Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pyrolysis

View on Wikipedia

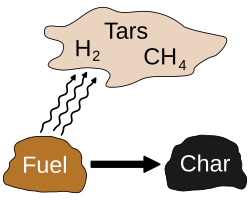

Pyrolysis (/paɪˈrɒlɪsɪs/; from Ancient Greek πῦρ pûr 'fire' and λύσις lýsis 'separation') is a process involving the separation of covalent bonds in organic matter by thermal decomposition within an inert environment without oxygen.[1][2][3]

Applications

[edit]Pyrolysis is most commonly used in the treatment of organic materials. It is one of the processes involved in the charring of wood.[4] In general, pyrolysis of organic substances produces volatile products and leaves char, a carbon-rich solid residue. Extreme pyrolysis, which leaves mostly carbon as the residue, is called carbonization. Pyrolysis is considered one of the steps in the processes of gasification or combustion.[5][6] Compared to syngas, pyrolysis gas has a high percentage of heavy tar fractions, which condense at relatively high temperatures, preventing its direct use in gas burners and internal combustion engines.

The process is used heavily in the chemical industry, for example, to produce ethylene, many forms of carbon, and other chemicals from petroleum, coal, and even wood, or to produce coke from coal. It is used also in the conversion of natural gas (primarily methane) into hydrogen gas and solid carbon char, recently introduced on an industrial scale.[7] Aspirational applications of pyrolysis would convert biomass into syngas and biochar, waste plastics back into usable oil, or waste into safely disposable substances.

Terminology

[edit]Pyrolysis is one of the various types of chemical degradation processes that occur at higher temperatures (above the boiling point of water or other solvents). It differs from other processes like combustion and hydrolysis in that it usually does not involve the addition of other reagents such as oxygen (O

2, in combustion) or water (in hydrolysis).[8] Pyrolysis produces solids (char), condensable liquids (heavy and light oils, and tar), and non-condensable gasses.[9][10][11][12]

Pyrolysis is different from gasification. In the chemical process industry, pyrolysis refers to a partial thermal degradation of carbonaceous materials that takes place in an inert (oxygen free) atmosphere and produces both gases, liquids and solids. The pyrolysis can be extended to full gasification that produces mainly gaseous output,[13] often with the addition of e.g. water steam to gasify residual carbonic solids, see Steam reforming.

Types

[edit]Specific types of pyrolysis include:

- Carbonization, the complete pyrolysis of organic matter, which usually leaves a solid residue that consists mostly of elemental carbon.

- Methane pyrolysis, the direct conversion of methane to hydrogen fuel and separable solid carbon, sometimes using molten metal catalysts.

- Hydrous pyrolysis, in the presence of superheated water or steam, producing hydrogen and substantial atmospheric carbon dioxide.

- Dry distillation, as in the original production of sulfuric acid from sulfates.

- Destructive distillation, as in the manufacture of charcoal, coke and activated carbon.

- Charcoal burning, the production of charcoal.

- Tar production by destructive distillation of wood in tar kilns.

- Caramelization of sugars.

- High-temperature cooking processes such as roasting, frying, toasting, and grilling.

- Cracking of heavier hydrocarbons into lighter ones, as in oil refining.

- Thermal depolymerization, which breaks down plastics and other polymers into monomers and oligomers.

- Ceramization[14] involving the formation of polymer derived ceramics from preceramic polymers under an inert atmosphere.

- Catagenesis, the natural conversion of buried organic matter to fossil fuels.

- Flash vacuum pyrolysis, used in organic synthesis.

Other pyrolysis types come from a different classification that focuses on the pyrolysis operating conditions and heating system used, which have an impact on the yield of the pyrolysis products.

| Pyrolysis | Operating conditions | Pyrolysis product yield (wt%) |

|---|---|---|

| Slow low temperature pyrolysis[15] | Temperature: 250–450 °C

Vapor residence time: 10–100 min Heating rate: 0.1–1 °C/s Feedstock size: 5–50 mm |

Bio-oil ~30

Biochar~35 Gases~35 |

| Intermediate pyrolysis[16] | Temperature: 600–800 °C

Vapor residence time: 0.5–20 s Heating rate: 1.0–10 °C/s Feedstock size: 1–5 mm |

Bio-oil~50

Biochar~25 Gases~35 |

| Fast low temperature pyrolysis[15] | Temperature: 250–450°C

Vapor residence time: 0.5–5 s Heating rate: 10–200 °C/s Feedstock size: <3 mm |

Bio-oil ~50

Biochar~20 Gases~30 |

| Flash pyrolysis[15] | Temperature: 800–1000 °C

Vapor residence time: <5 s Heating rate: >1000 °C/s Feedstock size: <0.2 mm |

Bio-oil ~75

Biochar~12 Gases~13 |

| Hydro pyrolysis[16] | Temperature: 350–600 °C

Vapor residence time: >15 s Heating rate: 10–300 °C/s |

Not assigned |

| High temperature pyrolysis | Temperature: 800–1150 °C

Vapor residence time: 10–100 min Heating rate: 0.1–1 °C/s |

Bio-oil ~43

Biochar~22 Gases~45 |

History

[edit]

Pyrolysis has been used for turning wood into charcoal since ancient times. The ancient Egyptians used the liquid fraction obtained from the pyrolysis of cedar wood in their embalming process.[17]

The dry distillation of wood remained the major source of methanol into the early 20th century.[18] Pyrolysis was instrumental in the discovery of many chemical substances, such as phosphorus from ammonium sodium hydrogen phosphate NH4NaHPO4 in concentrated urine, oxygen from mercuric oxide, and various nitrates.[citation needed]

General processes and mechanisms

[edit]

Pyrolysis generally consists of heating the material above its decomposition temperature, breaking chemical bonds in its molecules. The fragments usually become smaller molecules, but may combine to produce residues with larger molecular mass, even amorphous covalent solids.[citation needed]

In many settings, some amounts of oxygen, water, or other substances may be present, so that combustion, hydrolysis, or other chemical processes may occur besides pyrolysis proper. Sometimes those chemicals are added intentionally, as in the burning of firewood, in the traditional manufacture of charcoal, and in the steam cracking of crude oil.[citation needed]

Conversely, the starting material may be heated in a vacuum or in an inert atmosphere to avoid chemical side reactions (such as combustion or hydrolysis). Pyrolysis in a vacuum also lowers the boiling point of the byproducts, improving their recovery.

When organic matter is heated at increasing temperatures in open containers, the following processes generally occur, in successive or overlapping stages:[citation needed]

- Below about 100 °C, volatiles, including some water, evaporate. Heat-sensitive substances, such as vitamin C and proteins, may partially change or decompose already at this stage.

- At about 100 °C or slightly higher, any remaining water that is merely absorbed in the material is driven off. This process consumes a lot of energy, so the temperature may stop rising until all water has evaporated. Water trapped in crystal structure of hydrates may come off at somewhat higher temperatures.

- Some solid substances, like fats, waxes, and sugars, may melt and separate.

- Between 100 and 500 °C, many common organic molecules break down. Most sugars start decomposing at 160–180 °C. Cellulose, a major component of wood, paper,& and cotton fabrics, decomposes at about 350 °C.[5] Lignin, another major wood component, starts decomposing at about 350 °C, but continues releasing volatile products up to 500 °C.[5] The decomposition products usually include water, carbon monoxide CO and/or carbon dioxide CO2, as well as a large number of organic compounds.[6][19] Gases and volatile products leave the sample, and some of them may condense again as smoke. Generally, this process also absorbs energy. Some volatiles may ignite and burn, creating a visible flame. The non-volatile residues typically become richer in carbon and form large disordered molecules, with colors ranging between brown and black. At this point the matter is said to have been "charred" or "carbonized".

- At 200–300 °C, if oxygen has not been excluded, the carbonaceous residue may start to burn, in a highly exothermic reaction, often with no or little visible flame. Once carbon combustion starts, the temperature rises spontaneously, turning the residue into a glowing ember and releasing carbon dioxide and/or monoxide. At this stage, some of the nitrogen still remaining in the residue may be oxidized into nitrogen oxides like NO2 and N2O3. Sulfur and other elements like chlorine and arsenic may be oxidized and volatilized at this stage.

- Once combustion of the carbonaceous residue is complete, a powdery or solid mineral residue (ash) is often left behind, consisting of inorganic oxidized materials of high melting point. Some of the ash may have left during combustion, entrained by the gases as fly ash or particulate emissions. Metals present in the original matter usually remain in the ash as oxides or carbonates, such as potash. Phosphorus, from materials such as bone, phospholipids, and nucleic acids, usually remains as phosphates.

Safety challenges

[edit]Because pyrolysis takes place at high temperatures which exceed the autoignition temperature of the produced gases, an explosion risk exists if oxygen is present. Careful temperature control is needed for pyrolysis systems, which can be accomplished with pyrolysis controller.[20] Pyrolysis also produces various toxic gases, such as carbon monoxide. The greatest risk of fire, explosion, and release of toxic gases comes when the system is starting up and shutting down, operating intermittently, or during operational upsets.[21]

Inert gas purging is essential to manage inherent explosion risks. The procedure is not trivial and failure to keep oxygen out has led to accidents.[22]

Occurrence and uses

[edit]Clandestine chemistry

[edit]Conversion of CBD to THC can be brought about by pyrolysis.[23][24]

Cooking

[edit]Pyrolysis has many applications in food preparation.[25] Caramelization is the pyrolysis of sugars in food (often after the sugars have been produced by the breakdown of polysaccharides). The food goes brown and changes flavor. The distinctive flavors are used in many dishes; for instance, caramelized onion is used in French onion soup.[26][27] The temperatures needed for caramelization lie above the boiling point of water.[26] Frying oil can easily rise above the boiling point. Putting a lid on the frying pan keeps the water in, re-condensing some and keeping the temperature too cool to brown.

Pyrolysis of food can also be undesirable, as in the charring of burnt food (at temperatures too low for the oxidative combustion of carbon to produce flames and burn the food to ash).

Coke, carbon, charcoals, and chars

[edit]Carbon and carbon-rich materials have desirable properties but are nonvolatile, even at high temperatures. Consequently, pyrolysis is used to produce many kinds of carbon; these can be used for fuel, as reagents in steelmaking (coke), and as structural materials.

Charcoal is a less smoky fuel than pyrolyzed wood.[28] Some cities ban, or used to ban, wood fires; when residents only use charcoal (and similarly treated rock coal, called coke) air pollution is significantly reduced. In cities where people do not generally cook or heat with fires, this is not needed. In the mid-20th century, "smokeless" legislation in Europe required cleaner-burning techniques, such as coke fuel[29] and smoke-burning incinerators[30] as an effective measure to reduce air pollution.[29]

The coke-making or "coking" process consists of heating the material in "coking ovens" to very high temperatures (up to 900 °C or 1,700 °F) so that the molecules are broken down into lighter volatile substances, which leave the vessel, and a porous but hard residue that is mostly carbon and inorganic ash. The amount of volatiles varies with the source material, but is typically 25–30% of it by weight. High temperature pyrolysis is used on an industrial scale to convert coal into coke. This is useful in metallurgy, where the higher temperatures are necessary for many processes, such as steelmaking. Volatile by-products of this process are also often useful, including benzene and pyridine.[31] Coke can also be produced from the solid residue left from petroleum refining.

The original vascular structure of the wood and the pores created by escaping gases combine to produce a light and porous material. By starting with a dense wood-like material, such as nutshells or peach stones, one obtains a form of charcoal with particularly fine pores (and hence a much larger pore surface area), called activated carbon, which is used as an adsorbent for a wide range of chemical substances.

Biochar is the residue of incomplete organic pyrolysis, e.g., from cooking fires. It is a key component of the terra preta soils associated with ancient indigenous communities of the Amazon basin.[32] Terra preta is much sought by local farmers for its superior fertility and capacity to promote and retain an enhanced suite of beneficial microbiota, compared to the typical red soil of the region. Efforts are underway to recreate these soils through biochar, the solid residue of pyrolysis of various materials, mostly organic waste.

Carbon fibers are filaments of carbon that can be used to make very strong yarns and textiles. Carbon fiber items are often produced by spinning and weaving the desired item from fibers of a suitable polymer, and then pyrolyzing the material at a high temperature (from 1,500–3,000 °C or 2,730–5,430 °F). The first carbon fibers were made from rayon, but polyacrylonitrile has become the most common starting material. For their first workable electric lamps, Joseph Wilson Swan and Thomas Edison used carbon filaments made by pyrolysis of cotton yarns and bamboo splinters, respectively.

Pyrolysis is the reaction used to coat a preformed substrate with a layer of pyrolytic carbon. This is typically done in a fluidized bed reactor heated to 1,000–2,000 °C or 1,830–3,630 °F. Pyrolytic carbon coatings are used in many applications, including artificial heart valves.[33]

Liquid and gaseous biofuels

[edit]Pyrolysis is the basis of several methods for producing fuel from biomass, i.e. lignocellulosic biomass.[34] Crops studied as biomass feedstock for pyrolysis include native North American prairie grasses such as switchgrass and bred versions of other grasses such as Miscantheus giganteus. Other sources of organic matter as feedstock for pyrolysis include greenwaste, sawdust, waste wood, leaves, vegetables, nut shells, straw, cotton trash, rice hulls, and orange peels.[5] Animal waste including poultry litter, dairy manure, and potentially other manures are also under evaluation. Some industrial byproducts are also suitable feedstock including paper sludge, distillers grain,[35] and sewage sludge.[36]

In the biomass components, the pyrolysis of hemicellulose happens between 210 and 310 °C.[5] The pyrolysis of cellulose starts from 300 to 315 °C and ends at 360–380 °C, with a peak at 342–354 °C.[5] Lignin starts to decompose at about 200 °C and continues until 1000 °C.[37]

Synthetic diesel fuel by pyrolysis of organic materials is not yet economically competitive.[38] Higher efficiency is sometimes achieved by flash pyrolysis, in which finely divided feedstock is quickly heated to between 350 and 500 °C (660 and 930 °F) for less than two seconds.

Syngas is usually produced by pyrolysis.[25]

The low quality of oils produced through pyrolysis can be improved by physical and chemical processes,[39] which might drive up production costs, but may make sense economically as circumstances change.

There is also the possibility of integrating with other processes such as mechanical biological treatment and anaerobic digestion.[40] Fast pyrolysis is also investigated for biomass conversion.[41] Fuel bio-oil can also be produced by hydrous pyrolysis.

Methane pyrolysis for hydrogen

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (July 2025) |

Methane pyrolysis[42] is an industrial process for "turquoise" hydrogen production from methane by removing solid carbon from natural gas.[43] This one-step process produces hydrogen in high volume at low cost (less than steam reforming with carbon sequestration).[44] No greenhouse gas is released. No deep well injection of carbon dioxide is needed. Only water is released when hydrogen is used as the fuel for fuel-cell electric heavy truck transportation, [45][46][47][48][49] gas turbine electric power generation,[50][51] and hydrogen for industrial processes including producing ammonia fertilizer and cement.[52][53] Methane pyrolysis is the process operating around 1065 °C for producing hydrogen from natural gas that allows removal of carbon easily (solid carbon is a byproduct of the process).[54][55] The industrial quality solid carbon can then be sold or landfilled and is not released into the atmosphere, avoiding emission of greenhouse gas (GHG) or ground water pollution from a landfill.

In 2015, a company called Monolith Materials built a pilot plant in Redwood City, CA to study scaling Methane Pyrolysis using renewable power in the process.[56] A successful pilot project then led to a larger commercial-scale demonstration plant in Hallam, Nebraska in 2016.[57] As of 2020, this plant is operational and can produce around 14 metric tons of hydrogen per day. In 2021, the US Department of Energy backed Monolith Materials' plans for major expansion with a $1B loan guarantee.[58] The funding will help produce a plant capable of generating 164 metric tons of hydrogen per day by 2024. Pilots with gas utilities and biogas plants are underway with companies like Modern Hydrogen.[59][60] Volume production is also being evaluated in the BASF "methane pyrolysis at scale" pilot plant,[7] the chemical engineering team at University of California - Santa Barbara[61] and in such research laboratories as Karlsruhe Liquid-metal Laboratory (KALLA).[62] Power for process heat consumed is only one-seventh of the power consumed in the water electrolysis method for producing hydrogen.[63]

The Australian company Hazer Group was founded in 2010 to commercialise technology originally developed at the University of Western Australia. The company was listed on the ASX in December 2015. It is completing a commercial demonstration project to produce renewable hydrogen and graphite from wastewater and iron ore as a process catalyst use technology created by the University of Western Australia (UWA). The Commercial Demonstration Plant project is an Australian first, and expected to produce around 100 tonnes of fuel-grade hydrogen and 380 tonnes of graphite each year starting in 2023.[citation needed] It was scheduled to commence in 2022. "10 December 2021: Hazer Group (ASX: HZR) regret to advise that there has been a delay to the completion of the fabrication of the reactor for the Hazer Commercial Demonstration Project (CDP). This is expected to delay the planned commissioning of the Hazer CDP, with commissioning now expected to occur after our current target date of 1Q 2022."[64] The Hazer Group has collaboration agreements with Engie for a facility in France in May 2023,[65] A Memorandum of Understanding with Chubu Electric & Chiyoda in Japan April 2023[66] and an agreement with Suncor Energy and FortisBC to develop 2,500 tonnes per Annum Burrard-Hazer Hydrogen Production Plant in Canada April 2022[67][68]

The American company C-Zero's technology converts natural gas into hydrogen and solid carbon. The hydrogen provides clean, low-cost energy on demand, while the carbon can be permanently sequestered.[69] C-Zero announced in June 2022 that it closed a $34 million financing round led by SK Gas, a subsidiary of South Korea's second-largest conglomerate, the SK Group. SK Gas was joined by two other new investors, Engie New Ventures and Trafigura, one of the world's largest physical commodities trading companies, in addition to participation from existing investors including Breakthrough Energy Ventures, Eni Next, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, and AP Ventures. Funding was for C-Zero's first pilot plant, which was expected to be online in Q1 2023. The plant may be capable of producing up to 400 kg of hydrogen per day from natural gas with no CO2 emissions.[70]

One of the world's largest chemical companies, BASF, has been researching hydrogen pyrolysis for more than 10 years.[71]

Ethylene

[edit]Pyrolysis is used to produce ethylene, the chemical compound produced on the largest scale industrially (>110 million tons/year in 2005). In this process, hydrocarbons from petroleum are heated to around 600 °C (1,112 °F) in the presence of steam; this is called steam cracking. The resulting ethylene is used to make antifreeze (ethylene glycol), PVC (via vinyl chloride), and many other polymers, such as polyethylene and polystyrene.[72]

Semiconductors

[edit]

The process of metalorganic vapour-phase epitaxy (MOCVD) entails pyrolysis of volatile organometallic compounds to give semiconductors, hard coatings, and other applicable materials. The reactions entail thermal degradation of precursors, with deposition of the inorganic component and release of the hydrocarbons as gaseous waste. Since it is an atom-by-atom deposition, these atoms organize themselves into crystals to form the bulk semiconductor. Raw polycrystalline silicon is produced by the chemical vapor deposition of silane gases:

- SiH4 → Si + 2 H2

Gallium arsenide, another semiconductor, forms upon co-pyrolysis of trimethylgallium and arsine.

Waste management

[edit]Pyrolysis can also be used to treat municipal solid waste and plastic waste.[6][19][73] The main advantage is the reduction in volume of the waste. In principle, pyrolysis will regenerate the monomers (precursors) to the polymers that are treated, but in practice the process is neither a clean nor an economically competitive source of monomers.[74][75][76]

In tire waste management, tire pyrolysis is a well-developed technology.[77] Other products from car tire pyrolysis include steel wires, carbon black and bitumen.[78] The area faces legislative, economic, and marketing obstacles.[79] Oil derived from tire rubber pyrolysis has a high sulfur content, which gives it high potential as a pollutant; consequently it should be desulfurized.[80][81]

Alkaline pyrolysis of sewage sludge at low temperature of 500 °C can enhance H

2 production with in-situ carbon capture. The use of NaOH (sodium hydroxide) has the potential to produce H

2-rich gas that can be used for fuels cells directly.[36][82]

In early November 2021, the U.S. State of Georgia announced a joint effort with Igneo Technologies to build an $85 million large electronics recycling plant in the Port of Savannah. The project will focus on lower-value, plastics-heavy devices in the waste stream using multiple shredders and furnaces using pyrolysis technology.[83]

Waste from pyrolysis itself can also be used for useful products. For example, contaminant-rich retentate from liquid-fed pyrolysis of postconsumer multilayer packaging waste can be used as novel building composite materials, which have higher compression strengths (10–12 MPa) than construction bricks and brickworks (7 MPa), as well as 57% lower density, 0.77 g/cm3.[84]

One-stepwise pyrolysis and two-stepwise pyrolysis for tobacco waste

[edit]Pyrolysis has also been used in trying to mitigate tobacco waste. One method was done where tobacco waste was separated into two categories, TLW (Tobacco Leaf Waste) and TSW (Tobacco Stick Waste). TLW was determined to be any waste from cigarettes and TSW was determined to be any waste from electronic cigarettes. Both TLW and TSW were dried at 80 °C for 24 hours and stored in a desiccator.[85] Samples were grounded so that the contents were uniform. Tobacco Waste (TW) also contains inorganic (metal) contents, which was determined using an inductively coupled plasma-optical spectrometer.[85] Thermo-gravimetric analysis was used to thermally degrade four samples (TLW, TSW, glycerol, and guar gum) and monitored under specific dynamic temperature conditions.[85] About one gram of both TLW and TSW were used in the pyrolysis tests. During these analysis tests, CO

2 and N

2 were used as atmospheres inside of a tubular reactor that was built using quartz tubing. For both CO

2 and N

2 atmospheres the flow rate was 100 mL min−1.[85] External heating was created via a tubular furnace. The pyrogenic products were classified into three phases. The first phase was biochar, a solid residue produced by the reactor at 650 °C. The second phase liquid hydrocarbons were collected by a cold solvent trap and sorted by using chromatography. The third and final phase was analyzed using an online micro GC unit and those pyrolysates were gases.

Two different types of experiments were conducted: one-stepwise pyrolysis and two-stepwise pyrolysis. One-stepwise pyrolysis consisted of a constant heating rate (10 °C min−1) from 30 to 720 °C.[85] In the second step of the two-stepwise pyrolysis test the pyrolysates from the one-stepwise pyrolysis were pyrolyzed in the second heating zone which was controlled isothermally at 650 °C.[85] The two-stepwise pyrolysis was used to focus primarily on how well CO

2 affects carbon redistribution when adding heat through the second heating zone.[85]

First noted was the thermolytic behaviors of TLW and TSW in both the CO

2 and N

2 environments. For both TLW and TSW the thermolytic behaviors were identical at less than or equal to 660 °C in the CO

2 and N

2 environments. The differences between the environments start to occur when temperatures increase above 660 °C and the residual mass percentages significantly decrease in the CO

2 environment compared to that in the N

2 environment.[85] This observation is likely due to the Boudouard reaction, where we see spontaneous gasification happening when temperatures exceed 710 °C.[86][87] Although these observations were seen at temperatures lower than 710 °C it is most likely due to the catalytic capabilities of inorganics in TLW.[85] It was further investigated by doing ICP-OES measurements and found that a fifth of the residual mass percentage was Ca species. CaCO

3 is used in cigarette papers and filter material, leading to the explanation that degradation of CaCO

3 causes pure CO

2 reacting with CaO in a dynamic equilibrium state.[85] This being the reason for seeing mass decay between 660 °C and 710 °C. Differences in differential thermogram (DTG) peaks for TLW were compared to TSW. TLW had four distinctive peaks at 87, 195, 265, and 306 °C whereas TSW had two major drop offs at 200 and 306 °C with one spike in between.[85] The four peaks indicated that TLW contains more diverse types of additives than TSW.[85] The residual mass percentage between TLW and TSW was further compared, where the residual mass in TSW was less than that of TLW for both CO

2 and N

2 environments concluding that TSW has higher quantities of additives than TLW.

The one-stepwise pyrolysis experiment showed different results for the CO

2 and N

2 environments. During this process the evolution of 5 different notable gases were observed. Hydrogen, Methane, Ethane, Carbon Dioxide, and Ethylene all are produced when the thermolytic rate of TLW began to be retarded at greater than or equal to 500 °C. Thermolytic rate begins at the same temperatures for both the CO

2 and N

2 environment but there is higher concentration of the production of Hydrogen, Ethane, Ethylene, and Methane in the N

2 environment than that in the CO

2 environment. The concentration of CO in the CO

2 environment is significantly greater as temperatures increase past 600 °C and this is due to CO

2 being liberated from CaCO

3 in TLW.[85] This significant increase in CO concentration is why there is lower concentrations of other gases produced in the CO

2 environment due to a dilution effect.[85] Since pyrolysis is the re-distribution of carbons in carbon substrates into three pyrogenic products.[85] The CO

2 environment is going to be more effective because the CO

2 reduction into CO allows for the oxidation of pyrolysates to form CO. In conclusion the CO

2 environment allows a higher yield of gases than oil and biochar. When the same process is done for TSW the trends are almost identical therefore the same explanations can be applied to the pyrolysis of TSW.[85]

Harmful chemicals were reduced in the CO

2 environment due to CO formation causing tar to be reduced. One-stepwise pyrolysis was not that effective on activating CO

2 on carbon rearrangement due to the high quantities of liquid pyrolysates (tar). Two-stepwise pyrolysis for the CO

2 environment allowed for greater concentrations of gases due to the second heating zone. The second heating zone was at a consistent temperature of 650 °C isothermally.[85] More reactions between CO

2 and gaseous pyrolysates with longer residence time meant that CO

2 could further convert pyrolysates into CO.[85] The results showed that the two-stepwise pyrolysis was an effective way to decrease tar content and increase gas concentration by about 10 wt.% for both TLW (64.20 wt.%) and TSW (73.71%).[85]

Thermal cleaning

[edit]Pyrolysis is also used for thermal cleaning, an industrial application to remove organic substances such as polymers, plastics and coatings from parts, products or production components like extruder screws, spinnerets[88] and static mixers. During the thermal cleaning process, at temperatures from 310 to 540 °C (600 to 1,000 °F),[89] organic material is converted by pyrolysis and oxidation into volatile organic compounds, hydrocarbons and carbonized gas.[90] Inorganic elements remain.[91]

Several types of thermal cleaning systems use pyrolysis:

- Molten Salt Baths belong to the oldest thermal cleaning systems; cleaning with a molten salt bath is very fast but implies the risk of dangerous splatters, or other potential hazards connected with the use of salt baths, like explosions or highly toxic hydrogen cyanide gas.[89]

- Fluidized Bed Systems[92] use sand or aluminium oxide as heating medium;[93] these systems also clean very fast but the medium does not melt or boil, nor emit any vapors or odors;[89] the cleaning process takes one to two hours.[90]

- Vacuum Ovens use pyrolysis in a vacuum[94] avoiding uncontrolled combustion inside the cleaning chamber;[89] the cleaning process takes 8[90] to 30 hours.[95]

- Burn-Off Ovens, also known as Heat-Cleaning Ovens, are gas-fired and used in the painting, coatings, electric motors and plastics industries for removing organics from heavy and large metal parts.[96]

Fine chemical synthesis

[edit]Pyrolysis is used in the production of chemical compounds, mainly, but not only, in the research laboratory.

The area of boron-hydride clusters started with the study of the pyrolysis of diborane (B

2H

6) at ca. 200 °C. Products include the clusters pentaborane and decaborane. These pyrolyses involve not only cracking (to give H

2), but also recondensation.[97]

The synthesis of nanoparticles,[98] zirconia[99] and oxides[100] utilizing an ultrasonic nozzle in a process called ultrasonic spray pyrolysis (USP).

Other uses and occurrences

[edit]- Pyrolysis is used to turn organic materials into carbon for the purpose of carbon-14 dating.

- Pyrolysis liquids from slow pyrolysis of bark and hemp have been tested for their antifungal activity against wood decaying fungi, showing potential to substitute the current wood preservatives[101] while further tests are still required. However, their ecotoxicity is very variable and while some are less toxic than current wood preservatives, other pyrolysis liquids have shown high ecotoxicity, what may cause detrimental effects in the environment.[102]

- Pyrolysis of tobacco, paper, and additives, in cigarettes and other products, generates many volatile products (including nicotine, carbon monoxide, and tar) that are responsible for the aroma and negative health effects of smoking. Similar considerations apply to the smoking of marijuana and the burning of incense products and mosquito coils.

- Pyrolysis occurs during the incineration of trash, potentially generating volatiles that are toxic or contribute to air pollution if not completely burned.

- Laboratory or industrial equipment sometimes gets fouled by carbonaceous residues that result from coking, the pyrolysis of organic products that come into contact with hot surfaces.

PAHs generation

[edit]Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) can be generated from the pyrolysis of different solid waste fractions,[12] such as hemicellulose, cellulose, lignin, pectin, starch, polyethylene (PE), polystyrene (PS), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and polyethylene terephthalate (PET). PS, PVC, and lignin generate significant amount of PAHs. Naphthalene is the most abundant PAH among all the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.[103]

When the temperature is increased from 500 to 900 °C, most PAHs increase. With increasing temperature, the percentage of light PAHs decreases and the percentage of heavy PAHs increases.[104][105]

Study tools

[edit]Thermogravimetric analysis

[edit]Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) is one of the most common techniques to investigate pyrolysis with no limitations of heat and mass transfer. The results can be used to determine mass loss kinetics.[5][19][6][37][73] Activation energies can be calculated using the Kissinger method or peak analysis-least square method (PA-LSM).[6][37]

TGA can couple with Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and mass spectrometry. As the temperature increases, the volatiles generated from pyrolysis can be measured.[106][82]

Macro-TGA

[edit]In TGA, the sample is loaded first before the increase of temperature, and the heating rate is low (less than 100 °C min−1). Macro-TGA can use gram-scale samples to investigate the effects of pyrolysis with mass and heat transfer.[6][107]

Pyrolysis–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry

[edit]Pyrolysis mass spectrometry (Py-GC-MS) is an important laboratory procedure to determine the structure of compounds.[108][109]

Machine learning

[edit]In recent years, machine learning has attracted significant research interest in predicting yields, optimizing parameters, and monitoring pyrolytic processes.[110][111]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "Pyrolysis". doi:10.1351/goldbook.P04961

- ^ Devi, Mamta; Rawat, Sachin; Sharma, Swati (23 November 2020). "A comprehensive review of the pyrolysis process: from carbon nanomaterial synthesis to waste treatment". Oxford Open Materials Science. 1 (1) itab014. doi:10.1093/oxfmat/itab014.

- ^ "What Is Pyrolysis?". Eastern Regional Research Center: Wyndmoor, PA. USDA. 31 January 2025. Retrieved 6 March 2025.

- ^ "Burning of wood". InnoFireWood's website. Archived from the original on 2010-02-09. Retrieved 2010-02-06.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zhou, Hui; Long, YanQiu; Meng, AiHong; Li, QingHai; Zhang, YanGuo (August 2013). "The pyrolysis simulation of five biomass species by hemi-cellulose, cellulose and lignin based on thermogravimetric curves". Thermochimica Acta. 566: 36–43. Bibcode:2013TcAc..566...36Z. doi:10.1016/j.tca.2013.04.040.

- ^ a b c d e f Combustible Solid Waste Thermochemical Conversion. Springer Theses. 2017. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-3827-3. ISBN 978-981-10-3826-6.[page needed]

- ^ a b BASF. "BASF researchers working on fundamentally new, low-carbon production processes, Methane Pyrolysis". United States Sustainability. BASF. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ Kramer, Cory A.; Loloee, Reza; Wichman, Indrek S.; Ghosh, Ruby N. (2009). "Time Resolved Measurements of Pyrolysis Products from Thermoplastic Poly-Methyl-Methacrylate (PMMA)". Volume 3: Combustion Science and Engineering. pp. 99–105. doi:10.1115/IMECE2009-11256. ISBN 978-0-7918-4376-5.

- ^ Ramin, Leyla; Assadi, M. Hussein N.; Sahajwalla, Veena (November 2014). "High-density polyethylene degradation into low molecular weight gases at 1823K: An atomistic simulation". Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis. 110: 318–321. arXiv:2204.08253. Bibcode:2014JAAP..110..318R. doi:10.1016/j.jaap.2014.09.022.

- ^ Jones, Jim. "Mechanisms of pyrolysis" (PDF). Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ George, Anthe; Turn, Scott Q.; Morgan, Trevor James (26 August 2015). "Fast Pyrolysis Behavior of Banagrass as a Function of Temperature and Volatiles Residence Time in a Fluidized Bed Reactor". PLOS ONE. 10 (8) e0136511. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1036511M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0136511. PMC 4550300. PMID 26308860.

- ^ a b Zhou, Hui; Wu, Chunfei; Meng, Aihong; Zhang, Yanguo; Williams, Paul T. (November 2014). "Effect of interactions of biomass constituents on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) formation during fast pyrolysis" (PDF). Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis. 110: 264–269. Bibcode:2014JAAP..110..264Z. doi:10.1016/j.jaap.2014.09.007.

- ^ Astrup, Thomas; Bilitewski, Bernd (2010). "Pyrolysis and Gasification". Solid Waste Technology & Management. pp. 502–512. doi:10.1002/9780470666883.ch33. ISBN 978-0-470-66688-3.

- ^ Wang, Xifan; Schmidt, Franziska; Hanaor, Dorian; Kamm, Paul H.; Li, Shuang; Gurlo, Aleksander (May 2019). "Additive manufacturing of ceramics from preceramic polymers: A versatile stereolithographic approach assisted by thiol-ene click chemistry". Additive Manufacturing. 27: 80–90. arXiv:1905.02060. doi:10.1016/j.addma.2019.02.012.

- ^ a b c Jenkins, R.W.; Sutton, A.D.; Robichaud, D.J. (2016). "Pyrolysis of Biomass for Aviation Fuel". Biofuels for Aviation. pp. 191–215. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-804568-8.00008-1. ISBN 978-0-12-804568-8.

- ^ a b Tripathi, Manoj; Sahu, J.N.; Ganesan, P. (March 2016). "Effect of process parameters on production of biochar from biomass waste through pyrolysis: A review". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 55: 467–481. Bibcode:2016RSERv..55..467T. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2015.10.122.

- ^ Koller, Johann; Baumer, Ursula; Kaup, Yoka; Schmid, Mirjam; Weser, Ulrich (October 2003). "Analysis of a pharaonic embalming tar". Nature. 425 (6960): 784. doi:10.1038/425784a. PMID 14574400.

- ^ E. Fiedler; G. Grossmann; D. B. Kersebohm; G. Weiss; Claus Witte (2005). "Methanol". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ a b c Zhou, Hui; Long, YanQiu; Meng, AiHong; Li, QingHai; Zhang, YanGuo (April 2015). "Thermogravimetric characteristics of typical municipal solid waste fractions during co-pyrolysis". Waste Management. 38: 194–200. Bibcode:2015WaMan..38..194Z. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2014.09.027. PMID 25680236.

- ^ Hafting, Finn K.; Kulas, Daniel; Michels, Etienne; Chipkar, Sarvada; Wisniewski, Stefan; Shonnard, David; Pearce, Joshua M. (2023). "Modular Open-Source Design of Pyrolysis Reactor Monitoring and Control Electronics". Electronics. 12 (24): 4893. doi:10.3390/electronics12244893.

- ^ Rollinson, Andrew N. (July 2018). "Fire, explosion and chemical toxicity hazards of gasification energy from waste". Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries. 54: 273–280. Bibcode:2018JLPPI..54..273R. doi:10.1016/j.jlp.2018.04.010.

- ^ Hedlund Frank Huess (May 2023). "Inherent Hazards and Limited Regulatory Oversight in the Waste Plastic Recycling Sector Repeat Explosion at Pyrolysis Plant". Chemical Engineering Transactions. 99: 241–246. doi:10.3303/CET2399041.

- ^ Razdan RK (January 1981). "The Total Synthesis of Cannabinoids.". In ApSimon J (ed.). Total Synthesis of Natural Products. Vol. 4. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 185–262. doi:10.1002/9780470129678.ch2. ISBN 978-0-470-12953-1.

- ^ Czégény Z, Nagy G, Babinszki B, Bajtel Á, Sebestyén Z, Kiss T, Csupor-Löffler B, Tóth B, Csupor D (April 2021). "CBD, a precursor of THC in e-cigarettes". Scientific Reports. 11 (1) 8951. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.8951C. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-88389-z. PMC 8076212. PMID 33903673.

- ^ a b Kaplan, Ryan (Fall 2011). "Pyrolysis: Biochar, Bio-Oil and Syngas from Wastes". users.humboldt.edu. Humboldt University. Archived from the original (Course notes for Environmental Resources Engineering 115) on 3 April 2014. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ a b "What is Caramelization?". www.scienceofcooking.com. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ Brimm, Courtney (7 November 2011). "Cooking with Chemistry: What is Caramelization?". Common Sense Science. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ Sood, A (December 2012). "Indoor fuel exposure and the lung in both developing and developed countries: an update". Clinics in Chest Medicine. 33 (4): 649–65. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2012.08.003. PMC 3500516. PMID 23153607.

- ^ a b "SMOKELESS zones". British Medical Journal. 2 (4840): 818–20. 10 October 1953. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4840.818. PMC 2029724. PMID 13082128.

- ^ "Two-stage incinerator, United States Patent 3881430". www.freepatentsonline.com. 6 May 1975. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ Ludwig Briesemeister; Andreas Geißler; Stefan Halama; Stephan Herrmann; Ulrich Kleinhans; Markus Steibel; Markus Ulbrich; Alan W. Scaroni; M. Rashid Khan; Semih Eser; Ljubisa R. Radovic (2002). "Coal Pyrolysis". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. pp. 1–44. doi:10.1002/14356007.a07_245.pub2. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ Lehmann, Johannes. "Biochar: the new frontier". Archived from the original on 2008-06-18. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- ^ Ratner, Buddy D. (2004). Pyrolytic carbon. In Biomaterials science: an introduction to materials in medicine Archived 2014-06-26 at the Wayback Machine. Academic Press. pp. 171–180. ISBN 0-12-582463-7.

- ^ Evans, G. "Liquid Transport Biofuels – Technology Status Report" Archived September 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, "National Non-Food Crops Centre", 14-04-08. Retrieved on 2009-05-05.

- ^ "Biomass Feedstock for Slow Pyrolysis". BEST Pyrolysis, Inc. website. BEST Energies, Inc. Archived from the original on 2012-01-02. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- ^ a b Zhao, Ming; Wang, Fan; Fan, Yiran; Raheem, Abdul; Zhou, Hui (March 2019). "Low-temperature alkaline pyrolysis of sewage sludge for enhanced H2 production with in-situ carbon capture". International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 44 (16): 8020–8027. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.02.040.

- ^ a b c Zhou, Hui; Long, Yanqiu; Meng, Aihong; Chen, Shen; Li, Qinghai; Zhang, Yanguo (2015). "A novel method for kinetics analysis of pyrolysis of hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin in TGA and macro-TGA". RSC Advances. 5 (34): 26509–26516. Bibcode:2015RSCAd...526509Z. doi:10.1039/C5RA02715B.

- ^ "Pyrolysis and Other Thermal Processing". US DOE. Archived from the original on 2007-08-14.

- ^ Ramirez, Jerome; Brown, Richard; Rainey, Thomas (1 July 2015). "A Review of Hydrothermal Liquefaction Bio-Crude Properties and Prospects for Upgrading to Transportation Fuels". Energies. 8 (7): 6765–6794. doi:10.3390/en8076765.

- ^ Marshall, A. T. & Morris, J. M. (2006) A Watery Solution and Sustainable Energy Parks Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine, CIWM Journal, pp. 22–23

- ^ Westerhof, Roel Johannes Maria (2011). Refining fast pyrolysis of biomass. Thermo-Chemical Conversion of Biomass (Thesis). University of Twente. Archived from the original on 2013-06-17. Retrieved 2012-05-30.

- ^ Upham, D. Chester; Agarwal, Vishal; Khechfe, Alexander; Snodgrass, Zachary R.; Gordon, Michael J.; Metiu, Horia; McFarland, Eric W. (17 November 2017). "Catalytic molten metals for the direct conversion of methane to hydrogen and separable carbon". Science. 358 (6365): 917–921. Bibcode:2017Sci...358..917U. doi:10.1126/science.aao5023. PMID 29146810.

- ^ Timmerberg, Sebastian; Kaltschmitt, Martin; Finkbeiner, Matthias (September 2020). "Hydrogen and hydrogen-derived fuels through methane decomposition of natural gas – GHG emissions and costs". Energy Conversion and Management: X. 7 100043. Bibcode:2020ECMX....700043T. doi:10.1016/j.ecmx.2020.100043. hdl:11420/6245.

- ^ Lumbers, Brock (20 August 2020). Mathematical Modelling and Simulation of Catalyst Deactivation for the Continuous Thermo-Catalytic Decomposition of Methane (Thesis). Rhine-Waal University of Applied Sciences. pp. 12–13. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ Fialka, John. "Energy Department Looks to Boost Hydrogen Fuel for Big Trucks". E&E News. Scientific American. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ^ CCJ News (13 August 2020). "How fuel cell trucks produce electric power and how they're fueled". CCJ News. Commercial Carrier Journal. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ Toyota. "Hydrogen Fuel-Cell Class 8 Truck". Hydrogen-Powered Truck Will Offer Heavy-Duty Capability and Clean Emissions. Toyota. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ Colias, Mike (26 October 2020). "Auto Makers Shift Their Hydrogen Focus to Big Rigs". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ Honda. "Honda Fuel-Cell Clarity". Clarity Fuel Cell. Honda. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ GE Turbines. "Hydrogen fueled power turbines". Hydrogen fueled gas turbines. General Electric. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ Solar Turbines. "Hydrogen fueled power turbines". Power From Hydrogen Gas For Carbon Reduction. Solar Turbines. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ Crolius, Stephen H. (27 January 2017). "Methane to Ammonia via Pyrolysis". Ammonia Energy Association. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ Pérez, Jorge. "CEMEX successfully deploys hydrogen-based ground-breaking cement manufacturing technology". www.cemex.com. CEMEX, S.A.B. de C.V. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ Cartwright, Jon. "The reaction that would give us clean fossil fuels forever". NewScientist. New Scientist Ltd. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ Karlsruhe Institute of Technology. "Hydrogen from methane without CO2 emissions". Phys.Org. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ "Successful Demonstration Program Underpins Monolith Materials' Commercialization Plans - Zeton". Zeton Inc. 2019-05-28. Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- ^ "Monolith". monolith-corp.com. Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- ^ "DOE backs Neb. hydrogen, carbon black project with $1B loan guarantee". www.spglobal.com. Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- ^ "NW Natural to Partner with Modern Electron on Exciting Pilot Project to Turn Methane into Clean Hydrogen and Solid Carbon". The Wall Street Journal. 2022-07-27. Retrieved 2022-08-24.

- ^ Stiffler, Lisa (2022-04-26). "Cut the BS: This startup is converting cow manure into clean-burning hydrogen fuel". GeekWire. Retrieved 2022-08-24.

- ^ Fernandez, Sonia (21 November 2017). "Researchers develop potentially low-cost, low-emissions technology that can convert methane without forming CO2". phys.org (Press release). University of California - Santa Barbara.

- ^ Gusev, Alexander. "KITT/IASS - Producing CO2 Free Hydrogen From Natural Gas For Energy Usage". European Energy Innovation. Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ "Methane pyrolysis process uses renewable electricity split CH4 into H2 and carbon-black". December 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ "Delay to Reactor Fabrication" (Press release). Hazer Group. 10 December 2021.

- ^ "Hazer advances ENGIE collaboration for facility in France" (Press release). Hazer Group.

- ^ "Hazer Signs MOU with Chubu Electric & Chiyoda" (Press release). Hazer Group.

- ^ "Hazer Group – Investor Presentation | hazergroup.com.au". Retrieved 2023-05-23.[non-primary source needed]

- ^ "Burrard Hazer Hydrogen Project Announcement | hazergroup.com.au". Retrieved 2023-05-23.[non-primary source needed]

- ^ "C-Zero | Decarbonizing Natural Gas". C-Zero. Retrieved 2023-05-23.

- ^ "C-Zero Closes $34 Million Financing Round Led by SK Gas to Build Natural Gas Decarbonization Pilot". C-Zero. 2022-06-16. Retrieved 2023-05-23.

- ^ "Interview Andreas Bode". www.basf.com. Retrieved 2023-05-23.

- ^ Zimmermann, Heinz; Walzl, Roland (2009). "Ethylene". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a10_045.pub3. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ a b Zhou, Hui; Long, YanQiu; Meng, AiHong; Li, QingHai; Zhang, YanGuo (January 2015). "Interactions of three municipal solid waste components during co-pyrolysis". Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis. 111: 265–271. Bibcode:2015JAAP..111..265Z. doi:10.1016/j.jaap.2014.08.017.

- ^ Kaminsky, Walter (2000). "Plastics, Recycling". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a21_057. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ N.J. Themelis et al. "Energy and Economic Value of Nonrecyclable Plastics and Municipal Solid Wastes that are Currently Landfilled in the Fifty States" Columbia University Earth Engineering Center Archived 2014-05-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Plastic to Oil Machine, A\J – Canada's Environmental Voice". Alternativesjournal.ca. 2016-12-07. Archived from the original on 2015-09-09. Retrieved 2016-12-16.

- ^ ผศ.ดร.ศิริรัตน์ จิตการค้า, "ไพโรไลซิสยางรถยนต์หมดสภาพ : กลไกการผลิตน้ำมันเชื้อเพลิงคุณภาพสูง"วิทยาลัยปิโตรเลียมและปิโตรเคมี จุฬาลงกรณ์มหาวิทยาลัย (in Thai) Jidgarnka, S. "Pyrolysis of Expired Car Tires: Mechanics of Producing High Quality Fuels" Archived 2015-02-20 at the Wayback Machine. Chulalongkorn University Department of Petrochemistry

- ^ Roy, C.; Chaala, A.; Darmstadt, H. (1999). "The vacuum pyrolysis of used tires". Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis. 51 (1–2): 201–221. doi:10.1016/S0165-2370(99)00017-0.

- ^ Martínez, Juan Daniel; Puy, Neus; Murillo, Ramón; García, Tomás; Navarro, María Victoria; Mastral, Ana Maria (July 2013). "Waste tyre pyrolysis – A review". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 23: 179–213. Bibcode:2013RSERv..23..179M. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2013.02.038.

- ^ Choi, Gyung-Goo; Jung, Su-Hwa; Oh, Seung-Jin; Kim, Joo-Sik (July 2014). "Total utilization of waste tire rubber through pyrolysis to obtain oils and CO2 activation of pyrolysis char". Fuel Processing Technology. 123: 57–64. doi:10.1016/j.fuproc.2014.02.007.

- ^ Ringer, M.; Putsche, V.; Scahill, J. (2006). Large-Scale Pyrolysis Oil Production: A Technology Assessment and Economic Analysis (Report). doi:10.2172/894989. OSTI 894989.

- ^ a b Zhao, Ming; Memon, Muhammad Zaki; Ji, Guozhao; Yang, Xiaoxiao; Vuppaladadiyam, Arun K.; Song, Yinqiang; Raheem, Abdul; Li, Jinhui; Wang, Wei; Zhou, Hui (April 2020). "Alkali metal bifunctional catalyst-sorbents enabled biomass pyrolysis for enhanced hydrogen production". Renewable Energy. 148: 168–175. Bibcode:2020REne..148..168Z. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2019.12.006.

- ^ Leif, Dan (2021-11-03). "Igneo targets low-grade scrap electronics with $85M plant". resource-recycling.com. Retrieved 2021-11-28.

- ^ Romani, Alessia; Kulas, Daniel; Curro, Joseph; Shonnard, David R.; Pearce, Joshua M. (May 2025). "Recycled filtered contaminants from liquid-fed pyrolysis as novel building composite material". Journal of Building Engineering. 102 112025. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2025.112025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Lee, Taewoo; Jung, Sungyup; Lin, Kun-Yi Andrew; Tsang, Yiu Fai; Kwon, Eilhann E. (January 2021). "Mitigation of harmful chemical formation from pyrolysis of tobacco waste using CO2". Journal of Hazardous Materials. 401 123416. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123416. PMID 32763706.

- ^ Lahijani, Pooya; Zainal, Zainal Alimuddin; Mohammadi, Maedeh; Mohamed, Abdul Rahman (January 2015). "Conversion of the greenhouse gas CO

2 to the fuel gas CO via the Boudouard reaction: A review". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 41: 615–632. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2014.08.034. - ^ Hunt, Jacob; Ferrari, Anthony; Lita, Adrian; Crosswhite, Mark; Ashley, Bridgett; Stiegman, A. E. (27 December 2013). "Microwave-Specific Enhancement of the Carbon–Carbon Dioxide (Boudouard) Reaction". The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 117 (51): 26871–26880. doi:10.1021/jp4076965.

- ^ Heffungs, Udo (June 2010). "Effective Spinneret Cleaning". Fiber Journal. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d Mainord, Kenneth (September 1994). "Cleaning with Heat: Old Technology with a Bright New Future" (PDF). Pollution Prevention Regional Information Center. The Magazine of Critical Cleaning Technology. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ^ a b c "A Look at Thermal Cleaning Technology". ThermalProcessing.org. Process Examiner. 14 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ^ Davis, Gary; Brown, Keith (April 1996). "Cleaning Metal Parts and Tooling" (PDF). Pollution Prevention Regional Information Center. Process Heating. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ^ Schwing, Ewald; Uhrner, Horst (7 October 1999). "Method for removing polymer deposits which have formed on metal or ceramic machine parts, equipment and tools". Espacenet. European Patent Office. Archived from the original on 31 December 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ^ Staffin, Herbert Kenneth; Koelzer, Robert A. (28 November 1974). "Cleaning objects in hot fluidised bed – with neutralisation of resultant acidic gas esp. by alkaline metals cpds". Espacenet. European Patent Office. Archived from the original on 31 December 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ^ Dwan, Thomas S. (2 September 1980). "Process for vacuum pyrolysis removal of polymers from various objects". Espacenet. European Patent Office. Archived from the original on 31 December 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ "Vacuum pyrolysis systems". thermal-cleaning.com. Archived from the original on 15 February 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ "Paint Stripping: Reducing Waste and Hazardous Material". Minnesota Technical Assistance Program. University of Minnesota. July 2008. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ^ Chemistry of the Elements. 1997. doi:10.1016/C2009-0-30414-6. ISBN 978-0-7506-3365-9.[page needed]

- ^ Pingali, Kalyana C.; Rockstraw, David A.; Deng, Shuguang (October 2005). "Silver Nanoparticles from Ultrasonic Spray Pyrolysis of Aqueous Silver Nitrate". Aerosol Science and Technology. 39 (10): 1010–1014. Bibcode:2005AerST..39.1010P. doi:10.1080/02786820500380255.

- ^ Song, Y. L.; Tsai, S. C.; Chen, C. Y.; Tseng, T. K.; Tsai, C. S.; Chen, J. W.; Yao, Y. D. (October 2004). "Ultrasonic Spray Pyrolysis for Synthesis of Spherical Zirconia Particles". Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 87 (10): 1864–1871. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.2004.tb06332.x.

- ^ Hamedani, Hoda Amani (December 2008). Investigation of deposition parameters in ultrasonic spray pyrolysis for fabrication of solid oxide fuel cell cathode (Thesis). hdl:1853/26670.

- ^ Barbero-López, Aitor; Chibily, Soumaya; Tomppo, Laura; Salami, Ayobami; Ancin-Murguzur, Francisco Javier; Venäläinen, Martti; Lappalainen, Reijo; Haapala, Antti (March 2019). "Pyrolysis distillates from tree bark and fibre hemp inhibit the growth of wood-decaying fungi". Industrial Crops and Products. 129: 604–610. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.12.049.

- ^ Barbero-López, Aitor; Akkanen, Jarkko; Lappalainen, Reijo; Peräniemi, Sirpa; Haapala, Antti (January 2021). "Bio-based wood preservatives: Their efficiency, leaching and ecotoxicity compared to a commercial wood preservative". Science of the Total Environment. 753 142013. Bibcode:2021ScTEn.75342013B. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142013. PMID 32890867.

- ^ Zhou, Hui; Wu, Chunfei; Onwudili, Jude A.; Meng, Aihong; Zhang, Yanguo; Williams, Paul T. (February 2015). "Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) formation from the pyrolysis of different municipal solid waste fractions" (PDF). Waste Management. 36: 136–146. Bibcode:2015WaMan..36..136Z. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2014.09.014. PMID 25312776.

- ^ Zhou, Hui; Wu, Chunfei; Onwudili, Jude A.; Meng, Aihong; Zhang, Yanguo; Williams, Paul T. (16 October 2014). "Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Formation from the Pyrolysis/Gasification of Lignin at Different Reaction Conditions". Energy & Fuels. 28 (10): 6371–6379. Bibcode:2014EnFue..28.6371Z. doi:10.1021/ef5013769.

- ^ Zhou, Hui; Wu, Chunfei; Onwudili, Jude A.; Meng, Aihong; Zhang, Yanguo; Williams, Paul T. (April 2016). "Influence of process conditions on the formation of 2–4 ring polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from the pyrolysis of polyvinyl chloride" (PDF). Fuel Processing Technology. 144: 299–304. Bibcode:2016FuPrT.144..299Z. doi:10.1016/j.fuproc.2016.01.013.

- ^ Zhou, Hui; Meng, AiHong; Long, YanQiu; Li, QingHai; Zhang, YanGuo (July 2014). "Interactions of municipal solid waste components during pyrolysis: A TG-FTIR study". Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis. 108: 19–25. Bibcode:2014JAAP..108...19Z. doi:10.1016/j.jaap.2014.05.024.

- ^ Long, Yanqiu; Zhou, Hui; Meng, Aihong; Li, Qinghai; Zhang, Yanguo (September 2016). "Interactions among biomass components during co-pyrolysis in (macro)thermogravimetric analyzers". Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering. 33 (9): 2638–2643. doi:10.1007/s11814-016-0102-x.

- ^ Goodacre, Royston; Kell, Douglas B (February 1996). "Pyrolysis mass spectrometry and its applications in biotechnology". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 7 (1): 20–28. doi:10.1016/S0958-1669(96)80090-5. PMID 8791308.

- ^ Peacock, Patricia M.; McEwen, Charles N. (1 June 2006). "Mass Spectrometry of Synthetic Polymers". Analytical Chemistry. 78 (12): 3957–3964. doi:10.1021/ac0606249. PMID 16771534.

- ^ Wang, Zhengxin; Peng, Xinggan; Xia, Ao; Shah, Akeel A.; Huang, Yun; Zhu, Xianqing; Zhu, Xun; Liao, Qiang (January 2022). "The role of machine learning to boost the bioenergy and biofuels conversion". Bioresource Technology. 343 126099. Bibcode:2022BiTec.34326099W. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2021.126099. PMID 34626766.

- ^ Akinpelu, David Akorede; Adekoya, Oluwaseun A.; Oladoye, Peter Olusakin; Ogbaga, Chukwuma C.; Okolie, Jude A. (September 2023). "Machine learning applications in biomass pyrolysis: From biorefinery to end-of-life product management". Digital Chemical Engineering. 8 100103. doi:10.1016/j.dche.2023.100103.

External links

[edit]- Biddy, Mary; Dutta, Abhijit; Jones, Susanne; Meyer, Aye (2013). In-Situ Catalytic Fast Pyrolysis Technology Pathway (Report). doi:10.2172/1076660.

Pyrolysis

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Principles

Pyrolysis is a thermochemical process involving the thermal decomposition of organic materials at elevated temperatures in the absence of oxygen or other oxidizing agents.[1][2] This decomposition breaks down complex molecules into simpler compounds, primarily yielding solid char, liquid bio-oil, and non-condensable gases such as syngas.[7] The process occurs under inert atmospheres like nitrogen or argon to prevent combustion, typically at temperatures ranging from 400°C to over 800°C depending on the feedstock and desired products.[8][9] The fundamental principle of pyrolysis relies on heat-induced cleavage of covalent bonds within the feedstock, leading to endothermic reactions that favor depolymerization, fragmentation, and secondary cracking.[1] Primary products form through initial devolatilization, where volatile components are released, followed by potential secondary reactions that alter yields based on residence time and temperature.[7] Key parameters influencing the process include heating rate, which affects product distribution—slow pyrolysis maximizes char (up to 35% yield), while fast pyrolysis prioritizes liquids (50-75% bio-oil)—and pressure, generally atmospheric but variable in specialized applications.[2] Pyrolysis kinetics follow Arrhenius behavior, with activation energies typically 100-250 kJ/mol for biomass, governed by multi-step mechanisms involving parallel and consecutive reactions.[10] As the initial stage in thermochemical conversion pathways like gasification and combustion, pyrolysis enables resource recovery from biomass, plastics, and wastes without external oxygen, promoting energy efficiency and reducing emissions compared to oxidative processes.[7] The inert environment ensures that decomposition proceeds via free radical or ionic pathways rather than oxidation, preserving carbon structures in char while volatilizing hydrogen-rich fractions.[8] Empirical data from thermogravimetric analysis confirm staged weight loss: dehydration below 200°C, primary decomposition at 200-500°C, and char formation above 500°C.[11]Terminology

Pyrolysis is defined as the thermal decomposition of materials into simpler compounds through the application of heat in an inert atmosphere, without the presence of oxygen, often occurring at temperatures above 400°C.[12] This process, also termed thermolysis, involves the breaking of covalent bonds in organic matter, leading to the formation of volatile products and a solid residue.[13] For biomass, pyrolysis is typically conducted at or above 500°C to ensure significant decomposition.[2] The primary outputs of pyrolysis are categorized as char, tar (or pyrolysis oil), and non-condensable gases. Char denotes the carbonaceous solid residue left after volatilization, consisting mainly of fixed carbon with minimal volatiles, akin to charcoal in composition.[14] Tar refers to the condensable liquid fraction, comprising complex hydrocarbons, phenolic compounds, and oxygenated species derived from the breakdown of polymers or biomass.[15] Non-condensable gases, collectively known as syngas or synthesis gas, include hydrogen (H₂), carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄), and light hydrocarbons that remain in the vapor phase post-reaction.[16] Related terms include carbonization, which specifies slow pyrolysis optimized for maximizing char yield through prolonged heating at moderate temperatures (around 400–600°C), and destructive distillation, an older designation for the pyrolytic separation of volatile components from solids like coal or wood.[3] These distinctions arise from variations in heating rates, residence times, and final temperatures, influencing product distribution without altering the core inert-environment requirement.[17]Types of Pyrolysis

Pyrolysis processes are primarily classified by heating rate, reaction temperature, residence time, and pressure conditions, which determine the relative yields of solid char, liquid bio-oil, and non-condensable gases from organic feedstocks.[18] Slow pyrolysis prioritizes char production through prolonged thermal decomposition, while fast and flash variants emphasize liquids or gases via rapid heating to minimize secondary cracking.[19] These distinctions arise from kinetic control over primary decomposition pathways, where slower rates allow char stabilization and faster rates favor volatile release before repolymerization.[18] Slow pyrolysis, also termed conventional or carbonization pyrolysis, employs low heating rates of 0.1–1 °C/s at temperatures of 350–550 °C with vapor residence times exceeding 5 minutes, yielding up to 35% char, 30% oil, and 35% gas from biomass.[20] This method, historically used for charcoal production, maximizes solid residue by promoting aromatization and carbon enrichment in the solid phase while limiting tar formation through extended exposure.[21] Fixed-bed reactors are common, operating under inert atmospheres to sustain yields consistent across lignocellulosic materials at scales from laboratory to industrial.[22] Fast pyrolysis accelerates decomposition with heating rates of 10–200 °C/s at 450–550 °C and short residence times of 0.5–5 seconds, optimizing liquid bio-oil yields of 50–75% by quenching vapors to prevent char formation or gas evolution.[18] Fluidized-bed or circulating-bed reactors facilitate rapid heat transfer, as demonstrated in biomass trials yielding oils with 15–20% oxygen content suitable for upgrading to fuels.[19] The process's efficiency stems from minimizing intraparticle heat gradients, though bio-oil instability requires downstream hydrotreating.[23] Flash pyrolysis, or ultrapyrolysis, uses extreme heating rates above 1000 °C/s at 600–1000 °C with residence times under 0.5 seconds, prioritizing gas production (up to 75%) over liquids due to intensified cracking of primary vapors.[24] Ablative or entrained-flow reactors enable this for finely ground feedstocks, as evidenced in studies on agricultural residues where syngas yields exceed 60 vol%.[18] Its high severity suits hydrogen-rich gas generation but demands precise control to avoid equipment fouling from rapid coke deposition. Specialized variants adapt standard pyrolysis under modified conditions. Vacuum pyrolysis reduces pressure to 10–100 Pa, lowering decomposition temperatures by 50–100 °C and enabling selective volatilization of high-boiling compounds without atmospheric interference, as applied in tire recycling for 40–50% oil recovery.[25] Hydropyrolysis incorporates hydrogen pressure (1–10 MPa) and often catalysts at 400–500 °C to stabilize radicals and boost hydrocarbon liquids, yielding naphtha-range products from biomass at efficiencies 20–30% higher than non-hydrogen processes.[26] These modifications enhance product quality but increase operational complexity and energy input compared to conventional types.[27]Chemical Processes and Mechanisms

General Processes

Pyrolysis entails the thermochemical decomposition of organic materials at elevated temperatures, typically 300–800 °C, in an oxygen-limited or inert environment, yielding solid char, condensable liquids such as bio-oil or tar, and non-condensable gases like syngas.[28] This endothermic process breaks down complex macromolecules through bond scission without combustion, distinguishing it from oxidation pathways.[19] The core chemical processes divide into primary and secondary reactions. Primary reactions involve initial thermal degradation within the solid or nascent vapor phase, encompassing depolymerization of polymers into monomers, fragmentation into smaller radicals, dehydration, decarboxylation, and char formation via cross-linking.[19] These yield unstable primary volatiles, including aldehydes, ketones, acids, and hydrocarbons.[28] Secondary reactions follow, featuring further cracking of volatiles to lighter gases, repolymerization to heavier tars, or interactions with char surfaces, modulated by factors like vapor residence time and temperature.[28] Higher temperatures and longer residence times favor secondary cracking, increasing gas yields over liquids.[19] Reaction kinetics often follow free radical chain mechanisms, initiated by homolytic cleavage of C-C and C-O bonds, propagated by hydrogen abstraction and beta-scission, and terminated by recombination or disproportionation.[29] Product distribution depends on feedstock composition, with biomass components decomposing sequentially—hemicellulose at lower temperatures (~200–300 °C), cellulose around 300–400 °C, and lignin across a wider range (~150–500 °C)—though analogous bond-breaking applies to other organics like plastics.[28]Reaction Mechanisms and Kinetics

Pyrolysis reactions predominantly follow free radical chain mechanisms, initiated by the thermal homolysis of covalent bonds in organic molecules at temperatures typically above 400°C, generating primary radicals that propagate through hydrogen abstraction, β-scission, and molecular rearrangement to yield volatile products, char, and secondary radicals, with termination via disproportionation or recombination.[30][31] In hydrocarbon pyrolysis, such as in fossil fuels or plastics, the process emphasizes C-C and C-H bond cleavage, where initiation rates increase exponentially with temperature, leading to chain branching that amplifies decomposition efficiency.[30] For biomass, mechanisms incorporate concurrent depolymerization of cellulose (via glycosidic bond rupture forming levoglucosan intermediates), hemicellulose fragmentation, and lignin cracking, all underpinned by radical-mediated dehydration and decarboxylation, though some concerted unimolecular pathways occur at lower severities.[32][33] Kinetic analysis of pyrolysis employs the Arrhenius equation, , where activation energies () vary by feedstock and reaction stage, often spanning 150–250 kJ/mol for lignocellulosic biomass as determined by isoconversional methods like Friedman (differential) or Kissinger-Akahira-Sunose (integral), which reveal dependence on conversion (α) due to evolving reactive sites.[34][35] Distributed activation energy models (DAEM) effectively simulate the polydispersity of bond energies, assuming parallel reactions with Gaussian-distributed , yielding pre-exponential factors (A) on the order of 10^{10}–10^{15} s^{-1} for primary devolatilization.[36][37] In hydrocarbon systems, global kinetic models simplify to nth-order reactions with lower (e.g., 200–220 kJ/mol for alkane cracking), while detailed mechanisms incorporate hundreds of elementary steps for species-specific predictions.[38][39] Process control in pyrolysis relies on these kinetics, with heating rates influencing radical propagation dominance—slow pyrolysis favors char formation via cross-linking, whereas fast pyrolysis (rates >1000°C/s) minimizes secondary cracking for higher liquid yields.[29] Thermodynamic parameters, such as positive ΔH (endothermic) and decreasing ΔG with temperature, confirm feasibility, but kinetic barriers necessitate precise temperature profiles to optimize product distribution.[40] Experimental validation via thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) coupled with evolved gas analysis underscores model accuracy, though challenges persist in scaling microscale kinetics to reactors due to heat/mass transfer limitations.[41][42]Historical Development

Ancient and Pre-Industrial Uses

Charcoal production through pyrolysis, involving the thermal decomposition of wood in low-oxygen environments, represents one of the earliest documented applications of the process. Archaeological findings suggest deliberate charcoal manufacturing dates to the Neolithic period, around 10,000–5,000 BCE, where wood was carbonized in pits or mounds to produce a high-energy fuel superior to raw wood.[43] This method yielded charcoal with higher calorific value due to the removal of volatiles, enabling more efficient combustion for heating and early metallurgy.[44] In prehistoric contexts, charcoal served as a pigment for cave art, with evidence from sites like the Niaux Cave in France dating to approximately 17,000–13,000 BCE, where charred wood residues indicate controlled pyrolysis for black pigments.[45] By the Bronze Age (circa 3000–1200 BCE), pyrolysis scaled for metalworking; vast quantities of charcoal fueled smelting furnaces in regions like the Mediterranean and Near East, as wood shortages prompted systematic forest management for coppicing.[46] Ancient civilizations refined pyrolysis techniques for diverse uses. In Iron Age Europe (circa 1200–500 BCE), rectangular pit kilns facilitated charcoal production for iron smelting, evidenced by kiln remnants in the Low Countries.[47] Roman-era operations similarly employed covered stacks to minimize oxygen, producing charcoal for forges, lime kilns, and even military applications like Greek fire precursors.[47] In Asia, Chinese records from the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE) describe pyrolysis of hardwood for ink and fuel, while Scandinavian birch tar—derived from wood pyrolysis—was used for waterproofing and adhesives by 500 BCE.[46] Pre-industrial pyrolysis extended to biochar-like soil amendments, with Amazonian terra preta soils containing pyrogenic carbon from 500 BCE to 1500 CE, enhancing fertility through stable carbon residues.[48] These practices persisted into the early modern era using mound kilns, underscoring pyrolysis's role in sustaining agrarian and extractive economies before mechanized alternatives.[49]Early Industrial Applications (19th-early 20th Century)

In the 19th century, pyrolysis found its principal industrial application in the production of coke from bituminous coal, essential for fueling blast furnaces in the burgeoning iron and steel sectors. This process involved heating coal to 900–1100°C in low-oxygen beehive ovens, decomposing it into a porous carbon residue while driving off volatile matter as gases and tars. Beehive ovens, developed in the mid-19th century, enabled batch processing on a large scale; for instance, in the Pittsburgh region, their numbers expanded from about 200 in 1870 to nearly 31,000 by 1905, yielding up to 18 million tons of coke annually to meet demands for pig iron and steel.[50][51][52] Parallel to coking, destructive distillation of coal produced coal gas (primarily hydrogen, methane, and carbon monoxide) through pyrolysis at 1100–1300°C, initially as a coking byproduct but evolving into a standalone process for urban illumination and heating. By the early 19th century, this supported widespread street lighting in industrial cities, with one ton of coal yielding approximately 400 m³ of gas alongside coal tar and ammonia liquor. Coal tar, the condensed liquid fraction, served as a feedstock for emerging chemical industries, yielding phenols, naphthalene, and pitch for dyes, explosives, and preservatives.[53][54][55] Wood pyrolysis persisted for charcoal production, particularly in U.S. iron smelting until the 1830s, when a typical 1000-ton annual pig iron furnace required about 180,000 bushels of charcoal, sourced from 150 acres of woodland via low-yield pit or kiln carbonization at around 300°C. Late-19th-century brick beehive kilns improved efficiency, processing 50–90 cords per batch and peaking at over 550,000 tons nationwide by 1909, with byproducts like acetic acid (up to 50 gallons per cord) and methanol extracted for solvents and fuels. However, forest depletion and coke's cost advantages prompted a shift, reducing charcoal's metallurgical role by the early 20th century.[56][57][58]Mid-20th Century Advancements

In the mid-20th century, pyrolysis advanced significantly through the commercialization of steam cracking processes in the petrochemical industry, enabling efficient production of ethylene and other light olefins from hydrocarbon feedstocks such as ethane, propane, and naphtha. The first commercial steam cracking plants began operating in the early 1940s, marking a shift from earlier thermal cracking methods by incorporating steam dilution to suppress coke formation and enhance selectivity toward desired alkenes.[59] This innovation supported the post-World War II expansion of synthetic materials, with ethylene output scaling rapidly to meet demands for plastics and chemicals.[60] Pyrolysis furnace designs during this period typically featured horizontal radiant tubes, where feed mixtures were heated to temperatures around 800–900°C under short residence times exceeding 0.5 seconds to achieve thermal decomposition without oxygen.[61] These configurations improved heat transfer and process control compared to pre-war setups, though they were limited by coking tendencies that required frequent decoking cycles. Alloy advancements in tube materials, such as high-chromium steels, enhanced resistance to carburization and thermal fatigue, allowing for higher throughput and reliability in continuous operations.[62] While traditional pyrolysis applications like coke oven operations persisted for metallurgical uses, the petrochemical focus drove innovations in process integration, including better separation of pyrolysis gases into monomer streams via compression, cooling, and distillation. By the 1950s, these developments had established steam pyrolysis as the dominant method for olefin production, with global capacity growing from modest wartime levels to over 1 million tons of ethylene annually by 1960, underpinning the modern chemical industry's growth.[63] Concurrently, exploratory efforts in waste pyrolysis, such as for rubber tires, emerged but remained limited to pilot scales amid the dominance of petroleum-derived feedstocks.[64]Late 20th and 21st Century Developments