global naming laws and restrictions

In Denmark, the Personal Names Act mandates that given names conform to established linguistic and cultural norms, with parents required to select from a pre-approved list of approximately 7,000 names or seek special approval for others; unapproved names risk rejection if they include numbers, symbols, resemble surnames, fail to indicate gender, or could expose the child to ridicule or discomfort.[37] This framework, enforced by local authorities within six months of birth, prioritizes the child's long-term social integration over parental creativity.[38] Germany's civil registry offices (Standesämter) evaluate given names under principles derived from constitutional parental rights and child welfare protections, rejecting those that do not clearly signal gender, mimic family names, incorporate brands, titles, or place names, or foreseeably impair the child's emotional or social development—such as the 2008 denial of "Google" for evoking commercial association.[39] Recent reforms effective May 1, 2025, maintain these scrutiny standards while expanding options for compound surnames, but given name restrictions persist to safeguard against unconventional choices.[40] New Zealand operates without an explicit list of banned names but empowers the Registrar-General to decline registrations deemed offensive, frivolous, or likely to cause official confusion or personal hardship, as affirmed in a 2008 Family Court ruling that temporarily made a nine-year-old girl named "Talula Does the Hula from Hawaii" a ward of the state to enable renaming amid risks of bullying.[41] Subsequent cases, including 2024 rejections of names like "King," cannabis strain references, and royal titles such as "Queen V," underscore enforcement against perceived pretension or vulgarity.[42]| Country | Key Restrictions on Given Names | Rationale and Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Portugal | Limited to Portuguese or biblical origins; must clearly indicate gender; no nicknames or inventions | Prevents ambiguity or cultural discord; e.g., diminutives like "Tom" for "Thomas" disallowed.[43] |

| France | Prohibited if contrary to child's interests or excessively ridiculous under Civil Code Article 57 | Protects welfare; e.g., "Nutella" rejected in 2015 for commercial connotation, "Fraise" (strawberry) denied for whimsy.[44] |

| China | Restricted to standardized characters from a Ministry-approved set of about 8,000–12,000 for household registration compatibility | Ensures administrative processability; rare or invented characters banned since 2013 reforms to curb system overload.[45] |

| Saudi Arabia | Forbid names blaspheming Islam, implying divinity, or contradicting religious values | Upholds Sharia; e.g., "Messiah" or "Linda" (non-Arabic) rejected for cultural or doctrinal incompatibility.[44] |

Procedures for changes and disputes

Procedures for changing a given name typically require filing a formal petition with a local court or civil registry authority, demonstrating residency in the jurisdiction, and providing supporting documentation such as a birth certificate. In the United States, petitioners must appear before a judge, who evaluates the request for fraudulent intent or public safety risks before granting approval, often after publication of notice in a newspaper to allow objections.[48] The process may take 10 to 60 days depending on the state, with fees around $65 in jurisdictions like New York City, and requires updating vital records post-approval.[49] Courts generally approve changes for personal reasons, marriage, or adoption but deny those implying criminal evasion or deception.[50] In civil law countries, procedures are often more restrictive, mandating a "serious and substantial reason" such as trauma associated with the original name, with court proceedings required for given name alterations. For instance, in Germany, changes to first names involve application to the Standesamt (civil registry), potentially escalating to administrative appeal or court if denied, effective under updated naming laws as of May 1, 2025, which simplify declarations but retain oversight for appropriateness.[40] Similarly, in the Netherlands, judicial approval is necessary, emphasizing evidence of lasting detriment from the current name.[51] Disputes over given names, particularly for minors, arise commonly between unmarried or separated parents, where the birthing parent often registers the name first but faces challenge via court petition if contested. Resolution involves family court adjudication, prioritizing the child's best interest, such as avoiding confusion or cultural harm, with either party able to file for a name change hearing.[52] In cases of registry rejection—prevalent in countries like Sweden or Denmark with strict naming laws—parents may appeal administratively or judicially, citing precedents where courts overturned bans on unconventional names absent evidence of detriment.[53] For adults, disputes during name change petitions, such as third-party objections on grounds of trademark similarity or fraud, are addressed through evidentiary hearings, where the petitioner bears the burden of proof.[50]Cultural and Historical Contexts

Origins in major civilizations

In ancient Mesopotamia, personal names attested in cuneiform tablets from the Early Dynastic period (c. 2900–2350 BCE) frequently featured theophoric elements invoking deities such as Enlil or Inanna, often structured as prayers or declarative sentences like "Enlil-has-given-life" to express divine favor or protection.[54] Sumerian names emphasized qualities, professions, or origins, while Akkadian variants incorporated verbal forms; female names tended toward simpler, profane descriptors referring to objects or attributes.[55] These names served to affirm social roles and lineage continuity in a polytheistic society where identity tied directly to communal and divine hierarchies.[56] Ancient Egyptian naming practices, evident from the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BCE), assigned individuals a single primary name at birth, often a descriptive noun, adjective, or theophoric phrase such as Neferet ("beautiful woman") or User ("strong"), reflecting attributes, aspirations, or appeals to gods like Ra or Osiris for protection and prosperity.[57] Names held metaphysical power, integral to one's ka (life force) and afterlife preservation, with deliberate erasure from monuments as a severe sanction for crimes against the state or ma'at (cosmic order).[58] Differentiation among name-sharers relied on epithets, titles, or parentage rather than multiple names, underscoring a cultural emphasis on singular, potent identity.[59] In ancient China, given names (ming) emerged by the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE), typically comprising one or two characters selected for phonetic harmony, numerological auspiciousness, or symbolic virtues like strength or longevity, while adhering to taboos prohibiting replication of rulers' names to avoid presumption of equality.[60] Oracle bone inscriptions reveal early examples tied to ancestral cults and seasonal births, evolving into compounds by the Zhou period (1046–256 BCE) that encoded generational markers within clans.[61] This system prioritized familial harmony and imperial deference over individual uniqueness. Vedic India (c. 1500–500 BCE) featured given names drawn from Sanskrit roots denoting divine attributes, natural forces, or moral qualities, such as those invoking Agni (fire god) or Indra, without formalized surnames; identity derived from gotra (lineage clans) or paternal lineage.[62] Rigvedic hymns and texts like the Arthashastra later document names as ritual invocations for prosperity, with no evidence of hereditary fixed tags until post-Vedic eras, reflecting a society where personal nomenclature reinforced dharma (cosmic duty) and varna (social order).[63] Ancient Greek personal names, traceable to the Mycenaean era (c. 1600–1100 BCE) via Linear B tablets, consisted of single compounds blending roots for heroism, divinity, or virtues—e.g., Achilleus from achos (pain) and laos (people)—predominating by the Archaic period (c. 800–480 BCE) as unique identifiers without routine patronymics.[64] Theophoric formations with Zeus or Apollo underscored piety, while female names often adapted male elements with suffixes like -o for endearment, prioritizing euphony and mythic resonance in a culture valuing oral epic traditions.[65] Roman given names, or praenomina, originated in the Regal period (c. 753–509 BCE) as a restricted set of about 18 masculine forms (e.g., Gaius, Marcus) drawn from Etruscan influences and Indo-European roots denoting birth order or augury, used exclusively within gentes (clans) to signal kinship and inheritance rights. Women typically received a feminized version of the paternal nomen without a distinct praenomen, emphasizing collective family identity over personal distinction in a patriarchal republic.[66]Regional practices and evolutions

In Europe, given name practices originated in antiquity with simple, often descriptive or theophoric names, evolving through Christianization to favor saints' names like Maria or Johannes, which dominated until the 19th century due to religious influence on baptismal rites.[67] By the Middle Ages, naming after godparents or deceased relatives became common in Western Europe, reflecting familial and communal ties, while Eastern Orthodox traditions emphasized apostolic names such as Peter or Anna.[68] Secularization from the 20th century onward reduced religious dominance, with countries like France restricting saintly names post-1966 to promote diversity, leading to rises in nature-inspired or invented names.[69] East Asian conventions prioritize meaningful characters in given names, typically one or two syllables following the family name. In China, given names often convey aspirations like strength (e.g., Qiang) or harmony (e.g., He), selected from a vast pool of hanzi characters shared across generations via generational poems in some clans.[70] Japanese given names, also post-surname, blend kanji for aesthetics or virtues, such as Hiroshi meaning "generous," with post-WWII Western influences introducing names like Kenji alongside traditional ones.[71] Korean practices mirror this, using hanja or native hangul for given names like Ji-hoon ("wisdom and merit"), though Romanization debates persist, with generational shifts favoring unique combinations amid urbanization.[72] Islamic traditions emphasize given names (ism) with positive connotations, often prefixed with Abd- (servant of) followed by one of Allah's attributes, such as Abdullah ("servant of God"), rooted in prophetic hadiths discouraging ill-omened names.[73] Names of prophets like Muhammad or Ibrahim prevail, selected at birth or akika ceremonies on the seventh day, reflecting theological priorities over familial repetition in regions from the Middle East to South Asia.[74] African practices vary tribally: Akan groups in Ghana assign day-born names like Kofi (boy born Friday), tying identity to birth circumstances for mnemonic and divinatory purposes, while Yoruba ceremonies eight days post-birth incorporate oriki praises into names denoting events or virtues.[75] Zulu naming anticipates traits or omens prenatally, evolving under colonial influences to blend with Christian names but retaining situational descriptors like Phumlani ("be at rest").[76] Latin American given names follow Iberian patterns, favoring Catholic saints like José or María, often compounded (e.g., María Guadalupe) to honor multiple devotions, with selection influenced by feast days or maternal vows.[77] In Mexico, indigenous roots persist in names like Xochitl ("flower"), revived post-20th-century mestizaje movements, though urban families increasingly adopt Spanish variants.[78] Globally, given name evolutions since the 20th century show convergence toward uniqueness, with popularity peaks inverting as names like Emma or Noah in the U.S. surge then decline due to parental aversion to commonality, modeled as negative frequency-dependent selection.[79] Media and migration drive this: Korean datasets reveal post-1950s diversification from Confucian repetition, while Quebec's French-only policies spurred invented forms like Océane.[80] In diverse regions, globalization amplifies cross-cultural borrowing, reducing traditional constraints—e.g., rising unisex options in Europe—but sustaining core practices like aspirational meanings in Asia amid 2020s data showing 20-30% novelty rates in urban cohorts.[81]Gender and Neutrality

Gendered naming conventions

Given names are predominantly gendered, with conventions associating specific forms, sounds, and usages to males or females based on linguistic patterns, historical precedents, and cultural norms that reinforce binary distinctions rooted in biological sex. These associations facilitate social signaling of gender from infancy, as names serve as proxies for sex in interactions where physical cues are absent. In most societies, over 90% of given names are used exclusively or nearly so for one sex, minimizing ambiguity and aligning with evolved preferences for clear gender categorization.[82] Phonological features systematically differentiate gendered names across languages. Male names tend to be shorter, monosyllabic, start with stressed syllables, and end in consonants, particularly obstruents or nasals, evoking perceptions of strength and solidity.[83] Female names, conversely, feature more vowels, higher pitch associations, and endings in fricatives or vowels like -a or -e, contributing to softer, lighter sonic profiles; for instance, in English and other Indo-European languages, names ending in vowels are a strong indicator of female usage.[84] Voiced initial phonemes, involving vocal cord vibration, further correlate with male names, while unvoiced sounds align more with female ones, patterns observable in datasets from multiple cultures.[85] Morphological markers reinforce these distinctions, particularly in inflected languages where names inflect according to grammatical gender matching biological sex. In Romance languages derived from Latin, feminine names often append -a (e.g., Anna, Isabella) to masculine bases ending in consonants or -o (e.g., Antonius to Antonia), a convention tracing to classical antiquity.[86] Similar patterns appear in other families: Slavic languages use suffixes like -a for females (e.g., Olga vs. Oleg), and Semitic languages employ non-concatenative morphology, such as vowel patterns or gemination, to mark gender (e.g., Arabic Yusuf to Yusra).[87] In South Asian cultures, prefixes or suffixes denote gender, as in Hindi-derived Vikram (male, implying valor) versus Vani (female, implying speech).[88] These markers are not arbitrary but arise from grammatical gender systems applied to proper nouns, ensuring names concord with adjectives and pronouns.[89] Historically, gendered conventions stem from naming after sex-specific figures—patriarchs, matriarchs, saints, or deities—cementing associations through repetition. Biblical names like David (male, from Hebrew "beloved") or Sarah (female, "princess") exemplify this, with exclusivity maintained via religious and familial transmission in Judeo-Christian traditions.[90] In Germanic naming from the early medieval period, deuterothemes (second elements in dithematic names) often determined gender, such as -ric for males (powerful ruler) versus -hild for females (battle), though single-element hypocoristics later blurred lines without altering core binaries.[90] Empirical analysis of U.S. naming from 1880 to 2016 reveals high stability in gender exclusivity, with parents avoiding androgynous options due to preferences for unambiguous sex signaling, a pattern driven by social conformity rather than legal mandate.[82] Cross-culturally, these conventions persist because they reduce cognitive load in gender attribution, supported by probabilistic learning from population-level usage data.[83] In contexts like professional or legal settings, gendered name conventions influence perceptions; for example, last-name-first address biases toward males, reflecting entrenched associations where male forenames evoke authority.[91] Exceptions occur via borrowing or innovation, but they rarely overturn entrenched patterns without cultural shifts, as seen in stable gender ratios for common names over centuries.[92]Rise of unisex and neutral options

In the United States, the proportion of babies receiving unisex given names—those used for both males and females—has risen markedly since the 1980s, reflecting shifts in parental naming preferences. Data from the Social Security Administration indicate that gender-neutral names increased by 88% between 1985 and 2015, with approximately 6% of infants given androgynous names in 2021, a fivefold increase from the 1.2% recorded in the 1880s.[93][94] Alternative analyses, using broader definitions of unisex names (those split roughly evenly between genders in usage), report 17% of 2023 births receiving such names, the highest on record.[95] Similar trends appear in the United Kingdom, where Office for National Statistics data from 1996 to 2013 show increasing overlap in top names for boys and girls, such as Alex and Jordan, though comprehensive unisex percentages remain lower than in the U.S. at around 5-7% in recent years.[96] Examples of rising unisex options include Riley, which ranked among the top 50 names for both genders by 2020, and Parker, given to over 6,000 U.S. babies in 2023 with a near-even split (62% male, 38% female).[97] This surge correlates with broader diversification in naming, where parents select from a growing pool of revived or invented neutral terms like Rowan, Sage, and Quinn, often drawn from nature, surnames, or occupations rather than traditional gendered roots.[98] Empirical tracking via name databases reveals that while some names maintain balanced usage over decades (e.g., Jessie at near 50-50 splits historically), many androgynous options experience tandem popularity peaks before drifting toward gender specialization, suggesting instability in true neutrality.[99][100] Explanations for this rise emphasize parental desires for flexibility amid evolving social norms, including reduced adherence to binary gender roles and a premium on individuality.[101] Studies attribute part of the trend to utilitarian motives, such as minimizing gender-based biases in professional contexts, where neutral names may confer advantages in fields like STEM for females.[102] However, longitudinal analyses challenge narratives tying the increase primarily to contemporary gender identity movements, noting that the pattern predates widespread nonbinary awareness and aligns more closely with general uniqueness-seeking behaviors, where unisex choices signal distinction without overt novelty.[103] Critics of expansive unisex adoption, drawing from naming dynamics research, argue that such names often fail to sustain ambiguity long-term due to innate parental preferences for clear gender signaling, potentially leading to cultural re-gendering over generations.[82][104] Despite these debates, the empirical trajectory shows continued growth into the 2020s, with neutral options comprising a record share of top-100 names in multiple countries.[105]Semantic and Symbolic Dimensions

Etymological meanings across languages

Given names derive etymologically from words signifying virtues, natural phenomena, kinship, or divine attributes in their originating languages, with meanings preserved or adapted as names spread across cultures. In Indo-European traditions, particularly Germanic branches, names often formed as compounds from Proto-Germanic elements denoting strength, peace, or protection, such as *berhtaz ("bright, famous") combined with *raginaz ("counsel") in names like Bertram.[67] These compounds reflect a custom of combining parental name stems to evoke aspirational qualities.[8] In Semitic languages like Hebrew, names frequently incorporate theophoric elements, as in David, from the root *d-w-d meaning "to love" or "beloved," linked to the noun *dôḏ ("beloved" or "uncle").[106] Similarly, Michael derives from Hebrew *mîḵāʾēl, meaning "who is like God," emphasizing divine incomparability. Greek names, such as Alexander, compound *aléxō ("to defend, protect") with *anḗr ("man"), yielding "defender of men," a motif of martial guardianship common in Hellenic onomastics.[107] Latin given names often stem from praenomina tied to augural or familial roots, with Julius possibly from *Iou- ("Jove") or a term for "youthful/downy-bearded," evoking vitality or divine patronage.[108] In Iranian Indo-European contexts, pre-Islamic names followed similar patterns, distinguishing short thematic names from compounds like *xšāyaθiya- ("king") elements, underscoring authority or heroism.[109] Across these families, Proto-Indo-European roots like *deiwos ("god") persist in theophoric forms, such as Germanic *Þeud- ("people, god"), illustrating deep linguistic continuity in name semantics.[110]| Language Family | Example Name | Etymological Meaning | Key Root(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semitic (Hebrew) | David | Beloved | *d-w-d (love) |

| Hellenic (Greek) | Alexander | Defender of men | *aléxō (defend) + *anḗr (man) |

| Germanic | Bertram | Bright raven (or counsel) | *berhtaz (bright) + *bram (raven) |

| Italic (Latin) | Julius | Youthful or of Jove | *Iou- (Jove) or juvenile |

| Iranian | Xšāyaθiya- compounds | Kingly rule | *xšā- (rule) |