Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

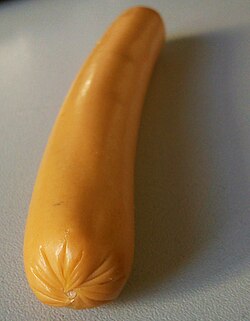

Sausage

View on Wikipedia

A sausage is a type of meat product usually made from ground meat—often pork, beef, or poultry—along with salt, spices and other flavourings. Other ingredients, such as grains or breadcrumbs, may be included as fillers or extenders.

When used as an uncountable noun, the word sausage can refer to the loose sausage meat, which can be used loose, formed into patties, or stuffed into a casing. When referred to as "a sausage", the product is usually cylindrical and enclosed in a casing.

Typically, a sausage is formed in a casing traditionally made from intestine, but sometimes from synthetic materials. Sausages that are sold raw are cooked in many ways, including pan-frying, broiling and barbecuing. Some sausages are cooked during processing, and the casing may then be removed.

Sausage making is a traditional food preservation technique. Sausages may be preserved by curing, drying (often in association with fermentation or culturing, which can contribute to preservation), smoking, or freezing. Some cured or smoked sausages can be stored without refrigeration. Most fresh sausages must be refrigerated or frozen until they are cooked.

Sausages are made in a wide range of national and regional varieties, which differ by the types of meats that are used, the flavouring or spicing ingredients (e.g., garlic, peppers, wine, etc.), and the manner of preparation. In the 21st century, vegetarian and vegan varieties of sausage in which plant-based ingredients are used instead of meat have become much more widely available and consumed.

Etymology

[edit]The word sausage was first used in English in the mid-15th century, spelled sawsyge. This word came from Old North French saussiche (Modern French saucisse). The French word came from Vulgar Latin salsica ("sausage"), from salsicus ("seasoned with salt").[1]

History

[edit]

Sausage making is a natural outcome of efficient butchery. Traditionally, sausage makers salted various tissues and organs such as scraps, organ meats, blood, and fat to help preserve them. They then stuffed them into tubular casings made from the cleaned intestines of the animal, producing the characteristic cylindrical shape.

An Akkadian cuneiform tablet records a dish of intestine casings filled with some sort of forcemeat.[2]

The Greek poet Homer mentioned a kind of blood sausage in the Odyssey, Epicharmus wrote a comedy titled The Sausage, and Aristophanes' play The Knights is about a sausage vendor who is elected leader. Evidence suggests that sausages were already popular both among the ancient Greeks and Romans and most likely with the various tribes occupying the larger part of Europe.[3]

The most famous sausage in ancient Italy was from Lucania (modern Basilicata) and was called lucanica, a name which lives on in a variety of modern sausages in the Mediterranean.[4] During the reign of the Roman emperor Nero, sausages were associated with the Lupercalia festival.[5] Early in the 10th century during the Byzantine Empire, Leo VI the Wise outlawed the production of blood sausages following cases of food poisoning.[5]

A Chinese type of sausage has been described, lap cheong (simplified Chinese: 腊肠; traditional Chinese: 臘腸; pinyin: làcháng) from the Northern and Southern dynasties (420–589).[6] The modern type of lap cheong has a comparatively long shelf life,[7] mainly because of a high content of lactobacilli—so high that it is considered sour by many.[who?][citation needed]

Casings

[edit]

Traditionally, sausage casings were made of the cleaned intestines,[8] or stomachs in the case of haggis and other traditional puddings. Today, natural casings are often replaced by collagen, cellulose, or even plastic casings, especially in the case of industrially manufactured sausages. However, in some parts of the southern United States, companies like Snowden's, Monroe Sausage, Conecuh Sausage, and Kelly Foods still use natural casings, primarily from hog or sheep intestines.[9]

Ingredients

[edit]

A sausage consists of meat cut into pieces or ground, mixed with other ingredients, and filled into a casing. Ingredients may include a cheap starch filler such as breadcrumbs or grains, seasoning and flavourings such as spices, and sometimes others such as apple and leek.[10] The meat may come from various animals, most commonly pork, beef, veal, or poultry. The lean meat-to-fat ratio depends upon the style and producer. The meat content as labelled may exceed 100%, which happens when the weight of meat exceeds the total weight of the sausage after it has been made, sometimes including a drying process which reduces water content.

In some jurisdictions foods described as sausages must meet regulations governing their content. For example, in the United States, the Department of Agriculture specifies that the fat content of different defined types of sausage may not exceed 30%, 35% or 50% by weight; some sausages may contain binders or extenders.[11][12]

Many traditional styles of sausage from Asia and mainland Europe use no bread-based filler and include only meat (lean meat and fat) and flavorings.[13] In the United Kingdom and other countries with English cuisine traditions, many sausages contain a significant proportion of bread and starch-based fillers, which may comprise 30% of ingredients. The filler in many sausages helps them to keep their shape as they are cooked. During cooking, the filler expands, absorbing moisture and fat as the meat contracts.[14]

When the food processing industry produces sausages for a low price point, almost any part of the animal can end up in sausages, varying from cheap, fatty specimens stuffed with meat blasted off the carcasses (mechanically recovered meat, MRM) and rusk. On the other hand, the finest quality contain only choice cuts of meat and seasoning.[10] In Britain, "meat" declared on labels could in the past include fat, connective tissue, and MRM. These ingredients may still be used but must be labelled as such, and up to 10% water may be included without being labelled.[14]

Nutrition and health effects

[edit]Meat sausages are a source of protein. Most sausages have been cured, smoked, or fermented, which makes them forms of processed meat. According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), processed meat causes cancer, particularly colorectal cancer.[15] Strong evidence also links processed meat with higher risks of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.[16] The World Cancer Research Fund recommends minimizing consumption of processed meats.[17]

National varieties

[edit]

Many nations and regions have their own characteristic sausages, using meats and other ingredients native to the region and employed in traditional dishes.

Asia

[edit]Brunei

[edit]Belutak is the traditional Bruneian beef sausage.[18] It is made with minced beef and tallow, marinated with garlic, salt, chillies and spices, and stuffed into cow's or buffalo's small intestines.[18][19] It is then fermented through dehydration.[18] Belutak is a common side dish alongside ambuyat.[19]

China

[edit]

A European-style smoked savory hóng cháng (simplified Chinese: 红肠; traditional Chinese: 紅腸 red sausage) is produced in Harbin, China's northernmost major city.[20] It is similar to Lithuanian and Polish sausages including kiełbasa and podhalańska and tends to have a more European flavour than other Chinese sausages. This kind of sausage was first produced in a Russian-capitalized factory named Churin sausage factory in 1909. Harbin-style sausage has become popular in China, especially in northern regions.[20]

Lap cheong (simplified Chinese: 腊肠; traditional Chinese: 臘腸; pinyin: làcháng; Jyutping: laap6 coeng4; Cantonese Yale: laahp chéung; also lap chong, lap chung, lop chong) are dried pork sausages that look and feel like pepperoni but are much sweeter. In southwestern China, sausages are flavored with salt, red pepper and wild pepper. People often cure sausages by smoking and air drying.[citation needed]

Taiwan

[edit]Small sausage in large sausage, a segment of Taiwanese pork sausage is wrapped in a sticky rice sausage to make this delicacy, usually served chargrilled.

Laos

[edit]

There are several Lao sausage types, but the most popular are sai ua and sai gork that have a unique taste and are different from most sausages found internationally. Sai oua is an ancient Lao word that literally combines sai (intestine) with ua (stuffed). It originated from Luang Prabang, an ancient royal capital of the former Lan Xang kingdom (1353–1707) located in Northern Laos.[21] Sai ua moo (Lao sausage made with pork meat) was listed among a collection of hand-written recipes from Phia Sing (1898–1967), the king's personal chef and master of ceremonies.[22] Both sai ua and sai gork are some of the most popular traditional Lao dishes enjoyed by Lao people not only in Laos[23] but also in countries where Lao people have migrated to.[24]

Philippines

[edit]

In the Philippines, sausages are generally called longaniza (Filipino: longganisa) in the northern regions and chorizo (Visayan: choriso, tsoriso or soriso) in the southern regions. They are usually fresh or smoked sausages, distinguished primarily by either being sweet (jamonado or hamonado) or garlicky (de recado or derecado). There are numerous kinds of sausages in the Philippines, usually unique to a specific region like Vigan longganisa, Alaminos longganisa, and Chorizo de Cebu. The most widely known sausages in Philippine cuisine is the Pampanga longganisa. Bulk sausage versions are also known in Philippine English as "skinless sausages". There are also a few dry sausages like Chorizo de Bilbao and Chorizo de Macao. Most Filipino sausages are made from pork, but they can also be made from chicken, beef, or even tuna.[25]

Thailand

[edit]

There are many varieties of sausages known to Thai cuisine, some of which are specialities of a specific region of Thailand. From northern Thailand comes sai ua, a grilled minced pork sausage flavored with curry paste and fresh herbs.[26] Another grilled sausage is called sai krok Isan, a fermented sausage with a distinctive slightly sour taste from northeastern Thailand (the region also known as Isan).[27]

Vietnam

[edit]

Europe

[edit]Britain and Ireland

[edit]

In the UK and Ireland, sausages are a very popular and common feature of the national diet and popular culture. British sausages[28] and Irish sausages are normally made from raw (i.e., uncooked, uncured, unsmoked) pork, beef, venison or other meats mixed with a variety of herbs and spices and cereals, many recipes of which are traditionally associated with particular regions (for example Cumberland sausages and Lincolnshire sausage). They normally contain a certain amount of rusk or bread-rusk, and are traditionally cooked by frying, grilling or baking. They are most typically 10–15 cm (3.9–5.9 in) long, the filling compressed by twisting the casing into concatenated "links" into the sausage skin, traditionally made from the prepared intestine of the slaughtered animal; most commonly a pig.

Due to their habit of often exploding due to shrinkage of the tight skin during cooking, they are often referred to as bangers, particularly when served with the most common accompaniment of mashed potatoes to form a bi-national dish known as bangers and mash.[29][30]

Pigs in blankets is a dish consisting of small sausages (usually chipolatas) wrapped in bacon.[31][32][33] They are a popular and traditional accompaniment to roast turkey in a Christmas dinner and are served as a side dish.[34][32][35]

In Dublin, sausages are often served in a stew called coddle where they are boiled without first being browned.[36]

There are various laws concerning the meat content of sausages in the UK. The minimum meat content to be labelled pork sausages is 42% (32% for other types of meat sausages). These may contain MRM which was previously included in meat content, but under later EU law cannot be so described.[37][38]

Scotland

[edit]A popular breakfast food is the square sausage, also known as a Lorne sausage. This is normally eaten as part of a full Scottish breakfast or on a Scottish morning roll. The sausage is produced in a rectangular block and individual portions are sliced off. It is seasoned mainly with pepper. It is rarely seen outside Scotland.[39]

Poland

[edit]

Polish sausages, kiełbasa, come in a wide range of styles such as swojska, krajańska, szynkowa (a ham sausage), biała, śląska, krakowska, podhalańska, kishka and others. Sausages in Poland are generally made of pork, rarely beef. Sausages with low meat content and additions like soy protein, potato flour or water binding additions are regarded as of low quality. Because of climate conditions, sausages were traditionally preserved by smoking, rather than drying, like in Mediterranean countries.

Since the 14th century, Poland excelled in the production of sausages, thanks in part to the royal hunting excursions across virgin forests with game delivered as gifts to friendly noble families and religious hierarchy across the country. The extended list of beneficiaries of such diplomatic generosity included city magistrates, academy professors, voivodes, szlachta. Usually the raw meat was delivered in winter and the processed meat throughout the rest of the year. With regard to varieties, early Italian, French and German influences played a role. Meat commonly preserved in fat and by smoking was mentioned by historian Jan Długosz in his annals:Annales seu cronici incliti regni Poloniae The Annales covered events from 965 to 1480, with mention of the hunting castle in Niepołomice along with King Władysław sending game to Queen Zofia from Niepołomice Forest, the most popular hunting ground for the Polish royalty beginning in the 13th century.[3]

Italy

[edit]

Sausages in Italian cuisine (Italian: salsiccia, Italian: [salˈsittʃa], pl. salsicce) are often made of pure pork. Sometimes they may contain beef. Fennel seeds and chilli are generally used as the primary spices in the South of Italy, while in the center and North of the country black pepper and garlic are more often used.

An early example of Italian sausage is lucanica, discovered by Romans after the conquest of Lucania. Lucanica's recipe changed over the centuries and spread throughout Italy and the world with slightly different names.[40] Today, lucanica sausage is identified as Lucanica di Picerno, produced in Basilicata (whose territory was part of the ancient Lucania).[41]

Mazzafegato sausage ('liver mash', or 'liver sausage') is a sausage typically from Abruzzo, Lazio, Marche, Umbria, and Tuscany regions that includes mashed liver. The style from Abruzzo includes pork liver, heart, lungs, and pork cheek, and is seasoned with garlic, orange peel, salt, pepper, and bay leaves.[42] Salsiccia al finocchio ('fennel sausage') is a sausage popularised in the Sicily region.[43][44] These sausages differ from the Tuscan style sausage due the addition of crumbed, dried fennel seeds to the other spices used.[45]

Salsiccia fresca ('fresh sausage') is a type of sausage that is usually made somewhat spicy. It is made from fresh meat (often pork) and fat, and is flavoured with spices, salt, and pepper, and traditionally stuffed into natural gut casings.[45][46] Salsiccia fresca al peperoncino ('fresh chilli sausage') is a spicy sausage flavoured with chopped garlic, salt, and chilli pepper (which gives the sausage a redder colour).[45] Salsiccia secca ('dried sausage') is an air dried sausages typically made from either the meat of domestic pigs or from the meat from wild boars.[45] Salsiccia toscana ('Tuscan sausage'), also known as sarciccia, is made from various cuts of pork, including the shoulder and ham, which is chopped and mixed with herbs such as sage and rosemary.[46]

Malta

[edit]Maltese sausage (Maltese: Zalzett tal-Malti) is made of pork, sea salt, black peppercorns, coriander seeds and parsley. It is short and thick in shape and can be eaten grilled, fried, stewed, steamed or even raw when freshly made. A barbecue variety is similar to the original but with a thinner skin and less salt.[47][48]

Ukraine

[edit]In Ukrainian sausage is called "kovbasa" (ковбаса). It is a general term and is used to describe a variety of sausages including "domashnia" (homemade kovbasa), "pechinky" (liver kovbasa), "krovianka" (kovbasa filled with blood and buckwheat) and "vudzhena" (smoked kovbasa). The traditional varieties are similar to Polish kielbasa.

It is served in a variety of ways such as fried with onions atop varenyky, sliced on rye bread, eaten with an egg and mustard sauce, or in "Yayechnia z Kovbosoyu i yarnoyu" a dish of fried kovbasa with red capsicum and scrambled eggs. In Ukraine kovbasa may be roasted in an oven on both sides and stored in ceramic pots with lard. The sausage is often made at home; however it has become increasingly brought at markets and even supermarkets. Kovbasa also tends to accompany "pysanka" (dyed and decorated eggs) as well as the eastern Slavic bread, paska in Ukrainian baskets at Easter time and is blessed by the priest with holy water before being consumed.[49]

France and Belgium

[edit]

French distinguishes between saucisson (sec), cured sausage eaten uncooked, and saucisse, fresh sausage that needs cooking. Saucisson is almost always made of pork cured with salt, spices, and occasionally wine or spirits, but it has many variants which may be based on other meats and include nuts, alcohol, and other ingredients. It also differentiates between saucisson and boudin ("pudding") which are similar to the British Black, White and Red puddings.

Specific kinds of French sausage include:

- Fresh sausages, mostly grilled, sometimes stewed

- Boudin blanc, a soft, light-colored sausage made of chicken, pork, or veal, or a mixture, and usually also containing eggs and milk;

- Boudin noir, a blood sausage;

- Andouillette, made of pork intestines;

- Cervelas de Lyon, with pistachios or truffles;

- Chipolata, thin and long;

- Crépinette, a small, flattened sausage wrapped in caul fat rather than a casing;

- Merguez, a spicy mutton- or beef-based sausage;

- Saucisse de Toulouse, often used in cassoulet

- Cured or smoked sausages, saucisson, served thinly sliced

- Andouille, usually smoked, made primarily of pork intestines

- Rosette de Lyon

- Saucisse de Morteau, smoked

- Saucisson de Lyon

Other French sausages include the diot.

Germany

[edit]

There is an enormous variety of German sausages. Some examples of German sausages include Frankfurters/Wieners, Bratwürste, Rindswürste, Knackwürste, and Bockwürste. Currywurst, a dish of sausages with curry sauce, is a popular fast food in Germany.

Greece

[edit]

Loukániko (Greek: λουκάνικο) is the common Greek word for pork sausage.

The name 'loukaniko' is derived from ancient Roman cuisine.

Nordic countries

[edit]

Nordic sausages (Danish: pølse, Norwegian: pølsa/pølse/pylsa/korv/kurv, Icelandic: bjúga/pylsa/grjúpán/sperðill, Swedish: korv, Finnish: makkara) are usually made of 60–80% very finely ground pork, very sparsely spiced with pepper, nutmeg, allspice or similar sweet spices (ground mustard seed, onion and sugar may also be added). Water, lard, rind, potato starch flour and soy or milk protein are often added for binding and filling. In southern Norway, grilled and wiener sausages are often wrapped in a lompe, a potato flatbread somewhat similar to a lefse.

Virtually all sausages will be industrially precooked and either fried or warmed in hot water by the consumer or at the hot dog stand. Since hot dog stands are ubiquitous in Denmark (known as Pølsevogn) some people regard pølser as one of the national dishes, perhaps along with medisterpølse, a fried, finely ground pork and bacon sausage. The most noticeable aspect of Danish boiled sausages (never the fried ones) is that the casing often contains a traditional bright-red dye. They are also called wienerpølser and legend has it they originate from Vienna where it was once ordered that day-old sausages be dyed as a means of warning.

The traditional Swedish falukorv is a sausage made of a grated mixture of pork and beef or veal with potato flour and mild spices, similarly red-dyed sausage, but about 5 cm thick, usually baked in the oven coated in mustard or cut in slices and fried. The sausage got its name from Falun, the city from where it originates, after being introduced by German immigrants who came to work in the region's mines. Unlike most other ordinary sausages it is a typical home dish, not sold at hot dog stands. Other Swedish sausages include prinskorv, fläskkorv, köttkorv and isterband; all of these, in addition to falukorv, are often accompanied by potato mash or rotmos (a root vegetable mash) rather than bread. Isterband is made of pork, barley groats and potato and is lightly smoked.

In Iceland, lamb may be added to sausages, giving them a distinct taste. Horse sausage and mutton sausage are also traditional foods in Iceland, although their popularity is waning. Liver sausage, which has been compared to haggis, and blood sausage are also a common foodstuff in Iceland.

In Finland, there are a few traditional types of sausages that have become a part of Finnish cuisine, such as ryynimakkara (groat sausage).[50] There's also a blood sausage called mustamakkara (black sausage), which has become a traditional dish in the Tampere region.[51] Usually grilled sausages are very popular in Finland during the summer, especially in juhannus.[52]

Portugal and Brazil

[edit]

Embutidos (or enchidos) such as chouriço, linguiça, or alheira generally contain hashed meat, most commonly pork, seasoned with aromatic herbs or spices (pepper, red pepper, paprika, garlic, rosemary, thyme, cloves, ginger, nutmeg, etc.).

Russia

[edit]

Traditional Russian cuisine eschews the fine cutting or grounding of meat. Thus sausagemaking, though generally known in Russia since at least 12th century, was not popular and largely started in earnest with the Petrine reforms, when a lot of Western products and practices were introduced. Traditional sausages were based on mixing meat with cereals, much like modern kishka and Polish kaszanka, while the newer purely meat varieties were made in German and Polish styles, often highly spiced and loaded with preservatives for non-refrigerated storage. One of the pre-revolutionary recipes specified as much as half pound of saltpetre per a pood of meat.[53]

After the Revolution, the sausage-making was largely concentrated in large, governmentally controlled meat processing plants, often built from the American examples, which introduced new, medically controlled and industrially made styles such as omnipresent Soviet bolognas — Doktorskaya sausage and its fatter Lyubitelskaya variant, as well as generic wieners and very status-loaded and scarce smoked sausages and salamis. Traditional sausages continued to be made for local consumption by the farmers and such, often sold on Kolkhoz markets, like the home-style sausage, made from roughly minced pork and its fat, spiced with garlic and black pepper — this was a raw sausage, intended for roasting or grilling, but sometimes cooked by hot smoking for preservation and flavour (this variant is often called Ukrainian).

Since the return of capitalism, all imaginable types of sausage are produced and imported in Russia, but the traditional styles, be it a factory made Doctor's bologna, artisanal links of delicately smoked Ukrainian or boldly red Krakow, or buckwheat-stuffed blood sausage, still endure.

Serbia

[edit]Types of sausages in Serbia include Sremska, Požarevačka, and Sudžuk.

Spain

[edit]

In Spain, fresh sausages, salchichas, which are eaten cooked, and cured sausages, embutidos, which are eaten uncooked, are two distinct categories. Among the cured sausages are found products like chorizo, salchichón, and sobrasada. Blood sausage, morcilla, is found in both cured and fresh varieties. They are made with pork meat and blood, usually adding rice, garlic, paprika and other spices. There are many regional variations, and in general they are either fried or cooked in cocidos.

Fresh sausage may be red or white. Red sausages contain paprika (pimentón in Spanish) and are usually fried; they can also contain other spices such as garlic, pepper or thyme. The most popular type of red sausage is perhaps txistorra, a thin and long paprika sausage originating in Navarre. White sausages do not contain paprika and can be fried, boiled in wine, or, more rarely, in water.

Sweden

[edit]See the section Nordic countries above

Switzerland

[edit]

The cervelat, a cooked sausage, is often referred to as Switzerland's national sausage. A great number of regional sausage specialties exist as well, including air-dried such as salami.

Latin America

[edit]In most of Latin America, a few basic types of sausages are consumed, with slight regional variations on each recipe. These are chorizo (raw, rather than cured and dried like its Spanish namesake), longaniza (usually very similar to chorizo but longer and thinner), morcilla or relleno (blood sausage), and salchichas (often similar to hot dogs or Vienna sausages). Beef tends to be more predominant than in the pork-heavy Spanish equivalents.

Argentina and Uruguay

[edit]In Argentina and Uruguay, many sausages are consumed. Eaten as part of the traditional asado, chorizo (beef or pork, flavored with spices) and morcilla (blood sausage or black pudding) are the most popular. Both share a Spanish origin. One local variety is the salchicha argentina (Argentine sausage), criolla or parrillera (literally, barbecue-style), made of the same ingredients as the chorizo but thinner.[54] There are hundreds of salami-style sausages. Very popular is the salame tandilero, from the city of Tandil. Other types include longaniza, cantimpalo and soppressata.[55]

Vienna sausages are eaten as an appetizer or in hot dogs (called panchos), which are usually served with different sauces and salads. Leberwurst is usually found in every market. Weißwurst is also a common dish in some regions, eaten usually with mashed potatoes or chucrut (sauerkraut).[56][57]

Chile

[edit]Longaniza is the most common type of sausage, or at least the most common name in Chile for sausages that also could be classified as chorizo. The Chilean variety is made of four parts pork to one part bacon (or less) and seasoned with finely ground garlic, salt, pepper, cumin, oregano, paprika and chilli sauce. The cities of Chillán and San Carlos are known among Chileans for having the best longanizas.[58][59]

Another traditional sausage is the prieta, the Chilean version of blood sausage, generally known elsewhere in Latin America as morcilla. In Chile, it contains onions, spices and sometimes walnut or rice and is usually eaten at asados or accompanied by simple boiled potatoes. It sometimes has a very thick skin so is cut open lengthwise before eating. "Vienesa"s or Vienna sausages are also very common and are mainly used in the completo, the Chilean version of the hot dog.

Colombia

[edit]

A grilled chorizo served with a buttered arepa is one of the most common street foods in Colombia. Butifarras Soledeñas are sausages from Soledad, Atlántico, Colombia. In addition to the standard Latin American sausages, dried pork sausages are served cold as a snack, often to accompany beer drinking. These include cábanos (salty, short, thin, and served individually), butifarras (of Catalan origin; spicier, shorter, fatter and moister than cábanos, often eaten raw, sliced and sprinkled with lemon juice) and salchichón (a long, thin and heavily processed sausage served in slices).

Mexico

[edit]

The most common Mexican sausage by far is chorizo. It is fresh and usually deep red in color (in most of the rest of Latin America, chorizo is uncolored and coarsely chopped). Some chorizo is so loose that it spills out of its casing as soon as it is cut; this crumbled chorizo is a popular filling for torta sandwiches, eggs, breakfast burritos and tacos. Salchichas, longaniza (a long, thin, lightly spiced, coarse chopped pork sausage), moronga (a type of blood pudding) and head cheese are also widely consumed.

El Salvador

[edit]

In El Salvador, chorizos are quite common, and the ones from the city of Cojutepeque are particularly well known there. The links, especially of those from Cojutepeque, are separated with corn husks tied in knots (see photo). Like most chorizos in Latin America, they are sold raw and must be cooked.

North America

[edit]

North American breakfast or country sausage is made from uncooked ground pork, breadcrumbs and salt mixed with pepper, sage, and other spices. It is widely sold in grocery stores in a large synthetic plastic casing, or in links which may have a protein casing. It is also available sold by the pound without a casing. It can often be found on a smaller scale in rural regions, especially in southern states, where it is either in fresh patties or in links with either natural or synthetic casings as well as smoked. This sausage is most similar to English-style sausages and has been made in the United States since colonial days. It is commonly sliced into small patties and pan-fried, or cooked and crumbled into scrambled eggs or gravy. Other uncooked sausages are available in certain regions in link form, including Italian, bratwurst, chorizo, and linguica.

Several varieties of meat-and-grain sausages developed in the US. Scrapple is a pork-and-cornmeal sausage that originated in the Mid-Atlantic States. Goetta is a pork-and-oats sausage that originated in Cincinnati.[60] Livermush, originating in North Carolina, is made with pork, liver, and cornmeal or rice.[60]: 42 All were developed by German immigrants.[60]

In Louisiana, there is a variety of sausage that is unique to its heritage, a variant of andouille. Unlike the original variety native to Northern France, Louisiana andouille has evolved to be made mainly of pork butt, not tripe, and tends to be spicy with a flavor far too strong for the mustard sauce that traditionally accompanies French andouille: prior to casing, the meat is heavily spiced with cayenne and black pepper. The variety from Louisiana is known as Tasso ham and is often a staple in Cajun and Creole cooking. Traditionally it is smoked over pecan wood or sugar cane as a final step before being ready to eat. In Cajun cuisine, boudin is also popular. Sausages made in the French tradition are popular in Québec, Ontario, and parts of the Prairies, where butchers offer their own variations on the classics. Locals of Flin Flon are especially fond of the Saucisse de Toulouse, which is often served with poutine.

Hot dogs, also known as frankfurters or wieners, are the most common pre-cooked sausage in the United States and Canada. Another popular variation is the corn dog, which is a hot dog that is deep fried in cornmeal batter and served on a stick. A common and popular regional sausage in New Jersey and surrounding areas is pork roll, usually thinly sliced and grilled as a breakfast meat.

Other popular ready-to-eat sausages, often eaten in sandwiches, include salami, American-style bologna, Lebanon bologna, prasky, liverwurst, and head cheese. Pepperoni and Italian sausage are popular pizza toppings.

Oceania

[edit]Australia

[edit]

Australian sausages have traditionally been made with beef, pork and chicken, while recently game meats such as kangaroo have been used that typically have much less fat. English style sausages, known colloquially as "snags", come in two varieties: thin, that resemble an English 'breakfast' sausage, and thick, known as 'Merryland' in South Australia. These types of sausage are popular at barbecues and can be purchased from any butcher or supermarket. Devon is a spiced pork sausage similar to Bologna sausage and Gelbwurst. It is usually made in a large diameter, and it is often thinly sliced and eaten cold in sandwiches.

Mettwurst and other German-style sausages are highly popular in South Australia, often made in towns like Hahndorf and Tanunda, due to the large German immigration to the state during early settlement. Mettwurst is usually sliced and eaten cold on sandwiches or alone as a snack. A local variation on cabanossi, developed by Italian migrants after World War II using local cuts of meat, is a popular snack at parties. The Don small goods company developed a spiced snack-style sausage based on the cabanossi in 1991 called Twiggy Sticks.

In Australia it is common to eat a sausage on a single slice of bread topped with onions and either tomato or barbeque sauce. This food item is known as a sausage sizzle.[61]

Vegetarian versions

[edit]

Vegetarian and vegan sausages are also available in some countries, or can be made from scratch at home.[62] These may be made from tofu, seitan, nuts, pulses, mycoprotein, soya protein, vegetables or any combination of similar ingredients that will hold together during cooking.[63] These sausages, like most meat-replacement products, generally fall into two categories: some are shaped, colored, flavored, and spiced to replicate the taste and texture of meat as accurately as possible; others such as the Glamorgan sausage rely on spices and vegetables to lend their natural flavor to the product and no attempt is made to imitate meat.[64] While not vegetarian, the soya sausage was invented 1916 in Germany. First known as Kölner Wurst ("Cologne Sausage") by later German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer (1876–1967).[65]

Gallery

[edit]-

Salami, a cured sausage

-

Vegetarian sausages with baked beans on toast

-

Italian salsicce pizza

-

A sliced chorizo sausage

-

Two sausage rolls on a plate

-

Italian salsicce with tomato sauce

-

Sausages after roasting

-

A sausage sandwich with egg and ketchup

-

Raw sausages

-

Some sausages grilling

-

Yam mu yo, a Thai sausage salad

-

A salmon sausage

See also

[edit]Similar food

- Kofte – Middle Eastern and South Asian meatballs

- Seekh kebab – Type of skewered kebab

- Shish kofta – Turkish dish of mincemeat kofta grilled on skewers

- Kabab koobideh – Iranian grilled minced meat dish

- Mititei – Romanian meat roll

- Ćevapi – Dish from Southeast Europe

- Kuru köfte – Turkish breaded meatball

- Kebapcheta – Dish of grilled minced meat with spices

References

[edit]- ^ "sausage – Origin and history of sausage by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 1 January 2017.

- ^ Jean Bottéro, "The Cuisine of Ancient Mesopotamia", The Biblical Archaeologist 48:1:36-47 (March 1985) JSTOR 3209946

- ^ a b (in Polish) Eleonora Trojan, Julian Piotrowski, Tradycyjne wędzenie Archived 29 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine AA Publishing. 96 pages. ISBN 978-83-61060-30-7

- ^ Riley, Gillian (2007). The Oxford companion to Italian food. Oxford: OUP. pp. 301–302. ISBN 978-0-19-860617-8. OCLC 602719737. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ a b "All About Sausages". www.victoriahansenfood.com. 24 August 2014. Archived from the original on 11 December 2018. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ^ Felicia Lee, Food Republic, Feb. 23, 2024, "What Is Lap Cheong And How Do You Cook With It?" "The first written record in Chinese of sausage production as we know it –- that is, meat stuffed into casings –- dates to 455 AD. The description appeared in a guide titled "Essential Techniques for the Welfare of the People""

- ^ Zeuthen, Peter (2007). "1. A Historical Perspective of Meat Fermentation. Early Records Of Fermented Meat Products. Raw Cured Ham". In Toldrá, Fidel (ed.). Handbook of fermented meat and poultry. John Wiley & Sons. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-470-37643-0. OCLC 1039150137. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ Oster, Kenneth V. (2011). The Complete Guide to Preserving Meat, Fish, and Game: Step-by-step Instructions to Freezing, Canning, and Smoking. Atlantic Publishing Company. ISBN 9781601383433. Archived from the original on 19 November 2017.

- ^ Velasco, Eric (24 December 2021). "Eat your way along the Lower Alabama Smoked Sausage Trail". Yellowhammer News. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ a b BBC: Pork sausage recipes Archived 26 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine. "The meat may be mixed with breadcrumbs, cereals or other ingredients such as leek or apple."

- ^ "USDA Standards of Identity; see Subparts E, F and G". Archived from the original on 19 December 2007.

- ^ "PART 319—DEFINITIONS AND STANDARDS OF IDENTITY OR COMPOSITION, parts E, F, and G" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 January 2014.

- ^ Joy of Cooking, Rombauer and Becker; The Fine Art of Italian Cooking, Bugialli

- ^ a b "What's in the great British banger?". 27 September 2002. Archived from the original on 27 December 2007 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ "Cancer: Carcinogenicity of the consumption of red meat and processed meat". World Health Organization. 26 October 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2025.

- ^ Libera, Justyna; Iłowiecka, Katarzyna; Stasiak, Dariusz (December 2021). "Consumption of processed red meat and its impact on human health: A review". International Journal of Food Science & Technology. 56 (12): 6115–6123. doi:10.1111/ijfs.15270. ISSN 0950-5423.

- ^ "Limit consumption of red and processed meat: Recommendation evidence". World Cancer Research Fund. Retrieved 24 September 2025.

- ^ a b c Azli Azney (10 May 2021). "On a journey to become Brunei's biggest belutak producer: Nikmat Rose". Biz Brunei. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ a b Lai S. Reyes (10 September 2020). "A taste of satay, ambuyat, trey amok, ayam masak merah, mohinga, larp, hokkien mee, tom yum, goi cuon & adobo". Philstar. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ a b "31 dishes: A guide to China's regional specialties". CNN Travel. Archived from the original on 25 February 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ Massie, Victor-Alphonse (1894). Dictionnaire français-laotien: Mission Pavie, exploration de l' indochine (Latin characters). p. 108.

- ^ "Lao Reci-pes". www.seasite.niu.edu. Archived from the original on 31 May 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ "Laotian food - 15 Famous Dishes You Must Try When Travel in Laos". Laos Travel. 4 November 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ Rao, Tejal (8 March 2022). "Once Obscured in the U.S., Lao Cooks Share and Celebrate Their Cuisine". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ Edgie Polistico (2017). Philippine Food, Cooking, & Dining Dictionary. Anvil Publishing, Incorporated. ISBN 9786214200870.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "::Sai-ua ,Lanna Food,Thai Food,Thai Lanna Food,Food and Cuisine,Northern Thai Food,Herb,Thai Ingredient::". Library.cmu.ac.th. 9 July 2007. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ "Thai Fermented Sausages from the Northeast (Sai Krok Isan ไส้กรอกอีสาน)". SheSimmers. Shesimmers.com. 23 April 2011. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ "The British Sausage". The English Breakfast Society. Archived from the original on 6 January 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ^ Aura Kate Hargreaves. "My Dearest: A War Story, a Love Story, a True Story of WW1 by Those Who Lived It". Property People JV Ltd. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ "banger – Search Results – Sausage Links". www.sausagelinks.co.uk. Archived from the original on 12 January 2014.

- ^ Lee, Jeremy (26 November 2017). "The great Christmas taste test 2017". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- ^ a b "Everything you want to know about pigs in blankets". Erudus. 2 December 2021. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ Thompson, Rachel (24 December 2018). "I ate 100 different 'pigs in blankets' at a sausage party and it was painfully delicious". Mashable. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ Neild, Barry (14 December 2013). "Turkey, pigs in blankets, even sprouts… but no Christmas pudding, thanks". The Observer. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- ^ "Classic pigs in blankets". BBC Good Food. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ Dundon, Kevin (10 November 2020). "Kevin Dundon's Irish Coddle: Today". RTÉ.ie.

- ^ "Health & Legal". sausagelinks.co.uk. Archived from the original on 13 February 2010.

- ^ "The secret life of the sausage: A great British institution". The Independent. London. 30 October 2006. Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ Sorooshian, Roxanne (8 November 2009). "Square-go over status of Lorne sausage". Sunday Herald. Glasgow. p. 2. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ "Forklore: A Very Important Sausage". Los Angeles Times. 22 January 2012. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ "The Lucanica di Picerno, A Historical Sausage". Arte Cibo. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ "From North to South, Italian Sausages Variety". lacucinaitaliana.com. La Cucina Italiana. 24 May 2020. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ Gerard-Sharp, Lisa (2016). Sicily. Apa Publications. p. 128. ISBN 9781780053110.

- ^ Root, Waverley (1903–1992). The food of Italy. New York : Vintage Books. p. 604. ISBN 0679738967.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ a b c d Bardi, Carla (2004). Prosciutto. South San Francisco : Wine Appreciation Guild. p. 44. ISBN 1-891267-54-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ a b Culinaria Italy : pasta, pesto, passion. H.f. Ullman/Tandem Verlag GmbH. 2008. p. 240. ISBN 978-3-8331-1049-8.

- ^ Lawrence, Georgina (30 June 2013). ZALZETT MALTI ~ MALTESE SAUSAGE Archived 13 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Tal-Forn. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ^ Scicluna, Frank L. (January 2014). How to make Maltese sausages Archived 25 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine. ozmalta.com. Consulate of Malta in South Australia Newsletter. p. 14. Retrieved on 12 October 2016.

- ^ S. Yakovenko (2013). C. Etteridge (ed.). Taste of Ukraine. illustrated by T. Koldunenko. Lidcombe, NSW, Australia: Sova Books. ISBN 9780987594310.

- ^ Kuusisalo, Hanna (11 May 2020). "Ryynimakkara on nostalginen makumuisto lapsuudesta". Kotiliesi (in Finnish). Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ Sirén, Anna (4 July 2013). "Verinen perinneherkku pitää pintansa Pirkanmaalla". Yle (in Finnish). Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ Halla-aho, Emma (23 June 2021). "Tirisevä grillimakkara on joka juhannuksen horjumaton suosikki – tänäkin juhannuksena myynti kolminkertaistuu, kertovat lihatalot". Yle (in Finnish). Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ History of sausagemaking in Russia, Kommersant, in Russian.

- ^ "Sausage-Chorizo". Asado Argentina. Archived from the original on 12 February 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ "Argentina – The gastronomy in the World". Argentina.ar. 14 November 2007. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ "La salchicha de viena cumple 200 años". Clarin.com. 27 May 2005. Archived from the original on 12 March 2009. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ "La inmigración: hecho integrador de La Argentina y el surgir de una nueva gastronomía". La Cocina de Pasqualino Marchese (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 21 July 2010.

- ^ Gastronomy, Chile's top traditional foods: a visitor's guide Archived 11 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine 29 July 2009, retrieved 6 August 2013

- ^ Chilean Longanizas, detailed explanation of the traditional method www.atlasvivodechile.com retrieved 11 November 2013

- ^ a b c Woellert, Dann (2019). Cincinnati Goetta: A Delectable History. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781467142083. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- ^ "Cost of living snags the iconic Bunnings sausage sizzle". The West Australian. 12 July 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ Peery, Susan Mahnke; Reavis, Charles G. (2002). "Vegetarian Sausages". Home Sausage Making (3rd ed.). North Adams, Mass.: Storey Books. pp. 201–212. ISBN 978-1-58017-471-8. Archived from the original on 11 May 2016.

- ^ Lapidos, Juliet (8 June 2011). "Vegetarian Sausage: Which imitation pig-scrap-product is best?". Slate. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013.

- ^ Godwin, Nigel (27 February 2009). "St David's Day recipes: Glamorgan sausages". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 24 May 2012.

- ^ "Bibliografische Daten: GB131402 (A) ― 28 August 1919". Espacenet. Archived from the original on 28 February 2016. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

External links

[edit]- The British Sausage by The English Breakfast Society