Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Neurotransmitter

View on Wikipedia

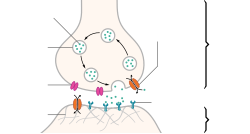

A neurotransmitter is a signaling molecule secreted by a neuron to affect another cell across a synapse. The cell receiving the signal, or target cell, may be another neuron, but could also be a gland or muscle cell.[1]

Neurotransmitters are released from synaptic vesicles into the synaptic cleft where they are able to interact with neurotransmitter receptors on the target cell. Some neurotransmitters are also stored in large dense core vesicles.[2] The neurotransmitter's effect on the target cell is determined by the receptor it binds to. Many neurotransmitters are synthesized from simple and plentiful precursors such as amino acids, which are readily available and often require a small number of biosynthetic steps for conversion.[citation needed]

Neurotransmitters are essential to the function of complex neural systems. The exact number of unique neurotransmitters in humans is unknown, but more than 100 have been identified.[3] Common neurotransmitters include glutamate, GABA, acetylcholine, glycine, dopamine and norepinephrine.

Mechanism and cycle

[edit]Synthesis

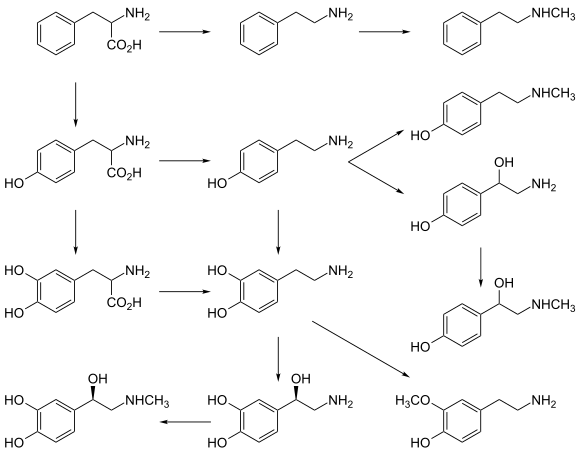

[edit]Neurotransmitters are generally synthesized in neurons and are made up of, or derived from, precursor molecules that are found abundantly in the cell. Classes of neurotransmitters include amino acids, monoamines, and peptides. Monoamines are synthesized by altering a single amino acid. For example, the precursor of serotonin is the amino acid tryptophan. Peptide neurotransmitters, or neuropeptides, are protein transmitters which are larger than the classical small-molecule neurotransmitters and are often released together to elicit a modulatory effect.[4] Purine neurotransmitters, like ATP, are derived from nucleic acids. Metabolic products such as nitric oxide and carbon monoxide have also been reported to act like neurotransmitters.[5]

| Examples | |

|---|---|

| Amino acids | glycine, glutamate |

| Monoamines | serotonin, epinephrine, dopamine |

| Peptides | substance P, opioids |

| Purines | ATP, GTP |

| Other | nitric oxide, carbon monoxide |

Storage

[edit]

Neurotransmitters are generally stored in synaptic vesicles, clustered close to the cell membrane at the axon terminal of the presynaptic neuron. However, some neurotransmitters, like the metabolic gases carbon monoxide and nitric oxide, are synthesized and released immediately following an action potential without ever being stored in vesicles.[6]

Release

[edit]Generally, a neurotransmitter is released via exocytosis at the presynaptic terminal in response to an electrical signal called an action potential in the presynaptic neuron. However, low-level "baseline" release also occurs without electrical stimulation. Neurotransmitters are released into and diffuse across the synaptic cleft, where they bind to specific receptors on the membrane of the postsynaptic neuron.[7]

Receptor interaction

[edit]After being released into the synaptic cleft, neurotransmitters diffuse across the synapse where they are able to interact with receptors on the target cell. The effect of the neurotransmitter is dependent on the identity of the target cell's receptors present at the synapse. Depending on the receptor, binding of neurotransmitters may cause excitation, inhibition, or modulation of the postsynaptic neuron.[8]

Elimination

[edit]

In order to avoid continuous activation of receptors on the post-synaptic or target cell, neurotransmitters must be removed from the synaptic cleft.[9] Neurotransmitters are removed through one of three mechanisms:

- Diffusion – neurotransmitters drift out of the synaptic cleft, where they are absorbed by glial cells. These glial cells, usually astrocytes, absorb the excess neurotransmitters.

- Astrocytes, a type of glial cell in the brain, actively contribute to synaptic communication through astrocytic diffusion or gliotransmission. Neuronal activity triggers an increase in astrocytic calcium levels, prompting the release of gliotransmitters, such as glutamate, ATP, and D-serine. These gliotransmitters diffuse into the extracellular space, interacting with nearby neurons and influencing synaptic transmission. By regulating extracellular neurotransmitter levels, astrocytes help maintain proper synaptic function. This bidirectional communication between astrocytes and neurons add complexity to brain signaling, with implications for brain function and neurological disorders.[10][11]

- Enzyme degradation – proteins called enzymes break the neurotransmitters down.

- Reuptake – neurotransmitters are reabsorbed into the pre-synaptic neuron. Transporters, or membrane transport proteins, pump neurotransmitters from the synaptic cleft back into axon terminals (the presynaptic neuron) where they are stored for reuse.

For example, acetylcholine is eliminated by having its acetyl group cleaved by the enzyme acetylcholinesterase; the remaining choline is then taken in and recycled by the pre-synaptic neuron to synthesize more acetylcholine.[12] Other neurotransmitters are able to diffuse away from their targeted synaptic junctions and are eliminated from the body via the kidneys, or destroyed in the liver. Each neurotransmitter has very specific degradation pathways at regulatory points, which may be targeted by the body's regulatory system or medication. Cocaine blocks a dopamine transporter responsible for the reuptake of dopamine. Without the transporter, dopamine diffuses much more slowly from the synaptic cleft and continues to activate the dopamine receptors on the target cell.[13]

Discovery

[edit]Until the early 20th century, scientists assumed that the majority of synaptic communication in the brain was electrical. However, through histological examinations by Ramón y Cajal, a 20 to 40 nm gap between neurons, known today as the synaptic cleft, was discovered. The presence of such a gap suggested communication via chemical messengers traversing the synaptic cleft, and in 1921 German pharmacologist Otto Loewi confirmed that neurons can communicate by releasing chemicals. Through a series of experiments involving the vagus nerves of frogs, Loewi was able to manually slow the heart rate of frogs by controlling the amount of saline solution present around the vagus nerve. Upon completion of this experiment, Loewi asserted that sympathetic regulation of cardiac function can be mediated through changes in chemical concentrations. Furthermore, Otto Loewi is credited with discovering acetylcholine (ACh) – the first known neurotransmitter.[14]

Identification

[edit]To identify neurotransmitters, the following criteria are typically considered:

- Synthesis: The chemical must be produced within the neuron or be present in it as a precursor molecule.

- Release and response: When the neuron is activated, the chemical must be released and elicit a response in target cells or neurons.

- Experimental response: Application of the chemical directly to the target cells should produce the same response observed when the chemical is naturally released from neurons.

- Removal mechanism: There must be a mechanism in place to remove the neurotransmitter from its site of action once its signaling role is complete.[15]

However, given advances in pharmacology, genetics, and chemical neuroanatomy, the term "neurotransmitter" can be applied to chemicals that:

- Carry messages between neurons via influence on the postsynaptic membrane.

- Have little or no effect on membrane voltage, but have a common carrying function such as changing the structure of the synapse.

- Communicate by sending reverse-direction messages that affect the release or reuptake of transmitters.

The anatomical localization of neurotransmitters is typically determined using immunocytochemical techniques, which identify the location of either the transmitter substances themselves or of the enzymes that are involved in their synthesis. Immunocytochemical techniques have also revealed that many transmitters, particularly the neuropeptides, are co-localized, that is, a neuron may release more than one transmitter from its synaptic terminal.[16] Various techniques and experiments such as staining, stimulating, and collecting can be used to identify neurotransmitters throughout the central nervous system.[17]

Actions

[edit]Neurons communicate with each other through synapses, specialized contact points where neurotransmitters transmit signals. When an action potential reaches the presynaptic terminal, the action potential can trigger the release of neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft. These neurotransmitters then bind to receptors on the postsynaptic membrane, influencing the receiving neuron in either an inhibitory or excitatory manner. If the overall excitatory influences outweigh the inhibitory influences, the receiving neuron may generate its own action potential, continuing the transmission of information to the next neuron in the network. This process allows for the flow of information and the formation of complex neural networks.[18]

Modulation

[edit]A neurotransmitter may have an excitatory, inhibitory or modulatory effect on the target cell. The effect is determined by the receptors the neurotransmitter interacts with at the post-synaptic membrane. Neurotransmitter influences trans-membrane ion flow either to increase (excitatory) or to decrease (inhibitory) the probability that the cell with which it comes in contact will produce an action potential. Synapses containing receptors with excitatory effects are called Type I synapses, while Type II synapses contain receptors with inhibitory effects.[19] Thus, despite the wide variety of synapses, they all convey messages of only these two types. The two types are different appearance and are primarily located on different parts of the neurons under its influence.[20] Receptors with modulatory effects are spread throughout all synaptic membranes and binding of neurotransmitters sets in motion signaling cascades that help the cell regulate its function.[8] Binding of neurotransmitters to receptors with modulatory effects can have many results. For example, it may result in an increase or decrease in sensitivity to future stimulus by recruiting more or less receptors to the synaptic membrane.[citation needed]

Type I (excitatory) synapses are typically located on the shafts or the spines of dendrites, whereas type II (inhibitory) synapses are typically located on a cell body. In addition, Type I synapses have round synaptic vesicles, whereas the vesicles of type II synapses are flattened. The material on the presynaptic and post-synaptic membranes is denser in a Type I synapse than it is in a Type II, and the Type I synaptic cleft is wider. Finally, the active zone on a Type I synapse is larger than that on a Type II synapse.[citation needed]

The different locations of Type I and Type II synapses divide a neuron into two zones: an excitatory dendritic tree and an inhibitory cell body. From an inhibitory perspective, excitation comes in over the dendrites and spreads to the axon hillock to trigger an action potential. If the message is to be stopped, it is best stopped by applying inhibition on the cell body, close to the axon hillock where the action potential originates. Another way to conceptualize excitatory–inhibitory interaction is to picture excitation overcoming inhibition. If the cell body is normally in an inhibited state, the only way to generate an action potential at the axon hillock is to reduce the cell body's inhibition. In this "open the gates" strategy, the excitatory message is like a racehorse ready to run down the track, but first, the inhibitory starting gate must be removed.[21]

Neurotransmitter actions

[edit]As explained above, the only direct action of a neurotransmitter is to activate a receptor. Therefore, the effects of a neurotransmitter system depend on the connections of the neurons that use the transmitter, and the chemical properties of the receptors.

- Glutamate is used at the great majority of fast excitatory synapses in the brain and spinal cord. It is also used at most synapses that are "modifiable", i.e. capable of increasing or decreasing in strength. Modifiable synapses are thought to be the main memory-storage elements in the brain. Excessive glutamate release can overstimulate the brain and lead to excitotoxicity causing cell death resulting in seizures or strokes.[22] Excitotoxicity has been implicated in certain chronic diseases including ischemic stroke, epilepsy, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Alzheimer's disease, Huntington disease, and Parkinson's disease.[23]

- GABA is used at the great majority of fast inhibitory synapses in virtually every part of the brain. Many sedative/tranquilizing drugs act by enhancing the effects of GABA.[24]

- Glycine is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the spinal cord.[25]

- Acetylcholine was the first neurotransmitter discovered in the peripheral and central nervous systems. It activates skeletal muscles in the somatic nervous system and may either excite or inhibit internal organs in the autonomic system.[17] It is the main neurotransmitter at the neuromuscular junction connecting motor nerves to muscles. The paralytic arrow-poison curare acts by blocking transmission at these synapses. Acetylcholine also operates in many regions of the brain as neuromodulatory, but uses different types of receptors, including nicotinic and muscarinic receptors.[26]

- Dopamine has a number of important functions in the brain. This includes critical role in the reward system, motivation and emotional arousal. It also plays an important role in fine motor control; Parkinson's disease has been linked to low levels of dopamine due to the loss of dopaminergic neurons in substantia nigra pars compacta.[27] Schizophrenia, a highly heterogeneous and complicated disorder has been linked to high levels of dopamine.[28]

- Serotonin is a monoamine neurotransmitter. Most of it is produced by the intestine (approximately 90%),[29] and the remainder by central nervous system neurons at the raphe nuclei. It functions to regulate appetite, sleep, memory and learning, temperature, mood, behaviour, muscle contraction, and the functions of the cardiovascular system and endocrine system. It is speculated to have a role in depression, as some depressed patients have been reported to exhibit lower concentrations of metabolites of serotonin in their cerebrospinal fluid and brain tissue.[30]

- Norepinephrine is a member of the catecholamine family of neurotransmitters. It is synthesized from the amino acid tyrosine. In the peripheral nervous system, one of the primary roles of norepinephrine is to stimulate the release of the stress hormone epinephrine (i.e. adrenaline) from the adrenal glands.[31] Norepinephrine is involved in the fight-or-flight response[32] and is also affected in anxiety disorders[33] and depression.[34]

- Epinephrine, a neurotransmitter and hormone is synthesized from tyrosine. It is released from the adrenal glands and also plays a role in the fight-or-flight response. Epinephrine has vasoconstrictive effects, which promote increased heart rate, blood pressure, energy mobilization. Vasoconstriction influences metabolism by promoting the breakdown of glucose released into the bloodstream. Epinephrine also has bronchodilation effects, which is the relaxing of airways.[31]

Types

[edit]There are many different ways to classify neurotransmitters. They are commonly classified into amino acids, monoamines and peptides.[35]

Some of the major neurotransmitters are:

- Amino acids: glutamate,[36] aspartate, D-serine, gamma-Aminobutyric acid (GABA),[nb 1] glycine

- Gasotransmitters: nitric oxide (NO), carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen sulfide (H2S)

- Monoamines:

- Catecholamines: dopamine (DA), norepinephrine (noradrenaline, NE), epinephrine (adrenaline)

- Indolamines: serotonin (5-HT, SER), melatonin

- histamine

- Trace amines: phenethylamine, N-methylphenethylamine, tyramine, 3-iodothyronamine, octopamine, tryptamine, etc.

- Peptides: oxytocin, somatostatin, substance P, cocaine and amphetamine regulated transcript, opioid peptides[37]

- Purines: adenosine triphosphate (ATP), adenosine

- Others: acetylcholine (ACh), anandamide, etc.

In addition, over 100 neuroactive peptides have been found, and new ones are discovered regularly.[38][39] Many of these are co-released along with a small-molecule transmitter. Nevertheless, in some cases, a peptide is the primary transmitter at a synapse. Beta-Endorphin is a relatively well-known example of a peptide neurotransmitter because it engages in highly specific interactions with opioid receptors in the central nervous system.[citation needed]

Single ions (such as synaptically released zinc) are also considered neurotransmitters by some,[40] as well as some gaseous molecules such as nitric oxide (NO), carbon monoxide (CO), and hydrogen sulfide (H2S).[41] The gases are produced in the neural cytoplasm and are immediately diffused through the cell membrane into the extracellular fluid and into nearby cells to stimulate production of second messengers. Soluble gas neurotransmitters are difficult to study, as they act rapidly and are immediately broken down, existing for only a few seconds.[citation needed]

The most prevalent transmitter is glutamate, which is excitatory at well over 90% of the synapses in the human brain.[36] The next most prevalent is gamma-Aminobutyric Acid, or GABA, which is inhibitory at more than 90% of the synapses that do not use glutamate. Although other transmitters are used in fewer synapses, they may be very important functionally: the great majority of psychoactive drugs exert their effects by altering the actions of some neurotransmitter systems, often acting through transmitters other than glutamate or GABA. Addictive drugs such as cocaine and amphetamines exert their effects primarily on the dopamine system. The addictive opiate drugs exert their effects primarily as functional analogs of opioid peptides, which, in turn, regulate dopamine levels.[citation needed]

List of neurotransmitters, peptides, and gaseous signaling molecules

[edit]Neurotransmitter systems

[edit]Neurons expressing certain types of neurotransmitters sometimes form distinct systems, where activation of the system affects large volumes of the brain, called volume transmission. Major neurotransmitter systems include the noradrenaline (norepinephrine) system, the dopamine system, the serotonin system, and the cholinergic system, among others. Trace amines have a modulatory effect on neurotransmission in monoamine pathways (i.e., dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin pathways) throughout the brain via signaling through trace amine-associated receptor 1.[45][46] A brief comparison of these systems follows:

| System | Pathway origin and projections | Regulated cognitive processes and behaviors |

|---|---|---|

| Noradrenaline system [47][48][49][50][51][52] |

Noradrenergic pathways:

|

|

| Dopamine system [49][50][51][53][54][55] |

Dopaminergic pathways:

|

|

| Histamine system [50][51][56] |

Histaminergic pathways:

|

|

| Serotonin system [47][49][50][51][57][58][59] |

Serotonergic pathways:

Caudal nuclei (CN):

Rostral nuclei (RN):

|

|

| Acetylcholine system [47][49][50][51][60] |

Cholinergic pathways:

Forebrain cholinergic nuclei (FCN):

Striatal tonically active cholinergic neurons (TAN)

Brainstem cholinergic nuclei (BCN):

|

|

| Adrenaline system [61][62] |

Adrenergic pathways:

|

Drug effects

[edit]Understanding the effects of drugs on neurotransmitters comprises a significant portion of research initiatives in the field of neuroscience. Most neuroscientists involved in this field of research believe that such efforts may further advance our understanding of the circuits responsible for various neurological diseases and disorders, as well as ways to effectively treat and someday possibly prevent or cure such illnesses.[63][medical citation needed]

Drugs can influence behavior by altering neurotransmitter activity. For instance, drugs can decrease the rate of synthesis of neurotransmitters by affecting the synthetic enzyme(s) for that neurotransmitter. When neurotransmitter syntheses are blocked, the amount of neurotransmitters available for release becomes substantially lower, resulting in a decrease in neurotransmitter activity. Some drugs block or stimulate the release of specific neurotransmitters. Alternatively, drugs can prevent neurotransmitter storage in synaptic vesicles by causing the synaptic vesicle membranes to leak. Drugs that prevent a neurotransmitter from binding to its receptor are called receptor antagonists. For example, drugs used to treat patients with schizophrenia such as haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and clozapine are antagonists at receptors in the brain for dopamine. Other drugs act by binding to a receptor and mimicking the normal neurotransmitter. Such drugs are called receptor agonists. An example of a receptor agonist is morphine, an opiate that mimics effects of the endogenous neurotransmitter β-endorphin to relieve pain. Other drugs interfere with the deactivation of a neurotransmitter after it has been released, thereby prolonging the action of a neurotransmitter. This can be accomplished by blocking re-uptake or inhibiting degradative enzymes. Lastly, drugs can also prevent an action potential from occurring, blocking neuronal activity throughout the central and peripheral nervous system. Drugs such as tetrodotoxin that block neural activity are typically lethal.[citation needed]

Drugs targeting the neurotransmitter of major systems affect the whole system, which can explain the complexity of action of some drugs. Cocaine, for example, blocks the re-uptake of dopamine back into the presynaptic neuron, leaving the neurotransmitter molecules in the synaptic gap for an extended period of time. Since the dopamine remains in the synapse longer, the neurotransmitter continues to bind to the receptors on the postsynaptic neuron, eliciting a pleasurable emotional response. Physical addiction to cocaine may result from prolonged exposure to excess dopamine in the synapses, which leads to the downregulation of some post-synaptic receptors. After the effects of the drug wear off, an individual can become depressed due to decreased probability of the neurotransmitter binding to a receptor. Fluoxetine is a selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor (SSRI), which blocks re-uptake of serotonin by the presynaptic cell which increases the amount of serotonin present at the synapse and furthermore allows it to remain there longer, providing potential for the effect of naturally released serotonin.[64] AMPT prevents the conversion of tyrosine to L-DOPA, the precursor to dopamine; reserpine prevents dopamine storage within vesicles; and deprenyl inhibits monoamine oxidase (MAO)-B and thus increases dopamine levels.[citation needed]

| Drug | Interacts with | Receptor interaction | Type | Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Botulinum toxin (Botox) | Acetylcholine | – | Antagonist | Blocks acetylcholine release in PNS

Prevents muscle contractions |

| Black widow spider venom | Acetylcholine | – | Agonist | Promotes acetylcholine release in PNS

Stimulates muscle contractions |

| Neostigmine | Acetylcholine | – | – | Interferes with acetylcholinerase activity

Increases effects of ACh at receptors Used to treat myasthenia gravis |

| Nicotine | Acetylcholine | Nicotinic (skeletal muscle) | Agonist | Increases ACh activity

Increases attention Reinforcing effects |

| d-tubocurarine | Acetylcholine | Nicotinic (skeletal muscle) | Antagonist | Decreases activity at receptor site |

| Curare | Acetylcholine | Nicotinic (skeletal muscle) | Antagonist | Decreases ACh activity

Prevents muscle contractions |

| Muscarine | Acetylcholine | Muscarinic (heart and smooth muscle) | Agonist | Increases ACh activity

Toxic |

| Atropine | Acetylcholine | Muscarinic (heart and smooth muscle) | Antagonist | Blocks pupil constriction

Blocks saliva production |

| Scopolamine (hyoscine) | Acetylcholine | Muscarinic (heart and smooth muscle) | Antagonist | Treats motion sickness and postoperative nausea and vomiting |

| AMPT | Dopamine/norepinephrine | – | – | Inactivates tyrosine hydroxylase and inhibits dopamine production |

| Reserpine | Dopamine | – | – | Prevents storage of dopamine and other monoamines in synaptic vesicles

Causes sedation and depression |

| Apomorphine | Dopamine | D2 receptor (presynaptic autoreceptors/postsynaptic receptors) | Antagonist (low dose) / direct agonist (high dose) | Low dose: blocks autoreceptors

High dose: stimulates postsynaptic receptors |

| Amphetamine | Dopamine/norepinephrine | – | Indirect agonist | Releases dopamine, noradrenaline, and serotonin |

| Methamphetamine | Dopamine/norepinephrine | – | – | Releases dopamine and noradrenaline

Blocks reuptake |

| Methylphenidate | Dopamine | – | – | Blocks reuptake

Enhances attention and impulse control in ADHD |

| Cocaine | Dopamine | – | Indirect agonist | Blocks reuptake into presynapse

Blocks voltage-dependent sodium channels Can be used as a topical anesthetic (eye drops) |

| Deprenyl | Dopamine | – | Agonist | Inhibits MAO-B

Prevents destruction of dopamine |

| Chlorpromazine | Dopamine | D2 Receptors | Antagonist | Blocks D2 receptors

Alleviates hallucinations |

| MPTP | Dopamine | – | – | Results in Parkinson-like symptoms |

| PCPA | Serotonin (5-HT) | – | Antagonist | Disrupts serotonin synthesis by blocking the activity of tryptophan hydroxylase |

| Ondansetron | Serotonin (5-HT) | 5-HT3 receptors | Antagonist | Reduces side effects of chemotherapy and radiation

Reduces nausea and vomiting |

| Buspirone | Serotonin (5-HT) | 5-HT1A receptors | Partial agonist | Treats symptoms of anxiety and depression |

| Fluoxetine | Serotonin (5-HT) | supports 5-HT reuptake | SSRI | Inhibits reuptake of serotonin

Treats depression, some anxiety disorders, and OCD[64] Common examples: Prozac and Sarafem |

| Fenfluramine | Serotonin (5-HT) | – | – | Causes release of serotonin

Inhibits reuptake of serotonin Used as an appetite suppressant |

| Lysergic acid diethylamide | Serotonin (5-HT) | Post-synaptic 5-HT2A receptors | Direct agonist | Produces visual perception distortions

Stimulates 5-HT2A receptors in forebrain |

| Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) | Serotonin (5-HT)/norepinphrine | – | – | Stimulates release of serotonin and norepinephrine and inhibits the reuptake

Causes excitatory and hallucinogenic effects |

| Strychnine | Glycine | – | Antagonist | Causes severe muscle spasms[66] |

| Diphenhydramine | Histamine | Crosses blood–brain barrier to cause drowsiness | ||

| Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) | Endocannabinoids | Cannabinoid (CB) receptors | Agonist | Produces analgesia and sedation

Increases appetite Cognitive effects |

| Rimonabant | Endocannabinoids | Cannabinoid (CB) receptors | Antagonist | Suppresses appetite

Used in smoking cessation |

| MAFP | Endocannabinoids | – | – | Inhibits FAAH

Used in research to increase cannabinoid system activity |

| AM1172 | Endocannabinoids | – | – | Blocks cannabinoid reuptake

Used in research to increase cannabinoid system activity |

| Anandamide (endogenous) | – | Cannabinoid (CB) receptors; 5-HT3 receptors | – | Reduce nausea and vomiting |

| Caffeine | Adenosine | Adenosine receptors | Antagonist | Blocks adenosine receptors

Increases wakefulness |

| PCP | Glutamate | NMDA receptor | Indirect antagonist | Blocks PCP binding site

Prevents calcium ions from entering neurons Impairs learning |

| AP5 | Glutamate | NMDA receptor | Antagonist | Blocks glutamate binding site on NMDA receptor

Impairs synaptic plasticity and certain forms of learning |

| Ketamine | Glutamate | NMDA receptor | Antagonist | Used as anesthesia

Induces trance-like state, helps with pain relief and sedation |

| NMDA | Glutamate | NMDA receptor | Agonist | Used in research to study NMDA receptor

Ionotropic receptor |

| AMPA | Glutamate | AMPA receptor | Agonist | Used in research to study AMPA receptor

Ionotropic receptor |

| Allyglycine | GABA | – | – | Inhibits GABA synthesis

Causes seizures |

| Muscimol | GABA | GABA receptor | Agonist | Causes sedation |

| Bicuculine | GABA | GABA receptor | Antagonist | Causes Seizures |

| Benzodiazepines | GABA | GABAA receptor | Indirect agonists | Anxiolytic, sedation, memory impairment, muscle relaxation |

| Barbiturates | GABA | GABAA receptor | Indirect agonists | Sedation, memory impairment, muscle relaxation |

| Alcohol | GABA | GABA receptor | Indirect agonist | Sedation, memory impairment, muscle relaxation |

| Picrotoxin | GABA | GABAA receptor | Indirect antagonist | High doses cause seizures |

| Tiagabine | GABA | – | Antagonist | GABA transporter antagonist

Increase availability of GABA Reduces the likelihood of seizures |

| Moclobemide | Norepinephrine | – | Agonist | Blocks MAO-A to treat depression |

| Idazoxan | Norepinephrine | alpha-2 adrenergic autoreceptors | Agonist | Blocks alpha-2 autoreceptors

Used to study norepinephrine system |

| Fusaric acid | Norepinephrine | – | – | Inhibits activity of dopamine beta-hydroxylase which blocks the production of norepinephrine

Used to study norepinephrine system without affecting dopamine system |

| Opiates (opium, morphine, heroin, and oxycodone) | Opioids | Opioid receptor[67] | Agonists | Analgesia, sedation, and reinforcing effects |

| Naloxone | Opioids | – | Antagonist | Reverses opiate intoxication or overdose symptoms (i.e. problems with breathing) |

Agonists

[edit]This section needs expansion with: coverage of full agonists and their distinction from partial agonist and inverse agonist.. You can help by adding to it. (August 2015) |

An agonist is a chemical capable of binding to a receptor, such as a neurotransmitter receptor, and initiating the same reaction typically produced by the binding of the endogenous substance.[68] An agonist of a neurotransmitter will thus initiate the same receptor response as the transmitter. In neurons, an agonist drug may activate neurotransmitter receptors either directly or indirectly. Direct-binding agonists can be further characterized as full agonists, partial agonists, inverse agonists.[69][70]

Direct agonists act similar to a neurotransmitter by binding directly to its associated receptor site(s), which may be located on the presynaptic neuron or postsynaptic neuron, or both.[71] Typically, neurotransmitter receptors are located on the postsynaptic neuron, while neurotransmitter autoreceptors are located on the presynaptic neuron, as is the case for monoamine neurotransmitters;[45] in some cases, a neurotransmitter utilizes retrograde neurotransmission, a type of feedback signaling in neurons where the neurotransmitter is released postsynaptically and binds to target receptors located on the presynaptic neuron.[72][note 1] Nicotine, a compound found in tobacco, is a direct agonist of most nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, mainly located in cholinergic neurons.[67] Opiates, such as morphine, heroin, hydrocodone, oxycodone, codeine, and methadone, are μ-opioid receptor agonists; this action mediates their euphoriant and pain relieving properties.[67]

Indirect agonists increase the binding of neurotransmitters at their target receptors by stimulating the release or preventing the reuptake of neurotransmitters.[71] Some indirect agonists trigger neurotransmitter release and prevent neurotransmitter reuptake. Amphetamine, for example, is an indirect agonist of postsynaptic dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin receptors in each their respective neurons;[45][46] it produces both neurotransmitter release into the presynaptic neuron and subsequently the synaptic cleft and prevents their reuptake from the synaptic cleft by activating TAAR1, a presynaptic G protein-coupled receptor, and binding to a site on VMAT2, a type of monoamine transporter located on synaptic vesicles within monoamine neurons.[45][46]

Antagonists

[edit]An antagonist is a chemical that acts within the body to reduce the physiological activity of another chemical substance (such as an opiate); especially one that opposes the action on the nervous system of a drug or a substance occurring naturally in the body by combining with and blocking its nervous receptor.[73]

There are two main types of antagonist: direct-acting Antagonist and indirect-acting Antagonists:

- Direct-acting antagonist- which takes up space present on receptors which are otherwise taken up by neurotransmitters themselves. This results in neurotransmitters being blocked from binding to the receptors. An example of one of the most common is called Atropine.

- Indirect-acting antagonist- drugs that inhibit the release/production of neurotransmitters (e.g., Reserpine).

Drug antagonists

[edit]An antagonist drug is one that attaches (or binds) to a site called a receptor without activating that receptor to produce a biological response. It is therefore said to have no intrinsic activity. An antagonist may also be called a receptor "blocker" because they block the effect of an agonist at the site. The pharmacological effects of an antagonist, therefore, result in preventing the corresponding receptor site's agonists (e.g., drugs, hormones, neurotransmitters) from binding to and activating it. Antagonists may be "competitive" or "irreversible".[citation needed]

A competitive antagonist competes with an agonist for binding to the receptor. As the concentration of antagonist increases, the binding of the agonist is progressively inhibited, resulting in a decrease in the physiological response. High concentration of an antagonist can completely inhibit the response. This inhibition can be reversed, however, by an increase of the concentration of the agonist, since the agonist and antagonist compete for binding to the receptor. Competitive antagonists, therefore, can be characterized as shifting the dose–response relationship for the agonist to the right. In the presence of a competitive antagonist, it takes an increased concentration of the agonist to produce the same response observed in the absence of the antagonist.[citation needed]

An irreversible antagonist binds so strongly to the receptor as to render the receptor unavailable for binding to the agonist. Irreversible antagonists may even form covalent chemical bonds with the receptor. In either case, if the concentration of the irreversible antagonist is high enough, the number of unbound receptors remaining for agonist binding may be so low that even high concentrations of the agonist do not produce the maximum biological response.[74]

Diseases and disorders

[edit]The following sections describe how imbalances or dysfunction in specific neurotransmitters—dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate—have been tentatively linked to various mental or neurological disorders.

Dopamine

[edit]For example, problems in producing dopamine (mainly in the substantia nigra) can result in Parkinson's disease, a disorder that affects a person's ability to move as they want to, resulting in stiffness, tremors or shaking, and other symptoms. Some studies suggest that having too little or too much dopamine or problems using dopamine in the thinking and feeling regions of the brain may play a role in disorders like schizophrenia or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Dopamine is also involved in addiction and drug use, as most recreational drugs cause an influx of dopamine in the brain (especially opioid and methamphetamines) that produces a pleasurable feeling, which is why users constantly crave drugs.[78]

Serotonin

[edit]Similarly, after some research suggested that drugs that block the recycling, or reuptake, of serotonin seemed to help some people diagnosed with depression, it was theorized that people with depression might have lower-than-normal serotonin levels. Though widely popularized, this theory was not borne out in subsequent research.[79] Therefore, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are used to increase the amounts of serotonin in synapses.[citation needed]

Glutamate

[edit]

Furthermore, problems with producing or using glutamate have been suggestively and tentatively linked to many mental disorders, including autism, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), schizophrenia, and depression.[80] Having too much glutamate has been linked to neurological diseases such as Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer's disease, stroke, and ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis).[81]

Neurotransmitter imbalance

[edit]Generally, there are no scientifically established "norms" for appropriate levels or "balances" of different neurotransmitters. In most cases, it is practically impossible to measure neurotransmitter levels in the brain or body at any given moment. Neurotransmitters regulate each other's release, and weak consistent imbalances in this mutual regulation were linked to temperament in healthy people.[82][83][84][85][86] However, significant imbalances or disruptions in neurotransmitter systems are associated with various diseases and mental disorders, including Parkinson's disease, depression, insomnia, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), anxiety, memory loss, dramatic weight changes, and addictions. Some of these conditions are also related to neurotransmitter switching, a phenomenon where neurons change the type of neurotransmitters they release.[87][88][89] Chronic physical or emotional stress can be a contributor to neurotransmitter system changes. Genetics also plays a role in neurotransmitter activities.

Apart from recreational use, medications that directly and indirectly interact with one or more transmitter or its receptor are commonly prescribed for psychiatric and psychological issues. Notably, drugs interacting with serotonin and norepinephrine are prescribed to patients with problems such as depression and anxiety—though the notion that there is much solid medical evidence to support such interventions has been widely criticized.[90] Studies shown that dopamine imbalance has an influence on multiple sclerosis and other neurological disorders.[91]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ In the central nervous system, anandamide other endocannabinoids utilize retrograde neurotransmission, since their release is postsynaptic, while their target receptor, cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1), is presynaptic.[72] The cannabis plant contains Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, which is a direct agonist at CB1.[72]

- ^ GABA is a non-proteinogenic amino acid

References

[edit]- ^ Smelser, Neil J.; Baltes, Paul B. (2001). International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (1st ed.). Amsterdam New York: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-043076-8.

- ^ Edwards, Robert H (December 1998). "Neurotransmitter release: Variations on a theme". Current Biology. 8 (24): R883 – R885. Bibcode:1998CBio....8.R883E. doi:10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00551-9. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 9843673.

- ^ Cuevas J (1 January 2019). "Neurotransmitters and Their Life Cycle". Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-801238-3.11318-2. ISBN 978-0-12-801238-3.

- ^ Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, Katz LC, LaMantia AS, McNamara JO, Williams SM (2001). "Peptide Neurotransmitters". Neuroscience (2nd ed.). Sinauer Associates.

- ^ Xue, L.; Farrugia, G.; Miller, S. M.; Ferris, C. D.; Snyder, S. H.; Szurszewski, J. H. (15 February 2000). "Carbon monoxide and nitric oxide as coneurotransmitters in the enteric nervous system: Evidence from genomic deletion of biosynthetic enzymes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 97 (4): 1851–1855. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.1851X. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.4.1851. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 26525. PMID 10677545.

- ^ Sanders KM, Ward SM (January 2019). "Nitric oxide and its role as a non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic inhibitory neurotransmitter in the gastrointestinal tract". British Journal of Pharmacology. 176 (2): 212–227. doi:10.1111/bph.14459. PMC 6295421. PMID 30063800.

- ^ Elias LJ, Saucier DM (2005). Neuropsychology: Clinical and Experimental Foundations. Boston: Pearson.

- ^ a b Di Chiara G, Morelli M, Consolo S (June 1994). "Modulatory functions of neurotransmitters in the striatum: ACh/dopamine/NMDA interactions". Trends in Neurosciences. 17 (6): 228–233. doi:10.1016/0166-2236(94)90005-1. PMID 7521083. S2CID 32085555.

- ^ Chergui K, Suaud-Chagny MF, Gonon F (October 1994). "Nonlinear relationship between impulse flow, dopamine release and dopamine elimination in the rat brain in vivo". Neuroscience. 62 (3): 641–645. doi:10.1016/0306-4522(94)90465-0. PMID 7870295. S2CID 20465561.

- ^ Mustafa, Asif K.; Kim, Paul M.; Snyder, Solomon H. (August 2004). "D-Serine as a putative glial neurotransmitter". Neuron Glia Biology. 1 (3): 275–281. doi:10.1017/S1740925X05000141. ISSN 1741-0533. PMC 1403160. PMID 16543946.

- ^ Wolosker, Herman; Dumin, Elena; Balan, Livia; Foltyn, Veronika N. (July 2008). "d-Amino acids in the brain: d-serine in neurotransmission and neurodegeneration: d-Serine in neurotransmission and neurodegeneration". FEBS Journal. 275 (14): 3514–3526. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06515.x. PMID 18564180. S2CID 25735605.

- ^ Thapa S, Lv M, Xu H (30 November 2017). "Acetylcholinesterase: A Primary Target for Drugs and Insecticides". Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 17 (17): 1665–1676. doi:10.2174/1389557517666170120153930. PMID 28117022.

- ^ Vasica G, Tennant CC (September 2002). "Cocaine use and cardiovascular complications". The Medical Journal of Australia. 177 (5): 260–262. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04761.x. PMID 12197823. S2CID 18572638.

- ^ Saladin, Kenneth S. Anatomy and Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function. McGraw Hill. 2009 ISBN 0-07-727620-5

- ^ Teleanu, Raluca Ioana; Niculescu, Adelina-Gabriela; Roza, Eugenia; Vladâcenco, Oana; Grumezescu, Alexandru Mihai; Teleanu, Daniel Mihai (25 May 2022). "Neurotransmitters—Key Factors in Neurological and Neurodegenerative Disorders of the Central Nervous System". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23 (11): 5954. doi:10.3390/ijms23115954. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 9180936. PMID 35682631.

- ^ Breedlove SM, Watson NV (2013). Biological psychology: an introduction to behavioral, cognitive, and clinical neuroscience (Seventh ed.). Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-927-5.

- ^ a b Whishaw B, Kolb IQ (2014). An introduction to brain and behavior (4th ed.). New York, NY: Worth Publishers. pp. 150–151. ISBN 978-1-4292-4228-8.

- ^ Purves, Dale; Augustine, George J.; Fitzpatrick, David; Katz, Lawrence C.; LaMantia, Anthony-Samuel; McNamara, James O.; Williams, S. Mark (2001), "Excitatory and Inhibitory Postsynaptic Potentials", Neuroscience. 2nd edition, Sinauer Associates, retrieved 14 July 2023

- ^ Peters A, Palay SL (December 1996). "The morphology of synapses". Journal of Neurocytology. 25 (12): 687–700. doi:10.1007/BF02284835. PMID 9023718. S2CID 29365393.

- ^ Shier D, Butler J, Lewis R (5 January 2015). Hole's human anatomy & physiology (Fourteenth ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 978-0-07-802429-0. OCLC 881146319.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Whishaw B, Kolb IQ (2014). An introduction to brain and behavior (4th ed.). New York, NY: Worth Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4292-4228-8.

- ^ Gross L (November 2006). ""Supporting" players take the lead in protecting the overstimulated brain". PLOS Biology. 4 (11) e371. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040371. PMC 1609133. PMID 20076484.

- ^ Yang JL, Sykora P, Wilson DM, Mattson MP, Bohr VA (August 2011). "The excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate stimulates DNA repair to increase neuronal resiliency". Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 132 (8–9): 405–11. doi:10.1016/j.mad.2011.06.005. PMC 3367503. PMID 21729715.

- ^ Orexin receptor antagonists a new class of sleeping pill, National Sleep Foundation.

- ^ Rajendra, Sundran; Lynch, Joseph W.; Schofield, Peter R. (January 1997). "The glycine receptor". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 73 (2): 121–146. doi:10.1016/S0163-7258(96)00163-5. PMID 9131721.

- ^ "Acetylcholine Receptors". Ebi.ac.uk. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ Fahn, Stanley; Jankovic, Joseph; Hallett, Mark (1 January 2011), Fahn, Stanley; Jankovic, Joseph; Hallett, Mark (eds.), "Chapter 3 - Functional neuroanatomy of the basal ganglia", Principles and Practice of Movement Disorders (Second Edition), Edinburgh: W.B. Saunders, pp. 55–65, doi:10.1016/b978-1-4377-2369-4.00003-2, ISBN 978-1-4377-2369-4, retrieved 25 November 2024

- ^ Schacter, Gilbert and Weger. Psychology.United States of America.2009.Print.

- ^ Terry, Natalie; Margolis, Kara Gross (2017), Greenwood-Van Meerveld, Beverley (ed.), "Serotonergic Mechanisms Regulating the GI Tract: Experimental Evidence and Therapeutic Relevance", Gastrointestinal Pharmacology, vol. 239, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 319–342, doi:10.1007/164_2016_103, ISBN 978-3-319-56360-2, PMC 5526216, PMID 28035530

- ^ University of Bristol. "Introduction to Serotonin". Retrieved 15 October 2009.

- ^ a b Sheffler, Zachary M.; Reddy, Vamsi; Pillarisetty, Leela Sharath (2023), "Physiology, Neurotransmitters", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30969716, retrieved 16 July 2023

- ^ Fitzgerald, P. J. (April 2015). "Noradrenaline transmission reducing drugs may protect against a broad range of diseases". Autonomic and Autacoid Pharmacology. 34 (3–4): 15–26. doi:10.1111/aap.12019. ISSN 1474-8665. PMID 25271382.

- ^ Bouras, Nadia N.; Mack, Nancy R.; Gao, Wen-Jun (17 April 2023). "Prefrontal modulation of anxiety through a lens of noradrenergic signaling". Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 17. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2023.1173326. ISSN 1662-5137. PMC 10149815. PMID 37139472.

- ^ Moret, Chantal; Briley, Mike (31 May 2011). "The importance of norepinephrine in depression". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 7 (Supplement 1): 9–13. doi:10.2147/NDT.S19619. PMC 3131098. PMID 21750623.

- ^ Prasad BV (2020). Examining Biological Foundations of Human Behavior. United States of America: IGI Global. p. 81. ISBN 978-1799-8286-17.

- ^ a b Sapolsky R (2005). "Biology and Human Behavior: The Neurological Origins of Individuality, 2nd". The Teaching Company.

see pages 13 & 14 of Guide Book

- ^ Snyder SH, Innis RB (1979). "Peptide neurotransmitters". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 48: 755–82. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.48.070179.003543. PMID 38738.

- ^ Corbière A, Vaudry H, Chan P, Walet-Balieu ML, Lecroq T, Lefebvre A, et al. (18 September 2019). "Strategies for the Identification of Bioactive Neuropeptides in Vertebrates". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 13: 948. doi:10.3389/fnins.2019.00948. PMC 6759750. PMID 31619945.

- ^ Fricker LD, Devi LA (May 2018). "Orphan neuropeptides and receptors: Novel therapeutic targets". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 185: 26–33. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.11.006. PMC 5899030. PMID 29174650.

- ^ Kodirov SA, Takizawa S, Joseph J, Kandel ER, Shumyatsky GP, Bolshakov VY (October 2006). "Synaptically released zinc gates long-term potentiation in fear conditioning pathways". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (41): 15218–23. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10315218K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0607131103. PMC 1622803. PMID 17005717.

- ^ "International Symposium on Nitric Oxide – Dr. John Andrews – MaRS". MaRS. Archived from the original on 14 October 2014.

- ^ "Dopamine: Biological activity". IUPHAR/BPS guide to pharmacology. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ Grandy DK, Miller GM, Li JX (February 2016). ""TAARgeting Addiction"--The Alamo Bears Witness to Another Revolution: An Overview of the Plenary Symposium of the 2015 Behavior, Biology and Chemistry Conference". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 159: 9–16. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.014. PMC 4724540. PMID 26644139.

TAAR1 is a high-affinity receptor for METH/AMPH and DA

- ^ Lin Y, Hall RA, Kuhar MJ (October 2011). "CART peptide stimulation of G protein-mediated signaling in differentiated PC12 cells: identification of PACAP 6-38 as a CART receptor antagonist". Neuropeptides. 45 (5): 351–8. doi:10.1016/j.npep.2011.07.006. PMC 3170513. PMID 21855138.

- ^ a b c d e Miller GM (January 2011). "The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity". Journal of Neurochemistry. 116 (2): 164–76. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. PMC 3005101. PMID 21073468.

- ^ a b c d Eiden LE, Weihe E (January 2011). "VMAT2: a dynamic regulator of brain monoaminergic neuronal function interacting with drugs of abuse". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1216 (1): 86–98. Bibcode:2011NYASA1216...86E. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05906.x. PMC 4183197. PMID 21272013.

VMAT2 is the CNS vesicular transporter for not only the biogenic amines DA, NE, EPI, 5-HT, and HIS, but likely also for the trace amines TYR, PEA, and thyronamine (THYR) ... [Trace aminergic] neurons in mammalian CNS would be identifiable as neurons expressing VMAT2 for storage, and the biosynthetic enzyme aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AADC).

- ^ a b c Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 6: Widely Projecting Systems: Monoamines, Acetylcholine, and Orexin". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

Different subregions of the VTA receive glutamatergic inputs from the prefrontal cortex, orexinergic inputs from the lateral hypothalamus, cholinergic and also glutamatergic and GABAergic inputs from the laterodorsal tegmental nucleus and pedunculopontine nucleus, noradrenergic inputs from the locus ceruleus, serotonergic inputs from the raphe nuclei, and GABAergic inputs from the nucleus accumbens and ventral pallidum.

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 6: Widely Projecting Systems: Monoamines, Acetylcholine, and Orexin". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 145, 156–157. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

Descending NE fibers modulate afferent pain signals. ... The locus ceruleus (LC), which is located on the floor of the fourth ventricle in the rostral pons, contains more than 50% of all noradrenergic neurons in the brain; it innervates both the forebrain (eg, it provides virtually all the NE to the cerebral cortex) and regions of the brainstem and spinal cord. ... The other noradrenergic neurons in the brain occur in loose collections of cells in the brainstem, including the lateral tegmental regions. These neurons project largely within the brainstem and spinal cord. NE, along with 5HT, ACh, histamine, and orexin, is a critical regulator of the sleep-wake cycle and of levels of arousal. ... LC firing may also increase anxiety ...Stimulation of β-adrenergic receptors in the amygdala results in enhanced memory for stimuli encoded under strong negative emotion ... Epinephrine occurs in only a small number of central neurons, all located in the medulla. Epinephrine is involved in visceral functions, such as control of respiration.

- ^ a b c d Rang HP (2003). Pharmacology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 474 for noradrenaline system, page 476 for dopamine system, page 480 for serotonin system and page 483 for cholinergic system. ISBN 978-0-443-07145-4.

- ^ a b c d e Iwańczuk W, Guźniczak P (2015). "Neurophysiological foundations of sleep, arousal, awareness and consciousness phenomena. Part 1". Anaesthesiology Intensive Therapy. 47 (2): 162–7. doi:10.5603/AIT.2015.0015. PMID 25940332.

The ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) is responsible for a sustained wakefulness state. ... The thalamic projection is dominated by cholinergic neurons originating from the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus of pons and midbrain (PPT) and laterodorsal tegmental nucleus of pons and midbrain (LDT) nuclei [17, 18]. The hypothalamic projection involves noradrenergic neurons of the locus coeruleus (LC) and serotoninergic neurons of the dorsal and median raphe nuclei (DR), which pass through the lateral hypothalamus and reach axons of the histaminergic tubero-mamillary nucleus (TMN), together forming a pathway extending into the forebrain, cortex and hippocampus. Cortical arousal also takes advantage of dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra (SN), ventral tegmenti area (VTA) and the periaqueductal grey area (PAG). Fewer cholinergic neurons of the pons and midbrain send projections to the forebrain along the ventral pathway, bypassing the thalamus [19, 20].

- ^ a b c d e Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 12: Sleep and Arousal". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

The ARAS is a complex structure consisting of several different circuits including the four monoaminergic pathways ... The norepinephrine pathway originates from the locus ceruleus (LC) and related brainstem nuclei; the serotonergic neurons originate from the raphe nuclei within the brainstem as well; the dopaminergic neurons originate in ventral tegmental area (VTA); and the histaminergic pathway originates from neurons in the tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN) of the posterior hypothalamus. As discussed in Chapter 6, these neurons project widely throughout the brain from restricted collections of cell bodies. Norepinephrine, serotonin, dopamine, and histamine have complex modulatory functions and, in general, promote wakefulness. The PT in the brain stem is also an important component of the ARAS. Activity of PT cholinergic neurons (REM-on cells) promotes REM sleep. During waking, REM-on cells are inhibited by a subset of ARAS norepinephrine and serotonin neurons called REM-off cells.

- ^ Rinaman L (February 2011). "Hindbrain noradrenergic A2 neurons: diverse roles in autonomic, endocrine, cognitive, and behavioral functions". American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 300 (2): R222-35. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00556.2010. PMC 3043801. PMID 20962208.

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 6: Widely Projecting Systems: Monoamines, Acetylcholine, and Orexin". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 147–148, 154–157. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

Neurons from the SNc densely innervate the dorsal striatum where they play a critical role in the learning and execution of motor programs. Neurons from the VTA innervate the ventral striatum (nucleus accumbens), olfactory bulb, amygdala, hippocampus, orbital and medial prefrontal cortex, and cingulate cortex. VTA DA neurons play a critical role in motivation, reward-related behavior, attention, and multiple forms of memory. ... Thus, acting in diverse terminal fields, dopamine confers motivational salience ("wanting") on the reward itself or associated cues (nucleus accumbens shell region), updates the value placed on different goals in light of this new experience (orbital prefrontal cortex), helps consolidate multiple forms of memory (amygdala and hippocampus), and encodes new motor programs that will facilitate obtaining this reward in the future (nucleus accumbens core region and dorsal striatum). ... DA has multiple actions in the prefrontal cortex. It promotes the "cognitive control" of behavior: the selection and successful monitoring of behavior to facilitate attainment of chosen goals. Aspects of cognitive control in which DA plays a role include working memory, the ability to hold information "on line" in order to guide actions, suppression of prepotent behaviors that compete with goal-directed actions, and control of attention and thus the ability to overcome distractions. ... Noradrenergic projections from the LC thus interact with dopaminergic projections from the VTA to regulate cognitive control. ...

- ^ Calipari ES, Bagot RC, Purushothaman I, Davidson TJ, Yorgason JT, Peña CJ, et al. (March 2016). "In vivo imaging identifies temporal signature of D1 and D2 medium spiny neurons in cocaine reward". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (10): 2726–31. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.2726C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1521238113. PMC 4791010. PMID 26831103.

Previous work has demonstrated that optogenetically stimulating D1 MSNs promotes reward, whereas stimulating D2 MSNs produces aversion.

- ^ Ikemoto S (November 2010). "Brain reward circuitry beyond the mesolimbic dopamine system: a neurobiological theory". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 35 (2): 129–50. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.02.001. PMC 2894302. PMID 20149820.

Recent studies on intracranial self-administration of neurochemicals (drugs) found that rats learn to self-administer various drugs into the mesolimbic dopamine structures–the posterior ventral tegmental area, medial shell nucleus accumbens and medial olfactory tubercle. ... In the 1970s it was recognized that the olfactory tubercle contains a striatal component, which is filled with GABAergic medium spiny neurons receiving glutamatergic inputs form cortical regions and dopaminergic inputs from the VTA and projecting to the ventral pallidum just like the nucleus accumbens

Figure 3: The ventral striatum and self-administration of amphetamine - ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 6: Widely Projecting Systems: Monoamines, Acetylcholine, and Orexin". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 175–176. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

Within the brain, histamine is synthesized exclusively by neurons with their cell bodies in the tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN) that lies within the posterior hypothalamus. There are approximately 64000 histaminergic neurons per side in humans. These cells project throughout the brain and spinal cord. Areas that receive especially dense projections include the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, neostriatum, nucleus accumbens, amygdala, and hypothalamus. ... While the best characterized function of the histamine system in the brain is regulation of sleep and arousal, histamine is also involved in learning and memory ...It also appears that histamine is involved in the regulation of feeding and energy balance.

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 6: Widely Projecting Systems: Monoamines, Acetylcholine, and Orexin". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 158–160. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

[The] dorsal raphe preferentially innervates the cerebral cortex, thalamus, striatal regions (caudate-putamen and nucleus accumbens), and dopaminergic nuclei of the midbrain (eg, the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area), while the median raphe innervates the hippocampus, septum, and other structures of the limbic forebrain. ... it is clear that 5HT influences sleep, arousal, attention, processing of sensory information in the cerebral cortex, and important aspects of emotion (likely including aggression) and mood regulation. ...The rostral nuclei, which include the nucleus linearis, dorsal raphe, medial raphe, and raphe pontis, innervate most of the brain, including the cerebellum. The caudal nuclei, which comprise the raphe magnus, raphe pallidus, and raphe obscuris, have more limited projections that terminate in the cerebellum, brainstem, and spinal cord.

- ^ Nestler EJ. "Brain Reward Pathways". Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Nestler Lab. Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

The dorsal raphe is the primary site of serotonergic neurons in the brain, which, like noradrenergic neurons, pervasively modulate brain function to regulate the state of activation and mood of the organism.

- ^ Marston OJ, Garfield AS, Heisler LK (June 2011). "Role of central serotonin and melanocortin systems in the control of energy balance". European Journal of Pharmacology. 660 (1): 70–9. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.12.024. PMID 21216242.

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 6: Widely Projecting Systems: Monoamines, Acetylcholine, and Orexin". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 167–175. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

The basal forebrain cholinergic nuclei are comprised the medial septal nucleus (Ch1), the vertical nucleus of the diagonal band (Ch2), the horizontal limb of the diagonal band (Ch3), and the nucleus basalis of Meynert (Ch4). Brainstem cholinergic nuclei include the pedunculopontine nucleus (Ch5), the laterodorsal tegmental nucleus (Ch6), the medial habenula (Ch7), and the parabigeminal nucleus (Ch8).

- ^ Guyenet PG, Stornetta RL, Bochorishvili G, Depuy SD, Burke PG, Abbott SB (August 2013). "C1 neurons: the body's EMTs". American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 305 (3): R187-204. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00054.2013. PMC 3743001. PMID 23697799.

- ^ Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG (March 2018). "C1 neurons: a nodal point for stress?". Experimental Physiology. 103 (3): 332–336. doi:10.1113/EP086435. PMC 5832554. PMID 29080216.

- ^ "Neuron Conversations: How Brain Cells Communicate". Brainfacts.org. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ a b Yadav VK, Ryu JH, Suda N, Tanaka KF, Gingrich JA, Schütz G, et al. (November 2008). "Lrp5 controls bone formation by inhibiting serotonin synthesis in the duodenum". Cell. 135 (5): 825–37. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.059. PMC 2614332. PMID 19041748.

- ^ Carlson, N. R., & Birkett, M. A. (2017). Physiology of Behavior (12th ed.). Pearson, pp. 100–115. ISBN 978-0134080918

- ^ "CDC Strychnine. Facts about Strychnine". Public Health Emergency Preparedness & Response. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ a b c "Neurotransmitters and Drugs Chart". Ocw.mit.edu. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ "Agonist – Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". Merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ Atack J., Lavreysen H. (2010) Agonist. In: Stolerman I.P. (eds) Encyclopedia of Psychopharmacology. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-68706-1_1565

- ^ Roth BL (February 2016). "DREADDs for Neuroscientists". Neuron. 89 (4): 683–694. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2016.01.040. PMC 4759656. PMID 26889809.

- ^ a b Ries RK, Fiellin DA, Miller SC (2009). Principles of addiction medicine (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 709–710. ISBN 978-0-7817-7477-2. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ a b c Flores A, Maldonado R, Berrendero F (December 2013). "Cannabinoid-hypocretin cross-talk in the central nervous system: what we know so far". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 7: 256. doi:10.3389/fnins.2013.00256. PMC 3868890. PMID 24391536.

• Figure 1: Schematic of brain CB1 expression and orexinergic neurons expressing OX1 or OX2

• Figure 2: Synaptic signaling mechanisms in cannabinoid and orexin systems - ^ "Antagonist". Medical definition of Antagonist. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ Goeders NE (2001). "Antagonist". Encyclopedia of Drugs, Alcohol, and Addictive Behavior. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ Broadley KJ (March 2010). "The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 125 (3): 363–375. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.005. PMID 19948186.

- ^ Lindemann L, Hoener MC (May 2005). "A renaissance in trace amines inspired by a novel GPCR family". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 26 (5): 274–281. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.007. PMID 15860375.

- ^ Wang X, Li J, Dong G, Yue J (February 2014). "The endogenous substrates of brain CYP2D". European Journal of Pharmacology. 724: 211–218. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.12.025. PMID 24374199.

- ^ "Dopamine: What It Is, Function & Symptoms". Cleveland Clinic. Archived from the original on 3 March 2025. Retrieved 7 March 2025.

- ^ Healy D (April 2015). "Serotonin and depression". BMJ. 350 h1771. doi:10.1136/bmj.h1771. PMID 25900074. S2CID 38726584.

- ^ "NIMH Brain Basics". U.S. National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ Bittigau P, Ikonomidou C (November 1997). "Glutamate in neurologic diseases". Journal of Child Neurology. 12 (8): 471–85. doi:10.1177/088307389701200802. PMID 9430311. S2CID 1258390.

- ^ Netter, P. (1991) Biochemical variables in the study of temperament. In Strelau, J. & Angleitner, A. (Eds.), Explorations in temperament: International perspectives on theory and measurement 147–161. New York: Plenum Press.

- ^ Trofimova I, Robbins TW (May 2016). "Temperament and arousal systems: A new synthesis of differential psychology and functional neurochemistry". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 64: 382–402. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.03.008. hdl:11375/26202. PMID 26969100. S2CID 13937324.

- ^ Cloninger CR, Svrakic DM, Przybeck TR. A psychobiological model of temperament and character" Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:975-990.

- ^ Trofimova IN (2016). "The interlocking between functional aspects of activities and a neurochemical model of adult temperament.". In Arnold MC (ed.). Temperaments: Individual Differences, Social and Environmental Influences and Impact on Quality of Life. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc. pp. 77–147.

- ^ Depue RA, Morrone-Strupinsky JV (June 2005). "A neurobehavioral model of affiliative bonding: implications for conceptualizing a human trait of affiliation". The Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 28 (3): 313–50, discussion 350–95. doi:10.1017/s0140525x05000063. PMID 16209725.

- ^ Spitzer, Nicholas C. (25 July 2017). "Neurotransmitter Switching in the Developing and Adult Brain". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 40 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-072116-031204. ISSN 0147-006X. PMID 28301776.

- ^ Dolan, Eric W. (13 November 2024). "Neurotransmitter switching in early development predicts autism-related behaviors". PsyPost - Psychology News. Retrieved 22 November 2024.

- ^ Pratelli, Marta; Hakimi, Anna M.; Thaker, Arth; Jang, Hyeonseok; Li, Hui-quan; Godavarthi, Swetha K.; Lim, Byung Kook; Spitzer, Nicholas C. (26 September 2024). "Drug-induced change in transmitter identity is a shared mechanism generating cognitive deficits". Nature Communications. 15 (1): 8260. Bibcode:2024NatCo..15.8260P. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-52451-x. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 11427679. PMID 39327428.

- ^ Leo, J., & Lacasse, J. (10 October 2007). The Media and the Chemical Imbalance Theory of Depression. Retrieved 1 December 2014, from http://psychrights.org/articles/TheMediaandChemicalImbalanceTheoryofDepression.pdf

- ^ Dobryakova E, Genova HM, DeLuca J, Wylie GR (12 March 2015). "The dopamine imbalance hypothesis of fatigue in multiple sclerosis and other neurological disorders". Frontiers in Neurology. 6: 52. doi:10.3389/fneur.2015.00052. PMC 4357260. PMID 25814977.

External links

[edit]- Purves, Dale; Augustine, George J.; Fitzpatrick, David; Katz, Lawrence C.; LaMantia, Anthony-Samuel; McNamara, James O.; Williams, S. Mark (2001). "Chapter 6. Neurotransmitters". What Defines a Neurotransmitter? (2nd ed.). Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates. ISBN 0-87893-742-0.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Holz, Ronald W.; Fisher, Stephen K. (1999). "Chapter 10. Synaptic Transmission and Cellular Signaling: An Overview". In Siegel, George J; Agranoff, Bernard W; Albers, R Wayne; Fisher, Stephen K; Uhler, Michael D (eds.). Synaptic Transmission (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven. ISBN 0-397-51820-X.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Neurotransmitters and Neuroactive Peptides at Neuroscience for Kids website