Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Copenhagen

View on Wikipedia

Copenhagen[a] (Danish: København [kʰøpm̩ˈhɑwˀn] ⓘ) is the capital and most populous city in the Kingdom of Denmark, with a population of 1.4 million in the urban area.[8][9] The city is situated mainly on the island of Zealand (Sjælland), with a smaller part on the island of Amager. Copenhagen is separated from Malmö, Sweden, by the Øresund strait. The Øresund Bridge connects the two cities by rail and road.

Key Information

Originally a Viking fishing village established in the 10th century in the vicinity of what is now Gammel Strand, Copenhagen became the capital of Denmark in the early 15th century. During the 16th century, the city served as the de facto capital of the Kalmar Union and the seat of the Union's monarchy, which governed most of the modern-day Nordic region as part of a Danish confederation with Sweden and Norway. The city flourished as the cultural and economic centre of Scandinavia during the Renaissance. By the 17th century, it had become a regional centre of power, serving as the heart of the Danish government and military. During the 18th century, Copenhagen suffered from a devastating plague outbreak and urban conflagrations. Major redevelopment efforts included the construction of the prestigious district of Frederiksstaden and the establishment of cultural institutions such as the Royal Theatre and the Royal Academy of Fine Arts. The city also became the centre of the Danish slave trade during this period. In 1807, the city was bombarded by a British fleet during the Napoleonic Wars, before the Danish Golden Age brought a Neoclassical look to Copenhagen's architecture. After World War II, the Finger Plan fostered the development of housing and businesses along the five urban railway routes emanating from the city centre.

Since the turn of the 21st century, Copenhagen has seen strong urban and cultural development, facilitated by investment in its institutions and infrastructure. The city is the cultural, economic, and governmental centre of Denmark; it is one of the major financial centres of Northern Europe with the Copenhagen Stock Exchange. Copenhagen's economy has developed rapidly in the service sector, especially through initiatives in information technology, pharmaceuticals, and clean technology. Since the completion of the Øresund Bridge, Copenhagen has increasingly integrated with the Swedish province of Scania and its largest city, Malmö, forming the Øresund Region. With several bridges connecting the various districts, the cityscape is characterised by parks, promenades, and waterfronts. Copenhagen's landmarks, such as Tivoli Gardens, The Little Mermaid statue, the Amalienborg and Christiansborg palaces, Rosenborg Castle, Frederik's Church, Børsen, and many museums, restaurants, and nightclubs are significant tourist attractions.

Copenhagen is home to the University of Copenhagen, the Technical University of Denmark, Copenhagen Business School, and the IT University of Copenhagen. The University of Copenhagen, founded in 1479, is the oldest university in Denmark. Copenhagen is home to the football clubs F.C. Copenhagen and Brøndby IF. The annual Copenhagen Marathon was established in 1980. Copenhagen is one of the most bicycle-friendly cities in the world. Movia is a public mass transit company serving all of eastern Denmark except Bornholm. The Copenhagen Metro, launched in 2002, serves central Copenhagen. Additionally, the Copenhagen S-train, the Lokaltog (private railway), and the Coast Line network serve and connect central Copenhagen to outlying boroughs. Serving roughly 2.5 million passengers a month, Copenhagen Airport, Kastrup, is the busiest airport in the Nordic countries.

Etymology

[edit]Copenhagen's name (København in Danish), reflects its origin as a harbour and a place of commerce. The original designation in Old Norse, from which Danish descends, was Kaupmannahǫfn [ˈkɔupˌmɑnːɑˌhɔvn] (cf. modern Icelandic: Kaupmannahöfn [ˈkʰœipˌmanːaˌhœpn̥], Faroese: Keypmannahavn [ˈtʃʰɛʰpmanːaˌhavn]), meaning 'merchants' harbour' (merchant in plural). By the time Old Danish was spoken, the capital was called Køpmannæhafn, with the current name deriving from centuries of subsequent regular sound change. The stemm-syllable has an au - o change as we see in Asbjörn - Osborn, Austrie etc, and this change in pronunciation happened sometime around 1400.

The English cognates of the original name would be "chapman's haven".[10] The English chapman, German Kaufmann, Dutch koopman, Swedish köpman, Danish købmand, and Icelandic kaupmaður share a derivation from Latin caupo, meaning 'tradesman'. However, the English term for the city was adapted from its Low German name, Kopenhagen. Copenhagen's Swedish name is Köpenhamn, a direct translation of the mutually intelligible Danish name.

The city's Latin name, Hafnia, is the namesake of the element hafnium.[11]

History

[edit]

Early history

[edit]Substantial discoveries of flint tools in the area provide evidence of human settlements dating to the Stone Age.[12] Many historians believe the town dates to the late Viking Age, and was possibly founded by Sweyn I Forkbeard.[13]

Multiple finds indicate that Copenhagen's origins as a city go back at least to the 11th century. The natural harbour and good herring stocks seem to have attracted fishermen and merchants to the area on a seasonal basis from the 11th century and more permanently in the 13th century.[14] The first habitations were probably centred on Gammel Strand (literally 'old shore') in the 11th century or even earlier.[15] Recent archaeological finds in connection with work on the city's metropolitan rail system, revealed the remains of a large merchant's mansion near today's Kongens Nytorv from c. 1020. The remains of an ancient church, with graves dating to the 11th century, have been unearthed near where Strøget meets Rådhuspladsen. Excavations in Pilestræde have also led to the discovery of a well from the late 12th century.

However, the earliest written mention of the town was in the 12th century when Saxo Grammaticus in Gesta Danorum referred to it as Portus Mercatorum, meaning 'Merchants' Harbour' or, in the Danish of the time, Købmannahavn.[16] Traditionally, Copenhagen's founding has been dated to Bishop Absalon's construction of a modest fortress on the little island of Slotsholmen in 1167 where Christiansborg Palace stands today.[17] The construction of the fortress was in response to attacks by Wendish pirates who plagued the coastline during the 12th century.[18] Defensive ramparts and moats were completed, and by 1177 St. Clemens Church had been built. Attacks by the Wends continued, and after the original fortress was eventually destroyed by the marauders, islanders replaced it with Copenhagen Castle.[19]

Middle Ages

[edit]In 1186, a letter from Pope Urban III states that the castle of Hafn (Copenhagen) and its surrounding lands, including the town of Hafn, were given to Absalon, Bishop of Roskilde (1158–1191) and Archbishop of Lund (1177–1201), by King Valdemar I. Upon Absalon's death, the property was to come into the ownership of the Bishopric of Roskilde.[14] Around 1200, the Church of Our Lady was constructed on higher ground to the northeast of the town, which began to develop around it.[14]

As the town became more prominent, it was repeatedly attacked by the Hanseatic League. In 1368, it was successfully invaded during the Second Danish-Hanseatic War. As the fishing industry thrived in Copenhagen, particularly in the trade of herring, the city began expanding to the north of Slotsholmen.[18] In 1254, it received a charter as a city under Bishop Jakob Erlandsen[20] who garnered support from the local fishing merchants against the king by granting them special privileges.[21] In the mid 1330s, the first land assessment of the city was published.[21]

With the establishment of the Kalmar Union (1397–1523) between Denmark, Norway and Sweden, by about 1416 Copenhagen had emerged as the capital of Denmark when Eric of Pomerania moved his seat to Copenhagen Castle.[22][19] The University of Copenhagen was inaugurated on 1 June 1479 by King Christian I, following approval from Pope Sixtus IV.[23] This makes it the oldest university in Denmark and one of the oldest in Europe. Originally controlled by the Catholic Church, the university's role in society was forced to change during the Reformation in Denmark in the late 1530s.[23]

16th and 17th centuries

[edit]In disputes prior to the Reformation of 1536, the city which had been faithful to Christian II, who was Catholic, was successfully besieged in 1523 by the forces of Frederik I, who supported Lutheranism. Copenhagen's defences were reinforced with a series of towers along the city wall. After an extended siege from July 1535 to July 1536, during which the city supported Christian II's alliance with Malmö and Lübeck, it was finally forced to capitulate to Christian III. During the second half of the century, the city prospered from increased trade across the Baltic supported by Dutch shipping. Christoffer Valkendorff, a high-ranking statesman, defended the city's interests and contributed to its development.[14] The Netherlands had also become primarily Protestant, as were northern German states.

During the reign of Christian IV between 1588 and 1648, Copenhagen had dramatic growth as a city. On his initiative at the beginning of the 17th century, two important buildings were completed on Slotsholmen: the Tøjhus Arsenal and Børsen, the stock exchange. To foster international trade, the East India Company was founded in 1616. To the east of the city, inspired by Dutch planning, the king developed the district of Christianshavn with canals and ramparts. It was initially intended to be a fortified trading centre but ultimately became part of Copenhagen.[24] Christian IV also sponsored an array of ambitious building projects including Rosenborg Slot and the Rundetårn.[18] In 1658–1659, the city withstood a siege by the Swedes under Charles X and successfully repelled a major assault.[24]

By 1661, Copenhagen had asserted its position as capital of Denmark and Norway. All the major institutions were located there, as was the fleet and most of the army. The defences were further enhanced with the completion of the Citadel in 1664 and the extension of Christianshavns Vold with its bastions in 1692, leading to the creation of a new base for the fleet at Nyholm.[24][25]

18th century

[edit]

Copenhagen lost around 22,000 of its population of 65,000 to the plague in 1711.[26] The city was also struck by two major fires that destroyed much of its infrastructure.[19] The Copenhagen Fire of 1728 was the largest in the history of Copenhagen. It began on the evening of 20 October, and continued to burn until the morning of 23 October, destroying approximately 28% of the city, leaving some 20% of the population homeless. No less than 47% of the medieval section of the city was completely lost. Along with the 1795 fire, it is the main reason that few traces of the old town can be found in the modern city.[27][28]

A substantial amount of rebuilding followed. In 1733, work began on the royal residence of Christiansborg Palace, which was completed in 1745. In 1749, development of the prestigious district of Frederiksstaden was initiated. Designed by Nicolai Eigtved in the Rococo style, its centre contained the mansions which now form Amalienborg Palace.[29] Major extensions to the naval base of Holmen were undertaken while the city's cultural importance was enhanced with the Royal Theatre and the Royal Academy of Fine Arts.[30]

During the 18th century, the Danish slave trade, which began during the 17th century, underwent a rapid expansion. Between 1660 and 1806, Danish merchants, many of them based out of Copenhagen, transported approximately 120,000 enslaved Africans to the Danish West Indies. These merchants were mostly affiliated with the slave-trading Danish West India Company and Danish Asiatic Company, both of which were headquartered in Copenhagen. Many buildings in Copenhagen, such as the Moltke Mansion, Yellow Palace and the Vestindisk Pakhus were funded with profits made from the Danish slave trade.[31][32] In the second half of the 18th century, Copenhagen benefited from Denmark's neutrality during the wars between Europe's main powers, allowing it to play an important role in trade between the states around the Baltic Sea. After Christiansborg was destroyed by fire in 1794 and another fire caused serious damage to the city in 1795, work began on the classical Copenhagen landmark of Højbro Plads while Nytorv and Gammel Torv were converged.[30]

19th century

[edit]As a result of British fears that Denmark would ally with France, a Royal Navy fleet under the command of Admiral Sir Hyde Parker was dispatched to neutralize the Royal Dano-Norwegian Navy. On 2 April 1801, Parker's fleet encountered the Dano-Norwegian navy anchored near Copenhagen. Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson led the main attack.[33] The Dano-Norwegian fleet put up heavy resistance, and the battle is often considered to be Nelson's hardest-fought battle, surpassing even the heavy fighting at Trafalgar.[34] It was during this battle that Lord Nelson was said to have "put the telescope to the blind eye" in order not to see Admiral Parker's signal to cease fire. The British ultimately won the battle, sinking or capturing most of Dano-Norwegian fleet, which led Denmark to agree not to ally with France.[35]

In 1807, as a result of continued British fears that Denmark would ally with France, another British fleet led by Admiral James Gambier was dispatched to Copenhagen with orders to seize or destroy the Dano-Norwegian navy. The British published a proclamation demanding the surrender of the Dano-Norwegian fleet, and the Danish responded with "what amounted to a declaration of war".[36] Gambier's forces responded by carrying out a naval bombardment of Copenhagen from 2 to 5 September. The bombardment, which saw the deployment of Congreve rockets, killed 195 civilians and wounded 768, along with burning approximately 1,000 structures, including the Church of Our Lady. Copenhagen's defenders were unable to respond to the bombardment effectively due to relying on an old defence-line whose limited range could not reach the British ships and their longer-range artillery. A British landing force of 30,000 men entered and occupied Copenhagen; during the battle, the British suffered almost 200 casualties, while the Danish suffered 3,000. Virtually the entire Dano-Norwegian fleet was surrendered to the British, who either burnt them or brought them back to Britain. Denmark declared war on Britain, leading to the outbreak of the Gunboat War, which lasted until the 1814 Treaty of Kiel.[37][38][39]

Despite the turmoil the Napoleonic Wars brought to the city, Copenhagen soon experienced a period of intense cultural creativity known as the Danish Golden Age. Painting prospered under C.W. Eckersberg and his students while C.F. Hansen and Gottlieb Bindesbøll brought a Neoclassical look to the city's architecture.[40] In the early 1850s, the ramparts of the city were opened to allow new housing to be built around The Lakes (Danish: Søerne) that bordered the old defences to the west. By the 1880s, the districts of Nørrebro and Vesterbro developed to accommodate those who came from the provinces to participate in the city's industrialization. This dramatic increase of space was long overdue, as not only were the old ramparts out of date as a defence system but bad sanitation in the old city had to be overcome. From 1886, the west rampart (Vestvolden) was flattened, allowing major extensions to the harbour leading to the establishment of the Freeport of Copenhagen 1892–94.[41] Electricity came in 1892 with electric trams in 1897. The spread of housing to areas outside the old ramparts brought about a huge increase in the population. In 1840, Copenhagen was inhabited by approximately 120,000 people. By 1901, it had some 400,000 inhabitants.[30]

20th century

[edit]

By the beginning of the 20th century, Copenhagen had become a thriving industrial and administrative city. With its new city hall and railway station, its centre was drawn towards the west.[30] New housing developments grew up in Brønshøj and Valby while Frederiksberg became an enclave within the city of Copenhagen.[42] The northern part of Amager and Valby were also incorporated into the City of Copenhagen in 1901–02.[43]

As a result of Denmark's neutrality in the First World War, Copenhagen prospered from trade with both Britain and Germany while the city's defences were kept fully manned by some 40,000 soldiers for the duration of the war.[44]

In the 1920s there were serious shortages of goods and housing. Plans were drawn up to demolish the old part of Christianshavn and to get rid of the worst of the city's slum areas.[45] However, it was not until the 1930s that substantial housing developments ensued,[46] with the demolition of one side of Christianhavn's Torvegade to build five large blocks of flats.[45]

World War II

[edit]

In Denmark during World War II, Copenhagen was occupied by German troops along with the rest of the country from 9 April 1940 until 4 May 1945. German leader Adolf Hitler hoped that Denmark would be "a model protectorate"[47] and initially the Nazi authorities sought to arrive at an understanding with the Danish government. The 1943 Danish parliamentary election was also allowed to take place, with only the Communist Party excluded. But in August 1943, after the government's collaboration with the occupation forces collapsed, several ships were sunk in Copenhagen Harbor by the Royal Danish Navy to prevent their use by the Germans. Around that time the Nazis started to arrest Jews, although most managed to escape to Sweden.[48]

In 1945 Ole Lippman, leader of the Danish section of the Special Operations Executive, invited the British Royal Air Force to assist their operations by attacking Nazi headquarters in Copenhagen. Accordingly, air vice-marshal Sir Basil Embry drew up plans for a spectacular precision attack on the Sicherheitsdienst and Gestapo building, the former offices of the Shell Oil Company. Political prisoners were kept in the attic to prevent an air raid, so the RAF had to bomb the lower levels of the building.[49]

The attack, known as "Operation Carthage", came on 22 March 1945, in three small waves. In the first wave, all six planes (carrying one bomb each) hit their target, but one of the aircraft crashed near Frederiksberg Girls School. Because of this crash, four of the planes in the two following waves assumed the school was the military target and aimed their bombs at the school, leading to the death of 123 civilians (of which 87 were schoolchildren).[49] However, 18 of the 26 political prisoners in the Shell Building managed to escape while the Gestapo archives were completely destroyed.[49]

On 8 May 1945 Copenhagen was officially liberated by British troops commanded by Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery who supervised the surrender of 30,000 Germans situated around the capital.[50]

Post-war decades

[edit]Shortly after the end of the war, an innovative urban development project known as the Finger Plan was introduced in 1947, encouraging the creation of new housing and businesses interspersed with large green areas along five "fingers" stretching out from the city centre along the S-train routes.[51][52] With the expansion of the welfare state and women entering the work force, schools, nurseries, sports facilities and hospitals were established across the city. As a result of student unrest in the late 1960s, the former Bådsmandsstræde Barracks in Christianshavn was occupied, leading to the establishment of Freetown Christiania in September 1971.[53]

Motor traffic in the city grew significantly and in 1972 the trams were replaced by buses. From the 1960s, on the initiative of the young architect Jan Gehl, pedestrian streets and cycle tracks were created in the city centre.[54] Activity in the port of Copenhagen declined with the closure of the Holmen Naval Base. Copenhagen Airport underwent considerable expansion, becoming a hub for the Nordic countries. In the 1990s, large-scale housing developments were realised in the harbour area and in the west of Amager.[46] The national library's Black Diamond building on the waterfront was completed in 1999.[55]

Gallery

[edit]-

The Black Diamond

-

Freetown Christiania – entrance

21st century

[edit]

Since the summer of 2000, Copenhagen and the Swedish city of Malmö have been connected by the Øresund Bridge, which carries rail and road traffic. As a result, Copenhagen has become the centre of a larger metropolitan area spanning both nations. The bridge has brought about considerable changes in the public transport system and has led to the extensive redevelopment of Amager.[53] The city's service and trade sectors have developed while a number of banking and financial institutions have been established. Educational institutions have also gained importance, especially the University of Copenhagen with its 35,000 students.[56]

An important development for the city has been the opening of the Copenhagen Metro railway system in 2002. The Copenhagen Metro was extended until 2007, transporting some 54 million passengers by 2011.[57] The Copenhagen Opera House, a gift to the city from the shipping magnate Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller on behalf of the A.P. Møller foundation, was completed in 2004.[58]

In December 2009 Copenhagen gained international prominence when it hosted the worldwide climate meeting COP15.[59] In 2019 Copenhagen was crowned the best swimming city by CNN and Copenhagen harbour now has 13 official swimming zones and three harbour baths. Illegal bathers are fined by the police.[60]

On 3 July 2022, three people were killed in a shooting at Field's mall in Copenhagen. Police chief inspector Søren Thomassen announced the arrest of a 22-year-old man and said that the police cannot rule out an act of terrorism.[61][62]

Geography

[edit]

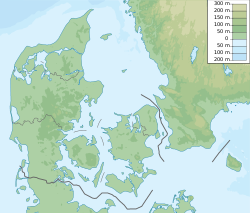

Copenhagen is part of the Øresund Region, which consists of Zealand, Lolland-Falster and Bornholm in Denmark and Scania in Sweden.[63] It is located on the eastern shore of the island of Zealand, partly on the island of Amager and on a number of natural and artificial islets between the two. Copenhagen faces the Øresund to the east, the strait of water that separates Denmark from Sweden, and which connects the North Sea with the Baltic Sea. The Swedish city of Malmö and the town of Landskrona lie on the Swedish side of the sound directly across from Copenhagen.[64] By road, Copenhagen is 42 kilometres (26 mi) northwest of Malmö, Sweden, 85 kilometres (53 mi) northeast of Næstved, 164 kilometres (102 mi) northeast of Odense, 295 kilometres (183 mi) east of Esbjerg and 188 kilometres (117 mi) southeast of Aarhus by sea and road via Sjællands Odde.[65]

The city centre lies in the area originally defined by the old ramparts, which are still referred to as the Fortification Ring (Fæstningsringen) and kept as a partial green band around it.[66] Then come the late-19th- and early-20th-century residential neighbourhoods of Østerbro, Nørrebro, Vesterbro and Amagerbro. The outlying areas of Kongens Enghave, Valby, Vigerslev, Vanløse, Brønshøj, Utterslev and Sundby followed from 1920 to 1960. They consist mainly of residential housing and apartments often enhanced with parks and greenery.[67]

Topography

[edit]The central area of the city consists of relatively low-lying flat ground formed by moraines from the last ice age while the hilly areas to the north and west frequently rise to 50 m (160 ft) above sea level. The slopes of Valby and Brønshøj reach heights of over 30 m (98 ft), divided by valleys running from the northeast to the southwest. Close to the centre are the Copenhagen lakes of Sortedams Sø, Peblinge Sø and Sankt Jørgens Sø.[67]

Copenhagen rests on a subsoil of flint-layered limestone deposited in the Danian period some 60 to 66 million years ago. Some greensand from the Selandian is also present. There are a few faults in the area, the most important of which is the Carlsberg fault which runs northwest to southeast through the centre of the city.[68] During the last ice age, glaciers eroded the surface leaving a layer of moraines up to 15 m (49 ft) thick.[69]

Geologically, Copenhagen lies in the northern part of Denmark where the land is rising because of post-glacial rebound.

Beaches

[edit]

Amager Strandpark, which opened in 2005, is a 2 km (1 mi) long artificial island, with a total of 4.6 km (2.9 mi) of beaches. It is located just 15 minutes by bicycle or a few minutes by metro from the city centre.[70] In Klampenborg, about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) from downtown Copenhagen, is Bellevue Beach. It is 700 metres (2,300 ft) long and has both lifeguards and freshwater showers on the beach.[71]

The beaches are supplemented by a system of Harbour Baths along the Copenhagen waterfront. The first and most popular of these is located at Islands Brygge, literally meaning Iceland's Quay, and has won international acclaim for its design.[72]

Climate

[edit]

Copenhagen is in the oceanic climate zone (Köppen: Cfb).[73] Its weather is subject to low-pressure systems from the Atlantic which result in unstable conditions throughout the year. Apart from slightly higher rainfall from July to September, precipitation is moderate. While snowfall occurs mainly from late December to early March, there can also be rain, with average temperatures around the freezing point.[74]

July is the sunniest month of the year with an average of over seven hours of sunshine a day. July is the warmest month with an average daytime high of 21 °C. By contrast, the average hours of sunshine are less than two per day in November and only one and a half per day from December to February. In the spring, it gets warmer again with four to six hours of sunshine per day from March to May. February is the driest month of the year.[75] Exceptional weather conditions can bring as much as 50 cm of snow to Copenhagen in a 24-hour period during the winter months[76] while summer temperatures have been known to rise to heights of 33 °C (91 °F).[77]

Because of Copenhagen's northern latitude, the number of daylight hours varies considerably between summer and winter. On the summer solstice, the sun rises at 04:26 and sets at 21:58, providing 17 hours 32 minutes of daylight. On the winter solstice, it rises at 08:37 and sets at 15:39 with 7 hours and 1 minute of daylight. There is therefore a difference of 10 hours and 31 minutes in the length of days and nights between the summer and winter solstices.[78]

| Climate data for Copenhagen, Denmark (1981–2010 normals, extremes 1768–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 11.2 (52.2) |

15.8 (60.4) |

20.8 (69.4) |

28.0 (82.4) |

32.4 (90.3) |

34.8 (94.6) |

35.6 (96.1) |

34.8 (94.6) |

32.4 (90.3) |

24.4 (75.9) |

17.2 (63.0) |

12.1 (53.8) |

35.6 (96.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.4 (38.1) |

3.6 (38.5) |

6.5 (43.7) |

11.8 (53.2) |

16.7 (62.1) |

19.6 (67.3) |

22.2 (72.0) |

21.8 (71.2) |

17.5 (63.5) |

12.6 (54.7) |

7.6 (45.7) |

4.4 (39.9) |

12.3 (54.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.4 (34.5) |

1.4 (34.5) |

3.5 (38.3) |

7.7 (45.9) |

12.5 (54.5) |

15.6 (60.1) |

18.1 (64.6) |

17.7 (63.9) |

13.9 (57.0) |

9.8 (49.6) |

5.5 (41.9) |

2.5 (36.5) |

9.1 (48.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −0.7 (30.7) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

0.7 (33.3) |

4.2 (39.6) |

8.6 (47.5) |

11.9 (53.4) |

14.3 (57.7) |

14.1 (57.4) |

10.8 (51.4) |

7.1 (44.8) |

3.3 (37.9) |

0.5 (32.9) |

6.2 (43.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −27.6 (−17.7) |

−25.5 (−13.9) |

−21.0 (−5.8) |

−16.5 (2.3) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

0.4 (32.7) |

0.1 (32.2) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−8.8 (16.2) |

−18.4 (−1.1) |

−22.9 (−9.2) |

−27.6 (−17.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 53.0 (2.09) |

36.9 (1.45) |

42.3 (1.67) |

35.8 (1.41) |

47.2 (1.86) |

63.9 (2.52) |

60.9 (2.40) |

67.5 (2.66) |

61.0 (2.40) |

63.3 (2.49) |

56.4 (2.22) |

57.4 (2.26) |

645.6 (25.43) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 14.9 | 11.4 | 13.5 | 11.5 | 10.8 | 12.0 | 12.4 | 12.0 | 13.6 | 14.5 | 15.4 | 15.4 | 157.4 |

| Average snowy days | 5.9 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.7 | 3.9 | 21.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 86 | 84 | 82 | 76 | 72 | 72 | 73 | 75 | 78 | 83 | 84 | 85 | 79 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 51.5 | 68.1 | 119.7 | 180.9 | 230.2 | 213.3 | 228.1 | 198.9 | 141.9 | 100.9 | 55.3 | 40.6 | 1,629.4 |

| Percentage possible sunshine | 21 | 25 | 33 | 43 | 46 | 41 | 44 | 43 | 37 | 31 | 22 | 18 | 34 |

| Source: DMI (precipitation days and snowy days 1971–2000, humidity 1961–1990),[79][80][81] Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[82] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Copenhagen (Copenhagen Airport) (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1971–2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 10.4 (50.7) |

12.8 (55.0) |

15.9 (60.6) |

25.7 (78.3) |

26.4 (79.5) |

30.2 (86.4) |

31.2 (88.2) |

31.1 (88.0) |

26.2 (79.2) |

20.7 (69.3) |

14.7 (58.5) |

12.4 (54.3) |

31.2 (88.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.3 (37.9) |

3.4 (38.1) |

6.3 (43.3) |

11.3 (52.3) |

15.8 (60.4) |

19.2 (66.6) |

21.7 (71.1) |

21.4 (70.5) |

17.4 (63.3) |

12.2 (54.0) |

7.6 (45.7) |

4.6 (40.3) |

12.0 (53.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.3 (34.3) |

1.3 (34.3) |

3.3 (37.9) |

7.7 (45.9) |

11.9 (53.4) |

15.4 (59.7) |

17.9 (64.2) |

17.7 (63.9) |

14.2 (57.6) |

9.7 (49.5) |

5.6 (42.1) |

2.7 (36.9) |

9.1 (48.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −0.7 (30.7) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

0.4 (32.7) |

4.0 (39.2) |

7.9 (46.2) |

11.7 (53.1) |

14.0 (57.2) |

14.0 (57.2) |

11.0 (51.8) |

7.2 (45.0) |

3.7 (38.7) |

0.8 (33.4) |

6.1 (43.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −17.8 (0.0) |

−16.2 (2.8) |

−13.9 (7.0) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

3.4 (38.1) |

6.0 (42.8) |

5.2 (41.4) |

0.9 (33.6) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

−9.5 (14.9) |

−15.9 (3.4) |

−17.8 (0.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 37.3 (1.47) |

22.7 (0.89) |

35.0 (1.38) |

32.5 (1.28) |

40.5 (1.59) |

50.0 (1.97) |

51.4 (2.02) |

50.1 (1.97) |

58.9 (2.32) |

50.2 (1.98) |

48.0 (1.89) |

46.0 (1.81) |

522.6 (20.57) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 9.0 | 6.4 | 8.2 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 8.8 | 8.5 | 8.0 | 9.6 | 9.4 | 9.8 | 9.9 | 101.6 |

| Average snowy days | 5.9 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 1.7 | 3.9 | 21.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 86 | 84 | 82 | 76 | 72 | 72 | 73 | 75 | 78 | 83 | 84 | 85 | 79 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 46 | 65 | 117 | 188 | 262 | 247 | 260 | 241 | 154 | 103 | 58 | 38 | 1,779 |

| Source 1: Danish Meteorological Institute (precipitation, sun and snow 1971–2000, humidity 1961–1990)[84][85] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: IEM[86] | |||||||||||||

Administration

[edit]

According to Statistics Denmark, the urban area of Copenhagen (Hovedstadsområdet) consists of the municipalities of Copenhagen, Frederiksberg, Albertslund, Brøndby, Gentofte, Gladsaxe, Glostrup, Herlev, Hvidovre, Lyngby-Taarbæk, Rødovre, Tårnby and Vallensbæk as well as parts of Ballerup, Rudersdal and Furesø municipalities, along with the cities of Ishøj and Greve Strand.[4][87] They are located in the Capital Region (Region Hovedstaden). Municipalities are responsible for a wide variety of public services, which include land-use planning, environmental planning, public housing, management and maintenance of local roads, and social security. Municipal administration is also conducted by a mayor, a council, and an executive.[88]

Copenhagen Municipality is by far the largest municipality, with the historic city at its core. The seat of Copenhagen's municipal council is the Copenhagen City Hall (Rådhus), which is situated on City Hall Square. The second largest municipality is Frederiksberg, an enclave within Copenhagen Municipality.

Copenhagen Municipality is divided into ten districts (bydele):[89] Indre By, Østerbro, Nørrebro, Vesterbro/Kongens Enghave, Valby, Vanløse, Brønshøj-Husum, Bispebjerg, Amager Øst, and Amager Vest. Neighbourhoods of Copenhagen include Slotsholmen, Frederiksstaden, Islands Brygge, Holmen, Christiania, Carlsberg, Sluseholmen, Sydhavn, Amagerbro, Ørestad, Nordhavnen, Bellahøj, Brønshøj, Ryparken, and Vigerslev.

Law and order

[edit]Most of Denmark's top legal courts and institutions are based in Copenhagen. A modern-style court of justice, Hof- og Stadsretten, was introduced in Denmark, specifically for Copenhagen, by Johann Friedrich Struensee in 1771.[90] Now known as the City Court of Copenhagen (Københavns Byret), it is the largest of the 24 city courts in Denmark with jurisdiction over the municipalities of Copenhagen, Dragør and Tårnby. With its 42 judges, it has a Probate Division, an Enforcement Division and a Registration and Notorial Acts Division while bankruptcy is handled by the Maritime and Commercial Court of Copenhagen.[91] Established in 1862, the Maritime and Commercial Court (Sø- og Handelsretten) also hears commercial cases including those relating to trade marks, marketing practices and competition for the whole of Denmark.[92] Denmark's Supreme Court (Højesteret), located in Christiansborg Palace on Prins Jørgens Gård in the centre of Copenhagen, is the country's final court of appeal. Handling civil and criminal cases from the subordinate courts, it has two chambers which each hear all types of cases.[93]

The Danish National Police and Copenhagen Police headquarters is situated in the Neoclassical-inspired Politigården building built in 1918–1924 under architects Hack Kampmann and Holger Alfred Jacobsen. The building also contains administration, management, emergency department and radio service offices.[94]

The Copenhagen Fire Department forms the largest municipal fire brigade in Denmark with some 500 fire and ambulance personnel, 150 administration and service workers, and 35 workers in prevention.[95] The brigade began as the Copenhagen Royal Fire Brigade on 9 July 1687 under King Christian V. After the passing of the Copenhagen Fire Act on 18 May 1868, on 1 August 1870 the Copenhagen Fire Brigade became a municipal institution in its own right.[96] The fire department has its headquarters in the Copenhagen Central Fire Station which was designed by Ludvig Fenger in the Historicist style and inaugurated in 1892.[97]

Environmental planning

[edit]

Copenhagen is recognised as one of the most environmentally friendly cities in the world.[98] As a result of its commitment to high environmental standards, Copenhagen has been praised for its green economy, ranked as the top green city for the second time in the 2014 Global Green Economy Index (GGEI).[99][100] In 2001 a large offshore wind farm was built just off the coast of Copenhagen at Middelgrunden. It produces about 4% of the city's energy.[101] Years of substantial investment in sewage treatment have improved water quality in the harbour to an extent that the Inner Harbour can be used for swimming with facilities at a number of locations.[102]

Copenhagen aims to be carbon-neutral by 2025. Commercial and residential buildings are to reduce electricity consumption by 20 per cent and 10 per cent respectively, and total heat consumption is to fall by 20 per cent by 2025. Renewable energy features such as solar panels are becoming increasingly common in the newest buildings in Copenhagen. District heating will be carbon-neutral by 2025, by waste incineration and biomass. New buildings must now be constructed according to Low Energy Class ratings and in 2020 near net-zero energy buildings. By 2025, 75% of trips should be made on foot, by bike, or by using public transit. The city plans that 20–30% of cars will run on electricity or biofuel by 2025. The investment is estimated at $472 million public funds and $4.78 billion private funds.[103]

The city's urban planning authorities continue to take full account of these priorities. Special attention is given both to climate issues and efforts to ensure maximum application of low-energy standards. Priorities include sustainable drainage systems,[104] recycling rainwater, green roofs and efficient waste management solutions. In city planning, streets and squares are to be designed to encourage cycling and walking rather than driving.[105]

Demographics

[edit]

- Danish (73.7%)

- Other European (12.9%)

- Asian (8.20%)

- African (3.00%)

- Others (2.20%)

| Nationality | Population |

|---|---|

| 5,333 |

| Nationality | Population | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8,139 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7,614 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7,378 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6,793 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6,689 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5,739 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5,622 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5,576 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5,491 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5,247 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4,936 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4,844 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4,818 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| {{flag icon|Iceland}} Iceland | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4,665 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4,547 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4,513 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4,379 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4,076 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3,967 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3,798 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copenhagen is the most populous city in Denmark and one of the most populous in the Nordic countries. For statistical purposes, Statistics Denmark considers the City of Copenhagen (Byen København) to consist of the Municipality of Copenhagen plus three adjacent municipalities: Dragør, Frederiksberg, and Tårnby.[108] Their combined population stands at 763,908 (as of December 2016[update]).[9]

The Municipality of Copenhagen is by far the most populous in the country and one of the most populous Nordic municipalities with 644,431 inhabitants (as of 2022).[4] There was a demographic boom in the 1990s and first decades of the 21st century, largely due to immigration to Denmark. According to figures from the first quarter of 2022, 73.7% of the municipality's population was of Danish descent,[107] defined as having at least one parent who was born in Denmark and has Danish citizenship. Much of the remaining 26.3% were of a foreign background, defined as immigrants (20.3%) or descendants of recent immigrants (6%).[107] There are no official statistics on ethnic groups. The adjacent table shows the most common countries of origin of Copenhagen residents. Largest foreign groups are Pakistanis (1.3%), Turks (1.2%), Iraqis (1.1%), Germans (1.0%) and Poles (1.0%).

According to Statistics Denmark, Copenhagen's urban area has a larger population of 1,280,371 (as of 1 January 2016[update]).[4] The urban area consists of the municipalities of Copenhagen and Frederiksberg plus 16 of the 20 municipalities of the former counties Copenhagen and Roskilde, though five of them only partially.[87] Metropolitan Copenhagen has a total of 2,016,285 inhabitants (as of 2016[update]).[4] The area of Metropolitan Copenhagen is defined by the Finger Plan.[109] Since the opening of the Øresund Bridge in 2000, commuting between Zealand and Scania in Sweden has increased rapidly, leading to a wider, integrated area. Known as the Øresund Region, it has 4.1 million inhabitants—of whom 2.7 million (August 2021) live in the Danish part of the region.[110] In Copenhagen, more than 50% of the households consist of only one adult.[111]

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: [112] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Religion

[edit]

A majority (56.9%) of those living in Copenhagen are members of the Lutheran Church of Denmark which is 0.6% lower than one year earlier according to 2019 figures.[113] The National Cathedral, the Church of Our Lady, is one of the dozens of churches in Copenhagen. There are also several other Christian communities in the city, of which the largest is Roman Catholic.[114]

Foreign migration to Copenhagen, rising over the last three decades, has contributed to increasing religious diversity; the Grand Mosque of Copenhagen, the first in Denmark, opened in 2014.[115] Islam is the second largest religion in Copenhagen, accounting for approximately 10% of the population.[116][117][118] While there are no official statistics, a significant portion of the estimated 175,000–200,000 Muslims in the country live in the Copenhagen urban area, with the highest concentration in Nørrebro and the Vestegnen.[119] There are also some 7,000 Jews in Denmark, most of them in the Copenhagen area where there are several synagogues.[120] It has a membership of 1,800 members.[121] There is a long history of Jews in the city, and the first synagogue in Copenhagen was built in 1684.[122] Today, the history of the Jews of Denmark can be explored at the Danish Jewish Museum in Copenhagen.

Quality of living

[edit]For a number of years, Copenhagen has ranked high in international surveys for its quality of life. Its stable economy together with its education services and level of social safety make it attractive for locals and visitors alike. Although it is one of the world's most expensive cities, it is also one of the most liveable with its public transport, facilities for cyclists and its environmental policies.[123] In elevating Copenhagen to "most liveable city" in 2013, Monocle pointed to its open spaces, increasing activity on the streets, city planning in favour of cyclists and pedestrians, and features to encourage inhabitants to enjoy city life with an emphasis on community, culture and cuisine.[124] The city is voted 2024 second most liveable city by Economist Intelligence Unit.[125] Other sources have ranked Copenhagen high for its business environment, accessibility, restaurants and environmental planning.[126] However, Copenhagen ranks only 39th for student friendliness in 2012. Despite a top score for quality of living, its scores were low for employer activity and affordability.[127]

Economy

[edit]Copenhagen is the major economic and financial centre of Denmark. The city's economy is based largely on services and commerce. Statistics for 2010 show that the vast majority of the 350,000 workers in Copenhagen are employed in the service sector, especially transport and communications, trade, and finance, while less than 10,000 work in the manufacturing industries. The public sector workforce is around 110,000, including education and healthcare.[128] From 2006 to 2011, the economy grew by 2.5% in Copenhagen, while it fell by some 4% in the rest of Denmark.[129] In 2017, the wider Capital Region of Denmark had a gross domestic product (GDP) of €120 billion, and the 15th largest GDP per capita of regions in the European Union.[130] As of Copenhagen Green Economy Leader Report made by London School of Economics and Political Science – Copenhagen is widely recognised as a leader in the global green economy. The Copenhagen region accounts for almost 40% of Denmark's output and has enjoyed long-term stable growth. At a national level, Danish GDP per capita is ranked among the top 10 countries in the world. At the same time, the city's growth has been delivered while improving environmental performance and transitioning to a low-carbon economy.

Several financial institutions and banks have headquarters in Copenhagen, including Alm. Brand, Danske Bank, Nykredit and Nordea Bank Danmark. The Copenhagen Stock Exchange (CSE) was founded in 1620 and is now owned by Nasdaq, Inc. Copenhagen is also home to a number of international companies including A.P. Møller-Mærsk, Novo Nordisk, Carlsberg and Novozymes.[131] City authorities have encouraged the development of business clusters in several innovative sectors, which include information technology, biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, clean technology and smart city solutions.[132][133]

Life science is a key sector with extensive research and development activities. Medicon Valley is a leading bi-national life sciences cluster in Europe, spanning the Øresund Region. Copenhagen is rich in companies and institutions with a focus on research and development within the field of biotechnology,[134] and the Medicon Valley initiative aims to strengthen this position and to promote cooperation between companies and academia. Many major Danish companies like Novo Nordisk and Lundbeck, both of which are among the 50 largest pharmaceutical and biotech companies in the world, are located in this business cluster.[135]

Shipping is another important sector with Maersk, the world's largest shipping company, having their world headquarters in Copenhagen. The city has an industrial harbour, Copenhagen Port. Following decades of stagnation, it has experienced a resurgence since 1990 following a merger with Malmö harbour. Both ports are operated by Copenhagen Malmö Port (CMP). The central location in the Øresund Region allows the ports to act as a hub for freight that is transported onward to the Baltic countries. CMP annually receives about 8,000 ships and handled some 148,000 TEU in 2012.[136]

Copenhagen has some of the highest gross wages in the world.[137] High taxes mean that wages are reduced after mandatory deduction. A beneficial researcher scheme with low taxation of foreign specialists has made Denmark an attractive location for foreign labour. It is, however, also among the most expensive cities in Europe.[138][139]

Denmark's Flexicurity model features some of the most flexible hiring and firing legislation in Europe, providing attractive conditions for foreign investment and international companies looking to locate in Copenhagen.[140] In Dansk Industri's 2013 survey of employment factors in the ninety-six municipalities of Denmark, Copenhagen came in first place for educational qualifications and for the development of private companies in recent years, but fell to 86th place in local companies' assessment of the employment climate. The survey revealed considerable dissatisfaction in the level of dialogue companies enjoyed with the municipal authorities.[141]

Tourism

[edit]Tourism is a major contributor to Copenhagen's economy, attracting visitors due to the city's harbour, cultural attractions and award-winning restaurants. Since 2009, Copenhagen has been one of the fastest growing metropolitan destinations in Europe.[142] Hotel capacity in the city is growing significantly. From 2009 to 2013, it experienced a 42% growth in international bed nights (total number of nights spent by tourists), tallying a rise of nearly 70% for Chinese visitors.[142] The total number of bed nights in the Capital Region surpassed 9 million in 2013, while international bed nights reached 5 million.[142]

In 2010, it is estimated that city break tourism contributed to DKK 2 billion in turnover. However, 2010 was an exceptional year for city break tourism and turnover increased with 29% in that one year.[143] 680,000 cruise passengers visited the port in 2015.[144] In 2019 Copenhagen was ranked first among Lonely Planet's top ten cities to visit.[145] In October 2021, Copenhagen was shortlisted for the European Commission's 2022 European Capital of Smart Tourism award along with Bordeaux, Dublin, Florence, Ljubljana, Palma de Mallorca and Valencia.[146]

Cityscape

[edit]The city's appearance today is shaped by the key role it has played as a regional centre for centuries. Copenhagen has a multitude of districts, each with its distinctive character and representing its own period. Other distinctive features of Copenhagen include the abundance of water, its many parks, and the bicycle paths that line most streets.[147]

Architecture

[edit]The oldest section of Copenhagen's inner city is often referred to as Middelalderbyen (the medieval city).[148] However, the city's most distinctive district is Frederiksstaden, developed during the reign of Frederick V. It has the Amalienborg Palace at its centre and is dominated by the dome of Frederik's Church (or the Marble Church) and several elegant 18th-century Rococo mansions.[149] The inner city includes Slotsholmen, a little island on which Christiansborg Palace stands and Christianshavn with its canals.[150] Børsen on Slotsholmen and Frederiksborg Palace in Hillerød are prominent examples of the Dutch Renaissance style in Copenhagen. Around the historical city centre lies a band of congenial residential boroughs (Vesterbro, Inner Nørrebro, Inner Østerbro) dating mainly from late 19th century. They were built outside the old ramparts when the city was finally allowed to expand beyond its fortifications.[151]

Sometimes referred to as "the City of Spires", Copenhagen is known for its horizontal skyline, broken only by the spires and towers of its churches and castles. Most characteristic of all is the Baroque spire of the Church of Our Saviour with its narrowing external spiral stairway that visitors can climb to the top.[152] Other important spires are those of Christiansborg Palace, the City Hall and the former Church of St. Nikolaj that now houses a modern art venue. Not quite so high are the Renaissance spires of Rosenborg Castle and the "dragon spire" of Christian IV's former stock exchange, so named because it resembles the intertwined tails of four dragons.[153]

Copenhagen is recognised globally as an exemplar of best practice urban planning.[154] Its thriving mixed use city centre is defined by striking contemporary architecture, engaging public spaces and an abundance of human activity. These design outcomes have been deliberately achieved through careful replanning in the second half of the 20th century.

Recent years have seen a boom in modern architecture in Copenhagen[155] both for Danish architecture and for works by international architects. For a few hundred years, virtually no foreign architects had worked in Copenhagen, but since the turn of the millennium the city and its immediate surroundings have seen buildings and projects designed by top international architects. British design magazine Monocle named Copenhagen the World's best design city 2008.[156]

Copenhagen's urban development in the first half of the 20th century was heavily influenced by industrialisation. After World War II, Copenhagen Municipality adopted Fordism and repurposed its medieval centre to facilitate private automobile infrastructure in response to innovations in transport, trade and communication.[157] Copenhagen's spatial planning in this time frame was characterised by the separation of land uses: an approach which requires residents to travel by car to access facilities of different uses.[158]

The boom in urban development and modern architecture has brought some changes to the city's skyline. A political majority has decided to keep the historical centre free of high-rise buildings, but several areas will see or have already seen massive urban development. Ørestad now has seen most of the recent development. Located near Copenhagen Airport, it currently boasts one of the largest malls in Scandinavia and a variety of office and residential buildings as well as the IT University and a high school.[159]

Parks, gardens and zoo

[edit]

Copenhagen is a green city with many parks, both large and small. King's Garden (Kongens Have), the garden of Rosenborg Castle, is the oldest and most frequented of them all.[160] It was Christian IV who first developed its landscaping in 1606. Every year it sees more than 2.5 million visitors[161] and in the summer months it is packed with sunbathers, picnickers and ballplayers. It serves as a sculpture garden with both a permanent display and temporary exhibits during the summer months.[160] Also located in the city centre are the Botanical Gardens noted for their large complex of 19th-century greenhouses donated by Carlsberg founder J. C. Jacobsen.[162] Fælledparken at 58 ha (140 acres) is the largest park in Copenhagen.[163]

It is popular for sports fixtures and hosts several annual events including a free opera concert at the opening of the opera season, other open-air concerts, carnival and Labour Day celebrations, and the Copenhagen Historic Grand Prix, a race for antique cars. A historical green space in the northeastern part of the city is Kastellet, a well-preserved Renaissance citadel that now serves mainly as a park.[164] Another popular park is the Frederiksberg Gardens, a 32-hectare romantic landscape park. It houses a colony of tame grey herons and other waterfowl.[165] The park offers views of the elephant house of the adjacent Copenhagen Zoo, designed by world-famous British architect Norman Foster.[166] Langelinie, a park and promenade along the inner Øresund coast, is home to one of Copenhagen's most-visited tourist attractions, the Little Mermaid statue.[167]

In Copenhagen, many cemeteries double as parks, though only for the more quiet activities such as sunbathing, reading and meditation. Assistens Cemetery, the burial place of Hans Christian Andersen, is an important green space for the district of Inner Nørrebro and a Copenhagen institution. The lesser known Vestre Kirkegaard is the largest cemetery in Denmark (54 ha (130 acres)) and offers a maze of dense groves, open lawns, winding paths, hedges, overgrown tombs, monuments, tree-lined avenues, lakes and other garden features.[168]

It is official municipal policy in Copenhagen that by 2015 all citizens must be able to reach a park or beach on foot in less than 15 minutes.[169] In line with this policy, several new parks, including the innovative Superkilen in the Nørrebro district, have been completed or are under development in areas lacking green spaces.[170]

Landmarks by district

[edit]Indre By

[edit]The historic centre of the city, Indre By or the Inner City, features many of Copenhagen's most popular monuments and attractions. The area known as Frederiksstaden, developed by Frederik V in the second half of the 18th century in the Rococo style, has the four mansions of Amalienborg, the royal residence, and the wide-domed Marble Church at its centre.[171] Directly across the water from Amalienborg, the 21st-century Copenhagen Opera House stands on the island of Holmen.[172] To the south of Frederiksstaden, the Nyhavn canal is lined with colourful houses from the 17th and 18th centuries, many now with lively restaurants and bars.[173] The canal runs from the harbour front to the spacious square of Kongens Nytorv which was laid out by Christian V in 1670. Important buildings include Charlottenborg Palace, famous for its art exhibitions, the Thott Palace (now the French embassy), the Royal Danish Theatre and the Hotel D'Angleterre, dated to 1755.[174] Other landmarks in Indre By include the parliament building of Christiansborg, the City Hall and Rundetårn, originally an observatory. There are also several museums in the area including Thorvaldsen Museum dedicated to the 18th-century sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen.[175] Closed to traffic since 1964, Strøget, one of the world's oldest and longest pedestrian streets, runs the 3.2 km (2.0 mi) from Rådhuspladsen to Kongens Nytorv. With its speciality shops, cafés, restaurants, and buskers, it is always full of life and includes the old squares of Gammel Torv and Amagertorv, each with a fountain.[176] Rosenborg Castle on Øster Voldgade was built by Christian IV in 1606 as a summer residence in the Renaissance style. It houses the Danish crown jewels and crown regalia, the coronation throne and tapestries illustrating Christian V's victories in the Scanian War.[177]

Christianshavn

[edit]

Christianshavn lies to the southeast of Indre By on the other side of the harbour. The area was developed by Christian IV in the early 17th century. Impressed by the city of Amsterdam, he employed Dutch architects to create canals within its ramparts which are still well preserved today.[24] The canals themselves, branching off the central Christianshavn Canal and lined with house boats and pleasure craft are one of the area's attractions.[178] Another interesting feature is Freetown Christiania, a fairly large area which was initially occupied by squatters during student unrest in 1971. Today it still maintains a measure of autonomy. The inhabitants openly sell drugs on "Pusher Street" as well as their arts and crafts. Other buildings of interest in Christianshavn include the Church of Our Saviour with its spiralling steeple and the magnificent Rococo Christian's Church. Once a warehouse, the North Atlantic House now displays culture from Iceland and Greenland and houses the Noma restaurant, known for its Nordic cuisine.[179][180]

Vesterbro

[edit]

Vesterbro, to the southwest of Indre By, begins with the Tivoli Gardens, the city's top tourist attraction with its fairground atmosphere, its Pantomime Theatre, its Concert Hall and its many rides and restaurants.[181] The Carlsberg neighbourhood has some interesting vestiges of the old brewery of the same name including the Elephant Gate and the Ny Carlsberg Brewhouse.[182] The Tycho Brahe Planetarium is located on the edge of Skt. Jørgens Sø, one of the Copenhagen lakes.[183] Halmtorvet, the old hay market behind the Central Station, is an increasingly popular area with its cafés and restaurants. The former cattle market Øksnehallen has been converted into a modern exhibition centre for art and photography.[184] Radisson Blu Royal Hotel, built by Danish architect and designer Arne Jacobsen for the airline Scandinavian Airlines System (SAS) between 1956 and 1960 was once the tallest hotel in Denmark with a height of 69.60 m (228.3 ft) and the city's only skyscraper until 1969.[185] Completed in 1908, Det Ny Teater (the New Theatre) located in a passage between Vesterbrogade and Gammel Kongevej has become a popular venue for musicals since its reopening in 1994, attracting the largest audiences in the country.[186]

Nørrebro

[edit]

Nørrebro to the northwest of the city centre has recently developed from a working-class district into a colourful cosmopolitan area with antique shops, non-Danish food stores and restaurants. Much of the activity is centred on Sankt Hans Torv[187] and around Rantzausgade. Copenhagen's historic cemetery, Assistens Kirkegård halfway up Nørrebrogade, is the resting place of many famous figures including Søren Kierkegaard, Niels Bohr, and Hans Christian Andersen but is also used by locals as a park and recreation area.[188]

Østerbro

[edit]

Just north of the city centre, Østerbro is an upper middle-class district with a number of fine mansions, some now serving as embassies.[189] The district stretches from Nørrebro to the waterfront where The Little Mermaid statue can be seen from the promenade known as Langelinie. Inspired by Hans Christian Andersen's fairy tale, it was created by Edvard Eriksen and unveiled in 1913.[190] Not far from the Little Mermaid, the old Citadel (Kastellet) can be seen. Built by Christian IV, it is one of northern Europe's best preserved fortifications. There is also a windmill in the area.[191] The large Gefion Fountain (Gefionspringvandet) designed by Anders Bundgaard and completed in 1908 stands close to the southeast corner of Kastellet. Its figures illustrate a Nordic legend.[192]

Frederiksberg

[edit]

Frederiksberg, a separate municipality within the urban area of Copenhagen, lies to the west of Nørrebro and Indre By and north of Vesterbro. Its landmarks include Copenhagen Zoo founded in 1869 with over 250 species from all over the world and Frederiksberg Palace built as a summer residence by Frederick IV who was inspired by Italian architecture. Now a military academy, it overlooks the extensive landscaped Frederiksberg Gardens with its follies, waterfalls, lakes and decorative buildings.[193] The wide tree-lined avenue of Frederiksberg Allé connecting Vesterbrogade with the Frederiksberg Gardens has long been associated with theatres and entertainment. While a number of the earlier theatres are now closed, the Betty Nansen Theatre and Aveny-T are still active.[194]

Amagerbro

[edit]Amagerbro (also known as Sønderbro) is the district located immediately south-east of Christianshavn at northernmost Amager. The old city moats and their surrounding parks constitute a clear border between these districts. The main street is Amagerbrogade which after the harbour bridge Langebro, is an extension of H. C. Andersens Boulevard and has a number of various stores and shops as well as restaurants and pubs.[195] Amagerbro was built up during the two first decades of the twentieth century and is the city's southernmost block built area with typically 4–7 floors. Further south follows the Sundbyøster and Sundbyvester districts.[196]

Other districts

[edit]Not far from Copenhagen Airport on the Kastrup coast, The Blue Planet completed in March 2013 now houses the national aquarium. With its 53 aquariums, it is the largest facility of its kind in Scandinavia.[197] Grundtvig's Church, located in the northern suburb of Bispebjerg, was designed by P.V. Jensen Klint and completed in 1940. A rare example of Expressionist church architecture, its striking west façade is reminiscent of a church organ.[198]

Culture

[edit]

Apart from being the national capital, Copenhagen also serves as the cultural hub of Denmark and one of the major hubs in wider Scandinavia. Since the late 1990s, it has undergone a transformation from a modest Scandinavian capital into a metropolitan city of international appeal, in the same league as cities such as Barcelona and Amsterdam.[199] This is a result of huge investments in infrastructure and culture as well as the work of successful new Danish architects, designers and chefs.[155][200] Copenhagen Fashion Week takes place every year in February and August.[201][202]

Museums

[edit]Copenhagen has a wide array of museums of international standing. The National Museum, Nationalmuseet, is Denmark's largest museum of archaeology and cultural history, comprising the histories of Danish and foreign cultures alike.[203] Denmark's National Gallery (Statens Museum for Kunst) is the national art museum with collections dating from the 12th century to the present. In addition to Danish painters, artists represented in the collections include Rubens, Rembrandt, Picasso, Braque, Léger, Matisse, Emil Nolde, Olafur Eliasson, Elmgreen & Dragset, Superflex, and Jens Haaning.[204]

Another important Copenhagen art museum is the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek founded by second generation Carlsberg philanthropist Carl Jacobsen and built around his personal collections. Its main focus is classical Egyptian, Roman and Greek sculptures and antiquities and a collection of Rodin sculptures, the largest outside France. Besides its sculpture collections, the museum also holds a comprehensive collection of paintings of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters such as Monet, Renoir, Cézanne, van Gogh and Toulouse-Lautrec as well as works by the Danish Golden Age painters.[205]

Louisiana is a Museum of Modern Art situated on the coast just north of Copenhagen. It is located in the middle of a sculpture garden on a cliff overlooking Øresund. Its collection of over 3,000 items includes works by Picasso, Giacometti and Dubuffet.[206] The Danish Design Museum is housed in the 18th-century former Frederiks Hospital and displays Danish design as well as international design and crafts.[207]

Other museums include: the Thorvaldsens Museum, dedicated to the oeuvre of romantic Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen who lived and worked in Rome;[208] the Cisternerne museum, an exhibition space for contemporary art, located in former cisterns that come complete with stalactites formed by the changing water levels;[209] and the Ordrupgaard Museum, located just north of Copenhagen, which features 19th-century French and Danish art and is noted for its works by Paul Gauguin.[210]

Entertainment and performing arts

[edit]

The new Copenhagen Concert Hall opened in January 2009. Designed by Jean Nouvel, it has four halls with the main auditorium seating 1,800 people. It serves as the home of the Danish National Symphony Orchestra and along with the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles is the most expensive concert hall ever built.[211] Another important venue for classical music is the Tivoli Concert Hall located in the Tivoli Gardens.[212] Designed by Henning Larsen, the Copenhagen Opera House (Operaen) opened in 2005. It is among the most modern opera houses in the world.[213] The Royal Danish Theatre also stages opera in addition to its drama productions. It is also home to the Royal Danish Ballet. Founded in 1748 along with the theatre, it is one of the oldest ballet troupes in Europe, and is noted for its Bournonville style of ballet.[214]

Copenhagen has a significant jazz scene that has existed for many years. It developed when a number of American jazz musicians such as Ben Webster, Thad Jones, Richard Boone, Ernie Wilkins, Kenny Drew, Ed Thigpen, Bob Rockwell, Dexter Gordon, and others such as rock guitarist Link Wray came to live in Copenhagen during the 1960s. Every year in early July, Copenhagen's streets, squares, parks as well as cafés and concert halls fill up with big and small jazz concerts during the Copenhagen Jazz Festival. One of Europe's top jazz festivals, the annual event features around 900 concerts at 100 venues with over 200,000 guests from Denmark and around the world.[215]

The largest venue for popular music in Copenhagen is Vega in the Vesterbro district. It was chosen as "best concert venue in Europe" by international music magazine Live. The venue has three concert halls: the great hall, Store Vega, accommodates audiences of 1,550, the middle hall, Lille Vega, has space for 500 and Ideal Bar Live has a capacity of 250.[216] Every September since 2006, the Festival of Endless Gratitude (FOEG) has taken place in Copenhagen. This festival focuses on indie counterculture, experimental pop music and left field music combined with visual arts exhibitions.[217]

For free entertainment one can stroll along Strøget, especially between Nytorv and Højbro Plads, which in the late afternoon and evening is a bit like an impromptu three-ring circus with musicians, magicians, jugglers and other street performers.[218]

Literature

[edit]

Most of Denmarks's major publishing houses are based in Copenhagen. These include the book publishers Gyldendal and Akademisk Forlag and newspaper publishers Berlingske and Politiken (the latter also publishing books).[219][220] Many of the most important contributors to Danish literature such as Hans Christian Andersen (1805–1875) with his fairy tales, the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855) and playwright Ludvig Holberg (1684–1754) spent much of their lives in Copenhagen. Novels set in Copenhagen include Baby (1973) by Kirsten Thorup, The Copenhagen Connection (1982) by Barbara Mertz, Number the Stars (1989) by Lois Lowry, Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow (1992) and Borderliners (1993) by Peter Høeg, Music and Silence (1999) by Rose Tremain, The Danish Girl (2000) by David Ebershoff, and Sharpe's Prey (2001) by Bernard Cornwell. Michael Frayn's 1998 play Copenhagen about the meeting between the physicists Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg in 1941 is also set in the city. On 15–18 August 1973, an oral literature conference took place in Copenhagen as part of the 9th International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences.[221]

The Royal Library, belonging to the University of Copenhagen, is the largest library in the Nordic countries with an almost complete collection of all printed Danish books since 1482. Founded in 1648, the Royal Library is located at four sites in the city, the main one being on the Slotsholmen waterfront.[222] Copenhagen's public library network has over 20 outlets, the largest being the Central Library (Københavns Hovedbibliotek) on Krystalgade in the inner city.[223]

Art

[edit]

Copenhagen has a wide selection of art museums and galleries displaying both historic works and more modern contributions. They include Statens Museum for Kunst, i.e. the Danish national art gallery, in the Østre Anlæg park, and the adjacent Hirschsprung Collection specialising in the 19th and early 20th century. Kunsthal Charlottenborg in the city centre exhibits national and international contemporary art. Den Frie Udstilling near the Østerport Station exhibits paintings created and selected by contemporary artists themselves rather than by the official authorities. The Arken Museum of Modern Art is located in southwestern Ishøj.[224] Among artists who have painted scenes of Copenhagen are Martinus Rørbye (1803–1848),[225] Christen Købke (1810–1848)[226] and the prolific Paul Gustav Fischer (1860–1934).[227]

A number of notable sculptures can be seen in the city. In addition to The Little Mermaid on the waterfront, there are two historic equestrian statues in the city centre: Jacques Saly's Frederik V on Horseback (1771) in Amalienborg Square[228] and the statue of Christian V on Kongens Nytorv created by Abraham-César Lamoureux in 1688 who was inspired by the statue of Louis XIII in Paris.[229] Rosenborg Castle Gardens contains several sculptures and monuments including August Saabye's Hans Christian Andersen, Aksel Hansen's Echo, and Vilhelm Bissen's Dowager Queen Caroline Amalie.[230]

Copenhagen is believed to have invented the photomarathon photography competition, which has been held in the City each year since 1989.[231][232]

Cuisine

[edit]

As of 2014[update], Copenhagen has 15 Michelin-starred restaurants, the most of any Scandinavian city.[233] The city is increasingly recognized internationally as a gourmet destination.[234] These include Den Røde Cottage, Formel B Restaurant, Grønbech & Churchill, Søllerød Kro, Kadeau, Kiin Kiin (Denmark's first Michelin-starred Asian gourmet restaurant), the French restaurant Kong Hans Kælder, Relæ, Restaurant AOC with two Stars, and Noma (short for Danish: nordisk mad, English: Nordic food) as well as Geranium with three. Noma was ranked as the Best Restaurant in the World by Restaurant in 2010, 2011, 2012, and again in 2014,[235] sparking interest in the New Nordic Cuisine.[236]

Apart from the selection of upmarket restaurants, Copenhagen offers a great variety of Danish, ethnic and experimental restaurants. It is possible to find modest eateries serving open sandwiches, known as smørrebrød – a traditional, Danish lunch dish; however, most restaurants serve international dishes.[237] Danish pastry can be sampled from any of numerous bakeries found in all parts of the city. The Copenhagen Bakers' Association (Danish: Københavns Bagerlaug) dates back to the 1290s and Denmark's oldest confectioner's shop still operating, Conditori La Glace, was founded in 1870 in Skoubogade by Nicolaus Henningsen, a trained master baker from Flensburg.[238]

Copenhagen has long been associated with beer. Carlsberg beer has been brewed at the brewery's premises on the border between the Vesterbro and Valby districts since 1847 and has long been almost synonymous with Danish beer production. However, recent years have seen an explosive growth in the number of microbreweries so that Denmark today has more than 100 breweries, many of which are located in Copenhagen. Some like Nørrebro Bryghus also act as brewpubs where it is also possible to eat on the premises.[239][240]

Nightlife and festivals

[edit]

Copenhagen has one of the highest number of restaurants and bars per capita in the world.[241] The nightclubs and bars stay open until 5 or 6 in the morning, some even longer. Denmark has a very liberal alcohol culture and a strong tradition for beer breweries, although binge drinking is frowned upon and the Danish Police take driving under the influence very seriously.[242] Inner city areas such as Istedgade and Enghave Plads in Vesterbro, Sankt Hans Torv in Nørrebro and certain places in Frederiksberg are especially noted for their nightlife. Notable nightclubs include Bakken Kbh, ARCH (previously ZEN), Jolene, The Jane, Chateau Motel, KB3, At Dolores (previously Sunday Club), Rust, Vega Nightclub and Culture Box.[243][244]

Copenhagen has several recurring community festivals, mainly in the summer. Copenhagen Carnival has taken place every year since 1982 during the Whitsun Holiday in Fælledparken and around the city with the participation of 120 bands, 2,000 dancers and 100,000 spectators.[245] Since 2010, the old B&W Shipyard at Refshaleøen in the harbour has been the location for Copenhell, a heavy metal rock music festival. Copenhagen Pride is a LGBT pride festival taking place every year in August. The Pride has a series of different activities all over Copenhagen, but it is at the City Hall Square that most of the celebration takes place. During the Pride the square is renamed Pride Square.[246] Copenhagen Distortion has emerged to be one of the biggest street festivals in Europe with 100,000 people joining to parties in the beginning of June every year.[247]

Amusement parks

[edit]

Copenhagen has the oldest and third-oldest amusement parks in the world.[248][249]

Dyrehavsbakken, a fair-ground and pleasure-park established in 1583, is located in Klampenborg just north of Copenhagen in a forested area known as Dyrehaven. Created as an amusement park complete with rides, games and restaurants by Christian IV, it is the oldest surviving amusement park in the world.[248] Pierrot (Danish: Pjerrot), a nitwit dressed in white with a scarlet grin wearing a boat-like hat while entertaining children, remains one of the park's key attractions. In Danish, Dyrehavsbakken is often abbreviated as Bakken. There is no entrance fee to pay and Klampenborg Station on the C-line, is situated nearby.[250]

The Tivoli Gardens is an amusement park and pleasure garden located in central Copenhagen between the City Hall Square and the Central Station. It opened in 1843, making it the third-oldest amusement park in the world, the second being Wurstelprater in Vienna. Among its rides are the oldest still operating rollercoaster Rutschebanen from 1915 and the oldest ferris wheel still in use, opened in 1943.[251] Tivoli Gardens also serves as a venue for various performing arts and as an active part of the cultural scene in Copenhagen.[252]

Education

[edit]

Copenhagen has over 94,000 students enrolled in its largest universities and institutions: University of Copenhagen (38,867 students),[253] Copenhagen Business School (20,000 students),[254] Metropolitan University College and University College Capital (10,000 students each),[255] Technical University of Denmark (7,000 students),[256] KEA (c. 4,500 students),[257] IT University of Copenhagen (2,000 students) and the Copenhagen campus of Aalborg University (2,300 students).[258]

The University of Copenhagen is Denmark's oldest university founded in 1479. It attracts some 1,500 international and exchange students every year. The Academic Ranking of World Universities placed it 30th in the world in 2016.[259]

The Technical University of Denmark is located in Lyngby in the northern outskirts of Copenhagen. In 2013, it was ranked as one of the leading technical universities in Northern Europe.[260] The IT University is Denmark's youngest university, a mono-faculty institution focusing on technical, societal and business aspects of information technology.[261]

The Danish Academy of Fine Arts has provided education in the arts for more than 250 years. It includes the historic School of Visual Arts, and has in later years come to include a School of Architecture, a School of Design and a School of Conservation.[262] Copenhagen Business School (CBS) is an EQUIS-accredited business school located in Frederiksberg.[263] There are also branches of both University College Capital and Metropolitan University College inside and outside Copenhagen.[264][265]

Sport