Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Vagina

View on WikipediaIt has been suggested that this article be split out into a new article titled Human Vagina. (Discuss) (November 2024) |

| Vagina | |

|---|---|

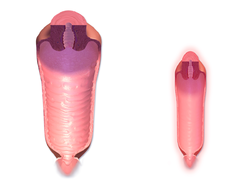

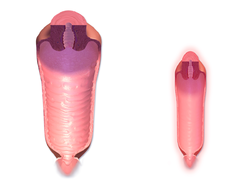

Normal adult human vagina, before (left) and after (right) menopause | |

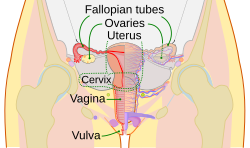

Diagram of the female human reproductive tract and ovaries | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Urogenital sinus and paramesonephric ducts |

| Artery | Superior part to uterine artery, middle and inferior parts to vaginal artery |

| Vein | Uterovaginal venous plexus, vaginal vein |

| Nerve |

|

| Lymph | Upper part to internal iliac lymph nodes, lower part to superficial inguinal lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | vagina |

| MeSH | D014621 |

| TA98 | A09.1.04.001 |

| TA2 | 3523 |

| FMA | 19949 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

In mammals and other animals, the vagina (pl.: vaginas or vaginae)[1] is the elastic, muscular reproductive organ of the female genital tract. In humans, it extends from the vulval vestibule to the cervix (neck of the uterus). The vaginal introitus is normally partly covered by a thin layer of mucosal tissue called the hymen. The vagina allows for copulation and birth. It also channels menstrual flow, which occurs in humans and closely related primates as part of the menstrual cycle.

To accommodate smoother penetration of the vagina during sexual intercourse or other sexual activity, vaginal moisture increases during sexual arousal in human females and other female mammals. This increase in moisture provides vaginal lubrication, which reduces friction. The texture of the vaginal walls creates friction for the penis during sexual intercourse and stimulates it toward ejaculation, enabling fertilization. Along with pleasure and bonding, women's sexual behavior with other people can result in sexually transmitted infections (STIs), the risk of which can be reduced by recommended safe sex practices. Other health issues may also affect the human vagina.

The vagina has evoked strong reactions in societies throughout history, including negative perceptions and language, cultural taboos, and their use as symbols for female sexuality, spirituality, or regeneration of life. In common speech, the word "vagina" is often used incorrectly to refer to the vulva or to the female genitals in general.

Etymology and definition

[edit]The term vagina is from Latin vāgīna, meaning "sheath" or "scabbard".[1] The vagina may also be referred to as the birth canal in the context of pregnancy and childbirth.[2][3] Although by its dictionary and anatomical definitions, the term vagina refers exclusively to the specific internal structure, it is colloquially used to refer to the vulva or to both the vagina and vulva.[4][5]

Using the term vagina to mean "vulva" can pose medical or legal confusion; for example, a person's interpretation of its location might not match another's interpretation of the location.[4][6] Medically, one description of the vagina is that it is the canal between the hymen (or remnants of the hymen) and the cervix, while a legal description is that it begins at the vulva (between the labia).[4] It may be that the incorrect use of the term vagina is due to not as much thought going into the anatomy of the female genitals as has gone into the study of male genitals, and that this has contributed to an absence of correct vocabulary for the external female genitalia among both the general public and health professionals. Because a better understanding of female genitalia can help combat sexual and psychological harm with regard to female development, researchers endorse correct terminology for the vulva.[6][7][8]

Structure

[edit]Gross anatomy

[edit]

The human vagina is an elastic, muscular canal that extends from the vulva to the cervix.[9][10] The opening of the vagina lies in the urogenital triangle. The urogenital triangle is the front triangle of the perineum and also consists of the urethral opening and associated parts of the external genitalia.[11] The vaginal canal travels upwards and backwards, between the urethra at the front, and the rectum at the back. Near the upper vagina, the cervix protrudes into the vagina on its front surface at approximately a 90 degree angle.[12] The vaginal and urethral openings are protected by the labia.[13]

When not sexually aroused, the vagina is a collapsed tube, with the front and back walls placed together. The lateral walls, especially their middle area, are relatively more rigid. Because of this, the collapsed vagina has an H-shaped cross section.[10][14] Behind, the upper vagina is separated from the rectum by the recto-uterine pouch, the middle vagina by loose connective tissue, and the lower vagina by the perineal body.[15] Where the vaginal lumen surrounds the cervix of the uterus, it is divided into four continuous regions (vaginal fornices); these are the anterior, posterior, right lateral, and left lateral fornices.[9][10] The posterior fornix is deeper than the anterior fornix.[10]

Supporting the vagina are its upper, middle, and lower third muscles and ligaments. The upper third are the levator ani muscles, and the transcervical, pubocervical, and sacrocervical ligaments.[9][16] It is supported by the upper portions of the cardinal ligaments and the parametrium.[17] The middle third of the vagina involves the urogenital diaphragm.[9] It is supported by the levator ani muscles and the lower portion of the cardinal ligaments.[17] The lower third is supported by the perineal body,[9][18] or the urogenital and pelvic diaphragms.[19] The lower third may also be described as being supported by the perineal body and the pubovaginal part of the levator ani muscle.[16]

Vaginal opening and hymen

[edit]

The vaginal opening (also known as the vaginal introitus and the Latin ostium vaginae)[20][21] is at the posterior end of the vulval vestibule, behind the urethral opening. The term introitus is more technically correct than "opening", since the vagina is usually collapsed, with the opening closed. The opening to the vagina is normally obscured by the labia minora (inner lips), but may be exposed after vaginal delivery.[10]

The hymen is a thin layer of mucosal tissue that surrounds or partially covers the vaginal opening.[10] The effects of intercourse and childbirth on the hymen vary. Where it is broken, it may completely disappear or remnants known as carunculae myrtiformes may persist. Otherwise, being very elastic, it may return to its normal position.[22] Additionally, the hymen may be lacerated by disease, injury, medical examination, masturbation or physical exercise. For these reasons, virginity cannot be definitively determined by examining the hymen.[22][23]

Variations and size

[edit]The length of the vagina varies among women of child-bearing age. Because of the presence of the cervix in the front wall of the vagina, there is a difference in length between the front wall, approximately 7.5 cm (2.5 to 3 in) long, and the back wall, approximately 9 cm (3.5 in) long.[10][24] During sexual arousal, the vagina expands both in length and width. If a woman stands upright, the vaginal canal points in an upward-backward direction and forms an angle of approximately 45 degrees with the uterus.[10][18] The vaginal opening and hymen also vary in size; in children, although the hymen commonly appears crescent-shaped, many shapes are possible.[10][25]

Development

[edit]

The vaginal plate is the precursor to the vagina.[26] During development, the vaginal plate begins to grow where the fused ends of the paramesonephric ducts (Müllerian ducts) enter the back wall of the urogenital sinus as the sinus tubercle. As the plate grows, it significantly separates the cervix and the urogenital sinus; eventually, the central cells of the plate break down to form the vaginal lumen.[26] This usually occurs by the twenty to twenty-fourth week of development. If the lumen does not form, or is incomplete, membranes known as vaginal septa can form across or around the tract, causing obstruction of the outflow tract later in life.[26]

There are conflicting views on the embryologic origin of the vagina. The majority view is Koff's 1933 description, which posits that the upper two-thirds of the vagina originate from the caudal part of the Müllerian duct, while the lower part of the vagina develops from the urogenital sinus.[27][28] Other views are Bulmer's 1957 description that the vaginal epithelium derives solely from the urogenital sinus epithelium,[29] and Witschi's 1970 research, which reexamined Koff's description and concluded that the sinovaginal bulbs are the same as the lower portions of the Wolffian ducts.[28][30] Witschi's view is supported by research by Acién et al., Bok and Drews.[28][30] Robboy et al. reviewed Koff and Bulmer's theories, and support Bulmer's description in light of their own research.[29] The debates stem from the complexity of the interrelated tissues and the absence of an animal model that matches human vaginal development.[29][31] Because of this, study of human vaginal development is ongoing and may help resolve the conflicting data.[28]

Microanatomy

[edit]

The vaginal wall from the lumen outwards consists firstly of a mucosa of stratified squamous epithelium that is not keratinized, with a lamina propria (a thin layer of connective tissue) underneath it. Secondly, there is a layer of smooth muscle with bundles of circular fibers internal to longitudinal fibers (those that run lengthwise). Lastly, is an outer layer of connective tissue called the adventitia. Some texts list four layers by counting the two sublayers of the mucosa (epithelium and lamina propria) separately.[32][33]

The smooth muscular layer within the vagina has a weak contractive force that can create some pressure in the lumen of the vagina. Much stronger contractive force, such as during childbirth, comes from muscles in the pelvic floor that are attached to the adventitia around the vagina.[34]

The lamina propria is rich in blood vessels and lymphatic channels. The muscular layer is composed of smooth muscle fibers, with an outer layer of longitudinal muscle, an inner layer of circular muscle, and oblique muscle fibers between. The outer layer, the adventitia, is a thin dense layer of connective tissue and it blends with loose connective tissue containing blood vessels, lymphatic vessels and nerve fibers that are between pelvic organs.[12][33][24] The vaginal mucosa is absent of glands. It forms folds (transverse ridges or rugae), which are more prominent in the outer third of the vagina; their function is to provide the vagina with increased surface area for extension and stretching.[9][10]

The epithelium of the ectocervix (the portion of the uterine cervix extending into the vagina) is an extension of, and shares a border with, the vaginal epithelium.[35] The vaginal epithelium is made up of layers of cells, including the basal cells, the parabasal cells, the superficial squamous flat cells, and the intermediate cells.[36] The basal layer of the epithelium is the most mitotically active and reproduces new cells.[37] The superficial cells shed continuously and basal cells replace them.[10][38][39] Estrogen induces the intermediate and superficial cells to fill with glycogen.[39][40] Cells from the lower basal layer transition from active metabolic activity to death (apoptosis). In these mid-layers of the epithelia, the cells begin to lose their mitochondria and other organelles.[37][41] The cells retain a usually high level of glycogen compared to other epithelial tissue in the body.[37]

Under the influence of maternal estrogen, the vagina of a newborn is lined by thick stratified squamous epithelium (or mucosa) for two to four weeks after birth. Between then to puberty, the epithelium remains thin with only a few layers of cuboidal cells without glycogen.[39][42] The epithelium also has few rugae and is red in color before puberty.[4] When puberty begins, the mucosa thickens and again becomes stratified squamous epithelium with glycogen-containing cells, under the influence of the girl's rising estrogen levels.[39] Finally, the epithelium thins out from menopause onward and eventually ceases to contain glycogen, because of the lack of estrogen.[10][38][43]

Flattened squamous cells are more resistant to both abrasion and infection.[42] The permeability of the epithelium allows for an effective response from the immune system since antibodies and other immune components can easily reach the surface.[44] The vaginal epithelium differs from the similar tissue of the skin. The epidermis of the skin is relatively resistant to water because it contains high levels of lipids. The vaginal epithelium contains lower levels of lipids. This allows the passage of water and water-soluble substances through the tissue.[44]

Keratinization happens when the epithelium is exposed to the dry external atmosphere.[10] In abnormal circumstances, such as in pelvic organ prolapse, the mucosa may be exposed to air, becoming dry and keratinized.[45]

Blood and nerve supply

[edit]Blood is supplied to the vagina mainly via the vaginal artery, which emerges from a branch of the internal iliac artery or the uterine artery.[9][46] The vaginal arteries anastamose (are joined) along the side of the vagina with the cervical branch of the uterine artery; this forms the azygos artery,[46] which lies on the midline of the anterior and posterior vagina.[15] Other arteries which supply the vagina include the middle rectal artery and the internal pudendal artery,[10] all branches of the internal iliac artery.[15] Three groups of lymphatic vessels accompany these arteries; the upper group accompanies the vaginal branches of the uterine artery; a middle group accompanies the vaginal arteries; and the lower group, draining lymph from the area outside the hymen, drain to the inguinal lymph nodes.[15][47] Ninety-five percent of the lymphatic channels of the vagina are within 3 mm of the surface of the vagina.[48]

Two main veins drain blood from the vagina, one on the left and one on the right. These form a network of smaller veins, the vaginal venous plexus, on the sides of the vagina, connecting with similar venous plexuses of the uterus, bladder, and rectum. These ultimately drain into the internal iliac veins.[15]

The nerve supply of the upper vagina is provided by the sympathetic and parasympathetic areas of the pelvic plexus. The lower vagina is supplied by the pudendal nerve.[10][15]

Function

[edit]Secretions

[edit]Vaginal secretions are primarily from the uterus, cervix, and vaginal epithelium in addition to minuscule vaginal lubrication from the Bartholin's glands upon sexual arousal.[10] It takes little vaginal secretion to make the vagina moist; secretions may increase during sexual arousal, the middle of or a little prior to menstruation, or during pregnancy.[10] Menstruation (also known as a "period" or "monthly") is the regular discharge of blood and mucosal tissue (known as menses) from the inner lining of the uterus through the vagina.[49] The vaginal mucous membrane varies in thickness and composition during the menstrual cycle,[50] which is the regular, natural change that occurs in the female reproductive system (specifically the uterus and ovaries) that makes pregnancy possible.[51][52] Different hygiene products such as tampons, menstrual cups, and sanitary napkins are available to absorb or capture menstrual blood.[53]

The Bartholin's glands, located near the vaginal opening, were originally considered the primary source for vaginal lubrication, but further examination showed that they provide only a few drops of mucus.[54] Vaginal lubrication is mostly provided by plasma seepage known as transudate from the vaginal walls. This initially forms as sweat-like droplets, and is caused by increased fluid pressure in the tissue of the vagina (vasocongestion), resulting in the release of plasma as transudate from the capillaries through the vaginal epithelium.[54][55][56]

Before and during ovulation, the mucous glands within the cervix secrete different variations of mucus, which provides an alkaline, fertile environment in the vaginal canal that is favorable to the survival of sperm.[57] Following menopause, vaginal lubrication naturally decreases.[58]

Sexual stimulation

[edit]Nerve endings in the vagina can provide pleasurable sensations when the vagina is stimulated during sexual activity. Women may derive pleasure from one part of the vagina, or from a feeling of closeness and fullness during vaginal penetration.[59] Because the vagina is not rich in nerve endings, women often do not receive sufficient sexual stimulation, or orgasm, solely from vaginal penetration.[59][60][61] Although the literature commonly cites a greater concentration of nerve endings and therefore greater sensitivity near the vaginal entrance (the outer one-third or lower third),[60][61][62] some scientific examinations of vaginal wall innervation indicate no single area with a greater density of nerve endings.[63][64] Other research indicates that only some women have a greater density of nerve endings in the anterior vaginal wall.[63][65] Because of the fewer nerve endings in the vagina, childbirth pain is significantly more tolerable.[61][66][67]

Pleasure can be derived from the vagina in a variety of ways. In addition to penile penetration, pleasure can come from masturbation, fingering, or specific sex positions (such as the missionary position or the spoons sex position).[68] Heterosexual couples may engage in fingering as a form of foreplay to incite sexual arousal or as an accompanying act,[69][70] or as a type of birth control, or to preserve virginity.[71][72] Less commonly, they may use non penile-vaginal sexual acts as a primary means of sexual pleasure.[70] In contrast, lesbians and other women who have sex with women commonly engage in fingering as a main form of sexual activity.[73][74] Some women and couples use sex toys, such as a vibrator or dildo, for vaginal pleasure.[75]

Most women require direct stimulation of the clitoris to orgasm.[60][61] The clitoris plays a part in vaginal stimulation. It is a sex organ of multiplanar structure containing an abundance of nerve endings, with a broad attachment to the pubic arch and extensive supporting tissue to the labia. Research indicates that it forms a tissue cluster with the vagina. This tissue is perhaps more extensive in some women than in others, which may contribute to orgasms experienced vaginally.[60][76][77]

During sexual arousal, and particularly the stimulation of the clitoris, the walls of the vagina lubricate. This begins after ten to thirty seconds of sexual arousal, and increases in amount the longer the woman is aroused.[78] It reduces friction or injury that can be caused by insertion of the penis into the vagina or other penetration of the vagina during sexual activity. The vagina lengthens during the arousal, and can continue to lengthen in response to pressure; as the woman becomes fully aroused, the vagina expands in length and width, while the cervix retracts.[78][79] With the upper two-thirds of the vagina expanding and lengthening, the uterus rises into the greater pelvis, and the cervix is elevated above the vaginal floor, resulting in tenting of the mid-vaginal plane.[78] This is known as the tenting or ballooning effect.[80] As the elastic walls of the vagina stretch or contract, with support from the pelvic muscles, to wrap around the inserted penis (or other object),[62] this creates friction for the penis and helps to cause a man to experience orgasm and ejaculation, which in turn enables fertilization.[81]

An area in the vagina that may be an erogenous zone is the G-spot. It is typically defined as being located at the anterior wall of the vagina, a couple or few inches in from the entrance, and some women experience intense pleasure, and sometimes an orgasm, if this area is stimulated during sexual activity.[63][65] A G-spot orgasm may be responsible for female ejaculation, leading some doctors and researchers to believe that G-spot pleasure comes from the Skene's glands, a female homologue of the prostate, rather than any particular spot on the vaginal wall; other researchers consider the connection between the Skene's glands and the G-spot area to be weak.[63][64][65] The G-spot's existence (and existence as a distinct structure) is still under dispute because reports of its location can vary from woman to woman, it appears to be nonexistent in some women, and it is hypothesized to be an extension of the clitoris and therefore the reason for orgasms experienced vaginally.[63][66][77]

Childbirth

[edit]The vagina is the birth canal for the delivery of a baby. When labor nears, several signs may occur, including vaginal discharge and the rupture of membranes (water breaking). The latter results in a gush or small stream of amniotic fluid from the vagina.[82] Water breaking most commonly happens at the beginning of labor. It happens before labor if there is a premature rupture of membranes, which occurs in 10% of cases.[83] Among women giving birth for the first time, Braxton Hicks contractions are mistaken for actual contractions,[84] but they are instead a way for the body to prepare for true labor. They do not signal the beginning of labor,[85] but they are usually very strong in the days leading up to labor.[84][85]

As the body prepares for childbirth, the cervix softens, thins, moves forward to face the front, and begins to open. This allows the fetus to settle into the pelvis, a process known as lightening.[86] As the fetus settles into the pelvis, pain from the sciatic nerves, increased vaginal discharge, and increased urinary frequency can occur.[86] While lightening is likelier to happen after labor has begun for women who have given birth before, it may happen ten to fourteen days before labor in women experiencing labor for the first time.[87]

The fetus begins to lose the support of the cervix when contractions begin. With cervical dilation reaching 10 cm to accommodate the head of the fetus, the head moves from the uterus to the vagina.[82][88] The elasticity of the vagina allows it to stretch to many times its normal diameter in order to deliver the child.[89]

Vaginal births are more common, but if there is a risk of complications a caesarean section (C-section) may be performed.[90] The vaginal mucosa has an abnormal accumulation of fluid (edematous) and is thin, with few rugae, a little after birth. The mucosa thickens and rugae return in approximately three weeks once the ovaries regain usual function and estrogen flow is restored. The vaginal opening gapes and is relaxed, until it returns to its approximate pre-pregnant state six to eight weeks after delivery, known as the postpartum period; however, the vagina will continue to be larger in size than it was previously.[91]

After giving birth, there is a phase of vaginal discharge called lochia that can vary significantly in the amount of loss and its duration but can go on for up to six weeks.[92]

Vaginal microbiota

[edit]

The vaginal flora is a complex ecosystem that changes throughout life, from birth to menopause. The vaginal microbiota resides in and on the outermost layer of the vaginal epithelium.[44] This microbiome consists of species and genera, which typically do not cause symptoms or infections in women with normal immunity. The vaginal microbiome is dominated by Lactobacillus species.[93] These species metabolize glycogen, breaking it down into sugar. Lactobacilli metabolize the sugar into glucose and lactic acid.[94] Under the influence of hormones, such as estrogen, progesterone and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), the vaginal ecosystem undergoes cyclic or periodic changes.[94]

Clinical significance

[edit]Pelvic examinations

[edit]

Vaginal health can be assessed during a pelvic examination, along with the health of most of the organs of the female reproductive system.[95][96][97] Such exams may include the Pap test (or cervical smear). In the United States, Pap test screening is recommended starting around 21 years of age until the age of 65.[98] However, other countries do not recommend pap testing in non-sexually active women.[99] Guidelines on frequency vary from every three to five years.[99][100][101] Routine pelvic examination on women who are not pregnant and lack symptoms may be more harmful than beneficial.[102] A normal finding during the pelvic exam of a pregnant woman is a bluish tinge to the vaginal wall.[95]

Pelvic exams are most often performed when there are unexplained symptoms of discharge, pain, unexpected bleeding or urinary problems.[95][103][104] During a pelvic exam, the vaginal opening is assessed for position, symmetry, presence of the hymen, and shape. The vagina is assessed internally by the examiner with gloved fingers, before the speculum is inserted, to note the presence of any weakness, lumps or nodules. Inflammation and discharge are noted if present. During this time, the Skene's and Bartolin's glands are palpated to identify abnormalities in these structures. After the digital examination of the vagina is complete, the speculum, an instrument to visualize internal structures, is carefully inserted to make the cervix visible.[95] Examination of the vagina may also be done during a cavity search.[105]

Lacerations or other injuries to the vagina can occur during sexual assault or other sexual abuse.[4][95] These can be tears, bruises, inflammation and abrasions. Sexual assault with objects can damage the vagina and X-ray examination may reveal the presence of foreign objects.[4] If consent is given, a pelvic examination is part of the assessment of sexual assault.[106] Pelvic exams are also performed during pregnancy, and women with high risk pregnancies have exams more often.[95][107]

Medications

[edit]Intravaginal administration is a route of administration where the medication is inserted into the vagina as a creme or tablet. Pharmacologically, this has the potential advantage of promoting therapeutic effects primarily in the vagina or nearby structures (such as the vaginal portion of cervix) with limited systemic adverse effects compared to other routes of administration.[108][109] Medications used to ripen the cervix and induce labor are commonly administered via this route, as are estrogens, contraceptive agents, propranolol, and antifungals. Vaginal rings can also be used to deliver medication, including birth control in contraceptive vaginal rings. These are inserted into the vagina and provide continuous, low dose and consistent drug levels in the vagina and throughout the body.[110][111]

Before the baby emerges from the womb, an injection for pain control during childbirth may be administered through the vaginal wall and near the pudendal nerve. Because the pudendal nerve carries motor and sensory fibers that innervate the pelvic muscles, a pudendal nerve block relieves birth pain. The medicine does not harm the child, and is without significant complications.[112]

Infections, diseases, and safe sex

[edit]Vaginal infections or diseases include yeast infection, vaginitis, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and cancer. Lactobacillus gasseri and other Lactobacillus species in the vaginal flora provide some protection from infections by their secretion of bacteriocins and hydrogen peroxide.[113] The healthy vagina of a woman of child-bearing age is acidic, with a pH normally ranging between 3.8 and 4.5.[94] The low pH prohibits growth of many strains of pathogenic microbes.[94] The acidic balance of the vagina may also be affected by semen,[114][115] pregnancy, menstruation, diabetes or other illness, birth control pills, certain antibiotics, poor diet, and stress.[116] Any of these changes to the acidic balance of the vagina may contribute to yeast infection.[117] An elevated pH (greater than 4.5) of the vaginal fluid can be caused by an overgrowth of bacteria as in bacterial vaginosis, or in the parasitic infection trichomoniasis, both of which have vaginitis as a symptom.[94][118] Vaginal flora populated by a number of different bacteria characteristic of bacterial vaginosis increases the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes.[119] During a pelvic exam, samples of vaginal fluids may be taken to screen for sexually transmitted infections or other infections.[95][120]

Because the vagina is self-cleansing, it usually does not need special hygiene.[121] Clinicians generally discourage the practice of douching for maintaining vulvovaginal health.[121][122] Since the vaginal flora gives protection against disease, a disturbance of this balance may lead to infection and abnormal discharge.[121] Vaginal discharge may indicate a vaginal infection by color and odor, or the resulting symptoms of discharge, such as irritation or burning.[123][124] Abnormal vaginal discharge may be caused by STIs, diabetes, douches, fragranced soaps, bubble baths, birth control pills, yeast infection (commonly as a result of antibiotic use) or another form of vaginitis.[123] While vaginitis is an inflammation of the vagina, and is attributed to infection, hormonal issues, or irritants,[125][126] vaginismus is an involuntary tightening of the vagina muscles during vaginal penetration that is caused by a conditioned reflex or disease.[125] Vaginal discharge due to yeast infection is usually thick, creamy in color and odorless, while discharge due to bacterial vaginosis is gray-white in color, and discharge due to trichomoniasis is usually a gray color, thin in consistency, and has a fishy odor. Discharge in 25% of the trichomoniasis cases is yellow-green.[124]

HIV/AIDS, human papillomavirus (HPV), genital herpes and trichomoniasis are some STIs that may affect the vagina, and health sources recommend safe sex (or barrier method) practices to prevent the transmission of these and other STIs.[127][128] Safe sex commonly involves the use of condoms, and sometimes female condoms (which give women more control). Both types can help avert pregnancy by preventing semen from coming in contact with the vagina.[129][130] There is, however, little research on whether female condoms are as effective as male condoms at preventing STIs,[130] and they are slightly less effective than male condoms at preventing pregnancy, which may be because the female condom fits less tightly than the male condom or because it can slip into the vagina and spill semen.[131]

The vaginal lymph nodes often trap cancerous cells that originate in the vagina. These nodes can be assessed for the presence of disease. Selective surgical removal (rather than total and more invasive removal) of vaginal lymph nodes reduces the risk of complications that can accompany more radical surgeries. These selective nodes act as sentinel lymph nodes.[48] Instead of surgery, the lymph nodes of concern are sometimes treated with radiation therapy administered to the patient's pelvic, inguinal lymph nodes, or both.[132]

Vaginal cancer and vulvar cancer are very rare, and primarily affect older women.[133][134] Cervical cancer (which is relatively common) increases the risk of vaginal cancer,[135] which is why there is a significant chance for vaginal cancer to occur at the same time as, or after, cervical cancer. It may be that their causes are the same.[135][133][136] Cervical cancer may be prevented by pap smear screening and HPV vaccines, but HPV vaccines only cover HPV types 16 and 18, the cause of 70% of cervical cancers.[137][138] Some symptoms of cervical and vaginal cancer are dyspareunia, and abnormal vaginal bleeding or vaginal discharge, especially after sexual intercourse or menopause.[139][140] However, most cervical cancers are asymptomatic (present no symptoms).[139] Vaginal intracavity brachytherapy (VBT) is used to treat endometrial, vaginal and cervical cancer. An applicator is inserted into the vagina to allow the administration of radiation as close to the site of the cancer as possible.[141][142] Survival rates increase with VBT when compared to external beam radiation therapy.[141] By using the vagina to place the emitter as close to the cancerous growth as possible, the systemic effects of radiation therapy are reduced and cure rates for vaginal cancer are higher.[143] Research is unclear on whether treating cervical cancer with radiation therapy increases the risk of vaginal cancer.[135]

Effects of aging and childbirth

[edit]Age and hormone levels significantly correlate with the pH of the vagina.[144] Estrogen, glycogen and lactobacilli impact these levels.[145][146] At birth, the vagina is acidic with a pH of approximately 4.5,[144] and ceases to be acidic by three to six weeks of age,[147] becoming alkaline.[148] Average vaginal pH is 7.0 in pre-pubertal girls.[145] Although there is a high degree of variability in timing, girls who are approximately seven to twelve years of age will continue to have labial development as the hymen thickens and the vagina elongates to approximately 8 cm. The vaginal mucosa thickens and the vaginal pH becomes acidic again. Girls may also experience a thin, white vaginal discharge called leukorrhea.[148] The vaginal microbiota of adolescent girls aged 13 to 18 years is similar to women of reproductive age,[146] who have an average vaginal pH of 3.8–4.5,[94] but research is not as clear on whether this is the same for premenarcheal or perimenarcheal girls.[146] The vaginal pH during menopause is 6.5–7.0 (without hormone replacement therapy), or 4.5–5.0 with hormone replacement therapy.[146]

After menopause, the body produces less estrogen. This causes atrophic vaginitis (thinning and inflammation of the vaginal walls),[38][149] which can lead to vaginal itching, burning, bleeding, soreness, or vaginal dryness (a decrease in lubrication).[150] Vaginal dryness can cause discomfort on its own or discomfort or pain during sexual intercourse.[150][151] Hot flashes are also characteristic of menopause.[116][152] Menopause also affects the composition of vaginal support structures. The vascular structures become fewer with advancing age.[153] Specific collagens become altered in composition and ratios. It is thought that the weakening of the support structures of the vagina is due to the physiological changes in this connective tissue.[154]

Menopausal symptoms can be eased by estrogen-containing vaginal creams,[152] non-prescription, non-hormonal medications,[150] vaginal estrogen rings such as the Femring,[155] or other hormone replacement therapies,[152] but there are risks (including adverse effects) associated with hormone replacement therapy.[156][157] Vaginal creams and vaginal estrogen rings may not have the same risks as other hormone replacement treatments.[158] Hormone replacement therapy can treat vaginal dryness,[155] but a personal lubricant may be used to temporarily remedy vaginal dryness specifically for sexual intercourse.[151] Some women have an increase in sexual desire following menopause.[150] It may be that menopausal women who continue to engage in sexual activity regularly experience vaginal lubrication similar to levels in women who have not entered menopause, and can enjoy sexual intercourse fully.[150] They may have less vaginal atrophy and fewer problems concerning sexual intercourse.[159]

Vaginal changes that happen with aging and childbirth include mucosal redundancy, rounding of the posterior aspect of the vagina with shortening of the distance from the distal end of the anal canal to the vaginal opening, diastasis or disruption of the pubococcygeus muscles caused by poor repair of an episiotomy, and blebs that may protrude beyond the area of the vaginal opening.[160] Other vaginal changes related to aging and childbirth are stress urinary incontinence, rectocele, and cystocele.[160] Physical changes resulting from pregnancy, childbirth, and menopause often contribute to stress urinary incontinence. If a woman has weak pelvic floor muscle support and tissue damage from childbirth or pelvic surgery, a lack of estrogen can further weaken the pelvic muscles and contribute to stress urinary incontinence.[161] Pelvic organ prolapse, such as a rectocele or cystocele, is characterized by the descent of pelvic organs from their normal positions to impinge upon the vagina.[162][163] A reduction in estrogen does not cause rectocele, cystocele or uterine prolapse, but childbirth and weakness in pelvic support structures can.[159] Prolapse may also occur when the pelvic floor becomes injured during a hysterectomy, gynecological cancer treatment, or heavy lifting.[162][163] Pelvic floor exercises such as Kegel exercises can be used to strengthen the pelvic floor muscles,[164] preventing or arresting the progression of prolapse.[165] There is no evidence that doing Kegel exercises isotonically or with some form of weight is superior; there are greater risks with using weights since a foreign object is introduced into the vagina.[166]

During the third stage of labor, while the infant is being born, the vagina undergoes significant changes. A gush of blood from the vagina may be seen right before the baby is born. Lacerations to the vagina that can occur during birth vary in depth, severity and the amount of adjacent tissue involvement.[4][167] The laceration can be so extensive as to involve the rectum and anus. This event can be especially distressing to a new mother.[167][168] When this occurs, fecal incontinence develops and stool can leave through the vagina.[167] Close to 85% of spontaneous vaginal births develop some form of tearing. Out of these, 60–70% require suturing.[169][170] Lacerations from labor do not always occur.[44]

Surgery

[edit]The vagina, including the vaginal opening, may be altered as a result of surgeries such as an episiotomy, vaginectomy, vaginoplasty or labiaplasty.[160][171] Those who undergo vaginoplasty are usually older and have given birth.[160] A thorough examination of the vagina before a vaginoplasty is standard, as well as a referral to a urogynecologist to diagnose possible vaginal disorders.[160] With regard to labiaplasty, reduction of the labia minora is quick without hindrance, complications are minor and rare, and can be corrected. Any scarring from the procedure is minimal, and long-term problems have not been identified.[160]

During an episiotomy, a surgical incision is made during the second stage of labor to enlarge the vaginal opening for the baby to pass through.[44][141] Although its routine use is no longer recommended,[172] and not having an episiotomy is found to have better results than an episiotomy,[44] it is one of the most common medical procedures performed on women. The incision is made through the skin, vaginal epithelium, subcutaneous fat, perineal body and superficial transverse perineal muscle and extends from the vagina to the anus.[173][174] Episiotomies can be painful after delivery. Women often report pain during sexual intercourse up to three months after laceration repair or an episiotomy.[169][170] Some surgical techniques result in less pain than others.[169] The two types of episiotomies performed are the medial incision and the medio-lateral incision. The median incision is a perpendicular cut between the vagina and the anus and is the most common.[44][175] The medio-lateral incision is made between the vagina at an angle and is not as likely to tear through to the anus. The medio-lateral cut takes more time to heal than the median cut.[44]

Vaginectomy is surgery to remove all or part of the vagina, and is usually used to treat malignancy.[171] Removal of some or all of the sexual organs can result in damage to the nerves and leave behind scarring or adhesions.[176] Sexual function may also be impaired as a result, as in the case of some cervical cancer surgeries. These surgeries can impact pain, elasticity, vaginal lubrication and sexual arousal. This often resolves after one year but may take longer.[176]

Women, especially those who are older and have had multiple births, may choose to surgically correct vaginal laxity. This surgery has been described as vaginal tightening or rejuvenation.[177] While a woman may experience an improvement in self-image and sexual pleasure by undergoing vaginal tightening or rejuvenation,[177] there are risks associated with the procedures, including infection, narrowing of the vaginal opening, insufficient tightening, decreased sexual function (such as pain during sexual intercourse), and rectovaginal fistula. Women who undergo this procedure may unknowingly have a medical issue, such as a prolapse, and an attempt to correct this is also made during the surgery.[178]

Surgery on the vagina can be elective or cosmetic. Women who seek cosmetic surgery can have congenital conditions, physical discomfort or wish to alter the appearance of their genitals. Concerns over average genital appearance or measurements are largely unavailable and make defining a successful outcome for such surgery difficult.[179] A number of sex reassignment surgeries are available to transgender people. Although not all intersex conditions require surgical treatment, some choose genital surgery to correct atypical anatomical conditions.[180]

Anomalies and other health issues

[edit]

Vaginal anomalies are defects that result in an abnormal or absent vagina.[181][182] The most common obstructive vaginal anomaly is an imperforate hymen, a condition in which the hymen obstructs menstrual flow or other vaginal secretions.[183][184] Another vaginal anomaly is a transverse vaginal septum, which partially or completely blocks the vaginal canal.[183] The precise cause of an obstruction must be determined before it is repaired, since corrective surgery differs depending on the cause.[185] In some cases, such as isolated vaginal agenesis, the external genitalia may appear normal.[186]

Abnormal openings known as fistulas can cause urine or feces to enter the vagina, resulting in incontinence.[187][188] The vagina is susceptible to fistula formation because of its proximity to the urinary and gastrointestinal tracts.[189] Specific causes are manifold and include obstructed labor, hysterectomy, malignancy, radiation, episiotomy, and bowel disorders.[190][191] A small number of vaginal fistulas are congenital.[192] Various surgical methods are employed to repair fistulas.[193][187] Untreated, fistulas can result in significant disability and have a profound impact on quality of life.[187]

Vaginal evisceration is a serious complication of a vaginal hysterectomy and occurs when the vaginal cuff ruptures, allowing the small intestine to protrude from the vagina.[106][194]

Cysts may also affect the vagina. Various types of vaginal cysts can develop on the surface of the vaginal epithelium or in deeper layers of the vagina and can grow to be as large as 7 cm.[195][196] Often, they are an incidental finding during a routine pelvic examination.[197] Vaginal cysts can mimic other structures that protrude from the vagina such as a rectocele and cystocele.[195] Cysts that can be present include Müllerian cysts, Gartner's duct cysts, and epidermoid cysts.[198][199] A vaginal cyst is most likely to develop in women between the ages of 30 and 40.[195] It is estimated that 1 out of 200 women has a vaginal cyst.[195][200] The Bartholin's cyst is of vulvar rather than vaginal origin,[201] but it presents as a lump at the vaginal opening.[202] It is more common in younger women and is usually without symptoms,[203] but it can cause pain if an abscess forms,[203] block the entrance to the vulval vestibule if large,[204] and impede walking or cause painful sexual intercourse.[203]

Society and culture

[edit]Perceptions, symbolism and vulgarity

[edit]Various perceptions of the vagina have existed throughout history, including the belief it is the center of sexual desire, a metaphor for life via birth, inferior to the penis, unappealing to sight or smell, or vulgar.[205][206][207] These views can largely be attributed to sex differences, and how they are interpreted. David Buss, an evolutionary psychologist, stated that because a penis is significantly larger than a clitoris and is readily visible while the vagina is not, and males urinate through the penis, boys are taught from childhood to touch their penises while girls are often taught that they should not touch their own genitalia, which implies that there is harm in doing so. Buss attributed this as the reason many women are not as familiar with their genitalia, and that researchers assume these sex differences explain why boys learn to masturbate before girls and do so more often.[208]

The word vagina is commonly avoided in conversation,[209] and many people are confused about the vagina's anatomy and may be unaware that it is not used for urination.[210][211][212] This is exacerbated by phrases such as "boys have a penis, girls have a vagina", which causes children to think that girls have one orifice in the pelvic area.[211] Author Hilda Hutcherson stated, "Because many [women] have been conditioned since childhood through verbal and nonverbal cues to think of [their] genitals as ugly, smelly and unclean, [they] aren't able to fully enjoy intimate encounters" because of fear that their partner will dislike the sight, smell, or taste of their genitals. She argued that women, unlike men, did not have locker room experiences in school where they compared each other's genitals, which is one reason so many women wonder if their genitals are normal.[206] Scholar Catherine Blackledge stated that having a vagina meant she would typically be treated less well than her vagina-less counterparts and subject to inequalities (such as job inequality), which she categorized as being treated like a second-class citizen.[209]

Negative views of the vagina are simultaneously contrasted by views that it is a powerful symbol of female sexuality, spirituality, or life. Author Denise Linn stated that the vagina "is a powerful symbol of womanliness, openness, acceptance, and receptivity. It is the inner valley spirit".[213] Sigmund Freud placed significant value on the vagina,[214] postulating the concept that vaginal orgasm is separate from clitoral orgasm, and that, upon reaching puberty, the proper response of mature women is a changeover to vaginal orgasms (meaning orgasms without any clitoral stimulation). This theory made many women feel inadequate, as the majority of women cannot achieve orgasm via vaginal intercourse alone.[215][216][217] Regarding religion, the womb represents a powerful symbol as the yoni in Hinduism, which represents "the feminine potency", and this may indicate the value that Hindu society has given female sexuality and the vagina's ability to deliver life;[218] however, yoni as a representation of "womb" is not the primary denotation.[219]

While, in ancient times, the vagina was often considered equivalent (homologous) to the penis, with anatomists Galen (129 AD – 200 AD) and Vesalius (1514–1564) regarding the organs as structurally the same except for the vagina being inverted, anatomical studies over latter centuries showed the clitoris to be the penile equivalent.[76][220] Another perception of the vagina was that the release of vaginal fluids would cure or remedy a number of ailments; various methods were used over the centuries to release "female seed" (via vaginal lubrication or female ejaculation) as a treatment for suffocatio ex semine retento (suffocation of the womb, lit. 'suffocation from retained seed'), green sickness, and possibly for female hysteria. Reported methods for treatment included a midwife rubbing the walls of the vagina or insertion of the penis or penis-shaped objects into the vagina. Symptoms of the female hysteria diagnosis – a concept that is no longer recognized by medical authorities as a medical disorder – included faintness, nervousness, insomnia, fluid retention, heaviness in abdomen, muscle spasm, shortness of breath, irritability, loss of appetite for food or sex, and a propensity for causing trouble.[221] It may be that women who were considered suffering from female hysteria condition would sometimes undergo "pelvic massage" – stimulation of the genitals by the doctor until the woman experienced "hysterical paroxysm" (i.e., orgasm). In this case, paroxysm was regarded as a medical treatment, and not a sexual release.[221]

The vagina has been given many vulgar names, three of which are pussy, twat, and cunt. Cunt is also used as a derogatory epithet referring to people of either sex. This usage is relatively recent, dating from the late nineteenth century.[222] Reflecting different national usages, cunt is described as "an unpleasant or stupid person" in the Compact Oxford English Dictionary,[223] whereas the Merriam-Webster has a usage of the term as "usually disparaging and obscene: woman",[224] noting that it is used in the United States as "an offensive way to refer to a woman".[225] Random House defines it as "a despicable, contemptible or foolish man".[222] Some feminists of the 1970s sought to eliminate disparaging terms such as cunt.[226] Twat is widely used as a derogatory epithet, especially in British English, referring to a person considered obnoxious or stupid.[227][228] Pussy can indicate "cowardice or weakness", and "the human vulva or vagina" or by extension "sexual intercourse with a woman".[229] In English, the use of the word pussy to refer to women is considered derogatory or demeaning, treating people as sexual objects.[230]

In literature and art

[edit]The vagina loquens, or "talking vagina", is a significant tradition in literature and art, dating back to the ancient folklore motifs of the "talking cunt".[231][232] These tales usually involve vaginas talking by the effect of magic or charms, and often admitting to their lack of chastity.[231] Other folk tales relate the vagina as having teeth – vagina dentata (Latin for "toothed vagina"). These carry the implication that sexual intercourse might result in injury, emasculation, or castration for the man involved. These stories were frequently told as cautionary tales warning of the dangers of unknown women and to discourage rape.[233]

In 1966, the French artist Niki de Saint Phalle collaborated with Dadaist artist Jean Tinguely and Per Olof Ultvedt on a large sculpture installation entitled "hon-en katedral" (also spelled "Hon-en-Katedrall", which means "she-a cathedral") for Moderna Museet, in Stockholm, Sweden. The outer form is a giant, reclining sculpture of a woman which visitors can enter through a door-sized vaginal opening between her spread legs.[234]

The Vagina Monologues, a 1996 episodic play by Eve Ensler, has contributed to making female sexuality a topic of public discourse. It is made up of a varying number of monologues read by a number of women. Initially, Ensler performed every monologue herself, with subsequent performances featuring three actresses; latter versions feature a different actress for every role. Each of the monologues deals with an aspect of the feminine experience, touching on matters such as sexual activity, love, rape, menstruation, female genital mutilation, masturbation, birth, orgasm, the various common names for the vagina, or simply as a physical aspect of the body. A recurring theme throughout the pieces is the vagina as a tool of female empowerment, and the ultimate embodiment of individuality.[235][236]

Influence on modification

[edit]Societal views, influenced by tradition, a lack of knowledge on anatomy, or sexism, can significantly impact a person's decision to alter their own or another person's genitalia.[178][237] Women may want to alter their genitalia (vagina or vulva) because they believe that its appearance, such as the length of the labia minora covering the vaginal opening, is not normal, or because they desire a smaller vaginal opening or tighter vagina. Women may want to remain youthful in appearance and sexual function. These views are often influenced by the media,[178][238] including pornography,[238] and women can have low self-esteem as a result.[178] They may be embarrassed to be naked in front of a sexual partner and may insist on having sex with the lights off.[178] When modification surgery is performed purely for cosmetic reasons, it is often viewed poorly,[178] and some doctors have compared such surgeries to female genital mutilation (FGM).[238]

Female genital mutilation, also known as female circumcision or female genital cutting, is genital modification with no health benefits.[239][240] The most severe form is Type III FGM, which is infibulation and involves removing all or part of the labia and the vagina being closed up. A small hole is left for the passage of urine and menstrual blood, and the vagina is opened up for sexual intercourse and childbirth.[240]

Significant controversy surrounds female genital mutilation,[239][240] with the World Health Organization (WHO) and other health organizations campaigning against the procedures on behalf of human rights, stating that it is "a violation of the human rights of girls and women" and "reflects deep-rooted inequality between the sexes".[240] Female genital mutilation has existed at one point or another in almost all human civilizations,[241] most commonly to exert control over the sexual behavior, including masturbation, of girls and women.[240][241] It is carried out in several countries, especially in Africa, and to a lesser extent in other parts of the Middle East and Southeast Asia, on girls from a few days old to mid-adolescent, often to reduce sexual desire in an effort to preserve vaginal virginity.[239][240][241] Comfort Momoh stated it may be that female genital mutilation was "practiced in ancient Egypt as a sign of distinction among the aristocracy"; there are reports that traces of infibulation are on Egyptian mummies.[241]

Custom and tradition are the most frequently cited reasons for the practice of female genital mutilation. Some cultures believe that female genital mutilation is part of a girl's initiation into adulthood and that not performing it can disrupt social and political cohesion.[240][241] In these societies, a girl is often not considered an adult unless she has undergone the procedure.[240]

Other animals

[edit]

The vagina is a structure of animals in which the female is internally fertilized, rather than by traumatic insemination used by some invertebrates. Although research on the vagina is especially lacking for different animals, its location, structure and size are documented as varying among species. In therian mammals (placentals and marsupials), the vagina leads from the uterus to the exterior of the female body. Female placentals have two openings in the vulva; these are the urethral opening for the urinary tract and the vaginal opening for the genital tract. Depending on the species, these openings may be within the internal urogenital sinus or on the external vestibule.[242] Female marsupials have two lateral vaginas, which lead to separate uteri, but both open externally through the same orifice;[243] a third canal, which is known as the median vagina, and can be transitory or permanent, is used for birth.[244] The female spotted hyena does not have an external vaginal opening. Instead, the vagina exits through the clitoris, allowing the females to urinate, copulate and give birth through the clitoris.[245] In female canids, the vagina contracts during copulation, forming a copulatory tie.[246] Female cetaceans have vaginal folds that are not found in other mammals.[247][248]

Monotremes, birds, reptiles and amphibians have a cloaca and is the single external opening for the gastrointestinal, urinary, and reproductive tracts. Some of these vertebrates have a part of the oviduct that leads to the cloaca.[249][250] Chickens have a vaginal aperture that opens from the vertical apex of the cloaca. The vagina extends upward from the aperture and becomes the egg gland.[250] In some jawless fish, there is neither oviduct nor vagina and instead the egg travels directly through the body cavity (and is fertilised externally as in most fish and amphibians). In insects and other invertebrates, the vagina can be a part of the oviduct (see insect reproductive system).[251] Birds have a cloaca into which the urinary, reproductive tract (vagina) and gastrointestinal tract empty.[252] Females of some waterfowl species have developed vaginal structures called dead end sacs and clockwise coils to protect themselves from sexual coercion.[253]

A lack of research on the vagina and other female genitalia, especially for different animals, has stifled knowledge on female sexual anatomy.[254][255] One explanation for why male genitalia is studied more includes penises being significantly simpler to analyze than female genital cavities, because male genitals usually protrude and are therefore easier to assess and measure. By contrast, female genitals are more often concealed, and require more dissection, which in turn requires more time.[254] Another explanation is that a main function of the penis is to impregnate, while female genitals may alter shape upon interaction with male organs, especially as to benefit or hinder reproductive success.[254]

Non-human primates are optimal models for human biomedical research because humans and non-human primates share physiological characteristics as a result of evolution.[256] While menstruation is heavily associated with human females, and they have the most pronounced menstruation, it is also typical of ape relatives and monkeys.[257][258] Female macaques menstruate, with a cycle length over the course of a lifetime that is comparable to that of female humans. Estrogens and progestogens in the menstrual cycles and during premenarche and postmenopause are also similar in female humans and macaques; however, only in macaques does keratinization of the epithelium occur during the follicular phase.[256] The vaginal pH of macaques also differs, with near-neutral to slightly alkaline median values and is widely variable, which may be due to its lack of lactobacilli in the vaginal flora.[256] This is one reason why, although macaques are used for studying HIV transmission and testing microbicides,[256] animal models are not often used in the study of sexually transmitted infections, such as trichomoniasis. Another is that such conditions' causes are inextricably bound to humans' genetic makeup, making results from other species difficult to apply to humans.[259]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Stevenson A (2010). Oxford Dictionary of English. Oxford University Press. p. 1962. ISBN 978-0-19-957112-3. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ Nevid J, Rathus S, Rubenstein H (1998). Health in the New Millennium: The Smart Electronic Edition (S.E.E.). Macmillan. p. 297. ISBN 978-1-57259-171-4. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ Lipsky MS (2006). American Medical Association Concise Medical Encyclopedia. Random House Reference. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-375-72180-9. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dalton M (2014). Forensic Gynaecology. Cambridge University Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-107-06429-4. Archived from the original on September 17, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ Jones T, Wear D, Friedman LD (2014). Health Humanities Reader. Rutgers University Press. pp. 231–232. ISBN 978-0-8135-7367-0. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick M (2012). Human Sexuality: Personality and Social Psychological Perspectives. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 175. ISBN 978-1-4684-3656-3. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

- ^ Hill CA (2007). Human Sexuality: Personality and Social Psychological Perspectives. SAGE Publications. pp. 265–266. ISBN 978-1-5063-2012-0. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

Little thought apparently has been devoted to the nature of female genitals in general, likely accounting for the reason that most people use incorrect terms when referring to female external genitals. The term typically used to talk about female genitals is vagina, which is actually an internal sexual structure, the muscular passageway leading outside from the uterus. The correct term for the female external genitals is vulva, as discussed in chapter 6, which includes the clitoris, labia majora, and labia minora.

- ^ Sáenz-Herrero M (2014). Psychopathology in Women: Incorporating Gender Perspective into Descriptive Psychopathology. Springer. p. 250. ISBN 978-3-319-05870-2. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

In addition, there is a current lack of appropriate vocabulary to refer to the external female genitals, using, for example, 'vagina' and 'vulva' as if they were synonyms, as if using these terms incorrectly were harmless to the sexual and psychological development of women.'

- ^ a b c d e f g Snell RS (2004). Clinical Anatomy: An Illustrated Review with Questions and Explanations. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-7817-4316-7. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Dutta DC (2014). DC Dutta's Textbook of Gynecology. JP Medical Ltd. pp. 2–7. ISBN 978-93-5152-068-9. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ Drake R, Vogl AW, Mitchell A (2016). Gray's Basic Anatomy E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-323-50850-6. Archived from the original on June 4, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- ^ a b Ginger VA, Yang CC (2011). "Functional Anatomy of the Female Sex Organs". In Mulhall JP, Incrocci L, Goldstein I, Rosen R (eds.). Cancer and Sexual Health. Springer. pp. 13, 20–21. ISBN 978-1-60761-915-4. Archived from the original on December 16, 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ Ransons A (May 15, 2009). "Reproductive Choices". Health and Wellness for Life. Human Kinetics 10%. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-7360-6850-5. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ Beckmann CR (2010). Obstetrics and Gynecology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-7817-8807-6. Archived from the original on February 15, 2017. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

Because the vagina is collapsed, it appears H-shaped in cross section.

- ^ a b c d e f Standring S, Borley NR, eds. (2008). Gray's anatomy: the anatomical basis of clinical practice (40th ed.). London: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 1281–4. ISBN 978-0-8089-2371-8.

- ^ a b Baggish MS, Karram MM (2011). Atlas of Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 582. ISBN 978-1-4557-1068-3. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ^ a b Arulkumaran S, Regan L, Papageorghiou A, Monga A, Farquharson D (2011). Oxford Desk Reference: Obstetrics and Gynaecology. OUP Oxford. p. 472. ISBN 978-0-19-162087-4. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ^ a b Manual of Obstetrics (3rd ed.). Elsevier. 2011. pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-81-312-2556-1.

- ^ Smith RP, Turek P (2011). Netter Collection of Medical Illustrations: Reproductive System E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 443. ISBN 978-1-4377-3648-9. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ^ Ricci, Susan Scott; Kyle, Terri (2009). Maternity and Pediatric Nursing. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-78178-055-1. Retrieved January 7, 2024.

- ^ Zink, Christopher (2011). Dictionary of Obstetrics and Gynecology. De Gruyter. p. 174. ISBN 978-3-11085-727-6.

- ^ a b Knight B (1997). Simpson's Forensic Medicine (11th ed.). London: Arnold. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-7131-4452-9.

- ^ Perlman SE, Nakajyma ST, Hertweck SP (2004). Clinical protocols in pediatric and adolescent gynecology. Parthenon. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-84214-199-1.

- ^ a b Wylie L (2005). Essential Anatomy and Physiology in Maternity Care. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 157–158. ISBN 978-0-443-10041-3. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ Emans SJ (2000). "Physical Examination of the Child and Adolescent". Evaluation of the Sexually Abused Child: A Medical Textbook and Photographic Atlas (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 61–65. ISBN 978-0-19-974782-5. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved August 2, 2015.

- ^ a b c Edmonds K (2012). Dewhurst's Textbook of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 423. ISBN 978-0-470-65457-6. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ Herrington CS (2017). Pathology of the Cervix. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-3-319-51257-0. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Woodruff TJ, Janssen SJ, Guillette LJ, Jr, Giudice LC (2010). Environmental Impacts on Reproductive Health and Fertility. Cambridge University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-139-48484-8. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ a b c Robboy S, Kurita T, Baskin L, Cunha GR (2017). "New insights into human female reproductive tract development". Differentiation. 97: 9–22. doi:10.1016/j.diff.2017.08.002. ISSN 0301-4681. PMC 5712241. PMID 28918284.

- ^ a b Grimbizis GF, Campo R, Tarlatzis BC, Gordts S (2015). Female Genital Tract Congenital Malformations: Classification, Diagnosis and Management. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-4471-5146-3. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ Kurman RJ (2013). Blaustein's Pathology of the Female Genital Tract. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-4757-3889-6. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ Brown L (2012). Pathology of the Vulva and Vagina. Springer Science+Business Media. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-85729-757-0. Archived from the original on April 25, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ a b Arulkumaran S, Regan L, Papageorghiou A, Monga A, Farquharson D (2011). Oxford Desk Reference: Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Oxford University Press. p. 471. ISBN 978-0-19-162087-4. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ Bitzer J, Lipshultz L, Pastuszak A, Goldstein A, Giraldi A, Perelman M (2016). "The Female Sexual Response: Anatomy and Physiology of Sexual Desire, Arousal, and Orgasm in Women". Management of Sexual Dysfunction in Men and Women. Springer New York. p. 202. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-3100-2_18. ISBN 978-1-4939-3099-9.

- ^ Blaskewicz CD, Pudney J, Anderson DJ (July 2011). "Structure and function of intercellular junctions in human cervical and vaginal mucosal epithelia". Biology of Reproduction. 85 (1): 97–104. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.110.090423. PMC 3123383. PMID 21471299.

- ^ Mayeaux EJ, Cox JT (2011). Modern Colposcopy Textbook and Atlas. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-4511-5383-5.

- ^ a b c Kurman RJ, ed. (2002). Blaustein's Pathology of the Female Genital Tract (5th ed.). Springer. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-387-95203-1. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ a b c Beckmann CR (2010). Obstetrics and Gynecology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 241–245. ISBN 978-0-7817-8807-6. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Robboy SJ (2009). Robboy's Pathology of the Female Reproductive Tract. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-443-07477-6. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- ^ Nunn KL, Forney LJ (September 2016). "Unraveling the Dynamics of the Human Vaginal Microbiome". The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 89 (3): 331–337. ISSN 0044-0086. PMC 5045142. PMID 27698617.

- ^ Gupta R (2011). Reproductive and developmental toxicology. London: Academic Press. p. 1005. ISBN 978-0-12-382032-7.

- ^ a b Hall J (2011). Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology (12th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 993. ISBN 978-1-4160-4574-8.

- ^ Gad SC (2008). Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Handbook: Production and Processes. John Wiley & Sons. p. 817. ISBN 978-0-470-25980-1. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Anderson DJ, Marathe J, Pudney J (June 2014). "The Structure of the Human Vaginal Stratum Corneum and its Role in Immune Defense". American Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 71 (6): 618–623. doi:10.1111/aji.12230. ISSN 1600-0897. PMC 4024347. PMID 24661416.

- ^ Dutta DC (2014). DC Dutta's Textbook of Gynecology. JP Medical Ltd. p. 206. ISBN 978-93-5152-068-9. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ a b Zimmern PE, Haab F, Chapple CR (2007). Vaginal Surgery for Incontinence and Prolapse. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-84628-346-8. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- ^ O'Rahilly R (2008). "Blood vessels, nerves and lymphatic drainage of the pelvis". In O'Rahilly R, Müller F, Carpenter S, Swenson R (eds.). Basic Human Anatomy: A Regional Study of Human Structure. Dartmouth Medical School. Archived from the original on December 2, 2017. Retrieved December 13, 2017.

- ^ a b Sabater S, Andres I, Lopez-Honrubia V, Berenguer R, Sevillano M, Jimenez-Jimenez E, Rovirosa A, Arenas M (August 9, 2017). "Vaginal cuff brachytherapy in endometrial cancer – a technically easy treatment?". Cancer Management and Research. 9: 351–362. doi:10.2147/CMAR.S119125. ISSN 1179-1322. PMC 5557121. PMID 28848362.

- ^ "Menstruation and the menstrual cycle fact sheet". Office of Women's Health. December 23, 2014. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- ^ Wangikar P, Ahmed T, Vangala S (2011). "Toxicologic pathology of the reproductive system". In Gupta RC (ed.). Reproductive and developmental toxicology. London: Academic Press. p. 1005. ISBN 978-0-12-382032-7. OCLC 717387050.

- ^ Silverthorn DU (2013). Human Physiology: An Integrated Approach (6th ed.). Glenview, IL: Pearson Education. pp. 850–890. ISBN 978-0-321-75007-5.

- ^ Sherwood L (2013). Human Physiology: From Cells to Systems (8th ed.). Belmont, California: Cengage. pp. 735–794. ISBN 978-1-111-57743-8.

- ^ Vostral SL (2008). Under Wraps: A History of Menstrual Hygiene Technology. Lexington Books. pp. 1–181. ISBN 978-0-7391-1385-1. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ a b Sloane E (2002). Biology of Women. Cengage Learning. pp. 32, 41–42. ISBN 978-0-7668-1142-3. Archived from the original on June 28, 2014. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ Bourcier A, McGuire EJ, Abrams P (2004). Pelvic Floor Disorders. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-7216-9194-7. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Wiederman MW, Whitley BE Jr (2012). Handbook for Conducting Research on Human Sexuality. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-135-66340-7. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Cummings M (2006). Human Heredity: Principles and Issues (Updated ed.). Cengage Learning. pp. 153–154. ISBN 978-0-495-11308-9. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ Sirven JI, Malamut BL (2008). Clinical Neurology of the Older Adult. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 230–232. ISBN 978-0-7817-6947-1. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ a b Lee MT (2013). Love, Sex and Everything in Between. Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd. p. 76. ISBN 978-981-4516-78-5. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Sex and Society. Vol. 2. Marshall Cavendish Corporation. 2009. p. 590. ISBN 978-0-7614-7907-9. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Weiten W, Dunn D, Hammer E (2011). Psychology Applied to Modern Life: Adjustment in the 21st Century. Cengage Learning. p. 386. ISBN 978-1-111-18663-0. Archived from the original on June 14, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ a b Greenberg JS, Bruess CE, Conklin SC (2010). Exploring the Dimensions of Human Sexuality. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 126. ISBN 978-981-4516-78-5. Archived from the original on May 2, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Greenberg JS, Bruess CE, Oswalt SB (2014). Exploring the Dimensions of Human Sexuality. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 102–104. ISBN 978-1-4496-4851-0. Archived from the original on September 10, 2015. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ a b Hines T (August 2001). "The G-Spot: A modern gynecologic myth". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 185 (2): 359–62. doi:10.1067/mob.2001.115995. PMID 11518892. S2CID 32381437.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c Bullough VL, Bullough B (2014). Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 229–231. ISBN 978-1-135-82509-6. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ a b Balon R, Segraves RT (2009). Clinical Manual of Sexual Disorders. American Psychiatric Pub. p. 258. ISBN 978-1-58562-905-3. Archived from the original on June 27, 2014. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ Rosenthal M (2012). Human Sexuality: From Cells to Society. Cengage Learning. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-618-75571-4. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ Carroll J (2012). Discovery Series: Human Sexuality. Cengage Learning. pp. 282–289. ISBN 978-1-111-84189-8. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ Carroll JL (2018). Sexuality Now: Embracing Diversity (1st ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 299. ISBN 978-1-337-67206-1. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2018.

- ^ a b Hales D (2012). An Invitation to Health (1st ed.). Cengage Learning. pp. 296–297. ISBN 978-1-111-82700-7. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2018.

- ^ Strong B, DeVault C, Cohen TF (2010). The Marriage and Family Experience: Intimate Relationship in a Changing Society. Cengage Learning. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-534-62425-5. Archived from the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

Most people agree that we maintain virginity as long as we refrain from sexual (vaginal) intercourse. But occasionally we hear people speak of 'technical virginity' [...] Data indicate that 'a very significant proportion of teens ha[ve] had experience with oral sex, even if they haven't had sexual intercourse, and may think of themselves as virgins' [...] Other research, especially research looking into virginity loss, reports that 35% of virgins, defined as people who have never engaged in vaginal intercourse, have nonetheless engaged in one or more other forms of heterosexual sexual activity (e.g., oral sex, anal sex, or mutual masturbation).

- ^ See 272 Archived May 1, 2016, at the Wayback Machine and page 301 Archived May 7, 2016, at the Wayback Machine for two different definitions of outercourse (first of the pages for no-penetration definition; second of the pages for no-penile-penetration definition). Rosenthal M (2012). Human Sexuality: From Cells to Society (1st ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-618-75571-4. Archived from the original on September 30, 2015. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- ^ Carroll JL (2009). Sexuality Now: Embracing Diversity. Cengage Learning. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-495-60274-3. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ Zenilman J, Shahmanesh M (2011). Sexually Transmitted Infections: Diagnosis, Management, and Treatment. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 329–330. ISBN 978-0-495-81294-4. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ Taormino T (2009). The Big Book of Sex Toys. Quiver. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-59233-355-4. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ a b O'Connell HE, Sanjeevan KV, Hutson JM (October 2005). "Anatomy of the clitoris". The Journal of Urology. 174 (4 Pt 1): 1189–95. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000173639.38898.cd. PMID 16145367. S2CID 26109805.

- Sharon Mascall (June 11, 2006). "Time for rethink on the clitoris". BBC News.

- ^ a b Kilchevsky A, Vardi Y, Lowenstein L, Gruenwald I (January 2012). "Is the Female G-Spot Truly a Distinct Anatomic Entity?". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 9 (3): 719–26. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02623.x. PMID 22240236.

- "G-Spot Does Not Exist, 'Without A Doubt,' Say Researchers". The Huffington Post. January 19, 2012.

- ^ a b c Heffner LJ, Schust DJ (2014). The Reproductive System at a Glance. John Wiley & Sons. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-118-60701-5. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ Silbernagl S, Despopoulos A (2011). Color Atlas of Physiology. Thieme. p. 310. ISBN 978-1-4496-4851-0. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ Carroll JL (2015). Sexuality Now: Embracing Diversity. Cengage Learning. p. 271. ISBN 978-1-305-44603-8. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- ^ Brewster S, Bhattacharya S, Davies J, Meredith S, Preston P (2011). The Pregnant Body Book. Penguin. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-0-7566-8712-0. Archived from the original on May 15, 2015. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- ^ a b Linnard-Palmer, Luanne; Coats, Gloria (2017). Safe Maternity and Pediatric Nursing Care. F. A. Davis Company. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-8036-2494-8.

- ^ Callahan T, Caughey AB (2013). Blueprints Obstetrics and Gynecology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-4511-1702-8. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2018.

- ^ a b Pillitteri A (2013). Maternal and Child Health Nursing: Care of the Childbearing and Childrearing Family. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 298. ISBN 978-1-4698-3322-4. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ a b Raines, Deborah; Cooper, Danielle B. (2021). Braxton Hicks Contractions. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29262073.

- ^ a b Forbes, Helen; Watt, Elizabethl (2020). Jarvis's Health Assessment and Physical Examination (3 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 834. ISBN 978-0-729-58793-8.

- ^ Orshan SA (2008). Maternity, Newborn, and Women's Health Nursing: Comprehensive Care Across the Lifespan. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 585–586. ISBN 978-0-7817-4254-2.