Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hindustani classical music

View on Wikipedia

| Hindustani classical music | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concepts | ||||||

| Instruments | ||||||

|

||||||

| Genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Thaats | ||||||

| Indian classical music |

|---|

|

| Concepts |

Hindustani classical music (also known as North Indian classical music or Shastriya Sangeet) is the classical music of the Indian subcontinent's northern regions. It is played on instruments like the veena, sitar and sarod. It diverged in the 12th-century from Carnatic music, the classical tradition of southern India. While Carnatic music largely uses compositions written in Sanskrit, Telugu, Kannada, Tamil, Malayalam, Hindustani music largely uses compositions written in Sanskrit, Hindustani (Hindi-Urdu), Braj, Awadhi, Bhojpuri, Bengali, Rajasthani and Punjabi.[1]

Knowledge of Hindustani classical music is taught through a network of classical music schools, called gharana. Hindustani classical music is an integral part of the culture of North India and is performed across the country and internationally. Exponents of Hindustani classical music, including Ustad Bismillah Khan, Pandit Bhimsen Joshi and Ravi Shankar have been awarded the Bharat Ratna, the highest civilian award of India, for their contributions to the arts.[2]

History

[edit]Around the 12th-century, Hindustani classical music diverged from what eventually came to be identified as Carnatic classical music. The central notion in both systems is that of a melodic musical mode or raga, sung to a rhythmic cycle or tala. It is melodic music, with no concept of harmony. These principles were refined in the musical treatises Natya Shastra, by Bharata (2nd–3rd century CE), and Dattilam (probably 3rd–4th century CE).[3]

In medieval times, the melodic systems were fused with ideas from Persian music, particularly through the influence of Sufi composers like Amir Khusro, and later in the Mughal courts, noted composers such as Tansen flourished, along with religious groups like the Vaishnavites. Artists such as Dalptaram, Mirabai, Brahmanand Swami and Premanand Swami revitalized classical Hindustani music in the 16-18th century.

After the 16th century, the singing styles diversified into different gharanas patronized in different princely courts. Around 1900, Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande consolidated the musical structures of Hindustani classical music, called ragas, into a few thaats based on their notes. This is a very flawed system but is somewhat useful as a heuristic.

Distinguished musicians who are Hindu may be addressed as Pandit and those who are Muslim as Ustad. An aspect of Hindustani music going back to Sufi times is the tradition of religious neutrality: Muslim ustads may sing compositions in praise of Hindu deities, and Hindu pandits may sing similar Islamic compositions.

Vishnu Digambar Paluskar in 1901 founded the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya, a school to impart formal training in Hindustani classical music with some historical Indian Music. This was a school open to all and one of the first in India to run on public support and donations, rather than royal patronage. Many students from the School's early batches became respected musicians and teachers in North India. This brought respect to musicians, who were treated with disdain earlier. This also helped spread of Hindustani classical music to masses from royal courts.

Sanskritic tradition

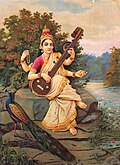

[edit]Ravana and Narada from Hindu tradition are accomplished musicians; Saraswati with her veena is the goddess of music. Gandharvas are presented as spirits who are musical masters, and the gandharva style looks to music primarily for pleasure, accompanied by the soma rasa. In the Vishnudharmottara Purana, the Naga king Ashvatara asks to know the swaras from Saraswati.[citation needed]

While the term raga is articulated in the Natya Shastra (where its meaning is more literal, meaning "color" or "mood"), it finds a clearer expression in what is called Jati in the Dattilam, a text composed shortly after or around the same time as Natya Shastra. The Dattilam is focused on Gandharva music and discusses scales (swara), defining a tonal framework called grama in terms of 22 micro-tonal intervals (shruti)[4]comprising one octave. It also discusses various arrangements of the notes (Murchhana), the permutations and combinations of note-sequences (tanas), and alankara or elaboration. Dattilam categorizes melodic structure into 18 groups called Jati, which are the fundamental melodic structures similar to the raga. The names of the Jatis reflect regional origins, for example Andhri and Oudichya[citation needed].

Music also finds mention in a number of texts from the Gupta period; Kalidasa mentions several kinds of veena (parivadini, vipanchi), as well as percussion instruments (mridang), the flute (vamshi) and conch (shankha). Music also finds mention in Buddhist and Jain texts from the earliest periods of the common era.[citation needed]

Narada's Sangita Makarandha treatise, from about 1100 CE, is the earliest text where rules similar to those of current Hindustani classical music can be found. Narada actually names and classifies the system in its earlier form before the Persian influences introduced changes in the system. Jayadeva's Gita Govinda from the 12th century was perhaps the earliest musical composition sung in the classical tradition called Ashtapadi music.[citation needed]

In the 13th century, Sharangadeva composed the Sangita Ratnakara, which has names such as the Turushka Todi ("Turkish Todi"), revealing an influx of ideas from Islamic culture. This text is the last to be mentioned by both the Carnatic and the Hindustani traditions and is often thought to date the divergence between the two.

During the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal era

[edit]

The advent of Islamic rule under the Delhi Sultanate and later the Mughal Empire over northern India caused considerable cultural interchange. Increasingly, musicians received patronage in the courts of the new rulers, who, in turn, started taking an increasing interest in local musical forms. While the initial generations may have been rooted in cultural traditions outside India, they gradually adopted many aspects from the Hindu culture from their kingdoms. This helped spur the fusion of Hindu and Muslim ideas to bring forth new forms of musical synthesis like qawwali and khyal.

The most influential musician of the Delhi Sultanate period was Amir Khusrau (1253–1325), a composer in Persian, Turkish and Arabic, as well as Braj Bhasha. He is credited with systematizing some aspects of Hindustani music and also introducing several ragas such as Yaman Kalyan, Zeelaf and Sarpada. He created six genres of music: khyal, tarana, Naqsh, Gul, Qaul and Qalbana. A number of instruments (such as the sitar) also developed in this time.

Amir Khusrau is sometimes credited with the origins of the khyal form, but the record of his compositions does not appear to support this. The compositions by the court musician Sadarang in the court of Muhammad Shah bear a closer affinity to the modern khyal. They suggest that while khyal already existed in some form, Sadarang may have been the father of modern khyal.

Much of the musical forms innovated by these pioneers merged with the Hindu tradition, composed in the popular language of the people (as opposed to Sanskrit) in the work of composers like Kabir or Nanak. This can be seen as part of a larger Bhakti tradition (strongly related to the Vaishnavite movement) which remained influential across several centuries; notable figures include Jayadeva (12th century), Vidyapati (fl. 1375 CE), Chandidas (14th–15th century), and Meerabai (1555–1603 CE).

As the Mughal Empire came into closer contact with Hindus, especially under Jalal ud-Din Akbar, music and dance also flourished. In particular, the musician Tansen introduced a number of innovations, including ragas and particular compositions. Legend has it that upon his rendition of a nighttime raga in the morning, the entire city fell under a hush and clouds gathered in the sky so that he could light fires by singing the raga "Deepak".

At the royal house of Gwalior, Raja Mansingh Tomar (1486–1516 CE) also participated in the shift from Sanskrit to the local idiom (Hindi) as the language for classical songs. He himself penned several volumes of compositions on religious and secular themes and was also responsible for the major compilation, the Mankutuhal ("Book of Curiosity"), which outlined the major forms of music prevalent at the time. In particular, the musical form known as dhrupad saw considerable development in his court and remained a strong point of the Gwalior gharana for many centuries.

After the dissolution of the Mughal empire, the patronage of music continued in smaller princely kingdoms like Awadh, Patiala, and Banaras, giving rise to the diversity of styles that is today known as gharanas. Many musician families obtained large grants of land which made them self-sufficient, at least for a few generations (e.g. the Sham Chaurasia gharana). Meanwhile, the Bhakti and Sufi traditions continued to develop and interact with the different gharanas and groups.

Modern era

[edit]Until the late 19th century, Hindustani classical music was imparted on a one-on-one basis through the guru-shishya ("mentor-protégé") tradition. This system had many benefits but also several drawbacks. In many cases, the shishya had to spend most of his time, serving his guru with the hope that the guru might teach him a "cheez" (piece or nuance) or two. In addition, the system forced the music to be limited to a small subsection of the Indian community. To a large extent, it was limited to the palaces and dance halls. It was shunned by the intellectuals, avoided by the educated middle class, and in general, looked down upon as a frivolous practice.[5]

First, as the power of the maharajahs and nawabs declined in the early 20th century, so did their patronage. With the expulsion of Wajid Ali Shah to Calcutta after 1857, the Lucknavi musical tradition came to influence the music of the renaissance in Bengal, giving rise to the tradition of Ragpradhan gan around the turn of the century. Raja Chakradhar Singh of Raigarh was the last of the modern-era Maharajas to patronize Hindustani classical musicians, singers and dancers.[6][7]

Also, at the turn of the century, Vishnu Digambar Paluskar and Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande spread Hindustani classical music to the masses in general by organizing music conferences, starting schools, teaching music in classrooms, devising a standardized grading and testing system, and standardizing the notation system.[8]

Vishnu Digambar Paluskar emerged as a talented musician and organizer despite being blind from age of 12. His books on music, as well as the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya music school that he opened in Lahore in 1901, helped foster a movement away from the closed gharana system.

Paluskar's contemporary (and occasional rival) Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande recognized the many rifts that had appeared in the structure of Indian classical music. He undertook extensive research visits to a large number of gharanas, Hindustani as well as Carnatic, collecting and comparing compositions. Between 1909 and 1932, he produced the monumental four-volume work Hindustani Sangeeta Paddhati,[9] which suggested a transcription of Indian music, and described the many traditions in this notation. Finally, it suggested a possible categorization of ragas based on their notes into a number of thaats (modes), subsequent to the Melakarta system that reorganized Carnatic tradition in the 17th century. The ragas that exist today were categorized according to this scheme, although there are some inconsistencies and ambiguities in Bhatkande's system.

In modern times, the government-run All India Radio, Bangladesh Betar and Radio Pakistan helped bring the artists to public attention, countering the loss of the patronage system. The first star was Gauhar Jan, whose career was born out of Fred Gaisberg's first recordings of Indian music in 1902. With the advance of films and other public media, musicians started to make their living through public performances. A number of Gurukuls, such as that of Alauddin Khan at Maihar, flourished. In more modern times, corporate support has also been forthcoming, as at the ITC Sangeet Research Academy. Meanwhile, Hindustani classical music has become popular across the world through the influence of artists such as Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar Khan and Vikash Maharaj.

Characteristics

[edit]Indian classical music has seven basic notes with five interspersed half-notes, resulting in a 12-note scale. Unlike the 12-note scale in Western music, the base frequency of the scale is not fixed, and intertonal gaps (temperament) may also vary. The performance is set to a melodic pattern called a raga characterized in part by specific ascent (aroha) and descent (avaroha) sequences, "king" (vadi) and "queen" (samavadi) notes and characteristic phrases (pakad).[citation needed]

Ragas may originate from any source, including religious hymns, folk tunes, and music from outside the Indian subcontinent[citation needed]. For example, raga Khamaj and its variants have been classicized from folk music, while ragas such as Hijaz (also called Basant Mukhari) originated in Persian maqams.

Principles of Hindustani music

[edit]The Gandharva Veda is a Sanskrit scripture describing the theory of music and its applications in not just musical form and systems but also in physics, medicine and magic.[10] It is said that there are two types of sound: āhata (struck/audible) and anāhata (unstruck/inaudible).[10] The inaudible sound is said to be the principle of all manifestation, the basis of all existence.[10]

There are three main 'Saptak' which resemble to the 'Octaves' in Western Music except they characterize total seven natural (shuddha) notes or 'swaras' instead of eight. These are -- low (mandra), medium (madhya) and high (tāra).[10] Each octave resonates with a certain part of the body, low octave in the heart, medium octave in the throat and high octave in the head. Each octave in total contains 12 different notes, containing 7 natural or 'shuddha' notes (S R G M P D N), 4 flat or 'komal' notes (R G D N), and 1 sharp or 'teevra' note (M).[10]

The rhythmic organization is based on rhythmic patterns called tala. The melodic foundations are called ragas. One possible classification of ragas is into "melodic modes" or "parent scales," known as thaats, under which most ragas can be classified based on the notes they use.

Thaats may consist of up to seven scale degrees, or swara. Hindustani musicians name these pitches using a system called Sargam, the equivalent of the Western movable do solfege:

- Sa (ṣaḍja षड्ज) = Do

- Re (Rishabh ऋषभ) = Re

- Ga (Gāndhāra गान्धार) = Mi

- Ma (Madhyam मध्यम) = Fa

- Pa (Pancham पञ्चम) = So

- Dha (Dhaivat धैवत) = La

- Ni (Nishād निषाद) = Ti

- Sa (ṣaḍja षड्ज) = Do

Both systems repeat at the octave. The difference between sargam and solfege is that re, ga, ma, dha, and ni can refer to either "Natural" (shuddha) or altered "Flat" (komal) or "Sharp" (teevra) versions of their respective scale degrees. As with movable do solfege, the notes are heard relative to an arbitrary tonic that varies from performance to performance, rather than to fixed frequencies, as on a xylophone. The fine intonational differences between different instances of the same swara are called srutis. The three primary registers of Indian classical music are mandra (lower), madhya (middle) and taar (upper). Since the octave location is not fixed, it is also possible to use provenances in mid-register (such as mandra-madhya or madhya-taar) for certain ragas. A typical rendition of Hindustani raga involves two stages:

- Alap: a rhythmically free improvisation on the rules for the raga in order to give life to the raga and flesh out its characteristics. The alap is followed by a long slow-tempo improvisation in vocal music, or by the jod and jhala in instrumental music.

Tans are of several types like Shuddha, Koot, Mishra, Vakra, Sapaat, Saral, Chhoot, Halaq, Jabda, Murki.

- Bandish or Gat: a fixed, melodic composition set in a specific raga, performed with rhythmic accompaniment by a tabla or pakhavaj. There are different ways of systematizing the parts of a composition. For example:

- Sthaayi: The initial, rondo phrase or line of a fixed, melodic composition

- Antara: The first body phrase or line of a fixed, melodic composition. Explores the upper octave of a Raag. In Khayal compositions, this is sometimes where the poet's name can be found.

- Sanchaari: The third body phrase or line of a fixed, melodic composition, seen more typically in dhrupad bandishes. Usually explores the lower section of a given Raag.

- Aabhog: The fourth and concluding body phrase or line of a fixed, melodic composition, seen more typically in Dhrupad bandishes. Continues to explore the upper octave of a Raag just like an Antara, but with more expansive phrases. This is often where the poet's name resides as a signature for Dhrupad compositions.

- There are three variations of bandish, regarding tempo:

- Vilambit bandish: A slow and steady melodic composition, usually in largo to adagio speeds

- Madhyalaya bandish: A medium tempo melodic composition, usually set in andante to allegretto speeds

- Drut bandish: A fast tempo melodic composition, usually set to allegretto speed or faster

Hindustani classical music is primarily vocal-centric, insofar as the musical forms were designed primarily for a vocal performance, and many instruments were designed and evaluated as to how well they emulate the human voice.

Types of compositions

[edit]The major vocal forms or styles associated with Hindustani classical music are dhrupad, khyal, and tarana. Light classical forms include dhamar, trivat, chaiti, kajari, tappa, tap-khyal, thumri, dadra, ghazal and bhajan; these do not adhere to the rigorous rules of classical music.[clarification needed]

Dhrupad

[edit]Dhrupad is an old style of singing, traditionally performed by male singers. It is performed with a tambura and a pakhawaj as instrumental accompaniments. The lyrics, some of which were written in Sanskrit centuries ago, are presently often sung in brajbhasha, a medieval form of North and East Indian languages that were spoken in Eastern India. The rudra veena, an ancient string instrument, is used in instrumental music in dhrupad.

Dhrupad music is primarily devotional in theme and content. It contains recitals in praise of particular deities. Dhrupad compositions begin with a relatively long and acyclic alap, where the syllables of the following mantra is recited:

"Om Anant tam Taran Tarini Twam Hari Om Narayan, Anant Hari Om Narayan".

The alap gradually unfolds into more rhythmic jod and jhala sections. These sections are followed by a rendition of bandish, with the pakhawaj as an accompaniment. The great Indian musician Tansen sang in the dhrupad style. A lighter form of dhrupad called dhamar, is sung primarily during the spring festival of Holi.

Dhrupad was the main form of northern Indian classical music until two centuries ago when it gave way to the somewhat less austere khyal, a more free-form style of singing. Since losing its main patrons among the royalty in Indian princely states, dhrupad risked becoming extinct in the first half of the twentieth century. However, the efforts by a few proponents, especially from the Dagar family, have led to its revival.

Some of the best known vocalists who sing in the Dhrupad style are the members of the Dagar lineage, including the senior Dagar brothers, Nasir Moinuddin and Nasir Aminuddin Dagar; the junior Dagar brothers, Nasir Zahiruddin and Nasir Faiyazuddin Dagar; and Wasifuddin, Fariduddin, and Sayeeduddin Dagar. Other leading exponents include the Gundecha Brothers and Uday Bhawalkar, who have received training from some of the Dagars. Leading vocalists outside the Dagar lineage include the Mallik family of Darbhanga tradition of musicians; some of the leading exponents of this tradition were Ram Chatur Mallick, Siyaram Tiwari, and Vidur Mallick. At present Prem Kumar Mallick, Prashant and Nishant Mallick are the Dhrupad vocalists of this tradition. A Very ancient 500 years old Dhrupad Gharana from Bihar is Dumraon Gharana, Pt. Tilak Chand Dubey, Pt. Ghanarang Baba was founder of this prestigious Gharana. Dumraon Gharana Dist-Buxar is an ancient tradition of Dhrupad music nearly 500 years old. This Gharana flourished under the patronage of the king of Dumraon Raj. The dhrupad style (vanis) of the gharana is Gauhar, Khandar and Nauharvani. The living legends of this gharana is Pt. Ramjee Mishra.

A section of dhrupad singers of Delhi Gharana from Mughal emperor Shah Jahan's court migrated to Bettiah under the patronage of the Bettiah Raj, giving rise to the Bettiah Gharana.[11]

Khyal

[edit]Khyal is the modern Hindustani form of vocal music. Khyal, literally meaning "thought" or "imagination" in Hindustani and derived from the Persian/Arabic term, is a two- to eight-line lyric set to a melody. Khyal contains a greater variety of embellishments and ornamentations compared to dhrupad. Khyal's features such as sargam and taan as well as movements to incorporate dhrupad-style alap have led to it becoming popular.

The importance of the khyal's content is for the singer to depict, through music in the set raga, the emotional significance of the khyal. The singer improvises and finds inspiration within the raga to depict the khyal.

The origin of Khyal is controversial, although it is accepted that this style was based on dhrupad and influenced by other musical traditions. Many argue that Amir Khusrau created the style in the late 14th-century. This form was popularized by Mughal emperor Mohammad Shah through his court musicians; some well-known composers of this period were Sadarang, Adarang and Manrang.

Tarana

[edit]Another vocal form, taranas are medium- to fast-paced songs that are used to convey a mood of elation and are usually performed towards the end of a concert. They consist of a few lines of bols either from the rhythmic language of Tabla, Pakhawaj or Kathak dance set to a tune. The singer uses these few lines as a basis for fast improvisation. The tillana of Carnatic music is based on the tarana, although the former is primarily associated with dance.

Tappa

[edit]Tappa is a form of Indian semi-classical vocal music whose specialty is its rolling pace based on fast, subtle, knotty construction. It originated from the folk songs of the camel riders of Punjab and was developed as a form of classical music by Mian Ghulam Nabi Shori or Shori Mian, a court singer for Asaf-Ud-Dowlah, the Nawab of Awadh. "Nidhubabur Tappa," or tappas sung by Nidhu Babu were very popular in 18th and 19th-century Bengal.

Thumri

[edit]Thumri is a semi-classical vocal form said to have begun in Uttar Pradesh with the court of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, (r. 1847–1856). The lyrics are primarily in older, more rural Hindi dialects such as Brij Bhasha, Awadhi, and Bhojpuri. The themes covered are usually romantic in nature, hence giving more importance to lyrics rather than Raag, and bringing out the storytelling qualities of music. The need to express these strong emotional aesthetics makes Thumri and Kathak a perfect match, which, before Thumri became a solo form, were performed together.

Some recent performers of this genre are Abdul Karim Khan, the brothers Barkat Ali Khan and Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Begum Akhtar, Nirmala Devi, Girija Devi, Prabha Atre, Siddheshwari Devi, Shobha Gurtu and Chhannulal Mishra.

Ghazal

[edit]In the Indian sub-continent during Mughal rule, the Persian Ghazal became the most common poetic form in the Urdu language and was popularized by classical poets like Mir Taqi Mir, Ghalib, Daagh, Zauq and Sauda amongst the North Indian literary elite. The Ghazal genre is characterized by its romance, and its discourses on the various shades of love. Vocal music set to this mode of poetry is popular with multiple variations across Central Asia, the Middle East, as well as other countries and regions of the world.

Instruments

[edit]Although Hindustani music clearly is focused on vocal performance, instrumental forms have existed since ancient times. In fact, in recent decades, especially outside South Asia, instrumental Hindustani music is more popular than vocal music, partly due to a somewhat different style and faster tempo, and partly because of a language barrier for the lyrics in vocal music.

Many musical instruments are associated with Hindustani classical music. The veena, a string instrument, was traditionally regarded as the most important, but few play it today and it has largely been superseded by its cousins the sitar and the sarod, both of which owe their origin to Persian influences. The tambura is also regarded as one of the most important instruments, due to its functioning as a fundamental layer that the rest of the instruments adhere to throughout a performance. Among bowed instruments, the sarangi and violin are popular. The bansuri, shehnai and harmonium are important wind instruments. In the percussion ensemble, the tabla and the pakhavaj are the most popular. Rarely used plucked or struck string instruments include the surbahar, sursringar, santoor, and various versions of the slide guitar. Various other instruments have also been used in varying degrees.

Festivals

[edit]One of the earliest modern music festivals focusing on Hindustani classical music was the Harballabh Sangeet Sammelan, founded in 1875 in Jallandhar. Others include Sankatmochan Sangeet Samarth in Varanasi, Dover Lane Music Conference which notably debuted in 1952 in Kolkata, Sawai Gandharva Bhimsen Festival in 1953 in Pune, ITC SRA Sangeet Sammelan since the early 1970s, the Society for the Promotion of Indian Classical Music And Culture Amongst Youth or SPIC MACAY since 1977, Pandit Nanhku Maharaj since 1995.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ho, Meilu (1 May 2013). "Connecting Histories: Liturgical Songs as Classical Compositions in Hindustānī Music". Ethnomusicology. 57 (2): 207–235. doi:10.5406/ethnomusicology.57.2.0207. ISSN 0014-1836.

- ^ "Indian artists who became the Bharat Ratna". 26 May 2020.

- ^ A Study of Dattilam: A Treatise on the Sacred Music of Ancient India, 1978, p 283, Mukunda Lāṭha, Dattila

- ^ The term shruti literally means "that which is heard". One of its senses refers to the "received" texts of the vedas; here it means notes of a scale.

- ^ "Marathi News, Latest Marathi News, Marathi News Paper, Marathi News Paper in Mumbai". Loksatta. Archived from the original on 21 October 2009.

- ^ The Journal of the Music Academy, Madras - Volume 62 -1991 - Page 157

- ^ India's Kathak Dance Past, Present, Future: - Page 28

- ^ "Marathi News, Latest Marathi News, Marathi News Paper, Marathi News Paper in Mumbai". Loksatta. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012.

- ^

Hindustani Sangeeta Paddhati (4 volumes, Marathi) (1909–1932). Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande. Sangeet Karyalaya (1990 reprint). ISBN 81-85057-35-4.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Originally in Marathi, this book has been widely translated. - ^ a b c d e Alain, Daniélou (2014). The Rāgas of Northern Indian music. Daniélou, Alain. (2014 ed.). New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal. ISBN 978-8121502252. OCLC 39028809.

- ^ "Many Bihari artists ignored by SPIC MACAY". The Times of India. 13 October 2001. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

Further reading

[edit]- Indian Classical Music and Western Pop

- Moutal, Patrick (1991). A Comparative Study of Selected Hindustāni Rāga-s. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt Ltd. ISBN 81-215-0526-7.

- Moutal, Patrick (1991). Hindustāni Rāga-s Index. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt Ltd.

- Bagchee, Sandeep (1998). Nad. BPI Publishers. ISBN 81-86982-07-8.

- Bagchee, Sandeep (2006). Shruti : A Listener's Guide to Hindustani Music. Rupa. ISBN 81-291-0903-4.

- Orsini, F. and Butler Schofield K. (2015). Tellings and Texts: Music, Literature and Performance in North India. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers. ISBN 9781783741021.

- Srivastava, Satish Chandra and Kumar, Rohit (2021). Introduction of Raags Part-1. Sangeet Shree Prakashan. ISBN 978-8193168929.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Srivastava, Satish Chandra and Kumar, Rohit (2021). Introduction of Raags Part-2. Sangeet Shree Prakashan. ISBN 978-8193168974.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Hindustani classical music

View on GrokipediaOrigins and History

Ancient Roots in Sanskritic Tradition

The origins of Hindustani classical music trace back to the ancient Sanskritic traditions of Vedic India, where music was intrinsically linked to ritual and spiritual practices. The Samaveda, one of the four Vedas composed around 1500–1200 BCE, represents the earliest documented musical tradition in India, consisting of melodies (saman) set to selected hymns from the Rigveda for use in sacrificial rituals. These chants emphasized intonation and melodic recitation, laying the groundwork for structured vocal music by prioritizing the sonic qualities of Sanskrit syllables to invoke divine presence.[7] A pivotal development occurred with the Natya Shastra, an encyclopedic treatise attributed to Bharata Muni and dated between approximately 200 BCE and 200 CE, which systematized music as part of a broader performing arts framework encompassing drama, dance, and song. In its chapters on music (Chapters 28–33), the text delineates fundamental concepts such as swaras (notes), shrutis (microtonal intervals), and rhythmic structures (tala), establishing music's role in evoking aesthetic emotions (rasa) during performances. This work drew directly from Vedic chanting practices, adapting Samaveda principles into a theoretical foundation for instrumental and vocal composition, thereby influencing subsequent Indian musical traditions.[8] By the medieval period, ancient musical theory evolved through texts like the Brihaddeshi, composed by Matanga Muni around the 9th century CE, which introduced the concepts of grama (parent scales, such as Shadja and Madhyama) and murchanas (derived melodic sequences ascending and descending within those scales). This treatise marked a shift toward deshi (regional or folk-influenced) music alongside margi (Vedic or classical) forms, classifying early ragas and emphasizing the emotional and structural diversity of melodies while building on Natya Shastra's foundations. Temples served as key centers for preserving these ideas through oral transmission by priestly lineages and devadasis (temple dancers), ensuring the continuity of melodic patterns and rhythmic cycles amid evolving regional practices.[9] Key figures like Narada, traditionally regarded as a divine sage, contributed significantly through the Sangita Makarandha, a 11th-century text that further refined music theory by detailing raga classifications, the 22 shrutis with their names, and guidelines for composition and performance. Narada's work synthesized earlier Vedic and post-Vedic ideas, providing practical instructions for vocal and instrumental music that emphasized improvisation within defined melodic frameworks, thus bridging ancient ritual chants to more elaborate artistic expressions. Oral guru-shishya (teacher-disciple) traditions in temple and scholarly settings perpetuated these theoretical advancements, safeguarding them from textual loss until later compilations.Medieval Developments under Islamic Rule

The arrival of Islamic rule in northern India, beginning with the Delhi Sultanate in the 12th century, marked a pivotal phase in the evolution of Hindustani music through the synthesis of indigenous Sanskritic traditions with Persian and Central Asian elements. This period saw the introduction of Persian musical concepts and instruments via Sufi saints, who facilitated cultural exchange in devotional and courtly settings. Under rulers like Alauddin Khilji (r. 1296–1316), patronage extended to musicians such as Amir Khusrau, a Sufi poet and composer who blended Persian modes (maqams) with Indian ragas, creating hybrid forms like qawwali that emphasized ecstatic spiritual expression.[10][11] Khusrau's innovations, including rhythmic patterns inspired by Persian poetry, laid the groundwork for a fused aesthetic that integrated Hindu devotional bhakti elements with Islamic sama (spiritual listening) practices.[12] A key textual bridge between ancient and medieval practices was provided by Sarngadeva's Sangeet Ratnakara (c. 1230–1250), which systematized earlier Natyashastra principles while incorporating evolving regional styles under Sultanate influence. This comprehensive treatise on music, dance, and drama detailed swara (notes), raga structures, and tala (rhythms), serving as a foundational reference that influenced both courtly and temple music during the transition to Islamic patronage.[13][14] By preserving and adapting ancient Sanskritic foundations, it enabled the absorption of foreign elements without disrupting core theoretical frameworks.[13] The 15th century witnessed the emergence of dhrupad as a prominent courtly vocal form, attributed to the patronage of Raja Mansingh Tomar (r. 1486–1516) of Gwalior, who refined earlier prabandha compositions into a structured style emphasizing textual clarity and rhythmic precision. Tomar's court, a hub of musical innovation, transformed dhrupad from devotional temple songs into a sophisticated genre suitable for royal assemblies, incorporating Braj Bhasha lyrics over Sanskrit to broaden accessibility.[15][16] This development reflected early fusions of Hindu and Muslim elements, as Gwalior's milieu drew musicians from diverse backgrounds, fostering a shared repertoire.[12] Under the Mughal Empire, particularly during Akbar's reign (r. 1556–1605), these syntheses reached new heights through the legendary musician Tansen, who refined dhrupad into a pinnacle of expressive depth and technical mastery. As one of Akbar's Navaratnas (nine jewels), Tansen elevated the form by emphasizing alap (unmetered improvisation) and bol banao (syllabic elaboration), drawing on Persian rhythmic influences while rooted in Indian raga elaboration.[17] His compositions and teachings standardized dhrupad for imperial courts, promoting a cosmopolitan style that harmonized Hindu and Islamic sensibilities.[18] Instruments like the been, or rudra veena—a fretted string instrument with gourd resonators—gained prominence in this era, symbolizing the era's cultural fusion as it adapted ancient veena designs for dhrupad accompaniment in Mughal ensembles. Played by virtuosos such as Tansen, the been's resonant tones facilitated intricate glides (meends) and drone harmonies, blending indigenous construction with courtly performance aesthetics influenced by Persian lutes.[19] This integration exemplified how Islamic rule catalyzed the maturation of Hindustani music into a distinct northern tradition by the 16th century.[12]Modern Evolution and Revival

The advent of British colonial rule in the 19th century profoundly disrupted the patronage system that had sustained Hindustani classical music for centuries. As the British East India Company and later the Crown annexed princely states, royal courts—traditional benefactors of musicians—faced financial strain and cultural marginalization, leading to a sharp decline in aristocratic support for the art form. British administrators often favored Western musical traditions, viewing Indian classical music as inferior or overly complex, which further eroded its institutional backing.[20] This crisis prompted musicians to adapt by relocating to burgeoning urban centers such as Calcutta, Bombay, and Lucknow, where they performed in emerging public concert formats organized by music societies and conferences. These urban mehfils and sabhas marked a transition from exclusive courtly settings to more democratic, ticketed performances, broadening access but also commercializing the tradition amid economic pressures. Pioneers like Vishnu Digambar Paluskar, who promoted public performances and music education, and Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande, who initiated all-India music conferences in the early 1900s, worked to standardize and revive the practice, laying groundwork for modern dissemination.[21] A key figure in this revival was Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande (1860–1936), whose scholarly efforts aimed to preserve and systematize Hindustani music against colonial erosion. Through extensive fieldwork documenting oral traditions from gharanas across India, Bhatkhande classified ragas into 10 principal thaats—Bilaval, Kalyan, Khamaj, Bhairav, Poorvi, Marwa, Kafi, Asavari, Bhairavi, and Todi—to create a pedagogical framework accessible for notation and teaching, diverging from the fluid, guru-shishya oral methods. He founded institutions like the Marris College of Hindustani Music in Lucknow (1926), now the Bhatkhande Music Institute Deemed University, to train musicians professionally and promote research, influencing the institutionalization of the art form nationwide.[22][23][24] Post-independence in 1947, state initiatives revitalized Hindustani music by integrating it into national cultural policy. All India Radio (AIR), nationalized and expanded after 1947, became instrumental in broadcasting classical performances daily through programs like Sangeet Sammelan, reaching rural and urban listeners alike and sustaining artists in the absence of royal patrons. The Sangeet Natak Akademi, established in 1953 as India's apex body for performing arts, further institutionalized support by awarding fellowships and honors to Hindustani exponents, organizing national festivals, and funding archives to document and promote the tradition.[25][26] Twentieth-century innovations propelled Hindustani music toward global horizons, particularly through fusions with Western idioms led by Ravi Shankar (1920–2012). Shankar's collaborations, such as his 1960s recordings with violinist Yehudi Menuhin and influences on The Beatles—exemplified by George Harrison's adoption of the sitar in "Norwegian Wood"—blended ragas with Western harmony and rhythm, introducing Hindustani concepts to international audiences via concerts at venues like the Monterey Pop Festival (1967). These efforts not only disseminated the music worldwide but also inspired cross-genre experiments, embedding sitar and tabla in global pop and classical repertoires while affirming Hindustani music's adaptability in modern contexts.[27]Core Theoretical Principles

Swaras, Shrutis, and Scales

Hindustani classical music employs seven primary notes, known as swaras, which form the foundational pitches of its melodic system: Shadja (Sa), Rishabh (Re), Gandhar (Ga), Madhyam (Ma), Pancham (Pa), Dhaivat (Dha), and Nishad (Ni). These swaras are organized within an octave, or saptak, spanning from the lower Sa to the upper Sa, with Sa and Pa designated as fixed (achal) tones that do not vary. The remaining swaras—Re, Ga, Dha, and Ni—can appear in natural (shuddha) form, while Re, Ga, Dha, and Ni may also be flattened by a semitone to produce the komal variant, and Ma can be sharpened by a semitone to become tivra; these alterations allow for the chromatic flexibility essential to raga construction.[28][29] Underlying this system is the ancient concept of shrutis, which represent 22 microtonal intervals that divide the octave into finer gradations than the Western 12 semitones. As formalized in Bharata Muni's Natya Shastra (circa 200 BCE–200 CE), shrutis provide the subtle pitch variations—known as andolan or gamak—that enable expressive nuances in performance, with the seven swaras emerging as groupings of these microtones. The octave is thus partitioned such that the total span equals 22 shrutis, allowing for precise intonation adjustments that distinguish Hindustani music's fluid tonality from equal temperament systems.[30] This microtonal framework, while theoretical, informs practical tuning on instruments like the sitar or sarod, where performers approximate shrutis through string bends and finger placements.[31] For systematic classification of melodic structures, the thaat system organizes scales into 10 parent frameworks, each a heptatonic scale (using seven swaras) proposed by musicologist Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande in his early 20th-century treatise Hindustani Sangeet Paddhati. These thaats serve as melodic templates from which ragas are derived by selective omission or alteration of notes, facilitating pedagogical analysis without prescribing rigid performance rules. The 10 thaats are:| Thaat | Key Swara Alterations (from Bilaval base) |

|---|---|

| Bilaval | All shuddha (natural major scale equivalent) |

| Kalyan | Tivra Ma |

| Khamaj | Komal Ni |

| Kafi | Komal Ga, Ni |

| Asavari | Komal Ga, Dha, Ni; shuddha Re |

| Bhairav | Komal Re, Dha |

| Todi | Komal Re, Ga, Dha; tivra Ma |

| Purvi | Tivra Ma; komal Re, Dha |

| Marwa | Tivra Ma; komal Re |

| Bhairavi | Komal Re, Ga, Dha, Ni |