Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

International Labour Organization

View on Wikipedia

The International Labour Organization (ILO) is a United Nations agency whose mandate is to advance social and economic justice by setting international labour standards.[1][3] Founded in October 1919 under the League of Nations, it is one of the first and oldest specialized agencies of the UN. The ILO has 187 member states: 186 out of 193 UN member states plus the Cook Islands. It is headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, with around 40 field offices around the world, and employs some 3,381 staff across 107 nations, of whom 1,698 work in technical cooperation programmes and projects.[4]

Key Information

The ILO's standards are aimed at ensuring accessible, productive, and sustainable work worldwide in conditions of freedom, equity, security and dignity.[5][6] They are set forth in 189 conventions and treaties, of which eight are classified as fundamental according to the 1998 Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work; together they protect freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining, the elimination of forced or compulsory labour, the abolition of child labour, and the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation. The ILO is a major contributor to international labour law.

Within the UN system the organization has a unique tripartite structure: all standards, policies, and programmes require discussion and approval from the representatives of governments, employers, and workers. This framework is maintained in the ILO's three main bodies: The International Labour Conference, which meets annually to formulate international labour standards; the Governing Body, which serves as the executive council and decides the agency's policy and budget; and the International Labour Office, the permanent secretariat that administers the organization and implements activities. The secretariat is led by the Director-General, Gilbert Houngbo of Togo, who was elected by the Governing Body in 2022.

In 2019, the organization convened the Global Commission on the Future of Work, whose report made ten recommendations for governments to meet the challenges of the 21st century labour environment; these include a universal labour guarantee, social protection from birth to old age and an entitlement to lifelong learning.[7][8] With its focus on international development, it is a member of the United Nations Development Group, a coalition of UN organizations aimed at helping meet the Sustainable Development Goals.

Two milestones in the history of the ILO were the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, establishing the International Labour Organization, Article 427. And secondly, the Declaration of Philadelphia in 1944, reestablishing the ILO under the United Nations and reaffirming the first principle that "labour is not a commodity".

Structure

[edit]

The ILO is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN).[9] As with other UN specialized agencies (or programmes) working on international development, the ILO is also a member of the United Nations Development Group.[10]

Unlike other United Nations specialized agencies, the International Labour Organization (ILO) has a tripartite governing structure that brings together governments, employers, and workers of 187 member States, to set labour standards, develop policies and devise programmes promoting decent work for all women and men. The structure is intended to ensure the views of all three groups are reflected in ILO labour standards, policies, and programmes, though governments have twice as many representatives as the other two groups.

Governing body

[edit]The Governing Body is the executive body of the International Labour Organization. It meets three times a year, in March, June and November. It takes decisions on ILO policy, decides the agenda of the International Labour Conference, adopts the draft Programme and Budget of the Organization for submission to the Conference, elects the Director-General, requests information from the member states concerning labour matters, appoints commissions of inquiry and supervises the work of the International Labour Office.

The Governing Body is composed of 56 titular members (28 governments, 14 employers and 14 workers) and 66 deputy members (28 governments, 19 employers and 19 workers).

Ten of the titular government seats are permanently held by States of chief industrial importance: Brazil, China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom and the United States.[11] The other Government members are elected by the Conference every three years (the last elections were held in June 2021).[12] The Employer and Worker members are elected in their individual capacity.[13][14]

Director-General

[edit]On 25 March 2022 Gilbert Fossoun Houngbo was elected Director-General of ILO.[15] On 1 October 2022 he succeeded Guy Ryder, who was elected by the ILO Governing Body in October 2012, and re-elected for a second five-year-term in November 2016.[16] He is the organization's first African Director-General. In 2024, a group of African countries that play a crucial role visited the International Labour Office, such as Morocco, where they held talks with the Minister of Economic Integration, Small Business, Employment, and Skills Development, Younes Sekouri.[17] The list of the Directors-General of ILO since its establishment in 1919 is as follows:[18]

| Name | Country | Term |

|---|---|---|

| Albert Thomas | 1919–1932 | |

| Harold Butler | 1932–1938 | |

| John G. Winant | 1939–1941 | |

| Edward J. Phelan | 1941–1948 | |

| David A. Morse | 1948–1970 | |

| Clarence Wilfred Jenks | 1970–1973 | |

| Francis Blanchard | 1974–1989 | |

| Michel Hansenne | 1989–1999 | |

| Juan Somavía | 1999–2012 | |

| Guy Ryder | 2012–2022 | |

| Gilbert Houngbo | 2022–present |

Membership

[edit]

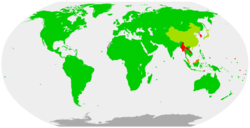

The ILO has 187 state members. 186 of the 193 member states of the United Nations plus the Cook Islands are members of the ILO.[19] The UN member states which are not members of the ILO are Andorra, Bhutan, Liechtenstein, Micronesia, Monaco, Nauru, and North Korea.[20]

The ILO constitution permits any member of the UN to become a member of the ILO. To gain membership, a nation must inform the director-general that it accepts all the obligations of the ILO constitution.[21] Other, non-UN states can be admitted by a two-thirds vote of all delegates, including a two-thirds vote of government delegates, at any ILO General Conference. The Cook Islands, a non-UN state, joined in June 2015.[22][23]

Countries that had been members of the ILO under the League of Nations remained members when the organization's new constitution came into effect in 1946.[23]

Objectives

[edit]The Declaration of Philadelphia (10 May 1944) restated the traditional objectives of the International Labour Organization and then branched out in two new directions: the centrality of human rights to social policy, and the need for international economic planning.[24]: 481–2 With the end of the world war in sight, it sought to adapt the guiding principles of the ILO "to the new realities and to the new aspirations aroused by the hopes for a better world."[25]: 287 It was adopted at the 26th Conference of the ILO in Philadelphia, United States of America.[24]: 481

In 1946, when the ILO's constitution was being revised by the General Conference convened in Montreal, the Declaration of Philadelphia was annexed to the constitution and forms an integral part of it by Article 1.[25]: 287 Most of the demands of the declaration were a result of a partnership of American and Western European labor unions and the ILO secretariat.[24]: 481

"Labour is not a commodity" is the principle expressed in the preamble to the International Labour Organization's founding documents. It expresses the view that people should not be treated like inanimate commodities, capital, another mere factor of production, or resources. Instead, people who work for a living should be treated as human beings and accorded dignity and respect. Paul O'Higgins attributes the phrase to John Kells Ingram, who used it in 1880 during a meeting in Dublin of the British Trades Union Congress.[26]

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]It is the first organization for the UN.While the ILO was established as an agency of the League of Nations following World War I, its founders had made great strides in social thought and action before 1919. The core members all knew one another from earlier private professional and ideological networks, in which they exchanged knowledge, experiences, and ideas on social policy. Pre-war "epistemic communities", such as the International Association for Labour Legislation (IALL), founded in 1900, and political networks, such as the socialist Second International, were a decisive factor in the institutionalization of international labour politics.[27]

In the post-World War I euphoria, the idea of a "makeable society" was an important catalyst behind the social engineering of the ILO architects. As a new discipline, international labour law became a useful instrument for putting social reforms into practice. The utopian ideals of the founding members—social justice and the right to decent work—were changed by diplomatic and political compromises made at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, showing the ILO's balance between idealism and pragmatism.[27]

Over the course of the First World War, the international labour movement proposed a comprehensive programme of protection for the working classes, conceived as compensation for labour's support during the war.[clarification needed] Post-war reconstruction and the protection of labour unions occupied the attention of many nations during and immediately after World War I. In Great Britain, the Whitley Commission, a subcommittee of the Reconstruction Commission, recommended in its July 1918 Final Report that "industrial councils" be established throughout the world.[28] The British Labour Party had issued its own reconstruction programme in the document titled Labour and the New Social Order.[29] In February 1918, the third Inter-Allied Labour and Socialist Conference (representing delegates from Great Britain, France, Belgium and Italy) issued its report, advocating an international labour rights body, an end to secret diplomacy, and other goals.[30] And in December 1918, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) issued its own distinctively apolitical report, which called for the achievement of numerous incremental improvements via the collective bargaining process.[31]

IFTU Bern Conference

[edit]As the war drew to a close, two competing visions for the post-war world emerged. The first was offered by the International Federation of Trade Unions (IFTU), which called for a meeting in Bern, Switzerland, in July 1919. The Bern meeting would consider both the future of the IFTU and the various proposals which had been made in the previous few years. The IFTU also proposed including delegates from the Central Powers as equals. Samuel Gompers, president of the AFL, boycotted the meeting, wanting the Central Powers delegates in a subservient role as an admission of guilt for their countries' role in bringing about war. Instead, Gompers favoured a meeting in Paris which would consider President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points only as a platform. Despite the American boycott, the Bern meeting went ahead as scheduled. In its final report, the Bern Conference demanded an end to wage labour and the establishment of socialism. If these ends could not be immediately achieved, then an international body attached to the League of Nations should enact and enforce legislation to protect workers and trade unions.[31]

Commission on International Labour Legislation

[edit]Meanwhile, the Paris Peace Conference sought to dampen public support for communism. Subsequently, the Allied Powers agreed that clauses should be inserted into the emerging peace treaty protecting labour unions and workers' rights, and that an international labour body be established to help guide international labour relations in the future. The advisory Commission on International Labour Legislation was established by the Peace Conference to draft these proposals. The Commission met for the first time on 1 February 1919, and Gompers was elected as the chairman.[31]

Two competing proposals for an international body emerged during the Commission's meetings. The British proposed establishing an international parliament to enact labour laws which each member of the League would be required to implement. Each nation would have two delegates to the parliament, one each from labour and management.[31] An international labour office would collect statistics on labour issues and enforce the new international laws. Philosophically opposed to the concept of an international parliament and convinced that international standards would lower the few protections achieved in the United States, Gompers proposed that the international labour body be authorized only to make recommendations and that enforcement be left up to the League of Nations. Despite vigorous opposition from the British, the American proposal was adopted.[31]

Gompers also set the agenda for the draft charter protecting workers' rights. The Americans made 10 proposals. Three were adopted without change: That labour should not be treated as a commodity; that all workers had the right to a wage sufficient to live on; and that women should receive equal pay for equal work. A proposal protecting the freedom of speech, press, assembly, and association was amended to include only freedom of association. A proposed ban on the international shipment of goods made by children under the age of 16 was amended to ban goods made by children under the age of 14. A proposal to require an eight-hour work day was amended to require the eight-hour work day or the 40-hour work week (an exception was made for countries where productivity was low). Four other American proposals were rejected. Meanwhile, international delegates proposed three additional clauses, which were adopted: One or more days for weekly rest; equality of laws for foreign workers; and regular and frequent inspection of factory conditions.[31]

The Commission issued its final report on 4 March 1919, and the Peace Conference adopted it without amendment on 11 April. The report became Part XIII of the Treaty of Versailles.[31]

Interwar period

[edit]The first annual International Labour Conference (ILC) began on 29 October 1919 at the Pan American Union Building in Washington, D.C.[32] and adopted the first six International Labour Conventions, which dealt with hours of work in industry, unemployment, maternity protection, night work for women, minimum age, and night work for young persons in industry.[33] The prominent French socialist Albert Thomas became its first director-general.

Despite open disappointment and sharp critique, the revived International Federation of Trade Unions (IFTU) quickly adapted itself to this mechanism. The IFTU increasingly oriented its international activities around the lobby work of the ILO.[34]

At the time of establishment, the U.S. government was not a member of ILO, as the US Senate rejected the covenant of the League of Nations, and the United States could not join any of its agencies. Following the election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt to the U.S. presidency, the new administration made renewed efforts to join the ILO without league membership. On 19 June 1934, the U.S. Congress passed a joint resolution authorizing the president to join ILO without joining the League of Nations as a whole. On 22 June 1934, the ILO adopted a resolution inviting the U.S. government to join the organization. On 20 August 1934, the U.S. government responded positively and took its seat at the ILO.

Wartime and the United Nations

[edit]During the Second World War, when Switzerland was surrounded by German troops, ILO director John G. Winant made the decision to leave Geneva. In August 1940, the government of Canada officially invited the ILO to be housed at McGill University in Montreal. Forty staff members were transferred to the temporary offices and continued to work from McGill until 1948.[35]

The ILO became the first specialized agency of the United Nations system after the demise of the League in 1946.[36] Its constitution, as amended, includes the Declaration of Philadelphia (1944) on the aims and purposes of the organization.

Cold War era

[edit]

Beginning in the late 1950s the organization was under pressure to make provisions for the potential membership of ex-colonies which had become independent; in the Director General's report of 1963 the needs of the potential new members were first recognized.[37] The tensions produced by these changes in the world environment negatively affected the established politics within the organization[38] and they were the precursor to the eventual problems of the organization with the USA.

In July 1970, the United States withdrew 50% of its financial support to the ILO following the appointment of an assistant director-general from the Soviet Union. This appointment (by the ILO's British director-general, C. Wilfred Jenks) drew particular criticism from AFL–CIO president George Meany and from New Jersey Assemblyman John E. Rooney. However, the funds were eventually paid.[39][40]

On 12 June 1975, the ILO voted to grant the Palestine Liberation Organization observer status at its meetings. Representatives of the United States and Israel walked out of the meeting. The U.S. House of Representatives subsequently decided to withhold funds. The United States gave notice of full withdrawal on 6 November 1975, stating that the organization had become politicized. The United States also suggested that representation from communist countries was not truly "tripartite"—including government, workers, and employers—because of the structure of these economies. The withdrawal became effective on 1 November 1977.[39]

The United States returned to the organization in 1980 after extracting some concession from the organization. It was partly responsible for the ILO's shift away from a human rights approach and towards support for the Washington Consensus. Economist Guy Standing wrote "the ILO quietly ceased to be an international body attempting to redress structural inequality and became one promoting employment equity".[41]

In 1981, the government of Poland declared martial law. It interrupted the activities of Solidarność detained many of its leaders and members. The ILO Committee on Freedom of Association filed a complaint against Poland at the 1982 International Labour Conference. A Commission of Inquiry established to investigate found Poland had violated ILO Conventions No. 87 on freedom of association[42] and No. 98 on trade union rights,[43] which the country had ratified in 1957. The ILO and many other countries and organizations put pressure on the Polish government, which finally gave legal status to Solidarność in 1989. During that same year, there was a roundtable discussion between the government and Solidarnoc which agreed on terms of relegalization of the organization under ILO principles. The government also agreed to hold the first free elections in Poland since the Second World War.[44]

Offices

[edit]ILO headquarters

[edit]

The ILO is headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland. In its first months of existence in 1919, it offices were located in London, only to move to Geneva in the summer 1920. The first seat in Geneva was on the Pregny hill in the Ariana estate, in the building that used to host the Thudicum boarding school and currently the headquarters of the International Committee of the Red Cross. As the office grew, the Office relocated to a purpose-built headquarters by the shores of lake Leman, designed by Georges Épitaux and inaugurated in 1926 (currently the seat of the World Trade Organization). During the Second World War the Office was temporarily relocated to McGill University in Montreal, Canada.

The current seat of the ILO's headquarters is located on the Pregny hill, not far from its initial seat. The building, a biconcave rectangular block designed by Eugène Beaudoin, Pier Luigi Nervi and Alberto Camenzind, was purpose-built between 1969–1974 in a severe rationalist style and, at the time of construction, constituted the largest administrative building in Switzerland.[45]

Regional offices

[edit]- Regional Office for Africa, in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire

- Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, in Bangkok, Thailand

- Regional Office for Europe and Central Asia, in Geneva, Switzerland

- Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean, in Lima, Peru

- Regional Office for the Arab States, in Beirut, Lebanon

Sub-regional offices

[edit]Called "Decent Work Technical Support Teams (DWT)", they provide technical support to the work of a number of countries under their area of competence.

- DWT for North Africa, in Cairo, Egypt

- DWT for West Africa, in Dakar, Senegal

- DWT for Eastern and Southern Africa, in Pretoria, South Africa

- DWT for Central Africa, in Yaoundé, Cameroon

- DWT for the Arab States, in Beirut, Lebanon

- DWT for South Asia, in New Delhi, India

- DWT for East and South-East Asia and the Pacific, in Bangkok, Thailand

- DWT for Central and Eastern Europe, in Budapest, Hungary

- DWT for Eastern Europe and Central Asia, in Moscow, Russia

- DWT for the Andean Countries, in Lima, Peru

- DWT for the Caribbean Countries, in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago

- DWT for Central American Countries, in San José, Costa Rica

- DWT for Countries of the South Cone of Latin America, in Santiago, Chile

Country and liaison offices

[edit]- In Africa: Abidjan, Abuja, Addis Ababa, Algiers, Antananarivo, Cairo, Dakar, Dar es Salaam, Harare, Kinshasa, Lusaka, Pretoria, Yaoundé

- In the Arab States: Beirut, Doha,[46][47] Jerusalem

- In Asia and the Pacific: Bangkok, Beijing, Colombo, Dhaka, Hanoi, Islamabad, Jakarta, Kabul, Kathmandu, Manila, New Delhi, Suva, Tokyo, Yangon

- In Europe and Central Asia: Ankara, Berlin, Brussels, Budapest, Lisbon, Madrid, Moscow, Paris, Rome

- In the Americas: Brasília, Buenos Aires, Mexico City, New York, Lima, Port-of-Spain, San José, Santiago, Washington, D.C.

Activities

[edit]Conventions

[edit]Through July 2018, the ILO had adopted 189 conventions. If these conventions are ratified by enough governments, they come in force. However, ILO conventions are considered international labour standards regardless of ratification. When a convention comes into force, it creates a legal obligation for ratifying nations to apply its provisions.

Every year the International Labour Conference's Committee on the Application of Standards examines a number of alleged breaches of international labour standards. Governments are required to submit reports detailing their compliance with the obligations of the conventions they have ratified. Conventions that have not been ratified by member states have the same legal force as recommendations.

In 1998, the 86th International Labour Conference adopted the Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work. This declaration contains four fundamental policies:[48]

- The right of workers to associate freely and bargain collectively

- The end of forced and compulsory labour

- The end of child labour

- The end of unfair discrimination among workers

The ILO asserts that its members have an obligation to work towards fully respecting these principles, embodied in relevant ILO conventions. The ILO conventions that embody the fundamental principles have now been ratified by most member states.[49]

Protocols are always linked to Conventions, even though they are international treaties they do not exist on their own. As with Conventions, Protocols can be ratified.

Recommendations do not have the binding force of conventions and are not subject to ratification. Recommendations may be adopted at the same time as conventions to supplement the latter with additional or more detailed provisions. In other cases recommendations may be adopted separately and may address issues separate from particular conventions.[50]

International Labour Conference

[edit]Once a year, the ILO organizes the International Labour Conference (ILC) in Geneva to set the broad policies of the ILO, including conventions and recommendations.[51] Also known as the "international parliament of labour", the conference makes decisions about the ILO's general policy, work programme and budget and also elects the Governing Body.

The first conference took place in 1919:[52] see Interwar period above.

Each member state is represented by a delegation composed of two government delegates, an employer delegate, a worker delegate. All of them have individual voting rights and all votes are equal, regardless of the population of the delegate's member State. The employer and worker delegates are normally chosen in agreement with the most representative national organizations of employers and workers. Usually, the workers and employers' delegates coordinate their voting. All delegates have the same rights and are not required to vote in blocs.

Delegates can attend with advisers and substitute delegates,[53] and all have the same rights: they can express themselves freely and vote as they wish. This diversity of viewpoints does not prevent decisions from being adopted by very large majorities or unanimously.[citation needed]

Heads of State and prime ministers also participate in the Conference. International organizations, both governmental and others, also attend but as observers.

The 109th session of the International Labour Conference was delayed from 2020 to May 2021 and was held online because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The first meeting was on 20 May 2021 in Geneva for the election of its officers. Further sittings were held in June, November and December.[54] The 110th session took place from 27 May to 11 June 2022.[55] The 111th session of the International Labour Conference took place in June 2023.[56]

Global forum meetings

[edit]The ILO organizes regular international tripartite gatherings and global dialogue fora on issues of interest to specific sectors of business and employment,[57] for example on supply chain safety in the packing of containers for global shipping (2011),[58] and on employment conditions in early childhood education (2012).[59]

Labour statistics

[edit]The ILO is a major provider of labour statistics. Labour statistics are an important tool for its member states to monitor their progress toward improving labour standards. As part of their statistical work, ILO maintains several databases.[60] This database covers 11 major data series for over 200 countries. In addition, ILO publishes a number of compilations of labour statistics, such as the Key Indicators of Labour Markets[61] (KILM). KILM covers 20 main indicators on labour participation rates, employment, unemployment, educational attainment, labour cost, and economic performance. Many of these indicators have been prepared by other organizations. For example, the Division of International Labour Comparisons of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics prepares the hourly compensation in manufacturing indicator.[62]

The U.S. Department of Labor also publishes a yearly report containing a List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor[63] issued by the Bureau of International Labor Affairs. The December 2014 updated edition of the report listed a total of 74 countries and 136 goods.

The ILO is the custodian agency for nine of the 17 indicators of Sustainable Development Goal 8 (SDG 8).[64]: 5 [65] This goal is about "decent work and economic growth".[66] For example, ILO is the agency for Indicator 8.b.1 of Target 8.b. The wording of this target is: "By 2020, develop and operationalize a global strategy for youth employment and implement the Global Jobs Pact of the International Labour Organization".[67] As such, ILO is in charge of the data gathering for the progress of the Global Youth Empowerment Strategy.[68]

Training and teaching units

[edit]The International Training Centre of the International Labour Organization (ITCILO) is based in Turin, Italy.[69] Together with the University of Turin Department of Law, the ITC offers training for ILO officers and secretariat members, as well as offering educational programmes. The ITC offers more than 450 training and educational programmes and projects every year for some 11,000 people around the world.

For instance, the ITCILO offers a Master of Laws programme in management of development, which aims specialize professionals in the field of cooperation and development.[70]

Responses to issues

[edit]Child labour

[edit]

Child labour is often defined as work that deprives children of their childhood, potential, dignity, and is harmful to their physical and mental development. Child labour refers to work that is mentally, physically, socially or morally dangerous and harmful to children. Further, it can involve interfering with their schooling by depriving them of the opportunity to attend school, obliging them to leave school prematurely, or requiring them to attempt to combine school attendance with excessively long and heavy work.[71][72][73]

The ILO's International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC) was created in 1992 with the overall goal of the progressive elimination of child labour, which was to be achieved through strengthening the capacity of countries to deal with the problem and promoting a worldwide movement to combat child labour. The IPEC currently has operations in 88 countries, with an annual expenditure on technical cooperation projects that reached over US$61 million in 2008. It is the largest programme of its kind globally and the biggest single operational programme of the ILO.

The number and range of the IPEC's partners have expanded over the years and now include employers' and workers' organizations, other international and government agencies, private businesses, community-based organizations, NGOs, the media, parliamentarians, the judiciary, universities, religious groups and children and their families.

The IPEC's work to eliminate child labour is an important facet of the ILO's Decent Work Agenda.[74] Child labour prevents children from acquiring the skills and education they need for a better future.[75]

The ILO also hosts a Global Conference on the Elimination of Child Labour every four years. The most recent conference was held in Durban, South Africa from 15 to 20 May 2022.[76]

The ILO has established the World Day Against Child Labour on June 12 as an annual event starting in 2002 to raise awareness and prompt action to tackle child labour worldwide. Coinciding with the Sustainable Development Goals, the event particularly targets the eradication of its worst forms, like slavery and the use of child soldiers, by 2025. The ILO distinguishes between detrimental child labour, which hinders children's development and education, and acceptable work that supports their growth and learning.[77]

In 2023, the World Day's theme, 'Social Justice for All. End Child Labour!', calls for reinvigorated global efforts towards achieving social justice and underscores the critical need for the universal ratification and enforcement of ILO Conventions No. 138 and No. 182 to protect all children from child labour.[78]

Exceptions in indigenous communities

[edit]Because of different cultural views involving labour, the ILO developed a series of culturally sensitive mandates, including convention Nos. 169, 107, 138, and 182, to protect indigenous culture, traditions, and identities. Convention Nos. 138 and 182 lead in the fight against child labour, while Nos. 107 and 169 promote the rights of indigenous and tribal peoples and protect their right to define their own developmental priorities.[79]

In many indigenous communities,[example needed] parents believe that children learn important life lessons through the act of work and through the participation in daily life. Working is seen as a learning process preparing children of the future tasks they will eventually have to do as an adult.[80] It is a belief that the family's and child well-being and survival is a shared responsibility between members of the whole family. They also see work as an intrinsic part of their child's developmental process. While these attitudes toward child work remain, many children and parents from indigenous communities still highly value education.[79]

Forced labour

[edit]

The ILO has considered the fight against forced labour to be one of its main priorities. During the interwar years, the issue was mainly considered a colonial phenomenon, and the ILO's concern was to establish minimum standards protecting the inhabitants of colonies from the worst abuses committed by economic interests.[81] After 1945, the goal became to set a uniform and universal standard, determined by the higher awareness gained during World War II of politically and economically motivated systems of forced labour, but debates were hampered by the Cold War and by exemptions claimed by colonial powers. Since the 1960s, declarations of labour standards as a component of human rights have been weakened by government of postcolonial countries claiming a need to exercise extraordinary powers over labour in their role as emergency regimes promoting rapid economic development.[82][83]

In June 1998, the International Labour Conference adopted a Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work and its follow-up that obligates member states to respect, promote and realize freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining, the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labour, the effective abolition of child labour, and the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation.

In November 2001, following the publication of the InFocus Programme's first global report on forced labour, the ILO's governing body created a special action programme to combat forced labour (SAP-FL),[84] as part of broader efforts to promote the 1998 Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work and its follow-up. The SAP-FL was created in November 2001 "to tackle the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labour, one of its foremost concerns, through both technical assistance and promotional means."[85] SAP-FL has developed indicators of forced labour practices[86] and published survey reports on forced labour.[87]

In 2013, the SAP-FL was integrated into the ILO's Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work Branch (FUNDAMENTALS)[88] bringing together the fight against forced and child labour and working in the context of Alliance 8.7.[89]

One major tool to fight forced labour was the adoption of the ILO Forced Labour Protocol by the International Labour Conference in 2014. It was ratified for the second time in 2015 and on 9 November 2016 it entered into force. The new protocol brings the existing ILO Convention 29 on Forced Labour,[90] adopted in 1930, into the modern era to address practices such as human trafficking. The accompanying Recommendation 203 provides technical guidance on its implementation.[91]

In 2015, the ILO launched a global campaign to end modern slavery, in partnership with the International Organization of Employers (IOE) and the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC). The 50 for Freedom Campaign aims to mobilize public support and encourage countries to ratify the ILO's Forced Labour Protocol.[84]

Role of civil society organizations in the International Labour Conference

[edit]Civil society organizations (CSOs) play a supportive and increasingly recognized role in the work of the International Labour Organization (ILO), particularly in relation to the annual International Labour Conference (ILC)—the ILO’s highest decision-making body.[92] Through participation in the ILC and other ILO-led initiatives, CSOs contribute to the advancement of labor rights and the promotion of social justice on a global scale.

The ILO encourages engagement with CSOs as part of its tripartite approach to labor governance, which includes representatives from governments, employers, and workers. Civil society actors bring additional perspectives, often representing marginalized groups, informal workers, or specific thematic concerns (e.g., gender equity, forced labor, or child labor).

Opportunities for participation

[edit]CSOs can engage with the ILO and its annual Conference through several mechanisms:

- Accreditation[93] – CSOs may apply for accreditation to attend the International Labour Conference as observers or participants in side events. Accreditation follows formal procedures established by the ILO and is typically granted to international NGOs or networks with relevant expertise in labor standards and rights.

- Policy Submissions and Reports– Accredited organizations may submit written reports, proposals, and observations relevant to the agenda of the Conference. These contributions inform the deliberations on labor rights, occupational safety, decent work, and social protection.

- Partnership and Collaboration – Beyond the Conference, the ILO maintains ongoing collaboration with CSOs to promote better working conditions, inclusive labor policies, and the implementation of international labor standards. CSOs may partner with the ILO in research, advocacy, technical cooperation, and monitoring initiatives.

More information on the ILO’s engagement with civil society is available at: https://www.ilo.org/partnering-development/civil-society-ilo-partnership

Minimum wage law

[edit]To protect the right of labours for fixing minimum wage, ILO has created Minimum Wage-Fixing Machinery Convention, 1928, Minimum Wage Fixing Machinery (Agriculture) Convention, 1951 and Minimum Wage Fixing Convention, 1970 as minimum wage law.

Commercialized sex

[edit]From the moment its creation in the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, the ILO has been concerned with the controversial issue of commercial sex. Prior to the creation of the ILO and League of Nations, the issue of sex work had been exclusively under the jurisdiction of the state, now, the ILO and League of Nations believed the issue transcended borders and within their jurisdiction.[94] In the early twentieth, commercialized sex was considered both immoral and criminal activity. Initially, the ILO strongly believed prostitution was linked to vulnerable single working women emigrating to other nations without being under the paternal supervision of a man.[94] After the widespread destruction caused by World War I, the ILO saw prostitution as spreading contagion requiring regulation.[95] Under the leadership of the French socialist Albert Thomas, the ILO created a medical division whose primary focus was on male sailors whose lives were viewed as "nomadic" and "promiscuous", which made these men susceptible to infection of STD's.[95] After the conclusion of the Genoa maritime conference in 1920, the ILO proclaimed itself as the critical leader of the prevention and treatment of STD's in sailors. In the interwar years, the ILO also sought to protect female workers in dangers trades, but delegates to ILO Conferences did not consider the sex trade to be "work", which was conceived of as industrial labor.[96] The ILO believed that if women worked industrial jobs, this would be a deterrent from them living immoral lives. In order to make these industrial jobs more attractive, the ILO promoted better wages and safer working conditions, both intended to prevent women from falling victim to the temptation of the sex trades.[97]

Following the creation of the United Nations, the ILO took a back seat to the newly formed organization on the issue of commercialized sex. The UN Commission on the Status of Women called for abolishing both sex trafficking and prostitution.[98] In the 1950s, the UN Economic and Social Council and the International Police Organization sought to end any activity that resembled slavery, classifying sex trafficking and prostitution as criminal rather than labor issues.[98]

Beginning in 1976, the ILO and other organizations began to examine the working and living conditions of rural women in developing countries.[99] One example the ILO investigated was the go-go bars and the growing phenomenon of hired wives in Thailand, which both thrived because the development of U.S. military bases in the region.[99] In the late 1970s, the ILO established the Programme on Rural Women, which investigated the involvement of young masseuses in the sex trade in Bangkok.[99] It was critical because it was the first time in the history of the ILO or any of its branches that prostitution was described as a form of labor.[99] In the decades that followed, the increase in sex tourism and the exploding AIDS epidemic strengthened ILO interest in the commercial sex trade.[100]

HIV/AIDS

[edit]The International Labour Organization (ILO) is the lead UN-agency on HIV workplace policies and programmes and private sector mobilization. ILOAIDS[101] is the branch of the ILO dedicated to this issue.

The ILO has been involved with the HIV response since 1998, attempting to prevent potentially devastating impact on labour and productivity and that it says can be an enormous burden for working people, their families and communities. In June 2001, the ILO's governing body adopted a pioneering code of practice on HIV/AIDS and the world of work,[102] which was launched during a special session of the UN General Assembly.

The same year, ILO became a cosponsor of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS).

In 2010, the 99th International Labour Conference adopted the ILO's recommendation concerning HIV and AIDS and the world of work, 2010 (No. 200),[103] the first international labour standard on HIV and AIDS. The recommendation lays out a comprehensive set of principles to protect the rights of HIV-positive workers and their families, while scaling up prevention in the workplace. Working under the theme of Preventing HIV, Protecting Human Rights at Work, ILOAIDS undertakes a range of policy advisory, research and technical support functions in the area of HIV and AIDS and the world of work. The ILO also works on promoting social protection as a means of reducing vulnerability to HIV and mitigating its impact on those living with or affected by HIV.

ILOAIDS ran a "Getting to Zero"[104] campaign to arrive at zero new infections, zero AIDS-related deaths and zero-discrimination by 2015.[105][needs update] Building on this campaign, ILOAIDS is executing a programme of voluntary and confidential counselling and testing at work, known as VCT@WORK.[106]

Migrant workers

[edit]As the word "migrant" suggests, migrant workers refer to those who moves from one country to another to do their job. For the rights of migrant workers, the first ILC adopted a recommendation on equality and coordination,[52] and the ILO has adopted conventions, including Migrant Workers (Supplementary Provisions) Convention, 1975 and United Nations Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families in 1990.[107]

Domestic workers

[edit]Domestic workers are those who perform a variety of tasks for and in other peoples' homes. For example, they may cook, clean the house, and look after children. Yet they are often the ones with the least consideration, excluded from labour and social protection. This is mainly due to the fact that women have traditionally carried out the tasks without pay.[108] For the rights and decent work of domestic workers including migrant domestic workers, ILO has adopted the Convention on Domestic Workers on 16 June 2011.

Environmental sustainability

[edit]The ILO has been on working on integrating environmental sustainability into its activities (or greening its activities) and the broader discourse since the 1970s. For example, some of ILO's reports in 1972 to 1975 have investigated linkages between occupational safety and health, economic development and environmental protection.[109] In the 2000s ILO began to promote a "socially just transition to green jobs". The organisation defined green jobs as "decent jobs that contribute to preserving and restoring the environment".[109]

Since 2017, the concept of just transition has been firmly embedded within the ILO’s position. For example its Centenary Declaration for the Future of Work in 2019 stated that: "[...] the ILO must direct its efforts to: (i) ensuring a just transition to a future of work that contributes to sustainable development in its economic, social and environmental dimensions".[110]: 3 A just transition focuses on the connection between energy transition and equitable approaches to decarbonization that support broader development goals.[111][112]

The ILO has also looked at the transition to a green economy, and the impact thereof on employment. It came to the conclusion a shift to a greener economy could create 24 million new jobs globally by 2030, if the right policies are put in place. Also, if a transition to a green economy were not to take place, 72 million full-time jobs may be lost by 2030 due to heat stress, and temperature increases will lead to shorter available work hours, particularly in agriculture.[113][114]

Awards

[edit]In 1969, the ILO received the Nobel Peace Prize for improving fraternity and peace among nations, pursuing decent work and justice for workers, and providing technical assistance to other developing nations.[115][116]

See also

[edit]- Administrative Tribunal of the International Labour Organization

- Criticism of capitalism

- Labor theory of value

- League of Nations archives

- Seoul Declaration on Safety and Health at Work, 2008

- Social clause, the integration of seven core ILO labour rights conventions into trade agreements

- United Nations Global Compact, launched in 2000, encouraging businesses to adopt sustainable and socially responsible policies

References

[edit]- ^ a b Staff writer (2024). "International Labour Organization (ILO)". UIA Global Civil Society Database. uia.org. Brussels, Belgium: Union of International Associations. Yearbook of International Organizations Online. Retrieved 24 December 2024.

- ^ "PERSONNEL BY ORGANIZATION | United Nations - CEB".

- ^ "Mission and impact of the ILO". International Labour Organization. 28 January 2024. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ "Departments and offices". International Labour Organization. Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "Labour standards". International Labour Organization. Archived from the original on 1 May 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "Introduction to International Labour Standards". International Labour Organization. Archived from the original on 31 December 2023.

- ^ "Global Commission on the Future of Work". International Labour Organization. 14 August 2017. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ "A human-centred agenda needed for a decent future of work". International Labour Organization. 22 January 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ "International Labour Organization". britannica.com. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ "Home". Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ^ "Governing Body". International Labour Organization. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ "Governing Body elections (International Labour Conference (ILC))". www.ilo.org. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ Article 7, ILO Constitution

- ^ "ILO Constitution". International Labour Organization.

- ^ "Gilbert Houngbo will be the first African to lead the ILO". republicoftogo.com. 25 March 2022.

- ^ "Guy Ryder re-elected as ILO Director-General for a second term". International Labour Organization. 7 November 2016.

- ^ Taibi, FADLI; Technology, Archos (17 January 2024). "ILO DG Lauds Morocco's Experience in Implementing Social State Policy". MapNews (in French). Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ ILO official site: Former Directors-General

- ^ "ILO Constitution Article 3". Ilo.org. Archived from the original on 25 December 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ "ILO Declaration on Fundamental Prinicples & Rights at Work". Equality & Human Rights Commission. 10 November 2020. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ "The International Labour Organization (ILO) – Membership". Encyclopedia of the Nations. Advameg, Inc. 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ^ International Labour Organization. (n.d.). About the ILO in the Cook Islands. Retrieved June 26, 2021, from https://www.ilo.org/suva/countries-covered/cook-islands/WCMS_410209/lang--en/index.htm

- ^ a b "Key document - ILO Constitution". www.ilo.org. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ a b c Norman F. Dufty, "Organizational Growth and Goal Structure: The Case of the ILO", (1972) 26 (3) International Organization 479 accessed 24 August 2011

- ^ a b Joseph Sulkowski, "The Competence of the International Labor Organization Under the United Nations System", (1951) 45 (2) The American Journal of International Law 286 accessed 24 August 2011.

- ^ O'Higgins, P., 'Labour is not a Commodity' — an Irish Contribution to International Labour Law' (1997) 26(3) Industrial Law Journal 225–234

- ^ a b VanDaele, Jasmien (2005). "Engineering Social Peace: Networks, Ideas, And the Founding of the International Labour Organization". International Review of Social History. 50 (3): 435–466. doi:10.1017/S0020859005002178.

- ^ Haimson, Leopold H. and Sapelli, Giulio. Strikes, Social Conflict, and the First World War: An International Perspective. Milan: Fondazione Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, 1992. ISBN 88-07-99047-4

- ^ Shapiro, Stanley (1976). "The Passage of Power: Labor and the New Social Order". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 120 (6): 464–474. JSTOR 986599.

- ^ Ayusawa, Iwao Frederick. International Labour Legislation. Clark, N.J.: Lawbook Exchange, 2005. ISBN 1-58477-461-4

- ^ a b c d e f g Foner, Philip S. History of the Labor Movement in the United States. Vol. 7: Labor and World War I, 1914–1918. New York: International Publishers, 1987. ISBN 0-7178-0638-3

- ^ "International Labor Conference. October 29, 1919 – November 29, 1919" (PDF). International Labour Organization. Washington Government Printing Office 1920. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 October 2014.

- ^ "Origins and history". International Labour Organization. 28 January 2024.

- ^ Reiner Tosstorff (2005). "The International Trade-Union Movement and the Founding of the International Labour Organization" (PDF). International Review of Social History. 50 (3): 399–433. doi:10.1017/S0020859005002166. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 March 2013.

- ^ "ILO". International Labour Organization. 28 January 2024.

- ^ "Photo Gallery". ILO. 2011. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ^ ILO: 'Programme and Structure of the ILO':report of the Director General, 1963.

- ^ R. W. Cox, "ILO: Limited Monarchy" in R.W. Cox and H. Jacobson The Anatomy of Influence: Decision Making in International Organization Yale University Press, 1973 pp.102-138

- ^ a b Beigbeder, Yves (1979). "The United States' Withdrawal from the International Labor Organization" (PDF). Relations Industrielles / Industrial Relations. 34 (2): 223–240. doi:10.7202/028959ar. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 June 2013.

- ^ "Communication from the Government of the United States" (PDF). International Labour Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015.. United States letter dated 5 November 1975 containing notice of withdrawal from the International Labour Organization.

- ^ Standing, Guy (2008). "The ILO: An Agency for Globalization?" (PDF). Development and Change. 39 (3): 355–384. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.593.4931. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.2008.00484.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ "ILO Conventions No. 98". International Labour Organization.

- ^ "ILO Conventions No. 98". International Labour Organization.

- ^ "The ILO and the story of Solidarnoc". International Labour Organization. 3 May 2016.

- ^ "A house for social justice - past, present and future". International Labour Organization. 9 November 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ "New labour laws in Qatar benefiting migrant workers a 'momentous step forward': ILO". 17 October 2019.

- ^ "ILO inaugurates its first project office in Qatar". 30 April 2018.

- ^ "ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work". Rights at Work. International Labour Organization. 1998. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ^ See the list of ratifications at Ilo.org

- ^ "Recommendations". International Labour Organization.

- ^ "International Labour Conference". International Labour Organization. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ a b Vittin-Balima, C., Migrant workers: The ILO standards, archived at Bibliothek der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, accessed 15 December 2023

- ^ ILO, Final list of delegations, International Labour Conference, 110th Session, 2022, accessed 15 December 2023

- ^ "109th International Labour Conference to be held virtually, opening in May". 17 May 2021.

- ^ ILO, 110th International Labour Conference, accessed 25 September 2022

- ^ ILO, 111th Session of the International Labour Conference, 5–16 June 2023, accessed 15 December 2023

- ^ ILO, Sectoral meetings, accessed 19 January 2024

- ^ ILO, "Any fool can stuff a container?": ILO to discuss safety in growing container industry, published 14 February 2011, accessed 19 January 2024

- ^ ILO (2012). Early childhood education and educators: Global Dialogue Forum on Conditions of Personnel in Early Childhood Education, Geneva, 22–23 February 2012. Geneva: International Labour Office, Sectoral Activities Department.

- ^ "ILO statistics overview". International Labour Organization. 16 April 2024.

- ^ "Key Indicators of the Labour Market (KILM)". International Labour Organization. 11 December 2013.

- ^ "Hourly compensation costs" (PDF). International Labour Organization, KILM 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ "List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor". U.S. Department of Labor. Archived from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ ILO (2019). Time to act for SDG 8: integrating decent work, sustained growth and environmental integrity. Geneva: International Labour Office. ISBN 978-92-2-133677-8.

- ^ "Sustainable Development Goal #8: Decent Work and Economic Growth | International Labour Organization". www.ilo.org. 28 January 2024. Retrieved 6 May 2025.

- ^ "United Nations (2018) Economic and Social Council, Conference of European Statisticians, Geneva" (PDF). United Nations, Geneva. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ United Nations (2017) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017, Work of the Statistical Commission pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/71/313)

- ^ "United Nations (2018) Economic and Social Council, Conference of European Statisticians, Geneva" (PDF). United Nations, Geneva. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ BIZZOTTO. "ITCILO – International Training Center". Archived from the original on 10 July 2015. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- ^ "LLM Guide (IP LLM) – University of Torino, Faculty of Law". llm-guide.com. Archived from the original on 18 March 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ Ahmady, Kameel 2021:Traces of Exploitation in the World of Childhood (A Comprehensive Research on Forms, Causes and Consequences of Child Labour in Iran). Avaye Buf Publisher, Denmark.

- ^ "Child labour | UNICEF". www.unicef.org. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Child labour has a profound impact on the health and wellbeing of children - European Commission". international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Decent work - Themes". Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- ^ Von Braun, Joachim (1995). Von Braun (ed.). Employment for poverty reduction and food security. IFPRI Occasional Papers. Intl Food Policy Res Inst. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-89629-332-8. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ "5th Global Conference on the Elimination of Child Labour". www.5thchildlabourconf.org. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ Nations, United. "World Day Against Child Labour - Background | United Nations". United Nations. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ Nations, United. "World Day Against Child Labour". United Nations. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ a b Larsen, P.B. Indigenous and tribal children: assessing child labour and education challenges. International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC), International Labour Office.

- ^ Guidelines for Combating Child Labour Among Indigenous Peoples. Geneva: International Labour Organization. 2006. ISBN 978-92-2-118748-6.

- ^ Burbank, Jane; Cooper, Frederick (2010). Empires in World History: Power and the Politics of Difference. Princeton University Press. p. 386. ISBN 978-0-691-12708-8.

- ^ Daniel Roger Maul (2007). "The International Labour Organization and the Struggle against Forced Labour from 1919 to the Present". Labor History. 48 (4): 477–500. doi:10.1080/00236560701580275. S2CID 154924697.

- ^ Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr.(1973) The Gulag Archipelago: An Experiment in Literary Investigation. Parisian publisher YMCA-Press.

- ^ a b "Forced labour, modern slavery and trafficking in persons | International Labour Organization". www.ilo.org. 28 January 2024. Retrieved 6 May 2025.

- ^ Plant, Roger; O'Reilly, Caroline (March 2003). "The ILO's Special Action Programme to Combat Forced Labour". International Labour Review. 142 (1): 73. doi:10.1111/j.1564-913X.2003.tb00253.x.

- ^ Chantavanich, Supang; Laodumrongchai, Samarn; Stringer, Christina (2016). "Under the shadow: Forced labour among sea fishers in Thailand". Marine Policy. 68: 6. Bibcode:2016MarPo..68....1C. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2015.12.015. ISSN 0308-597X. S2CID 155418604.

- ^ Lerche, Jens (October 2007). "A Global Alliance against Forced Labour? Unfree Labour, Neo-Liberal Globalization and the International Labour Organization". Journal of Agrarian Change. 7 (4): 427. Bibcode:2007JAgrC...7..425L. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0366.2007.00152.x.

- ^ "Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work Branch (FUNDAMENTALS) | International Labour Organization". www.ilo.org. 28 January 2024. Retrieved 6 May 2025.

- ^ "Alliance 8.7". alliance87.org.

- ^ "ILO Convention 29".

- ^ "ILO Recommendation 203".

- ^ "ILO Homepage | International Labour Organization". www.ilo.org. Retrieved 27 June 2025.

- ^ https://webapps.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---arabstates/---ro-beirut/documents/genericdocument/wcms_210580.pdf.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help)[dead link] - ^ a b Boris, Eileen; Rodriguez Garcia, Magaly (Winter 2021). "(In)Decent Work: Sex and the ILO". Journal of Women's History. 33 (4): 197. doi:10.1353/jowh.2021.0050. S2CID 245127678.

- ^ a b Boris, Eileen; Garcia, Magaly Rodriguez (Winter 2021). "(In)Decent Work: Sex and the ILO". Journal of Women's History. 33 (4): 198. doi:10.1353/jowh.2021.0050. S2CID 245127678.

- ^ Boris, Eileen; Garcia, Magaly Rodriguez (2021). "(In)Decent Work: Sex and the ILO". Journal of Women's History. 33 (4): 200. doi:10.1353/jowh.2021.0050. S2CID 245127678.

- ^ Boris, Eileen; Garcia, Magaly Rodriguez (Winter 2021). "(In)Decent Work: Sex and the ILO". Journal of Women's History. 33 (4): 201. doi:10.1353/jowh.2021.0050. S2CID 245127678.

- ^ a b Boris, Eileen; Garcia, Magaly Rodriguez (Winter 2021). "(In)Decent Work: Sex and the ILO". Journal of Women's History. 33 (4): 202. doi:10.1353/jowh.2021.0050. S2CID 245127678.

- ^ a b c d Garcia, Magaly Rodriguez (2018). Bosma, Ulbe; Hofmeester, Karin (eds.). The ILO and the Oldest Non-Profession in The Lifework of a Labor Historian: Essays in Honor of Marcel van der Linden. Brill. p. 105.

- ^ Garcia, Magaly Rodriguez (2018). Bosma, Ulbe; Hofmeester, Karin (eds.). The ILO and the Oldest Non-Profession in The Lifework of a Labor Historian: Essays in Honor of Marcel van der Linden. Brill. p. 106.

- ^ "HIV/AIDS and the World of Work Branch (ILOAIDS)". International Labour Organization.

- ^ "The ILO Code of Practice on HIV/AIDS and the World of Work". International Labour Organization. June 2001.

- ^ "Recommendation concerning HIV and AIDS and the World of Work, 2010 (No. 200)". International Labour Organization. 17 June 2010.

- ^ "Getting to Zero". Archived from the original on 9 December 2014.

- ^ "UNAIDS". unaids.org.

- ^ "VCT@WORK: 5 million women and men workers reached with Voluntary and confidential HIV Counseling and Testing by 2015". International Labour Organization. December 2014.

- ^ Kumaraveloo, K Sakthiaseelan; Lunner Kolstrup, Christina (3 July 2018). "Agriculture and musculoskeletal disorders in low- and middle-income countries". Journal of Agromedicine. 23 (3): 227–248. doi:10.1080/1059924x.2018.1458671. ISSN 1059-924X. PMID 30047854. S2CID 51719997.

- ^ "Domestic workers". International Labour Organization. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ a b Montesano, Francesco S.; Biermann, Frank; Kalfagianni, Agni; Vijge, Marjanneke J. (2023). "Can the Sustainable Development Goals Green International Organisations? Sustainability Integration in the International Labour Organisation". Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning. 25 (1): 1–15. Bibcode:2023JEPP...25....1M. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2021.1976123. ISSN 1523-908X. PMC 9893765. PMID 36744153.

- ^ ILO (2019) ILO Centenary Declaration for the Future of Work. Adopted at the 108th session of the International Labour Conference

- ^ "How just transition can help deliver the Paris Agreement | UNDP Climate Promise". climatepromise.undp.org. Retrieved 17 February 2025.

- ^ McCauley, Darren; Heffron, Raphael (1 August 2018). "Just transition: Integrating climate, energy and environmental justice". Energy Policy. 119: 1–7. Bibcode:2018EnPol.119....1M. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2018.04.014. hdl:10023/17583. ISSN 0301-4215.

- ^ Green economy could create 24 million new jobs

- ^ Greening with jobs – World Employment and Social Outlook 2018

- ^ "The Nobel Peace Prize 1969 - International Labour Organization Facts". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 5 July 2006.

- ^ "The Nobel Peace Prize 1969 - Presentation Speech". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- The International Training Centre of the ILO

- International Labour Organization, Declaration of Philadelphia (1944)

International Labour Organization

View on GrokipediaThe International Labour Organization (ILO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations founded in 1919 as part of the Treaty of Versailles, tasked with advancing social justice and internationally recognized human and labour rights through the formulation of international labour standards, policy development, and programmes aimed at decent work for women and men globally.[1][2] Its unique tripartite structure distinguishes it among UN agencies, incorporating equal representation from governments, employers, and workers of its 187 member states to deliberate on labour issues, reflecting the foundational conviction that lasting peace requires equitable social conditions to mitigate class conflicts and revolutionary pressures.[3][4] Headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, the ILO has promulgated 189 conventions establishing minimum standards on topics such as freedom of association, collective bargaining, abolition of forced labour, and elimination of child labour, many of which have influenced national legislation and contributed to reductions in exploitative practices through supervisory mechanisms and technical assistance.[5][6] Despite these accomplishments, including its 1969 Nobel Peace Prize for fostering international cooperation on labour issues, the organization faces criticism for weak enforcement powers, reliance on voluntary compliance, and tendencies toward prescriptive regulations that may impede market-driven employment growth, particularly in developing economies where empirical evidence suggests flexible labour markets correlate with faster poverty reduction.[7][8] The ILO's ongoing relevance is evident in its adaptation to contemporary challenges, such as the 2025 International Labour Conference discussions on standards for platform work and supply chain due diligence, yet its effectiveness remains constrained by geopolitical divisions among constituents and the persistence of informal economies evading formal standards, underscoring the limits of supranational institutions in overriding local economic incentives and sovereign priorities.[9][10]

Governance and Structure

Governing Body

The Governing Body serves as the executive organ of the International Labour Organization (ILO), overseeing the implementation of decisions from the International Labour Conference and directing the work of the International Labour Office.[11] It comprises 56 titular members—28 representing governments, 14 employers, and 14 workers—along with an equal number of deputies, maintaining the ILO's tripartite structure that includes equal representation from these constituencies.[12] Among the government members, 10 seats are permanently allocated to states of chief industrial importance: Brazil, China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom, and the United States.[13] The remaining 18 government seats, as well as all employer and worker seats, are elected by their respective groups at the International Labour Conference for three-year terms, with elections conducted separately to preserve group autonomy.[13] This composition ensures balanced influence across labor market stakeholders, though decisions often seek consensus to reflect the organization's collaborative ethos.[13] The Governing Body convenes three times annually in Geneva, typically in March, June, and November, to address key organizational matters.[14] Its primary functions include setting the agenda for the International Labour Conference, adopting the draft Programme and Budget for Conference approval, electing the Director-General, and formulating ILO policy on global labor standards and technical cooperation.[11] It also supervises the Office's activities, appoints committees for specific issues, and responds to emerging labor challenges through resolutions and recommendations.[13] Officers of the Governing Body, including a Chairperson (from the government group) and two Vice-Chairpersons (from employer and worker groups), are elected from among its members to coordinate sessions and represent the body externally.[11] While the tripartite framework promotes inclusive deliberation, the Governing Body's effectiveness can be influenced by geopolitical dynamics among member states, as evidenced by occasional debates over agenda priorities and budgetary allocations.[15]Director-General and Secretariat

The Director-General serves as the chief executive officer of the International Labour Organization (ILO), responsible for directing the work of the International Labour Office, preparing the agenda for the Governing Body and International Labour Conference, implementing decisions of these bodies, and representing the ILO externally.[14] The position is elected by the ILO Governing Body for a single five-year term, with the current Director-General, Gilbert F. Houngbo of Togo, elected on 25 March 2022 and assuming office on 1 October 2022 as the 11th holder of the role and the first from Africa.[16] Houngbo's mandate emphasizes advancing social justice amid global challenges, including forecasting 1.5% employment growth and 53 million new jobs worldwide in 2025.[17] Previous Directors-General have shaped the ILO's evolution through distinct priorities, such as early focus on post-World War I reconstruction under Albert Thomas and later adaptations to globalization under Juan Somavía.[18]| Director-General | Nationality | Term |

|---|---|---|

| Albert Thomas | French | 1919–1932 |

| Harold Butler | British | 1932–1938 |

| John G. Winant | American | 1939–1941 |

| ... (intervening) | ... | ... |

| Guy Ryder | British | 2012–2022 |

| Gilbert F. Houngbo | Togolese | 2022–present |

Membership and Decision-Making

The International Labour Organization comprises 187 member states, consisting of 186 United Nations member states and the Cook Islands.[1] Membership originated with 42 founding states in 1919, primarily signatories to the Treaty of Versailles, and has expanded through accession processes outlined in the ILO Constitution.[1] United Nations member states may join by formal notification to the ILO Director-General, while non-UN states require approval by a two-thirds majority of votes cast at the International Labour Conference (ILC).[23] Withdrawal is possible with two years' notice, though no state has invoked this provision since the organization's founding.[23] Decision-making in the ILO adheres to a tripartite structure, uniquely integrating representatives from governments, employers, and workers of member states, with each group holding equal formal status in deliberations.[14] This framework, embedded in the ILO Constitution, aims to balance state authority with private sector and labor interests, though implementation varies by national context, particularly in states where employer or worker organizations lack independence from government influence.[14] The ILC serves as the organization's supreme decision-making body, convening annually in Geneva typically in June, where it adopts international labor standards, approves the budget, and elects Governing Body members.[24] Each member state delegates four representatives—two from government, one from employers, and one from workers—each entitled to one vote, yielding approximately 748 total votes across tripartite groups.[14] Conventions require a two-thirds majority of votes cast by delegates present for adoption, while recommendations pass by simple majority; abstentions do not count toward the total.[24] The Governing Body functions as the executive arm, meeting three times annually to set the ILC agenda, oversee program implementation, and appoint the Director-General.[11] It consists of 56 titular members: 28 government representatives (including permanent seats for ten states of chief industrial importance—Brazil, China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom, and the United States—plus 18 elected), 14 employer members, and 14 worker members, all elected by their respective ILC constituencies for three-year terms.[25] An additional 66 deputy members provide substitutions. Decisions prioritize tripartite consensus but resort to majority voting when necessary, with government, employer, and worker votes weighted equally within their categories.[11] This structure has sustained the ILO's operations amid geopolitical shifts, though critiques from employer groups highlight occasional dominance by government-aligned worker representatives in certain member states.[11]Historical Development

Origins in the Treaty of Versailles (1919)

The International Labour Organization (ILO) originated in Part XIII of the Treaty of Versailles, signed on 28 June 1919, which concluded the First World War and established mechanisms for postwar international cooperation. This section of the treaty, comprising Articles 387 to 427, created a permanent body dedicated to improving labor conditions worldwide, predicated on the principle that enduring peace required addressing social injustices arising from exploitative work practices.[2][26][27] The treaty's labor provisions were drafted by the Commission on International Labour Legislation at the Paris Peace Conference, chaired by Samuel Gompers, president of the American Federation of Labor. The commission's report emphasized the need for international regulation to prevent competitive undercutting of wages and standards, influenced by wartime labor mobilizations and fears of social unrest. The resulting ILO Constitution preamble declared: "universal and lasting peace can be established only if it is based upon social justice," citing labor hardships such as inadequate wages, excessive hours, and child labor as threats to global stability.[28][29][30] A defining feature was the tripartite governance structure, mandating equal representation from governments, employers, and workers in the International Labour Conference and Governing Body, with non-governmental delegates holding independent voting rights—a departure from purely state-centric diplomacy. The International Labour Office was to be situated at the League of Nations headquarters, serving as the organization's secretariat.[1][31][26] The treaty entered into force on 10 January 1920, prompting the inaugural International Labour Conference in Washington, D.C., from 29 October to 29 November 1919. There, delegates adopted six conventions, including limits on industrial working hours to eight per day and the minimum age for employment, alongside recommendations on unemployment and maternity protection, operationalizing the ILO's mandate.[32][2]Interwar Expansion and Challenges

Following its establishment in 1919, the International Labour Organization expanded its membership during the 1920s, incorporating non-European states such as China, India, Japan, Persia (now Iran), Thailand, and South Africa by 1929, reflecting efforts to broaden its global reach beyond the initial 29 signatories of the Treaty of Versailles.[33] Further accessions in the early 1930s included Mexico in 1931, Iraq and Turkey in 1932, and by 1934, Afghanistan, Ecuador, the United States, and the Soviet Union joined, bringing total membership to around 60 states by the mid-1930s; Egypt followed in 1936.[31] This growth was supported by administrative expansion, with staff increasing from 250 officials in 1921 to 400 by 1930, though the organization remained understaffed relative to its ambitions.[34] The ILO adopted numerous conventions and recommendations in the interwar years, building on the nine conventions ratified in its first two years, which addressed hours of work, unemployment indemnity, maternity protection, and night work for women.[2] Key instruments included the Minimum Age (Sea) Convention of 1920, which set protections for young maritime workers and was later amended, and the Forced Labour Convention (No. 29) of 1930, prohibiting compulsory labor except in specific circumstances like military service or emergencies.[35][36] By the late 1930s, conventions extended to social insurance across various branches, influencing national policies on worker protections amid industrializing economies.[37] These efforts positioned the ILO at the forefront of international social reform, promoting standards against unregulated market forces.[38] The Great Depression, beginning in 1929, posed severe challenges, exacerbating unemployment and undermining ratification of standards as governments prioritized economic recovery over labor reforms; the ILO analyzed crisis impacts on labor markets, advocating interventions that challenged laissez-faire orthodoxy.[39][38] Membership from ideologically divergent states like the Soviet Union introduced tensions, as centralized control over unions clashed with tripartite principles.[40] The rise of fascist regimes in Italy, Germany, and Japan further strained the ILO, with Italy's participation marked by conflicts over fascist corporatist labor theories that subordinated workers to state-directed syndicates, leading to disputes at conferences.[41] Germany's withdrawal in 1933 and ambitions to supplant the ILO with a fascist-led alternative represented an existential threat, while Japan's expansionism diverted focus from multilateral cooperation.[42][43] These political pressures, combined with the Depression's fallout, limited enforcement but sustained the organization's role in documenting authoritarian encroachments on labor rights.[44]World War II Disruptions and UN Integration