Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

RGB color model

View on Wikipedia

The RGB color model is an additive color model[1] in which the red, green, and blue primary colors of light are added together in various ways to reproduce a broad array of colors. The name of the model comes from the initials of the three additive primary colors, red, green, and blue.[2]

The main purpose of the RGB color model is for the sensing, representation, and display of images in electronic systems, such as televisions and computers, though it has also been used in conventional photography and colored lighting. Before the electronic age, the RGB color model already had a solid theory behind it, based in human perception of colors.

RGB is a device-dependent color model: different devices detect or reproduce a given RGB value differently, since the color elements (such as phosphors or dyes) and their response to the individual red, green, and blue levels vary from manufacturer to manufacturer, or even in the same device over time. Thus an RGB value does not define the same color across devices without some kind of color management.[3][4]

Typical RGB input devices are color TV and video cameras, image scanners, and digital cameras. Typical RGB output devices are TV sets of various technologies (CRT, LCD, plasma, OLED, quantum dots, etc.), computer and mobile phone displays, video projectors, multicolor LED displays and large screens such as the Jumbotron. Color printers, on the other hand, are not RGB devices, but subtractive color devices typically using the CMYK color model.

Additive colors

[edit]| Color depth |

|---|

| Related |

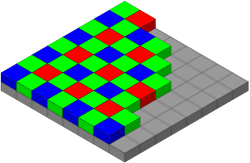

To form a color with RGB, three light beams (one red, one green, and one blue) must be superimposed (for example by emission from a black screen or by reflection from a white screen). Each of the three beams is called a component of that color, and each of them can have an arbitrary intensity, from fully off to fully on, in the mixture.

The RGB color model is additive in the sense that if light beams of differing color (frequency) are superposed in space their light spectra adds up, wavelength for wavelength, to make up a resulting, total spectrum.[5][6] This is in contrast to the subtractive color model, particularly the CMY Color Model, which applies to paints, inks, dyes and other substances whose color depends on reflecting certain components (frequencies) of the light under which they are seen.

In the additive model, if the resulting spectrum, e.g. of superposing three colors, is flat, white color is perceived by the human eye upon direct incidence on the retina. This is in stark contrast to the subtractive model, where the perceived resulting spectrum is what reflecting surfaces, such as dyed surfaces, emit. A dye filters out all colors but its own; two blended dyes filter out all colors but the common color component between them, e.g. green as the common component between yellow and cyan, red as the common component between magenta and yellow, and blue-violet as the common component between magenta and cyan. There is no common color component among magenta, cyan and yellow, thus rendering a spectrum of zero intensity: black.

Zero intensity for each component gives the darkest color (no light, considered the black), and full intensity of each gives a white; the quality of this white depends on the nature of the primary light sources, but if they are properly balanced, the result is a neutral white matching the system's white point. When the intensities for all the components are the same, the result is a shade of gray, darker, or lighter depending on the intensity. When the intensities are different, the result is a colorized hue, more or less saturated depending on the difference of the strongest and weakest of the intensities of the primary colors employed.

When one of the components has the strongest intensity, the color is a hue near this primary color (red-ish, green-ish, or blue-ish), and when two components have the same strongest intensity, then the color is a hue of a secondary color (a shade of cyan, magenta, or yellow). A secondary color is formed by the sum of two primary colors of equal intensity: cyan is green+blue, magenta is blue+red, and yellow is red+green. Every secondary color is the complement of one primary color: cyan complements red, magenta complements green, and yellow complements blue. When all the primary colors are mixed in equal intensities, the result is white.

The RGB color model itself does not define what is meant by red, green, and blue colorimetrically, and so the results of mixing them are not specified as absolute, but relative to the primary colors. When the exact chromaticities of the red, green, and blue primaries are defined, the color model then becomes an absolute color space, such as sRGB or Adobe RGB.

Physical principles for the choice of red, green, and blue

[edit]

The choice of primary colors is related to the physiology of the human eye; good primaries are stimuli that maximize the difference between the responses of the cone cells of the human retina to light of different wavelengths, and that thereby make a large color triangle.[7]

The normal three kinds of light-sensitive photoreceptor cells in the human eye (cone cells) respond most to yellow (long wavelength or L), green (medium or M), and violet (short or S) light (peak wavelengths near 570 nm, 540 nm and 440 nm, respectively[7]). The difference in the signals received from the three kinds allows the brain to differentiate a wide gamut of different colors, while being most sensitive (overall) to yellowish-green light and to differences between hues in the green-to-orange region.

As an example, suppose that light in the orange range of wavelengths (approximately 577 nm to 597 nm) enters the eye and strikes the retina. Light of these wavelengths would activate both the medium and long wavelength cones of the retina, but not equally—the long-wavelength cells will respond more. The difference in the response can be detected by the brain, and this difference is the basis of our perception of orange. Thus, the orange appearance of an object results from light from the object entering our eye and stimulating the different cones simultaneously but to different degrees.

Use of the three primary colors is not sufficient to reproduce all colors; only colors within the color triangle defined by the chromaticities of the primaries can be reproduced by additive mixing of non-negative amounts of those colors of light.[7][page needed]

History of RGB color model theory and usage

[edit]The RGB color model is based on the Young–Helmholtz theory of trichromatic color vision, developed by Thomas Young and Hermann von Helmholtz in the early to mid-nineteenth century, and on James Clerk Maxwell's color triangle that elaborated that theory (c. 1860).

Photography

[edit]The first experiments with RGB in early color photography were made in 1861 by Maxwell himself, and involved the process of combining three color-filtered separate takes.[1] To reproduce the color photograph, three matching projections over a screen in a dark room were necessary.

The additive RGB model and variants such as orange–green–violet were also used in the Autochrome Lumière color plates and other screen-plate technologies such as the Joly color screen and the Paget process in the early twentieth century. Color photography by taking three separate plates was used by other pioneers, such as the Russian Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky in the period 1909 through 1915.[8] Such methods lasted until about 1960 using the expensive and extremely complex tri-color carbro Autotype process.[9]

When employed, the reproduction of prints from three-plate photos was done by dyes or pigments using the complementary CMY model, by simply using the negative plates of the filtered takes: reverse red gives the cyan plate, and so on.

Television

[edit]Before the development of practical electronic TV, there were patents on mechanically scanned color systems as early as 1889 in Russia. The color TV pioneer John Logie Baird demonstrated the world's first RGB color transmission in 1928, and also the world's first color broadcast in 1938, in London. In his experiments, scanning and display were done mechanically by spinning colorized wheels.[10][11]

The Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) began an experimental RGB field-sequential color system in 1940. Images were scanned electrically, but the system still used a moving part: the transparent RGB color wheel rotating at above 1,200 rpm in synchronism with the vertical scan. The camera and the cathode-ray tube (CRT) were both monochromatic. Color was provided by color wheels in the camera and the receiver.[12][13][14] More recently, color wheels have been used in field-sequential projection TV receivers based on the Texas Instruments monochrome DLP imager.

The modern RGB shadow mask technology for color CRT displays was patented by Werner Flechsig in Germany in 1938.[15]

Personal computers

[edit]Personal computers of the late 1970s and early 1980s, such as the Apple II and VIC-20, use composite video. The Commodore 64 and the Atari 8-bit computers use S-Video derivatives. IBM introduced a 16-color scheme (4 bits—1 bit each for red, green, blue, and intensity) with the Color Graphics Adapter (CGA) for its IBM PC in 1981, later improved with the Enhanced Graphics Adapter (EGA) in 1984. The first manufacturer of a truecolor graphics card for PCs (the TARGA) was Truevision in 1987, but it was not until the arrival of the Video Graphics Array (VGA) in 1987 that RGB became popular, mainly due to the analog signals in the connection between the adapter and the monitor which allowed a very wide range of RGB colors. Actually, it had to wait a few more years because the original VGA cards were palette-driven just like EGA, although with more freedom than VGA, but because the VGA connectors were analog, later variants of VGA (made by various manufacturers under the informal name Super VGA) eventually added true-color. In 1992, magazines heavily advertised true-color Super VGA hardware.

RGB devices

[edit]RGB and displays

[edit]

One common application of the RGB color model is the display of colors on a cathode-ray tube (CRT), liquid-crystal display (LCD), plasma display, or organic light emitting diode (OLED) display such as a television, a computer's monitor, or a large scale screen. Each pixel on the screen is built by driving three small and very close but still separated RGB light sources. At common viewing distance, the separate sources are indistinguishable, which the eye interprets as a given solid color. All the pixels together arranged in the rectangular screen surface conforms the color image.

During digital image processing each pixel can be represented in the computer memory or interface hardware (for example, a graphics card) as binary values for the red, green, and blue color components. When properly managed, these values are converted into intensities or voltages via gamma correction to correct the inherent nonlinearity of some devices, such that the intended intensities are reproduced on the display.

The Quattron released by Sharp uses RGB color and adds yellow as a sub-pixel, supposedly allowing an increase in the number of available colors.

Video electronics

[edit]RGB is also the term referring to a type of component video signal used in the video electronics industry. It consists of three signals—red, green, and blue—carried on three separate cables/pins. RGB signal formats are often based on modified versions of the RS-170 and RS-343 standards for monochrome video. This type of video signal is widely used in Europe since it is the best quality signal that can be carried on the standard SCART connector.[16][17] This signal is known as RGBS (4 BNC/RCA terminated cables exist as well), but it is directly compatible with RGBHV used for computer monitors (usually carried on 15-pin cables terminated with 15-pin D-sub or 5 BNC connectors), which carries separate horizontal and vertical sync signals.

Outside Europe, RGB is not very popular as a video signal format; S-Video takes that spot in most non-European regions. However, almost all computer monitors around the world use RGB.

Video framebuffer

[edit]A framebuffer is a digital device for computers which stores data in the so-called video memory (comprising an array of Video RAM or similar chips). This data goes either to three digital-to-analog converters (DACs) (for analog monitors), one per primary color or directly to digital monitors. Driven by software, the CPU (or other specialized chips) write the appropriate bytes into the video memory to define the image. Modern systems encode pixel color values by devoting 8 bits to each of the R, G, and B components. RGB information can be either carried directly by the pixel bits themselves or provided by a separate color look-up table (CLUT) if indexed color graphic modes are used.

A CLUT is a specialized RAM that stores R, G, and B values that define specific colors. Each color has its own address (index)—consider it as a descriptive reference number that provides that specific color when the image needs it. The content of the CLUT is much like a palette of colors. Image data that uses indexed color specifies addresses within the CLUT to provide the required R, G, and B values for each specific pixel, one pixel at a time. Of course, before displaying, the CLUT has to be loaded with R, G, and B values that define the palette of colors required for each image to be rendered. Some video applications store such palettes in PAL files (Age of Empires game, for example, uses over half-a-dozen[18]) and can combine CLUTs on screen.

- RGB24 and RGB32

This indirect scheme restricts the number of available colors in an image CLUT—typically 256-cubed (8 bits in three color channels with values of 0–255)—although each color in the RGB24 CLUT table has only 8 bits representing 256 codes for each of the R, G, and B primaries, making 16,777,216 possible colors. However, the advantage is that an indexed-color image file can be significantly smaller than it would be with only 8 bits per pixel for each primary.

Modern storage, however, is far less costly, greatly reducing the need to minimize image file size. By using an appropriate combination of red, green, and blue intensities, many colors can be displayed. Current typical display adapters use up to 24 bits of information for each pixel: 8-bit per component multiplied by three components (see the Numeric representations section below (24 bits = 2563, each primary value of 8 bits with values of 0–255). With this system, 16,777,216 (2563 or 224) discrete combinations of R, G, and B values are allowed, providing millions of different (though not necessarily distinguishable) hue, saturation and lightness shades. Increased shading has been implemented in various ways, some formats such as .png and .tga files among others using a fourth grayscale color channel as a masking layer, often called RGB32.

For images with a modest range of brightnesses from the darkest to the lightest, 8 bits per primary color provides good-quality images, but extreme images require more bits per primary color as well as the advanced display technology. For more information see High Dynamic Range (HDR) imaging.

Nonlinearity

[edit]In classic CRT devices, the brightness of a given point over the fluorescent screen due to the impact of accelerated electrons is not proportional to the voltages applied to the electron gun control grids, but to an expansive function of that voltage. The amount of this deviation is known as its gamma value (), the argument for a power law function, which closely describes this behavior. A linear response is given by a gamma value of 1.0, but actual CRT nonlinearities have a gamma value around 2.0 to 2.5.

Similarly, the intensity of the output on TV and computer display devices is not directly proportional to the R, G, and B applied electric signals (or file data values which drive them through digital-to-analog converters). On a typical standard 2.2-gamma CRT display, an input intensity RGB value of (0.5, 0.5, 0.5) only outputs about 22% of full brightness (1.0, 1.0, 1.0), instead of 50%.[19] To obtain the correct response, a gamma correction is used in encoding the image data, and possibly further corrections as part of the color calibration process of the device. Gamma affects black-and-white TV as well as color. In standard color TV, broadcast signals are gamma corrected.

RGB and cameras

[edit]

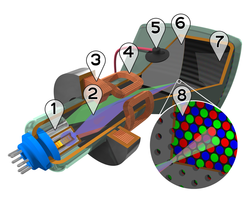

In color television and video cameras manufactured before the 1990s, the incoming light was separated by prisms and filters into the three RGB primary colors feeding each color into a separate video camera tube (or pickup tube). These tubes are a type of cathode-ray tube, not to be confused with that of CRT displays.

With the arrival of commercially viable charge-coupled device (CCD) technology in the 1980s, first, the pickup tubes were replaced with this kind of sensor. Later, higher scale integration electronics was applied (mainly by Sony), simplifying and even removing the intermediate optics, thereby reducing the size of home video cameras and eventually leading to the development of full camcorders. Current webcams and mobile phones with cameras are the most miniaturized commercial forms of such technology.

Photographic digital cameras that use a CMOS or CCD image sensor often operate with some variation of the RGB model. In a Bayer filter arrangement, green is given twice as many detectors as red and blue (ratio 1:2:1) in order to achieve higher luminance resolution than chrominance resolution. The sensor has a grid of red, green, and blue detectors arranged so that the first row is RGRGRGRG, the next is GBGBGBGB, and that sequence is repeated in subsequent rows. For every channel, missing pixels are obtained by interpolation in the demosaicing process to build up the complete image. Also, other processes used to be applied in order to map the camera RGB measurements into a standard color space as sRGB.

RGB and scanners

[edit]In computing, an image scanner is a device that optically scans images (printed text, handwriting, or an object) and converts it to a digital image which is transferred to a computer. Among other formats, flat, drum and film scanners exist, and most of them support RGB color. They can be considered the successors of early telephotography input devices, which were able to send consecutive scan lines as analog amplitude modulation signals through standard telephonic lines to appropriate receivers; such systems were in use in press since the 1920s to the mid-1990s. Color telephotographs were sent as three separated RGB filtered images consecutively.

Currently available scanners typically use CCD or contact image sensor (CIS) as the image sensor, whereas older drum scanners use a photomultiplier tube as the image sensor. Early color film scanners used a halogen lamp and a three-color filter wheel, so three exposures were needed to scan a single color image. Due to heating problems, the worst of them being the potential destruction of the scanned film, this technology was later replaced by non-heating light sources such as color LEDs.

Numeric representations

[edit]

|

|

A color in the RGB color model is described by indicating how much of each of the red, green, and blue is included. The color is expressed as an RGB triplet (r,g,b), each component of which can vary from zero to a defined maximum value. If all the components are at zero the result is black; if all are at maximum, the result is the brightest representable white.

These ranges may be quantified in several different ways:

- From 0 to 1, with any fractional value in between. This representation is used in theoretical analyses, and in systems that use floating point representations.

- Each color component value can also be written as a percentage, from 0% to 100%.

- In computers, the component values are often stored as unsigned integer numbers in the range 0 to 255, the range that a single 8-bit byte can offer. These are often represented as either decimal or hexadecimal numbers.

- High-end digital image equipment are often able to deal with larger integer ranges for each primary color, such as 0..1023 (10 bits), 0..65535 (16 bits) or even larger, by extending the 24 bits (three 8-bit values) to 32-bit, 48-bit, or 64-bit units (more or less independent from the particular computer's word size).

For example, brightest saturated red is written in the different RGB notations as:

Notation RGB triplet Arithmetic (1.0, 0.0, 0.0) Percentage (100%, 0%, 0%) Digital 8-bit per channel (255, 0, 0)

#FF0000 (hexadecimal)Digital 12-bit per channel (4095, 0, 0)

#FFF000000Digital 16-bit per channel (65535, 0, 0)

#FFFF00000000Digital 24-bit per channel (16777215, 0, 0)

#FFFFFF000000000000Digital 32-bit per channel (4294967295, 0, 0)

#FFFFFFFF0000000000000000

In many environments, the component values within the ranges are not managed as linear (that is, the numbers are nonlinearly related to the intensities that they represent), as in digital cameras and TV broadcasting and receiving due to gamma correction, for example.[20] Linear and nonlinear transformations are often dealt with via digital image processing. Representations with only 8 bits per component are considered sufficient if gamma correction is used.[21]

Following is the mathematical relationship between RGB space to HSI space (hue, saturation, and intensity: HSI color space):

If , then .

Color depth

[edit]The RGB color model is one of the most common ways to encode color in computing, and several different digital representations are in use. The main characteristic of all of them is the quantization of the possible values per component (technically a sample) by using only integer numbers within some range, usually from 0 to some power of two minus one (2n − 1) to fit them into some bit groupings. Encodings of 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, and 16 bits per color are commonly found; the total number of bits used for an RGB color is typically called the color depth.

Geometric representation

[edit]

Since colors are usually defined by three components, not only in the RGB model, but also in other color models such as CIELAB and Y'UV, among others, then a three-dimensional volume is described by treating the component values as ordinary Cartesian coordinates in a Euclidean space. For the RGB model, this is represented by a cube using non-negative values within a 0–1 range, assigning black to the origin at the vertex (0, 0, 0), and with increasing intensity values running along the three axes up to white at the vertex (1, 1, 1), diagonally opposite black.

An RGB triplet (r,g,b) represents the three-dimensional coordinate of the point of the given color within the cube or its faces or along its edges. This approach allows computations of the color similarity of two given RGB colors by simply calculating the distance between them: the shorter the distance, the higher the similarity. Out-of-gamut computations can also be performed this way.

Colors in web-page design

[edit]Initially, the limited color depth of most video hardware led to a limited color palette of 216 RGB colors, defined by the Netscape Color Cube. The web-safe color palette consists of the 216 (63) combinations of red, green, and blue where each color can take one of six values (in hexadecimal): #00, #33, #66, #99, #CC or #FF (based on the 0 to 255 range for each value discussed above). These hexadecimal values = 0, 51, 102, 153, 204, 255 in decimal, which = 0%, 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, 100% in terms of intensity. This seems fine for splitting up 216 colors into a cube of dimension 6. However, lacking gamma correction, the perceived intensity on a standard 2.5 gamma CRT / LCD is only: 0%, 2%, 10%, 28%, 57%, 100%. See the actual web safe color palette for a visual confirmation that the majority of the colors produced are very dark.[22]

With the predominance of 24-bit displays, the use of the full 16.7 million colors of the HTML RGB color code no longer poses problems for most viewers. The sRGB color space (a device-independent color space[23]) for HTML was formally adopted as an Internet standard in HTML 3.2,[24][25] though it had been in use for some time before that. All images and colors are interpreted as being sRGB (unless another color space is specified) and all modern displays can display this color space (with color management being built in into browsers[26][27] or operating systems[28]).

The syntax in CSS is:

rgb(#,#,#)

where # equals the proportion of red, green, and blue respectively. This syntax can be used after such selectors as "background-color:" or (for text) "color:".

Wide gamut color is possible in modern CSS,[29] being supported by all major browsers since 2023.[30][31][32]

For example, a color on the DCI-P3 color space can be indicated as:

color(display-p3 # # #)

where # equals the proportion of red, green, and blue in 0.0 to 1.0 respectively.

Color management

[edit]Proper reproduction of colors, especially in professional environments, requires color management of all the devices involved in the production process, many of them using RGB. Color management results in several transparent conversions between device-independent (sRGB, XYZ, L*a*b*)[23] and device-dependent color spaces (RGB and others, as CMYK for color printing) during a typical production cycle, in order to ensure color consistency throughout the process. Along with the creative processing, such interventions on digital images can damage the color accuracy and image detail, especially where the gamut is reduced. Professional digital devices and software tools allow for 48 bpp (bits per pixel) images to be manipulated (16 bits per channel), to minimize any such damage.

ICC profile compliant applications, such as Adobe Photoshop, use either the Lab color space or the CIE 1931 color space as a Profile Connection Space when translating between color spaces.[33]

RGB model and luminance–chrominance formats relationship

[edit]All luminance–chrominance formats used in the different TV and video standards such as YIQ for NTSC, YUV for PAL, YDBDR for SECAM, and YPBPR for component video use color difference signals, by which RGB color images can be encoded for broadcasting/recording and later decoded into RGB again to display them. These intermediate formats were needed for compatibility with pre-existent black-and-white TV formats. Also, those color difference signals need lower data bandwidth compared to full RGB signals.

Similarly, current high-efficiency digital color image data compression schemes such as JPEG and MPEG store RGB color internally in YCBCR format, a digital luminance–chrominance format based on YPBPR. The use of YCBCR also allows computers to perform lossy subsampling with the chrominance channels (typically to 4:2:2 or 4:1:1 ratios), which reduces the resultant file size.

See also

[edit]- CMY color model

- CMYK color model

- Color theory

- Colour banding

- Complementary colors

- DCI-P3 – defined using RGB, but may be signalled as YCbCr or RGB

- List of color palettes

- ProPhoto RGB color space

- RG color models

- RGBA color model

- scRGB

- TSL color space

References

[edit]- ^ a b Robert Hirsch (2004). Exploring Colour Photography: A Complete Guide. Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 1-85669-420-8.

- ^ Fairman, Hugh S.; Brill, Michael H.; Hemmendinger, Henry (February 1997). "How the CIE 1931 color-matching functions were derived from Wright-Guild data". Color Research & Application. 22 (1): 11–23. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6378(199702)22:1<11::AID-COL4>3.0.CO;2-7.

The first of the resolutions offered to the 1931 meeting defined the color-matching functions of the soon-to-be-adopted standard observer in terms of Guild's spectral primaries centered on wavelengths 435.8, 546.1, and 700nm. Guild approached the problem from the viewpoint of a standardization engineer. In his mind, the adopted primaries had to be producible with national-standardizing-laboratory accuracy. The first two wavelengths were mercury excitation lines, and the last named wavelength occurred at a location in the human vision system where the hue of spectral lights was unchanging with wavelength. Slight inaccuracy in production of the wavelength of this spectral primary in a visual colorimeter, it was reasoned, would introduce no error at all.

- ^ GrantMeStrength (30 December 2021). "Device-Dependent Color Spaces - Win32 apps". learn.microsoft.com. Retrieved 2022-10-24.

- ^ Crean, Buckley. "Device Independent Color—Who Wants It?" (PDF). SPIE. 2171: 267. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2023-02-04. Retrieved 2022-10-24.

- ^ Charles A. Poynton (2003). Digital Video and HDTV: Algorithms and Interfaces. Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN 1-55860-792-7.

- ^ Nicholas Boughen (2003). Lightwave 3d 7.5 Lighting. Wordware Publishing, Inc. ISBN 1-55622-354-4.

- ^ a b c R. W. G. Hunt (2004). The Reproduction of Colour (6th ed.). Chichester UK: Wiley–IS&T Series in Imaging Science and Technology. ISBN 0-470-02425-9.

- ^ Photographer to the Tsar: Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii Library of Congress.

- ^ "The Evolution of Color Pigment Printing". Artfacts.org. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

- ^ John Logie Baird, Television Apparatus and the Like, U.S. patent, filed in U.K. in 1928.

- ^ Baird Television: Crystal Palace Television Studios. Previous color television demonstrations in the U.K. and U.S. had been via closed circuit.

- ^ "Color Television Success in Test". NY Times. 1940-08-30. p. 21. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ^ "CBS Demonstrates Full Color Television," Wall Street Journal, Sept. 5, 1940, p. 1.

- ^ "Television Hearing Set". NY Times. 1940-11-13. p. 26. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ^ Morton, David L. (1999). "Television Broadcasting". A History of Electronic Entertainment Since 1945 (PDF). IEEE. ISBN 0-7803-9936-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 6, 2009.

- ^ Domestic and similar electronic equipment interconnection requirements: Peritelevision connector (PDF). British Standards Institution. 15 June 1998. ISBN 0580298604.

- ^ "Composite video vs composite sync and Demystifying RGB video". www.retrogamingcables.co.uk. Retrieved 2022-10-24.

- ^ By directory search

- ^ Steve Wright (2006). Digital Compositing for Film and Video. Focal Press. ISBN 0-240-80760-X.

- ^ Edwin Paul J. Tozer (2004). Broadcast Engineer's Reference Book. Elsevier. ISBN 0-240-51908-6.

- ^ John Watkinson (2008). The art of digital video. Focal Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-240-52005-6.

- ^ For a side-by-side comparison of proper colors next to their equivalent lacking proper gamma correction, see Doucette, Matthew (15 March 2006). "Color List". Xona Games.

- ^ a b "Device-Independent Color Spaces - MATLAB & Simulink". www.mathworks.com.

- ^ "HTML 3.2 Reference Specification". 14 January 1997.

- ^ "A Standard Default Color Space for the Internet - sRGB". W3C.

- ^ "Color management in Internet". www.color-management-guide.com.

- ^ "How to setup proper color management in your web browser - Greg Benz Photography". gregbenzphotography.com. April 27, 2021.

- ^ "About Color Management". support.microsoft.com.

- ^ "Wide Gamut Color in CSS with Display-P3". March 2, 2020.

- ^ ""color" Can I use... Support tables for HTML5, CSS3, etc". Can I use...

- ^ "Wide Gamut Color in CSS with Display-P3". March 2, 2020.

- ^ "CSS color() function". Can I use...

- ^ King, James C. "Why Color Management?" (PDF). International Color Consortium. Retrieved 2008-04-16.

The two PCS's in the ICC system are CIE-XYZ and CIELAB

External links

[edit]RGB color model

View on GrokipediaCore Concepts

Additive Color Mixing

The RGB color model operates on the principle of additive color mixing, where colors are produced by the superposition of red, green, and blue light intensities, enabling the creation of a wide gamut of perceptible colors. In this system, light from these three primaries is combined such that increasing the intensity of each component brightens the resulting color, with equal maximum intensities of all three primaries yielding white light. This approach leverages the linearity of light addition, allowing any color within the model's gamut to be approximated by adjusting the relative intensities of the primaries.[3][8] The theoretical foundation for additive color mixing in RGB is provided by Grassmann's laws, formulated in 1853, which describe the empirical rules governing how mixtures of colored lights are perceived. These laws include proportionality (scaling intensities scales the perceived color), additivity (the mixture of two colors added to a third equals the sum of their separate mixtures with the third), and the invariance of matches under certain conditions, ensuring that color mixtures behave as vector additions in a three-dimensional space. For instance, pure red is represented by intensities R=1, G=0, B=0, while varying these values—such as R=1, G=1, B=0 for yellow—spans the color space through linear combinations, approximating the full range of human color perception enabled by the visual system's trichromacy.[9] In contrast to additive mixing, subtractive color models like CMY (cyan, magenta, yellow) used in pigments and printing absorb light wavelengths, starting from white and yielding darker colors as components are added, which is why additive mixing is particularly suited for light-emitting devices such as displays where light is directly projected and combined. The perceived color in additive mixing can be conceptually expressed as the linear superposition of the primary spectra weighted by their intensities:where is the resulting spectral power distribution, , , and are the spectral distributions of the red, green, and blue primaries, and , , are their respective intensity scalars (normalized between 0 and 1). This equation underscores the model's reliance on additive principles without deriving from physical optics.[10][11][3]

Choice of RGB Primaries

The RGB color model is grounded in the trichromatic theory of human vision, which posits that color perception arises from three types of cone photoreceptors in the retina, each sensitive to different wavelength ranges of light. These include long-wavelength-sensitive (L) cones peaking around 564–580 nm (perceived as red), medium-wavelength-sensitive (M) cones peaking around 534–545 nm (perceived as green), and short-wavelength-sensitive (S) cones peaking around 420–440 nm (perceived as blue). This physiological basis directly informs the selection of red, green, and blue as primaries, as they align with the peak sensitivities of these cones, enabling efficient representation of the visible spectrum through additive mixing. The choice of RGB primaries is further guided by physical principles aimed at optimizing color reproduction. In the CIE 1931 color space, primaries are selected to maximize the gamut—the range of reproducible colors—while balancing luminous efficiency, where green contributes the most to perceived brightness due to the higher sensitivity of the human visual system to mid-wavelength light (corresponding to the Y tristimulus value in CIE XYZ). This selection ensures broad coverage of perceivable colors without excessive energy loss, as the primaries form a triangle in the chromaticity diagram that encompasses a significant portion of the spectral locus. Historically, the CIE standardized RGB primaries in 1931 based on color-matching experiments, defining monochromatic wavelengths at approximately 700 nm (red), 546.1 nm (green), and 435.8 nm (blue) to establish the CIE RGB color space. These evolved into modern standards like sRGB, proposed in 1996 by HP and Microsoft, which specifies primaries with chromaticities of red at x=0.6400, y=0.3300; green at x=0.3000, y=0.6000; and blue at x=0.1500, y=0.0600 in the CIE 1931 xy diagram, tailored for typical consumer displays and web use.[1] A key limitation of RGB primaries is metamerism, where distinct spectral distributions can produce identical color matches under one illuminant (e.g., daylight) but appear different under another (e.g., incandescent light), due to the incomplete spectral sampling by only three primaries. Primary selection also involves conceptual optimization to achieve perceptual uniformity, such as minimizing color differences measured along MacAdam ellipses—ellipsoidal regions in chromaticity space representing just-noticeable differences—to ensure even spacing of colors in human perception.Historical Development

Early Color Theory and Experiments

The foundations of the RGB color model trace back to early 19th-century physiological theories of vision. In 1801, Thomas Young proposed the trichromatic hypothesis, suggesting that human color perception arises from three distinct types of retinal receptors sensitive to different wavelength bands, providing the theoretical basis for using three primary colors to represent the full spectrum of visible hues.[12] This idea built on earlier observations of color mixing but shifted focus to the eye's internal mechanisms rather than purely physical properties of light.[13] Hermann von Helmholtz refined Young's hypothesis in the 1850s, elaborating it into a more detailed physiological model by classifying the three cone types as sensitive to red, green, and violet light, respectively, and emphasizing their role in additive color mixing to produce all perceivable colors.[14] Helmholtz's work integrated experimental data on color blindness and spectral responses, establishing the trichromatic framework as a cornerstone for subsequent RGB-based theories.[15] In 1853, Hermann Grassmann formalized the mathematical underpinnings of color mixing in his paper "Zur Theorie der Farbenmischung," proposing that colors could be represented as vectors in a three-dimensional linear space where any color is a linear combination of three primaries, adhering to laws of additivity, proportionality, and superposition.[16] This vector space model provided a rigorous algebraic structure for RGB representations, enabling quantitative predictions of color mixtures without relying solely on perceptual descriptions.[17] James Clerk Maxwell advanced these ideas through experimental demonstrations of additive color synthesis in the 1850s and 1860s. In his 1855 paper "Experiments on Colour," Maxwell described methods to mix colored lights to match spectral hues, confirming that red, green, and blue primaries could approximate a wide range of colors via superposition.[18] Building on this, Maxwell's 1860 paper "On the Theory of Compound Colours" detailed color-matching experiments using a divided disk and lanterns, further validating the trichromatic approach.[19] The culmination came in 1861, when Maxwell projected the first synthetic full-color image by superimposing red, green, and blue filtered projections of black-and-white photographs of a tartan ribbon, demonstrating practical additive synthesis at the Royal Institution.[20] Later in the 1880s, Arthur König and Conrad Dieterici conducted key measurements of spectral sensitivities in normal and color-deficient observers, estimating the response curves of the three cone types and confirming their peaks in the red, green, and blue regions of the spectrum. Their 1886 work, "Die Grundempfindungen in normalen und anormalen Farbsystemen," used flicker photometry on dichromats to isolate individual cone fundamentals, providing empirical support for the physiological basis of RGB primaries.[21] Despite these advances, early RGB theories faced limitations in representing the full gamut of human-perceivable colors, as real primaries like those chosen by Maxwell could not span the entire chromaticity space without negative coefficients.[22] This issue persisted into the 20th century, leading the International Commission on Illumination (CIE) in 1931 to define the XYZ color space with imaginary primaries that avoid negative values and encompass all visible colors, highlighting the incompleteness of spectral RGB models for absolute color specification.[23]Adoption in Photography

The adoption of RGB principles in photography marked a pivotal shift from monochrome to color imaging, building on foundational additive color theory. In 1907, the Lumière brothers introduced the Autochrome process, the world's first commercially viable color film, which employed an additive mosaic screen of potato starch grains dyed red, green, and blue-violet—approximating RGB primaries—to filter light onto a panchromatic silver halide emulsion. This innovation, comprising about 4 million grains per square inch, allowed the capture and viewing of full-color transparencies by recombining filtered light, though it required longer exposures than black-and-white film.[24] By the 1930s, subtractive processes incorporating RGB separations gained prominence, exemplified by Eastman Kodak's 1935 launch of Kodachrome, the first successful multilayer reversal film for amateurs. Developed by Leopold Mannes and Leopold Godowsky Jr., it used three panchromatic emulsion layers sensitized to red, green, and blue wavelengths via color couplers, producing cyan, magenta, and yellow dyes during controlled development to form positive transparencies. This RGB-based separation evolved from earlier additive experiments, enabling vibrant slides for 16mm cine and 35mm still photography without the need for multiple exposures. In the 1940s, three-color separation techniques became standard in commercial printing, where RGB-filtered negatives were used to create subtractive overlays in imbibition processes like Kodak's Dye Transfer, facilitating high-volume color reproduction for magazines and advertisements.[25][26][20] The transition to digital photography in the 1970s introduced sensor-based RGB capture, with Bryce E. Bayer's 1976 patent for the Bayer filter array revolutionizing image sensors. This mosaic pattern overlays red, green, and blue microlenses on a grid of photosites in CCD and CMOS devices—twice as many green for luminance sensitivity—capturing single-color data per pixel, which demosaicing algorithms then interpolate to yield complete RGB values. By the 1990s, this technology standardized in consumer digital cameras, such as early models from Kodak and Canon, outputting RGB-encoded images that bypassed film processing and enabled instant color photography for the masses.[27][20] Early additive RGB films faced technical hurdles, including color fringing from misalignment between the filter mosaic and emulsion layers, which caused edge artifacts in Autochrome plates due to imperfect registration during manufacturing or viewing.[28]Implementation in Television

The implementation of the RGB color model in television began with early mechanical experiments, notably John Logie Baird's 1928 demonstration of a color television system using a Nipkow disk divided into three sections with red, green, and blue filters to sequentially capture and display color images additively.[29] The transition to electronic television culminated in the 1953 NTSC standard approved by the FCC, which utilized shadow-mask cathode-ray tubes (CRTs) featuring RGB phosphors arranged in triads on the screen interior.[30] These CRTs incorporated three electron guns—one each for red, green, and blue—to generate and modulate the respective primary signals, with the shadow mask ensuring that each beam precisely excites only its corresponding phosphor dots, thereby producing the intended color at each pixel location.[31] For broadcast transmission within the limited 6 MHz channel bandwidth, the correlated RGB signals were transformed into the YIQ color space, where the luminance (Y) component, derived as a weighted sum of RGB (Y = 0.299R + 0.587G + 0.114B), occupied the full bandwidth for monochrome compatibility, while the chrominance (I and Q) components were modulated onto a 3.58 MHz subcarrier with reduced bandwidths (1.5 MHz for I and 0.5 MHz for Q) to exploit human vision's lower acuity for color details.[30] Additionally, gamma correction was introduced during this era to counteract the CRT's nonlinear power-law response (approximately γ ≈ 2.5), applying a pre-distortion (V_out = V_in^{1/γ}) in the camera chain to achieve linear light output matching scene reflectance.[30] In the 1960s, European systems like PAL (introduced in 1967) and SECAM (1967) retained RGB primaries closely aligned with NTSC specifications for compatibility in international production, but diverged in encoding: PAL alternated the phase of the chrominance subcarrier (4.43 MHz) between lines to mitigate hue errors, while SECAM sequentially transmitted frequency-modulated blue-luminance and red-luminance differences.[32] Studio equipment for these formats employed full-bandwidth RGB component signals—equivalent to 4:4:4 sampling in modern digital parlance—enabling uncompressed color handling during production, effects, and editing before conversion to the broadcast-encoded form.[33] The advent of digital high-definition television marked a key evolution, with ITU-R Recommendation BT.709 (adopted in 1990) establishing precise RGB colorimetry parameters, including primaries (x_r=0.64, y_r=0.33; x_g=0.30, y_g=0.60; x_b=0.15, y_b=0.06) and D65 white point, optimized for 1920×1080 progressive or interlaced displays in HDTV production and exchange. This standard facilitated the shift from analog RGB modulation to digital sampling while preserving the additive mixing principles for accurate color reproduction on CRT-based HDTV sets.Expansion to Computing

The expansion of the RGB color model into personal computing began in the late 1970s and early 1980s, as microcomputers transitioned from monochrome displays to basic color capabilities. Early systems like the Apple II (1977) supported limited RGB-based color through composite video outputs, but the IBM Personal Computer's introduction of the Color Graphics Adapter (CGA) in 1981 marked a pivotal shift for the emerging PC market. CGA introduced a 4-color mode at 320×200 resolution (black, cyan, magenta, and white), using 2 bits per pixel with RGBI signaling to approximate additive colors, enabling simple graphics and text in color for business and gaming applications.[34] This was followed by the Enhanced Graphics Adapter (EGA) in 1984, which expanded to 16 simultaneous colors from a palette of 64 (2 bits per RGB channel), supporting resolutions up to 640x350 and improving visual fidelity for productivity software.[35] By the mid-1980s, demand for richer visuals drove further advancements, culminating in IBM's Video Graphics Array (VGA) standard in 1987 with the PS/2 line. VGA introduced a 256-color palette derived from an 18-bit RGB space (6 bits per channel, yielding 262,144 possible colors) at 640x480 resolution, allowing more vibrant and detailed imagery through indexed color modes like Mode 13h.[36] In the early 1990s, Super VGA (SVGA) extensions from vendors like S3 Graphics enabled true color (24-bit RGB, or 8 bits per channel, supporting 16.7 million colors) at higher resolutions, such as 800x600 or 1024x768, facilitated by chips like the S3 928 (1991) with up to 4MB VRAM for direct color modes without palettes.[37] These developments standardized RGB as the foundational model for PC graphics hardware, bridging the gap from television-inspired analog signals to digital bitmap rendering. Key software milestones accelerated RGB's integration into computing workflows. Apple's Macintosh II, released in 1987, was the first Macintosh to support color displays via the AppleColor High-Resolution RGB Monitor, using 24-bit RGB for up to 16.7 million colors and enabling early desktop applications with full-color graphics.[38] Microsoft Windows 95 (1995) further popularized high-fidelity RGB by natively supporting 24-bit color depths, allowing seamless rendering of 16.7 million colors in graphical user interfaces and applications.[39] The release of OpenGL 1.0 in 1992 by Silicon Graphics, managed by the Khronos Group, provided a cross-platform API for 3D RGB rendering pipelines, standardizing vertex processing and framebuffer operations for real-time graphics.[40] Microsoft's DirectX 1.0 (1995) complemented this by offering Windows-specific APIs for RGB-based 2D and 3D acceleration, including DirectDraw for bitmap surfaces and Direct3D for scene composition. The evolution of graphics processing units (GPUs) in the late 1990s amplified RGB's role in real-time computing. NVIDIA's GeForce 256 (1999), the first GPU, integrated transform and lighting engines to handle complex RGB pixel shading at high speeds, evolving from fixed-function pipelines to programmable shaders for dynamic color blending and texturing.[41] This progression established RGB as the default for bitmap graphics in operating systems and software, profoundly impacting desktop publishing by enabling affordable color layout tools like Adobe PageMaker (1985 onward), which leveraged RGB monitors for WYSIWYG editing before CMYK conversion for print. The shift democratized visual content creation, transforming publishing from specialized typesetting to accessible digital workflows.[42]RGB in Devices

Display Technologies

The RGB color model is fundamental to the operation of various display technologies, where it enables the reproduction of a wide range of colors through the controlled emission or modulation of red, green, and blue light. In cathode-ray tube (CRT) displays, three separate electron beams, each modulated by the respective RGB signal, strike a phosphor-coated screen to produce light; the phosphors, such as those in the P22 standard, emit red, green, and blue light upon excitation, with a shadow mask ensuring precise alignment to prevent color fringing. This additive mixing allows CRTs to approximate the visible spectrum by varying beam intensities, achieving color gamuts close to the sRGB standard in consumer applications. Liquid crystal display (LCD) and light-emitting diode (LED)-backlit panels implement RGB through a matrix of subpixels, each filtered to transmit red, green, or blue wavelengths from a white backlight source. In these systems, thin-film transistor (TFT) arrays control the voltage applied to liquid crystals, modulating light transmission per subpixel to form full-color pixels; post-2010 advancements incorporate quantum dots as color converters to enhance gamut coverage, extending beyond traditional NTSC limits toward DCI-P3. LED backlights, often using white LEDs with RGB phosphors, provide higher efficiency and brightness compared to earlier CCFL sources. Organic light-emitting diode (OLED) displays utilize self-emissive RGB pixels, where organic materials in each subpixel emit light directly when an electric current is applied, eliminating the need for a backlight and enabling perfect blacks through selective pixel deactivation. This structure offers superior contrast ratios and viewing angles, with white RGB (WRGB) variants—employing an additional white subpixel—improving power efficiency for brighter outputs without sacrificing color accuracy. OLEDs typically achieve wide color gamuts, covering up to 95% of Rec. 2020 (as of 2024), due to the precise emission spectra of organic emitters.[43] To account for the nonlinear response of these display devices, where light output is not linearly proportional to input voltage, gamma encoding is applied in the RGB signal pipeline; a common gamma value of 2.2 compensates for this by encoding the signal such that the decoded output follows the device's power-law response curve. The decoding relationship is given by: where is the encoded voltage (0 to 1), is the linear light intensity, and is the display's gamma factor. This perceptual linearization ensures efficient use of bit depth and matches human vision's logarithmic sensitivity. In modern high dynamic range (HDR) displays, the RGB model is extended to support greater luminance ranges and bit depths, with the Rec. 2020 standard (published in 2012) defining wider primaries and a 10-bit or higher encoding to enable peak brightness exceeding 1000 nits while preserving color fidelity in both SDR and HDR content. These advancements, integrated into OLED and quantum-dot-enhanced LCDs, allow RGB-based systems to render over a billion colors with enhanced detail in shadows and highlights.Image Capture Systems

In digital cameras, the RGB color model is implemented through single-sensor designs that capture light via a color filter array (CFA) overlaid on the image sensor. The most prevalent CFA is the Bayer pattern, which arranges red, green, and blue filters in an RGGB mosaic, where green filters occupy half the pixels to align with human visual sensitivity. This setup allows each photosite to record intensity for only one color channel, producing a mosaiced image that requires subsequent processing to reconstruct full RGB values per pixel.[44] To obtain complete RGB data, demosaicing algorithms interpolate missing color values from neighboring pixels, employing techniques such as edge-directed interpolation to minimize artifacts like color aliasing. For instance, bilinear interpolation estimates values based on adjacent samples, while more advanced methods, like gradient-corrected linear interpolation, adapt to local image structures for higher fidelity. These processes ensure that the final RGB image approximates the scene's additive color mixing as captured by the sensor.[45] Scanners employ linear RGB CCD arrays to acquire color-separated signals, with mechanisms differing between flatbed and drum types. Flatbed scanners use a trilinear CCD array—comprising three parallel rows of sensors, each dedicated to red, green, or blue—mounted on a movable carriage that scans beneath a glass platen, capturing reflected light in a single pass for efficient RGB separation. Drum scanners, in contrast, rotate the original around a light source while a fixed sensor head with photomultiplier tubes (one per RGB channel) reads transmitted or reflected light, enabling higher resolution and reduced motion artifacts through precise color isolation via fiber optics.[46][47] Post-capture processing in image acquisition systems includes white balance adjustment, which normalizes RGB channel gains to compensate for varying illuminants, ensuring neutral reproduction of whites. This involves scaling the raw signals—such as multiplying red by a factor of 1.32 and blue by 1.2 under daylight—based on sensor responses to a reference gray card, thereby aligning the captured RGB values to a standard illuminant like D65. Algorithms automate this by estimating illuminant color temperature and applying per-channel corrections.[48] Key advancements in RGB capture include the rise of CMOS sensors in the 1990s, which integrated analog-to-digital conversion on-chip, reducing costs and power consumption compared to traditional CCDs while supporting Bayer-filtered RGB acquisition in consumer devices. Additionally, RAW formats preserve the sensor's linear RGB data—captured as grayscale intensities per filter without gamma correction—retaining 12-bit or higher precision for flexible post-processing.[49] Challenges in RGB image capture arise from noise in low-light conditions, where photon shot noise and read noise disproportionately affect channels, leading to imbalances such as elevated green variance due to its higher sensitivity, which can distort color fidelity. Spectral mismatch between sensor filters and ideal RGB primaries further complicates accurate reproduction, as real-world filters exhibit overlapping responses (e.g., root mean square errors of 0.02–0.03 in sensitivity estimation), causing metamerism under non-standard illuminants.[50][51]Digital Representation

Numeric Encoding Schemes

In digital imaging and computing, RGB colors are encoded using discrete numeric values to represent intensities for each channel, with the bit depth determining the precision and range of colors. The standard color depth for most consumer applications is 8 bits per channel (bpc), yielding a total of 24 bits per pixel and supporting 16,777,216 possible colors (2^8 × 3 channels). This encoding maps intensities to integer values from 0 (minimum) to 255 (maximum) per channel, providing sufficient gradation for typical displays while balancing storage efficiency.[52] Higher depths, such as 10 bpc for a 30-bit total, are employed in broadcast and professional video workflows to minimize visible banding in smooth gradients, offering 1,073,741,824 colors and improved dynamic range for transmission standards like those in digital television systems.[53] Key standards define specific encoding parameters, including gamut, transfer functions, and bit depths, to ensure consistent color reproduction across devices. The sRGB standard, proposed by Hewlett-Packard and Microsoft in 1996 and formalized by the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) in 1999 as IEC 61966-2-1, serves as the default for web and consumer electronics, using 8-bit integer encoding with values scaled from 0 to 255 and a gamma-corrected transfer function for perceptual uniformity. Adobe RGB (1998), introduced by Adobe Systems to accommodate wider color gamuts suitable for print production, employs similar 8-bit or 16-bit integer encoding but significantly expands the reproducible colors over sRGB, particularly in cyan-greens, while maintaining compatibility with standard RGB pipelines.[7][54] For professional photography requiring maximal color fidelity, ProPhoto RGB—developed by Kodak as an output-referred space—supports large gamuts exceeding Adobe RGB, typically encoded in 16-bit integer or floating-point formats to capture subtle tonal variations without clipping.[55] Quantization converts continuous or normalized values to discrete integers for storage. In linear RGB spaces, for a linear intensity normalized to [0, 1], the quantized value is , where is bits per channel. However, in gamma-encoded spaces like sRGB, linear intensities are first transformed using a transfer function (e.g., approximate gamma of 2.2) to perceptual values , then quantized as ; this ensures even perceptual distribution as per encoding standards.[56] Binary integer formats dominate for standard dynamic range (SDR) images, using fixed-point representation in the 0–255 scale for 8 bpc, while high dynamic range (HDR) applications employ floating-point encoding to handle values exceeding [0, 1], such as in OpenEXR files, which support 16-bit half-precision or 32-bit single-precision floats per channel for RGB data, enabling over 1,000 steps per f-stop in luminance.[57] File storage of RGB data must account for byte order to maintain portability across processor architectures. Little-endian order, common in x86 systems, stores the least significant byte first (e.g., for 16-bit channels, low byte precedes high byte), as seen in formats like BMP; big-endian reverses this, placing the most significant byte first, which is specified in headers for versatile formats like TIFF to allow cross-platform decoding without data corruption.[58]Geometric Modeling

The RGB color model is geometrically conceptualized as a unit cube in three-dimensional Cartesian space, with orthogonal axes representing the normalized intensities of the red (R), green (G), and blue (B) primary components, each ranging from 0 to 1. The vertex at the origin (0,0,0) corresponds to black, signifying the absence of light, while the opposing vertex at (1,1,1) denotes white, the maximum additive combination of the primaries. This cubic representation facilitates intuitive visualization of color mixtures, where any point within the cube defines a unique color through vector addition of the basis vectors along each axis.[59][60] As a vector space over the reals, , the RGB model treats colors as position vectors, enabling linear algebraic operations for color computation and manipulation. For instance, linear interpolation, or lerping, between two colors and produces a continuum of intermediate colors along the line segment connecting them, parameterized as: This operation yields smooth gradients essential for rendering transitions in graphics and imaging, leveraging the model's inherent linearity derived from additive light mixing.[61][62] The reproducible color gamut in RGB forms a polyhedral volume, which, when transformed to the CIE XYZ tristimulus space via a linear matrix, approximates a tetrahedron bounded by the three primary chromaticities and the white point. This tetrahedral structure encapsulates the subset of visible colors achievable by varying R, G, and B intensities within [0,1], excluding negative or super-unity values that lie outside the cube. Out-of-gamut handling, such as clipping, projects such colors onto the nearest gamut boundary to ensure device-reproducible outputs without introducing invalid tristimulus values.[63][64] Despite its mathematical elegance, the RGB space suffers from perceptual non-uniformity, where geometric distances do not align with human visual sensitivity, prompting conversions to uniform spaces like CIELAB for psychovisually accurate analysis. The Euclidean distance metric, quantifies linear separation but over- or underestimates perceived differences, as human color perception follows non-Euclidean geometries influenced by cone responses and adaptation. Gamut comparisons across RGB variants rely on volume computations via tetrahedral tessellation in CIE XYZ, summing signed volumes of sub-tetrahedra to assess coverage and overlap relative to the full visible spectrum.[65][66][67]Applications and Extensions

Web and Graphic Design

In web and graphic design, the RGB color model forms the foundation for specifying and manipulating colors through standardized syntax in Cascading Style Sheets (CSS). Thergb() function allows designers to define colors by providing red, green, and blue component values, typically as integers from 0 to 255 or percentages from 0% to 100%, such as rgb(255, 0, 0) for pure red.[68] This syntax originated in CSS Level 1, recommended by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) in 1996, enabling precise control over element colors like text and backgrounds.[68] Complementing this, hexadecimal notation serves as a compact shorthand, using formats like #FF0000 for the same red or the abbreviated #F00, where each pair of digits represents the intensity of one RGB channel.[69]

Web standards have entrenched sRGB as the default color space for RGB specifications to ensure consistent rendering across devices. Adopted by the W3C in alignment with the 1996 proposal from Hewlett-Packard and Microsoft, sRGB provides a standardized gamut for web content, minimizing discrepancies in color display.[70] In technologies like Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG), all colors are defined in sRGB, supporting RGB values in attributes for fills, strokes, and gradients to create resolution-independent visuals.[71] Similarly, the HTML Canvas API leverages RGB-based CSS colors for dynamic pixel manipulation, allowing JavaScript to draw and edit images by setting properties like fillStyle to RGB or hexadecimal values.[72]

Graphic design tools integrate RGB as a core output for color selection and workflow adaptation. Color pickers in applications like Adobe Photoshop display and export RGB values alongside other formats, enabling designers to sample hues from images or palettes and apply them directly to digital assets. When transitioning designs from print (often CMYK-based) to web formats, gamut mapping algorithms adjust out-of-gamut RGB colors to fit sRGB constraints, preserving visual intent by clipping or compressing vibrant tones that cannot be reproduced on screens.

Evolutions in CSS standards have expanded RGB capabilities beyond sRGB to accommodate modern displays. The CSS Color Module Level 4, advancing since the 2010s and reaching Candidate Recommendation status in 2022 (with ongoing drafts as of 2025), introduces the color() function for wider gamuts, such as Display P3, allowing specifications like color(display-p3 1 0 0) for enhanced reds on compatible hardware.[73]

For accessibility, Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) rely on RGB-derived luminances to compute contrast ratios, ensuring readable text by requiring at least 4.5:1 for normal text and 7:1 for large text. Relative luminance is calculated from sRGB component values using the formula , where R, G, and B are linear RGB values, then applied in the contrast ratio (with as the brighter luminance).[74]