Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

An arch is a curved vertical structure spanning an open space underneath it.[1] Arches may support the load above them, or they may perform a purely decorative role. As a decorative element, the arch dates back to the 4th millennium BC, but structural load-bearing arches became popular only after their adoption by the Ancient Romans in the 4th century BC.[2]

Arch-like structures can be horizontal, like an arch dam that withstands a horizontal hydrostatic pressure load.[3] Arches are usually used as supports for many types of vaults, with the barrel vault in particular being a continuous arch.[4] Extensive use of arches and vaults characterizes an arcuated construction, as opposed to the trabeated system, where, like in the architectures of ancient Greece, China, and Japan (as well as the modern steel-framed technique), posts and beams dominate.[5]

The arch had several advantages over the lintel, especially in masonry construction: with the same amount of material an arch can have larger span, carry more weight, and can be made from smaller and thus more manageable pieces.[6] Their role in construction was diminished in the middle of the 19th century with introduction of wrought iron (and later steel): the high tensile strength of these new materials made long lintels possible.

Basic concepts

[edit]Terminology

[edit]A true arch is a load-bearing arch with elements held together by compression.[7] In much of the world introduction of the true arch was a result of European influence.[2] The term false arch has few meanings. It is usually used to designate an arch that has no structural purpose, like a proscenium arch in theaters used to frame the performance for the spectators, but is also applied to corbelled and triangular arches that are not based on compression.[8][9]

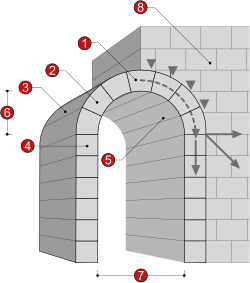

A typical true masonry arch consists of the following elements:[10][11][12]

- Keystone, the top block in an arch. Portion of the arch around the keystone (including the keystone itself), with no precisely defined boundary, is called a crown

- Voussoir (a wedge-like construction block). A compound arch is formed by multiple concentric layers of voussoirs. The rowlock arch is a particular case of the compound arch,[13] where the voussoir faces are formed by the brick headers.[14]

- Extrados (an external surface of the arch)

- Impost is block at the base of the arch (the voussoir immediately above the impost is a springer). The tops of imposts define the springing level. A portion of the arch between the springing level and the crown (centered around the 45° angle[15]) is called a haunch. If the arch resides on top of a column, the impost is formed by an abacus or its thicker version, dosseret.[16]

- Intrados (an underside of the arch, also known as a soffit[7])

- Rise (height of the arc, distance from the springing level to the crown)

- Clear span

- Abutment[17] The roughly triangular-shaped portion of the wall between the extrados and the horizontal division above is called spandrel.[18]

A (left or right) half-segment of an arch is called an arc, the overall line of an arch is arcature[19] (this term is also used for an arcade).[20] Archivolt is the exposed (front-facing) part of the arch, sometimes decorated (occasionally also used to designate the intrados).[21] If the sides of voussoir blocks are not straight, but include angles and curves for interlocking, the arch is called "joggled".[22]

Arch action

[edit]

A true arch, due to its rise, resolves the vertical loads into horizontal and vertical reactions at the ends, a so called arch action. The vertical load produces a positive bending moment in the arch, while the inward-directed horizontal reaction from the spandrel/abutment provides a counterbalancing negative moment. As a result, the bending moment in any segment of the arch is much smaller than in a beam with the equivalent load and span.[23] The diagram on the right shows the difference between a loaded arch and a beam. Elements of the arch are mostly subject to compression (A), while in the beam a bending moment is present, with compression at the top and tension at the bottom (B).

In the past, when arches were made of masonry pieces, the horizontal forces at the ends of an arch (so called thrust[24]) caused the need for heavy abutments (cf. Roman triumphal arch). The other way to counteract the forces, and thus allow thinner supports, was to use the counter-arches, as in an arcade arrangement, where the horizontal thrust of each arch is counterbalanced by its neighbors, and only the end arches need to buttressed. With new construction materials (steel, concrete, engineered wood), not only the arches themselves got lighter, but the horizontal thrust can be further relieved by a tie connecting the ends of an arch (bowstring arch).[6]

Funicular shapes

[edit]When evaluated from the perspective of an amount of material required to support a given load, the best solid structures are compression-only; with the flexible materials, the same is true for tension-only designs. There is a fundamental symmetry in nature between solid compression-only and flexible tension-only arrangements, noticed by Robert Hooke in 1676: "As hangs the flexible line, so but inverted will stand the rigid arch", thus the study (and terminology) of arch shapes is inextricably linked to the study of hanging chains, the corresponding curves or polygons are called funicular. Just like the shape of a hanging chain will vary depending on the weights attached to it, the shape of an ideal (compression-only) arch will depend on the distribution of the load.[25]

-

Analogy between an arch and a hanging chain and comparison to the dome of Saint Peter's Basilica in Rome (Giovanni Poleni, 1748)

-

A complex funicular model (Church of Colònia Güell by Gaudi, 19th century)

While building masonry arches in the not very tall buildings of the past, a practical assumption was that the stones can withstand virtually unlimited amount of pressure (up to 100 N per mm2), while the tensile strength was very low, even with the mortar added between the stones, and can be effectively assumed to be zero. Under these assumptions the calculations for the arch design are greatly simplified: either a reduced-scale model can be built and tested, or a funicular curve (pressure polygon) can be calculated or modeled, and as long as this curve stays within the confines of the voussoirs, the construction will be stable[26] (a so called "safe theorem").

Classifications

[edit]There are multiple ways to classify arches:[27]

- by the geometrical shape of its intrados (for example, semicircular, triangular, etc.);[27][28]

- for the arches with rounded intrados, by the number of circle segments forming the arch (for example, round arch is single-centred, pointed arch is two-centred);[27]

- by the material used (stone, brick, concrete, steel) and construction approach.[27] For example, the wedge-shaped voussoirs of a brick arch can be made by cutting the regular bricks ("axed brick" arch) or manufactured in the wedge shape ("gauged brick" arch);[29]

- structurally, by the number of hinges (movable joints) between solid components. For example, voussoirs in a stone arch should not move, so these arches usually have no hinges (are "fixed"). Permitting some movement in a large structure allows to alleviate stresses (caused, for example, by the thermal expansion), so many bridge spans are built with three hinges (one at each support and one at the crown) since the mid-19th century.[30]

Arrangements

[edit]A sequence of arches can be grouped together forming an arcade. Romans perfected this form, as shown, for example, by arched structures of Pont du Gard.[31] In the interior of hall churches, arcades of separating arches were used to separate the nave of a church from the side aisle,[32] or two adjacent side aisles.[33]

Two-tiered arches, with two arches superimposed, were sometimes used in Islamic architecture, mostly for decorative purposes.[34]

An opening of the arch can be filled, creating a blind arch. Blind arches are frequently decorative, and were extensively used in Early Christian, Romanesque, and Islamic architecture.[35] Alternatively, the opening can be filled with smaller arches, producing a containing arch, common in Gothic and Romanesque architecture.[36] Multiple arches can be superimposed with an offset, creating an interlaced series of usually (with some exceptions) blind and decorative arches. Most likely of Islamic origin, the interlaced arcades were popular in Romanesque and Gothic architecture.[37] Rear-arch (also rere-arch) is the one that frames the internal side of an opening in the external wall.[38]

-

Arcades of Pont du Gard (Roman)

-

Separating arches in the St. Zeno church

-

Two-tiered arches in the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba (Islamic)

-

Large blind arch containing three smaller blind arches

-

Interlaced arcade of blind arches at Castle Acre (Romanesque)

-

Rear arch around three lights at St Matthew's Church, Langford

Structural

[edit]Structurally, relieving arches (often blind or containing) can be used to take off load from some portions of the building (for example, to allow use of thinner exterior walls with larger window openings, or, as in the Roman Pantheon, to redirect the weight of the upper structures to particular strong points).[36] Transverse arches, introduced in Carolingian architecture, are placed across the nave to compartmentalize (together with longitudinal separating arches) the internal space into bays and support vaults.[39] A diaphragm arch similarly goes in the transverse direction, but carries a section of wall on top. It is used to support or divide sections of the high roof.[40] Strainer arches were built as an afterthought to prevent two adjacent supports from imploding due to miscalculation. Frequently they were made very decorative, with one of the best examples provided by the Wells Cathedral. Strainer arches can be "inverted" (upside-down) while remaining structural.[41][42] When used across railway cuttings to prevent collapse of the walls, strainer arches may be referred to as flying arches.[43][44] A counter-arch is built adjacent to another arch to oppose its horizontal action or help to stabilize it, for example, when constructing a flying buttress.[45]

-

Relieving blind arches made of bricks at the Roman Pantheon

-

Transverse arches in Speyer Cathedral

-

Diaphragm arch in San Miniato al Monte

-

"Scissors" strainer arch arrangement in Wells Cathedral includes an inverted arch

Shapes

[edit]

The large variety of arch shapes (left) can mostly be classified into three broad categories: rounded, pointed, and parabolic.[46]

Rounded

[edit]"Round" semicircular arches were commonly used for ancient arches that were constructed of heavy masonry,[47] and were relied heavily on by the Roman builders since the 4th century BC. It is considered to be the most common arch form,[48] characteristic for Roman, Romanesque, and Renaissance architecture.[28]

A segmental arch, with a rounded shape that is less than a semicircle, is very old (the versions were cut in the rock in Ancient Egypt c. 2100 BC at Beni Hasan). Since then it was occasionally used in Greek temples,[49] utilized in Roman residential construction,[50] Islamic architecture, and got popular as window pediments during the Renaissance.[49]

A basket-handle arch (also known as depressed arch, three-centred arch, basket arch) consists of segments of three circles with origins at three different centers (sometimes uses five or seven segments, so can also be five-centred, etc.). Was used in late Gothic and Baroque architecture.[51][52]

A horseshoe arch (also known as keyhole arch) has a rounded shape that includes more than a semicircle, is associated with Islamic architecture and was known in areas of Europe with Islamic influence (Spain, Southern France, Italy). Occasionally used in Gothics, it briefly enjoyed popularity as the entrance door treatment in the interwar England.[53]

-

Segmental arch of the Alconétar Bridge

-

Bridge with a basket handle arch

Pointed

[edit]

A pointed arch consists of two ("two-centred arch"[54]) or more circle segments culminating in a point at the top. It originated in the Islamic architecture (there are other opinions, cf. Warren 1991[55]), arrived in Europe in the second half of the 11th century (Cluny Abbey)[56] and later became prominent in the Gothic architecture.[57] The advantages of a pointed arch over a semicircular one are flexible ratio of span to rise[58] and lower horizontal reaction at the base. This innovation allowed for taller and more closely spaced openings, which are typical of Gothic architecture.[59][60] Equilateral arch is the most common form of the pointed arch, with the centers of two circles forming the intrados coinciding with the springing points of the opposite segment. Together with the apex point, they form an equilateral triangle, thus the name.[61] If the centers of circles are farther apart, the arch becomes a narrower and sharper lancet arch that appeared in France in the Early Gothic architecture (Saint-Denis Abbey) and became prominent in England in the late 12th and early 13th centuries (Salisbury Cathedral).[62] If the centers are closer to another, the result is a wider blunt arch.

The intrados of the cusped arch (also known as multifoil arch, polyfoil arch, polylobed arch, and scalloped arch) includes several independent circle segments in a scalloped arrangement. These primarily decorative arches are common in Islamic architecture and Northern European Late Gothic, can be found in Romanesque architecture.[63] A similar trefoil arch includes only three segments and sometimes has a rounded, not pointed, top. Common in Islamic architecture and Romanesque buildings influenced by it, it later became popular in the decorative motifs of the Late Gothic designs of Northern Europe.[64]

Each arc of an ogee arch consists of at least two circle segments (for a total of at least four), with the center of an upper circle being outside the extrados. After European appearance in the 13th century on the facade of the St Mark's Basilica, the arch became a fixture of the English Decorated style, French Flamboyant, Venetian, and other Late Gothic styles.[65] Ogee arch is also known as reversed curve arch, occasionally also called an inverted arch.[41] The top of an ogee arch sometimes projects beyond the wall, forming the so-called nodding ogee popular in 14th century England (pulpitum in Southwell Minster).[66]

Each arc of a four-centred arch is made of two circle segments with distinct centers; usually the radius used closer to the springing point is smaller with a more pronounced curvature. Common in Islamic architecture (Persian arch), and, with upper portion flattened almost to straight lines (Tudor arch[67]), in the English Perpendicular Gothic.[68]A keel arch is a variant of four-centred arch with haunches almost straight, resembling a section view of a capsized ship. Popular in Islamic architecture, it can be also found in Europe, occasionally with a small ogee element at the top,[69] so it is sometimes considered to be a variation of an ogee arch.[70]

Curtain arch (also known as inflexed arch, and, like the keel arch, usually decorative[28]) uses two (or more) drooping curves that join at the apex. Utilized as a dressing for windows and doors primarily in Saxony in the Late Gothic and early Renaissance buildings (late 15th to early 16th century), associated with Arnold von Westfalen.[71] When the intrados has multiple concave segments, the arch is also called a draped arch or tented arch.[72] A similar arch that uses a mixture of curved and straight segments[73] or exhibits sharp turns between segments[74] is a mixed-line arch (or mixtilinear arch). In Moorish architecture the mixed-line arch evolved into an ornate lambrequin arch,[75] also known as muqarnas arch.

-

Pointed arches of Mosque of Ibn Tulun (9th century AD)

-

Cusped arch in Diwan-i-Khas (Red Fort)

-

Trefoil arch in the Bayeux Cathedral

-

Tudor arch at Layer Marney Tower

-

Ogee arch at St Mary the Virgin, Silchester

-

Nodding ogee niche at St Peter's Church, Walpole St Peter

-

Keel arches at Palazzo Guadagni

-

Curtain arches over windows in Hartenfels Castle

-

A draped arch at the Government Palace of Tlaxcala (1545)

-

Mixed-line arches at Escuelas Menores (Salamanca)

-

Lambrequin arch at Bahia Palace in Morocco

Parabolic

[edit]The popularity of the arches using segments of a circle is due to simplicity of layout and construction,[76] not their structural properties. Consequently, the architects historically used a variety of other curves in their designs: elliptical curves, hyperbolic cosine curves (including catenary), and parabolic curves. There are two reasons behind the selection of these curves:[77]

- they are still relatively easy to trace with common tools prior to construction;

- depending on a situation, they can have superior structural properties and/or appearance.

The hyperbolic curve is not easy to trace, but there are known cases of its use.[77] The non-circumferential curves look similar, and match at shallow profiles, so a catenary is often misclassified as a parabola[78] (per Galileo, "the [hanging] chain fits its parabola almost perfectly"[79]). González et al. provide an example of Palau Güell, where researchers do not agree on classification of the arches or claim the prominence of parabolic arches, while the measurements show that just two of the 23 arches designed by Gaudi are actually parabolic.[80]

Three parabolic-looking curves in particular are of significance to the arch design: parabola itself, catenary, and weighted catenary. The arches naturally use the inverted (upside-down) versions of these curves.

A parabola represents an ideal (all-compression) shape when the load is equally distributed along the span, while the weight of the arch itself is negligible. A catenary is the best solution for the case where an arch with uniform thickness carries just its own weight with no external load. The practical designs for bridges are somewhere in between, and thus use the curves that represent a compromise that combines both the catenary and the funicular curve for particular non-uniform distribution of load.[85] The practical free-standing arches are stronger and thus heavier at the bottom, so a weighted catenary curve is utilized for them. The same curve also fits well an application where a bridge consists of an arch with a roadway of packed dirt above it, as the dead load increases with a distance from the center.[86]

-

A through arch bridge (Tyne Bridge in Newcastle upon Tyne, England): parabolic-looking arches with multiple deck supports distributing the load

-

Gateway Arch is stronger at the bottom: weighted catenary curve

Other

[edit]Unlike regular arches, the flat arch (also known as jack arch, lintel arch, straight arch, plate-bande[87]) is not curved. Instead, the arch is flat in profile and can be used under the same circumstances as lintel. However, lintels are subject to bending stress, while the flat arches are true arches, composed of irregular voussoir shapes (the keystone is the only one of the symmetric wedge shape),[88] and that efficiently uses the compressive strength of the masonry in the same manner as a curved arch and thus requires a mass of masonry on both sides to absorb the considerable lateral thrust. Used in the Roman architecture to imitate the Greek lintels, Islamic architecture, European medieval and Renaissance architecture. The flat arch is still being used as a decorative pattern, primarily at the top of window openings.[88]

False arches

[edit]The corbel (also corbelled) arch, made of two corbels meeting in the middle of the span, is a true arch in a sense of being able to carry a load, but it is false in a structural sense, as its components are subject to bending stress. The typical profile is not curved, but has triangular shape. Invented prior to the semicircular arch, the corbel arch was used already in the Egyptian and Mycenaean architecture in the 3rd and 2nd millennium BC.[89]

Like a corbel arch, the triangular arch is not a true arch in a structural sense. Its intrados is formed by two slabs leaning against each other.[9] Brick builders would call triangular any arch with straight inclined sides.[90] The design was common in Anglo-Saxon England until the late 11th century (St Mary Goslany).[9] Mayan corbel arches are sometimes called triangular due to their shape.[91]

-

Flat arch in the kitchen of Pitti Palace

-

Triangular arch

-

A triangular arch built using masonry

-

Mayan corbelled arch

Variations

[edit]Few transformations can be applied to arch shapes.

If one impost is much higher than another, the arch (frequently pointed) is known as ramping arch, raking arch,[92] or rampant arch (from French: arc rampant).[93] Originally used to support inclined structures, like stairs, in the 13th-14th centuries they appeared as parts of flying buttresses used to counteract the thrust of Gothic ribbed vaults.[94]

A central part of an arch can be raised on short vertical supports, creating a trefoil-like shouldered arch. The raised central part can vary all the way from a flat arch to ogee. The shouldered arches were used to decorate openings in Europe from medieval times to Late Gothic architecture, became common in Iranian architecture from the 14th century, and were later adopted in the Ottoman Turkey.[95]

In a stilted arch (also surmounted[96]), the springing line is located above the imposts (on "stilts"). Known to Islamic architects by the 8th century, the technique was utilized to vertically align the apexes of arches of different dimensions in Romanesque and Gothic architecture.[97] Stilting was useful for semicircular arches, where the ratio of the rise fixed at 1⁄2 of the span, but was applied to the pointed arches, too.

The skew arch (also known as an oblique arch) is used when the arch needs to form an oblique angle in the horizontal plane with respect to the (parallel) springings,[98][99] for example, when a bridge crosses the river at an angle different than 90°. A splayed arch is used for the case of unequal spans on the sides of the arch (when, for example, an interior opening in the wall is larger than the exterior one), the intrados of a round splayed arch is not cylindrical, but has a conical shape.[100][99]

-

Ramping arches at Palau Dalmases in Barcelona

-

Shouldered arch around the door of Lorenziberg church. The raised portion is a flat arch.

-

Shouldered arch above the main entrance of Doge's Palace in Venice. The vertical supports separate the segments of an ogee arch.

-

The smaller arches at the lower level are stilted to match the wider arches on the left (St John's Chapel, London)

-

Stilted pointed arches at the Monreale Cathedral)

-

Skew arch (Sickergill Bridge) with helicoidal masonry courses

-

Splayed arch over a window opening in the All Saints Church in Chedgrave

A wide arch with its rise less than 1⁄2 of the span (and thus the geometric circle of at least one segment is below the springing line) is called a surbased arch[101] (sometimes also a depressed arch[102]). A drop arch is either a basket handle arch[103] or a blunt arch.[104]

Hinged arches

[edit]

Practical arch bridges are built either as a fixed arch, a two-hinged arch, or a three-hinged arch.[105] The fixed arch is most often used in reinforced concrete bridges and tunnels, which have short spans. Because it is subject to additional internal stress from thermal expansion and contraction, this kind of arch is statically indeterminate (the internal state is impossible to determine based on the external forces alone).[46]

The two-hinged arch is most often used to bridge long spans.[46] This kind of arch has pinned connections at its base. Unlike that of the fixed arch, the pinned base can rotate,[106] thus allowing the structure to move freely and compensate for the thermal expansion and contraction that changes in outdoor temperature cause. However, this can result in additional stresses, and therefore the two-hinged arch is also statically indeterminate, although not as much as the fixed arch.[46]

The three-hinged arch is not only hinged at its base, like the two-hinged arch, yet also at its apex. The additional apical connection allows the three-hinged arch to move in two opposite directions and compensate for any expansion and contraction. This kind of arch is thus not subject to additional stress from thermal change. Unlike the other two kinds of arch, the three-hinged arch is therefore statically determinate.[105] It is most often used for spans of medial length, such as those of roofs of large buildings. Another advantage of the three-hinged arch is that the reaction of the pinned bases is more predictable than the one for the fixed arch, allowing shallow, bearing-type foundations in spans of medial length. In the three-hinged arch "thermal expansion and contraction of the arch will cause vertical movements at the peak pin joint but will have no appreciable effect on the bases," which further simplifies foundational design.[46]

History

[edit]The arch became popular in the Roman times and mostly spread alongside the European influence, although it was known and occasionally used much earlier. Many ancient architectures avoided the use of arches, including the Viking and Hindu ones.[2]

Bronze Age: ancient Near East

[edit]True arches, as opposed to corbel arches, were known by a number of civilizations in the ancient Near East including the Levant, but their use was infrequent and mostly confined to underground structures, such as drains where the problem of lateral thrust is greatly diminished.[107] An example of the latter would be the Nippur arch, built before 3800 BC,[108] and dated by H. V. Hilprecht (1859–1925) to even before 4000 BC.[109] Rare exceptions are an arched mudbrick home doorway dated to c. 2000 BC from Tell Taya in Iraq[110] and two Bronze Age arched Canaanite city gates, one at Ashkelon (dated to c. 1850 BC),[111] and one at Tel Dan (dated to c. 1750 BC), both in modern-day Israel.[112][113] An Elamite tomb dated 1500 BC from Haft Teppe contains a parabolic vault which is considered one of the earliest evidences of arches in Iran.

The use of true arches in Egypt also originated in the 4th millennium BC (underground barrel vaults at the Dendera cemetery). Standing arches were known since at least the Third Dynasty, but very few examples survived, since the arches were mostly used in non-durable secular buildings and made of mud brick voussoirs that were not wedge-shaped, but simply held in place by mortar, and thus susceptible to a collapse (the oldest arch still standing is at Ramesseum). Sacred buildings exhibited either lintel design or corbelled arches. Arches were mostly missing in Egypt temples even after the Roman conquest, even though Egyptians thought of the arch as a spiritual shape and used it in the rock-cut tombs and portable shrines.[114] Auguste Mariette suggested that this choice was based on a relative fragility of a vault: "what would remain of the tombs and temples of Egyptians today, if they had preferred the vault?"[28]

Mycenaean architecture utilized only the corbel arches in their beehive tombs with triangular openings.[114] Mycenaeans had also built probably the oldest still standing[citation needed] stone-arch bridge in the world, Arkadiko Bridge, in Greece.

As evidenced by their imitations of the parabolic arches, Hittites most likely were exposed to the Egyptian designs, but used the corbelled technique to build them.[114]

-

Vaulted building using a decorative segmented arch at the Heb-sed court in Saqqara (restored, c. 2650 BC)

-

A true arch (catenary) at the Ramesseum granaries (c. 1300 BC)

-

Ruins of the Kazarma tholos tomb (c.1500 BC) showing the Mycenaean beehive technique

-

Arkadiko Bridge (c. 1300-1190 BC): corbel arch, cyclopean masonry

-

King's Gate (Hattusa) (c.1400-1200 BC), an imitation of the parabolic arch by Hittites

Classical Persia and Greece

[edit]The Assyrians, also apparently under the Egyptian influence, adopted the true arch (with a slightly pointed profile) early in the 8th century.[114] In ancient Persia, the Achaemenid Empire (550 BC–330 BC) built small barrel vaults (essentially a series of arches built together to form a hall) known as iwan, which became massive, monumental structures during the later Parthian Empire (247 BC–AD 224).[115][116][117] This architectural tradition was continued by the Sasanian Empire (224–651), which built the Taq Kasra at Ctesiphon in the 6th century AD, the largest free-standing vault until modern times.[118]

An early European example of a voussoir arch appears in the 4th century BC Greek Rhodes Footbridge.[119][120] Proto-true arches can also be found under the stairs of the temple of Apollo at Didyma and the stadium at Olympia.[31] .

-

Arch at the excavation in Dur-Sharrukin (Assyrian architecture, end of 8th century BC, photo taken in 1853)

-

Arch at the stadium of Olympia (4th century BC)

Ancient Rome

[edit]The ancient Romans learned the semicircular arch from the Etruscans (both cultures apparently adopted the design in the 4th century BC[31]), refined it and were the first builders in Europe to tap its full potential for above ground buildings:

The Romans were the first builders in Europe, perhaps the first in the world, to fully appreciate the advantages of the arch, the vault and the dome.[121]

Throughout the Roman Empire, from Syria to Scotland, engineers erected arch structures. The first use of arches was for civic structures, like drains and city gates. Later the arches were utilized for major civic buildings bridges and aqueducts, with the outstanding 1st century AD examples provided by the Colosseum, Pont Du Gard, and the aqueduct of Segovia.[31] The introduction of the ceremonial triumphal arch dates back to Roman Republic, although the best examples are from the imperial times (Arch of Augustus at Susa, Arch of Titus).[31]

Romans initially avoided using the arch in the religious buildings and, in Rome, arched temples were quite rare until the recognition of Christianity in 313 AD (with the exceptions provided by the Pantheon and the "temple of Minerva Medica"[verification needed]). Away from the capital, arched temples were more common (temple of Hadrian at Ephesus, temple of Jupiter at Sbeitla, Severan temple at Djemila).[31] Arrival of Christianity prompted creation of the new type of temple, a Christian basilica, that made a thorough break with the pagan tradition with arches as one of the main elements of the design, along with the exposed brick walls (Santa Sabina in Rome, Sant'Apollinare in Classe). For a long period, from the late 5th century to the 20th century, arcades were a standard staple for the Western Christian architecture.[31]

Vaults began to be used for roofing large interior spaces such as halls and temples, a function that was also assumed by domed structures from the 1st century BC onwards.

The segmental arch was first built by the Romans who realized that an arch in a bridge did not have to be a semicircle,[122][123] such as in Alconétar Bridge or Ponte San Lorenzo. The utilitarian and mass residential (insulae) buildings, as found in Ostia Antica and Pompeii, mostly used low segmental arches made of bricks and architraves made of wood, while the concrete lintel arches can be found in villas and palaces.[50]

-

The Jupiter gate at Falerii Novi (c. 300 BC)

-

Arches of the aqueduct at Segovia

-

Arches of the Colosseum

-

Arch of Augustus, Susa, Piedmont (c. 8 BC)

-

Arches at the "temple of Minerva Medica" in Rome

-

Temple of Hadrian at Ephesus combines a semicircular arch with the lintels (117 AD)

-

Temple of Jupiter at Sbeitla (c. 150 AD)

-

Arches in the narthex of Santa Sabina, Rome (c. 425 AD)

-

Arches and dome in Sant'Apollinare in Classe (534-536 AD)

-

Segmental arches in an Ostian insula

Ancient China

[edit]Ancient architecture of China (and Japan) used mostly timber-framed construction and trabeated system.[5] Arches were little-used, although there are few arch bridges known from literature and one artistic depiction in stone-carved relief.[124][125][126] Since the only surviving artefacts of architecture from the Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) are rammed earth defensive walls and towers, ceramic roof tiles from no longer existent wooden buildings,[127][128][129] stone gate towers,[130][131] and underground brick tombs, the known vaults, domes, and archways were built with the support of the earth and were not free-standing.[132][133]

China's oldest surviving stone arch bridge is the Anji Bridge. Still in use, it was built between 595 CE and 605 CE during the Sui dynasty.[134][135]

-

Anji Bridge: segmental arch, open-spandrel design

Islamic

[edit]Islamic architects adopted the Roman arches, but had quickly shown their resourcefulness: by the 8th century the simple semicircular arch was almost entirely replaced with fancier shapes, few fine examples of the former in the Umayyad architecture notwithstanding (cf. the Great Mosque of Damascus, 706–715 CE). The first pointed arches appear already at the end of the 7th century AD (Al-Aqsa Mosque, Palace of Ukhaidhir, cisterns at the White Mosque of Ramle[136][137]). Their variations spread fast and wide: Mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo (876-879 AD), Nizamiyya Madrasa at Khar Gerd (now Iran, 11th century), Kongo Mosque in Diani Beach (Kenya, 16th century).[74][137]

Islamic architecture brought to life a large amount of arch forms: the round horseshoe arch that became a characteristic trait of the Islamic buildings, the keel arch, the cusped arch, and the mixed-line arch (where the curved "ogee swell" is interspersed with abrupt bends).[137] The Great Mosque of Cordoba, that can be considered a catalogue of Islamic arches, contains also the arches with almost straight sides, trefoil, interlaced, and joggled. Mosque of Ibn Tulun adds four-centred and stilted version of the pointed arch.[74]

It is quite likely that the appearance of the pointed arch, an essential element of the Gothic style, in Europe (Monte Cassino, 1066–1071 AD, and the Cluny Abbey five years later) and the ogee arch in Venice (c. 1250) is a result of the Islamic influence,[74] possibly through Sicily.[138] Saoud[139] also credits to Islamic architects the spread of the transverse arch. Mixed-line arch became popular in the Mudéjar style and subsequently spread around the Spanish-speaking world.[73]

-

Semicircular arches at the Umayyad mosque

-

Pointed arches in the cisterns of the White Mosque in Ramla

-

Trefoil arches at the Cordoba Mosque

-

Interlaced arches at the Cordoba Mosque

-

Horseshoe arches at the Cordoba Mosque

-

Ogee arch at the Cordoba Mosque

-

Cusped arhes at the Cordoba Mosque

-

Mixed line arches at Palacio de Torre Tagle, Lima, Peru (1735)

Western Europe

[edit]The collapse of the Western Roman Empire left the church as the only client of major construction; with all pre-Romanesque architectural styles borrowing from Roman construction with its semicircular arch. Due to the decline in the construction quality, the walls were thicker, and the arches thus heavier, than their Roman prototypes. Eventually the architects started to use the depth of the arches for decoration, turning the deep opening into recessed orders (or rebated arch, a sequence of progressively smaller concentric arches, each inset with a rebate).[140]

Romanesque style started experiments with the pointed arch late in the 11th century (Cluny Abbey). In few decades, the practice spread (Durham Cathedral, Basilica of Saint-Denis). Early Gothic utilized the flexibility of the pointed arch by grouping together arches of different spans but with the same height.[140]

While the arches used in the mediaeval Europe were borrowed from the Roman and Islamic architecture, the use of pointed arch to form the rib vault was novel and became the defining characteristic of Gothic construction. At about 1400 AD, the city-states of Italy, where the pointed arch had never gotten much traction, initiated the revival of the Roman style with its round arches, Renaissance. By the 16th century the new style spread across Europe and, through the influence of empires, to the rest of the world. Arch became a dominant architectural form until the introduction of the new construction materials, like steel and concrete.[140]

India

[edit]The history of arch in India is very long (some arches were apparently found in excavations of Kosambi, 2nd millennium BC. However, the continuous history begins with rock-cut arches in the Lomas Rishi cave (3rd century BC).[74] Vaulted roof of an early Harappan burial chamber has been noted at Rakhigarhi.[141] S.R Rao reports vaulted roof of a small chamber in a house from Lothal.[142] Barrel vaults were also used in the Late Harappan Cemetery H culture dated 1900 BC-1300 BC which formed the roof of the metal working furnace, the discovery was made by Vats in 1940 during excavation at Harappa.[143][144][145]

The use of arches until the Islamic conquest of India in the 12th century AD was sporadic, with ogee arches and barrel vaults in rock-cut temples (Karla Caves, from the 1st century BC) and decorative pointed gavaksha arches. By the 5th century AD voussoir vaults were used structurally in the brick construction. Surviving examples include the temple at Bhitargaon (5th century AD) and Mahabodhi Temple (7th century AD), the latter has both pointed arches and semicircular arches.[74][146] These Gupta era arch vault system was later used extensively in Burmese Buddhist temples in Pyu and Bagan in 11th and 12th centuries.[147]

With the arrival of Islamic and other Western Asia influence, the arches became prominent in the Indian architecture, although the post and lintel construction was still preferred. A variety of pointed and lobed arches was characteristic for the Indo-Islamic architecture, with the monumental example of Buland Darwaza, that has pointed arch decorated with small cusped arches.[74]

-

The insides of the Lomas Rishi cave

-

Arches at Karle (Great Chaitya, 1st century AD)

-

Decorative ogee arches (gavaksha) in Ajanta Caves

-

Pointed vault at the Mahabodhi temple

-

Arches at Buland Darwaza (16th century AD)

Pre-Columbian America

[edit]Mayan architecture utilized the corbel arches. The other Mesoamerican cultures used only the flat roofs with no arches whatsoever,[148] although some researchers had suggested that both Maya and Aztec architects understood the concept of a true arch.[149][150]

Revival of the trabeated system

[edit]The 19th-century introduction of the wrought iron (and later steel) into construction changed the role of the arch. Due to the high tensile strength of new materials, relatively long lintels became possible, as was demonstrated by the tubular Britannia Bridge (Robert Stephenson, 1846-1850). A fervent proponent of the trabeated system, Alexander "Greek" Thomson, whose preference for lintels was originally based on aesthetic criteria, observed that the spans of this bridge are longer than that of any arch ever built, thus "the simple, unsophisticated stone lintel contains in its structure all the scientific appliances [...] used in the great tubular bridge. [...] Stonehenge is more scientifically constructed than York Minster."[151] Use of arches in bridge construction continued (the Britannia Bridge was rebuilt in 1972 as a truss arch bridge), yet the steel frames and reinforced concrete frames mostly replaced the arches as the load-bearing elements in buildings.

-

Original Britannia bridge (a colored postcard)

-

Britannia bridge (2008)

Construction

[edit]

As a pure compression form, the utility of the arch is due to many building materials, including stone and unreinforced concrete, being strong under compression, but brittle when tensile stress is applied to them.[152]

Masonry

[edit]The voussoirs can be wedge-shaped or have a form of a rectangular cuboid, in the latter case the wedge-like shape is provided by the mortar.[94]

An arch is held in place by the weight of all of its members, making construction problematic. One answer is to build a frame (historically, of wood) which exactly follows the form of the underside of the arch. This is known as a centre or centring. Voussoirs are laid on it until the arch is complete and self-supporting. For an arch higher than head height, scaffolding would be required, so it could be combined with the arch support. Arches may fall when the frame is removed if design or construction has been faulty.[citation needed]

Old arches sometimes need reinforcement due to decay of the keystones, forming what is known as bald arch.

Reinforced concrete

[edit]In reinforced concrete construction, the principle of the arch is used so as to benefit from the concrete's strength in resisting compressive stress. Where any other form of stress is raised, such as tensile or torsional stress, it has to be resisted by carefully placed reinforcement rods or fibres.[153]

Architectural styles

[edit]The type of arches (or absence of them) is one of the most prominent characteristics of an architectural style. For example, when Heinrich Hübsch, in the 19th century, tried to classify the architectural style, his "primary elements" were roof and supports, with the top-level basic types: trabeated (no arches) and arcuated (arch-based). His next division for the arcuated styles was based on the use of round and pointed arch shapes.[154]

Cultural references

[edit]The steady horizontal push of an arch against the abutments gave rise to a saying "the arch never sleeps", attributed to many sources, from Hindu[155] to Arabs.[28] This adage stresses that the arch carries "a seed of death" for itself and the structure containing it, a statement that can be made upon observation of the Roman ruins.[28] The plot of The Nebuly Coat by J. Meade Falkner, inspired by a collapse of a tower at the Chichester Cathedral plays with the idea while dealing with the slow disintegration of a church building.[155] Saoud[156] explains the proverb by chain-like self-balancing of the horizontal and vertical forces in the arch and its "universal adaptability".[157]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Gorse, Johnston & Pritchard 2020, arch.

- ^ a b c Woodman & Bloom 2003, History.

- ^ Gorse, Johnston & Pritchard 2020, arch dam.

- ^ Clarke & Clarke 2010, vault.

- ^ a b Lyttleton 2003.

- ^ a b Arch at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ a b Woodman & Bloom 2003.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, False.

- ^ a b c Woodman & Bloom 2003, Triangular.

- ^ Boyd 1978, p. 90.

- ^ Wilkins 1879, pp. 291–293.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Structure.

- ^ "rowlock arch". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ American Technical Society 1908, p. 111.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Haunch.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Dosseret.

- ^ Beall 1987, p. 301.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Intrados.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Arc.

- ^ "arcature". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Archivolt.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Joggled.

- ^ Au 1960, p. 169.

- ^ Calvo-López 2020, p. 8.

- ^ Allen, Ochsendorf & West 2016, p. 40.

- ^ Calvo-López 2020, pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b c d Punmia, Jain & Jain 2005, p. 425.

- ^ a b c d e f Arco entry (in Italian) in the Enciclopedia Treccani, 1929

- ^ Punmia, Jain & Jain 2005, pp. 431–432.

- ^ Slivnik 2013, p. 1089.

- ^ a b c d e f g Woodman & Bloom 2003, Ancient Greece and Rome.

- ^ Günther Wasmuth (ed.): Wasmuths Lexikon der Baukunst, vol. 4: P - Zyp. Wasmuth, Berlin 1932, p. 293.

- ^ Wilfried Koch: Baustilkunde - Europäische Baukunst von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart. Sonderausgabe, Orbis Verlag, München 1988, ISBN 3-572-05927-5, p. 447.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Two-tiered.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Blind.

- ^ a b Woodman & Bloom 2003, Containing.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Interlace.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Rear-arch [rere-arch].

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Transverse.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Diaphragm.

- ^ a b Woodman & Bloom 2003, Inverted.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Strainer.

- ^ "Rare Victorian Railway Arches Saved". historicengland.org.uk. Historic England. 18 August 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2024.

- ^ Historic England. "Series of 16 strainer arches in railway cutting at SD 581 192 (1072648)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 21 April 2024.

- ^ Curl 2006, p. 207, counter-arch.

- ^ a b c d e Ambrose, James (2012). Building Structures. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-470-54260-6.

- ^ Ambrose, James (2012). Building Structures. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-470-54260-6.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Round.

- ^ a b Woodman & Bloom 2003, Segmental.

- ^ a b DeLaine 1990, p. 417.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Basket.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Depressed.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Horseshoe.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Two-centred.

- ^ Warren 1991.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Pointed.

- ^ Crossley, Paul (2000). Gothic Architecture. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-300-08799-4 – via Google Books.

- ^ Bond 1905, p. 265.

- ^ Hadrovic, Ahmet (2009). Structural Systems in Architecture. On Demand Publishing. p. 289. ISBN 978-1-4392-5944-3.

- ^ MHHE. "Structural Systems in Architecture". MHHE.com. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Equilateral.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Lancet.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Cusped.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Trefoil.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Ogee.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Nodding.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Tudor.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Four-centred.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Keel.

- ^ Curl 2006, ogee arch p=37.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Curtain.

- ^ Davies & Jokiniemi 2012, p. 153.

- ^ a b Martinez Nespral 2023, p. 15.

- ^ a b c d e f g Woodman & Bloom 2003, Indian subcontinent and Islamic lands.

- ^ Barrucand, Marianne; Bednorz, Achim (1995). Architecture maure en Andalousie (in French). PML Éditions. p. 162.

- ^ Mark 1996, p. 387.

- ^ a b González, Samper & Herrera 2018, p. 185.

- ^ Bradley & Gohnert 2022.

- ^ Osserman 2010, p. 220.

- ^ González, Samper & Herrera 2018, pp. 174, 184.

- ^ González, Samper & Herrera 2018, p. 183, #14.

- ^ González, Samper & Herrera 2018, p. 182, #9.

- ^ González, Samper & Herrera 2018, p. 183, #18.

- ^ González, Samper & Herrera 2018, p. 183, #19.

- ^ Benaim 2019, p. 501.

- ^ Osserman 2010, p. 224.

- ^ Mahan, D.H. (1873). A Treatise on Civil Engineering. J. Wiley & Son. p. 247. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ a b Woodman & Bloom 2003, Flat.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Corbelled.

- ^ Brick Industry Association] (January 1995). Brick Masonry Arches: Introduction (PDF). Technical Notes on Brick Construction. Brick Industry Association. p. 2.

- ^ Sturgis & Davis 2013, p. 121, Triangular Arch.

- ^ Davies & Jokiniemi 2008, p. 305.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Ramping.

- ^ a b arco entry (in Italian) by C. Ewert in the Enciclopedia Treccani, 1991

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Shouldered.

- ^ "surmounted arch". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Stilted.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Skew.

- ^ a b Calvo-López 2020, p. 265.

- ^ "splayed arch". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ "surbased". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Surbased.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Drop.

- ^ "drop arch". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ a b Reynolds, Charles E (2008). Reynolds's Reinforced Concrete Designer's Handbook. New York: Psychology Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-419-25820-9 – via Google Books.

- ^ Luebkeman, Chris H. "Support and Connection Types". MIT.edu Architectonics: The Science of Architecture. MIT.edu. Archived from the original on 28 October 2012. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ Rasch 1985, p. 117

- ^ John P. Peters, University of Pennsylvania Excavations at Nippur. II. The Nippur Arch, The American Journal of Archaeology and of the History of the Fine Arts, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 352–368, (Jul. – Sep., 1895)

- ^ New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, Vol. I: Babylonia: V. The People, Language, and Culture.: 7. The Civilization. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ Reade, J.E. (1 January 1968). "Tell Taya (1967): Summary Report". Iraq. 30 (2): 234–264. doi:10.2307/4199854. JSTOR 4199854. S2CID 162348582.

- ^ Lefkovits, Etgar (8 April 2008). "Oldest arched gate in the world restored". The Jerusalem Post. Jerusalem. Archived from the original on 14 August 2013. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ Israel Finkelstein; Amihay Mazar (2007). Brian B. Schmidt (ed.). The Quest for the Historical Israel: Debating Archaeology and the History of Early Israel. Society of Biblical Literature. pp. 177–. ISBN 978-1-58983-277-0.

- ^ Frances, Rosa: The three-arched middle Bronze Age gate at Tel Dan - A structural investigation of an extraordinary archaeological site, retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d Woodman & Bloom 2003, Ancient Egypt, the Near East and the eastern Mediterranean.

- ^ Brosius, Maria (2006), The Persians: An Introduction, London & New York: Routledge, p. 128, ISBN 0-415-32089-5.

- ^ Garthwaite, Gene Ralph (2005), The Persians, Oxford & Carlton: Blackwell Publishing, Ltd., p. 84, ISBN 1-55786-860-3.

- ^ Schlumberger, Daniel (1983), "Parthian Art", in Yarshater, Ehsan, Cambridge History of Iran, 3.2, London & New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 1049, ISBN 0-521-20092-X.

- ^ Wright, G. R. H., Ancient building technology vol. 3. Leiden, Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV. 2009. p. 237. Print.

- ^ Galliazzo 1995, p. 36.

- ^ Boyd 1978, p. 91.

- ^ Robertson, D.S. (1969). "Chapter Fifteen: Roman Construction. Arches, Vaults, and Domes". Greek and Roman Architecture (2nd ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 231. ISBN 0521061040. OCLC 1149316661. Retrieved 31 December 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Galliazzo 1995, pp. 429–437

- ^ O'Connor 1993, p. 171

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1986), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics, Taipei: Caves Books, pp. 161–188, ISBN 0-521-07060-0.

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1986), Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology; Part 2, Mechanical Engineering, Taipei: Caves Books, pp. 171–172 ISBN 0-521-05803-1.

- ^ Liu, Xujie (2002), "The Qin and Han dynasties", in Steinhardt, Nancy S., Chinese Architecture, New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 56, ISBN 0-300-09559-7.

- ^ Wang, Zhongshu (1982), Han Civilization, translated by K.C. Chang and Collaborators, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 1, 30, 39–40, ISBN 0-300-02723-0.

- ^ Chang, Chun-shu (2007), The Rise of the Chinese Empire: Volume II; Frontier, Immigration, & Empire in Han China, 130 B.C. – A.D. 157, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 91–92, ISBN 0-472-11534-0.

- ^ Morton, William Scott; Lewis, Charlton M. (2005), China: Its History and Culture (Fourth ed.), New York City: McGraw-Hill, p. 56, ISBN 0-07-141279-4.

- ^ Liu, Xujie (2002), "The Qin and Han dynasties", in Steinhardt, Nancy S., Chinese Architecture, New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 55, ISBN 0-300-09559-7.

- ^ Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman (2005), "Pleasure tower model", in Richard, Naomi Noble, Recarving China's Past: Art, Archaeology, and Architecture of the 'Wu Family Shrines, New Haven and London: Yale University Press and Princeton University Art Museum, pp. 279–280, ISBN 0-300-10797-8.

- ^ Wang, Zhongshu (1982), Han Civilization, translated by K.C. Chang and Collaborators, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 175–178, ISBN 0-300-02723-0.

- ^ Watson, William (2000), The Arts of China to AD 900, New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 108, ISBN 0-300-08284-3.

- ^ Knapp, Ronald G. (2008). Chinese Bridges: Living Architecture From China's Past. Singapore: Tuttle Publishing. pp. 122–127. ISBN 978-0-8048-3884-9.

- ^ Needham, Joseph. The Shorter Science and Civilisation in China. Cambridge University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-521-29286-7. pp. 145–147.

- ^ Saoud 2002, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Graves 2009.

- ^ Saoud 2002, p. 7.

- ^ Saoud 2002, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Woodman & Bloom 2003, Western Europe and its influence.

- ^ McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. p. 293. ISBN 978-1-57607-907-2.

- ^ Rao, Shikaripur Ranganatha; Rao, Calyampudi Radhakrishna (1973). Lothal and the Indus Civilization. Asia Publishing House. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-210-22278-2.

- ^ Tripathi, Vibha (27 February 2018). "METALS AND METALLURGY IN THE HARAPPAN CIVILIZATION" (PDF). Indian Journal of History of Science: 279–295.

- ^ Kenoyer, J.M; Dales, G. F. Summaries of Five Seasons of Research at Harappa (District Sahiwal, Punjab, Pakistan) 1986-1990. Prehistory Press. pp. 185–262.

- ^ Kenoyer, J.M.; Miller, Heather M..L. Metal Technologies of the Indus Valley Tradition in Pakistan and Western India (PDF). p. 124.

- ^ Chihara, Daigorō (1996). Hindu-Buddhist Architecture in Southeast Asia. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10512-6. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Le, Huu Phuoc (2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. ISBN 978-0-9844043-0-8. Archived from the original on 2 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Quirarte 1989, p. 47.

- ^ Befu, Harumi; Ekholm, Gordon F. (1964). "The True Arch in Pre-Columbian America?". Current Anthropology. 5 (4): 328–329. doi:10.1086/200506. ISSN 0011-3204. S2CID 145134147.

- ^ Schwerin, Karl H.; Ekholm, Gordon F. (1966). "On the Arch in Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica". Current Anthropology. 7 (1): 89–90. doi:10.1086/200668. ISSN 0011-3204. S2CID 144301211.

- ^ Stamp, Gavin (March 1998). ""At Once Classic and Picturesque...": Alexander Thomson's Holmwood". The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 57 (1): 46–58. doi:10.2307/991404. JSTOR 991404.

- ^ Reid, Esmond (1984). Understanding Buildings: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-262-68054-7. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016.

- ^ Allen, Edward (2009). Fundamentals of Building Construction. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. p. 529. ISBN 978-0-470-07468-8.

- ^ Mallgrave 1988, pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b Heyman 2015, p. 1.

- ^ Saoud 2002.

- ^ Royster 2021, p. 62.

Sources

[edit]- Allen, Edward; Ochsendorf, John; West, Mark (2016). "Structural Intelligence In Flexible Materials" (PDF). The Fabric Formwork Book. Routledge. pp. 39–47. ISBN 9781315675022.

- American Technical Society (1908). Cyclopedia of Architecture, Carpentry and Building. Vol. 1. American technical society. Retrieved 14 March 2025.

- Au, T. (1960). Elementary Structural Mechanics. Prentice-Hall civil engineering and engineering mechanics series. Prentice-Hall. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- Beall, C. (1987). Masonry Design and Detailing for Architects, Engineers, and Builders. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-004223-0. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

- Benaim, Robert (14 December 2019). "The Design and Construction of Arches" (PDF). The Design of Prestressed Concrete Bridges. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-367-86572-6. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017.

- Bond, Francis (1905). Gothic Architecture in England: An Analysis of the Origin & Development of English Church Architecture from the Norman Conquest to the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Collections spéciales. B. T. Batsford. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- Boyd, Thomas D. (1978), "The Arch and the Vault in Greek Architecture", American Journal of Archaeology, 82 (1): 83–100, doi:10.2307/503797, JSTOR 503797, S2CID 194040597

- Bradley, R.A.; Gohnert, M. (2 September 2022). "Parametric study of the catenary dome under gravity load". Current Perspectives and New Directions in Mechanics, Modelling and Design of Structural Systems. London: CRC Press. doi:10.1201/9781003348443-130. ISBN 978-1-003-34844-3.

- Calvo-López, José (2020). "Arches". Stereotomy. Mathematics and the Built Environment. Vol. 4. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 265–329. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-43218-8_6. ISBN 978-3-030-43217-1. S2CID 241431231.

- Clarke, Michael; Clarke, Deborah (1 January 2010). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199569922.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-956992-2.

- Curl, James Stevens (2006). A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860678-9. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- Davies, N.; Jokiniemi, E. (2008). Dictionary of Architecture and Building Construction. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-41025-3. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- Davies, N.; Jokiniemi, E. (2012). Architect's Illustrated Pocket Dictionary. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-44406-7. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- DeLaine, Janet (1990). "Structural experimentation: The lintel arch, corbel and tie in western Roman architecture". World Archaeology. 21 (3): 407–424. doi:10.1080/00438243.1990.9980116. ISSN 0043-8243. JSTOR 124838.

- Galliazzo, Vittorio (1995), I ponti romani, vol. 1, Treviso: Edizioni Canova, ISBN 978-88-85066-66-3

- González, Genaro; Samper, Albert; Herrera, Blas (2018). "Classification by Type of the Arches in Gaudí's Palau Güell". Nexus Network Journal. 20 (1): 173–186. doi:10.1007/s00004-017-0355-7. ISSN 1590-5896.

- Gorse, Christopher; Johnston, David; Pritchard, Martin, eds. (2020). A Dictionary of Construction, Surveying and Civil Engineering. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198832485.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-883248-5.

- Graves, Margaret (2 July 2009). "Arches in Islamic architecture". Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t2082057. ISBN 978-1-884446-05-4.

- Heyman, Jacques (2015). "Strainer arches". Construction History. 30 (2). The Construction History Society: 1–14. ISSN 0267-7768. JSTOR 44215905. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- Hourihane, C. (2012). "Arch". The Grove Encyclopedia of Medieval Art and Architecture. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 129–134. ISBN 978-0-19-539536-5. Retrieved 24 December 2024.

- Lyttleton, Margaret (2003). "Trabeated construction". Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t085978.

- Mallgrave, Harry Francis (1988). "Introduction". Modern Architecture: A Guidebook for His Students to this Field of Art. Texts & Documents. Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities. pp. 1–54. ISBN 978-0-226-86939-1. Retrieved 7 February 2024.

- Mark, Robert (July–August 1996). "Architecture and Evolution" (PDF). American Scientist. 84 (4). Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Honor Society: 383–389. JSTOR 29775710.

- Martinez Nespral, Fernando Luis (2023). "Islamic Presence in Latin American Architecture. Three Periods - Three Ways". In Rashid, H.; Petersen, K. (eds.). The Bloomsbury Handbook of Muslims and Popular Culture. Bloomsbury Handbooks. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 13–24. ISBN 978-1-350-14541-2. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- O'Connor, Colin (1993), Roman Bridges, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-39326-3

- Osserman, Robert (February 2010). "Mathematics of the Gateway Arch" (PDF). Notices of the American Mathematical Society. 57 (2): 220–229. ISSN 0002-9920.

- Punmia, B.C.; Jain, Ashok Kumar; Jain, Arun Kumar (2005). Building Construction. Laxmi Publications. ISBN 978-81-7008-053-4. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- Quirarte, Jacinto (1989). "The Art and Architecture of Mesoamerica: An Overview". Latin American Art and Music: A Handbook for Teaching (PDF). Austin, TX: Texas Univ., Austin. Inst. of Latin American Studies. pp. 27–. ISBN 0-86728-012-3.

- Rasch, Jürgen (1985), "Die Kuppel in der römischen Architektur. Entwicklung, Formgebung, Konstruktion", Architectura, vol. 15, pp. 117–139

- Roth, Leland M (1993). Understanding Architecture: Its Elements History and Meaning. Oxford, UK: Westview Press. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-0-06-430158-9.

- Royster, Paula D. (1 January 2021). Decolonizing Arts-Based Methodologies: Researching the African Diaspora. BRILL. doi:10.1163/9789004446120_004. ISBN 978-90-04-44612-0.* Saoud, Rabah (17 January 2002). "The Arch That Never Sleeps" (PDF). Muslim Heritage. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- Slivnik, L. (27 June 2013). "Three–hinged structures in a historical perspective". Structures and Architecture. CRC Press. pp. 1129–1136. doi:10.1201/b15267-153. ISBN 978-0-429-15935-0.

- Sturgis, Russell; Davis, Francis A. (2013). "Triangular Arch". Sturgis' Illustrated Dictionary of Architecture and Building: An Unabridged Reprint of the 1901-2 Edition. Dover Architecture. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-14840-3. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- Vieitez, Fátima Otero (2020). "Past and Present for Arch Executions". Proceedings of ARCH 2019. Structural Integrity. Vol. 11. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 604–611. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-29227-0_65. ISBN 978-3-030-29226-3. S2CID 211581407.

- Warren, John (1991). "Creswell's Use of the Theory of Dating by the Acuteness of the Pointed Arches in Early Muslim Architecture". Muqarnas. 8: 59. doi:10.2307/1523154. Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- Wilkins, H.S.C. (1879). A treatise on mountain roads, live loads, and bridges. E. & F.N. Spon. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- Woodman, Francis; Bloom, Jonathan M. (2003). "Arch". Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t003657. ISBN 978-1-884446-05-4.

External links

[edit]- Physics of Stone Arches by Nova: a model to build an arch without it collapsing

- InteractiveTHRUST: interactive applets, tutorials

- Paper about the three-hinged arch of the Galerie des Machines of 1889 Whitten by Javier Estévez Cimadevila & Isaac López César.

![Separating arches in the St. Zeno church [de]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bf/REI_St_Zeno_23.jpg/120px-REI_St_Zeno_23.jpg)

![Keel arches at Palazzo Guadagni [it]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/27/Keel_arches.jpg/120px-Keel_arches.jpg)

![Curtain arches over windows in Hartenfels Castle [de]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/db/Schloss_Hartenfels%2C_Torgau_2H1A5753WI.jpg/120px-Schloss_Hartenfels%2C_Torgau_2H1A5753WI.jpg)

![A draped arch at the Government Palace of Tlaxcala [es] (1545)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/87/Draped_arch.png/120px-Draped_arch.png)

![Mixed-line arches at Escuelas Menores (Salamanca) [es]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/ff/Salamanca_Escuelas_Menores_494.jpg/120px-Salamanca_Escuelas_Menores_494.jpg)

![Palau Güell: Parabolic[81]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/79/Palau_G%C3%BCell%2C_Barcelona_07.jpg/120px-Palau_G%C3%BCell%2C_Barcelona_07.jpg)

![Palau Güell: Hyperbolic[82]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2d/Palau_G%C3%BCell%2C_Barcelona_114.jpg/120px-Palau_G%C3%BCell%2C_Barcelona_114.jpg)

![Palau Güell: Rankine curve[83] (a.k.a. weighted catenary)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f2/043_Palau_G%C3%BCell%2C_c._Nou_de_la_Rambla_3-5_%28Barcelona%29%2C_baixos.jpg/120px-043_Palau_G%C3%BCell%2C_c._Nou_de_la_Rambla_3-5_%28Barcelona%29%2C_baixos.jpg)

![Palau Güell: Elliptical[84]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f2/Barcelona_Palau_G%C3%BCell_Orgel_%281%29.jpg/120px-Barcelona_Palau_G%C3%BCell_Orgel_%281%29.jpg)

![Ramping arches at Palau Dalmases [ca] in Barcelona](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fb/Palau_Dalmases.jpg/120px-Palau_Dalmases.jpg)

![Shouldered arch around the door of Lorenziberg church [de]. The raised portion is a flat arch.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ec/Frauenstein_Lorenziberg_Filialkirche_hl_Laurentius_Vorlaube_Schulterbogenportal_25042017_7964.jpg/120px-Frauenstein_Lorenziberg_Filialkirche_hl_Laurentius_Vorlaube_Schulterbogenportal_25042017_7964.jpg)

![Ruins of the Kazarma tholos tomb [de] (c.1500 BC) showing the Mycenaean beehive technique](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/42/Kazarma_Tholos_Tomb_1.JPG/120px-Kazarma_Tholos_Tomb_1.JPG)

![King's Gate (Hattusa) [de] (c.1400-1200 BC), an imitation of the parabolic arch by Hittites](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7f/Chatu%C5%A1a%C5%A1%2C_Kr%C3%A1lovsk%C3%A1_br%C3%A1na_-_panoramio.jpg/120px-Chatu%C5%A1a%C5%A1%2C_Kr%C3%A1lovsk%C3%A1_br%C3%A1na_-_panoramio.jpg)